Perceptions of a good death have been explored in qualitative, clinical research, often by means of interviews. The objective of this research was to improve people's experiences during their final days. Yet, in theory, death valence might also affect satisfaction throughout life and even social issues like prejudice (Maj & Kossowska, 2016; Stiller, 2023; Wong, 2008). A recent study found that a more positive implicit death valence was associated with less prejudice against homosexual people and with less gender stereotypes (Stiller, 2021). In this study, people who valued death more favourably associated words meaning “gay” and “bad”, or ”feminine” and “communal” less automatically in reaction time tests. A quantitative measure to briefly contrast implicit death valence at an explicit level could advance future research in terminal care, personal well-being and social.

Death valence can be defined as a tendency to quickly evaluate the cessation of physical core functioning as good or bad (Barrett, 2006; Spellman, 2014). This automatic evaluation is accompanied by positive or negative affect. In interviews and surveys, hundreds of elderly or terminal people in the United States repeatedly stated to need agency, belonging, dignity, hope and meaning for a good death (Järviö et al., 2022; Kübler-Ross, 1969; Lormans et al., 2021). This research suggests that affect in the face of death depends on the automatic, culture-bound expectation of specific death needs being met (Stiller, 2023).

So far, the only suitable quantitative measure for death valence was the Death Valence Implicit Association Test within the Death Attitude IAT (Bassett & Dabbs, 2003). Especially explicit and implicit measures of death attitudes have strongly differed in past decades' research (Bassett et al., 2004). Therefore, Bassett et al. (2004) compared three implicit reaction time tests to measure affect in the face of death-related words: the emotional Stroop task (naming the colour of stimuli versus colours presented), the affective Simon paradigm (responding to affectivel in/congruent stimuli) and the IAT (associating death-related words with, for example, good or bad). While the results for the affective Simon paradigm and the Death Attitude IAT were associated, they showed no relationship with the emotional Stroop task. In turn, the affective Simon paradigm did not show sufficient validity compared to the IAT. The Death Valence IAT assesses reaction times in computerised stimuli categorisation. However, implicit and explicit attitudes represent distinct psychological modes. While implicit attitudes influence judgements and decision-making, they are often inaccessible to conscious awareness. As a result, implicit attitudes can be unrelated to explicit attitudes, or they can even contradict them (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). According to terror management theory (TMT), these mode differences might be especially pronounced in the case of death attitudes (Greenberg et al., 1986). The past decades' research on death attitudes supports this idea with consistent discrepancies between various implicit and explicit death attitude measures (Bassett et al., 2004).

TMT postulates that human death-awareness benefits survival, because it enables strategic planning to avoid death (Greenberg et al., 1986; Pyszczynski et al, 2015). However, death-awareness can also create paralysing anxiety in the short term. To avoid the detrimental effects of anxiety's paralysation, people deny their mortality, especially once it is triggered by a death reminder. Everyday death reminders, like reading the news, can trigger subtle anxiety and thus create “mortality salience” (Gailliot et al., 2008). Denying death buffers people's death anxiety before it reaches the conscious mind, so most people would explicitly accept their mortality without question. To quickly buffer death anxiety at an emotional level, people develop and defend cultural worldviews. By sharing worldviews, their beliefs outlive their physical bodies. Thus, cultural wordlviews do not only become a valuable part of the self, but they also become a tool to gain symbolic immortality. On the downside, these worldviews include stereotypes and prejudice. People tend to react with prejudice to mortality salience, in order to buffer death anxiety by feeling immortal. Terror management – and especially death denial - is thus a form of death coping with the social effect of worldview defence and prejudice. In previous research, mortality salience was associated with more gender stereotypes (Hoyt et al., 2011; Roylance et al., 2017; Schimel et al., 1999), racist assumptions (Niesta et al., 2008; Lewis et al., 2019) and prejudice against disabled people (Hirschberger et al., 2010; Nario-Redmond, 2019).

While TMT assumes that mortality salience automatically entails death denial due to an inherently negative view on death, Wong (2008) posits that death can also be accepted when people perceive their mortality more favourably. When people accept their mortality at an emotional (and not just at a rational) level, then they would need to defend their worldviews less. Accordingly, they would discriminate less against people perceived as others, be it due to their gender, sexual orientation, religion, racialisation, age or due to their physical and mental capacities. According to Wong (2008), death denial versus acceptance depends on death valence. If research beyond Stiller's (2021) findings supported an association between death valence and prejudice, then death valence might offer a promising avenue for developing more effective interventions against discrimination than previous approaches. Previous interventions tended to treat sexism, homophobia, racism and ableism separately, while often focusing more on rational knowledge than on emotional education (e. g., Bartoș & Hegarty, 2019; Bohonos & Sisco, 2021; Carr et al., 2012; Kilmartin et al., 2015; Kollmayer et al., 2018; Zawadzki et al., 2014). Compared to creating mortality salience, measuring death valence promises to illuminate possibilities for effective, intersectional interventions in well-being, thoughout until the end of life, and in social encounters. However, the measures for the construct are limited.

While terror management theory considers death as inherently negative, it associates this negativity with death denial. A recent study indicates that death coping might even go beyond the binary of death denial versus acceptance: In a mixed method analysis participants' essays about their mortality were contrasted with the Death Valence IAT (Stiller & Di Masso, 2024). Participants demonstrated complex emotions towards death, including anxiety, sadness and ambivalent calm. As Wong (2008) expected, negative death valence was linked to death denial, while positive death valence was linked to death acceptance. However, the variety of expressed emotions beyond death anxiety (the only emotion addressed by TMT) suggests the potential existence of more complex coping strategies than acceptance versus denial. In this study, implicit death valence was associated with a variety of specific, explicit emotions. Thus, death valence could precede plural terror management strategies.

In summary, death valence might impact life satisfaction and social equity beyond terminal care. Therefore, measures of the construct are indispensable to future clinical and social science research. Based on the lack of an explicit measure, this article proposes a thermometer scale for death valence in addition to the Death Valence IAT. This measure will be tested with a non-terminal, middle-aged US sample, which best fits prior research on terror management and on the Death Valence IAT. As a result, the present study aims to explore the following research questions:

R1: Can death valence be measured at an explicit level? In addressing this question, I will assess the reliability and the validity of the death valence item and its relationship with the implicit death valence measure.

R2: At an explicit level, is death valence linked to death needs, as indicated by Stiller (2023)?

R3: Is explicit death valence associated with binary terror management strategies (denial - acceptance) versus non-binary death coping (14 different kinds)?

Method

Transparency

A preregistration for this study can be found at osf.io/ckwqa.

Additionally, data and analyses for this research are available at osf.io/ckwqa/files/osfstorage.

Participants

A priori power analysis with G*Power 3.1 indicated a required sample size of 134 participants to detect medium-sized effects with an adequate statistical power of 1 - β = .950 (Faul et al., 2007). Data was collected in August 2024 via the crowdsourcing platform

www.clickworker.com. Participation was restricted to Clickworkers between 21-99 years who resided in the USA and used computers or laptops.

Sixty-two out of the initial 191 Clickworkers participated in all three waves. Their ages ranged from 22-75 years in wave 1 (

M = 40,

SD = 10), from 23-60 years in wave 2 (

M = 40,

SD = 9), and from 23-60 years in wave 3 (

M = 40,

SD = 9). More women than men participated in the first two waves, while wave 3 showed a more balanced gender distribution. Most participants across the waves identified as White and Christian or atheist. Most of them held a university degree. On a scale from 0 (

conservative) to 100 (

liberal), their political identities were slightly more liberal than conservative (wave 1:

M = 59.28,

SD = 28.64; wave 2:

M = 56,

SD = 29; wave 3:

M = 56.47,

SD = 30.65). Further demographic details are demonstrated in

Table 1.

