1. Introduction

Human brain connectomics is a field of research that has emerged as a result of the large availability of neuroimaging datasets in recent years [

1]. This field of study has the potential to answer many open questions about the structure and function of the human brain. Furthermore, connectomics based analyses have uncovered differences between healthy and disease conditions [

2,

3]. However, in order to further validate the reliability of such studies and deepen the understanding of individual characteristics that can be overlooked in cohort studies, the concept of a “brain connectivity fingerprint” [

4,

5,

6] has gotten a lot of attention.

Functional connectivity fingerprinting of the brain refers to the ability to identify an individual FC from a set of FCs in repeated fMRI imaging sessions. The existence of a brain fingerprint has been established in the last decade with work done with data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) [

7,

8]. Such studies have shown that the functional connectome (FC) of the brain varies between individuals, therefore serving to some extent as a

fingerprint. In the literature, different studies of FC fingerprinting have been conducted with varying approaches, such as principal component analysis (PCA) [

9,

10], sparse dictionary learning (SDL) [

11], geodesic distance in regularized FC [

12] and correlation distance in FC tangent space projections [

13]. In [

9], the authors show that individual connectivity profiles can be reconstructed through an optimal linear combination of PCA-derived orthogonal components. In [

10], the authors perform PCA in a subset of “learning” FCs to obtain an eigenspace to which the “validation” FCs are projected, thus enabling the identification of the fMRI condition or the participant to which the “validation” FC belongs. In [

11], SDL is used to refine FC profiles, leading to a higher distinctiveness in FCs relative to raw connectivity. PCA and SDL work on 2-dimensional data, while Tucker decomposition is designed for higher-dimensional data structures called tensors, essentially allowing it to analyze complex relationships across multiple variables in a dataset by decomposing it into a core tensor and factor matrices along each dimension. In essence, Tucker decomposition may be thought of as a “higher-order PCA”.

Using the fact that FCs estimated as correlation matrices lie on or inside a Symmetric Positive Definite (SPD) manifold, Venkatesh and colleagues proposed using geodesic distance to compare FCs [

14]. In a follow-up study [

12], the authors explored how optimally regularized FCs maximize the individual fingerprint of participants, measured by the geodesic distance between their FCs. A limitation of this approach is that the geodesic distance between FCs of size

is a map

. Hence, even though the geodesic distance provides a global measure of similarity between FCs, it does not directly highlight the specific features that make the individual’s functional connectivity unique. As an alternative to using FCs, tangent FCs have demonstrated a high capacity to predict cognition and behavior [

15,

16,

17]. Most recently, [

13] analyzed the effects of tangent FCs with respect to fingerprinting. In that study, a high degree of fingerprinting was achieved not only for the test / retest sessions but also for the successful matching of twins.

To simultaneously overcome the drawbacks of the studies mentioned above, we propose to utilize tensor decomposition for FC fingerprinting. Tensor decomposition enables projecting high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space, preserving its structure while independently extracting meaningful information from each dimension.

Tensors are multidimensional arrays with applications in various fields, including signal processing, computer vision, and neuroscience [

18]. In brain connectomics, tensors enable modeling and analyzing the functional and structural connections within the brain by reducing the dimensionality of complex, interrelated, and high-dimensional data through tensor decomposition. In [

19], the authors studied the dynamics of FCs to understand the process of formation and dissolution of brain functional networks through tensor decomposition techniques. In another study [

20], it was demonstrated how the analysis of the tensor components enables the extraction of unbiased and interpretable descriptions of single-trial dynamics across many trials through low-dimensional representations of neural data. In [

21], the authors discuss challenges associated with interpreting the brain connectivity patterns derived from tensor decomposition. To our knowledge, only [

22] has considered using tensors in brain connectivity fingerprinting analysis in the literature. However, their study was based on structural connectivity. The task of identifying subjects through their functional connectomes has the additional challenge of dynamic changes and functional reconfigurations happening at a fast rate in response to cognitive stimuli.

Our study assesses how tensor decomposition of functional connectivity is related to fingerprinting measured by matching rate [

23]. Specifically, we used Tucker’s decomposition [

24] to uncover brain fingerprints derived from FCs. Tucker decomposition decomposes a tensor into a core tensor and a set of

n factor matrices, where

n is the number of dimensions of the tensor. The core tensor can be thought of as a compressed version of the original tensor and the factor matrices as principal components along the

n dimensions of the tensor. Considering the focus of brain fingerprinting of this study, the tensors here used were obtained by concatenating all participants’ functional connectivity matrices from one scanning session, thus resulting in three-dimensional tensors. Decomposing such tensors via Tucker decomposition yields a core tensor and three factor matrices, the first two of which capture cohort-level functional connectivity patterns, while the third captures participant-specific patterns. We used data from all fMRI conditions available in the Young-Adult Human Connectome Project (HCP) Dataset, which consists of two fMRI data acquisition sessions (referred to as test and retest throughout this paper) from 1200 participants. In particular, we focused on a subset of that dataset consisting of 426 unrelated participants. Our chosen measurement of fingerprinting was matching rate [

23], which measures among participants how often (percentage of times) one session is correctly paired with another session (and vice versa).

