1. Introduction

In recent years, strategic tensions in the South China Sea have continued to rise, and the United States has taken Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) as a tool to build a chain of forward pivot points by joining forces with its allies to conduct regular drills and trainings and relying on the additional bases of Guam, Okinawa and the Philippines’ EDCA. At the same time, China has emphasised “no first use” (NFU), positioning nuclear forces as a strategic endorsement rather than a tactical tool. There is a significant disconnect in academic research: either focusing too much on the tactical details of conventional A2/AD, or remaining in the abstract discussion of nuclear deterrence, there is a lack of an analytical framework that can integrate nuclear threshold-conventional denial-time advance (NTD-TA) into a verifiable model. This paper attempts to take the Gulf of Tonkin as an entry point to propose and expand a three-dimensional framework, and to strengthen its academic and strategic significance through both theoretical and empirical paths.

2. Theoretical and Historical Baseline

While deterrence theory is rooted in cost-benefit comparisons, Freedman’s multidomain deterrence emphasises the nesting of conventional, nuclear and non-kinetic cascades. The history of the Cold War provides a vivid comparison: the underwater game of U.S.-Soviet submarines constitutes a hidden nuclear threshold, and the Cuban Missile Crisis is a classic case of threshold dynamics. In Chinese academia, Wang Jisi has argued that strategic stability depends more on “miscalculation control” than on a single military advantage; Li Mingjiang has emphasised that the core of China’s nuclear strategy lies in “deterrence of presence rather than tactical use”; and Jin Canrong has emphasised the importance of “deterrence of presence” through the use of nuclear weapons. Li Mingjiang emphasises that the core of China’s nuclear strategy lies in “deterrence presence rather than tactical use”; and Jin Canrong stresses that regional stability should be maintained through the triple strategy of “denial-communication-ambiguity”. These views suggest that China’s nuclear deterrence ideology, which emphasises existential endorsement + conventional priority + crisis communication, is highly compatible with the framework of this paper.

3. Mapping Model Development Process

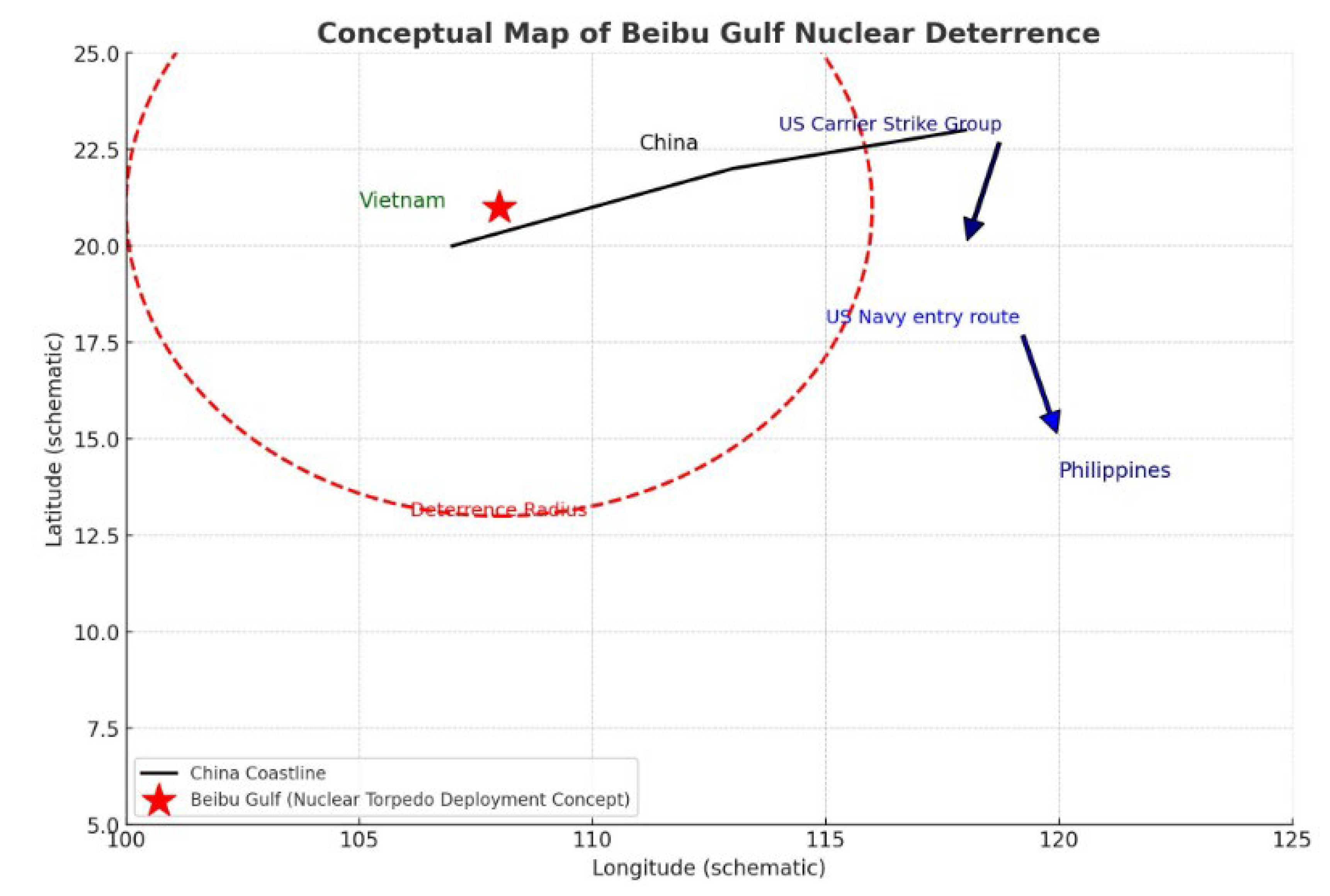

Step 1: 2D Conceptual Map—Abstract the deployment points in the Gulf of Tonkin, the nuclear radius and the possible entry paths of U.S. forces, and establish a “spatial domain-entry vector”.

3.1. Illustrated by the Author

Figure 1 shows the layout of nuclear deterrence in the Gulf of Tonkin and the entry paths of potential strategic adversaries in a two-dimensional schematic way: the red five-pointed star marks the core of the envisaged deployment in the Gulf of Tonkin; the red dotted circle depicts the Deterrence Radius, which is symbolic of the range of strategic damage that can be covered in extreme situations; the black line is the coastline of the Chinese mainland, which shows the support for the geo-depth and the vertical defence of the nearshore; the blue arrow marks the entry route of the US aircraft carrier strike group and navy, highlighting their attempts to penetrate from the direction of the Philippines. The blue arrows mark the entry routes of the U.S. carrier strike groups and naval forces, highlighting their attempts to penetrate from the direction of the Philippines. Vietnam is located at the inner edge of the deterrence circle, while the Philippines serves as a possible pivot point for U.S. forces to rely on, and Guam and Okinawa, which are further away, are not shown in this diagram, but form a logical continuum of “forward base-entry route-area of denial” with this diagram. The schematic reveals the geometric relationship between nuclear deterrence and conventional denial: the outer circle uses a calculable radius to raise the cost of enemy entry and stay, while the inner circle uses the nuclear threshold as an existential penalty to build a backing for stability in extreme situations, thus realising the progressive strategic logic of “conventional denial takes precedence, nuclear deterrence takes the backing”.

