Submitted:

27 October 2025

Posted:

29 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

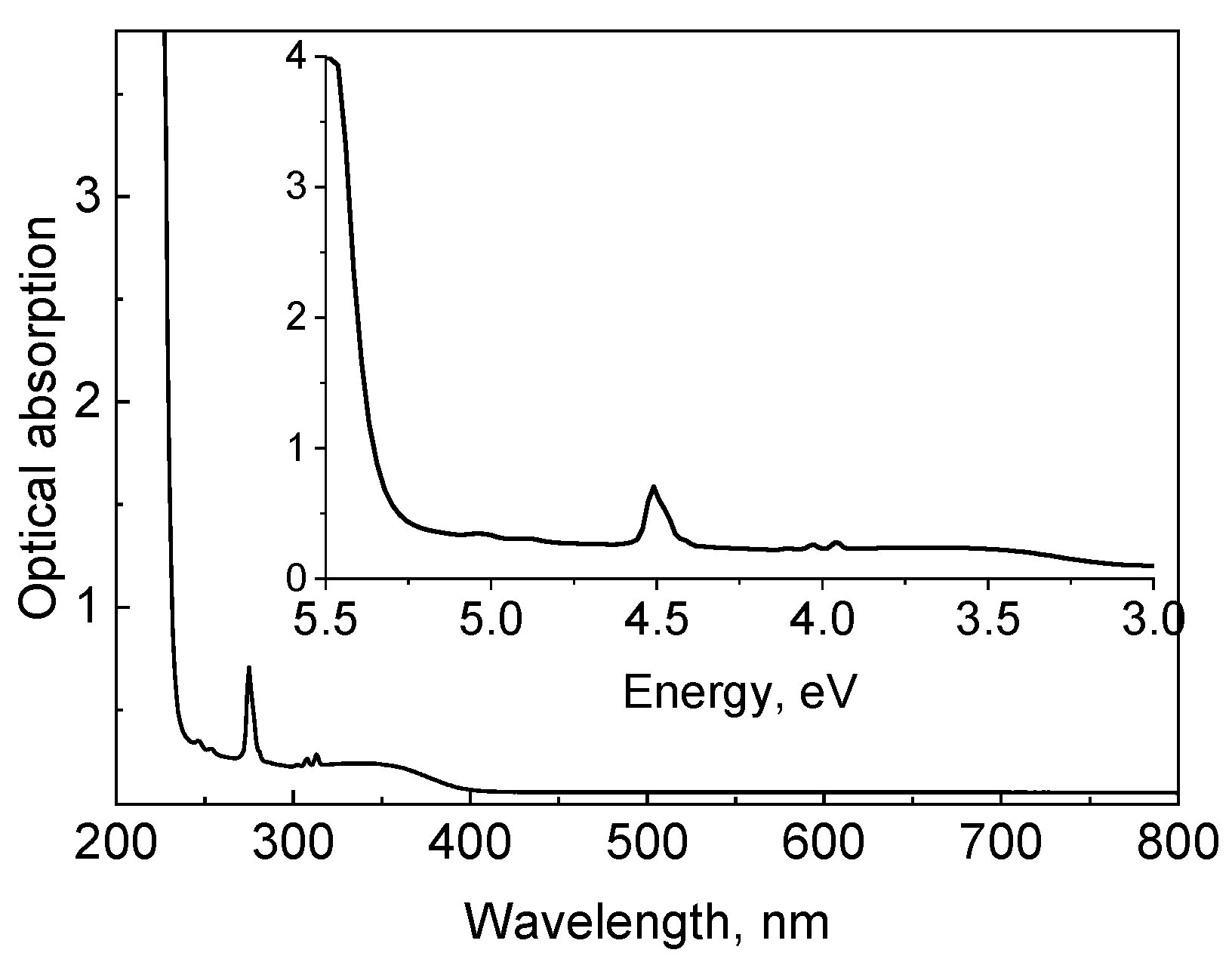

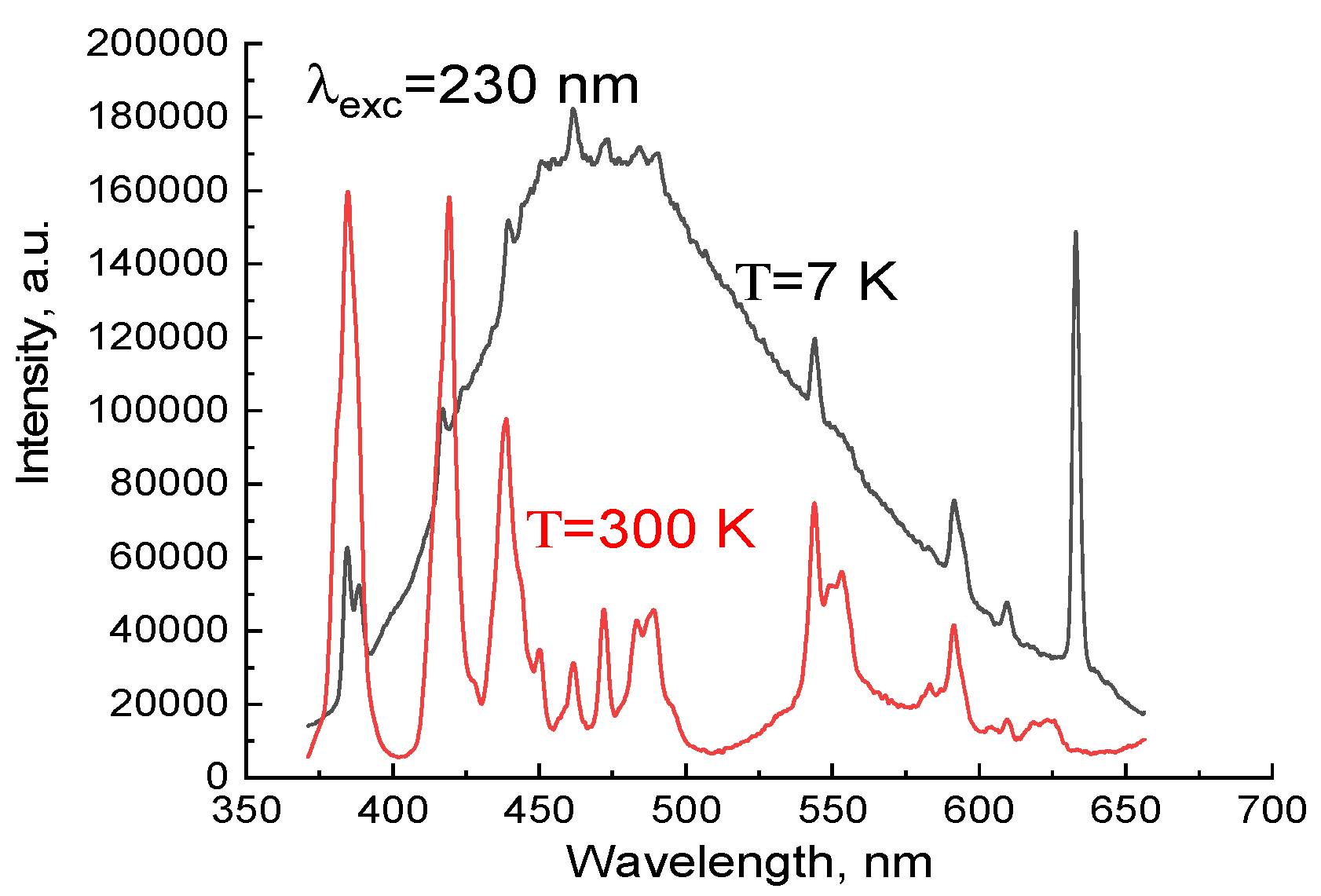

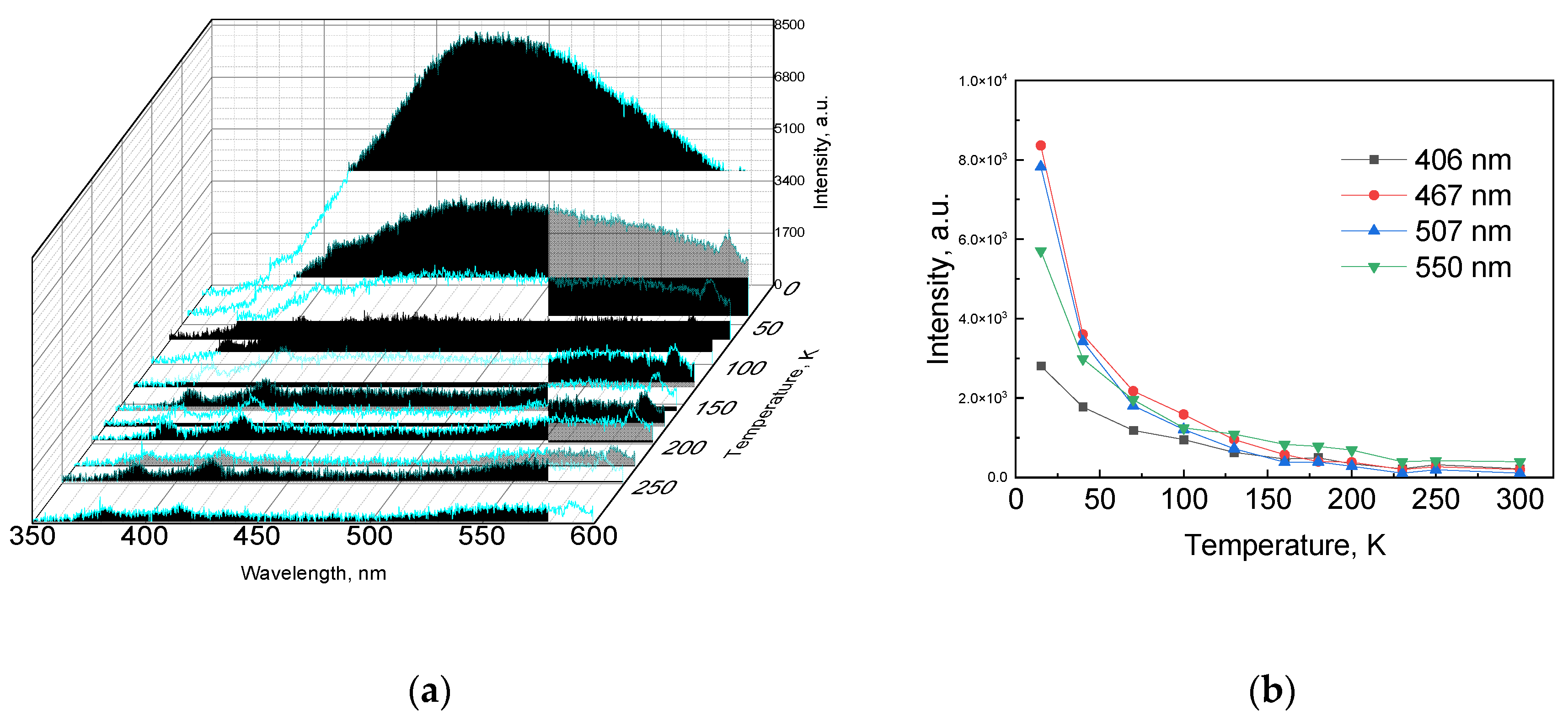

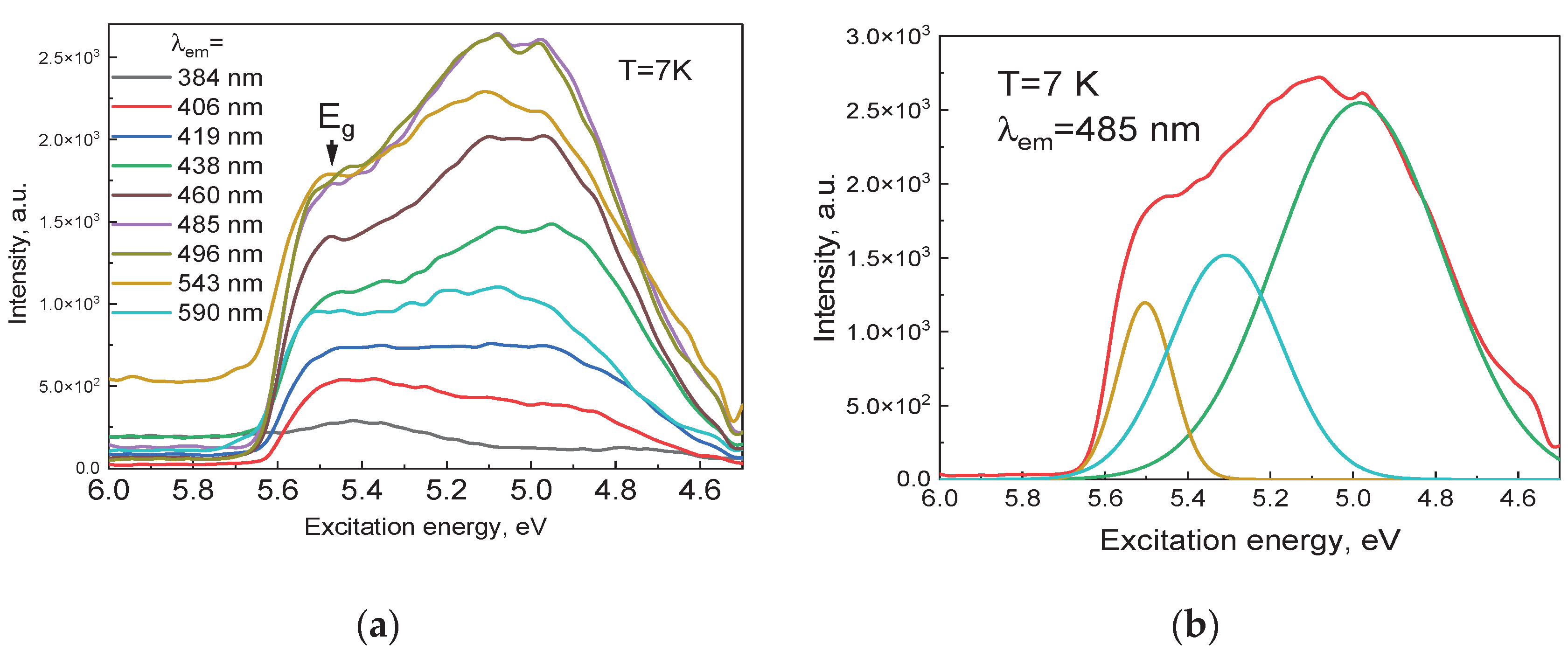

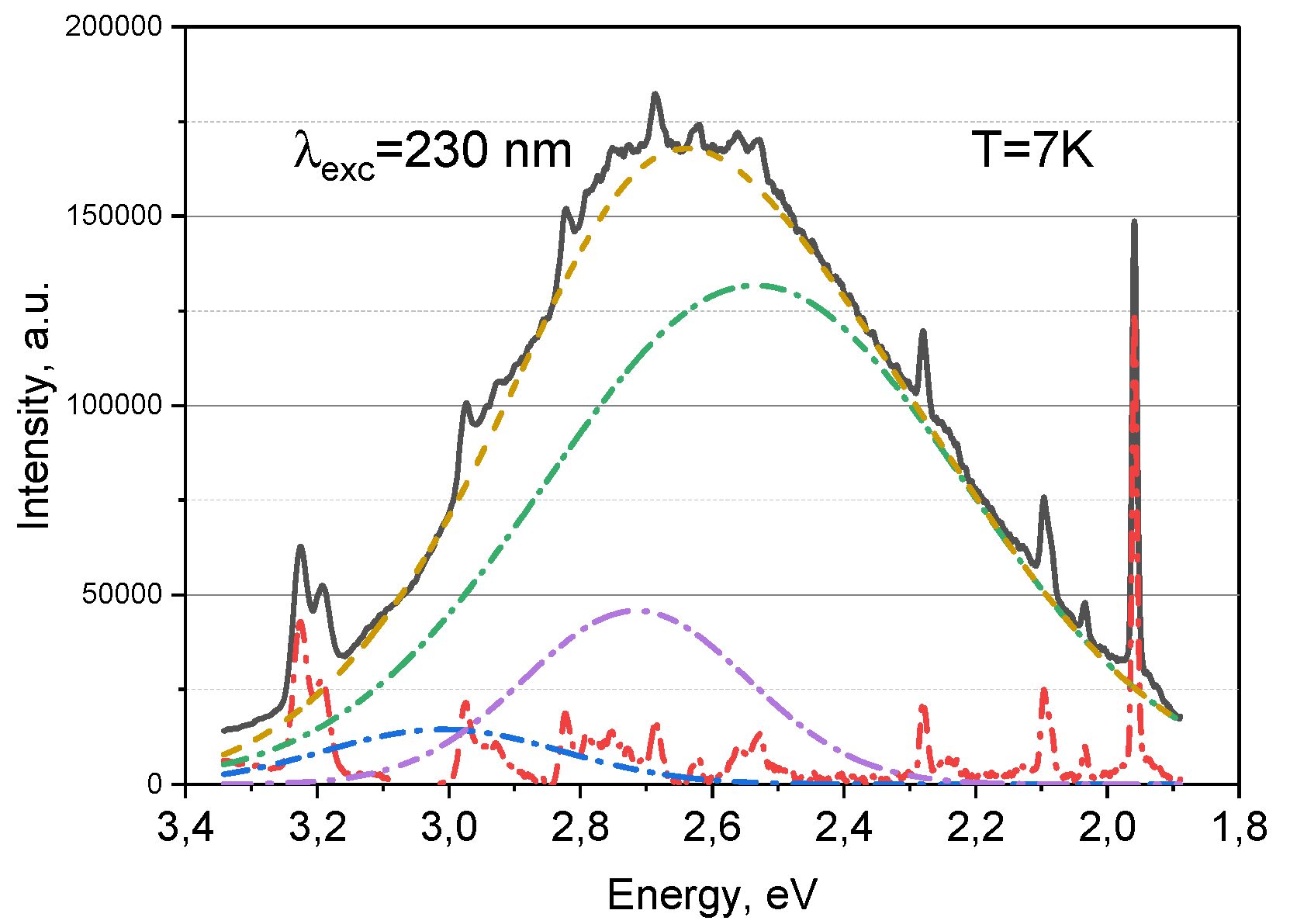

The intrinsic defect-related luminescence of as-grown Gd3Ga5O12 (GGG) single crystals was investigated using synchrotron excitation in the vacuum-ultraviolet region. The photoluminescence spectrum at 7 K exhibits a broad emission band centered near ~2.5 eV (≈500 nm), accompanied by narrow 4f–4f transitions of uncontrolled Tb3+ impurity ions. Gaussian decomposition of the broad band reveals three components at approximately 3.05, 2.70, and 2.50 eV, attributed to self-trapped excitons (STE), antisite-associated recombination, and F/F+-type oxygen-vacancy centers, respectively. Temperature-dependent photoluminescence measurements show that the defect-related luminescence is governed by two thermally