Submitted:

09 February 2024

Posted:

12 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

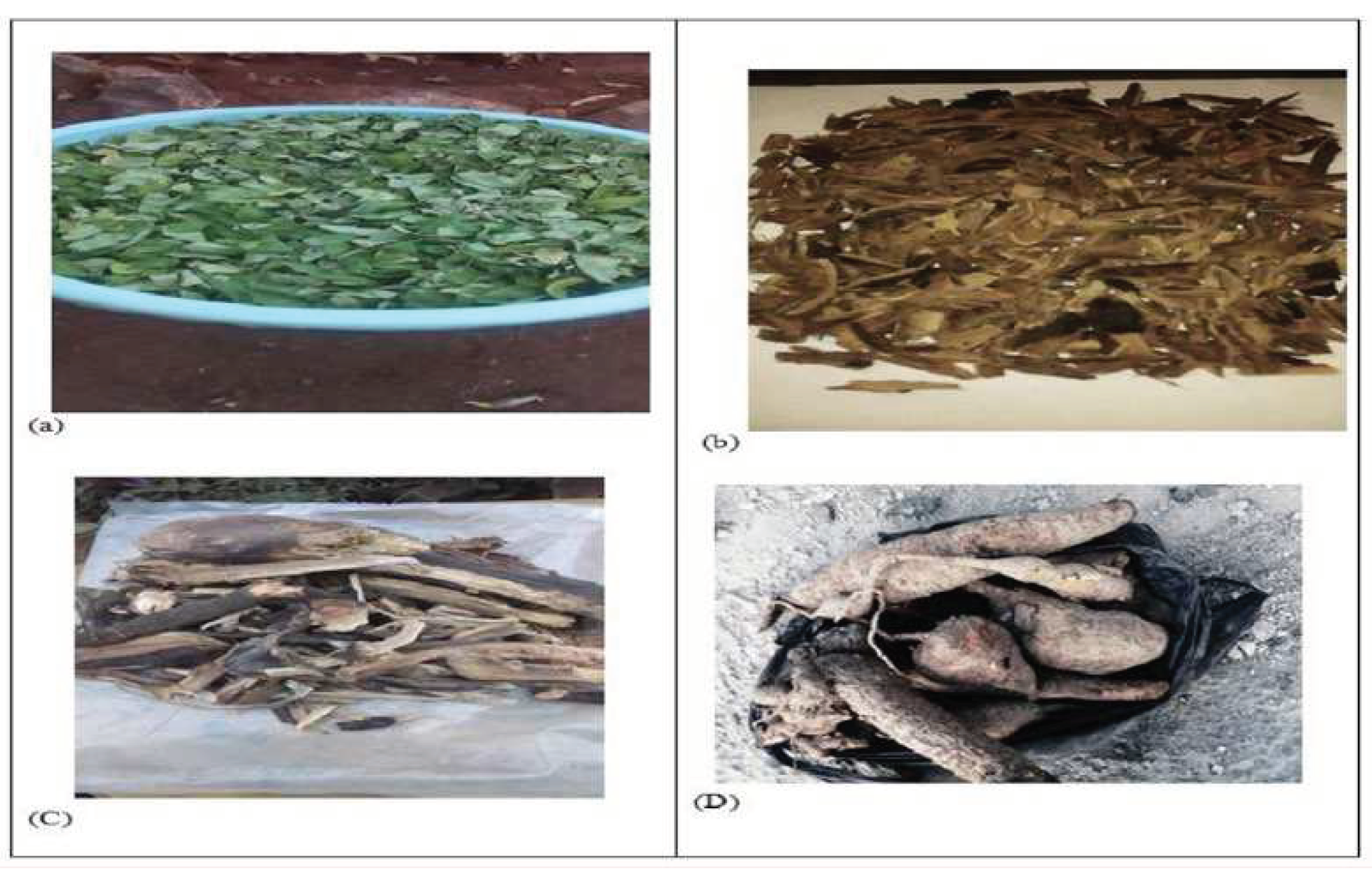

2.1. Plant Material Collection and Authentication

2.2. Preparation of Plant Material

2.3. Preparation of Crude Extracts

2.4. Phytochemical Screening

2.5. Test organisms

2.6. Preparation of extract concentration

2.7. Antibacterial Activity of Plant Extracts

3. Result

3.1. Percentage yields of crude extracts

3.2. Phytochemical Screening of Crude Extracts

3.3. Antibacterial activity of plant extract

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chinemerem Nwobodo, D., et al., Antibiotic resistance: The challenges and some emerging strategies for tackling a global menace. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis, 2022. 36(9). [CrossRef]

