3.4. Taxonomy

Considering the genera currently included in Acestrorhamphidae Melo et al. 2024 that contain species historically assigned to the genus Astyanax Baird and Girard 1854 (sensu lato), H. santae (Eigenmann 1907) and A. turmalinensis Triques, Vono and Caiafa 2003, as well as P. rivularis (Lütken 1875), can be assigned to the genus Psalidodon Eigenmann 1911, rather than to Astyanax Baird & Girard 1854 (sensu stricto), Hemigrammus Gill 1858 (sensu stricto), Deuterodon Eigenmann 1907, Hyphessobrycon Durbin 1908 (sensu stricto), Megalamphodus Eigenmann 1915, Jupiaba Zanata 1997, Andromakhe Terán, Benitez and Mirande 2020, or Makunaima Terán, Benitez and Mirande 2020, based on the following combination of characters: absence of circuli on the posterior margin of the scales (vs. present in Astyanax and Jupiaba), presence of a black spot on the caudal peduncle (vs. absent in Hemigrammus), anterior laterosensory pore to the dilator fossa oriented lateroventrally (vs. dorsomedially oriented in Deuterodon), absence of the dorsal expansion of the rhinosphenoid between the olfactory nerves (vs. present in Deuterodon, Jupiaba, and Makunaima), numerous and small hooks per ray on the anal fin of males (vs. a pair of large hooks per ray on the anal fin in Hyphessobrycon, and absence of hooks in Jupiaba), absence of a conspicuous black blotch on the dorsal fin (vs. present in Megalamphodus), origin of the anal fin posterior to the vertical through the last dorsal-fin ray (vs. anterior in Andromakhe), and presence of a longitudinal black stripe (vs. absent in Makunaima).

Psalidodon rivularis (Lütken 1875)

Tetragonopterus rivularis Lütken 1875: 107-109, board V, fig. 13 (in part; lectotype and paralectotypes: ZMUC, MNHN 0000-9582, NMW 57707, SMNS 2046, ZMB 9199, USNM 44960, type locality: das Velhas river and its tributaries, Minas Gerais state, Brazil) [

5]—. Bertin and Estève 1948:21 (catalog of fish types from the Muséum national d'Histoire Naturelle) [

50] —. Nielsen 1974:46 (catalog of fish types from Zoological Museum of Copenhagen) [

51] —. Fricke 1995:9 (catalog of fish types from Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde in Stuttgart) [

52].

Astyanax scabripinnis rivularis—. Eigenmann 1910: 433 (transfer to

Astyanax as a subspecies of

Astyanax scabripinnis) [

53] —. Moreira-Filho and Bertollo 1991: 331-357 (citation as a valid subspecies in the

A. scabripinnis complex) [

3].

Astyanax rivularis—. Casatti and Castro 1998:232 (valid species in the genus

Astyanax) [

54] —. Buckup in Reis et al., 2003:112 (list of species) [

55] —. Bertaco and Lucena 2006: 58 (citation as a valid species in the

A. scabripinnis complex) [

43] —. Ingenito and Duboc 2014: 282 (Citation in the

A. scabripinnis complex) [

56] —. Pasa et al. 2019:307-314 (distribution in the upper São Francisco River) [

57] —. Silva et al. 2020:6 (list of species, expansion of distribution to the state of Bahia, Brazil) [

58].

Psalidodon rivularis—. Terán, Benitez and Mirande 2020:11 (transfer to

Psalidodon) [

2] —. Rodrigues-Oliveira et al. 2023 (distribution in upper and middle São Francisco River) [

59] —. Quintela, Teixeira and Pompeu et al. 2024:6 (ichthyofauna Lagoa Santa, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil) [

60].

Diagnosis. Psalidodon rivularis differs from P. alleni, P. argentum, P. balbus, P. bifasciatus, P. biotae, P. bockmanni, P. chico, P. correntinus, P. dissensus, P. dissimilis, P. eigenmanniorum, P. erytropterus, P. fasciatus, P. gymnodontus, P. gymnogenys, P. henseli, P. hermosus, P. ita, P. jequitinhonhae, P. marionae, P. minor, P. ojiara, P. parahybae, P. pelegrini, P. powelli, P. puka, P. pynandi, P. rutilus, P. saguazu, P. schubarti, P. troya, P. vermilion, and P. xiru by having a robust head, with the snout contour to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “U” shape in lateral view (vs. compressed head, with the snout contour to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “V” shape). It differs from P. anisitsi and P. xavante by having 14–21 branched rays in the anal fin (vs. 21–25 in P. anisitsi and 23–26 in P. xavante); from P. brachypterygium, P. cremnobates, P. endy, P. goyanensis, P. paranae, P. rioparanaibanus, and P. varzeae by having a reticulated chromatophore pattern in the anterior body region below the lateral line (vs. scattered pattern); from P. crenuchoides, P. hamatus, P. kalunga, P. leonidas, P. pampa, P. pessalli, P. togoi, P. tumbayaensis, P. uaiso, and P. uberaba by having a variable lateral line (vs. always incomplete in P. crenuchoides, P. hamatus, P. kalunga, P. pessalli, P. togoi, P. uaiso, and P. uberaba; and always complete in P. leonidas, P. pampa, and P. tumbayaensis); and from P. laticeps, P. scabripinnis, and P. serratus by having a vertically elongated humeral spot (vs. horizontally elongated humeral spot with an anterior vertical extension giving it a “p” shape).

Description. Morphometric data are available in

Table 6. Body compressed, greatest body depth generally located at the vertical passing through the middle of the pectoral fin or rarely located at the vertical near the origin of the dorsal fin (in some individuals with body depth greater than 30.50% of standard length). Dorsal profile of the head slightly convex from the tip of the upper lip to the vertical anterior to the nostril; usually convex, but sometimes straight or slightly concave from this point to the supraoccipital process; convex from this point to the base of the last dorsal-fin ray; slightly convex, sometimes straight, from the dorsal fin to the adipose fin; slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the uppermost caudal-fin ray. Ventral profile from the tip of the snout to the base of the pelvic fin convex; from the pelvic fin to the base of the first anal-fin ray continuously convex or straight; anal-fin base straight; and slightly concave between the last anal-fin ray and the base of the lowermost caudal-fin ray.

Terminal mouth with lower jaw slightly projecting beyond upper jaw. Premaxilla with two tooth series: outer series with 3–4 tricuspid teeth and inner series with 4–5 teeth bearing 4–7 cusps. Maxilla with 1–2 small tricuspid or pentacuspid teeth. Dentary teeth abruptly decreasing in size posteriorly, with 4–5 large teeth bearing 5–6 cusps followed by 4–9 smaller teeth. In all teeth, the central cusps are larger than the lateral cusps. Maxilla extending posteriorly beyond the vertical through the anterior margin of the orbit.

Dorsal fin with ii+9 rays, first unbranched ray about half the length of the second. Pectoral fin with i+11–14 rays, usually i+12-13 (f = 62.86%), origin near the vertical through the middle of the opercular bone; when adpressed against the body, never reaching the pelvic fin in larger individuals. Pelvic fin with i+6–7 rays, usually i+7 (f = 93.75%), origin anterior to the vertical through the last dorsal-fin ray; when adpressed against the body, never reaching the anal fin in larger individuals. Anal fin with iv+14–21 rays, usually with iv+18-20 (f = 69.39%); mature males with numerous small hooks per ray on the anal fin. Caudal fin forked, with i+17+i rays and lobes of similar size. Adipose fin present.

Cycloid scales, circuli absent on the posterior margin of scales; 4–17 radii on scales, generally more numerous in larger individuals. Lateral line variable, complete, incomplete, or interrupted, usually complete (f = 81.95%). Lateral series with 37–39 scales, usually 37-38 (f = 78.38%). Perforated scales along lateral series with 32-39 scales, usually 37-38 (f = 69.57%). Transverse scale series with 5–6 scales above and 4–5 scales below the lateral line, usually 5 above (f = 83.01%) and 4 below (f = 87.58%). Predorsal scale series with 11–13 scales, usually 12 (f = 62.16%). Circumpeduncular scale series with 11–15 scales, usually 13-14 (f = 77.78%). Anal-fin base scale series with 3–7 scales, usually 4-5 (f = 68.75%).