activated nonradiative channels with activation energies of ~5–8 meV and 42–56 meV. The shallow channel dominates at 20–50 K, while the main quenching occurs between 100 and 150 K, leading to nearly complete suppression of the broad emission at room temperature. The present results therefore characterize the emission behavior of intrinsic, shallow defect centers in as-grown GGG and contribute to understanding defect recombination pathways that are critical for optimizing garnet-based scintillation and photonic materials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Kane, D.F.; Sadagopan, V.; Geiss, E.A.; Mandel, E. Crystal Growth and Characterization of Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1973, 120, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.-N.; Ching, W.Y.; Brickeen, B.K. Electronic structure and bonding in garnet crystals Electronic structure and bonding in garnet crystals Gd3Sc2Ga3O12, Gd3Sc2Al3O12, and Gd3Ga3O12 compared to Y3Al3O12. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 61, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, K.; Haneef, H.F.; Collins, R.W.; Podraza, N.J. Optical Properties of Single-Crystal Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ from the Infrared to the Ultraviolet. Phys. Status Solidi B 2015, 252, 2191–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Li, T.; Xu, J. Growth of epitaxial substrate Gd3Ga3O12 (GGG) single crystal through pure GGG phase polycrystalline material. J. Cryst. Growth 2002, 237-239, 720–724. [CrossRef]

- Syvorotka, I.I.; Sugak, D.Y.; Wierzbicka, A.; Wittlin, A.; Przybylińska, H.; Barzowska, J.; Barcz, A.J.; Berkowski, M.; Domagała, J.Z.; Mahlik, S.; et al. Optical Properties of Pure and Ce³⁺-Doped Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Crystals and Epitaxial Layers. J. Lumin. 2015, 164, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailov, M.M.; Neshchimenko, V.V.; Shavlyuk, V.V. Binding-Type Effects in LED Phosphor GGG:Ce³⁺. Opt. Mater. 