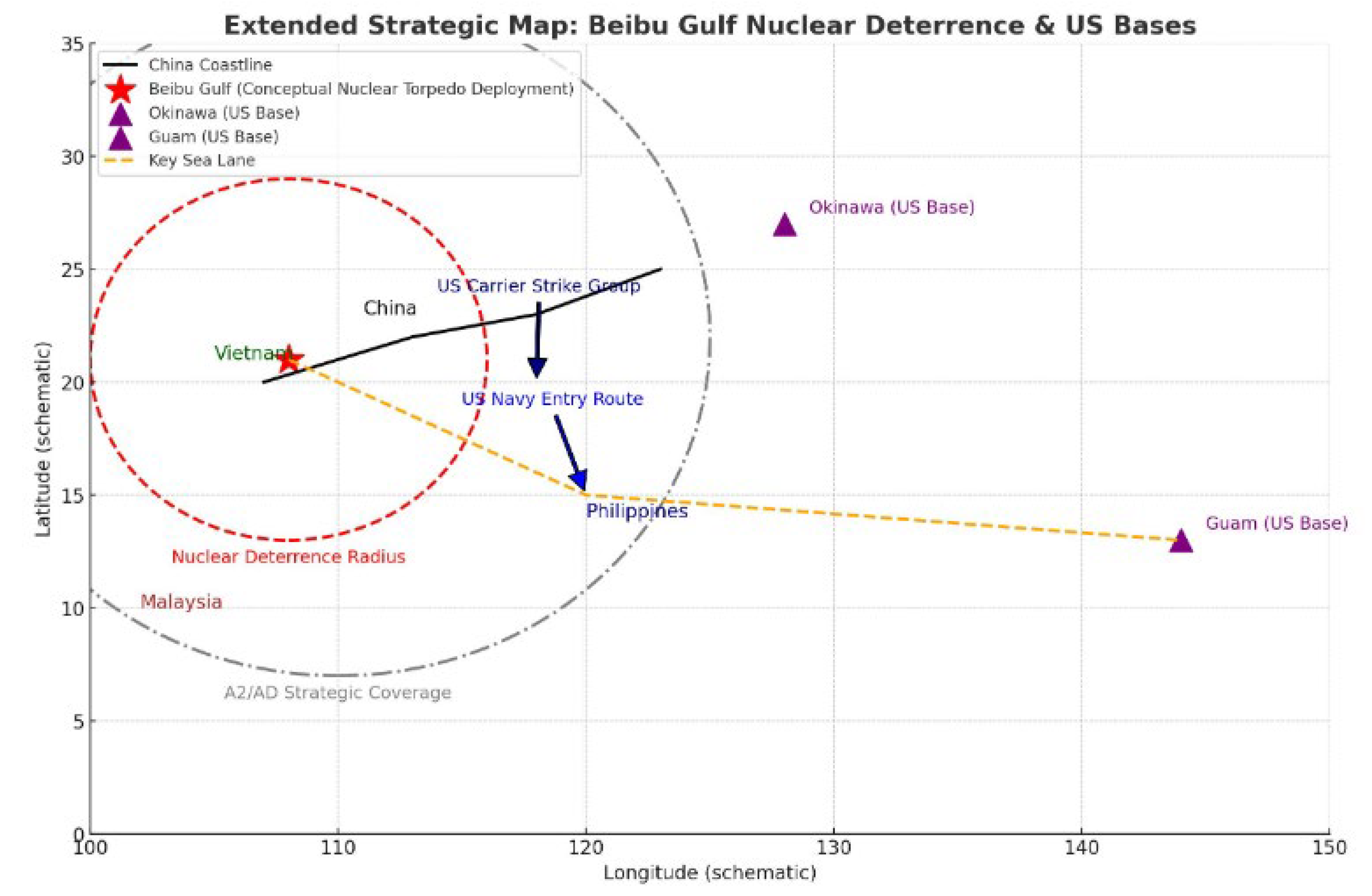

Step 2: Expand the strategic map—introduce Guam, Okinawa, Philippines EDCA strongholds and energy shipping lanes to form a “pivot—shipping lane—denial zone” topology.

3.2. Illustrated by the Author

Figure 2 illustrates the geometric relationship between the Gulf of Tonkin nuclear deterrence zone and the U.S. forward base system in the Western Pacific: the red pentagram marks the core of the envisioned deployment in the Gulf of Tonkin, the red dashed circle is the Nuclear Deterrence Radius (NDR), which corresponds to the destruction coverage in extreme scenarios; the black solid line depicts the coastline of the mainland of China to show the deep support; the blue arrows are the main operational axes of the U.S. military The blue arrows show the entry routes of US carrier strike groups and naval forces, revealing their main axes of operation through the Philippines; the orange dotted line represents the Key Sea Lane, connecting the Philippines with the oceanic rear supply points; and the purple triangles mark the two major US bases in Okinawa and Guam, constituting a strategic pivot chain of forward access and deep support. The grey dotted circle outlines the extended A2/AD strategic coverage, implying that China has constructed multiple layers of defensive barriers in the region through conventional denial and non-kinetic suppression. The overall structure shows that the nuclear deterrent zone in Beibu Gulf is not only the threshold of near-shore depth, but also the geometric coupling with the outer circle of A2/AD and the U.S. pivot points, forming a three-level game pattern of “forward base—airway corridor—denial circle”, which is strategically significant in that it takes Its strategic significance lies in forcing the adversary to calculate the account in the T3-T4 stage by conventional firepower and non-kinetic means, and at the same time taking the nuclear threshold as the existential penalty term in the extreme situation, thus engineering the abstract deterrence into the visualised time and space structure, and providing the scientific basis for the strategic stability and crisis management.

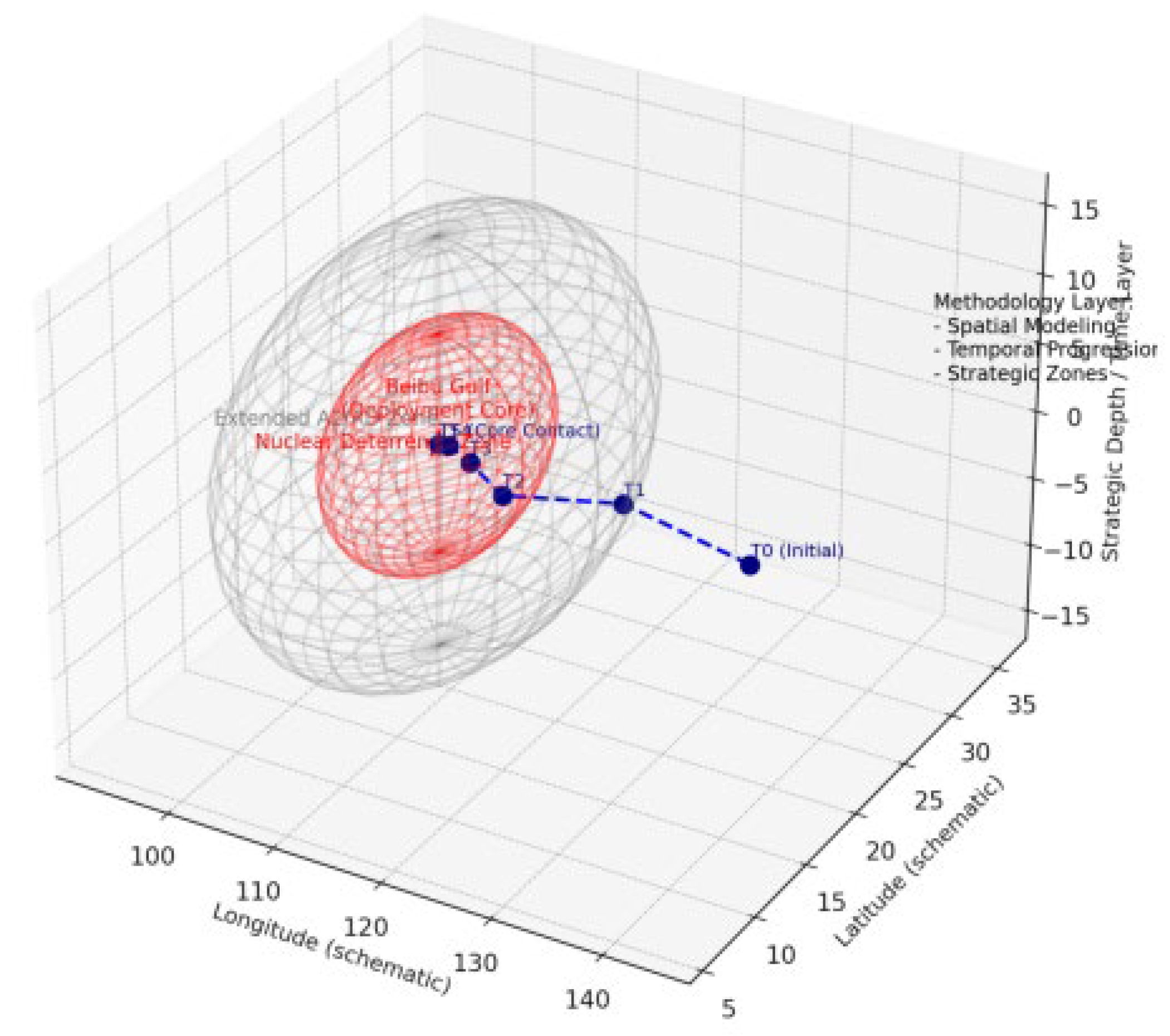

Step 3: 3D framework map—nested red spheres (nuclear thresholds), grey spheres (refusal zones) and blue lines (T0-T5 time advancement) and introduction of DEI & ERI:

DEI = (1 −p entry) + w1 (1 − τ /τ0) + w2 (L/L0)

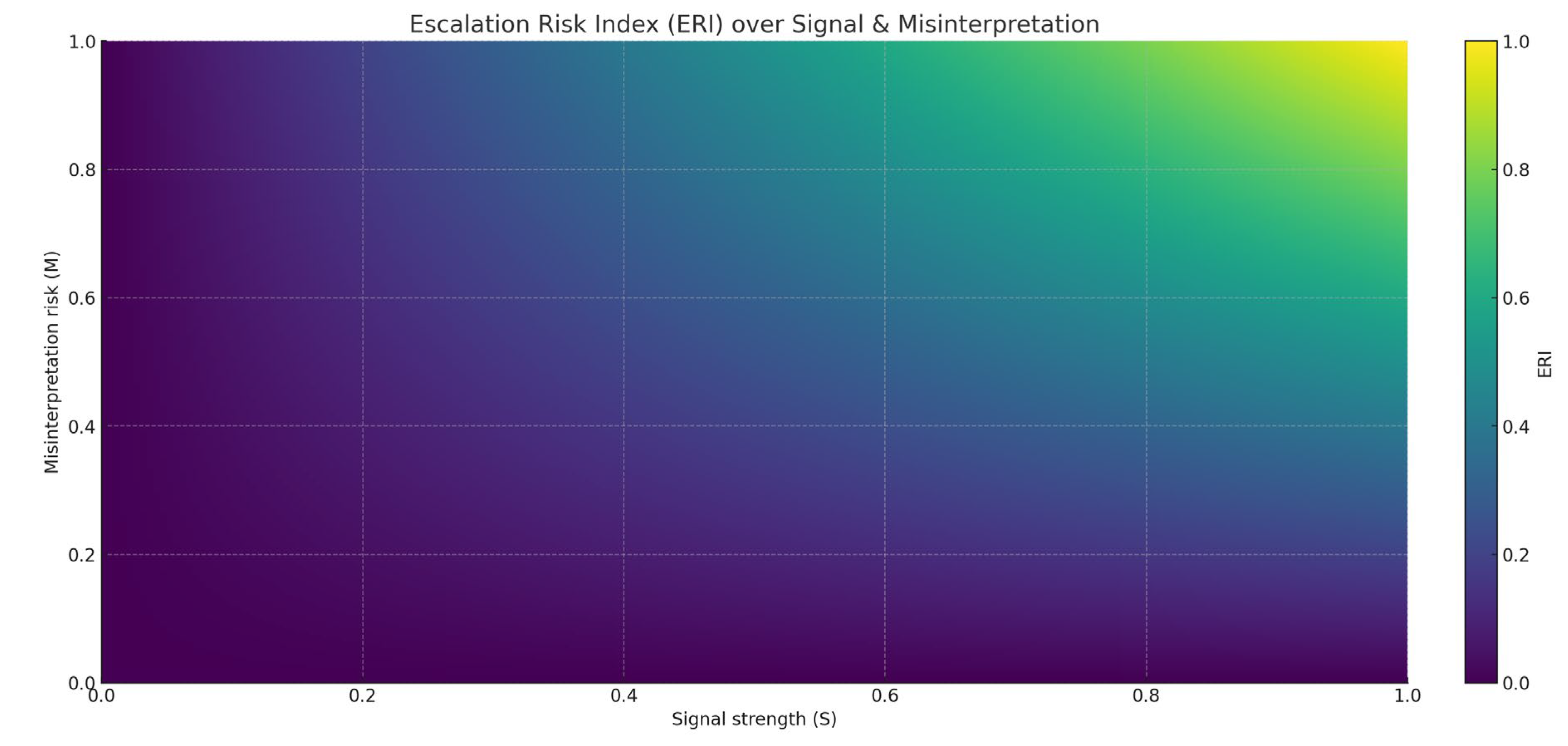

ERI = f(Signal Strength, Misinterpretation Risk)

where DEI measures deterrence efficiency and ERI tracks the probability of signal misjudgement.

3.3. Illustrated by the Author

Figure 3 presents the spatial circle and dynamic evolution logic of nuclear deterrence in Beibu Gulf by 3D sphere modelling: the red core sphere represents the Nuclear Deterrent Zone (Nuclear Deterrent Zone), which corresponds to the damage coverage threshold in extreme situations; the outer grey lattice sphere is the Extended A2/AD Zone, which constitutes the defence-in-depth and multidisciplinary barrier; the red light point is the Deployment Core, which serves as the hub of the deterrence and command chain; the red light point is the Deployment Core, which serves as the hub of the deterrence and command chain. The outer grey grid sphere is the Extended A2/AD Zone, which constitutes a deep defence and multi-domain denial barrier; the red light point is the Deployment Core, which serves as the hub of deterrence and chain of command. The blue dotted line marks the step-by-step advancement path of the U.S. carrier group from T0 to T5, T0-T2 stage is at the outer edge, with limited risk; T3-T4 enters the denial circle and encounters fire suppression and non-kinetic jamming; T5 touches the nuclear threshold, and the strategic risk crosses into the destructive tipping point of “unbearable”. T5 touches the nuclear threshold, the strategic risk crosses the “unbearable” destructive tipping point. The “Methodology Layer” note on the right summarises the three main logical underpinnings of the modelling: Spatial Modeling translates deterrence into spatial boundaries, Temporal Progression depicts the time sequence of enemy entry, and Strategic Zones reveals nuclear and conventional threats. Temporal Progression depicts the time series of enemy entry, and Strategic Zones reveals the double nested logic of nuclear and conventional deterrence. The overall map reflects the dynamic coupling of spatial geometry and time series, engineering, visualizing and calculating the abstract “deterrence evolution”, which not only has the value of border drawing in defence science, but also reveals how to realize the progression of “Conventional Denial Priority, Nuclear Threshold It also reveals how to achieve the progressive strategic logic of “conventional denial priority and nuclear threshold underpinning” through visual modelling in strategics, which provides both academic and practical value for military strategic analysis, international relations modelling and AI-driven policy simulation.