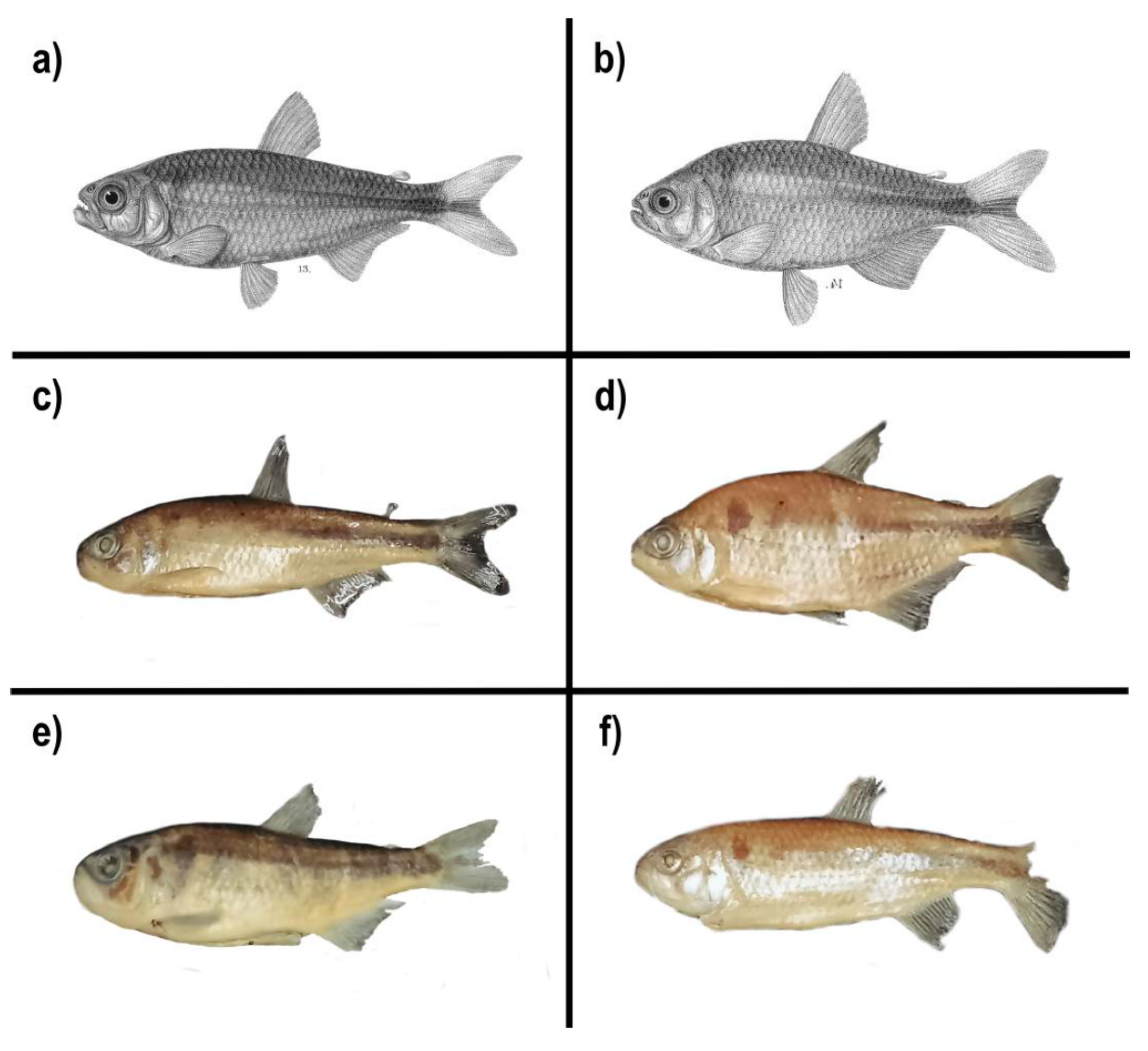

Coloration in alcohol. Dorsal region of the body, head, and tip of the snout dark brown. Lateral and ventral regions of the body yellowish-brown or slightly silvery. Infraorbital and opercular regions are silvery, with a dark patch of chromatophores on the opercle. Reticulated pattern of chromatophores on the anterior region of the body below the lateral line, that is, restricted to the posterior margin of the scales. Scattered pattern of chromatophores between the lateral line and the base of the anal fin. Conspicuous humeral blotch extending 2–3 scales above the lateral line and 1–2 scales below, with the upper margin wider than the lower margin. Some specimens have a second diffuse humeral blotch after the first; its absence in others may be due to the preservation process. Regions anterior and posterior to the first humeral blotch are pale, with some specimens showing a reticulated pattern of chromatophores after the blotch. Lateral stripe extending from the second humeral blotch to the median rays of the caudal fin, silvery in its anterior portion and becoming darker toward the caudal peduncle, where it extends dorsoventrally forming a distinct blotch on the margin of the caudal peduncle. Rayed fins hyaline, generally with few chromatophores along the margins of the rays. Adipose fin hyaline with a scattered pattern of chromatophores.

Live coloration. Dorsal region of the body and head dark, brownish green on the back, becoming olive-green toward the flanks. Area around the lateral line silvery, turning whitish on the belly. Paired fins whitish. Dorsal fin white or yellowish. Adipose fin yellowish. Anal fin whitish, sometimes with the margin near the body yellowish to reddish. Caudal fin with broad reddish and yellowish margins surrounding the dark lateral stripe.

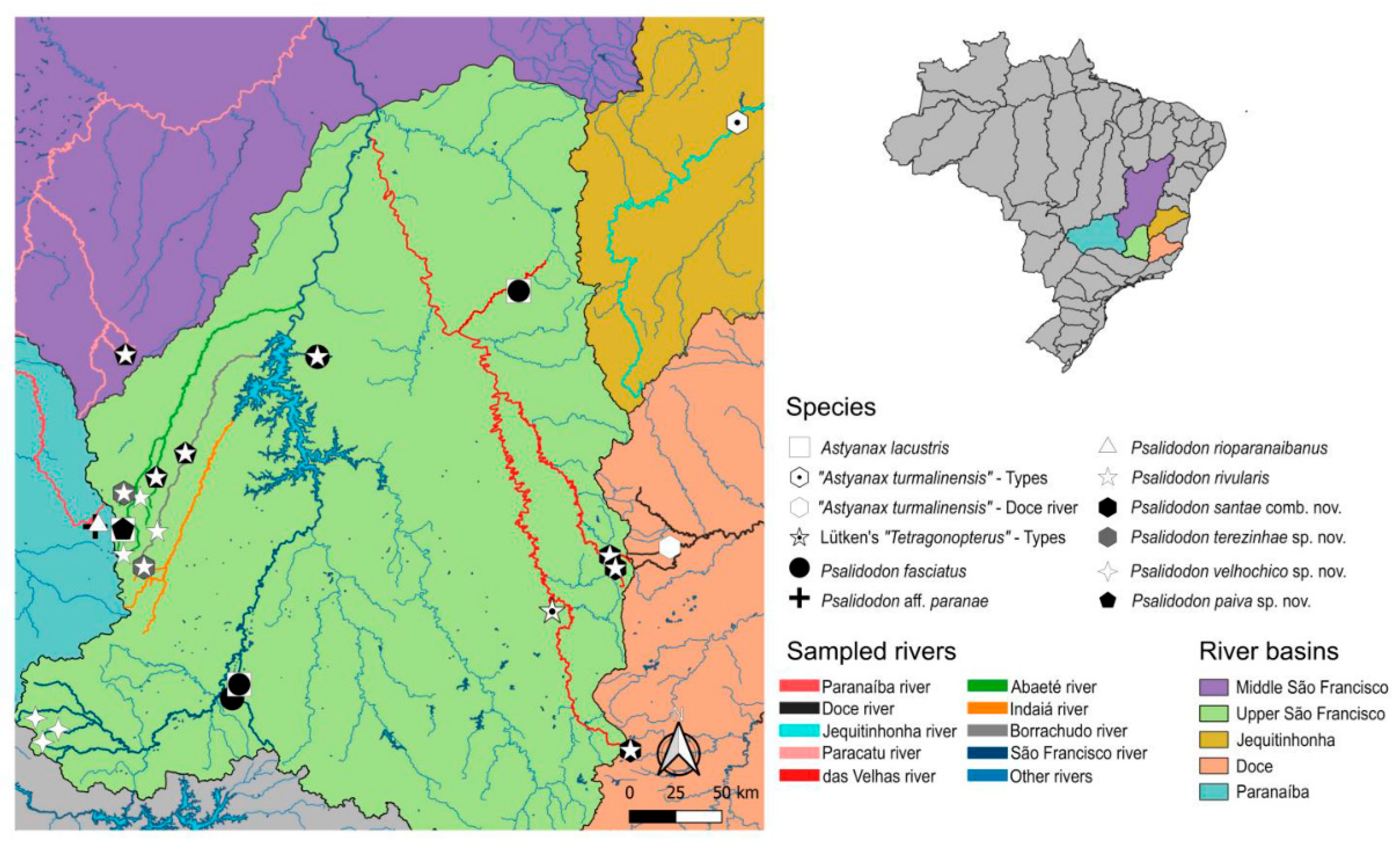

Distribution. Psalidodon rivularis sensu stricto can be found in the Upper and Middle São Francisco River basins, from its easternmost portion in the Cipó and das Velhas rivers to its westernmost portion in the Abaeté and Paracatu rivers. Among other rivers where this species occurs, noteworthy are the sub-basins of the Indaiá and Borrachudo rivers, as well as smaller tributaries that drain directly into the São Francisco River (

Figure 1).

Sexual dimorphism. Reproductive males bear hooks on the anal and pelvic fins, from the last unbranched ray to the 15th branched ray of the anal fin, and from the 3rd to the 5th branched ray of the pelvic fin (see Oliveira [

14]).