- Voukeng, I.K., V.P. Beng, and V. Kuete, Antibacterial activity of six medicinal Cameroonian plants against Gram-positive and Gram-negative multidrug resistant phenotypes. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2016. 16(1): p. 388. [CrossRef]

- Mondal. S. R., N.M.S. Rehana. M. J., and Adhikary. S. K., Comparative study on growth and yield performance of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus florida) on different substrates. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University, 2010. 8(2): p. 213-220. [CrossRef]

- Karaman, R., B. Jubeh, and Z. Breijyeh, Resistance of Gram-Positive Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Overcoming Approaches. Molecules, 2020. 25(12). [CrossRef]

- Manjulika Yadav, S.C., Sharad Kumar Gupta and Geeta Watal, Preliminary Phytochemical Screening of Six Medicinal Plants Used in Traditional Medicine. 2014. 6(5).

- Vaou, N., et al., Towards Advances in Medicinal Plant Antimicrobial Activity: A Review Study on Challenges and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms, 2021. 9(10). [CrossRef]

- WHO, Who Traditional Medicine Strategy 2013.

- Biruhalem Taye, M.G., Abebe Animut, Antibacterial activities of selected medicinal plants in traditional treatment of human wounds in Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed, 2011. 1(5). [CrossRef]

- Biruktayet Assefa, G.G., Christine Buchmann, Ethnomedicinal uses of Hagenia abyssinica (Bruce) J.F. Gmel. among rural communities of Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 2010. 6(20). [CrossRef]

- Svetlana A. Ermolaeva, A.F.V., Marina Yu. Chernukha, Dmitry S. Yurov, Mikhail M. Vasiliev, Anastasya A. Kaminskaya, Mikhail M. Moisenovich, Julia M. Romanova, Arcady N. Murashev, Irina I. Selezneva, Tetsuji Shimizu, Elena V. Sysolyatina, Igor A. Shaginyan, Oleg F. Petrov, Evgeny I. Mayevsky, Vladimir E. Fortov, Gregor E. Morfill, Boris S. Naroditsky and Alexander L. Gintsburg, Bactericidal effects of non-thermal argon plasma in vitro, in biofilms and in the animal model of infected wounds. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Jigna PAREKH, S.V.C., Antibacterial Activity of Aqueous and Alcoholic Extracts of 34 Indian Medicinal Plants against Some Staphylococcus Species. Turk J Biol, 2008.

- Prashant Tiwari, B., M.K. Kumar, Gurpreet, and H.K. Kaur, Phytochemicalscreeningandextraction-Areview. Internationale Pharmaceutica Sciencia, 2011. 1(1).

- Vaishali Rai M , V.R.P., Pratapchandra Kedilaya H, Smitha Hegde, Preliminary Phytochemical Screening of Members of Lamiaceae Family: Leucas linifolia, Coleus aromaticus and Pogestemon patchouli. 2013.

- Taye, B., et al., Antibacterial activities of selected medicinal plants in traditional treatment of human wounds in Ethiopia. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed, 2011. 1(5): p. 370-5. [CrossRef]

- Víctor Lópeza, b., Anna K. Jägerb, Silvia Akerretac, Rita Yolanda Caveroc, Maria Isabel Calvoa, Pharmacological properties of Anagallis arvensis L. (“scarlet pimpernel”) and Anagallis foemina Mill. (“blue pimpernel”) traditionally used as wound healing remedies in Navarra (Sp... Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Mwitari, P.G., et al., Antimicrobial activity and probable mechanisms of action of medicinal plants of Kenya: Withania somnifera, Warbugia ugandensis, Prunus africana and Plectrunthus barbatus. PLoS One, 2013. 8(6): p. e65619. [CrossRef]

- Debes Gerezgher, K.K.C., Zenebe Hagos, K. Devaki, V. K. Gopalakrishnan Phytochemical screening and in vitro antioxidant activities of Senna singueana leaves. Journal of Pharmacy ResearchJournal of Pharmacy Research, 2017. 12(1).

- Gerezgher, D., K.K.C. , and Z.H. , K. Devaki, V. K. Gopalakrishnan, PhytochemicalscreeningandinvitroantioxidantactivitiesofSennasingueanaleaves Journal of Pharmacy Research, 2018. 12(12).

