People shuttered in the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing social isolation led to reports of stress, anxiety, and depression (Gibbons et al., 2023). To cope with psychological distress, many isolationists turned to alcohol consumption for temporary emotional relief (Czeisler et al., 2020), which typically led to momentary emotional relief in a one-step forward and two-steps back direction (Czeisler et al., 2020). The fading affect bias (FAB) manifests when unpleasant event affect fades faster than pleasant event affect for autobiographical event memories. The FAB is negatively related to many non-adaptive outcome measures, such as depression (e.g., Skowronski et al., 2003), and positively related to adaptive outcome measures, such as self-esteem (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2017). This research is the basis of the FAB being considered as a healthy coping outcome/mechanism (Ritchie et al., 2014). The FAB has also been examined in many contexts, ranging from alcohol (Gibbons et al., 2013), abuse (Crouch et al., 2022; Skowronski et al., 2016), and marijuana (Pillersdorf & Scoboria, 2019) to relationships (Gibbons et al., 2021; Zengel et al., 2019), false memories (Gibbons et al., 2022), and problem-solving (Gibbons et al., 2024). In the context of alcohol, Gibbons et al. (2013) found that the negative relation between FAB and alcohol consumption was stronger for non-alcohol events than alcohol events, and we took the opportunity in the current study to again examine the FAB in the context of alcohol, but, this time, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

1. Alcohol, Negative Emotions, and Coping

Walker et al. (2011) found that individuals who thought they were consuming alcohol perceived facial expressions as happy, which suggests that alcohol consumption can lead to positive perceptions. However, most studies have demonstrated undesirable consequences of alcohol consumption on cognition and emotion. Specifically, alcohol consumption and dependency are connected to poor memory and cognition, which can follow a single night of hard drinking, and these effects are exacerbated by stressors (McKinney & Coyle, 2007). Alcohol-induced memory failures involve effortful memory processes, like episodic memory (Tracy & Bates, 1999), “blackouts” (White, 2003), and impaired recall (Wetherill & Fromme, 2011), which can cause anxiety, shame, and, especially, regret as frequent consequences of alcohol consumption and intoxication (Jones et al., 2020; Pederson & Feroni, 2018). Alcohol consumption can also lead to guilt and embarrassment (Fjær, 2015), due to regrettable outcomes (Geusens & Vranken, 2021) and moral failures, such as unplanned sexual experiences (Orchowski et al., 2022).

Campos-Melady and Smith (2012) attempted to determine if alcohol consumption and emotions were implicitly connected using a Lexical Decision Task (LDT) with 78 female student participants. The researchers found that participants who showed strong connections between alcohol words and negative emotion words reported higher alcohol consumption frequency than participants who did not show the same association, and this effect was particularly strong for women who drank alcohol frequently to avoid conflict. As the reported alcohol consumption preceded the study’s initiation, these results suggested that alcohol consumption created connections to negative emotions. In a review, Kushner and Anker (2019) concluded that alcohol use disorder (AUD) can neurobiologically cause emotional dysregulation and increase negative emotions and drinking to cope (DTC).

Conversely to research showing that alcohol consumption leads to undesirable emotions, other research demonstrated that undesirable emotions elicit imbibement and impulsivity moderates these relations. For example, Herman and Duka (2019) discovered that negative emotions led to both alcohol use and dependency, and these relations increased with impulsivity. In a longitudinal study, Pardini et al. (2004) demonstrated that depressed emotions positively predicted alcohol consumption in boys with good inhibitory control, whereas aggression and fearlessness positively predicted alcohol use in boys with moderate/low inhibitory control.

Instead of determining causal relations, other research established the relations between alcohol consumption and emotion regulation problems/emotion dysregulation. For example, Schick et al. (2019) tested 395 participants and found that alcohol consumption was related to emotional dysregulation of positive emotions measured by impulsivity, non-acceptance, and depression symptom severity. Similarly, Gruber et al. (2011) found that alcohol use/abuse was associated with dysregulation of positive emotions, and Dvorak (2014) showed that alcohol-related consequences were positively associated with emotional regulation problems. Other researchers demonstrated that dysregulation of positive affect predicted hazardous drinking (Baker et al., 2004) and alcohol abuse in college students (Simons et al., 2005), and Weiss and colleagues (2018) displayed that regulation difficulties for positive emotions predicted drug misuse and alcohol dependence in 311 college students. Based on the responses of 132 college students who qualified as hazardous drinkers, Paulus et al. (2021) found that positive emotion regulation difficulties were related to alcohol problems. Rather than focusing on emotion regulation problems in general or positive emotion dysregulation, Kober (2014) investigated and found a link between the dysregulation of negative emotions and alcohol use/abuse.

In contrast to studies connecting alcohol consumption and emotion dysregulation, other studies have related alcohol to guilt, stress, and stressful situations. For example, Grynberg et al. (2017) found that alcohol dependency was related to high levels of guilt. In addition, Wang and Chen (2015) found that negative emotions mediated the relationship between stress and alcohol dependence. Similarly, Schumm and Chard (2012) uncovered a strong correlation in military soldiers and veterans between alcohol consumption and military stress, which increased with posttraumatic experiences. In addition, Buchmann et al. (2010) found, in 320 participants ages 15 to 19 years old, higher alcohol use during stressful life events (SLE) in the previous 4 years among participants who started drinking alcohol earlier than participants who began alcohol consumption later in their lives. Similarly, Blomeyer et al. (2011) found that early age of first drinks (AFDs) and high SLEs in the 3 years prior to the study were related to high alcohol consumption for 306 participants who completed structured interviews. Together, the stress results suggest that alcohol consumption is used as a coping mechanism for stressful events, and this effect is intensified for individuals who consume their first alcoholic beverage at an early age. Regardless of stress levels, however, alcohol consumption early in life has been associated with future drinking problems in adulthood (Caetano et al., 2014; York et al., 2004).

2. The Fading Affect Bias (FAB)

The FAB is a healthy outcome in autobiographical memory in which pleasant event affect fades slower than unpleasant event affect (Walker et al., 2003). Early research on this area demonstrated that participants recalled more pleasant than unpleasant autobiographical event memories (Jersild, 1931; Meltzer, 1930, 1931; Watters & Leeper, 1936), and emotional affect faded more quickly for unpleasant than pleasant events (Cason, 1932). Both these findings were replicated by Holmes (1970) and Walker et al. (1997), but Walker and colleagues also showed that the differential fading of affect for emotional autobiographical event memories increased with retention intervals, including 3 months, 9 months, and 4.5 years. Using Taylor’s mobilization-minimization hypothesis, Walker et al. accounted for their results, suggesting that biological, social, and cognitive resources were activated by unpleasant events and reduced the harmful effects of those events. The FAB occurs from 12 to 24 hours and it remains stable for up to 3 months (Gibbons et al., 2011), and it was not different for 8 to 12-year-old children and college students (Rollins et al., 2018). In contrast, Gibbons and Rollins (2021) found a smaller FAB for college students than 68 to 94-year-olds and a similar finding was discovered by Marsh and Crawford (2024).

Additional research supported the FAB as healthy, because FAB is negatively associated with non-adaptive variables and positively associated with adaptive variables. Non-adaptive variables are unhealthy, negative, unpleasant, undesirable, and unwanted, whereas adaptive variables are healthy, positive, robust, and wholesome (i.e., Hoehne & Zimprich, 2025). The non-adaptive variables examined in relation to the FAB in the literature include dispositional mood (Ritchie et al., 2009), depression, anxiety, and stress (Gibbons et al., 2017; Gibbons & Lee, 2019; Walker et al., 2014), immature death attitudes (Gibbons et al., 2018), and engagement in social media (Gibbons et al., 2017). Additional unhealthy variables included eating disorder symptoms (Ritchie et al., 2019; Skowronski et al., 2016), parental risk of physical abuse (Crouch et al., 2022; Skowronski et al., 2016), and marijuana consumption (Pillersdorf & Scoboria, 2019).

The adaptive variables examined in relation to the FAB included grit (Gibbons et al., 2023; Walker et al., 2020), social disclosures (Ritchie et al., 2006; Skowronski et al., 2004; Walker et al., 2009), social disclosures with a responsive listener (Muir et al., 2015; Muir et al., 2019), mature death attitudes (Gibbons et al., 2016), along with positive religious coping and spirituality (Gibbons et al., 2015). The FAB has also been positively related to self-esteem (Gibbons et al., 2017; Gibbons et al., 2021), partner esteem (Gibbons et al., 2021), and several relationship variables, such as relationship-related satisfaction and confidence (Gibbons et al., 2021; Zengel et al., 2019). Based on the findings that FAB did not differ across cultures (Ritchie et al., 2014), Ritchie et al. (2014) stated that the FAB may be an evolutionary mechanism produced by biological, cognitive, and emotional resources that manifest to reduce the adverse effects of unpleasant event memories. The function of the mobilization-minimization effect is to enhance an individual’s self perceptions by putting unwanted events in perspective, which propels individuals to seek out and avoid pleasant and unpleasant experiences, respectively (Ritchie et al., 2014; Sedikides & Alicke, 2019).

