Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Validation method |

Ref | Proposed model |

Evaluation method |

PV device | Technology | Measurement conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor measurement |

[13] | Parallel single diode |

IV curve | Cell | Not reported | Temperature: 25-55°C. Irradiance: 1000 W/m2. |

| Module | Not reported | Albedo: 0.16. Irradiance: 900 ± 20 W/m2. |

||||

| Outdoor measurement |

[14] | Double diode | Annual bifacial gain and energy output |

Cell | N-type | Vertical east-west orientation. Two different albedo. |

| Outdoor measurement |

[15] | Single and double diode |

IV curve | Module | N-type | Frontal irradiance at 1000 W/m2 while rear irradiance varies between 0% and 30%. |

| Outdoor measurement |

[15] | Single diode traditional and parallel configuration |

Power and cumulative energy |

Module | Not reported | Daily performance estimation, considering summer and winter days. |

| Outdoor measurement |

[16] | Analytical and empirical |

DC power | Monofacial and bifacial PV array |

PERC | Variation in albedo levels Different levels of temperature and irradiance depending on weather conditions. |

| Simulation | [17] | Single diode | Energy yield | Module | Not reported | Daily and yearly performance estimation, considering sunny and cloudy days. |

| Simulation | [18] | Single diode | IV curves for monofacial and bifacial module |

Module | Not reported | STC condition: 25°C and 1000 W/m2. 20°C and 800 W/m2. |

2. Characterization of Bifacial PV Devices

2.1. Single-Sided Illumination

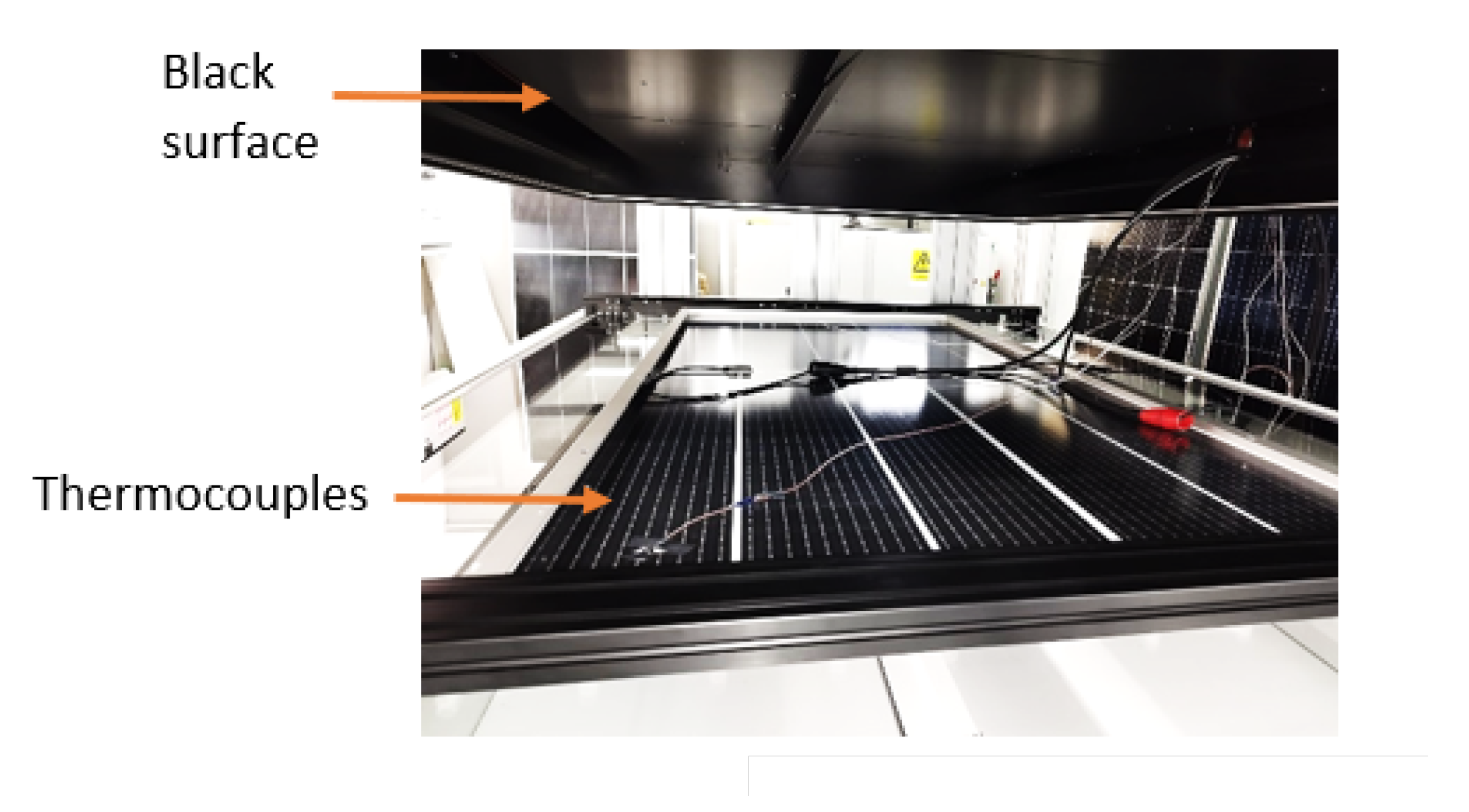

- Use a non-reflective material behind the non-illuminate side.

- Limit the exposure of the module illuminating with a source of the size of the module.

- Cover the non-illuminated side with a black surface.