- Olusola Adeyanju, O.O., Afolayan Michael and Khan IZ, Preliminary phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of the leaf extract of Cassia singueana Del. 2011.

- Gebrelibanos, M., In vitro Erythrocyte Haemolysis Inhibition Properties of Senna singueana Extracts. Momona Ethiopian Journal of Science, 2012. 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y., et al., In Vitro Synergistic Inhibitory Effects of Plant Extract Combinations on Bacterial Growth of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2023. 16(10). [CrossRef]

- Ochieng Nyalo, P., G. Isanda Omwenga, and M. Piero Ngugi, GC-MS Analysis, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Potential of Ethyl Acetate Leaf Extract of Senna singueana (Delile) Grown in Kenya. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med, 2022. 2022: p. 5436476. [CrossRef]

- Isaac Thom Shawa, C.M., John Mponda, Cecilia Maliwichi-Nyirenda, Mavuto Gondwe, Antibacterial Effects of Aqueous Extracts of Musa Paradisiaca, Ziziphus Mucronata and Senna Singueana Plants of Malawi. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research, 2016. 6(2): p. 200-2007.

- Dabai, Y.U., Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of the leaf and root extracts of Senna italica. African Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology, 2012. 6(12). [CrossRef]

| Local name | Scientific name | Parts used | Weight of macerated | % yield of crude extract | ||

| Chloroform | Ethanol | Distilled water | ||||

| Hambo hambo | Senna singueana | Leaf | 100 g | 3.84 | 13.06 | 9.42 |

| Stem Bark |

100 g | 9.04 | 15.41 | 6.21 | ||

| Root | 100 g | 0.91 | 6.75 | 4.94 | ||

| Etse- zewie |

Cyphostemma junceum |

Root | 100 g | 1.29 | 1.75 | 7.94 |

| Scientific Name |

Parts used | Solvents | Flavonoids | Tannins | Phenols | Glycoside | Teropenoid | Steroids | Sapnoids | Cumarins |

| S. singueana | leaf | CH | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| ET | + | + | + | - | + | + | - | |||

| DW | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | ||

| Stem bark | CH | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | |

| ET | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | ||

| DW | + | + | + | + | - | - | + | - | ||

| root | CH | - | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | |

| ET | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | ||

| DW | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | - | ||

| C. junceum | root | CH | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - |

| ET | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | + | ||

| DW | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | + |

| Scientific Name |

Parts used | Solvents | Pathogenic bacteria | |||||||

| S. aureus | P. aeruginosa | |||||||||

| 500µg/ml | 250µg/ml | 125µg/ml | Amoxicillin (125µg/ml) | 500µg/ml | 250µg/ml | 125µg/ml | Amoxicillin (125µg/ml) | |||

| S. singueana | leaf | CH | - | 11.5 ± 0.5 | - | 40 ± 0.0 | 14 ±1.0 | 11 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 20 ± 0.0 |

| ET | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 10.5 ±1.5 | 10.5 ± 1.5 | 32.5 ± 2.5 | 11 ±1.0 | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 8 ± 1.0 | 25 ± 0.0 | ||

| DW | - | - | - | 30 ± 0.0 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 7.5 ± 0.5 | 15 ± 0.0 | ||

| Stem bark | CH | 12 ± 0.0 | 11.5 ± 2.5 | - | 31 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 0.0 | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 1.5 | |

| ET | - | - | - | 20.0 ± 0.0 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 0.0 | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 12.5 ± 2.5 | ||

| DW | 11 ± 1.0 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 9 ± 0.0 | 32.5 ± 2.5 | - | - | - | 13 ± 0.0 | ||

| root | CH | 12.5 ± 0.5 | 12 ± 0.00 | - | 37.5 ± 2.5 | - | - | - | 15 ± 0.0 | |

| ET | 11.5 ± 1.5 | 10 ± 1.0 | 8.5 ± 1.5 | 35 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | 12 ± 0.0 | ||

| DW | - | - | - | 32 ± 2.0 | 11.5 ± 0.5 | 10.00 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 10 ± 0.0 | ||

| C. junceum | root | CH | 8.5 ± 0.5 | 10.5 ± 0.5 | 13.5 ± 1.0 | 31 ± 1.0 | - | - | - | 10 ± 0.0 |

| ET | - | - | - | 27 ± 0.0 | 9.5 ± 0.5 | 11 ± 1.0 | 12.5 ± 1.0 | 20 ± 0.0 | ||

| DW | - | - | - | 32.5 ± 2.5 | - | - | - | 11 ± 0.0 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).