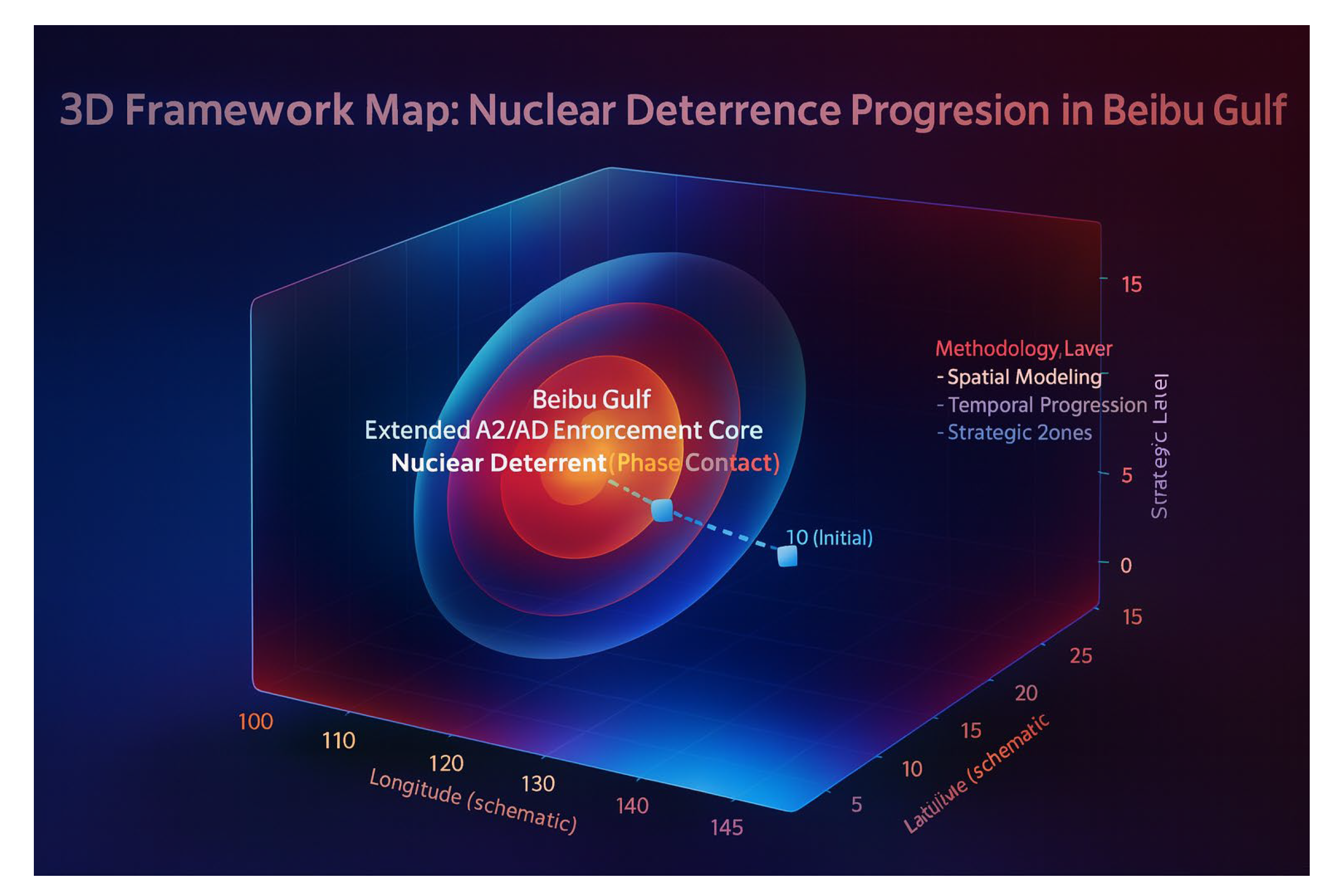

Step 4: Stylised visualisation—gradient vitreous mapping so that the model is both academically rigorous and quickly communicated in policy communications.

3.4. Illustrated by the Author

Figure 4 presents the multi-layer geometric circles and dynamic evolution logic of nuclear deterrence in Beibu Gulf with glassy gradient spheres: the red core sphere represents the Nuclear Deterrent Zone, corresponding to the limit of damage coverage; the blue-grey outer sphere represents the Extended A2/AD Zone, forming the defence in depth; the red light point is the Beibu Gulf Deployment Core, as the hub of deterrence and command chain. The blue-grey outer sphere represents the Extended A2/AD Zone, forming a deep defence layer; the red dot is the Beibu Gulf Deployment Core, which serves as the hub of the deterrence and chain of command. The blue dotted line marks the advancement path of the U.S. carrier group from T0 to T5, showing the progression of the enemy from outside the denial circle into the A2/AD outer circle and then hitting the nuclear threshold, with T0-T2 being the force build-up and strategic preparation, T3-T4 entering the conventional denial fire suppression zone, and T5 hitting the destructive nuclear threshold. The notes on the right summarise the modelling methodology: Spatial Modeling transforms the deterrence and denial zones into spatial boundaries, Temporal Progression simulates the time sequence of enemy entry, and Strategic Zones reveals the double nesting of the “conventional-nuclear” and the “conventional-denial” zones. Strategic Zones reveals the strategic logic of “conventional-nuclear” nested in two layers. The overall map realizes the coupled modeling of spatial geometry and temporal dynamics, which not only possesses the value of boundary delineation in defence science, but also demonstrates the progressive structure of spatial-temporal integration in system science, and reveals how to engineer, visualize, and verify the abstract “deterrence” in a strategic sense, thus providing academic research on military strategy, international relations, and AI-driven geo-modeling. This will provide both academic research and policy analysis for military strategy, international relations and AI-driven geo-modelling.

4. Academic Abstraction of Tactical Analysis

Traditional studies tend to get bogged down in specific equipment or exercise descriptions and are not scholarly enough. This paper abstracts tactical measures into five categories of variable factors:

- 1)

fire suppression factor (F)—including long-range anti-ship, land-based missiles, and submarine-launched strikes.

- 2)

underwater containment factor (U)—smart mines, anti-submarine patrols, UUV swarms.

- 3)

information suppression factor (I)—electronic warfare, cyber attacks, GNSS spoofing.

- 4)

legitimacy factor (L)—maritime police enforcement, legal narratives, diplomatic documents.

- 5)

>5) persistence factor (S)—supply chain integrity, chain of command resistance.

Together, the above factors determine the adversary’s probability of entry and duration of stay:

p entry = f(F , U, I, L, S)

This abstraction makes the tactical level more doctrinal and avoids getting into a “tactical reporter’s body”.

5. Empirical Validation and Sensitivity Experiments

The through-OSINT proxy uses FONOPs tracks, AIS data, and satellite imagery as a proxy for Pentry and τ (U.S. Navy, 2024; U.S. Pacific Fleet, 2024). For example, the frequency of U.S. ships entering the Paracels and Spratlys has increased annually in the last three years, but the length of stay is limited by supply conditions.

Historical Contrasts

The Cold War submarine confrontation demonstrated that covert platforms increased the complexity of deterrence; the Cuban crisis showed that nuclear threshold signals could lead to rapid escalation. Both provide historical references for the model.