Procedure

Data was retrieved from a set of online studies about death valence (wave 1-3) and prejudice (waves 2-3). Prior to participation, Clickworkers were provided with a general overview of the research topic. While participants were not deceived, the research questions were not disclosed to them until the end of the studies. In the first wave, participants' implicit death valence was assessed using reaction-time tests. The results were compared with their explicit death valence. Participants were further asked about previous suicide thoughts as a possible covariate. Along with this question, they immediately received contact data for the US Lifeline, in case they sought psychological support.

The newly developed thermometer scales for explicit death valence and associated concepts (like death needs) was repeated three times in order to check their reliability via the Heise procedure. Wave 2 was carried out 3-4 days later, wave 3 ca. 6 days after wave 1. After completing the set of studies, participants were compensated with 1.40 EUR

1 for each study, with an additional 0.30 EUR for reading the debriefing, in which the Lifeline contact data was repeated. Based on reaction times and thermometer scales with less than 85% variance, inattentive participants were excluded from the analyses (Carpenter et al., 2017; Greenwald et al., 1998).

Materials

Terror management theory assumes that death attitudes are hardly accessible through introspection. Implicit measures provide valuable insights into these less conscious attitudes. The Implicit Association Test (IAT) bases on reaction times and error rates during the computerised categorisation of stimuli (Greenwald et al., 1998). Reaction time tests are more resistent to deliberate manipulation. Schimmack (2021) criticised the insufficient validity of the IAT as a measure for stable personality traits. Conversely, it remains the most valid measure for intergroup differences in sensitive attitudes (Kurdi et al., 2021; Vianello & Bar-Anan, 2021). In particular, it remains the most valid implicit measure for death attitudes, compared to the affective Simon paradigm or the Stroop task (Bassett et al., 2004).

To assess implicit death valence, I used the Death Valence IAT (Bassett & Dabbs, 2003). The Death Valence IAT records reaction times and error rates for associations between words meaning good or bad and words meaning life or death. The IAT was created with seven blocks via iatgen.org. Latencies between the stimuli were set to 150 ms. For each error, 600 ms were added as penalty (Greenwald et al., 2003).

The resulting

D-scores

2 were calculated with the iatgen analysis tool, with higher

D-scores reflecting a more positive death valence.

To measure explicit death valence, the IAT words for good/bad and life/death were depicted as a semantic differential, in reply to the item: “Please indicate how much you associate the prospect of your own death with the following adjectives: bad (0) – great (100); terrible (0) – terrific (100); horrible (0) – wonderful (100)”. In addition, I created a death valence single item: “As humans, we usually know that we are mortal a long time before we die. Please evaluate the prospect of your own death on a scale from bad (0) – good (100)”. The item results will be compared with the semantic differential to check whether explicit death valence can be measured more concisely.

A previous article proposed the expectation of death need fulfilment to consitute death valence (Stiller, 2023). Based on dying people's experiences, those death needs comprise hope, meaning, agency, belonging and dignity (Järviö et al., 2022; Kübler-Ross, 1969; Lormans et al., 2021). Death needs should thus be associated with death valence. The following thermometer scales were created to assess death needs: “In addition, please indicate how much you associate the prospect of your own death with these words: hopeless (0) – hopeful (100); meaningless (0) - meaningful (100); helpless (0) – agentic (100); isolated (0) – accompanied (100); undignified (0) – dignified (100).” In line with Stoklasa et al.'s (2019) suggestion, I distinguished between attitude concepts and their relevance to the person within the thermometer scales by adding this item: “On a scale from 0-100, please indicate how relevant these adjectives are regarding your expecations about your own death (0 = completely irrelevant, 100 = very relevant): hopeful, meaningful, agentic, accompanied, dignified.” A compound score for each death need weighed by its relevance was created via a product term, divided by the scale range of 100.

Participants' affect in the past weeks was measured as a possible covariate of implicit and explicit death valence with the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (Watson et al., 1988). The scale includes 10 positive affect words (α = .92) and 10 negative affect words (α = .93), on a scale from very little or not at all (1) to extremely (5). In addition, life satisfaction, death proximity and different kinds of coping were assessed as potential covariates of explicit death valence. Positive death valence should theoretically covary with more life satisfaction (Wong, 2008). Therefore, life satisfaction may shed light on whether participants rather referred to life – good than death-bad in the Death Valence IAT. Accordingly, I assessed life satisfaction with the five items of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). Higher mean scores indicate higher life satisfaction (α = .91).

Near-death experiences suggest that people evaluate death more positively when they feel closer to it (Goranson et al., 2017). To overcome technical limitations, I developed a thermometer scale version of the Inclusion of the Self in Other Scale (Aron et al., 1992), ranging from not at all (0) – very much (100): “How much do you feel the fact that you will die some day?” Information about the item's test-retest reliability can be found in the Results section.

Coping measures included the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (α = .85; DAP-R; Wong et al., 1994) and the BriefCOPE (α = .86; Carver, 1997). The DAP-R includes the dimensions of fear of death (α = .88), death avoidance (α = .91), approach acceptance (α = .96), neutral acceptance (α = .73) and escape acceptance (α = .88). The items of each dimension are rated on a scale from

strongly disagree (1) to

strongly agree (5). Higher mean scores indicate higher fear, avoidance or acceptance. With avoidance and acceptance, the DAP-R comprises death-specific coping, or terror management, in which avoidance aligns with TMT's death denial. By contrast, the BriefCOPE a broader variety of specific coping strategies. The BriefCOPE has shown to be reliable for situational coping as well as for dispositional coping, depending on its instructions (Carver, 1997). Due to the possibility of plural rather than binary terror management (Stiller & Di Masso, 2024), the following question introduced the BriefCOPE: “How do you usually deal with the fact that you are going to die someday?”, on a range from

I usually don't do this at all (1) to

I usually do this a lot (4; for exceptions in wording, see Carver & Scheier, 1994; Carver, 1997). Higher mean scores indicate higher Active Coping

3, Planning (α = .83), Reframing (α = .82), Acceptance (α = .81), Humor (α = .93), Religion (α = .79), Search for Emotional Support (α = .90), Search for Instrumental Support (α = .85), Self-Distracion (α = .80), Denial (α = .68), Venting (α = .66), Substance Use (α = .92), Behavioral Disengagement (α = .83), or Self-Blame (α = .83).

In addition, I included four yes-no questions about participants' behavioural death coping to the survey: In the past six months, did you think of ending your life willingly? In the past six months, did you talk about your death or your last wishes to your friends or family? In the past six months, did you search for information about a good death for yourself, e. g., by writing a will or attending a conference or course about the topic? In the past, did you accompany a dying person over the course of various weeks?