2014, 38, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirumalaisamy, T.K.; Saravanakumar, S.; Butkute, S.; Kareiva, A.; Saravanan, R. Structure and Charge Density of Ce-Doped GGG. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 1920–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Ma, E.; Tu, C. Spectroscopy of Highly Doped Er³⁺:GGG and Er³⁺/Pr³⁺:GGG. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 215406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; You, Z.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z.; Tu, C. Optical Properties of Dy³⁺ in GGG. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 075402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkute, S.; Zabiliute, A.; Skaudzius, R.; Zukauskas, A.; Kareiva, A. Sol–Gel Synthesis and Substitution in Ga-Garnets. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2015, 76, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Meng, B.; Rao, X.; Zhou, Y. Varied-Depth Nanoscratch on GGG. Mater. Des. 2017, 125, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, F.; Huang, H. Nanoindentation of GGG Single Crystal. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 3661–3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Wang, X.; Rao, X. Crack-Free Grinding of GGG. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 279, 116577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugak, D.; Syvorotka, I.I.; Yakhnevych, U.; Buryy, O.; Vakiv, M.; Ubizskii, S.; Włodarczyk, D.; Зhydachevskyy, Ya.; Pieniążek, A.; Jakiela, R.; Suchocki, A. Investigation of Co Ions Diffusion in Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Single Crystals. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 133(4), 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshmi, C.P.; Ramesh, A.R.; Suresh, A.; Jaiswal-Nagar, D. Magnetic, magnetocaloric and optical properties of nano Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂garnet synthesized by citrate sol-gel method. Int. J. Nano Dimens. 2025, 16, 190–201. [Google Scholar]