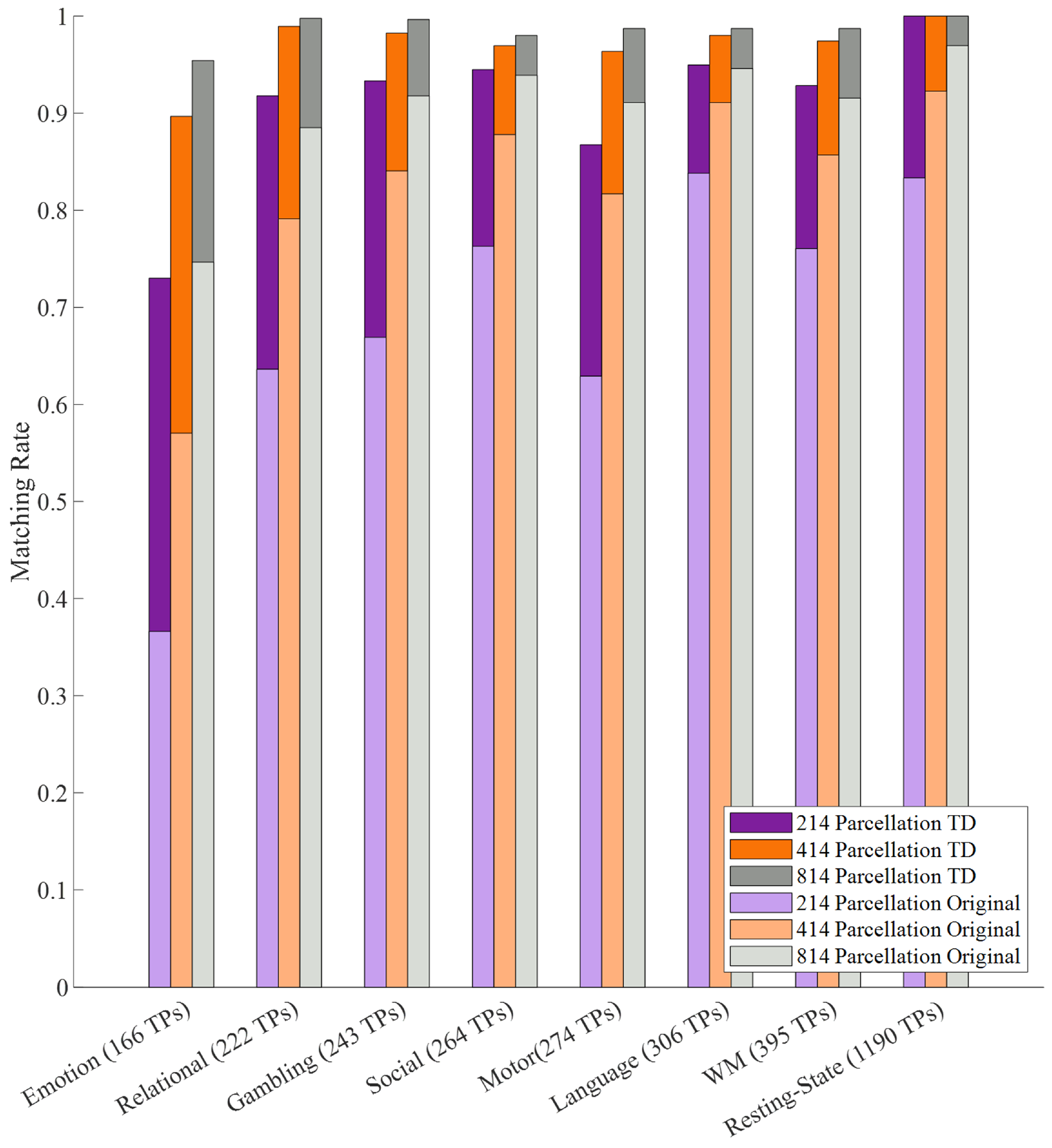

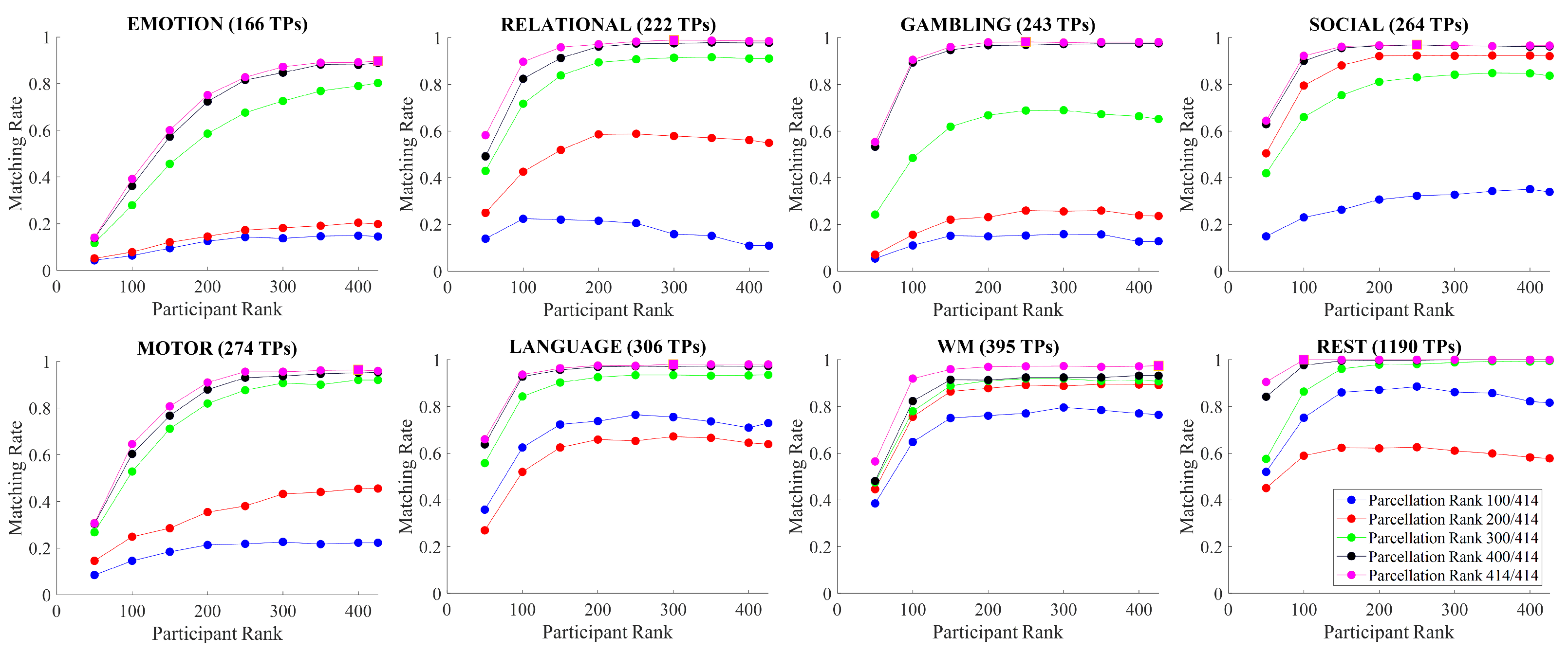

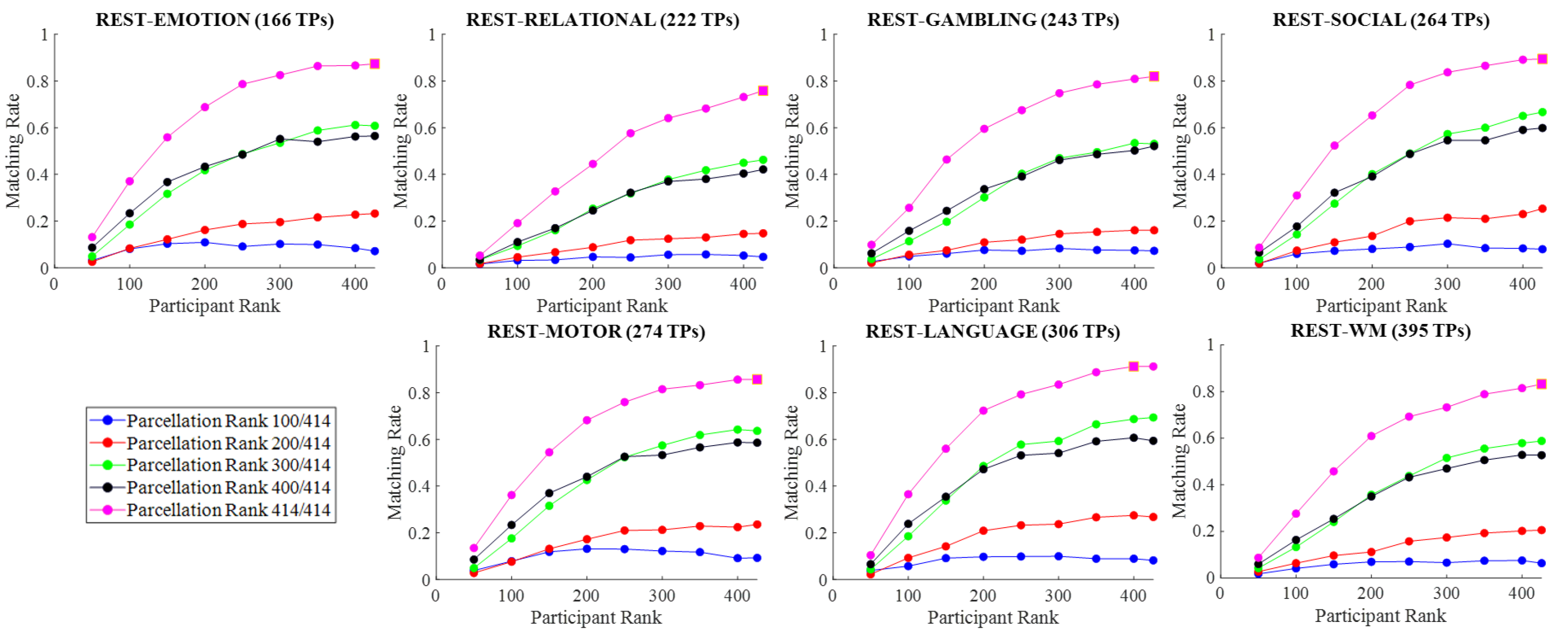

The aims of this paper are: (i) assess the impact of Tucker decomposition on functional connectome fingerprinting in within- and between-fMRI condition settings for different parcellation granularities, (ii) estimate optimal levels of compression of brain parcellation-specific and participant-specific information that maximize fingerprinting, and (iii) analyze how sampling in resting-state prior to Tucker decomposition affects fingerprinting.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In the [sec:data]Materials and Methods section, we: (i) describe the data set used in this study as well as the preprocessing procedures, (ii) provide a review of multilinear algebra and tensor decomposition algorithms, (iii) introduce Tucker decomposition, and (iv) describe matching rate, the fingerprinting measurement used in this study. In the [sec:results]Results section, we: (i) uncover fingerprinting within and between fMRI conditions, (ii) disclose optimal levels of compression of parcellation-specific and participant-specific information that maximize fingerprinting, and (iii) present the findings for the different strategies of sampling time points in resting-state time series. In the [sec:discussion]Discussion section, we (i) discuss our findings and provide possible interpretations of them and (ii) highlight some limitations of our study and make suggestions for future work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

The data set used in this study consists of the eight fMRI conditions available in the Young-Adult HCP Dataset [

25]. Specifically, we used a subset of 426 unrelated participants (223 women, mean age: 28.67 years, range: 22–36) to eliminate the need to account for potential hereditary factors that could have an influence on fingerprinting. fMRI conditions include: resting-state (RS), emotion processing (EP), gambling (GAM), language (LAN), motor (MOT), relational processing (REL), social cognition (SOC), and working memory (WM). For each