Submitted:

22 October 2025

Posted:

23 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Nomenclature (in Alphabetical Order, Greek Symbols First)

| Albedo (or reflectivity or reflectance) | |

| ABG | Approximated bifacial gain. It is the ratio of excess electricity generated from a bifacial photovoltaic module (panel) or array beyond the electricity generated from a monofacial module or array having the same capacity (same kilowatts peak; given that for the bifacial module, this capacity is for the front face only). |

| AC | Alternating current |

| AM | Air mass |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials [1] |

| BF | Bifaciality factor. It is the ratio of electricity generated (or power capacity) from the rear side of a bifacial photovoltaic module (panel) to the electricity generated (or power capacity) from its front side, when both sides are irradiated at standard test conditions (STC). A representative value for bifaciality factor (BF) is 70%. The bifaciality factor is also called “module bifaciality” or (MB). |

| BG | Bifacial gain. It is the ratio of additional (secondary) electricity generated (or additional power capacity) from the rear side of a bifacial photovoltaic module (panel) to the primary electricity generated (or primary power capacity) from its front side, when the front side is irradiated at standard test conditions (STC) [2,3], while the rear side is subject to indirect reflected irradiance. The bifacial gain depends on both the local ground albedo and the bifaciality factor. A representative value for the bifacial gain is 10%. |

| CAE | Computer-aided engineering |

| CAGR | Compound annual growth rate |

| DC | Direct current |

| DC-to-AC ratio | Ratio of the nominal output photovoltaic direct current power (at standard test conditions) to the nominal output alternating current power after the inverter stage [4]. This parameter is also called “inverter loading ratio” or (ILR) [5,6]. |

| DNI | Direct normal irradiance |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GPS | Global positioning system |

| IBC | Interdigitated back contact |

| IFI | Institute for Future Intelligence (Massachusetts, USA) |

| kWac | Kilowatt of alternating current electricity (after inverting the direct current electricity produced by the photovoltaic modules using an inverter stage) |

| kWh | Kilowatt-hour of alternating current electric energy from the overall photovoltaic system (net energy, after the inverter stage and any system losses) |

| kWp | Kilowatt peak, a unit of the direct current electric power for photovoltaic modules (panels). It is used to express the nameplate electricity generation capacity at standard test conditions (STC). |

| IEA | International Energy Agency (Paris, France) |

| ILR | Inverter loading ratio (same as the “DC-to-AC ratio”) [7] |

| IRR | Internal rate of return |

| HC | Half cut |

| LCOE | Levelized cost of electricity |

| MB | Module bifaciality (same as the “bifaciality factor”, BF) |

| MBB | Multi-busbar |

| NASA | United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NPV | Net present value |

| NZE | Net Zero Emissions by 2050 scenario by the International Energy Agency (IEA) |

| PERC | Passivated emitter and rear contact |

| PPA | Power purchase agreement |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| PVGIS | Photovoltaic Geographical Information System |

| SAF | Sustainable aviation fuel |

| SC | Short circuit |

| SMBB | Super multi-busbar |

| SPP | Simple payback period |

| STC | Standard test conditions of a photovoltaic panel (module): 1000 W/m2 hemispherical terrestrial irradiance, with a standardized irradiance spectrum (G173-03, by ASTM: American Society for Testing and Materials) [8], cell temperature 25 °C (298.15 K), and air mass AM 1.5 [9,10] |

| STEM | Science, technology, engineering, and mathematics |

| TES | Total energy supply |

2. Introduction

2.1. Background

2.2. Goal of the Study

- Buraimi or Al Buraimi [117] (an inland city bordering the United Arab Emirates, about 270 km “straight-line distance” west-northwest of Muscat)

- Duqm or Al Duqm [118] (a coastal city in the east of Oman, facing the Arabian Sea)

- Ibri [119] (an inland city, about 200 km “straight-line distance” west-southwest of Muscat)

- Muscat [122] (the capital of Oman, a coastal city facing the Gulf of Oman)

- Salalah [123] (a coastal city in the south of Oman)

- Sohar [124] (a coastal city in the northern mainland of Oman, facing the Gulf of Oman)

