Submitted:

24 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Acquirement and Preprocessing

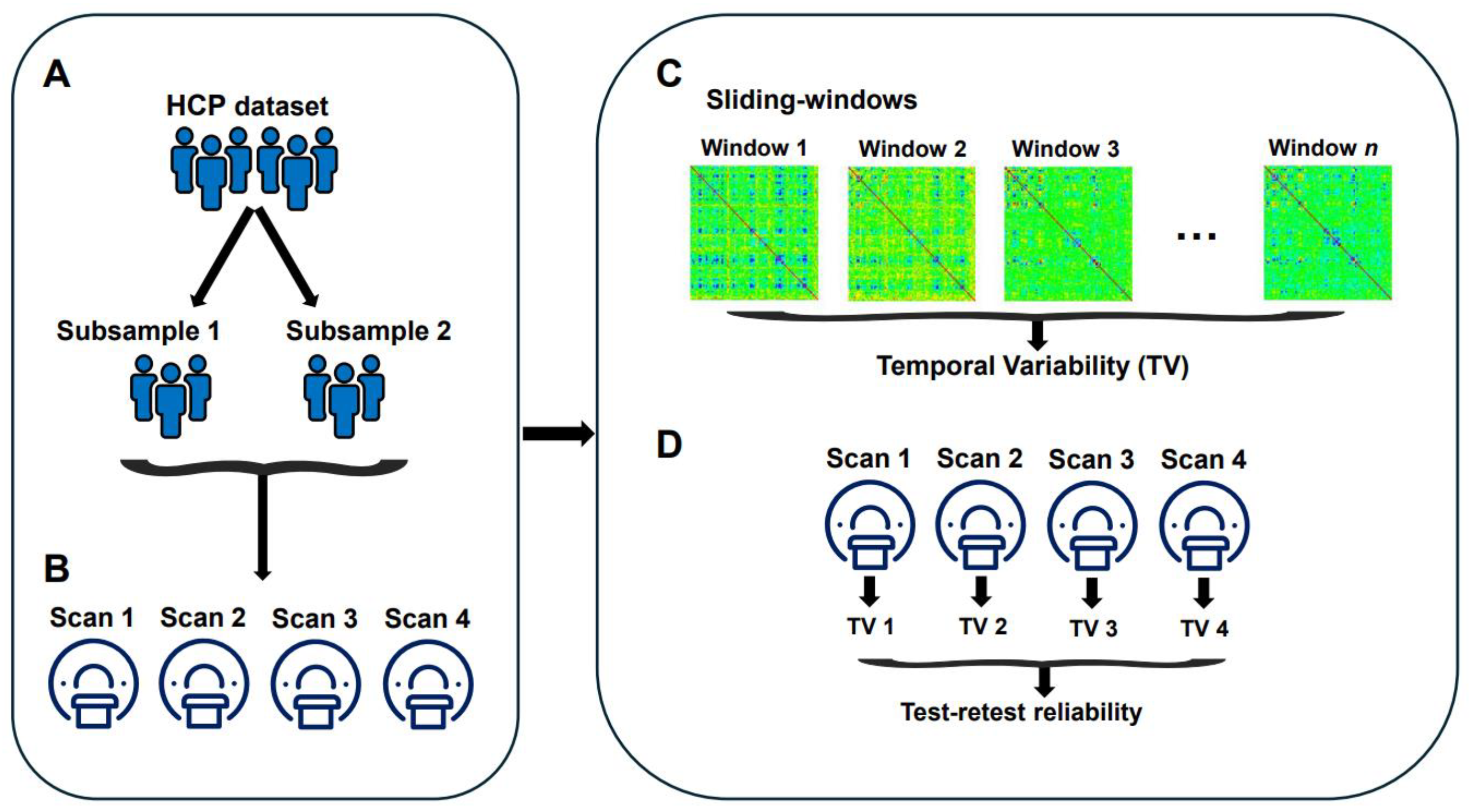

2.2. Constructing Dynamic Brain Networks

2.3. Temporal Variability

2.4. Test-Retest Reliability

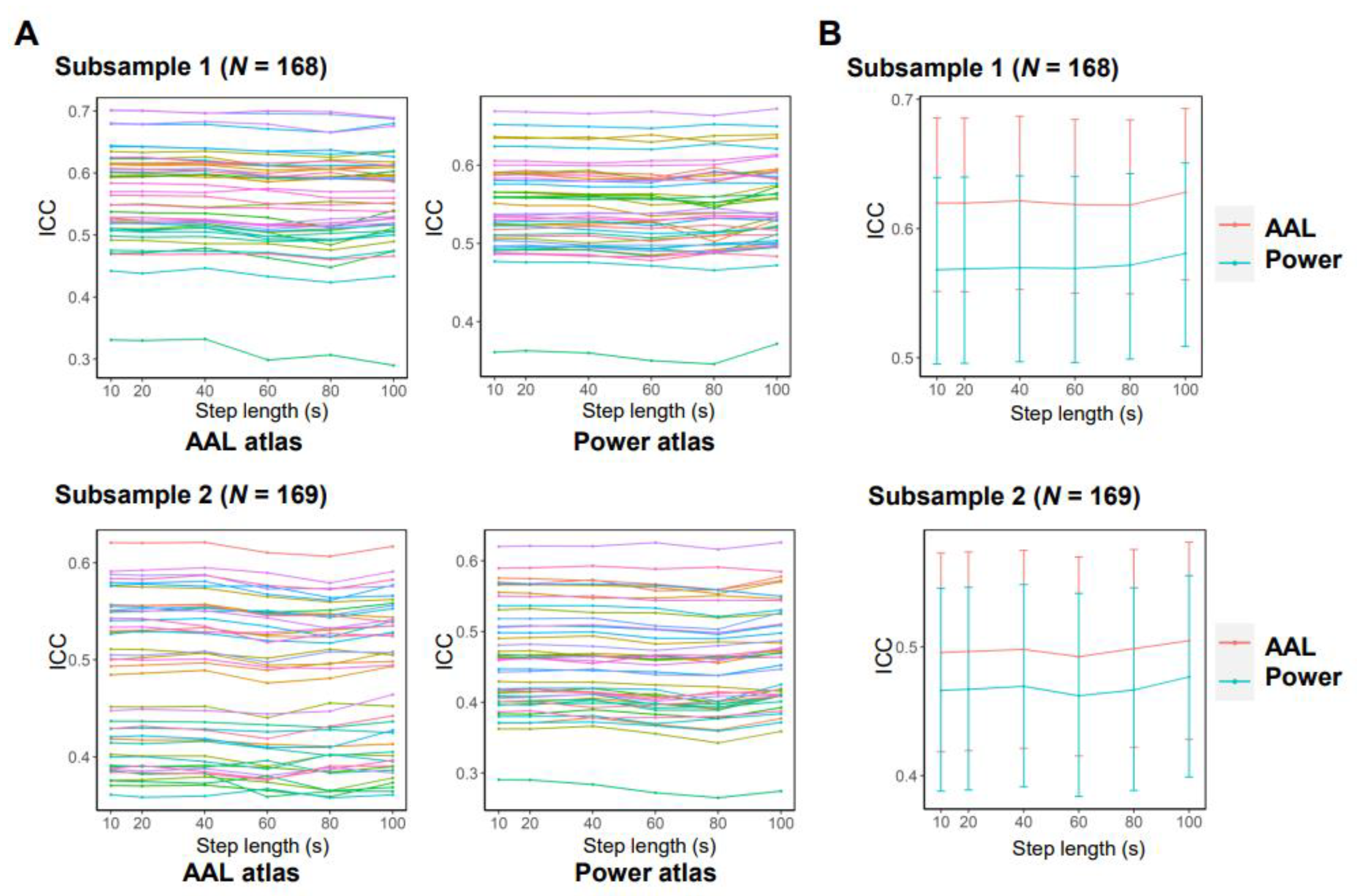

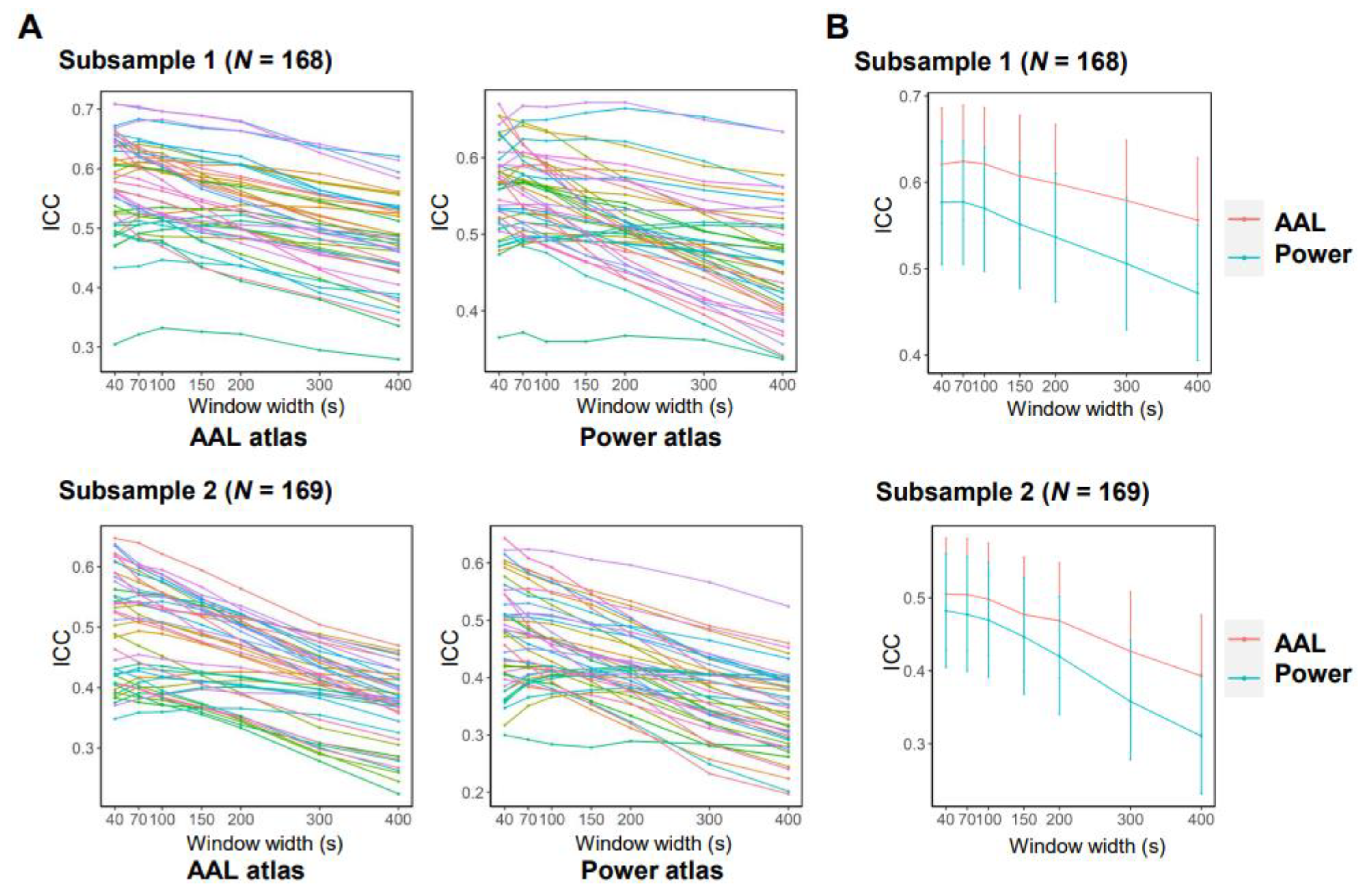

2.5. Effects of Data Acquisition and Processing Parameters

2.6. Exploratory Analyses of Sex and Age Effects

3. Results

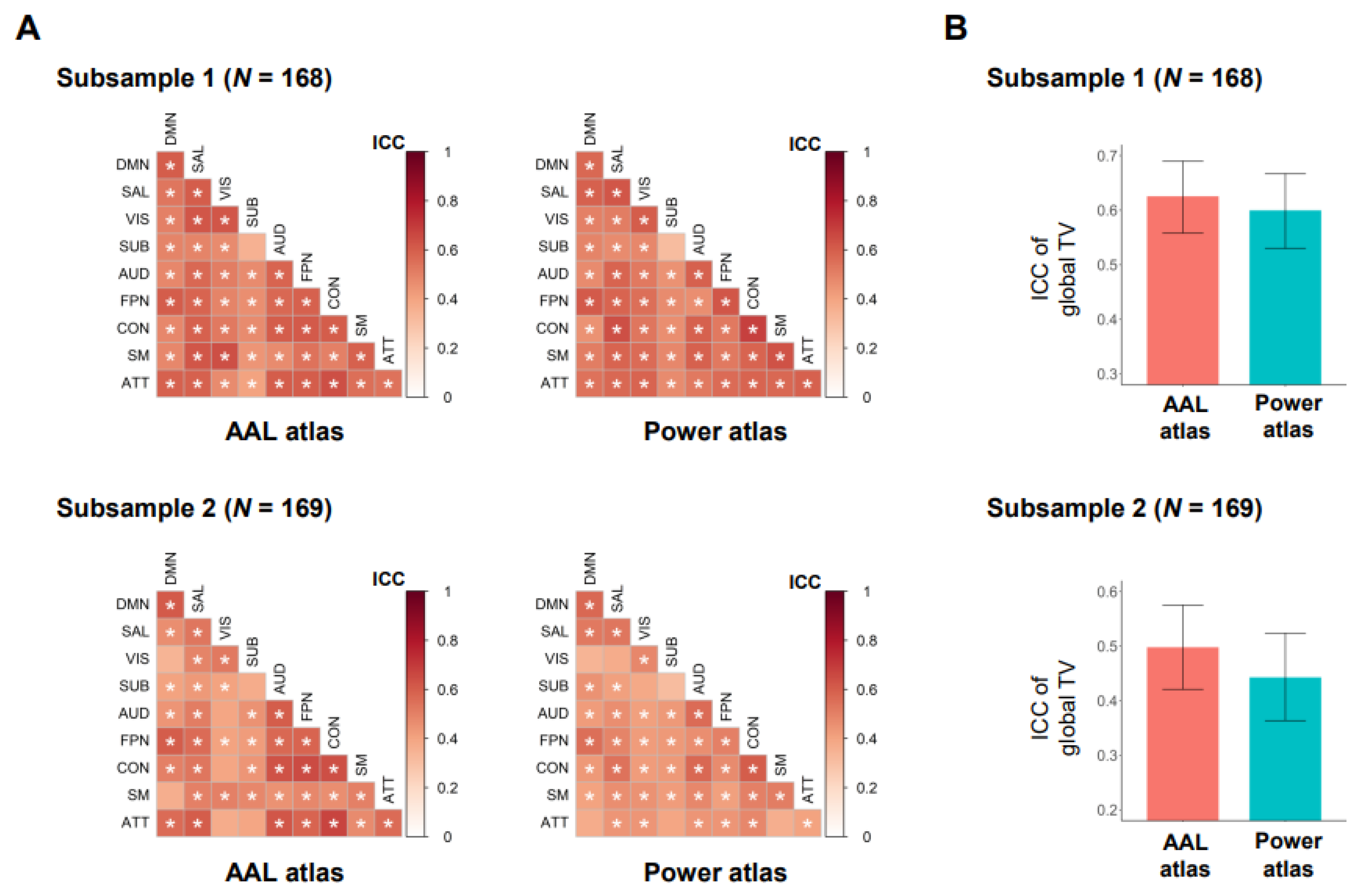

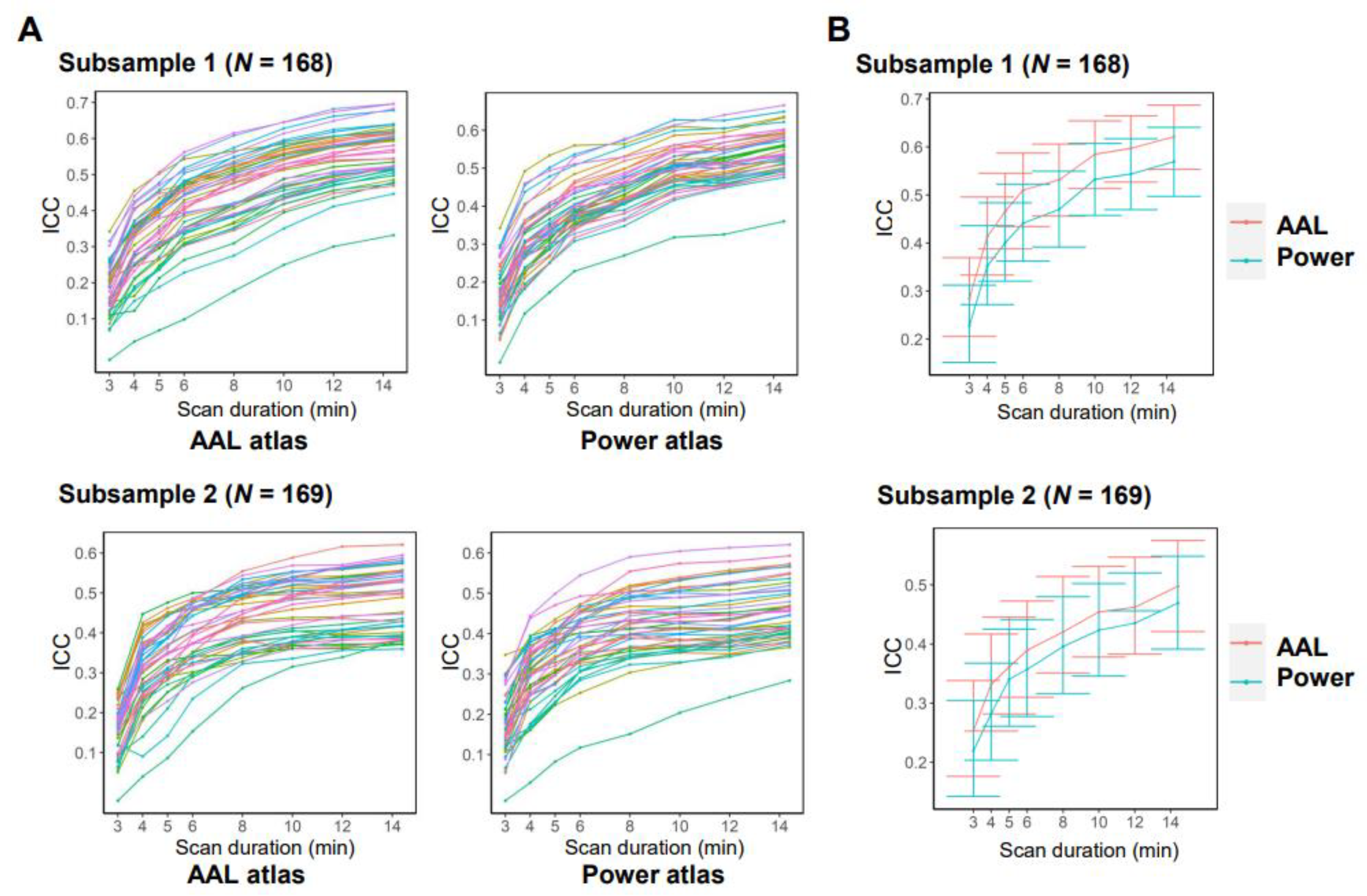

3.1. Primary Analysis

3.2. Effects of Data Acquisition and Processing Parameters

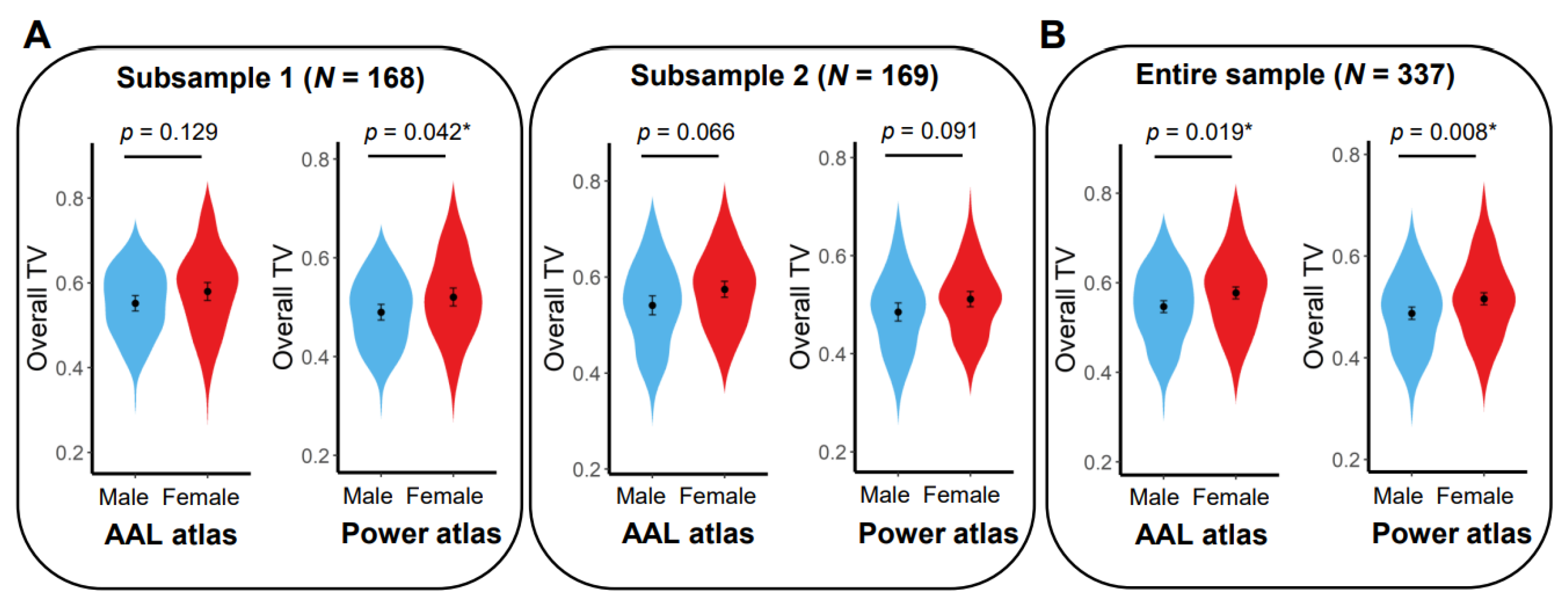

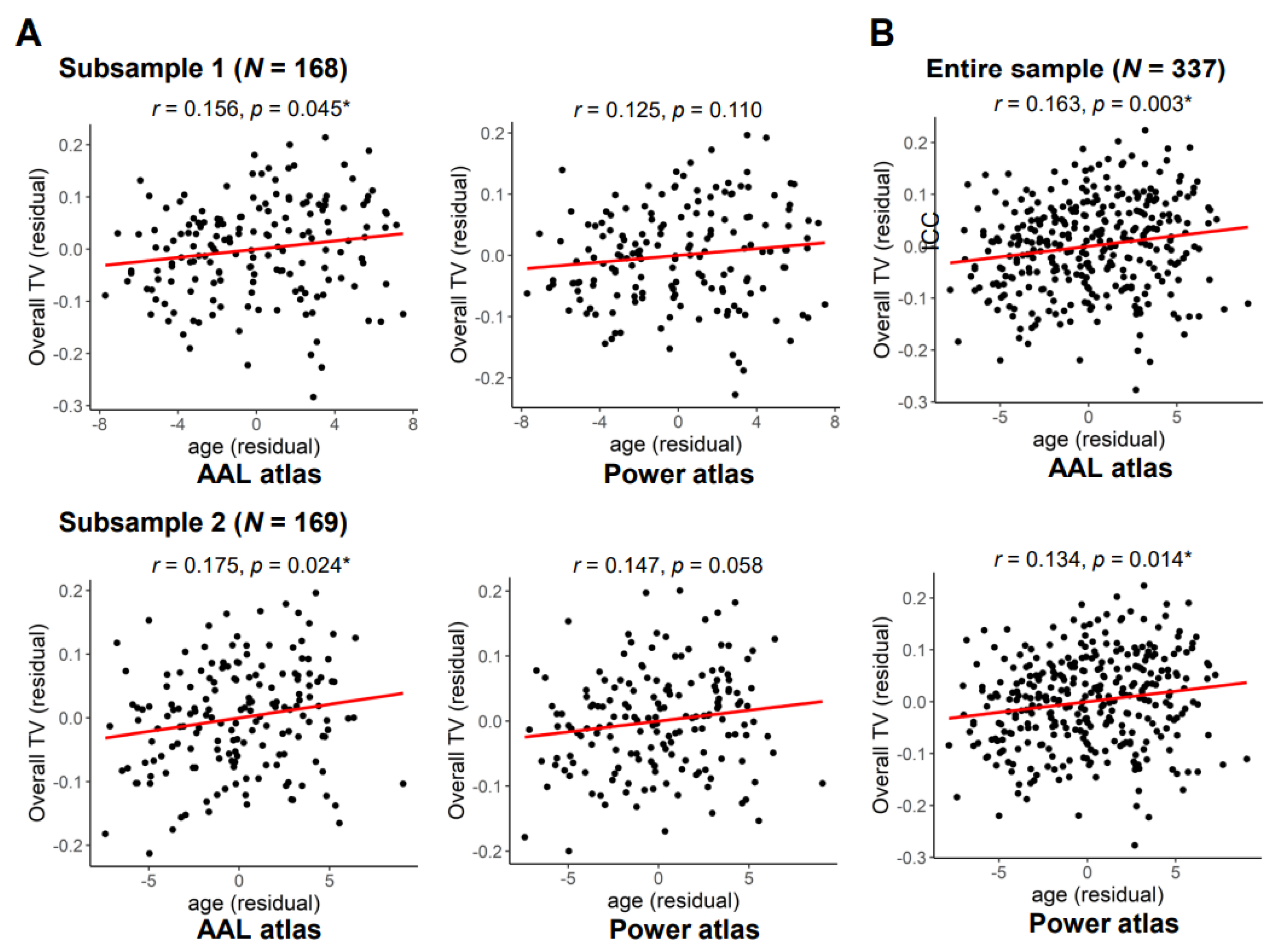

3.3. Exploratory Analyses of Sex and Age Effects

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, S.M.; Vidaurre, D.; Beckmann, C.F.; Glasser, M.F.; Jenkinson, M.; Miller, K.L.; Nichols, T.E.; Robinson, E.C.; Salimi-Khorshidi, G.; Woolrich, M.W.; et al. Functional Connectomics from Resting-State FMRI. Trends Cogn Sci 2013, 17, 666–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.; Lin, C.-L.; Chiang, M.-C. Exploring the Frontiers of Neuroimaging: A Review of Recent Advances in Understanding Brain Functioning and Disorders. Life 2023, 13, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Long, Y. Sex Differences in Human Brain Networks in Normal and Psychiatric Populations from the Perspective of Small-World Properties. Front Psychiatry 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Liu, D.; Huang, D.; Long, Y. Acute Effect of Betel Quid Chewing on Brain Network Dynamics: A Resting-State Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 701420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Zhou, H.; Cannon, T.D. Functional Connectome-Wide Associations of Schizophrenia Polygenic Risk. Mol Psychiatry 2021, 26, 2553–2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Peng, D.; Tang, S.; Bi, A.; Long, Y. Aberrant Flexibility of Dynamic Brain Network in Patients with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Li, X.; Cao, H.; Zhang, M.; Lu, B.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Xu, M.; Liu, Z.; Yan, C.; et al. Common and Distinct Functional Brain Network Abnormalities in Adolescent, Early-Middle Adult, and Late Adult Major Depressive Disorders. Psychol Med 2024, 54, 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, W.; Ouyang, X.; Huang, D.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; He, Z.; Long, Y. Disrupted Intrinsic Functional Brain Network in Patients with Late-Life Depression: Evidence from a Multi-Site Dataset. J Affect Disord 2023, 323, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, R.M.; Womelsdorf, T.; Allen, E.A.; Bandettini, P.A.; Calhoun, V.D.; Corbetta, M.; Della Penna, S.; Duyn, J.H.; Glover, G.H.; Gonzalez-Castillo, J.; et al. Dynamic Functional Connectivity: Promise, Issues, and Interpretations. Neuroimage 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Xu, P.; Aleman, A.; Qin, S.; Luo, Y.