The FAB has been examined in many contexts, ranging from religion (Gibbons et al., 2015; Gibbons et al., 2021), relationships (Gibbons et al., 2021; Zengel et al., 2019), and US Presidential elections (Gibbons et al., 2020; Gibbons et al., 2024) to social media (Gibbons et al., 2016), video games, marijuana (Pillersdorf & Scoboria, 2019), and alcohol (Gibbons et al., 2013). These studies provided a variety of expected findings. For example, the positive relation between FAB and positive religious coping was stronger for religious than non-religious events (Gibbons et al., 2015), larger for some religions, such as Buddhism and Judaism, than for other religions, such as Christianity (Gibbons, Lee, et al., 2021), and smaller for social media events than non-social media events (Gibbons et al., 2017). The FAB was also smaller for college students than elderly individuals (Gibbons & Rollins, 2021; Marsh & Crawford, 2024). In the context of relationships, Zengel et al. (2019) found that securely attached individuals exhibited a significant FAB, whereas insecurely attached individuals did not demonstrate a significant FAB, and Gibbons et al. (2021) showed that the positive relation between FAB and partner esteem was stronger for relationship events than non-relationship events (Gibbons et al., 2021).

In the context of US Presidential elections, the positive relation between FAB and conservatism was stronger for political events (including the presidential elections) than non-political events for the 2016 US Presidential election (Gibbons et al., 2000) and weaker for political events than non-political events for the 2020 US Presidential election (Gibbons et al., 2024). In the first FAB study with objective memory measures, false memories for social media events and non-social media events were negatively related to FAB for those events (Gibbons et al., 2022). In the context of problem-solving, high levels of positive problem-solving beliefs combined with high levels of unhealthy variables (i.e., depression) to positively predict the FAB (Gibbons et al., 2024). The FAB was also higher for non-marijuana events than marijuana events (Pillersdorf & Scoboria, 2019). Relatedly, and importantly for the current study, the FAB was larger for non-alcohol events than alcohol events for participants who consumed low levels of alcohol (Gibbons et al., 2013).

Although the FAB was smaller for video game events than non-video game events, as expected, it was positively predicted by high levels of both depression and internet addiction (Gibbons & Bouldin, 2019). A gamer-generated explanation for the video game finding suggested that individuals addicted to internet games experience frustration and depression when learning a new game, but they also enjoy the challenge of that new game. When the gamers increase their skills and expertise for that game, they experience pride and boredom (i.e., low FAB) and move on to another game. The novel findings in the videogame and FAB study were conceptually replicated in a study comparing the relation of the FAB to COVID-19 anxiety across events involving and not involving COVID-19. Specifically, several unhealthy variables, including hypochondria, neuroticism, time spent ruminating over and recalling COVID-19, negative PANAS (current negative affect), and general anxiety, combined with COVID-19 anxiety to produce strong emotional regulation in the form of high FAB (Gibbons et al., 2024). Gibbons and colleagues (2024) explained that the experience of high COVID-19 anxiety helped people adapt to and come to expect other unhealthy emotional states, such as general anxiety. The unexpected results for video games and the COVID-19 pandemic set up the potential for unexpected results in the current study examining the FAB in the context of alcohol.

3. The Current Study

The alcohol literature found that alcohol is typically related to undesirable, unhealthy, and non-adaptive variables (e.g., Geusens & Vranken, 2021; Jones et al., 2020; Kushner & Anker, 2019; McKinney & Coyle, 2007; Orchowski et al., 2022; Paulus et al., 2021; Pederson & Feroni, 2018; Schick et al. 2019). Similarly, the autobiographical memory literature showed that unpleasant event affect fades faster and more than pleasant event affect (Walker et al., 1997), which is called the fading affect bias (FAB), and this phenomenon is positively related to healthy/adaptive variables, such as self-esteem (Gibbons et al., 2017; Gibbons et al., 2021) and negatively related to unhealthy/non-adaptive variables, such as anxiety, depression, and stress (Gibbons et al., 2017; Gibbons & Lee, 2019; Walker et al., 2014). For these reasons, the FAB has been considered as a healthy coping mechanism/outcome that helps people maintain positive perceptions and seek pleasant experiences as well as avoid unpleasant ones (Ritchie et al., 2014). The FAB has been investigated in various contexts with one of them being alcohol, which showed that the FAB was larger for non-alcohol events than alcohol events for low alcohol consumers in the form of three-way interactions (Gibbons et al., 2013). In addition, and much like several other studies, rehearsals involving both thinking and talking mediated the complex interaction effects (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2015). Therefore, we expected in the current study to find robust FAB effects that were positively predicted by adaptive variables and negatively predicted by non-adaptive variables. We also expected to find larger FAB for non-alcohol events than alcohol events for low alcohol consumers, and we expected this interactive effect to be mediated by rehearsals involving both thinking and talking.

4. Method

4.1. Participants

The ultimate sample was collected using Qualtrics, a platform made accessible through SONA, which included 370 individuals in the United States. All participants were 18 years of age or older with an average age of 36.63 years (SE = 0.22). The study sample was primarily Caucasian (75.4%), Christian (83.9%), male (56.2%), and heterosexuals (75.4%). The study obtained IRB approval (IRB# 1587783-2, approved initially on April 17 of 2020 and again on July 6 of 2021 in a continued review). The study included a briefing, signed consent, and debriefing, in accordance with APA (2023) ethical guidelines.

4.2. Materials and Measures

The materials contained a consent form, which included a briefing, a general description of the procedures, in addition to contact information for the principal investigator, counseling services, and the IRB chair; consent was obtained once students moved past the page with the consent statement. The questionnaires included an adaptive version of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Quantity and Frequency Questionnaire (NIAAA, 2005), the 40-item Mini Markers (Big Five; Saucier, 1994), targeting the measurement of neuroticism, the Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ; Schulze & Jones, 2000), as well as a general demographic questionnaire, which assessed information such as race, age, religion, sex, and sexual orientation. These demographics were further analyzed with questionnaires, including the 8-item spirituality scale (Parsian & Dunning, 2009) and the 4-item religiosity scale (Rowatt et al., 2009). Additionally, the questionnaires included dimensions of individual emotion, assessed via the 28-item Brief Cope scale (Carver, 1997), the 20-item positive and negative affect schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), and the the 10-item Grit scale (Duckworth & Quinn; 2009). The questionnaires also included an event survey. For each event recalled, participants were asked to include the date of event occurrence, a short event description (at least eight words), the initial affect felt during the event occurrence, and the final affect felt (currently/at test). Participants were also prompted to include a rehearsal rating (social and mental) scaled from 0 (never/infrequently) to 6 (always/very frequently), as well as a drunkenness rating ranging from 1 (Not drunk) to 7 (Very drunk).

Modified National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Quantity and Frequency Questionnaire. The alcohol questionnaire is an adjusted version of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) Quantity and Frequency Questionnaire (NIAAA, 2005), which was utilized to estimate the average quantity of alcoholic beverages that participants’ consumed weekly. The questionnaire defines an alcoholic drink as one 5 oz glass of wine, one 12 oz can of beer, or one 1.5 oz shot of 80-proof liquor, in accordance with the drink equivalents standard set by the NIAAA (2005). The quantity of beverages for each day across one week were summed. Cronbach’s alpha for the Modified NIAAA Quantity and Frequency questionnaire was .878.

Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ). The Desire for Alcohol Questionnaire (DAQ) is a 14-item questionnaire that assesses one’s desire to consume alcohol (Schulze & Jones, 2000). The items are scored ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) using a 5-point Likert-type scale. An example of an item from the questionnaire is “I thought drinking made me feel less tense.” Cronbach’s alpha for the DAQ was .935.

The 40-item Mini Markers scale. The brief version of the Big Five Personality Factors was used as the first psychological measure in this study, also known as the 40-item Mini Markers Scale (Saucier, 1994). This item is designed to measure a participants’ openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. For the scope of this study, however, only neuroticism was used. This sub-questionnaire lists various self-descriptive terms (e.g., trustful, steady, careful, bold). Participants were asked to rate the extent to which they felt these terms described themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (extremely inaccurate) to 9 (extremely accurate). Two items required reversed scoring, and then average neuroticism was calculated with high scores indicating high neuroticism. Cronbach’s alpha for neuroticism was .773.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS). The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) is a 20-item questionnaire, which measures positive and negative affect and the extent to which these emotions have been felt by the participant in the last hour. The questions included in the PANAS measurement range from 1 (slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) on a 5-point Likert-type scale. One example question is “nervous” or “determined.” The scale assesses positive and negative affect (e.g., excited, distresses, strong) by asking participants to self-report how much they feel certain emotions in the past few hours. The Cronbach’s alphas for positive PANAS and negative PANAS were .867 and .930, respectively.

Brief Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Survey (DASS-21). The brief Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was completed by participants to measure self-reported depression, anxiety, and stress, as past FAB research has shown a negative relationship between these variables and the FAB (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2024). The questionnaire contained statements related to depression, anxiety, and stress, prompting participants to rate the strength in which the statement applied to themselves with scores ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the time). Particular statement items pertain to the emotions of anxiety, stress, or depression, which were added and scored with low scores suggesting low levels of the related emotion. An example of a statement on the questionnaire is “I felt that life was meaningless.” The item scores were averaged and Cronbach’s alpha for the depression portion of the DASS-21 scale was .869. Cronbach’s alpha for the stress portion of the DASS-21 scale was .877. Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety portion of the DASS-21 scale was .848.

Brief COPE. The Brief COPE questionnaire asks participants to reflect on their own general coping strategies (Carver, 1997). The scale uses a 5-point Likert-type response scale for 28 items, with a range of 1 (I haven’t been doing this at all) to 5 (I’ve been doing this a lot). Examples of coping items included “I turn to work or other activities to take my mind off things” and “I get emotional support from others.” Cronbach’s alpha for the Brief Cope was .864.