2.3. Article Structure

3. Research Method

3.1. Research Type and Research Questions

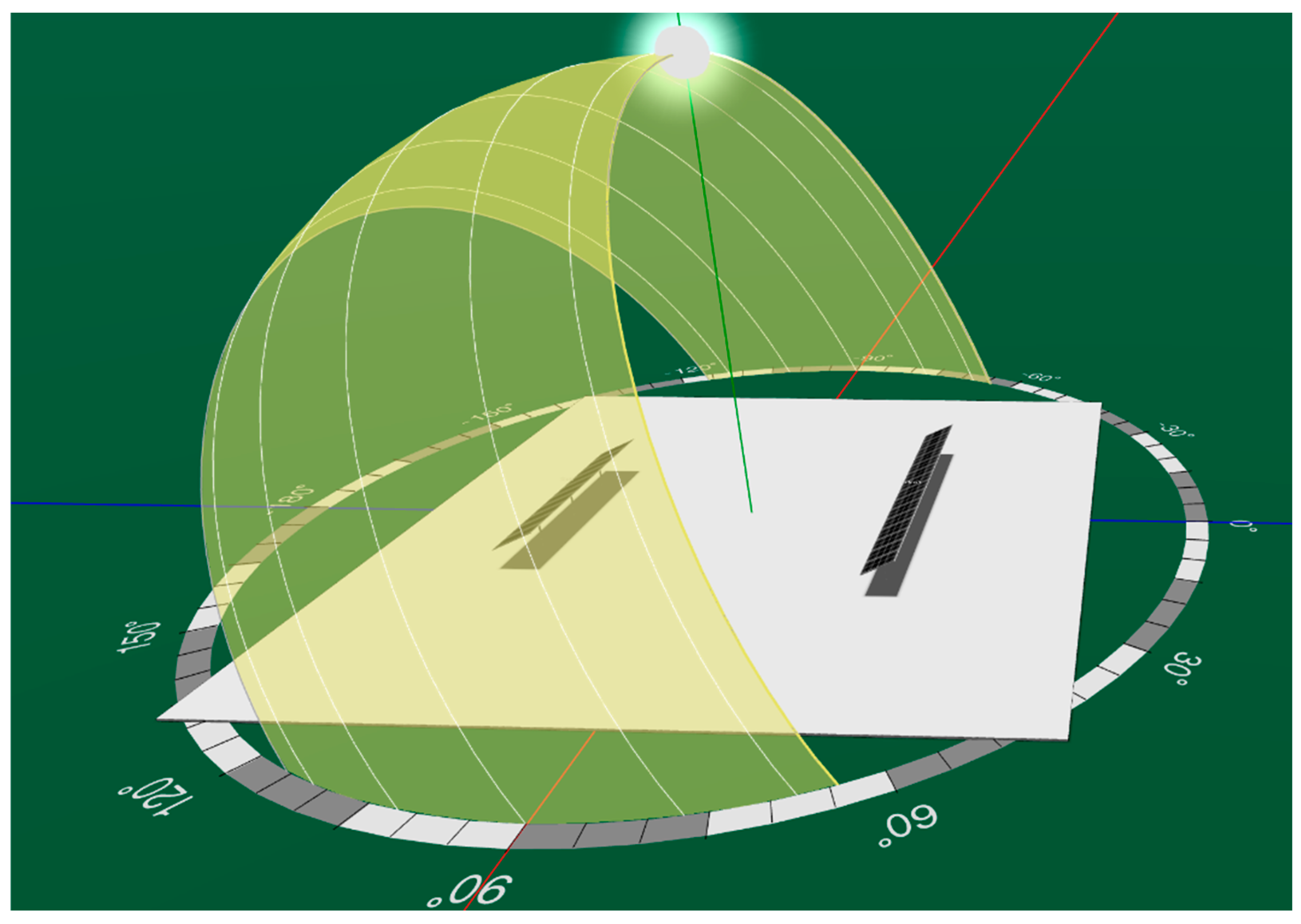

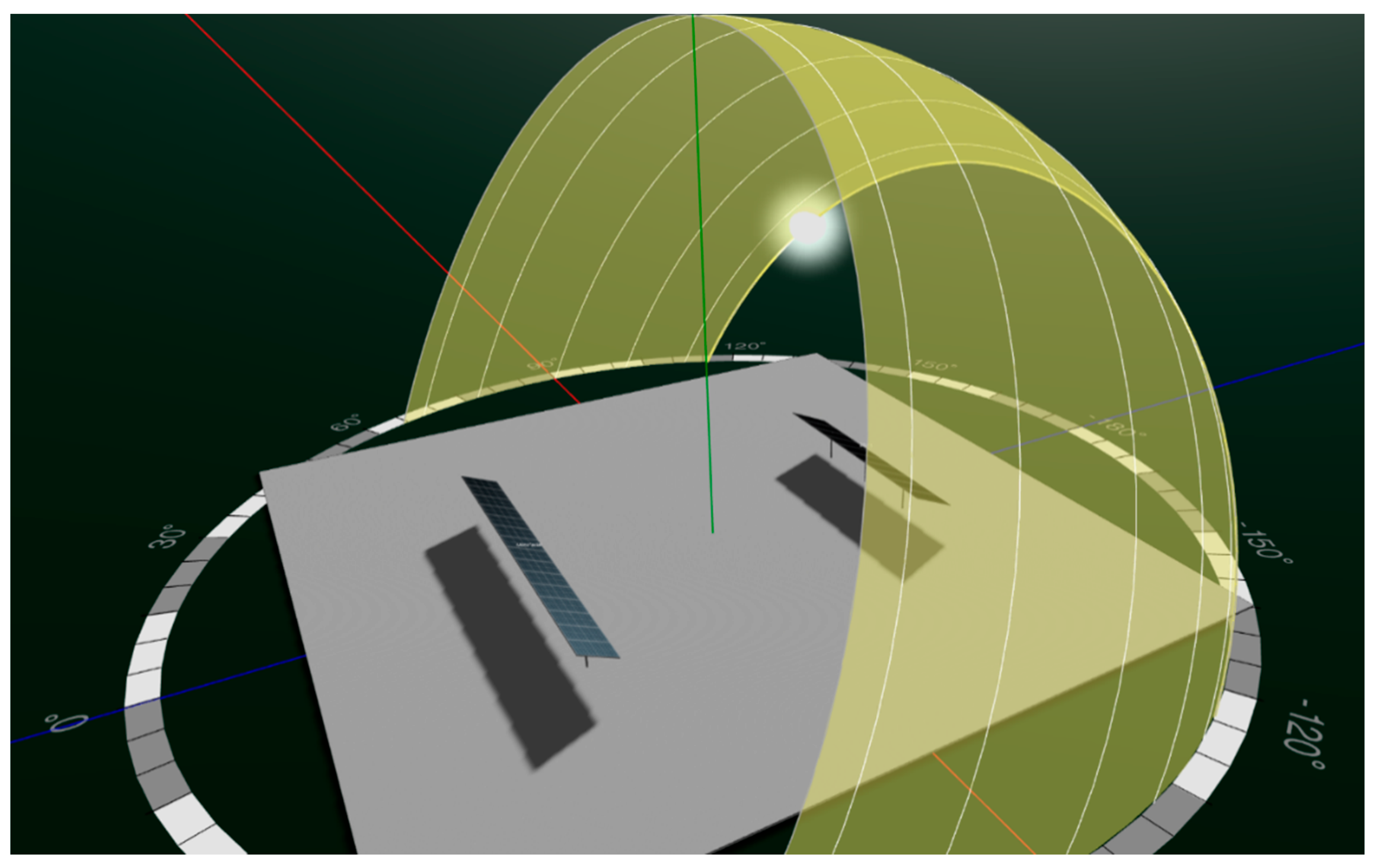

3.2. Photovoltaic Modeling Tool

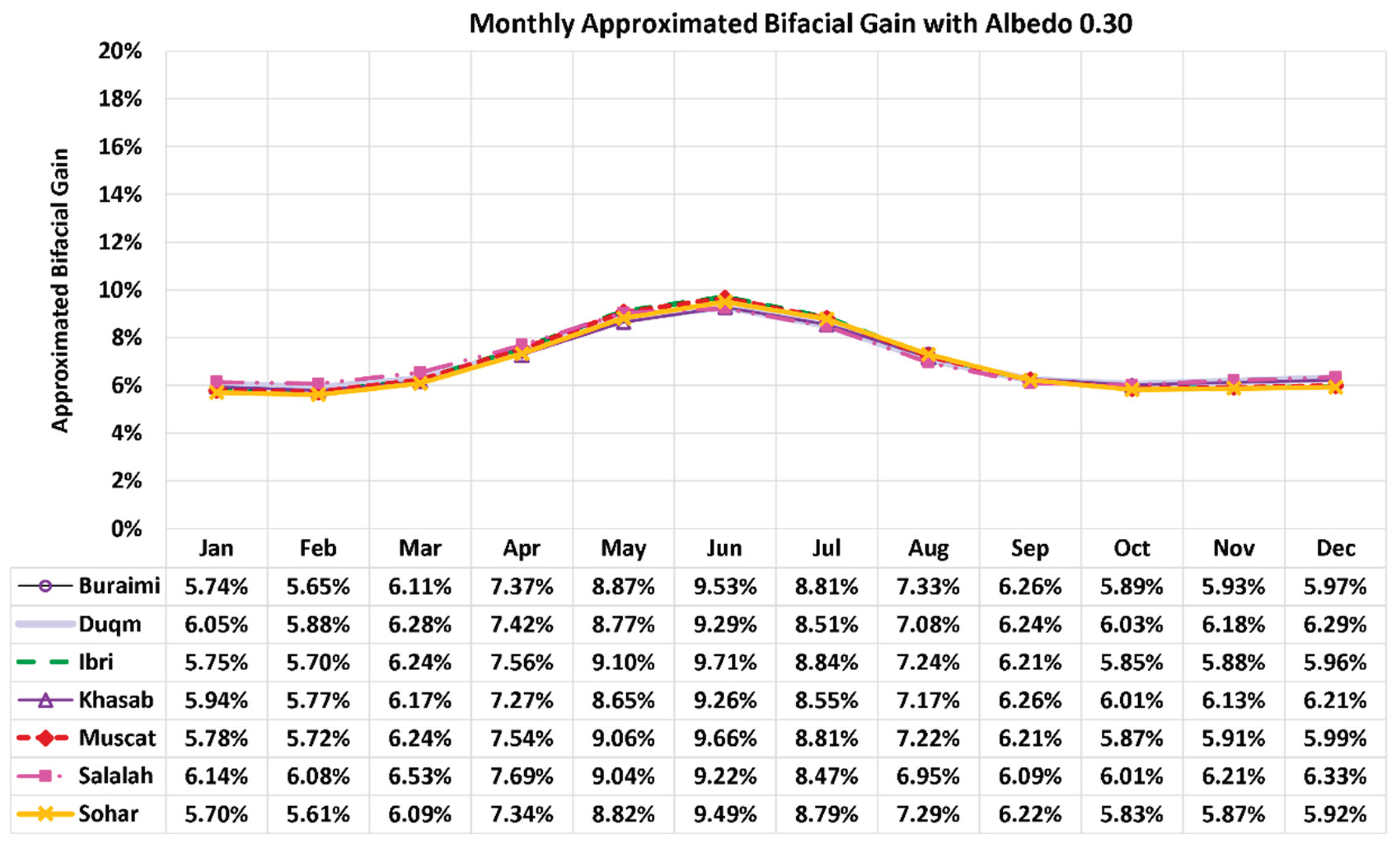

3.3. Approximated Bifacial Gain (ABG)

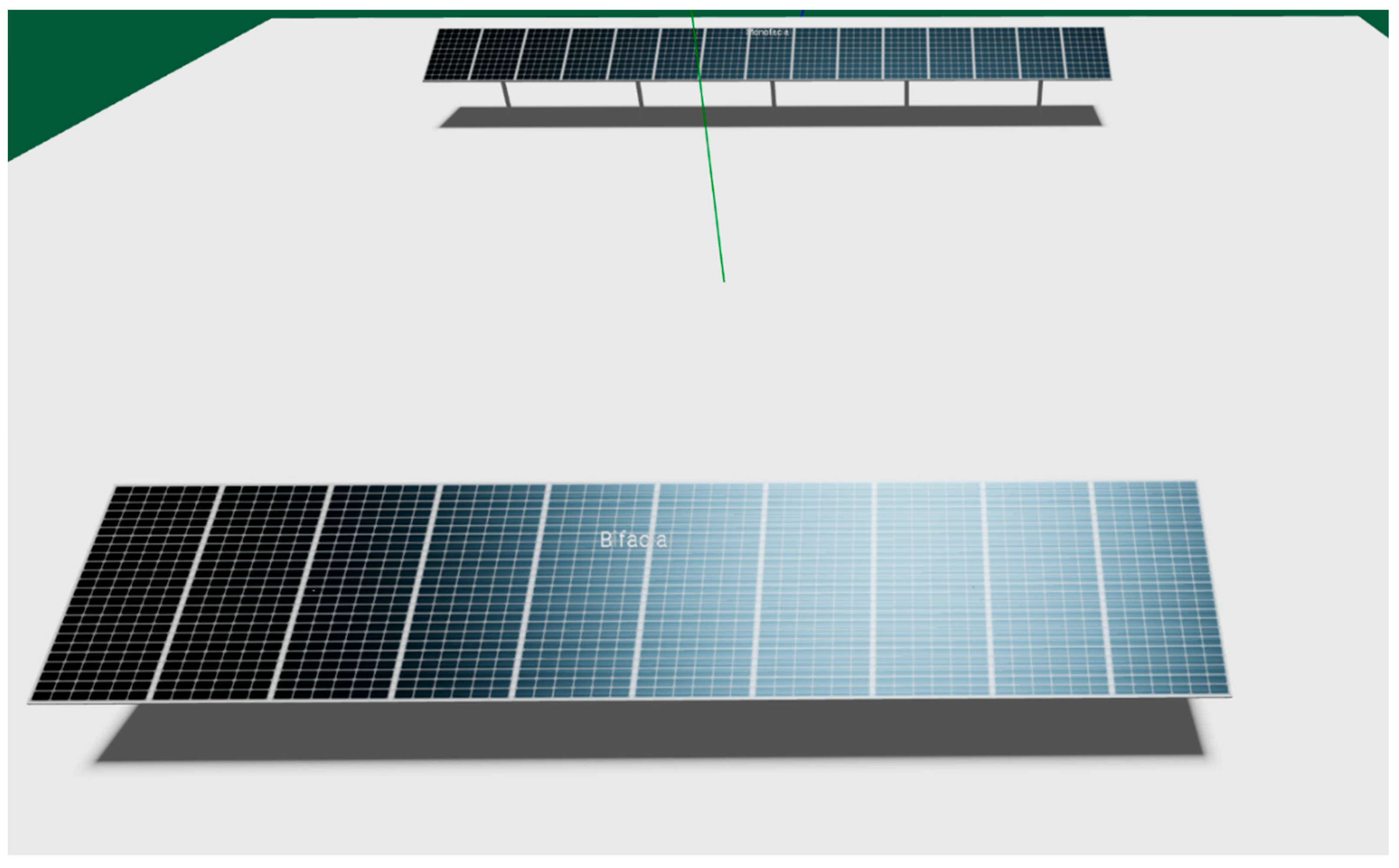

3.4. General Simulation Parameters for the 4.5 kWp Monofacial and Bifacial Systems

4. Benchmarking Simulation Cases

4.1. Monofacial Benchmarking Simulation Parameters

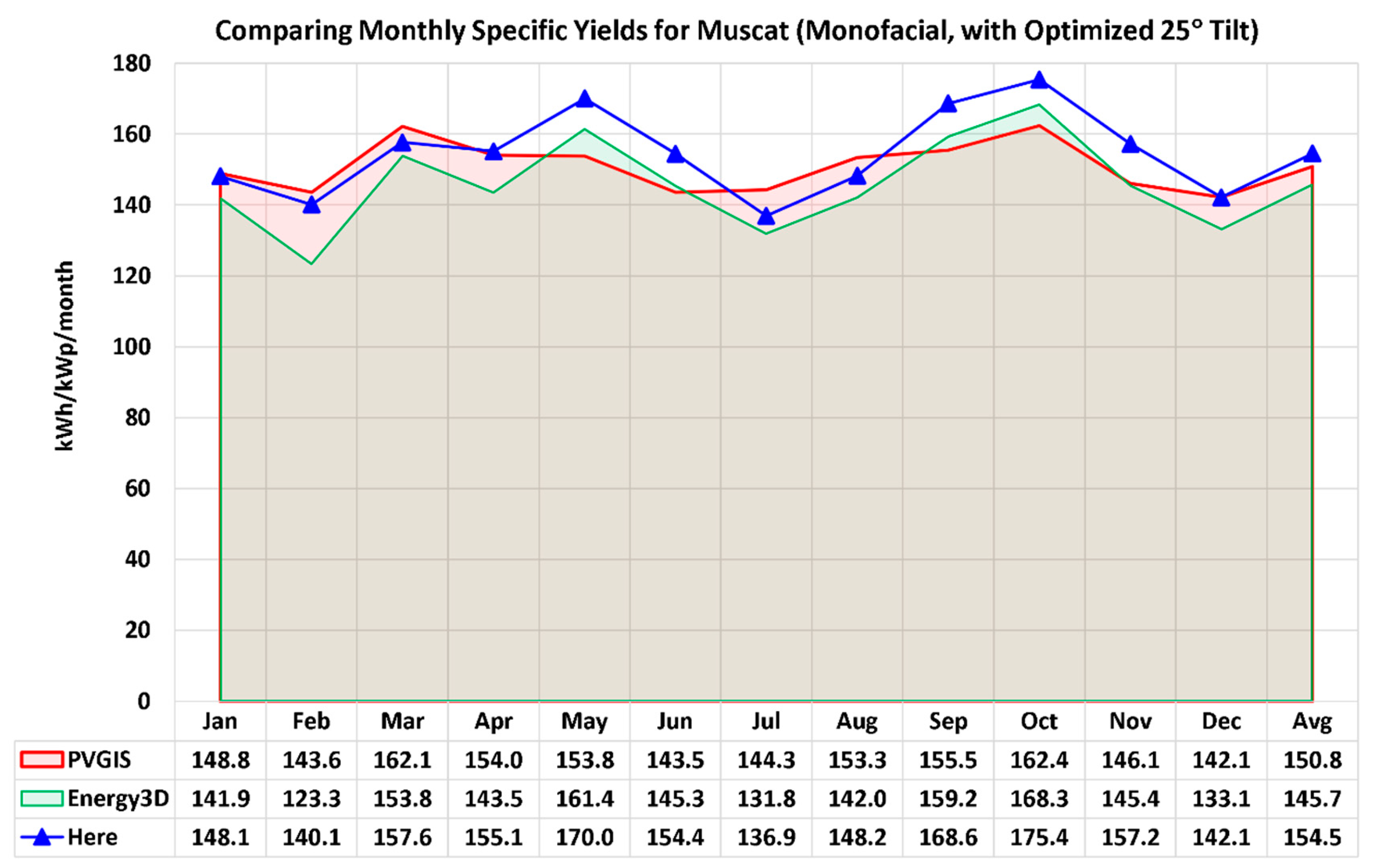

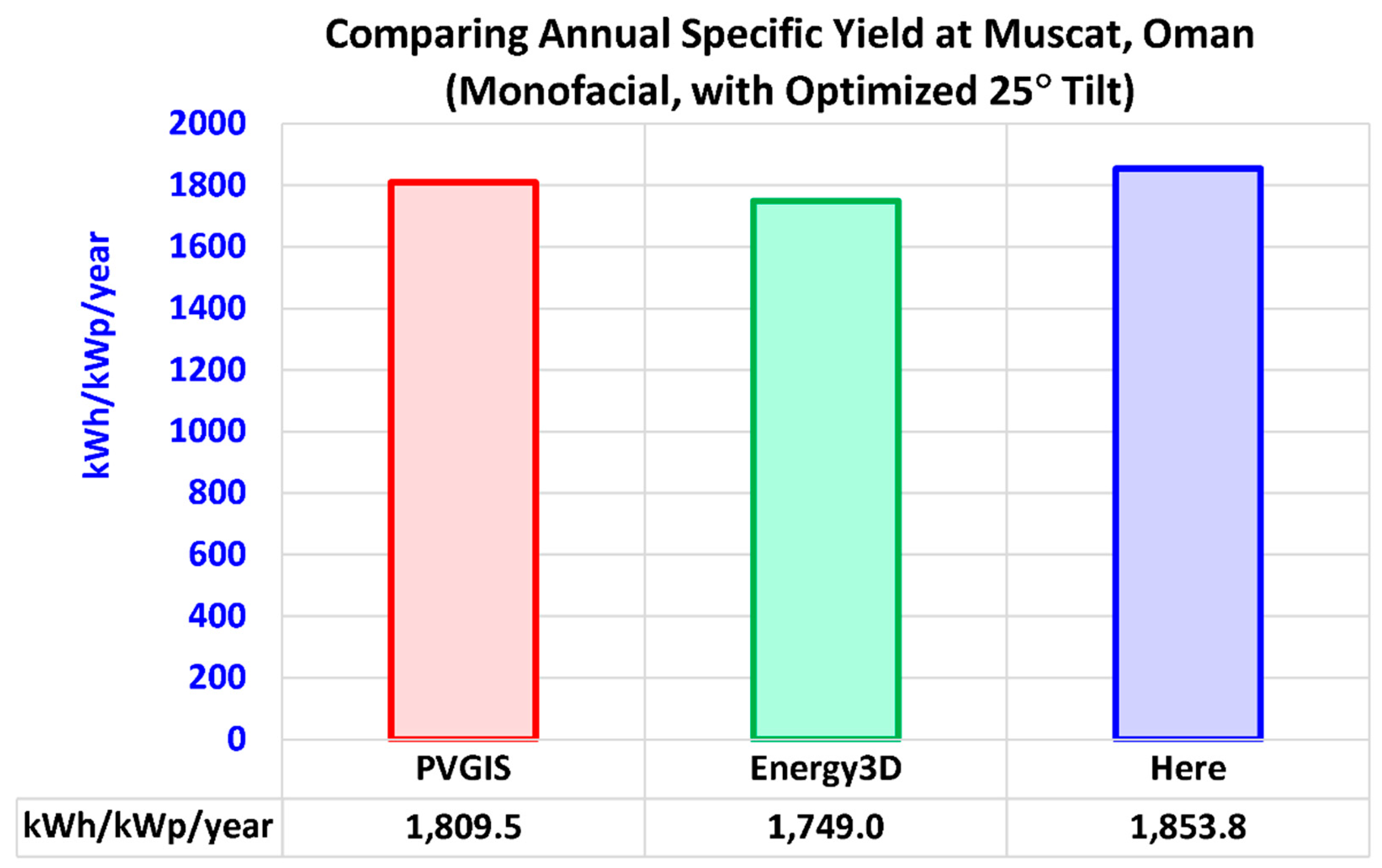

4.2. Monofacial Benchmarking Simulation Assessment

4.3. Bifacial Benchmarking Simulation Parameters

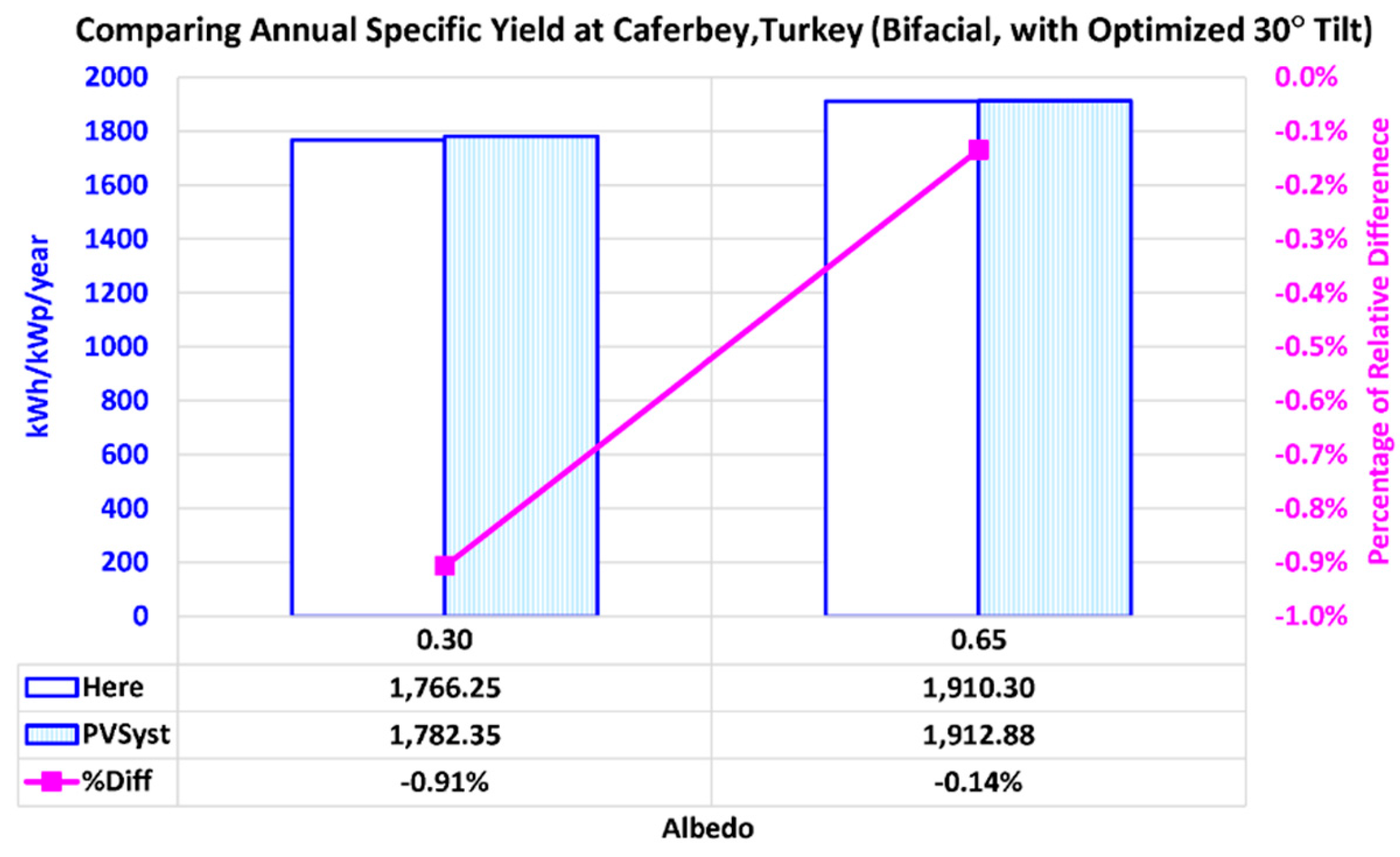

4.4. Bifacial Benchmarking Simulation Assessment

5. Main Results

5.1. Selected Seven Omani Locations and Their Optimum PV Tilt Angles

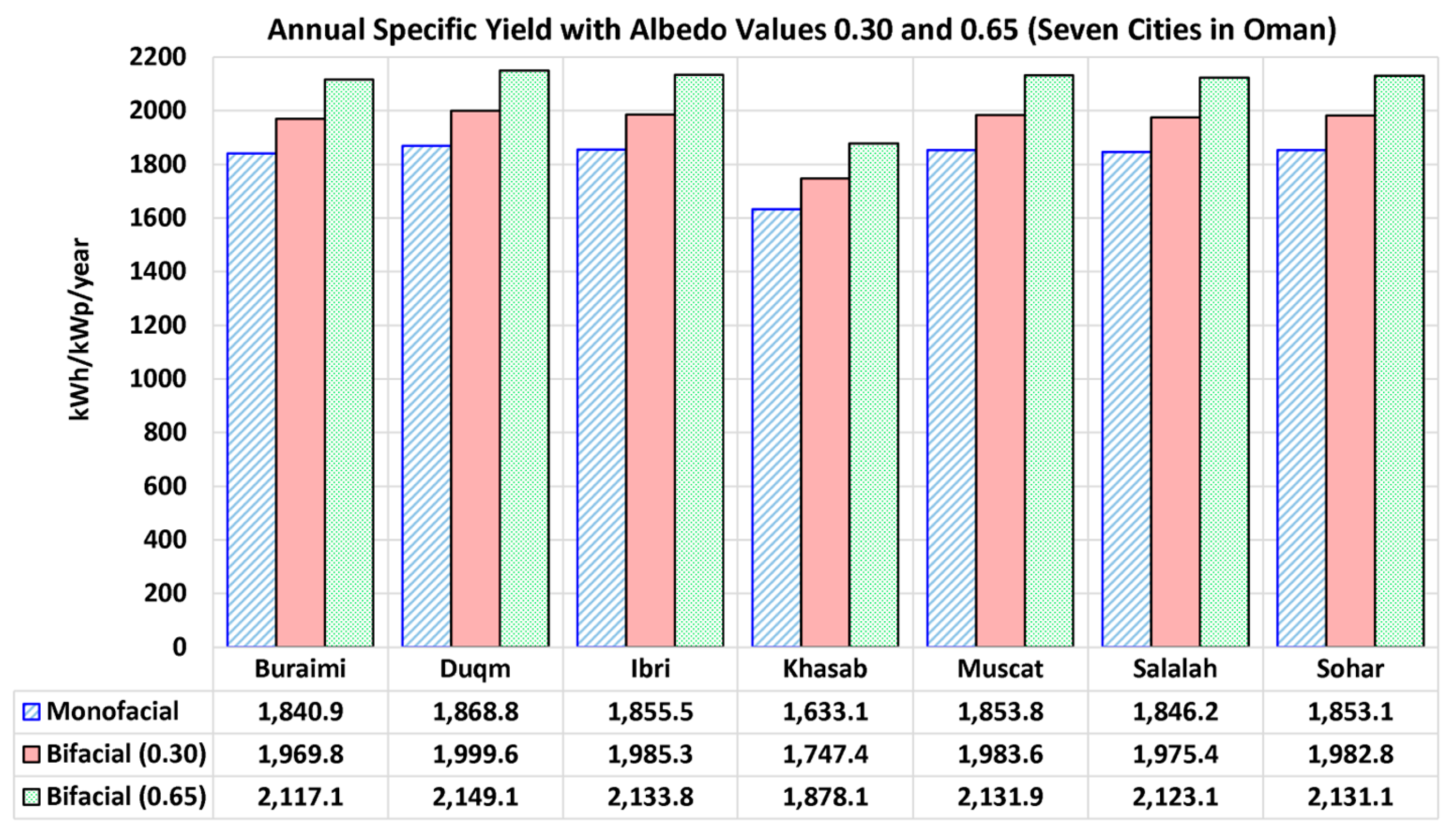

5.2. Gain in Annual Electric Yield with Bifacial Modules (Low and High Albedos)

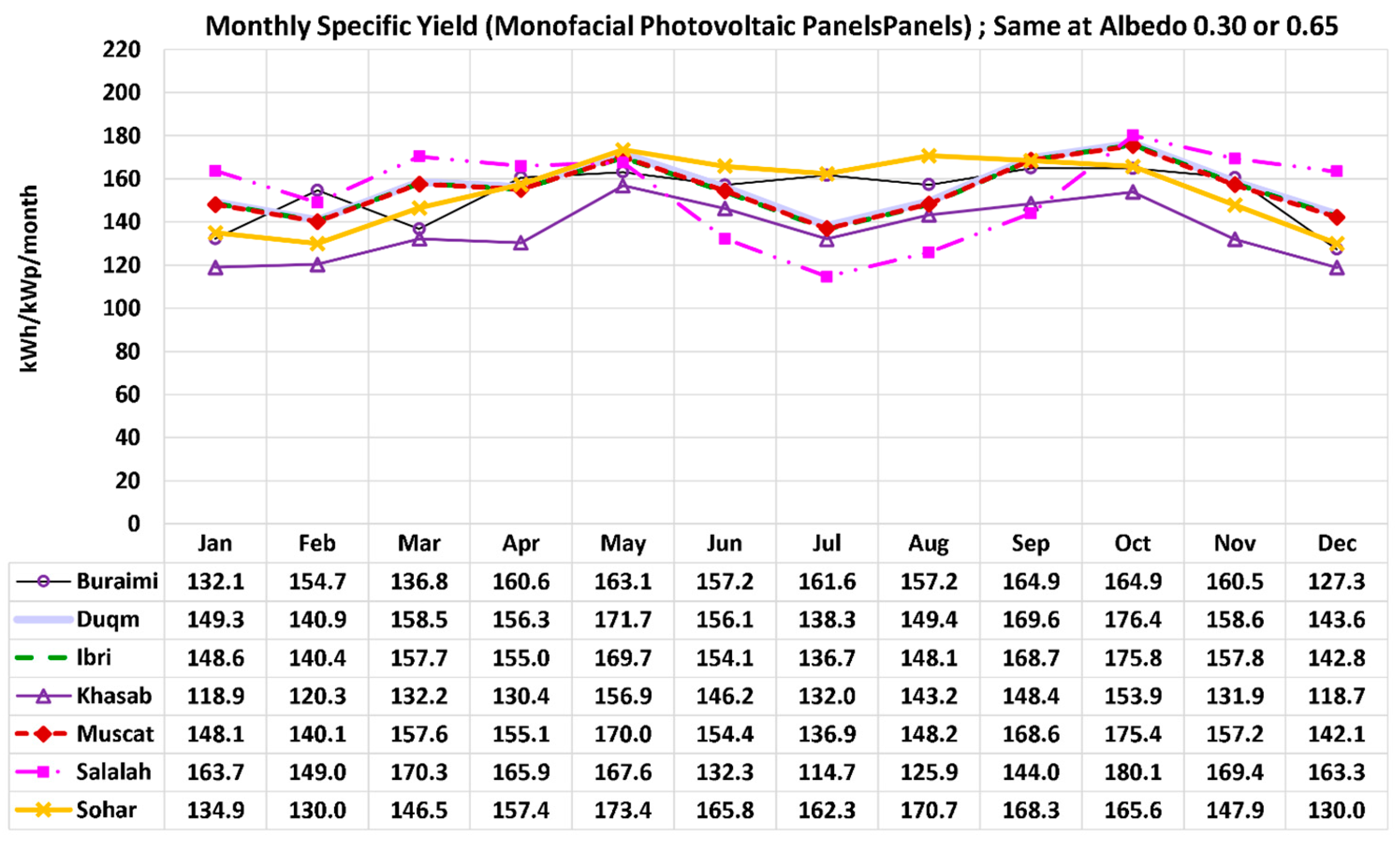

5.3. Monthly Electricity Generation with Monofacial PV Modules

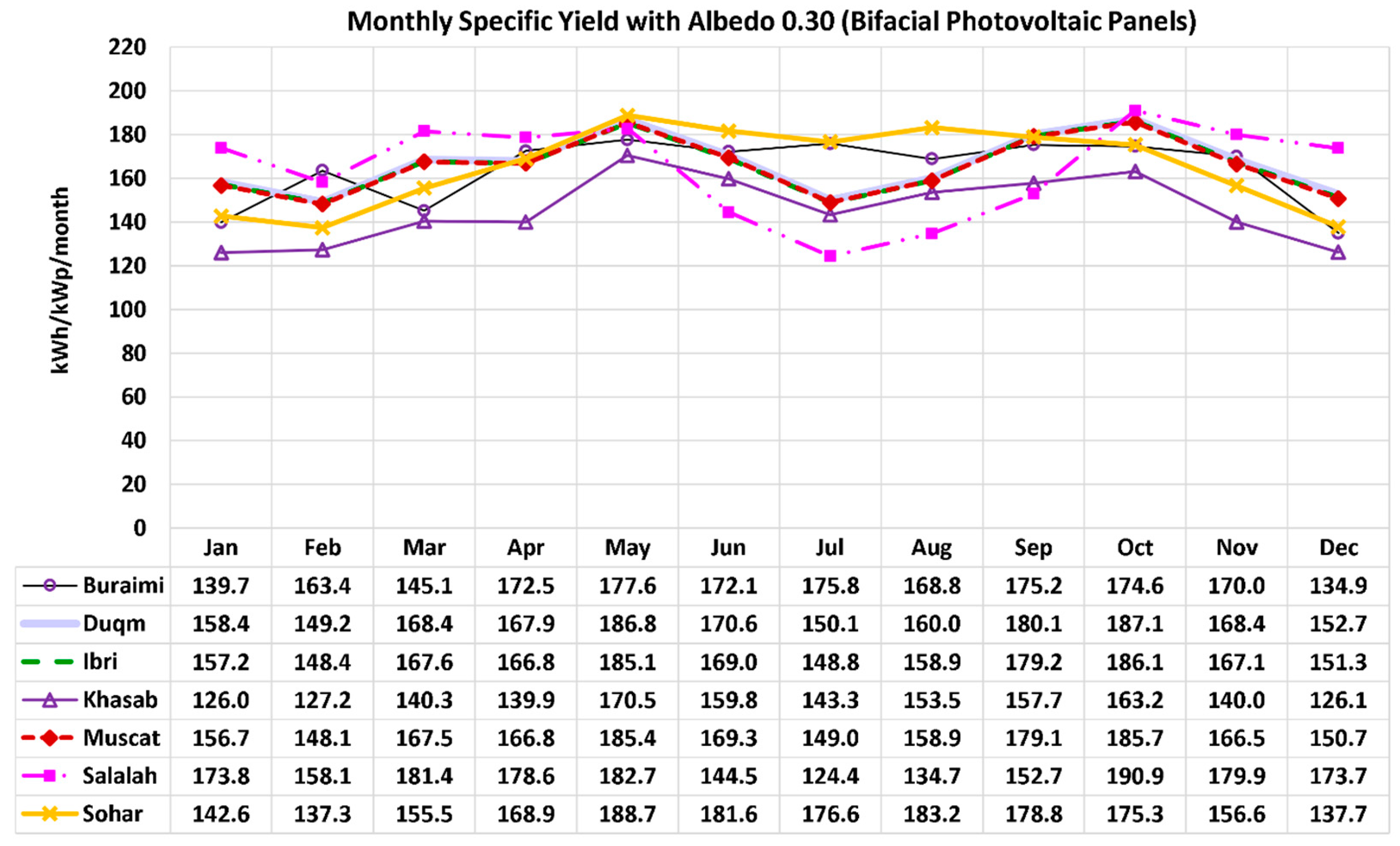

5.4. Monthly Electricity Generation with Bifacial Modules at Low Albedo 0.30

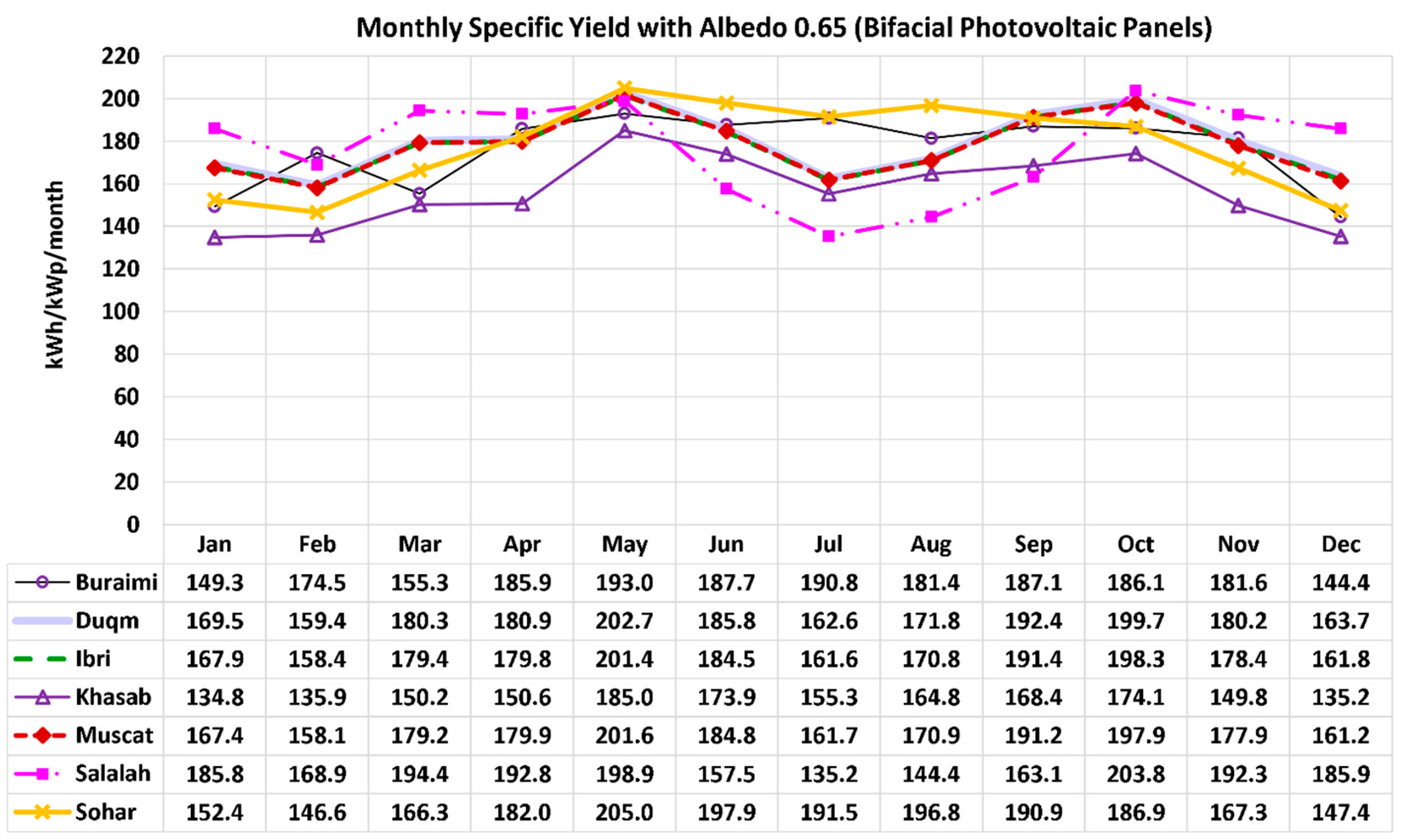

5.5. Monthly Electricity Generation with Bifacial Modules at High Albedo 0.65

6. Conclusions

- Various simulation tools for photovoltaic (PV) systems may differ in their estimations based on internal assumptions and modeling algorithm, but we found general agreement among Aladdin, PVGIS, Energy3D, and PVsyst. However, the user’s customized parameters still can affect the estimations.