-J. Dynamic Organization of Large-Scale Functional Brain Networks Supports Interactions Between Emotion and Executive Control. Neurosci Bull 2024, 40, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sporns, O. The Complex Brain: Connectivity, Dynamics, Information. Trends Cogn Sci 2022, 26, 1066–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Z. Temporal Stability of the Dynamic Resting-State Functional Brain Network: Current Measures, Clinical Research Progress, and Future Perspectives. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, A.D.; Lindquist, M.A.; DeRosse, P.; Karlsgodt, K.H. Dynamic Functional Connectivity States Reflecting Psychotic-like Experiences. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 443–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Chattun, M.R.; Zhang, S.; Bi, K.; Tang, H.; Yan, R.; Wang, Q.; Yao, Z.; Lu, Q. Dynamic Community Structure in Major Depressive Disorder: A Resting-State MEG Study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019, 92, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Chen, C.; Deng, M.; Huang, X.; Tan, W.; Zhang, L.; Fan, Z.; Liu, Z. Psychological Resilience Negatively Correlates with Resting-State Brain Network Flexibility in Young Healthy Adults: A Dynamic Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study. Ann Transl Med 2019, 7, 809–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, K.; Lv, L.; Tang, S.; Zou, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Yang, Y.; Long, Y. Disrupted Static and Dynamic Small-World Brain Network Topologies in Patients with Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2025, 284, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cheng, W.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Lei, X.; Yao, Y.; Becker, B.; Liu, Y.; Kendrick, K.M.; Lu, G.; et al. Neural, Electrophysiological and Anatomical Basis of Brain-Network Variability and Its Characteristic Changes in Mental Disorders. Brain 2016, 139, 2307–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chan, C.K.Y.; Wu, G.; Xue, Z.; Pan, Y.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Li, D.; Pu, W. Altered Temporal Variability of Local and Large-Scale Resting-State Brain Functional Connectivity Patterns in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, D.; Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Jia, X.; Li, Y.; Xin, F.; Yao, D.; Luo, C. Reconfiguration of Dynamic Functional Connectivity in Sensory and Perceptual System in Schizophrenia. Cerebral Cortex 2019, 29, 3577–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, J.; Dai, J.; Li, F.; Chen, B.; He, R.; Liao, Y.; Yao, D.; Dong, W.; Xu, P. Altered Temporal Variability