condition, participants underwent two sessions corresponding to two different acquisitions (left-to-right, LR, and right-to-left, RL). In our study, we refer to these as test and retest sessions. The resting-state scans were acquired in four sessions (“REST1” and “REST2”) on two different days. Only the two sessions of REST1 were used in this work.

2.2. Brain Parcellations

In this work, we used the

Schaefer parcellation functional brain atlases of the human cortex [

26]. The

Schaefer parcellation is based on resting-state fMRI data from 1489 participants, which were registered using surface alignment. The Schaefer parcellation was obtained via a gradient-weighted Markov random field that integrates local gradient and global similarity approaches and is available at ten granularity levels, ranging from 100 to 1000 in steps of 100 in both volumetric and grayordinate space. The grayordinate versions of the parcellations are in the same surface space as the HCP fMRI data, therefore, mapping the parcellations onto the fMRI data is trivial. Furthermore, using surface-mapping produces a better alignment between the fMRI data and the Schaefer parcellations in comparison to when volumetric mapping is used. Consequently, we used the surface-based mapping to map the 200, 400, and 800 granularity Schaefer parcellations onto the fMRI data. For completeness, 14 subcortical regions were added to each parcellation, as provided by the HCP release (filename Atlas_ROI2.nii.gz). To do so, this file was converted from NIFTI to CIFTI format using the HCP workbench software (

www.humanconnectome.org/software/connectome-workbench.html,

wb_command -cifti-createlabel). As a result, the Schaefer-200 parcellation, for example, ultimately contained 214 brain regions.

2.3. Preprocessing

A “minimal” preprocessing pipeline from the HCP, which includes artifact removal, motion correction, and registration to a standard template, was used [

27]. More details can be found in the literature [

28,

29].

The “minimal” preprocessing pipeline was improved upon through the addition of extra steps. These steps were also described at [