- The approximated bifacial gain (ABG) is proposed here as a new supplementary performance metric in addition to the conventional bifacial gain (BG).

- Bifacial photovoltaic modules are promising if the ground albedo is at least 0.30, where the electricity gain can reach 7%.

- Applying special ground covering or foundation coating for bifacial photovoltaic modules such that the ground albedo is artificially boosted to 0.65 can double the electricity generation gain compared to plain sandy lands, reaching about 15%.

- The solar power utilization in Oman is generally promising, even in regions with seasonal rains, such as the coastal city of Khasab in the north and the coastal city of Salalah in the south.

- The average daily alternating current (AC) electricity generation in Oman per unit kWp of DC peak capacity is about 5 kWh (monofacial PV systems), 5.3 kWh (bifacial PV systems with albedo 0.30), and 5.7 kWh (bifacial PV systems with albedo 0.65).

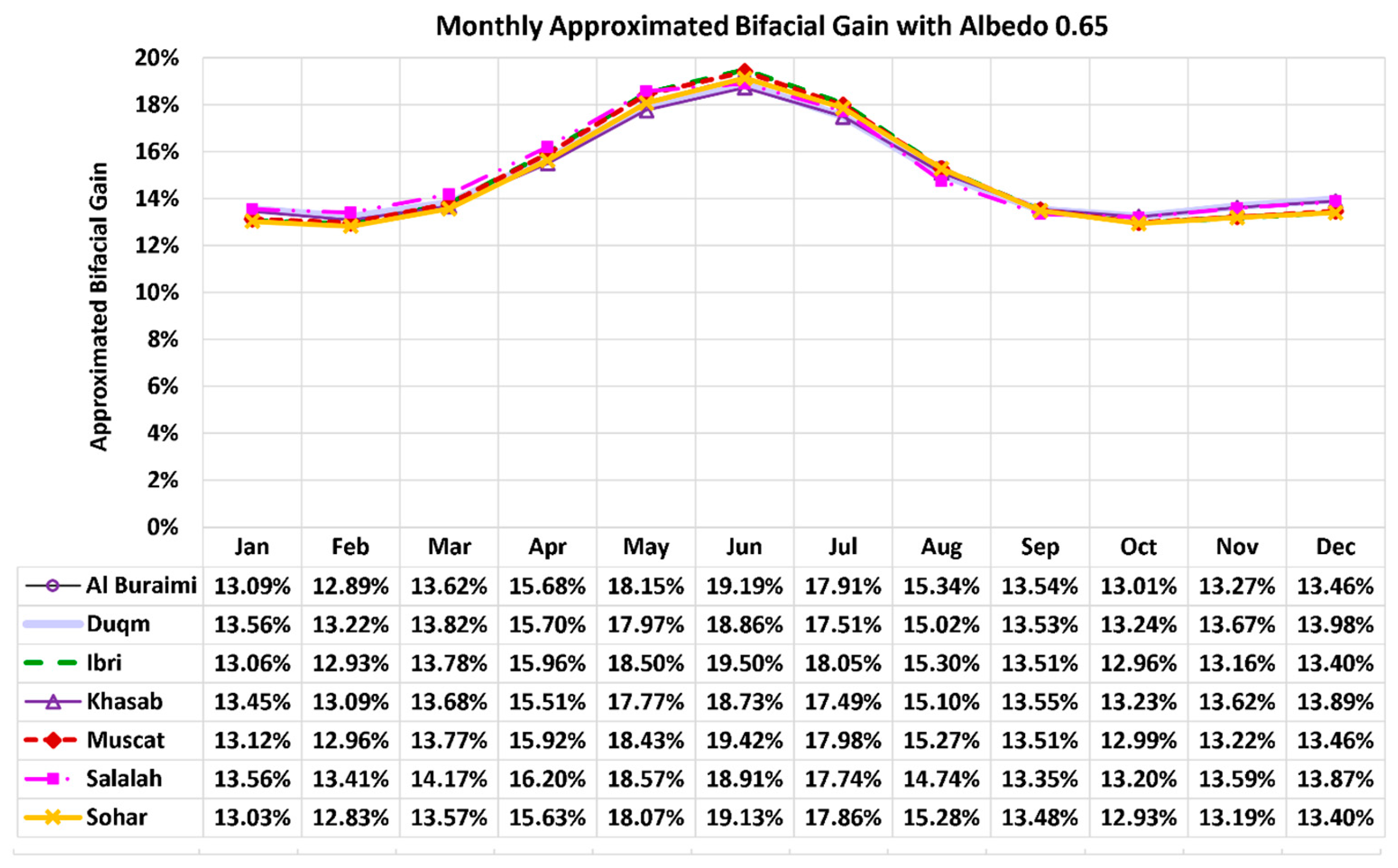

- The bifaciality gain in all the analyzed Omani cities here has a seasonal pattern, peaking in the summer (June), while dropping and nearly following a flat level in the winter months.

- We recommend installing bifacial PV modules if the additional expenses compared to monofacial modules are below 10%, where the extra cost can be justified with the anticipated electricity gain during the lifetime of the PV system, with little maintenance efforts and expenses to maintain a high ground albedo. Whereas if the cost differential exceeds 10%, then special care should be paid by installers and investors to the running cost of maintaining an artificially high ground albedo.