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Significant Shapiro Wilk tests (p < .001) indicated non-normal data distributions for the Death Valence IAT (M = -.93, SD = .35), the Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R; see section “Validity of the Explicit Death Valence Item”), the BriefCOPE (see “Death Coping”), the Positive and Negative Attitude Schedule (PANAS; positive affect: M = 3.06, SD = 0.84; negative affect: M = 2.26, SD = 0.94) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale (M = 3.89, SD = 1.49). All thermometer scales were non-normally distributed (p < .001): the explicit death valence item (M = 54.10, SD = 27.94), a compound score for the death valence semantic differential (M = 34.70, SD = 25.58), death proximity (M = 68.81, SD = 31.63) and all death needs: hope (M = 26.24, SD = 30.40), meaning (M = 34.02, SD = 32.76), agency (M = 17.18, SD = 26.38), belonging (M = 29.19, SD = 31.71) and dignity (M = 38.32, SD = 33.90). Accordingly, I preferred Spearman over Pearson correlations for their statistical analyses.

Subsequently, I checked the measures' differences across demographic data and behavioural death valence indicators. The Death Valence IAT was significantly associated with age, ρ = -.208,

p = .004, but not with political identity,

p = .744. In contrast, score for explicit death valence were neither related to age,

p = . 626, or to political identity,

p = .697. Additional differences across demographic data in the measures for death valence, affect and coping are shown in Table A1 [M1] in the Appendix. Overall, a more positive death valence in the IAT was associated with younger age and non-White ethnicities (non-White:

M = -0.84,

SD = 0.38, White:

M = -0.99,

SD = 0.32), but with no further demographic data. The explicit death valence scale was related to two behavioural indicators, but to no other demographics (see Validity section and

Table A1).

Reliability of the Explicit Death Valence Item

Because Cronbach's Alpha cannot be calculated for single items, I applied the Heise procedure (Heise, 1969) to test the test-retest reliability of the death valence thermometer scale across the three waves. The Heise's reliability coefficient was calculated as the product term of the correlation between wave 1 and 2 with the correlation between wave 2 and 3, divided by correlation between wave 1 and 3. According to Spencer et al. (2003), the procedure can be carried out with Spearman correlations, if these are more suitable. Due to the non-normal data distribution of most death-related measures, I preferred Spearman correlations. The single correlations can be found in

Table 2 (all

p-values < .001).

To check the reliability of the semantic differential with the Death Valence IAT words, I created a mean score of the three subscales and compared them over time. In two-sided Spearman correlations, the compound score for the semantic differential was positively associated with the single death valence item, ρ = .470, p < .001, and negatively associated with the Death Valence IAT, ρ = -.151, p = .037. However, the Heise coefficient of .485 fell below the threshold of .500 and thus resulted to be insufficient. The item was thus excluded from further analyses. By contrast, the single death valence item showed an acceptable test-retest reliability with a Heise coefficient of .633. The death proximity item even seemed to be perfectly reliable with a Heise coefficient of 1. The scores for death needs weighed with their relevance also demonstrated overall acceptable test-retest reliabilities for hope (.562), meaning (.801), agency (.602), belonging (.771), dignity (.670).

Validity of the Explicit Death Valence Item

In continuation, I tested the death valence item's construct validity. For discriminant validity checks, I correlated the item with the Positive and Negative Attitude Schedule, the Satisfaction with Life Scale, with the question about suicidal thoughts and with the death proximity item. While explicit death valence was slightly associated with positive affect, ρ = .149, p = .040, it did not correlate with negative affect, p = .598. That means general positive affect might foster positive death valence, or vice versa at an implicit level. By contrast, the Death Valence IAT was not associated with positive affect, p = .117, or negative affect, p = .582. In a Mann-Whitney U-test, explicit death valence did not depend on suicidal thoughts, p = .679, indicating that death positivity is not linked to suicidality. Neither was the death valence item correlated with the life satisfaction score, p = .278. This finding partly contradicts Wong's (2008) assumption of higher life satisfaction when death is accepted, since death valence precedes death acceptance and should thus be associated indirectly with death positivity. Beyond general affect and life satisfaction, people with near-death experiences tend to evaluate death more positively (Goranson et al., 2017). Possibly, death proximity facilitates a change towards positive death valence. However, death proximity could also result in denial (Greenberg et al., 1986). The association between the items of death valence and death proximity confirms a slight association between the concepts, ρ = .151, p = .037.

For convergent validity, I correlated the item with the dimensions of the DAP-R. In line with TMT's death denial, death avoidance (M = 2.83, SD = 1.09) was negatively correlated with explicit death valence, ρ = -.212, p = .003. In addition to TMT, Wong (2008) assumend that death denial depends on negative death valence, while death accceptance depends on positive death valence. As expected, the explicit death valence item positively correlated with the DAP-R dimensions of neutral acceptance (M = 4.10, SD = .067), ρ = .152, p = .036, approach acceptance (M = 3.17, SD = 1.12), ρ = .231, p = 001, and escape acceptance (M = 3.12, SD = 1.04), ρ = .237, p < .001. Although not necessarily related in theory (Wong, 2008), fear of death negatively correlated with explicit death valence (M = 3.03, SD = 1.00), ρ = -.325, p < .001. This result might be an indirect consequence of participants' overall negative evaluation of their mortality: Even if death anxiety precedes death valence, death fears might be reinforced by negative death valence (Stiller & Di Masso, 2024). Despite their lack of pretesting, results for the death need items in research question 2 indicate the convergent validity of the death valence item, since death needs are supposed to constitute death valence.

To test the death valence item's concurrent criterion validity, I correlated it with the remaining three behavioural indicators for death valence (see

Table A1 in the Appendix). The recent search for information about a good death was unrelated to explicit death valence. However, participants who had talked more about their last wishes to friends and familiy, showed more explicit death positivity (

M = 61.30,

SD = 27.29) than those who had not talked about their last wishes (

M = 50.47,

SD = 27.67). Furthermore, those who had recently provided terminal care reported more explicit death positivy (

M = 63.14,

SD = 21.91) than those who did not provide terminal care (

M = 48.75,

SD = 29.78). Two out of three behavioural indicators thus confirm the concurrent criterion validity of the death valence item.

Finally, I compared the single item for explicit death valence with the Death Valence IAT. The negative association showed that the more positively people evaluated death on an implicit level, the more negatively they evaluated death on the explicit item, ρ = -.151, p = .037. This finding contrasts previous research, in which implicit and explicit death attitudes were usually unrelated across reaction time tests and self-reports (Bassett et al., 2004), although it confirms the possibility for contradictions between explicit and implicit results due to mode differences (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995).

Death Needs

If death valence is constituted by the expectation of death need fulfillment, then the compound score of death needs weighed by their relevance to participants should correlate with the explicit death valence item. As expected, explicit death valence was associated with the compound scores for hope (M = 26.24, SD = 30.40), ρ = .500, p < .001; meaning (M = 34.02, SD = 32.76), ρ = .348, p < .001; agency (M = 20.95, SD = 26.38), ρ = .354, p < .001; belonging (M = 29.19, SD = 31.71), ρ = .344 , p < .001, and dignity (M = 38.32, SD = 33.90), ρ = .214, p = .003.