13]. For resting-state fMRI data we: (i) regressed out the global gray matter signal from the voxel time courses [

27], (ii) applied a first-order Butterworth bandpass filter in the forward and the reverse directions [0.001–0.08

Hz [

27], functions

butter and

filtfilt in MATLAB], and (iii) z-scored and averaged, per brain regions, the voxel time courses, excluding any outlier time points falling outside three standard deviation from the mean (workbench software,

wb_command -cifti-parcellate). The same steps were repeated for all fMRI tasks, however, a larger frequency range was used in the bandpass filter (0.001–0.250) [

30], since the optimal range is unclear [

31].

2.4. Estimation of Whole-Brain FCs

The functional connectivity between pairs of brain regions was estimated by computing Pearson’s correlation (corr MATLAB function), which results in a symmetric correlation matrix, with M being the number of brain regions for a given parcellation. Throughout this article, this correlation matrix is referred to as FC. For each participant, we computed a whole-brain FC for each of the two sessions (test and retest), each fMRI condition (all seven tasks and resting state), and different parcellation granularities (214, 414, and 814).

2.5. Tensor Notation and Linear Algebra

In this work, we refer to multidimensional arrays as tensors. The order of a tensor describes the number of dimensions it has. Zero-order tensors are scalars, first-order tensors are vectors, second-order tensors are matrices, and tensors of order three or higher are referred to as higher-order tensors. The tensor notation used in this paper is largely adapted from [

18]. Throughout the paper, higher-order tensors are denoted by Euler script letters, e.g.,

, matrices are denoted by boldface capital letters, e.g.,

, vectors are denoted by boldface lowercase letters, e.g.,

, and scalars are denoted by lower or upper case letters, e.g.,

x or

X. Entries of a matrix or a tensor are denoted by lowercase letters with subscripts, e.g., the

entry of an

N-order tensor

is denoted by

.

