1. Introduction

The structure of contemporary security threats is undergoing a qualitative transformation that remains inadequately addressed by traditional military doctrines, counter-terrorism frameworks, or financial regulatory systems. The classical security paradigm defines ‘war’ as a recognisable set of high-intensity actions: troop deployments, firepower projection, contests for air/sea supremacy, suppression of critical nodes, subsequently supplemented by propaganda and information warfare. This paradigm rests upon two implicit assumptions: firstly, that armed forces constitute the primary vehicle for deterrence and conflict; secondly, that the costs and benefits of warfare are settled within the physical domain – namely, territory, resources, casualties, and destruction of infrastructure. The phenomena analysed herein demonstrate that both these premises are simultaneously failing.

An increasingly evident reality is that a sophisticated adversary need no longer prioritise the destruction of an opponent’s military capabilities, nor even breach their borders, to exert dominance. Instead, it may operate a tiered attack architecture without formal declaration of war: deploying highly dispersed, low-signature, deniable small-unit infiltration cells within the target nation’s territory to trigger simultaneous multi-point infrastructure disruptions through ‘accidental’ sabotage; Simultaneously, it pre-constructs directional financial positions tied to these events within global capital markets (such as put options, sovereign credit default swaps, and hedged bond spread strategies). This enables it to force capital markets to substitute credit punishment for artillery punishment, and soaring financing costs for traditional military blockades, after manufacturing a narrative of “systemic failure”. This signifies that the primary lethality of conflict no longer stems from tanks rolling across borders, but from credit curves being instantly rewritten; the outcome of strategic strikes manifests not as “bridges blown up,” but as “the nation being repriced by capital markets as a high-risk sovereign entity, compelled to adopt wartime fiscal postures.” In other words, sovereign credit itself is weaponised, becoming a strategic strike surface that can be deployed while maintaining the legal pretence of ‘peace’.

This mode of attack is not merely an extension of individual tactics or techniques, but rather a systematic, closed-loop approach. It merges two traditionally isolated security dimensions—physical sabotage and financial speculation—into a mutually reinforcing feedback system: the former provides visible ‘evidence’, while the latter amplifies this ‘evidence’ within capital structures into systemic risk pricing. This structural linkage may be understood as an evolved iteration of “grey zone hybrid warfare”. The grey zone denotes the deliberately ambiguous attribution space between peace and full-scale conflict; hybridity signifies not merely the parallel deployment of conventional forces and information warfare, but the coordinated operation of “deniable, decentralised disruption networks coupled with large-scale credit repricing in capital markets”. Its strategic objective is not to defeat the adversary’s forces, but to breach their fiscal resilience, industrial resilience, and political legitimacy. This renders the adversary financially overextended, plagued by capital flight, gripped by social panic, and suffering from uncontrollable internal accountability – all before it can secure legal recognition of having ‘suffered an armed attack’.

The existing security discourse remains fragmented in addressing this phenomenon. The counter-terrorism framework defines “explosions, arson, and infrastructure sabotage” as threats to public safety or criminal offences, assuming these acts primarily aim to instil panic and coerce policy concessions. The financial regulatory framework views “abnormal position-building, expectation manipulation, and short-selling arbitrage” as market misconduct or compliance review issues. Meanwhile, the national security and collective defence framework focuses on “whether an attributable armed attack exists” to determine if a collective response should be triggered. In essence, these three systems monitor distinct chains of events, yet none institutionally acknowledges that these chains have, in practical operation, coalesced into a profit-driven, replicable, and scalable attack model. The aggressor does not merely seek to “frighten civilians,” nor is it solely about “making a quick profit,” nor is it about “staging a brief demonstrative conflict.” Their objective is far more fundamental: to subject the target state to wartime-level pressure simultaneously across four pillars – fiscal, financial, social narrative, and political legitimacy – while preventing it from legally defining this as “war”. This denial of war status prevents the invocation of alliance obligations, the activation of wartime powers, and even the domestic political justification for extraordinary measures.

To characterise this pattern, this paper proposes an analytical framework: the dual-layer coordination model. Its upper layer constitutes a “physically dispersed disruption network”, referring to the deployment of minimal-scale, modular disruption units across the target nation’s territory. These units execute synchronised, low-intensity yet highly visible “accident-style” disruptions targeting high-signal nodes such as energy, transport, logistics, communications, and consumer brands. Such disruption deliberately pursues two characteristics: firstly, multi-point concurrency, creating a spatial and temporal perception among the public and media that “problems are occurring everywhere”; secondly, extremely high deniability, where evidence points more towards “regulatory failure,” “industrial negligence,” or “inadequate maintenance” rather than “organised strikes by external hostile actors.” Beneath this lies the “financial exploitation layer”, referring to financial positions established by attackers prior to physical operations: deep put options, sovereign credit default swaps, spread trades between sovereign debt and counterparty government bonds, and even pre-configured channels for public opinion and information dissemination. This layer does not passively await news developments but consciously shapes narratives. It reframes what might otherwise be viewed as isolated incidents of physical damage as evidence of systemic governance failure. This manipulation guides capital markets to elevate localised incidents into systemic risk assumptions, thereby driving sovereign credit repricing, financing cost escalation, and the evaporation of key enterprises’ market capitalisation.

Crucially, these two layers are not loosely assembled but form a self-sustaining economic-security feedback loop: pre-establishing positions → creating multiple points of disruption → amplifying the narrative of “state failure” → capital markets punishing the target nation through credit sanctions → arbitrage realisation → profit repatriation to fund the next cycle of operations. We term this the “destruction-pricing cycle”. Once this cycle becomes financially self-sustaining (where the financial gains from attacks sufficiently cover or even exceed the operation’s costs), such offensives transcend single-event political motivations. They become industrialised and normalised, evolving into an on-demand geopolitical instrument. At this juncture, we confront not an amplified version of “terrorism” or “espionage”, but something closer to a “credit erosion war”: forcing a nation’s apparatus to collapse prematurely at the fiscal and governance levels by persistently altering its credit rating, rather than occupying its territory.

This gives rise to four core research questions, which form the analytical framework of this paper. Firstly, how can discrete disruptive networks systematically erode a target nation’s critical infrastructure and societal confidence without triggering conventional collective defence thresholds (i.e., without constituting a directly attributable armed attack). Second, how attackers position financial stakes at the inception rather than conclusion of operational sequences, transforming “security incidents” into immediate, large-scale credit penalties upon public disclosure. Third, whether stable profit-recycling mechanisms exist between physical destruction and financial exploitation layers, enabling such attacks to self-finance and evolve into replicable, scalable operational models rather than one-off ventures. Fourth, and most uneasy for any sovereign entity or security alliance: do existing legal, financial regulatory, and counter-terrorism frameworks possess sufficient coupling capacity to identify and disrupt this closed loop? Or are they institutionally designed to remain disconnected, thereby structurally yielding space for such attacks to proliferate?

The contributions of this paper are as follows: Firstly, the author advances the concept of “grey zone hybrid warfare” beyond its classical definition as “military operations combined with information warfare” to a new level characterised by “discrete disruption networks coupled with financial repricing loops”, emphasising that credit itself has become a sustainable target for sustained attack. Second, we propose an operational model language (comprising physical discrete disruption networks, financial exploitation layers, disruption-pricing closed loops, and self-financing ratios) that transforms seemingly disparate event sequences into quantifiable, actionable, and intervenable systemic structures; Thirdly, we contend that the true defensive imperative lies not in “preventing every minor disruption,” but in severing the profitability of this closed loop. This renders it financially unsustainable, narratively non-scalable, and legally escalatable to sovereign-level threats, thereby opening legitimate windows for collective countermeasures and credit stability control. The fundamental implication of this perspective is that future national security defences will no longer be confined to physical borders or counter-terrorism measures like “preventing explosions.” Instead, they will constitute a composite firewall protecting state credit, financing capacity, and the legitimacy of social governance. Should a political community fail to establish real-time coordination between intelligence, financial regulation, legal characterisation, and public discourse clarification, it may remain in a state of treaty-defined “peace” while being effectively plunged into a state of “wartime” in fiscal and governance terms.

2. Theoretical Background and Literature Review

The grey zone is not merely an ambiguous area ‘between peace and war’, but rather a systematically employed competitive space: where state or quasi-state actors deliberately maintain low intensity and deniability to exert sustained coercion, altering an adversary’s strategic position while avoiding triggering conventional military responses or collective defence clauses under alliance agreements (Office of the Director of National Intelligence [ODNI], 2024; Mazarr, 2021). According to the US intelligence community’s 2024 updated definition, the grey zone constitutes an operational domain “deliberately operating below the threshold of open warfare.” Its defining characteristics include difficulties in legal attribution, cross-domain operational chains (information, economic, political, military), and objectives focused on undermining an adversary’s resolve, credibility, and effective governance—rather than territorial occupation or the destruction of main force units (ODNI, 2024). Similarly, the UK Parliamentary Defence Committee, in publicly defining “grey zone activities,” emphasises that their core purpose is not overt destruction but “the gradual erosion of a government’s functionality, credibility, and policy manoeuvring space through a series of hostile acts below the threshold of direct armed conflict.” This aims to force the targeted government into a position of political disadvantage before it enters a state governed by the laws of war (House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025). It is this form of strategic manoeuvring—rather than isolated attacks—that constitutes the primary pressure tactics currently employed between major powers.