2.2. Double-Sided Illumination

3. Bifacial Electrical Models

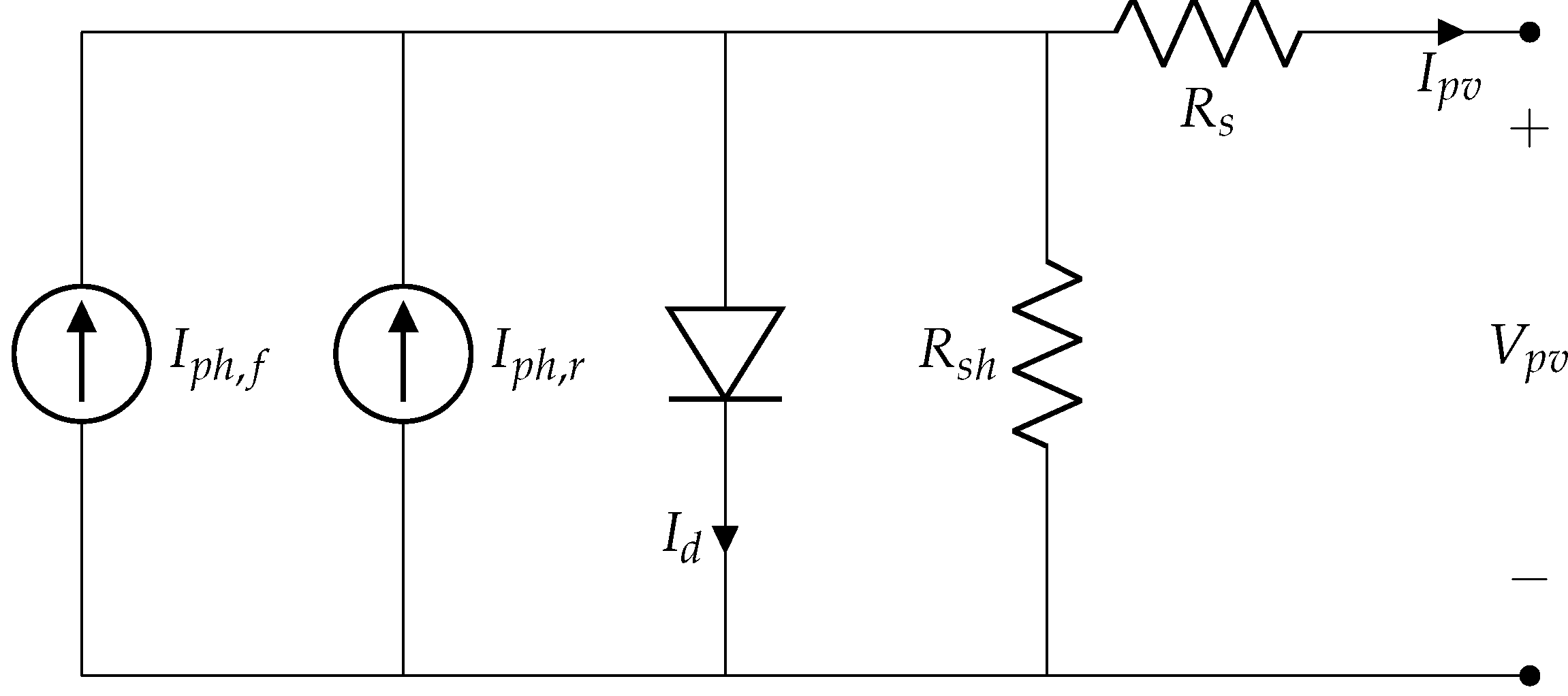

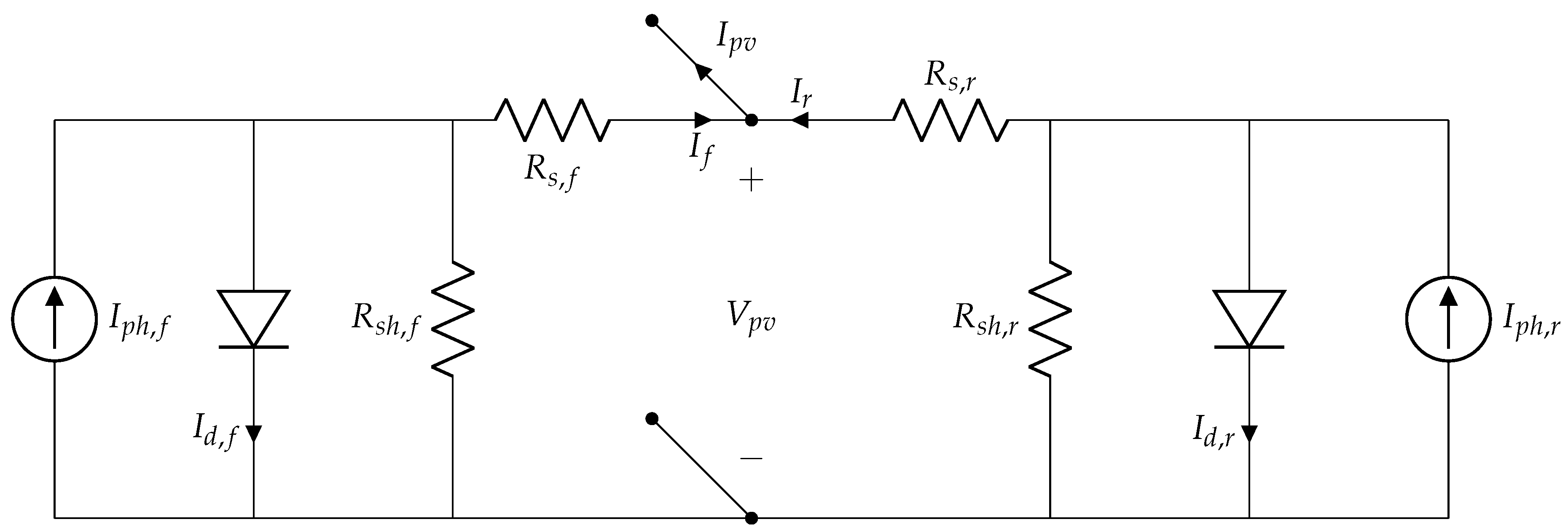

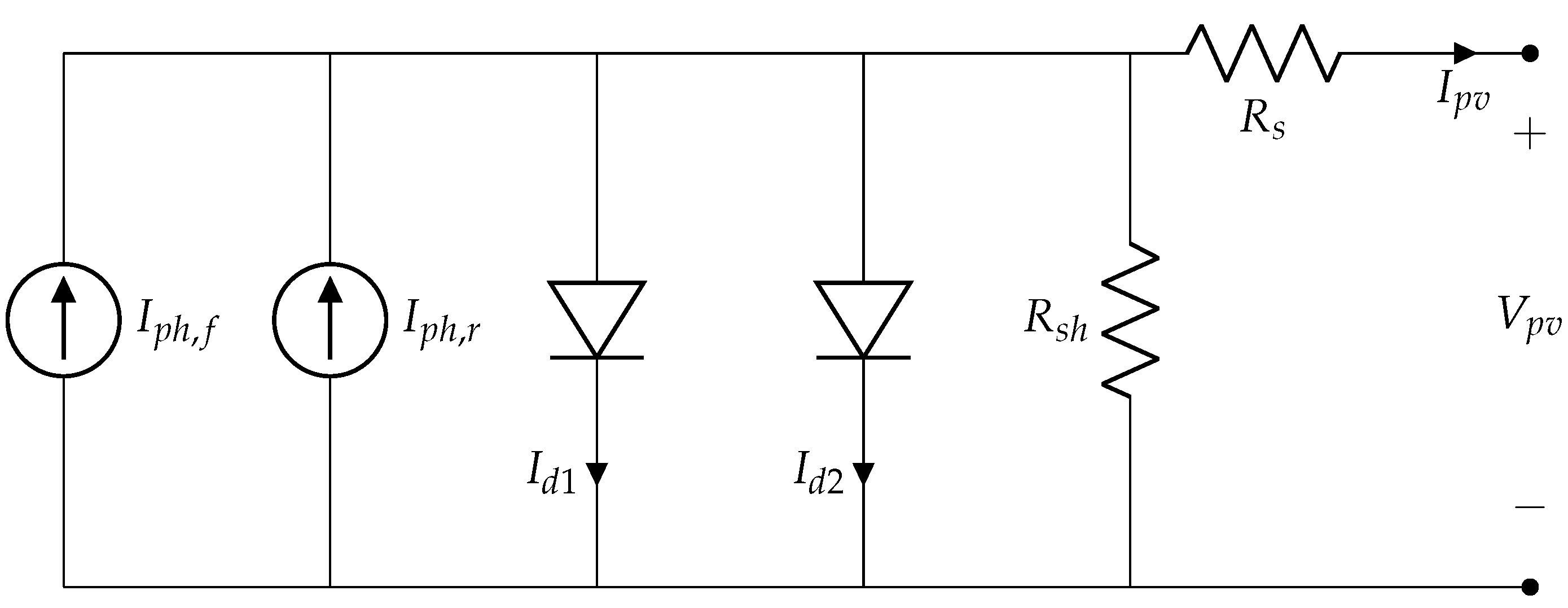

3.1. The Bifacial Representation

3.2. Models Evaluation

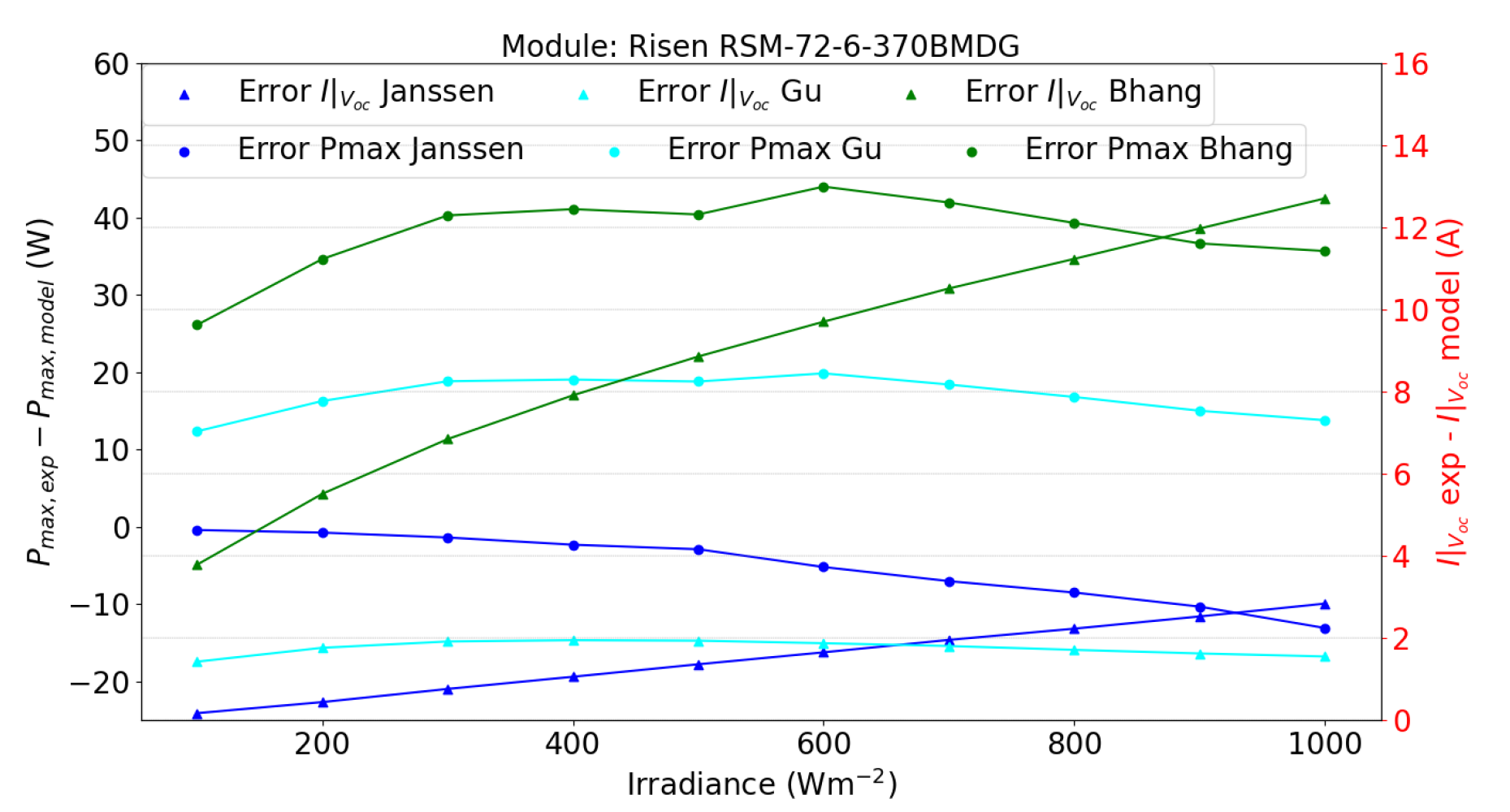

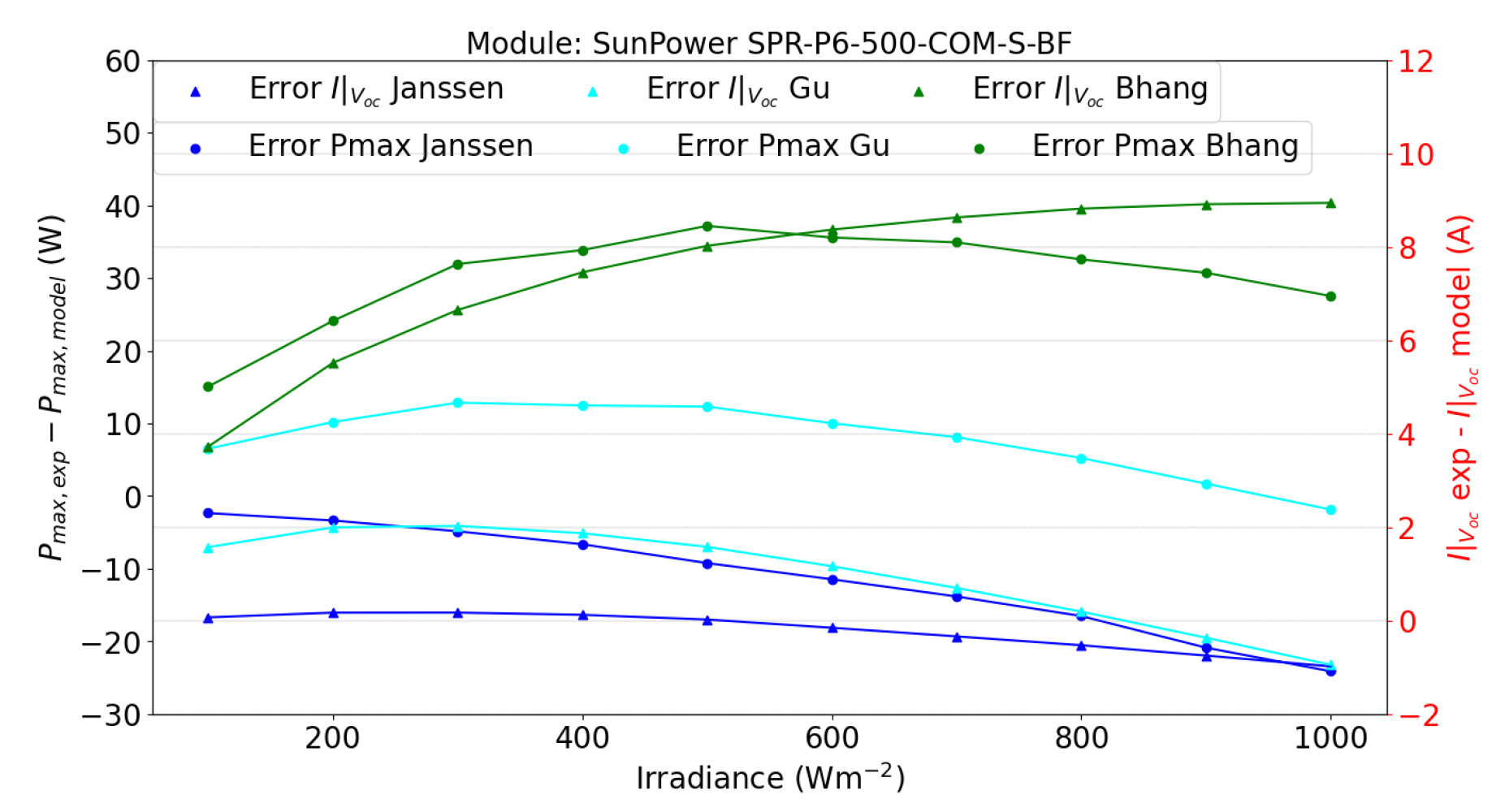

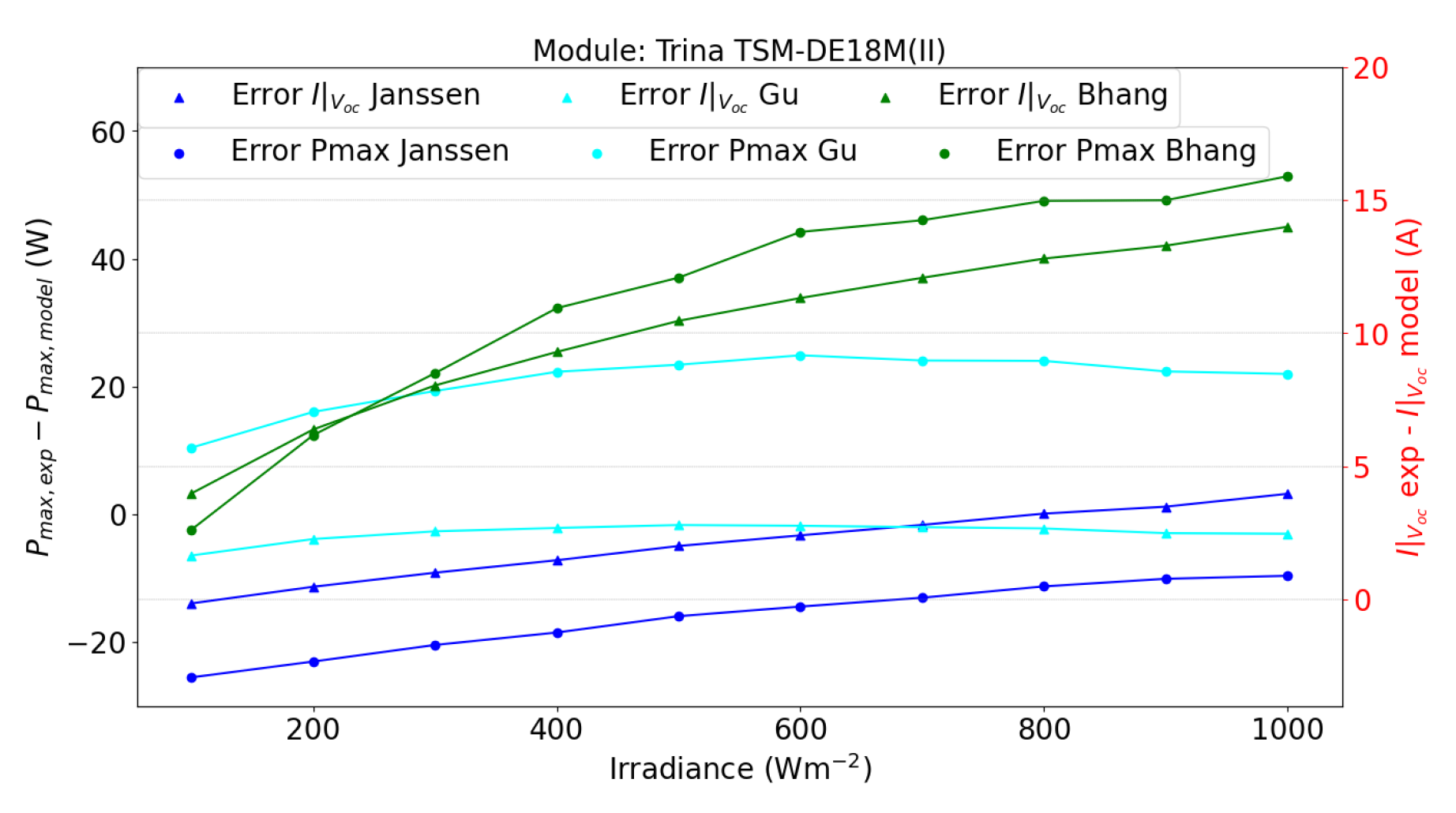

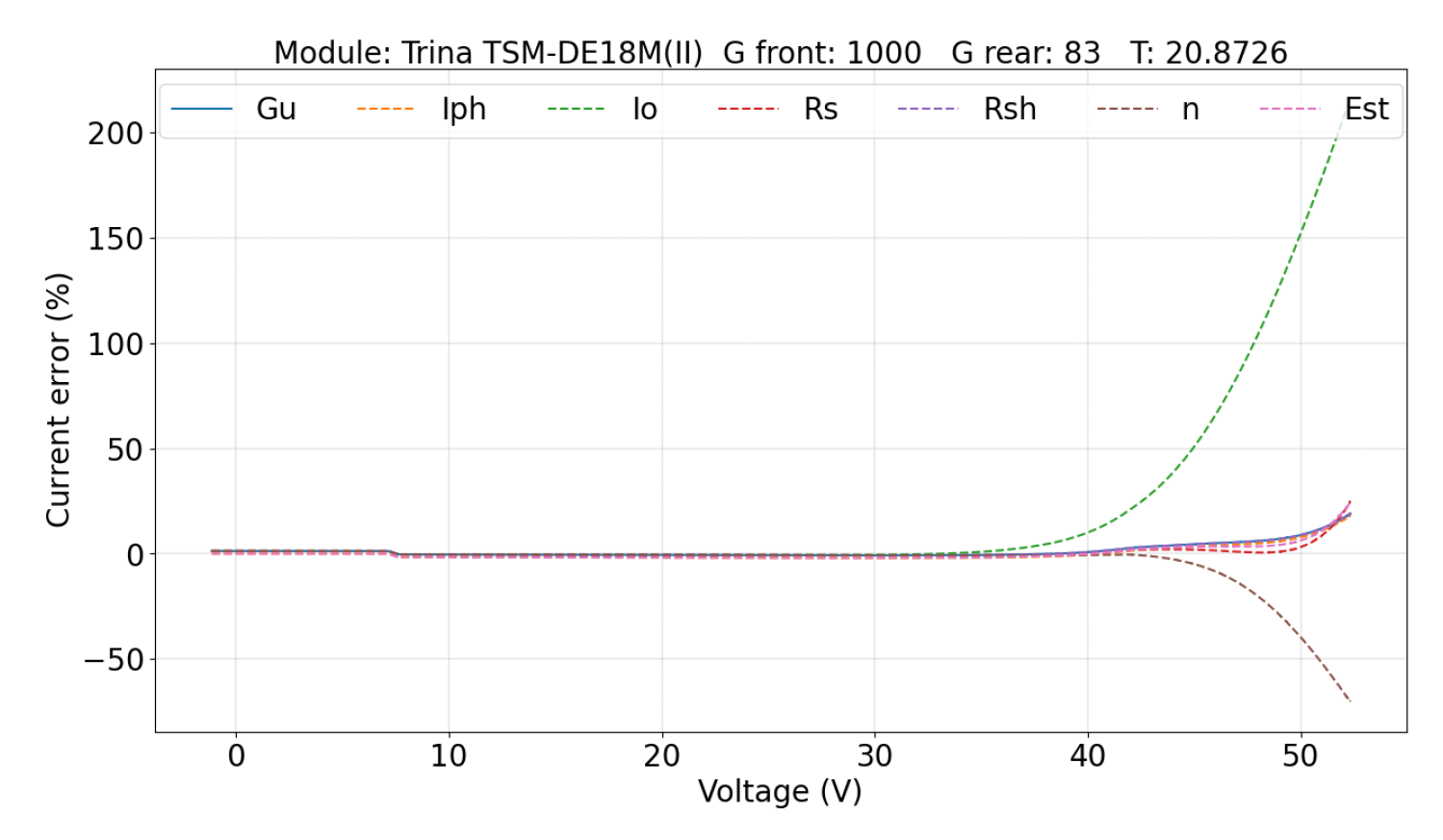

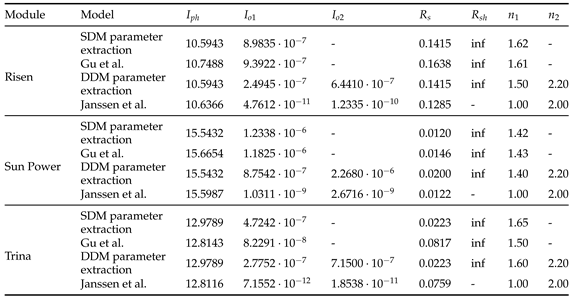

- Guet al. [17] The single-diode model requires 5 parameters. The estimation method the authors proposed for these parameters is implemented as described by Equations (13)–(17).Once the 5 parameters are calculated, they are adjusted to their actual irradiance and temperature conditions. The photocurrent () is defined in Equation (10), while the remaining parameters are computed using equations Equations (18)–(21):

- Janssenet al. [14] Utilizes a double-diode model, where initially 7 parameters have to be estimated. However, based on the author’s considerations, 3 parameters are assumed: , and . Then, to obtain the first diode saturation current, the formulation proposed by [21] is employed, given by Equation (22).On the other hand, the second diode saturation current is calculated by Equation (23).Finally, the series resistance is calculated by Equation (19) and are transformed to its original ambient conditions, the first is done by applying Equation (6), and the second is accomplished by the application of Equation (24).

- Bhanget al. [13] Proposed a single-diode model with a parallel configuration, resulting in the estimation of 10 parameters, 5 for the frontal face and the other 5 for the rear. A W-Lambert parameter estimation is employed to obtain it, utilizing the measured values at STC for both faces. Finally, the parameters are corrected utilizing Equation (10),Equation (18),Equation (19),Equation (20).