in Brain Functional Connectivity Identified by Fuzzy Entropy Underlines Schizophrenia Deficits. J Psychiatr Res 2022, 148, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Cao, H.; Yan, C.; Chen, X.; Li, L.; Castellanos, F.X.; Bai, T.; Bo, Q.; Chen, G.; Chen, N.; et al. Altered Resting-State Dynamic Functional Brain Networks in Major Depressive Disorder: Findings from the REST-Meta-MDD Consortium. Neuroimage Clin 2020, 26, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ding, K.; Li, F.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Z.; Yin, Y.; Kong, Y.; Yuan, Y. Default Mode Network Static-Dynamic Functional Signatures in First-Episode Drug-Naive Major Depressive Disorder. Compr Psychoneuroendocrinol 2025, 23, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Huang, J.; Deng, L.; He, N.; Cheng, L.; Shu, P.; Yan, F.; Tong, S.; Sun, J.; Ling, H. Abnormal Dynamic Functional Connectivity Associated With Subcortical Networks in Parkinson’s Disease: A Temporal Variability Perspective. Front Neurosci 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, M.; Zahr, N.M.; Saranathan, M.; Honnorat, N.; Farrugia, N.; Pfefferbaum, A.; Sullivan, E. V.; Chanraud, S. Altered Cerebro-Cerebellar Dynamic Functional Connectivity in Alcohol Use Disorder: A Resting-State FMRI Study. The Cerebellum 2021, 20, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Dong, D.; Dong, G.-H. Temporal Variability-Based Alternations in Dynamic Functional Networks in Internet Gaming Disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2025, 187, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wu, Z.; Cao, H.; Chen, X.; Wu, G.; Tan, W.; Liu, D.; Yang, J.; Long, Y.; Liu, Z. Age-Related Decrease in Default-Mode Network Functional Connectivity Is Accelerated in Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Front Aging Neurosci 2022, 13, 809853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhao, R.; He, Z.; Chang, M.; Wang, F.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Xi, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Abnormal Dynamic Functional Connectivity after Sleep Deprivation from Temporal Variability Perspective. Hum Brain Mapp 2022, 43, 3824–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Rolls, E.T.; Chen, Q.; Yao, Y.; Yang, W.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Feng, J.; et al. Verbal Creativity Correlates with the Temporal Variability of Brain Networks during the Resting State. Cerebral Cortex 2019, 29, 1047–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Kang, X.; Wang, H.; Cong, J.; Zhuang, W.; Xue, K.; Li, F.; Yao, D.; Xu, P.; Zhang, T. The Relationships between Dynamic Resting-State Networks and Social Behavior in Autism Spectrum Disorder Revealed by Fuzzy Entropy–Based Temporal Variability Analysis of Large-Scale Network. Cerebral Cortex 2023, 33, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Liu, X.; Long, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Bian, D.; Tang, S. Problematic Smartphone Use Is Associated with Differences in Static and Dynamic Brain Functional Connectivity in Young Adults. Front Neurosci 2022, 16, 1010488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, L.; Feng, Q.