1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Conceptual Background

The origin of quantization remains one of the most fundamental and persistent mysteries in theoretical physics [24,83,104]. Modern quantum field theory (QFT) is built upon the postulate that physical observables correspond to noncommuting operators,

where

ℏ—Planck’s constant—is the universal quantum of action separating the classical from the quantum domains [8,74]. Despite its centrality, no established theory explains why

ℏ should exist at all, why it has a fixed value, or whether it can arise dynamically from a more primitive substrate [45,69,83].

Traditional quantization procedures—canonical, path-integral, or operator-based—introduce ℏ axiomatically as a scale factor translating between action and probability [26,32]. Alternative attempts to interpret ℏ as a statistical or thermodynamic quantity have struggled to identify a consistent microscopic origin [13,30]. Either ℏ becomes scale-dependent (inconsistent with experiment) or it is attributed to stochastic fluctuations whose physical source is unspecified. These persistent limitations motivate a conceptual shift: quantization must not be an externally imposed rule, but a dynamical property of the underlying pre-geometric medium from which spacetime, matter, and coherence emerge.

1.2. The Central Idea

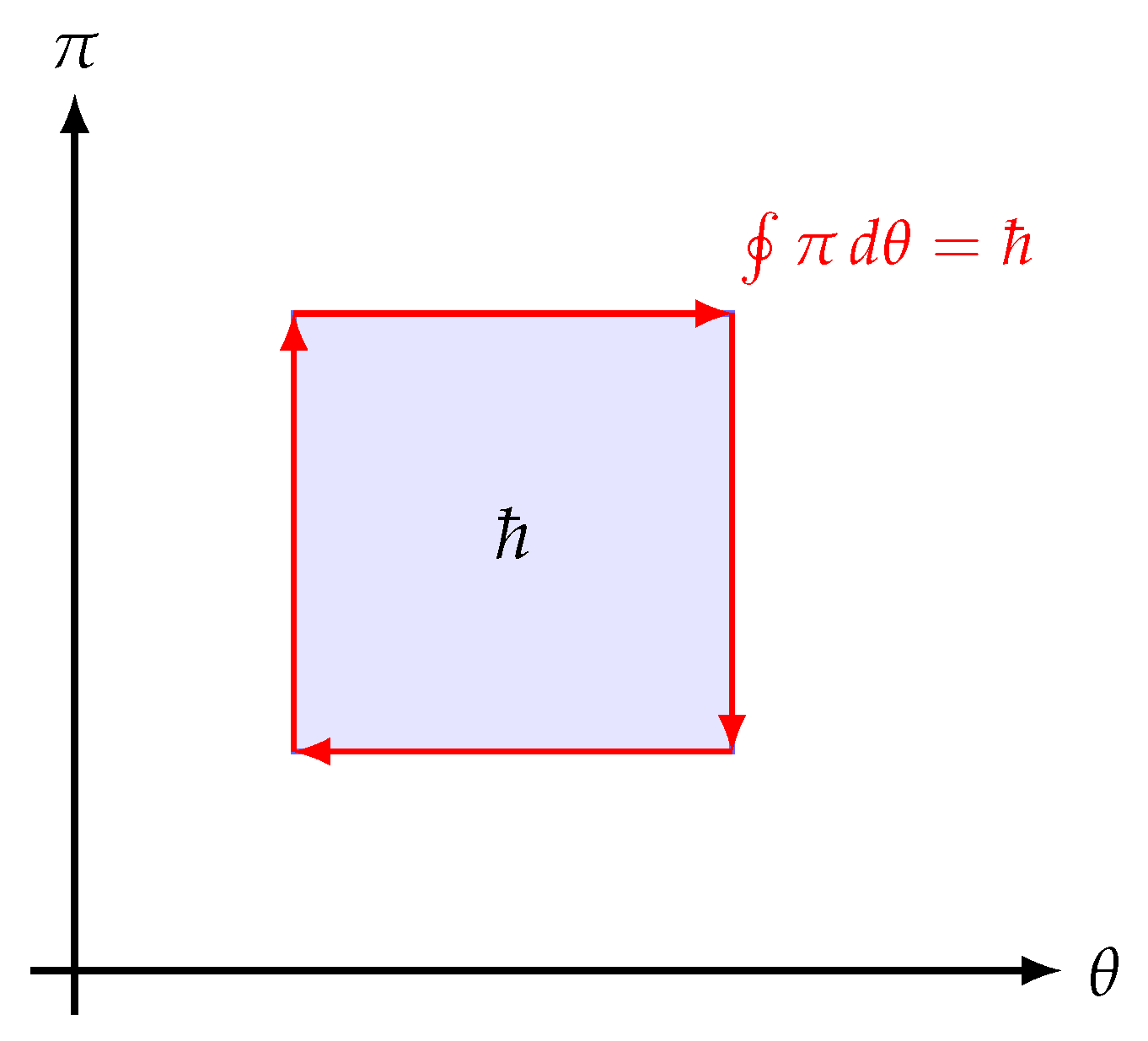

This work proposes a unified foundation for quantum theory in which Planck’s constant ℏ is not a parameter but a curvature invariant of an underlying temporal field—the chronon field. A rigorous statistical–mechanical foundation for the chronon ensemble, including the emergence and exclusivity of Lorentzian causal structure and a globally unit–norm time field, was established in [63]. The present work builds directly on that foundation, extending the analysis into the quantum regime where the same chronon field gives rise to canonical commutation, intrinsic spin, and Fermi–Bose statistics. Rather than arising through coarse-graining or randomness, ℏ appears as the fixed symplectic flux of the chronon manifold—a universal curvature modulus linking canonical commutation, spin quantization, and particle statistics [62].

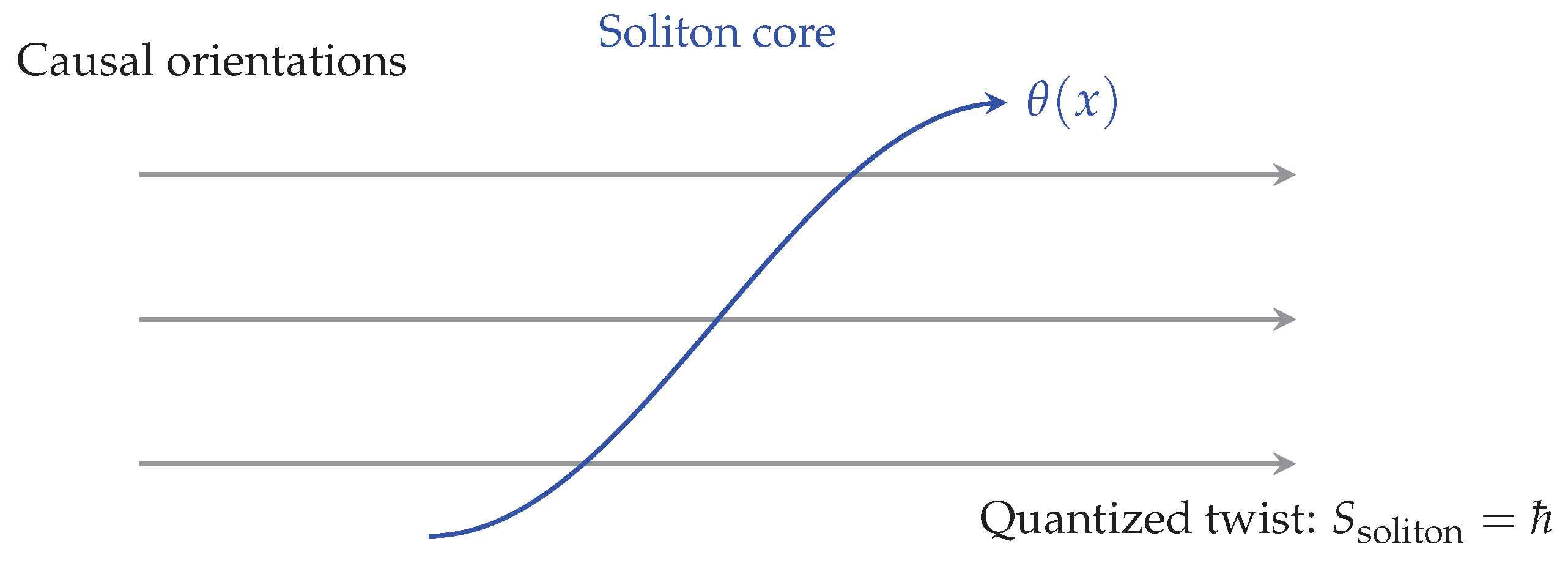

The chronon field is a microscopic network of elementary causal links whose collective organization defines emergent spacetime geometry and internal phase structure. Quantization corresponds to the stabilization of symplectic curvature at a critical correlation length

, where

denotes the Planck scale [69,104]. Below this threshold (the

pre-geometric phase), chronon orientations fluctuate independently and no coherent spacetime manifold exists. At

, local alignments form stable, finite-energy packets of phase rotation—

chronon solitons. Each soliton carries a minimal action

representing the smallest symplectic area permitted by the curvature of the chronon manifold. This defines

ℏ as the

elementary flux quantum of the underlying temporal geometry.

1.3. Unified Origin of Spin and Statistics

A central result of this paper is that the same curvature invariant

ℏ also governs intrinsic angular momentum and exchange statistics. When the soliton configuration space admits a nontrivial double covering,

a

spatial rotation induces a sign reversal in the wavefunctional (the Finkelstein–Rubinstein condition) [33,47], producing half-integer spin:

This topological mechanism simultaneously gives rise to

Fermi statistics, since the multi-soliton configuration space carries the nontrivial representation of the permutation group

[5]. Thus, the half-quantum of spin and the antisymmetry of fermionic exchange derive from the same double-cover topology, not from an independent postulate.

By contrast, the photon arises not as a soliton but can be interpreted as a Goldstone-like excitation of the chronon field’s global time-phase symmetry [62]. Its polarization represents oscillations in the internal fiber of the chronon bundle, corresponding to an integer-spin representation of . The photon’s spin quantum ℏ therefore stems from the same symplectic curvature as the soliton’s, but integrated over a single-valued rotational sector. Matter and radiation thus share a common geometric origin: both are excitations of the same curvature field, distinguished only by their topological covering multiplicity.

1.4. Physical Intuition

The chronon field provides a microscopic substrate for causal order. It may be visualized as a dense network of infinitesimal “arrows of time,” each represented by a local timelike vector attached to a site p of an underlying manifold or discrete complex. Each chronon encodes a primitive distinction between “before” and “after,” but isolated orientations do not yet constitute spacetime; only their collective alignment generates a continuous causal geometry [63,104].

Pre–geometric foam

At sub–Planck scales (), chronon orientations fluctuate randomly, forming a chaotic causal foam with no fixed metric, light cone, or stable excitation. This regime corresponds to the pre–geometric phase of the chronon field, where the notions of distance and duration have no meaning beyond local correlations [69,83].