Spirituality Questionnaire. The Spirituality Questionnaire examines participants’ level of spirituality with an 8-item scale (Parsian & Dunning, 2009). Participants were asked to express the degree to which they agreed with statements regarding various spiritual practices or beliefs. A 6-point Likert-type response scale was used, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). The questionnaire had items, such as “I experience a deep communion with God” and “I try to strengthen my relationship with God.” The score average was calculated, and high scores indicated high levels of spirituality. Cronbach’s alpha for spirituality was .930.

Religiosity. The General Religiousness Scale (used by Gibbons et al., 2015) consists of four items that assess different aspects of a person’s religious involvement. It evaluates how religious an individual considers themselves, along with how often they attend religious services, pray, and read sacred texts. Responses are rated using various scales, including a 1 (not at all religious) to 4 (very religious) scale for self-rated religiosity, a 1 (never) to 9 (several times a week) scale for attendance at services, and a 1 (never) to 6 (several times a day) scale for prayer and scripture reading frequency. The z-scores for each of the four items was calculated and they were averaged for an overall religiosity score. Cronbach’s alpha for religiosity was .897.

Grit. The Grit Scale (Duckworth et al., 2009) is a questionnaire containing 10 grit-related statements. An example statement is “I have overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge.” Participants self-reported to what extent they resonated with each statement, using a 5-point Likert-type scale. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). The even -numbered items on the scale were asked in the reverse to the way that the odd-numbered items were asked. Furthermore, the responses to the odd-numbered questions were reversed-scored, and the average for the entire scale was calculated. The Cronbach’s alpha for grit was .681.

Event description, initial and current affect, rehearsal frequency, drunkenness, and religious coping. The questionnaire involved eight events: two unpleasant events involving alcohol, two unpleasant events not involving alcohol, two pleasant events involving alcohol, and two pleasant events not involving alcohol. Participants were directed to describe an autobiographical memory pertaining to each of the eight event types, as well as rate the different events. The order of event rankings were counterbalanced using a Latin square. By crossing initial event affect and event type, each event type required two events. Participants dated, described, and rated each event for both initial and current event affect, rehearsals, drunkenness, and religious coping, continued the response-type for the second event, and then they proceeded to the next type of event in the Latin square. Each event was rated for initial and current affect on a single-item scale ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to +3 (very pleasant), including a score of 0 (neutral). The initial rating for pleasant events was positive, and the initial rating for unpleasant events was negative. Participants also rated the frequency they both thought and talked about each event using a single-item scale ranging from 0 (never/infrequently) to 6 (always/very frequently). Additionally, each positive and negative alcohol event was rated on a drunkenness scale ranging from 1 (Not drunk at all) to 7 (Very drunk). Participants then rated their positive and negative religious coping activities first for their negative non-alcohol events and then for their negative alcohol events. Positive religious coping includes 7 items, for example “looked for a stronger connection to God”, and negative religious coping includes 7 items, for example “wondered whether God abandoned me”. The response scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal).

Fading affect. The fading affect was calculated by subtracting the current affect from the original affect for initially pleasant events. The fading affect was calculated by subtracting the original affect from the current affect for initially unpleasant events. These calculations maintained positive fading affect measures across pleasant and unpleasant events; therefore, a large fading affect score suggested a large degree of fading, and a small fading affect score suggested very little fading. These calculations ensured that positive fading affect correlated with event affect reduction over time, in contrast negative fading affect correlated with event affect increasing over time. Initially, we examined fading affect for the 2960 events provided by participants. However, some events did not provide affect ratings or descriptions, or were incorrectly rated, which resulted in 2207 usable events.

4.3. Procedure

Participants signed up for the study during the COVID-19 pandemic, using the online platform Qualtrics. The briefing included informing participants that the study was examining recollection of pleasant and unpleasant event memories involving and not involving alcohol, drunkenness ratings for any alcohol events, rehearsal ratings, and any religious coping utilized for these events. Participants were told that the experimental procedure should not arise in any known risks to them, as they should only provide events that do not elicit emotional pain. Following the briefing, participants received a consent form, which stated that their consent was being sought for research study participation, their participation was entirely voluntary, and at any time, they may stop the study without any negative repercussions. We told participants that the information that they provided was confidential, their data were encrypted, and the results would only be examined by research assistants or the Principal Investigator of the study. The contact information of the Principal Investigator and the Chair of the IRB were given to participants, as well as the contact information of the university counseling center, should they experience any emotional discomfort. Participants received all information in the briefing and signed the consent form before beginning the procedure.

Once the briefing and consent forms were complete, participants answered a selection of online questionnaires that included general demographics, alcohol-use consumption, personality, mood, general coping strategies for life events, spirituality, and religiosity. Continuing on with the event questionnaire, participants recalled an autobiographical memory, wrote a short description including information about the event, continuing on to repeat the same procedure for another event of the same type. The presentation of the four kinds of types was controlled using a Latin square, which included pleasant and unpleasant alcohol and non-alcohol events. Participants were informed that non-alcohol events did not involve alcohol, whereas alcohol events involved alcohol-use, consumed by the participant or another person who was involved in the event. The participants were told that the events had to involve the participant and must be described from their perspective.

Each event required participants to record the date that the event occurred (as specific as feasible), and a brief, four-line, event description including as much detailed information as the participant felt comfortable disclosing. Participants then recorded an initial/original emotion for the feelings they experienced at the time of the event. Participants were told that pleasant events should be initially rated using a positive number ranging from 1 (mildly pleasant) to 3 (very pleasant), whereas unpleasant events should initially be rated using a negative number ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to -1 (mildly unpleasant).Participants were instructed to rate the current (at test) feelings experienced when recalling the event, rating the current emotion on a scale ranging from -3 (very unpleasant) to +3 (very pleasant). Participants then recorded the frequency they thought and/or talked about the event on a scale, with a rating range of 1 (never/infrequently) to 7 (always/very frequently). Next, participants rated their drunkenness for pleasant and unpleasant alcohol events, and their positive and negative religious coping for unpleasant alcohol and non-alcohol events. Lastly, participants were given a debriefing form, instructed to read it in its entirety, and then were asked if they had any questions. Following the debriefing, participants were given credit through SONA.

5. Analytic Strategy

We examined each event as the unit of analysis, and we removed and unusable data. The current study included 2960 initial events in the analyses. We first tested initial affect intensity in a 2 (Initial Event Affect) x 2 (Event Type) completely between-groups design with initial event affect (pleasant or unpleasant) and event type (non-alcohol or alcohol) as the independent variables. In addition, we used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) to statistically evaluate initial affect intensity and fading affect across the two independent variables. We conducted independent groups t-tests to examine significant interactions. We then employed the Process macro via IBM SPSS (Hayes, 2022) to test for two-way and three-way interactions involving initial event affect, event type, and continuous variables. The indirect effect, standard error, t-value, p-value, 95% CI lower- and upper-estimates, and effect size were all reported for every statistically significant interaction produced by the Process macro.

We used Model 1 of the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, across initial event affect, x, conditional upon levels of self-reported individual difference variables, w. These variables included rehearsals, positive PANAS, Brief Cope, spirituality, positive religious coping for alcohol events, positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, religiosity, drunkenness for positive alcohol event 1, drunkenness for positive alcohol event 2. These variables also included drinking hours, DAQ, negative PANAS, stress, negative religious coping for alcohol events, negative religious coping for non-alcohol events, drunkenness for negative alcohol event 1, and drunkenness for negative alcohol event 2. We controlled for clustered data by controlling for the participant variable in each model. The Johnson-Neyman technique indicated where the FAB was weak or strong for a continuous measure (Preacher et al., 2006).

For any significant three-way interactions, we again utilized the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, among four categories of events across the spectrum of the previously-listed individual difference variables. Specifically, Model 3 enabled the specification of the two-way interaction between initial event affect, x, and event type, w, conditional upon the aforementioned continuous predictor variables, m. Fading affect was evaluated across the continuous variables for each of the four events (pleasant and unpleasant alcohol and non-alcohol) using the Johnson-Neyman technique. The goal of these analyses was to indicate the exact value for each continuous variable showing where the effect of event type on FAB was large and small.

We also evaluated talking and thinking rehearsals as a possible mediator of any significant three-way interactions with the Process macro. Specifically, we examined rehearsal as a mediator of significant relations between initial event affect and fading affect (i.e., FAB) across event type and individual difference variables that combined to create significant three-way interactions. Process Model 11 enables the evaluation of the mediators for significant three-way interactions. We hypothesized that rehearsal would mediate the interaction of initial event affect (unpleasant vs. pleasant), x, event type (non-alcohol and alcohol), z, and predict fading affect, y, across levels of individual difference variables, w, such that effect of x*w*z affects y and occurs through event rehearsal frequency, m. The conditional indirect effect of x*w*z on y through m, and the indirect effect of x on y through m at levels of the moderators, w and z, were reported. We also controlled for participants.