Hybrid warfare has long been characterised as the “concurrent deployment of multiple instruments”—namely, the simultaneous mobilisation of military and non-military assets including propaganda, coercive diplomacy, intelligence operations, economic pressure, infrastructure sabotage, special forces/proxy militias, and cyber attacks—to advance strategic objectives without formal declaration of war (NATO, 2024; Hoffman, 2007/2022). The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation characterises it as “the synchronised combination of hard power, soft power, and intelligent power tools to exploit adversary vulnerabilities and achieve political objectives approaching the effects of war,” where disruption, coercion, and public opinion manipulation often run parallel to—or even supplant—traditional force projection (NATO, 2024; NATO, 2021). Institutions such as RAND further note that actors like Russia, China, and Iran do not merely stack “intelligence + propaganda + harassment” in practice. Instead, they deliberately design operations near threshold levels to prolong adversaries’ decision cycles, fracture their alliance systems, and constrain their domestic legitimate response space (Mazarr, 2021; Wasser, 2019). In other words, hybrid warfare is not a “low-cost version of conventional warfare” but rather a form of calculated manipulation: it relies on navigating between legal thresholds, political thresholds, and alliance treaty thresholds, making it difficult for the defending party to construct a morally and legally equivalent response (Mazarr, 2021; House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025). This strategy of “striking until the target nears collapse, yet preventing it from qualifying the action as war” constitutes the critical interface where grey zone operations and hybrid warfare converge in practice.

Traditional literature on grey zone/hybrid warfare has primarily focused on “visible coercive actions” such as information warfare, public opinion manipulation, energy coercion, proxy armed intervention, cyber disruption, and infrastructure interference (Mazarr, 2021; NATO, 2024; Wasser, 2019). However, recent security research increasingly emphasises that these actions are not isolated; they are increasingly embedded within financial structures, with finance itself being weaponised as part of conflict (Hybrid CoE, 2022).So-called ‘financial geopolitics’ no longer confines itself to conventional sanctions or currency rivalries between major powers. Instead, it treats the financial system itself—encompassing sovereign credit pricing, capital flows, risk premiums, and industrial valuation structures—as the battlefield. By shaping risk narratives and orchestrating the instantaneous redistribution of liquidity, it seeks to alter the strategic position of adversarial nations (Hybrid CoE, 2022).The European Central Bank’s regular assessments of financial stability vulnerabilities have repeatedly highlighted that market pricing can exhibit non-linear amplification effects during periods of high uncertainty: When markets are led to believe that a sovereign entity exhibits “diminished governance capacity” or “unsustainable critical industrial nodes”, sovereign financing costs and key sector valuations undergo steep reassessments within an extremely short timeframe. This reassessment itself exerts countervailing pressure on the nation’s fiscal space and political stability (European Central Bank, 2024).This implies that attackers need not destroy their adversaries’ forces, nor even articulate their political demands; it suffices to orchestrate a sequence of events within a narrow window that markets interpret as signals of systemic failure. while simultaneously placing pre-emptive bets on derivatives, sovereign credit default swaps, and sovereign bond spreads, they can couple the “deterrence-coercion” logic of grey-zone operations with the “repricing-punishment” logic of financial markets. This allows them to directly convert conflict outcomes into substantial profits, reinvesting these gains into subsequent operations. This “financial amplification chain”—transforming deniable, distributed disruptive actions into punitive pricing at the credit level—represents a critical gap in traditional hybrid warfare research that remains under-explored yet manifests in practice (Hybrid CoE, 2022; European Central Bank, 2024).From a security governance perspective, this gap is profoundly dangerous as it breaches existing divisions of responsibility: on the one hand, intelligence and counter-terrorism frameworks treat low-intensity infrastructure sabotage as a matter of “internal policing or extremist threats”; while the financial regulatory framework treats abnormal position-building, sovereign credit bets, and public opinion manipulation as “market manipulation” or “a rational reflection of geopolitical risk premiums”; simultaneously, the collective defence/alliance framework typically requires an “attributable armed attack” as the threshold for activation (House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025; Mazarr, 2021).

The result is that the aggressor finds itself precisely positioned at the juncture of three systems: legally, this still does not constitute a declaration of war; financially, however, it is sufficient to have the target nation re-priced as a high-risk sovereign entity, directly driving up its financing costs, compressing its fiscal manoeuvre room, and eroding its governing legitimacy (European Central Bank, 2024). This signifies that the grey zone is no longer confined to “information manipulation + minor harassment,” but has evolved into a synergistic structure of “discrete disruption networks + closed-loop credit repricing.” Similarly, the “multi-domain integration” of hybrid warfare transcends mere “firepower + information + legal warfare,” becoming a closed-loop coercion of “low-attributability physical interference + instantaneous financial market penalties” (NATO, 2024; Hybrid CoE, 2022). This research unfolds precisely at this intersection: we treat distributed, low-attribution disruption as the input to the grey zone, capital markets’ repricing of sovereign risk and corporate valuations as the output of hybrid warfare, and subsequently view the arbitrage, feedback, and reinvestment mechanisms between them as a sustainable strategic attack system rather than a one-off harassment event.

3. Conceptual Model and Key Variables

To elevate grey-zone hybrid warfare from a series of “mutually dangerous yet seemingly unrelated” tactics into a predictable, intervenable, and quantifiable systemic threat, this study proposes an analytical framework comprising two interlocking layers: the physical discrete disruption network and the financial exploitation layer. The coupled feedback chain between these layers is defined as the “disruption-pricing closed loop”. The core assertion of this framework is that, within the current security environment, the disruption of critical infrastructure is no longer an end in itself but has been weaponised as a trigger signal for financial repricing. Similarly, financial market volatility is no longer merely a by-product but has become the primary channel for both reaping attack profits and financing subsequent assaults (Hybrid CoE, 2022; European Central Bank [ECB], 2024; House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025).

The first layer, the Physical Disruptive Network (PDL), refers to a set of spatially dispersed, organisationally decentralised, and legally highly deniable small-scale infiltration and disruption units. These units execute synchronised or near-synchronised “accidental disruptions” against critical dependency nodes within target nations or economies, employing low-intensity yet high-visibility tactics (Hybrid CoE, 2022; Olech, 2025).These nodes are not selected at random, but are often situated at pivotal junctures within supply chains and structures of public confidence: energy supply, long-distance transport/ports, communications backbones, financial settlement channels, and civilian or flagship enterprises symbolising that “the state remains controllable” (European Commission & NATO, 2023; Olech, 2025). Joint assessments by NATO and the EU on critical infrastructure vulnerabilities have explicitly identified four sectors – energy, transport, digital infrastructure, and space assets – as possessing “cross-domain enabling” attributes. Should disruptions occur in two to three of these nodes near-simultaneously, the public and markets would cease viewing them as isolated incidents, instead interpreting them as “signs of state governance failure” (European Commission & NATO, 2023).

Similarly, hybrid threat analysis institutions note that hybrid/grey zone actors deliberately pursue “multi-point concurrency” and “cross-departmental interference”, as this exhausts defenders in political communication: they can no longer tell the public “it was merely a technical glitch”, but must simultaneously assume responsibility for multiple departments’ destabilisation within a narrow window (Hybrid CoE, 2022; House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025). In security modelling terminology, this signifies that PDL’s primary target is not “physical damage output” but “narrative density”: simultaneously making as many high-signal nodes as possible appear to fail concurrently, thereby casting doubt on state governance capabilities as a “systemic collapse” rather than an “isolated incident” (House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025; Olech, 2025).

This aligns with the latest assessment of critical infrastructure security within the NATO framework: threat actors are exploiting distributed, difficult-to-attribute disruption and harassment tactics to exert pressure on member states’ vulnerabilities “below the collective defence threshold”. Their objective is to erode resilience without crossing the traditional red line of an “armed attack” (NATO, 2024; Somogyi, 2025).The second layer, the Financial Exploitation Layer (FEL), represents a practical extension of the traditional ‘financial coercion’ paradigm: rather than observing market reactions post-event, attackers establish positions beforehand, amplify expectations during the event, and realise profits afterwards (Hybrid CoE, 2022; ECB, 2024). This layer encompasses three operational categories: (1) Establishing directional bets on key corporate equities, such as deeply out-of-the-money put options or structured short positions, ensuring that once a target firm is publicly labelled as a “security vulnerability/supply disruption risk source,” its valuation experiences significant abnormal negative returns within hours; Relevant research indicates that capital markets often exhibit non-linear reactions to security incidents, cyberattacks, terrorist attacks, or major disruptions: markets do not merely price direct physical losses, but rapidly internalise them as systemic discounts reflecting “inadequate governance capabilities” and “unsustainable supply chains” (Akyildirim, 2024; Jin, 2024; Muktadir-Al-Mukit, 2025).The application of event study methodology within the security-finance interdisciplinary domain has demonstrated this: short-window abnormal returns frequently exceed the immediate financial losses stemming from the event itself. This disparity arises not from book value impacts, but rather from the market’s rapid repricing of long-term credibility, regulatory capacity, and operational continuity within an extremely brief timeframe (Akyildirim, 2024; Jin, 2024; Muktadir-Al-Mukit, 2025). In other words, FEL is not about “profiting from market volatility after an attack occurs,” but rather “using attacks to generate market volatility itself”—effectively treating the market pricing function as the target.