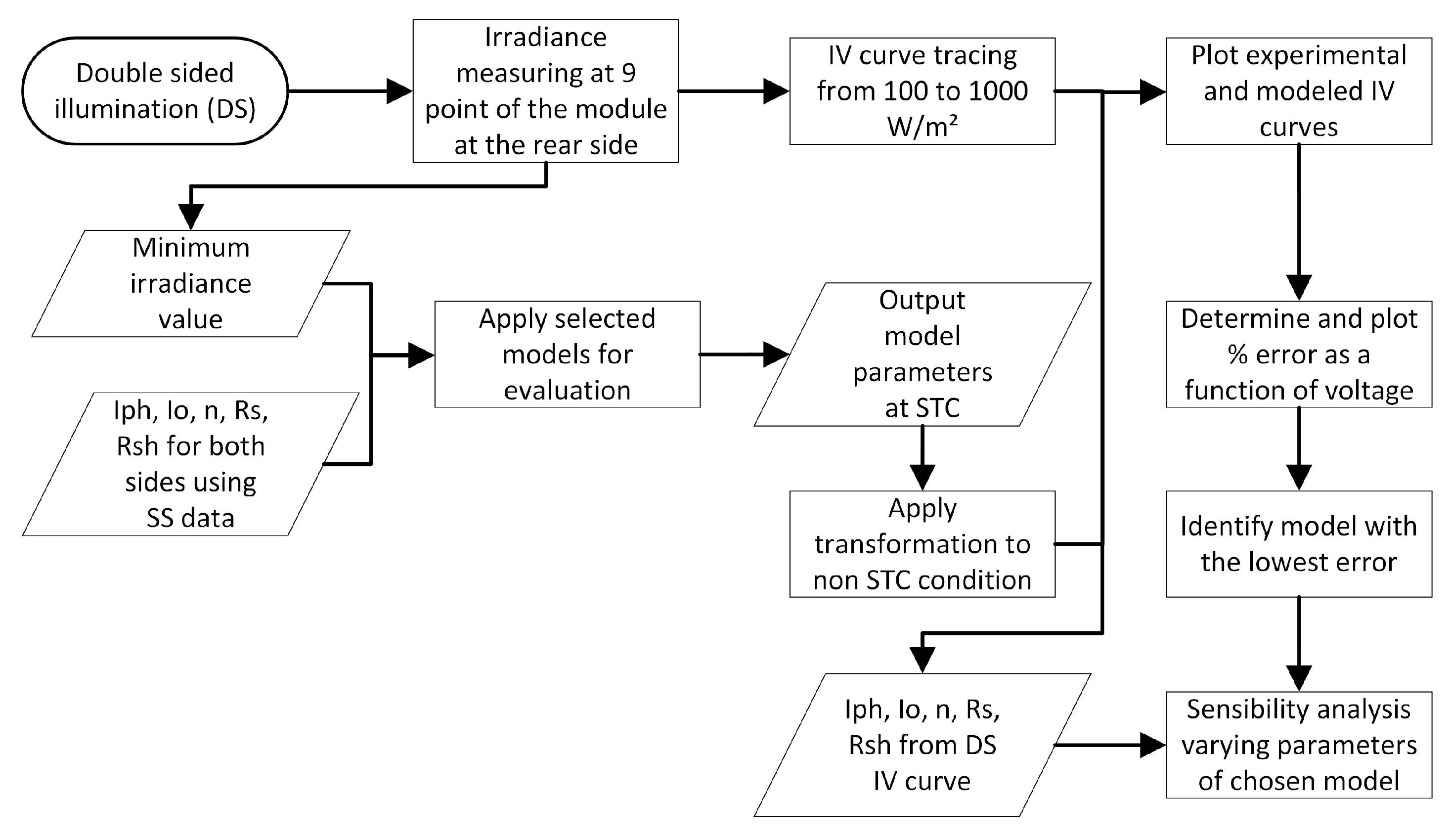

4. Methodology

4.1. Setup

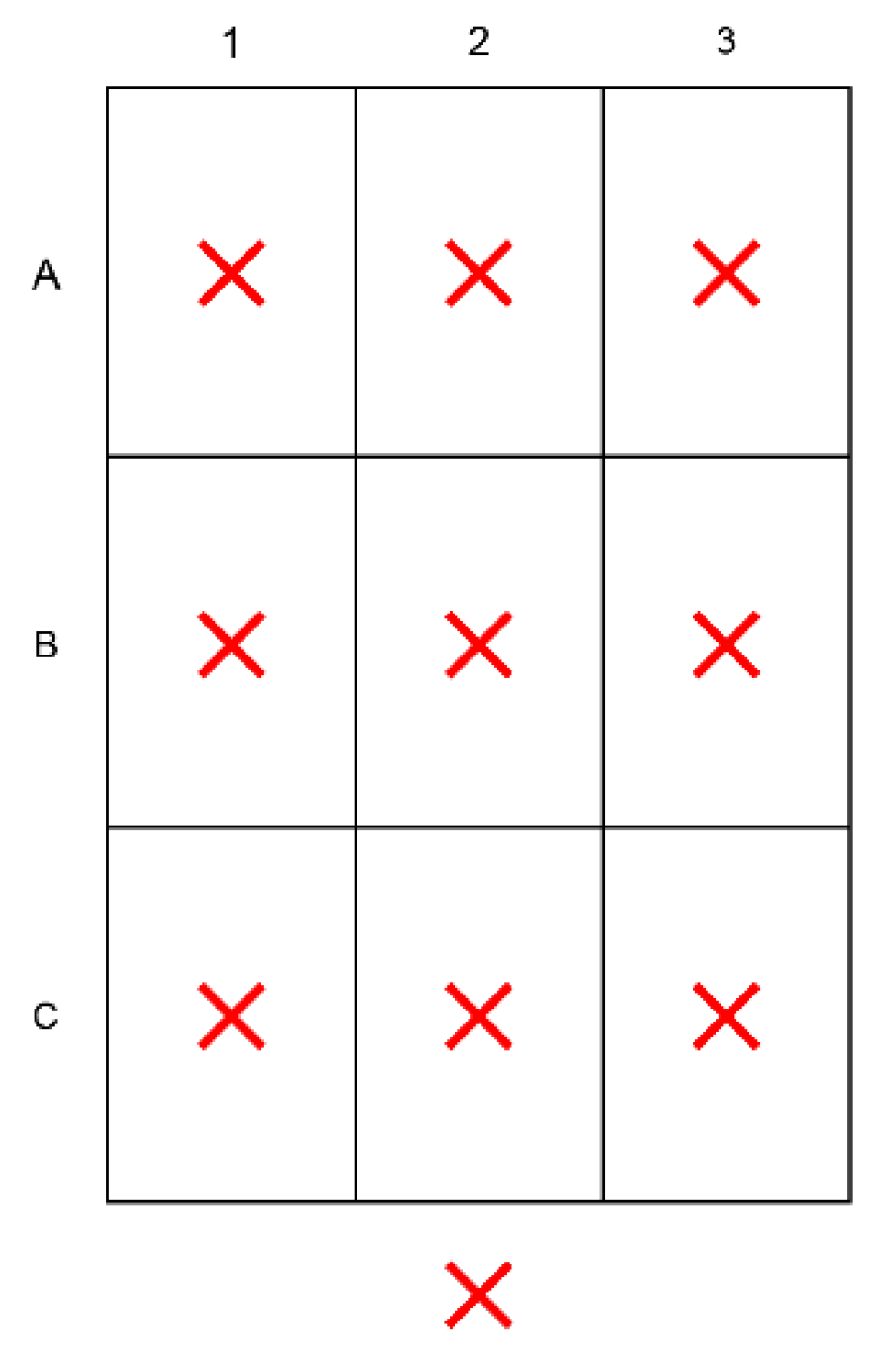

4.1.1. Bifacial Modules

4.1.2. Solar Simulator

4.2. Measurement

4.2.1. Single-Sided Illumination (SS)

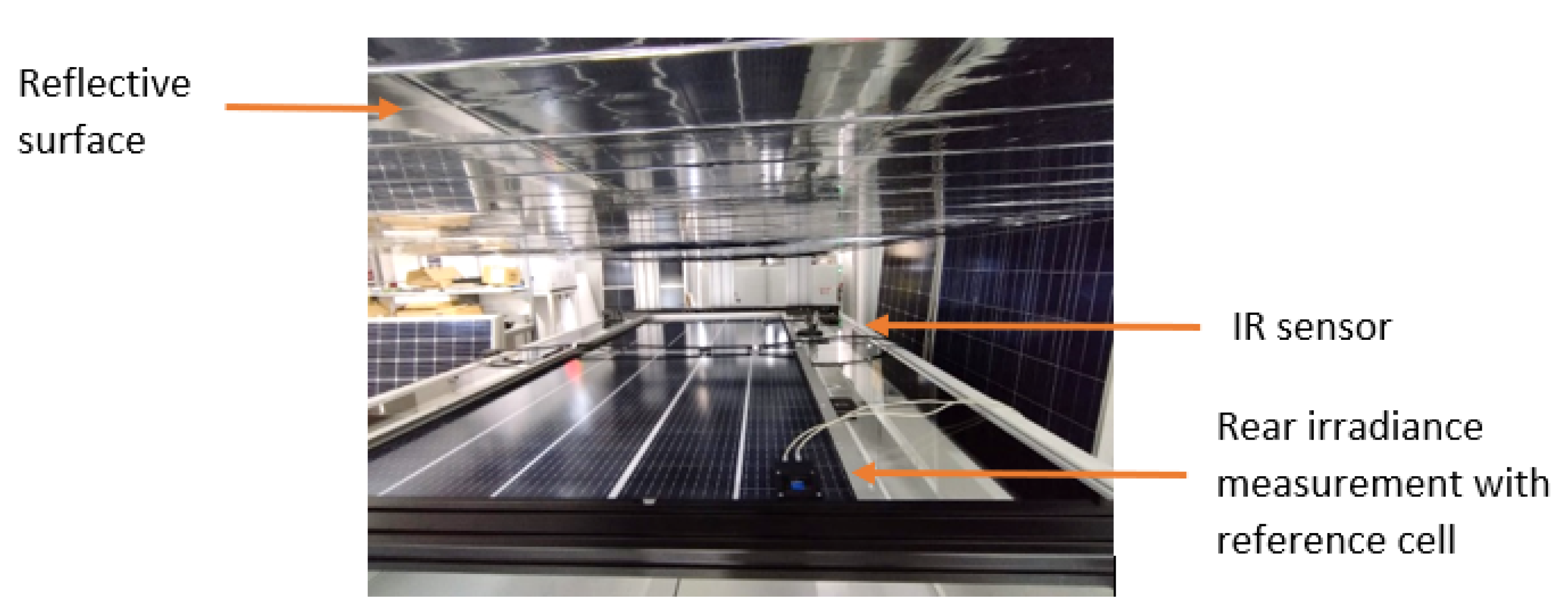

