Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Method

Participants

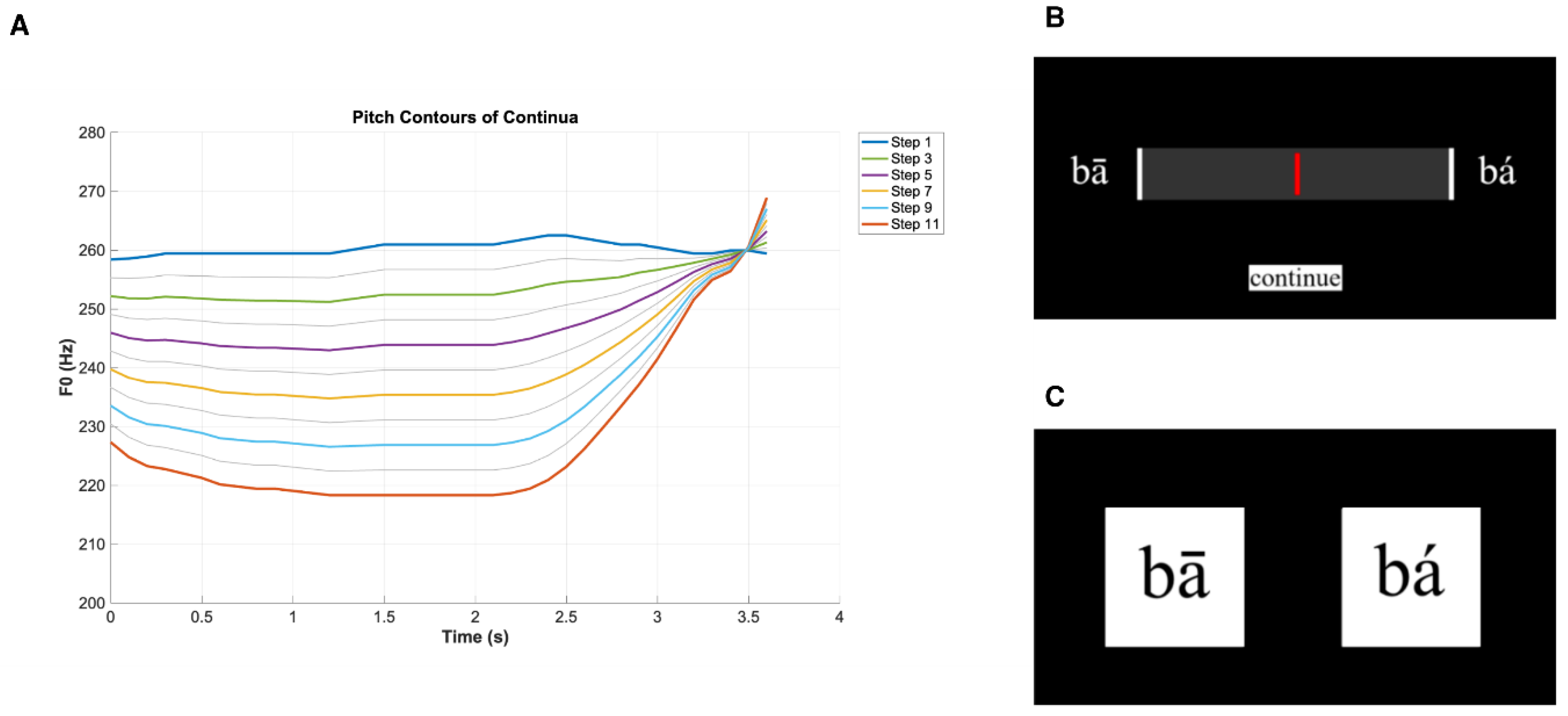

Stimuli

Procedure

Results

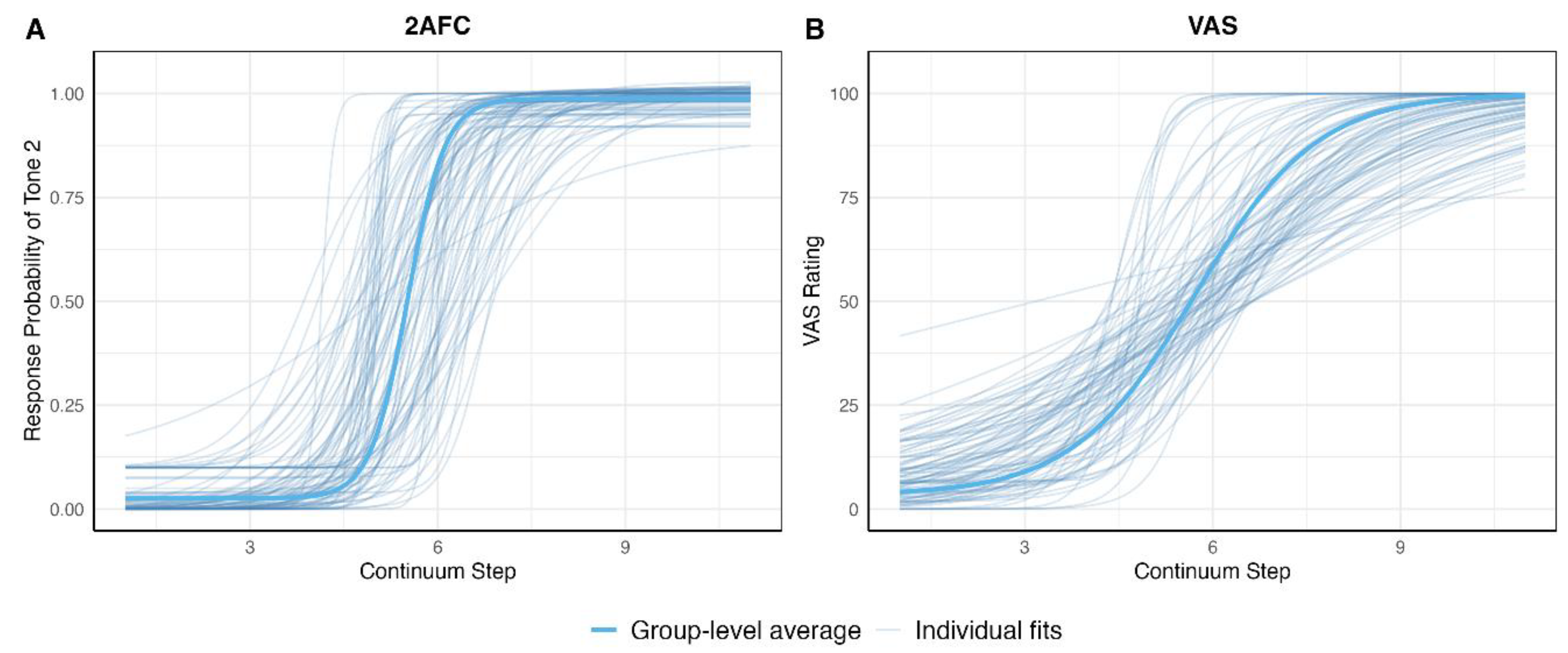

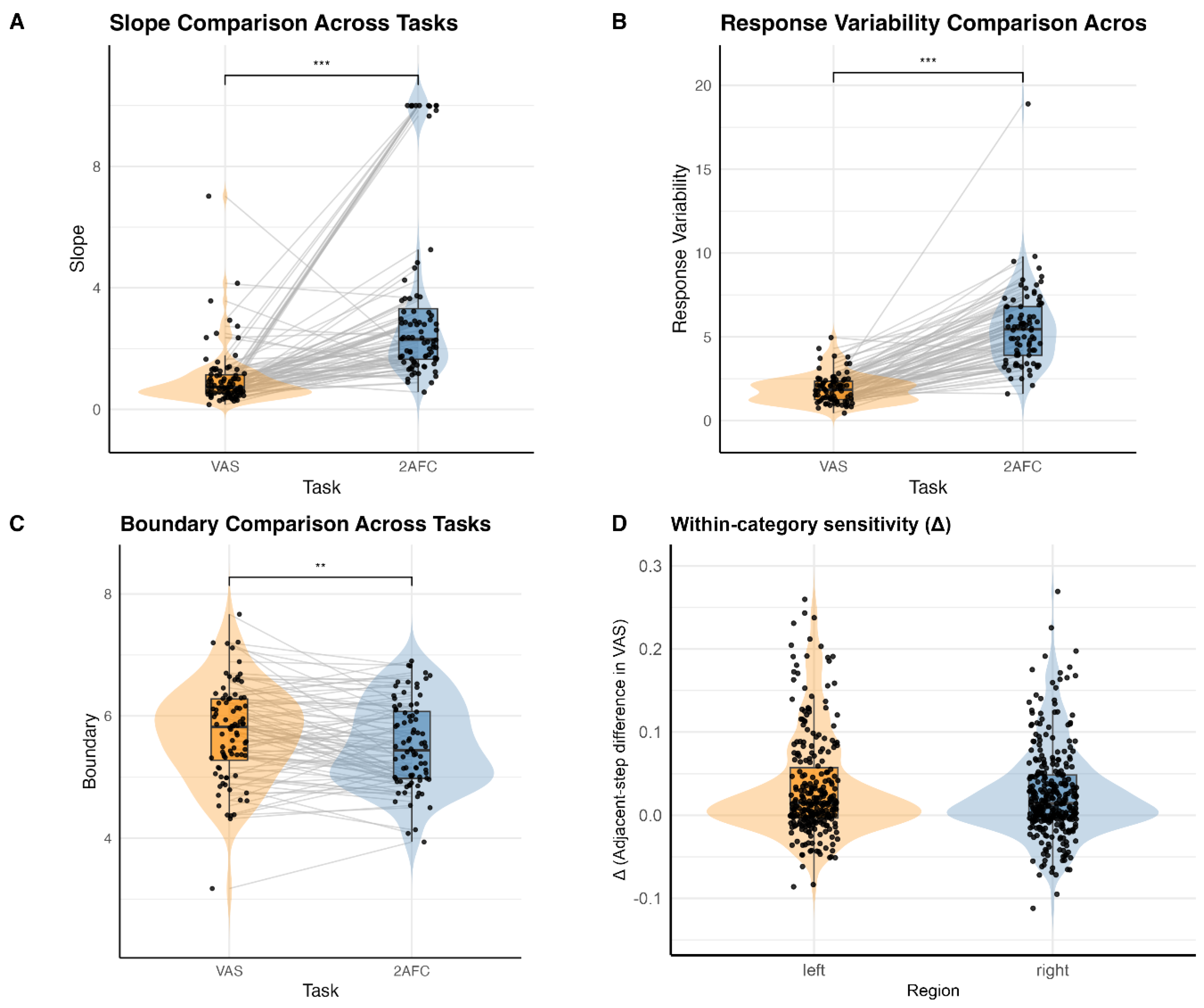