(2) At the sovereign credit level, attackers may employ sovereign credit default swaps (CDS) or government bond spread trades to wager on rising financing costs for the target nation (ECB, 2024). Once PDL creates the perception of “national governance capacity being weakened” at critical junctures such as energy, logistics, and communications, rating agencies, sell-side research, and hedge funds will swiftly frame this as “structural risk,” thereby driving up sovereign risk premiums within an extremely short timeframe. This would compel the targeted nation to endure quasi-wartime refinancing pressures before any formal recognition of an attack, necessitating higher interest rates to finance equivalent emergency fiscal measures (ECB, 2024; European Commission & NATO, 2023). This constitutes a strategic inversion: the Treasury is thrust into wartime footing, yet the Ministry of Defence cannot legitimately declare “we are at war,” while the alliance system struggles to respond within the collective defence framework (House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025; NATO, 2024).

(3) Within the realm of public discourse and information channels, FEL employs structured narratives to translate PDL-triggered localised incidents into evidence of systemic collapse: not “a port fire”, but “penetration of the national logistics hub”; not “a chemical plant explosion”, but “the regulatory system has failed”; not “a network outage”, but “critical infrastructure can be shut down at any moment” (Hybrid CoE, 2022; NATO, 2024; Somogyi, 2025). This narrative is not mere psychological warfare but a precondition for financial engineering: financial markets price based on expectations rather than facts. Thus, the more persuasive the narrative of “state collapse,” the steeper the subsequent valuation downgrades and the slope of sovereign credit risk premium increases. Open market operations are thus manipulated as “second-round firepower,” not merely passively reflecting security incidents but actively amplifying their political and credit implications (ECB, 2024; Hybrid CoE, 2022).

The crucial point is that these two layers do not operate through loose coordination, but rather form a sustainable profit circuit—what this research institute terms the ‘Disruption-Pricing Loop’ (DR-Loop). The logical sequence of this closed loop is as follows: FEL initiates downward bets; PDL executes multi-point disruptions against several high-signal nodes within a narrow time window; FEL and its public relations extension narrativise these disruptions as ‘systemic governance failure’, compelling capital markets to interpret localised shocks as evidence of structural risk; Markets react spontaneously with abnormal negative returns and widening sovereign credit spreads; attackers then realise financial gains; these proceeds in turn fund the next cycle of infiltration, intelligence gathering, logistics, recruitment, outsourced operations, and technological upgrades (Hybrid CoE, 2022; ECB, 2024; United States Department of the Treasury, 2024). This‘reinvestment of gains’ characteristic exhibits structural similarities to the financial cycle logic described in counter-terrorism financing: hostile organisations do not engage in one-off fundraising but instead bind economic activities (legitimate or illicit) to operational capabilities within a self-replicating financial chain. This chain relies on sustained cash flow to maintain attack cadence and survivability (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime [UNODC], 2024; Financial Action Task Force [FATF], 2024). The distinction lies in the fact that the DR-Loop does not finance traditional terrorist operations per se, but rather transforms the international capital markets themselves into an ATM for attacks: action—panic—repricing—cash-out—expansion.

To provide an operational strategic quantification of this closed-loop system, this paper proposes three key variables and metrics. First, the market overreaction coefficient β: this denotes the magnitude of financial repricing triggered by a unit physical disturbance, specifically the ratio of abnormal returns generated by a single disruption event within a short window to the objective physical losses incurred by that event (Akyildirim, 2024; Jin, 2024; Muktadir-Al-Mukit, 2025). β reflects the capacity for narrative amplification—the greater the ability to frame a local incident as systemic failure, the higher the β. In grey zone conflict scenarios, the objective of actors is not singular destruction but elevating β, compelling markets to penalise the entire nation through ‘systemic risk discounting’ rather than punishing individual enterprises alone (Hybrid CoE, 2022; ECB, 2024).

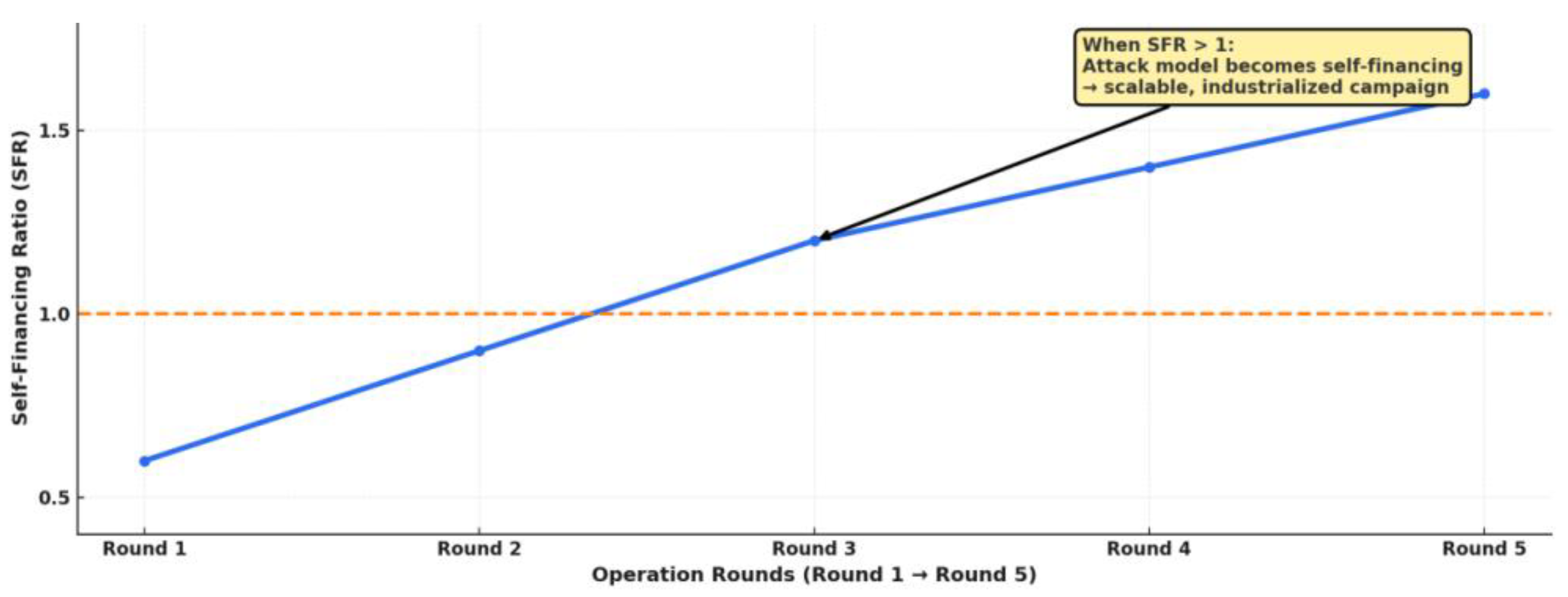

Second, the Self-Financing Ratio (SFR): This denotes the ratio of net proceeds an attacker can realise from the market during a single operation to the total cost of orchestrating that operation (United States Department of the Treasury, 2024; FATF, 2024). When SFR > 1, it signifies that the attack model itself is financially sustainable or even scalable: the proceeds not only cover the costs of the operation itself but also provide incremental resources for the next round. This characteristic represents a paradigm shift, as it indicates that adversaries no longer rely on state budgets, external funding, or fixed donor networks. Instead, they have financialised and industrialised attacks, transforming them from one-off strategic operations into routine strategic tools (UNODC, 2024; FATF, 2024).

Third, Credit-Layer Lethality: This denotes the speed and magnitude of downward revisions to a target nation’s sovereign credit spreads (sovereign default risk premiums) and key corporate market capitalisation within an extremely short timeframe following an attack (ECB, 2024; European Commission & NATO, 2023). Where traditional military metrics gauge combat effectiveness by “destruction levels,” this indicator measures coercive impact through “the rate at which markets reprice a nation’s governability and fundability.” Higher credit-layer lethality compels target governments into accelerated fiscal emergency modes, renders conventional political rhetoric less effective in reassuring markets, and may even strip them of stable financing capacity before legally attaining “attacked” status (ECB, 2024; House of Commons Defence Committee, 2025). From a national security perspective, this metric itself equates to “strategic lethality”: it does not destroy ports, but destroys your borrowing credentials.