4.2.2. Double-Sided Illumination (DS)

4.3. Data Processing and Model Approach

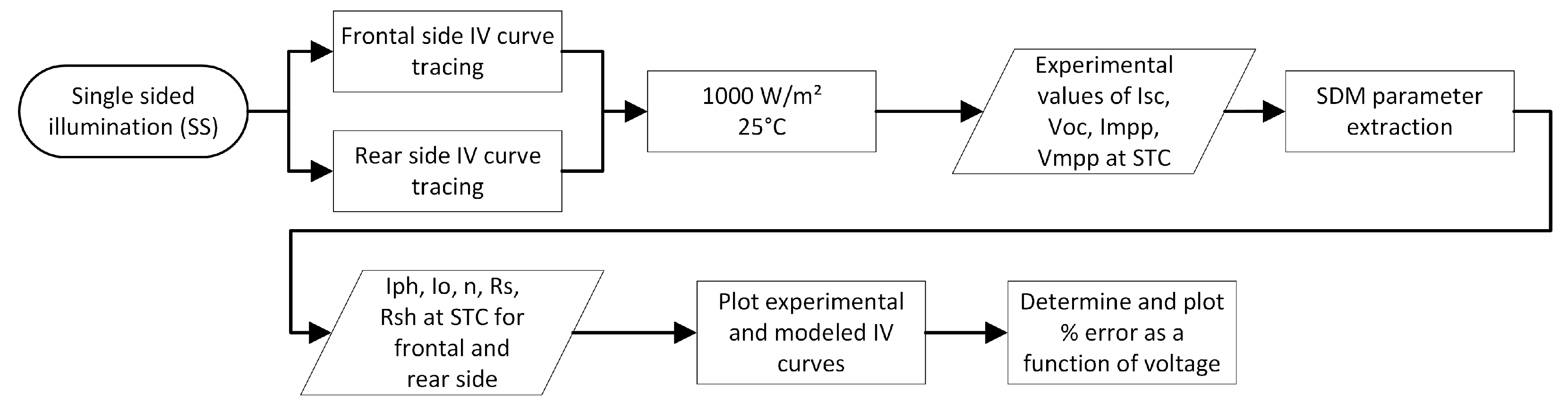

4.3.1. Single-Sided Illumination Measurement (SS)

4.3.2. Double-Sided Illumination Measurement (DS)

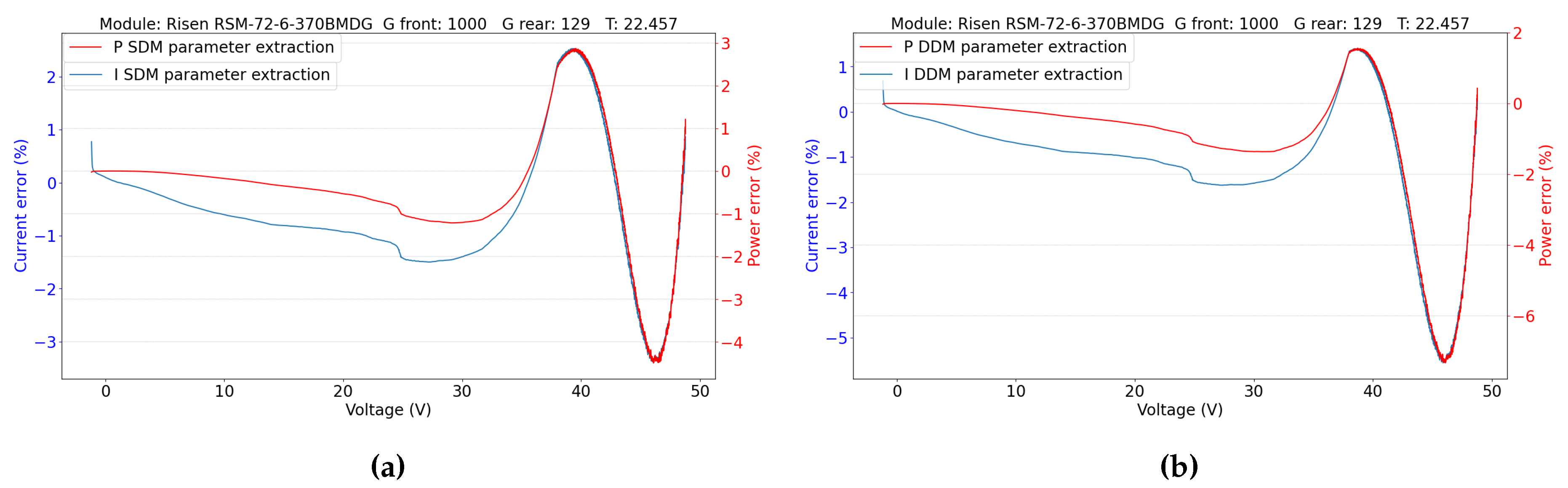