6. Results

6.1. Discrete Two-Way Interactions

The ANOVA for initial affect intensity produced heterogeneity, but this parametric assumption violation is not a problem if the sample sizes are relatively equal, defined by a ratio of largest to smallest sample sizes equal or less than 1.5 (Statistics Solutions, 2023). The sample size ratios calculated for initial event affect, event type, and cells created by crossing initial event affect by event type were all less than 1.5, and, therefore, relatively equal. The overall analysis of variance investigating initial affect intensity was statistically significant,

F(3, 2203) = 36.346,

p < .001, η

p2 = .047 (

Figure 1). Pleasant events (

M = 2.713,

SE = 0.015) were initially more intense than unpleasant events (

M = 2.449,

SE = 0.022),

F(1, 2203) = 99.535,

p < .001, η

p2 = .043, which does not support regression-to-the-mean as an explanation for FAB effects. The non-alcohol events (

M = 2.6222,

SE = 0.018) were initially more intense than the alcohol events (

M = 2.542,

SE = 0.020),

F(1, 2203) = 9.495,

p < .001, η

p2 = .004. The interaction was not significant (

F < 1.0 and

p > .6).

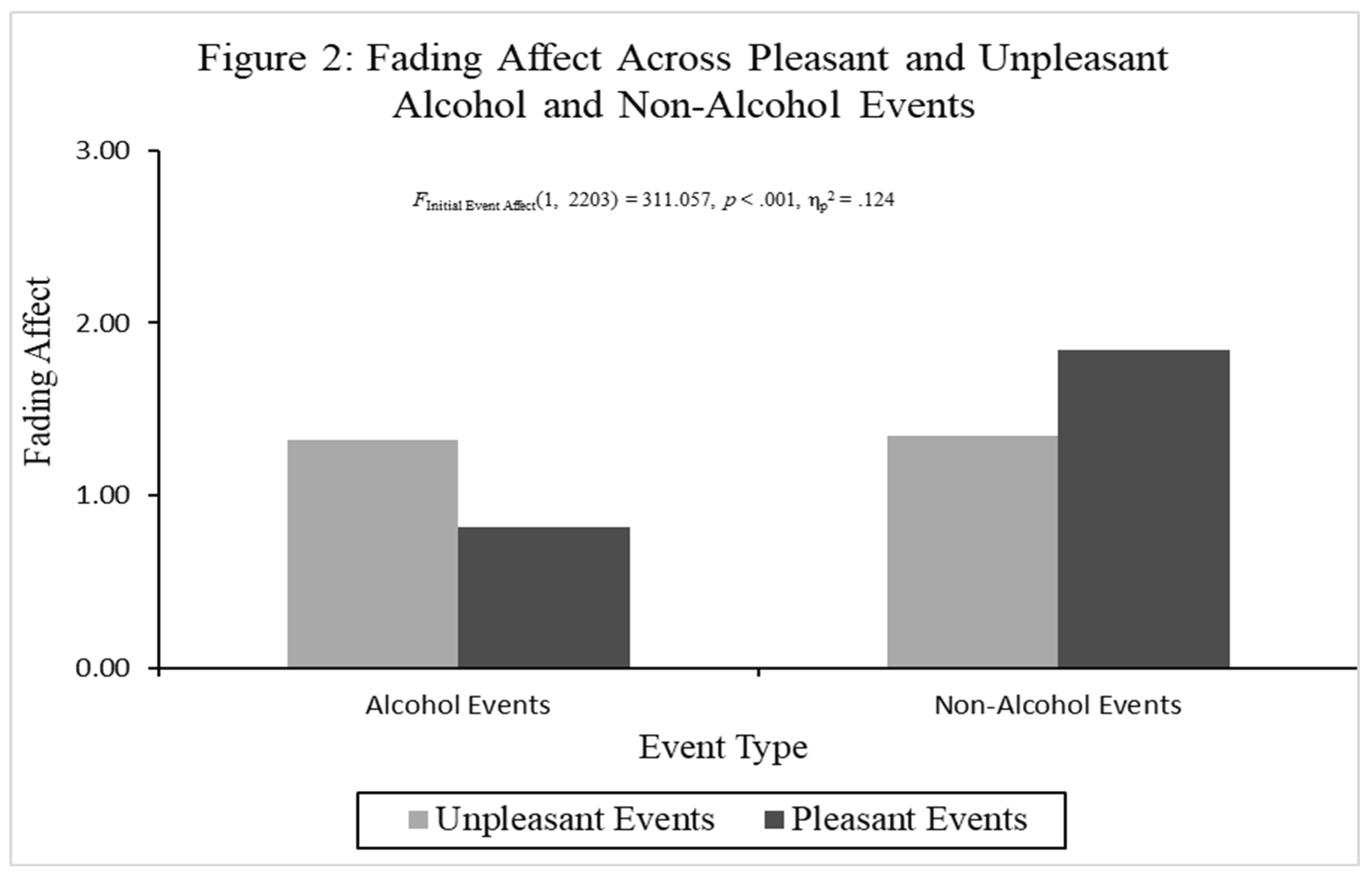

When analyzing the fading of affect as the dependent variable using ANOVA, we found heterogeneity, but it was not a problem for the same reasons mentioned previously for initial affect intensity. The overall analysis of variance investigating fading affect intensity was statistically significant,

F(3, 2203) = 104.166,

p < .001, η

p2 = .124 (

Figure 2). The affect for unpleasant events (

M = 1.847,

SE = 0.051) faded more than the affect for pleasant events (

M = 0.815,

SE = 0.029),

F(1, 2203) = 311.057,

p < .001, η

p2 = .124, which demonstrated a fading affect bias (FAB) effect. No other effects were significant (

Fs < 2.0 and

ps > .2).

6.2. Continuous Two-Way Interactions

We used Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) to examine whether individual difference variables predicted the FAB. These variables included rehearsals, positive PANAS, positive religious coping for alcohol events, positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, spirituality, religiosity, Brief Cope, drunkenness for positive alcohol event 1, and drunkenness for positive alcohol event 2. These variables also included drinking hours, DAQ, negative PANAS, stress, negative religious coping for alcohol events, negative religious coping for non-alcohol events, drunkenness for negative alcohol event 1, and drunkenness for negative alcohol event 2. Positive predictors of FAB included rehearsals, positive PANAS, spirituality, positive religious coping for alcohol events, religiosity, Brief Cope, positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, DAQ, grit, and average drinking hours per day. Negative predictors of FAB included negative religious coping for alcohol events, negative religious coping for non-alcohol events, and negative PANAS.

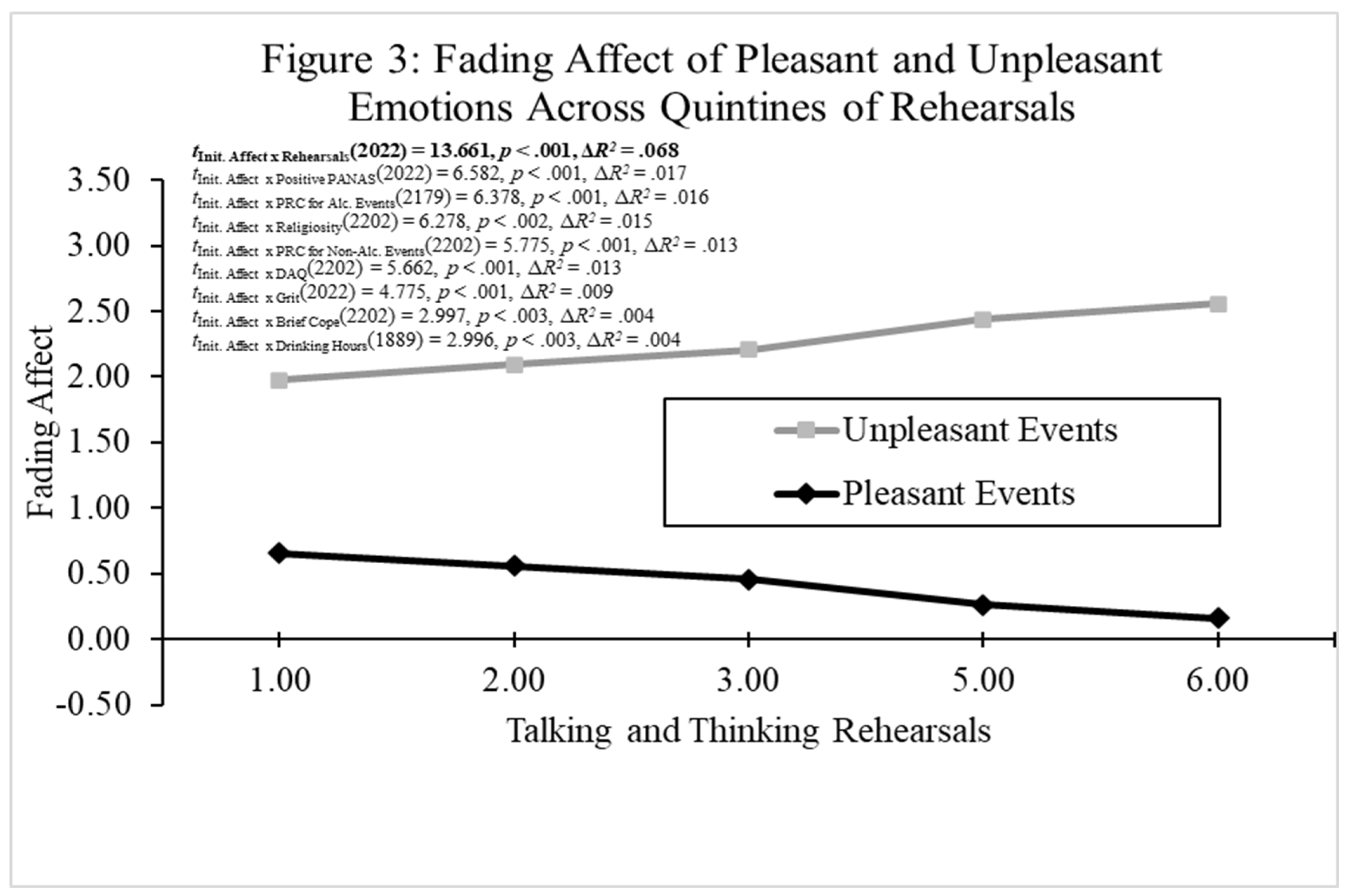

Positive predictors of FAB. When examining talking and thinking rehearsals, the main effects for initial event affect and rehearsals were significant. In addition, the results revealed a significant two-way interaction between rehearsals and initial event affect, B = 0.463 (

SE = 0.034),

t(2022) = 13.661,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.397, 0.530], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .068, and overall Model

R2 = .197,

p < .001 (

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect started significant and negative (larger pleasant fading affect than unpleasant fading affect) and decreased with rehearsal and was last significant at rehearsal levels of 1.722 (before the 10th percentile) and continued to decrease and was last negative at rehearsal levels of 2.200 (just after 10th percentile) and became positive (larger unpleasant fading affect than pleasant fading affect) at rehearsal levels of 2.500 and significant at rehearsal levels of 2.601 and increased from that point.