In summary, PDL and FEL should no longer be interpreted as a linear relationship of ‘security incidents + financial consequences’, but must be understood as a cyclical system where ‘disruption is a weapon of pricing, and pricing is a projection of firepower’ (Hybrid CoE, 2022; NATO, 2024; ECB, 2024). For a nation or political community, the true peril lies not merely in the attack itself, but when β is artificially elevated, the SFR remains persistently above 1, and the lethality of credit ratings escalates exponentially. At this juncture, the aggressor no longer requires conventional warfare logic to force you into a fiscal and governance critical state. Defence then ceases to be about ‘preventing explosions’ and becomes about ‘breaking the closed loop’.

4. Research Methods and Design

This study adopts a three-tiered parallel methodological approach encompassing “security engineering—financial response—strategic sustainability”. Its objective is not to reiterate threat narratives, but rather to characterise the operational structure, impact mechanisms, and sustained resourcing capacity of hybrid warfare in the grey zone in a verifiable manner.

The research subjects are focused on three categories of systemic vulnerability units:

(1) Critical infrastructure nodes possessing narrative amplification value for national operations and public security perceptions (energy hubs, port/shipping centres, long-distance logistics pipelines, backbone communications/data centres, leading enterprises regarded as ‘symbols of national capability’);

(2) The corresponding valuation anchors for these nodes in capital markets (listed parent companies, core industrial chain firms with highly visible market capitalisation, key suppliers undertaking state-owned functions, systemically important financial institutions);

(3) Sovereign credit itself (government bond yields, sovereign credit default swap pricing, instantaneous slope of sovereign risk premium). In other words, we conceptualise the attack chain as a layered construct propagating from ‘physical nodes’ to ‘valuation nodes’ and ultimately to ‘national credit nodes’, constructing distinct analytical modules for each tier. The research comprises two interlocking dimensions: qualitative modelling and quantitative measurement. The qualitative component establishes theoretical frameworks, identifies mechanism assumptions, and deduces adversarial tactical logic. The quantitative component tests whether these assumptions manifest as repeatable statistical patterns in the real world (or simulated environments), while estimating the amplification factors and persistence of shocks.

Part One: Discrete Disruption Network Simulation – Qualitative Approach with Structured Quantitative Metrics. We model critical infrastructure, logistics, and reputation-sensitive enterprises (i.e., those whose failure would signal to the public whether the state remains in control) as a weighted directed graph. Nodes represent specific targets (e.g., fuel transfer units at ports, regional grid dispatch centres, core reaction zones at major chemical plants, national backbone fibre optic convergence points, strategic production facilities for national brands); edges represent functional dependencies (supply chain reliance, public opinion connectivity, technological/energy coupling, political symbolism coupling). This network does not equate to traditional “critical infrastructure topology”, but rather constitutes a “narratively visible vulnerability topology”: prioritising nodes that, should incidents occur, would be automatically linked by media, social platforms, and markets – rather than those with the greatest objective losses yet low visibility. Methodologically, nodes were first qualitatively annotated as ‘systemic markers’ within political discourse and public perception (e.g., largest national ports, national telecommunications backbones, industrial flagships officially designated as ‘symbols of national modernisation’). These nodes were then assigned three fundamental attributes: (a) Visibility weight: likelihood of public/media attention and national narrative prominence in the event of disruption; (b) Interdependence weight: whether the node’s disruption would be interpreted as indicating high risk for other nodes (e.g., a port fuel fire is often automatically linked by media to national energy security, not merely the port itself); (c) Deniability: Whether an interruption could be framed as an ‘accident,’ ‘maintenance failure,’ or ‘regulatory oversight’ rather than an ‘external attack.’ Based on these attributes, we can qualitatively reconstruct the attacker’s target selection function without relying on classified military data: it does not maximise physical destruction but rather maximises the narrative concentration of ‘multiple anomalies’ within a short time window. Subsequently, we simulate synchronous disturbance scenarios across this network: simultaneously marking multiple high-visibility nodes as ‘disrupted’ within the same timeframe, observing their narrative coupling (whether they are automatically linked by the public/media/political opposition as ‘national-scale collapse’). The output of this step is not a probabilistic forecast, but a structural vulnerability map: identifying which node combinations, when impacted on the same day or within the same news cycle, would be automatically categorised by domestic and international discourse as ‘total governance failure’. This step is qualitative—its role is to provide a set of hypotheses for subsequent quantitative analysis regarding ‘where attackers might strike and how many points simultaneously’, rather than asserting ‘who will attack whom’.

Part Two: Market Impact and Credit Repricing Analysis – Quantitative Dominance. Based on the “high narrative coupling node combinations” identified in Part One, we treat these as impact events and employ an event study framework to quantify the corresponding financial reactions. In classical event studies, we define “abnormal returns” at a specific time point t₀: the actual returns of a company/sector/index at t₀ and within its surrounding window (e.g., t₀±1 day, t₀±3 days, t₀±5 days), minus the normal returns predicted by the benchmark model. Here, we extend this method to three levels: (1) Firm level: whether the affected key firm (or its listed parent company) exhibits a significant negative abnormal return, and whether the magnitude substantially exceeds the reasonable direct asset loss value; (2) Sector/supply chain level: whether “contagion-like” abnormal returns occur, i.e., whether other peer firms, suppliers, upstream/downstream contractors, or market-cap-weighted sector ETFs/index funds not directly impacted by the physical shock also experience synchronised sharp declines; (3) Sovereign Level: Whether the target nation’s sovereign credit default swap (CDS) spreads, government bond yield curves, or sovereign risk premiums steeply rise within an extremely short timeframe. By simultaneously observing these three tiers, we define three quantitative metrics to address the question: “Is discrete disruption genuinely treated as a systemic collapse signal within capital markets?”

Market Overreaction Coefficient β: Magnitude of abnormal returns / Scale of direct economic losses from the physical shock. Should β substantially exceed 1, it indicates the market is not pricing the “incident” itself, but rather pricing “governance failure”; in other words, the attackers have successfully packaged a localised event as a national-level risk.

Transmission Depth D: The number of transmission tiers from the directly impacted enterprise to its peer sector, upstream/downstream supply chains, and ultimately sovereign credit. A greater D indicates that a single point of failure is more readily interpreted by the market as “systemic fragility” rather than an “isolated disaster”.

Credit-grade kill speed λ: The upward slope of sovereign borrowing costs (such as government bond yields or CDS spreads) within a short time window. A higher λ indicates that the attack has transcended the corporate level, effectively rewriting the nation’s risk profile and propelling the government into a state of fiscal emergency without any legal declaration of war.

This section constitutes a strictly quantitative assessment: it is not concerned with ‘who did it’, but rather with whether ‘the market was compelled to believe the state had lost control’. Should the answer be affirmative, it signifies that discrete sabotage and information steering were indeed sufficient to trigger a credit repricing, with financial markets acting as ‘remote firepower’ rather than mere bystanders.

Part Three: Closed-Loop Sustainability Assessment—Integrating qualitative strategic logic with quantitative financial outcomes to address a critical security question: Can this attack pattern sustain itself through self-financing and replicate expansively, or is it a one-off expenditure? To this end, we introduce the Self-Financing Ratio (SFR): SFR = (Net proceeds realised by the attacker from financial markets during this round of impact) ÷ (Total marginal cost of executing this round of operations). Here, “net proceeds” encompass: short-selling gains, option exercise proceeds, and re-pricing gains from sovereign credit instruments; while “costs” include: intelligence gathering, infiltration deployment, operational execution, public opinion steering, remuneration for external actors, and risk premiums. Should SFR > 1, this signifies the model can self-sustain like a commercial enterprise: arbitrage profits from the previous cycle finance the next round of more complex, widespread, and harder-to-defend disruption and narrative manipulation. This constitutes the threshold by which this study determines whether a set of grey-zone hybrid warfare tactics has escalated from a “tactic” to a “structural threat”. The security implication is this: once the SFR consistently exceeds 1, it ceases to be a one-off coercive act and becomes an “industrialised attack”. In other words, states no longer face a tactical actor but an economically replicable and scalable “disruption-pricing” supply chain.

From a research methodology perspective, the three components do not follow a linear sequence but rather constitute a closed-loop verification process: the first part presents structural hypotheses (qualitative) regarding where and how attacks might occur; the second part tests whether markets genuinely react with panic according to this attack logic rather than treating it as a random incident (quantitative); the third part measures whether the returns are sufficient to sustain the next round of operations (combining quantitative analysis with strategic interpretation). This enables us to reposition hybrid warfare in the grey zone from a narrative of public opinion back into an analytical model: it ceases to be merely “adversaries causing trouble” and can instead be expressed as a dynamic system with observable inputs (multi-point discrete disruptions), quantifiable intermediate variables (abnormal returns, sovereign credit repricing), and discernible outputs (SFR > 1 indicates sustainability). Crucially, this methodology does not depend on identifying the perpetrator. Even where political or legal attribution proves impossible, national security and financial regulatory bodies can employ this framework to monitor three real-time questions: whether multi-point disruptions of high narrative value are occurring; whether markets are interpreting these disruptions as structural collapse and rewriting sovereign credit accordingly; and whether such rewriting has been adopted by adversaries as a reinvestable business model. At the policy level, these three questions correspond respectively to tactical early warning, financial stability response, and state-level deterrence design.