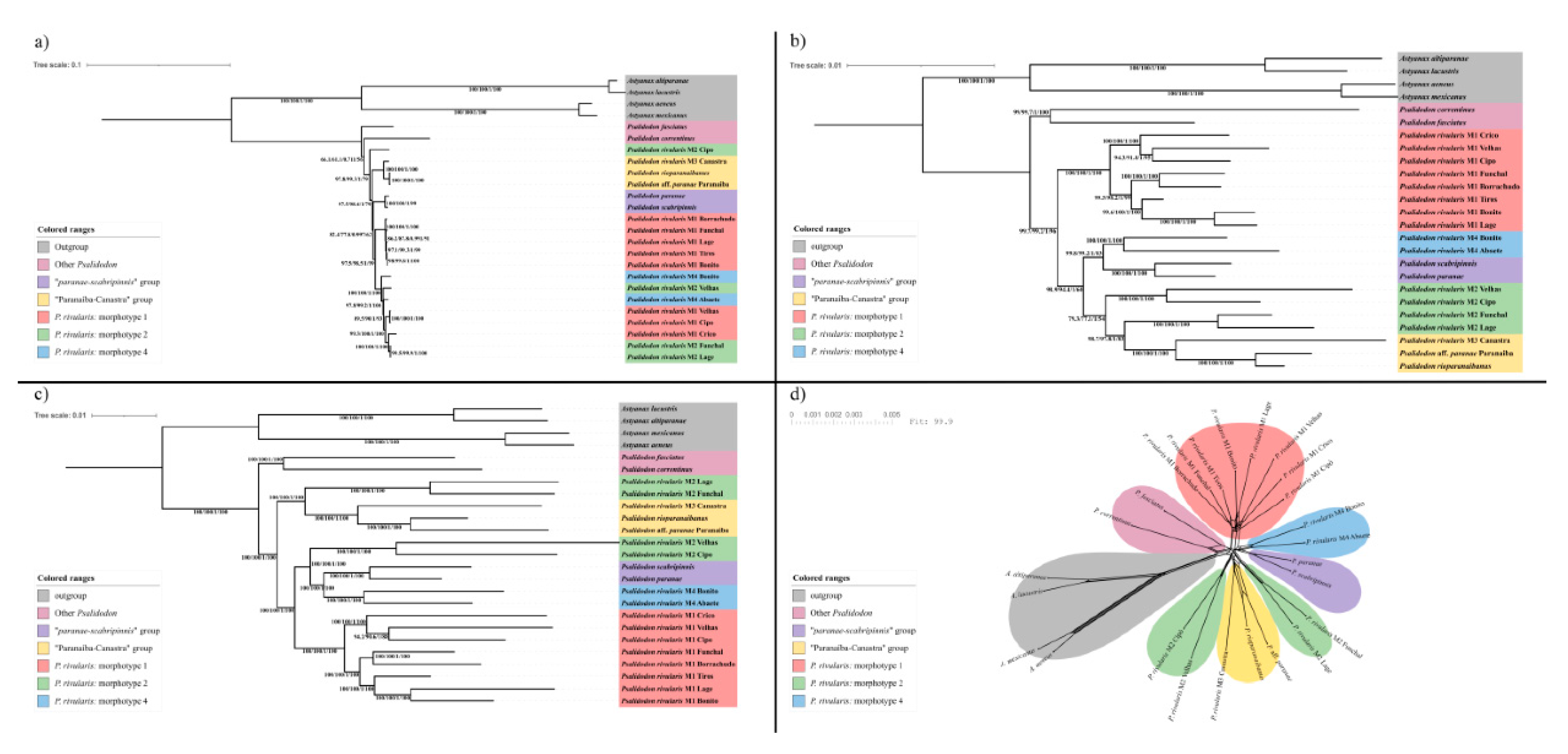

Remarks. Here we define

P. rivularis sensu stricto as only the M1 individuals of

P. rivularis sensu lato (

Figure 4, red clade). This interpretation is based on the confirmation of two distinct species historically identified under the name

Tetragonopterus rivularis in the type series analyzed by Lütken [

5], or later as

Psalidodon / “Astyanax” rivularis in other ichthyological collections (eg., LaGEEvo UFV CRP). We restrict

Psalidodon rivularis sensu stricto as all specimens belonging to the same morphotype as the lectotype of

Tetragonopterus rivularis (NHMD1634879), whose photograph and radiograph are available on the Natural History Museum of Denmark collections website (

https://collections.snm.ku.dk/en), and in figure 13 of plate V of Lütken’s work Velhas-Flodens Fiske [

5].

This narrower definition reduces the morphological variability attributed to the species in previous works. Among the affected characteristics, the most notable are the number of scales along the lateral series and morphometric proportions, particularly body height. Lütken [

5] described

Tetragonopterus rivularis as having 33–38 scales along the lateral series, while other studies expanded this range to 32–40 [

57,

61]. Under our definition,

Psalidodon rivularis sensu stricto presents 37–39 scales along the lateral series. Similarly, based on Lütken’s [

5] notes, it is possible to infer that the specimens he analyzed had a body height ranging from 31.58% to 37.50% of the standard length. Other studies broaden this range in

Psalidodon rivularis to 22.06%–46.00% [

43,

57]. Here, we define

Psalidodon rivularis as individuals with proportionally shallower bodies, with body height ranging from 25.30% to 33.10% of the standard length.

Material Examined. 154 specimens (4 from photographs), all from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Types: São Francisco River Basin. Sub-basin of the Velhas River: ZMUC P241289 (photograph), lectotype of Tetragonopterus rivularis, 1 specimen, standard length: 80.7 mm, Lagoa Santa municipality – MG, J. T. Reinhardt, 1847–1870. USNM 44960 (photograph), paralectotypes of Tetragonopterus rivularis, 2 specimens, standard length: 36.6–67.8 mm, Lagoa Santa municipality – MG, J. T. Reinhardt, 1847–1870. Non-types. São Francisco River Basin. Sub-basin of the Abaeté River: LaGEEvo-30, 12 of 13 specimens, standard length: 45–63.5 mm, Arapuá municipality – MG, Lage stream, 19°1’25.18” S 46°6’18.74” W, I.H.R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, T. da S. Ramos, 05 Nov 2022. LaGEEvo-41, 17 of 31 specimens, standard length: 48–79.5 mm, Arapuá municipality – MG, Lage stream, 19°1’25.18” S 46°6’18.74” W, P. Penteado, D. Reis, Denis, Paloma, Wanessa, 23 Jul 2010. LaGEEvo-56, 14 of 18 specimens, standard length: 48–69 mm, Tiros municipality – MG, Tiros stream, 18°56'34.08" S 45°56'18.20" W, P. Penteado, Denis, Gabriel, Rafael, 20 Jul 2010. LaGEEvo-74, 11 specimens, standard length: 42–91 mm, São Gotardo municipality – MG, Confusão stream, 19°20'21.89" S 46°6'21.38" W, I. H. R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, W. Cléber, 11 Nov 2024. LaGEEvo-75, 4 specimens, standard length: 56–87.5 mm, Tiros municipality – MG, Espinha stream, 19°2'47.18" S 46°1'12.93" W, Campos, M. A. da Silva, S. V. Resende, R. Pasa, 24 Jul 2016. Sub-basin of the Velhas River: MCZ 20874 (photograph), 1 of 3 specimens, standard length: 67.61 mm, Lagoa Santa – MG, 19°27’26’’ S 44°14’30’’ W, G. Sceva & Thayer Expedition, July 1865. LaGEEvo-33, 4 specimens, standard length: 46.0–69.5 mm, Ouro Preto municipality – MG, Velhas River, 20°20'38.4" S 43°29'58.4" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. Pasa, 15 Sep 2023. Sub-basin of the Borrachudo River: LaGEEvo-34, 3 specimens, standard length: 53–69 mm, Matutina municipality – MG, Borrachudo River, 19°13'02.6" S 45°55'58.2" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, R. A. S. Soares, R. Pasa, 08 Mar 2023. LaGEEvo-40, 12 of 15 specimens, standard length: 64–86 mm, Tiros municipality – MG, Bonito stream, 18°48'44.7" S 45°45'52.2" W, P. Penteado, Denis, Gabriel, Rafael, 20 Jul 2010. Sub-basin of the Indaiá River: LaGEEvo-36, 4 specimens, standard length: 41–46 mm, São Gotardo municipality – MG, Funchal River, 19°24'9.54" S 46°0'4.61" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, 02 Dec 2023. LaGEEvo-37, 2 specimens, standard length: 47–56 mm, São Gotardo municipality – MG, Funchal River, 19°24'9.54" S 46°0'4.61" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, L. Fainé, J. Godoy, 04 May 2019. LaGEEvo-59, 3 specimens, standard length: 50–65 mm, São Gotardo municipality – MG, Funchal River, 19°24'9.54" S 46°0'4.61" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, G. Bork, L. Fernandes, V. Augusto, 12 May 2018. Sub-basin of the Paracatu River: LaGEEvo-43, 9 specimens, standard length: 37–63 mm, Presidente Olegário municipality – MG, Crico stream, 18°18'44.36" S 46°5'44.46" W, I. B. da Silva, M. L. C. B. de Campos, V. Augusto, S. V. Resende, 06 Apr 2019. Sub-basin of the Cipó River: LaGEEvo-44, 4 specimens, standard length: 43–52 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, Bandeirinhas Canyon, 19°25'8.33" S 43°34'12.37" W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, R. R. Rocha, S. V. Resende, F. Sassi, October 2017. LaGEEvo-46, 9 specimens, standard length: 42–59 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, Bandeirinhas stream, 19°24'32.65" S 43°34'35.31" W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, R. R. Rocha, S. V. Resende, F. Sassi, October 2017. LaGEEvo-48, 23 specimens, standard length: 47–84 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, confluence of Mascates and Bocaina Rivers, 19°20'49.68" S 43°36'20.42" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, G. F. da Fonseca, G. F. Matos, V. G. de Miranda, B. Alonso, 09 Oct 2023. LaGEEvo-60, 11 specimens, standard length: 64–99 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, Farofa Waterfall trail, 19°23'6.52" S 43°35'12.28" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, G. F. da Fonseca, G. F. Matos, V. G. de Miranda, B. Alonso, 10 Oct 2023. São Francisco River: LaGEEvo-63, 4 specimens, standard length: 50–81 mm, Três Marias – MG, Vereda Grande River, 18°19'18.62" S 45°6'32.80" W, R. de M. Alves; R. R. Rocha; M. A. da Silva; S. V. Resende, 18 Apr 2017. LaGEEvo-64, 5 specimens, standard length: 50–81 mm, Três Marias – MG, Vereda Grande River, 18°19'18.62" S 45°6'32.80" W, 2010–2012.

New combinations: Psalidodon santae (Eigenmann, 1907) comb. nov.

Tetragonopterus rivularis Lütken, 1875: 107-109, board V, fig. 14 (in part; paralectotypes: ZMUC, MNHN 0000-9582, NMW 57707, SMNS 2046, ZMB 9199, type locality: das Velhas river and its tributaries, Minas Gerais state, Brazil) [

5].

Hemigrammus santae Eigenmann 1907: 16-17, (syntypes: USNM 55652, type locality: municipality of Lagoa Santa, Minas Gerais state, Brazil) [

6] —. Vari and Howe 1991:25 (species catalog of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution) [

62].

Hyphessobrycon santae —. Eigenmann 1910:437 (Transfer to the genus

Hyphessobrycon) [

53] —. Lima and Malabarba in Reis et al. 2003:140 (list of species) [

63] —. Silva et al. 2020:6 (list of species, expansion of distribution to the state of Bahia, Brazil) [

58].

Astyanax turmalinensis Triques, Vono and Caiafa 2003: 145–150, fig. 1 (Holotype: DZUFMG: 005; Paratypes: DZUFMG: 006-009, type locality: Divisão stream, tributary of the right bank of the Jequitinhonha River, village of Peixe Crú, municipality of Turmalina, Minas Gerais state, Brazil, 17°07’ S 42°57’ W.) [

7] —. Zanata and Camelier 2009: 37 (inclusion in the

A. scabripinnis complex) [

64] —. Triques and Queiroz 2010: 400–401, fig. 1 (expansion of distribution to the São Francisco and Doce river basins) [

8] —. Ingenito and Duboc 2014: 282 (Citation in the

A. scabripinnis complex) [

56] —. Vieira-Guimaraes et al. 2024:37 (list of species) [

65].