When examining positive PANAS, the main effects for initial event affect and positive PANAS were significant. In addition, the results demonstrated a significant two-way interaction between positive PANAS and initial event affect, B = 0.535 (

SE = 0.079),

t(2022) = 6.739,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.380, 0.691], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .018, and overall Model

R2 = .142,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with positive PANAS because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as positive PANAS increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the effect became significant at a positive PANAS score of 2.247 and increased from that point. When examining spirituality, the main effects for initial event affect and spirituality were significant. In addition, the results from Process Model 1 (Hayes, 2022) revealed a significant two-way interaction between spirituality and initial event affect, B = 0.258 (

SE = 0.039),

t(2202) = 6.582,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.181, 0.334], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .017, and overall Model

R2 = .141,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with spirituality because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as spirituality increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the effect became significant at a spirituality score of 2.817 and increased from that point.

When examining positive religious coping for alcohol events, the results showed a significant main effect of positive religious coping for alcohol events and a significant two-way interaction between positive religious coping for alcohol events and initial event affect, B = 0.358 (

SE = 0.056),

t(2179) = 6.378,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.248, 0.468], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .016, and overall Model

R2 = .139,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with positive religious coping for alcohol events because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as positive religious coping for alcohol events increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the FAB became significant at a positive religious coping for alcohol events score of 1.289 and increased from that point. When examining religiosity, the main effects for initial event affect and religiosity were significant. In addition, the results displayed a significant two-way interaction between religiosity and initial event affect, B = 0.417 (

SE = 0.066),

t(2202) = 6.278,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.287, 0.547], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .015, and overall Model

R2 = .140,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with religiosity because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as religiosity increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the FAB became significant at a religiosity score of -1.839 and increased from that point.

When examining positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, the main effect of positive religious coping for non-alcohol events was significant. In addition, the results revealed a significant two-way interaction between positive religious coping for non-alcohol events and initial event affect, B = 0.333 (

SE = 0.058),

t(2202) = 5.775,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.220, 0.446], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .013, and overall Model

R2 = .137,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with positive religious coping for non-alcohol events because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as positive religious coping for non-alcohol events increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the FAB became significant at a positive religious coping for non-alcohol events score of 1.220 and increased from that point.

When examining DAQ, the main effect of DAQ was significant. In addition, the results demonstrated a significant two-way interaction between DAQ and initial event affect, B = 0.386 (

SE = 0.068),

t(2202) = 5.662,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.252, 0.519], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .013, and overall Model

R2 = .137,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with DAQ because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and decreased for pleasant events as DAQ increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the FAB became significant at a DAQ score of 1.425 and increased from that point. When examining grit, the main effect of grit and initial event affect were significant. In addition, the results showed a significant two-way interaction between initial event affect and grit, B = 0.530 (

SE = 0.111),

t(2202) = 4.775,

p < .001, 95% CI [0.312, 0.748], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .009, and overall Model

R2 = .136,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with grit primarily because fading affect increased for unpleasant events and slightly decreased for pleasant events as grit increased. The Johnson-Neyman results showed that the FAB became significant at a grit score of 2.257 and increased from that point.

When examining Brief Cope, the main effects for initial event affect and Brief Cope were significant. In addition, the results displayed a significant main effect of Brief Cope and a significant two-way interaction between Brief Cope and initial event affect, B = 0.230 (

SE = 0.077),

t(2202) = 2.997,

p < .003, 95% CI [0.080, 0.381], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .004, and overall Model

R2 = .129,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB for this effect increased with Brief Cope primarily because fading affect increased for unpleasant events as Brief Cope increased. When examining average drinking hours each day, the main effects of initial event affect and drinking hours were significant. In addition, the results demonstrated a significant two-way interaction between drinking hours and initial event affect, B = 0.048 (

SE = 0.016),

t(1889) = 2.996,

p < .003, 95% CI [0.016, 0.079], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .004, and overall Model

R2 = .139,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 3). The FAB increased with average drinking hours per day primarily because fading of unpleasant affect increased as average drinking hours per day increased.

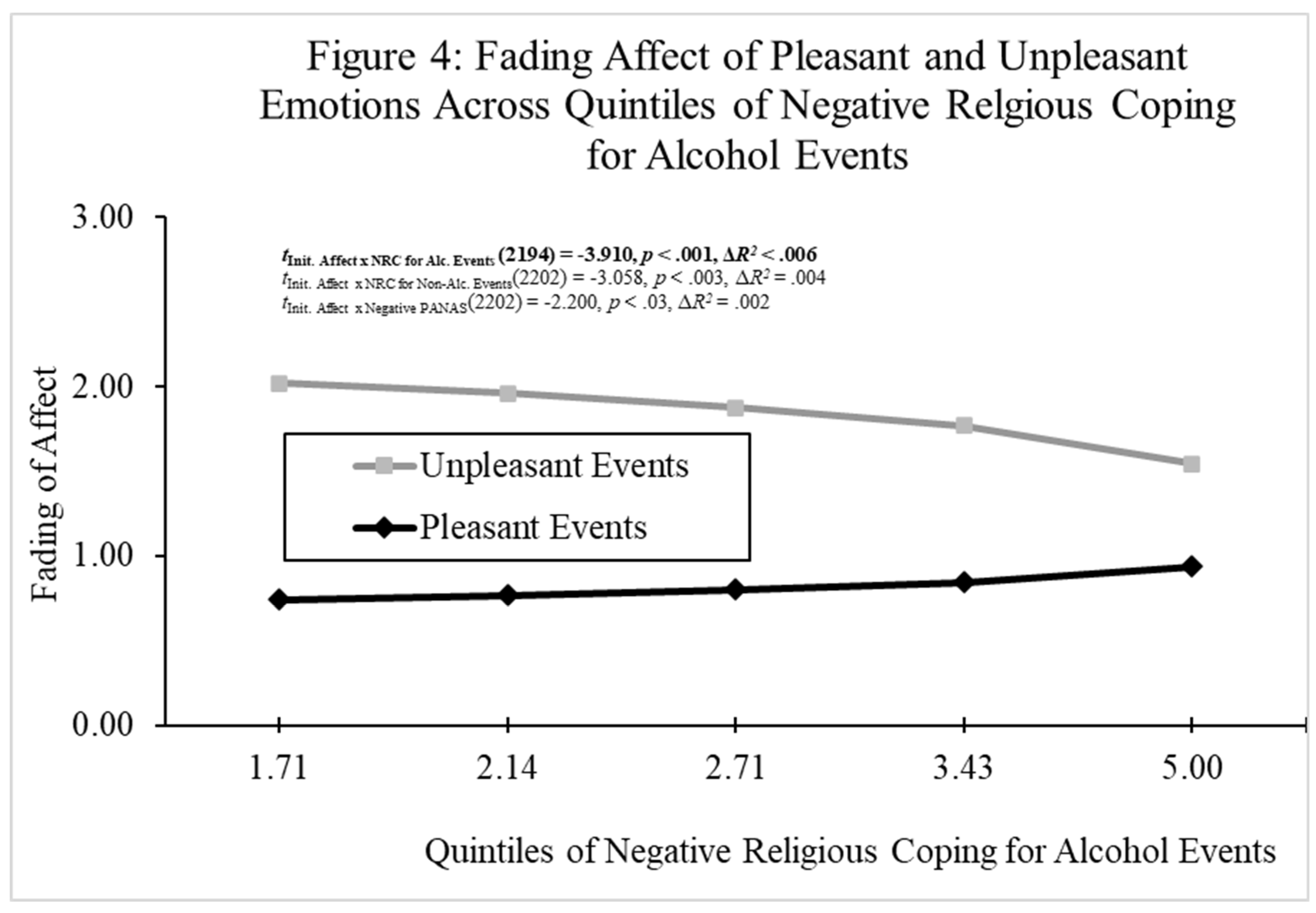

Negative predictors of FAB. When examining negative religious coping for alcohol events, the main effects of negative religious coping for alcohol events and initial event affect were significant. In addition, the results showed a significant two-way interaction between negative religious coping for alcohol events and initial event affect, B = -0.206 (

SE = 0.053),

t(2194) = -3.910,

p < .001, 95% CI [-0.309, -0.103], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) = .006, and overall Model

R2 = .130,

p < .001 (

Figure 4). The FAB for this effect decreased with negative religious coping for alcohol events because fading affect decreased for unpleasant events, but it also slightly increased for pleasant events as negative religious coping for alcohol events increased.