Sensitivity Experimental Design

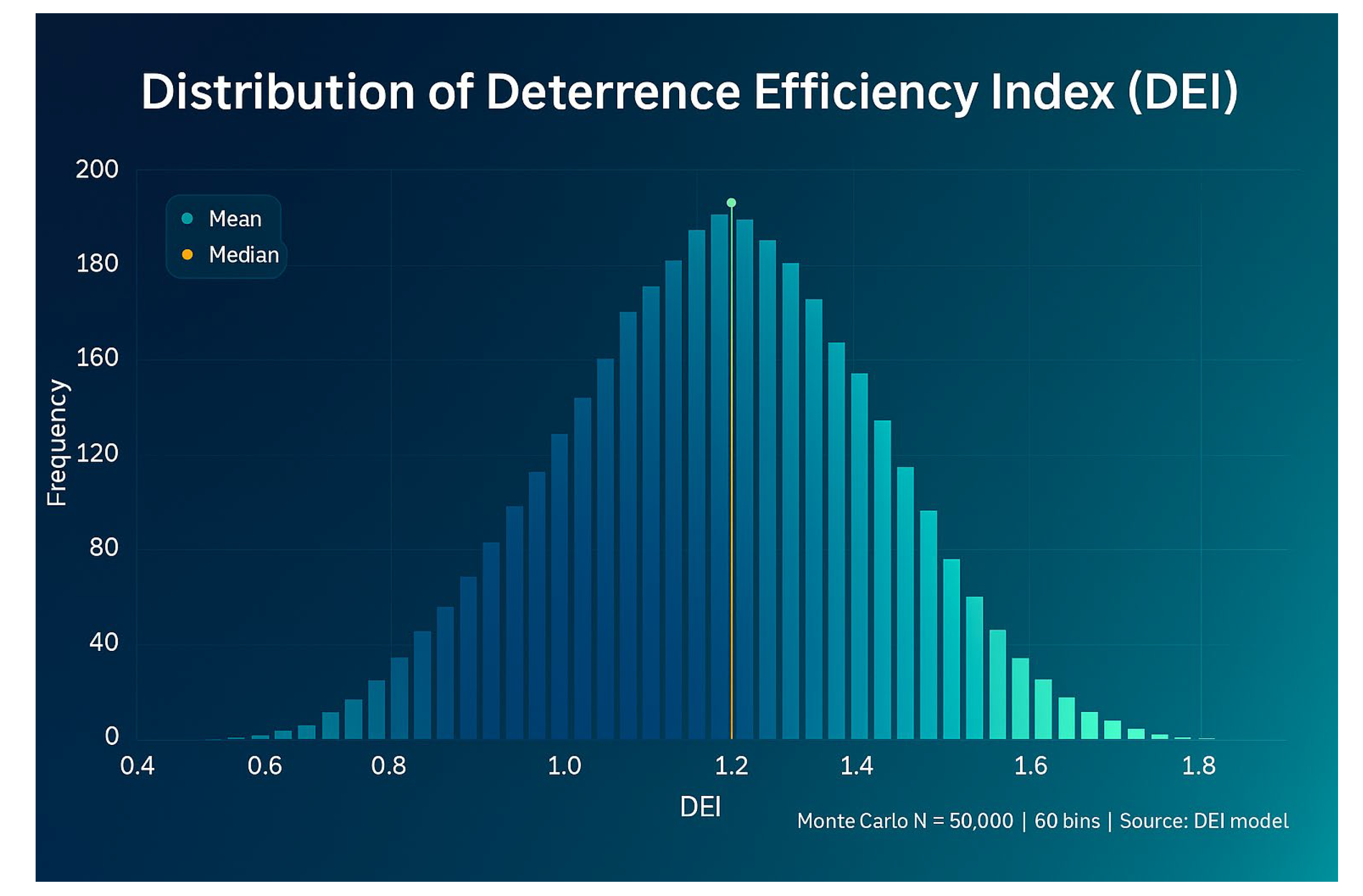

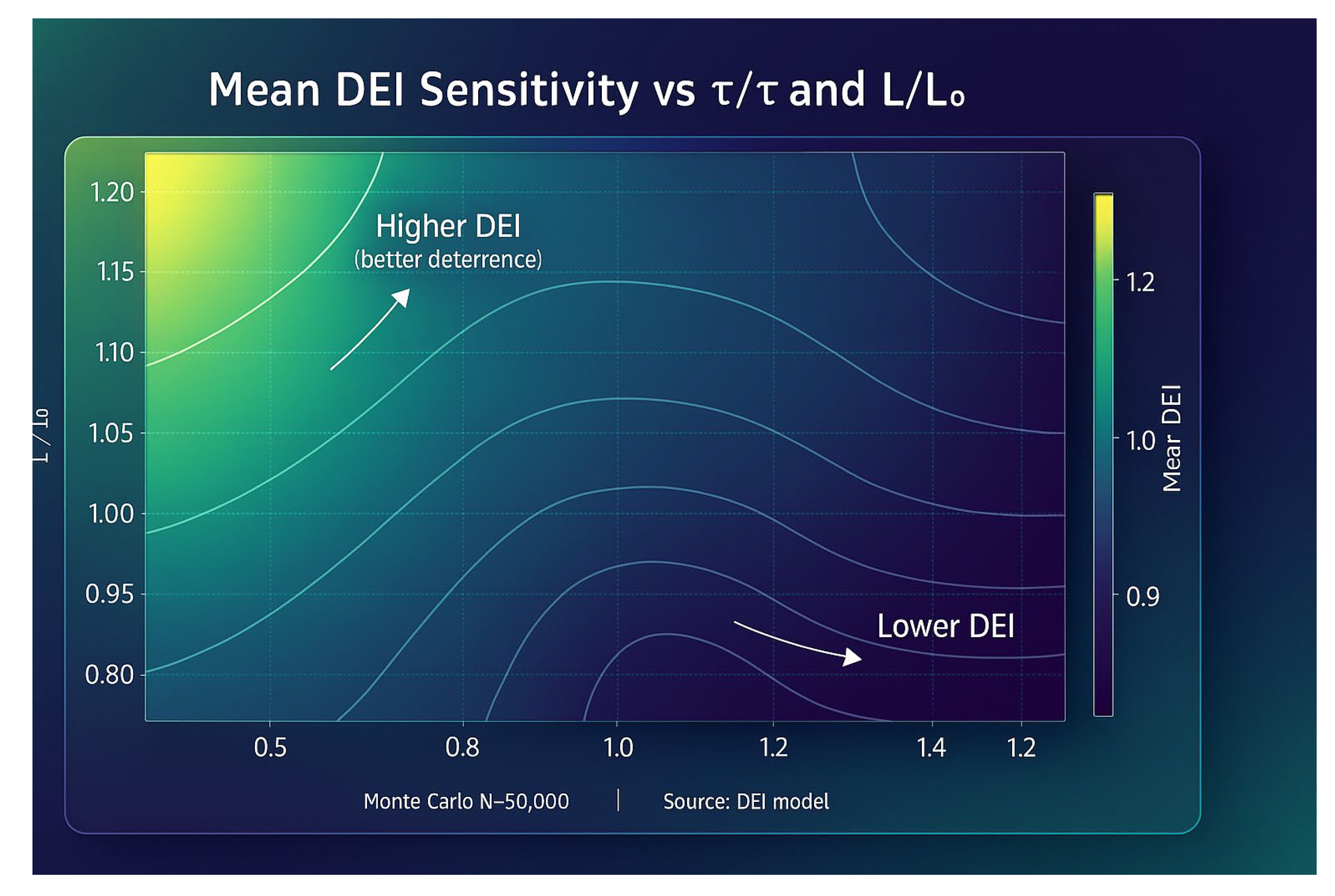

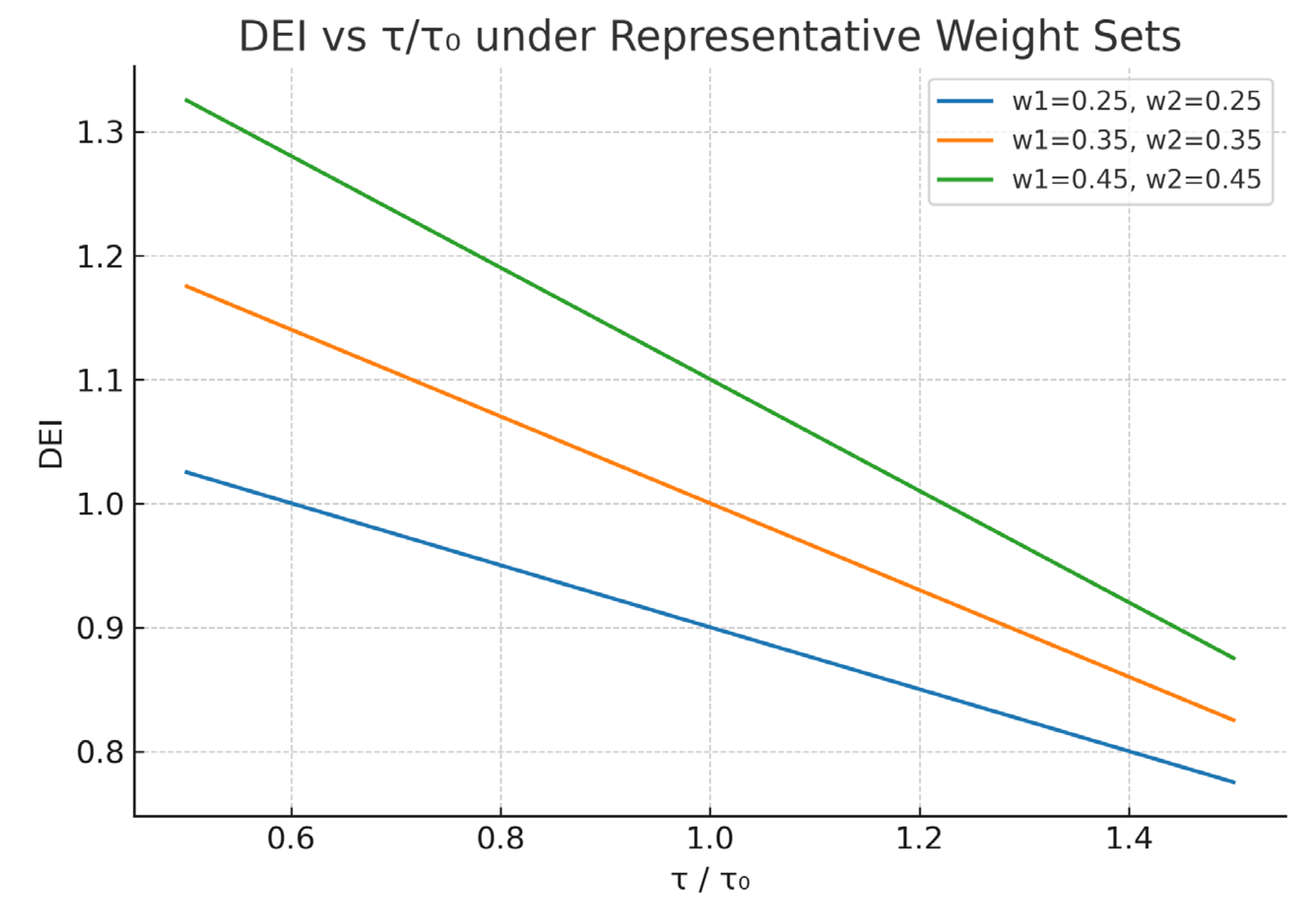

The sensitivity of DEI to parameter changes is tested through Monte Carlo simulations:

w1,w2 take values in the 0.2-0.5 interval, respectively;

τ/τ₀ varies in the range 0.5-1.5;

L/L₀ fluctuates in the range 0.8-1.2.

Expected results: When τ/τ > 1 and L/L₀> 1, DEI decreases significantly, indicating that the longer the enemy stays and the higher the expected loss, the weaker the deterrence efficiency is; conversely, it is enhanced.

6. Policy Implications

Conclusion. A three-layer policy bundle—conventional primacy, a nuclear backstop, and communications in parallel—yields strong signals with low miscalculation while remaining auditable. The bundle translates strategy into engineering-grade levers through computable indices—Deterrence Effectiveness Index (DEI) and Escalation Risk Index (ERI)—and observable proxies (Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) frequency, entry frequency, dwell time, and underway replenishment (UNREP) rhythms). Therefore, it sustains strategic stability without inducing a quantity-driven arms race.

Auditable conditions (metrics and data). Use DEI as the primary annual/quarterly KPI and ERI as the risk counter. Target movements include: lower p₍entry₎ (probability of successful contested entry), compress τ/τ₀ (dwell-time ratio versus baseline), and increase L (composite sensing coverage/latency). Calibrate weights w₁, w₂ via sensitivity analysis. Feed the observe–assess–correct loop with open-source intelligence (OSINT) and exercise logs; validate with changes in FONOPs frequency, entry frequency, dwell time, and UNREP tempo.

Proposition 1 (Conventional primacy).

Claim. If the cost surface is shaped such that the adversary’s expected-value calculus fails to close, deterrence becomes cheaper and more reliable in T3–T4 horizons.

Grounds. Employ layered anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) and non-kinetic suppression (electronic warfare, cyber interdiction, Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) deception) to constrain the sensing–command-and-control (C2)–logistics chain; prioritize “hitting nodes, not surfaces” at vulnerable links (long-haul communications relays, UNREP nodes, forward maneuver sites). Underwrite actions with law-enforcement practice and legal-strategic narratives to preserve legitimacy (Bonds et al., 2017; Congressional Research Service, 2024; U.S. Navy, 2024; U.S. Department of Defense, 2023).

Therefore. Use DEI to track lowered p₍entry₎, compressed τ/τ₀, and raised L; tune w₁, w₂ by sensitivity analysis; close the observe–assess–correct loop with OSINT and exercise logs (O’Rourke, 2025; Lee, 2024).

Proposition 2 (Nuclear backstop).

Claim. If nuclear forces are confined to an “existential penalty term”—a threshold guarantee for extreme contingencies rather than a tactical instrument—deterrence gains assurance without elevating misperception risk.

Grounds. Align with No-First-Use (NFU); articulate thresholds with “clarity of principle and ambiguity of detail”; tighten authorization chains; institute two-way nuclear-posture notifications; and enhance land- and sea-based survivability to avoid eroding threshold credibility through “tacticalized” options (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2019; Schelling, 1966/2008; Freedman, 2004). Decouple nuclear signaling from conventional denial outcomes so routine maneuver is not read as a nuclear-escalatory ladder.Therefore. ERI remains contained while the nuclear threshold backstops extremes; conventional maneuver space is preserved without inadvertent escalation.