[Syn. nov.]

Diagnosis. Psalidodon santae differs from P. alleni, P. argentum, P. balbus, P. bifasciatus, P. biotae, P. bockmanni, P. chico, P. correntinus, P. dissensus, P. dissimilis, P. eigenmanniorum, P. erytropterus, P. fasciatus, P. gymnodontus, P. gymnogenys, P. henseli, P. hermosus, P. ita, P. jequitinhonhae, P. marionae, P. minor, P. ojiara, P. parahybae, P. pelegrini, P. powelli, P. puka, P. pynandi, P. rutilus, P. saguazu, P. schubarti, P. troya, P. vermilion, and P. xiru by having a robust head with the contour from the snout to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “U” shape in lateral view (vs. compressed head with the contour from the snout to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “V” shape). It differs from P. anisitsi, P. crenuchoides, and P. xavante by having 15–21 branched anal-fin rays (vs. 21–25 in P. anisitsi, 11–14 in P. crenuchoides, and 23–26 in P. xavante); from P. hamatus, P. kalunga, P. leonidas, P. pampa, P. pessalii, P. togoi, P. tumbayaensis, P. uaiso, and P. uberaba by presenting a variable lateral line (vs. always incomplete in P. hamatus, P. kalunga, P. pessalii, P. togoi, P. uaiso, and P. uberaba; and always complete in P. leonidas, P. pampa, and P. tumbayaensis); from P. brachypterygium, P. cremnobates, P. endy, P. goyanensis, P. paranae, P. rioparanaibanus, and P. varzeae by having a reticulated chromatophore pattern on the anterior body region below the lateral line (vs. dispersed pattern); from P. laticeps, P. scabripinnis, P. serratus, and P. togoi by having a vertically elongated humeral spot (vs. horizontally elongated humeral spot with a vertical extension on its anterior portion, giving it a “p”-shaped form); and from P. rivularis by having 33–36 scales in the lateral series and 2n = 50 chromosomes (vs. 37–39 scales and 2n = 46 chromosomes).

Description. Morphometric data are available in

Table 7. Body compressed, greatest body depth located on the vertical near the origin of the pelvic fin. Dorsal profile of head slightly convex between the tip of the upper lip and the vertical anterior to the nostril; slightly convex from this point to the vertical situated near the middle of the eye, and then straight or slightly concave from this point to the supraoccipital process. Convex profile from the supraoccipital process to the base of the last dorsal-fin ray; slightly convex from the dorsal to the adipose fin, and slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the uppermost caudal-fin ray. Ventral profile from tip of snout to pelvic-fin base convex; between pelvic fin and base of first anal-fin ray continuously convex or straight; anal-fin base straight; and slightly concave between adipose fin and base of the lowermost caudal-fin ray.

Mouth terminal, lower jaw slightly projecting beyond upper jaw. Premaxilla with two series of teeth, the outer with 3–5 tricuspid teeth and the inner with 4–5 teeth bearing 3–7 cusps. Maxilla with 1–3 small tricuspid or pentacuspid teeth. Dentary with teeth decreasing abruptly in size, 4–5 large teeth with 4–5 cusps followed by 3–8 smaller teeth. In all teeth, the central cusps are larger than the lateral cusps. Posterior end of maxilla extending beyond vertical through anterior margin of orbit.

Dorsal fin with ii+9 rays, first unbranched ray half the length of the second. Pectoral fin with i+11–13 rays, usually i+11-12 (f = 79.31%), its origin near the vertical through the middle of the opercle; when adpressed against the body, it never reaches the pelvic fin in larger individuals. Pelvic fin with i+6–7 rays, usually i+7 (f = 90.91%), its origin anterior to the vertical through the last dorsal-fin ray; when adpressed against the body, it never reaches the anal fin in larger individuals. Anal fin with iv+16–22 rays, usually iv+19-20 (f = 65.12%), mature males with numerous small hooks per ray on the anal fin. Caudal fin bifurcated, with i+17+i rays and lobes of similar size. Adipose fin present.

Cycloid scales, posterior margin lacking circuli, with 4–17 radii, generally more numerous in larger individuals. Lateral line variable, being complete, incomplete, or interrupted, usually incomplete or interrupted (f = 56.25%). Longitudinal series with 33–36 scales, usually 34-35 (f = 67.15%). Perforated scales along lateral series with 10-36 scales, usually 31-36 scales (f = 56.25%). Transverse scale rows 5–6 above and 4–5 below the lateral line, usually 6 above (f = 61.11%) and 4 below (f = 74.65%). Predorsal series with 10–13 scales, usually 11-12 (f = 75.76%). Circumpeduncular series with 12–14 scales, usually 13-14 (f = 84.38%). Anal-fin base series with 4–7 scales, usually 4 (f = 55.56%).

Color in alcohol. Dorsal region of body, head, and tip of snout dark brown. Lateral region of body yellowish-brown or slightly silvery in its anterior portion. Ventral region of body yellowish-brown, sometimes with orange to reddish reflections. Infraorbital and opercular regions are silvery, with a dark chromatophore blotch on the opercle, more discreet in some individuals. Reticulated pattern of chromatophores (restricted to posterior margin of scales) on the anterior region of body below the lateral line. Scattered chromatophores between the lateral line and the base of the anal fin. Conspicuous humeral blotch extending 2–3 scales above and 1–2 scales below the lateral line, with upper margin wider than the lower. Usually, a clear area occurs after the humeral blotch with a reticulated pattern of chromatophores, followed by a second diffuse humeral blotch. In a few individuals, this blotch is absent, possibly due to the preservation process. Lateral stripe extending from the second humeral blotch to the median caudal-fin rays, silvery in its anterior portion and becoming darker toward the caudal peduncle, where it elongates dorsoventrally forming a distinct blotch on the caudal peduncle margin. Rayed fins hyaline, usually with few chromatophores along fin-ray margins. Adipose fin hyaline with a scattered chromatophore pattern.

Color in life. Dorsal region of body and head dark, brownish green on dorsum and becoming olive-green toward the flanks. Area around lateral line silvery, turning whitish to yellowish on ventral region. Pectoral fins vary from slightly yellowish to orange. Pelvic fins range from yellowish to intensely reddish. Dorsal fin yellowish green, becoming reddish toward its distal portion. Adipose fin yellowish to orange. Anal fin reddish near its base, fading distally. Caudal fin with broad reddish and yellowish margins surrounding the dark lateral stripe.

Distribution. Psalidodon santae comb. nov. is found east of the São Francisco River, in the upper São Francisco, Jequitinhonha, and Doce River basins, and possibly in the middle São Francisco. In the eastern portion of the upper São Francisco basin, we observed

P. santae to be sympatric with

P. rivularis in at least two localities: the headwaters of the das Velhas river in Ouro Preto, Minas Gerais, and in different tributaries of the Cipó river within Serra do Cipó National Park (

Figure 1).

Sexual dimorphism. Reproductive males bear hooks on the anal and pelvic fins, from the last unbranched ray to the 15th branched ray of the anal fin, and from the 3rd to the 5th branched ray of the pelvic fin (see Oliveira [

14]).

Remarks. Here, we define

P. santae comb. nov. as only the M2 individuals of

P. rivularis sensu lato found east of the São Francisco River (

Figure 4, green clade, Velhas and Cipó specimens).

Hemigrammus santae Eigenmann 1907 was described by Eigenmann based on a lot containing four syntypes of Tetragonopterus rivularis Lütken 1875 (USNM 44960). The specimens comprised two varieties of

“T.” rivularis, with two specimens each, distinguished by the presence of either a complete or an interrupted lateral line [

6]. From these, Eigenmann described the new species based on the variety with an interrupted lateral line (

Tetragonopterus rivularis var. interrupta Lütken 1875), assigning the specimens to catalog number USNM 55652.

Years later, Eigenmann himself transferred the species to the genus

Hyphessobrycon, using the naked caudal fin in

Hyphessobrycon as a diagnostic character between the two genera [

53]. However, Eigenmann did not consider an important aspect when proposing the species: Lütken [

5] had noted in his work that he did not consider the interruption of the lateral line a valid character for naming a new species, since in many cases this feature was inconsistent between the two sides of the same specimen of

“T.” rivularis. This misunderstanding was perpetuated in subsequent works, such as the fish identification manual for the Três Marias region [

66], where in the identification key for fishes of the São Francisco River basin, an incomplete lateral line leads to the genera

Hemigrammus and

Hyphessobrycon, and a complete lateral line to the genus

Astyanax, which at that time included

P. rivularis.

Although we consider

P. santae (Eigenmann 1907) to be a valid species, we emphasize that it is not the lateral line that distinguishes it from

P. rivularis (Lütken 1875), since even in the type series there are specimens belonging to

P. rivularis sensu stricto that have an interrupted lateral line. It is worth noting that in recent years, several

Hyphessobrycon species have been transferred to the genus

Psalidodon, increasing the number of species in the group with specimens exhibiting an interrupted lateral line [

2,

11].

The analysis of the types of

Astyanax turmalinensis Triques, Vono and Caiafa 2003, shows that this taxon corresponds to the same species as

P. santae (Eigenmann 1907). Because they were assigned to different genera, Triques et al. [

7] and Triques and Queiroz [

8] did not provide diagnoses differentiating these species. Therefore, we consider that the overlap in meristic characters, morphometrics, and spatial distribution justifies the synonymy of both taxa.