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Tang, S.; Jia, H.; Li, Y.; Qiu, J. Depression Links to Unstable Resting-State Brain Dynamics: Insights from Hidden Markov Models and Functional Network Variability. Psychol Med 2025, 55, e200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Y.; Ouyang, X.; Yan, C.; Wu, Z.; Huang, X.; Pu, W.; Cao, H.; Liu, Z.; Palaniyappan, L. Evaluating Test–Retest Reliability and Sex-/Age-related Effects on Temporal Clustering Coefficient of Dynamic Functional Brain Networks. Hum Brain Mapp 2023, 44, 2191–2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, U.; Plichta, M.M.; Esslinger, C.; Sauer, C.; Haddad, L.; Grimm, O.; Mier, D.; Mohnke, S.; Heinz, A.; Erk, S.; et al. Test-Retest Reliability of Resting-State Connectivity Network Characteristics Using FMRI and Graph Theoretical Measures. Neuroimage 2012, 59, 1404–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Plichta, M.M.; Schäfer, A.; Haddad, L.; Grimm, O.; Schneider, M.; Esslinger, C.; Kirsch, P.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Tost, H. Test–Retest Reliability of FMRI-Based Graph Theoretical Properties during Working Memory, Emotion Processing, and Resting State. Neuroimage 2014, 84, 888–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, S.; Scheinost, D.; Constable, R.T. A Guide to the Measurement and Interpretation of FMRI Test-Retest Reliability. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2021, 40, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Hu, X.; Nguyen, V.T.; Guo, L.; Han, J.; Guo, C.C. Test–Retest Reliability of Functional Connectivity Networks during Naturalistic FMRI Paradigms. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 2226–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, A.S.; Nebel, M.B.; Barber, A.D.; Cohen, J.R.; Xu, Y.; Pekar, J.J.; Caffo, B.; Lindquist, M.A. Comparing Test-Retest Reliability of Dynamic Functional Connectivity Methods. Neuroimage 2017, 158, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Baum, S.A.; Adduru, V.R.; Biswal, B.B.; Michael, A.M. Test-Retest Reliability of Dynamic Functional Connectivity in Resting State FMRI. Neuroimage 2018, 183, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Marxen, M. Test-Retest Reliability of Dynamic Functional Connectivity Parameters for a Two-State Model. Network Neuroscience 2025, 9, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termenon, M.; Jaillard, A.; Delon-Martin, C.; Achard, S. Reliability of Graph Analysis of