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ASTM International. ASTM │ Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.astm.org/faq (accessed 2025-04-24).

- Zhang, Z.; Crossland, A. F.; MacKenzie, R. C. I.; Groves, C. From Lab to Reality: How Non-AM1.5 Conditions Shape the Future of Perovskite and Organic Solar Cells. EES Sol. 2025, 1 (5), 748–761. [CrossRef]

- Badran, R.; Ismail, Y. Methodology to Validate Measured Performance and Warranty Conditions of PV Modules. Solar Energy 2025, 295, 113552. [CrossRef]

- Choi, U.-M. Study on Effect of Installation Location on Lifetime of PV Inverter and DC-to-AC Ratio. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 86003–86011. [CrossRef]

- Good, J.; Johnson, J. X. Impact of Inverter Loading Ratio on Solar Photovoltaic System Performance. Applied Energy 2016, 177, 475–486. [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Pal, A.; Ilango, G. S. Impact of Inverter DC to AC Ratio on Soiling Losses and Cleaning Intervals in Large Solar PV Plants. Solar Energy 2025, 300, 113825. [CrossRef]

- Martins Deschamps, E.; Rüther, R. Optimization of Inverter Loading Ratio for Grid Connected Photovoltaic Systems. Solar Energy 2019, 179, 106–118. [CrossRef]

- ASTM. ASTM G173-03(2020) │ Standard Tables for Reference Solar Spectral Irradiances: Direct Normal and Hemispherical on 37° Tilted Surface. https://www.astm.org/g0173-03r20.html (accessed 2025-03-03).

