Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of Glial Progenitor Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles (EV-GPCs)

2.2. Preparation of Neuroglial Culture

2.3. Induction of Glutamate Excitotoxicity In Vitro

2.4. Assessment of Cell Viability Using the MTT Test and Morphometric Evaluation of Neuronal Death

2.5. Proteomic Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles

2.6. Measurement of [Ca²⁺]i and Mitochondrial Potential (ΔΨm) in Cortical Neurons

2.7. Transcriptomic Analysis (mRNA Sequencing)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proteomic Analysis of EVs

3.1.1. Belonging of Proteins to Intracellular Compartments

3.1.2. Participation of Cargo Proteins in Biological Processes

3.1.3. Molecular Functions of EV-GPCs Cargo Proteins

3.1.4. Activated Signaling Pathways by Protein Cargo of EV-GPCs

3.2. Modeling Glutamate Excitotoxicity and the Neuroprotective Effect of Vesicles

3.3. Measurement of Intracellular Ca²⁺ Concentration ([Ca²⁺]i) and Mitochondrial Transmembrane Potential (ΔΨm)

3.4. The Role of PI3K-Akt Pathway in Neuron Survival

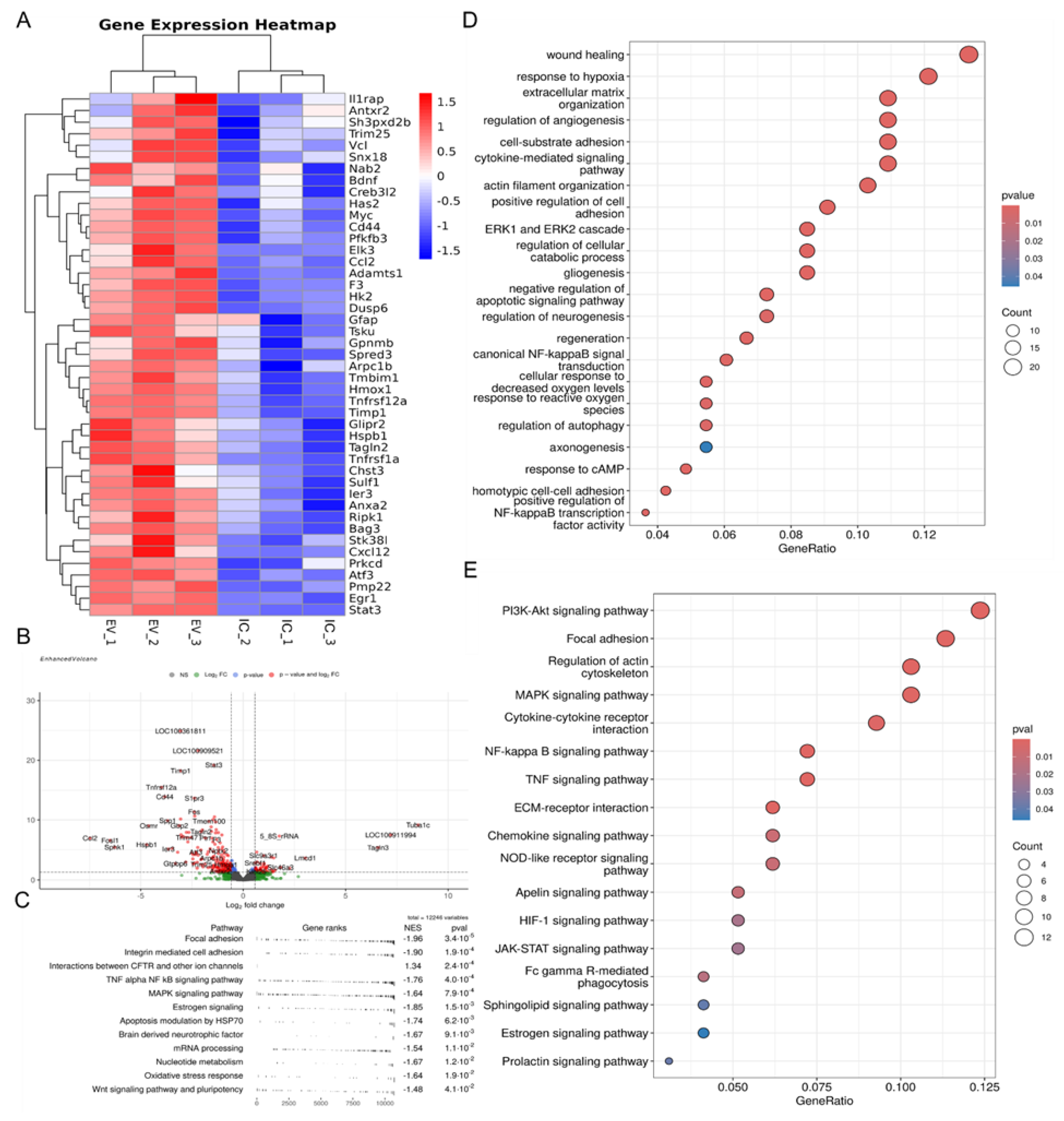

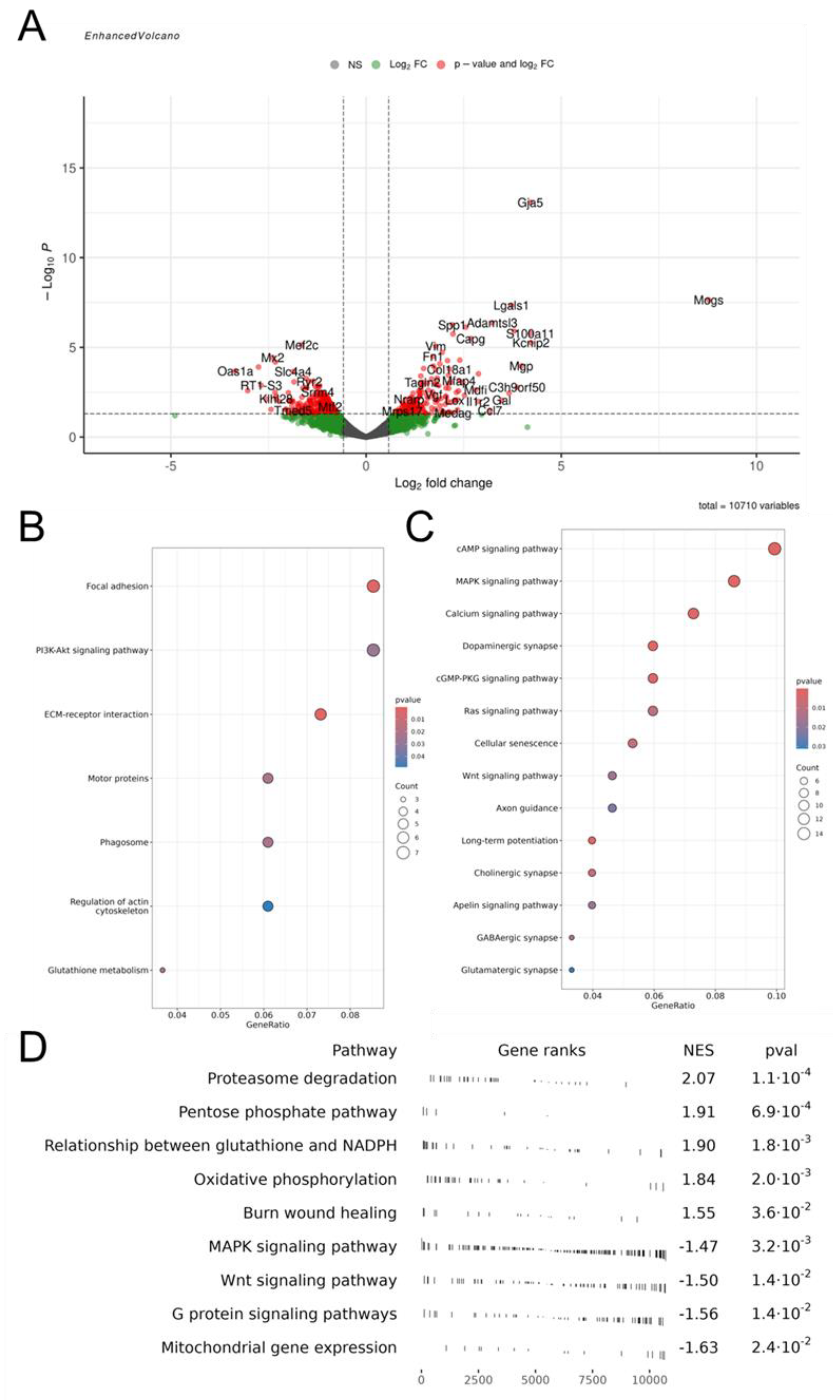

3.5. The Effect of EV-GPCs on the Gene Expression Profile of Neuroglial Cultures. Comparison of Gene Expression in Intact Cells with Neuronal Cultures Pretreated by EV-GPCs (IC_vs_EV)