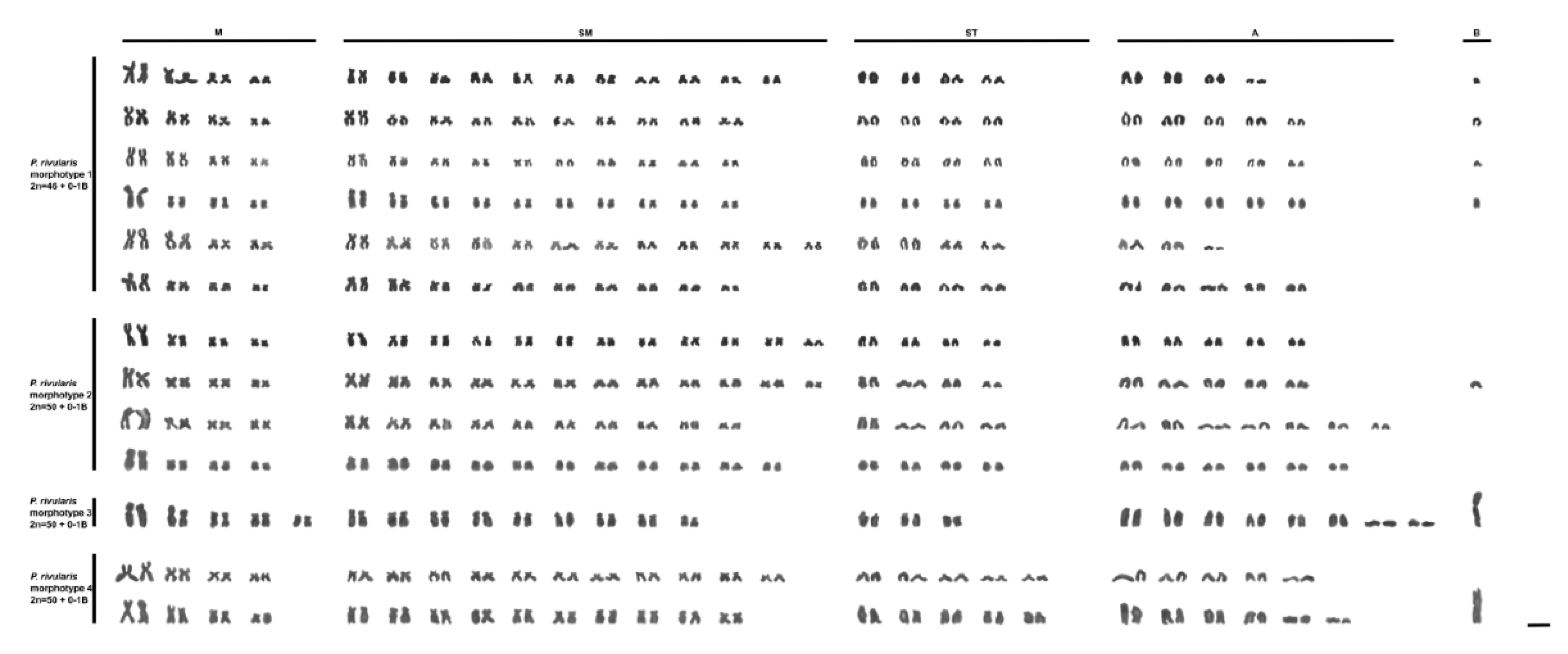

Regarding the morphological diagnosis of

P. santae (Eigenmann 1907), and

P. rivularis (Lütken 1875), the main distinguishing features are the lower number of scales along the lateral series in

P. santae (33–36 vs. 37–39) and the higher chromosome count (2n = 50 + 0–1 B chromosomes vs. 2n = 46 + 0–2 B chromosomes). Other differences between these species include body coloration and morphometric traits, as noted by Eigenmann [

6], with

P. santae exhibiting a darker body, more colorful fins, and generally a taller body, with body height ranging from 31.15% to 38.48% (or possibly more) of standard length.

Additional characters noted by Triques and Queiroz [

8] in the diagnosis of

A. turmalinensis and

“Astyanax” rivularis may also be used, though with caution: the origin of the pectoral fin is generally more anterior in

P. rivularis, situated near the vertical at the midpoint of the opercle in this species, whereas in

P. santae it originates posterior to the opercle; the region of greatest body height is generally positioned near the vertical at the origin of the pelvic fin in

P. santae and near the vertical at the middle of the pectoral fin in

P. rivularis, although this trait may reverse in relatively taller specimens of

P. rivularis (body height > 30.50% of standard length) and relatively shorter specimens of

P. santae (body height < 33.00% of standard length); the chromatophore pattern after the first humeral spot is generally reticulated (chromatophores restricted to the posterior edge of the scales) in

P. santae and dispersed in

P. rivularis.

Triques and Queiroz [

8] also noted the presence of two humeral spots in

P. santae versus one in

P. rivularis. Here we emphasize that, in fact, we observe specimens with two spots in both species, and the absence of the second spot often results from it being less distinct and lost during preservation, although it should be noted that in live or freshly fixed specimens the second spot tends to be more conspicuous in

P. santae.

Material Examined. 74 specimens (four from photographs), all from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Types: São Francisco River Basin. Velhas River sub-basin: ZMUC P241372 (photograph), paralectotype of Tetragonopterus rivularis, 1 specimen, standard length 70.1 mm, municipality of Lagoa Santa – MG, J. T. Reinhardt, 1847–1870. ZMUC P241376 (photograph), paralectotype of Tetragonopterus rivularis, 1 specimen, standard length 35.7 mm, municipality of Lagoa Santa – MG, J. T. Reinhardt, 1847–1870. USNM 55652 (photograph), syntypes of Hemigrammus santae, 2 specimens, standard length 32.5–54.1 mm, municipality of Lagoa Santa – MG, J. T. Reinhardt, 1847–1870. Jequitinhonha River Basin: DZUFMG 005, holotype of Astyanax turmalinensis, 1 specimen, standard length 48.2 mm, municipality of Turmalina – MG, village of Peixe-Crú, Divisão stream, right tributary of the Jequitinhonha River, 17°07′ S 42°57′ W, V. Vono, May 1989. DZUFMG 009, paratypes of Astyanax turmalinensis, 19 of 25 specimens, standard length 33.5–54.9 mm, same locality as holotype, V. Vono, August 1989. Non-types. São Francisco River Basin. Velhas River sub-basin: LaGEEvo-32, 21 specimens, standard length 31–49 mm, municipality of Ouro Preto – MG, Velhas River, 20°20′38.4″ S 43°29′58.4″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. Pasa, 15 Sep 2023. Cipó River sub-basin: LaGEEvo-45, 9 specimens, standard length 43–53 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, Bandeirinhas Canyon, 19°25′8.33″ S 43°34′12.37″ W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, R. R. Rocha, S. V. Resende, F. Sassi, October 2017. LaGEEvo-47, 6 specimens, standard length 42–49 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park – MG, Bandeirinhas stream, 19°24′32.65″ S 43°34′35.31″ W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, R. R. Rocha, S. V. Resende, F. Sassi, October 2017. LaGEEvo-49, 8 specimens, standard length 41–59.5 mm, meeting of Mascates and Bocaina rivers, 19°20′49.68″ S 43°36′20.42″ W, I. H. R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, G. F. da Fonseca, G. F. Matos, V. G. de Miranda, B. Alonso, 09 Oct 2023. LaGEEvo-58, 4 specimens, standard length 56–72 mm, Bandeirinhas Canyon, 19°25'8.33" S 43°34'12.37" W, I. H. R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, G. F. da Fonseca, G. F. Matos, V. G. de Miranda, B. Alonso, 11 Oct 2023. LaGEEvo-62, 1 specimen, standard length 63 mm, Serra do Cipó National Park, Farofa waterfall trail, 19°23′6.52″ S 43°35′12.28″ W, I. H. R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, G. F. da Fonseca, G. F. Matos, V. G. de Miranda, B. Alonso, 10 Oct 2023.

New species: Psalidodon terezinhae sp. nov.

Link to zoobank: Registration in zoobank will be carried out after the manuscript is accepted.

Holotype. LaGEEvo-27 (Voucher: LaGEEvo-4521). 53.0mm SL, female, Lage stream, Abaeté river drainage, Arapuá, Minas Gerais state, Brazil, 19°1’25.18” S 46°6’18.74” W, I.H.R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, T. da S. Ramos, 05 Nov 2022.

Paratypes. All specimens are from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco River Basin. Abaeté River sub-basin: LaGEEvo-31, 22 specimens, standard length 38–54 mm, municipality of Arapuá – MG, Lage stream, 19°1′25.18″ S 46°6′18.74″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, T. da S. Ramos, 05 Nov 2022, collected with the holotype.

Non-type material. All specimens are from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco River Basin. Abaeté River sub-basin: LaGEEvo-42, 15 specimens, standard length 36.5–49 mm, municipality of Arapuá – MG, Lage stream, 19°1′25.18″ S 46°6′18.74″ W, P. Penteado, D. Reis, Denis, Paloma, Wanessa, 23 Jul 2010. Indaiá River sub-basin: LaGEEvo-36, 6 specimens, standard length 35–54 mm, municipality of São Gotardo – MG, Funchal River, 19°24′9.54″ S 46°0′4.61″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, 02 Dec 2023. LaGEEvo-38, 1 specimen, standard length 59 mm, municipality of São Gotardo – MG, Funchal River, 19°24′9.54″ S 46°0′4.61″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, L. Fainé, J. Godoy, 04 May 2019.

Diagnosis. In relation to the other species of Psalidodon, the diagnosis of Psalidodon terezinhae sp. nov. is the same as that of P. santae. Among the remaining species of P. rivularis sensu lato, P. terezinhae differs from P. rivularis sensu stricto by having 33–36 scales along the lateral line (vs. 37 or more), a relatively greater body depth (33.97%–38.90% vs. 25.20%–33.10%), and 2n=50 chromosomes (vs. 2n=46). It differs from Psalidodon velhochico sp. nov. by presenting a reticulated pattern of chromatophores on the anterior region of the body below the lateral line (vs. a dispersed pattern), 33–36 scales along the lateral line (vs. 37 or more), greater body depth (33.97%–38.90% vs. 28.06%–33.40%), shorter head length (21.60%–26.19% vs. 26.84%–31.93%), shorter orbit–opercle distance (8.60%–11.00% vs. 13.80%–17.25%), and smaller head depth (59.24%–69.30% vs. 75.44%–87.22%). It differs from Psalidodon paiva sp. nov. by presenting the point of greatest body depth aligned vertically with the origin of the pelvic fin (vs. generally at the middle of the pectoral fin), greater body depth (33.97%–38.90% vs. 28.64%–32.66%), longer anal-fin base length (22.48%–29.16% vs. 15.51%–21.64%), and shorter orbit–opercle distance (8.60%–11.00% vs. 12.24%–14.52%). Although we did not find any discrete character distinguishing P. terezinhae from P. santae, both can be differentiated by overlapping yet statistically distinct morphometric traits: orbit–opercle distance (8.60%–11.00%, mean 9.93% in P. terezinhae vs. 10.31%–14.57%, mean 11.90% in P. santae) and head length (21.60%–26.19%, mean 23.92% in P. terezinhae vs. 23.05%–30.11%, mean 26.68% in P. santae).