Model Performance and Overall Task Comparisons

Within-Category Sensitivity

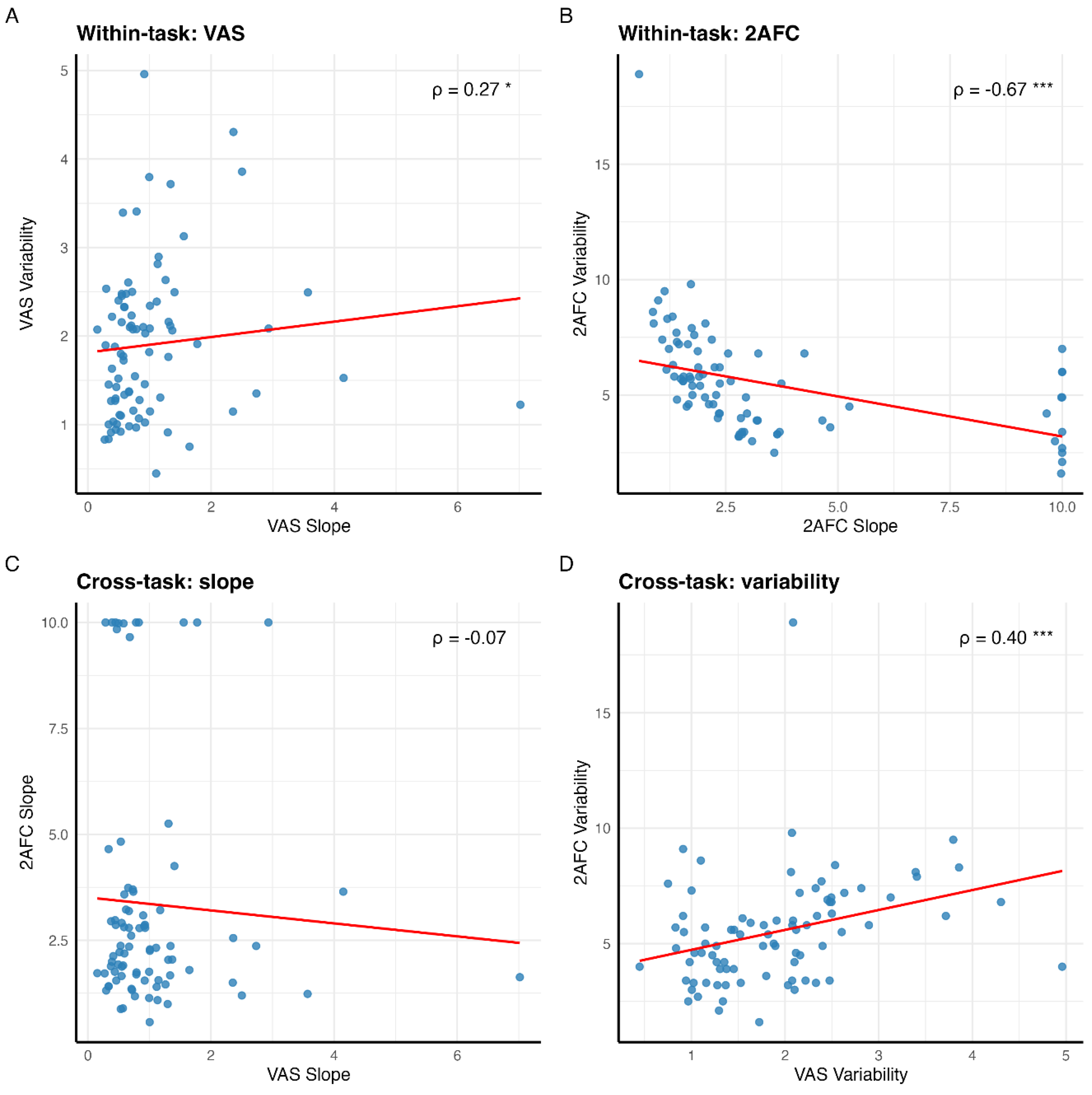

Cross-Measure Correlations

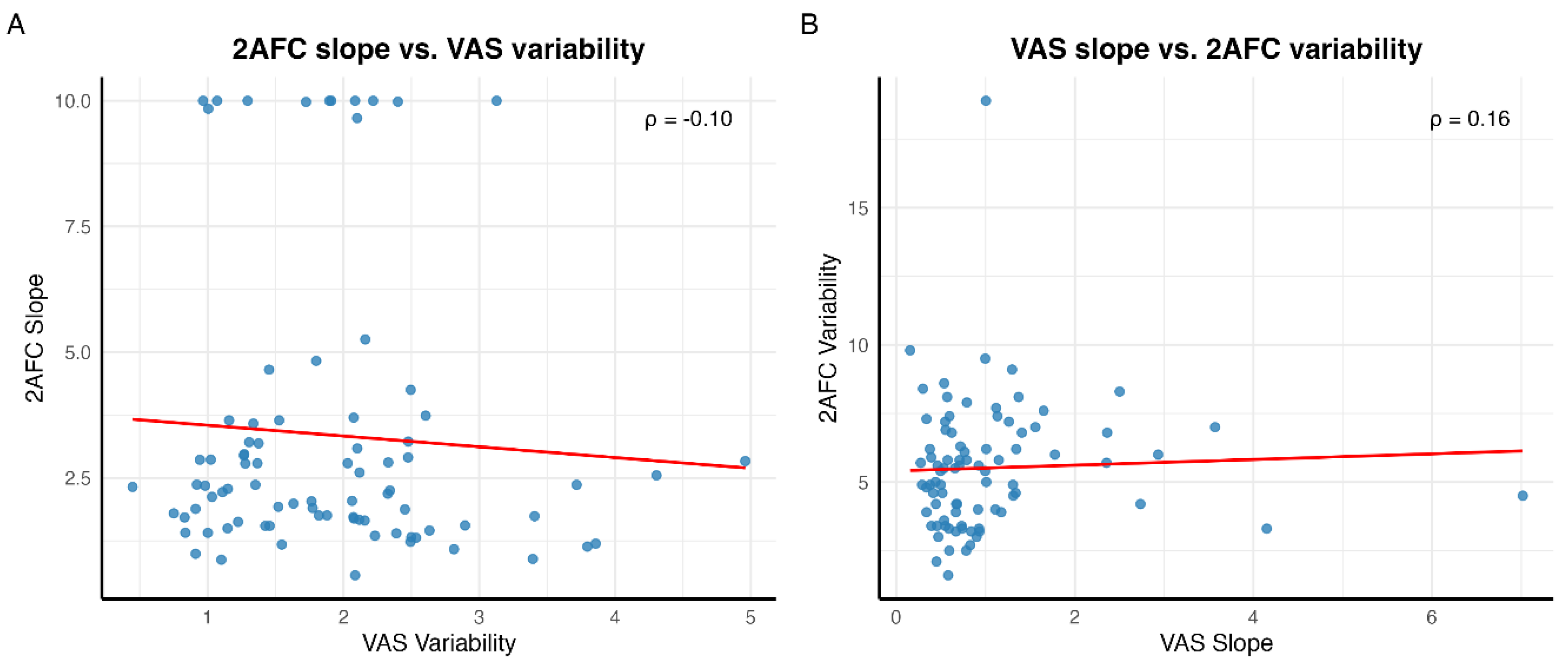

Individual Differences in Slope Steepness and Response Variability

Discussion

Gradient Encoding Within Tone Categories

Gradiency and Response Variability as Independent Perceptual Dimensions

Methodological Advantages of Continuous Response Paradigms

Limitations and Future Directions

Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abramson, A. S. (1975). Thai tones as a reference system (Haskins Laboratories: Status Report on Speech Research, pp. 127–136). Haskins Laboratories.