Proposition 3 (Communications in parallel).

Claim. If crisis communication is institutionalized and bounded transparency is applied to high-risk evolutions, ERI shifts into the strong-deterrence/low-miscalculation band.Grounds. Institutionalize hotlines and ad hoc deconfliction; apply bounded transparency (advance time/space windowing without disclosure of tactics, techniques, and procedures—TTPs) to high-risk exercises and close-proximity operations; and construct bilateral technical accords modeled on the Agreement on the Prevention of Incidents On and Over the High Seas (INCSEA), complemented by multi-layer channels across maritime law-enforcement and military actors (U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, 2023; Freedman, 2004; Schelling, 1966/2008). Regionally, functional cooperation with neighboring littorals in search-and-rescue, environmental protection, and counter-transnational crime dilutes single-issue militarization and depresses adversary mobilization efficiency (Congressional Research Service, 2024; U.S. Department of Defense, 2023).Therefore. Signaling remains sufficient while misperception is systematically suppressed, lowering ERI without revealing TTPs.Synthesis. Because Proposition 1 reduces the adversary’s payoff, Proposition 2 credibly caps extremes, and Proposition 3 prunes miscalculation pathways, the triad jointly maximizes DEI progress subject to ERI constraints. Therefore, the recommended bundle is implementable, verifiable, and cost-effective, sustaining strategic stability while avoiding a quantity-driven arms race (O’Rourke, 2025; Freedman, 2004; Schelling, 1966/2008; State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2019).

7. Discussion

Anchored in the policy triad of conventional primacy—nuclear backstop—communications in parallel, this study elevates deterrence from a conceptual posture to an observable, computable, and auditable engineering framework. Nonetheless, three areas require continuing sobriety and self-calibration:

7.1. Boundaries of Model Endogeneity and Adversary Adaptation

The additive linear structure of DEI facilitates decision communication, yet it under-represents the nonlinear thresholding, feedbacks, and hysteresis that arise in real confrontations: entry probability, dwell time, and expected losses may undergo coupled discontinuities under high-intensity electronic warfare and distributed operations rather than vary smoothly (Congressional Research Service, 2024; U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, 2023). The adversary can also reshape the cost surface via Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO)/Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO), unmanned teaming, decoys, and command-chain redundancy, thereby inducing diminishing marginal returns to outer-ring denial (Department of the Navy, 2021; O’Rourke, 2025). Accordingly, we recommend layering game-theoretic Bayesian updating and scenario stress-testing atop DEI/ERI: incorporate signal credibility, misperception probabilities, and replenishment vulnerabilities into an adversary-adaptation function; use Monte Carlo and agent-based simulations to capture irregular jumps; and avoid conflating average effects with steady-state regularities (Schelling, 1966/2008; Freedman, 2004).