Description. Morphometric data are available in

Table 8. Body compressed, region of greatest body depth located vertically near the origin of the pelvic fin. Dorsal profile of head slightly convex from tip of upper lip to vertical through anterior nostril; slightly convex from this point to vertical through posterior margin of eye, then slightly concave from this point to supraoccipital process. Convex from supraoccipital process to base of last dorsal-fin ray; slightly convex from dorsal fin to adipose fin, and slightly concave between adipose fin and base of uppermost caudal-fin ray. Ventral profile from tip of snout to base of pelvic fin convex; from pelvic fin to base of first anal-fin ray continuously convex or straight; base of anal fin straight; and slightly concave between adipose fin and base of lowermost caudal-fin ray.

Terminal mouth, with lower jaw projecting slightly beyond upper jaw. Posterior extension of maxilla reaching vertical through anterior margin of orbit.

Dorsal fin with ii+9 rays, first unbranched ray about half the length of the second. Pectoral fin with i+11–13 rays, usually i+11–12 (f = 82.76%), its origin near vertical through middle of opercle; when adpressed to body, never reaching pelvic fin in larger individuals. Pelvic fin with i+7 rays, usually i+7 (f = 88.89%), its origin anterior to vertical through last dorsal-fin ray; when adpressed to body, never reaching anal fin in larger individuals. Anal fin with iv+18–22 rays, usually iv+20–21 (f = 69.23%). Caudal fin forked, with i+17+i rays, lobes of similar size. Adipose fin present.

Cycloid scales, circuli absent on posterior margin of scales, 4–13 radii on scales, generally more numerous in larger individuals. Lateral line variable, either complete, incomplete or interrupted, usually complete (f = 66.67%). Lateral series with 33–36 scales, usually 35–36 (f = 69.70%). Perforated scales along lateral series with 26-36 scales, usually 35-36 (f = 54.55%). Transverse series with 5–6 scales above lateral line and 4–5 below, usually 6 above (f = 69.70%) and 5 below (f = 87.88%). Predorsal series with 10–12 scales, usually 11–12 (f = 82.76%). Circumpeduncular series with 12–14 scales, usually 13-14 (f = 72.41%). Scales along base of anal fin 4–8, usually 6–7 (f = 68.97%).

Color in alcohol. Dorsal region of body, head, and tip of snout dark brown. Lateral region of body yellowish-brown or slightly silvery in its anterior portion. Ventral region of body yellowish-brown. Infraorbital and opercular regions silvery, with a dark blotch of chromatophores on the opercle, sometimes more discrete in some individuals. Reticulated pattern of chromatophores (restricted to posterior margin of scales) on anterior region of body below lateral line. Scattered chromatophores between lateral line and base of anal fin. Conspicuous humeral blotch extending 2–3 scales above and 1–2 scales below lateral line, with upper margin broader than lower. Clear area posterior to humeral blotch with reticulated pattern of chromatophores, followed by a second diffuse humeral blotch, which may be faint or absent due to preservation. Lateral stripe extending from second humeral blotch to median rays of caudal fin, silvery in its anterior portion and becoming darker towards caudal peduncle, where it elongates dorsoventrally forming a distinct blotch on caudal peduncle margin. Rays of fins hyaline, usually with few chromatophores along margins. Adipose fin hyaline.

Color in life. Dorsal region of body, head, and upper maxilla dark, brownish green on dorsum, becoming olive-green toward flanks. Lower maxilla yellowish. Infraorbital and opercular regions silvery with several dark chromatophore punctuations. First humeral blotch dark, distinct, and vertically elongated. Area around lateral line silvery with greenish reflections. Ventral region of body white with orange or yellowish reflections. Pectoral fins range from slightly yellowish to orange. Pelvic fins range from yellowish to strongly reddish. Dorsal fin yellowish green, becoming reddish toward the tip. Adipose fin yellowish or orange. Anal fin reddish on its proximal portion, fading distally. Caudal fin with broad reddish and yellowish margins surrounding the dark lateral stripe.

Distribution. P. terezinhae was collected in only two localities, the Lage stream and the Funchal River, tributaries of the Abaeté and Indaiá rivers, respectively. Thus, this species is endemic to the western portion of the upper São Francisco River basin, being sympatric with

P. rivularis at both sites (

Figure 1).

Etymology. The specific epithet honors Terezinha Aparecida Rodrigues (1947–2015), the late grandmother of the first author of this work, who was also honored in the dedication of the doctoral thesis that served as the basis for this article. A genitive name.

Remarks. Here, we define

P. terezinhae sp. nov. as only the M2 individuals of

P. rivularis sensu lato found west of the São Francisco River (

Figure 4, green clade, Lage and Funchal specimens).

P. terezinhae is extremely closely related to its counterpart from the eastern portion of the upper São Francisco River (

P. santae), both from morphological and karyotypic perspectives, presenting 2n = 50 chromosomes with the same number of metacentric and subtelocentric chromosomes as

P. santae (8 chromosomes of each morphology). Regarding the number of submetacentric and acrocentric chromosomes, the variation observed among specimens from the two sampled localities is even greater than that observed between them and P. santae: 24 submetacentric and 10 acrocentric chromosomes in specimens from the Lage stream, 20 submetacentric and 14 acrocentric chromosomes in the Funchal River, and 22 submetacentric and 12 acrocentric chromosomes in

P. santae from the confluence of the Mascates and Bocaina rivers, tributaries of the Cipó River (

Figure 3).

The main evidence supporting the proposal of a new species for this OTU is the lack of monophyly between these specimens and their counterparts from the eastern São Francisco River in any of the phylogenetic reconstructions performed (

Figure 4), as well as morphometric differences indicating a comparatively smaller cranial region than in

P. santae, a pattern that is reflected in our Random Forest analysis, in which most specimens were correctly classified according to orbit–opercle distance (

Figure 5).

New species: Psalidodon velhochico sp. nov.

Link to zoobank: Registration in zoobank will be carried out after the manuscript is accepted.

Holotype. LaGEEvo-28 (Voucher: LaGEEvo-5079). 77.0mm SL, female, upper part of Rasga Canga waterfall, São Francisco river drainage, Serra da Canastra National Park, Minas Gerais state, Brazil, 20°10'39.13" S 46°33'33.68" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, T. da S. Ramos, J. Godoy, S. S. N. Pereira, 29 Jul 2023.

Paratypes. All specimens are from the Serra da Canastra National Park, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco river basin: LaGEEvo-50, 15 specimens, standard length 49–89 mm, Serra da Canastra National Park – MG, upper part of Rasga Canga waterfall, 20°10′39.13″ S 46°33′33.68″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, T. da S. Ramos, J. Godoy, S. S. N. Pereira, 29 Jul 2023, collected with the holotype. LaGEEvo-53, 23 specimens, standard length 50–93 mm, Serra da Canastra National Park – MG, lower part of Rasga Canga waterfall, 20°10′39.13″ S 46°33′33.68″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, T. da S. Ramos, J. Godoy, S. S. N. Pereira, 29 Jul 2023.

Non-type material. All specimens are from the Serra da Canastra National Park, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco river basin: LaGEEvo-51, 34 specimens, standard length 43–83 mm, Serra da Canastra National Park – MG, Casca d’Anta waterfall, 20°18′2.24″ S 46°31′18.99″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, T. da S. Ramos, J. Godoy, S. S. N. Pereira, 28 Jul 2023. LaGEEvo-52, 34 specimens, standard length 40–81 mm, Serra da Canastra National Park – MG, historical source of the São Francisco River, 20°14′4.79″ S 46°26′29.38″ W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, T. da S. Ramos, J. Godoy, S. S. N. Pereira, 28 Jul 2023.

Diagnosis. Psalidodon velhochico sp. nov. differs from the other species of Psalidodon as follows: from P. alleni, P. argentum, P. balbus, P. bifasciatus, P. biotae, P. bockmanni, P. chico, P. correntinus, P. dissensus, P. dissimilis, P. eigenmanniorum, P. erytropterus, P. fasciatus, P. gymnodontus, P. gymnogenys, P. henseli, P. hermosus, P. ita, P. jequitinhonhae, P. marionae, P. minor, P. ojiara, P. parahybae, P. pelegrini, P. powelli, P. puka, P. pynandi, P. rutilus, P. saguazu, P. schubarti, P. troya, P. vermilion and P. xiru by having a robust head, with the snout profile up to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “U”-shaped contour in lateral view (vs. compressed head, with the snout profile up to the vertical posterior to the orbit forming a horizontal “V”-shaped contour). It differs from P. anisitsi, P. crenuchoides, P. kalunga and P. xavante by having 16–19 branched anal-fin rays (vs. 21–25 in P. anisitsi, 11–14 in P. crenuchoides, 13–14 in P. kalunga and 23–26 in P. xavante); from P. brachypterygium, P. cremnobates and P. goyanensis by its predorsal length (47.6%–51.4% vs. 51.2%–58.2% in P. brachypterygium, 51.1%–57.4% in P. cremnobates and 51.7%–58% in P. goyanensis); from P. endy and P. pampa by its smaller body depth (25.93%–34.78% vs. 36.6%–42.2% in P. endy and 36.9%–42.2% in P. pampa); from P. hamatus, P. leonidas, P. pessalii, P. tumbayaensis and P. uberaba by the scattered chromatophore pattern on the anterior body region below the lateral line (vs. reticulated pattern); from P. laticeps, P. scabripinnis and P. serratus by having a vertically elongated humeral spot (vs. horizontally elongated humeral spot with a vertical projection on its anterior portion, giving it a “p”-shaped outline); and from P. paranae, P. rioparanaibanus, P. togoi, P. uaiso and P. varzeae by having a variable lateral line (vs. always complete in P. paranae, P. rioparanaibanus and P. varzeae; and always incomplete in P. togoi and P. uaiso).