5. Results and Discussion

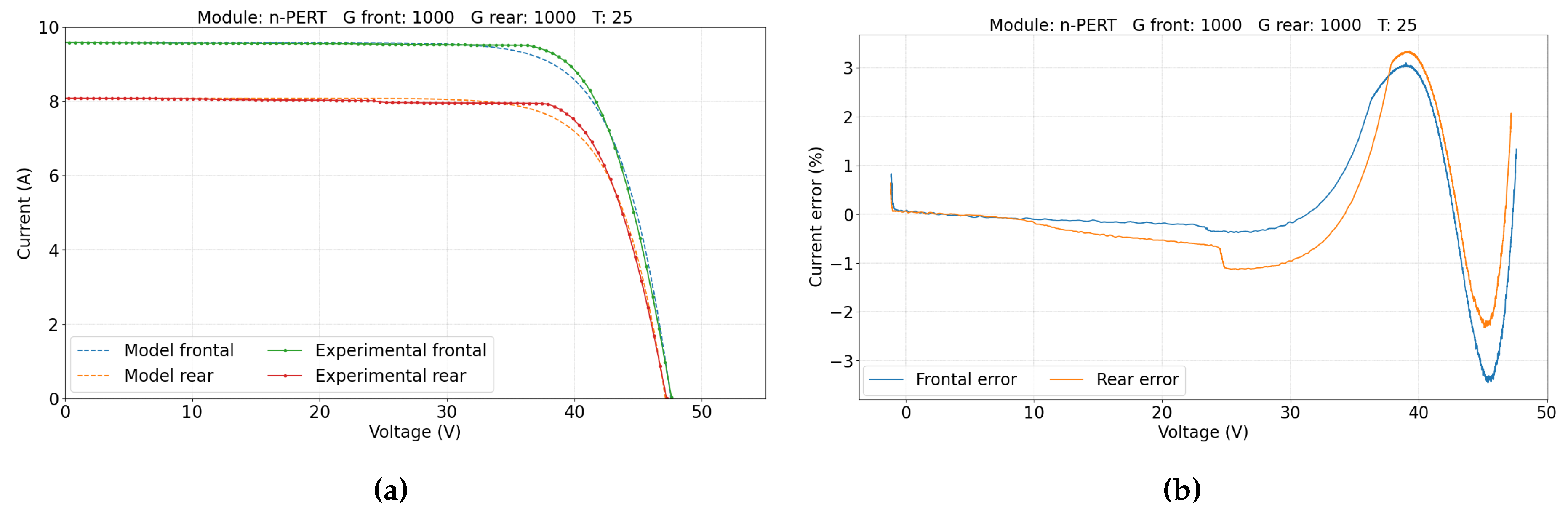

5.1. Single-Sided Illumination Measurement

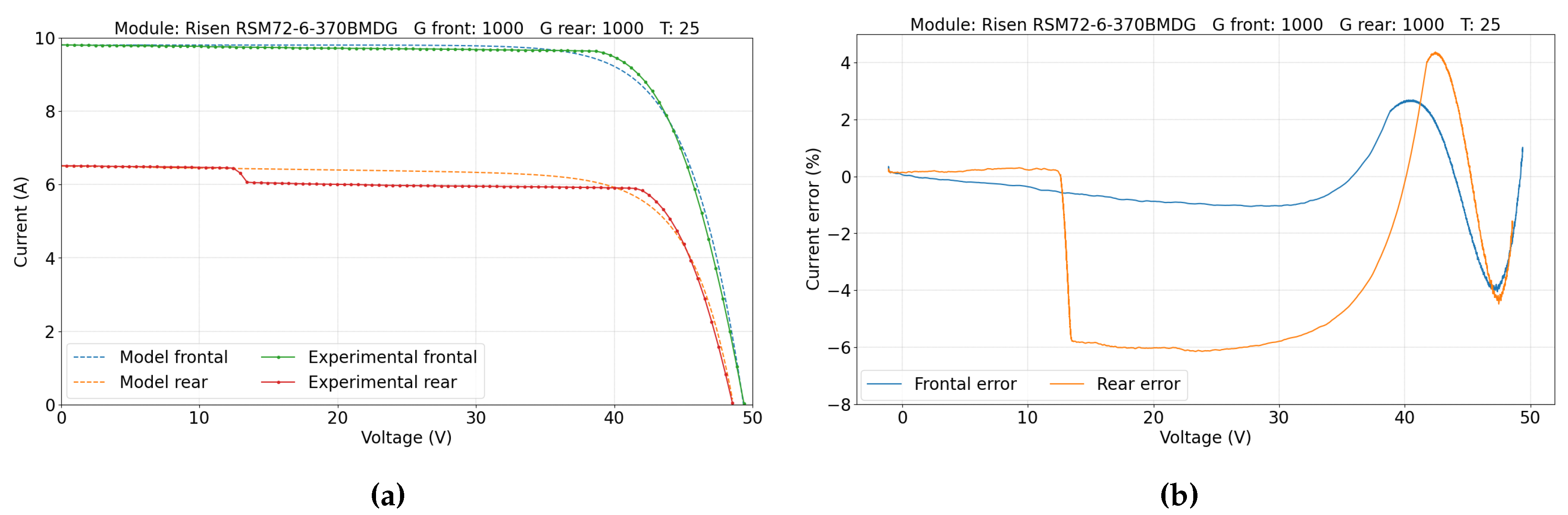

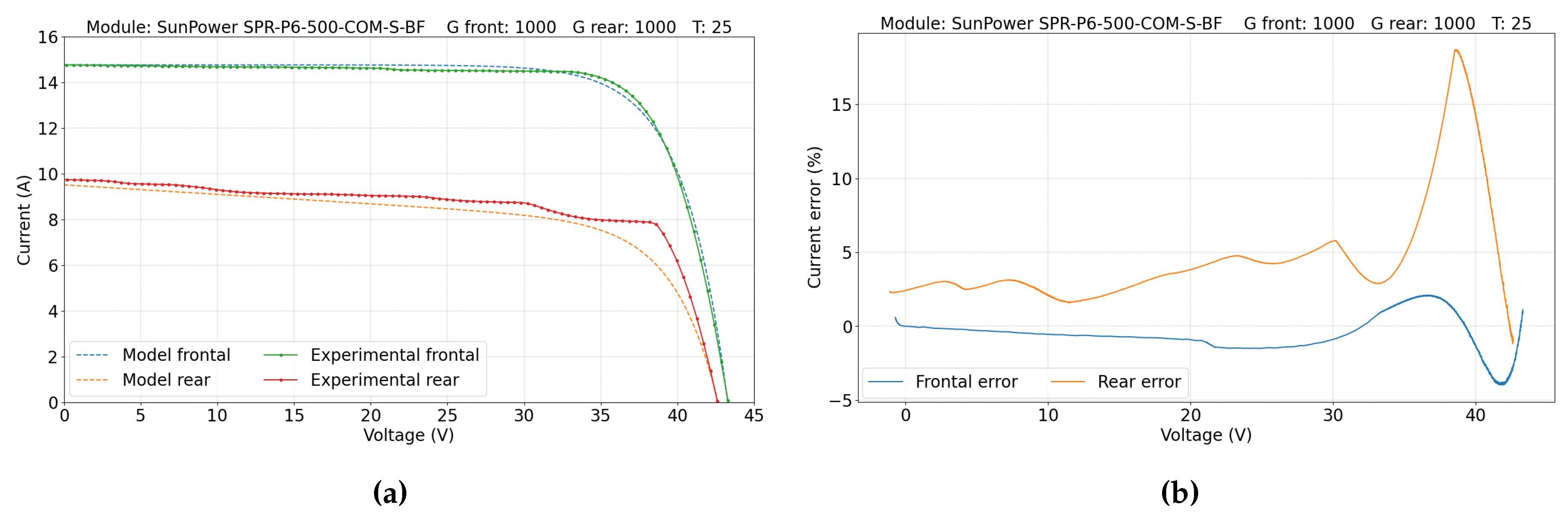

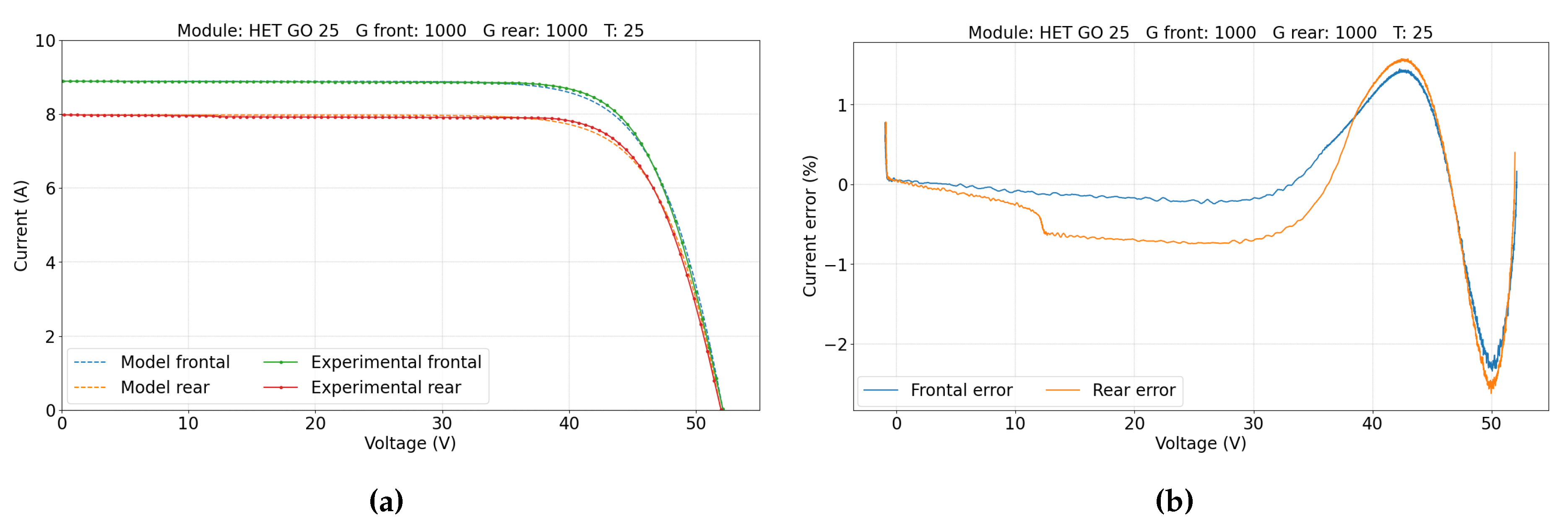

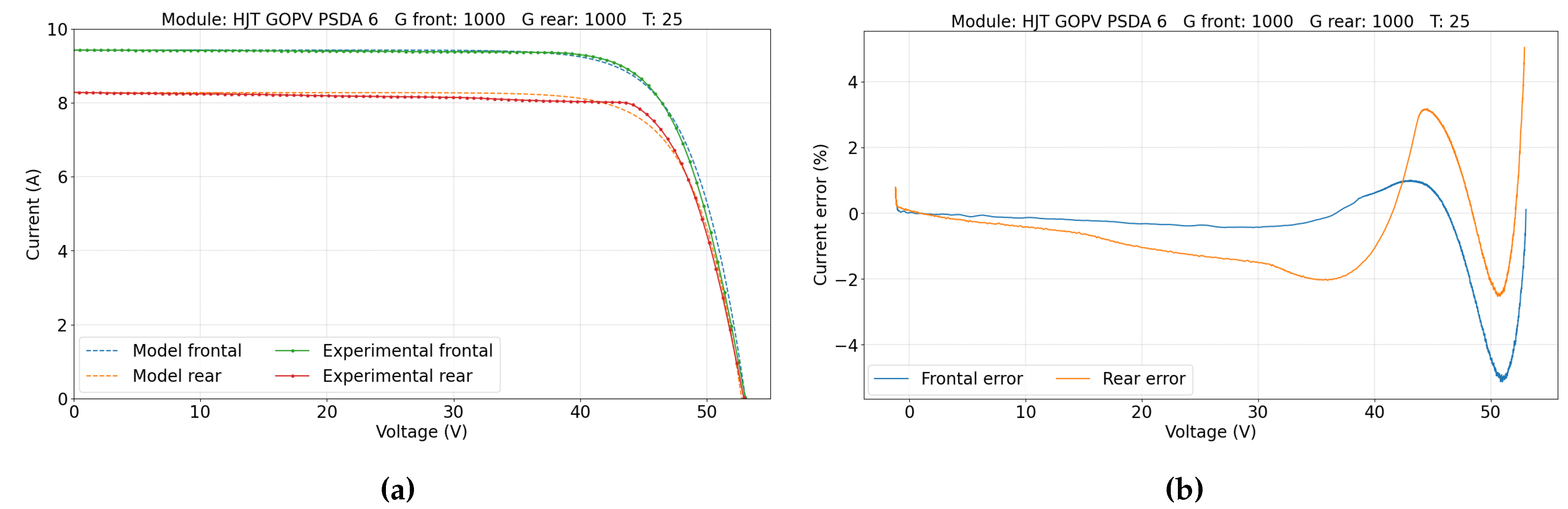

