1. Introduction

Almond production (

Prunus dulcis [Mill.] D.A. Webb) has experienced remarkable global growth in recent years, driven by both agronomic and economic factors. Over the past 15 years, the global context has remained favourable for almond cultivation [

1]. The rising demand is largely attributed to the well-documented health benefits associated with almond consumption. Almonds are rich in vitamin E, protein, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, magnesium, potassium, and dietary fiber — nutrients linked to a reduced risk of cardiometabolic disorders [

2]. In addition, expanding markets in Asia and other regions have further stimulated demand and elevated market prices [

3].

As a consequence of these global trends, almond production systems are undergoing a fundamental transformation in the Mediterranean region. Once considered a marginal, rain-fed crop, almond is now cultivated under intensified and profitable systems, incorporating new varieties and improved management practices aimed at enhancing yield and profitability [

4].

In France, although almond cultivation remains limited in extent, farmers’ interest is increasing, particularly in southern regions traditionally devoted to cereals, lavender, vegetables, and viticulture. As of 2023, France’s almond acreage has reached 2,330 hectares [

5] — an infinitesimal share compared to the total almond-growing area in Europe, which spans approximately 915,561 hectares [

5]. Nonetheless, the growing investment in almond orchards in southern France signals an important shift in agricultural priorities and potential for future expansion.

Globally, almond diseases have been extensively investigated [

6,

9,

6,

9]. Major diseases include red leaf blotch (

Polystigma amygdalinum P.F. Cannon), shot hole (

Wilsonomyces carpophilus [Lév.] Adask., J.M. Ogawa & E.E. Butler), brown rot and blossom blight (

Monilinia spp.), and leaf curl (

Taphrina deformans [Berk.] Tul.) [

10,

11]. Furthermore, an expansion of long-established diseases such as anthracnose (

Colletotrichum acutatum J.H. Simmonds) [

12] and the emergence of new trunk and branch canker pathogens [

9,

13,

14] have been reported.

Among these, particular attention in recent decades has focused on fungal canker pathogens, owing to their capacity to substantially reduce orchard longevity and productivity [

13,

14,

15,

16]. The disease caused by

Diaporthe amygdali is characterized by the rapid desiccation of shoots, flowers, and leaves following infections that typically occur between late winter and early spring [

17,

18,

19,

20]. Infected buds develop sunken, reddish-brown necrotic lesions that evolve into cankers exuding small quantities of gum [

21]. As lesions expand, they girdle twigs, causing distal shoot dieback and general canopy wilting. The fungus overwinters in the bark of the cankers [

17].

Although

D. amygdali primarily infects members of the genus

Prunus — including almond, peach, and nectarine — its pathogenicity has been widely documented worldwide [

3,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. The pathogen has also been reported from several unrelated hosts, such as grapevine in South Africa [

32],

Pieris japonica in the United States [

33], Asian pear and walnut in China [

34], and blueberry in Portugal [

35], demonstrating its polyphagous nature.

Lalancette and co-authors [

36,

37] elucidated key aspects of disease development on peach plantations in New Jersey, showing that

D. amygdali primarily penetrates through wounds formed during leaf abscission in autumn or shoot emergence and flower/fruit drop in spring. Infections can also arise directly through young shoots [

38]. The incubation period from infection to visible canker development is approximately one month.

Climatic conditions strongly influence disease expression: in mild autumns and winters, cankers develop rapidly, leading to shoot dieback in early spring; conversely, cold winters delay symptom expression, resulting in shoot death during the following summer. Under favorable conditions,

D. amygdali produces pycnidia within the cankers, releasing α-conidia — the predominant form found on almond — and occasionally β-conidia [

19,

38].

The formation and release of conidia, often extruded as cirri, are regulated by environmental parameters, particularly temperature and relative humidity [

37,

39]. Fungal development is slow at 5 °C but accelerates above 10 °C [

21]; growth occurs across a broad temperature range (0–37 °C), with optimal growth around 19–20 °C. Maximum conidial production occurs between 22 °C and 23 °C under a relative humidity above 95% sustained for at least 16 hours [

37]. These environmental conditions are critical to disease epidemiology, as they not only promote conidial growth and dispersal but also delay the natural healing of wounds caused by leaf abscission.

Rain events further facilitate pathogen dissemination, as conidia are dispersed by water splash to adjacent tissues and trees, where they germinate on moist surfaces at temperatures between 5 °C and 36 °C [

21,

39].

Over the past decade, research on the vulnerability of almond cultivars to fungal diseases has increased substantially compared with earlier years. In one of the first systematic studies conducted in Spain, Egea

et al. [

40] evaluated the susceptibility of 81 almond varieties to red leaf blotch. In California, Gradziel and Wang [

41] investigated the susceptibility of several cultivars to

Aspergillus flavus Link, while Diéguez-Uribeondo

et al. [

42] assessed the response of four cultivars to

Colletotrichum acutatum. In Australia, field evaluations of 34 almond cultivars determined their susceptibility to

Tranzschelia discolor, the causal agent of rust, under both natural and artificial inoculation conditions [

43]. More recently, López-Moral

et al. [

12] examined 19 Spanish cultivars for their sensitivity to

C. acutatum and

C. axcutiae Neerg., and subsequent studies have evaluated the response of early- and late-flowering cultivars to leaf pathogens such as

Monilinia laxa,

Polystigma amygdalinum,

Taphrina deformans, and

Wilsonomyces carpophilus [

10,

11].

Specific studies on the susceptibility of almond cultivars to

Diaporthe amygdali have also been conducted in several countries. In Chile, Besoain

et al. [

24] found that cultivars ‘Nonpareil’ and ‘Price’ were more susceptible than ‘Carmel’ under artificial inoculation. In Portugal, the local cultivar ‘Barrinho Grado’ showed greater tolerance than ‘Ferragnès’ [

25]. In Spain, Vargas and Miarnau [

44] evaluated more than 70 cultivars and 36 breeding selections under natural field conditions, revealing a high overall susceptibility to

Diaporthe dieback. In Hungary, Varjas

et al. [

20] assessed 162 almond genotypes over four consecutive years, identifying 31 cultivars with very high levels of tolerance. In particular, ‘Budatétényi-70’ and ‘Tétényi keményhéjú’ were significantly more tolerant than the other Hungarian genotypes, suggesting considerable genetic variability in disease resistance.

The objectives of the present study were to: (i) isolate and characterize fungal strains from naturally infected almond samples collected in France, using morphological characterization and multilocus phylogenetic analyses based on the ITS, tef1-α, act, his3, tub2, and cal gene regions; (ii) determine the susceptibility of 18 almond genotypes—both French and Italian—using ‘Ferragnès’ and ‘Texas’ as susceptible and tolerant controls, respectively; and (iii) compare three field inoculation methods.

This study differs from previous investigations in that it aimed to evaluate the performance of different almond genotypes against multiple pathogen isolates under field conditions closely resembling natural infection. The experimental design incorporated both commercial cultivars already reported in the literature and hybrid selections developed at the INRAE Research Centre.

3. Discussion

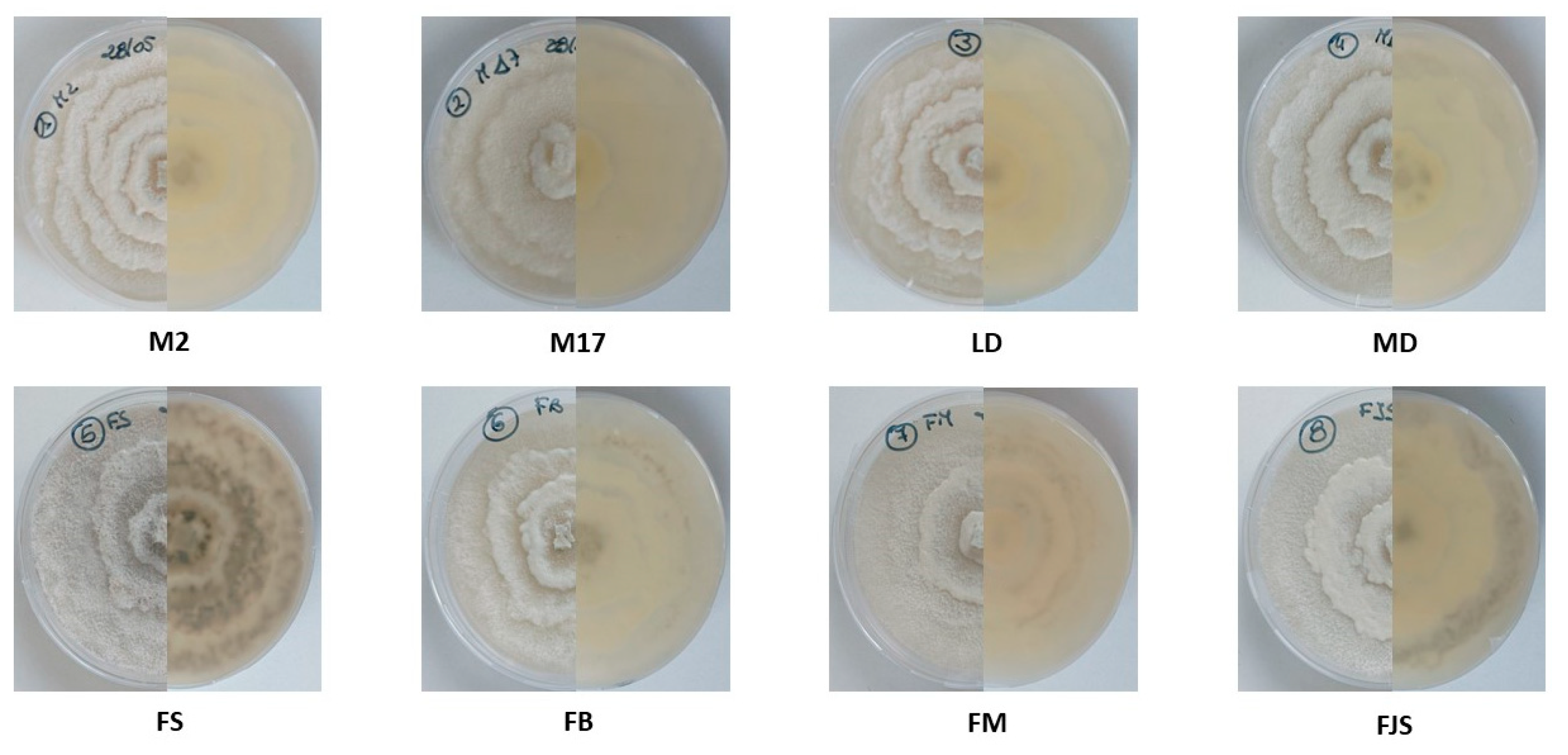

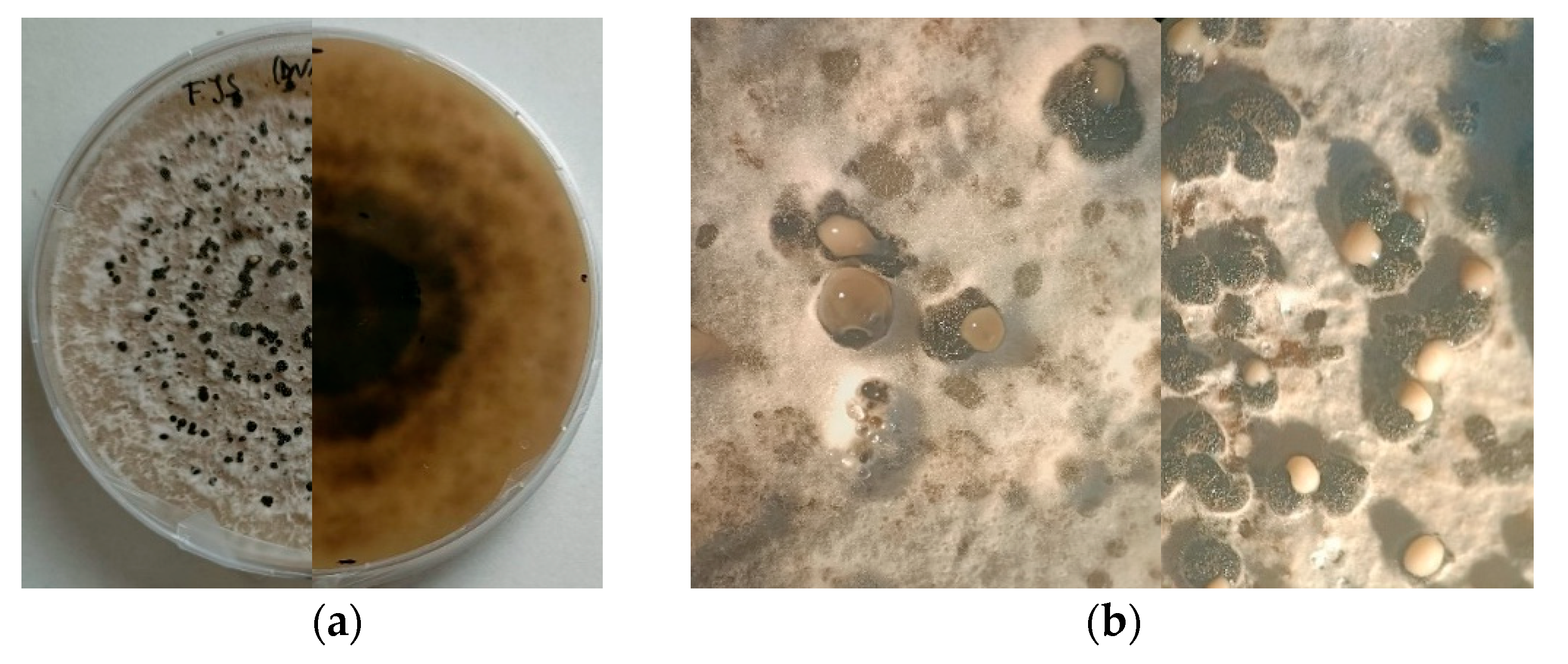

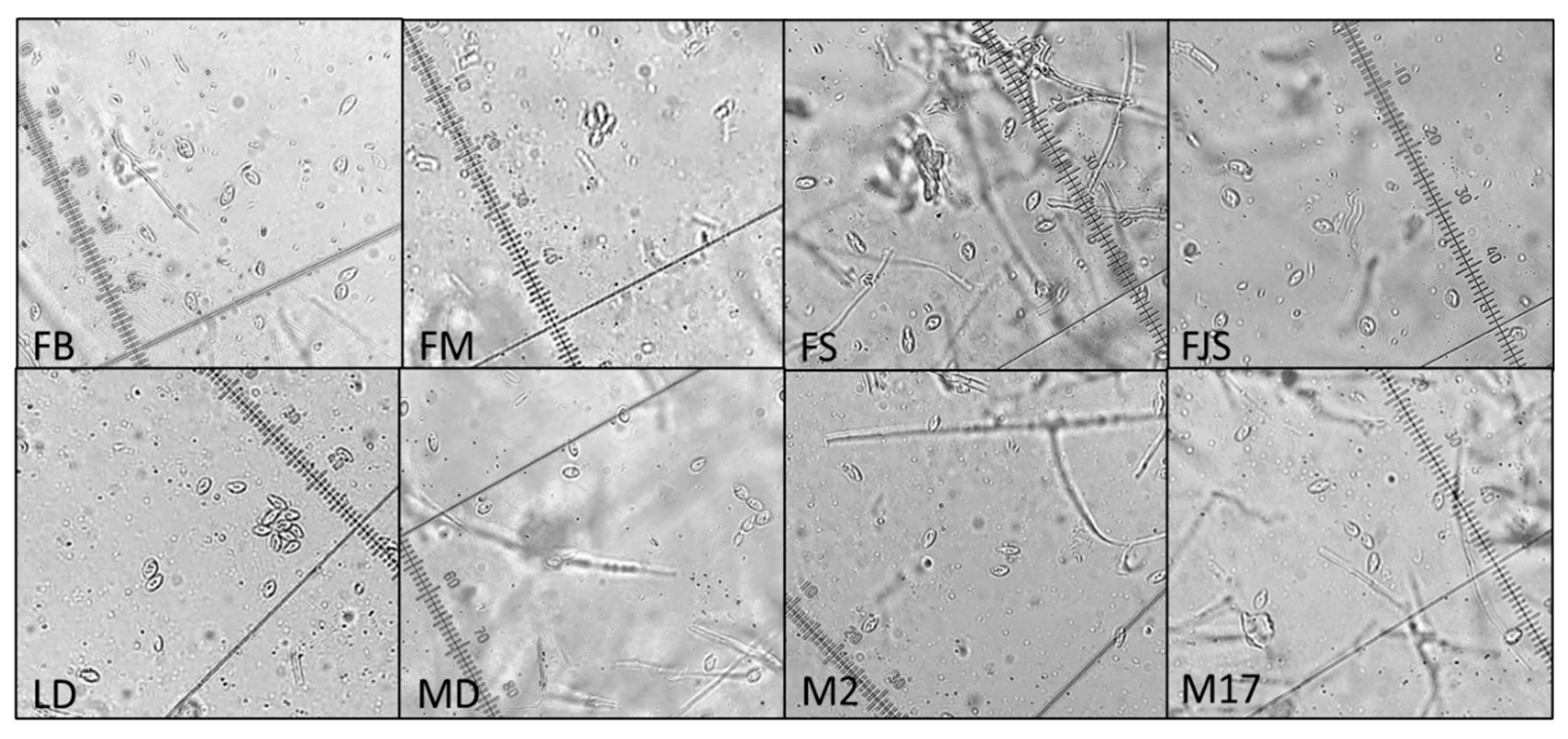

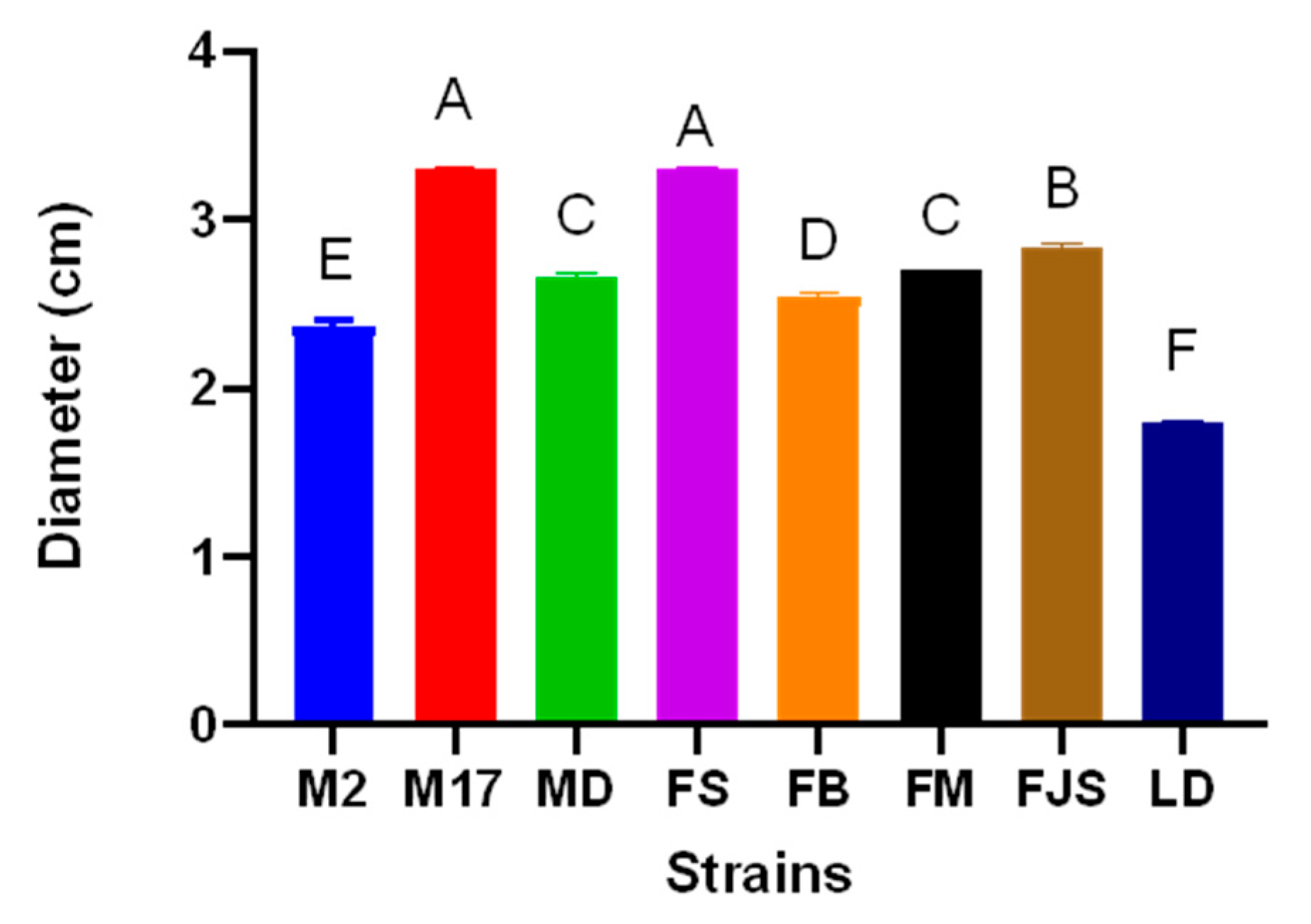

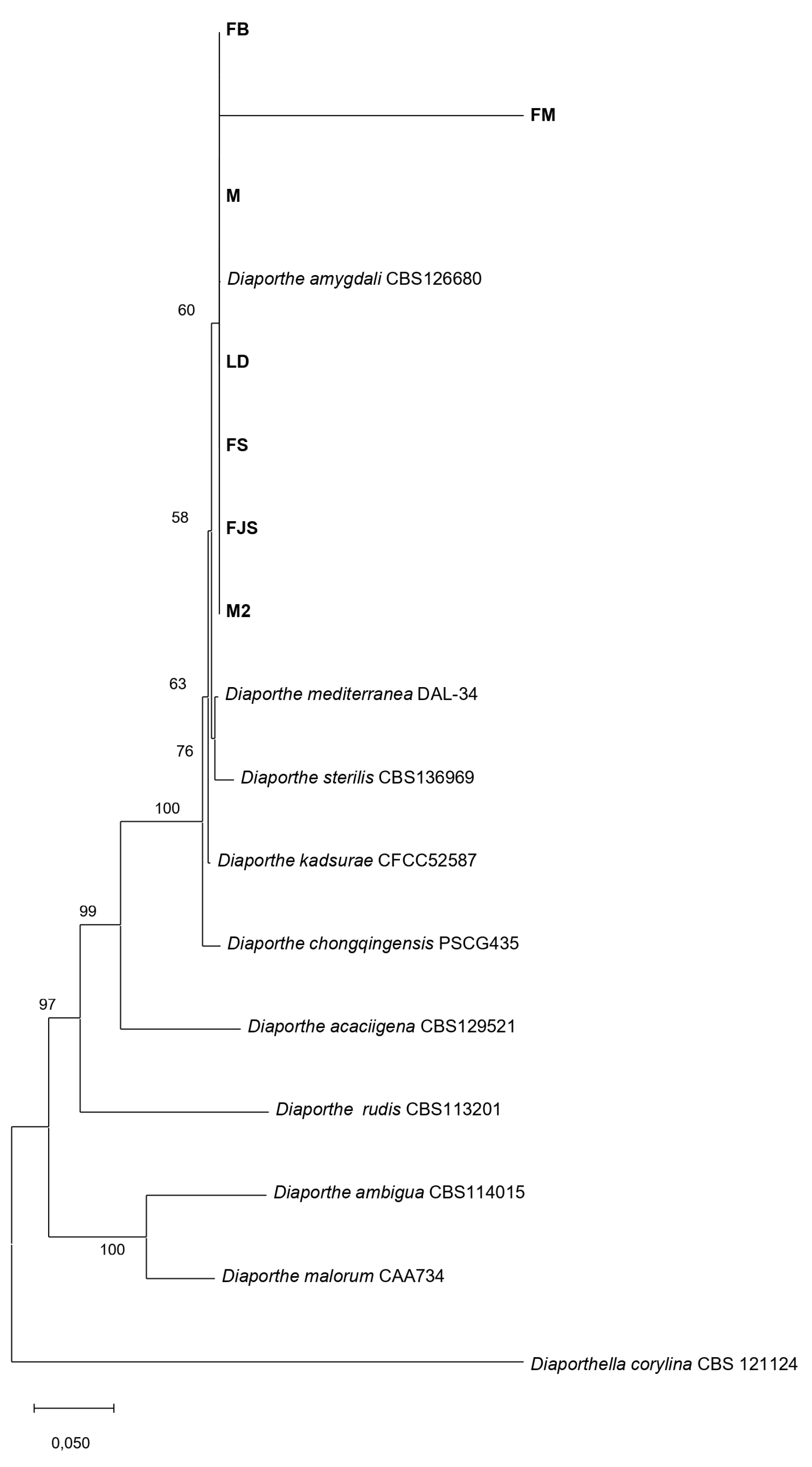

The morphological and molecular characterization of isolates obtained from naturally infected almond samples collected across various orchards in southern France confirmed the exclusive presence of Diaporthe amygdali on almond trees. Morphological observations revealed that one isolate (LD) exhibited noticeably slower growth than the other isolates, accompanied by reduced pycnidia production on PDA at 25 °C under a 12 h UV-light photoperiod. In contrast, isolates FJS and M17 showed markedly higher growth rates and abundant pycnidia formation.

Regarding conidial morphology, only α-type conidia were observed, with no detectable variation among isolates, consistent with previous reports [

45,

46,

47]. These morphological findings, together with multilocus sequence data (ITS,

tef1-α, cal, his3, and

tub2), confirmed the identity of all isolates as

D. amygdali, in full agreement with the results of Gusella et al. (2023) [

45], who also found that almond-derived isolates clustered closely with reference strains of this species.

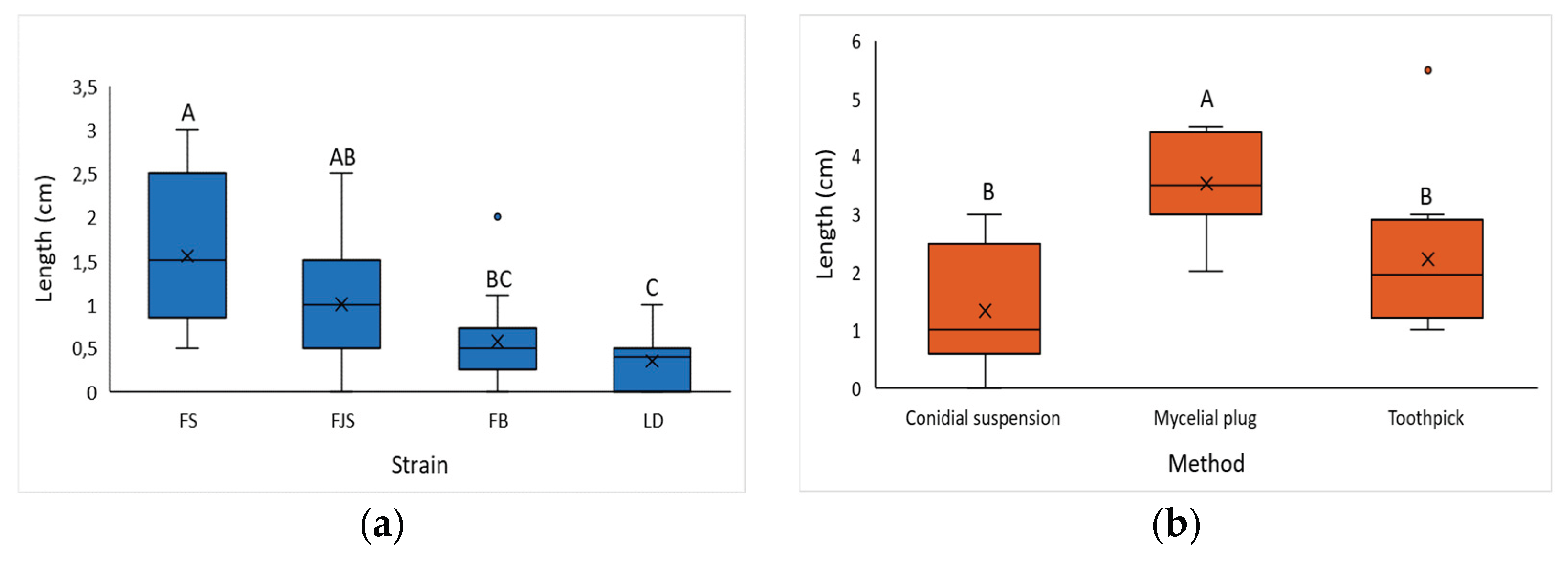

With respect to inoculation techniques, the mycelial plug method proved to be the most effective, as it produced rapid symptom development and facilitated detection. This observation aligns with previous studies reporting similar outcomes [

3,

18,

28,

45]. The toothpick inoculation method, in which the toothpick is colonized by fungal mycelium, was moderately effective, whereas the conidial suspension technique, although simpler to perform, was the least efficient. In the latter case, lesion size could be affected by the dimensions of the incision, and symptom expression was delayed (approximately 60 days post-inoculation).

Comparative analyses of

D. amygdali isolates revealed significant differences in pathogenicity. The LD isolate produced statistically smaller lesions than the FS isolate (

Figure 9a), consistent with its slower growth and lower pycnidia and conidia production in vitro. Conversely, isolate FS was characterized as the most aggressive, producing the largest lesions and exhibiting the fastest mycelial growth on PDA, followed closely by M17.

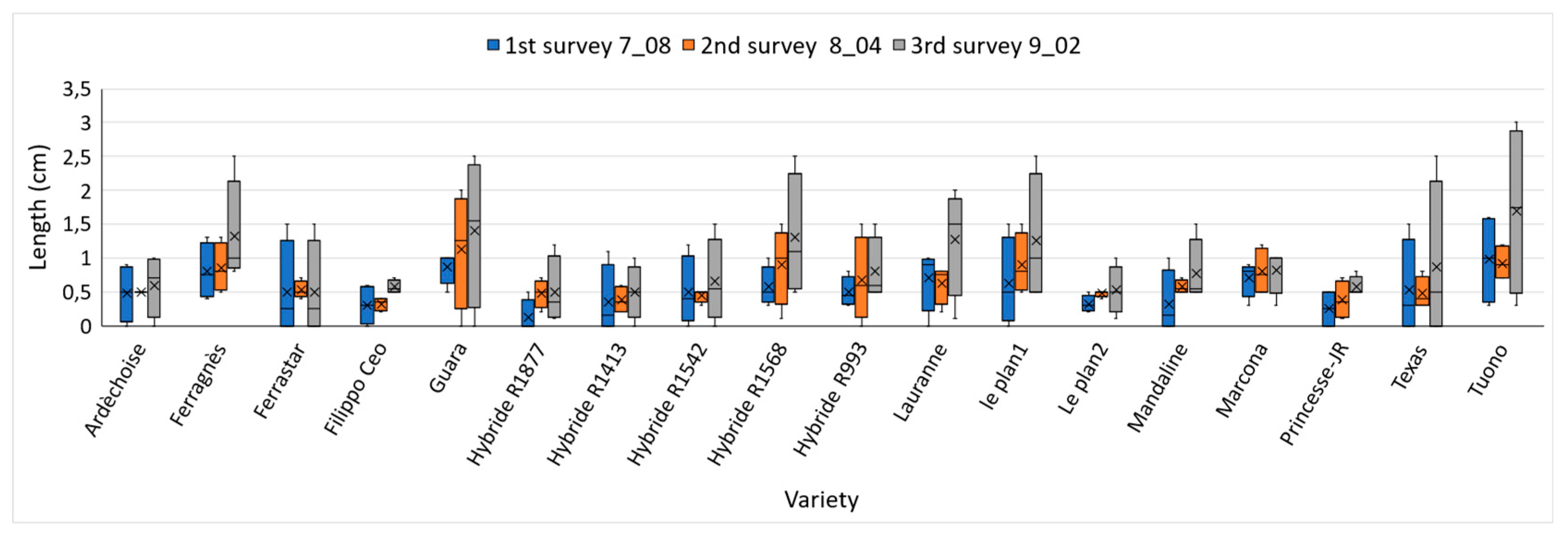

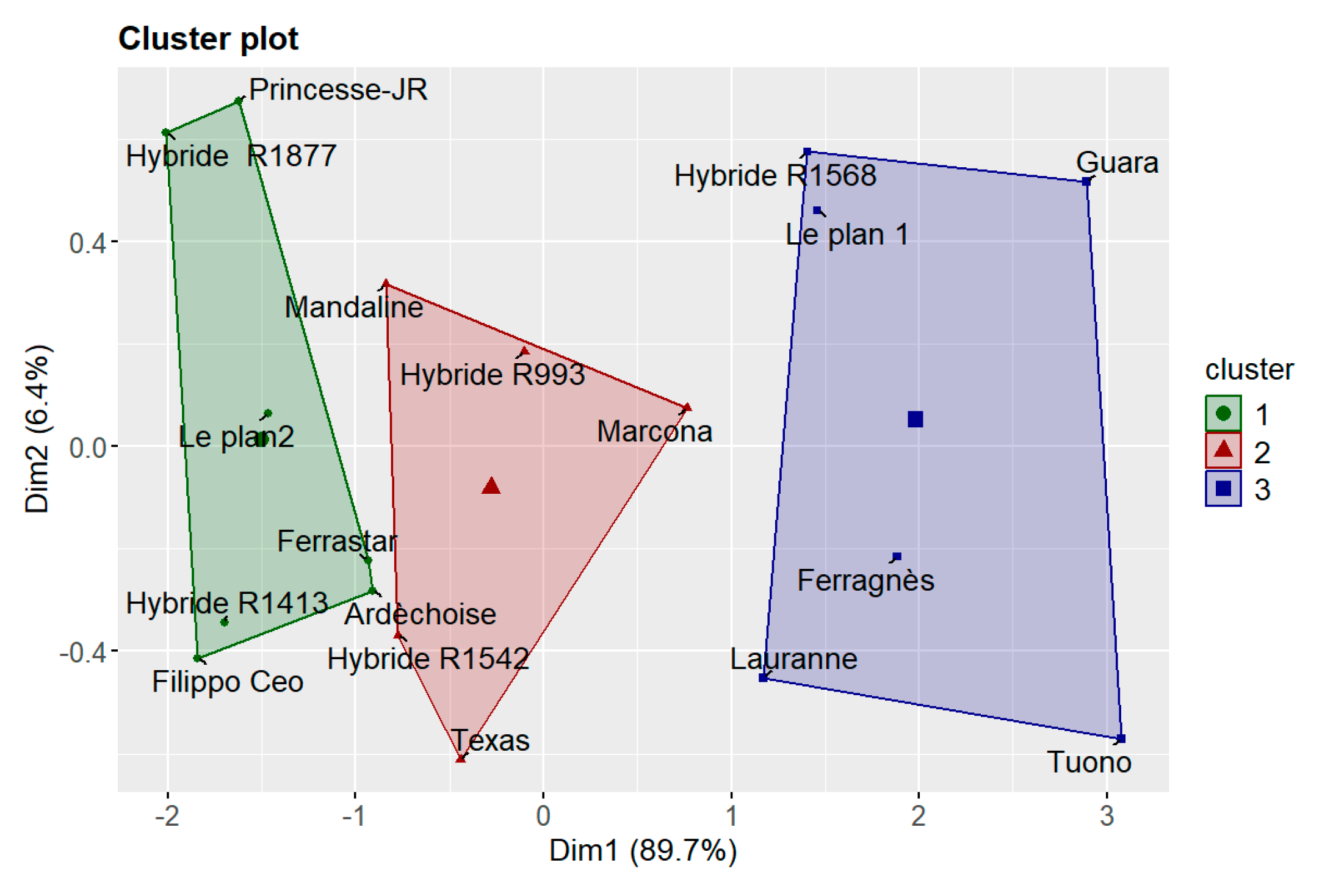

Regarding cultivar susceptibility, all tested varieties developed cankers at the inoculation point, although lesion length varied. While these differences were not statistically significant, symptom onset occurred earlier in some cultivars, whereas others maintained smaller, more stable cankers, indicating greater tolerance to the pathogen. This pattern is illustrated in Figure 12: varieties belonging to Cluster 1 (green)— ‘Ardèchoise’, ‘Ferrastar’, ‘Hybride R1877’, ‘Filippo Ceo’, ‘Hybride R1413’, ‘Le Plan 2’, and ‘Princesse-JR’—displayed smaller, stable lesions throughout the experiment. The result for ‘Filippo Ceo’ is consistent with the findings of Catalano et al. (2025) [

48], who also reported this cultivar among those developing the shortest cankers (

Supplementary Table).

Cluster 2 included ‘Hybride R1542’, ‘Hybride R993’, ‘Mandaline’, ‘Marcona’, and ‘Texas’, which showed intermediate lesion lengths that remained stable over time. The performance of ‘Texas’ corroborates the results of Catalano et al. (2025) [

48], while ‘Marcona’ showed an intermediate susceptibility pattern similar to that described by Beluzán et al. (2022) [

3]. Cluster 3 comprised ‘Ferragnès’, ‘Guara’, ‘Hybride R1568’, ‘Lauranne’, ‘Le Plan 1’, and ‘Tuono’, which developed longer and more rapidly expanding cankers, indicating higher susceptibility.

Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the responses of different almond cultivars to D. amygdali, a pathogen that has re-emerged in recent years and poses a growing threat to almond production in the Mediterranean region. The identification of potentially tolerant cultivars under Mediterranean conditions—corroborating findings from southern Italy and Spain—highlights the importance of these genotypes as potential sources of resistance in future breeding and selection programs. Although inoculation with conidial suspensions proved less effective in symptom onset, this method most closely mimics natural infection processes in the field. Therefore, it remains a valuable approach for assessing cultivar responses under conditions approximating natural pathogen–host interactions.

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Isolation, Morphological and Molecular Characterization

Branches showing symptoms indicative of Diaporthe amygdali infection—such as shoot blight, cankers, and gum exudation—were collected from almond orchards located in the Provence region of southern France during April and May. Samples were taken from various positions within the canopy, focusing on areas where symptoms were most evident. Each specimen was placed in a humid chamber and incubated at ambient temperature for approximately two weeks to promote the development of cirri. Once cirrus formation was observed, exudates were aseptically collected using a sterile needle loop and transferred onto Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA, Difco) supplemented with 0.5 g/L streptomycin sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit bacterial growth. Plates were incubated at 25 °C for up to two weeks and monitored regularly for fungal development and possible contamination.

Fungal colonies exhibiting morphological characteristics consistent with Diaporthe spp. were subcultured onto fresh PDA plates to obtain pure cultures. Single-spore isolation was performed by transferring individual conidia onto new PDA plates under a stereomicroscope in sterile conditions. The purified isolates were incubated at 25 °C in the dark for 7–10 days and subsequently stored at 4 °C for further morphological and molecular analyses.

Following purification, the isolates were subjected to detailed morphological characterization. To stimulate sporulation and allow examination and measurement of reproductive structures, each isolate was cultured on PDA and incubated at 25 °C under a 12 h light/dark photoperiod with UV illumination for 15 days. Conidial measurements were conducted by mounting spores in sterile water on microscope slides after growth on PDA. Observations and measurements were performed using an Olympus BH2 BHS-312 trinocular microscope at 40× magnification. Colony growth was assessed by measuring the radial expansion of the mycelium on PDA after 4 and 10 days of incubation. For accuracy and reproducibility, all measurements were performed in triplicate for each isolate.

A total of eight isolates were used for molecular characterization, including six isolates obtained in this study and two reference isolates from Spain. Genomic DNA was extracted according to the protocol described by Mishra et al. (2008). PCR amplification of seven conserved genomic regions was carried out using primer sets (

Table S2).

Each 50 µL PCR reaction contained 10 µL of 5× Green GoTaq® Flexi Buffer, 3 µL of 25 mM MgCl₂, 0.4 µL of GoTaq® DNA Polymerase (Promega), 1 µL of each primer at 20 µM (except for the his3 primers, for which 0.5 µL of each was used), and 4 µL of genomic DNA at dilutions ranging from 1:800 to 1:20. The final reaction volume was adjusted with nuclease-free water.

PCR amplifications were performed in an Eppendorf 5341 Mastercycler epGradient thermal cycler under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min; followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s at primer-specific temperatures (55 °C for ITS1-4 and tef1-α, 58 °C for cal, 50 °C for BtCadF–BtCadR, and 59 °C for his3), and extension at 72 °C for 40 s; with a final extension at 72 °C for 10 min.

Amplified products (10 µL) were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% (w/v) agarose gels and visualized under UV illumination.

Raw sequence data for each isolate were analyzed using CLC Main Workbench v8 (QIAGEN). Sequence quality was assessed, and consensus sequences were generated by assembling forward and reverse reads. Taxonomic identification of isolates was performed through nucleotide BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) comparisons against the NCBI GenBank database.

Subsequent analyses were conducted using MEGA v12 [

54]. Multiple sequence alignments for each gene region were generated with the CLUSTAL algorithm [

55], incorporating both newly obtained sequences and relevant reference sequences retrieved from GenBank (

Table S3). For multi-locus phylogenetic analysis, the aligned sequences were concatenated into a single dataset. Phylogenetic inference was carried out using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method based on the Tamura–Nei model of nucleotide substitution [

56]. The tree with the highest log-likelihood value (–5033.69) is presented.

Branch support was assessed through bootstrap analysis with 1,000 replicates [

57], and the resulting bootstrap values are shown at the corresponding nodes. The initial tree for the heuristic search was selected by comparing the log-likelihood scores of a Neighbor-Joining (NJ) tree [

58] and a Maximum Parsimony (MP) tree. The NJ tree was generated from a pairwise distance matrix computed using the Tamura–Nei model, whereas the MP tree represented the shortest topology among 10 replicates, each initiated from a randomly generated starting tree.

Variation in evolutionary rates among sites was modelled using a discrete Gamma distribution with eight categories (+G) and a shape parameter of 0.3287. The analysis included 14 nucleotide sequences, and positions with less than 95% site coverage were excluded using the partial deletion option, resulting in a final alignment of 1,487 positions. All evolutionary analyses were performed in MEGA12, employing up to six parallel computing threads to optimize computational efficiency.

4.2. Plant Materials and Experimental Sites and Plot Design

This study was conducted on 18 almond cultivars (

Table 2), all grown under uniform agronomic and environmental conditions in the experimental orchard of INRAE, Domaine des Garrigues (9004 Allée des Chênes, Avignon, France). The trees were planted in 2012 at a spacing of 5 × 2 m, with one replicate tree per cultivar. No fungicide treatments were applied throughout the study period, allowing for natural disease development and controlled inoculation experiments.

Inocula were prepared according to the specific inoculation technique employed. For the conidial suspension technique, fungal isolates were grown on PDA plates at 25 °C under a 12-hour light/dark photoperiod to induce pycnidia development. After 15 days of incubation, mature pycnidia were scraped from the agar surface with a sterile loop and transferred into sterile beakers containing distilled water. The conidia were released using a handheld electric homogenizer, and the resulting suspension was filtered through a 0.45 µm membrane filter (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove mycelial debris. Serial dilutions were then performed to obtain a final concentration of approximately 1 × 10⁵ conidia mL⁻¹.

For the mycelial plug technique, isolates were cultured on PDA plates in complete darkness at 25 °C for 7 days to promote vegetative mycelial growth while preventing sporulation. Agar plugs (0.5 cm in diameter) were excised from the actively growing colony margins and used for inoculation.

For the toothpick technique, sterile wooden toothpicks (≈ 2 cm long) were inserted into PDA plates previously inoculated with the respective fungal isolates and incubated in darkness at 25 °C for 10 days to allow complete colonization by the mycelium.

Three inoculation methods were applied in this study: conidial suspension, mycelial plug, and colonized toothpick. All 18 almond cultivars were inoculated using the FS isolate via the conidial suspension method. The suspension (1 × 10⁵ conidia mL⁻¹) was applied as a single drop onto a superficial wound on the shoot surface, which was then sealed with Parafilm to maintain humidity.

The mycelial plug inoculation method, using the FS isolate, was applied to five cultivars: Ferragnès, Ferrastar, Ardèchoise, Tuono, and Texas. PDA plugs (0.5 cm diameter) from 7-day-old cultures were inserted into shallow wounds on the shoots and immediately wrapped with Parafilm to prevent desiccation.

The same five cultivars were used for the toothpick inoculation method with isolates FS and FM. Sterilized, pre-colonized toothpicks (~2 cm long) were inserted into 0.5 cm-deep holes made in the shoot tissue. The inoculation sites were sealed with paraffin wax to protect the entry point and retain moisture.

For each cultivar and inoculation method, three biological replicates were performed. The trial began on 3 June 2025, and symptom development was monitored monthly thereafter.

4.3. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using JMP® Pro software (version 18; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 1989–2023). Prior to performing one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey–Kramer’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) post hoc test, data distributions were assessed for normality. Statistical differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05 or p ≤ 0.01.

Disease symptom data were further analyzed using R software (version 2024.12.1). To determine the optimal number of clusters, the NbClust package was employed, which evaluates multiple clustering criteria simultaneously. Based on this evaluation, k-means clustering was performed with the number of clusters (k = 3) as determined by NbClust. The algorithm was executed with the parameter nstart = 25, which runs 25 iterations with different centroid initializations to minimize suboptimal convergence. To ensure reproducibility, a fixed random seed was set (set.seed(123)).

Cluster visualization was performed using the factoextra package and the fviz_cluster function, which displays the clusters and their centroids in the plane defined by the first two principal components derived from Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

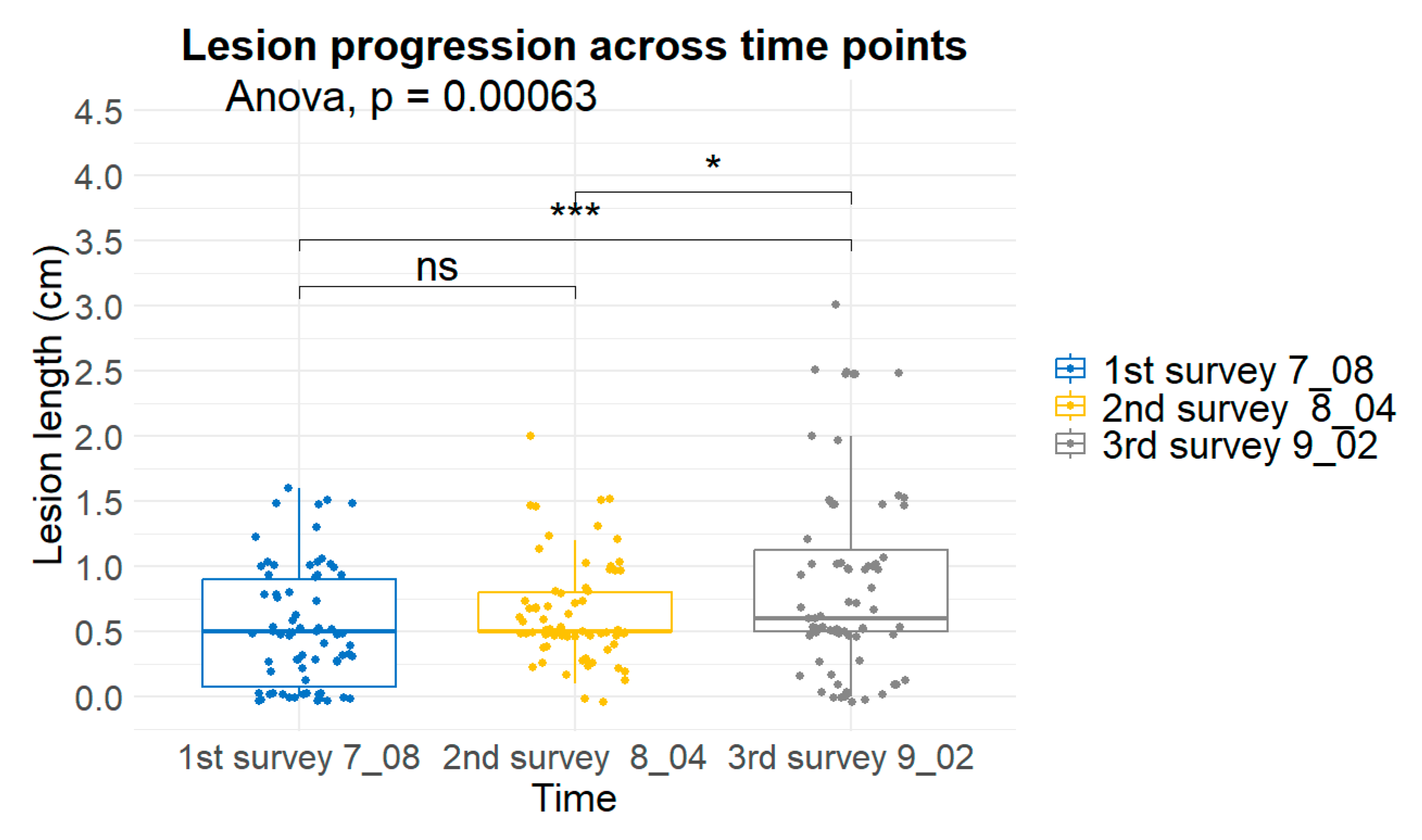

To evaluate the temporal progression of disease symptoms, boxplots were generated using the ggpubr package in the R environment. Lesion length data (cm), collected at three time points (8 July, 4 August, and 2 September), were converted into long format using the pivot_longer function from the tidyr package. The ggboxplot function was then applied to visualize lesion length as the dependent variable. A global ANOVA was used to assess statistical differences among the three time points (stat_compare_means(method = "anova")), followed by pairwise comparisons using Student’s t-test (stat_compare_means(method = "t.test")).

Figure 1.

Colony diameter of Diaporthe amygdali isolates after 4 days of incubation at 25 ± 1 °C. Statistically significant differences among isolates are indicated by different letters according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.001). Data represent mean ± standard error (n = 3).

Figure 1.

Colony diameter of Diaporthe amygdali isolates after 4 days of incubation at 25 ± 1 °C. Statistically significant differences among isolates are indicated by different letters according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.001). Data represent mean ± standard error (n = 3).

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships among Diaporthe species and D. amygdali isolates collected from different regions of southern France, based on concatenated sequences of five loci (ITS, tef1-α, cal, his3, and tub2). The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method under the Tamura–Nei substitution model, with a scale bar representing 0.050 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships among Diaporthe species and D. amygdali isolates collected from different regions of southern France, based on concatenated sequences of five loci (ITS, tef1-α, cal, his3, and tub2). The tree was constructed using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method under the Tamura–Nei substitution model, with a scale bar representing 0.050 nucleotide substitutions per site.

Figure 6.

(a) Lesion length (cm) induced by different Diaporthe amygdali isolates using the conidial suspension method, 90 days after inoculation; (b) Lesion length (cm) induced by different inoculation methods, 90 days after inoculation. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.0001).

Figure 6.

(a) Lesion length (cm) induced by different Diaporthe amygdali isolates using the conidial suspension method, 90 days after inoculation; (b) Lesion length (cm) induced by different inoculation methods, 90 days after inoculation. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences according to Tukey’s test (p < 0.0001).

Figure 7.

Lesions caused by Diaporthe amygdali using three different inoculation methods. (a) Negative control inoculated with sterile distilled water; (b) lesions observed in Septemberfollowing inoculation with a conidial suspension; (c) negative control inoculated with a sterile PDA plug; (d) lesions observed inSeptember following inoculation with a mycelial plug; (e) negative control inoculated with a sterile toothpick; (f) lesions observed in September, respectively, following inoculation with a toothpick colonized by mycelium; (g,h) detail of gummy exudates on cankered shoots.

Figure 7.

Lesions caused by Diaporthe amygdali using three different inoculation methods. (a) Negative control inoculated with sterile distilled water; (b) lesions observed in Septemberfollowing inoculation with a conidial suspension; (c) negative control inoculated with a sterile PDA plug; (d) lesions observed inSeptember following inoculation with a mycelial plug; (e) negative control inoculated with a sterile toothpick; (f) lesions observed in September, respectively, following inoculation with a toothpick colonized by mycelium; (g,h) detail of gummy exudates on cankered shoots.

Figure 8.

Mean lesion length (cm) recorded in three consecutive evaluations: 7 July (blue), 4 August (orange), and 2 September (grey). Data represent the mean ± standard error (SE) for each almond variety at each evaluation date.

Figure 8.

Mean lesion length (cm) recorded in three consecutive evaluations: 7 July (blue), 4 August (orange), and 2 September (grey). Data represent the mean ± standard error (SE) for each almond variety at each evaluation date.

Figure 9.

k-means cluster plot of 18 almond varieties based on lesion length measurements obtained from three disease evaluation surveys. The three clusters represent groups of varieties with different levels of susceptibility: Cluster 1 (green) – tolerant; Cluster 2 (red) – intermediate; and Cluster 3 (blue) – susceptible. Axes (Dim1 and Dim2) correspond to the first two principal components, which together explain approximately 96% of the total variance.

Figure 9.

k-means cluster plot of 18 almond varieties based on lesion length measurements obtained from three disease evaluation surveys. The three clusters represent groups of varieties with different levels of susceptibility: Cluster 1 (green) – tolerant; Cluster 2 (red) – intermediate; and Cluster 3 (blue) – susceptible. Axes (Dim1 and Dim2) correspond to the first two principal components, which together explain approximately 96% of the total variance.

Figure 10.

Progression of lesion length across three evaluation periods (8 July, 4 August, and 2 September). Box plots display the median, interquartile range, and individual data points. One-way ANOVA (p = 0.00063) indicated significant differences among time points, with *** denoting p < 0.001, * denoting p < 0.05, and ns indicating non-significant comparisons.

Figure 10.

Progression of lesion length across three evaluation periods (8 July, 4 August, and 2 September). Box plots display the median, interquartile range, and individual data points. One-way ANOVA (p = 0.00063) indicated significant differences among time points, with *** denoting p < 0.001, * denoting p < 0.05, and ns indicating non-significant comparisons.

Table 1.

Origin and host information for Diaporthe amygdali isolates recovered from infected almond orchards in France, along with two reference strains (M2 and M17) supplied by ANSES, Corsica.

Table 1.

Origin and host information for Diaporthe amygdali isolates recovered from infected almond orchards in France, along with two reference strains (M2 and M17) supplied by ANSES, Corsica.

| ID |

Variety |

Orchard |

Origin |

| M2 |

Unknown |

ref 18-286 |

ANSES, Corsican |

| M17 |

Unknown |

ref 18-286 |

ANSES, Corsican |

| LD |

Lauranne |

Doniat |

Charolles, France |

| MD |

Mandaline |

Doniat |

Charolles, France |

| FS |

Ferragnès |

Silvain |

St Didier, France |

| FB |

Ferragnès |

Blonde |

Manduel, France |

| FM |

Ferragnès |

Morin |

Donzere, France |

| FJS |

Ferragnès |

Jean Silvain |

St Didier, France |

Table 2.

Origin and main characteristics of the 18 almond (Prunus dulcis) cultivars included in the study. Cultivars were grown under uniform conditions at INRAE–Domaine des Garrigues (Avignon, France). Susceptibility levels are based on disease response to Diaporthe amygdali: S = susceptible, T = tolerant, I = intermediate. “X” indicates cultivars selected for testing the respective inoculation method (conidial suspension, mycelial plug, or toothpick).

Table 2.

Origin and main characteristics of the 18 almond (Prunus dulcis) cultivars included in the study. Cultivars were grown under uniform conditions at INRAE–Domaine des Garrigues (Avignon, France). Susceptibility levels are based on disease response to Diaporthe amygdali: S = susceptible, T = tolerant, I = intermediate. “X” indicates cultivars selected for testing the respective inoculation method (conidial suspension, mycelial plug, or toothpick).

| Code No. |

Variety |

Country* |

Early

flowering** |

Susceptibility |

Inoculum method*** |

| A

|

B

|

C

|

| R486 |

Ferragnès |

FRA |

4 |

S |

X |

X |

X |

| R1877 |

Hybride R1877 |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R916 |

Lauranne |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R800 |

Ferrastar |

FRA |

5 |

T |

X |

X |

X |

| R61 |

Ardèchoise |

FRA |

3 |

T |

X |

X |

X |

| R185 |

Marcona |

ESP |

2 |

|

X |

|

|

| R1046 |

Princesse-JR |

FRA |

2 |

|

X |

|

|

| R934 |

Guara |

ITA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R998 |

Mandaline |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R219 |

Tuono |

ITA |

4 |

T |

X |

X |

X |

| R993 |

Hybride R993 |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R1590 |

Le plan1 |

FRA |

4 |

|

X |

|

|

| R1568 |

Hybride R1568 |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R270 |

Texas |

USA |

4 |

T |

X |

X |

X |

| R1413 |

Hybride R1413 |

FRA |

7 |

|

X |

|

|

| R1542 |

Hybride R1542 |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|

| R860 |

Filippo Ceo |

ITA |

4 |

I |

X |

|

|

| R1591 |

Le plan2 |

FRA |

5 |

|

X |

|

|