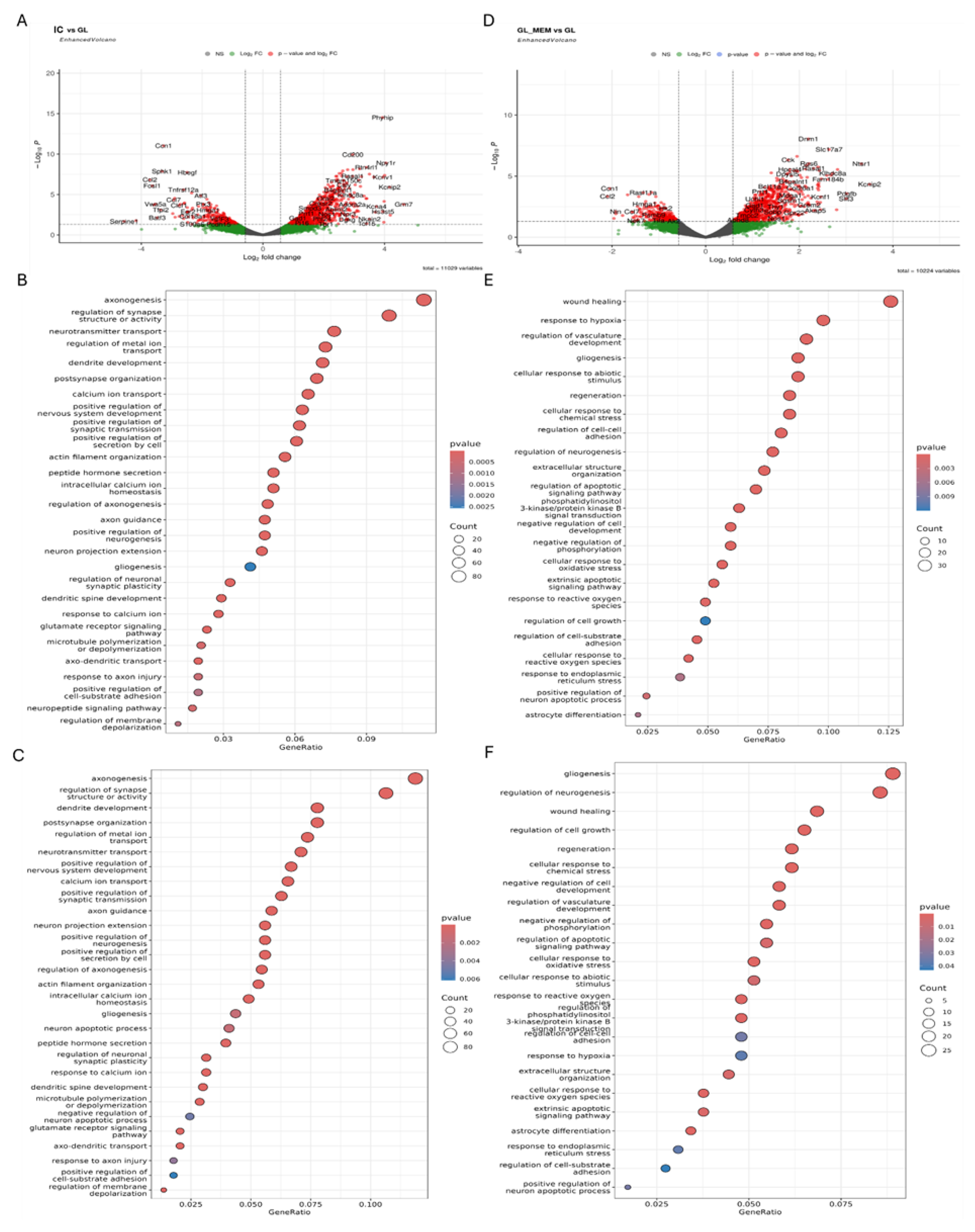

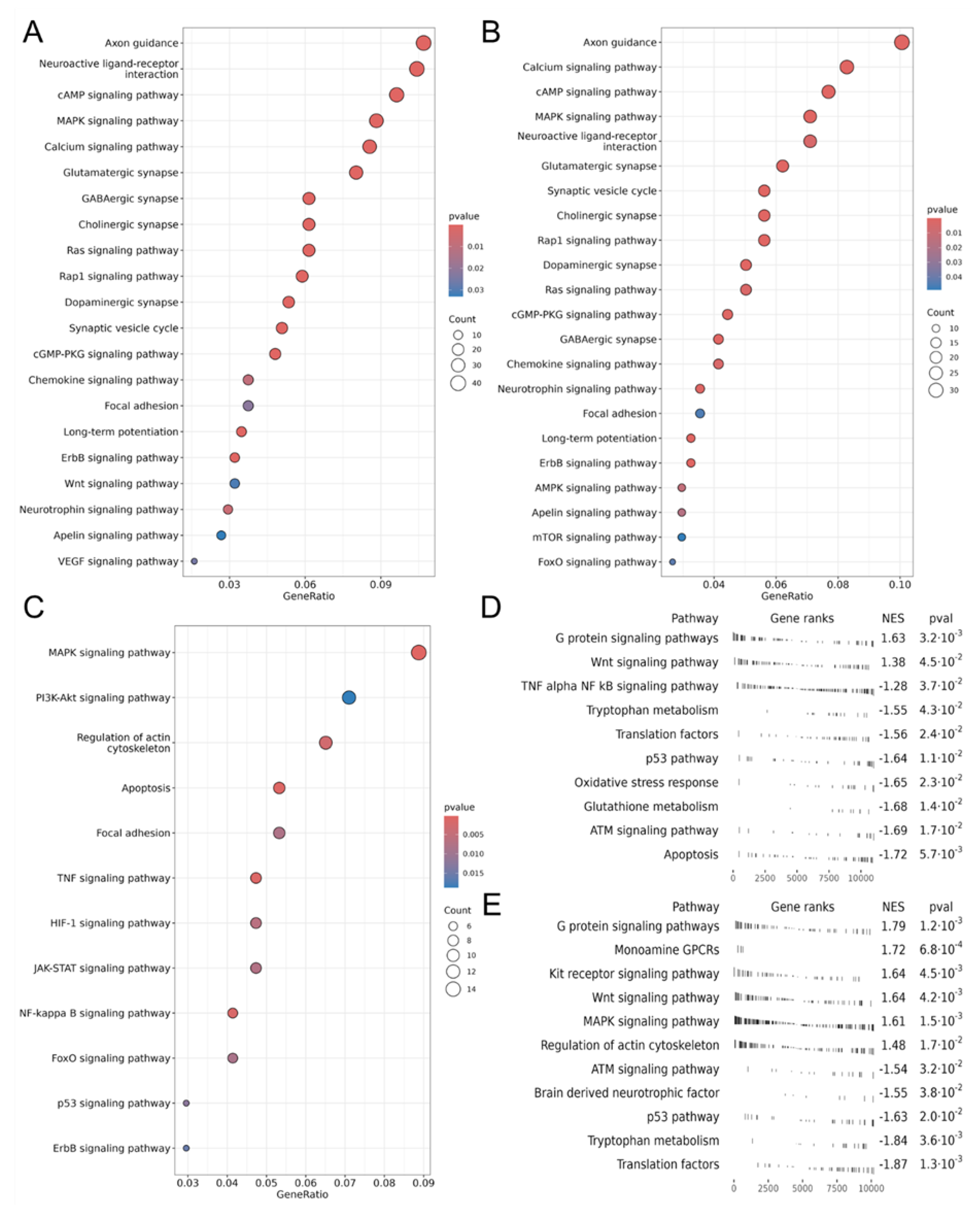

3.6. Assessment of Gene Expression in Neuroglial Cultures Under Glutamate-Induced Excitotoxicity

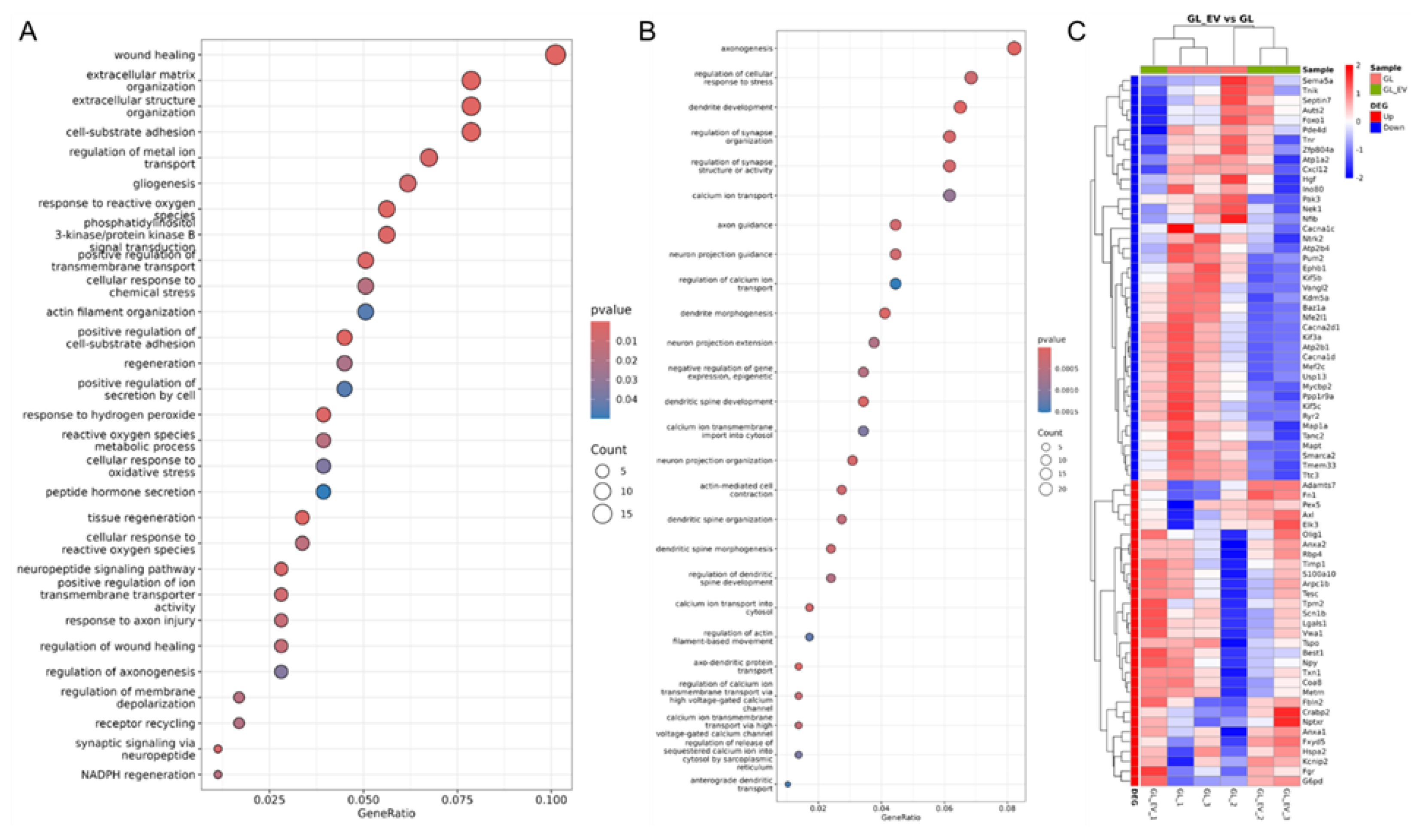

3.7. The Effect of EV-GPCs on the Gene Expression Profile of Neuroglial Cultures Under Glutamate Exitotoxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Maio, V. The glutamatergic synapse: a complex machinery for information processing. Cognitive Neurodynamics 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armada-Moreira, A.; et al. Going the Extra (Synaptic) Mile: Excitotoxicity as the Road Toward Neurodegenerative Diseases. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, U.; et al. Assessing the efficacy of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis drugs in slowing disease progression: A literature review. AIMS Neurosci 2024, 11, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.C.; Wang, Y.T.; Ren, J. Basic information about memantine and its treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other clinical applications. Ibrain 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, M.C. A Review of the Neural Mechanisms of Action and Clinical Efficiency of Riluzole in Treating Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: What have we Learned in the Last Decade? CNS Neuroscience and Therapeutics 2011, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, C.; Karanth, S.; Liu, J. Pharmacology and toxicology of cholinesterase inhibitors: Uses and misuses of a common mechanism of action. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svendsen, S.P.; Svendsen, C.N. Cell therapy for neurological disorders. Nature Medicine 2024, 30, 2756–2770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, Y.; Ågren, L.; Lyczek, A.; Walczak, P.; Bulte, J.W.M. Neural progenitor cell survival in mouse brain can be improved by co-transplantation of helper cells expressing bFGF under doxycycline control. Exp Neurol 2013, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakaji-Hirabayashi, T.; Kato, K.; Iwata, H. In vivo study on the survival of neural stem cells transplanted into the rat brain with a collagen hydrogel that incorporates laminin-derived polypeptides. Bioconjug Chem 2013, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, T.; et al. Teratoma formation leads to failure of treatment for type I diabetes using embryonic stem cell-derived insulin-producing cells. American Journal of Pathology 2005, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, M.; Fong, C.Y.; Chan, W.K.; Wong, P.C.; Bongso, A. Human feeders support prolonged undifferentiated growth of human inner cell masses and embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol 2002, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.B.; et al. Migration and differentiation of nuclear fluorescence-labeled bone marrow stromal cells after transplantation into cerebral infarct and spinal cord injury in mice. Neuropathology 2003, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saboori, M.; Riazi, A.; Taji, M.; Yadegarfar, G. Traumatic brain injury and stem cell treatments: A review of recent 10 years clinical trials. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery 2024, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraniak, P.R.; McDevitt, T.C. Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regenerative Medicine 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, I.S.; Spees, J.L. Stem and progenitor cells for neurological repair: Minor issues, major hurdles, and exciting opportunities for paracrine-based therapeutics. J Cell Biochem 2011, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogatcheva, N.V.; Coleman, M.E. Conditioned Medium of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A New Class of Therapeutics. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2019, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drago, D.; et al. The stem cell secretome and its role in brain repair. Biochimie 2013, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J.C. Extracellular vesicles, from the pathogenesis to the therapy of neurodegenerative diseases. Translational Neurodegeneration 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; et al. Extracellular vesicles as tools and targets in therapy for diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.G.; Wheeler, M.A.; Quintana, F.J. Function and therapeutic value of astrocytes in neurological diseases. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2022, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhova, D.I.; et al. Extracellular vesicles of human glial cells exert neuroprotective effects via brain miRNA modulation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salikhova, D.; et al. Therapeutic effects of hipsc-derived glial and neuronal progenitor cells-conditioned medium in experimental ischemic stroke in rats. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaeva, Z.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide From E. coli Increases Glutamate-Induced Disturbances of Calcium Homeostasis, the Functional State of Mitochondria, and the Death of Cultured Cortical Neurons. Front Mol Neurosci 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S.; others. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. 2010. Https://Www.Bioinformatics.Babraham.Ac.Uk/Projects/Fastqc/ (2019).