- Luchechko, A.; Kostyk, L.; Varvarenko, S.; Tsvetkova, O.; Kravets, O. Green-Emitting Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂:Tb³⁺ Nanoparticles Phosphor: Synthesis, Structure, and Luminescence. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanić, B.; Bettinelli, M.; Radenković, B.; Despotović-Zrakić, M.; Bogdanović, Z. Optical spectroscopy of nanocrystalline Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ doped with Eu3+ and high pressures. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2012, 132, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillard, A.; Douissard, P.-A.; Loiko, P.; Martin, T.; Mathieu, E.; Camy, P. Terbium-doped gadolinium garnet thin films grown by liquid phase epitaxy for scintillation detectors. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 20560–20568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollesen, L.; Douissard, P.-A.; Pauwels, K.; Baillard, A.; Loiko, P.; Brasse, G.; Mathieu, J.; Simeth, S.J.; Kratz, M.; Dujardin, C.; et al. Microstructured growth by liquid phase epitaxy of scintillating Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂(GGG) doped with Eu3+. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xu, J.; Murakami, H.; Yamahara, H.; Seki, M.; Tabata, H.; Tonouchi, M. Terahertz Time-Domain Spectroscopy of Substituted Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. Condens. Matter 2025, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yousaf, M.; Ahmed, J.; Bibi, B.; Noor, A.; Alhokbany, N.; Sajid, M.; Nazar, A.; Shah, M.A.K.Y.; Guo, X.; Ding, X.; Mushtaq, N.; Lu, Y. Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂: A wide bandgap semiconductor electrolyte for ceramic fuel cells, effective at temperatures below 500 C. J. Rare Earths 2025, 43, 2248–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzbieciak-Piecka, K.; Sójka, M.; Tian, F.; Li, J.; Zych, E.; Marciniak, L. The comparison of the thermometric performance of optical ceramics, microcrystals and nanocrystals of Cr3+-doped Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ garnets. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 963, 171284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, N.; Kodama, S.; Bartosiewicz, K.; Fujiwara, C.; Yanase, I.; Takeda, H. Modification of Photoluminescence Wavelength and Decay Constant of Cr:Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Substituted by Ca/Si Cation Pair. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 2024, 132(7), 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaura, M.; Zen, H.; Watanabe, S.; Masai, H.; Kamada, K.; Kim, K.J.; Ueda, J. Relationship between Ce³⁺ 5d₁ Level, Conduction-Band Bottom, and Shallow Electron Trap Level in Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂:Ce and Gd₃Al₁Ga₄O₁₂:Ce Crystals Studied via Pump–Probe Absorption Spectroscopy. Opt. Mater. X 2025, 25, 100398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrenko, O.A.; Balakrishnan, G.; Paul, D.McK.; Yethiraj, M.; McIntyre, G.J.; Wills, A.S. Field Induced Magnetic Order in the Frustrated Magnet Gadolinium Gallium Garnet. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2009, 145, 012026. [CrossRef]

- Deen, P.P.; Florea, O.; Lhotel, E.; Jacobsen, H. Updating the Phase Diagram of the Archetypal Frustrated Magnet Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂. Phys. Rev. B 2015, 91, 014419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackville Hamilton, A.C.; Lampronti, G.I.; Rowley, S.E.; Dutton, S.E. Enhancement of the Magnetocaloric Effect Driven by Changes in the Crystal Structure of Al-Doped GGG, Gd₃Ga₅−ₓAlₓO₁₂ (0 ≤ x ≤ 5). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2014, 26(11), 116001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, J.; Gao, L.; Ma, H.; Oimod, H.; Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Su, T.; Zhu, H.; Tegus, O.; Zhao, J. Influence of High-Pressure Heat Treatment on Magnetocaloric Effects and Magnetic Phase Transition in Single Crystal Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂. J. Rare Earths 2024, 42(11), 2112–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukalkin, Y.G.; Shtirts, V.R. Radiation Amorphization and Recovery of Crystal Structure in Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Single Crystals. Phys. Status Solidi A 1994, 144(1), 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mironova-Ulmane, N.; Sildos, I.; Vasil’chenko, E.; Chikvaidze, G.; Skvortsova, V.; Kareiva, A.; Muñoz-Santiuste, J.E.; Pareja, R.; Elsts, E.; Popov, A.I. Optical Absorption and Raman Studies of Neutron-Irradiated Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Single Crystals. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2018, 435, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potera, P.; Matkovskii, A.; Sugak, D.; Grigorjeva, L.; Millers, D.; Pankratov, V. Transient Color Centers in GGG Crystals. Radiat. Eff. Defects Solids 2002, 157(6–12), 709–713. [CrossRef]