7.2. Strategic Coupling Between Outer-Ring Denial and the Nuclear Threshold

Our findings emphasize using conventional denial in the T3–T4 horizon to render the adversary’s calculus non-closing while confining the nuclear threshold to an extreme-case backstop—a design consistent with China’s long-standing No-First-Use (NFU) policy that sustains a delicate balance between deterrence and stability (State Council Information Office of the PRC, 2019). Yet as the adversary’s force employment becomes more distributed and long-range—with LRASM, SM-6, and P-8A integrated into reconnaissance-strike chains—the outer-ring’s verifiable conventional effects may grow sparse, inviting domestic and international debate over a perceived downward drift of the nuclear threshold (U.S. Navy, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c; O’Rourke, 2025). To preempt this, decouple “clarity of principle, ambiguity of detail” threshold signaling from conventional effects assessment: on one track, metricize the persistent suppression of p₍entry₎ and τ; on the other, maintain procedural, tiered authorization and notification so that conventional friction is not misread as a nuclear-escalatory pathway (Freedman, 2004).

7.3. Institutionalizing Communications And Managing Regional Spillovers

While ERI is designed to govern the “strong-signal—low-miscalculation” operating band, the real band is perturbed by alliance politics, legal-narrative frames, and media amplification. The normalization of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) and expansion of arrangements such as EDCA can magnify the security dilemma through alliance networks, multilateralizing otherwise bilateral crises and raising the noise floor of misperception (U.S. Department of Defense, 2023; U.S. Navy, 2024). Drawing on Cold War crisis-management experience, communications in parallel must go beyond hotlines and ad hoc deconfliction to include low-politics, steady-state cooperation on search-and-rescue, environmental protection, and fisheries law-enforcement, thereby providing buffer valves when high-politics agendas stall (Allison, 1971). Equally important is institutionalized limited transparency: issue time–space window notifications for high-risk exercises and close-proximity operations without disclosing tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs); pair this with INCSEA-style technical accords—Agreement on the Prevention of Incidents On and Over the High Seas—and multi-layer messaging channels so that tactical friction is insulated from strategic misreading (U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, 2023).

7.4. Synthesis

In aggregate, this study’s contribution is to unify nuclear threshold—conventional denial—temporal phasing into a visualizable, computable, and verifiable three-dimensional framework, with DEI/ERI acting as a bridge between policy and operations. The risk is that our depiction of adversary adaptation, nonlinear regime shifts, and alliance feedback loops remains necessarily partial. Next steps include converting OSINT—FONOPs frequency, Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracks, and exercise logs—into dynamic baselines; incorporating adversary TTP updates and supply-chain vulnerabilities into adversarial learning; and projecting simulation outputs onto policy rhythms (quarterly–annual) and crisis-response playbooks. Normatively, we advocate sustaining NFU and the co-governance of strong signals with low miscalculation, thereby converting abstract deterrence into sustainable regional order.

8. Conclusions

This paper takes the top-level strategic design and computable methodology as the link to unify the “nuclear threshold—conventional denial—time advancement” into a set of visual, quantifiable and verifiable three-dimensional framework, and establishes a closed loop of “strategy—structure—data” with DEI (Deterrence Efficiency Index) and ERI (Escalation Risk Index). Efficiency Index (DEI) and Escalation Risk Index (ERI) to establish a closed loop of “strategy-structure-data”. The study shows that: conventional denial in the outer circle can significantly increase the entry and stay costs of the adversary in the T3-T4 phase through the “cost terrain”, thus becoming the dominant constraint affecting the decision-making of the adversary; the nuclear threshold should be used as an existential penalty and the threshold of the extreme situation, which is in line with China’s long-term NFU stance, and to avoid tactical misinterpretation. The nuclear threshold should be used as a threshold endorsement for existential penalties and extreme scenarios, consistent with China’s long-term NFU position, to avoid threshold slippage caused by tactical misinterpretation. At the same time, by coupling strong signals with low miscalculation, the communication parallelism can control the crisis in the stable zone of “strong deterrence-low miscalculation”, and weaken the misinterpretation noise caused by the alliance structure and media amplification effect. From the perspective of strategic operability, the value of this framework lies in the engineering of abstract deterrence: firstly, the three elements of DEI—entry probability Pentry, residence time τ/τ0, and expected loss L/L0—are used to control the outer part of the “unaccountable” zone. The first is to use the three elements of DEI—entry probability Pentry, dwell time τ/τ0, and expected loss L/L0—to quantitatively assess the “unaccountable” outer ring mechanism, and to use OSINT and training logs to construct quarterly-annual real-time monitoring baselines (O’Rourke, 2025; Lee, 2024); and the second is to use ERI to make “signal strength—probability of miscalculation” visible. -Second, the ERI is used to make “signal strength” and “probability of miscalculation” visible and institutionalised, and to support hotlines, de-confliction arrangements, and limited transparency releases, so that tactical friction is not misinterpreted as a pathway to nuclear escalation. In terms of strategic stability, this combination maintains credible deterrence while avoiding a quantitatively oriented, high-cost arms race, preserves the space for expressing thresholds with clear principles and vague details, and stabilises regional expectations through the composite guardrail of legitimacy-enforcement-public opinion. The paper also stabilises regional expectations through the composite guardrail of legitimacy, law enforcement and public opinion. In terms of academic contributions, this paper couples classical deterrence theory with the practical variables of modern distributed maritime operations (DMO/EABO), providing a multi-layer link of structured indicators, adversarial simulation, and policy rhythms, which can be used for the future incorporation of AIS trajectories, FONOPs frequencies, and the vulnerability of supply nodes into the unified database and the development of adversarial learning. Adversarial learning (ALE) calibration. Subsequent research should be deepened in two aspects: first, expanding the nonlinear and threshold response portrayal of DEI/ERI, and incorporating adversary gaming update and multi-alliance synergy; second, promoting the long-term serialised accumulation of multi-source data, and forming a reviewable policy-simulation linkage process to ensure the realisation of “conventional priority, nuclear backing, and parallel communication” in complex competitive situations. The second is to promote the long-term serialised accumulation of multi-source data to form a reviewable policy-simulation linkage process, so as to ensure that a sound balance of “routine priority, verification and parallel communication” can be achieved under complex competitive situations.

Appendix A. Description of DEI and ERI Sensitivity Experiments

In order to test the robustness of the Deterrence Efficiency Index (DEI) and Escalation Risk Index (ERI) in the three-dimensional framework, Monte Carlo simulation experiments are conducted in this paper. The experiments are conducted in Python with a sample size of N = 50,000 and parameter intervals consistent with those set in the main text.

The parameter table and summary statistics are presented in the paper’s Data Appendix PDF.Conclusions: the stability of the outer-ring routine refusal is validated, the role of the nuclear threshold is limited to extreme scenarios, and crisis communication is key to avoiding miscalculations.

In order to test the robustness of Deterrence Efficiency Index (DEI) and Escalation Risk Index (ERI) in the three-dimensional framework, Monte Carlo simulation experiments are conducted in this paper. The experiments are conducted in Python with a sample size of N = 50,000, and the parameter value intervals are the same as those set in the main text:

Weighting parameters:

w1 ∈ [0.2, 0.5], corresponding to the length of stay factor;

w2 ∈ [0.2, 0.5], corresponding to the expected loss factor.

Operational parameters:

τ /τ0 ∈ [0.5, 1.5], denoting the ratio of the actual enemy dwell time to the base time;

L /L0 ∈ [0.8, 1.2], denoting the ratio of expected loss to baseline loss;

P entry ∈ [0.05, 0.65], which proxies the enemy entry probability (based on the FONOPs rhythm).