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B.; Trimmo1; Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patro, R.; Duggal, G.; Love, M.I.; Irizarry, R.A.; Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat Methods 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soneson, C.; Love, M.I.; Robinson, M.D. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Res 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Research 2000, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Science 2019, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Matsuura, Y.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, D672–D677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjeldal, F.M.; et al. De novo formation of early endosomes during Rab5-to-Rab7a transition. J Cell Sci 2021, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. STK10 knockout inhibits cell migration and promotes cell proliferation via modulating the activity of ERM and p38 MAPK in prostate cancer cells. Exp Ther Med 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.A.; et al. Genetic variation in toll-interacting protein is associated with leprosy susceptibility and cutaneous expression of interleukin 1 receptor antagonist. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2016, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petranka, J.G.; Fleenor, D.E.; Sykes, K.; Kaufman, R.E.; Rosse, W.F. Structure of the CD59-encoding gene: Further evidence of a relationship to murine lymphocyte antigen Ly-6 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, A.K.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of MDA-9/Syntenin blocks breast cancer metastasis through suppression of IL-1β. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukumoto, I.; et al. Abstract 1100: Targeting ITGA3/ITGB1 signaling by tumor-suppressive microRNA-223 inhibits cancer cell migration and invasion in prostate cancer. Cancer Res 2016, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; et al. Macrophage MVP regulates fracture repair by promoting M2 polarization via JAK2-STAT6 pathway. Int Immunopharmacol 2023, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, K.; et al. Annexin A2 promotes phagophore assembly by enhancing Atg16L+ vesicle biogenesis and homotypic fusion. Nat Commun 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKenzie, E.L.; Ray, P.D.; Tsuji, Y. Role and regulation of ferritin H in rotenone-mediated mitochondrial oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med 2008, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D.; et al. Peroxiredoxin 6 maintains mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes tumor progression through ROS/JNK/p38 MAPK signaling pathway in multiple myeloma. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, D.; et al. Discovery of the First-in-Class Inhibitors of Hypoxia Up-Regulated Protein 1 (HYOU1) Suppressing Pathogenic Fibroblast Activation. Angewandte Chemie - International Edition 2024, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masters, S.C.; Yang, H.; Datta, S.R.; Greenberg, M.E.; Fu, H. 14-3-3 inhibits Bad-induced cell death through interaction with serine-136. Mol Pharmacol 2001, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; et al. The CUL4-DDB1 ubiquitin ligase complex controls adult and embryonic stem cell differentiation and homeostasis. Elife 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, T.A.; et al. Endoplasmic reticulum-mediated unfolded protein response and mitochondrial apoptosis in cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Reviews on Cancer 2017, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cao, S.; Li, Y. Mechanistic study of heat shock protein 60-mediated apoptosis in DF-1 cells. Poult Sci 2024, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; et al. DDX1 from Cherry valley duck mediates signaling pathways and anti-NDRV activity. Vet Res 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; et al. MMP14 regulates cell migration and invasion through epithelial-mesenchymal transition in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Am J Transl Res 2015, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, A.; et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF) protects cortical neurons in vitro from oxidant injury by activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 and induction of Bcl-2. Neurosci Res 2012, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; et al. Copine1 regulates neural stem cell functions during brain development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namekata, K.; et al. Neuroprotection and axon regeneration by novel low-molecular-weight compounds through the modification of DOCK3 conformation. Cell Death Discov 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirao, T.; et al. The role of drebrin in neurons. Journal of Neurochemistry 2017, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuramoto, T.; et al. Attractin/mahogany/zitter plays a critical role in myelination of the central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, M.J.; Richie, C.T.; Airavaara, M.; Wang, Y.; Harvey, B.K. Mesencephalic astrocyte-derived neurotrophic factor (MANF) secretion and cell surface binding are modulated by KDEL receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; Sharma, P.; Dahiya, S.; Sharma, B. Plexins: Navigating through the neural regulation and brain pathology. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2025, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trochet, D.; Bitoun, M. A review of Dynamin 2 involvement in cancers highlights a promising therapeutic target. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research 2021, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murga, M.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O.; Tosato, G. Neuropilin-1 regulates attachment in human endothelial cells independently of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2. Blood 2005, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Elsner, T.; Botella, L.M.; Velasco, B.; Langa, C.; Bernabéu, C. Endoglin expression is regulated by transcriptional cooperation between the hypoxia and transforming growth factor-β pathways. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.S.; Liu, Y.L.; Xu, Z.G.; He, C.; Guo, Z.Y. Is myeloid-derived growth factor a ligand of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 2? Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2024, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farach-Carson, M.C.; Warren, C.R.; Harrington, D.A.; Carson, D.D. Border patrol: Insights into the unique role of perlecan/heparan sulfate proteoglycan 2 at cell and tissue borders. Matrix Biology 2014, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.W. Superoxide dismutase 2 gene and cancer risk: Evidence from an updated meta-analysis. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2015, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, J.; Pan, X.; Wei, G.; Hua, Y. Research progress of glutathione peroxidase family (GPX) in redoxidation. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Up-regulation of Cdc37 contributes to schwann cell proliferation and migration after sciatic nerve crush. Neurochem Res 2018, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giulino-Roth, L.; et al. Inhibition of Hsp90 suppresses PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and has antitumor activity in Burkitt lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousoik, E.; Montazeri Aliabadi, H. “Do We Know Jack” About JAK? A Closer Look at JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway. Frontiers in Oncology 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamp, M.E.; Liu, Y.; Kortholt, A. Function and regulation of heterotrimeric g proteins during chemotaxis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuasa-Kawada, J.; Kinoshita-Kawada, M.; Tsuboi, Y.; Wu, J.Y. Neuronal guidance genes in health and diseases. Protein and Cell 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andermatt, I.; et al. Semaphorin 6B acts as a receptor in post-crossing commissural axon guidance. Development (Cambridge) 2014, 141. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, N.J.; Henkemeyer, M. Ephrin reverse signaling in axon guidance and synaptogenesis. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 2012, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, H.; et al. Conserved roles for Slit and Robo proteins in midline commissural axon guidance. Neuron 2004, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salikhova, D.I.; et al. Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties of proteins secreted by glial progenitor cells derived from human iPSCs. Front Cell Neurosci 2024, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgodova, A.; et al. Isoliquiritigenin Protects Neuronal Cells against Glutamate Excitotoxicity. Membranes (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saganich, M.J.; Machado, E.; Rudy, B. Differential expression of genes encoding subthreshold-operating voltage-gated K+ channels in brain. Journal of Neuroscience 2001, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Fan, G.; Shao, S. Role of TNFRSF12A in cell proliferation, apoptosis, and proinflammatory cytokine expression by regulating the MAPK and NF-κB pathways in thyroid cancer cells. Cytokine 2025, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashutosh; Chao, C.; Borgmann, K.; Brew, K.; Ghorpade, A. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 protects human neurons from staurosporine and HIV-1-induced apoptosis: Mechanisms and relevance to HIV-1-associated dementia. Cell Death Dis 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier-Kemper, A.; et al. Annexins A2 and A6 interact with the extreme N terminus of tau and thereby contribute to tau’s axonal localization. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.; Belapurkar, V.; Nair, D.; Ramanan, N. Vinculin-mediated axon growth requires interaction with actin but not talin in mouse neocortical neurons. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2021, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttiglione, M.; Revest, J.M.; Rougon, G.; Faivre-Sarrailh, C. F3 neuronal adhesion molecule controls outgrowth and fasciculation of cerebellar granule cell neurites: A cell-type-specific effect mediated by the Ig-like domains. Mol Cell Neurosci 1996, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Istiaq, A.; Ohta, K. A review on Tsukushi: mammalian development, disorders, and therapy. Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimenez-Cassina, A.; Lim, F.; Cerrato, T.; Palomo, G.M.; Diaz-Nido, J. Mitochondrial hexokinase II promotes neuronal survival and acts downstream of glycogen synthase kinase-3. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitti, M.; et al. Heme oxygenase 1 in the nervous system: Does it favor neuronal cell survival or induce neurodegeneration? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziennis, S.; Alkayed, N.J. Role of Signal Transducer and activator of transcription 3 in neuronal survival and regeneration. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2008, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, T.; et al. Interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein organizes neuronal synaptogenesis as a cell adhesion molecule. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwonek, J.; Wilczyński, G.M. CD44: Molecular interactions, signaling and functions in the nervous system. Front Cell Neurosci 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, E.; et al. The Chemokine CCL2 Promotes Excitatory Synaptic Transmission in Hippocampal Neurons via GluA1 Subunit Trafficking. Neurosci Bull 2024, 40, 1649–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberam, I.; Agalliu, D.; Nagasawa, T.; Ericson, J.; Jessell, T.M. A Cxcl12-Cxcr4 chemokine signaling pathway defines the initial trajectory of mammalian motor axons. Neuron 2005, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminero, A.; Comabella, M.; Montalban, X. Role of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and TNFRSF1A R92Q mutation in the pathogenesis of TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome and multiple sclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2011, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; et al. EGR1 recruits TET1 to shape the brain methylome during development and upon neuronal activity. Nat Commun 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.J.; et al. Anthrax Toxin as a Molecular Platform to Target Nociceptive Neurons and Modulate Pain. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamedi, Y.; Fontanil, T.; Cobo, T.; Cal, S.; Obaya, A.J. New insights into adamts metalloproteases in the central nervous system. Biomolecules 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Parker, B.; Martyn, C.; Natarajan, C.; Guo, J. The PMP22 gene and its related diseases. Molecular neurobiology 2013, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenisch, T.D.; et al. Disruption of hyaluronan synthase-2 abrogates normal cardiac morphogenesis and hyaluronan-mediated transformation of epithelium to mesenchyme. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2000, 106, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joy, M.T.; Vrbova, G.; Dhoot, G.K.; Anderson, P.N. Sulf1 and Sulf2 expression in the nervous system and its role in limiting neurite outgrowth in vitro. Exp Neurol 2015, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, Y.; Jin, H.G.; Ma, H.H.; Zhao, Z.H. Comparative analysis on genome-wide DNA methylation in longissimus dorsi muscle between Small Tailed Han and DorperSmall Tailed Han crossbred sheep. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2017, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, G.; et al. ARPC1B binds WASP to control actin polymerization and curtail tonic signaling in B cells. JCI Insight 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.R.; et al. TAGLN2 polymerizes G-actin in a low ionic state but blocks Arp2/3-nucleated actin branching in physiological conditions. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Cai, S.; Liu, X. SPRED3 regulates the NF-κB signaling pathway in thyroid cancer and promotes the proliferation. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.L.; et al. Dual-specificity protein phosphatase 6 (DUSP6) overexpression reduces amyloid load and improves memory deficits in male 5xFAD mice. Front Aging Neurosci 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; et al. GLIPR-2 Overexpression in HK-2 Cells Promotes Cell EMT and Migration through ERK1/2 Activation. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satoh, J.; Kino, Y.; Yanaizu, M.; Ishida, T.; Saito, Y. Microglia express GPNMB in the brains of Alzheimer’s disease and Nasu-Hakola disease. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seijffers, R.; et al. ATF3 expression improves motor function in the ALS mouse model by promoting motor neuron survival and retaining muscle innervation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. TRIM25 Promotes TNF-α–Induced NF-κB Activation through Potentiating the K63-Linked Ubiquitination of TRAF2. The Journal of Immunology 2020, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; et al. Increased expression of immediate early response gene 3 protein promotes aggressive progression and predicts poor prognosis in human bladder cancer. BMC Urol 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; et al. Mutant HSPB1 overexpression in neurons is sufficient to cause age-related motor neuronopathy in mice. Neurobiol Dis 2012, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Kanthasamy, A.; Anantharam, V.; Rana, A.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Transcriptional regulation of pro-apoptotic protein kinase Cδ: Implications for oxidative stress-induced neuronal cell death. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, H.; et al. Ndr kinases regulate retinal interneuron proliferation and homeostasis. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, S.; et al. Expression of sorting Nexin 18 (SNX18) is dynamically regulated in developing Spinal Motor Neurons. Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry 2011, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corgiat, E.B.; List, S.M.; Rounds, J.C.; Corbett, A.H.; Moberg, K.H. The RNA-binding protein Nab2 regulates the proteome of the developing Drosophila brain. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2021, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, K.K.W. Glial fibrillary acidic protein: From intermediate filament assembly and gliosis to neurobiomarker. Trends in Neurosciences 2015, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; et al. TMBIM1 promotes proliferation and attenuates apoptosis in glioblastoma cells by targeting the p38 MAPK signalling pathway. Transl Oncol 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santoro, A.; et al. BAG3 is involved in neuronal differentiation and migration. Cell Tissue Res 2017, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerosuo, L.; et al. Enhanced expression of MycN/CIP2A drives neural crest toward a neural stem cell-like fate: Implications for priming of neuroblastoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantazopoulos, H.; Woo, T.U.W.; Lim, M.P.; Lange, N.; Berretta, S. Extracellular matrix-glial abnormalities in the amygdala and entorhinal cortex of subjects diagnosed with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampieri, L.; Funes Chabán, M.; Di Giusto, P.; Rozés-Salvador, V.; Alvarez, C. CREB3L2 Modulates Nerve Growth Factor-Induced Cell Differentiation. Front Mol Neurosci 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, K.; Murayama, N.; Ono, K.; Ishizaki, Y.; Tominaga, M. TRPV2 enhances axon outgrowth through its activation by membrane stretch in developing sensory and motor neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franquinho, F.; et al. The dyslexia-susceptibility protein kiaa0319 inhibits axon growth through smad2 signaling. Cerebral Cortex 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jósvay, K.; et al. Besides neuro-imaging, the Thy1-YFP mouse could serve for visualizing experimental tumours, inflammation and wound-healing. Sci Rep 2014, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; et al. NELL2 function in axon development of hippocampal neurons. Mol Cells 2020, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; et al. RTN4/NoGo-receptor binding to BAI adhesion-GPCRs regulates neuronal development. Cell 2021, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherchan, P.; Travis, Z.D.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.H. The potential of Slit2 as a therapeutic target for central nervous system disorders. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, G.; et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O inhibits trigeminal axon growth and branching by repressing TrkB and ret signaling. Ann Intern Med 2013, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Roesener, A.P.; Mendonca, P.R.F.; Mastick, G.S. Robo1 and Robo2 have distinct roles in pioneer longitudinal axon guidance. Dev Biol 2011, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orioli, D.; Klein, R. The Eph receptor family: Axonal guidance by contact repulsion. Trends in Genetics 1997, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, I.; Verderio, C.; Sala, M.; Wilson, M.C.; Matteoli, M. SNAP-25 in neuropsychiatric disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2009, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, S.; et al. Cerebellar shank2 regulates excitatory synapse density, motor coordination, and specific repetitive and anxiety-like behaviors. Journal of Neuroscience 2016, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wit, J.; Ghosh, A. Control of neural circuit formation by leucine-rich repeat proteins. Trends in Neurosciences 2014, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, F.J.; et al. Epigenetic editing of the Dlg4/PSD95 gene improves cognition in aged and Alzheimer’s disease mice. Brain 2017, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niftullayev, S.; Lamarche-Vane, N. Regulators of rho GTPases in the nervous system: Molecular implication in axon guidance and neurological disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Ankyrin repeat-rich membrane spanning protein (Kidins220) is required for neurotrophin and ephrin receptor-dependent dendrite development. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, Y.; et al. Opposing roles in neurite growth control by two seven-pass transmembrane cadherins. Nat Neurosci 2007, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; et al. Transcription factors Bcl11a and Bcl11b are required for the production and differentiation of cortical projection neurons. Cerebral Cortex 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carreño Gutiérrez, H.; et al. Nitric oxide interacts with monoamine oxidase to modulate aggression and anxiety-like behaviour. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2020, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, A.; Serra, M.; Marongiu, J.; Morelli, M. Pharmacological interactions between adenosine A2A receptor antagonists and different neurotransmitter systems. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; et al. Structural insights into thyroid hormone transporter MCT8. Nature Communications 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, J.; Li, F.; Edwards, R.H. The mechanism and regulation of vesicular glutamate transport: Coordination with the synaptic vesicle cycle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Biomembranes 2020, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzagalli, M.D.; Bensimon, A.; Superti-Furga, G. A guide to plasma membrane solute carrier proteins. FEBS Journal 2021, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batten, S.R.; et al. Linking kindling to increased glutamate release in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus through the STXBP5/tomosyn-1 gene. Brain Behav 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um, J.W.; et al. IQ Motif and SEC7 domain-containing protein 3 (IQSEC3) interacts with gephyrin to promote inhibitory synapse formation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2016, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köster, J.D.; et al. Inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-3-kinase-A controls morphology of hippocampal dendritic spines. Cell Signal 2016, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matt, L.; Kim, K.; Chowdhury, D.; Hell, J.W. Role of palmitoylation of postsynaptic proteins in promoting synaptic plasticity. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, M.S.; et al. A syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder caused by rare variants in PPFIA3. Am J Hum Genet 2024, 111, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okerlund, N.D.; et al. Dact1 is a postsynaptic protein required for dendrite, spine, and excitatory synapse development in the mouse forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Psychomotor development and attention problems caused by a splicing variant of CNKSR2. BMC Med Genomics 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, S.E.; Chapman, E.R. Synaptophysin Regulates the Kinetics of Synaptic Vesicle Endocytosis in Central Neurons. Neuron 2011, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; et al. Genetic variation of the RASGRF1 regulatory region affects human hippocampus-dependent memory. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, V.; et al. Identification and functional evaluation of GRIA1 missense and truncation variants in individuals with ID: An emerging neurodevelopmental syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2022, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camp, C.R.; Yuan, H. GRIN2D/GluN2D NMDA receptor: Unique features and its contribution to pediatric developmental and epileptic encephalopathy. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 2020, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigter, P.M.F.; et al. Role of CAMK2D in neurodevelopment and associated conditions. Am J Hum Genet 2024, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S.K.; et al. Bioinformatic Analyses of Canonical Pathways of TSPOAP1 and its Roles in Human Diseases. Front Mol Biosci 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Y.; Song, Y.J.; Zhang, C.L.; Liu, J. KV Channel-Interacting Proteins in the Neurological and Cardiovascular Systems: An Updated Review. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geering, K. FXYD proteins: New regulators of Na-K-ATPase. American Journal of Physiology - Renal Physiology 2006, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, K.; et al. Region- and neuronal-subtype-specific expression of Na,K-ATPase alpha and beta subunit isoforms in the mouse brain. Journal of Comparative Neurology 2020, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strehler, E.E.; Thayer, S.A. Evidence for a role of plasma membrane calcium pumps in neurodegenerative disease: Recent developments. Neuroscience Letters 2018, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, J.K.; Alcaide, J.; Shi, Y. The RELT Family of Proteins: An Increasing Awareness of Their Importance for Cancer, the Immune System, and Development. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, K.; Auer, B.; Mlinac-Jerkovic, K.; Herrera-Molina, R. Neuronal signaling by thy-1 in nanodomains with specific ganglioside composition: Shall we open the door to a new complexity? Front Cell Dev Biol 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.Y.; Wang, K.; Vermehren-Schmaedick, A.; Adelman, J.P.; Cohen, M.S. PARP6 is a Regulator of Hippocampal Dendritic Morphogenesis. Sci Rep 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, J.H.; et al. Important Roles of Ring Finger Protein 112 in Embryonic Vascular Development and Brain Functions. Mol Neurobiol 2017, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; et al. Functional defects in FOXG1 variants predict the severity of brain anomalies in FOXG1 syndrome. Mol Psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funa, K.; Sasahara, M. The roles of PDGF in development and during neurogenesis in the normal and diseased nervous system. Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brawley, C.M.; Uysal, S.; Kossiakoff, A.A.; Rock, R.S. Characterization of engineered actin binding proteins that control filament assembly and structure. PLoS One 2010, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, B.C.; Lanier, M.H.; Cooper, J.A. CARMIL family proteins as multidomain regulators of actin-based motility. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2017, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altas, B.; Romanowski, A.J.; Bunce, G.W.; Poulopoulos, A. Neuronal mTOR Outposts: Implications for Translation, Signaling, and Plasticity. Front Cell Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouinard, F.C.; Davis, L.; Gilbert, C.; Bourgoin, S.G. Functional Role of AGAP2/PIKE-A in Fcγ Receptor-Mediated Phagocytosis. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Hypoxia-induced ROS aggravate tumor progression through HIF-1α-SERPINE1 signaling in glioblastoma. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; et al. The Potential Role of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 in the Progression and Therapy of Central Nervous System Diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol 2021, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foxler, D.E.; et al. A HIF – LIMD 1 negative feedback mechanism mitigates the pro-tumorigenic effects of hypoxia. EMBO Mol Med 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salma, J.; McDermott, J.C. Suppression of a MEF2-KLF6 survival pathway by PKA signaling promotes apoptosis in embryonic hippocampal neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 2012, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryan, L.; Kordula, T.; Spiegel, S.; Milstien, S. Regulation and functions of sphingosine kinases in the brain. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2008, 1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yue, W. VRK2, a Candidate Gene for Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. Complex Psychiatry 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takata, S.; et al. LIF–IGF Axis Contributes to the Proliferation of Neural Progenitor Cells in Developing Rat Cerebrum. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Schaukowitch, K.; Farbiak, L.; Kilaru, G.; Kim, T.K. Stimulus-specific combinatorial functionality of neuronal c-fos enhancers. Nat Neurosci 2015, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Jiang, Y.; Xu, W.; Bao, X. Sestrin2: multifaceted functions, molecular basis, and its implications in liver diseases. Cell Death and Disease 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baur, K.; et al. Growth/differentiation factor 15 controls ependymal and stem cell number in the V-SVZ. Stem Cell Reports 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; et al. The role of heat shock protein 90B1 in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, B.S.; et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 stimulates neuronal differentiation of neuronal stem cells through the ERK pathway. Exp Mol Med 2009, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.Y.; Zukin, R.S. REST, a master transcriptional regulator in neurodegenerative disease. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 2018, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, M.; et al. Peripheral Kv7 channels regulate visceral sensory function in mouse and human colon. Mol Pain 2017, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; et al. Identification of the Fosl1/AMPK/autophagy axis involved in apoptotic and inflammatory effects following spinal cord injury. Int Immunopharmacol 2022, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; et al. TRIB1 confers therapeutic resistance in GBM cells by activating the ERK and Akt pathways. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, E.; Esteras, N. Multitarget Effects of Nrf2 Signalling in the Brain: Common and Specific Functions in Different Cell Types. Antioxidants 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; et al. The antioxidant enzyme Peroxiredoxin-1 controls stroke-associated microglia against acute ischemic stroke. Redox Biol 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biermanns, M.; Gärtner, J. Genomic organization and characterization of human PEX2 encoding a 35-kDa peroxisomal membrane protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winship, A.L.; et al. Interleukin-11 up-regulates endoplasmic reticulum stress induced target, PDIA4 in human first trimester placenta and in vivo in mice. Placenta 2017, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, K.; Oyadomari, S.; Hendershot, L.M.; Ron, D. Regulated association of misfolded endoplasmic reticulum lumenal proteins with P58/DNAJc3. EMBO Journal 2008, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Ferreira, L.P.; et al. Annexin A1 in neurological disorders: Neuroprotection and glial modulation. Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2025, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollárovič, G.; Topping, C.E.; Shaw, E.P.; Chambers, A.L. The human HELLS chromatin remodelling protein promotes end resection to facilitate homologous recombination and contributes to DSB repair within heterochromatin. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; et al. IER3 is a crucial mediator of TAp73β-induced apoptosis in cervical cancer and confers etoposide sensitivity. Sci Rep 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raoul, C.; et al. Motoneuron death triggered by a specific pathway downstream of fas: Potentiation by ALS-linked SOD1 mutations. Neuron 2002, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; et al. Tumor protein translationally controlled 1 is a p53 target gene that promotes cell survival. Cell Cycle 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozinski, B.M.; Ta, K.; Dong, Y. Emerging role of galectin 3 in neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Neural Regeneration Research 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausott, B.; Klimaschewski, L. Sprouty2—a Novel Therapeutic Target in the Nervous System? Molecular Neurobiology 2019, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; et al. The role of KLF4 in Alzheimer’s disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2018, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Q.; et al. Cysteine- and glycine-rich protein 1 predicts prognosis and therapy response in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Exp Med 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, D.; et al. Local and transient inhibition of p21 expression ameliorates age-related delayed wound healing. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2020, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Soury, M.; Gambarotta, G. Soluble neuregulin-1 (NRG1): A factor promoting peripheral nerve regeneration by affecting Schwann cell activity immediately after injury. Neural Regeneration Research 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; et al. Notch1 regulates the functional contribution of RhoC to cervical carcinoma progression. Br J Cancer 2010, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Jian-Xiong, Y. Human tissue factor pathway inhibitor-2 suppresses the wound-healing activities of human Tenon’s capsule fibroblasts in vitro. Mol Vis 2009, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Khan, A.W.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, S. The role of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in tissue repair and regeneration. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takouda, J.; Katada, S.; Imamura, T.; Sanosaka, T.; Nakashima, K. SoxE group transcription factor Sox8 promotes astrocytic differentiation of neural stem/precursor cells downstream of Nfia. Pharmacol Res Perspect 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lo, L.; Dormand, E.; Anderson, D.J. SOX10 maintains multipotency and inhibits neuronal differentiation of neural crest stem cells. Neuron 2003, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, L.E.; et al. Mutations in the early growth response 2 (EGR2) gene are associated with hereditary myelinopathies. Nat Genet 1998, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, L.A.; Lee, H.Y.; Angelastro, J.M. The transcription factor ATF5: Role in neurodevelopment and neural tumors. Journal of Neurochemistry 2009, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, J.; et al. Homeobox gene Nkx2.2 and specification of neuronal identity by graded Sonic hedgehog signalling. Nature 1999, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, M.; et al. Notch1 signaling activation contributes to adult hippocampal neurogenesis following traumatic brain injury. Medical Science Monitor 2017, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobedo, N.; et al. Syndecan 4 interacts genetically with Vangl2 to regulate neural tube closure and planar cell polarity. Development (Cambridge) 2013, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; et al. CXCL12 increases human neural progenitor cell proliferation through Akt-1/FOXO3a signaling pathway. J Neurochem 2009, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, S.; et al. Astrocytic Piezo1-mediated mechanotransduction determines adult neurogenesis and cognitive functions. Neuron 2022, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, R.E.; et al. GADD45 Proteins: Central Players in Tumorigenesis. Curr Mol Med 2012, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; et al. Protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 15 A promotes translation initiation and induces G2M phase arrest during cuproptosis in cancers. Cell Death Dis 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grubbs, E.G.; et al. Role of CDKN2C copy number in sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Thyroid 2016, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, C.D.; Phillips, J.L.; Bronner, M.E. Elk3 is essential for the progression from progenitor to definitive neural crest cell. Dev Biol 2013, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudenok, M.M.; et al. Expression Analysis of Genes Involved in Transport Processes in Mice with MPTP-Induced Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Life 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ould-Yahoui, A.; et al. A new role for TIMP-1 in modulating neurite outgrowth and morphology of cortical neurons. PLoS One 2009, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; et al. Fgr contributes to hemorrhage-induced thalamic pain by activating NF-κB/ ERK1/2 pathways. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.I.; et al. Thioredoxin-1 protein interactions in neuronal survival and neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2025, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadzadeh, P.; Amberg, G.C. AXL/Gas6 signaling mechanisms in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. Frontiers in Endocrinology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyngstadaas, A.V.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Pro-Resolving Actions of the N-Terminal Peptides Ac2-26, Ac2-12, and Ac9-25 of Annexin A1 on Conjunctival Goblet Cell Function. American Journal of Pathology 2023, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.L.; Li, Z.Y.; Song, J.; Liu, J.M.; Miao, C.Y. Metrnl: A secreted protein with new emerging functions. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2016, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Huchzermeyer, S.; et al. The Cellular Retinoic Acid Binding Protein 2 Promotes Survival of Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor Cells. American Journal of Pathology 2017, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeffer, J.; Tannahill, D.; Cioni, J.M.; Rowlands, D.; Keynes, R. Identification of the extracellular matrix protein Fibulin-2 as a regulator of spinal nerve organization. Dev Biol 2018, 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, M.; Fukuda, M. Galectin-1 for Neuroprotection? Immunity 2012, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.X.; Oh, Y.S.; Kim, Y. S100A10 and its binding partners in depression and antidepressant actions. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanicka, J.; et al. The Association of ADAMTS7 Gene Polymorphisms with the Risk of Coronary Artery Disease Occurrence and Cardiovascular Survival in the Polish Population: A Case-Control and a Prospective Cohort Study. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnamenta, A.T.; et al. An ancestral 10-bp repeat expansion in VWA1 causes recessive hereditary motor neuropathy. Brain 2021, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konietzny, A.; Bär, J.; Mikhaylova, M. Dendritic actin cytoskeleton: Structure, functions, and regulations. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.C.; et al. Gene ontology analysis of pairwise genetic associations in two genome-wide studies of sporadic ALS. BioData Min 2012, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notter, T.; et al. Neuronal activity increases translocator protein (TSPO) levels. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silbereis, J.C.; et al. Olig1 Function Is Required to Repress Dlx1/2 and Interneuron Production in Mammalian Brain. Neuron 2014, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez de San José, N.; et al. Neuronal pentraxins as biomarkers of synaptic activity: from physiological functions to pathological changes in neurodegeneration. Journal of Neural Transmission 2022, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzor, N.E.; et al. Aging lowers PEX5 levels in cortical neurons in male and female mouse brains. Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience 2020, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapleau, A.; et al. Neuropathological characterization of the cavitating leukoencephalopathy caused by COA8 cytochrome c oxidase deficiency: a case report. Front Cell Neurosci 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, M.; et al. Lipocalin-2 controls neuronal excitability and anxiety by regulating dendritic spine formation and maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolobynina, K.G.; Solovyova, V.V.; Levay, K.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Slepak, V.Z. Emerging roles of the single EF-hand Ca2+ sensor tescalcin in the regulation of gene expression, cell growth and differentiation. Journal of Cell Science 2016, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, B.; et al. The role of the molecular chaperone heat shock protein A2 (HSPA2) in regulating human sperm-egg recognition. Asian Journal of Andrology 2015, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; et al. GAD65 tunes the functions of Best1 as a GABA receptor and a neurotransmitter conducting channel. Nature Communications 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gotliv, I.L. FXYD5: Na + /K + -ATPase regulator in health and disease. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; et al. Severe ocular phenotypes in Rbp4-deficient mice in the C57BL/6 genetic background. Laboratory Investigation 2016, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmann, F.; Holzer, P. Neuropeptide Y: A stressful review. Neuropeptides 2016, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; et al. SCN1B Genetic Variants: A Review of the Spectrum of Clinical Phenotypes and a Report of Early Myoclonic Encephalopathy. Children 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, W.; et al. Untangle the Multi-Facet Functions of Auts2 as an Entry Point to Understand Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; et al. Loss of TNR causes a nonprogressive neurodevelopmental disorder with spasticity and transient opisthotonus. Genetics in Medicine 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageta-Ishihara, N.; Kinoshita, M. Developmental and postdevelopmental roles of septins in the brain. Neuroscience Research 2021, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cukier, H.N.; et al. An Alzheimer’s disease risk variant in TTC3 modifies the actin cytoskeleton organization and the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway in iPSC-derived forebrain neurons. Neurobiol Aging 2023, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, S.D.S.; et al. Vangl2 acts at the interface between actin and N-cadherin to modulate mammalian neuronal outgrowth. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Rolando, C.; et al. Multipotency of Adult Hippocampal NSCs In Vivo Is Restricted by Drosha/NFIB. Cell Stem Cell 2016, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Gabarre, D.; Carnero-Espejo, A.; Ávila, J.; García-Escudero, V. What’s in a Gene? The Outstanding Diversity of MAPT. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; et al. KIF5C deficiency causes abnormal cortical neuronal migration, dendritic branching, and spine morphology in mice. Pediatr Res 2022, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakabe, I.; Hu, R.; Jin, L.; Clarke, R.; Kasid, U.N. TMEM33: a new stress-inducible endoplasmic reticulum transmembrane protein and modulator of the unfolded protein response signaling. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2015, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.C.; et al. Pum2 Shapes the Transcriptome in Developing Axons through Retention of Target mRNAs in the Cell Body. Neuron 2019, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desole, C.; et al. HGF and MET: From Brain Development to Neurological Disorders. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczyńska, K.; Zhang, Z.; Pietras, T.; Zhang, Y.; Taniguchi, H. NFE2L1/Nrf1 serves as a potential therapeutical target for neurodegenerative diseases. Redox Biology 2024, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higelin, J.; et al. NEK1 loss-of-function mutation induces DNA damage accumulation in ALS patient-derived motoneurons. Stem Cell Res 2018, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santo, E.E.; Paik, J. FOXO in Neural Cells and Diseases of the Nervous System. Current Topics in Developmental Biology 2018, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Klopf, E.; Schmidt, H.A.; Clauder-Münster, S.; Steinmetz, L.M.; Schüller, C. INO80 represses osmostress induced gene expression by resetting promoter proximal nucleosomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2017, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, W.; et al. Deubiquitination of SARM1 by USP13 regulates SARM1 activation and axon degeneration. Life Medicine 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y. Progress on the roles of MEF2C in neuropsychiatric diseases. Molecular Brain 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Bachelin, C.; Nait Oumesmar, B.; Bouslama-Oueghlani, L.; Bouslama-Oueghlani, L. The intellectual disability protein PAK3 regulates oligodendrocyte precursor cell differentiation. Neurobiol Dis 2017, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, C.E.; Méndez, P. Shaping inhibition: Activity dependent structural plasticity of GABAergic synapses. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.K.; Hsin, H.; Huganir, R.L.; Sheng, M. MINK and TNIK differentially act on Rap2-mediated signal transduction to regulate neuronal structure and AMPA receptor function. Journal of Neuroscience 2010, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aabdien, A.; et al. Schizophrenia risk proteins ZNF804A and NT5C2 interact in cortical neurons. European Journal of Neuroscience 2024, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; et al. Disruptive mutations in TANC2 define a neurodevelopmental syndrome associated with psychiatric disorders. Nat Commun 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assali, A.; et al. EphB1 controls long-range cortical axon guidance through a cell non-autonomous role in GABAergic cells. Development (Cambridge) 2024, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.N.; et al. Structure and function of Semaphorin-5A glycosaminoglycan interactions. Nat Commun 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.H.; et al. CXCL12 promotes the crossing of retinal ganglion cell axons at the optic chiasm. Development (Cambridge) 2024, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.; et al. Ubiquitin ligase and signalling hub MYCBP2 is required for efficient EPHB2 tyrosine kinase receptor function. Elife 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koga, M.; et al. Involvement of SMARCA2/BRM in the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet 2009, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, L. El et al. Kdm5a mutations identified in autism spectrum disorder using forward genetics. Elife 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condylis, C.; et al. Dense functional and molecular readout of a circuit hub in sensory cortex. Science (1979) 2022, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollazzo, R.; et al. Structural and functional alterations of neurons derived from sporadic Alzheimer’s disease hiPSCs are associated with downregulation of the LIMK1-cofilin axis. Alzheimer’s Research and Therapy 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgärtel, K.; et al. PDE4D regulates Spine Plasticity and Memory in the Retrosplenial Cortex. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, M.; et al. Neuronal cell-type specific DNA methylation patterns of the Cacna1c gene. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience 2013, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muresan, V.; et al. KIF3C and KIF3A form a novel neuronal heteromeric kinesin that associates with membrane vesicles. Mol Biol Cell 1998, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, Y.; et al. KIF5C, a novel neuronal kinesin enriched in motor neurons. Journal of Neuroscience 2000, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, S.L.; Escayg, A. Extracellular vesicles in the treatment of neurological disorders. Neurobiology of Disease 2021, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginini, L.; Billan, S.; Fridman, E.; Gil, Z. Insight into Extracellular Vesicle-Cell Communication: From Cell Recognition to Intracellular Fate. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bürger, S.; et al. Pigment epithelium-derived factor (Pedf) receptors are involved in survival of retinal neurons. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.L.; Gong, X.X.; Qin, Z.H.; Wang, Y. Molecular mechanisms of excitotoxicity and their relevance to the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases—an update. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, M.; Korkotian, E. Endoplasmic reticulum calcium stores in dendritic spines. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivovarova, N.B.; Andrews, S.B. Calcium-dependent mitochondrial function and dysfunction in neurons: Minireview. FEBS Journal 2010, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spires, T.L.; et al. Activity-dependent regulation of synapse and dendritic spine morphology in developing barrel cortex requires phospholipase C-β1 signalling. Cerebral Cortex 2005, 15, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; et al. Survival of compromised adult sensory neurons involves macrovesicular formation. Cell Death Discov 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, A.R.; et al. Signaling mechanisms underlying reversible activity-dependent dendrite formation. Neuron 2002, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, N.; Giovenzana, M.; Misztak, P.; Mingardi, J.; Musazzi, L. Glutamate-Mediated Excitotoxicity in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Neurodevelopmental and Adult Mental Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, K.; Alexander, K.; Francis, M.M. Reactive Oxygen Species: Angels and Demons in the Life of a Neuron. NeuroSci 2022, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, M.B.; Povysheva, N.V.; Harnett-Scott, K.A.; Aizenman, E.; Johnson, J.W. State-specific inhibition of NMDA receptors by memantine depends on intracellular calcium and provides insights into NMDAR channel blocker tolerability. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bonsergent, E.; et al. Quantitative characterization of extracellular vesicle uptake and content delivery within mammalian cells. Nat Commun 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Read, D.E.; Gorman, A.M. Involvement of Akt in neurite outgrowth. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2009, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alegría, K.; Flores-León, M.; Avila-Muñoz, E.; Rodríguez-Corona, N.; Arias, C. PI3K signaling in neurons: A central node for the control of multiple functions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turovsky, E.A.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles afford neuroprotection by modulating PI3K/AKT pathway and calcium oscillations. Int J Biol Sci 2022, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonafede, R.; et al. Exosome derived from murine adipose-derived stromal cells: Neuroprotective effect on in vitro model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Cell Res 2016, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Human iPSC-derived NSCs Protect Human Neurons Against Aβ-42 Induced Neurodegeneration, Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Tau Phosphorylation. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, W.P.; Yao, W.Q.; Wang, B.; Liu, K. BMSCs-exosomes containing GDF-15 alleviated SH-SY5Y cell injury model of Alzheimer’s disease via AKT/GSK-3β/β-catenin. Brain Res Bull 2021, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; et al. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Enhance PC12 Cell Function through the Activation of the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Stem Cells Int 2021, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, H.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal miR-223 regulates neuronal cell apoptosis. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, A.W.K.; et al. Quercetin: Total-scale literature landscape analysis of a valuable nutraceutical with numerous potential applications in the promotion of human and animal health a review. Anim Sci Pap Rep 2021, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, M.; et al. Preservation of neuronal functions by exosomes derived from different human neural cell types under ischemic conditions. European Journal of Neuroscience 2018, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namini, M.S.; Beheshtizadeh, N.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S.; Ai, J. Human endometrial stem cell-derived small extracellular vesicles enhance neurite outgrowth and peripheral nerve regeneration through activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J Transl Med 2025, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Up/Down-regulated | Name of the gene | Description | GO_Biological processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Elk3 | transcription factor of cell cycle, cell growth and neural tissue development [73] | wound healing |