5. Analysis and Deduction

To validate the framework of “discrete disruption networks—financial exploitation layer—disruption—pricing feedback loop” and demonstrate its practical strategic implications, this section employs scenario-based analysis to delineate two prototypical attack vectors: the industrial strike path and the sovereign strike path. These paths are not mutually exclusive but represent two distinct focal modes of the same operational logic: the former targets industry—supply chains—public confidence, while the latter targets fiscal systems—sovereign credit—the legitimacy of governance. Their commonality lies not in the scale of physical destruction, but in “whether they can compel capital markets to interpret localised incidents as structural collapse within a brief window”. This forces a nation, which politically may still claim a “state of peace”, into an economic “state of credit warfare”.

Scenario One: Disruption of Critical Industrial Chains and Corporate Valuation Reset

In this approach, the attacker’s objective is not to destroy the production capacity of individual enterprises per se, but to undermine market confidence in the stability of entire industrial chains through multi-point, synchronised, and deniable “accidental disruptions”. The operational sequence unfolds as follows: Between T-7 and T-3 days, the Financial Exploitation Layer (FEL) has positioned deep out-of-the-money put options or other directional short positions across leading enterprises within the target industry and their high-market-cap upstream/downstream counterparts. These positions can superficially be disguised as hedging strategies or high-volatility bets, thus not constituting “obvious hostile acts” at the regulatory level. At T-0, the Physical Discrete Destruction Network (PDL) triggers multiple events near-simultaneously:For instance, an “industrial fire” erupting in the fuel transhipment zone of a major port; a “communication failure causing dispatch chaos” at a national logistics/cold chain hub; a sudden “workplace safety incident” at a critical facility of a flagship chemical or energy enterprise; or a “localised supply disruption” at a large-scale food, fuel, or telecommunications provider regarded as a “symbol of public stability”. Viewed individually, these incidents could be characterised as “isolated operational mishaps,” “regulatory lapses,” “maintenance failures,” or “subcontractor mismanagement” – none meeting the legal threshold for “armed attack.” The critical factor lies not in isolated events, but in their pattern: occurring within the same news cycle, spanning multiple physical locations and sub-sectors, and collectively signalling that “the nation’s foundational supply infrastructure is failing.”Driven by social media and secondary information channels (which are pre-set as narrative amplifiers in FEL), public opinion no longer perceives these incidents as unrelated operational issues. Instead, it has begun piecing them together as evidence of “systemic infiltration” and “widespread disruption already unfolding within the country”.At this juncture, the behavioural logic of capital markets does not involve calculating losses item by item, but rather collectively downgrading valuations through a “sustainability discounting” approach: the question is not “How much inventory has this factory lost?”, but rather “Can this nation still guarantee sustained supply? Is the regulatory framework still credible? Is this company now permanently exposed to uncontrollable disruption risks?” The result is often a synchronised sell-off across entire sectors, even including peers unaffected by physical incidents, simply because the market is led to believe “this industry now resides within a nationally uncontrollable risk zone.” Statistically, such synchronised sell-offs manifest as high beta: the magnitude of abnormal negative returns far exceeds the direct financial losses from the incident itself. They also exhibit high propagation depth D: the downturn no longer confines itself to the affected enterprise but spreads laterally across the supply chain and vertically through the nation’s overall business credibility.

For the attackers, this decline itself marks the moment of realisation: FEL liquidates or transfers these bearish positions, locking in profits. These gains then become the funding pool for the next round of operations. For the targeted nation, what proves more fatal than the short-term share price drop is the valuation system being forced to incorporate the notion that “this is not an accident, but a structural risk of the new era.” This effectively rewrites the target industry’s cost of capital curve, thereby reshaping its bargaining power within global supply chains. In other words, through a series of “medium-scale incidents,” the attackers reshape the risk profile of an entire industry within hours. This label often becomes entrenched in public discourse and investment banking reports, persisting far longer than the actual recovery period from the incidents themselves.

Scenario Two: Sovereign Credit Downgrade and Fiscal Position Reversal

In the second pathway, the attackers are not content with depressing the valuations of enterprises and industrial chains; instead, they directly target the nation’s own financing capacity, the credibility of its public governance, and its narrative of political control. The modus operandi remains the same: first establish positions, then fabricate evidence. From T-10 to T-5 days, the FEL commences positioning in sovereign credit derivatives (such as the nation’s credit default swap contracts) and government bond yield spread trades, betting on rising refinancing costs and widening sovereign risk premiums for the country. Subsequently, at T0, PDL need not execute large-scale, directly attributable military destruction, but instead orchestrates a series of “nationwide symbolic foundational layer” disruptions. Examples include: brief offline incidents at electricity load balancing centres; “technical delays” in national data exchange or settlement systems; forced temporary rerouting of cross-border energy or aviation arteries (causing short-term supply and logistics quotes to spike); and explosions/fires/shutdowns in major metropolitan areas described as “critical infrastructure security management failures”. When deployed at the narrative level, these phenomena would not be framed as isolated facility incidents, but rather portrayed as: - “State failure to maintain continuity of critical functions” - “Internal infiltration breaching security thresholds” - “Government deliberate suppression of truth”

The true objective of this narrative has never been to intimidate the populace itself, but rather to signal to external capital: the nation is sliding from being a “governable, financeable medium-risk sovereign entity” towards becoming a “structurally high-risk sovereign”. Capital markets’ repricing of sovereign credit relies heavily on this perception. Once external capital and rating discourse begin interpreting such events as harbingers of governance collapse, credit default swap (CDS) spreads widen rapidly, government bond yield curves steepens, and refinancing costs instantly take on wartime characteristics without any formal declaration of “wartime conditions”. The Treasury is thus compelled into emergency mode: issuing high-cost short-term debt, drawing on reserves, pledging to underwrite critical enterprises and public services, or even hastily announcing security reconstruction plans to placate public opinion and markets. This effectively amounts to forcing the counterpart to activate a “post-war reconstruction mode” fiscally, while politically remaining in a state of “peace”. The irony lies in the fact that, legally speaking, the target nation struggles to classify these actions as an “external armed attack.” Consequently, it finds it difficult to demand collective security responses under international law or to legitimise comprehensive security measures domestically. Yet, in financial reality, it is already footing the bill for a “nation under attack.”

These two scenarios share three overlapping structural characteristics. Firstly, the targets of attack are ‘anchors of confidence’, not ‘production hubs’. Whether leading enterprises, critical logistics nodes, or state-level infrastructure, they are struck not because they represent physical bottlenecks, but because they embody the symbolic function of ‘the state retaining control’. In other words, the targets are political-financial narrative coordinates, not purely technical nodes. Second, the temporal structure of these actions follows a sequence: “first plant financial detonators, then manufacture news material, finally trigger market self-punishment” – rather than “strike first, then observe market reactions”. This transforms destructive operations from “cost expenditures” into “revenue sources”, endowing them with replicable commercial logic. Thirdly, command authority over finance and security is deliberately misaligned: governments must respond immediately on the fiscal front (stabilising confidence, underwriting systems, stemming market bleeding), yet lack the legal standing to declare themselves “under attack” in security terms. They may even fail to secure collective defence political backing within alliance frameworks. This misalignment constitutes the strategic space the attackers genuinely seek, as it traps the targeted nation in its most vulnerable state: compelled to deploy wartime resources without the authority to exercise wartime powers.

In summary, the above analysis demonstrates that grey zone hybrid warfare is not a loose amalgamation of ‘terrorism plus hedge funds’, but rather a strategic-level operational paradigm with a clear profit model, distinct rhythmic structure, and explicit political intent. Its objective is not a single decisive blow, but rather to compel adversaries to prematurely shoulder war-level fiscal and credit costs without legal legitimacy through a series of deniable, localisable, and publicly manipulable discrete incidents. Its core principle is: to destroy your sovereign credit without destroying your air defences; to force fiscal bleeding without compelling you to admit “we are under attack”; to render your capital markets, rating systems, industrial capital costs, and internal political accountability mechanisms the primary instruments of attack, supplanting missile trajectories. For any national security apparatus still operating under the worldview that “crossing a border equals the commencement of war,” such scenarios demonstrate: conflict no longer awaits border violations. It manifests directly, embedded within your energy systems, your logistics networks, your market pricing logic, and your fiscal nervous system.