Resting State FMRI Using Test-Retest Dataset from the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2016, 142, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedaei, F.; Alizadeh, M.; Romo, V.; Mohamed, F.B.; Wu, C. The Effect of General Anesthesia on the Test–Retest Reliability of Resting-State FMRI Metrics and Optimization of Scan Length. Front Neurosci 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Essen, D.C.; Smith, S.M.; Barch, D.M.; Behrens, T.E.J.; Yacoub, E.; Ugurbil, K. The WU-Minn Human Connectome Project: An Overview. Neuroimage 2013, 80, 62–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasser, M.F.; Sotiropoulos, S.N.; Wilson, J.A.; Coalson, T.S.; Fischl, B.; Andersson, J.L.; Xu, J.; Jbabdi, S.; Webster, M.; Polimeni, J.R.; et al. The Minimal Preprocessing Pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2013, 80, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasser, M.F.; Coalson, T.S.; Bijsterbosch, J.D.; Harrison, S.J.; Harms, M.P.; Anticevic, A.; Van Essen, D.C.; Smith, S.M. Using Temporal ICA to Selectively Remove Global Noise While Preserving Global Signal in Functional MRI Data. Neuroimage 2018, 181, 692–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasser, M.F.; Coalson, T.S.; Bijsterbosch, J.D.; Harrison, S.J.; Harms, M.P.; Anticevic, A.; Van Essen, D.C.; Smith, S.M. Classification of Temporal ICA Components for Separating Global Noise from FMRI Data: Reply to Power. Neuroimage 2019, 197, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, D.S.; Harms, M.P.; Snyder, A.Z.; Jenkinson, M.; Wilson, J.A.; Glasser, M.F.; Barch, D.M.; Archie, K.A.; Burgess, G.C.; Ramaratnam, M.; et al. Human Connectome Project Informatics: Quality Control, Database Services, and Data Visualization. Neuroimage 2013, 80, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.L.; Spronk, M.; Kulkarni, K.; Repovš, G.; Anticevic, A.; Cole, M.W. Mapping the Human Brain’s Cortical-Subcortical Functional Network Organization. Neuroimage 2019, 185, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizemore, A.E.; Bassett, D.S. Dynamic Graph Metrics: Tutorial, Toolbox, and Tale. Neuroimage 2018, 180, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer, N.; Landeau, B.; Papathanassiou, D.; Crivello, F.; Etard, O.; Delcroix, N.; Mazoyer, B.; Joliot, M. Automated Anatomical Labeling of Activations in SPM Using a Macroscopic Anatomical Parcellation of the MNI MRI Single-Subject Brain. Neuroimage 2002, 15, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J.D.; Cohen, A.L.; Nelson, S.M.; Wig, G.S.; Barnes, K.A.; Church, J.A.; Vogel, A.C.; Laumann, T.O.; Miezin, F.M.; Schlaggar, B.L.; et al. Functional Network Organization of the Human Brain. Neuron 2011, 72, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.; Long, Y.; Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X. Temporal Stability of Dynamic Default Mode Network Connectivity Negatively Correlates with Suicidality in Major Depressive Disorder. Brain Sci 2022, 12, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholam Tamimi, M.; Daliri, M.R. State-Base Dynamic Functional Connectivity Analysis of FMRI Data during Facial Emotional Processing. Brain Imaging Behav 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Y.; Teng, T.; Liu, X.