- Bücher, K. Site Dependence of the Energy Collection of PV Modules. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 1997, 47 (1), 85–94. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. A Flight-Mechanics Solver for Aircraft Inverse Simulations and Application to 3D Mirage-III Maneuver. Global Journal of Control Engineering and Technology 2015, 1, 14–26.

- Parida, B.; Iniyan, S.; Goic, R. A Review of Solar Photovoltaic Technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15 (3), 1625–1636. [CrossRef]

- Louwen, A.; van Sark, W. Chapter 5 - Photovoltaic Solar Energy. In Technological Learning in the Transition to a Low-Carbon Energy System; Junginger, M., Louwen, A., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp 65–86. [CrossRef]

- Gharehpetian, G. B.; Agah, S. M. M. Distributed Generation Systems: Design, Operation and Grid Integration; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, U.K., 2017.

- IEA, [International Energy Agency]. IEA │ Share of renewable electricity generation by technology, 2000-2030. IEA. https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/charts/share-of-renewable-electricity-generation-by-technology-2000-2030 (accessed 2025-07-01).

- IRENA, [International Renewable Energy Agency]. IRENA │ Electricity Capacity Trends. https://public.tableau.com/shared/YZDZRWHB4?:display_count=n&:showVizHome=no# (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Renew Economy. Solar is now being installed faster than any technology in history. https://reneweconomy.com.au/web-stories/solar-is-now-being-installed-faster-than-any-technology-in-history/ (accessed 2025-02-23).

- ANU, [Australian National University]. The fastest energy change in history still underway. ANU RE100 Group. https://re100.eng.anu.edu.au/2024/04/24/fastest-energy-change-article/ (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Becken, S.; Miller, G.; Lee, D. S.; Mackey, B. The Scientific Basis of ‘Net Zero Emissions’ and Its Diverging Sociopolitical Representation. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 918, 170725. [CrossRef]

- IEA, [International Energy Agency]. Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2023 (TCEP 2023). https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-clean-energy-progress-2023 (accessed 2024-07-23).

- Breyer, C.; Bogdanov, D.; Gulagi, A.; Aghahosseini, A.; Barbosa, L. S. N. S.; Koskinen, O.; Barasa, M.; Caldera, U.; Afanasyeva, S.; Child, M.; Farfan, J.; Vainikka, P. On the Role of Solar Photovoltaics in Global Energy Transition Scenarios. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2017, 25 (8), 727–745. [CrossRef]

- Bosco, N. Turn Your Half-Cut Cells for a Stronger Module. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2022, 12 (5), 1149–1153. [CrossRef]

- Waqar Akram, M.; Li, G.; Jin, Y.; Zhu, C.; Javaid, A.; Zuhaib Akram, M.; Usman Khan, M. Study of Manufacturing and Hotspot Formation in Cut Cell and Full Cell PV Modules. Solar Energy 2020, 203, 247–259. [CrossRef]

- Blakers, A. Development of the PERC Solar Cell. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2019, 9 (3), 629–635. [CrossRef]

- Green, M. A. The Passivated Emitter and Rear Cell (PERC): From Conception to Mass Production. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells 2015, 143, 190–197. [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Müller, M.; Wagner, H.; Fischer, G.; Brendel, R.; Altermatt, P. P.; Neuhaus, H. A Roadmap Toward 24% Efficient PERC Solar Cells in Industrial Mass Production. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2017, 7 (6), 1541–1550. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Dai, J.; Xin, S.; Ma, K.; Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Wang, L.; Jin, H.; Tao, W. Thermo-Mechanical Stress Modelling and Fracture Analysis on Ultra-Thin Silicon Solar Cell Based on Super Multi-Busbar PV Modules. Engineering Failure Analysis 2025, 169, 109153. [CrossRef]

- Walter, J.; Tranitz, M.; Volk, M.; Ebert, C.; Eitner, U. Multi-Wire Interconnection of Busbar-Free Solar Cells. Energy Procedia 2014, 55, 380–388. [CrossRef]

- Rendler, L. C.; Kraft, A.; Ebert, C.; Eitner, U.; Wiese, S. Mechanical Stress in Solar Cells with Multi Busbar Interconnection — Parameter Study by FEM Simulation. In 2016 17th International Conference on Thermal, Mechanical and Multi-Physics Simulation and Experiments in Microelectronics and Microsystems (EuroSimE); 2016; pp 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Yue, Q.; Liu, W.; Zhu, X. N-Type Molecular Photovoltaic Materials: Design Strategies and Device Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (27), 11613–11628. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Song, D.; Sun, Z.; Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Rong, D.; Liu, L. A Study on Electrical Performance of N-Type Bifacial PV Modules. Solar Energy 2016, 137, 129–133. [CrossRef]

- Savin, H.; Repo, P.; von Gastrow, G.; Ortega, P.; Calle, E.; Garín, M.; Alcubilla, R. Black Silicon Solar Cells with Interdigitated Back-Contacts Achieve 22.1% Efficiency. Nature Nanotech 2015, 10 (7), 624–628. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, E.; Fong, K.; McIntosh, K.; Fell, A.; Blakers, A.; Kho, T.; Walter, D.; Wang, D.; Zin, N.; Stocks, M.; Wang, E.-C.; Grant, N.; Wan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Z.; Verlinden, P. J. Design, Fabrication and Characterisation of a 24.4% Efficient Interdigitated Back Contact Solar Cell. Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications 2016, 24 (4), 411–427. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, K.; Kawasaki, H.; Yoshida, W.; Irie, T.; Konishi, K.; Nakano, K.; Uto, T.; Adachi, D.; Kanematsu, M.; Uzu, H.; Yamamoto, K. Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cell with Interdigitated Back Contacts for a Photoconversion Efficiency over 26%. Nat Energy 2017, 2 (5), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Kopecek, R.; Libal, J. Bifacial Photovoltaics 2021: Status, Opportunities and Challenges. Energies 2021, 14 (8), 2076. [CrossRef]

- Shen Liang, T.; Pravettoni, M.; Deline, C.; S. Stein, J.; Kopecek, R.; Prakash Singh, J.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; G. Aberle, A.; Sheng Khoo, Y. A Review of Crystalline Silicon Bifacial Photovoltaic Performance Characterisation and Simulation. Energy & Environmental Science 2019, 12 (1), 116–148. [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, E. On the Historical Origins of Bifacial PV Modelling. Solar Energy 2021, 218, 587–595. [CrossRef]

- Alternergy. Bifacial Solar Panels: What are They and Are They Worth It? https://www.alternergy.co.uk/blog/post/bifacial-solar-panels-what-are-they (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Hwang, S.; Lee, H.; Kang, Y. Energy Yield Comparison between Monofacial Photovoltaic Modules with Monofacial and Bifacial Cells in a Carport. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 3148–3153. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. R.; Hanna, A.; Sun, X.; Alam, M. A. Vertical Bifacial Solar Farms: Physics, Design, and Global Optimization. Applied Energy 2017, 206, 240–248. [CrossRef]

- Daliento, S.; De Riso, M.; Guerriero, P.; Matacena, I.; Dhimish, M.; d’Alessandro, V. On the Optimal Orientation of Bifacial Solar Modules. In 2024 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM); 2024; pp 396–400. [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.; Reise, C.; Castro, J. B.; Friesen, G.; Maugeri, G.; Urrejola, E.; Ranta, S. Bifacial Photovoltaic Modules and Systems: Experience and Results from International Research and Pilot Applications; SAND-2021-4835R; IEA-PVPS T13-14:2021; Sandia National Lab. (SNL-NM), Albuquerque, NM (United States); Fraunhofer ISE, Freiburg (Germany); Univ. of Applied Sciences and Arts of Southern Switzerland (SUPSI) (Switzerland); TUV Rheinland, Cologne (Germany); Ricerca sul Sistema Energetico (Italy); ATAMOSTEC (Chile); Turku University of Applied Sciences (Finland), 2021. [CrossRef]

- GVR, [Grand View Research, Inc. ]. Bifacial Solar Market Size, Share and Growth Report, 2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/bifacial-solar-market-report (accessed 2025-02-23).

- MDF, [Market Data Forecast]. Bifacial Solar Market Size, Share, Trends & Growth, 2032. https://www.marketdataforecast.com/market-reports/bifacial-solar-market (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Ineichen, P.; Guisan, O.; Perez, R. Ground-Reflected Radiation and Albedo. Solar Energy 1990, 44 (4), 207–214. [CrossRef]

- Ångström, A. The Albedo of Various Surfaces of Ground. Geografiska Annaler 1925, 7 (4), 323–342. [CrossRef]

- Riedel-Lyngskær, N.; Ribaconka, M.; Pó, M.; Thorseth, A.; Thorsteinsson, S.; Dam-Hansen, C.; Jakobsen, M. L. The Effect of Spectral Albedo in Bifacial Photovoltaic Performance. Solar Energy 2022, 231, 921–935. [CrossRef]

- Russell, T. C. R.; Saive, R.; Augusto, A.; Bowden, S. G.; Atwater, H. A. The Influence of Spectral Albedo on Bifacial Solar Cells: A Theoretical and Experimental Study. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2017, 7 (6), 1611–1618. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Huckaby, E. D. New Weighted Sum of Gray Gases (WSGG) Models for Radiation Calculation in Carbon Capture Simulations: Evaluation and Different Implementation Techniques. In 7th U.S. National Technical Meeting of the Combustion Institute; Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2011; Vol. 4, pp 2483–2496.

- Psiloglou, B. E.; Kambezidis, H. D. Estimation of the Ground Albedo for the Athens Area, Greece. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics 2009, 71 (8), 943–954. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, S. The Albedo of the Ground and Atmosphere. 1948. [CrossRef]

- Atak, E. E.; Elcioglu, E. B.; Ozyurt, T. O. Nanopatterned Silicon Photovoltaic Cells Optimized for Narrowband Selective Reflectivity; Begel House Inc., 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, G.; Hu, P.; Chen, Z.; Jia, L. The Design of Beam Splitter for Two-Stage Reflective Spectral Beam Splitting Concentrating PV/Thermal System. In 2011 Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference; 2011; pp 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Modest, M. F. Radiative Heat Transfer, 2nd ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam Boston, 2003.

- Wall, T. F.; Becker, H. B. Total Absorptivities and Emissivities of Particulate Coal Ash From Spectral Band Emissivity Measurements. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power 1984, 106 (4), 771–776. [CrossRef]

- Boyden, S. B.; Zhang, Y. Temperature and Wavelength-Dependent Spectral Absorptivities of Metallic Materials in the Infrared. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 2006, 20 (1), 9–15. [CrossRef]

- Shayegan, K. J.; Hwang, J. S.; Zhao, B.; Raman, A. P.; Atwater, H. A. Broadband Nonreciprocal Thermal Emissivity and Absorptivity. Light Sci Appl 2024, 13 (1), 176. [CrossRef]

- Howell, J. R.; Mengüc, M. P.; Daun, K.; Siegel, R. Thermal Radiation Heat Transfer, 7th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Howell, J. R.; Perlmutter, M. Directional Behavior of Emitted and Reflected Radiant Energy from a Specular, Gray, Asymmetric Groove; Technical Note NASA TN D-1874; NASA [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration]: Cleveland, Ohio, 1963. https://books.google.com.om/books?id=e8x3rqdSt3QC.

- Zhou, L.; Dickinson, R. E.; Tian, Y.; Zeng, X.; Dai, Y.; Yang, Z.-L.; Schaaf, C. B.; Gao, F.; Jin, Y.; Strahler, A.; Myneni, R. B.; Yu, H.; Wu, W.; Shaikh, M. Comparison of Seasonal and Spatial Variations of Albedos from Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Common Land Model. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2003, 108 (D15). [CrossRef]

- Brest, C. L. Seasonal Albedo of an Urban/Rural Landscape from Satellite Observations. 1987, 26 (9), 1169–1187. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Davidson, A. Impact of Climate Variations on Surface Albedo of a Temperate Grassland. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology 2007, 142 (2), 133–142. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, T. M.; Germino, M. J.; Romero, S.; Porensky, L. M.; Blumenthal, D. M.; Brown, C. S.; Adler, P. B. Experimental Manipulation of Soil-Surface Albedo Alters Phenology and Growth of Bromus Tectorum (Cheatgrass). Plant Soil 2023, 487 (1), 325–339. [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Park, K. Contribution of Greening and High-Albedo Coatings to Improvements in the Thermal Environment in Complex Urban Areas. Advances in Meteorology 2015, 2015 (1), 792172. [CrossRef]

- Gul, M.; Kotak, Y.; Muneer, T.; Ivanova, S. Enhancement of Albedo for Solar Energy Gain with Particular Emphasis on Overcast Skies. Energies 2018, 11 (11), 2881. [CrossRef]

- Sellers, W. D. Physical Climatology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, Illinois, USA, 1965.

