1. Introduction

Grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs) is a collective term used to house a group of fungal diseases responsible for an array of symptoms associated with vascular infections (Bertsch et al. 2013, Bruez et al. 2013, Kenfaoui et al. 2022, Úrbez-Torres et al. 2012). Although GTDs are considered to be as old as Vitis vinifera cultivation (Larignon and Dubos 1997, Mugnai et al. 1999), during the last three decades they have re-emerged, with a dramatic impact on the longevity and the profitable vineyard lifespan, posing a considerable threat to the sustainability of the vitivinicultural sector worldwide (Claverie et al. 2020, Guerin-Dubrana et al. 2019, Mondello et al. 2018).

Numerous wood-inhabiting fungal species have been associated with GTDs, initiating infections of the perennial plant organs via wounds mostly induced during the annual pruning process or other cultural and propagation practices (Kanetis et al. 2022, Raimondo et al. 2019). The predominant GTD-associated, pathogenic taxa comprise the ascomycetous species Eutypa lata, Phaeomoniella chlamydospora, numerous species in the Botryosphaeriaceae, Diaporthales, genera of Phaeoacremonium, Ilyonectria, Dactylonectria, Cadophora, and species in the basidiomycetous taxa of Fomitiporia, Phellinus, and Stereum (Armengol et al. 2001, Larignon and Dubos 1997, Mugnai et al. 1999). However, recent research advances, as well as grapevine microbiome studies have increased our knowledge of the fungal species related to the GTD- complex (Bekris et al. 2021, Carlucci et al. 2017, Halleen et al. 2003, Elena et al. 2018, Geiger et al. 2022). Beyond well-known GTD pathogens, other fungal taxa have been found in association with GTDs, such as Biscogniauxia rosacearum (Bahmani et al. 2021), Macrophomina phaseolina (Abed-Ashtiani et al. 2018, Nouri et al. 2018), Truncatella angustata (Arzanlou et al. 2013, Raimondo et al. 2019), Neofabraea kienholzii (Lengyel et al. 2020), Neosetophoma italica (Testempasis et al. 2024), and numerous species of Cytospora (Arzanlou and Narmani 2015, Lawrence et al. 2017), Seimatosporium (Kanetis et al. 2022, Lawrence et al. 2018, Moghadam et al. 2022), Kalmusia (Abed-Ashtiani et al. 2019, Karácsony et al. 2021), Paraconiothyrium (DeKrey et al. 2022, Elena et al. 2018) Pestalotiopsis, Neopestalotiopsis (Jayawardena et al. 2015, Maharachchikumbura et al. 2016, Úrbez-Torres et al. 2009 and 2012), as well as Fusarium and Neocosmospora spp. associated with young vine decline (Bustamante et al. 2024).

The genus Kalmusia is placed in Didymosphaeriaceae (= Montagnulaceae) (Ariyawansa et al. 2014) and typified by K. ebuli Niessl., which was recently neotypified due to the loss of the original specimen (Zhang et al. 2014). Verkley et al. (2014) established the asexual genus Dendrothyrium, with D. variisporum (CBS 121517) as the type species, and described D. longisporum (CBS 582.83). However, later Ariyawansa et al. (2014) reported that these two species clustered together with K. ebuli, leading to the synonymy of Dendrothyrium under Kalmusia. According to Zhang et al. (2014), more than 40 species belong to Kalmusia. However, living ex-type strains and DNA sequence data are available for only eight species (i.e., K. araucariae, K. cordylines, K. ebuli, K. erioi, K. italica, K. longispora, K. spartii, and K. variispora). Species within Kalmusia are considered mainly saprobic, isolated from a variety of terrestrial habitats such as leaves, stumps, and dead branches of shrubs and trees (Gomzhina et al. 2022, Kadkhoda-Hematabadi et al. 2023, Khodaei et al. 2019, Liu et al. 2015, Manawasinghe et al. 2022, Verkley et al. 2014, Zhang et al. 2014; Crous et al. 2020), exhibiting also endophytic features (Bekris et al. 2021, Wijekoon and Quill 2021). To the best of our knowledge only two species of the genus, K. longispora and K. variispora have been reported as causal agents of plant diseases, mostly associated with diebacks of perennial organs of woody host plants (Abed-Ashtiani et al. 2019, Bashiri & Abdollahzadeh 2024, Karácsony et al. 2021, Martino et al. 2024, Testempasis et al. 2024, Travadon et al. 2022).

Plant pathogenic fungi employ a diverse secretome to depolymerize the main structural polysaccharide components of the plant cell wall, i.e., cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin (Kubicek et al. 2014). However, there is evidence of significant differences in the importance of specific cell wall degrading enzymes or families of enzymes even between species from the same genus (Garcia et al. 2024, Kenfaoui et al. 2022). Furthermore, recent advances in the research of major trunk disease-associated fungi suggest that the destructive colonization of grapevine tissues employ a variable arsenal of cell wall degrading enzymes and phytotoxic secondary metabolites that contribute to host damage and symptoms development (Garcia et al. 2024, Stempien et al. 2017).

During a field survey in the local vineyards in Cyprus, numerous K. variipora isolates were collected, in association with GTD-related symptoms. Our objectives are (a) to provide a morphological description and phylogenetic analyses of this under-studied GTD-associated species in Cyprus and (b) to evaluate its pathogenic potential under local conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling and Fungal Isolation

Isolates used in this study were collected from 15 vineyards (8 to 70 years old) of wine grape and table grape cultivars (Cabernet Sauvignon, Mavro, Shiraz, Superior, and Xynisteri) expressing typical GTD symptoms between 2017 and 2018 in the provinces of Nicosia, Limassol and Paphos, Cyprus (

Supplementary Table S1). Wood samples were collected from 3–4 plants per vineyard and brought to the laboratory to isolate and identify fungal species in symptomatic vascular tissues. Samples were debarked, washed with sterile double-distilled water (ddH

2O), and sectioned to reveal vascular symptoms. Small pieces (5 mm thick) of symptomatic tissues were disinfected in 95% ethyl alcohol for 1 min, rinsed with sterile ddH

2O, dried off on sterile filter papers (Whatman

TM) in laminar flow hood, and plated on potato dextrose agar (PDA, HiMedia) amended with streptomycin sulfate (50 μg/ml). Plates were then incubated at 25

oC in darkness until fungal colonies were observed and selected isolates were hyphal-tip purified to obtain pure cultures maintained under the same conditions and preserved in a 40% aqueous glycerol solution at -80

°C. A preliminary identification was conducted based on colony characteristics, leading to a collection of 19 pycnidial isolates with an olivaceous color. Representative isolates were deposited in our laboratory collection and the culture collection of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands (CBS) (

Supplementary Table S1).

2.2. Genomic DNA Extraction, PCR, and Sequencing

Mycelium was collected from 1-week-old colonies grown on malt extract agar (MEA) with a sterilized spatula avoiding taking parts of the culture medium to prevent any interference during the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) was used for the genomic DNA extraction, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fragments of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, the 28S large subunit gene of the rDNA (LSU), the 18S small subunit gene of the rDNA (SSU), the beta-tubulin gene (

b-tub), the translation elongation factor 1-alpha (

tef1-a), and the RNA polymerase II second largest subunit gene (

rpb2) were amplified using the following primer pairs: ITS5/ITS4 for ITS (White et al. 1990), LR0R/LR5 for LSU (Rehner and Samuels 1994, Vilgalys & Hester 1990), NS1/NS4 for SSU (White et al. 1990), T1/Bt2b for

b-tub (Glass et al. 1995, O’Donnell and Cigelnik 1997), EF1-728F/EF2 for

tef1-a (Carbone and Kohn 1999, O’Donnell and Cigelnik 1997), and 5F2/7cR for

rpb2 (Liu et al. 1999, Sung et al. 2007) (

Supplementary Table S2). PCR amplifications were performed on a thermal cycler (Labcycler SensoQuest GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) in a final volume of 13 μL. The reaction mix consisted of 8.45 μL sterile ddH

2O, 0.1 μL Taq DNA polymerase (5 U/μL BIOTAQ

TM DNA Polymerase, BioLine, Germany), 1.25 μL PCR buffer (10x NH

4 reaction buffer, BioLine, Germany), 0.5 μL MgCl

2 (50 mM, BioLine, Germany), 0.5 μL dNTP mix (10 mM, BioLine, Germany), 0.7 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), 0.25 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 1 μL of DNA template. The following amplification programs were used: initial denaturation at 94

°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94

°C for 45 sec, annealing for 45 sec at 52

°C for ITS and LSU, 48

°C for SSU and

b-tub, and 55

°C for

tef1-a and

rpb2, extension at 72

°C for 2 min, and a final extension at 72

°C for 8 min. For the verification of successful amplifications, electrophoreses were run on 1% (w/v) agarose gels prepared in Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer. PCR products were stained with GelRed Nucleic Acid gel stain (Biotium, Inc.).

For each PCR product (locus), two separate sequence reactions were performed, using the forward and reverse PCR primers, respectively, as indicated above. The sequencing PCR program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 15 sec, annealing at 52°C for 14 sec, and an extension at 60°C for 4 min. The PCR products were purified using Sephadex® G-50 Fine (GE Healthcare, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), according to manufacturer's procedures. Sequencing was made on an ABI Hitachi 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), in the facilities of the Westerdijk Institute.

Besides the Cypriot isolates, and due to the lack of available sequences of the genetic loci

b-tub,

tef1-a, and

rpb2 in the NCBI database, additional representative species of the genus

Kalmusia [

K. araucariae (CPC 37475

Τ),

K. ebuli (CBS 123120

ΝΤ),

K. longispora (CBS 582.83

Τ),

K. sarothamni (CBS 116474 and CBS 113833), and

K. variispora (CBS 121517

Τ);

Table 1] were obtained from CBS and the working collection of Pedro W. Crous (CPC) also housed at the Westerdijk Institute, and were sequenced to ensure a more robust phylogenetic analysis.

2.3. Phylogenetic Analyses

Evaluations of the chromatograms and consensus sequence assembly were made using the Software Geneious Prime

® (version 2022.0.1) (Kearse et al. 2012). All the sequences generated in this study were submitted to GenBank and the respective accession numbers are provided in

Table 1. Single gene alignments were performed for all loci using MAFFT v. 7 (

https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html, Katoh et al. 2019) with default settings, incorporating all available ex-type sequence data for

Kalmusia spp., plus additional data generated in this study (

Table 1). Alignments were checked and refined manually if needed using MEGA v. 6.06 software (Tamura et al. 2013). A 173 bp indel in

Neokalmusia brevispora (CBS 120248), and a 178 bp unalignable region were removed from the ITS and

tef1-a alignments, respectively, to ensure unambiguous alignment of all the included sequences. Alignments were combined using SequenceMatrix v. 1.9 program (Vaidya et al. 2011) into two separated multigene datasets: first, an rDNA multigene alignment based on ITS, LSU, and SSU was used to establish the position of Cyprus,

V. vinifera fungal isolates within an overview of the complete species diversity of the genus

Kalmusia. A second, 6-loci, multigene alignment based on

tef1-a, ITS, LSU,

rpb2, SSU, and

b-tub provided the final identification of the novel Cyprus isolates.

Phylogenetic analyses were based on Maximum-likelihood (ML) and Bayesian (B) analyses. Maximum-likelihood trees were constructed using IQ-TREE v. 2.1.3 (Minh et al. 2020), the best evolutionary model selection was performed using the TESTNEW option of ModelFinder (Kalyaanamoorthy et al. 2017) as implemented in IQ-TREE, and branch support was estimated using 1000 replicates of ultrafast bootstrap approximation (Hoang et al. 2018). As an additional measurement of ML branch support, 1000 replicates of nonparametric bootstrap (BS) were calculated using RAxML-HPC2 v. 8.2.12 on ACCESS, run on the CIPRES Science Gateway portal (Miller et al. 2012). The B analyses were run on the CIPRES Science Gateway portal using MrBayes on XSEDE v. 3.2.7a (Ronquist et al. 2012), and evolutionary models were calculated using MrModelTest v. 2.3 using the Akaike information criterion (Nylander 2004, Posada and Crandall 1998). Four incrementally heated MCMC chains were run for 5M generations, with the stop-rule option on. Sampling was set to every 1000 trees and after assessing convergence of the runs (average standard deviation of split frequencies below 0.01), 50% consensus trees and posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated discarding 25% of the initial samples as the burn-in fraction.

2.4. Morphological Characterization

Representative isolates (CBS 151327, CBS 151329, CBS 151331, and CBS 151334) from Cyprus were described based on the colony and microscopic characteristics of cultures grown on PDA, MEA (Sigma-Aldrich), and oatmeal agar (OA; Sigma-Aldrich) at 25°C for 2-3 weeks. Furthermore, segments of pine needles were autoclaved twice (121°C for 25 min, with a 24 h interval) and placed in Petri dishes containing water agar (Kanetis et al. 2022). Accordingly, mycelium plugs from actively growing cultures on PDAwere placed on the center of the plates. Fungal cultures were then incubated at room temperature under alternating near ultraviolet and white, fluorescent lights (Philips, TL-D 18W BLB, with a dominant wavelength (λ) at 365 nm and Radium, Spectacular© Plus NL-Τ8 18W/840, λmax = 590 nm, respectively) in a 12/12h photoperiod, and fruiting bodies (pycnidia) formation on pine needles was monitored daily for 1 week.

Morphological observations of reproductive structures were determined at appropriate magnifications using a Nikon ECLIPSE 80i microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan) and an Nikon AZ100 Multizoom microscope (Nikon, Japan), both equipped with a color digital camera Nikon DS-Ri2 (Nikon, Japan). Conidial color, shape, length, and width were recorded using the Nikon software NIS-elements D v. 4.50 and minimum, maximum, mean, and standard deviation were calculated.. Furthermore, colony morphology and colour per culture medium were rated following Rayner’s (1970) charts, accordingly.

2.5. Effect of Temperature on Mycelial Growth

The same group of isolates selected for the morphological characterization were used for the estimation of mycelial growth cardinal temperatures. Mycelial plugs (4 mm in diameter) from the margins of actively grown cultures were transferred into Petri dishes with PDA and incubated at six temperature regimes, from 10 to 30°C at 5°C increments and at 37°C. Furthermore, the mycelial growth rate of the same set of isolates was recorded on MEA and OA at 25°C, respectively. Overall, two perpendicular measurements of the diameter were recorded daily for 14 days. Three replicate plates were used per isolate and the experiment was repeated once. The optimum temperatures for mycelial growth and the maximum daily growth rate for each isolate were calculated based on regression curves of the temperature versus daily radial growth, according to Aigoun-Mouhous et al. (2021).

2.6. Exoenzyme Production

Endophytic fungi secrete enzymes that promote the degradation of structural macromolecules of plant cell walls, facilitating infection and colonization (Bertsch et al. 2013, Kenfaoui et al. 2022). The secretion of cellulase, pectinase, and laccase of six K. variispora isolates (CBS 151325, CBS 151327, CBS 151329, CBS 151330, CBS 151331, and CBS 1513340 were qualitatively examined on culture media that consisted of 200 ml M9 minimal salts, 5X concentrate (56.4 g per liter of ddH2O), 10 g of carboxymethylcellulose, 1.2 g yeast extract, 20 ml glucose (20%), 1ml MgSO4 (1M), 100 μl CaCl2 (1M), 15 g agar, for cellulase (Naik et al. 2008), 200 ml M9 minimal salts 5X concentrate, 5 g pectin, 1 ml MgSO4 (1M), 100 μl CaCl2 (1M), and 15 g agar, for pectinase (pectin was UV sterilized and mixed with the sterile medium following slight heating until melting) (Cattelan et al. 1999, Mohandas et al. 2018) and PDA that was amended with guaiacol (0.01% w/v) for laccase detection (Karácsony et al. 2021). Mycelial plugs (4 mm in diameter) were cut from the margins of actively growing cultures on PDA and placed in the center of the respective media-amended Petri dishes. Cultures were incubated at 25°C in darkness for 10 days and the production of the examined exoenzymes was qualitatively estimated. More specifically, for the visualization of cellulase and pectinase production, cultures were flooded with Gram’s iodine (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 5 minutes (Karácsony et al. 2021, Elshafie & Camele 2022, Kasana et al. 2008, Soares et al. 1999). After the cultures were rinsed with dH2O, the presence of distinct clearing zones around the colonies indicated enzyme production.. The formation of a red-brownish zone around the developed colony was indicative of laccase production (Devasia & Nair 2016).

2.7. Pathogenicity

In May 2020, the pathogenicity of 6 isolates (CBS 151221, CBS 151325, CBS 151327, CBS 151329, CBS 151330, and CBS 151334) was evaluated on potted plants under field conditions. Two-year-old plants of the local wine grape cultivar Mavro were grown in 10 L pots filled with potting mix (Miskaar, Lambrou Agro Ltd., Limassol, Cyprus) and amended with a slow-release fertilizer (Itapollina 12-5-15 SK, Lambrou Agro Ltd., Limassol, Cyprus). Plants were aseptically wounded between the third and fourth node from the base via a cork borer. Mycelial plugs of 4 mm in diameter from 7-day-old cultures on PDA were placed in the wound, coated with Vaseline (Unilever PMT Ltd., Nicosia, Cyprus), and wrapped with Parafilm (Sigma Aldrich) to avoid any contamination by any microorganism and dehydration. In addition, plants were also inoculated with sterile PDA plugs to serve as negative controls. Five plants were used per treatment in a completely randomized design and the experiment was repeated once. Plants were placed under a shading net for sun protection and were drip-irrigated 1-2 times per week (for 30 min and 0.5 L/h) according to their need. The plants remained outdoors for 12 months and were routinely inspected for foliar symptoms. Subsequently, the inoculated stems were excised and transferred to the laboratory for further analysis. Initially, the bark was scraped off and the length of wood discoloration was measured in both directions from the inoculation point. The canes were washed with an aqueous solution of 5% sodium hypochlorite for 2 min and then rinsed twice with sterile ddH2O. Subsequently, 4–6 small pieces (ca. 5 mm thick) that presented discoloration were cut from each inoculated stem. Wood segments were disinfected in 95% ethanol for 1 min and then placed on sterilized Whatman filter papers to dry in the laminar flow hood. Afterward, they were placed in PDA plates amended with streptomycin (50 mg/L) and incubated at 25°C in darkness for 1-2 weeks. Re-isolated colonies were identified based on their morphology.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

Regression curves were fitted over different temperature treatments versus the mycelial growth rate for each isolate. Data was analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test (non-parametric ANOVA). The optimum growth temperature was also calculated according to the developed equation per isolate. Data for wood discoloration were tested for normality and homogeneity of variance using Shapiro-Wilk’s and Bartlett’s tests, respectively. ANOVA was performed to evaluate differences in the length of wood discoloration between the different fungal treatments. Since variances were homogeneous the data was combined, and the means were compared with Tukey’s honestly significance (HSD) test at 5% of significance. All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (v. 25, IBM Corporation, New York, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analyses

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using ML and B methods to delimit the

Kalmusia isolates from Cyprus amongst the known diversity in the genus

Kalmusia. The composition of the different alignments and analyses are shown in

Table 2. The first analysis of rDNA sequences encompassed 25 isolates representing 9

Kalmusia spp., plus three outgroup taxa (

Neokalmusia brevispora CBS 120248,

Paraconiothyrium estuarinum CBS 109850

T, and

Paraconiothyrium hakeae CBS 142521) (

Figure 1). Phylogenetic analyses showed that the

Kalmusia isolates from Cyprus clustered within two non-clearly delimited sister groups, including the ex-type strains of

K. variispora (CBS 121517

Τ).

To establish an unequivocal phylogenetic position of the

Kalmusia isolates from Cyprus and

K. variispora, a second analysis was performed based on a 6-loci combined alignment (

tef1-a, ITS, LSU,

rpb2, SSU, and

b-tub) which included sequences from 21 isolates, representing five

Kalmusia spp. plus the three outgroup taxa as indicated above (

Figure 2). An initial assessment of the dataset using ML and B methods showed that the analyses were quite sensitive to missing data, largely affecting the three topologies and node support values, hence taxa lacking sequence data for two or more loci and for which ex-type strains were not available for the generation of additional sequence data (

K. cordylines ZHKUCC 21-0092

Τ,

K. erioi MFLUCC 18-0832

Τ,

K. italica MFLUCC 13-0066

Τ, and

K. spartii MFLUCC 14-0560

Τ) were excluded from the analyses. The analyses showed that the

Kalmusia isolates from Cyprus confidently resolved within a fully supported clade with the ex-type strain of

K. variispora (CBS 121517

Τ). With the exceptions of

K. sarothamni (supported by BS only) and the outgroup taxon

N. brevispora (not supported by any method), all additional species were confidently resolved in this analysis.

3.2. Morphological Characterization

Cultures on PDA were felty and flat, pale olivaceous with white aerial mycelium on the center and a smooth white margin (

Figure 3). On their reverse side colonies were grey olivaceous and smoke grey to olivaceous buff on the center with a white margin. On MEA the colonies were felty and flat, white with immersed pale grey mycelium on the center with a smooth margin, while their reverse side was pale luteous to pale buff. Colonies on OA were white with aerial, cottony mycelium, immersed glaucous grey to pale grey mycelium on the center, with a colorless to white margin. On the reverse side, the colonies were glaucous grey to pale olivaceous buff.

Conidiophores were 1-4-septate, acropleurogenous, simple or branched at the base, ranging 6.0-11.7 μm x 2.4-4.3 μm (av. 8.8 ± 1.3 x 3.2 ± 0.5 μm). Conidiogenous cells were phialidic, obclavate, narrowed toward the tip, hyaline, integrated, terminal and intercallary. Conidia were aseptate, ellipsoid to cylindrical, commonly straight, rarely curved with round tips, hyaline, thin-walled, containing 1-3 minute oil droplets, ranging 3.2-4.1 μm × 1.3-1.8 μm (av. 3.6 ± 0.2 × 1.5 ± 0.1 μm) with an average L/W ratio of 2.4 (

Figure 3). Pycnidia were spherical or irregular, dark brown to black, ranging 150-393 μm in diameter.

Figure 3.

Morphology of Kalmusia variispora isolate CBS 151327. (A-C) Colonies cultured on PDA, MEA and OA, respectively, inoculated at 25οC in the darkness for 14 days (top: above and bottom: reverse of the plate); (D) Pycnidium on a pine needle; (E, F) pycnidia from 7 day-old and 11-day-old colonies, respectively; (G) Conidia; (H) Group of conidiogenous cells and conidiophores; (I-K) Conidiogenous cells and conidiophores; (L-N) Different conidium growing stages. Scale bars: 50 μm (E, F), 10 μm (G) and 5 μm (H-N).

Figure 3.

Morphology of Kalmusia variispora isolate CBS 151327. (A-C) Colonies cultured on PDA, MEA and OA, respectively, inoculated at 25οC in the darkness for 14 days (top: above and bottom: reverse of the plate); (D) Pycnidium on a pine needle; (E, F) pycnidia from 7 day-old and 11-day-old colonies, respectively; (G) Conidia; (H) Group of conidiogenous cells and conidiophores; (I-K) Conidiogenous cells and conidiophores; (L-N) Different conidium growing stages. Scale bars: 50 μm (E, F), 10 μm (G) and 5 μm (H-N).

3.3. Effect of Temperature on Mycelial Growth

All

K. variispora isolates from Cyprus grew at all tested temperatures except at 37

°C. Analyses of variance indicated no significant differences (

p < 0.05) in the mycelial growth among experiments, thus data were combined. The correlation of mycelial growth to growth temperature was best described by a quadratic polynomial response model (y = aT

2 + bT + c). The optimum temperature for radial growth and the maximum daily radial growth were calculated in a fitted equation for each isolate. The coefficients of determination (R

2) ranged from 0.89 to 0.93 and based on the adjusted models derived per isolate the optimum temperatures of mycelial growth on PDA ranged from 22.18 to 22.92

°C (mean = 22.5

°C) (

Table 3). The maximum mycelial growth rates were not significantly different ranging from 3.92 to 4.36 mm/day (mean = 4.18 mm/day) (

Table 3).

Mycelial growth rates of

K. variispora isolates were also estimated on MEA and OA at 25

°C. The average growth rate on MEA ranged from 3.13 to 3.57 mm/day (mean = 3.81 mm/day). The highest average growth rate for all

K. variispora isolates was evident on OA ranging from 4.06 to 4.24 mm/day (mean = 4.14 mm/day), compared to ΜΕA and PDA (

Table 3 &

Supplementary Table S3). Overall, all tested isolates exhibited the highest growth rate on OA and the lowest on MEA (

Table 3 &

Supplementary Table S3).

3.4. Exoenzyme Production

Digestive exoenzyme production revealed differences between the tested isolates in this study (

Figure 4). All isolates were positive in cellulase production indicated by a distinct, clear, and prominent zone of clearance around the developed colonies with bluish-black coloration of the medium (

Figure 4A-4F). Equally large clearance zones were also evident for all isolates on the pectin agar medium, indicating pectinolytic activity (

Figure 4G-4L). On the other hand,

K. variispora isolates showed differential laccase activity (

Figure 4M-4R), ranging from wide to faint reddish-brown halos around the colony, with the absence of a zone in the case of the isolate CBS 151329 (

Figure 4P).

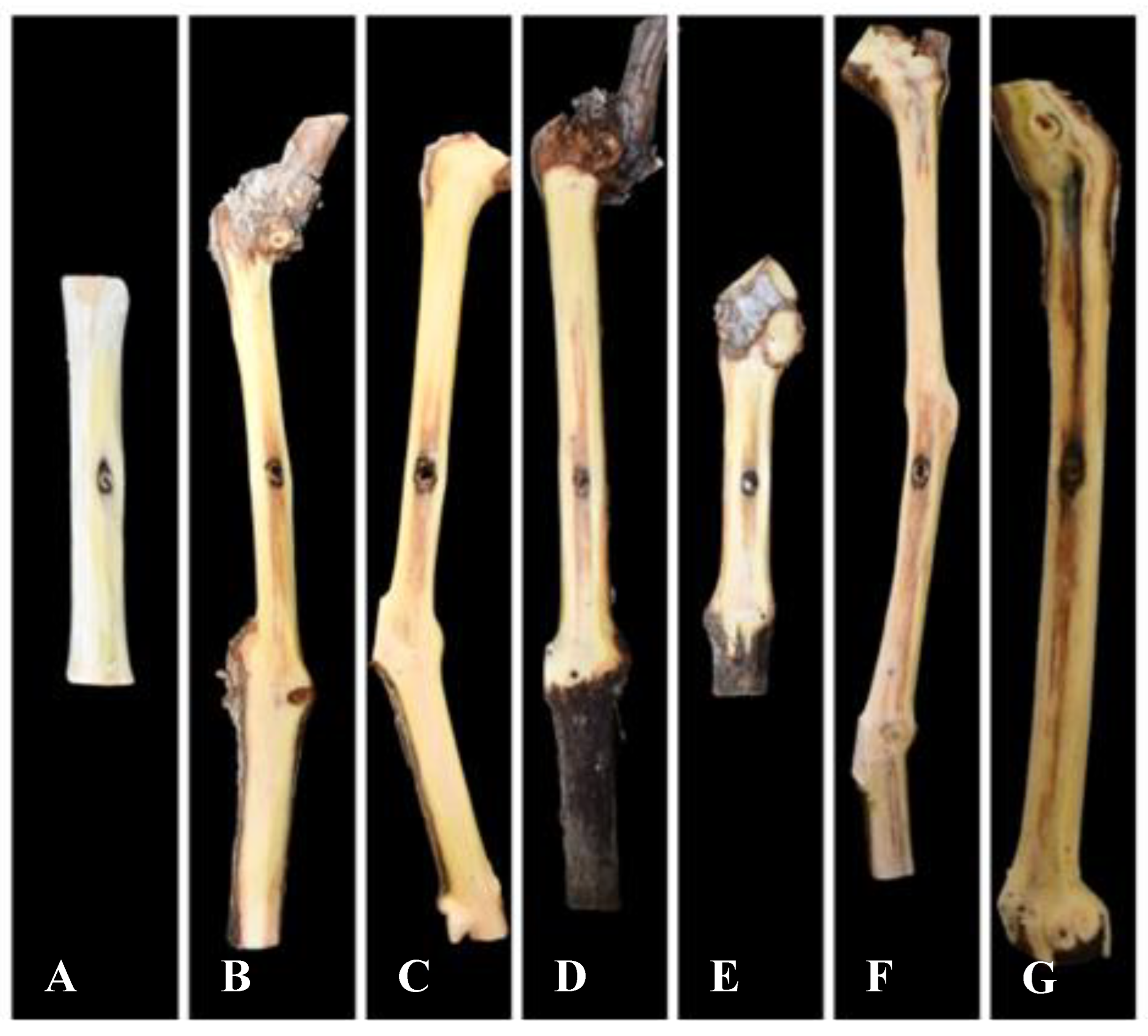

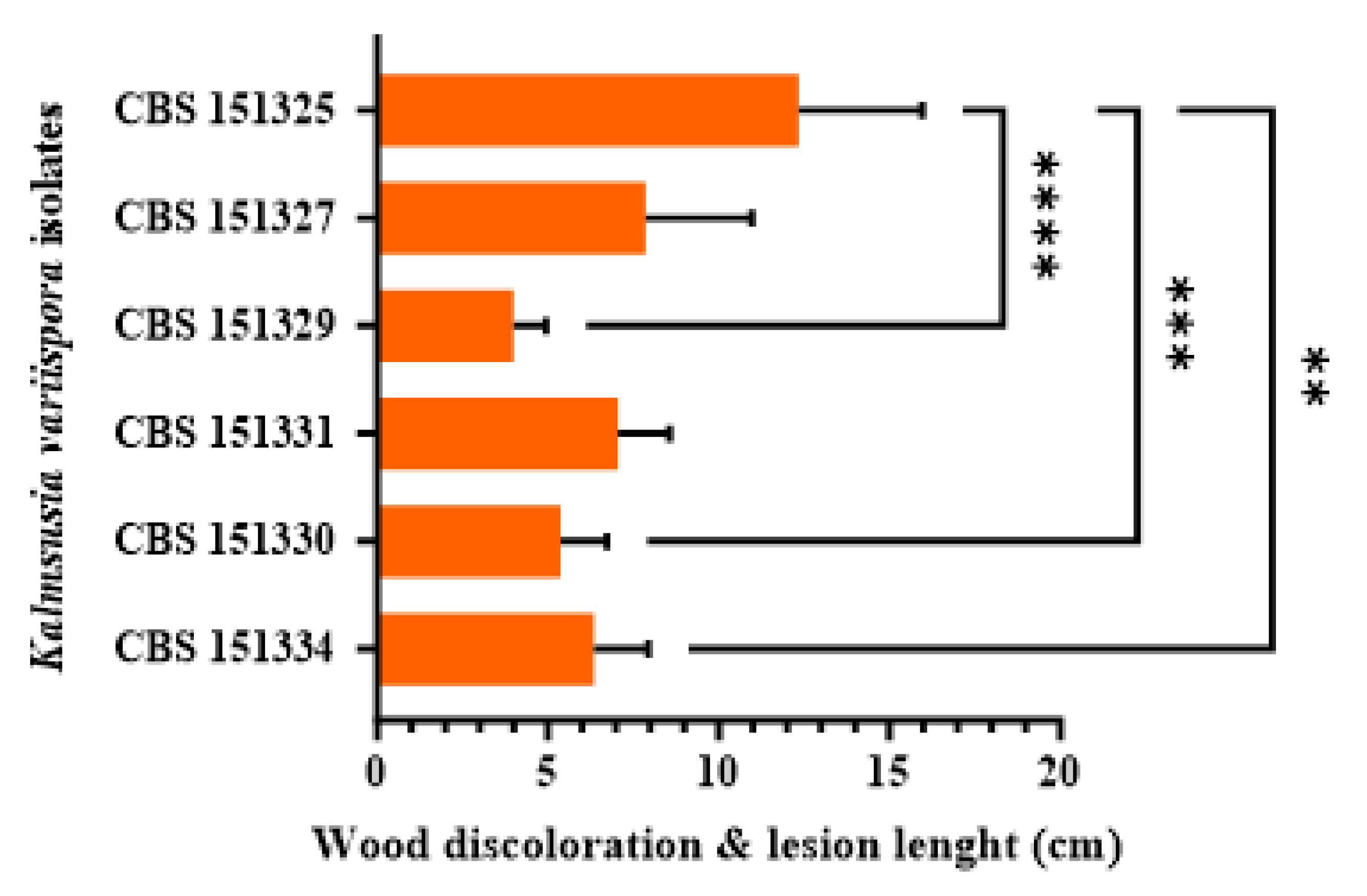

3.5. Pathogenicity

Twelve months post-inoculation, all tested

K. variispora isolates were found pathogenic to 2-year-old cv. Mavro potted grapevines. Light to dark brown wood discoloration and lesions of varying levels ranging from 12.3 to 4.0 cm long were developed upward and downward from the inoculated point of the canes (

Figure 5). Isolates CBS 151325, CBS 151327, and CBS 151331 were significantly more aggressive (12.3 ± 3.6 cm to 7 ± 1.5 cm) compared to CBS 151329 CBS 151330, and CBS 151334 (4 ± 1 to 6.3 ± 1.6 cm) (

p < 0.0001) (

Figure 6). No symptoms were developed on non-fungal inoculated plants (

Figure 5). Successful re-isolations were positive from all the fungal-inoculated plants with recovery percentages ranging from 45 to 84%. Retrieved isolates were confirmed with those used in grapevine inoculations based on morphology (cultural and conidial characteristics), while no fungal isolates were obtained from the negative-control plants.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first evidence of K. variispora associated with GTDs in Cyprus, offering a comprehensive cultural, morphological, and phylogenetic description of this plant pathogenic species. Despite the widespread impact of GTDs, research on their etiology in Cyprus (Kanetis et al. 2022; Makris et al. 2022) has been limited, making this study a valuable contribution to the field. Kalmusia variispora isolates were collected from grapevines of wine and table grape cultivars across Cyprus, exhibiting typical GTD symptoms such as cankers, dead cordons, and spurs. These symptoms are commonly associated with vines affected by Botryosphaeria dieback, Eutypa dieback, or Phomopsis dieback.

Kalmusia variispora (formerly Dendrothyrium variisporum) was initially isolated from declined grapevines in Syria and Erica carnea in Switzerland (Verkley et al. 2014). However, the pathogenicity of K. variispora on grapevines was first confirmed in Iran (Abed-Ashtiani et al. 2019), with subsequent reports from vineyards in North America (California and Washington) and Greece (Testempasis et al. 2024, Travadon et al. 2022). Additionally, Bekris et al. (2021) identified K. variispora as an indicator of GTDs-symptomatic grapevine plants due to its significantly higher relative abundance in the symptomatic plants in Greece (Bekris et al. 2021). Beyond grapevine, K. variispora has been reported as a major causal agent of the apple fruit core rot in Greece and Chile (Gutierrez et al. 2022, Ntasiou et al. 2021), as an endophyte of Rosa hybrida and Pinus eldarica (Abed-Ashtiani et al. 2019), while it has also been associated with oak decline in Iran, causing defoliation, vascular discoloration, and wood necrosis (Bashiri & Abdollahzadeh 2024). Furthermore, K. variispora has been isolated from necrotic wood of pomegranate, although pathogenicity has not been confirmed (Kadhoda-Hematabadi et al. 2023). Kalmusia longispora, a sister species of K. variispora has been also associated with GTDs (Karácsony et al. 2021) and apple tree diebacks (Martino et al. 2024) in Hungary and Italy, respectively.

The presence of GTD-related species has been commonly documented from asymptomatic mother plants and mature vines (Aroca et al. 2010; Fourie & Halleen 2004; Hofstetter et al. 2012), suggesing that they may remain latent for a period before transitioning to their pathogenic phase (Hrycan et al. 2020). Among these pathogens, species in the genus Ilyonectria are considered weak and/or opportunistic pathogens (Hrycan et al. 2020). GTDs are caused primarily by taxonomically unrelated Ascomycete fungi and, to a lesser extent, by Basidiomycete fungi (Gramaje et al. 2018). Beyond the well-known GTD pathogens, new reports have identified other fungi associated with GTDs, often isolated alongside the established GTD pathogens (Lawrence et al. 2018; Karácsony et al. 2021; Kanetis et al. 2022). The co-isolation of K. variispora in the current work with other GTD pathogens, highlights the complex etiology of GTDs. Among the 19 K. variispora isolates, seven were co-isolated from vine cankers with other known GTD-related pathogens in the family Botryosphaeriaceae, the genera Phaeoacremonium, or Seimatosporium, as well as with Phaeomoniella chlamydospora. Those isolates were identified based on colony and morphological features, and by sequencing of the ITS locus (data not shown). Mixed fungal infections are commonly found in vineyards supporting the complex nature of GTDs (Kanetis et al. 2022; Bekris et al. 2021). There is evidence that in some cases the simultaneous presence of more than one pathogen increases or decreases the severity of plant disease (Lawrence et al. 2018). Mixed infections could exacerbate disease severity and complicate management strategies.

Phylogenetic analyses revealed that all

Kalmusia isolates from Cyprus clustered with the type strain of

K. variispora (

Figure 3), confirming their identity as

K. variispora. Currently, the available sequences of

Kalmusia species in the NCBI database predominately refer to the ITS, LSU and SSU genetic loci, representing nine different species. The present work concluded that the LSU and SSU do not provide enough phylogenetically informative sites to support the identification of

Kalmusia at the species level (

Table 2). However, the remaining loci (ITS,

b-tub,

rpb2 and

tef1-a) were significantly more informative, and therefore we recommend using these loci for future phylogenetic studies on

Kalmusia. In addition, in this study, we provide molecular data from the available type strains preserved at the WI, making them accessible for future research through the NCBI database. The four representative

K. variispora isolates we isolated from local vineyards in Cyprus shared the same morphological characters with the type strain of

K. variispora species as described by Verkley et al. (2014).

Abed-Ashtiani et al. (2019) conducted a pathogenicity assay on K. variispora using green shoots of two-year-old potted grapevines in a greenhouse for a ten-week incubation period. The infected plants exhibited wilting, general decline, and brown discoloration of the wood. Species pathogenicity was further confirmed in North America by Travadon et al. (2022), who inoculated woody stems of potted grapevine plants in greenhouse conditions with a conidial suspension of 10 species (Biscogniauxia mediterranea, Cadophora columbiana, Cytospora viticola, Cytospora yakimana, Eutypella citricola, Flammulina filiformis, K. variispora, Phaeomoniella chlamydospora, and Thyrostroma sp.) found in association with GTDs in the states of California and Washinghton. Among all the tested species, K. variispora was found to be the most virulent. Similarly, Testempasis et al. (2024) assessed the pathogenicity of K. variispora on two-year-old grapevine canes in a 15-year-old vineyard for a six-month incubation period, where inoculated canes exhibited severe wood discoloration. All K. variispora isolates from the present study also caused light to dark brown wood discoloration symptoms, consistent with the symptoms observed in the field-collected samples, and were successfully re-isolated from the inoculated wood. The above-mentioned findings confirmed the presence of K. variispora in the GTDs-associated microbiome from countries in different continents and its ability to infect, colonize the grapevine wood, suggesting that it is a pathogen associated with grapevine trunk diseases worldwide.

The plant cell wall serves as a dynamic barrier against microbial infections that successful pathogenic microorganisms must overcome or degrade to invade their hosts (Bellincampi et al. 2014). To achieve that, pathogens need to secrete enzymes that degrade cell wall components such as cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin, and lignin particularly in woody tissues (Kubicek et al. 2014). The secretion of these degrading enzymes is a key pathogenicity factor that contributes to the pathogen's aggressiveness (Belair et al. 2022). Karácsony et al. (2021) evaluated K. longispora, another grapevine pathogen and found that it secretes cellulase, pectinase, and laccase, with laccase likely playing a significant role in its ability to cause vascular necrosis in grapevine. The consistent production of enzymes that degrade cellulose and pectin across all K. variispora isolates from grapevines in Cyprus emphasizes the importance of these enzymes in the pathogenicity of the species. However, the observed variability in ligninase production, where one isolate was not able to produce lignin-degrading enzymes, provides insights into the pathogen’s diverse enzymatic strategies. Furthermore, K. variispora has been shown to produce a wide array of phytotoxic metabolites (Cimmino et al., 2021).

Herein, we showed the ability of K. variispora to cause vascular discoloration on grapevines, as well as the possible importance of laccases in the development of its symptoms. This study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on GTD pathogens in Mediterranean vineyards. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report for K. variispora in grapevine in Cyprus.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1:

Kalmusia variispora isolates collected from vineyards in Cyprus; Table S2: PCR and sequencing primers used in this study; Table S3: Average daily

in vitro mycelial growth rate of

Kalmusia variispora isolates from vineyards in Cyprus at 25

°C on three different agar-based culture media.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design: L.K. and G.M.; interpretation of data and original draft preparation: L.K., G.M, and M.S.D..; analysis and interpretation of data and writing: L.K., G.M., and P.W.C.; performed analysis, interpretation of data and resources, revised draft manuscript and supervision, L.K., M.S.D., and P.W.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the start-up Grant EX200120, awarded to Loukas Kanetis by the Cyprus University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Solonas Solonos and Mr. Marios Christodoulou for the sampling and the sample process in the lab. We are also grateful to Dr. Michalis Christoforou for his support in the pathogenicity trial.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abed- Ashtiani, F.; Narmani, A.; Arzanlou, M. Macrophomina phaseolina associated with grapevine decline in Iran. 2018. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 57, 107-111. [CrossRef]

- Abed-Ashtiani, F.; Narmani, A.; Arzanlou, M. Analysis of Kalmusia variispora associated with grapevine decline in Iran. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2019, 154, 787-799. [CrossRef]

- Aigoun-Mouhous, W.; Mahamedi, A.E.; León, M.; Chaouia, C.; Zitouni, A.; Barankova, K.; Eichmeier, A.; Armengol, J.; Gramaje, D.; Berraf-Tebbaf, A. Cadophora sabaouae sp. nov. and Phaeoacremonium species associated with Petri disease on grapevine propagation material and young grapevines in Algeria. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3657-3668.

- Ariyawansa, H.A.; Tanaka, K.; Thambugala, K.M.; Phookamsak, R.; Tian, Q.; Camporesi, E.; Hongsanan, S.; Monkai, J.; Wanasinghe, D.N.; Mapook, A. et al. A molecular phylogenetic reappraisal of the Didymosphaeriaceae (= Montagnulaceae). Fungal Divers. 2014, 68, 69-104. [CrossRef]

- Armengol, J.; Vicent, A.; Torné, L.; García-Figueres, F.; García-Jiménez, J. Fungi associated with esca and grapevine declines in Spain: a three-year survey. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2001, 40, 325-329. [CrossRef]

- Aroca, Á.; Gramaje, D.; Armengol, J.; García-Jiménez, J.; Raposo, R. Evaluation of the grapevine nursery propagation process as a source of Phaeoacremonium spp. and Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and occurrence of trunk disease pathogens in rootstock mother vines in Spain. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 126, 165-174. [CrossRef]

- Arzanlou, M.; Narmani, A. ITS sequence data and morphology differentiate Cytospora chrysosperma associated with trunk disease of grapevine in northern Iran. J. Plant Prot. Res. 2015, 55, 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Arzanlou, M.; Narmani, A.; Moshari, S.; Khodaei, S.; Babai-Ahari, A. Truncatella angustata associated with grapevine trunk disease in northern Iran. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2013, 46, 1168-1181.

- Bahmani, Z.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Amini, J.; Evidente, A. Biscogniauxia rosacearum the charcoal canker agent as a pathogen associated with grapevine trunk diseases in Zagros region of Iran. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14098. [CrossRef]

- Bashiri, S.; Abdollahzadeh, J. Taxonomy and pathogenicity of fungi associated with oak decline in northern and central Zagros forests of Iran with emphasis on coelomycetous species. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1377441. [CrossRef]

- Bekris, F.; Vasileiadis, S.; Papadopoulou, E.; Samaras, A.; Testempasis, S.; Gkizi, D.; Tavlaki, G.; Tzima, A.; Paplomatas, E.; Markakis, E. et al. Grapevine wood microbiome analysis identifies key fungal pathogens and potential interactions with the bacterial community implicated in grapevine trunk disease appearance. Environ. Microbiome 2021, 16, 23. [CrossRef]

- Belair, M.; Grau, A.L.; Chong, J.; Tian, X.; Luo, J.; Guan, X.; Pensec, F. Pathogenicity factors of Botryosphaeriaceae associated with grapevine trunk diseases: New developments on their action on grapevine defense responses. Pathogens 2022, 11, 951. [CrossRef]

- Bellincampi, D.; Cervone, F.; Lionetti, V. Plant cell wall dynamics and wall-related susceptibility in plant-pathogen interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 228. [CrossRef]

- Bertsch, C.; Ramírez-Suero, M.; Magnin-Robert, M.; Larignon, P.; Chong, J.; Abou-Mansour, E.; Spagnolo, A.; Clément, C.; Fontaine, F. Grapevine trunk diseases: Complex and still poorly understood. Plant Pathol. 2013, 62, 243-265. [CrossRef]

- Bruez, E.; Lecomte, P.; Grosman, J.; Doublet, B.; Bertsch, C.; Fontaine, F.; Ugaglia, A.; Teissedre, P.L.; Da Costa, J.P.; Guerin-Dubrana, L.; Rey, P. Overview of grapevine trunk diseases in France in the 2000s. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2013, 52, 262-275.

- Bustamante, M.I.; Todd, C.; Elfar, K.; Hamid, M.I.; Garcia, J.F.; Cantu, D.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Eskalen, A. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium species associated with young vine decline in California. Plant Dis. 2019, 108, 1053-1061. [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553-556.

- Carlucci, A.; Lops, F.; Mostert, L.; Halleen, F.; Raimondo, M.L. Occurrence fungi causing black foot on young grapevines and nursery rootstock plants in Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr., 2017, 56, 10-39.

- Cattelan, A.J.; Hartel, P.G.; Fuhrmann J.J. Screening for plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria to promote early soybean growth. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1999, 63, 1670-1680. [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, A.; Bahmani Z.; Masi, M.; Di Lecce, R.; Amini, J.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Tuzi, A.; Evidente, A.; Massarilactones D and H, phytotoxins produced by Kalmusia variispora, associated with grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs) in Iran. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 5192-5198. [CrossRef]

- Claverie, M.; Notaro, M.; Fontaine, F.; Wery, J. Current knowledge on grapevine trunk diseases with complex etiology: a systemic approach. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2020, 59, 29-53. [CrossRef]

- Crous, P.W.; Wingfield, M.J.; Schumacher, R.K.; Akulov, A.; Bulgakov, T.S.; Carnegie, A.J.; Jurjević, Ž.; Decock, C.; Denman, S.; Lombard, L. et al. New and interesting fungi. 3. Fungal Syst. Evol. 2020, 6, 157-231. [CrossRef]

- DeKrey, D.H.; Klodd, A.E.; Clark, M.D.; Blanchette, R.A. Grapevine trunk diseases of cold-hardy varieties grown in northern midwest vineyards coincide with canker fungi and winter injury. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269555. [CrossRef]

- Devasia, S.; Nair, A.J. Screening of potent laccase-producing organisms based on the oxidation pattern of different phenolic substrates. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2016, 5, 127-137. [CrossRef]

- Elena, G.; Bruez, E.; Rey, P.; Luque, J. Microbiota of grapevine woody tissues with or without esca-foliar symptoms in northeast Spain. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2018, 57, 425-438.

- Elshafie, H.S.; Camele, I. Rhizospheric Actinomycetes revealed antifungal and plant-growth-promoting activities under controlled environment. Plants 2022, 11, 1872. [CrossRef]

- Fourie, P.H.; Halleen, F. Occurrence of grapevine trunk disease pathogens in rootstock mother plants in South Africa. Austalas. Plant Pathol. 2004, 33, 313-315. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.F.; Morales-Cruz, A.; Cochetel, N.; Minio, A.; Figueroa-Balderas, R.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Baumgartner, K.; Cantu, D. Comparative pangenomic insights into the distinct evolution of virulence factors among grapevine trunk pathogens. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2024, 37, 127-142. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Karácsony, Z.; Golen, R.; Váczy, K.Z.; Geml, J. The compositional turnover of grapevine-associated plant pathogenic fungal communities is greater among intraindividual microhabitats and terroirs than among healthy and esca-diseased plants. Phytopathology 2022, 112, 1029-1035. [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.L.; Donaldson, G.C. Development of primer sets designed for use with the PCR to amplify conserved genes from filamentous ascomycetes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1323-1330. [CrossRef]

- Gomzhina, M.M., Gasich, E.L., Gagkaeva, T.Y.; Gannibal, P.B. Biodiversity of fungi inhabiting European blueberry in north-western Russia and in Finland. Dokl Biol. Sci. 2022, 507, 441-455. [CrossRef]

- Gramaje, D.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Sosnowski, M.R. Managing grapevine trunk diseases with respect to etiology and epidemiology: current strategies and future prospects. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 12-39. [CrossRef]

- Guerin-Dubrana, L.; Fontaine, F.; Mugnai, L. Grapevine trunk disease in European and Mediterranean vineyards: occurrence, distribution, and associated disease-affecting cultural factors. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2019, 58, 49-71.

- Gutierrez, M.; Pinheiro, C.; Duarte, J.; Sumonte, C.; Ferrada, E.E.; Elfar, K.; Eskalen, A.; Lolas, M.; Galdós, L.; Díaz, G.A. Severe outbreak of dry core rot in apple fruits cv. Fuji caused by Kalmusia variispora during preharvest in Maule region, Chile. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 2750.

- Halleen, F.; Crous, P.W.; Petrini, O. Fungi associated with healthy grapevine cuttings in nurseries, with special reference to pathogens involved in the decline of young vines. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2003, 32, 47-52. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518-522. [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, V.; Buyck, B.; Croll, D.; Viret, O.; Couloux, A.; Gindro, K. What if esca disease of grapevine were not a fungal disease? Fungal Divers. 2012, 54, 51-67.

- Hrycan, J.; Hart, M.; Bowen, P.; Forge, T.; Úrbez-Torres, J.R. Grapevine trunk disease fungi: their roles as latent pathogens and stress factors that favour disease development and symptom expression. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2020, 59, 395-424.

- Jayawardena, R.S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, M.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.B.; Nilthong, S.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, X.H.; Yan, J. et al. Identification and characterization of Pestalotiopsis-like fungi related to grapevine diseases in China. Fungal Biol. 2015, 119, 348-361. [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587-589. [CrossRef]

- Kanetis, L.I.; Taliadoros, D.; Makris, G.; Christoforou, M. A novel Seimatosporium and other Sporocadaceae species associated with Grapevine Trunk Diseases in Cyprus. Plants 2022, 11, 2733. [CrossRef]

- Karácsony, Z.; Knapp, D.G.; Lengyel, S.; Kovács, G.M.; Váczy, K.Z. The fungus Kalmusia longispora is able to cause vascular necrosis on Vitis vinifera. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258043. [CrossRef]

- Kasana, R.C.; Salwan, R.; Dhar, H.; Dutt, S.; Gulati, A. A rapid and easy method for the detection of microbial cellulases on agar plates using Gram’s iodine. Curr. Microbiol. 2008, 57, 503-507. [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Rozewicki, J.; Yamada, K.D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019, 20, 1160-1166. [CrossRef]

- Kearse, M.; Moir, R.; Wilson, A.; Stones-Havas, S.; Cheung, M.; Sturrock, S.; Buxton, S.; Cooper, A.; Markowitz, S.; Duran, C. et al. Geneious Basic: An integrated and extendable desktop software platform for the organization and analysis of sequence data. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1647-1649. [CrossRef]

- Kenfaoui, J.; Radouane, N.; Mennani, M.; Tahiri, A.; El Ghadraoui, L.; Belabess, Z.; Fontaine, F.; El Hamss, H.; Amiri, S.; Lahlali, R.; et al. A Panoramic view on grapevine trunk diseases threats: Case of Eutypa dieback, Botryosphaeria dieback, and Esca disease. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 595. [CrossRef]

- Kadkhoda-Hematabadi, S.; Mohammadi, H.; Sohrabi, M. Morphological and molecular identification of plant pathogenic fungi associated with necrotic wood tissues of pomegranate trees in Iran. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 105, 465-479. [CrossRef]

- Khodaei, S.; Arzanlou, M.; Babai-Ahari, A.; Rota-Stabelli, O.; Pertot, I. Phylogeny and evolution of Didymosphaeriaceae (Pleosporales): new Iranian samples and hosts, first divergence estimates, and multiple evidences of species mis-identifications. Phytotaxa 2019, 424, 131–146. [CrossRef]

- Larignon, P.; Dubos, B. Fungi associated with esca disease in grapevine. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 1997, 103, 147-157. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P.; Travadon, R.; Baumgartner, K. Novel Seimatosporium species from grapevine in northern California and their interactions with fungal pathogens involved in the trunk-disease complex. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1081-1092. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, D.P.; Travadon, R.; Pouzoulet, J.; Rolshausen, P.E.; Wilcox, W.F.; Baumgartner, K. Characterization of Cytospora isolates from wood cankers of declining grapevine in north America, with the descriptions of two new Cytospora species. Plant Pathol. 2017, 66, 713-725.

- Lengyel, S.; Knapp, D.G.; Karácsony, Z.; Geml, J.; Tempfli, B.; Kovács, G.M.; Váczy, K.Z. Neofabraea kienholzii, a novel causal agent of grapevine trunk diseases in Hungary. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2020, 157, 975-984. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.K.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Bhat, D.J.; Boonmee, S.; Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N., McKenzie, E.H.C.; Phookamsak, R.; Phukhamsakda, C. et al. Fungal diversity notes 1-110: taxonomic and phylogenetic contributions to fungal species. Fungal Divers. 2015, 72, 1-197. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.J.; Whelen, S.; Hall, B.D. Phylogenetic relationships among Ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerase II subunit. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1999, 16, 1799-1808. [CrossRef]

- Kanetis, L.I.; Taliadoros, D.; Makris, G.; Christoforou, M. A novel Seimatosporium and other Sporocadaceae species associated with grapevine trunk diseases in Cyprus. Plants, 2022, 11, 2733. [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, C.P.; Starr, T.L.; Glass, N.L. Plant cell wall-degrading enzymes and their secretion in plant-pathogenic fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2014; 52, 427-451. [CrossRef]

- Maharachchikumbura, S.S.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Jones, E.B.G.; McKenzie, E.H.C.; Bhat, J.D.; Dayarathne, M.C.; Huang, S.K.; Norphanphoun, C.; Senanayake, I.C.; Perera, R.H. et al. Families of Sordariomycetes. Fungal Divers. 2016, 79, 1-317. [CrossRef]

- Makris, G.; Solonos, S.; Christodoulou, M.; Kanetis, L.I. First report of Diaporthe foeniculina associated with grapevine trunk diseases on Vitis vinifera in Cyprus. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 1294. [CrossRef]

- Manawasinghe, I.S.; Calabon, M.S.; Jones, E.B.G.; Zhang, Y.X.; Liao, C.F.; Xiong, Y.R.; Chaiwan, N.; Kularathnage, N.D.; Liu, N.G.; Tang, S.M. et al. (2022) Mycosphere notes 345-386. Mycosphere 2022, 13, 454-557.

- Martino, I.; Agustí-Brisach, C.; Nari, L.; Gullino, M.L.; Guarnaccia, V. Characterization and pathogenicity of fungal species associated with dieback of apple trees in northern Italy. Plant Dis. 2024, 108, 311-331. [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Pfeiffer, W.; Schwartz, T. The CIPRES science gateway: enabling high-impact science for phylogenetics researchers with limited resources. In: Proceedings of the 1st conference of the extreme science and engineering discovery environment: bridging from the extreme to the campus and beyond (XSEDE ‘12), edited by Stewart, C. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, 2012, 1-8.

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530-1534. [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, J.N.; Khaledi, E.; Abdollahzadeh, J.; Amini, J. Seimatosporium marivanicum, Sporocadus kurdistanicus, and Xenoseimatosporium kurdistanicum: three new pestalotioid species associated with grapevine trunk diseases from the Kurdistan province, Iran. Mycol. Prog. 2022, 21, 427-446. [CrossRef]

- Mohandas, A.; Raveendran, S.; Parameswaran, B.; Abraham, A.; Athira, R.S.R.; Mathew, A.K.; Pandey, A. Production of pectinase from Bacillus sonorensis MPTD1. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 110-116. [CrossRef]

- Mondello, V.; Songy, A.; Battiston, E.; Pinto, C.; Coppin, C.; Trotel-Aziz, P.; Clément, C.; Mugnai, L.; Fontaine, F. Grapevine trunk diseases: a review of fifteen years of trials for their control with chemicals and biocontrol agents. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 1189-1217. [CrossRef]

- Mugnai, L.; Graniti, A.; Surico, G. Esca (black measles) and brown wood-streaking: two old and elusive diseases of grapevines. Plant Dis. 1999, 83, 404-418. [CrossRef]

- Naik, P.R.; Raman, G.; Narayanan, K.B.; Sakthivel, N. Assessment of genetic and functional diversity of phosphate solubilizing fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from rhizospheric soil. BMC Microbiol. 2008, 8, 230. [CrossRef]

- Ntasiou, P.; Samaras, A.; Karaoglanidis G. Apple fruit core rot agents in Greece and control with succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 3072-3081. [CrossRef]

- Nouri, M.T.; Zhuang, G.; Culumber, C.M.; Trouillas, F.P. First report of Macrophomina phaseolina causing trunk and cordon canker disease of grapevine in the United States. 2018, Plant Dis. 103, 579. [CrossRef]

- Nylander, J.A.A. MrModeltest v2. Program distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, 2004.

- O’Donnell, K.; Cigelnik, E. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 1997, 7, 103-116. [CrossRef]

- Posada, D.; Crandall, K.A. MODELTEST: testing the model of DNA substitution. Bioinformatics 1998, 14, 817-818. [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M.L.; Carlucci, A.; Ciccarone, C.; Sadallah, A.; Lops, F. Identification and pathogenicity of lignicolous fungi associated with grapevine trunk diseases in southern Italy. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2019, 58, 639-662.

- Rayner, R.W. A mycological colour chart; Commonwealth Mycological Institute: Kew, Surrey, UK, 1970.

- Rehner, S.A.; Samuels, G.J. Taxonomy and phylogeny of Gliocladium analysed from nuclear large subunit ribosomal DNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 1994, 98, 625-634. [CrossRef]

- Ronquist; F.; Teslenko, M.; van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol. 2012, 61, 539-542. [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.M.C.N.; da Silva, R.; Gomes, E. Screening of bacterial strains for pectinolytic activity: characterization of the polygalacturonase produced by Bacillus sp. Rev. Microbiol. 1999, 30, 299-303. [CrossRef]

- Stempien, E.; Goddard, M.L.; Wilhelm, K.; Tarnus, C.; Bertsch, C. Chong, J. Grapevine Botryosphaeria dieback fungi have specific aggressiveness factor repertory involved in wood decay and stilbene metabolization. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12, e0188766. [CrossRef]

- Sung, G.H.; Sung, J.M.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Spatafora, J.W. A multi-gene phylogeny of Clavicipitaceae (Ascomycota, Fungi): Identification of localized incongruence using a combinational bootstrap approach. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 44, 1204-1223. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar. S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30 2725-2729.

- Testempasis, S.I.; Markakis, E.A.; Tavlaki, G.I.; Soultatos, S.K.; Tsoukas, C.; Gkizi, D.; Tzima, A.K.; Paplomatas, E.; Karaoglanidis, G.S. Grapevine trunk diseases in Greece: Disease incidence and fungi involved in discrete geographical zones and varieties. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 2. [CrossRef]

- Travadon, R.; Lawrence, D.P.; Moyer, M.M.; Fujiyoshi, P.T.; Baumgartner, K. Fungal species associated with grapevine trunk diseases in Washington wine grapes and California table grapes, with novelties in the genera Cadophora, Cytospora, and Sporocadus. Front. Fungal Bio. 2022, 3, 1018140. [CrossRef]

- Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Adams, P.; Kamas, J.; Gubler, W.D. Identification, incidence, and pathogenicity of fungal species associated with grapevine dieback in Texas. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2009, 60, 497-507. [CrossRef]

- Úrbez-Torres, J.R.; Peduto, F.; Striegler, R.K.; Urrea-Romero, K.E.; Rupe, J.C.; Cartwright, R.D.; Gubler, W.D. Characterization of fungal pathogens associated with grapevine trunk diseases in Arkansas and Missouri. Fungal Divers. 2012, 52, 169-189. [CrossRef]

- Verkley, G.J.M.; Dukik, K.; Renfurm, R.; Göker, M.; Stielow, J.B. Novel genera and species of coniothyrium-like fungi in Montagnulaceae (Ascomycota). Persoonia 2014, 32, 25-51. [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, G.; Lohman, D.J.; Meier, R. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 2011, 27, 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Vilgalys, R.; Hester, M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 1990, 172, 4238-4246. [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols. A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, M.A. Gelfand, D.H., Sninsky, J.J., White, T.J., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 315-322.

- Wijekoon, C.; Quill, Z. Fungal endophyte diversity in table grapes. Can. J. Microbiol. 2021, 67, 29-36. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Fournier, J.; Crous, P.W.; Zhang, X.; Li, W.; Ariyawansa, H.A.; Hyde, K.D. Neotypification and phylogeny of Kalmusia. Phytotataxa 2014, 176, 164-173. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Maximum-Likelihood (IQ-TREE-ML) consensus tree inferred from combined rDNA sequences (ITS, LSU, and SSU) of the genus Kalmusia. Numbers at the nodes indicate support values (IQ-TREE Uboot, RAxML-BS and B-PP) above 70% (Uboot and BS) and 0.95 (B). Thickened branches indicate full support (Uboot and BS = 100%, and PP = 1). The scale bar indicates expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Neokalmusia brevispora CBS 120248, Paraconiothyrium estuarinum CBS 109850T, and Paraconiothyrium hakeae CBS 142521. Ex-neotype and ex-type strains are indicated with NT and T, respectively.

Figure 1.

Maximum-Likelihood (IQ-TREE-ML) consensus tree inferred from combined rDNA sequences (ITS, LSU, and SSU) of the genus Kalmusia. Numbers at the nodes indicate support values (IQ-TREE Uboot, RAxML-BS and B-PP) above 70% (Uboot and BS) and 0.95 (B). Thickened branches indicate full support (Uboot and BS = 100%, and PP = 1). The scale bar indicates expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Neokalmusia brevispora CBS 120248, Paraconiothyrium estuarinum CBS 109850T, and Paraconiothyrium hakeae CBS 142521. Ex-neotype and ex-type strains are indicated with NT and T, respectively.

Figure 2.

Maximum-Likelihood (IQ-TREE-ML) consensus tree inferred from the combined 6-loci dataset (tef1-a, ITS, LSU, rpb2, SSU, and b-tub) of representative species of the genus Kalmusia. Numbers at the nodes indicate support values (IQ-TREE Uboot, RAxML-BS and B-PP) above 70% (Uboot and BS) and 0.95 (B). Thickened branches indicate full support (Uboot and BS = 100%, and PP = 1). The scale bar indicates expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Neokalmusia brevispora CBS 120248, Paraconiothyrium estuarinum CBS 109850T, and Paraconiothyrium hakeae CBS 142521. Ex-neotype and ex-type strains are indicated with NT and T, respectively.

Figure 2.

Maximum-Likelihood (IQ-TREE-ML) consensus tree inferred from the combined 6-loci dataset (tef1-a, ITS, LSU, rpb2, SSU, and b-tub) of representative species of the genus Kalmusia. Numbers at the nodes indicate support values (IQ-TREE Uboot, RAxML-BS and B-PP) above 70% (Uboot and BS) and 0.95 (B). Thickened branches indicate full support (Uboot and BS = 100%, and PP = 1). The scale bar indicates expected changes per site. The tree is rooted to Neokalmusia brevispora CBS 120248, Paraconiothyrium estuarinum CBS 109850T, and Paraconiothyrium hakeae CBS 142521. Ex-neotype and ex-type strains are indicated with NT and T, respectively.

Figure 4.

Exoenzyme production of Kalmusia variispora isolates CBS 151334 (A, G, M), CBS 151330 (B, H, N), CBS 151331 (C, I, O), CBS 151329 (D, J, P), CBS 151327 (E, K, Q), and CBS 151325 (F, L, R) growing on indicative media for cellulase (A-F), pectinase (G-L), and laccase (M-R) production. Photographs were taken after 10 days of incubation at 25oC in darkness. .

Figure 4.

Exoenzyme production of Kalmusia variispora isolates CBS 151334 (A, G, M), CBS 151330 (B, H, N), CBS 151331 (C, I, O), CBS 151329 (D, J, P), CBS 151327 (E, K, Q), and CBS 151325 (F, L, R) growing on indicative media for cellulase (A-F), pectinase (G-L), and laccase (M-R) production. Photographs were taken after 10 days of incubation at 25oC in darkness. .

Figure 5.

Pathogenicity of Kalmusia variispora isolates collected from vineyards in Cyprus, on 2-year-old potted vines (cv. Mavro). Wood discolorations and lesions were caused on lignified canes by isolates CBS 151334 (B), CBS 151330 (C), CBS 151221 (D), CBS 151329 (E), CBS 151327 (F), and CBS 151325 (G), 12 months post-inoculation. Mock-inoculated canes (A) did not exhibit symptoms. .

Figure 5.

Pathogenicity of Kalmusia variispora isolates collected from vineyards in Cyprus, on 2-year-old potted vines (cv. Mavro). Wood discolorations and lesions were caused on lignified canes by isolates CBS 151334 (B), CBS 151330 (C), CBS 151221 (D), CBS 151329 (E), CBS 151327 (F), and CBS 151325 (G), 12 months post-inoculation. Mock-inoculated canes (A) did not exhibit symptoms. .

Figure 6.

Mean lesion and wood discoloration lengths caused at 12 months post-inoculation by Kalmusia variispora isolates on 2-year-old vines (cv. Mavro) in pathogenicity assays under field conditions. Each bar represents an individual tested isolate and vertical error bars indicate the corresponding standard deviation. Asterisks (****, ***, and **) indicate statistically significant differences (p <0.0001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.01), following the analysis of variance and Tukey’s mean separation test procedures.

Figure 6.

Mean lesion and wood discoloration lengths caused at 12 months post-inoculation by Kalmusia variispora isolates on 2-year-old vines (cv. Mavro) in pathogenicity assays under field conditions. Each bar represents an individual tested isolate and vertical error bars indicate the corresponding standard deviation. Asterisks (****, ***, and **) indicate statistically significant differences (p <0.0001, p < 0.001, and p < 0.01), following the analysis of variance and Tukey’s mean separation test procedures.

Table 1.

Fungal taxa used for phylogenetic analyses in the current study. .

Table 1.

Fungal taxa used for phylogenetic analyses in the current study. .

| Species |

Strain a,b

|

Country |

Host |

GenBank accession number c

|

| ITS |

LSU |

SSU |

b-tub |

rpb2 |

tef1-a |

| Kalmusia araucariae |

CPC 37475T

|

USA |

Araucaria bidwillii |

MT223805 |

PP664292 |

PP667340 |

- |

PP715462 |

PP715503 |

| K. cordylines |

ZHKUCC 21-0092T

|

China |

Cordyline fruticosa |

OL352082 |

OL818333 |

OL818335 |

- |

- |

- |

| K. ebuli |

CBS 123120NT

|

France |

Populus tremula |

PP667315 |

PP664289 |

PP667335 |

PP715468 |

PP715447 |

PP715488 |

| K. erioi |

MFLUCC 18-0832T

|

Thailand |

- |

MN473058 |

MN473052 |

MN473046 |

MN481603 |

- |

- |

| K. italica |

MFLUCC 13-0066T

|

Italy |

Spartium junceum |

KP325440 |

KP325441 |

KP325442 |

- |

- |

- |

| K. longispora |

CBS 582.83T

|

Canada |

Arceuthobium pusillum |

JX496097 |

JX496210 |

PP667338 |

PP715481 |

PP715460 |

PP715501 |

| K. sarothamni |

CBS 116474 |

- |

- |

PP667313 |

PP664288 |

PP667332 |

PP715466 |

PP715444 |

PP715485 |

| K. sarothamni |

CBS 113833 |

- |

- |

PP667311 |

PP664287 |

PP667331 |

PP715463 |

PP715442 |

PP715483 |

| K. spartii |

MFLUCC 14-0560T

|

Italy |

S. junceum |

KP744441 |

KP744487 |

KP753953 |

- |

- |

- |

| K. variispora |

CBS 121517 |

Syria |

Vitis vinifera |

PP667314 |

JX496143 |

PP667334 |

PP715467 |

PP715446 |

PP715487 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151324 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

PP667316 |

PP664290 |

PP667336 |

PP715469 |

PP715448 |

PP715489 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151325 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312148 |

MZ312183 |

MZ312321 |

PP715470 |

PP715449 |

PP715490 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151326 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312149 |

MZ312184 |

MZ312322 |

PP715471 |

PP715450 |

PP715491 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151327 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312138 |

MZ312173 |

MZ312311 |

PP715472 |

PP715451 |

PP715492 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151328 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

PP667317 |

PP664291 |

PP667337 |

PP715473 |

PP715452 |

PP715493 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151329 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312140 |

MZ312175 |

MZ312313 |

PP715474 |

PP715453 |

PP715494 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151330 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312141 |

MZ312176 |

MZ312314 |

PP715475 |

PP715454 |

PP715495 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151331 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312143 |

MZ312178 |

MZ312316 |

PP715476 |

PP715455 |

PP715496 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151332 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312139 |

MZ312174 |

MZ312312 |

PP715477 |

PP715456 |

PP715497 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151333 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312144 |

MZ312179 |

MZ312317 |

PP715478 |

PP715457 |

PP715498 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151334 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312142 |

MZ312177 |

MZ312315 |

PP715479 |

PP715458 |

PP715499 |

| K. variispora |

CBS 151335 |

Cyprus |

V. vinifera |

MZ312151 |

MZ312186 |

MZ312324 |

PP715480 |

PP715459 |

PP715500 |

| Neokalmusia brevispora |

CBS 120248 |

Japan |

Sasa sp. |

MH863078 |

JX681110 |

PP667333 |

PP715464 |

PP715445 |

PP715486 |

| Paraconiothyrium estuarinum |

CBS 109850T

|

Brazil |

estuarine sediment |

MH862842 |

MH874432 |

AY642522 |

JX496355 |

- |

LT854937 |

| P. hakeae |

CBS 142521 |

Australia |

Hakea sp. |

KY979754 |

KY979809 |

- |

KY979920 |

KY979892 |

KY979892 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of the different datasets and statistics of phylogenetic analyses used in this study. .

Table 2.

Characteristics of the different datasets and statistics of phylogenetic analyses used in this study. .

| |

|

Number of sites |

Evolutionary models b

|

| Dataset |

Partition a

|

Total |

Informative |

Invariable |

Bayesian unique site patterns |

IQ-TREE |

Bayesian |

| rDNA |

ITS |

576 |

91 |

376 |

196 |

TNe+G4 |

HKY+G |

| LSU |

864 |

15 |

808 |

63 |

TNe+I |

GTR+G |

| SSU |

1021 |

9 |

1001 |

63 |

K2P+I |

HKY+I |

| 6-loci combined |

tef1-a |

487 |

56 |

343 |

151 |

TNe+R3 |

GTR+I+G |

| ITS |

573 |

70 |

447 |

133 |

TNe+G4 |

HKY+G |

| LSU |

863 |

13 |

820 |

46 |

TNe+I |

GTR+I |

| rpb2 |

902 |

204 |

565 |

264 |

TNe+G4 |

GTR+G |

| SSU |

1021 |

8 |

1001 |

46 |

K2P+I |

HKY+I |

| b-tub |

643 |

98 |

463 |

155 |

K2P+G4 |

HKY+G |

Table 3.

Temperature-mycelial growth relationship for four Kalmusia variispora isolates collected from vineyards in Cyprus.

Table 3.

Temperature-mycelial growth relationship for four Kalmusia variispora isolates collected from vineyards in Cyprus.

| Isolate |

Adjusted Model x

|

Optimum temperature

(°C) y

|

Growth rate (mm/day) z

|

| R2

|

a |

b |

c |

| CBS 151327 |

0.89 |

-0.017 |

0.7850 |

-47.854 |

22.18 a |

3.92 |

| CBS 151331 |

0.90 |

-0.020 |

0.9305 |

-62.999 |

22.92 a |

4.36 |

| CBS 151328 |

0.93 |

-0.018 |

0.8052 |

-483.334 |

22.24 a |

4.12 |

| CBS 151329 |

0.90 |

-0.019 |

0.8649 |

-54.839 |

22.64 a |

4.31 |

| Mean |

|

|

|

|

22.5 |

4.18 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).