When examining negative religious coping for non-alcohol events, the main effects for initial event affect and negative religious coping for non-alcohol events were significant. In addition, the results displayed a significant two-way interaction between negative religious coping for non-alcohol events and initial event affect, B = -0.164 (

SE = 0.054),

t(2202) = -3.058,

p < .003, 95% CI [-0.269, -0.059], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .004, and overall Model

R2 = .128,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 4). The FAB for this effect decreased with negative religious coping for non-alcohol events primarily because fading affect decreased for unpleasant events, but it also increased slightly for pleasant events as negative religious coping for non-alcohol events increased. When examining negative PANAS, the main effects for initial event affect and negative PANAS were significant. In addition, the results revealed a significant two-way interaction between negative PANAS and initial event affect, B = -0.133 (

SE = 0.060),

t(2202) = -2.200,

p < .03, 95% CI [-0.251, -0.014], Model Δ

R2 (due to the two-way interaction) < .002, and overall Model

R2 = .127,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 4). The FAB for this effect decreased with negative PANAS only because fading affect increased for pleasant events as negative PANAS increased.

6.3. Continuous Three-Way Interactions: Predictors of FAB Across Event Type

To test for significant three-way interactions, we used the Process macro to examine fading affect, y, among several individual difference variables across event type (alcohol and non-alcohol). Specifically, Model 3 (Hayes, 2022) enabled the specification of the two-way interaction between initial event affect, x, and individual difference variables, m, while controlling for participant, conditional upon event type, w. The individual difference variables involved in significant three-way interactions included spirituality, positive PANAS, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events. We also used the Johnson-Neyman technique to detect where the FAB was stronger for one event type (e.g., alcohol) than for another event type (e.g., non-alcohol) across levels of an individual difference variable (i.e., spirituality) for one event type (e.g., alcohol) than for another event type (non-alcohol).

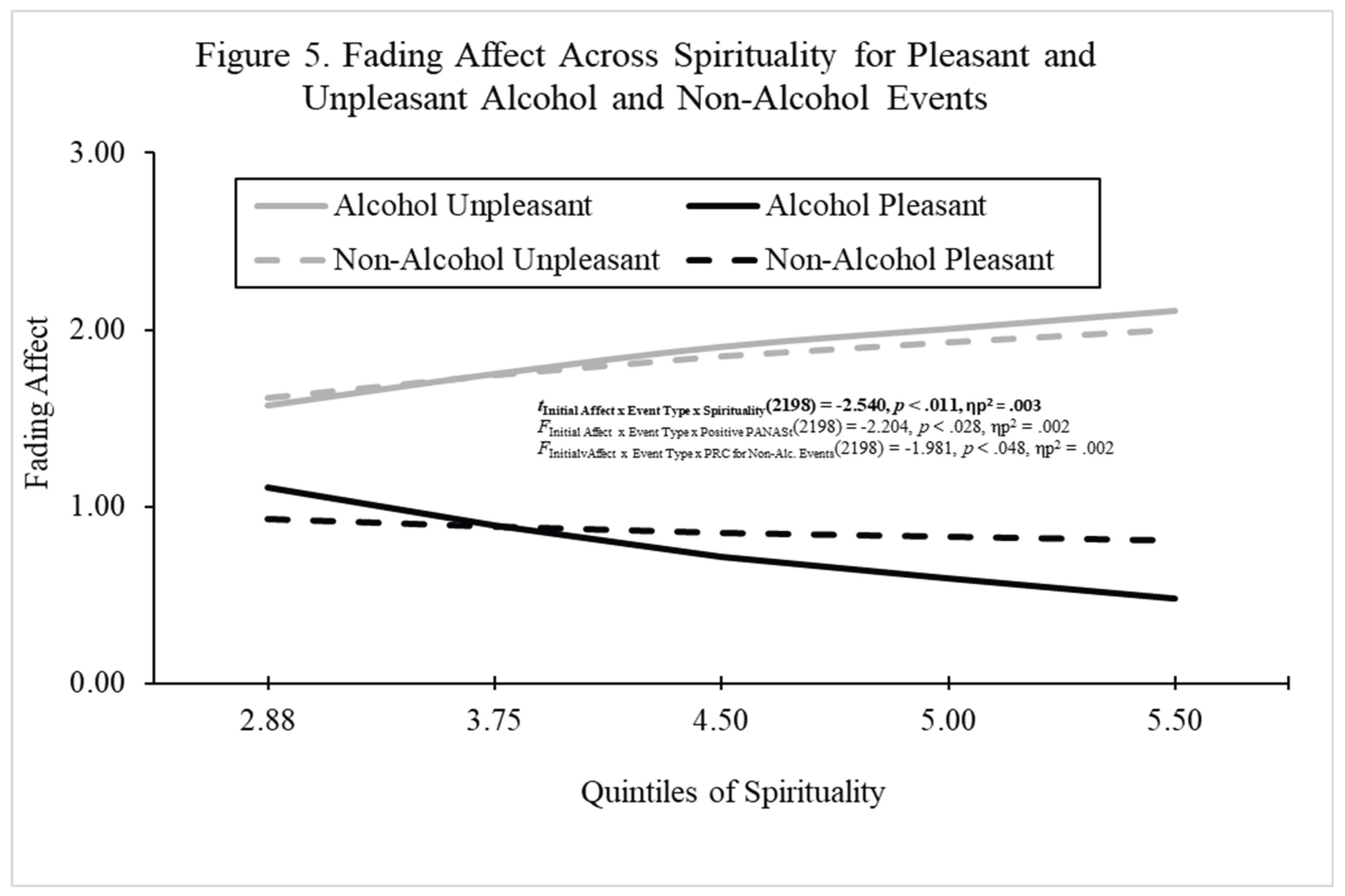

We examined the three-way interaction of initial event affect, spirituality, and event type while controlling for participants. The model revealed that all the main effects and all the two-way interactions were significant. Moreover, a significant three-way interaction was found between initial event affect, event type, and spirituality, B = -0.250 (

SE = 0.099),

t(2198) = -2.540,

p = .011, 95% CI [-0.444, -0.057], Model Δ

R2 (due to the three-way interaction) < .003, and overall Model

R2 = .144,

p < .001 (

Figure 5). The Johnson-Neyman values showed a significant positive relation between FAB and event type (FAB larger for alcohol events than non-alcohol events) at the lowest level of spirituality (1.000), and that relation reduced and was last significant at a spirituality level of 1.152. The relation became negative (FAB larger for non-alcohol events than alcohol events) at a spirituality level of 3.750 (25th percentile), significant at a spirituality level of 4.708 (between the 50th and 75th percentiles), and increased from that point.

We evaluated the three-way interaction of initial event affect, positive PANAS, and event type while controlling for participants. We discovered significant main effects of initial event affect and positive PANAS, as well as a significant initial event affect by positive PANAS interaction and an event type by positive PANAS interaction. Moreover, a significant three-way interaction was found between initial event affect, event type, and positive PANAS, B = -0.350 (

SE = 0.159),

t(2198) = -2.204,

p < .028, 95% CI [-0.661, -0.039], Model Δ

R2 (due to the three-way interaction) < .002, and overall Model

R2 = .144,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 5). The Johnson-Neyman values showed a non-significant positive relation between FAB and event type (FAB higher for alcohol events than non-alcohol events) at the lowest percentile of positive PANAS (1.300), which reduced and was last positive at a positive PANAS level of 3.150, which occurred just before the 25th percentile of positive PANAS. The relation then became negative (FAB was higher for non-alcohol events than alcohol events) at a positive PANAS level of 3.335 (just after the 25th percentile), and it became significant at a positive PANAS level of 4.004 (just before the 75th percentile) and increased from that point.

We investigated the three-way interaction of initial event affect, positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, and event type while controlling for participants. We found a significant main effect of positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, as well as significant two-way interactions between positive religious coping for non-alcohol events and both initial event affect and event type. More importantly, a significant three-way interaction was found between initial event affect, event type, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, B = -0.228 (

SE = 0.115),

t(2198) = -1.981,

p < .048, 95% CI [-0.454, -0.002], Model Δ

R2 (due to the three-way interaction) < .002, overall Model

R2 < .140,

p < .001 (i.e.,

Figure 5). The Johnson-Neyman values showed a non-significant positive relation between FAB and event type (FAB was higher for alcohol events than non-alcohol events) at the lowest percentile of positive religious coping for non-alcohol events (1.000), which reduced and was last positive at a positive religious coping for non-alcohol events level of 2.800 (before the 25th percentile). The relation then became negative (FAB higher for non-alcohol than alcohol events) at a positive religious coping for non-alcohol events level of 3.000, and it became significant at a level of 3.965, which occurred between the 50th and 75th percentiles of the continuous variable, and increased with the variable from that point.

6.4. Examining Rehearsals as Mediators of the Three-Way Interactions

Next, we examined and found the conditional indirect effects of initial event affect on fading affect across event type for spirituality, positive PANAS, and positive religious coping for alcohol and non-alcohol events through rehearsal ratings (talking and thinking) using the Process Model 11 (Hayes, 2022). The three-way interaction involving fading affect across initial event affect, event type, and spirituality was intervened by talking and thinking rehearsals at every quintile of spirituality. The three-way interaction involving fading affect across initial event affect, event type, and positive PANAS was intervened by talking and thinking rehearsals at every quintile of positive PANAS. The three-way interaction involving fading affect across initial event affect, event type, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events was intervened by talking and thinking rehearsals at every quintile of the continuous predictor.