Equivalently to rows and columns from matrices, tensors have fibers. Fibers are constructed by fixing every index of the tensor, but one. Hence, tensors have as many fibers as dimensions. A matrix column is a mode-1 fiber, and a matrix row is a mode-2 fiber. This concept can also be extended to higher-order tensors. For instance, third-order tensors have column (mode-1), row (mode-2), and tube (mode-3) fibers, which are denoted by , , and , respectively. A slice is defined by fixing all entries from the tensor except two. For example, we can define the slices , , and for a third-order tensor.

An N-order tensor can be flattened into a matrix, a process known as matricization or flattening. The mode-n matricization of a tensor is denoted by and arranges the mode-n one-dimensional fibers to be the columns of the resulting matrix. The n-mode matrix product between a tensor and a matrix is denoted by and is of size .

The inner product of and is the sum of the product of their entries, i.e., The norm of tensor is defined as For matrices, refers to the Frobenius norm, and for vectors, refers to the analogous norm.

2.6. Tensor Decomposition

In recent years, tensors have become increasingly popular in the fields of signal processing, machine learning, and neuroscience for their capacity to model complex high-order relationships among objects [

32,

33,

34]. Tensor decomposition enables projecting high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving the original structure of the data. For the purpose of brain fingerprinting, tensor decomposition has the potential of extracting unique features from each participant’s fMRI data acquisition session, thus facilitating subject distinctiveness. Several tensor decomposition algorithms can be found in the literature, each with their own characteristics and applications. The most commonly used ones are the CANDECOMP/PARAFAC (CP) [

35,

36] decomposition and the Tucker decomposition [

24].

The CP decomposition factorizes a tensor into a sum of rank-one tensors, with a rank-one tensor being expressed by the outer product between vectors. For a N-order tensor , its CP decomposition is given by:

where

R, which represents the number of rank-one tensors used to reconstruct the original tensor, is the rank of the decomposition,

is a scaling constant for each of the components, and

, for

, are factor matrices. The last equality shows the shorthand

introduced in [

37].

The Tucker decomposition decomposes a tensor into a core tensor multiplied by a matrix along each of the tensor modes [

24]. For

, its

n-rank, denoted by

, is defined as the column rank of its mode-

n matricization

. In other words, the

n-rank is the number of linearly independent vectors that span the basis of the

mode-n fibers of

. The Tucker decomposition of

is defined as:

Here,

, ⋯,

are column-wise orthonormal matrices referred to as factor matrices, and

are the ranks of the decomposition, where

for

. If

), we refer to the decomposition as a truncated Tucker decomposition and refer to it as a rank-(

) decomposition. The tensor

is referred to as the core tensor and its entries represent the level of interaction between the different factors. Note that the CP decomposition can be understood as a special case of the Tucker decomposition when the Tucker’s core is reduced to a hyper-diagonal tensor (all non-diagonal entries are equal to zero) and

. For simplicity, consider the third-order tensor

. The Tucker decomposition of

is the solution of the minimization problem:

2.7. Tucker Decomposition Of Functional Connectomes

For each of the eight fMRI conditions analyzed in this study, we represent the data as a third-order tensor . Here, M is equal to the granularity of the brain parcellation and corresponds to the total number of participants. Given the symmetry of FC matrices, we refer to as a semi-symmetric tensor, which is defined as invariant under permutation of two (or more) indices. In our case, for . All analyses performed in this work have an input of a semi-symmetric tensor constructed by concatenating participants’ FCs obtained in one fMRI scanning session (either test or retest).

Once the data have been structured as a semi-symmetric tensor, we can produce a low-rank estimation of the FCs through either of the previously mentioned tensor decomposition methods. Due to the lack of interactions between components, the results of CP decomposition are generally easier to interpret [

21] compared to Tucker decomposition. However, this lack of interaction often leads CP to produce less accurate approximations of the original tensor, as measured by the

norm. In contrast, Tucker decomposition leverages its core tensor to capture interactions between components, enabling it to approximate the original tensor with greater precision [

38]. Considering the interpretability/accuracy trade-off in the context of brain fingerprinting, we focus on Tucker decomposition.

Several methods have been developed to estimate the Tucker decomposition. Here, we use the High-Order Singular Value Decomposition (HOSVD) [

39]. HOSVD is an extension of the classic Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to higher order arrays. Specifically, HOSVD factorizes a tensor into a core tensor and a set of column-wise orthogonal factor matrices. Similarly to PCA, the factor matrices capture most of the variance across each of the tensor modes. For a

N-order tensor

, the Tucker estimation via HOSVD is shown in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: Higher Order Singular Value Decomposition (HOSVD) |

|

Input:

- 1:

for to N do

- 2:

leading left singular vectors of

- 3:

end for - 4:

Output:

|

When applied to tensors that exhibit partial (or full) symmetries, HOSVD preserves the symmetric structure of the tensor [