- Potera, P.; Ubizskii, S.; Sugak, D.; Schwartz, K. Induced Absorption in Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Irradiated by High-Energy ²³⁵U Ions. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2010, 117, 181–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karipbayev, Z.T.; Kumarbekov, K.; Manika, I.; Dauletbekova, A.; Kozлoвskiy, A.L.; Sugak, D.; Ubizskii, S.B.; Akilbekov, A.; Suchikova, Y.; Popov, A.I. Optical, Structural, and Mechanical Properties of Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Single Crystals Irradiated with 84Kr⁺ Ions. Phys. Status Solidi B 2022, 259(8), 2100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meftah, A.; Costantini, J.M.; Khalfaoui, N.; Boudjadar, S.; Stoquert, J.P.; Studer, F.; Toulemonde, M. Experimental Determination of Track Cross-Section in Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ and Comparison to the Inelastic Thermal Spike Model Applied to Several Materials. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2005, 237(3–4), 563–574. [CrossRef]

- oulemonde, M.; Meftah, A.; Costantini, J.M.; Schwartz, K.; Trautmann, C. Out-of-Plane Swelling of Gadolinium Gallium Garnet Induced by Swift Heavy Ions. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1998, 146(1–4), 426–430. [CrossRef]

- Meftah, A.; Assmann, W.; Khalfaoui, N.; Stoquert, J.P.; Studer, F.; Toulemonde, M.; Trautmann, C.; Voss, K.-O. Electronic Sputtering of Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ and Y₃Fe₅O₁₂ Garnets: Yield, Stoichiometry and Comparison to Track Formation. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2011, 269(9), 955–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, J.-M.; et al. Swift Heavy Ion-Beam Induced Amorphization and Recrystallization of Yttrium Iron Garnet. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2015, 27, 496001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, J.-M.; Miro, S.; Lelong, G.; Guillaumet, M.; Toulemonde, M. Damage Induced in Garnets by Heavy-Ion Irradiations: A Study by Optical Spectroscopies. Philos. Mag. 2018, 98(4), 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, N.; Nellis, W.J.; Mashimo, T.; Ramzan, M.; Ahuja, R.; Kaewmaraya, T.; Kimura, T.; Knudson, M.; Miyanishi, K.; Sakawa, Y.; Sano, T.; Kodama, R. Dynamic Compression of Dense Oxide (Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂) from 0. 4 to 2.6 TPa: Universal Hugoniot of Fluid Metals. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanin, V.M.; Rodnyi, P.A.; Wieczorek, H.; Ronda, C.R. Electron Traps in Gd3Ga3Al2O12:Ce Garnets Doped with Rare-Earth Ions. Tech. Phys. Lett. 2017, 43, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisiecki, R.; Komar, J.; Macalik, B.; Strzęp, A.; Berkowski, M.; Ryba-Romanowski, W. Exploring the Impact of Structure-Sensitive Factors on Luminescence and Absorption of Trivalent Rare Earth Embedded in Disordered Crystal Structures of Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂–Gd₃Al₅O₁₂ and Lu₂SiO₅–Gd₂SiO₅ Solid Solution Crystals. Low Temp. Phys. 2023, 49, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aralbayeva, G.M.; Manika, I.; Karipbayev, Zh.; Suchikova, Y.; Kovachov, S.; Sugak, D.; Popov, A.I. Micromechanical Properties of Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ Crystals Irradiated with Swift Heavy Ions. J. Nano-Electron. Phys. 2023, 15(5), 05020. [CrossRef]