- Abramson, A. S. (1977). Noncategorical perception of tone categories in Thai. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 61(S1), S66–S66. [CrossRef]

- Andruski, J. E., Blumstein, S. E., & Burton, M. (1994). The effect of subphonetic differences on lexical access. Cognition, 52(3), 163–187. [CrossRef]

- Apfelbaum, K. S., Kutlu, E., McMurray, B., & Kapnoula, E. C. (2022). Don’t force it! Gradient speech categorization calls for continuous categorization tasks. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 152(6), 3728–3745. [CrossRef]

- Boersma, P., & Weenink, D. (2024). Praat: Doing phonetics by computer (Version Version 6.4.17) [Computer software]. University of Amsterdam. https://www.praat.org/.

- Bonnel, A., McAdams, S., Smith, B., Berthiaume, C., Bertone, A., Ciocca, V., Burack, J. A., Mottron, L., Bonnel, A., McAdams, S., Smith, B., Berthiaume, C., Bertone, A., Ciocca, V., Burack, J. A., & Mottron, L. (2010). Enhanced pure-tone pitch discrimination among persons with autism but not Asperger syndrome. Neuropsychologia, 48(9), 2465–2475. [CrossRef]

- Carney, A. E., Widin, G. P., & Viemeister, N. F. (1977). Noncategorical perception of stop consonants differing in VOT. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 62(4), 961–970. [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J. V. (2020). The Longitudinal Development of Fine-Phonetic Detail: Stop Production in a Domestic Immersion Program. Language Learning, 70(3), 768–806. [CrossRef]

- Centanni, T. M., Pantazis, D., Truong, D. T., Gruen, J. R., Gabrieli, J. D. E., & Hogan, T. P. (2018). Increased variability of stimulus-driven cortical responses is associated with genetic variability in children with and without dyslexia. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 34, 7–17. [CrossRef]

- Coady, J. A., Kluender, K. R., & Evans, J. L. (2005). Categorical Perception of Speech by Children With Specific Language Impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(4), 944–959. [CrossRef]

- Eimas, P. D., Miller, J. L., & Jusczyk, P. W. (1987). On infant speech perception and the acquisition of language. Categorical Perception: The Groundwork of Cognition., 161–195.

- Elzhov, T. V., Mullen, K. M., Spiess, A., & Bolker, B. (2023). minpack.lm: R interface to the levenberg-marquardt nonlinear least-squares algorithm [Computer software]. CRAN. https://cran.r-project.org/package=minpack.lm.

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., & Peng, G. (2023). Development of categorical speech perception in mandarin-speaking children and adolescents. Child Development, 94(1), 28–43. [CrossRef]

- Fitch, H. L., Halwes, T., Erickson, D. M., & Liberman, A. M. (1980). Perceptual equivalence of two acoustic cues for stop-consonant manner. Perception & Psychophysics, 27(4), 343–350. [CrossRef]

- Francis, A. L., Ciocca, V., & Chit Ng, B. K. (2003). On the (non)categorical perception of lexical tones. Perception & Psychophysics, 65(7), 1029–1044. [CrossRef]

- Frenck-Mestre, C., Meunier, C., Espesser, R., Daffner, K., & Holcomb, P. (2005). Perceiving Nonnative Vowels. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(6), 1496–1510. [CrossRef]

- Fry, D. B., Abramson, A. S., Eimas, P. D., & Liberman, A. M. (1962). The Identification and Discrimination of Synthetic Vowels. Language and Speech, 5(4), 171–189. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmeister, P., Myers, E. B., Fuhrmeister, P., & Myers, E. B. (2021). Structural neural correlates of individual differences in categorical perception. Brain and Language, 215, 104919. [CrossRef]

- Fuhrmeister, P., Phillips, M. C., McCoach, D. B., & Myers, E. B. (2023). Relationships between native and non-native speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 49(7), 1161–1175. [CrossRef]

- Gandour, J. (1983). Tone perception in Far Eastern languages. Journal of Phonetics, 11(2), 149–175. [CrossRef]

- Gerrits, E., & Schouten, M. E. H. (2004). Categorical perception depends on the discrimination task. Perception & Psychophysics, 66(3), 363–376. [CrossRef]

- Goldinger, S. D. (n.d.). Echoes of echoes? An episodic theory of lexical access. Psychological Review, 105(2), 251–279. [CrossRef]

- Hallé, P. A., Chang, Y.-C., & Best, C. T. (2004). Identification and discrimination of mandarin Chinese tones by mandarin chinese vs. French listeners. Journal of Phonetics, 32(3), 395–421. [CrossRef]