7. Discussion

A robust FAB was found for alcohol and non-alcohol events, which replicates the findings of Gibbons et al. (2013). As expected based on the premise that the FAB is a healthy coping mechanism/outcome (Richie et al., 2014), the FAB was positively predicted by rehearsals, positive PANAS, spirituality, positive religious coping (for alcohol and non-alcohol events), religiosity, Brief Cope, and grit, which replicated past research (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2023; Gibbons et al., 2015; Gibbons et al., 2013; Walker et al., 2020). As expected, based on the same premise, the FAB was negatively predicted by negative religious coping for alcohol events, negative religious coping for non-alcohol events, and negative PANAS (e.g., Gibbons et al., 2015; Gibbons et al., 2023). Past research suggests that the evolutionary activation of biological, cognitive, and emotional tools produced the FAB as a coping mechanism to increase the integrity of pleasant memories and reduce the damaging effects of unpleasant memories (Richie et al., 2014). These positive and negative predictors of the FAB support the notion that the retention of pleasant autobiographical events over unpleasant events strengthens self-perception by motivating individuals to seek the former and avoid the latter (Ritchie et al., 2014; Sedikides & Alicke, 2019).

Unexpectedly, however, DAQ and average drinking hours per day positively predicted the FAB, and the FAB was not predicted by neuroticism, anxiety, depression, and stress when all these variables were expected to negatively predict the FAB. One possible explanation for the positive relation between alcohol consumption variables and FAB is that the data were collected during the pandemic. During this time, alcohol was heavily consumed as a coping mechanism for the stress produced by the isolation and constant threat of sickness and death (Cziesler et al., 2020). As for the lack of relations between unhealthy/non-adaptive variables and the FAB, these emotional traits and states may have become commonplace during the COVID-19 pandemic, and, consequently, did not predict the FAB. Gibbons and colleagues (2023) offered a similar explanation for the unexpected relations they found when examining the FAB for COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 events. Specifically, they found that unhealthy variables (hypochondria, neuroticism, anxiety, negative PANAS) positively predicted the FAB at high levels of coronavirus anxiety. The researchers suggested that experiencing hypochondria, neuroticism, anxiety, and negative PANAS may have prepared individuals to adapt to and emotionally thrive in the presence of the anxiety produced by the COVID-19 pandemic. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic was a strange event and time in our lives that changed the way we perceived the world around us and regulated our emotions.

Another unexpected “finding” was the lack of a three-way interaction involving the FAB, event type, and alcohol consumption in the current study, which was found by Gibbons et al. (2013). Specifically, participants who reported low alcohol consumption in the previous study demonstrated stronger FAB for non-alcohol events than for alcohol events, which did not replicate in the current study. The increased alcohol use during the pandemic may have shifted participant perceptions to viewing alcohol consumption as a healthy, emotion-regulating mechanism, unlike its previous conceptualization as a non-adaptive form of coping that could lead to hazardous outcomes in both the short-term and long-term (Campos-Melady & Smith, 2012; Dvorak, 2014; Gruber et al., 2011; Schick et al., 2019). Thus, the positive relationship between alcohol use and FAB may reflect non-adaptive/unhealthy coping strategies for managing pandemic-related stress. This interpretation aligns with previous findings that individuals often use alcohol to regulate negative emotions (Anker et al., 2016; Dvorak et al., 2014) and that such coping mechanisms can momentarily improve emotional processing or dampen negative affect (Baker et al., 2004). Given that FAB reflects a form of emotional regulation in memory (Walker & Skowronski, 2009), it is plausible that alcohol served to buffer emotional responses during the pandemic, thereby enhancing FAB scores despite its long-term risks.

We found three significant three-way interactions in the current study, involving the continuous predictors of spirituality, positive PANAS, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events. The significant three-way interaction between initial event affect, event type, and spirituality demonstrated that the relation between the FAB and event type (alcohol and non-alcohol) was predicted by spirituality levels. At the lowest level of spirituality, the FAB was larger for alcohol events than non-alcohol events. This effect weakened as spirituality increased, and the relation inverted and demonstrated a larger FAB for non-alcohol events than alcohol events in individuals reporting high levels of spirituality. Similarly, the significant three-way interaction involving initial event affect, event type, and positive PANAS displayed a higher FAB for alcohol events than non-alcohol events at low levels of positive PANAS. The strength of the effect decreased, inverted, became significant, and increased as positive PANAS levels increased, resulting in a higher FAB for non-alcohol events than for alcohol events at high levels of positive PANAS. The results demonstrated a similar pattern when examining the significant three-way interaction involving initial event affect, event type, and positive religious coping (PRC) for non-alcohol events. Like the other three-way interactions, the FAB was larger for alcohol events than non-alcohol events at low levels of PRC for non-alcohol events, but then the effect decreased in strength, inverted, became significant, and increased as levels of PRC for non-alcohol events increased. The FAB was larger for non-alcohol events than for alcohol events at high levels of PRC for non-alcohol events. These three complex interactions suggested that higher levels of spirituality, positive affect, and PRC for non-alcohol events predicted adaptive emotional responses to events in the form of FAB during the pandemic.

One possible explanation for the presence of the three-way interactions in the absence of other three-way interactions is that the three continuous variables may be particularly powerful coping tools that help individuals maintain a strong self-concept. For example, the research conducted by Parian and Dunning (2009) indicated that spirituality may help people with chronic health conditions manage their health and well-being. The researchers suggested that spirituality guides individuals to transcend their condition, find meaning, and feel inner peace. Based on the similar results for positive religious coping and positive PANAS as the results for spirituality, high levels of these variables may activate similar coping mechanisms, as they each contribute to an individual’s capacity to regulate emotion, devise meaning, and maintain psychological resilience under duress (Gibbons et al., 2015). The results of the current study may also reflect the pandemic’s role in heightening the relevance of internal, affective, and spiritual resources, while potentially limiting the impact of other coping strategies that are less accessible or less effective in socially restricted environments. Furthermore, the pandemic generated an increase in unhealthy emotions and psychological distress, such as anxiety, stress, and depression, as well as increased levels of suicidal ideation and substance abuse (Ettman et al., 2020). Therefore, spirituality, positive PANAS, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events could have enhanced self-concept (Gibbons et al., 2015; Parian & Dunning, 2009), guided the selection and activation of resources, thereby diminishing the powerful and unhealthy psychological states produced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

As expected, the combined talking and thinking rehearsal ratings mediated the three three-way interactions. These findings supported past research, showing that the combined rehearsal rating mediated complex effects (three-way interactions) in a variety of contexts, such as alcohol (Gibbons et al., 2013), religion (Gibbons et al., 2015), and video games (Gibbons & Bouldin, 2019), to name a few. The findings in the current study contrast the findings of past FAB research (Gibbons, Buchanan, et al., 2024; Gibbons, VanDevender et al., 2024) examining single, focused rehearsal ratings (thinking or talking) in the context of particular event types (e.g., political and problem-solving) and their control events (e.g., non-political and non-problem-solving). Specifically, single rehearsal ratings sporadically explained complex FAB effects in the context of problem-solving, and they did not explain complex FAB effects at all in the context of politics. Together, the results indicate that a combined rehearsal rating is more effective than a single, focused rehearsal rating when explaining complex FAB effects in the context of particular event types (e.g., alcohol) and their control events.

The findings in the current study extend to several real-world contexts, ranging from biweekly therapy sessions to anomalistic, worldwide crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of the current study suggest that our natural mechanism to retain positive experiences longer than negative experiences (i.e., FAB) can be strengthened by adaptive coping tools, such as spirituality, positive affect, and positive religious coping for non-alcohol events, which can help individuals effectively process psychological distress-inducing events. Encouraging clients to engage in adaptive practices like reflection, meaning-making, and emotional processing may foster resilience and reinforce a positive self-concept. Consequently, therapists should encourage their clients to engage in these coping tools to enhance their ability to regulate their event emotions, reinforce a positive self-concept, and foster resilience.

As engagement in both social and private rehearsals of events explained the healthy, emotion-regulating effects of spirituality, positive affect, and positive religious coping on emotion regulation in the current study, therapists should also encourage their clients to socially describe their events to others and mentally run through them daily. In terms of public crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, public service announcements could encourage people to enlist the aforementioned tools of spirituality, positive affect, and positive religious coping as well as to socially share and mentally go through their events consistently. These tools should help people emotionally regulate, enhance their self-concept, and take on new environmental challenges until they can meet with a therapist.

A key limitation of the current study was the lack of demographic diversity among participants, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The sample consisted primarily of individuals who were Caucasian (75.4%), Christian (83.9%), heterosexual (75.4%), and male (56.2%), with an average age of 36.63 years. Prior research has demonstrated that drinking behaviors and coping styles can vary across demographic backgrounds, including gender, ethnicity, and cultural background. For example, men tend to report an earlier age of first drink than women, which is significantly associated with later alcohol use patterns (York et al., 2004), and military data shows that younger men, particularly Hispanic and non-Hispanic White individuals, are more likely to engage in heavy drinking compared to women and other ethnic groups (Schumm & Chard, 2012). These demographic trends suggest that the relationships observed between alcohol use, coping strategies, and the FAB in the current study may not be representative of more diverse populations. Future research should aim to utilize more inclusive sampling procedures to better understand the way these psychological processes manifest across a broader range of individuals and cultural contexts.