P. velhochico also differs from all other OTUs within P. rivularis sensu lato by having a scattered chromatophore pattern on the anterior body below the lateral line (vs. reticulated pattern). Additionally, it differs from P. rivularis sensu stricto by having 2n = 50 chromosomes (vs. 2n = 46) and a relatively greater orbit–opercular distance (13.80–17.25% vs. 9.35–13.11%), and from P. santae, P. terezinhae sp. nov. and P. paiva sp. nov. by having 37–39 scales along the lateral series (vs. 33–36).

Description. Morphometric data are available in

Table 8. Body compressed, greatest body depth generally located vertically between the origin and the end of the pectoral fin. Dorsal profile of the head slightly convex between the tip of the upper lip and the vertical anterior to the nostril; continuously convex from this point to the supraoccipital process. Profile convex from the supraoccipital process to the base of the last dorsal-fin ray; slightly convex from the dorsal to the adipose fin, and slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the upper caudal-fin ray. Ventral profile from the tip of the snout to the vertical through the end of the maxilla slightly convex, and from this point to the base of the first anal-fin ray markedly convex; anal-fin base straight; and slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the lower caudal-fin ray.

Terminal mouth, with lower jaw slightly projecting beyond the upper jaw. Maxilla extending posteriorly beyond the vertical through the anterior margin of the orbit.

Dorsal fin with ii+9 rays, the first unbranched ray about half the length of the second. Pectoral fin with i+12–14 rays, usually i+12-13 (f = 86.49%), its origin close to the vertical through the middle of the opercle, when adpressed to the body it never reaches the pelvic fin. Pelvic fin with i+7 rays, its origin anterior to the vertical through the last dorsal fin ray, when adpressed to the body it never reaches the anal fin. Anal fin with iv+15–20 rays, usually iv+17–18 (f = 72.73%). Caudal fin forked with i+17+i rays and lobes of similar size. Adipose fin present.

Cycloid scales, circuli absent on posterior margin, with 7–18 radii, usually more numerous in larger individuals. Lateral line variable, complete, incomplete, or interrupted, usually complete (f = 66.04%). Lateral series with 37–39 scales, usually 37–38 (f = 77.36%). Perforated scales along lateral series with 26-39 scales, usually 37-38 (f = 59.43%). Transverse series with 5–6 scales above the lateral line and 4–5 below, usually 5 above (f = 56.07%) and 5 below (f = 91.51%). Predorsal series with 11–13 scales, usually 12-13 (f = 89.74%). Scales around caudal peduncle 12–14, well-distributed frequency. Scales at the base of the anal fin 3–7, usually 4–5 (f = 55.56%).

Color in alcohol. Dorsal region of the body, head, and tip of the snout dark brown. Lateral region of the body is yellowish-brown or dark brown due to the large number of chromatophores scattered across the scales. Ventral region of the body yellowish-brown. Infraorbital and opercular regions yellowish-brown, with dark chromatophore spots on the opercle and infraorbitals around the orbit, sometimes more discreet in some individuals. Dispersed chromatophore pattern (not restricted to the posterior margin of the scales) in the anterior region of the body below the lateral line. Dispersed chromatophore pattern between the lateral line and the base of the anal fin. Conspicuous humeral spot extending 3–4 scales above the lateral line and 1–2 scales below, with the upper margin slightly wider than the lower margin. In some individuals, a second diffuse humeral spot can be observed, often difficult to distinguish due to its fusion with the lateral stripe and the darker body coloration in this species. Lateral stripe extending from the second humeral spot to the median rays of the caudal fin, becoming progressively thicker toward the caudal peduncle, where it expands dorsoventrally forming a distinct blotch at the margin of the caudal peduncle. Rayed fins hyaline, generally with few chromatophores along the margin of the rays. Adipose fin hyaline with a dispersed chromatophore pattern.

Color in life. Dorsal and lateral regions of the body, head, and upper maxilla dark, with a brownish-green hue extending from the dorsum to the region below the lateral line. Lower maxilla yellowish. First humeral spot dark, distinct, and vertically elongated. Area surrounding the lateral stripe with golden reflections posteriorly and greenish reflections anteriorly. Ventral region of the head and infraorbitals ranging from whitish to yellowish tones. Ventral region of the body white with yellowish reflections. Pectoral, pelvic, and anal fins intensely reddish. Dorsal and adipose fins range from yellowish to intensely reddish. Caudal fin with broad reddish and yellowish margins surrounding the dark lateral stripe.

Distribution. P. velhochico was collected in only three localities, all tributaries of the headwaters of the São Francisco River within Serra da Canastra National Park: the historical headwater of the São Francisco River, Rasga Canga waterfall (upper and lower sections), and Casca d’Anta waterfall (upper section) (

Figure 1).

Etymology. The specific epithet velhochico is used as a noun in apposition and refers to the popular nickname of the São Francisco River in Brazil, affectionately called “Velho Chico” (“Old Chico”) by Brazilians.

Remarks. Here, we define

P. velhochico sp. nov. as only the M3 individuals of

P. rivularis sensu lato (

Figure 4, yellow clade).

P. velhochico sp. nov. is clearly a distinct species from the other OTUs within

P. rivularis sensu lato, supported by all sources of data used in this study, and it is also the only one not showing sympatry with any of the others. In addition to the previously mentioned chromatophore pattern on the anterior body region, this OTU has 2n = 50 chromosomes (vs. 2n = 46 in

P. rivularis), with a markedly distinct karyotypic formula: 10 metacentric chromosomes (vs. 8 in the other OTUs), 18 submetacentric chromosomes (vs. 20 or more), 6 subtelocentric chromosomes (vs. 8–10), and 16 acrocentric chromosomes (vs. 14 or fewer). Some specimens also bear a distinctive large metacentric supernumerary chromosome, bigger than any other chromosome in the karyotype, which has otherwise been observed only in

P. paiva sp. nov.

From a molecular perspective, this OTU is phylogenetically close to P. rioparanaibanus and P. aff. paranae, forming a well-supported clade herein referred to as the “Paranaíba–Canastra” clade. This relationship is also reflected in morphological similarities, since both species exhibit a dispersed chromatophore pattern on the anterior body region below the lateral line. P. velhochico can be distinguished from P. rioparanaibanus by having 37–39 scales along the longitudinal series (vs. 34–36), and by lacking the dorsal pattern of alternating silvery and dark scales that characterizes P. rioparanaibanus. Furthermore, as in the other species within P. rivularis sensu lato, the lateral line in P. velhochico is variable (vs. complete in the remaining species of the “Paranaíba–Canastra” clade).

New species: Psalidodon paiva sp. nov.

Link to zoobank: Registration in zoobank will be carried out after the manuscript is accepted.

Holotype. LaGEEvo-29 (Voucher: LaGEEvo-2072). 62.0mm SL, male, Bonito Stream, Borrachudo river drainage, municipality of Tiros, Minas Gerais state, Brazil, 18°48'44.7" S 45°45'52.2" W, P. Penteado, Denis, Gabriel, Rafael, 20 Jul 2010.

Paratypes. All specimens are from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco River Basin. Borrachudo River Sub-basin: LaGEEvo-39, 5 specimens, standard length: 52 mm – 77 mm, municipality of Tiros – MG, Bonito Stream, 18°48'44.7" S 45°45'52.2" W, P. Penteado, Denis, Gabriel, Rafael, 20 Jul 2010, collected with the holotype. Abaeté River Sub-basin: LaGGEvo-55, 10 specimens, standard length: 31.5 mm – 44 mm, municipality of Rio Paranaíba – MG, lagoon of the Abaeté Dam, 19°12'35.69" S 46°6'33.79" W, I. H. R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, M. A. da Silva, 07 Jul 2017.

Non-type material. All specimens are from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. São Francisco River Basin. Abaeté River Sub-basin: LaGGEvo-54, 10 specimens, standard length: 42 mm – 72 mm, municipality of Rio Paranaíba – MG, lagoon of the Abaeté Dam, 19°12'35.69" S 46°6'33.79" W, W. Lopes-Silva, C. H. M. Fernandes, M. A. da Silva, A. C. M. Fernandes, 17 Jul 2012. LaGEEvo-57, 4 specimens, standard length: 57.5 mm – 67.5 mm, municipality of Tiros – MG, Tiros Stream, 18°56'34.08" S 45°56'18.20" W, 2010–2012. Paracatu River Sub-basin: LaGEEvo-76, 9 specimens, standard length: 37 mm – 45 mm, municipality of Presidente Olegário – MG, Crico Stream, 18°18'44.36" S 46°5'44.46" W, I. B. da Silva, M. L. C. B. de Campos, V. Augusto, S. V. Resende, 06 Apr 2019.

Diagnosis. With respect to the other species of Psalidodon, the diagnosis of Psalidodon paiva sp. nov. is the same as that of P. santae. Among the other species of P. rivularis sensu lato, P. paiva differs from P. rivularis sensu stricto by having 33–36 scales along the longitudinal series (vs. 37 or more) and 2n = 50 chromosomes (vs. 2n = 46); it differs from Psalidodon velhochico sp. nov. by having a reticulated pattern of chromatophores on the anterior body region below the lateral line (vs. dispersed pattern) and 33–36 scales along the longitudinal series (vs. 37 or more); it differs from Psalidodon terezinhae sp. nov. by having the greatest body depth usually at the vertical through the middle to the tip of the pectoral fin (vs. at the origin of the pelvic fin), smaller body depth (28.64%–32.66% vs. 33.97%–38.90%), shorter anal-fin base length (15.51%–21.64% vs. 22.48%–29.16%), and greater orbit–opercle distance (12.24%–14.52% vs. 8.60%–11.00%). Although we did not find any discrete character that distinguishes P. paiva sp. nov. from P. santae, both species can be differentiated by overlapping but statistically distinct morphometric characters: body depth (28.64%–32.66%, mean 30.90% in P. paiva vs. 31.15%–38.58%, mean 34.75% in P. santae) and anal-fin base length (15.51%–21.64%, mean 19.34% in P. paiva vs. 20.57%–28.45%, mean 24.89% in P. santae). In addition, P. paiva sp. nov. has the greatest body depth at the vertical through the middle to the tip of the pectoral fin (vs. usually at the vertical through the origin of the pelvic fin in P. santae).