- Hary, J. M., & Massaro, D. W. (1982). Categorical results do not imply categorical perception. Perception & Psychophysics, 32(5), 409–418. [CrossRef]

- Healy, A. F., & Repp, B. H. (1982). Context independence and phonetic mediation in categorical perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 8(1), 68–80. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Honda, C. T., Clayards, M., & Baum, S. R. (2024a). Exploring individual differences in native phonetic perception and their link to nonnative phonetic perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 50(4), 370–394. [CrossRef]

- Honda, C. T., Clayards, M., & Baum, S. R. (2024b). Individual differences in the consistency of neural and behavioural responses to speech sounds. Brain Research, 1845, 149208. [CrossRef]

- Hornickel, J., & Kraus, N. (2013). Unstable Representation of Sound: A Biological Marker of Dyslexia. The Journal of Neuroscience, 33(8), 3500–3504. [CrossRef]

- Joanisse, M. F., Manis, F. R., Keating, P., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2000). Language Deficits in Dyslexic Children: Speech Perception, Phonology, and Morphology. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 77(1), 30–60. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K., & Ralston, J. V. (1994). Automaticity in Speech Perception: Some Speech/Nonspeech Comparisons. Phonetica, 51(4), 195–209. [CrossRef]

- Kapnoula, E. C., Edwards, J., & McMurray, B. (2021). Gradient activation of speech categories facilitates listeners’ recovery from lexical garden paths, but not perception of speech-in-noise. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 47(4), 578–595. [CrossRef]

- Kapnoula, E. C., Winn, M. B., Kong, E. J., Edwards, J., & McMurray, B. (2017). Evaluating the sources and functions of gradiency in phoneme categorization: An individual differences approach. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 43(9), 1594–1611. [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, H., Masuda-Katsuse, I., & de Cheveigné, A. (1999). Restructuring speech representations using a pitch-adaptive time–frequency smoothing and an instantaneous-frequency-based F0 extraction: Possible role of a repetitive structure in sounds. Speech Communication, 27(3–4), 187–207. [CrossRef]

- Kazanina, N., Phillips, C., & Idsardi, W. (2006). The influence of meaning on the perception of speech sounds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(30), 11381–11386. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D., Clayards, M., & Kong, E. J. (2020). Individual differences in perceptual adaptation to unfamiliar phonetic categories. Journal of Phonetics, 81, 100984. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Klein-Packard, J., Sorensen, E., Oleson, J., Tomblin, B., & McMurray, B. (2025). Speech categorization consistency is associated with language and reading abilities in school-age children: Implications for language and reading disorders. Cognition, 263, 106194. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., McMurray, B., Sorensen, E., & Oleson, J. (2025). The consistency of categorization-consistency in speech perception. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. [CrossRef]

- Kleinschmidt, D. F., & Jaeger, T. F. (2015). Robust speech perception: Recognize the familiar, generalize to the similar, and adapt to the novel. Psychological Review, 122(2), 148–203. [CrossRef]

- Kluender, K. R., Coady, J. A., & Kiefte, M. (2003). Sensitivity to change in perception of speech. Speech Communication, 41(1), 59–69. [CrossRef]

- Kong, E. J., & Edwards, J. (2016). Individual differences in categorical perception of speech: Cue weighting and executive function. Journal of Phonetics, 59, 40–57. [CrossRef]

- Kuhl, P. K. (1987). The special-mechanisms debate in speech research: Categorization tests on animals and infants. Categorical Perception: The Groundwork of Cognition., 355–386.

- Larkey, L. S., Wald, J., & Strange, W. (1978). Perception of synthetic nasal consonants in initial and final syllable position. Perception & Psychophysics, 23(4), 299–312. [CrossRef]

- Liberman, A., Harris, K. S., Eimas, P., Lisker, L., & Bastian, J. (1961). An Effect of Learning on Speech Perception: The Discrimination of Durations of Silence with and without Phonemic Significance. Language and Speech, 4(4), 175–195. [CrossRef]

- Liberman, A. M., Harris, K. S., Hoffman, H. S., & Griffith, B. C. (1957). The discrimination of speech sounds within and across phoneme boundaries. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 54(5), 358–368. [CrossRef]

- Liberman, A. M., Harris, K. S., Kinney, J. A., & Lane, H. (1961). The discrimination of relative onset-time of the components of certain speech and nonspeech patterns. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(5), 379–388. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Wang, M., Perfetti, C. A., Brubaker, B., Wu, S., & MacWhinney, B. (2011). Learning a Tonal Language by Attending to the Tone: An In Vivo Experiment. Language Learning, 61(4), 1119–1141. [CrossRef]