6. Defence and Policy Implications

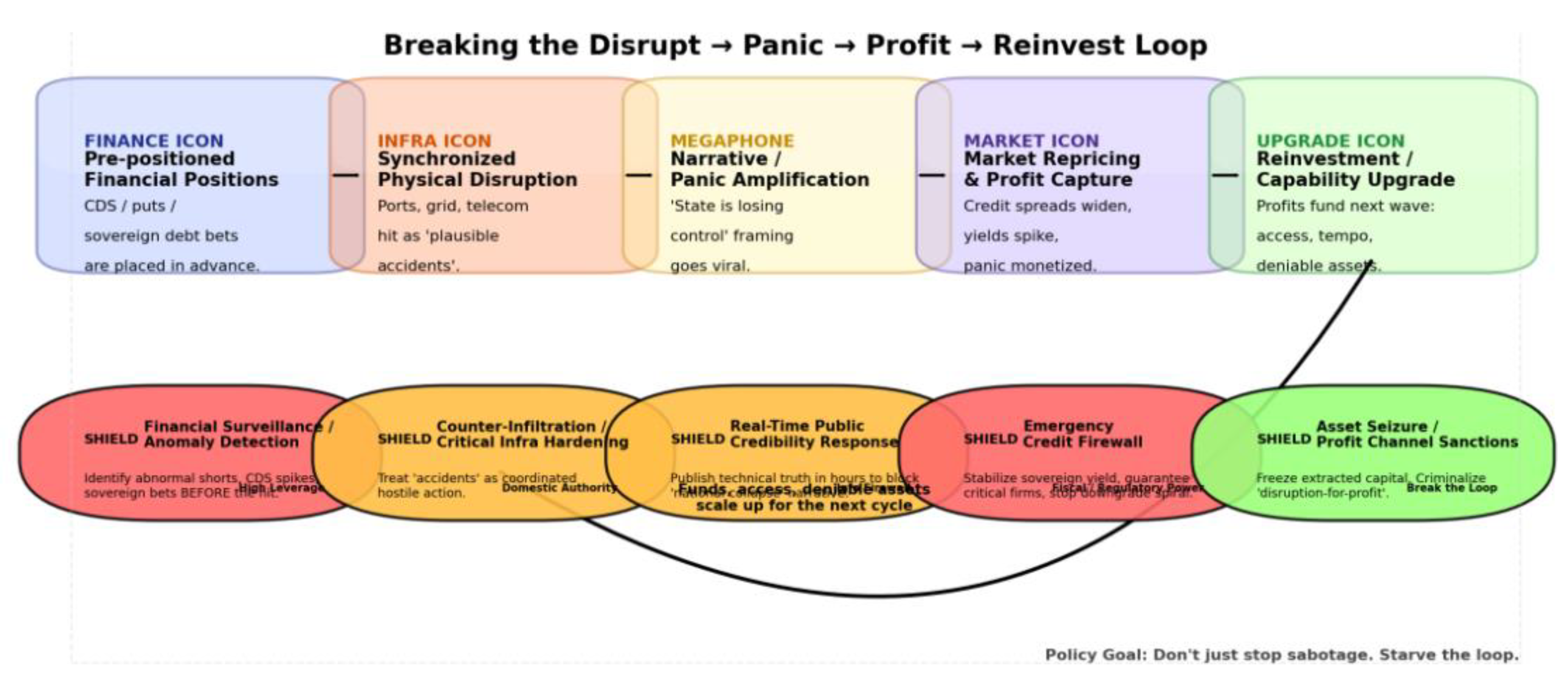

If the traditional defence paradigm assumes that “we counter armed aggression with military law, domestic subversion with police law, and market manipulation with financial regulation,” then the reality revealed in the previous section is this: attackers have learned to navigate between these three lines of defence, rendering any single-system response both excessive and unlawful, lagging and inadequate. Precisely for this reason, the core task in defending against hybrid warfare in the grey zone is not primarily to “apprehend the mastermind,” nor even to “prevent every act of disruption.” Rather, it is to dismantle the adversary’s profit logic, forcing the “disruption-pricing loop” to remain open and thereby rendering it unsustainable. This can be understood as a shift from “preventing attacks” to “bankrupting the adversary’s business model.” At the national security level, this transition represents a near-paradigm shift: the focus is no longer merely on safeguarding the infrastructure itself, but on protecting the nation’s credit curve, financing capacity, and narrative dominance.

The first line of defence must be established at the intersection of intelligence, financial regulation and public narrative, rather than solely at the ‘counter-terrorism frontline’. Traditional national security and intelligence structures remain accustomed to categorising infrastructure sabotage, arson, explosions, and system crashes as “security incidents”; treating abnormal option positioning, CDS expansion, and sector-wide short selling as “market behaviour”; and viewing the proliferation of narratives about “state collapse” or “regulatory failure” as “information warfare” or “disinformation” issues. This division of labour was once rational—today it presents attackers with a perfect seam. The foremost policy imperative is not merely “enhancing cross-departmental coordination,” but institutionalising a joint analysis unit capable of real-time, synchronised signal sharing within a single clock cycle. Its remit must span: critical infrastructure security alerts; monitoring anomalous positions in derivatives and sovereign credit markets; and structured fingerprinting of social narratives. Its mission is not to trace “who did it,” but to answer a more critical question: Are we within a potential closed-loop operational cycle? That is, are we witnessing the simultaneous emergence within the same window of: (1) multi-point, low-intensity, deniable disruptions at critical nodes; (2) pre-existing large-scale directional bets; and (3) a unified narrative template of “state governance failure.” This effectively shifts the question of “whether a state of war exists” from legal adjudication to situational recognition: it does not await a declaration of war or acknowledgement of attack, but instead flags the adversary as engaged in a systemic strike cycle before they can reap their harvest. Only through such pre-emptive identification is it possible to release credible counter-narratives, issue regulatory warnings, or implement temporary trading restrictions before capital markets complete comprehensive repricing, thereby disrupting the herd mentality’s self-amplifying effect.

The second line of defence involves resetting legal and treaty thresholds, particularly within multilateral or alliance security frameworks. The triggering criteria for collective defence clauses have traditionally centred on Cold War-era indicators such as “armed attack”, “territorial violation”, and “ clearly attributable hostile acts” – quintessential Cold War-era indicators. This affords the aggressor a costly yet secure corridor: it may execute multi-point sabotage within the target nation’s territory, directly striking critical industries and public infrastructure, even forcing the target’s finances into emergency mode. Yet it simultaneously maintains the legal façade of “accidents,” “law and order issues,” or “regulatory failures,” thereby denying the victim state the political legitimacy to request collective countermeasures. This implies that if the alliance’s defence logic remains anchored in the notion that “it’s not our problem unless shots are fired across borders,” the alliance itself will be progressively forced into the role of a credit co-signer: perpetually stabilising the situation for member states through political endorsement, reinsurance, and public opinion management, yet lacking the legitimacy to implement deterrent countermeasures. The policy implication is straightforward: the alliance must recognise that “systemic destruction of critical infrastructure combined with coordinated short-selling targeting sovereign credit and corporate valuations” constitutes a direct assault on member states’ national security and fiscal sovereignty, not merely a public safety incident. Such recognition does not necessitate an immediate military response, but it must authorise a comprehensive suite of collective countermeasures as legally deployable instruments. These include coordinated financial investigations, joint sanctions, cross-border asset freezes, joint law enforcement against suspected funding networks, cross-border digital controls on information amplification nodes, and—in extreme circumstances—the deployment of conventional military presence or cyber countermeasures as deterrent signals. In essence, this elevates “attacking your credit” from a policing matter to a sovereign issue, thereby raising the strategic costs for the adversary to an alliance-level challenge rather than allowing it to remain confined within the narrative space of “this is merely your domestic mismanagement.”

The third line of defence involves establishing a ‘credit firewall’ at the most vulnerable nodes within the nation. Traditional critical infrastructure protection logic centres on “building redundancy, withstanding shocks, and ensuring physical continuity.” Yet confronting this hybrid model demands safeguarding not merely physical continuity, but the market’s conviction in continuity itself. Practically, this entails pre-emptively equipping a select few entities possessing “narrative anchor” status (national port operators, national power dispatch hubs, national payment clearing networks, and symbolic national flagship enterprises) with three capabilities. First, ultra-high-speed trusted disclosure channels: should an incident occur, within tens of minutes to hours, the entity with the highest public trust (not corporate PR departments) must externally communicate details, causes, and resolution progress. At the technical level, it must demonstrate that “the incident has been contained,” preventing markets and the public from automatically extrapolating a narrative of “systemic penetration.” This is not “public appeasement” but beta suppression—curbing the amplification factor whereby markets convert localised damage into systemic discounts. Second, pre-established safety nets: such as emergency reinsurance, sovereign guarantee frameworks, and industry-wide stability mechanisms. These ensure markets do not interpret isolated incidents as “permanent bleeding for the firm with no rescue in sight”. This is not charity, but capital pricing: if investors believe the government has committed to stemming losses, the sell-off curve flattens and the credit-grade damage (the upward slope of sovereign spreads) diminishes. Consequently, the “panic premium gains” attackers could harvest from options, CDS, and government bond spreads are compressed. Third, narrative containment: pre-define “what constitutes systemic risk and what does not,” and immediately anchor each disruption within the “manageable, contained” framework upon occurrence. This directly blocks the “state failure” narrative template from entering mainstream financial discourse. This effectively integrates public opinion management and investor relations into the protection of critical infrastructure itself, rather than relying on post-event PR. Its purpose is clear: to prevent attackers from framing a fire or a shutdown as evidence of “state governance collapse” and incorporating it into short-selling reports.