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ouyang, X.; et al. Childhood Trauma Is Linked to Abnormal Static-Dynamic Brain Topology in Adolescents with Major Depressive Disorder. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2023, 23, 100401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohr, H.; Wolfensteller, U.; Betzel, R.F.; Mišić, B.; Sporns, O.; Richiardi, J.; Ruge, H. Integration and Segregation of Large-Scale Brain Networks during Short-Term Task Automatization. Nat Commun 2016, 7, 13217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Chung, Y.; McEwen, S.C.; Bearden, C.E.; Addington, J.; Goodyear, B.; Cadenhead, K.S.; Mirzakhanian, H.; Cornblatt, B.A.; Carrión, R.; et al. Progressive Reconfiguration of Resting-State Brain Networks as Psychosis Develops: Preliminary Results from the North American Prodrome Longitudinal Study (NAPLS) Consortium. Schizophr Res 2020, 226, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shunkai, L.; Su, T.; Zhong, S.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, P.; Tang, G.; Qi, Z.; He, J.; et al. Abnormal Dynamic Functional Connectivity of Hippocampal Subregions Associated with Working Memory Impairment in Melancholic Depression. Psychol Med 2023, 53, 2923–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Ye, H.; Jiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, Y.; Yuan, Y. Abnormal Changes of Dynamic Topological Characteristics in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder. J Affect Disord 2024, 345, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Collinson, S.L.; Suckling, J.; Sim, K. Dynamic Reorganization of Functional Connectivity Reveals Abnormal Temporal Efficiency in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2019, 45, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalesky, A.; Breakspear, M. Towards a Statistical Test for Functional Connectivity Dynamics. Neuroimage 2015, 114, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Telesford, Q.K.; Franco, A.R.; Lim, R.; Gu, S.; Xu, T.; Ai, L.; Castellanos, F.X.; Yan, C.G.; Colcombe, S.; et al. Measurement Reliability for Individual Differences in Multilayer Network Dynamics: Cautions and Considerations. Neuroimage 2021, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, B.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Lei, J.