- Xiao, B.; Bowker, M. A. Moss-Biocrusts Strongly Decrease Soil Surface Albedo, Altering Land-Surface Energy Balance in a Dryland Ecosystem. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 741, 140425. [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Gul, M. S.; Muneer, T. Performance Analysis and Comparison between Bifacial and Monofacial Solar Photovoltaic at Various Ground Albedo Conditions. Renewable Energy Focus 2023, 44, 295–316. [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, R. E.; Hanson, B. Vegetation-Albedo Feedbacks. In Climate Processes and Climate Sensitivity; American Geophysical Union (AGU), 1984; pp 180–186. [CrossRef]

- Schwaiger, H. P.; Bird, D. N. Integration of Albedo Effects Caused by Land Use Change into the Climate Balance: Should We Still Account in Greenhouse Gas Units? Forest Ecology and Management 2010, 260 (3), 278–286. [CrossRef]

- Shoukry, I.; Libal, J.; Kopecek, R.; Wefringhaus, E.; Werner, J. Modelling of Bifacial Gain for Stand-Alone and in-Field Installed Bifacial PV Modules. Energy Procedia 2016, 92, 600–608. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Manikandan, S. Experimental Study and Model Development of Bifacial Photovoltaic Power Plants for Indian Climatic Zones. Energy 2023, 284, 128693. [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Roesler, J.; King, D. Albedo Estimation of Finite-Sized Concrete Specimens. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 2019, 47 (2), 738–757. [CrossRef]

- Trina Solar. Vertex Bifacial Dual Glass Monocrystalline Module; Datasheet TSM_EN_2022_A; LG Electronics Inc.: Changzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, 2022. https://static.trinasolar.com/sites/default/files/Datasheet_Vertex_DEG21C.20_EN_2022_A_0.pdf (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Adani Solar. Adani Solar ELAN PRIDE Series MBB P-Type PERC Half-Cut Bifacial PV Modules; Datasheet; India, 2025; pp 1–2. https://www.adanisolar.com/-/media/Project/AdaniSolar/Downloads/pdf/newdatasheet1/Pride-G2G-modules.pdf (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Abe, C. F.; Batista Dias, J.; Notton, G.; Faggianelli, G.-A.; Pigelet, G.; Ouvrard, D. Estimation of the Effective Irradiance and Bifacial Gain for PV Arrays Using the Maximum Power Current. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2023, 13 (3), 432–441. [CrossRef]

- Kreinin, L.; Karsenty, A.; Grobgeld, D.; Eisenberg, N. PV Systems Based on Bifacial Modules: Performance Simulation vs. Design Factors. In 2016 IEEE 43rd Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC); 2016; pp 2688–2691. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P. K.; Batzelis, E. I.; Roy, J. N.; Chakraborty, C. Irradiance Effect on the Bifaciality Factors of Bifacial PV Modules. In 2022 IEEE 1st Industrial Electronics Society Annual On-Line Conference (ONCON); 2022; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Lee, H.; Kang, Y. Bifacial Module Characterization Analysis with Current Mismatched PERC Cells. J. Korean Phys. Soc. 2024, 84 (2), 145–150. [CrossRef]

- SunSolve. SunSolveTM - When Accuracy Matters. https://sunsolve.info (accessed 2025-02-24).

- Raina, G.; Sinha, S. A Simulation Study to Evaluate and Compare Monofacial Vs Bifacial PERC PV Cells and the Effect of Albedo on Bifacial Performance. Materials Today: Proceedings 2021, 46, 5242–5247. [CrossRef]

- PVsyst. PVsyst documentation - References. https://www.pvsyst.com/help/references.html (accessed 2025-02-23).

- PVsyst. PVsyst documentation - Overview. https://www.pvsyst.com/help/ (accessed 2025-02-23).

- PVsyst. PVsyst │ Shop. https://www.pvsyst.com/shop-prices (accessed 2025-02-23).

- Su, X.; Luo, C.; Chen, X.; Ji, J.; Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zou, W. Numerical Modeling of All-Day Albedo Variation for Bifacial PV Systems on Rooftops and Annual Yield Prediction in Beijing. Build. Simul. 2024, 17 (6), 955–964. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A. S. Sustainable and Efficient Electricity Tariffs – A Case Study of Oman. Saudi J. Eng. Technol. 2022, 7 (3), 118–127. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Multi-Physics Mathematical Model of Weakly-Ionized Plasma Flows. American Journal of Modern Physics 2018, 7 (2), 87–102. [CrossRef]

- OPWP, [Oman Power and Water Procurement Company]. OPWP’s 7-YEAR STATEMENT (2021 – 2027) (Issue 15); OPWP [Oman Power and Water Procurement Company]: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2022. https://omanpwp.om/PDFAR/7%20Year%20Statement%20Issue%2015%202021%20-%202027.pdf (accessed 2022-09-12).

- Marzouk, O. A. Combined Oxy-Fuel Magnetohydrodynamic Power Cycle. In Conference on Energy Challenges in Oman (ECO’2015); DU [Dhofar University]: Salalah, Dhofar, Oman, 2015.

- Marzouk, O. A. Cantera-Based Python Computer Program for Solving Steam Power Cycles with Superheating. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering 2023, 13 (3), 63–73.

- IEA, [International Energy Agency]. Oman’s fossil fuel expertise could help drive clean energy transitions, new report shows - News. https://www.iea.org/news/oman-s-fossil-fuel-expertise-could-help-drive-clean-energy-transitions-new-report-shows (accessed 2025-03-06).

- Om2040U, [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]. Oman 2040 Vision Document; Om2040U [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2020. https://www.oman2040.om/VisionDocument?lang=en (accessed 2023-10-06).

- Marzouk, O. A. In the Aftermath of Oil Prices Fall of 2014/2015–Socioeconomic Facts and Changes in the Public Policies in the Sultanate of Oman. International Journal of Management and Economics Invention 2017, 3 (11), 1463–1479. [CrossRef]

- Birks, J. S.; Sinclair, C. A. Successful Education and Human Resource Development - The Key to Sustained Economic Growth*. In Oman: Economic, Social and Strategic Developments; Pridham, B. R., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 1987.

- Marzouk, O. A. Utilizing Co-Curricular Programs to Develop Student Civic Engagement and Leadership. The Journal of the World Universities Forum 2008, 1 (5), 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. English Programs for Non-English Speaking College Students. In 1st Knowledge Globalization Conference 2008 (KGLOBAL 2008); Sawyer Business School, Suffolk University: Boston, Massachusetts, USA, 2008; pp 1–8.

- Yahia, H. A. M.; Al-Shukaili, A. M.; Manchiryal, R. K.; Eissa, T.; Mohammed, A. A. Strategic Planning for the Development of Smart Cities in Oman. In The Emerald Handbook of Smart Cities in the Gulf Region: Innovation, Development, Transformation, and Prosperity for Vision 2040; Lytras, M. D., Alkhaldi, A., Malik, S., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, England, UK, 2024; pp 289–304. [CrossRef]

- Om2040U, [Oman Vision 2040 Implementation Follow-up Unit]. Oman Vision 2040 │ Follow-up System. https://www.oman2040.om/organization?lang=en (accessed 2024-07-30).

- Al Farsi, W. A.; Achuthan, G. Analysis of Effectiveness of Smart City Implementation in Transportation Sector in Oman. In 2018 Majan International Conference (MIC); 2018; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Recommended LEED-Compliant Cars, SUVs, Vans, Pickup Trucks, Station Wagons, and Two Seaters for Smart Cities Based on the Environmental Damage Index (EDX) and Green Score. In Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7; Ben Ahmed, M., Boudhir, A. A., El Meouche, R., Karaș, İ. R., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Vol. 906, pp 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Brebbia, C. A.; Longhurst, J.; Marco, E.; Booth, C. Sustainable Development and Planning IX; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2017.

- Scholz, W.; Langer, S. Spatial Development of Muscat/Oman and Challenges of Public Transport. In Gulf Research Meeting 2016; Future Cities Laboratory Singapore; ETH Zurich: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp 40–67. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kalbani, M. S.; Price, M. F.; O’Higgins, T.; Ahmed, M.; Abahussain, A. Integrated Environmental Assessment to Explore Water Resources Management in Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Sultanate of Oman. Reg Environ Change 2016, 16 (5), 1345–1361. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismaily, H. A.; Probert, D. Photovoltaic Electricity Prospects in Oman. Applied Energy 1998, 59 (2), 97–124. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Benchmarking the Trends of Urbanization in the Gulf Cooperation Council: Outlook to 2050. In 1st National Symposium on Emerging Trends in Engineering and Management (NSETEM’2017); WCAS [Waljat College of Applied Sciences], Muscat, Oman, 2017; pp 1–9.

- MEM, [Ministry of Energy and Minerals in the Sultanate of Oman]. MEM │ Green Hydrogen in Oman; Public Announcement; MEM [Ministry of Energy and Minerals in the Sultanate of Oman]: Muscat, Sultanate of Oman, 2022; pp 1–15. https://hydrom.om/events/hydromlaunch/221023_MEM_En.pdf (accessed 2023-10-06).

- Hydrom, [Hydrogen Oman]. About Us (Hydrom : Hydrogen Oman). https://hydrom.om/Hydrom.aspx?cms=iQRpheuphYtJ6pyXUGiNqiQQw2RhEtKe#about (accessed 2024-07-30).

- Zghaibeh, M.; Barhoumi, E. M.; Okonkwo, P. C.; Ben Belgacem, I.; Beitelmal, W. H.; Mansir, I. B. Analytical Model for a Techno-Economic Assessment of Green Hydrogen Production in Photovoltaic Power Station Case Study Salalah City-Oman. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47 (31), 14171–14179. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wen, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, B.; Jiang, L. Water Electrolyzer Operation Scheduling for Green Hydrogen Production: A Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 203, 114779. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Xue, J.; Gao, H.; Ma, N. Hydrogen-Fueled Gas Turbines in Future Energy System. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 569–582. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Validating a Model for Bluff-Body Burners Using the HM1 Turbulent Nonpremixed Flame. Journal of Advanced Thermal Science Research 2016, 3 (1), 12–23. [CrossRef]

- Mariyam, S.; Alherbawi, M.; McKay, G.; Al-Ansari, T. Converting Waste into Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF): A Systematic Literature Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2026, 226, 116380. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Qin, Q. Evaluation of Sustainable Aviation Fuel Based on Life Cycle Prediction Model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 2026, 224, 108565. [CrossRef]

- Lau, J. I. C.; Wang, Y. S.; Ang, T.; Seo, J. C. F.; Khadaroo, S. N. B. A.; Chew, J. J.; Ng Kay Lup, A.; Sunarso, J. Emerging Technologies, Policies and Challenges toward Implementing Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). Biomass and Bioenergy 2024, 186, 107277. [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Breyer, C. Global Production Potential of Green Methanol Based on Variable Renewable Electricity. Energy & Environmental Science 2024, 17 (10), 3503–3522. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Pan, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, L.; Zheng, C.; Cha, S. W.; Zhong, Z. Scientometric Analysis of Research Trends on Solid Oxide Electrolysis Cells for Green Hydrogen and Syngas Production. Front. Energy 2024, 18 (5), 583–611. [CrossRef]

- Bora, N.; Kumar Singh, A.; Pal, P.; Kumar Sahoo, U.; Seth, D.; Rathore, D.; Bhadra, S.; Sevda, S.; Venkatramanan, V.; Prasad, S.; Singh, A.; Kataki, R.; Kumar Sarangi, P. Green Ammonia Production: Process Technologies and Challenges. Fuel 2024, 369, 131808. [CrossRef]

- Salman, H. Buraimi Dispute. In Global Encyclopedia of Territorial Rights; Gray, K. W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp 1–11. [CrossRef]

- OQ8, [Duqm Refinery and Petrochemical Industries Company]. About Duqm. https://www.oq8.om/about-oq8/about-duqm (accessed 2024-08-06).

- Al Farsi, A.; Dhanalekshmi, U. M.; Alam, T.; Althani, G. S.; Al-Ruqaishi, H. K.; Khan, S. A. Chemical Profiling and In Vitro Biological Evaluation of the Essential Oil of Caralluma Arabica from IBRI, Oman. Chem Nat Compd 2023, 59 (3), 594–596. [CrossRef]

- Accessibility To The Historic Defence Sites Of Oman For People With Mobility Impairment: The Cases Of The Nakhal, Al Hazm And Khasab Fortifications.

- Benz, M. Musandam and Its Trade with Iran. Regional Linkages Across the Strait of Hormuz. In Regionalizing Oman: Political, Economic and Social Dynamics; Wippel, S., Ed.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2013; pp 205–216. [CrossRef]

- Nebel, S.; Richthofen, A. von. Urban Oman: Trends and Perspectives of Urbanisation in Muscat Capital Area; LIT Verlag Münster, 2016.

- Prathapar, S. A.; Khan, M.; Mbaga, M. D. The Potential of Transforming Salalah into Oman’s Vegetables Basket. In Environmental Cost and Face of Agriculture in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries; Shahid, S. A., Ahmed, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; pp 83–94. [CrossRef]

- Kazem, H. A.; Khatib, T. Techno-Economical Assessment of Grid Connected Photovoltaic Power Systems Productivity in Sohar, Oman. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2013, 3, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Madayn. Suhar Industrial City. https://www.madayn.om/EN/Pages/Sohar.aspx (accessed 2025-02-26).