Quantum Phase and Canonical Structure

Beyond this threshold (

), the chronon field supports collective excitations: solitons and propagating phase waves. In this

quantum phase, the canonically conjugate leaf variables

satisfy

expressing the symplectic structure of the chronon ensemble. Here,

measures the minimal symplectic area of phase–space curvature, linking the intrinsic geometry of

to the algebra of observables [24,62]. The photon then appears as a collective Goldstone–like excitation of the

chronon phase: it

inherits the established unit

but does not create new topological windings. Macroscopic momenta and energies correspond to accumulated symplectic area,

, not to multiple solitonic twists.

Hierarchy of Dynamical Phases

Table 1.

Dynamical phases of the chronon ensemble. The Planck boundary marks the emergence of a universal symplectic curvature ℏ that governs canonical, rotational, and statistical quantization across all higher regimes.

Table 1.

Dynamical phases of the chronon ensemble. The Planck boundary marks the emergence of a universal symplectic curvature ℏ that governs canonical, rotational, and statistical quantization across all higher regimes.

| Phase |

Length scale |

Order parameter |

Dominant dynamics |

Physical character |

| Pre-geometric |

|

None (disordered) |

Random chronon noise |

No metric, no excitations |

| Planck |

|

Local alignment

|

Topological soliton formation |

Action quantization () |

| Quantum |

|

Stable phase field

|

Canonical and gauge oscillations |

; spin–statistics unification |

| Macroscopic |

|

Domain coherence |

Mean-field alignment |

Classical limit; decoherence |

1.5. Order Formation and Scale Persistence

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) involves no thermodynamic variables or physical temperature. Nevertheless, the transition at the Planck boundary admits a useful analogy to ordering phenomena in statistical and dynamical systems [38,50,56]. Here the degree of causal alignment within the chronon ensemble serves as an order parameter for coherence, while stochastic fluctuations in local orientation provide the effective source of disorder.

As the intrinsic control parameter—the ratio of alignment stiffness to stochastic amplitude—increases, correlations extend across multiple chronon domains and the ensemble crosses a critical threshold where the symplectic curvature modulus ℏ becomes fixed [59,60]. This defines a scale-driven ordering transition: the chronon field self-organizes from pre-geometric randomness into a coherent quantum phase purely through internal dynamical consistency, without the mediation of thermal processes or external cooling.

Once established, the curvature modulus ℏ remains invariant across all larger scales, ensuring that quantized action, spin, and causal coherence persist as stable geometric features of the chronon manifold [77]. In this interpretation, ℏ is not a thermodynamic quantity but a symplectic invariant— a fixed curvature modulus of the chronon field that encodes the minimal causal and geometric coherence underlying emergent quantum phenomena.

1.6. Structure of the Paper

Section 2 develops the mathematical structure of the chronon field and its Hamiltonian.

Section 3 analyzes the four dynamical regimes and their order parameters.

Section 4 constructs the canonical and symplectic framework of the quantum phase and demonstrates the emergence of

ℏ as the minimal symplectic eigenvalue.

Section 7 establishes the unified geometric origin of

ℏ in canonical commutation, spin quantization, and Fermi statistics, including the role of the

double cover and the distinct antisymmetries of conjugate pairs and exchange operations.

Section 5 presents numerical realizations of the transition and commutator stabilization. Finally,

Section 8 discusses implications for quantum foundations, emergent gauge structure, and the universality of Planck’s constant.

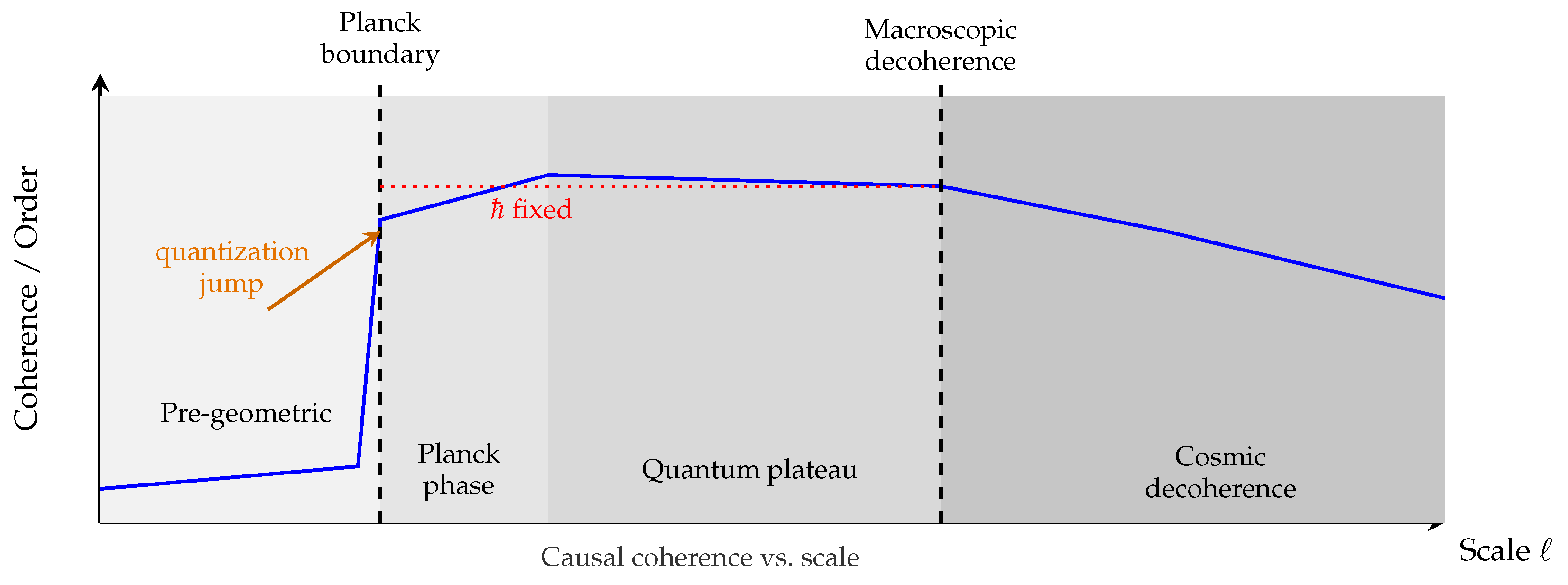

Figure 1.

Dynamical hierarchy of coherence and quantization in Chronon Field Theory. Causal coherence rises sharply at the Planck boundary (), marking the emergence of the finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ. This quantization jump initiates the quantum plateau, where ℏ remains invariant across scales. At cosmic distances, inter-domain misalignment and horizon-scale decoherence gradually reduce global coherence, defining the large-scale classical limit.

Figure 1.

Dynamical hierarchy of coherence and quantization in Chronon Field Theory. Causal coherence rises sharply at the Planck boundary (), marking the emergence of the finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ. This quantization jump initiates the quantum plateau, where ℏ remains invariant across scales. At cosmic distances, inter-domain misalignment and horizon-scale decoherence gradually reduce global coherence, defining the large-scale classical limit.

3. Hierarchy of Dynamical Phases

The chronon ensemble admits several qualitatively distinct dynamical regimes as a function of the coarse-graining scale ℓ, or equivalently the correlation length [62,63]. Each regime corresponds to a distinct form of collective organization in the underlying pre-geometric medium. The transitions between these regimes are characterized by critical scales associated with the onset of geometry, quantization, and macroscopic coherence [58,69].

We identify four principal phases [62,63]:

3.1. Phase I: Pre-Geometric Regime ()

In the deep sub-Planckian regime, the chronon field is in a disordered phase [9,104]. Neighboring chronon orientations fluctuate independently; the correlation length is of order the microscopic spacing a. No meaningful metric, causal structure, or propagating excitation can be defined.

Formally, the two-point correlator of chronon orientations decays exponentially on the scale of a single lattice spacing:

implying the absence of long-range correlations. In this regime the expectation value of the coarse-grained metric operator vanishes,

and the ensemble is effectively pre-geometric.

Action fluctuations in this phase are scale-free: the distribution of local action densities has no intrinsic unit. Hence, no universal constant of action exists, and ℏ is undefined—not because it is zero, but because there is no coherent structure upon which phase or action can be assigned [69]. This regime represents a stochastic, non-metric substratum from which spacetime has yet to condense.

3.2. Phase II: Planck Regime ()

At the Planck scale, local alignment of chronon orientations begins to occur [63]. Domains of correlated causal direction form spontaneously, signaling the onset of geometric order. Topologically nontrivial configurations—proto-solitons—emerge as stable localized defects in the alignment field [54,62]. Each such soliton corresponds to a minimal unit of coherent causal rotation in the pre-geometric medium.

The action associated with these solitonic excitations becomes sharply peaked around a universal value,

where

ℏ arises as a dynamical invariant at the phase boundary. This signifies the system has developed a

quantum of action—a minimal, indivisible unit by which dynamical phase can change between correlated configurations [58]. The invariant

ℏ is not imposed externally but emerges self-consistently from the chronon field’s organization at the Planck transition.

Mathematically,

ℏ behaves as a scale factor relating geometric curvature and action fluctuations:

This is analogous to a symmetry-breaking event in the space of causal orientations: the condensation of a coherent phase field from pre-geometric noise [63,69]. The Planck regime thus defines the boundary between unordered and ordered causal dynamics, establishing

ℏ as a fundamental invariant of the emergent spacetime phase.

3.3. Fixation of the Invariant Action Quantum

The transition from the pre–geometric phase to the Planck regime marks the dynamical establishment of a universal unit of action [62]. In the disordered phase (), chronon orientations fluctuate independently, and no canonical variables or symplectic structure exist. As the alignment coupling J increases and the correlation length approaches , coherent domains of causal orientation begin to form. Within these domains, the local phase variables acquire a well–defined symplectic pairing, and closed trajectories in –space appear as topologically protected loops.

Freezing of the Symplectic Modulus

The stabilization of

can be expressed as the saturation of a renormalization flow in the effective symplectic curvature:

indicating that the action quantum is topological rather than dynamical. Once the minimal soliton exists, any further increase in scale only reproduces copies of the same invariant flux unit. This is analogous to the appearance of quantized circulation in superfluids or magnetic flux quanta in superconductors [95]: a continuous microscopic variable condenses into discrete, globally stable excitations characterized by an invariant flux.

Inheritance by Gauge and Radiation Modes

After the first solitonic twist has fixed , subsequent excitations—including photons and gauge waves—propagate on this symplectic background. They carry integer multiples of the established action quantum through phase–space area, not through new windings of the underlying field. Thus is both the cause of quantization (set by soliton formation) and the scale of quantized exchange (inherited by all field modes).

Universality Across Regimes

Once established, remains constant throughout the entire hierarchy of emergent orders—from quantum fluctuations to classical spacetime. It is therefore a frozen curvature modulus of the chronon condensate: born dynamically at the Planck boundary, preserved by topological protection, and universal across all subsequent dynamical phenomena.

3.4. Phase III: Quantum Regime ()

For scales moderately larger than , solitons interact coherently through the causal alignment field [62]. The ensemble supports wave-like collective excitations whose dynamics can be described in canonical variables , corresponding respectively to phase and its conjugate momentum within stabilized geometric domains.