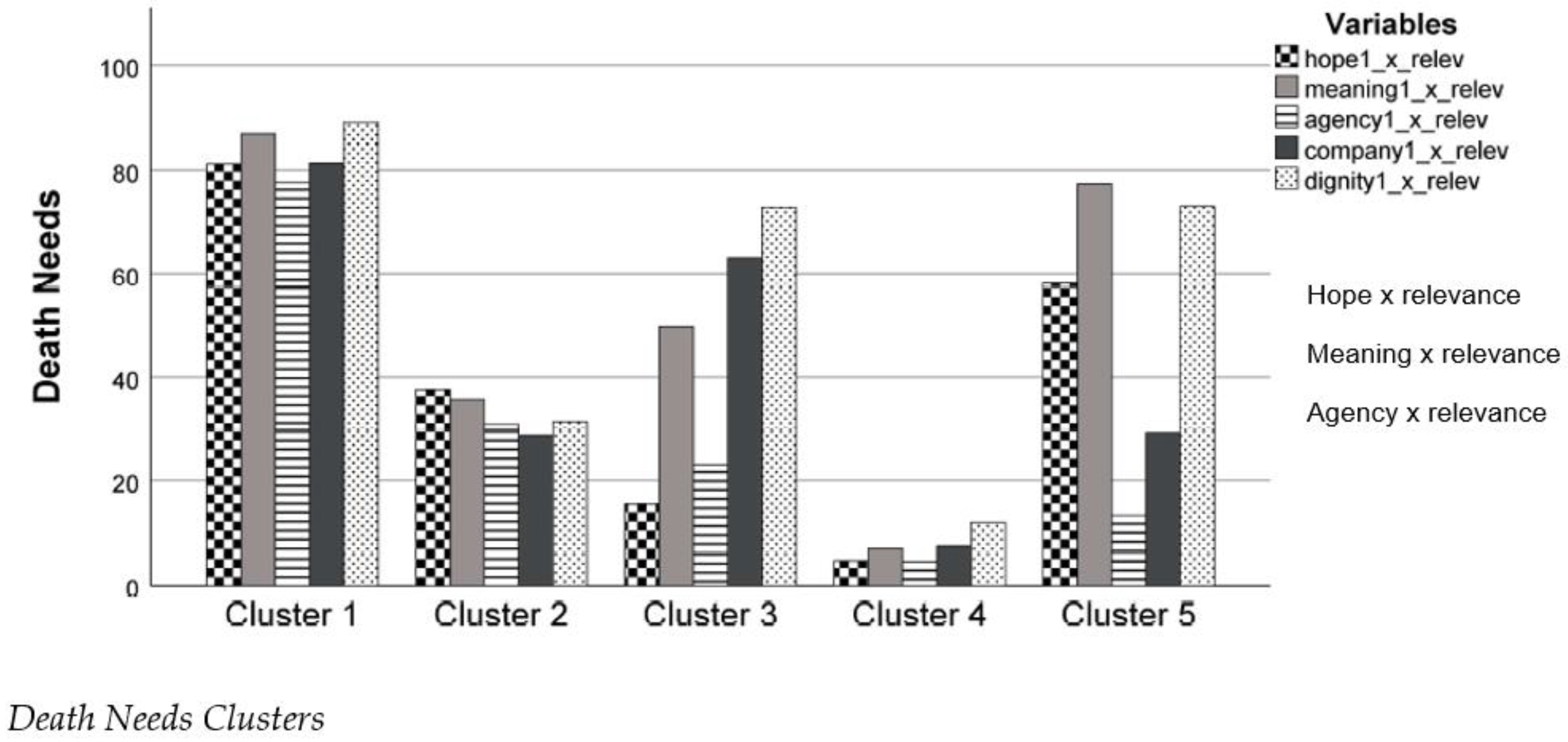

A k-means cluster analysis, with the criterion of at least 10 participants per cluster, revealed five different death need clusters across participants (see

Figure 1). Participants in cluster 1 strongly associated the prospect of their own death with all five death needs. Participants in cluster 2 showed medium-sized associations of their own death with all five death needs, while participants in cluster 4 only slightly associated their death with the proposed needs. Clusters 3 and 5 were more specific: Participants in cluster 3 associated their death with dignity, belonging and meaning. In turn, participants in cluster 5 rather associated their death with meaning, dignity and hope.

Comparing death valence between cluster 1 and cluster 4 resulted in significant differences (see

Table A1 in the Appendix): The high death need cluster 1 demonstrated a more positive death valence (

M = 69.65,

SD = 30.29) than the low death need cluster 4 (

M = 44.89,

SD = 28.43). Participants in cluster 1 had a mean age of 41 years (

SD = 8) and a rather liberal political identity (

M = 60.65,

SD = 31.35). Participants in cluster 4 had a comparable mean age of 38 years (

SD = 9) and a rather liberal political identity (

M = 63.75,

SD = 29.49). The insignificant comparisons between clusters 1 and 4 with further demographic data and behavioural indicators are shown in

Table 3.

The death need clusters 1 versus 4 varied with participants' recent affect, life satisfaction and death coping: People in cluster 4 (low death needs) showed more fear of death than those in cluster 1 (high death needs;

M1 = 2.75,

SD1 = 0.87 vs.

M4 = 3.29,

SD4 = 1.12). By contrast, people in the high death need cluster 1 demonstrated significantly more positive affect (

M1 = 3.49,

SD1 = 0.99, vs.

M4 = 2.81,

SD4 = 0.87), life satisfaction (

M1 = 4.68,

SD1 = 1.52, vs.

M4 = 3.59,

SD4 = 1.57), approach death acceptance (

M1 = 3.47,

SD1 = 0.97, vs.

M4 = 2.75,

SD4 = 1.10), Active Coping (

M1 = 2.75,

SD1 = 1.29, vs.

M4 = 2.00,

SD4 = 0.91), Reframing (

M1 = 3.20,

SD1 = 0.97, vs.

M4 = 2.22,

SD4 = 0.97), Acceptance Coping (

M1 = 3.40,

SD1 = 0.92, vs.

M4 = 2.95,

SD4 = 0.82), Religion (

M1 = 2.60,

SD1 = 1.18, vs.

M4 = 1.86,

SD4 = 0.93) and more Search for Emotional Support (

M1 = 2.60,

SD1 = 1.04, vs.

M4 = 1.82,

SD4 = 0.89). Further details about death coping by death need clusters can be found in

Table A1.

Death Coping

Is explicit death valence associated with death coping? Despite the binary options for death acceptance versus denial (Wong, 2008), recent research indicates the possibility of plural terror management strategies (Stiller & Di Masso, 2024). The plurality of emotions after mortality salience suggests that death coping might be equally non-binary. If terror management depends on death valence, then various coping strategies might occur. To measure these strategies beyond the DAP-R binaries of acceptance versus avoidance, the following death coping dimensions were assessed with the BriefCOPE (Carver, 1997): Active Coping (M = 2.24, SD = 0.99), Planning (M = 2.23, SD = 0.98), Reframing (M = 2.55, SD = 0.96), Acceptance (M = 3.03, SD = .080), Humor (M = 2.23, SD = 1.10), Religion (M = 2.25, SD = 1.04), Search for Emotional Support (M = 2.07, SD = 0.94), Search for Instrumental Support (M = 1.90, SD = 0.89), Self-Distracion (M = 2.64, SD = 0.92), Denial (M = 1.38, SD = 0.66), Venting (M = 1.94, SD = 0.66), Substance Use (M = 1.51, SD = 0.86), Behavioral Disengagement (M = 1.59, SD = 0.81), or Self-Blame (M = 2.07, SD = 0.96).

Indeed, a more positive death valence was associated with an increase in Active Coping, ρ = .166, p = .022; Reframing, ρ = .258, p < .001; Acceptance, ρ = .235, p < .001; Humor, ρ = .206, p = .004; Religion, ρ = .176, p = .021; and the Search for Emotional Support, ρ = .176, p = .015. By contrast, death valence was not related to Planning, p = .143; the Search for Instrumental Support, p = .346; Self-Distraction, p = .103; Denial, p = .676; Venting, p = .075; Substance Use, p = .523, Behavioral Disengagement, p = .326; or Self-Blame, p = .691. Accordingly, death valence was linked to different kinds of death coping, while death coping varied beyond the binary of denial versus acceptance. This finding supports the idea of plural terror management strategies. Future research will have to determine whether these strategies also affect worldview defence in distinct ways.