The fourth line of defence involves intercepting the funding chain, structurally suppressing the attacker’s self-financing ratio. The methodology section earlier introduced a core metric: the Self-Financing Ratio (SFR), which measures the ratio of proceeds realised by the attacker from financial markets to the total cost of executing a cycle of disruption-narrative-amplification operations. Whilst the SFR remains consistently above 1, this model ceases to be a one-off political instrument and instead becomes replicable and scalable like an industry. In other words, it transforms from a “strategic operation” into a “sustainable business model” – one that can even be outsourced or franchised, evolving into a grey economy within geopolitical conflicts. The task at the state level is to drive the SFR below 1, ideally well below 1. How can this be achieved? The key lies not in deploying “counter-explosives specialists and additional police”, but in prioritising the adversary’s cash-out mechanisms through financial and law enforcement systems: Rapidly freezing fund flows directly linked to anomalous positions; Clearly defining the combined actions of “causing systemic disruption within a nation’s borders while making directional bets against its sovereign credit or critical enterprises” as a primary threat rather than ordinary market misconduct, thereby incorporating it into Counter-Financing of Terrorism (CFT) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) frameworks; where necessary, severing cross-border channels for repatriating such proceeds through international judicial cooperation. Externally, this resembles “combating terrorist financing”; Essentially, it transforms adversaries’ disruptive proceeds from recoverable profits into toxic assets bearing high confiscation risk. Once this risk perception becomes entrenched within the attack ecosystem, executing such operations ceases to be a guaranteed quick profit and instead becomes a high-exposure, high-freeze-rate bad business, naturally suppressing the SFR. The attack model loses its financial self-sustaining capacity, and the entire closed loop is deliberately severed.

These defensive approaches point to a clear conclusion: in confronting hybrid warfare in the grey zone, the line of defence for sovereign security is no longer confined to military and police boundaries, but constitutes an entire cross-domain line of credit. This spans situational awareness (whether we are caught in a closed-loop operation), legitimacy authorisation (whether we can treat this as a sovereign threat warranting allied support), market belief management (whether we promptly provide markets with a credible, financeable narrative that ‘the situation remains controllable’), and capital diversion (whether we can transform the aggressor from a profitable entity into a high-risk financial criminal). In other words, modern defence no longer aims to prevent a single port from burning, but to prevent the “port burning” from being interpreted by financial systems, rating agencies, and domestic political systems as evidence of “state failure” – and consequently being immediately shorted, priced, arbitraged, and reinvested. As long as this chain of interpretation is severed, adversaries cannot convert low-intensity disruption into high-leverage credit damage; Once this profit model is rendered bankrupt, adversaries struggle to elevate such attacks from one-off shocks to routine strategic tools. For any national security framework still treating “visible missiles” as the primary threat, this shift may feel uncomfortable, yet it constitutes a condition for survival. For within this strategic framework, you may find yourself defeated financially before firing a single shot.

7. Research Findings

We stand upon a perilous yet insufficiently acknowledged threshold: the primary battleground for national security has shifted from territory, air supremacy, and supply lines to credibility, financing capacity, and the very legitimacy of governance itself. The core contention of this paper is starkly direct: grey-zone hybrid warfare is no longer confined to the outdated paradigm of “low-intensity harassment plus information warfare.” It has evolved into a profitable, cyclical, and scalable system of strategic coercion. Its lethality is not measured by the number of targets destroyed, but by the extent to which a sovereign entity is simultaneously persuaded by capital markets, rating systems, and its own domestic public to be a “failing state.” We demonstrate this not as rhetoric but as structure: attackers first plant bets within financial markets, then deploy highly dispersed, deniable disruptive units to synchronously target critical infrastructure, logistics, and civilian-symbolic nodes. Subsequently, narrative manipulation packages these disruptions as evidence of “systemic governance failure,” compelling markets to rapidly and collectively revalue key enterprises and sovereign credit negatively. The outcome is not merely a short-term public relations crisis, but a fiscal and legitimacy crisis: the targeted government remains legally in a state of peace, yet is economically forced into a wartime financing posture. It must underwrite energy, logistics, supply chains, and social stability at heightened costs while bearing the narrative pressure that “the government has lost control.” This situation is strategic because it achieves what previously only war could accomplish—forcing sustained fiscal bleeding in the adversary, eroding industrial confidence in capital, and undermining the ruling party’s image of governance—while avoiding triggering any traditional collective defence clauses or retaliatory thresholds.

The second key finding of this study is that this model is dangerous not merely because it can strike a nation, but because it can replicate itself. We have coupled the Physical Disruption Layer (PDL) with the Financial Exploitation Layer (FEL) into a “disruption-pricing closed loop”, demonstrating that as long as the loop’s Self-Financing Ratio exceeds 1, the attacking party is no longer constrained by national will, long-term political objectives, or external funding networks. Instead, a “structural erosion business” emerges: one that can be deployed on demand, targeted regionally, accelerated by opportunity windows, and even executed by semi-autonomous contractors. In essence, the security threat is downgraded from “whether an adversary nation is resolved to confront you” to “whether someone deems it a high-return venture”. From this moment, national security is downgraded from a geopolitical issue to one of market incentives – a development that is devastating to any traditional deterrence logic. Classic deterrence relies on cost calculations: I make you believe the cost is unbearable, so you restrain yourself. But if the attack itself possesses sustainable self-funding capabilities and can operate like a grey industry, then “unbearable cost” must be imposed on commercial logic, not just military logic. In other words, the target of deterrence is no longer merely the political will of the actor, but its business model.

The third conclusion is prescriptive: any government attempting to reassure itself with the notion that “we shall better protect our infrastructure” has, in fact, already fallen behind by an entire era at the strategic level. Adversaries never seek the complete paralysis of your ports, but rather that your bond markets believe your ports could be paralysed at any moment. Nor do they aim to shut down your enterprises permanently, but rather to convince your investors that your enterprises’ risk premiums will rise persistently – thereby elevating your capital costs and suppressing your capacity for expansion. This signifies that future defence priorities no longer lie solely in “physical fortification,” but in synchronised shaping across four dimensions: Firstly, establishing a real-time joint identification system spanning intelligence, financial regulation, and public opinion clarification to detect unfolding “closed-loop attack cycles” before they gain self-amplification in capital markets; Second, drive allied/treaty frameworks to explicitly classify “systemic multi-point sabotage of critical infrastructure combined with sovereign credit arbitrage” as a sovereign-level threat rather than domestic security incidents, thereby legitimising and enabling coordinated countermeasures; Third, constructing a “credit firewall” over assets deemed anchors of national confidence (national-level energy, logistics, clearing, communications, and state-owned flagship enterprises). This employs ultra-high-speed trusted disclosure, pre-established financial backstops, and narrative boundary management to proactively suppress market overreaction coefficients (β) and the velocity of sovereign credit erosion; Fourthly, incorporate the attackers’ profit channels (i.e., financial realisation and capital repatriation) into the sovereign framework of anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing. This directly undermines their self-financing ratio, causing the closed-loop to collapse financially and reverting the operation to a “high-exposure, low-return” unprofitable venture. Only when such attacks become financially unsustainable will they revert to a manageable sphere governed by traditional deterrence logic.

Finally, this study presents an uncomfortable yet unavoidable strategic assessment: future great power competition and high-stakes confrontation will likely no longer be marked by the crossing of physical borders, but rather by the moment when a target nation is compelled to resort to wartime finance for self-preservation without the authority to declare itself at war. In other words, the starting point of conflict will no longer be the first artillery shell, but the issuance of the first high-cost emergency government bond; not the first armoured brigade crossing the border, but the first systemic enterprise losing refinancing eligibility after being flagged as a “regulatory failure risk point”; not the first wave of refugees, but the first nationwide sell-off driven by confidence collapse. For any national security apparatus still prioritising “battle sequences” and “troop movements” as primary threat indicators, this new reality signifies: you may have entered the fiscal phase of war without being permitted to declare “hostilities have commenced”. Consequently, sovereign security will increasingly equate to “credit security.” Should a political community fail to simultaneously safeguard the narrative stability of its critical infrastructure, the pricing boundaries of its capital markets, the legal authorisation channels of its alliance systems, and the sub-one SFR status of its adversaries, it risks losing the entire conflict on the balance sheet before any formal attack occurs. This is not alarmism, but structural inevitability.