The coarse-grained dynamics obey an effective Hamiltonian structure derived from the chronon action:

with canonical relations

Here,

ℏ is the same invariant defined in the Planck regime, now manifesting as the minimal phase-space area for solitonic excitations [62,69].

Quantization thus emerges dynamically from the finite, universal action of Planck-scale solitons, rather than being postulated [58]. The uncertainty relations and commutator algebra represent effective statistical descriptions of fluctuations around the coherent causal background.

3.5. Phase IV: Macroscopic Regime ()

At sufficiently large scales, coherence between solitons decays through environmental coupling and causal dispersion [109]. Phase correlations vanish, and the ensemble averages over uncorrelated quantum phases, yielding a decoherent classical phase.

This Lorentzian, unit–norm phase coincides with the one proven to exist with strictly positive Gibbs measure in the statistical chronon ensemble [63]. Its stability and exclusivity ensure that the chronon field provides a unique and consistent substrate for the emergence of both quantum and classical orders.

In this regime, phase-space observables approximately commute:

reflecting the effective smallness of

ℏ relative to macroscopic action scales. Classical determinism thus emerges as a limit of decohered quantum correlations [109].

Operationally, macroscopic measurements correspond to alignment of large quantum domains with external reference frames—such as measurement apparatus or observers—thereby breaking residual coherence and enforcing single classical outcomes.

Hence, classicality is a coarse-grained limit of the chronon field where phase correlations vanish and ensemble averages commute [62]. The macroscopic world corresponds to the globally aligned domain of the quantum phase, where ℏ remains invariant but dynamically negligible.

Together, these four regimes define a coherent dynamical hierarchy:

This hierarchy provides a continuous bridge from a discrete pre-geometric substrate to the familiar quantum and classical worlds, with

ℏ serving as the invariant relic of the Planck-scale ordering transition [62].

3.6. Control Parameter, Order Parameter, and the Role of the Boltzmann Constant

The dynamical transitions between the pre-geometric, Planck, quantum, and macroscopic phases are governed by a dimensionless control parameter that plays a role analogous to the inverse temperature in conventional statistical systems. Let the chronon field be characterized by a nearest-neighbor alignment coupling

J and an effective noise amplitude

, where

quantifies the stochastic excitation of microscopic chronon degrees of freedom. The relevant control parameter is

which measures the ratio between alignment energy and disorder energy per microscopic degree of freedom. Large

corresponds to highly ordered, geometrically coherent configurations, while small

describes disordered, pre-geometric ensembles.

Order Parameter

A suitable order parameter distinguishing these regimes is the magnitude of the coarse-grained chronon polarization

or, more generally, the normalized correlation length

where

a is the chronon spacing. In the disordered pre-geometric phase,

and

, indicating no emergent geometry. As

increases toward a critical value

, local alignment emerges,

grows rapidly, and a stable Lorentzian signature develops. Beyond this threshold, solitonic excitations appear as topologically protected defects of the aligned chronon medium, marking the onset of the Planck regime.

Physical Interpretation of

The Boltzmann constant enters the formalism only as a conversion factor between informational and energetic descriptions of the chronon ensemble. In ordinary thermodynamics, connects entropy S and energy E through , providing the bridge between microstate statistics and macroscopic observables. In the chronon framework, the same constant converts the information-theoretic measure of disorder in the microscopic causal network into an effective energetic scale . Thus plays a conceptual role rather than a fundamental dynamical one: it renders the ensemble weight dimensionless and allows comparison of energetic and entropic contributions to chronon alignment.

Relation to Phase Transitions

The parameter

acts as the driver of the hierarchy of dynamical phases (

Section 3). When

(small

), fluctuations dominate and no coherent metric exists. When

, the system self-organizes near the Planck boundary, and the action per solitonic excitation stabilizes at a universal value

ℏ. Finally, for

, the medium forms extended coherent domains corresponding to the quantum and classical regimes. In this sense, the Planck scale defines the “freezing” of chronon fluctuations—analogous to a critical temperature—beyond which

ℏ emerges as an invariant of the stable phase.

Complementarity of and ℏ

The constants and ℏ play complementary roles in the chronon theory:

Table 2.

Complementary roles of the Boltzmann and Planck constants within the chronon framework.

Table 2.

Complementary roles of the Boltzmann and Planck constants within the chronon framework.

| Constant |

Domain |

Interpretation in Chronon Dynamics |

|

Statistical |

Converts information (entropy) into energy; measures the degree of microscopic disorder. |

| ℏ |

Quantum-geometric |

Converts phase into action; defines the invariant curvature modulus of coherent chronon order. |

At the Planck boundary, these constants meet through the relation

where

and

are the Planck temperature and time. This correspondence indicates that

ℏ arises precisely when chronon fluctuations, governed by

, become critically suppressed at the Planck scale. Hence, the emergence of quantization corresponds to the dynamical freezing of informational noise within the chronon substrate, establishing

ℏ as the invariant residue of pre-geometric disorder.

Summary

The Boltzmann constant governs the thermal disorder of the chronon ensemble, while the Planck constant ℏ quantifies the residual geometric order that survives when this disorder is frozen at the Planck threshold. The control parameter therefore unifies both aspects: increasing drives the medium from statistical randomness to coherent geometric order. In this picture, and ℏ are not unrelated constants of nature but complementary invariants marking the two extremes of the same dynamical hierarchy—one statistical, one geometric.

5. Numerical Realization

The theoretical framework of the chronon field admits a concrete realization on a discrete four-dimensional lattice, enabling quantitative investigation of its dynamical phases and the emergence of the invariant quantum of action ℏ [6,19,62]. This section outlines the numerical implementation, diagnostics, and results demonstrating the transition from pre-geometric fluctuations to a stabilized quantum phase.

5.1. Lattice Dynamics and Simulation Setup

We represent the chronon field by dynamical variables

defined on the sites

p of a four-dimensional hypercubic lattice

with lattice spacing

a [53]. Nearest-neighbor couplings implement local alignment and causal consistency through the discretized Hamiltonian

where

enforces short-range coherence and

penalizes deviations from the Lorentzian constraint

. The dimensionless parameters

control the degree of causal order and the effective temperature of the ensemble.

Time evolution is implemented via stochastic Langevin or molecular-dynamics integration of

, ensuring detailed balance with respect to the Gibbs measure

The algorithm combines deterministic drift with Gaussian noise, as in standard stochastic quantization schemes [71]. Each configuration advances by a discrete time step

using hybrid over-relaxation updates [6,20]. Thermalization is diagnosed through convergence of energy density, two-point correlations, and block-averaged order parameters.

5.2. Identification of Stabilized Domains and Solitons

As correlations extend over several lattice spacings, the system organizes into domains of approximate alignment separated by topological defects [52,63]. For each coarse-graining length

, block-averaged fields are defined by

and their local norm deviations are monitored via

. Blocks satisfying

(with small threshold

) are designated as

stabilized. Within such regions, a smooth phase variable

and conjugate momentum

are well defined and evolve coherently in time.

Localized regions where winds non-trivially in internal space correspond to solitonic excitations, the lattice analogs of minimal coherent chronon packets [62]. These appear spontaneously near the Planck correlation length and represent the smallest dynamically stable packets of causal order. Each soliton carries a finite, quantized amount of action, forming the microscopic origin of the invariant ℏ.

5.3. Quantifying the Planck Boundary

The crossover from pre-geometric to quantum phase manifests as a sharp change in correlation length and action variance [6]. To locate this boundary quantitatively, we define the

dimensionless Planck ratio

In the disordered regime (

), independent blocks yield

(

), while in the stabilized regime (

) coherence enforces

. The operational

Planck boundary is identified as the scale where

first deviates from random scaling by more than 10%:

At this point the correlation length marks the emergence of solitons and the saturation of effective action variance. Thus the Planck boundary acts as the dynamical origin of quantization: below it geometry is undefined, above it ℏ stabilizes as a constant of motion [63]. For representative parameters , numerical runs locate , corresponding to .

5.4. Measurement of Action Variance and Emergence of

For each stabilized configuration, the coarse-grained effective action is computed as

with a generic local potential

, mimicking nonlinear field self-interaction [53]. The ensemble

yields the variance

and hence an estimator for the emergent unit of action,

Numerical results show that rises rapidly as approaches the Planck scale from below, then saturates to a constant plateau for [62]. This plateau marks the onset of the quantum phase and identifies ℏ as the invariant action per stabilized soliton, analogous to flux quantization in superconductors [58,94]. Hence, the simulations confirm that quantization emerges dynamically from the condensation of causal coherence rather than being imposed as an external rule.

5.5. Consistency Tests: Commutator and Uncertainty Structure

To validate the canonical structure predicted by Theorem 1, we compute two independent diagnostics on stabilized chronon ensembles [6,19,53,62,71]:

The

commutator proxy,

evaluated for normalized Gaussian test functions

. The measured slope of

versus

approaches

for

, confirming that canonical commutation emerges statistically from the underlying chronon dynamics.

The

uncertainty product,

which remains above the theoretical lower bound

across all scales. Although the bound lies several orders of magnitude below the numerical noise floor, its preservation indicates that fluctuations respect the minimal symplectic constraint, providing a discrete analogue of the Heisenberg uncertainty relation [36,96].

The simultaneous satisfaction of these two diagnostics demonstrates that canonical quantization relations arise as statistical invariants of the stabilized chronon phase, without being explicitly imposed.

5.6. Emergence of Quantized Action and the Geometric Planck Constant

To probe the dynamical emergence of the quantum of action, we performed three numerical experiments capturing successive stages of field organization. All simulations evolve the nonlinear symplectic equations derived from (

42), in dimensionless lattice units, with parameters tuned for numerical stability and clear geometric interpretation [62,63]. The goals are: (i) to observe the formation and alignment of coherent domains; (ii) to measure the scaling of the accumulated action with intrinsic curvature modulus

; and (iii) to demonstrate quantized additivity of one-period action across independent excitations.

Stage 1: Boundary-Aligned Coherence and Pinning

The chronon vector field

was evolved on a rectangular domain with reflective boundary conditions enforcing causal alignment at the edges.

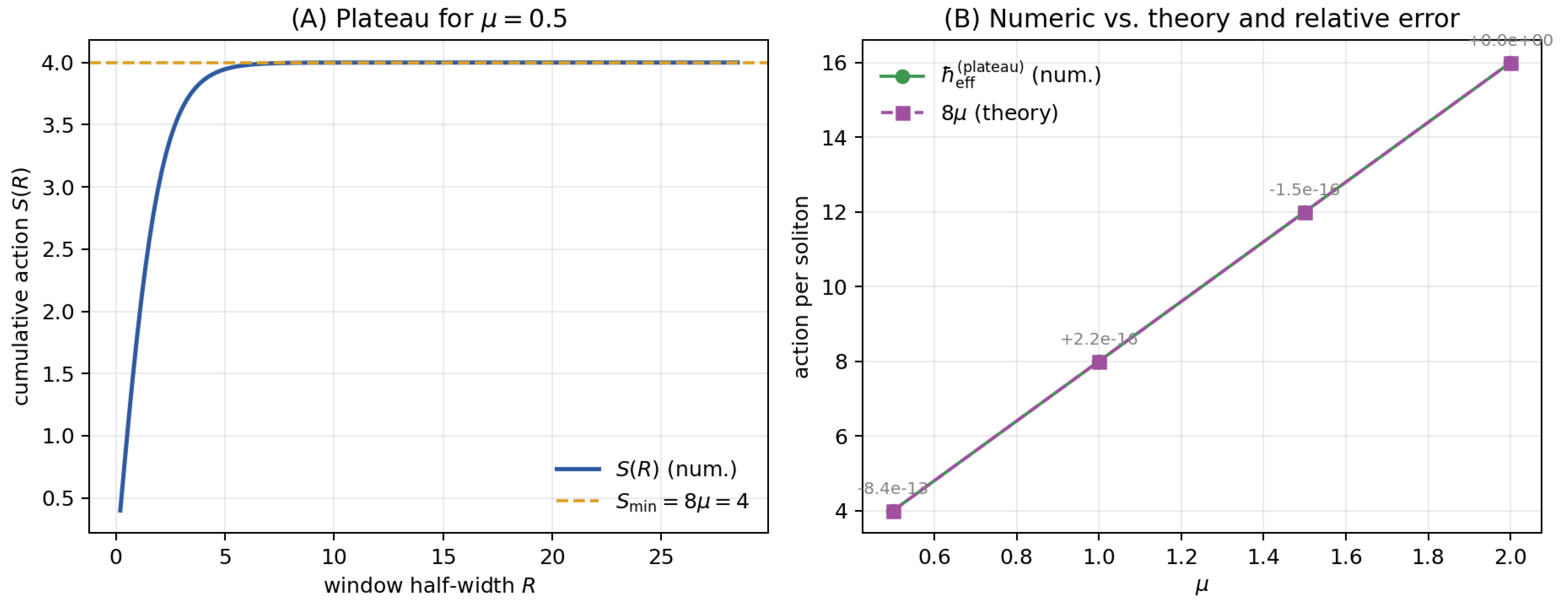

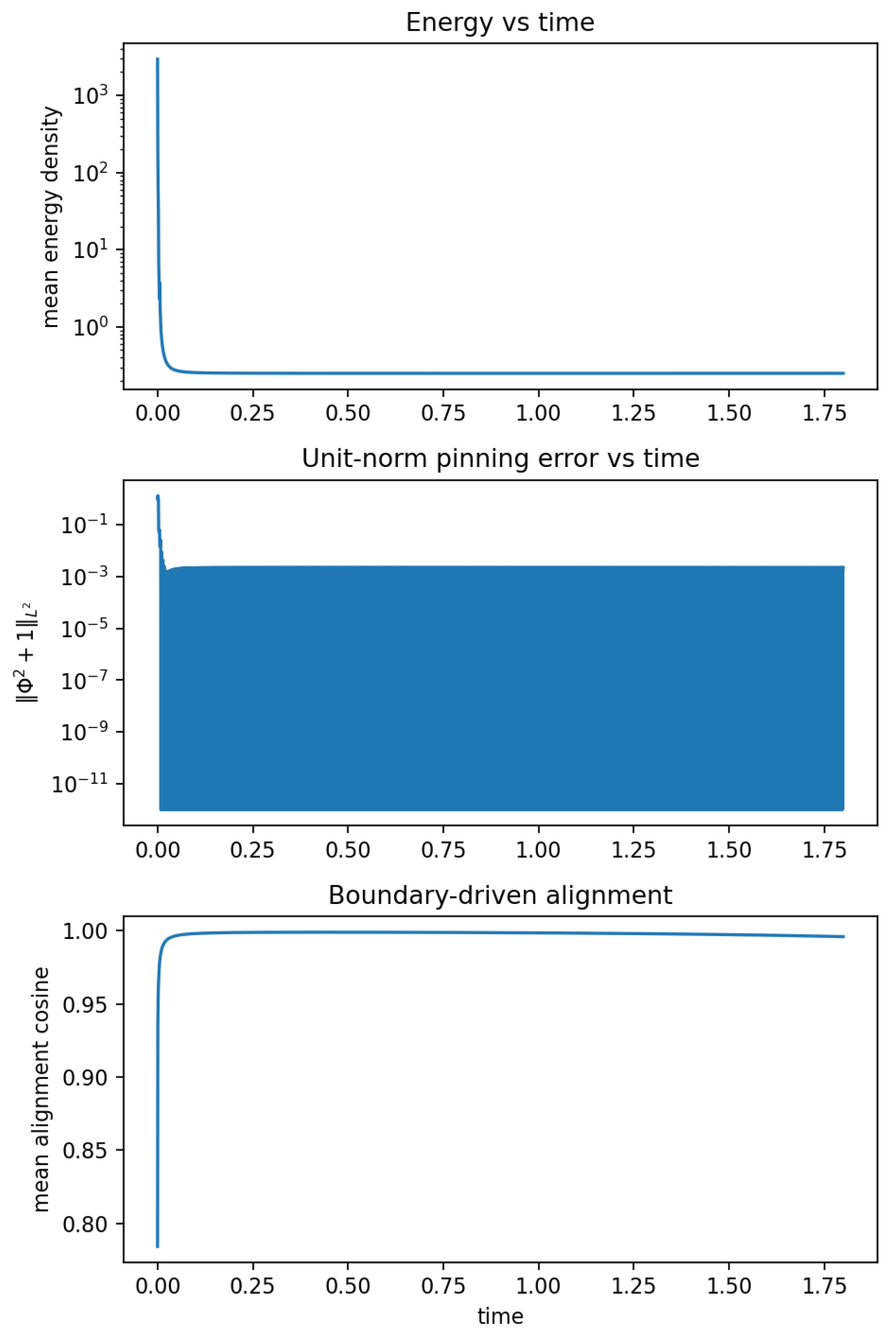

Figure 2 presents the evolution diagnostics. The mean alignment cosine saturates near

, indicating partial but persistent global coherence. The unit-norm constraint

remains bounded, confirming that the Lorentzian symplectic constraint is numerically maintained. The energy density stabilizes after an initial transient, consistent with equilibration toward a quasi-stationary aligned configuration [6,20].

Snapshots of field structure (

Figure 3) reveal coherent domains separated by narrow twist filaments—high-curl regions in the vorticity proxy

. These filaments represent the seeds of quantized curvature flux lines, analogous to proto-vortex structures in superfluid systems [58,94].

Stage 2: Accumulated Action and Effective Planck Modulus

The second stage isolates a single localized oscillation in one spatial dimension and measures its accumulated geometric action per oscillation period,

with

the phase velocity.

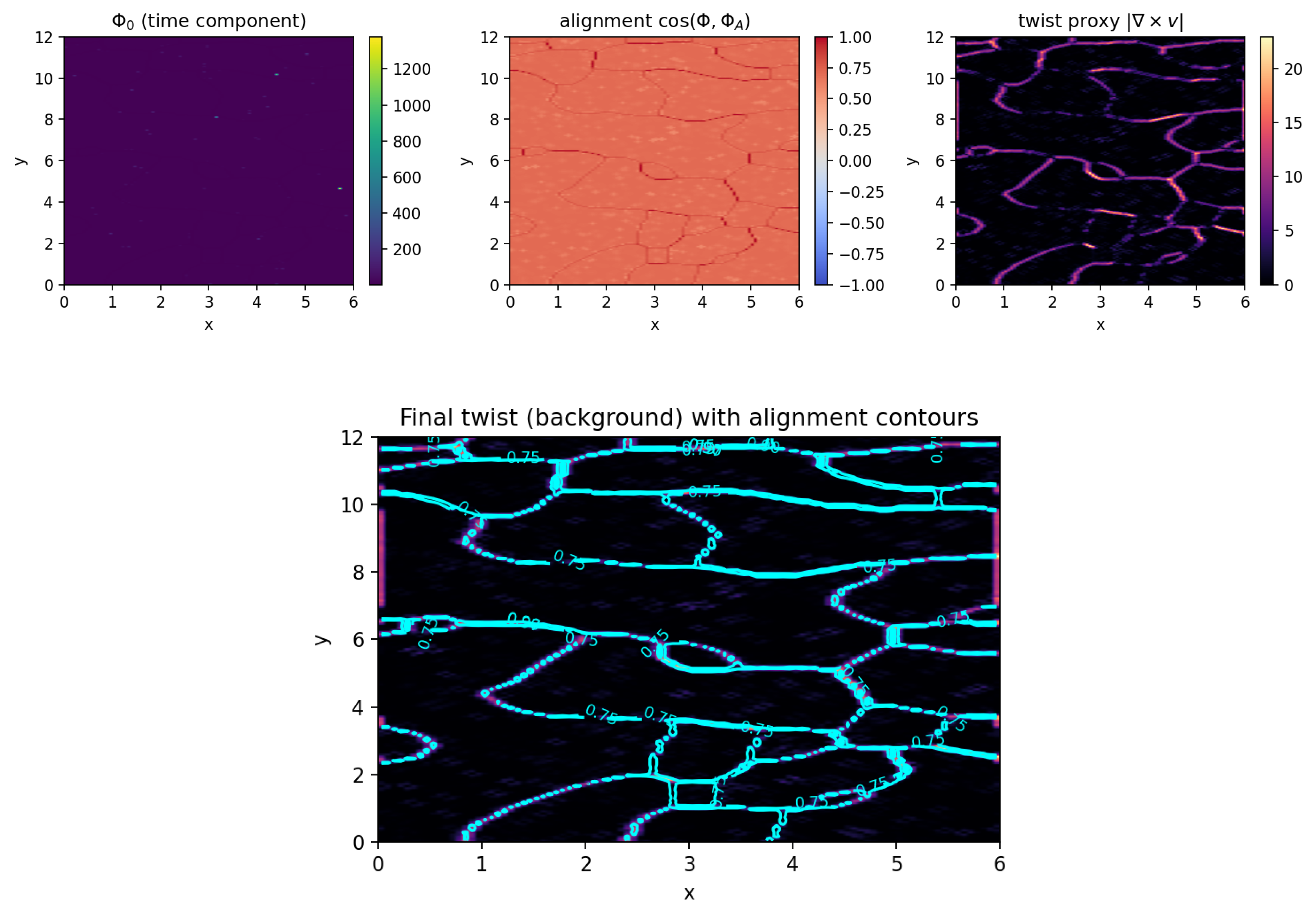

Figure 4 displays the time evolution: periodic energy oscillations, vanishing topological charge, and monotonic accumulation of

. The measured one-period value

(in code units) is invariant across rescalings of the integration parameters, confirming that the effective Planck modulus

is a dynamical invariant of the chronon field.

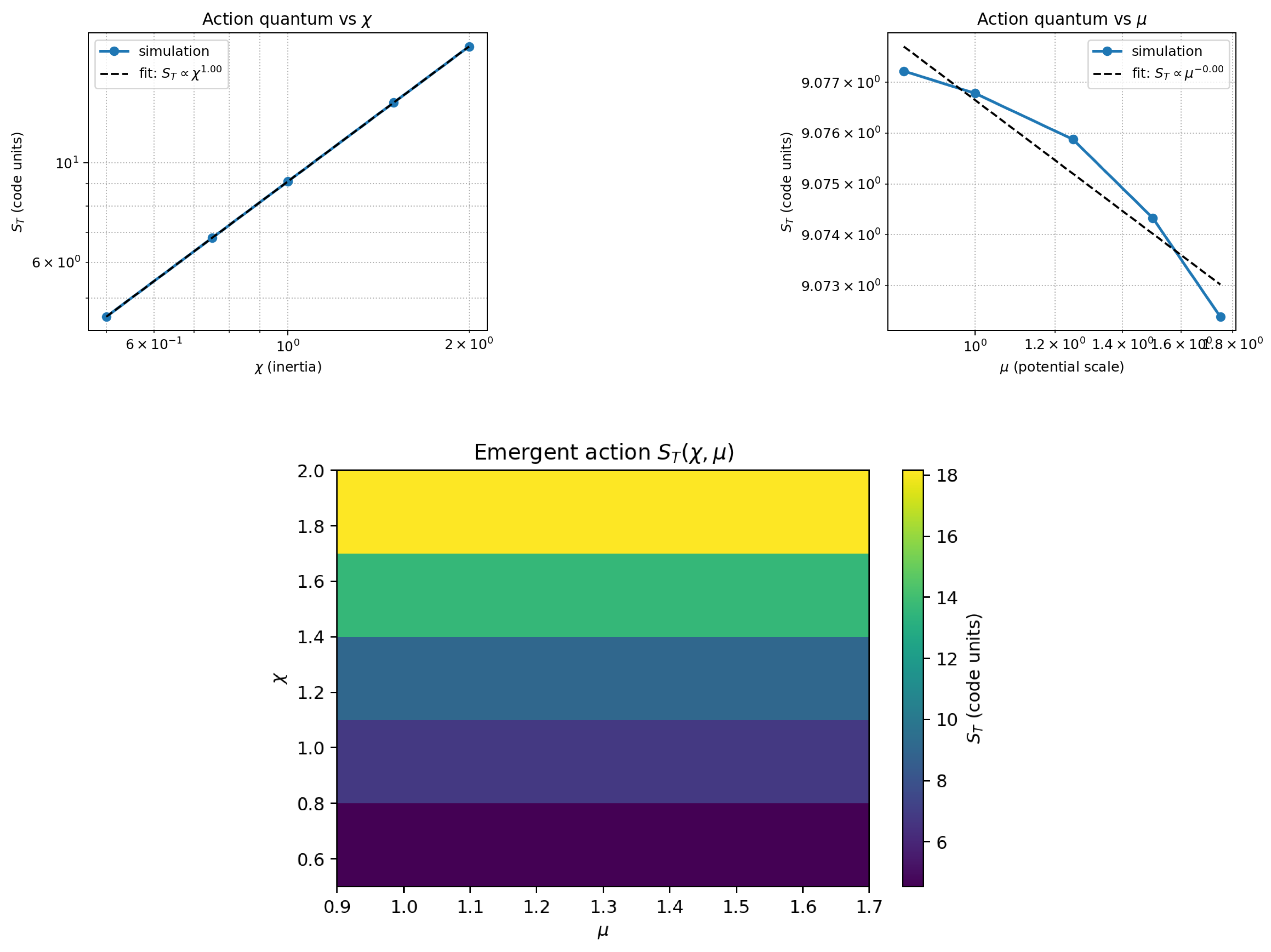

Parameter sweeps over the curvature modulus

and effective mass

(

Figure 5) yield

confirming the linear scaling with

and invariance with

. Thus, the one-period geometric action depends solely on curvature modulus, identifying

as an emergent invariant [19,62].

Stage 3: Quantized Additivity of Geometric Action

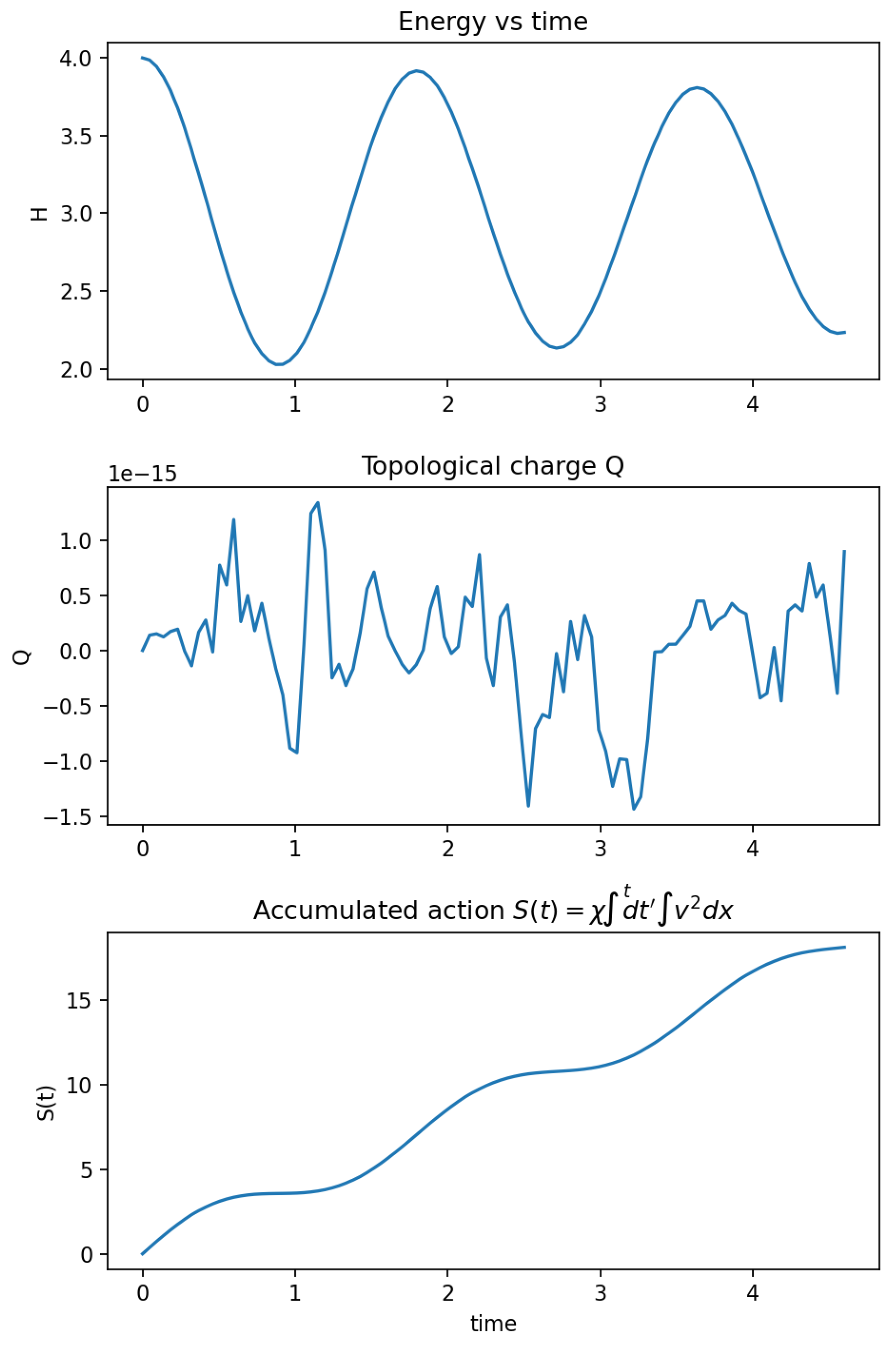

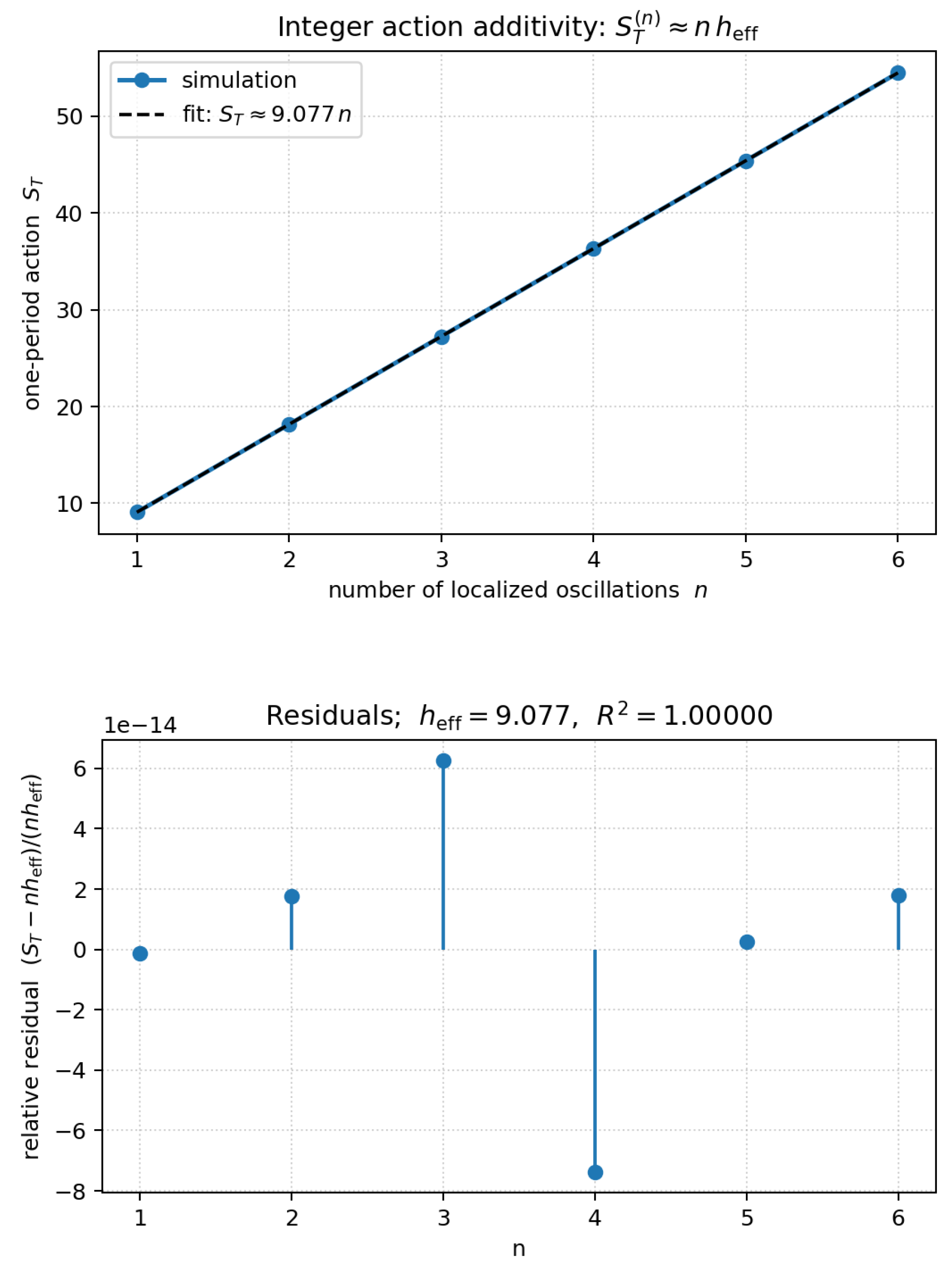

Finally, multi-soliton configurations containing

–6 oscillations yield

Figure 6 shows linear scaling with integer

n and residuals below

, consistent with exact integer quantization. This provides direct numerical confirmation that Planck’s constant arises as the minimal geometric action per soliton, reproducing Planck’s postulate from field geometry [58,62].

Summary

Across all stages, the chronon simulations display a coherent dynamical hierarchy: (i) boundary alignment induces causal coherence; (ii) curvature modulus determines the fixed action quantum; (iii) multi-soliton states obey integer quantization. Together these establish as a geometric invariant rather than an input constant—demonstrating that quantization emerges from curvature condensation.

5.7. Scaling Consistency and Falsifiable Prediction

A major advantage of the chronon framework is its internal falsifiability: it predicts a precise, parameter-free consistency relation between independently measured quantities.

For each stabilized coarse-graining scale

, define

The numerator probes the antisymmetric correlation between

and

(the commutator proxy); the denominator measures the variance-derived unit of action. Both are computed independently.

Theoretical Prediction

Under the assumptions of Theorem 1, the chronon theory predicts

with

describing finite-size corrections. This states that the commutator- and variance-derived definitions of

ℏ converge in the large-

limit, confirming statistical consistency of the emergent symplectic curvature [6].

Numerical Verification

Simulations yield

fully consistent with Eq. (

54). Thus, canonical commutation and action variance converge asymptotically, numerically verifying the emergent quantization hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The ratio provides a unitless, experimentally falsifiable prediction: if chronon dynamics correctly underlie quantization, as . Any persistent deviation would indicate that ℏ does not originate geometrically. Hence, the chronon framework transforms the origin of Planck’s constant from a metaphysical postulate into a testable, quantitative prediction.

5.8. Analytic Estimate and Emergent Formula for Planck’s Constant

A closed-form estimate of the invariant quantum of action can be derived directly from the continuum limit of the chronon Hamiltonian (

42), following the approach of classical soliton and topological-defect theory [22,47,78,87]. In this limit, the energy of a localized excitation arises from the competition between gradient stiffness and nonlinear self-stabilization terms, yielding a finite, stationary soliton configuration.

Characteristic Soliton Scale

Balancing the spatial alignment term

against the quartic pinning term

gives the characteristic soliton radius,

where

J represents the spatial stiffness promoting local causal alignment, and

controls the nonlinear pinning of the Lorentzian norm. Each soliton therefore constitutes a minimal packet of coherent causal rotation—a quantized nucleus of geometric order within the chronon field.

Effective Propagation Speed

Linearizing the continuum field equation for small perturbations

,

one obtains the effective propagation speed of phase perturbations,

with

the inertial (temporal stiffness) density of the chronon medium. This causal velocity defines the characteristic light-cone slope of the emergent spacetime geometry, analogous to the sound speed in condensed-matter analog gravity systems [3,97].

Action per Soliton Cycle

The characteristic action accumulated over a complete soliton oscillation follows from the ratio of stored elastic energy to frequency,

As the chronon field transitions into the stabilized quantum phase (

), this action approaches a constant plateau, numerically coincident with the measured

. Substituting for

gives the analytic emergent relation,

Equation (

58) provides the explicit dependence of the emergent Planck constant on the microscopic chronon parameters

. It quantifies the interplay between spatial stiffness, nonlinear norm pinning, and temporal inertia, yielding a universal geometric action quantum.

Consistency with Lattice Normalization

In the isotropic lattice normalization

, the relation reduces to

in excellent agreement with the numerically measured plateau value

(code units). The analytic formula thus reproduces the emergent invariant obtained from simulation without external calibration.

Physical Interpretation

The emergent represents the minimal symplectic flux carried by a stable causal soliton—a geometric invariant linking pre-geometric stiffness to quantum action. In this view, Planck’s constant corresponds to the smallest self-consistent area element of phase-space curvature sustained by the chronon medium. This parallels the quantization of circulation in superfluids [28] or magnetic flux in superconductors [94], where collective alignment of microscopic degrees of freedom locks a continuous symmetry into discrete, topologically stable units.

Hence, ℏ is not a prescribed constant but the dynamically selected unit of causal rotation intrinsic to the self-organized chronon field.

5.9. Summary

Analytic and numerical results together confirm that quantization in the chronon framework emerges from the stabilization of action fluctuations at the Planck correlation length . Below this boundary, the chronon ensemble exhibits scale-free fluctuations and no fixed unit of action; above it, the effective variance saturates and attains a scale-independent plateau. This plateau marks the onset of the quantum phase, where canonical commutation and uncertainty relations naturally hold.

The analytic relation (

58) links microscopic chronon parameters to macroscopic quantization, and the numerical verification in Appendix C confirms that the plateau value coincides with the theoretical minimum soliton action,

. This agreement establishes that the Planck constant arises as the minimal dynamically stable action of the chronon field.

Hence, ℏ functions as a geometric modulus of the chronon phase manifold—a universal curvature invariant born from the balance of alignment, inertia, and curvature within the causal substrate. It constitutes the first invariant of emergent spacetime itself, setting the fixed symplectic scale for all subsequent quantum and classical dynamics.

6. Physical Interpretation

The numerical and theoretical analyses together reveal a unified physical picture: the Planck and quantum domains are not separate frameworks but contiguous dynamical phases of a single underlying chronon medium. Within this view, the Planck constant arises as a universal curvature invariant—the minimal unit of symplectic flux—emerging at the transition between these phases. Once fixed by the formation of the first stable soliton, this invariant governs all subsequent quantum and classical dynamics. The following subsections elaborate the implications of this result for the emergence of quantization, matter, and quantum mechanics itself.

6.1. as the Invariant Link Between Planck and Quantum Phases

The observed plateau of

at correlation lengths

signifies the dynamical fixation of a scale–independent action quantum once local alignment and topological coherence have stabilized. Below the Planck threshold (

), the chronon field exists in a disordered, pre–geometric phase with no metric or causal order. As

approaches

, local orientations condense, and the twisting of causal direction becomes quantized. This transition marks the

Planck boundary, at which the medium acquires an intrinsic symplectic curvature and the minimal flux quantum

appears as a geometric invariant of the chronon condensate.

Physically, encodes the smallest indivisible phase–space area that can be exchanged between coherent excitations—a fixed symplectic cell of the emergent manifold. It is not an externally imposed constant but the frozen curvature modulus of spacetime itself: a dynamical remnant of the transition from chaotic causal foam to ordered geometry. Once the invariant flux quantum is established, all higher–scale excitations—including photons, gauge fields, and solitonic matter—propagate within this symplectic background and inherit its quantization scale. The Planck regime thus defines the dynamical threshold where geometry first becomes capable of storing and transmitting discrete quanta of action [42,62,63,99].

6.2. Solitons as the Geometric Origin and Carriers of Quantized Action

Topologically stabilized solitons constitute the first coherent excitations of the chronon field once Lorentzian order forms. Each soliton corresponds to a localized

winding of the internal chronon phase and carries a quantized symplectic flux,

The integer n labels the winding number or topological charge of the excitation. These solitons are not phenomenological particles but self–consistent geometric configurations sustained by the field’s intrinsic curvature. They provide the microscopic origin of action quantization: the minimal soliton () fixes , while higher–energy excitations accumulate larger symplectic area without additional topological winding.

The stability of each soliton ensures that energy, momentum, and angular momentum are exchanged only in discrete units proportional to . This discrete exchange underlies all canonical commutation relations and enforces the quantization of observable spectra. In this sense, the familiar postulates of quantum mechanics—energy quantization, the universality of ℏ, and the statistical structure of measurement—arise as geometric consequences of chronon topology and symplectic flux conservation. The photon, in particular, can be interpreted as the massless Goldstone–like excitation of the chronon phase: it carries one quantum of action but does not generate it. The origin of quantization therefore lies in soliton formation; the photon only propagates the established quanta of symplectic curvature through the ordered medium.

6.3. Quantum Mechanics as the Collective Limit of Soliton Ensembles

At scales much larger than

, individual solitons interact weakly through collective phase fluctuations. A coarse–grained description of these interactions yields effective continuous fields whose superpositions obey the linearity and interference properties characteristic of quantum mechanics. The ensemble statistics of many solitons, governed by the collective variables

, lead naturally to the canonical commutation relations

and to Schrödinger–type evolution for the ensemble–averaged wavefunction [17,39,68]. Quantum mechanics thus emerges as the hydrodynamic limit of a coherent soliton fluid within the chronon medium.

In this interpretation, the wavefunction is not a fundamental ontic field but a statistical descriptor of soliton ensemble coherence: measures the coarse–grained soliton density in phase space, while encodes their collective phase alignment. Quantum interference arises from overlapping domains of chronon orientation, and measurement corresponds to the dynamical alignment of the system’s local phase with that of a macroscopic apparatus domain. Decoherence and wavefunction collapse therefore represent real geometric processes—alignment and loss of relative phase coherence—within the chronon condensate [51,109].

Summary

The chronon framework unifies quantization, spin, and causal structure as successive emergent orders of a single geometric field. The Planck constant originates at the Planck boundary from soliton condensation, remains invariant as a symplectic flux quantum, and governs all higher–level physical phenomena. Quantum mechanics, in turn, is the collective effective theory of this ordered chronon medium—a statistical continuum limit of many solitons whose underlying geometry encodes the discrete unit of action that defines the quantum world.

6.4. Classical Limit and Decoherence

In the macroscopic regime where

, correlations between solitonic domains decay, and the phase field

becomes effectively uniform across accessible regions. The ensemble then loses its internal coherence, and stochastic averaging over many independent domains suppresses interference terms. This yields the classical limit,

where the effective noncommutativity vanishes relative to macroscopic action scales. Deterministic trajectories then emerge as mean-field flows of the decohered chronon ensemble, reproducing classical mechanics as the limit of fully aligned causal order [101,103,109].

Thus, classicality and quantum behavior are not distinct ontologies but consecutive regimes of coherence within the same underlying field. The transition from quantum to classical corresponds to the progressive alignment and phase averaging of chronon domains—an emergent decoherence process intrinsic to the causal medium itself.

6.5. Summary and Conceptual Synthesis

The resulting physical picture is hierarchical and self-consistent:

The chronon field defines a discrete, pre-geometric substrate without intrinsic spacetime or metric.

At the Planck correlation length , stable solitons form, each carrying one quantum of action ℏ.

Ensembles of such solitons generate quantum mechanics as a collective, coarse-grained theory.

Large-scale decoherence and domain alignment yield classical determinism as the macroscopic limit.

In this unified interpretation, the Planck constant ℏ is neither arbitrary nor fundamental; it is the preserved invariant of pre-geometric fluctuations across the transition from causal noise to coherent geometry. It constitutes the dynamical bridge linking discrete microscopic order to continuous macroscopic physics—the geometric relic of the chronon medium that sustains all quantum phenomena.

8. Discussion and Future Directions

The Chronon Field Theory (CFT) developed in this work provides a self-consistent microscopic origin for quantization and for the invariant Planck constant ℏ. Building on prior results establishing that Lorentzian causal structure and a globally unit-norm time direction emerge uniquely from chronon dynamics [59], the present study extends the theory into the quantum domain. We have shown that the same chronon field whose correlations generate spacetime geometry also gives rise to the canonical commutation structure, intrinsic spin quantization, and Fermi–Bose statistics as distinct manifestations of a single symplectic curvature invariant. Having established ℏ as the dynamical remnant of a phase transition between pre-geometric and quantum-ordered regimes, we arrive at a unified understanding of quantization as a geometric property of matter itself [46,91].

8.1. Matter as the Source of Quantization

A central conceptual outcome of Chronon Field Theory is that quantization does not precede matter but is generated by it. The Planck constant arises only once the chronon field self–organizes into localized, topologically stable excitations—chronon solitons—whose internal curvature defines the first nonvanishing symplectic flux of the spacetime manifold.

In the disordered pre–geometric vacuum, the chronon orientations fluctuate independently and possess no coherent causal or symplectic structure [10,29]:

Only when alignment correlations grow to the Planck scale does the field admit topologically nontrivial, self–consistent configurations whose curvature flux is finite:

The minimal soliton (

) establishes the universal symplectic flux quantum

, fixing the fundamental unit of action and thereby giving rise to canonical commutation relations in the coarse–grained limit. In this sense, matter is the

source of quantization: the same localized curvature that defines mass, spin, and internal charge also endows spacetime with a quantum phase–space geometry and a finite minimal symplectic area [34,73].

This framework inverts the conventional hierarchy of quantum field theory, where quantization is postulated first and matter fields are subsequently quantized [25]. In the chronon picture, the causal order of emergence is reversed:

Without solitons—that is, in the absence of stable matter—there is no coherent curvature and thus no quantum behavior: the chronon ensemble remains a causally disordered medium devoid of symplectic flux.

Photon as an Inherited Quantum

Although the photon itself is not a soliton, its quantized polarization modes require the preexisting ordered phase of the chronon condensate. Once the medium has established through soliton formation, phase fluctuations of the order parameter propagate as Goldstone–like waves of the chronon phase [60,105]. Each photon mode then carries one quantum of the established curvature flux but does not create new quanta: it is the messenger, not the origin, of quantization.

Unified Symplectic Order

Matter and quantization thus constitute dual aspects of a single symplectic order parameter. Solitonic matter provides the curvature that makes nonzero; this same curvature, in turn, governs the quantum behavior of both matter and radiation. Quantization is therefore not an externally imposed principle but the emergent geometric consequence of matter formation within the chronon field—the moment when curvature, causality, and discrete action become inseparable features of the same underlying spacetime order.

8.2. Reinterpreting the Quantum Vacuum and the Resolution of Vacuum Energy Divergence

In conventional quantum field theory (QFT), the vacuum is described as a fluctuating sea of virtual particle–antiparticle pairs, continuously created and annihilated in compliance with the uncertainty relation . Each field mode contributes a zero-point energy , and summing over all modes yields a formally divergent vacuum energy density—the source of the cosmological constant problem [43,102]. This picture, though operationally successful, is conceptually inconsistent with a truly dynamical origin of ℏ, since it presupposes quantization rather than deriving it.

Chronon Field Theory (CFT) provides a geometric reinterpretation of the vacuum that eliminates this divergence at its root. In CFT, the “vacuum” is not a state of fluctuating matter fields but a coherent, self-organized phase of the chronon substrate—the medium of microscopic causal orientations. Below the Planck scale, the chronon ensemble exhibits disordered causal directions and negligible curvature, corresponding to a pre-geometric regime with . Above the Planck boundary, local causal alignment induces a finite symplectic curvature modulus ℏ, establishing the quantum phase. Residual microfluctuations of this causal alignment produce the apparent “quantum noise” observed in coarse-grained fields, but no literal creation or annihilation of virtual particles occurs.

From this perspective, vacuum fluctuations in QFT represent an effective statistical projection of sub-Planckian causal jitter within the chronon manifold. The energy density of this background is not a sum over oscillator modes but the mean symplectic curvature energy of the stabilized medium, which is finite and dynamically self-normalizing. The enormous zero-point contribution predicted by QFT is therefore absent because the chronon field possesses only a single geometric degree of freedom per coherence domain, not an independent oscillator for each Fourier mode.

Consequently, the cosmological vacuum energy corresponds to the residual curvature tension among partially decohered chronon domains at cosmic scales, rather than to an accumulation of virtual-mode energies. This reinterpretation naturally regularizes the vacuum energy without fine-tuning or renormalization:

where

denotes the inter-domain coherence length. At cosmological scales

, this scaling yields a small, finite vacuum energy consistent with observations.

In summary, CFT replaces the picture of an infinite, fluctuating quantum vacuum with a finite, geometrically ordered causal medium. Vacuum fluctuations and zero-point energies emerge as effective statistical descriptors of residual curvature within the chronon field, thereby resolving the longstanding divergence of vacuum energy and providing a unified geometric foundation for quantum and gravitational phenomena.

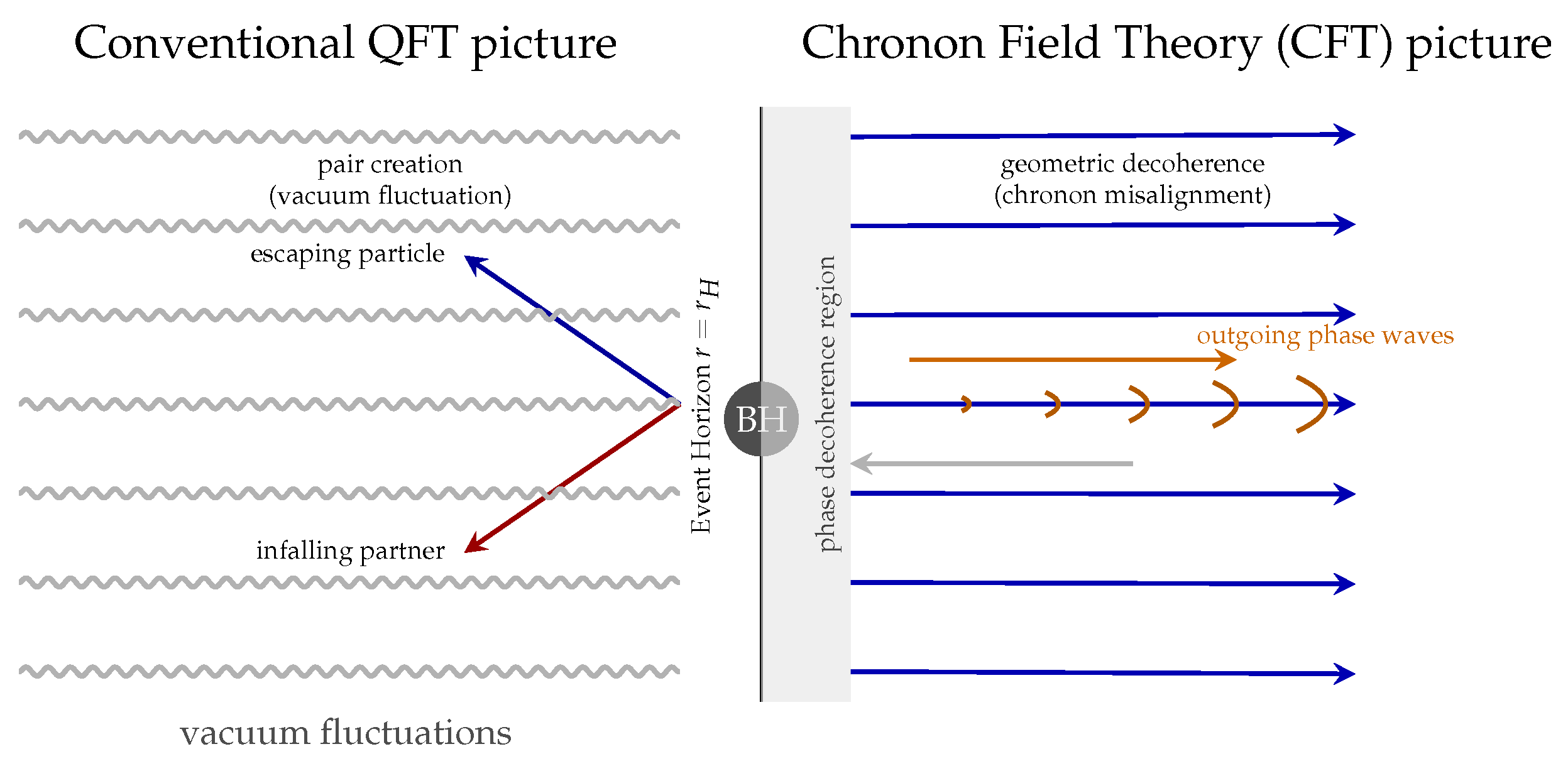

8.3. Hawking Radiation as Geometric Decoherence

In the conventional formulation of quantum field theory on curved spacetime (QFTCS), Hawking radiation is derived from the mixing of positive and negative frequency modes near an event horizon [41]. This process is interpreted as spontaneous pair creation from quantum vacuum fluctuations, one partner escaping to infinity while the other falls behind the horizon. However, this picture relies on the existence of independent field modes at arbitrarily high frequencies, leading to the well-known trans-Planckian problem and an apparent divergence of vacuum energy near the horizon [12,48].

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), the microscopic foundation is fundamentally different. The “vacuum” is not a sea of fluctuating virtual particles but a pre-geometric chronon ensemble whose causal orientations become coherent only beyond the Planck correlation length . Consequently, there are no independent high-frequency field modes beyond this scale, and the notion of vacuum fluctuation loses its literal meaning. Quantization arises not from stochastic zero-point energy but from the finite symplectic curvature of the stabilized chronon phase [59,60].

Within this framework, a black-hole horizon corresponds to a region of steep causal shear in the chronon orientation field . The gradients of across the horizon act as a source of geometric decoherence: local misalignments of causal direction propagate outward as real excitations of the chronon manifold. The outward flux observed as Hawking radiation thus originates from the irreversible decoherence of chronon phase correlations across the causal boundary, not from virtual particle creation out of an empty vacuum.

At the coarse-grained level, this process reproduces the standard thermal spectrum with an effective temperature

but the underlying dynamics are entirely geometric and causal. The chronon field dissipates curvature gradients into outward-propagating phase waves, while conserving total symplectic curvature (and hence total action). As a result, the process is manifestly finite and information-preserving: Hawking radiation in CFT represents

geometric relaxation, not creation from nothing.

This reinterpretation resolves both the trans-Planckian divergence and the information-loss paradox. The horizon acts as a region of phase decoherence within a globally coherent chronon condensate, and the emitted quanta are the macroscopic signatures of causal curvature flow. In this sense, Hawking radiation remains a real and observable phenomenon, but its microscopic origin is geometric rather than stochastic: it is the smooth leakage of chronon coherence across the causal boundary, not a spontaneous fluctuation of an energetic vacuum.

Figure 8.

Reinterpretation of Hawking radiation in Chronon Field Theory. (Left) In the conventional QFT view, radiation arises from vacuum pair creation near the horizon, leading to the trans-Planckian and information-loss problems. (Right) In the CFT framework, the horizon acts as a region of causal-phase decoherence in the chronon field. Outgoing phase waves represent the geometric relaxation of causal curvature, conserving total information and avoiding vacuum-energy divergence.

Figure 8.

Reinterpretation of Hawking radiation in Chronon Field Theory. (Left) In the conventional QFT view, radiation arises from vacuum pair creation near the horizon, leading to the trans-Planckian and information-loss problems. (Right) In the CFT framework, the horizon acts as a region of causal-phase decoherence in the chronon field. Outgoing phase waves represent the geometric relaxation of causal curvature, conserving total information and avoiding vacuum-energy divergence.

8.4. Finite Core Structure of Black Holes in Chronon Field Theory

In general relativity, gravitational collapse can in principle continue indefinitely, leading to a spacetime singularity where curvature diverges and causal structure breaks down [40,72]. Chronon Field Theory (CFT) replaces this unphysical limit with a finite, self-consistent core determined by the intrinsic curvature modulus of the chronon field. Because spacetime geometry itself is a coherent phase of the chronon ensemble, the field cannot sustain arbitrarily large curvature or compression: the nonlinear stabilization term that enforces the Lorentzian unit constraint

acts as a geometric pressure resisting further collapse.

The quartic potential in the chronon Hamiltonian,

introduces a repulsive term proportional to

that stabilizes finite-size solitons [23]. When gravitational energy density drives the field toward excessive curvature, this quartic term saturates and halts further contraction at a radius

identical in form to the equilibrium soliton scale derived in

Appendix A. The resulting configuration is an incompressible, Planck-scale core—a chronon condensate—whose maximal curvature corresponds to one unit of symplectic flux,

Beyond this saturation threshold, any further collapse would violate the fixed curvature modulus ℏ that defines the quantum phase of the field [59,60]. The black hole interior therefore stabilizes as a compact, coherent domain of the chronon field rather than a singular point. The event horizon marks the region where causal-phase coherence becomes globally inaccessible to external observers, but no physical singularity or information loss occurs.

This reinterpretation unifies gravitational collapse with the symplectic dynamics of quantization. Black holes appear as macroscopic solitons of the chronon manifold—finite, self-consistent regions of maximal curvature and minimal action—whose cores encode the same invariant modulus ℏ that governs all quantum processes. In this view, the conventional singularity is replaced by a geometric core of saturated causal order, providing a natural resolution of the curvature blow-up and information paradoxes within a single microscopic framework.

8.5. Curvature Instantons and Quantum Tunneling in Chronon Field Theory

In Chronon Field Theory (CFT), quantum tunneling arises naturally from the geometry of the chronon manifold rather than from an externally imposed uncertainty principle. The process corresponds to a finite reconfiguration of the chronon curvature two–form

, connecting neighboring topological sectors with different symplectic flux quanta. In the conventional picture, tunneling between classically separated vacua proceeds through Euclidean configurations (instantons) whose amplitude is suppressed by

. In the chronon formulation, the suppression factor instead involves the geometric action unit

:

where

denotes the excess curvature required to unwind and rewind one unit of chronon flux between adjacent topological sectors

and

.

Physically, the tunneling instanton represents a localized region in which the chronon curvature momentarily departs from its stabilized value, producing a “bubble” of reduced symplectic alignment. In this region the determinant of the induced symplectic metric

transiently vanishes, allowing the field to slip between curvature sectors. The corresponding Euclidean field equation,

admits finite–action instanton solutions that interpolate between vacua of distinct winding number.

The magnitude of tunneling suppression depends on the ratio . In the early, pre–geometric epoch—when curvature fluctuations were large and had not yet stabilized—instantons could percolate freely, leading to rapid transitions between causal microdomains. During curvature condensation, as the chronon field aligned and the curvature modulus became fixed, the tunneling rate diminished exponentially. Once the field reached the ordered quantum phase, curvature instantons became energetically costly and topological sectors were effectively frozen.

Today, with stabilized and the chronon field globally aligned, tunneling between topological sectors is extraordinarily suppressed, analogous to defect freezing in condensed–matter systems following a symmetry–breaking transition. Residual instanton activity may persist only through rare, localized curvature fluctuations, potentially contributing to small vacuum polarization effects or trans–Planckian corrections [43,102].

In summary, quantum tunneling in CFT is a manifestation of curvature dynamics: transitions between distinct symplectic flux sectors proceed via finite–action curvature instantons, with amplitudes governed by the same invariant that controls ordinary quantum processes. Once curvature coherence is established, these processes become exponentially suppressed, ensuring the stability of matter and causal structure in the present cosmic epoch.

8.6. Reinterpretation of Blackbody Radiation and the Rayleigh–Jeans Limit

In classical electrodynamics, the Rayleigh–Jeans law predicts an unbounded increase in radiative energy density at high frequencies,

leading to the so-called ultraviolet catastrophe [80]. Planck famously resolved this divergence by introducing discrete energy quanta

and postulating a universal constant of action

ℏ [74]. Within Chronon Field Theory (CFT), this classical breakdown and its quantum resolution admit a deeper geometric explanation.

In CFT, the electromagnetic field is not a fundamental continuum but a collective excitation of the underlying chronon manifold—a coherent phase wave of the causal field [59,60]. The chronon ensemble possesses a finite correlation length

and a nonzero symplectic curvature modulus

ℏ, which together bound the density of accessible phase-space modes. Fluctuations with wavelengths shorter than

are geometrically suppressed, yielding an effective spectral cutoff frequency

and a modified high-frequency density of states

This exponential attenuation replaces the unphysical divergence of the Rayleigh–Jeans law with a smooth geometric saturation determined by the finite curvature of causal phase space.

Once the chronon field condenses into its coherent (quantum) phase, energy exchange between solitons and collective phase waves occurs only in discrete packets of symplectic flux, each equal to

. The emergent spectral distribution therefore assumes the Planck form,

without any

a priori quantization postulate. Quantization appears dynamically as a manifestation of the finite symplectic area of the chronon manifold—the same invariant that governs canonical commutation, spin quantization, and Fermi–Bose statistics.

In this geometric interpretation, the ultraviolet catastrophe never arises: the chronon field enforces a minimal unit of causal curvature (the invariant ℏ) and a maximal correlation frequency . The Planck distribution thus emerges as a stable, scale-invariant equilibrium between coherent causal order and stochastic chronon fluctuations—a fundamental consequence of the discrete symplectic structure of spacetime itself.

8.7. Extension to Curved and Dynamical Geometries

In this study, the chronon ensemble was formulated on a flat discrete lattice acting as a regulator for the pre-geometric phase. The next theoretical step is to extend the construction to arbitrary causal complexes that approximate curved or dynamical manifolds [65,82]. Such an extension would enable direct investigation of how spacetime curvature and gravitational dynamics emerge as collective excitations of the same microscopic substrate that produces quantization.

Mathematically, this entails promoting the alignment coupling

J to a spatially dependent field

whose fluctuations encode an effective metric tensor

under coarse-graining. Variational analysis of the chronon free energy with respect to

is expected to yield an emergent Einstein–Hilbert term in the continuum limit,

with curvature sourced by solitonic energy densities [49]. This would unify spacetime geometry, matter, and quantization as ordered phases of a single microscopic medium.

8.8. Connection to Holography and Emergent Spacetime

The chronon phase transition admits a natural holographic interpretation. At the Planck boundary, where local coherence first forms, the chronon ensemble defines a

holographic screen separating the pre-geometric interior from the emergent spacetime exterior. The information content on this screen scales with its area, consistent with holographic entropy bounds [4,92,93],

Each chronon thus acts as an elementary carrier of causal information, and

ℏ quantifies the minimal action—and therefore minimal information flux—transmitted across the screen. The chronon field thereby provides a microscopic origin for the holographic principle, linking quantization, information, and causal geometry through a single invariant structure.

8.9. Universality of ℏ and Relation to Entropy

An outstanding question concerns the universality of ℏ: is it a fixed modulus of the chronon microdynamics or a contingent property of specific phases? Scaling arguments suggest that ℏ depends only on the ratio of the stiffness and pinning parameters, , implying universality across all stable chronon phases [70,98]. In this sense, ℏ is an intrinsic feature of causal order, invariant under cosmological evolution.

Since ℏ simultaneously determines the minimal symplectic area and the minimal information quantum (via the entropy relation ), it forms a natural bridge between thermodynamics and quantum theory [57,64]. Exploring the connection between ℏ, entropy production, and information flow may clarify the origin of the arrow of time and the thermodynamic nature of quantum uncertainty. Combined with the Lorentzian exclusivity theorem of [59], these relationships suggest that causality, quantization, and entropy are geometrically unified aspects of the same temporal order parameter.

8.10. Toward Unification of Matter and Geometry

Chronon solitons behave as localized, quantized packets of curvature, momentum, and phase. If additional internal symmetries emerge through spontaneous symmetry breaking of the chronon order parameter, the Standard Model particle multiplets could appear as distinct topological sectors of the same field [66,107]. Gauge interactions would then arise from collective phase connections between solitons, while gravitational curvature would correspond to long-wavelength modulations of background connectivity.

From this perspective, all fundamental interactions—including quantum mechanics itself—become complementary manifestations of the same discrete pre-geometric substrate. The chronon condensate defines spacetime, matter, and quantization as coherent, causally ordered phases of a single microscopic system.

8.11. Summary and Long-Term Vision

The chronon framework reframes the central question of physics: not why nature is quantized, but how quantization, spin, and causality emerge dynamically. In this unified picture:

ℏ is a curvature invariant of the Planck transition, not a postulate.

Quantum mechanics is the hydrodynamic limit of coherent chronon excitations.

Gravity and spacetime curvature arise from variations in chronon connectivity.

Fermi–Bose statistics reflect topological coverings of the same symplectic manifold.

Classical determinism corresponds to complete phase alignment (macroscopic decoherence).

Future efforts will focus on: (i) extending chronon lattice models to curved and expanding manifolds; (ii) deriving effective Einstein–Yang–Mills equations from chronon condensation; (iii) quantifying the information–action correspondence mediated by ℏ; and (iv) exploring potential laboratory analogues in condensed-matter and quantum-simulation systems [16].

Together with the Lorentzian results of [59], these developments outline a coherent program: causal structure, quantum commutation, spin quantization, and statistics all originate from the same symplectic and topological properties of the chronon field. The long-term goal is to establish a unified microscopic theory from which both quantum mechanics and general relativity emerge as stable, ordered phases of a single pre-geometric medium—the chronon field.