39]. Hence, for a tensor consisting of one session (e.g., test sessions) of participants’ FC matrices, the Tucker decomposition of

can be reformulated as:

where the factor matrices

and

obtained via HOSVD contain, respectively, brain parcellation and participant-specific information and the ranks

and

express the compression levels of brain parcellation and participant-specific information. For the parcellation granularities considered in this study (214, 414, and 814), the brain parcellation ranks were chosen with a step size of

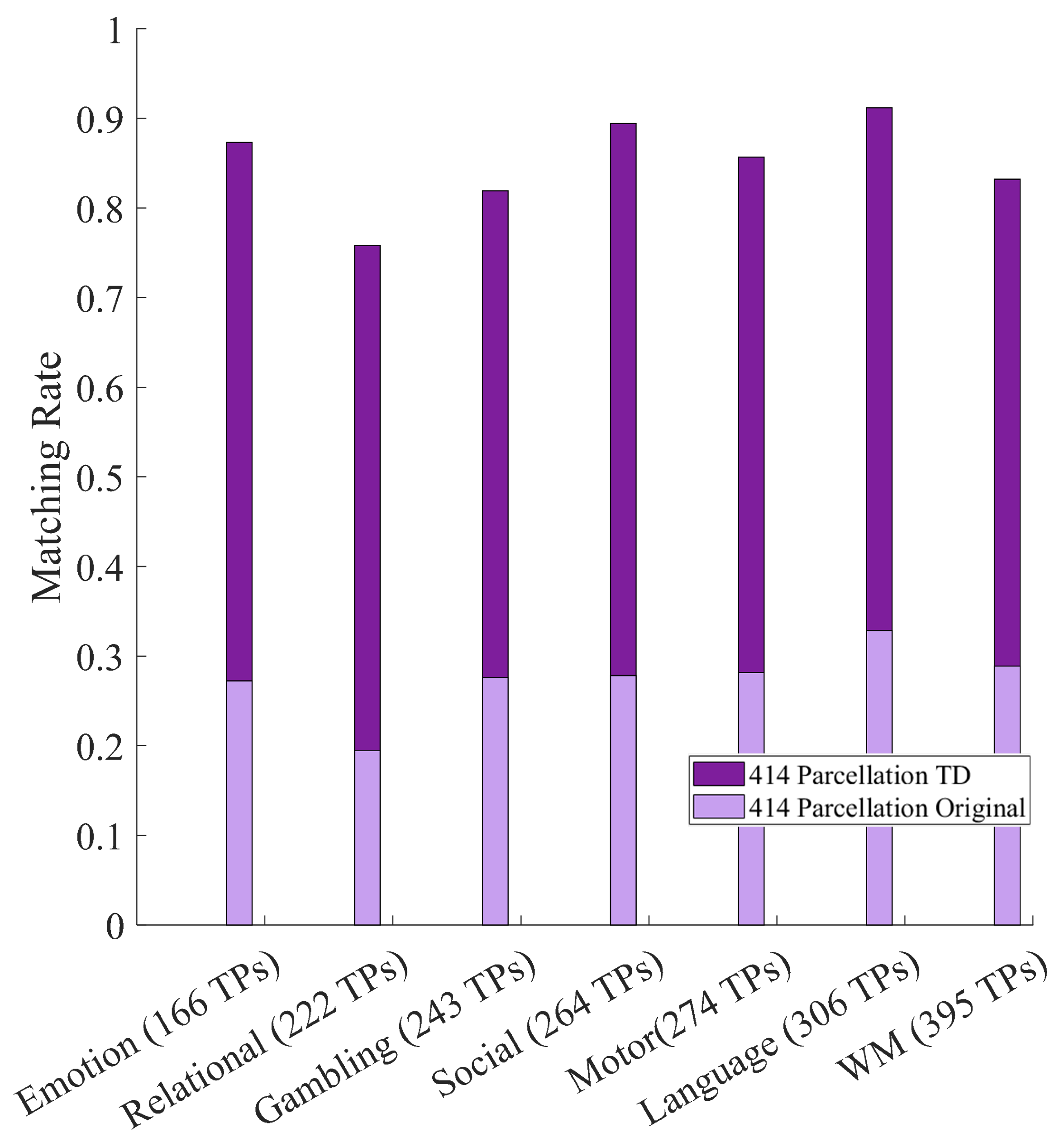

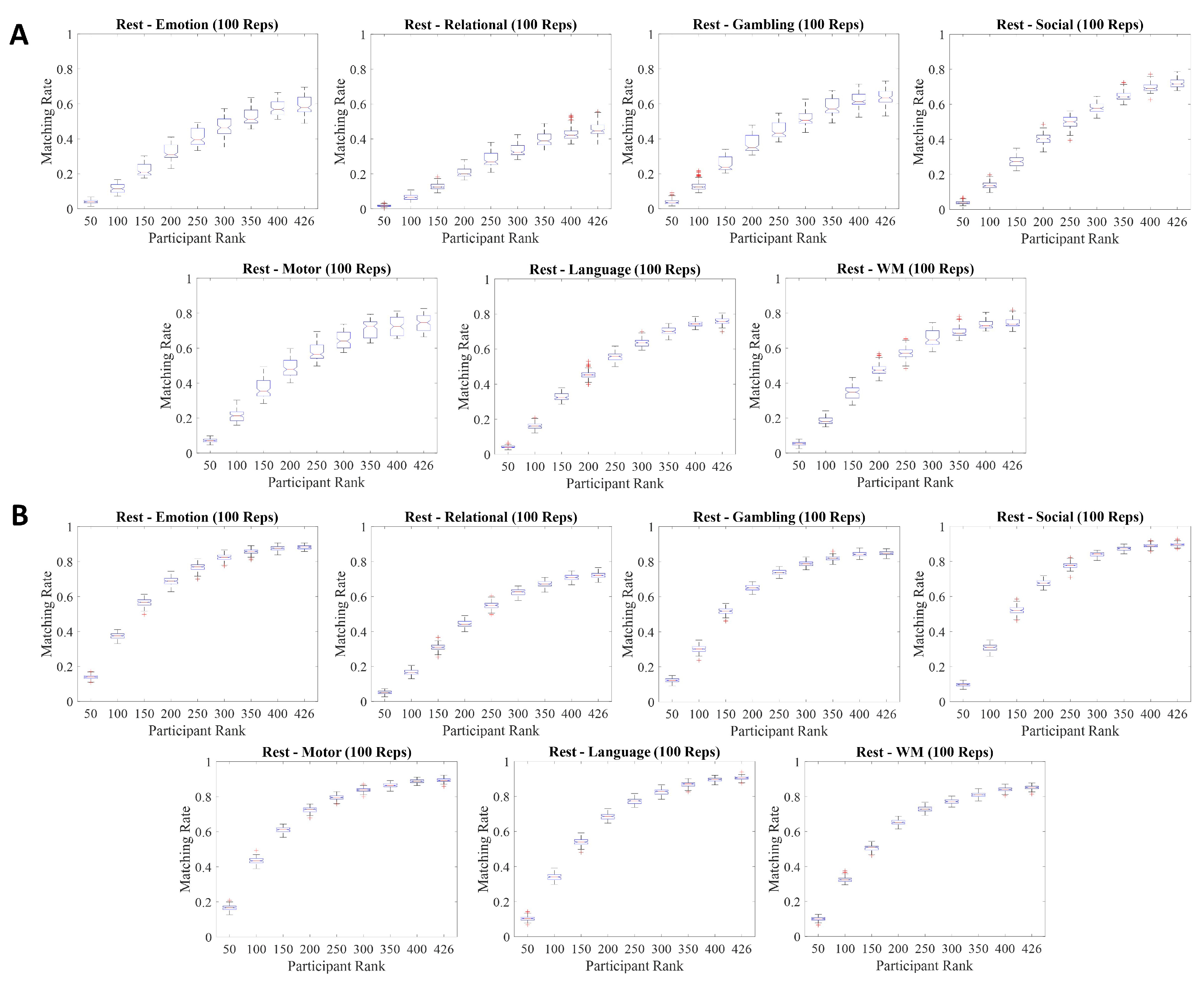

. In addition to the previous parcellation ranks, we also performed a full-rank decomposition. Thus, for a parcellation granularity of 414, for example, the brain parcellation ranks were set to

. In contrast, all participant ranks were fixed and set to

.

Under the hypothesis that the functional connectivity patterns of a participant are, to some extent, reproducible across scanning sessions, we fix the core tensor

and brain parcellation factor matrix

derived from the Tucker decomposition of tensor

and estimate the participant factor matrix

of the tensor

comprising of FCs from another data acquisition session (e.g., retest session). By doing so, we aim to detect a consistent presence of underlying cohort-level functional connectivity patterns across different data acquisition sessions for each participant. Such a problem can be formulated as follows:

The above problem admits a closed-form solution given by:

where

† denotes the Moore-Penrose inverse [

40] of a matrix, and

and

denote the

mode-3 matricization of

and

, respectively.

2.8. Fingerprinting Quantification