Description. Morphometric data are available in

Table 8. Body compressed, greatest body depth usually located vertically between the middle and the tip of the pectoral fin. Dorsal profile of head slightly convex between the tip of the upper lip and the vertical through the anterior nostril; slightly convex, straight, or slightly concave from this point to the supraoccipital process. Dorsal profile from the supraoccipital process to the base of the last dorsal-fin ray convex; slightly convex from the dorsal to the adipose fin, and slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the upper caudal-fin ray. Ventral profile from tip of snout to base of pelvic fin convex; from pelvic fin to base of first anal-fin ray continuously convex or straight; base of anal fin straight; and slightly concave between the adipose fin and the base of the lower caudal-fin ray.

Mouth terminal, lower jaw slightly projecting beyond upper jaw. Posterior end of maxilla extending beyond vertical through anterior orbital margin.

Dorsal fin with ii+9 rays, first unbranched ray half the length of the second. Pectoral fin with i+12–14 rays, usually i+13 (f = 51.72%), origin close to vertical through posterior end of opercle, never reaching pelvic fin in larger individuals when adpressed. Pelvic fin with i+7 rays, origin anterior to vertical through last dorsal-fin ray, when adpressed to body, never reaching anal fin in larger individuals. Anal fin with iv+14–17 rays, usually iv+15–16 (f = 77.42%). Caudal fin forked with i+17+i rays, lobes of similar size. Adipose fin present.

Scales cycloid, posterior margin without circuli, 4–19 radii on scales, generally more numerous in larger individuals. Lateral line variable, complete, incomplete, or interrupted, usually complete (f = 58.33%); 33–36 scales in lateral series, usually 34–35/35-36 (f = 66.67%). Perforated scales along lateral series with 24-36 scales, usually 34-35 (f = 57.14%). Transverse scale series with 5–6 scales above lateral line and 4–5 below, usually 5 above (f = 57.89%) and 5 below (f = 57.89%). Predorsal scale series with 13–15 scales, usually 14 (f = 60.00%). Circumpeduncular scale series with 12-14 scales, usually 14 (f = 56.67%). Anal-fin base scale series with 3–8 scales, usually 3-4 (f = 65.52%).

Color in alcohol. Dorsal region of body, head, and snout tip dark brown. Lateral region of body yellowish-brown or slightly silvery anteriorly. Ventral region of body yellowish-brown. Infraorbital and opercular regions silvery, with a faint dark blotch of chromatophores on opercle, sometimes absent in some individuals. Reticulated pattern of chromatophores (restricted to posterior margin of scales) present on anterior portion of body below lateral line. Dispersed chromatophore pattern between lateral line and anal-fin base. Conspicuous humeral blotch extending 2–3 scales above and 1–2 scales below lateral line, upper margin broader than lower. Clear area posterior to humeral blotch with few chromatophores in a dispersed pattern. Lateral stripe that begins slightly after the humeral spot and extends to the median caudal-fin rays, silvery anteriorly and becoming darker toward caudal peduncle, where it expands dorsoventrally to form a distinct blotch on caudal-peduncle margin. The most anterior portion of the dark lateral stripe resembles a second humeral spot but lacks a dorsoventral extension. Rayed fins hyaline, usually with few chromatophores along fin-ray margins. Adipose fin hyaline with scattered chromatophores.

Distribution. Psalidodon paiva sp. nov. was collected in tributaries of the Abaeté, Borrachudo, and Paracatu rivers in the western portion of the São Francisco River basin, thus occurring in the Upper and Middle São Francisco drainages. In three of the four localities where it was collected (Bonito stream, Tiros stream, and Crico stream), this species is sympatric with

P. rivularis sensu stricto, whereas in the fourth locality (Abaeté Power Plant Dam Lagoon) it is sympatric with

A. lacustris (

Figure 1).

Etymology. The specific epithet is used as a noun in apposition and honors the Paiva family, whose life, portrayed in the Brazilian Oscar-winning film “Ainda Estou Aqui” (2024), was profoundly affected by the imprisonment, disappearance, and execution of the family patriarch, Rubens Paiva, during the Brazilian military dictatorship.

Remarks. Here, we define

P. paiva sp. nov. as only the M4 individuals of

P. rivularis sensu lato (

Figure 4, light blue clade).

Psalidodon paiva sp. nov. resembles

P. santae and

P. terezinhae sp. nov. in meristic and morphological traits, however, its morphometric proportions are more like those of

P. rivularis and

P. velhochico sp. nov., particularly in having a lower body depth, as observed in PCA and Random Forest analyses (

Figure 3). From a cytogenetic perspective, this species has 2n = 50 + 0–1B chromosomes, differing from

P. rivularis sensu stricto (2n = 46 + 0–2Bs). This OTU can also be distinguished from

P. rivularis, P. santae, and

P. terezinhae by the higher number of subtelocentric chromosomes (10 vs. 8), in addition to some specimens bearing a large metacentric supernumerary chromosome, like

P. velhochico (vs. some specimens presenting a small acrocentric supernumerary chromosome with intercellular variation) (

Figure 3). From a molecular perspective, excluding the mitochondrial genome dataset, this species appears to be more closely related to the “

paranae–scabripinnis” group than to other OTUs of the

P. rivularis sensu lato group (

Figure 4).

Although we did not collect this species during the present study, it is well represented in the Ichthyological Collection of LaGEEvo UFV CRP, usually identified as “

P. rivularis 2n=50.” Prior to this study, this species already had a mitochondrial genome available in the NCBI nt database (MT428070.1), identified as the cytotype with 2n=50 chromosomes of

P. rivularis (LAGEEVO – 2614) by Pasa et al. [

21].

Comparative material examined. Astyanax lacustris: ZMUC P241329 (photograph), syntype of Tetragonopterus lacustris, 1 specimen, standard length: 51.12 mm, Lagoa Santa municipality – MG, 19°37’52’’ S 43°54’07’’ W, J. T. Reinhardt, 1850–1856. LaGEEvo-65, 2 specimens, standard length: 69–78.5 mm, municipality of Lagoa da Prata - MG, Retiro de Baixo stream, 20°0'15.75" S 45°30'42.13" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, R. A. S. Soares, L. da C. de Santos, 06 May 2023. LaGEEvo-66, 3 specimens, standard length: 69–79 mm, municipality of Augusto de Lima - MG, Teixeira stream, 17°58'58.53" S 44°4'26.566" W, V. G. de Miranda, Jul 2024. LaGEEvo-71, 12 specimens, standard length: 49–59 mm, municipality of Rio Paranaíba - MG, Abaeté Power Plant Dam lagoon, 19°12'35.69" S 46°6'33.79" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, P. M. de Assis, L. G. P. Pimentel, R. A. S. Soares, 10 Jan 2022.

Psalidodon fasciatus: ZMUC P241291 (photograph), syntype of Tetragonopterus cuvieri, 1 specimen, standard length: 86.5 mm, Lagoa Santa municipality - MG, 19°37’52’’ S 43°54’07’’ W, J. T. Reinhardt, 1850–1856. LaGEEvo-67, 1 specimen, standard length: 98 mm, municipality of Lagoa da Prata - MG, Retiro de Baixo stream, 20°0'15.75" S 45°30'42.13" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, R. A. S. Soares, L. da C. de Santos, 06 May 2023. LaGEEvo-68, 3 specimens, standard length: 68–83 mm, municipality of Augusto de Lima - MG, Teixeira stream, 17°58'58.53" S 44°4'26.566" W, V. G. de Miranda, Jul 2024. LaGEEvo-69, 7 specimens, standard length: 38.5–89 mm, Lagoa da Prata - MG, Santana river, 20°0'15.75" S 45°30'42.13" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, R. A. S. Soares, L. da C. de Santos, 06 May 2023. LaGEEvo-70, 1 specimen, standard length: 64 mm, Três Marias - MG, Vereda Grande river, 18°19'18.62" S 45°6'32.80" W, R. de M. Alves, R. R. Rocha, M. A. da Silva, S. V. Resende, 18 Apr 2017.

Psalidodon paranae: LaGEEvo-72, 7 specimens, standard length: 53.5–77.5 mm, Rio Paranaíba - MG, Lava-Pés stream, 19°11'41.22" S 46°15'7.32" W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, F. Sassi, T. Lunardi, R. Pereira, M. Trevisanuto, November 2015. LaGEEvo-73, 3 specimens, standard length: 77–83 mm, Rio Paranaíba - MG, Lava-Pés stream, 19°11'41.22" S 46°15'7.32" W, M. L. C. B. de Campos, F. Sassi, T. Lunardi, R. Pereira, M. Trevisanuto, November 2015.

Psalidodon rioparanaibanus: LaGEEvo-12, holotype of Psalidodon rioparanaibanus, 1 specimen, standard length: 84 mm, Rio Paranaíba - MG, Rita stream, 19°11'15.77" S 46°14'10.24" W, M. A. da Silva & I. B. da Silva, 21 Aug 2017. LaGEEvo-13, paratypes of Psalidodon rioparanaibanus, 8 of 15 specimens, standard length: 43–84 mm, Rio Paranaíba - MG, Rita stream, 19°11'15.77" S 46°14'10.24" W, I.H.R. Oliveira, I. B. da Silva, R. L. Oliveira, G. Leles, T. Castaño, 23 Sep 2018. LaGEEvo-14, paratypes of Psalidodon rioparanaibanus, 4 specimens, standard length: 40–84 mm, Rio Paranaíba - MG, Rita stream, 19°11'15.77" S 46°14'10.24" W, M. A. da Silva & I. B. da Silva, 21 Aug 2017.