Future research should explore whether the relations observed between FAB, alcohol consumption, coping strategies, event type, and rehearsals found during the pandemic in the current study persist in a post-pandemic context. Given that the COVID-19 pandemic created a unique social and emotional environment characterized by widespread isolation, heightened stress, and increased reliance on both adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms (Cziesler et al., 2020), it is unclear whether the same patterns would emerge outside of this context. For instance, the finding that alcohol consumption positively predicted the FAB may have been specific to the heightened emotional regulation needs of the pandemic period. In a post-pandemic context, however, individuals may receive greater access to resources that aid emotional regulation and coping, such as social support and community engagement. Therefore, future research could investigate whether the results in the current study replicate the prior results for FAB in the context of alcohol (Gibbons et al., 2013) or entirely new results are produced. In addition to conducting cross-sectional studies on the FAB in the context of alcohol and non-alcohol events, a longitudinal study would be particularly valuable in determining time precedence in the relation between alcohol consumption and the FAB. A longitudinal diary study could also ensure the veracity of the autobiographical event memories and test the relation of alcohol consumption to veridical and false memories, replicating and extending past research (Gibbons et al., 2023).

In summary, the current study is important because it is the first one to examine the Fading Affect Bias (FAB) in the context of alcohol and non-alcohol events during the COVID-19 pandemic while considering a wide range of psychological predictors, including coping strategies, affect, spirituality, religiosity, and rehearsal types. Consistent with prior research, the FAB was robust across event types and positively associated with healthy coping variables, supporting its role as an emotional regulation mechanism. Unexpectedly, alcohol use measures also positively predicted the FAB, possibly reflecting an adaptive, unhealthy coping response specific to the psychological distress produced by the pandemic. Additionally, three-way interactions revealed that higher levels of spirituality, positive affect, and positive religious coping predicted stronger FAB responses for non-alcohol events than alcohol events, highlighting these variables as powerful emotional resources in times of crisis. Importantly, the combined talking and thinking rehearsal rating mediated all of these three-way interactions.

The results can be applied to therapeutic and everyday contexts to aid emotion regulation. Limitations included a demographically homogeneous sample, which may have restricted generalizability, as well as the unique context of the pandemic, which may have influenced the findings of the study. Future research should replicate the current study in the post-pandemic context and strongly consider using longitudinal procedures. In conclusion, we found the FAB to be a healthy, emotion-regulating coping mechanism enhanced by other tools (e.g., spirituality) and explained by talking and thinking rehearsals in the context of alcohol and the COVID-19 pandemic, which was informative, but, like an epic hangover, the pandemic was too high a price to pay for this knowledge; never again.

References

- American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (2002, amended effective 1 June 2010, and 1 January 2017). 2017. Available online: http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.html.

- Anker, J. J.; Kushner, M. G.; Thuras, P.; Menk, J.; Unruh, A. S. Drinking to cope with negative emotions moderates alcohol use disorder treatment response in patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2016, 159, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, T. B.; Piper, M. E.; McCarthy, D. E.; Majeskie, M. R.; Fiore, M. C. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review 2004, 111(1), 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchmann, A. F.; Schmid, B.; Blomeyer, D.; Zimmermann, U. S.; Jennen-Steinmetz, C. [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M. H.; Esser, Günter; Banaschewski, Tobias; Mann, Karl; Laucht, M. Drinking against unpleasant emotions: possible outcome of early onset of alcohol use? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2010, 34(6), 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomeyer, D.; Buchmann, A. F.; Schmid, B.; Jennen-Steinmetz, C.; Schmidt, M. H.

- Banaschewski, T.; Laucht, M. Age at first drink moderates the impact of current stressful life events on drinking behavior in young adults. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2011, 35(6), 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caetano, R.; Mills, B. A.; Vaeth, P. A.; Reingle, J. Age at first drink, drinking, binge drinking, and DSM-5 alcohol use disorder among Hispanic national groups in the United States. Alcoholism: clinical and experimental research 2014, 38(5), 1381–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Melady, M.; Smith, J. E. Memory associations between negative emotions and alcohol on the lexical decision task predict alcohol use in women. Addictive behaviors 2012, 37(1), 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, H. The learning and retention of pleasant and unpleasant activities. Archives of Psychology 1932, 134, 1–96. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1997, 4, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, J. L.; Skowronski, J. J.; Davilla, A. L.; Milner, J. S. Does the fading affect bias vary by memory type and a parent’s risk of physically abusing a child? A replication and extension. Psychological Reports 2022, 37(9–10), 2418–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czeisler, M. É.; Lane, R. I.; Petrosky, E.; Wiley, J. F.; Christensen, A.; Njai, R.; Weaver, M. D.; Robbins, R.; Facer-Childs, E. R.; Barger, L. K.; Czeisler, C. A.; Howard, M. E.; Rajaratnam, S. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2020, 69(32), 1049–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duckworth, A. L.; Quinn, P. D. Development and validation of the short Grit scale (GRIT–S). Journal of Personality Assessment 91 2009, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvorak, R. D.; Sargent, E. M.; Kilwein, T. M.; Stevenson, B. L.; Kuvaas, N. J.; Williams, T. J. Alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences: associations with emotion regulation difficulties. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 2014, 40(2), 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ettman, C. K.; Abdalla, S. M.; Cohen, G. H.; Sampson, L.; Vivier, P. M.; Galea, S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3(9), e2019686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fjær, E. G. Moral emotions the day after drinking. Contemporary Drug Problems 2015, 42(4), 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geusens, F.; Vranken, I. Drink, share, and comment; Wait, what did I just do? Understanding online alcohol-related regret experiences among emerging adults. Journal of Drug Issues 2021, 51(3), 442–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.; Lee, S.; Walker, W. The fading affect bias begins within 12 hours and persists for 3 months. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2011, 25(4), 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Toscano, A.; Kofron, S.; Rothwell, C.; Lee, S. A.; Ritchie, T. D.; Walker, W. R. The fading affect bias across alcohol consumption frequency for alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related events. Consciousness and Cognition 2013, 22(4), 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Hartzler, J. K.; Hartzler, A. W.; Lee, S. A.; Walker, W. R. The fading affect bias shows healthy coping at the general level, but not the specific level for religious variables across religious and non-religious events. Consciousness and Cognition 2015, 36, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Fehr, A. M.; Brantley, J. C.; Wilson, K. J.; Lee, S. A.; Walker, W. R. Testing the fading affect bias for healthy coping in the context of death. Death Studies 2016, 40(8), 513–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Horowitz, K. A.; Dunlap, S. M. The fading affect bias shows positive outcomes at the general but not the individual level of analysis in the context of social media. Conscious and Cognition 2017, 53, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbons, J.; Lee, S.; Fehr, A.; Wilson, K.; Marshall, T. Grief and avoidant death attitudes combine to predict the fading affect bias. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018, 15(8), 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Lee, S. A. Rehearsal partially mediates the negative relations of the fading affect bias with depression, anxiety, and stress. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2019, 33(4), 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Bouldin, B. Videogame play and events are related to unhealthy emotion regulation in the form of low fading affect bias in autobiographical memory. Consciousness and Cognition: An International Journal 2019, 74, 102778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J.; Dunlap, S.; LeRoy, S.; Thomas, T. Conservatism positively predicted fading affect bias in the 2016 US presidential election at low, but not high, levels of negative affect. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2020, 35(1), 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Dunlap, S. M.; Horowitz, K.; Wilson, K. A fading affect bias first: Specific healthy coping with partner-esteem for romantic relationship and non-relationship events. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18(19), 10121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Lee, S. A.; Fernandez, L. P.; Friedmann, E. D.; Harris, K. D.; Brown, H. E.; Prohaska, R. D. The fading affect bias (FAB) is strongest for Jews and Buddhists and weakest for participants without religious affiliations: An exploratory analysis. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews 2021, 09(03), 350–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Rollins, L. Rehearsal and event age predict the fading affect bias across young adults and elderly in self-defining and everyday autobiographical memories. Experimental Aging Research 2021, 47(3), 232–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Dunlap, S.; Friedmann, E.; Dayton, C.; Rocha, G. The fading affect bias is disrupted by false memories in two diary studies of social media events. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2022, 36(2), 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Harris, K. D.; Friedmann, E. D.; Pappalardo, E. A.; Rocha, G. R.; Traversa, M. J.

- Nolan, M. J.; Lee, S. A. Coronaphobia flips the emotional world upside down: Unhealthy variables positively predict the fading affect bias at high physical symptoms of coronavirus anxiety. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2023, 38(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, J. A.; Vandevender, S.; Langhorne, K.; Peterson, E.; Buchanan, A. In-person and online studies examining the influence of problem-solving on the fading affect bias. Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 14(9), 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, J.; Mauss, I. B.; Tamir, M. A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2011, 6(3), 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grynberg, D.; de Timary, P.; Van Heuverswijn, A.; Maurage, P. Prone to feel guilty: Self-evaluative emotions in alcohol-dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2017, 179, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A. F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach; Guilford Press: New York, NY, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, A. M.; Duka, T. Facets of impulsivity and alcohol use: What role do emotions play? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2019, 106, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, D. S. Differential change in affective intensity and the forgetting of unpleasant personal experiences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1970, 15(3), 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jersild, A. Memory for the pleasant as compared with the unpleasant. Journal of Experimental Psychology 1931, 14(3), 284–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]