To quantify fingerprinting, we used a measure denominated matching rate [

23] for an identifiability matrix

, where

denotes the Pearson’s correlation between the

j-th row of the participant factor matrix

, and the

k-th row of the participant factor matrix

. The main diagonal entries of

represent similarity levels between different imaging sessions of the same participant. By hypothesis, we expect those entries to be higher than the off-diagonal entries, which represent the similarity level between different imaging sessions of different participants. Matching rate is a variation of

[

7] that accounts for the fact that each participant is present only once in the test and the retest sets.

(

1) is the average frequency at which a participant’s test session is most highly correlated to their retest session, and their retest session is most highly correlated to their test session (note that one does not necessarily imply the other). For matching rates, we impose that once a test session is paired with a retest session, it can no longer be chosen for a new pairing. The relative frequency of successful participants matching in both directions is then averaged, yielding a value in the range

, where 0 indicates a failure to correctly match any of the participant’s FCs, and 1 indicates success in matching all participant’s FCs correctly. An algorithmic description of the computation of the matching rate is presented in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2: Matching Rate Computation |

|

Input:

- 1:

- 2:

- 3:

for to N do

- 4:

- 5:

- 6:

if then

- 7:

- 8:

end if

- 9:

-inf - 10:

-inf - 11:

end for - 12:

- 13:

- 14:

for to N do

- 15:

- 16:

- 17:

if then

- 18:

- 19:

end if

- 20:

-inf - 21:

-inf - 22:

end for - 23:

Output:

|

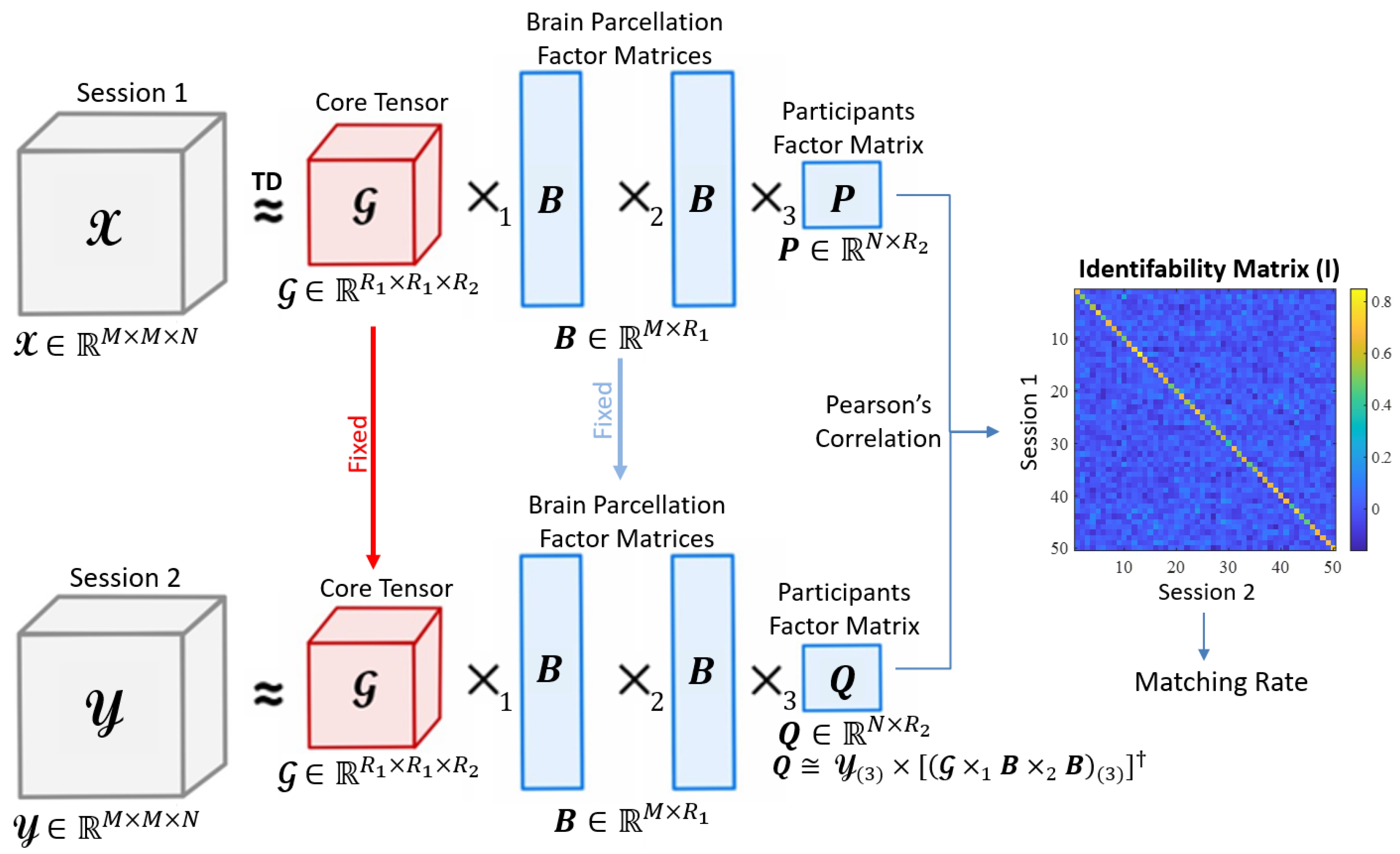

2.9. Fingerprinting Framework Adapted to Tucker Decomposition

Our fingerprinting framework consists of five key steps:

i) given a data acquisition session (either test or retest) of an fMRI condition, construct a tensor that contains all participants FCs,

ii) decompose the tensor via Tucker decomposition to obtain a core tensor, a brain parcellation factor matrix, and a participant factor matrix,

iii) estimate the other session’s participant factor matrix based on the decomposition of the given session,

iv) obtain an identifiability matrix by computing pairwise Pearson’s correlation between the rows of both participant factor matrices, and

v) calculate the matching rate for the obtained identifiability matrix. A schematic representation of our framework is presented in

Figure 1.

In the following section, we discuss how matching rate is affected by the rank of the decomposition, parcellation granularities, the scanning length of fMRI conditions, and under within- and between-condition scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C, A.M.E.G, J.G; methodology, V.C, M.L., J.H., A.M.E.G, J.G; formal analysis, V.C, A.M.E.G, J.G;; investigation, V.C, M.L., J.H., A.M.E.G, J.G; data curation, V.C, M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, V.C, A.M.E.G, J.G; writing—review and editing, V.C, M.L., J.H., A.M.E.G, J.G; supervision, A.M.E.G, J.G; funding acquisition J.H and J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.