The death coping strategies that depended on death valence were subsequently contrasted with demographic data. While age did not affect Reframing,

p = .283; Acceptance,

p = .494; or the Search for Emotional Support,

p = .918, a higher age was associated with more Active Coping, ρ = .145,

p = .046, more Religion, ρ = .242,

p = > .001, and less Humor: ρ = -.186,

p = .010. Participants' political identity did not affect their death-related Active Coping, p = .665; Reframing,

p = .444; Acceptance,

p = .106; Humor,

p = .101; or Search for Emotional Support,

p = .950. However, more conservative participants tended to cope more with Religion, ρ = -.264,

p = > .001. Further differences in valence-related death coping across demographic data and behavioural indicators are depicted in

Table A1 in the Appendix.

Discussion

Explicit Death Valence

The present study examined whether death valence can be measured at an explicit level. Additionally, it investigated the relationship between explicit death valence, death needs, and binary versus plural death coping. If the proposed explicit scales measured death valence as well as the Death Valence IAT, then these scales would facilitate a quicker and technically more accessible assessment of death valence than the rather elaborate, costly and criticised IAT. These scales could then serve for preliminary quantitative assessments before interviews or to contrast the IAT with an explicit measure. While previous research assessed death valence through interviews with older or terminally ill people, this study tested the scales on non-terminal, younger participants. This approach reflects the possible implications of death valence for life satisfaction and social prejudice, beyond end-of-life care.

Due to the lack of explicit measures for death valence, the study based on three exploratory research questions instead of precise hypotheses. Research question 1 concerned the reliability and the validity of explicit death valence measures, in comparison with the Death Valence IAT. While a semantic differential version of the IAT resulted in insufficient reliability, a thermometer scale for explicit death valence demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability across 3 waves. Despite its conciseness being an advantage, the single-item scale shows potential for improvement. For example, enhancing the items' wording might increase its reliability.

The item's convergent validity was demonstrated through significantly positive associations with all three acceptance dimensions of the DAP-R survey. As predicted by Wong (2008), death positivity should entail death acceptance, while death negativity should foster death denial or avoidance. Divergent validity, in contrast, was demonstrated through significantly negative associations with the DAP-R avoidance dimension and through a lack of association with suicidal thoughts. While it might be argued that death positivity could increase suicidality, self-reported thoughts of ending one's life were neither linked to implicit or explicit death valence in either direction. However, the associations between death acceptance versus avoidance were rather small, suggesting that further factors determine whether death positivity transforms into death acceptance or whether a negative view on death transforms into death denial. To assess the death valence item's concurrent criterion validity, I asked participants about their recent search for information about a good death, for whether they had recently talked to relatives about their last wishes and whether they had given terminal care in the past six months. Although no direct behaviour was measured, people who reported to have talked about their last wishes or who had recently been providing terminal care reported more positive death valence on the single-item scale. In contrast, the recent search for information about a good death was unrelated to explicit death valence, possibly because I did not distinguish between rational and emotional death information. According to recent research, only emotional death information fosters death positivity (Lekes et al., 2022).

Finally, a comparison between the explicit death valence item with the Death Valence IAT resulted in a contradiction: People who evaluated death more positively on an implicit level, evaluated it more negatively on the explicit item. This finding contradicts or at least expands previous research, in which implicit and explicit death attitudes were typically unrelated across different reaction time tests and self-report measures (Bassett et al., 2004). The present study additionally suggests that only those who quickly associate death with something positive are able to express their negative thoughts about it openly. In contrast, people with a negative death valence might, in line with TMT, buffer the associated anxiety by pushing death out of conscious emotions. Furthermore, this finding corroborates the existence of mode differences at a more general level (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995).

In summary, the death valence thermometer scale presented in this article has demonstrated sufficient reliability and validity to be used as an additional measure. However, it should not serve as a stand-alone measure, because its reliability still leaves room for improvement, because the binary scale does not capture ambiguity about death and especially because of the conflicting findings for implicit and explicit death valence. Using the death valence item as a stand-alone measure implies the risk of fallacies about associations between constructs that may result from social desirability or a lack of conscious access to one's death attitudes. For example, it might that seem death valence was not associated with negative affect, because it is not openly expressed, or that death positivity was not associated with life satisfaction, because people express similar levels of satisfaction. In the case of prejudice, inaccessible death views and socially punished attitudes may lead to no association or even to contradictory explicit results. Therefore, implicit, explicit and on-time behavioural measures should accompany each other in future research. Accordingly, the death valence thermometer scale might be used to demonstrate differences in death attitudes across psychological modes.

When comparing implicit and explicit measures with behavioural indicators, the present study showed associations between explicit death valence and its behavioural indicators, but not between the behavioural indicators and implicit death valence. These findings are somewhat surprising, as talking about one's last wishes or providing terminal care might be expected to reduce implicit death denial and to boost positive death valence. However, the present as well as a previous study (Stiller, 2021) show that terror management and death valence are only associated and not equal to death valence. While explicit measures might increase the urge to express coherence with one's actions, own mortality can implicitly already be denied (again). This might especially happen when the cultural perception of death outweighs the changes in personal life, when death needs are expected to remain unfulfilled, or when people do not dispose of alternative coping strategies.

Recent affect, general life satisfaction, death needs and death coping were assessed as possible influence factors in death valence. Positive affect was linked to a slightly more positive death valence at an explicit level. This might either mean that a positive mood also influenced in the evaluation of one's own mortality. On the other hand, it might indirectly corroborate Wong's (2008) theoretical assumption of more positive affect in life and more life satisfaction when death is accepted. In a previous study (Stiller,2021), explicit death acceptance was associated with more positive affect and higher life satisfaction. Although Wong associates death acceptance with death positivity, life satisfaction in the present research was, on the contrary, not associated with explicit death valence. Furthermore, affect was not associated with implicit death valence. Maybe the indirect theoretical association between life satisfaction and death valence depends on acceptance coping or social desirability. Death proximity was associated with positive death valence, as expected. Most recorded cases show that feeling closer to death fosters a favourable view on one's own mortality. The rather modest association between death proximity and death valence might result from the possibility to deny one's mortality when a person feels closer to death. As a result, death valence may not only affect terror, but the available death coping strategies might also revert to death valence.

Explicit Death Valence and Death Needs

Although measuring death valence might be an advantage for future research in personal well-being, terminal care and social prejudice, these measures do not imply why people would view their mortality as good or bad. A recent literature review suggests that death valence depends on the expectation of death need fulfillment (Stiller, 2023). Therefore, the second research question explored possible associations between explicit death valence and death needs. As expected, all death needs weighed by their relevance were significantly associated with explicit death valence, indicating that the more people associated the prospect of their own death with hope, meaning, agency, belonging and dignity, the more favourable they viewed their own mortality. However, the rather modest associations suggest that further aspects could cocreate death valence. One the one hand, it might be interesting to explore the effect of expectations about death need fulfillment at an implicit level in future research. On the other hand, it is possible that combinations of death need expectations rather than single death needs constitute death valence.