- Zorenko, Y.; Zorenko, T.; Voznyak, T.; Mandowski, A.; Xia, Q.; Batentschuk, M.; Friedrich, J. Luminescence of F⁺ and F centers in Al₂O₃-Y₂O₃ oxide compounds. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2010, 15, 012060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, V.; Laguta, V.V.; Maaroos, A.; Makhov, A.; Nikl, M.; Zazubovich, S. Luminescence of F⁺-type centers in undoped Lu₃Al₅O₁₂ single crystals. Phys. Status Solidi B 2011, 248, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varney, C.R.; Selim, F.A. Color centers in YAG. AIMS Mater. Sci. 2015, 2, 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Skuratov, V.A.; Buzanov, O.A.; Mololkin, A.A.; Kozlova, A.P.; Kotlov, A.; Popov, A.I.; Pankratov, V. Radiation effects in Gd₃(Al,Ga)₅O₁₂:Ce³⁺ single crystals induced by swift heavy ions. Opt. Mater. X 2022, 16, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, V.; Butikova, J.; Kotlov, A.; Popov, A.I.; Pankratov, V. Influence of swift heavy ions irradiation on optical and luminescence properties of Y₃Al₅O₁₂ single crystals. Opt. Mater. X 2024, 23, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.B.; Vanetsev, A.; Mändar, H.; Nagirnyi, V.; Chernenko, K.; Kirm, M. Investigation of Luminescence Properties of Hydrothermally Synthesized Pr³⁺ Doped BaLuF₅ Nanoparticles under Excitation by VUV Photons. Opt. Mater. 2024, 154, 115781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutyak, N.; Nagirnyi, V.; Romet, I.; Deyneko, D.; Spassky, D. Energy Transfer Processes in NASICON-Type Phosphates under Synchrotron Radiation Excitation. Symmetry 2023, 15, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spassky, D.; Voznyak-Levushkina, V.; Arapova, A.; Zadneprovski, B.; Chernenko, K.; Nagirnyi, V. Enhancement of Light Output in ScxY1−xPO4:Eu3+ Solid Solutions. Symmetry 2020, 12, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romet, I.; Tichy-Rács, É.; Lengyel, K.; Feldbach, E.; Kovács, L.; Corradi, G.; Chernenko, K.; Kirm, M.; Spassky, D.; Nagirnyi, V. Interconfigurational d–f Luminescence of Pr³⁺ Ions in Praseodymium Doped Li₆Y(BO₃)₃ Single Crystals. J. Luminescence 2024, 265, 120216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosiewicz, K.; Szysiak, A.; Tomala, R.; Gołębiewski, P.; Węglarz, H.; Nagirnyi, V.; Kirm, M.; Romet, I.; Buryi, M.; Jary, V.; et al. Energy-Transfer Processes in Nonstoichiometric and Stoichiometric Er3+, Ho3+, Nd3+, Pr3+, and Cr3+-Codoped Ce:YAG Transparent Ceramics: Toward High-Power and Warm-White Laser Diodes and LEDs. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2023, 20, 014047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundacker, S.; Pots, R. H.; Nepomnyashchikh, A.; Radzhabov, E.; Shendrik, R.; Omelkov, S.; Kirm, M.; Acerbi, F.; Capasso, M.; Paternoster, G.; Mazzi, A.; Gola, A.; Chen, J.; Auffray, E. Vacuum Ultraviolet Silicon Photomultipliers Applied to BaF₂ Cross Luminescence Detection for High Rate Ultrafast Timing Applications. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66 (11), 114002. [CrossRef]

- Saaring, J.; Feldbach, E.; Nagirnyi, V.; Omelkov, S.; Vanetsev, A.; Kirm, M. Ultrafast Radiative Relaxation Processes in Multication Cross Luminescence Materials. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2020, 67(6), 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smortsova, Y.; Chukova, O.; Kirm, M.; Nagirnyi, V.; Pankratov, V.; Kataev, A.; Kotlov, A. The P66 time-resolved VUV spectroscopy beamline at PETRA III storage ring of DESY. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2025, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriichuk, V.A.; Volzhenskaya, L.G.; Zakharko, Ya.M.; Zorenko, Yu.V. Influence of structure defects upon the luminescence and thermostimulated effects in Gd3Ga5O12 crystals. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 1987, 47, 902–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randoshkin, V.V.; Vasil’eva, N.V.; Kolobanov, V.N.; Mikhailin, V.V.; Petrovnin, N.N.; Spasskii, D.A.; Sysoev, N.N. Effect of Gd₂O₃ concentration in Bi-containing high-temperature solutions on the luminescence of epitaxial Gd₃Ga₅O₁₂ films. Inorg. Mater. 2009, 45, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Emission Band, (nm) | Excitation, (nm) | Possible Transitions |

| 382 | 230 | 5D3 → 7F6 |

| 420 | 230 | 5D3 → 7F5 |

| 440 | 230 | 5D3 → 7F4 |

| 474 | 230 | 5D4 → 7F6 |

| 543 | 230 | 5D4 → 7F5 |

| 583 | 230 | 5D4 → 7F4 |

| 630 | 230 | 5D4 → 7F3 |

| Λem, nm | B1 | E1, meV | B2 | E2, meV |

| 406 | 3,65 | 6 | 50,3 | 41,7 |

| 467 | 7.9 | 5.6 | 521 | 55.6 |

| 507 | 11.5 | 7.3 | 614.9 | 55.6 |

| 550 | 5,95 | 6,2 | 51,7 | 41,8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).