- Manis, F. R., Mcbride-Chang, C., Seidenberg, M. S., Keating, P., Doi, L. M., Munson, B., & Petersen, A. (1997). Are Speech Perception Deficits Associated with Developmental Dyslexia? Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 66(2), 211–235. [CrossRef]

- Massaro, D. W., & Cohen, M. M. (1983). Categorical or continuous speech perception: A new test. Speech Communication, 2(1), 15–35. [CrossRef]

- McClelland, J. L., & Elman, J. L. (1986). The TRACE model of speech perception. Cognitive Psychology, 18(1), 1–86. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, B. (2022). The myth of categorical perception. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 152(6), 3819–3842. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, B., Munson, C., & Tomblin, J. B. (2014). Individual differences in language ability are related to variation in word recognition, not speech perception: Evidence from eye movements. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(4), 1344–1362. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, B., Tanenhaus, M. K., & Aslin, R. N. (2002). Gradient effects of within-category phonetic variation on lexical access. Cognition, 86(2), B33–B42. [CrossRef]

- McMurray, B., Tanenhaus, M. K., & Aslin, R. N. (2009). Within-category VOT affects recovery from “lexical” garden-paths: Evidence against phoneme-level inhibition. Journal of Memory and Language, 60(1), 65–91. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. L., & Eimas, P. D. (1977). Studies on the perception of place and manner of articulation: A comparison of the labial-alveolar and nasal-stop distinctions. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 61(3), 835–845. [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. L., & Volaitis, L. E. (1989). Effect of speaking rate on the perceptual structure of a phonetic category. Perception & Psychophysics, 46(6), 505–512. [CrossRef]

- Minagawa-Kawai, Y., Mori, K., Naoi, N., & Kojima, S. (2007). Neural Attunement Processes in Infants during the Acquisition of a Language-Specific Phonemic Contrast. The Journal of Neuroscience, 27(2), 315–321. [CrossRef]

- Miyawaki, K., Jenkins, J. J., Strange, W., Liberman, A. M., Verbrugge, R., & Fujimura, O. (1975). An effect of linguistic experience: The discrimination of [r] and [l] by native speakers of Japanese and English. Perception & Psychophysics, 18(5), 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Morton, K. D., Torrione, P. A., Throckmorton, C. S., & Collins, L. M. (2008). Mandarin Chinese tone identification in cochlear implants: Predictions from acoustic models. Hearing Research, 244(1–2), 66–76. [CrossRef]

- Myers, E., Phillips, M., & Skoe, E. (2024). Individual differences in the perception of phonetic category structure predict speech-in-noise performance. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 156(3), 1707–1719. [CrossRef]

- Näätänen, R., Paavilainen, P., Rinne, T., & Alho, K. (2007). The mismatch negativity (MMN) in basic research of central auditory processing: A review. Clinical Neurophysiology, 118(12), 2544–2590. [CrossRef]

- Newell, F. N., & Bülthoff, H. H. (2002). Categorical perception of familiar objects. Cognition, 85(2), 113–143. [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K., & O’Connor, K. (2012). Auditory processing in autism spectrum disorder: A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(2), 836–854. [CrossRef]

- Oden, G. C., Massaro, D. W., Oden, G. C., & Massaro, D. W. (1978). Integration of featural information in speech perception. Psychological Review, 85(3), 172–191. [CrossRef]

- Ou, J., & Yu, A. C. L. (2022). Neural correlates of individual differences in speech categorisation: Evidence from subcortical, cortical, and behavioural measures. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 37(3), 269–284. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, D. B. (1973). Auditory and phonetic memory codes in the discrimination of consonants and vowels. Perception & Psychophysics, 13(2), 253–260. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, D. B., & Lazarus, J. H. (1974). Categorical and noncategorical modes of speech perception along the voicing continuum. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 55(2), 328–333. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Repp, B. H. (1984). Categorical perception: Issues, methods, findings. In Speech and Language (Vol. 10, pp. 243–335). Elsevier. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780126086102500121.