In account of this possibility, a cluster analysis revealed five different death need clusters: high, medium and low death needs, as well as two more specific clusters: Cluster 3 focused on dignity, belonging and meaning, while cluster 5 centered on meaning, dignity and hope. Especially strong differences in death valence were expressed between the high and the low death-need clusters. Participants' affect, life satisfaction and death coping also varied significantly between these clusters: People in the low death need cluster demonstrated more fear of death, while people in the high death-need cluster demonstrated significantly more positive affect and more life satisfaction. In addition, people in the high death-need cluster reported different death coping strategies. Compared to the low death-need cluster, they showed more acceptance coping (especially approach death acceptance), active coping, reframing, more coping with religion and more search for emotional support. Due to these distinctive associations, the results suggest death need clusters rather than single death needs to constitute death valence.

An alternative explanation for the explicit link between death needs and death valence is social desirability: Maybe participants aimed to present themselves as coherent in their answers. Yet participants were not informed about the research question regarding an association between the concepts, rendering this alternative explanation unlikely. The findings of this study suggest that death need clusters might better inform death valence research than the scales for death needs and their relevance alone. However, the causes and consequences of death need clusters, as well as their relationship with death valence, remain an open field for future research.

Explicit Death Valence and Death Coping

If death needs describe what positive or negative death valence revert to (the “what” of death valence), then death coping determines the procedures associated with death valence (the “how” of it). While Wong's (2008) extended terror management theory considers acceptance versus denial as the only strategies to cope with subtle death anxiety, the complex emotions people reported about their mortality indicate the possibility of plural death coping and its varying social effects (Stiller & Di Masso, 2024). In the third research question of the present study, I thus examined whether explicit death valence relates to binary terror management strategies (denial - acceptance) versus non-binary death coping (of fourteen different kinds).

Wong (2008) proposed that death is denied when people hold negative views on their mortality. In contrast, death can be accepted when people view their mortality more favourably. Supporting this assumption, people who avoided death showed a more negative death valence, while people who accepted death showed a more positive death valence. Beyond binary coping, death positivity was associated with more active coping, reframing, coping with humor, coping with religion and with more search for emotional support. Although the associations between death valence and death coping require future research, the coping styles associated with positivity about one's mortality seem to reflect the death needs of hope and meaning (religion), agency (active coping), belonging (search for emotional support) and dignity (reframing), at least in part. In addition, humor might alleviate difficult feelings, especially in the face of death.

On the contrary, death valence was unrelated to the search for instrumental support, planning, self-distraction, substance use, behavioural disengagement or self-blame. Maybe the search for instrumental support in death issues rather depends on one's actual means to achieve one's objectives rather than just asking for it. Self-blame might not be associated to death valence, because humans are not held responsible for being mortal, except in strict religious interpretations (e. g., the Fall of Man, Genesis 3:19). In turn, the strategies of self-distracion, behavioural disengagement and substance use might require a more consciously accessible target than death. People would need to be not only aware of their death attitudes, but also of their distraction from them to explicitly report this kind of coping. Implicit measures or behavioural indicators might show different results regarding these strategies. Conversely, the lack of a relationship between planning and death valence is surprising, because planning has the potential to meet the need for agency and because people who had talked about their last wishes to their friends and family reported more death positivity. Future research might clarify this result. Finally, death valence did not seem associated with the BriefCOPE strategies of denial or venting. However, these two dimensions were the least reliable within the inventory and death avoidance in the DAP-R had conversely been linked with negative death valence.

Conclusions

While the only suitable quantitative measure for death valence so far was the Death Valence Implicit Association Test, quantitative measures comprised longer, explicit assessments like interviews. To provide a brief, explicit measure of death valence, the present study proposes a death valence thermometer scale. The scale has shown to be sufficiently reliable and valid. Due to differences in psychological modes, the scale serves as an additional measure for implicit tests, behavioural indicators or interviews. To better understand the reasons for a positive or negative evaluation of one's mortality, I tested the relationship between death valence and death need expectations. In line with prior research, people evaluated their own mortality more favourably when they expected their death needs to be met. Beyond death needs weighed by their relevance, death valence differed across five need clusters. In these clusters, people expressed low, medium or high death needs, as well as specific death need combinations. In addition to the death needs that might constitute death valence, death coping refers to the procedures linked to evaluating one's own mortality. The original version of terror management theory conceptualises death coping as denial, based on death negativity (Greenberg et al., 1986). The theory's extension by Wong (2008) adds acceptance, based on death positivity, as a possible strategy to deal with one's mortality. As suggested by Wong, death acceptance in the present study was linked to positive death valence, and death avoidance (denial) to negative death valence. However, complex emotions expressed in the face of death yield at plural terror management strategies (Stiller, 2023). The current study supports the idea of variations in death coping beyond acceptance or denial. In particular, five kinds of death coping were associated with death positivity (active coping, reframing, coping with humor, coping with religion and with more search for emotional support). These coping styles might, at first sight, relate to the death needs of hope, meaning, agency, belonging and dignity. However, future studies still have to shed light on the role of death needs and plural coping strategies in association with death valence. In addition. They shall clarify the benefits or obstacles of the death valence thermometer scale in research on personal well-being, terminal care and social prejudice.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

| 1 |

Clickworker operates in EUR, as its headquarter is located in Germany. Earnings for the large proportion of online workers residing in the US are later converted to USD. |

| 2 |

D-scores range between -2 and +2. They are calculated as mean differences divided by inclusive standard deviations of blocks 3 and 6, which are averaged with mean differences divided by inclusive standard deviations of blocks 4 and 7 (Carpenter et al., 2017; Lane et al. 2007). |

| 3 |

Cronbach's Alpha could not be calculated for the Active Coping dimension due to an error in the research setup, by which only one out of two Active Coping questions was added to the onlne test, resulting in a total of 27 instead of 28 BriefCOPE items. |

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the German Psychological Society DGPs (StillerMel2024-06-14WV).

Use of Artificial Intelligence

I used AI (GPT-4o) to revise grammar and style.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no potential conflict of interest regarding the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Appendix

Table A1.

Significance Levels (p) of Mann-Whitney U-Tests for Potential Covariates.

Table A1.

Significance Levels (p) of Mann-Whitney U-Tests for Potential Covariates.