| Tnfrsf12a | receptor that activates various pathways in neurons [74] | ||

| Timp1 | inhibitor of metalloproteinases responsible for the survival and neuroprotection of neurons [75] | ||

| Anxa2 | gene is critical for axonal growth and cytoskeletal stabilization in neurites [76] | ||

| Vcl | gene controls axon growth through interaction with the extracellular matrix [77] | ||

| F3 | gene controls axon growth through interaction with the extracellular matrix [78] | ||

| Tsku | gene interacts with molecules involved in Wnt signaling and TGF-beta signaling [79] | ||

| Hk2 | gene controls glucose metabolism and energy production [80] | response to hypoxia | |

| Hmox1 | gene that controls redox balance and is involved in various cellular processes, including antioxidant defense and antiapoptosis [81] | ||

| Stat3 | gene stimulates the synthesis of genes responsible for reducing ROS [82] | ||

| Il1rap | interleukin-1 receptor, which in neurons is involved in the development and maintenance of synapses [83] | cytokine-mediated signaling pathway | |

| Cd44 | receptor that binds to hyaluronic acid and is responsible for axonal growth [84] | ||

| Ccl2 | gene is necessary for synapse function and is also involved in neuropeptide transduction [85] | ||

| Cxcl12 | chemokine that controls migration processes, the direction of axon growth, and interactions with other cells [86] | ||

| Tnfrsf1a | TNF receptor, the activation of which leads to the induction of many processes associated with inflammation, neuroprotection and cell homeostasis [87] | ||

| Egr1 | gene responsible for signals in the synaptic cleft and synaptic plasticity [88] | ||

| Antxr2 | gene remodels extracellular matrix [89] | extracellular matrix organization | |

| Adamts1 | gene remodels extracellular matrix [90] | ||

| Pmp22 | gene helps maintain the myelin sheath around the processes [91] | ||

| Has2 | hyaluronic acid synthetase [92] | ||

| Sulf1 | gene modifies heparan sulfate, thereby being able to modify various signaling pathways [93] | ||

| Sh3pxd2b | gene controls the actin cytoskeleton and cell adhesion [94] | cell-substrate adhesion | |

| Arpc1b | gene that controls actin polymerization and cell migration [95] | actin filament organization | |

| Tagln2 | control the growth of dendritic spines and the elongation of axons [96] | ||

| Spred3 | Ras/MAPK cascade inhibitors [97] | ERK1 and ERK2 cascade | |

| Dusp6 | Ras/MAPK cascade inhibitors [98] | ||

| Glipr2 | activators of the pathway that stimulates the development and survival of neurons [99] | ||

| Gpnmb | activators of the pathway that stimulates the development and survival of neurons [100] | ||

| Atf3 | gene activated by the ERK1 and ERK2 cascade and stimulating cell proliferation [101] | ||

| Trim25 | activator of NF-kappa B signaling pathway [102] | canonical NF-kappaB signal transduction | |

| Ier3 | activator of NF-kappa B signaling pathway [103] | ||

| Hspb1 | gene protectes against reactive oxygen species and the elimination of proteins damaged by it [104] | response to reactive oxygen species | |

| Prkcd | kinase that controls the balance between cell death and survival [105] | ||

| Stk38l | gene controles microtubule reorganization and neurite growth [106] | regulation of cellular catabolic process | |

| Snx18 | gene regulates the development of the axonal cone [107] | regulation of neurogenesis | |

| Nab2 | gene controls axon growth and dendrite branching [108] | ||

| Gfap | gene controles maintaining the structure and function of astrocytes [109] | gliogenesis | |

| Tmbim1 | transmembrane subunit of the BAX inhibitor - regulates the level of intracellular calcium, and also blocks the action of the proapoptotic protein Bax [110] | ||

| Bag3 | gene controls the formation of autophagosomes and stabilizes the functioning of mitochondria [111] | negative regulation of apoptotic signaling pathway | |

| Bdnf | gene plays a vital role in supporting the growth and survival of neurons in the brain | regulation of autophagy | |

| Mycn | gene acts as a transcription factor, influencing gene expression related to cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation [112] | regeneration | |

| Chst3 | the chondroitin 6-O-sulfotransferase 1 gene, which is responsible for modifications of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans needed for the regeneration of neuronal processes [113] | ||

| Creb3l2 | transcription factor involved in neuroregeneration, particularly by promoting neurite outgrowth and neuronal differentiation [114] |

| Up/Down-regulated | Name of the gene | Description | GO_Biological processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Trpv2, Nell2, Thy1, Kiaa0319 | gene’s proteins are found in the axonal cone and provide guidance for axon growth [115,116,117,118] | axonogenesis |

| Rtn4rl1 | gene is an active participant in axon regeneration [119] | ||

| Slit2 | gene is responsible for axon navigation, inhibiting its growth in the wrong direction [120] | ||

| Ptpro | gene controls axon elongation and branching in response to BDNF [121] | ||

| Robo2 | Robo-signaling protein responsible for axon elongation [122] | ||

| Epb41l3, Epha4, Ephb6, Ephx4 | the ephrin family genes are responsible for axon elongation [123] | ||

| Snap25 | synaptovesicle protein [124] | regulation of synapse structure or activity | |

| Shank2, Shank1 | synaptic scaffold proteins, to control receptor positioning [125] | ||

| Lrfn1, Dlg4, Arhgap33 | genes control synaptic plasticity and structure control [126,127,128] | ||

| Kidins220, Celsr2, Bcl11a | dendrite formation genes [129,130,131] | dendrite development | |

| Nos1 | nitric oxide (NO) synthetase, which acts as a signaling messenger in various neural processes [132] | neurotransmitter transport | |

| Adora2a | receptor that influence the release of various neurotransmitters, including glutamate, dopamine and GABA [133] | ||

| Slc16a2 | thyroid hormone transporter [134] | ||

| Slc17a6, Slc17a7 | glutamate transporters [135] | ||

| Slc2a3, Slc2a6 | glucose transporters [136] | ||

| Stxbp5 | neurotransmitter exocytosis regulator [137] | ||

| Iqsec3 | gene participates in the regulation of the postsynaptic membrane in GABAergic synapses [138] | postsynapse organization | |

| Itpka | one of the subunits of postsynaptic kinases that respond to activation of receptors on the postsynaptic membrane [139] | ||

| Grip2 | the major protein of scaffolds on the postsynaptic membrane that controls the location of AMPA-kainate receptors [140] | ||

| Ppfia2, Ppfia3, Ppfia4, Rims1, Unc13a | proteins form presynaptic terminals by regulating the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the membrane [141] | positive regulation of synaptic transmission | |

| LRRTM1, Cnksr2, Dact1 | genes responsible for synapse structuring and formation [142,143] | ||

| Syp | gene modulates the function of the synapse, which controls vesicle fusion and neurotransmitter exocytosis [144] | ||

| Rasgrf1 | a protein in the Ras signaling pathway that is responsible for the response to calcium influx at the postsynaptic membrane [145] | ||

| Gria4, Gria1 | glutamate receptor subunits [146] | glutamate receptor signaling pathway | |

| Grin1, Grin2d | NMDA receptor subunit genes that respond to glutamate [147] | ||

| Camk1g, Camk2a, Camk2b, Camk2d, Camkk1 | Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase genes, which are responsible for the membrane depolarization response [148] | regulation of membrane depolarization | |

| Tspoap1 | gene influences the localization of voltage-gated channels [149] | regulation of metal ion transport | |

| Kcnip1, Kcnip2, Kcnip4 | Potassium ion voltage-gated channel proteins [150] | ||

| Fxyd6, Fxyd7 | proteins that control the work of Na+/K+-ATPase [151] | ||

| Atp1a3, Atp1b1 | Na+/K+-ATPase subunit proteins [152] | ||

| Atp2b2, Atp2b3, Atp2b4 | Plasma membrane Ca2+ transporting ATPase (PMCA2) plays a critical role in neurons by regulating calcium ion concentrations [153] | calcium ion transport | |

| Rell2 | gene for a transmembrane protein that activates Rell signaling [154] | positive regulation of cell-substrate adhesion | |

| Thy1 | CD90 protein is a membrane protein that controls axonal growth by anchoring it to the extracellular matrix [155] | ||

| Foxg1, Rnf112, Parp6 | genes involved in neuronal development [156,157,158] | positive regulation of nervous system development | |

| Pdgfb | astrocyte proliferation stimulating protein [159] | gliogenesis | |

| Bmerb1, Carmil2, Carmil3 | proteins that regulate actin polymerization and signaling pathways in neurons [160,161] | actin filament organization | |

| mTOR | autophagy regulating protein [162] | negative regulation of neuron apoptotic process | |

| Agap2 | gene stimulates neuronal survival processes by activating the PI3K/Akt pathway [163] | ||

| Down-regulated | Hmox1, Serpine1 | hypoxia response protein [164] | response to hypoxia |

| Pmaip1 | proapoptotic protein, inhibitory anti-apoptotic protein Mlc-1 [165] | ||

| Limd1 | Hif-1alpha inhibitory gene [166] | ||

| Lif, Vrk2, Sphk1, Klf6 | activators of cell survival pathways [167,168,169,170] | cellular response to chemical stress | |

| Fos, Sesn2, Gdf15 | a marker of cellular response to stress [171,172,173] | ||

| Hsp90b1 | heat shock protein that responds to the accumulation of misfolded proteins [174] | ||

| Rest, Bmp4 | protein activated by oxidative stress [175,176] | ||

| Bdkrb2 | bradykinin receptor that triggers neuroinflammation processes [177] | ||

| Trib1, Fosl1 | genes that are activated by different types of stress, such as DNA damage from reactive oxygen species [178,179] | cellular response to oxidative stress | |

| Nfe2l2, Prdx1, Pex2 | genes for proteins that neutralizes reactive oxygen species, thereby protecting cells [180,181,182] | ||

| Dnajc3, Pdia4 | genes are activated by ER stress [183,184] | response to endoplasmic reticulum stress | |

| Anxa1, Hells | their expression is increased during apoptosis [185,186] | regulation of apoptotic signaling pathway | |

| Ier3, Fas, Tnfrsf12a | genes that are activated by any type of stress, stimulating apoptosis [187,188] | ||

| Tpt1 | a gene that controls both cell survival and cell death pathways [189] | ||

| Lgals3 | galectin-3 protein, which is activated by glutamate excitotoxicity and triggers autophagy and apoptosis processes [190] | ||

| Spry2 | gene reacts to a decrease in oxygen by activating cell death processes [191] | ||

| Klf4 | a gene for a protein that enhances the response to oxidative stress, thereby stimulating apoptosis [192] | ||

| Cdkn1a, Csrp1 | a gene that is activated in response to cell damage and stimulates its repair [193,194] | wound healing | |

| Nrg1 | gene actively participates in the development of neurons and in the restoration of synapse function [195] | ||

| Tfpi2, Rhoc | genes activated by axonal injury [196,197] | ||

| Fgf2 | cell division stimulating growth factor [198] | ||

| Egr2, Etv5, Nin, Sox10, Sox8 | proteins that control neurite elongation [199,200,201,202] | regulation of neurogenesis | |

| Nkx2-2, Notch1 | proteins stimulate regeneration [203,204] | ||

| Sdc4, Cxcl12 | genes responsible for intercellular adhesion and migration [205,206] | regulation of cell-cell adhesion | |

| Has2 | gene controls synthesis of hyaluronic threads [92] | extracellular structure organization | |

| Piezo1 | mechanotransduction gene activated by neuronal adhesion [207] | ||

| Gadd45b, Gadd45g, Gadd45a | genes for subunits of phosphatase that inhibits the MAPK kinase cascade [208] | negative regulation of phosphorylation | |

| Ppp1r15a | a gene that is activated in response to various types of cellular stress, including oxidative stress [209] | ||

| Cdkn2c, Cdkn2b | inhibitors of CDK4 and CDK6, thereby inhibiting the cell cycle [210] |

| Up/Down-regulated | Name of the gene | Description | GO_Biological processes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | Elk3, Timp1, Anxa2 | genes stimulate wound healing by enhancing proliferation, elongating processes and inhibiting apoptosis [211,212,213] | wound healing |

| Fgr | tyrosine kinase that activates NF-κB and ERK1/2 pathways [214] | phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B signal transduction | |

| Txn1 | thioredoxin, which acts as an antioxidant, thereby protecting against oxidative stress [215] | ||

| Axl | Gas6 receptor, activation of which also promotes survival [216] | ||

| Metrn | gene responsible for the elongation of axons [218] | regulation of axonogenesis | |

| Crabp2 | gene participates in axon regeneration [219] | regulation of axonogenesis cell-substrate adhesion |

|

| Fbln2 | a gene encoding an extracellular matrix protein that is involved in the outgrowth of the dendritic tree [220] | ||

| Lgals1 | galectin, which is actively expressed in neurons and is responsible for the interaction between cells of the nervous tissue [221] | cell-substrate adhesion extracellular matrix organisation |

|

| S100a10 | it is involved in the regulation of serotonin receptor traffic, glutamatergic transmission and calcium signaling in neurons [222] | ||

| Fn1 | fibronectin, a key component of the brain’s extracellular matrix | ||

| Adamts7 | a metalloproteinase that can degrade components of the extracellular matrix [223] | extracellular matrix organisation actin filament organisation |

|

| Vwa1 | gene is actively expressed at the ends of neurites and interacts with the extracellular matrix [224] | ||

| Arpc1b | a protein responsible for the branching of the actin cytoskeleton and thus for the branching of neurites [225] | ||

| Tpm2 | gene controls the formation of axons and dendrites, the elongation of nerve cell processes [226] | actin filament organisation gliogenesis |

|

| Tspo | gene responsible for astrocyte proliferation [227] | ||

| Olig1 | gene activates oligodendrocytes and stimulates the protection of neuronal processes [228] | gliogenesis response to reactive oxygen species |

|

| Nptxr | pentraxin, which controls synapse formation and the flow of ions into neurons [229] | ||

| Pex5 | gene involved in the formation of peroxisomes [230] | response to reactive oxygen species cellular response to oxidative stress |

|

| G6pd | gene involved in cellular respiration and synthesis | ||

| Coa8 | electron transport chain gene cytochrome c oxidase-binding [231] | cellular response to oxidative stress reactive oxygen species metabolic process |

|

| Lcn2 | gene participates in the control of neuronal responses to external stimuli [232] | ||

| Spp1 | gene is associated with cell survival and axon reorganization upon injury [216] | response to axon injury | |

| Tesc | gene controls the entry of metal ions into neurons, especially calcium ions, by binding to it [233,234] | regulation of metal ion transport | |

| Hspa2 | heat shock protein gene, which is involved in ion transport by binding to the CatSper ion channel [234] | regulation of metal ion transport peptide hormone secretion |

|

| Kcnip2 | Potassium ion voltage-gated channel [150] | ||

| Best1 | calcium-activated anion channel, meaning it allows chloride ions to pass through cell membranes in response to changes in intracellular calcium levels [235] | ||

| Fxyd5 | gene regulates the work of Na+/K+-ATPase [236] | ||

| Rbp4 | gene participates in the transport of retinoic acid [237] | ||

| Npy | a neuropeptide essential for the survival of neurons [238] | peptide hormone secretion regulation of membrane depolarisation |

|

| Scn1b | voltage-gated sodium channel beta-1 subunit (VGSC) [239] | ||

| Auts2, Tnr, Septin7 | genes regulate of axon and neurite growth [240,241,242] | axonogenesis | |

| Down-regulated | Ttc3, Vangl2, Nfib | genes inhibit the emergence of neurites and the elongation of axons [243,244,245] | axonogenesis regulation of cellular response to stress |

| Kif5c, Kif5b, Mapt | genes responsible for transport in axons and dendrites [246,247] | ||

| Tmem33 | an ER stress-induced molecule that modulates the unfolded protein response signaling cascade leading to apoptosis [248] | ||

| Pum2 | gene responsible for axon regeneration in response to stress [249] | regulation of cellular response to stress dendrite development |

|

| Hgf | gene stimulates neuronal survival in response to injury [250] | ||

| Nfe2l1 | gene activated by ER stress [251] | ||

| Nek1 | gene plays a key role in the response to DNA damage [252] | ||

| Foxo1 | one of the key genes in the response to oxidative stress [253] | ||

| Ino80 | gene responsible for the repair of double-strand DNA breaks [254] | ||

| USP13 | gene plays a role in various cellular processes in neurons, including regulation of protein degradation and axonal degeneration [255] | ||

| Mef2c | a gene encoding a protein that regulates the formation of dendritic spines, which stimulates the elimination of spines during excitotoxicity [256] | ||

| Pak3 | gene participates in the formation of dendritic spines [257] | dendrite development regulation of synapse organization |

|

| Ppp1r9a | gene responsible for the creation of protein scaffolds in the synapse [258] | ||

| Tnik, Zfp804a, Tanc2 | genes responsible for regulating the structure and function of synapses [259,260,261] | regulation of synapse organization axon guidance |

|

| Ntrk2, Ephb1, Sema5a, Cxcl12 | genes are necessary for the correct direction of axon growth [262,263,264] | ||

| Mycbp2 [265] | gene is involved in axon degradation | axon guidance regulation of calcium ion transport |

|

| Atp2b4, Atp2b1, Atp1a2, Ryr2, Camk4 | genes of ion transporters that control the transport of calcium ions into the cytoplasm of neurons | ||

| Baz1a, Kdm5a, Smarca2 | genes that control DNA remodeling [266,267,268] | negative regulation of gene expression, epigenetic | |

| Limch1, Pde4d | gene play a role in regulating cell motility [269,270] | actin-mediated cell contraction | |