- Robertson, E. K., Joanisse, M. F., Desroches, A. S., & Ng, S. (2009). Categorical speech perception deficits distinguish language and reading impairments in children. Developmental Science, 12(5), 753–767. [CrossRef]

- Sarrett, M. E., McMurray, B., & Kapnoula, E. C. (2020). Dynamic EEG analysis during language comprehension reveals interactive cascades between perceptual processing and sentential expectations. Brain and Language, 211, 104875. [CrossRef]

- Schouten, B., Gerrits, E., & Van Hessen, A. (2003). The end of categorical perception as we know it. Speech Communication, 41(1), 71–80. [CrossRef]

- Serniclaes, W., Heghe, S. V., Mousty, P., Carré, R., & Sprenger-Charolles, L. (2004). Allophonic mode of speech perception in dyslexia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 87(4), 336–361. [CrossRef]

- Serniclaes, W., Sprenger-Charolles, L., Carré, R., & Demonet, J.-F. (2001). Perceptual Discrimination of Speech Sounds in Developmental Dyslexia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 44(2), 384–399. [CrossRef]

- Serniclaes, W., Ventura, P., Morais, J., & Kolinsky, R. (2005). Categorical perception of speech sounds in illiterate adults. Cognition, 98(2), B35–B44. [CrossRef]

- Skoe, E., Krizman, J., Anderson, S., & Kraus, N. (2015). Stability and Plasticity of Auditory Brainstem Function Across the Lifespan. Cerebral Cortex, 25(6), 1415–1426. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, E., Oleson, J., Kutlu, E., & McMurray, B. (2024). A bayesian hierarchical model for the analysis of visual analogue scaling tasks. Statistical Methods in Medical Research, 33(6), 953–965. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, K. N., Libermann, A. M., Studdert-Kennedy, M., & Öhman, S. E. G. (1969). Crosslanguage Study of Vowel Perception. Language and Speech, 12(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, M. E., Petrou, A. M., & Ota, M. (2018). Categorical speech perception in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(1), 72–82. [CrossRef]

- Toscano, J. C., & McMurray, B. (2015). The time-course of speaking rate compensation: Effects of sentential rate and vowel length on voicing judgments. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience, 30(5), 529–543. [CrossRef]

- Toscano, J. C., McMurray, B., Dennhardt, J., & Luck, S. J. (2010). Continuous perception and graded categorization: Electrophysiological evidence for a linear relationship between the acoustic signal and perceptual encoding of speech. Psychological Science, 21(10), 1532–1540. [CrossRef]

- van Hessen, A. J., & Schouten, M. E. H. (1999). Categorical perception as a function of stimulus quality. Phonetica, 56(1–2), 56–72. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., Wang, S., Fan, Y., Huang, D., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Speech-specific categorical perception deficit in autism: An Event-Related Potential study of lexical tone processing in Mandarin-speaking children. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 43254. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Jongman, A., & Sereno, J. A. (2003). Acoustic and perceptual evaluation of Mandarin tone productions before and after perceptual training. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 113(2), 1033–1043. [CrossRef]

- Werker, J. F., & Tees, R. C. (1987). Speech perception in severely disabled and average reading children. Canadian Journal of Psychology / Revue Canadienne de Psychologie, 41(1), 48–61. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Whalen, D. H., & Xu, Y. (1992). Information for mandarin tones in the amplitude contour and in brief segments. Phonetica, 49(1), 25–47. [CrossRef]

- Wiener, S., & Lee, C.-Y. (2020). Multi-Talker Speech Promotes Greater Knowledge-Based Spoken Mandarin Word Recognition in First and Second Language Listeners. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 214. [CrossRef]

- Xi, J., Zhang, L., Shu, H., Zhang, Y., & Li, P. (2010). Categorical perception of lexical tones in Chinese revealed by mismatch negativity. Neuroscience, 170(1), 223–231. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y., Gandour, J. T., & Francis, A. L. (2006). Effects of language experience and stimulus complexity on the categorical perception of pitch direction. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 120(2), 1063–1074. [CrossRef]

- Yip, M. (2002). Tone. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge Core. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/B511461D134BE12E23AA9E30CD311036.

- Yu, A. C. L. (2010). Perceptual Compensation Is Correlated with Individuals’ “Autistic” Traits: Implications for Models of Sound Change. PLoS ONE, 5(8), e11950. [CrossRef]

- Yu, A. C. L., Abrego-Collier, C., & Sonderegger, M. (2013). Phonetic imitation from an individual-difference perspective: Subjective attitude, personality and “autistic” traits. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e74746. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Xi, J., Wu, H., Shu, H., & Li, P. (2012). Electrophysiological evidence of categorical perception of Chinese lexical tones in attentive condition. NeuroReport, 23(1), 35–39. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Cheng, B., Qin, D., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Is talker variability a critical component of effective phonetic training for nonnative speech? Journal of Phonetics, 87, 101071. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Shu, H., Xi, J., Wu, H., Zhang, Y., Li, P. (2012). Universality of categorical perception deficit in developmental dyslexia: An investigation of Mandarin Chinese tones. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(8), 874–882. [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J. C., Pech-Georgel, C., George, F., Alario, F.-X., & Lorenzi, C. (2005). Deficits in speech perception predict language learning impairment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(39), 14110–14115. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).