| |

Gender |

Ethni-city |

Disa-bility |

Edu-cation |

Income |

Reli-gion |

Suicide Thoughts |

Last Wish |

Death Info |

Terminal Care |

Cluster 1 vs. 4 |

| DV IAT |

.857 |

.006* |

.409 |

.168 |

.881 |

.962 |

.445 |

.810 |

.076 |

.427 |

.070 |

| DV item |

.541 |

.936 |

.831 |

.477 |

.205 |

.528 |

.679 |

.009* |

.201 |

.001** |

>.001** |

| DAP-R Fear |

.770 |

.935 |

.751 |

.294 |

.338 |

.356 |

.933 |

.064 |

.393 |

.799 |

.039* |

| DAP-R Avoid |

.610 |

.790 |

.232 |

.261 |

.112 |

.551 |

.135 |

>.001**1 |

.106 |

.008*2

|

.923 |

| DAP-R Neutral |

.799 |

.180 |

.184 |

.537 |

.021*3

|

.793 |

.042*4

|

.379 |

.484 |

.148 |

.081 |

| DAP-R Appr |

>.001**5

|

.874 |

.467 |

.206 |

.438 |

>.001**6

|

.049*7

|

.915 |

.482 |

.130 |

.012* |

| DAP-R Escape |

.002*8

|

.204 |

.108 |

.637 |

.006*9

|

.024*10

|

>.001**11 |

.137 |

.011*12

|

.002**13

|

.622 |

| D-Prox |

.024*14

|

.968 |

.311 |

.046*15 |

.035*16

|

.187 |

.213 |

.341 |

.535 |

.082 |

.398 |

| PA1 |

.254 |

.215 |

.034*17

|

.855 |

.339 |

.059 |

>.001** 18 |

.207 |

.766 |

.904 |

.007* |

| NA1 |

.326 |

.016*19

|

.006*20

|

.161 |

.268 |

.672 |

>.001**21 |

.002**22

|

.222 |

.183 |

.083 |

| SWLS |

.125 |

.162 |

.040*23

|

.432 |

>.001**24 |

.225 |

>.001**25

|

.794 |

.753 |

.418 |

.008* |

| BC Active |

.731 |

.289 |

.812 |

.261 |

.649 |

.013*26

|

.074 |

.855 |

.787 |

.862 |

.017* |

| BC Reframe |

.581 |

.184 |

.150 |

.153 |

.648 |

.007*27

|

.148 |

.697 |

.313 |

.405 |

>.001** |

| BC Accept |

.836 |

.632 |

.160 |

.724 |

.832 |

.285 |

.388 |

.110 |

.323 |

.047*28

|

.014* |

| BC Humor |

.011*29

|

.612 |

.104 |

.546 |

.570 |

.008*30

|

.002**31

|

>.001**32 |

.014*33

|

.191 |

.977 |

BC

Reli |

.033*34

|

.635 |

.880 |

.507 |

.476 |

>.001**35

|

.070 |

.259 |

.001**36

|

.315 |

.010* |

| BC EmoS |

.058 |

.686 |

.194 |

.007*37

|

.136 |

.003**38

|

.184 |

.228 |

.113 |

.986 |

.002** |

1: Participants who talked about their last wishes showed less death avoidance (M = 2.25, SD = 0.91) than those who had not talked about it. (M = 3.12, SD = 1.06). 2: Participants who had given terminal care showed less death avoidance (M = 2.57, SD = 0.99) than those who had no terminal care experience (M = 2.99, SD = 1.12). 3: Participants with a high income showed more neutral death acceptance (M = 4.25, SD = 0.61) than those with a low income (M = 3.98, SD = 0.73). 4: Participants without suicide thoughts showed more neutral death acceptance (M = 4.14, SD = 0.65) than those who had suicide thoughts (M = 3.87, SD = 0.72). 5: Women showed more approach acceptance (M = 3.38, SD = 1.13) than men (M = 2.87, SD = 0.97). 6: Christian showed more approach acceptance (M = 3.84, SD = 0.81) than atheists (M = 2.37, SD = 1.00). 7: Participants without suicide thoughts showed more approach acceptance (M = 3.24, SD = 1.10) than those with them (M = 2.80, SD = 1.14). 8: Women showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.31, SD = 1.02) than men (M = 2.77, SD = 1.01). 9: Participants with a low income showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.27, SD = 1.04) than those with a high income (M = 2.78, SD = 0.91).

10: Christians showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.26, SD = 0.96) than atheists (M = 2.90, SD = 1.11). 11: Participants with suicide thoughts showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.82, SD = 1.05) than those without them (M = 2.99, SD = 0.98). 12: Participants who had previously been looking for information about a good death showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.59, SD = 1.02) than those who had not searched information about a good death (M = 3.04, SD = 1.02). 13: Participants who had given terminal care showed more escape acceptance (M = 3.40, SD = 1.04) than those without terminal care experience (M = 2.96, SD = 1.01). 14: Women felt death closer (M = 73.06, SD = 29.14) than men (M = 61.57, SD = 34.82). 15: Participants with a high school degree felt death closer (M = 75.24, SD = 31.14) than university graduates (M = 66.21, SD = 31.57). 16: Participants with a low income felt death closer (M = 73.68, SD = 29.43) than those with a high income (M = 60.39, SD = 35.17). 17: Nondisabled participants felt more positive affect (M = 3.13, SD = 0.83) than disabled participants (M = 2.76, SD = 0.83). 18: Participants without suicide thoughts showed more positive affect (M = 3.17, SD = 0.80) than those with them (M = 2.50, SD = 0.85). 19: Non-White participants showed more negative affect (M = 2.50, SD = 1.06) than White participants (M = 2.10, SD = 0.82).

20: Disabled participants felt more negative affect (M = 2.17, SD = 0.91) than nondisabled participants (M = 2.67, SD = 0.98). 21: Participants with suicide thoughts showed more negative affect (M = 3.05, SD = 0.96) than those without them (M = 2.10, SD = 0.86). 22: Participants who talked about their last wishes showed more negative affect (M = 2.49, SD = 0.89) than those who did not (M = 2.14, SD = 0.95). 23: Nondisabled people participants reported more life satisfaction (M = 4.00, SD = 1.48) than disabled participants (M = 3.41, SD = 1.46). 24: Participants with a high income reported more life satisfaction (M = 4.48, SD = 1.36) than those with a low income (M = 3.40, SD = 1.61). 25: Participants without suicide thoughts reported more life satisfaction (M = 4.15, SD = 1.36) than those with them (M = 2.57, SD = 1.46). 26: Christians used more active coping (M = 2.42, SD = 0.96) than atheists (M = 2.06, SD = 0.98). 27: Christians coped more with reframing (M = 2.76, SD = 0.88) than Atheists (M = 2.35, SD = 0.97). 28: Participants who had given terminal care showed more acceptance coping (M = 3.29, SD = 0.72) than those without terminal care experience (M = 3.04, SD = 0.83). 29: Men coped more with humor (M = 2.46, SD = 1.02) than women (M = 2.06, SD = 1.10). 30: Atehists coped more with humor (M = 2.44, SD = 1.12) than Christians (M = 1.98, SD = 1.04).

31: Participants with suicide thoughts coped more with humor (M = 2.79, SD = 1.01) than those without them (M = 2.12, SD = 1.09). 32: Participants who talked about their last wishes showed more coping with humor (M = 2.64, SD = 1.13) than those who did not tlak about them (M = 2.03, SD = 1.03). 33: Participants who had previously been looking for information about a good death showed more coping with humor (M = 2.71, SD = 1.04) than those without death information (M = 2.15, SD = 1.09). 34: Women showed more religious coping (M = 2.38, SD = 1.06) than men (M = 2.03, SD = 0.97). 35: Christians showed more religious coping (M = 2.81, SD = 0.89) than atheists (M = 1.55, SD = 0.77). 36: Participants who had previously been looking for information about a good death showed more religious coping (M = 2.82, SD = 0.87) than those without death information (M = 2.15, SD = 1.04). 37: University graduates searched for more emotional support (M = 2.18, SD = 0.94) than participants with a high school degree only (M = 1.79, SD = 0.89). 38: Christians searched for more emotional support (M = 2.26, SD = 0.93) than atheists (M = 1.83, SD = 0.86).