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Sun, P.Z.; Xue, B.; Liu, H.; Xu, Z.Q.D. Within-Subject Test-Retest Reliability of the Atlas-Based Cortical Volume Measurement in the Rat Brain: A Voxel-Based Morphometry Study. J Neurosci Methods 2018, 307, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.X.; Liao, X.H.; Lin, Q.X.; Li, G.S.; Chi, Y.Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, M.R. Test-Retest Reliability of Graph Metrics in High-Resolution Functional Connectomics: A Resting-State Functional MRI Study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2015, 21, 802–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compère, L.; Siegle, G.J.; Young, K. Importance of Test–Retest Reliability for Promoting FMRI Based Screening and Interventions in Major Depressive Disorder. Transl Psychiatry 2021, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesierich, B.; Tuladhar, A.M.; ter Telgte, A.; Wiegertjes, K.; Konieczny, M.J.; Finsterwalder, S.; Hübner, M.; Pirpamer, L.; Koini, M.; Abdulkadir, A.; et al. Alterations and Test–Retest Reliability of Functional Connectivity Network Measures in Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Hum Brain Mapp 2020, 41, 2629–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Fu, X.; Deng, Q.; Palaniyappan, L.; Xiang, Z.; Huang, D.; Long, Y. Overprotection and Overcontrol in Childhood: An Evaluation on Reliability and Validity of 33-Item Expanded Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-33), Chinese Version. Asian J Psychiatr 2022, 68, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Chen, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Long, Y.; Chen, X. Factor Analysis and Evaluation of One-Year Test-Retest Reliability of the 33-Item Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in Chinese Adolescents. Front Psychol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Tao, H.; Ouyang, X.; Wu, G.; Chen, M.; Yu, M.; Zhou, L.; et al. Sex Difference in the Prevalence of Psychotic-like Experiences in Adolescents: Results from a Pooled Study of 21,248 Chinese Participants. Psychiatry Res 2022, 317, 114894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, B.; Xiang, Z.; Zou, Z.; Liu, Z.; Long, Y.; Chen, X. Increasing Trends in Mental Health Problems Among Urban Chinese Adolescents: Results From Repeated Cross-Sectional Data in Changsha 2016–2020. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skåtun, K.C.; Kaufmann, T.; Brandt, C.L.; Doan, N.T.; Alnæs, D.; Tønnesen, S.; Biele, G.; Vaskinn, A.; Melle, I.; Agartz, I.; et al. Thalamo-Cortical Functional Connectivity in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder. Brain Imaging Behav 2018, 12, 640–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, S.M.; Guillery, R.W. The Role of the Thalamus in the Flow of Information to the Cortex. In Proceedings of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences; 2002; Vol. 357. 1695–1708.