- Freezone, S. P. and. Sohar Port and Freezone. http://www.soharportandfreezone.com (accessed 2025-02-26).

- Suhar Airport. Tourism Guide Clone - Suhar Airport. https://www.suharairport.co.om/content/tourism-guide-clone (accessed 2025-02-26).

- Al Fazari, H. Higher Education in the Arab World: Research and Development from the Perspective of Oman and Sohar University. In Higher Education in the Arab World: Research and Development; Badran, A., Baydoun, E., Hillman, J. R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp 259–274. [CrossRef]

- Mesa-Jiménez, J. J.; Tzianoumis, A. L.; Stokes, L.; Yang, Q.; Livina, V. N. Long-Term Wind and Solar Energy Generation Forecasts, and Optimisation of Power Purchase Agreements. Energy Reports 2023, 9, 292–302. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Changes in Fluctuation Waves in Coherent Airflow Structures with Input Perturbation. WSEAS Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 4 (10), 604–614.

- Marzouk, O. A. Directivity and Noise Propagation for Supersonic Free Jets. In 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-23. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Accurate Prediction of Noise Generation and Propagation. In 18th Engineering Mechanics Division Conference of the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE-EMD); Zenodo: Blacksburg, Virginia, USA, 2007; pp 1–6.

- Dupraz, C. Assessment of the Ground Coverage Ratio of Agrivoltaic Systems as a Proxy for Potential Crop Productivity. Agroforest Syst 2024, 98 (8), 2679–2696. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Detailed Characteristics of the Resonating and Non-Resonating Flows Past a Moving Cylinder. In 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-2311. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A.; Nayfeh, A. H. Simulation, Analysis, and Explanation of the Lift Suppression and Break of 2:1 Force Coupling Due to in-Line Structural Vibration. In 49th AIAA/ASME/ASCE/AHS/ASC Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference; AIAA [American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics]: Schaumburg, Illinois, USA, 2008; p AIAA 2008-2309. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Investigation of Strouhal Number Effect on Acoustic Fields. In 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007); INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 1056–1067.

- Marzouk, O. A. Noise Emissions from Excited Jets. In 22nd National Conference on Noise Control Engineering (NOISE-CON 2007); INCE [Institute of Noise Control Engineering]: Reno, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 1034–1045.

- Shen, W.; Chen, X.; Qiu, J.; Hayward, J. A.; Sayeef, S.; Osman, P.; Meng, K.; Dong, Z. Y. A Comprehensive Review of Variable Renewable Energy Levelized Cost of Electricity. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2020, 133, 110301. [CrossRef]

- Rana, G. S.; Jindal, R. Factors Affecting Solar Levelized Cost of Electricity in India & Policy Recommendations. Energy and Climate Change 2025, 6, 100207. [CrossRef]

- Kessler, W. Comparing Energy Payback and Simple Payback Period for Solar Photovoltaic Systems. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 00080. [CrossRef]

- Czipf, C. The Impact of Changing Energy Prices, Interest Rates, and Investment Costs on the Net Present Value and Internal Rate of Return for Alternative Energy Projects. Discov Sustain 2025, 6 (1), 161. [CrossRef]

- Hartman, J. C.; Schafrick, I. C. The Relevant Internal Rate of Return. The Engineering Economist 2004, 49 (2), 139–158. [CrossRef]

- Bae, G.; Yoon, A.; Kim, S. Incentive Determination for Demand Response Considering Internal Rate of Return. Energies 2024, 17 (22), 5660. [CrossRef]

- Gallo, A. A Refresher on Net Present Value. Harvard Business Review. November 19, 2014, pp 1–3.

- Rostami, S.; Creemers, S.; Leus, R. Maximizing the Net Present Value of a Project under Uncertainty: Activity Delays and Dynamic Policies. European Journal of Operational Research 2024, 317 (1), 16–24. [CrossRef]

- Alsadi, S.; Khatib, T. Photovoltaic Power Systems Optimization Research Status: A Review of Criteria, Constrains, Models, Techniques, and Software Tools. Applied Sciences 2018, 8 (10), 1761. [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Thermo Physical Chemical Properties of Fluids Using the Free NIST Chemistry WebBook Database. Fluid Mechanics Research International Journal 2017, 1 (1). [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, O. A. Airfoil Design Using Genetic Algorithms. In The 2007 International Conference on Scientific Computing (CSC’07), The 2007 World Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, and Applied Computing (WORLDCOMP’07); CSREA Press: Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 2007; pp 127–132.

- Valko, N. V.; Kushnir, N. O.; Osadchyi, V. V. Cloud Technologies for STEM Education; [б. в.], 2020. [CrossRef]

- Chu, W. W.; Hafiz, N. R. M.; Mohamad, U. A.; Ashamuddin, H.; Tho, S. W. A Review of STEM Education with the Support of Visualizing Its Structure through the CiteSpace Software. Int J Technol Des Educ 2023, 33 (1), 39–61. [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Ding, X.; Jiang, R. Using Computer Graphics to Make Science Visible in Engineering Education. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 2023, 43 (5), 99–106. [CrossRef]

- IFI, [Institute for Future Intelligence, Inc. ]. Institute for Future Intelligence │ Journal Papers. https://www.intofuture.org/journals.html (accessed 2025-03-01).

- Xie, C.; Schimpf, C.; Chao, J.; Nourian, S.; Massicotte, J. Learning and Teaching Engineering Design through Modeling and Simulation on a CAD Platform. Comp Applic In Engineering 2018, 26 (4), 824–840. [CrossRef]

- Ukoima, K. N.; Efughu, D.; Azubuike, O. C.; Akpiri, B. F. Investigating the Optimal Photovoltaic (PV) Tilt Angle Using the Photovoltaic Geographic Information System (PVGIS). Nigerian Journal of Technology 2024, 43 (1), 101–114. [CrossRef]

- EC, [European Commission]. PVGIS │ User Manual. https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/photovoltaic-geographical-information-system-pvgis/getting-started-pvgis/pvgis-user-manual_en (accessed 2025-03-01).

- Psomopoulos, C. S.; Ioannidis, G. Ch.; Kaminaris, S. D.; Mardikis, K. D.; Katsikas, N. G. A Comparative Evaluation of Photovoltaic Electricity Production Assessment Software (PVGIS, PVWatts and RETScreen). Environ. Process. 2015, 2 (1), 175–189. [CrossRef]

- Sauer, K. J.; Roessler, T.; Hansen, C. W. Modeling the Irradiance and Temperature Dependence of Photovoltaic Modules in PVsyst. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2015, 5 (1), 152–158. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Kumar, N.; Chandel, S. S. Simulation and Performance Analysis of a 1kWp Photovoltaic System Using PVsyst. In 2015 International Conference on Computation of Power, Energy, Information and Communication (ICCPEIC); 2015; pp 0358–0363. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, C. P.; Prabu, P.; Niruba, K. Solar Potential Assessment Using PVSYST Software. In 2013 International Conference on Green Computing, Communication and Conservation of Energy (ICGCE); 2013; pp 667–672. [CrossRef]

- Deniz, M. Analysis of Accessibility to Public Schools with GIS: A Case Study of Salihli City (Turkey). Children’s Geographies 2024, 22 (1), 30–51. [CrossRef]

- Özen, T.; Bülbül, A.; Tarcan, G. Reservoir and Hydrogeochemical Characterizations of Geothermal Fields in Salihli, Turkey. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences 2012, 60, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Ozgener, L.; Hepbasli, A.; Dincer, I. Energy and Exergy Analysis of Salihli Geothermal District Heating System in Manisa, Turkey. International Journal of Energy Research 2005, 29 (5), 393–408. [CrossRef]

- JinkoSolar. Case Study │ Witznitz Energy Park 650 MW, Germany. https://jinkosolar.eu/case-study/witznitz-energy-park-650-mw-germany (accessed 2025-03-04).

- Smith, B.; Woodhouse, M.; Feldman, D.; Margolis, R. Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Manufacturing Expansions in the United States, 2017-2019: Motives, Challenges, Opportunities, and Policy Context; Technical Report NREL/TP-6A20-74807; NREL [United States National Renewable Energy Laboratory]: Golden, Colorado, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, I. H.; Kemery, B. P.; Beausoleil-Morrison, I. Optimal Solar-PV Tilt Angle and Azimuth: An Ontario (Canada) Case-Study. Energy Policy 2011, 39 (3), 1397–1409. [CrossRef]

- Etukudor, C.; Orovwode, H.; Wara, S.; Agbetuyi, F.; Adozhe, A.; Obieje, B. O.; Oparaocha, C. N. Optimum Tilt and Azimuth Angles for Solar Photovoltaic Systems in South-West Nigeria. In 2018 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica; 2018; pp 348–353. [CrossRef]

- Brecl, K.; Topič, M. Self-Shading Losses of Fixed Free-Standing PV Arrays. Renewable Energy 2011, 36 (11), 3211–3216. [CrossRef]

- Nicolás-Martín, C.; Eleftheriadis, P.; Santos-Martín, D. Validation and Self-Shading Enhancement for SoL: A Photovoltaic Estimation Model. Solar Energy 2020, 202, 386–408. [CrossRef]

- Flores-Hernández, D. A.; Palomino-Resendiz, S.; Lozada-Castillo, N.; Luviano-Juárez, A.; Chairez, I. Mechatronic Design and Implementation of a Two Axes Sun Tracking Photovoltaic System Driven by a Robotic Sensor. Mechatronics 2017, 47, 148–159. [CrossRef]

- Salgado-Conrado, L.; Lopez-Montelongo, A.; Alvarez-Macias, C.; Hernadez-Jaquez, J. Review of Heliodon Developments and Computational Tools for Building Shadow Analysis. Buildings 2022, 12 (5), 627. [CrossRef]

- Mikhael, M. G.; Metwaly, M. A Simple Heliodon System for Horizontal Placed Models. Journal of Contemporary Urban Affairs 2017, 1 (3), 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Pinker, R. T.; Militana, L. M. The Asymmetry of Global Solar Radiation Around Solar Noon. 1988.

- Pereira, A. B.; Villa Nova, N. A.; Galvani, E. Estimation of Global Solar Radiation Flux Density in Brazil from a Single Measurement at Solar Noon. Biosystems Engineering 2003, 86 (1), 27–34. [CrossRef]

- Chippindale, C. Stoned Henge: Events and Issues at the Summer Solstice, 1985. World Archaeology 1986, 18 (1), 38–58. [CrossRef]

- Sojka, J. J.; Schunk, R. W. A Theoretical Study of the Global F Region for June Solstice, Solar Maximum, and Low Magnetic Activity. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics 1985, 90 (A6), 5285–5298. [CrossRef]

- Myrabø, H. K. Temperature Variation at Mesopause Levels during Winter Solstice at 78°N. Planetary and Space Science 1984, 32 (2), 249–255. [CrossRef]

- Trolle, A. K. Winter Solstice Celebrations in Denmark: A Growing Non-Religious Ritualisation. Religions 2021, 12 (2), 74. [CrossRef]

- Borfecchia, F.; Caiaffa, E.; Pollino, M.; De Cecco, L.; Martini, S.; La Porta, L.; Marucci, A. Remote Sensing and GIS in Planning Photovoltaic Potential of Urban Areas. European Journal of Remote Sensing 2014, 47 (1), 195–216. [CrossRef]

- Gawley, D.; McKenzie, P. Investigating the Suitability of GIS and Remotely-Sensed Datasets for Photovoltaic Modelling on Building Rooftops. Energy and Buildings 2022, 265, 112083. [CrossRef]

- Türkdoğru, E.; Kutay, M. Analysis of Albedo Effect in a 30-kW Bifacial PV System with Different Ground Surfaces Using PVsyst Software. Journal of Energy Systems 2022, 6 (4), 543–559. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Winston, D. P.; Sugumar, S.; Jegan, S. Performance Analysis of N-Type PERT Bifacial Solar PV Module under Diverse Albedo Conditions. Solar Energy 2023, 252, 81–90. [CrossRef]

- Ghenai, C.; Ahmad, F. F.; Rejeb, O.; Bettayeb, M. Artificial Neural Networks for Power Output Forecasting from Bifacial Solar PV System with Enhanced Building Roof Surface Albedo. Journal of Building Engineering 2022, 56, 104799. [CrossRef]

- Unxos GmbH. GeoNames - geographical database. https://www.geonames.org/advanced-search.html (accessed 2021-09-22).

- Öçal, M. F.; Şimşek, M.; Kapucu, S. Measuring the Height of a Flag Pole Using Smartphone GPS and Orientation Sensors. PRIMUS 2021, 31 (9), 1007–1019. [CrossRef]

- EC, [European Commission]. PVGIS │ Data sources and calculation methods. https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/photovoltaic-geographical-information-system-pvgis/getting-started-pvgis/pvgis-data-sources-calculation-methods_en (accessed 2025-03-03).

- OPG, [Oman Pocket Guide]. Khasab, Musandam. https://omanpocketguide.com/khasab-musandam (accessed 2025-03-03).