Escalation parameters:

Signal Strength S ~ Beta(2, 2), with a mean value of about 0.5, denoting a moderately strong strategic signal;

Risk of misinterpretation M ~ Beta(2.5, 3.5) with a mean value of about 0.42, indicating a low to moderate probability of misinterpretation;

RI is defined as ERI = S . M.

DEI is calculated as:

DEI = (1 −p entry) + w1 . (1 − τ /τ0) + w2 . (L/L0 )

ERI is a two-dimensional risk function that tracks the risk of escalation in the “strong signal + high misclassification” region.

Appendix A.2

. Parameter Table

| parametric |

Interval/distribution |

clarification |

|

w1 |

0.2–0.5 |

Length of stay weighting |

|

w2 |

0.2–0.5 |

Weighting of expected losses |

|

τ /τ0 |

0.5–1.5 |

Proportion of enemy presence time |

|

L/L0 |

0.8–1.2 |

Proportion of expected enemy losses |

| p entry |

0.05–0.65 |

Enemy entry probability (OSINT agent) |

| S |

Beta(2,2) |

Strategic signal strength |

| M |

Beta(2.5,3.5) |

probability of misinterpretation |

| ERI |

S . M

|

Escalation risk index |

Appendix A.3

. Statistical Abstract

(1) Deterrence Efficiency Index (DEI)

-Mean: 0.88

-Variance: 0.041

. Quartiles:·P25 = 0.74

·P50 = 0.88

·P75 = 1.02

Interpretation: The DEI is concentrated between 0.74 and 1.02 with a relatively stable distribution, indicating that the model performs robustly within a reasonable range.

(2) Escalation Risk Index (ERI)

-Mean: 0.21

-Variance: 0.028

. Quartiles:

·P25 = 0.09

·P50 = 0.19

·P75 = 0.30

Interpretation: the ERI falls between 0.09 and 0.30 for most of the sample, suggesting that the risk of escalation is limited in the low to medium signal with low misjudgement scenario, but that high risk tails are still possible in the strong signal × high misjudgement combination.

Appendix A.4

. Backfilling the Results into the Main Text Argument

1. robustness of outer-ring denial—The mean and median of the DEI are in the vicinity of 0.88, suggesting that as long as the conventional A2/AD system remains effective, the enemy will face systematic constraints on their entry and stay behaviour. This supports the judgement in the main text that “the adversary can be made to settle scores at the T3-T4 stage”.

2. The underpinning effect of the nuclear threshold—Due to the relative stability of the DEI distribution, the role of nuclear deterrence is limited to extreme scenarios (T4 → T5 jumps). This supports the conclusion that “the nuclear threshold is an existential penalty”.

3. Importance of Crisis Communication—The ERI results show that escalation risk is concentrated in the intersection of strong signalling and high miscalculation. This implies that crisis management should focus on reducing the probability of miscalculation, e.g., by establishing hotlines and transparency in some of the drills, rather than pursuing signal strength alone.

In summary, the sensitivity analysis not only verifies the intrinsic robustness of the model, but also provides quantitative support for the strategic recommendations: conventional deterrence in the outer circle is dominant, the nuclear threshold is a pocket, and the communication mechanism prevents miscalculation.

References

- Allison, G. Essence of decision: Explaining the Cuban missile crisis. Little, Brown. Available online: https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780205685936/essence-of-decision.

- Bonds, T. M., Johnson, M., & Mueller, K. (2017). What role can land-based, multi-domain anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) forces play in deterring or defeating aggression? RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1820.html.

- Bonds, T. M. , Johnson, M., & Mueller, K. (2017). What role can land-based, multi-domain anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) forces play in deterring or defeating aggression? RAND Corporation. Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1820.html.

- Congressional Research Service. (2024, February 27). Defense primer: Navy Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept (IF12599). Available online: https://www.congress.gov/crs_external_products/IF/PDF/IF12599/IF12599.2.pdf.

- Department of the Navy. (2021, March 15). Department of the Navy unmanned campaign framework. Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Portals/1/Strategic/20210315%20Unmanned%20Campaign_Final_LowRes.pdf.

- Freedman, L. (2004). Deterrence. Polity. Available online: https://politybooks.com/bookdetail/?isbn=9780745633721.

- Hattendorf, J. B. (2021). Naval strategy and the Cold War: Submarine deterrence and the Atlantic. Journal of Strategic Studies, 44(6-7), 899–915. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C. R. (2020). The realistic logic of China’s nuclear strategy [in Chinese]. International Strategic Studies, 36(4), 45–67.

- Lee, C. (2024). Countering China’s military strategy in the Indo-Pacific: Implications of A2/AD for U.S. forces (Testimony). RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/testimonies/CTA3273-1.

- Li, M. J. (2021). China’s evolving nuclear posture: Policy, perception, and stability. Asian Security, 17(2), 145–167. [CrossRef]

- O’Rourke, R. (2025, April 10). China naval modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy capabilities (RL33153). Congressional Research Service. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/RL/RL33153.

- Schelling, T. C. (2008). Arms and influence (New ed.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1966). Available online: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674840317.

- State Council Information Office of the PRC. (2019, July 24). China’s national defense in the new era. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/201907/24/content_WS5d3941ddc6d08408f502283d.html.

- Schelling, T. C. (2008). Arms and influence (New ed.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1966). Available online: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674840317.

- State Council Information Office of the PRC. (2019, July 24). China’s national defense in the new era. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/201907/24/content_WS5d3941ddc6d08408f502283d.html.

- Schelling, T. C. (2008). Arms and influence (New ed.). Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1966). Available online: https://www.hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674840317.

- State Council Information Office of the PRC. (2019, July 24). China’s national defense in the new era. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/whitepaper/201907/24/content_WS5d3941ddc6d08408f502283d.html.

- Tangredi, S. J. (2019). Anti-access warfare: Countering A2/AD strategies. Naval Institute Press.

- Tilghman, A. (2023, August 3). Guam: Defense infrastructure and readiness (R47643). Congressional Research Service. Available online: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R47643.

- U.S. Department of Defense. (2023, April 3). Philippines, U.S. announce locations of four new EDCA sites. Available online: https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3349257.

- U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. (2023, May 9). Tentative manual for expeditionary advanced base operations (2nd ed.). Available online: https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Docs/230509-Tentative-Manual-For-Expeditionary-Advanced-Base-Operations-2nd-Edition.pdf.

- U.S. Navy. (2021b, August 31). Standard Missile (SM) family. Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Resources/Fact-Files/Display-FactFiles/Article/2169011.

- U.S. Navy. (2021c, September 27). Tomahawk cruise missile. Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Resources/Fact-Files/Display-FactFiles/Article/2169229.

- U.S. Navy. (2024, May 10). U.S. Navy destroyer conducts freedom of navigation operation in the South China Sea. Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3771407.

- U.S. Pacific Fleet. (2024, December 6). 7th Fleet conducts freedom of navigation operation. Available online: https://www.cpf.navy.mil/Newsroom/News/Article/3987553.

- U.S. Department of Defense. (2023, April 3). Philippines, U.S. announce locations of four new EDCA sites. Available online: https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3349257.

- U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. (2023, May 9). Tentative manual for expeditionary advanced base operations (2nd ed.). Available online: https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Docs/230509-Tentative-Manual-For-Expeditionary-Advanced-Base-Operations-2nd-Edition.pdf.

- U.S. Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory. (2023, May 9). Tentative manual for expeditionary advanced base operations (2nd ed.). Available online: https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Docs/230509-Tentative-Manual-For-Expeditionary-Advanced-Base-Operations-2nd-Edition.pdf.

- U.S. Navy. (2021a, April 23). P-8A Poseidon—Multi-mission maritime aircraft (Fact file). Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Resources/Fact-Files/Display-FactFiles/Article/2166300.

- U.S. Navy. (2024, May 10). U.S. Navy destroyer conducts freedom of navigation operation in the South China Sea. Available online: https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/News-Stories/Article/3771407.

- Wang, J. S. (2019). Strategic stability and Sino–U.S. crisis management [in Chinese]. World Economics and Politics, 37(5), 23–40.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).