8. Visual Interpretation of Decision-Making

For traditional defence audiences, hybrid warfare in the grey zone constitutes a ‘structural’ threat, yet visual intuition largely remains anchored in the framework of ‘conflict = firepower projection’: maps display arrows pointing towards enemy forces beyond the border. Therefore, if we wish to render such threats genuinely “visible” within decision-making scenarios—be it cabinet briefings, allied coordination meetings, or financial stability emergency consultations—we must translate abstract mechanisms—discrete disruption networks, credit repricing, profit loops—into instantly comprehensible operational space diagrams. In other words, graphics are not ornamentation but integral to weaponised cognition. The three visualisations proposed below are not mere diagrams but are designed for simultaneous use by national security decision-makers, financial regulators, and alliance negotiators. Their purpose is to answer three critical questions within seconds: who is attacking us, how do they profit, and how much longer can we endure?

8.1. The Dual-Layer Synergistic Model of “Physical Destruction and Financial Harvesting”: A Systemic Operational Chain from Discrete Disruptions to the Breach of National Credit

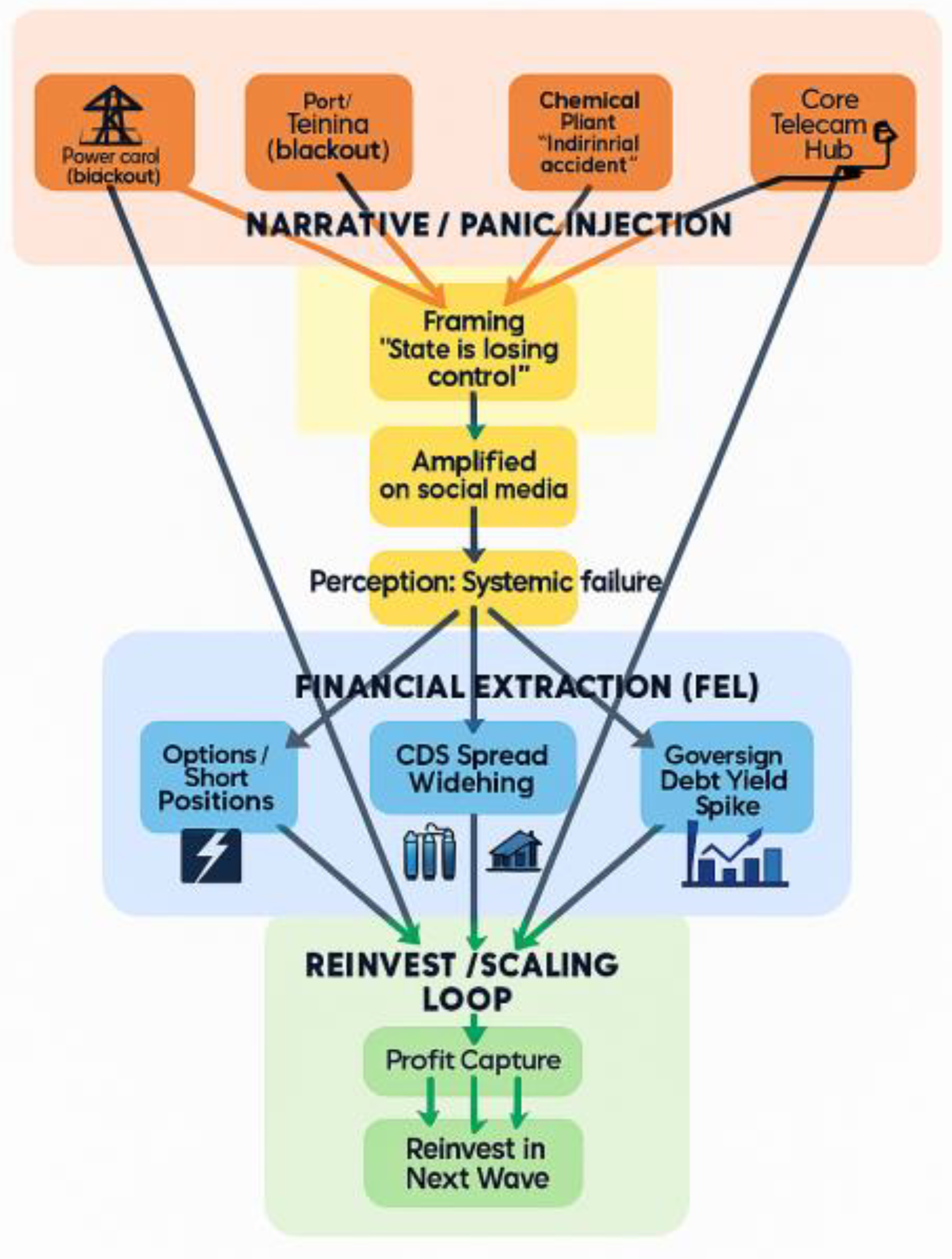

This diagram illustrates a novel “grey zone hybrid warfare” operational architecture. It is not the traditional combination of “terrorist attacks + market speculation”, but rather a self-replicating, sustainably self-funding strategic commercial model. The diagram is divided into four vertically coupled tiers, from top to bottom: the Physical Attack Layer (PDL), the Public Opinion Panic Injection Layer, the Financial Exploitation Layer (FEL), and the Reinvestment/Scaling Layer. These layers form a closed-loop operational chain through black arrows, operating as a “destruction-pricing-profit-expansion” cycle. Its core objective is to forcibly depress the target nation’s credit rating, financing capacity, and governance legitimacy without triggering conventional “thresholds for war”.

First layer: Physical attack surface

The uppermost layer in

Figure 1 is the “physical attack surface”, encompassing: - Power grids (localised blackouts, dispatch failures) - Ports/fuel terminals (fires at fuel transfer points, logistical blockages) - Chemical plants (explosions/leaks packaged as “industrial accidents”) - National communications hubs (signalled as “nationwide internet outages” or “state paralysis”) The key point is that operations here deliberately maintain “deniability” and “resemble accidents,” eschewing traditional high-intensity destruction or mass casualties in favour of “high visibility + high symbolism.” These nodes are perceived by public discourse as markers that “the state remains in control”. Should incidents occur simultaneously across multiple geographical locations within a short timeframe, the external perception would not be of “isolated incidents”, but rather that “the nation’s foundational functions are undergoing systemic collapse”.

Second Layer: Public Opinion Panic Injection Layer

The yellow module in the centre explains why this attack is not merely ‘infrastructure sabotage’. Its function is to translate localised physical events into the grand narrative that ‘the state is spiralling out of control’:

First, frame the incident: portray power outages, explosions, and port fires as “government losing control,” “regulatory collapse,” and “penetration of critical systems.” Then, disseminate this narrative simultaneously through social media, secondary media channels, and peripheral information amplifiers. Prevent it from being interpreted as an “isolated incident,” instead steering public perception—particularly among investors, rating agencies, and overseas observers—towards believing “this constitutes an organised, widespread infiltration.” The ultimate outcome is not panic itself, but the “perception of systemic failure.” This perception is the weapon. The arrows in the diagram pointing from the Physical Disruption Layer (PDL) to the Public Discourse Layer signify: every physical disturbance is re-narrated as “evidence of state governance failure.” Moreover, these incidents are not isolated occurrences but are orchestrated into a macro-narrative: “The state is going offline.”

Third Layer: Financial Harvesting Layer

The blue module constitutes the true critical vulnerability within the entire model, an area long neglected by traditional security frameworks. This layer does not represent ‘post-event damage control’ but rather pre-emptive positioning—attackers establish financial positions prior to action, including: substantial put options and short positions (betting on share price declines of key enterprises, market capitalisation-anchored firms, or industry leaders); sovereign credit default swap (CDS) positions (betting that a nation’s default risk will be repriced as high-risk); sovereign bond yield arbitrage (betting that the target nation’s government bond financing costs will be forced upwards in the short term); Sector-wide sell-off orchestration (framing “single-company incidents” as “entire industries becoming uninvestable”). The arrow points from “perceived systemic failure” to these financial instruments, signifying: markets are not pricing individual incidents, but rather “collapsed state governance” as a structural risk.

What ensues? Key enterprises in the targeted nation face rapid downgrades in capital markets, the entire sector is branded “high-risk and uninvestable”, sovereign credit spreads widen, and government bond yields surge – in essence, the nation’s financing costs, bailout expenses, and backstop expenditures skyrocket within days, thrusting its finances into quasi-wartime posture. Simultaneously, the attackers realise their gains at this very moment: they are not merely reaping “minor fluctuations in a few stocks,” but rather the substantial risk premium derived from “a nation being priced as a failed state.”

Fourth Layer: Reinvestment/Scaling Layer

The green module at the bottom indicates: this is not a one-off strike, but a closed-loop system. Profits are recycled → funds are reinvested → operations gain greater momentum, broader reach, and enhanced recruitment/infiltration/disruption capabilities → returning to the top-level physical attack surface (the arrow points back to PDL).

The significance of this circuit is of paramount importance: