1. Introduction

The genus

Diaporthe Nitschke (anamorph:

Phomopsis (Sacc.) Bubák, family: Diaporthaceae), comprises taxonomically diverse species, among which are important phytopathogens, non-pathogenic endophytes, and saprobic species [

1,

2,

3]. More than 800 species have been described in the genus [

4], with a wide geographical distribution and a broad host range, including mammals and humans [

5,

6,

7]. Moreover, many of them have been reported to be responsible for several losses in economically important crops, causing significant diseases with different symptomatology like fruit rots, stem cankers, stem blights, leaf spots, and diebacks [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Several studies have shown that more than one

Diaporthe species can co-occur in a single symptomatic host plant, hypothesizing that diseases are caused by a complex of

Diaporthe fungi rather than from a single species [

11,

12,

13]. A glaring example showcasing this phenomenon, is the association of several

Diaporthe species with different soybean diseases, namely seed decay, pod and stem blight, and stem canker [

14,

15], as well as the stem canker disease of sunflowers caused by numerous

Diaporthe species, identified in recent studies [

16,

17].

In grapevine, Phomopsis cane and leaf spot (PCLS) is a very well-known disease since the late 1950s, which was mainly attributed to

Phomopsis viticola [

18]. Since the recommendations by [

19] of using the generic name

Diaporthe over

Phomopsis, several

Diaporthe species associated with canker diseases of grapevine in Europe and other countries have been documented [

11,

20,

21]. A number of studies conducted in Europe, South Australia and Western North America, state that

D. ampelina (former

P. viticola) is the predominant and most virulent species with high isolation frequencies [

11,

22,

23]. Other species like the type species

D. eres,

D. ambigua,

D. neotheicola [

23],

D. hispaniae,

D. hungariae, D. celeris [

11],

D. nebulae,

D. novem,

D. ceranoidis, D

. serafiniae and

D. foeniculina [

21], can co-occur with

D. ampelina as latent or weak pathogens, and could cause significant symptoms as well. Moreover, a recent study by [

24], revealed that

D. eres and

D. foeniculina along with

D. ampelina, are associated with PCLS. In the same study, it was stated that the etiology of the disease should be reconsidered, since both species were found to be aggressive to grapevine as well. On the other hand,

D. ampelina has not been associated with canker diseases of grapevine in surveys conducted in Chinese vineyards, whilst

D. eres was the most common pathogen isolated from grapevine wood among others [

20,

25].The suggestion of the addition of

Diaporthe ampelina to the pathogens associated with the grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs) complex by [

23], intensified research regarding the role of other

Diaporthe species in grapevine trunk diseases. Regarding the occurrence of Diaporthe dieback in grapevine nurseries, and dissemination of the species related to the disease via the propagation material, only a few studies are available. More specifically, surveys conducted in Spain and Uruguay, showed that different

Diaporthe species could be isolated from nursery-produced vines [

26,

27], while a microbiome analysis based on next generation sequencing approaches from [

28] revealed the presence of

Diaporthe spp. in propagation material.

Historically, identification of

Diaporthe fungi to the species level, was mainly based on morphological and cultural characteristics, together with assumptions of host-specificity [

2]. According to recent findings which support that more than one species can co-occur in a single host or that a single species can infect several hosts, the inclusion of host-specificity studies in the proper species delineation may not be reliable [

11,

29]. Furthermore, morphological characteristics are not always informative, and molecular approaches such as the DNA sequence-based multi-locus phylogenies are required for species identification or novel species description [

30]. Various genetic loci and genes have been used in several taxonomic studies, which include the internal transcribed spacer (

ITS), the beta-tubulin 2 gene (

TUB2), the translation elongation factor 1-a (

TEF1), the histone 3 gene (

HIS3) and the calmodulin gene (

CAL) [

11,

20,

23,

25,

31].

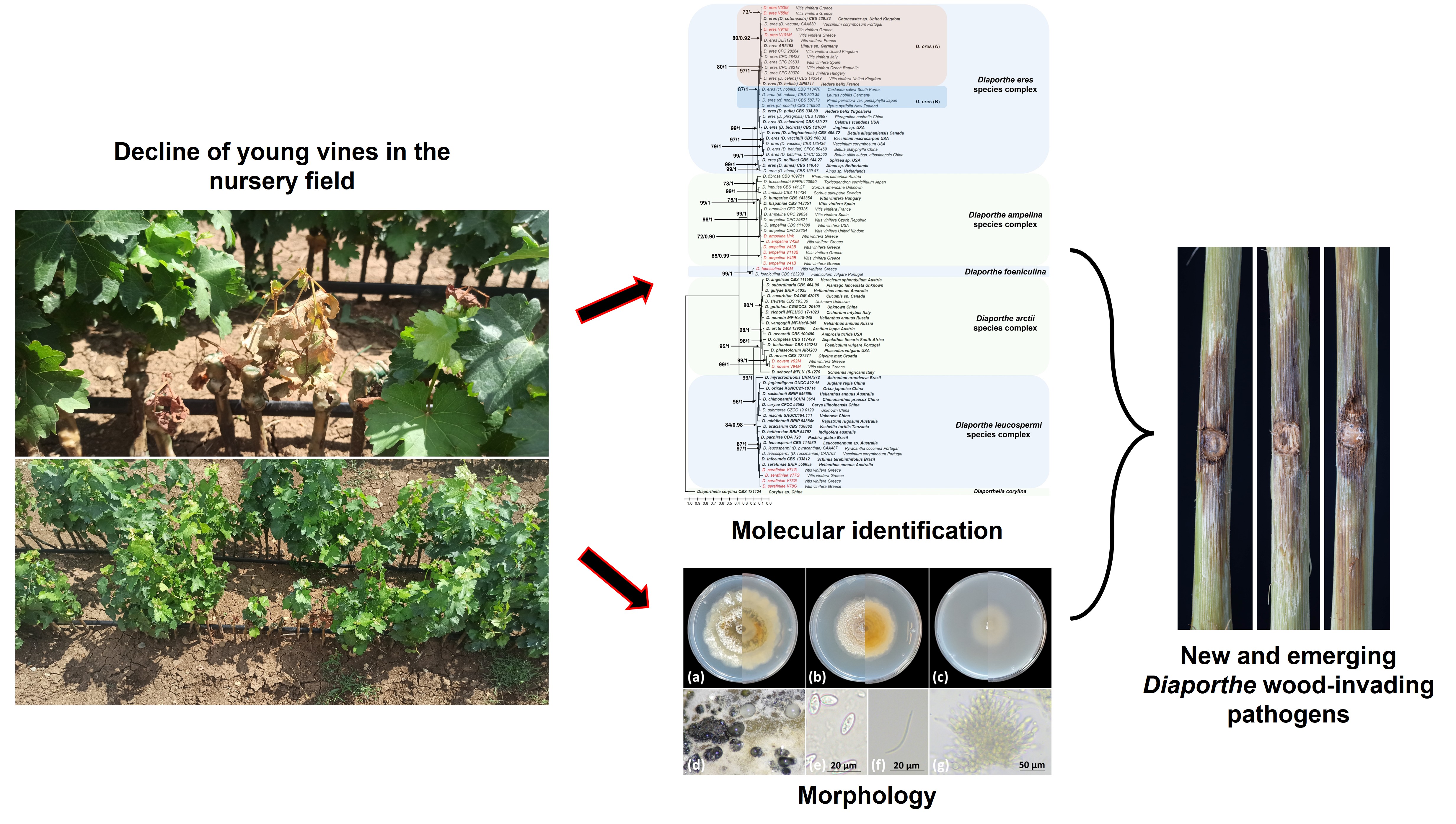

The main objective of this study was to investigate the diversity of Diaporthe species that are associated with grapevine propagation material infections, with a final aim to dissect into the role of each species in the development of Diaporthe dieback, an emerging grapevine trunk disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling of Grafted Vines and Fungal Isolation Procedure

Twenty (20), two-months old rooted grafted vines (cv. Agiorgitiko grafted onto rootstock Richter 110) showing decline symptoms including wilting (Figure S1a and S1b), leaf chlorosis, necrosis, reduced vigor (Figure S1c and S1d) and internal diffused brown wood discoloration (Figure S1e), were uprooted from a nursery field located in Nemea, Korinthos province, and transferred to the Laboratory of Plant Pathology at the Agricultural University of Athens, Greece. The whole root system was discarded, and vines were surface sterilized by whipping with 70% EtOH, washed with sterile distilled H2O and left under the laminar flow to dry. Afterwards, vines were debarked using a sterile scalpel and the first layers of plant tissue were removed until the appearance of the brown wood discoloration. Isolations were conducted from the discolored tissues and segments were taken from three sections: the basal end (crown), the first and second internode and the grafting union. Small fragments (approx. 2x2 mm) of symptomatic tissues were placed on Malt Extract Agar (MEA, Condalab, Spain) medium, supplemented with 50 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate to inhibit the growth of secondary microorganisms. From each vine, three MEA plates were used (one per vine section) and five fragments per section were placed in the medium. Plates were incubated at 25 oC for 5 to 10 days until the emergence of the fungal colonies. The developing fungal cultures were transferred to freshly made Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Condalab, Spain) plates, hyphal tipped, and incubated at 25 oC.

2.2. Fungal DNA Isolation and PCR Amplification

All fungal isolates were grown in Malt Extract Broth (MEB, Condalab, Spain) medium for several days depending on the growth rate of each isolate, at 25

oC in the dark. The mycelia from each isolate were harvested, lyophilized in a freeze dryer, and ground to a fine powder using a mortal and a pestle under the presence of liquid nitrogen. Total DNA was isolated from all isolates according to a CTAB-based protocol described by [

32] or a slightly modified protocol from [

33]. In this modification, a Tris-EDTA buffer containing 10 μg/ml of the enzyme RNAse A for RNA degradation was used for the resuspension of the pellet in the final extraction step. The concentration and the integrity of the isolated genomic DNA was assessed using a NanoDrop 2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel.

PCR amplifications were carried out using the KAPA Taq PCR Kit (Kit code – KK1014, KAPA Biosystems, South Africa) and were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the molecular identification of the isolates to the genus level, the rRNA ITS locus containing the 5.8S region was amplified using the primers designed by [

33]. Identification of

Diaporthe isolates to the species level was performed using additional appropriate molecular markers, based on the available literature for phylogeny in ascomycetes and

Diaporthe species, and included the beta-tubulin 2, the histone 3 and the translation elongation factor 1 alpha genes [

34,

35,

36]. The primers sets that were used and the PCR conditions for the amplification of each genetic locus are shown in

Table S1. PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel, stained for 15 minutes in 0.1% EtBr solution and the results were visualized under UV light.

2.3. Sequencing

PCR products were precipitated using an Ammonium Acetate (NH4CH3CO2)-based purification protocol. Briefly, NH4CH3CO2 (0.5 volumes of the PCR product) was added to the product, and the mixture was homogenized. Subsequently the mixture was centrifuged for 30 min at 13.000 rpm and 4 oC, and the supernatant was transferred to a new 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube. Then, 2.5 volumes of 100% EtOH were added, and the mixture was homogenized. After homogenization, a 30-min centrifugation in 13.000 rpm at 4 oC was carried out and the pellet was washed twice with 70% EtOH. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in TE Buffer (Tris-HCl and EDTA, pH=8) and stored at -20 oC.

Both strands of the PCR products were subjected to sequencing and the first 20-25 nucleotides from the 5’ and 3’ sequences were manually trimmed using the Benchling software (

https://www.benchling.com/). The two strands were aligned using the mafft algorithm [

37], and the consensus sequence was used for further analysis. The obtained sequences for each genetic locus were blasted against the GenBank nucleotide database (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), to identify the taxonomically closest species to be included in the downstream phylogenetic analyses.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of Diaporthe Isolates

The MEGAX software [

38] was used throughout the entire phylogenetic analysis. The sequences of each genetic locus obtained from this study along with sequences retrieved from the GenBank database (

Table S2) were aligned using the ClustalW method [

39], and subsequently they were concatenated. The optimum nucleotide substitution models for each single locus and the concatenated sequences were determined, and the General Time Reversible model [

40] was utilized for further analysis. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (5 categories (+

G, parameter = 0.5448), while the rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+

I], 28.73% sites). The initial tree for the heuristic search was constructed automatically under the Maximum Parsimony method and for the generation of the phylogenetic tree the Maximum-Likelihood statistical method (ML) was utilized with 1000 bootstrap replications.

To confirm the topology of the ML tree, a Bayesian inference analysis was conducted in BEAST v1.10.4 software [

41], using the same substitution model mentioned above (GTR + G + I). The Markov Chains Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling method was selected, starting with a random tree topology. The number of generations run by the MCMC algorithm was set at 10.000.000, and trees were sampled every 100 generations. The resulting consensus phylogenetic tree was rooted to

Diaporthella corylina CBS121124 (isolated from

Corylus sp., China), used as an outgroup. Phylogenetic trees were visualized and edited using the FigTree software (version 1.4.4,

http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

2.5. Morphological Characterization

One isolate from each

Diaporthe species was chosen for the morphological characterization. Four characteristics were considered, which included the growth rare (cm/day), the size of alpha- and beta-conidia, and the size of pycnidial conidiomata. Growth rates were calculated by placing a 3 mm agar plug taken from the margins of the active mycelium on the center of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA), Malt Extract Agar (MEA) and Oatmeal Agar (OA) plates, incubated at 25

oC for 7 days in the dark, and measurements were taken every day. Three (3) replicates per medium per species were used to calculate the mean growth rates. For the induction of pycnidia development, a 3 mm plug from each species was placed on Pine Needle Agar (PNA) medium [

42], and plates were incubated for 10 days at 25

oC and under a 12 h photoperiod. Three (3) PNA plates were used for the induction of pycnidia development. The mean size (length and width) of pycnidial conidiomata, alpha- and beta-conidia, were calculated by measuring 10 and 20 of each per

Diaporthe species per Petri dish in a Zeiss PrimoStar microscope, respectively, and images were captured using the Axiocam ERC 5s.

2.6. Pathogenicity Trials

Isolates used for the pathogenicity trials included two isolates of Diaporthe ampelina (V42B and V118B) isolated from different plants, two isolates of D. eres (V101M and V55M), also isolated from different grafted vines, and isolates V44M (D. foeniculina), V71G (D. serafiniae) and V92M (D. novem). The virulence dynamics of the different Diaporthe spp. was carried out by pathogenicity trials on 1-year old lignified grapevine canes of cv. Roditis, harvested from a 25-year-old commercial vineyard located in Fokis prefecture, Greece from apparently asymptomatic mature vines.

Canes were cut into pieces approximately 12 cm in length, each containing two nodes. A surface-disinfection was conducted by whipping the canes with 70% EtOH followed by air-drying under a flow-hood laminar. Afterwards, a 3x2 mm segment was discarded from the internode of each cane using a cork borer and a 3x2 mm plug from the edge of an actively growing colony on PDA was removed and inserted into the wound. Then, the wounds were covered with Parafilm (Amcor, Australia), while the upper node was covered with melted paraffin wax to maintain humidity and avoid secondary contaminations. Inoculated canes were placed upright in 500 ml glass beakers with the node on the underside of the canes submerged in tap water to maintain hydration. Water was replaced every two days and canes remained in greenhouse conditions for 21 days at 25 oC ± 1 oC and 12h photoperiod. At the end of the incubation period, canes were surface sterilized and left to dry as described above, debarked, and the necrotic lesion length was measured above and below the inoculation site. To fulfill Koch’s postulates, isolations were conducted on MEA supplemented with streptomycin sulfate (100 μg/ml) from both regions flanking the inoculation site for every isolate used in the pathogenicity experiment. The experiment was conducted three times, and a total of 15 plants were used for each isolate. Furthermore, 15 plants served as negative control, inoculated with a plain PDA plug.

2.7. Statistical Analyses

Data from the growth rate experiments were log-transformed and subjected to normality and homogeneity of variances using the Shapiro-Wilk and the Anderson-Darling statistical goodness-to-fit tests. As those conditions were met, subsequent analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s HSD test at α=0.05. Data from the pathogenicity trials were also subjected to normality test and homogeneity of variances. However, since these data did not follow a normal distribution, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was selected to determine if statistical differences occurred between the independent treatments. When significant, subsequent pairwise comparisons were performed using the Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjustment at α=0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Fungal Isolations

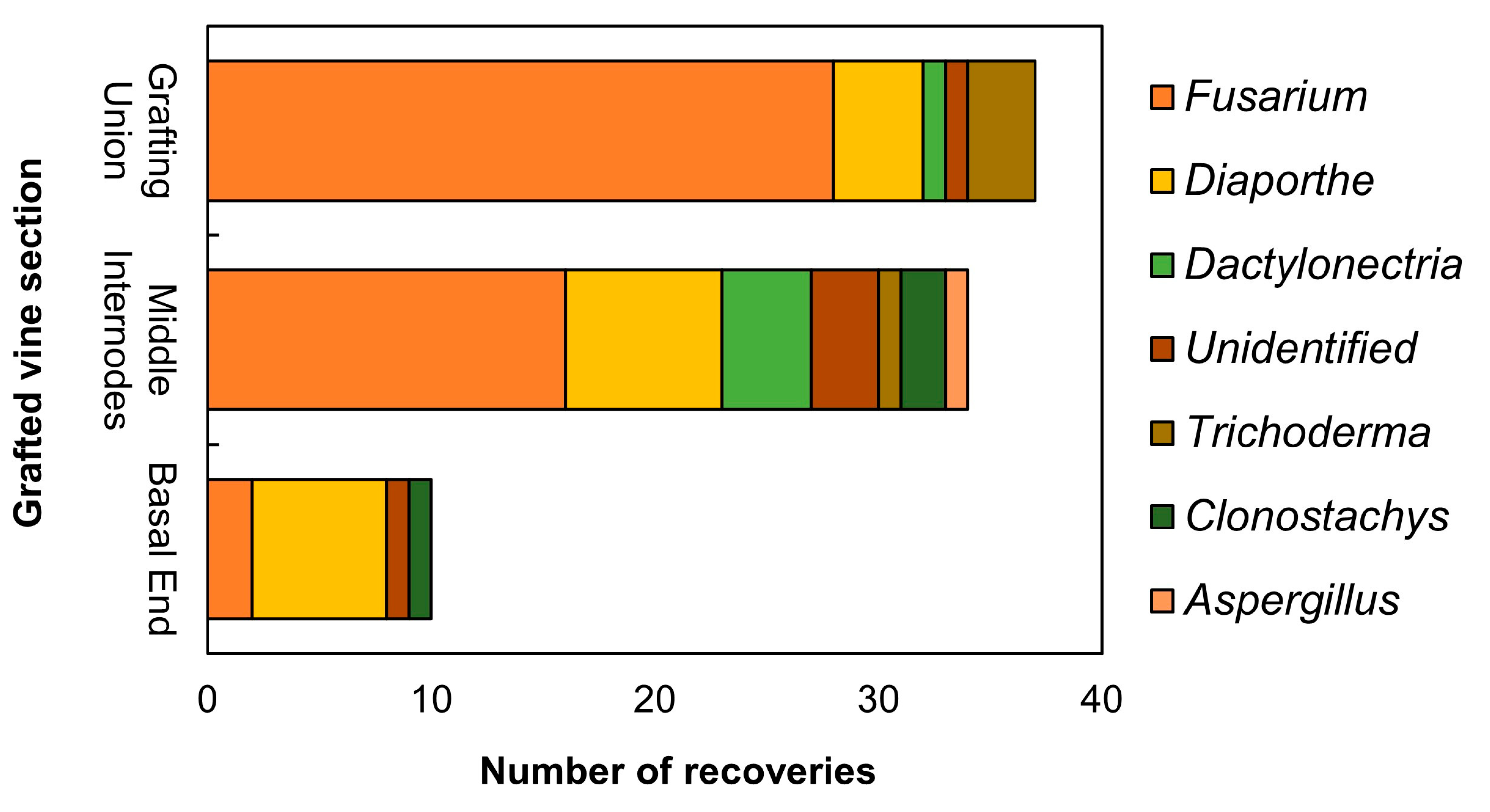

In total, 81 fungal isolates were recovered from the symptomatic grafted vines sampled from the nursery field. Based on the preliminary rRNA ITS region sequencing, the most prevalent fungal genus was Fusarium, accounting for 46 isolates (56.79%). Of those, two were isolated from the crown, sixteen from the internodes and 28 from the grafting union. Moreover, seventeen (17) isolates were assigned to the genus Diaporthe (20.98%). Those Diaporthe isolates were obtained from all vine sections analyzed. More specifically 7 out of 17 (41.18%) were isolated from the basal end, 8 (47.06%) from the first and the second internodes and 5 (29.41%) from the grafting union. In addition, 4 isolates were assigned to the genus Trichoderma (4.94%), 3 in the genus Clonostachys (3,70%), 5 in the genus Dactylonectria (6,17%), 1 in the genus Aspergillus (1,23%). Finally, 5 isolated (6,17%) were unidentified (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stacked bar chart showing the number of the different fungal genera recovered from 2-months old rooted grafted vines per vine section, as identified by the preliminary ITS region sequencing.

Figure 1.

Stacked bar chart showing the number of the different fungal genera recovered from 2-months old rooted grafted vines per vine section, as identified by the preliminary ITS region sequencing.

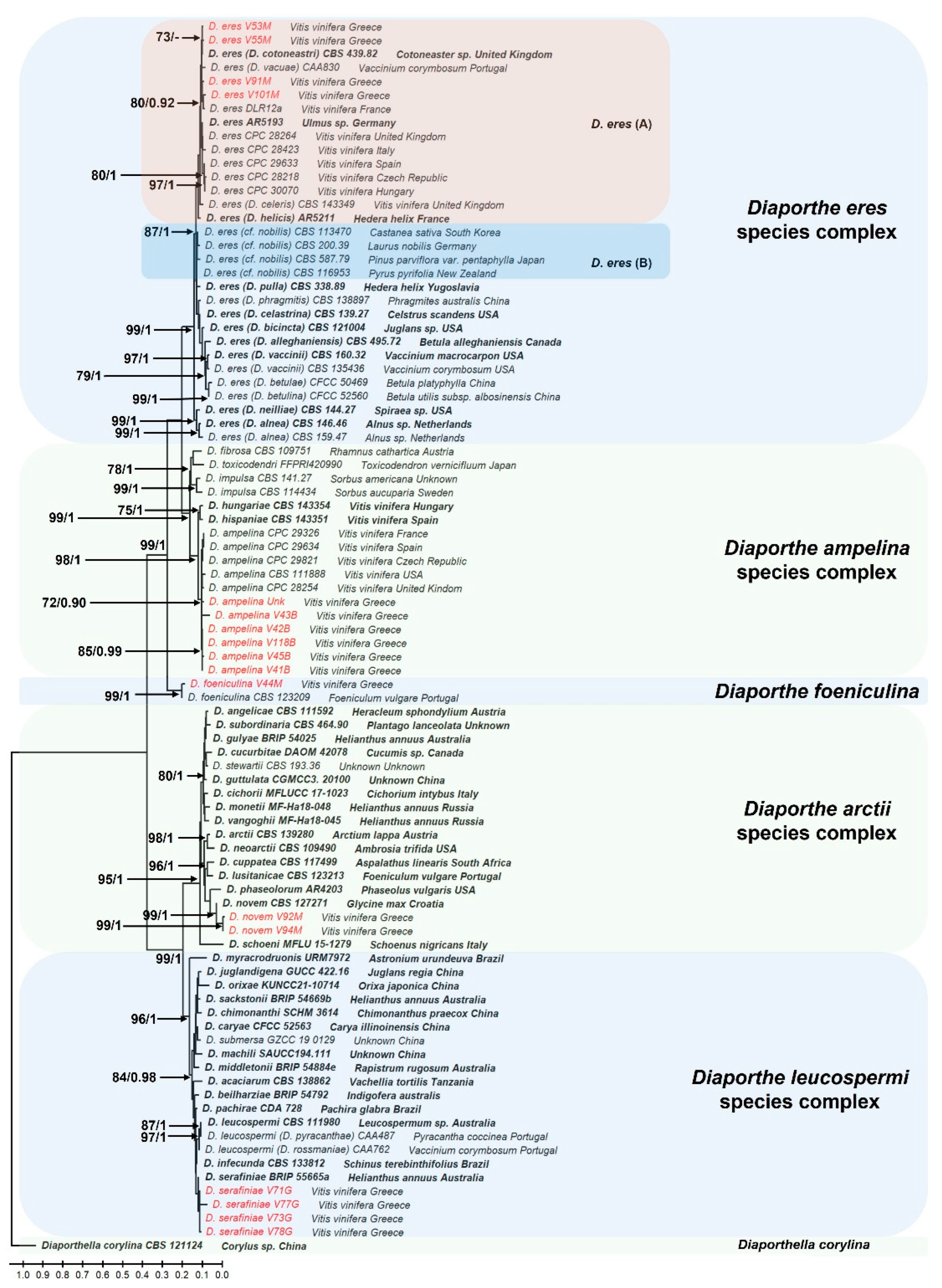

3.2. Phylogeny of Diaporthe

The phylogenetic trees constructed using both Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian inference analyses produced nearly identical topologies (data not shown). The analysis comprised 90 taxa including the outgroup species

Diapothella corylina CBS121124 (isolated from

Corylus sp., China). The final concatenated dataset of sequences from the four loci (

its, tub, his3 and

ef-1a) consisted of 4180 nucleotide positions (

its: 1318 bp,

tub: 1443 bp,

ef-1a: 726 bp and

his3: 501 bp), including gaps. The resulting phylogenetic tree revealed that fungi of the genus

Diaporthe isolated in this study were grouped into five well supported distinct clades. Six (6) isolates (V43B, UΝΚ, V118B, V42B, V45B and V41B) were placed within the

D. ampelina species complex [

43] and clustered with the closely related

D. ampelina reference strains (

Figure 2). The generation of the clade was supported by a high bootstrap value and posterior probability (99 and 0.98, respectively), confirming their identity as

D. ampelina. Four isolates, V53M, V55M, V101M and V91M, were grouped within the

D. eres species complex and clustered with the reference strains AR5193 (isolated from

Ulmus sp. in Germany) and DLR12 (isolated from

Vitis vinifera in France), as well as with other synonymous to

D. eres strains, like

D. cotoneastri,

D. vacuae,

D. celeris and

D. helicis. All the isolates in this group fell within

D. eres (A) and were distinct from the

D. eres (B) clade previously known as

Diaporthe cf.

nobilis/

Phomopsis fukushii complex. This clustering was supported by a bootstrap value of 80 and posterior probability of 0.92. Isolates V71G, V73G and V78G fell into the

D. leucospermi species complex and were most closely related to the species

D. serafiniae, although with a lower bootstrap value and posterior probabilities (70 and 0.80, respectively). One isolate (V44M) belonged to the species

D. foeniculina (bootstrap value of 99 and probability of 1), while isolates V94M and V92M were clustered with the species

D. novem and fell into the

D. arctii species complex, supported by a bootstrap value of 99 and a posterior probability of 1 (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Diaporthe phylogenetic tree, inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and General Time Reversible model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-27478.73) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa are clustered together is shown next to the branches, as well as the posterior probabilities calculated with the Bayesian Inference analysis. Only bootstrap values > 70 and probabilities > 0.9 are shown in the branches. The initial tree for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the Maximum Parsimony method. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. This analysis involved 90 nucleotide sequences with the outgroup species designated to Diaporthella corylina CBS121124. Taxa in red represent the fungal species isolated in this study while taxa in bold represent the ex-type cultures. There were a total of 4180 positions in the final dataset, including gaps.

Figure 2.

The Diaporthe phylogenetic tree, inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and General Time Reversible model. The tree with the highest log likelihood (-27478.73) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa are clustered together is shown next to the branches, as well as the posterior probabilities calculated with the Bayesian Inference analysis. Only bootstrap values > 70 and probabilities > 0.9 are shown in the branches. The initial tree for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying the Maximum Parsimony method. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of nucleotide substitutions per site. This analysis involved 90 nucleotide sequences with the outgroup species designated to Diaporthella corylina CBS121124. Taxa in red represent the fungal species isolated in this study while taxa in bold represent the ex-type cultures. There were a total of 4180 positions in the final dataset, including gaps.

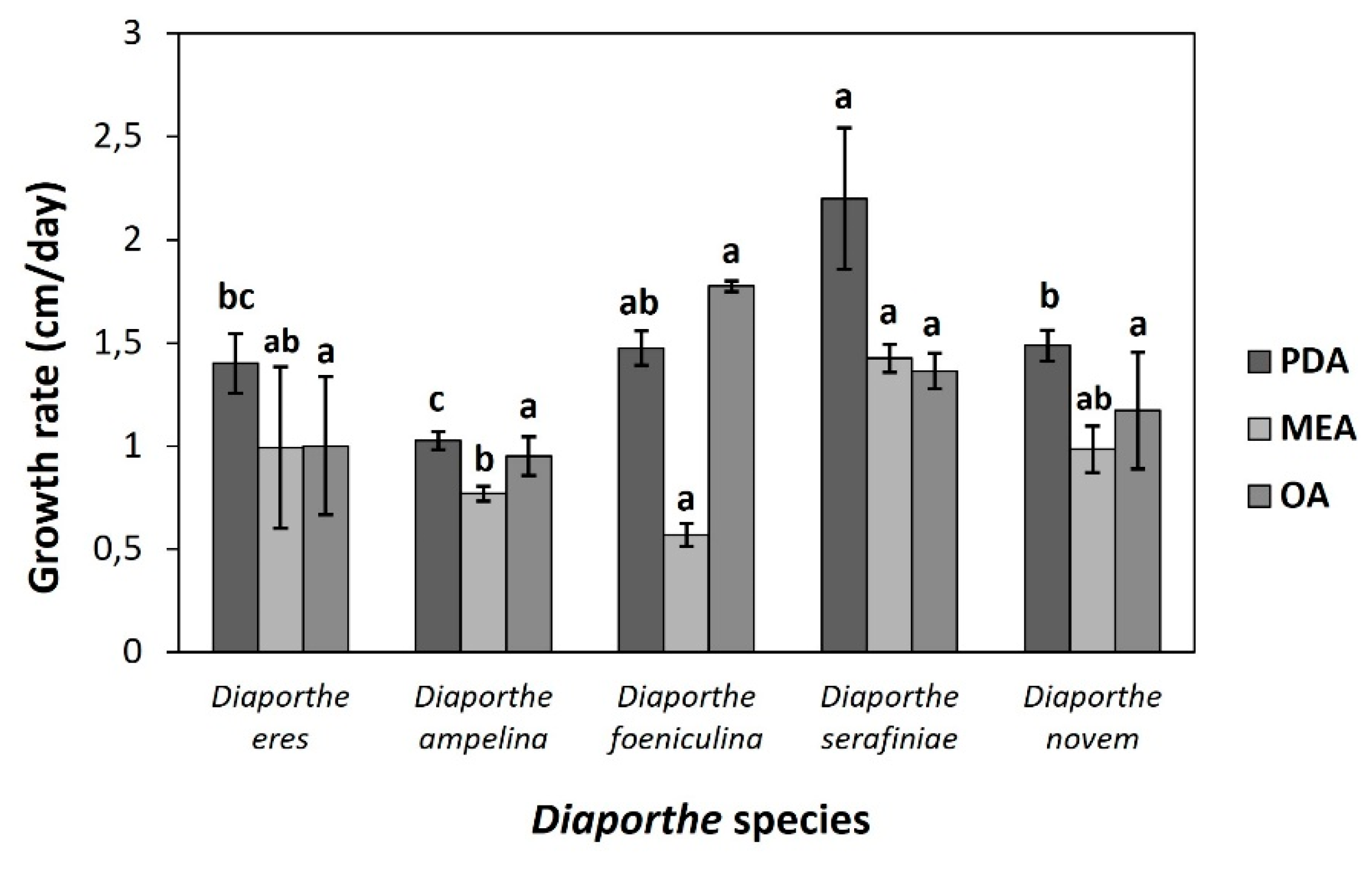

3.3. Morphological Characterization

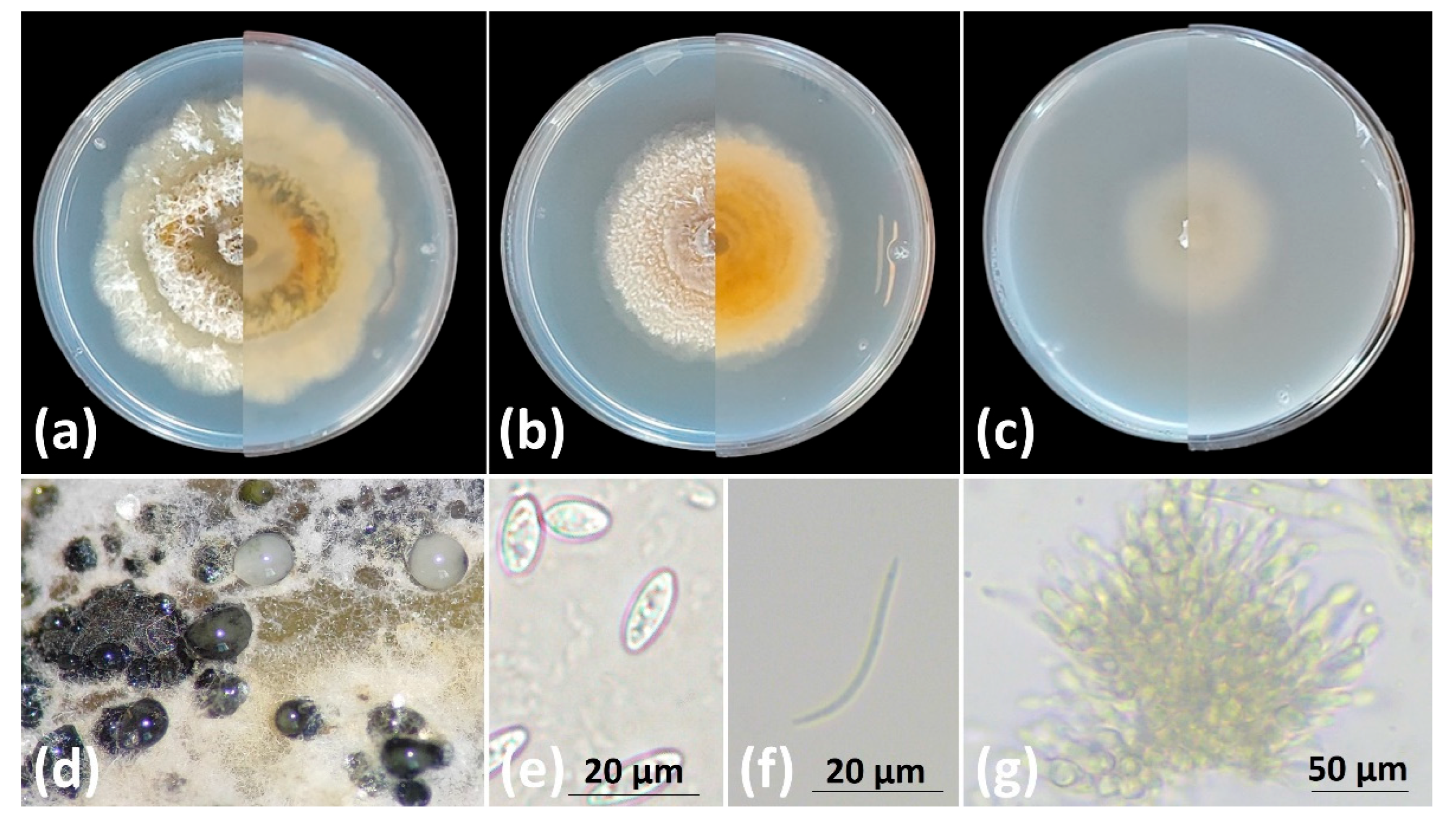

Growth rates of the five Diaporthe species were evaluated on three artificial media, PDA, MEA, and OA. Among the species, D. serafiniae exhibited the highest growth rate, particularly on PDA (2.20 ± 0.34 cm/day), while D. ampelina showed the slowest growth, especially on OA medium (0.95 ± 0.09 cm/day). D. foeniculina displayed the most variable growth, with high rates on OA (1.78 ± 0.02 cm/day) but limited growth on MEA (0.57 ± 0.06 cm/day). D. novem and D. eres demonstrated moderate to consistent growth across all media (Figure 3). Moreover, D. eres and D. novem had the smallest alpha conidia, while D. ampelina and D. serafiniae had the largest. The size of beta conidia were approximately the same size across all examined species, ranging from 22.64 ± 0.96 in D. novem to 25.80 ± 0.72 in D. foeniculina. Interestingly, no beta conidia were observed in D. serafiniae. The size of alpha- and beta-conidia, as well as the size of the pycnidial conidiomata are summarized in Table 1. Figure 4 depicts the morphological characteristics of D. ampelina, while the morphology of D. eres, D. foeniculina, D. serafiniae and D. novem are shown in the respective Supplementary Figures S2, 2, 4, and 5.

Figure 3.

Grouped histogram depicting the growth rates (cm/day) of the five Diaporthe species across the three media tested (PDA, MEA and OA). Bars above each histogram represent the standard error of the mean. Different letters indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the different groups in α=0.05, according to Tukey’s HSD test. PDA: potato dextrose agar, MEA: malt extract agar, OA: oatmeal agar.

Figure 3.

Grouped histogram depicting the growth rates (cm/day) of the five Diaporthe species across the three media tested (PDA, MEA and OA). Bars above each histogram represent the standard error of the mean. Different letters indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the different groups in α=0.05, according to Tukey’s HSD test. PDA: potato dextrose agar, MEA: malt extract agar, OA: oatmeal agar.

Table 1.

Morphological characterization of Diaporthe species isolated in this study in terms of alpha- and beta- conidia size, and the size of pycnidial conidiomata. Values next to the ± symbol represent the standard error of the mean.

Table 1.

Morphological characterization of Diaporthe species isolated in this study in terms of alpha- and beta- conidia size, and the size of pycnidial conidiomata. Values next to the ± symbol represent the standard error of the mean.

| Species |

Morphological characteristics (μm) |

| alpha-conidia |

beta-conidia |

Conidiomata |

| Diaporthe ampelina |

(9,18 ± 0,40),

(3,34 ± 0,10) |

(24,26 ± 1,48),

(1,72 ± 0,09) |

273 ± 11,78 |

| Diaporthe eres |

(6,19 ± 0,31),

(2,20 ± 0,07) |

(24,18 ± 0,67),

(1,60 ± 0,06) |

256,25 ± 22,56 |

| Diaporthe foeniculina |

(7,66 ± 0,19),

(2,69 ± 0,12) |

(25,80 ± 0,72),

(1,58 ± 0,72) |

474,98 ± 28,86 |

|

Diaportheserafiniae

|

(13,70 ± 0,48),

(4,94 ± 0,16) |

not observed |

244,53 ± 15,20 |

| Diaporthe novem |

(6,92 ± 0,16), (2,44± 0,05) |

(22,64 ± 0,96), (1,65 ± 0,05) |

391,57 ± 43,72 |

Figure 4.

Diaporthe ampelina cultures in plates with (a) PDA, (b) MEA, (c) OA, (left half: front view, right half: rear view); (d) oozing pycnidia in PDA, (e) alpha- conidia, (f) beta-conidia and (g) conidiomata. Scale bars: (e) and (f) 20 μm and (g) 100 μm.

Figure 4.

Diaporthe ampelina cultures in plates with (a) PDA, (b) MEA, (c) OA, (left half: front view, right half: rear view); (d) oozing pycnidia in PDA, (e) alpha- conidia, (f) beta-conidia and (g) conidiomata. Scale bars: (e) and (f) 20 μm and (g) 100 μm.

3.4. Pathogenicity Trials

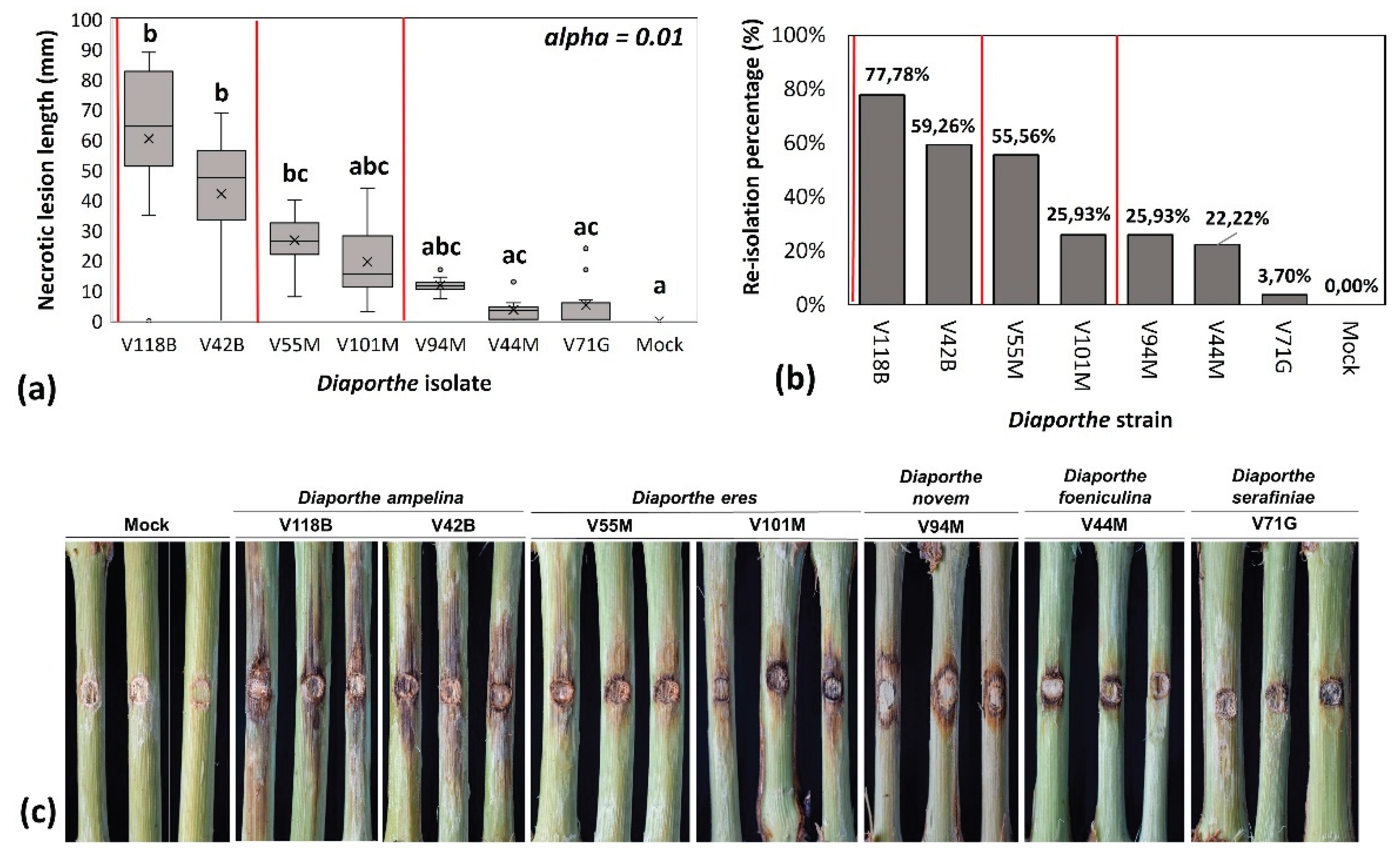

The pathogenic potential of the five Diaporthe species was assessed by inoculating detached lignified grapevine canes and measuring the resulting necrotic lesion lengths 21 days post inoculation. Among the species tested, only D. ampelina and D. eres induced significant necrosis. In contrast, D. foeniculina, D. serafiniae, and D. novem caused either no symptoms or mild, localized lesions which only occurred in close proximity to the inoculation site. D. ampelina demonstrated the highest virulence, with mean lesion lengths of 42.1 mm for strain V42B, and 60.4 mm for strain V118B; both significantly longer compared to the mock-treated plants (p-value < 0.01). The necrosis induced by the two strains did not differ significantly from each other (p-value > 0.01). D. eres strains V55M and V101M also produced considerable necrotic lesions, with mean lengths of 26.8 mm and 19.6 mm, respectively. These values were lower than those caused by D. ampelina but still distinct from the control plants (p-value < 0.01). In contrast, strains of D. novem, D. foeniculina and D. serafiniae were considered mildly pathogenic or non-pathogenic to grapevine, producing average lesion lengths of 11.75 mm, 5.2 mm, 3.7 mm, respectively (Figure 5a and 5c). A more detailed assessment of the symptoms revealed that unlike D. ampelina and D. eres, lesions caused by D. novem were limited to the phloem and were not observed in the xylem tissues, as inspections at the xylem level did not show any discoloration. The lesion lengths induced by the different species are summarized in Table 2.

Koch’s postulates were fulfilled for all species by re-isolation of the fungi and subsequent identification using morphological traits compared to the original isolate. Re-isolation rates for D. ampelina ranged from 59.26% (V42B) to 77.78% (V118B), and for D. eres from 25.93% (V101M) to 55.56% (V55M). Recovery of D. serafiniae and D. foeniculina occurred at lower frequencies; 3.7% and 22.22%, respectively, while D. novem was re-isolated from 25.93% of the inoculated canes (Figure 5b). No fungus was recovered from the mock-treated plants. Taking into consideration the low to negligible virulence and their recovery primarily from asymptomatic tissues, D. serafiniae, D. foeniculina, were classified as opportunistic pathogens rather than primary pathogens of grapevine. On the other hand, D. novem, which induced longer necrotic lesion compared to the other two species, was classified as moderately pathogenic to grapevine.

Figure 5.

(a) Box and Whiskers plot showing the necrotic lesion length range induced by the different Diaporthe species above and below the inoculation sites, (b) re-isolation rates of the different species one week post incubation of MEA plates at 25 oC in the dark, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. (c) images captured 21 days post inoculation with the different species, representing the data from sub-figure (a). In the sub-figures the discoloration levels and the recovery rates from the highest to the lowest are depicted. Different letters indicate the statistical difference between the group medians at α=0.01 according to the non-parametric Dunn’s test. V42B and V118B: D. ampelina, V55M and V101M: D. eres, V94M: D. novem, V44M: D. foeniculina and V71G: D. serafiniae.

Figure 5.

(a) Box and Whiskers plot showing the necrotic lesion length range induced by the different Diaporthe species above and below the inoculation sites, (b) re-isolation rates of the different species one week post incubation of MEA plates at 25 oC in the dark, fulfilling Koch’s postulates. (c) images captured 21 days post inoculation with the different species, representing the data from sub-figure (a). In the sub-figures the discoloration levels and the recovery rates from the highest to the lowest are depicted. Different letters indicate the statistical difference between the group medians at α=0.01 according to the non-parametric Dunn’s test. V42B and V118B: D. ampelina, V55M and V101M: D. eres, V94M: D. novem, V44M: D. foeniculina and V71G: D. serafiniae.

Table 2.

Pathogenicity assessment of seven Diaporthe isolates on detached grapevine canes. Mean lesion lengths (±SE) were measured 21 days post-inoculation, and recovery percentages reflect successful re-isolation of the inoculated fungi. Strains of D. ampelina and D. eres induced significantly longer necrotic lesions and showed higher recovery rates, indicating strong pathogenic potential. In contrast, D. novem, D. foeniculina, and D. serafiniae exhibited limited virulence and lower re-isolation frequencies, consistent with their classification as moderate or opportunistic pathogens. Different letters denote statistical groupings based on Dunn’s test in α=< 0.01).

Table 2.

Pathogenicity assessment of seven Diaporthe isolates on detached grapevine canes. Mean lesion lengths (±SE) were measured 21 days post-inoculation, and recovery percentages reflect successful re-isolation of the inoculated fungi. Strains of D. ampelina and D. eres induced significantly longer necrotic lesions and showed higher recovery rates, indicating strong pathogenic potential. In contrast, D. novem, D. foeniculina, and D. serafiniae exhibited limited virulence and lower re-isolation frequencies, consistent with their classification as moderate or opportunistic pathogens. Different letters denote statistical groupings based on Dunn’s test in α=< 0.01).

| Species |

Isolate |

Mean lesion length (mm) |

Recovery percentage (%) |

| Diaporthe ampelina |

V118B |

60.40 ± 8.81 b

|

77.78% |

| V42B |

42.10 ± 6.72 b

|

59.26% |

| Diaporthe eres |

V55M |

26.80 ± 3.0 bc

|

55.56% |

| V101M |

19.60 ± 4.03 abc

|

25.93% |

| Diaporthe novem |

V94M |

11.75 ± 0.86 abc

|

25.93% |

| Diaporthe foeniculina |

V44M |

5.20 ± 2.69 ac

|

22.22% |

| Diaporthe serafiniae |

V71G |

3.70 ± 1.23 ac

|

3.7% |

4. Discussion

Grapevine trunk diseases (GTDs) are considered one of the major plagues in viticulture, affecting the grapevine industry and the wine sector worldwide [

44,

45]. In the last two decades, several trunk diseases have been extensively studied and described, including the well-known esca proper syndrome (

Phaeomoniella chlamydospora,

Phaeoacremonium minimum,

Fomitiporia mediterranea), Botryosphaeria (Botryosphaeriaceae species) and Eutypa dieback (

Eutypa lata) affecting mature vines, and Petri disease (

Pa. chlamydospora,

Pm. minimum and

Cadophora luteo-olivacea) along with black foot disease (

Ilyonectria,

Dactylonectria) associated with the young grapevine decline syndrome and propagation material infections [

44]. Since 2013,

Diaporthe ampelina (former

Phomopsis viticola), a fungus implicated in Phomopsis cane and leaf spot disease in grapevines, was introduced in the trunk diseases complex due to its ability to cause cankers, necrotic lesions, discoloration and dieback of cordons and canes [

23]. As a result, a number of surveys have been conducted associated with the

Diaporthe species responsible for grapevine trunk diseases in a few parts of the world, including China [

20,

25], a big part of Europe [

11], South Africa [

21] and North America [

46]. In the current study, a baseline survey carried out in a grapevine nursery located in Nemea, the main viticultural region in Greece, revealed that grafted vines grown for two months in the nursery field, were infected by more than one

Diaporthe species simultaneously. Based on multi-loci sequencing, followed by an extensive phylogenetic analysis combining the maximum likelihood and the Bayesian inference, we identified five phylogenetically distinct

Diaporthe species, namely

D. ampelina,

D. eres,

D. foeniculina,

D. serafiniae and

D. novem, all isolated from symptomatic nursery young vines, along with other endophytic fungi. Among the

Diaporthe species isolated in this study,

D. eres and

D. foeniculina have been reported to infect peach trees [

47] and citrus/mango trees in Greece [

48,

49], respectively. However, this is their first record in grapevines in Greece. In addition to that, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first record of

D. serafiniae and

D. novem in grapevines in Greece. Although in the present study the number of isolates obtained was limited, the analysis showed that

D. ampelina was the most frequently isolated species, an observation that is in accordance with the available literature [

23].

Identification of

Diaporthe species heavily relies on multi-locus sequence analysis in addition to the morphological characteristics [

11]. Indeed, the proper identification of the species isolated in this study was not feasible by analyzing each locus separately (

its,

ef-1a,

tub2 and

his3), as closely related species share a high degree of homology in the conserved genes or regions analyzed. Furthermore, the size of the alpha- and beta- conidia, as well as the size of the pycnidial conidiomata are not always informative in species identification and description, as these characteristics overlap even between highly distinct species [

29]. In our study, the size of both conidia types in

D. eres,

D. novem and

D. foeniculina were very similar, hence, these morphological traits should always be combined with a phylogeny-based approach when identifying

Diaporthe spp [

50]. This is in accordance with other studies, which emphasize the importance of the proper molecular characterization of

Diaporthe species, in order to better understand their epidemiology and to develop efficient control strategies for different pathogens in grapevine [

10,

11,

20,

25,

29,

30]. As described by [

43] in their recent study regarding the species boundaries and the species complexes in the genus

Diaporthe, only taxa from the appropriate

Diaporthe section or species complex should be including in the phylogenetic analysis. In our analysis, these suggestions were applied for accurate identification to the species level. Indeed, the identification of all species in this study were supported by high bootstrap values and posterior probabilities.

This study also aimed to explore the dynamics of each species in symptom expression and disease development in grapevine. Greenhouse pathogenicity trials carried out in detached one-year old lignified canes revealed that among the five species tested, only

D. ampelina and

D. eres exhibited high virulence. For each of the two species, two different isolates from different individuals were tested. In the case of

D. ampelina, canes inoculated with isolate V118B exhibited necrotic lesions of 60.4 mm on average, while isolate V42B induced necrosis of 42.1 in length. Although not significantly different, isolate V42B caused lower necrosis compared to isolated V118B. This difference might be attributed to an intra-specific variation in virulence, an assumption also made by other researchers where different

D. ampelina isolates displayed varying pathogenicity [

24,

51,

52]. Of course, these observations need to be further validated by testing a large number of isolates, since genetic characteristics of each strain or the genotype of the host plant may play a role in this variation. Nonetheless, we report here that

D. ampelina emerged as the most aggressive species, strengthening the findings of earlier data [

21,

53]. In addition, our work confirmed the pathogenic potential of

D. eres in grapevines, observations that corroborate the findings of previous research [

20,

24,

27]. The two isolates tested, induced significant necrosis, but to a lower extent compared to

D. ampelina, which comes to an agreement with the available literature [

27,

46]. Within the constraints of our experimentation, the abovementioned species emerged as the most aggressive ones, consistent with reports from previous research in other viticultural regions [

23,

25,

46].

Although earlier studies have identified

D. novem as a potential grapevine pathogen [

21], the role in disease development is not clear. In this study, canes artificially inoculated with

D. novem, displayed minor discoloration, which was limited to the phloem tissues. The lesion length induced by this species was not significantly different from this of isolate V55M of

D. eres, but also, it did not differ significantly with the control plants. Nevertheless,

D. novem was re-isolated from the 25.93% of the inoculated canes, supporting its mild virulence in grapevine. These findings align with those of [

21] who also assessed the pathogenicity of

D. novem in grapevine among other species. In their work, they showed that although

D. novem formed moderate lesions, it was re-isolated in a significant percentage in both experiments that they conducted. According to this, they concluded that

D. novem can be considered a pathogen of grapevine [

21]. Furthermore, and to the best of our knowledge,

D. serafiniae has been found once in South Africa [

21]. This study assessed the virulence of three different isolates, and observed a variation in pathogenicity, probably due to the different lignin content of the plant material used. As a result, they concluded that some isolates of

D. serafiniae might act as potential pathogens of grapevine, and some were considered as weak pathogens [

21]. In our study,

D. serafiniae induced the shortest necrotic lesions (3.7 mm), thus it was classified as an opportunistic pathogen. Similar results were obtained in canes inoculated with

D. foeniculina, where the necrotic lesions did not differ significantly with the control plants. Besides their low virulence, both fungi were successfully re-isolated from the inoculated canes, which means that they are able to colonize grapevine. Based on that, our study suggests that similarly to

D. serafiniae,

D. foeniculina acts as a weak or opportunistic pathogen. Our observation that

D. foeniculina caused minimal lesions mirror the results of those obtained in Croatia [

54], California [

23] and Uruguay [

27], reinforcing its likely role as a weak pathogen in grapevine. Recently, this species was isolated in Cyprus from cordons and spurs, displaying severe dieback symptoms and internal wood discoloration [

55]. While in this study the fungus was able to induce necrosis in rooted cuttings, this occurred seven months post inoculation, which might indicate that longer incubation periods might produce different outcomes.

The role of

D. novem, D. foeniculina and

D. serafiniae in disease expression in the field remains uncertain, as they exhibit negligible virulence in grapevine under our experimental conditions. Still, it is not well understood what the contributing factors are that drive the shift of a fungus from an endophytic to a pathogenic phase. It is believed that the nursery practices associated with the production of propagation material induce plant’s stress, making it vulnerable to latent pathogen attack [

56]. Also, climatic conditions such as increased temperatures in mid-summer documented in Greece, may lead to water deficiency in the nursery field, and as a result, to increased susceptibility of the grafted vines to wood-invading pathogens. These abiotic stresses may alter plant’s biochemical, physiological and ecological procedures and suppress plant’s immunity system, making it vulnerable to opportunistic pathogens. Also, they facilitate the generation of new, more virulent and better adapted pathogen strains [

57,

58]. Furthermore, the elevated temperatures may decrease pathogens’ overwintering and incubation period, leading to increased inoculum in the field over a growing season, and thus in higher disease pressure [

57]. Another factor that might play a role in plants’ stress is the microbial imbalances in the propagation material. In this study, approximately 56% and 6% of the isolated fungi from grafted vines were assigned to the genus

Fusarium and

Dactylonectria. Recent studies have shown that the abundance of the

Fusarium genus representatives is higher in symptomatic vines compared to asymptomatic ones [

59]. In this particular study, it was stated that co-inoculation of vines with

Fusarium spp. and

Dactylonectria macrodidyma resulted in higher disease severity, compared to the single inoculations. This might also be the case here, where the microbial imbalances in rooted grafted vines could influence the biotic stress of the plants and promote subsequent opportunistic infections by

Diaporthe species.