References

- Barrett, L. F. (2006). Valence is a basic building block of emotional life. Journal of Research in Personality 40(1), 35-55. [CrossRef]

- Bartoș, S. E. , & Hegarty, P. (2019). Negotiating theory when doing practice: A systematic review of qualitative research on interventions to reduce homophobia. Journal of Homosexuality. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J. F. , & Dabbs, J. M. (2003). Evaluating explicit and implicit death attitudes in funeral and university students. Mortality 8(4), 352–371. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, J. F. , Washburn, D. A., Vanman, E. J., & Dabbs, J. M. (2004). Assessing the Affective Simon Paradigm as a measure of individual differences in implicit social cognition about death. Current Research in Social Psychology 9(17), 234–247.

- Bohonos, J. W. & Sisco, S. (2021). Advocating for social justice, equity, and inclusion in the workplace: An agenda for anti-racist learning organizations. New Directions in Adult and Continuing Education, 2021, p. 89-98. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, P. , Morris, K. L., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2017). Open to death: A moderating role of openness to experience in terror management. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 71, 117-127. [CrossRef]

- Burke, B. L. , Martens, A., & Faucher, E. H. (2009). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 155–195. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, F. K. (2008). Refusing able(ness): A preliminary conversation about ableism. M/C Journal, 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, T. , Pogacar, R., Pullig, C., Kouril, M., LaBouff, J., Aguilar, S., & Chakroff, A. (2017). Building and analyzing Implicit Association Tests for online surveys: A tutorial and opensource tool.

- Carr, L. , Darke, P., & Kuno, K. (2012). Disability equality training: Action for change. MPH Publishing.

- Ehlers, A. , & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Research and Therapy 38, 319–345. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F. , Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, l, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Gailliot, M. T. , Stillman, T. F., Schmeichel, B. J., Maner, J. K., & Plant, E. A. (2008). Mortality salience increases adherence to salient norms and values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(7), 993-1003. [CrossRef]

- Glick, P. & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512. [CrossRef]

- Goranson, A. , Ritter, R. S., Waytz, A., Norton, M. I., & Gray, K. (2017). Dying is unexpectedly positive. Science 28(7), 988–999. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, J. , Pyszczynski, T., & Solomon, S. (1986). The causes and consequences of a need for self-esteem: A terror management theory. In R. F. Baumeister, Public self and private self (pp. 189-212). Springer.

- Greenberg, J. , Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Rosenblatt, A., Veeder, M., Kirkland, S., & Lyon, D. (1990). Evidence for terror management theory II: The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who threaten or bolster the cultural worldview. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(2), 308-318. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G. , McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1464-1480. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G. , Nosek, B. A., & Banaji, M. R. (2003). Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 197-216. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, A. G. , & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review, 102(1), 4-27. [CrossRef]

- Heise, D.R. (1969). Separating reliability and stability in test-retest correlation. American Sociological Review, 34(1), 93-101. [CrossRef]

- Hirschberger, G. , Ein-Dor, T., Caspi, A., Arzouan, Y., & Zivotofsky, A. Z. (2010). Looking away from death: Defensive attention as a form of terror management. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46(1), 172-178. [CrossRef]

- Järviö, T. , Nosraty, L., & Aho, A. L. (2022). Older individuals’ perceptions of a good death: A systematic literature review. Death Studies, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin, C. , Semelsberger, R., Dye, S., Boggs, E., & Kolar, D. (2015). A behavior intervention to reduce sexism in college men. Gender Issues, 32, 97-110. [CrossRef]

- Klein, R. A. , Cook, C. L., Ebersole, C. R., Vitiello, C., Nosek, B. A., Hilgard, J., (...), & Ratliff, K. A. (2022). Many Labs 4: Failure to replicate mortality salience effect with and without original author involvement. Collabra: Psychology, 8(1), 35271. [CrossRef]

- Kollmayer, M. , Schober, B., & Spiel, C. (2018). Gender stereotypes in education: Development, consequences, and interventions. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 361–377. [CrossRef]

- Kübler-Ross, E. (1969). On death and dying. Touchstone.

- Kurdi, B. , Ratliff, K. A. and Cunningham, W. A. (2021) Can the Implicit Association Test serve as a valid measure of automatic cognition? A response to Schimmack (2021). Perspectives on Psychological Science 16(2), 422–434. [CrossRef]

- Lekes, N. , Martin, B. C., Levine, S. L., Koestner, R., & Hart, J. A. (2022). A death and dying class benefits life and living: Evidence from a nonrandomized controlled study. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 00(0), 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K. , & David, A. (2019). Death and racism: Mortality salience effects on stereotypical tendencies.

- Lormans, T. , de Graaf, E., van de Geer, J., van der Baan, F., Leget, C., & Teunissen, S. (2021). Toward a socio-spiritual approach? A mixed-methods systematic review on the social and spiritual needs of patients in the palliative phase of their illness. Palliative Medicine, 35(6), 1071-1098. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. , Yang, Y., Chen, H., Ma, H., & Tan, Y. (2024). Effects of different psychosocial interventions on death anxiety in patients: A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontiers in Psychology, Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Maj, M. , & Kossowska, M. (2016). Prejudice toward outgroups as a strategy to deal with mortality threat: Simple reaction with complex foundation. Theoria et Historia Scientiarum, 12, 15-28. [CrossRef]

- Niesta, D. , Fritsche, I., & Jonas, E. (2008). Mortality salience and its effects on peace processes: A review. Social Psychology, 39(1), 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T. , Solomon, S., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 1-70. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ferreiro, J. , Barberia, I., González-Guerra, J., & Vadillo, M. A. (2019). Are we truly special and unique? A replication of Goldenberg et al. (2001). Royal Society Open Science, 6: 191114. [CrossRef]

- Samarel, N. (2018). The dying process. In H. Wass & R. A. Neimeyer (Eds.), Dying: Facing the facts (3rd ed., pp. 89- 116). Taylor & Francis.

- Schimel, J. , Simon, L., Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Waxmonsky, J., & Arndt, J. (1999). Stereotypes and terror management: Evidence that mortality salience enhances stereotypic thinking and preferences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(5), 905-926. [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, U. (2021) The Implicit Association Test: A method in search of a construct. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 396-414. [CrossRef]

- Spellman, W. M. (2014). A brief history of death. Reaktion Books.

- Spencer, F. H. , Bornholt, L. J., & Ouvrier, R. A. (2003). Test reliability and stability of children's cognitive functioning. Journal of Child Neurology, 18(1), 5-11. [CrossRef]

- Stiller, M. Queer terror management: Theory, test and indicators towards a psychosocial intervention in gender stereotypes via death attitudes [Doctoral dissertation, University of Barcelona]. http://diposit.ub.edu/dspace/-handle/2445/184055.

- Stiller, M. (2023). The constitution of death valence as a key to intervene in social discrimination. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. Advance Online Publication. [CrossRef]

- Stiller, M. , & Di Masso, A. (2024). The power of death valence: A revised terror management process. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 90(2), 594-610. [CrossRef]

- Thwaites, R. & Freeston, M. H. (2005). Safety-seeking behaviours: Fact or function? How can we clinically differentiate between safety behaviours and adaptive coping strategies across anxiety disorders? Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 177-188. [CrossRef]

- Vianello, M. & Bar-Anan, Y. (2021). Can the Implicit Association Test measure automatic judgment? The validation continues. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(2), 415-421. [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063. [CrossRef]

- Wong, P. T. P. (2008). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In A. Tomer, E. Grafton, & P. T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 65-87). Erlbaum.

- Zawadzki, M. J. , Shields, S. A., Danube, C. L., & Swim, J. K. (2014). Reducing the endorsement of sexism using experiential learning: The workshop activity for gender equity simulation (WAGES). Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(1), 75-92. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).