- Searle, M. Musandam Peninsula and Straits of Hormuz. In Geology of the Oman Mountains, Eastern Arabia; Searle, M., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; pp 129–146. [CrossRef]

- OPWP, [Oman Power and Water Procurement Company]. Solar Data - Weather Impact Analysis; OPWP [Oman Power and Water Procurement Company]: Muscat, Oman, 2013. https://omanpwp.om/PDF/Solar%20Data%20-%20Weather%20Impact%20Analysis.pdf (accessed 2021-11-03).

- Bierman, B.; Treynor, C.; O’Donnell, J.; Lawrence, M.; Chandra, M.; Farver, A.; Von Behrens, P.; Lindsay, W. Performance of an Enclosed Trough EOR System in South Oman. Energy Procedia 2014, 49, 1269–1278. [CrossRef]

- NASA, [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration]. Earth Observatory │ Aerosol Optical Depth. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/global-maps/MODAL2_M_AER_OD (accessed 2025-04-25).

- NASA, [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration]. Earth Observatory │ Aerosol Size & Aerosol Optical Depth. https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/global-maps/MODAL2_M_AER_RA/MODAL2_M_AER_OD (accessed 2025-04-25).

- NASA, [United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration]. Ozone, Aerosol, Trace Gases │ Ozone & Atmospheric Composition. https://ozoneaq.gsfc.nasa.gov/map/#d:2024-05-02..2024-05-31,2024-05-02;l:country-outline,aura_aerosol,earth;@55.8,21.7,6.0z (accessed 2025-04-25).

- Okonkwo, P. C.; Barhoumi, E. M.; Murugan, S.; Zghaibeh, M.; Otor, C.; Abo-Khalil, A. G.; Amer Mohamed, A. M. Economic Analysis of Cross-Breed Power Arrangement for Salalah Region in the Al-Khareef Season. International Journal of Sustainable Energy 2021, 40 (2), 188–206. [CrossRef]

- Carr, C. M.; Yavary, M.; Yavary, M. Wave Agitation Studies for Port Expansion - Salalah, Oman. 2012, 1–10. [CrossRef]

| Ground / Foundation characteristics | Albedo value | Reference |

| perfectly black surface | 0 | [64] |

| back road pavement | 0.05-0.10 | [65] |

| dark soil | 0.05-0.15 | [65] |

| green meadows | 0.10-0.20 | [65] |

| grassland | 0.1 | [66] |

| dark-colored soil surfaces | 0.1-0.2 | [66] |

| soil surface | 0.10–0.15 | [67] |

| crops | 0.15-0.25 | [65] |

| concrete | 0.17-0.27 | [65] |

| savanna and grassland | Below 0.18 | [68] |

| grassland | 0.2 | [69] |

| bare ground | 0.2 | [64] |

| desert | 0.25-0.30 | [65] |

| cement foundation surrounded by sand | 0.3 | [70] |

| average ground albedo | 0.3 | [71] |

| concrete | 0.30–0.35 | [67] |

| dune sand | 0.35-0.45 | [65] |

| sand | 0.4 | [64] |

| white pebbles | 0.5-0.6 | [64,67] |

| concrete | 0.50-0.55 | [72] |

| white tiles | 0.7–0.8, | [67] |

| fresh snow | 0.75-0.95 | [65] |

| highly reflective material (mirror or white surface, capable of total reflection) | 1 | [64] |

| Characteristics | Used value |

| Total nominal (peak) power capacity | 4.5 kWp |

| DC-to-AC ratio | 1.14* |

| Pole height | 1.35 m |

| Pole spacing | 3.00 m |

| Mounting type | Ground mounting |

| Solar tracking | None (fixed orientation) |

| Aladdin energy analysis option: sampling frequency | 30 samples per hour (the highest available value) |

| Inverter efficiency | 98%** |

| Bifacial PV module | Jinko Solar Tiger LM 72HC-BDVP*** (Monocrystalline cells, 72 cells as 144 half-cut cells per module) |

| Bifacial PV module type and nameplate DC power | JKM450M-72HLM-BDVP (450 Wp) |

| Number of bifacial PV modules | 10 |

| Monofacial PV module | Jinko Solar Eagle PERC 60M (Monocrystalline cells, 60 cells per module) |

| Monofacial PV module type and nameplate DC power | JKM300M-60 (300 Wp)**** |

| Number of bifacial PV modules | 15 |

| * In the external study used here for bifacial benchmarking cases, the reported DC-to-AC ratio was 1.13 (computed as 34.00 kWp ÷ 30.00 kWac = 1.1333). Here, the DC-to-AC ratio is slightly increased to 1.14 to have the same inverter’s nominal AC power of 30.00 kWac of the external benchmarking cases despite the PV nominal peak power here being 34.20 kWp (rather than 34.00 kWp). Thus, the entered DC-to-AC ratio in our Aladdin simulation is computed as 34.20 kWac ÷ 30.00 kWp = 1.1400). This value (1.14) is then retained in all other main simulations (the simulations dedicated to obtaining data for the seven Omani cities, not for benchmarking in the Turkish site of Salihli). ** This inverter efficiency was estimated from the external study for the bifacial benchmarking cases, as the quotient of dividing 65,038 kWh (AC output energy from the inverter stage, available for addition into the grid) by 66,229 kWh (DC output energy from PV array). This quotient is 0.9820. In Aladdin, the resolution that could be recognized as a user’s input value for this parameter was 0.01 (two digits after the decimal point). Thus, the value of 0.98 (rather than 0.9820) was used after rounding to two decimal places. *** In the external study for the bifacial benchmarking cases, the bifacial module was GG1H-425 Bifacial PERC-72 by the Turkish PV manufacturer GTC. This exact type was not available in the online energy modeling software “Aladdin” at the time of conducting this study. Thus, an alternative model was used with proper adjustments in the number of PV panels and DC-to-AC ratio to make the modeled bifacial PV system equivalent to the one in the external study. **** This choice of the PV module type (JKM300M-60) allows us to construct a reference monofacial PV system with the exact DC power capacity of the bifacial system (given that: 10 modules × 450 Wp “bifacial” = 15 modules × 300 Wp “monofacial”). Also, the use of the same manufacturer (Jinko Solar) as the bifacial PV system we model is encouraged for more consistency. | |

| Characteristics | Used value |

| Location | Caferbey (community/village), Salihli (municipality/district), Manisa (province), Turkey |

| Latitude (degree, minute, second – DMS) | N 38°28'38" |

| Longitude (degree, minute, second – DMS) | E 28°5'50" |

| Latitude (decimal degree – DD) | 38.4772° N |

| Longitude (decimal degree – DD) | 28.0972° E |

| Tilt | 30° (year-round optimum) |

| Azimuth angle | 180° from north (0° from south) |

| Row-to-row spacing (inter-row spacing, or array pitch) | 5 m |

| PV nameplate power capacity | 34.2 kWp (in the external study, 80 bifacial modules “GG1H-425 Bifacial PERC-72” by the Turkish PV manufacturer GTC were modeled in PVsyst, thus the nominal PV power was 34.00 kWp; here the modeled nominal PV power in Aladdin is 34.20 kWp, as 76 modules with 0.450 kWp each) |

| Inverter nameplate power capacity | 30 kWac (in the external study, this is obtained as: 34.00 kWp ÷ 1.1333; here, it is obtained as: 34.20 kWp ÷ 1.1400) |

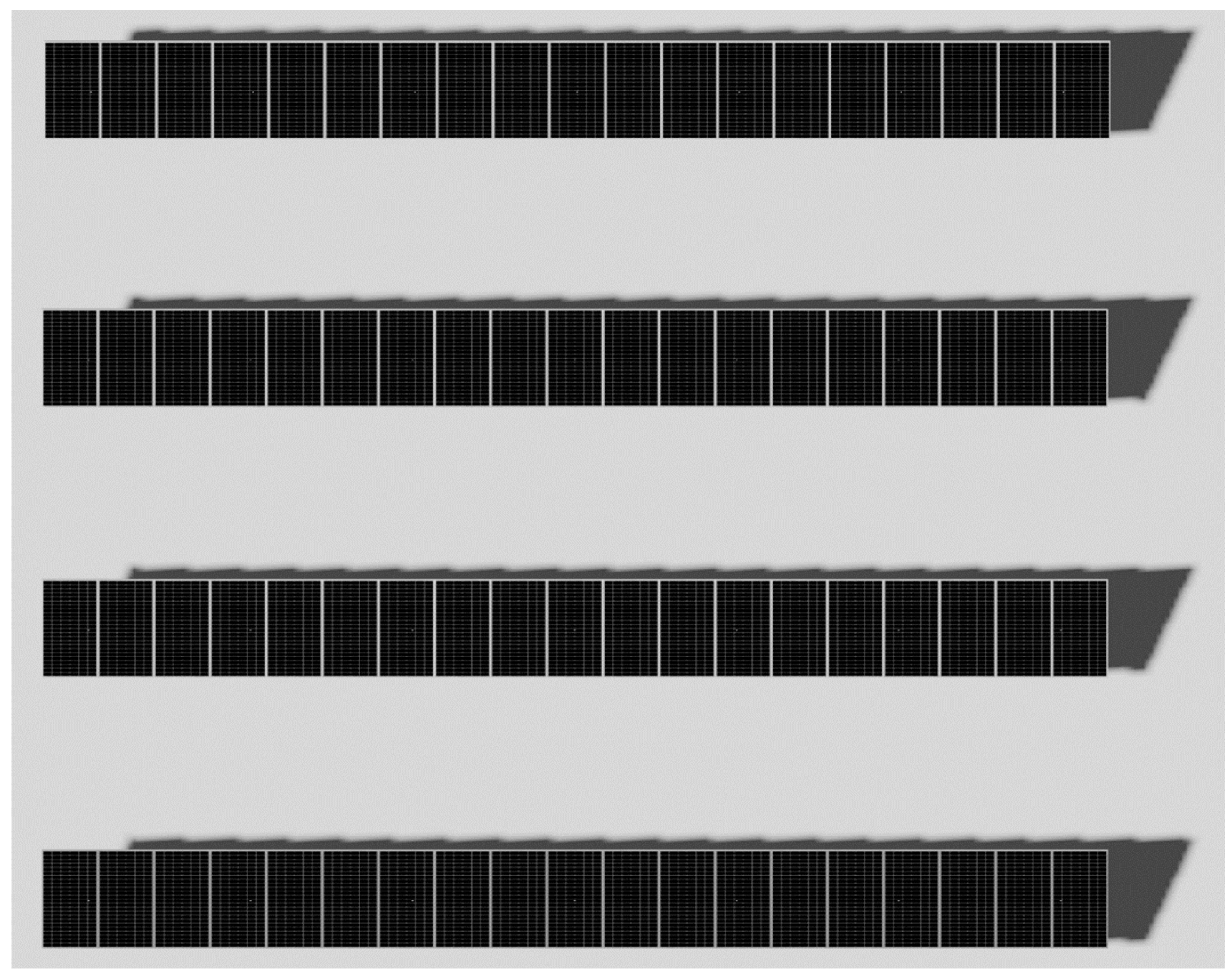

| Number of rows of PV array | 4 (in the external study, 20 PV modules are stacked horizontally in each row; here, 19 PV modules are stacked horizontally in each row) |

| Albedo | 0.30 (for the low-albedo simulation) 0.65 (for the high-albedo simulation) |

| Albedo | Total annual electric yield (our study) | Total annual electric yield (external study) | Difference in total electric yield (our value – external value) | Averaged total electric yield | Relative deviation (difference÷average)×100% |

| 0.30 | 60,405.78 kWh/year | 60,600 kWh/year | –194.22 kWh/year | 60,502.89 kWh/year | –0.32% |

| 0.65 | 65,332.24 kWh/year | 65,038 kWh/year | 294.24 kWh/year | 65,185.12 kWh/year | 0.45% |

| Omani location | GPS coordinates (degree, minute, second – DMS) | GPS coordinates (decimal degree – DD) | Fixed optimum tilt |

| Buraimi | N 24°15'3'', E 55°47'35'' | 24.250833° N, 55.793056° E | 25° |

| Duqm | N 19°39'43'', E 57°42'13'' | 19.661944° N, 57.703611° E | 21° |

| Ibri | N 23°13'32'', E 56°30'56'' | 23.225556° N, 56.515556° E | 25° |

| Khasab | N 26°10'47'', E 56°14'51'' | 26.179722° N, 56.247500° E | 25° |

| Muscat | N 23°35'2'', E 58°24'28'' | 23.583889° N, 58.407778° E | 25° |

| Salalah | N 17°0'54'', E 54°5'32'' | 17.015000° N, 54.092222° E | 21° |

| Sohar | N 24°20'50'', E 56°42'33'' | 24.347222° N, 56.709167° E | 25° |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Average |

| 142.3 | 139.3 | 151.4 | 154.4 | 167.5 | 152.3 | 140.4 | 149.0 | 161.8 | 170.3 | 154.8 | 138.3 | 151.8 |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Average |

| 150.6 | 147.4 | 160.8 | 165.9 | 182.4 | 166.7 | 152.6 | 159.7 | 171.8 | 180.4 | 164.1 | 146.7 | 162.4 |

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Average |

| 161.0 | 157.4 | 172.2 | 178.9 | 198.3 | 181.7 | 165.5 | 171.6 | 183.5 | 192.4 | 175.4 | 157.1 | 174.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).