- Kraft, D.; Fiebach, C.J. Probing the Association between Resting-State Brain Network Dynamics and Psychological Resilience. Network Neuroscience 2022, 6, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Gao, P.; Ji, Y.; Shi, H. Integration and Segregation of Dynamic Functional Connectivity States for Mild Cognitive Impairment Revealed by Graph Theory Indicators. Contrast Media Mol Imaging 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Braun, S.E.; Steinberg, J.L.; Bjork, J.M.; Martin, C.E.; Keen II, L.D.; Moeller, F.G. Effect of Scanning Duration and Sample Size on Reliability in Resting State FMRI Dynamic Causal Modeling Analysis. Neuroimage 2024, 292, 120604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.; Bodurka, J.; Bandettini, P.A. How Long to Scan? The Relationship between FMRI Temporal Signal to Noise Ratio and Necessary Scan Duration. Neuroimage 2007, 34, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ooi, L.Q.R.; Orban, C.; Zhang, S.; Nichols, T.E.; Tan, T.W.K.; Kong, R.; Marek, S.; Dosenbach, N.U.F.; Laumann, T.O.; Gordon, E.M.; et al. Longer Scans Boost Prediction and Cut Costs in Brain-Wide Association Studies. Nature 2025, 644, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lacy, N.; McCauley, E.; Kutz, J.N.; Calhoun, V.D. Sex-Related Differences in Intrinsic Brain Dynamism and Their Neurocognitive Correlates. Neuroimage 2019, 202, 116116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Subsample 1 (N = 168), Mean ± SD |

Subsample 2 (N = 169), Mean ± SD |

Group Comparisons | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 28.65 ± 3.74 | 28.57 ± 3.66 | t = 0.186, p = 0.853 |

| Sex (male/female) | 78/90 | 79/90 | χ2 = 0.003, p = 0.953 |

| Mean FD (mm) a | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | t = -0.019, p = 0.985 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).