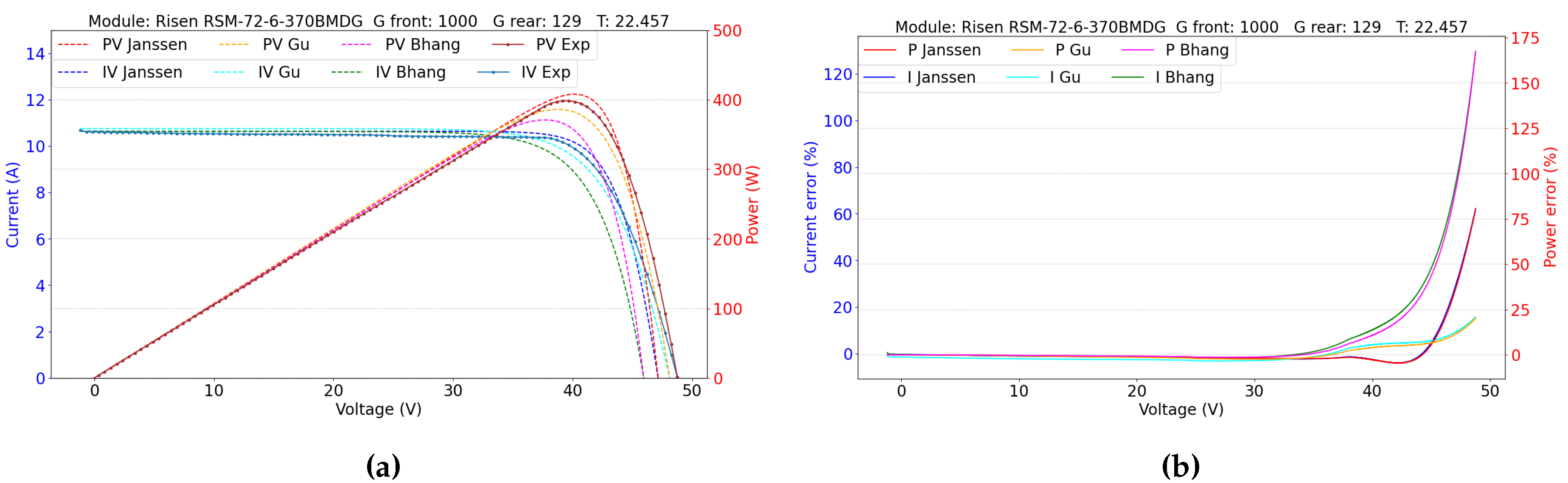

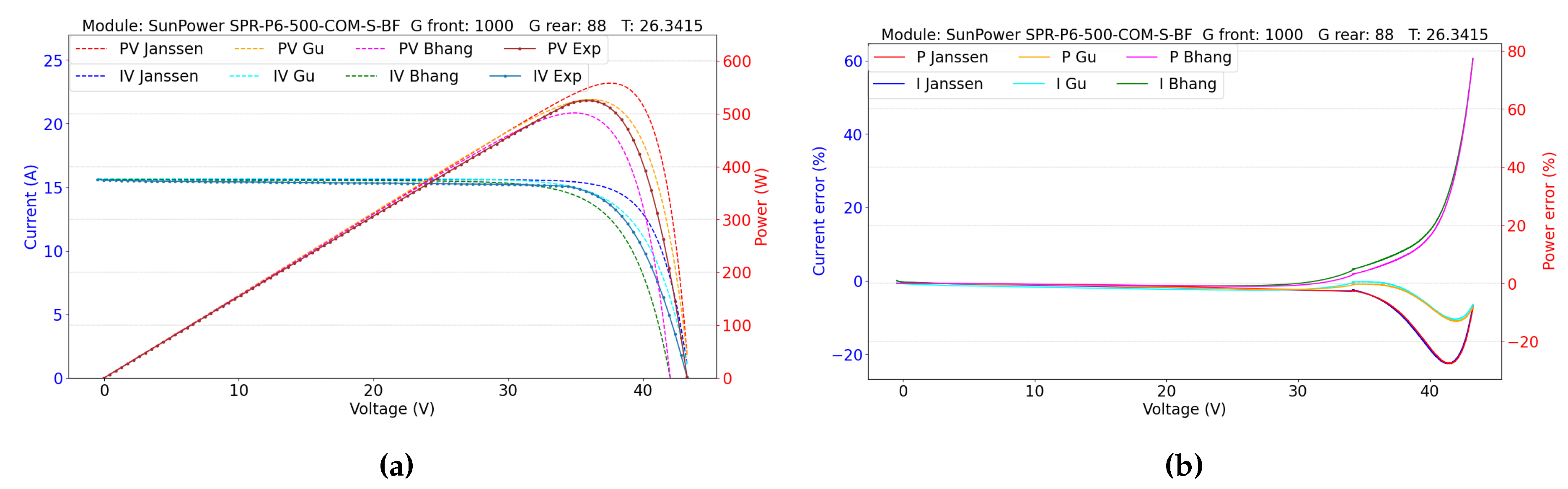

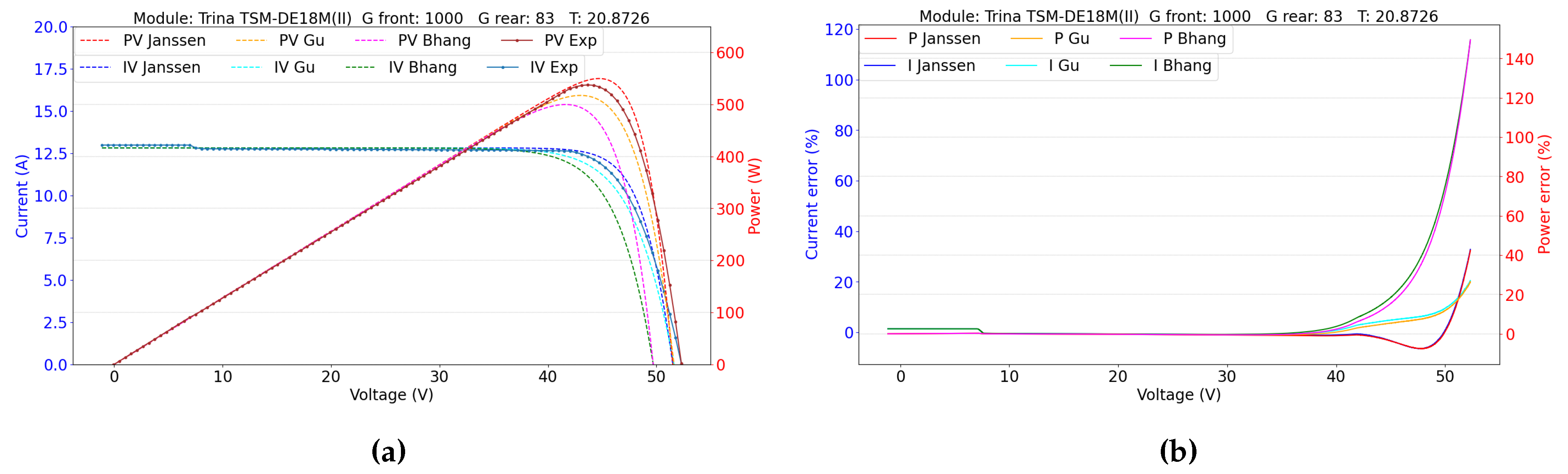

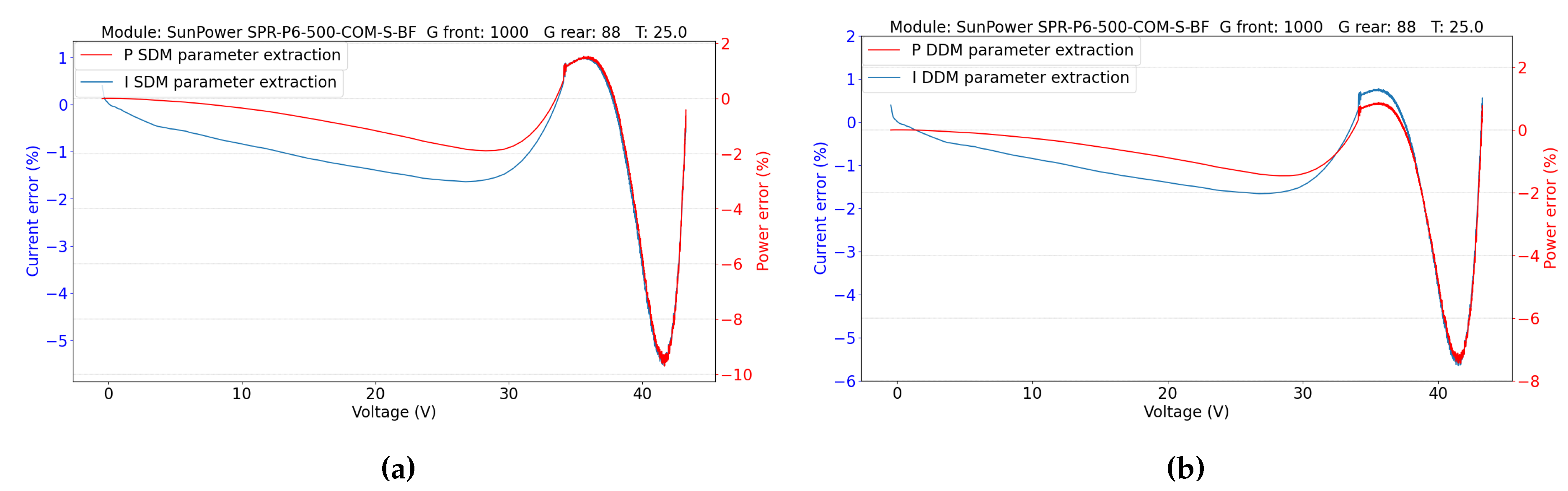

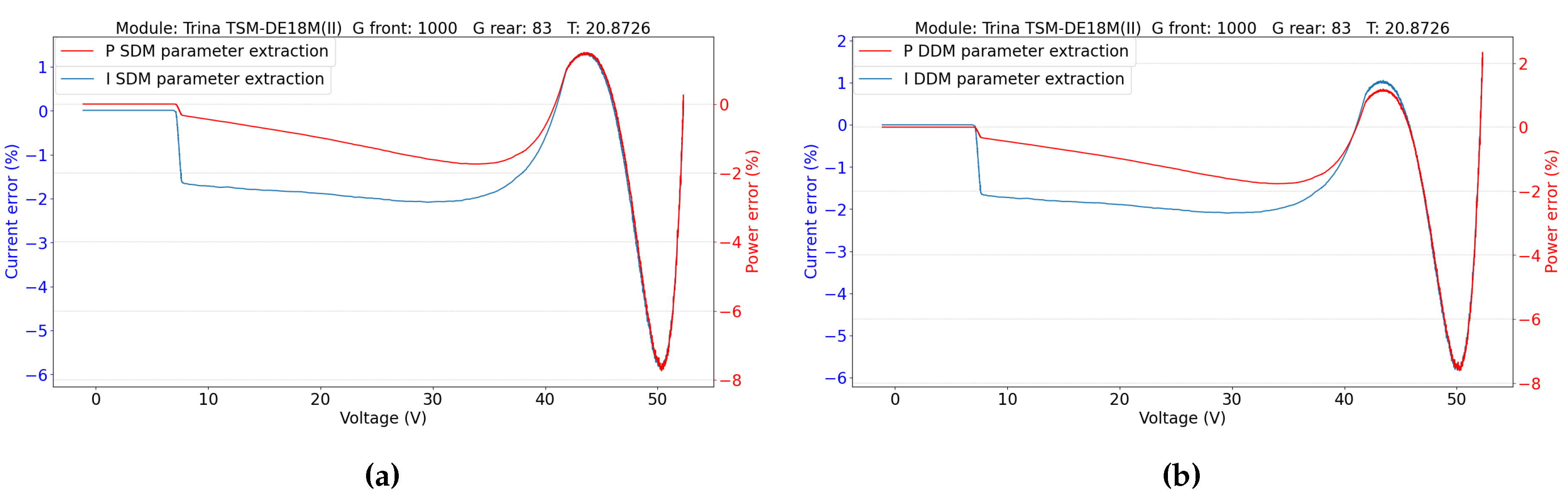

5.2. Double-Sided Illumination Measurement

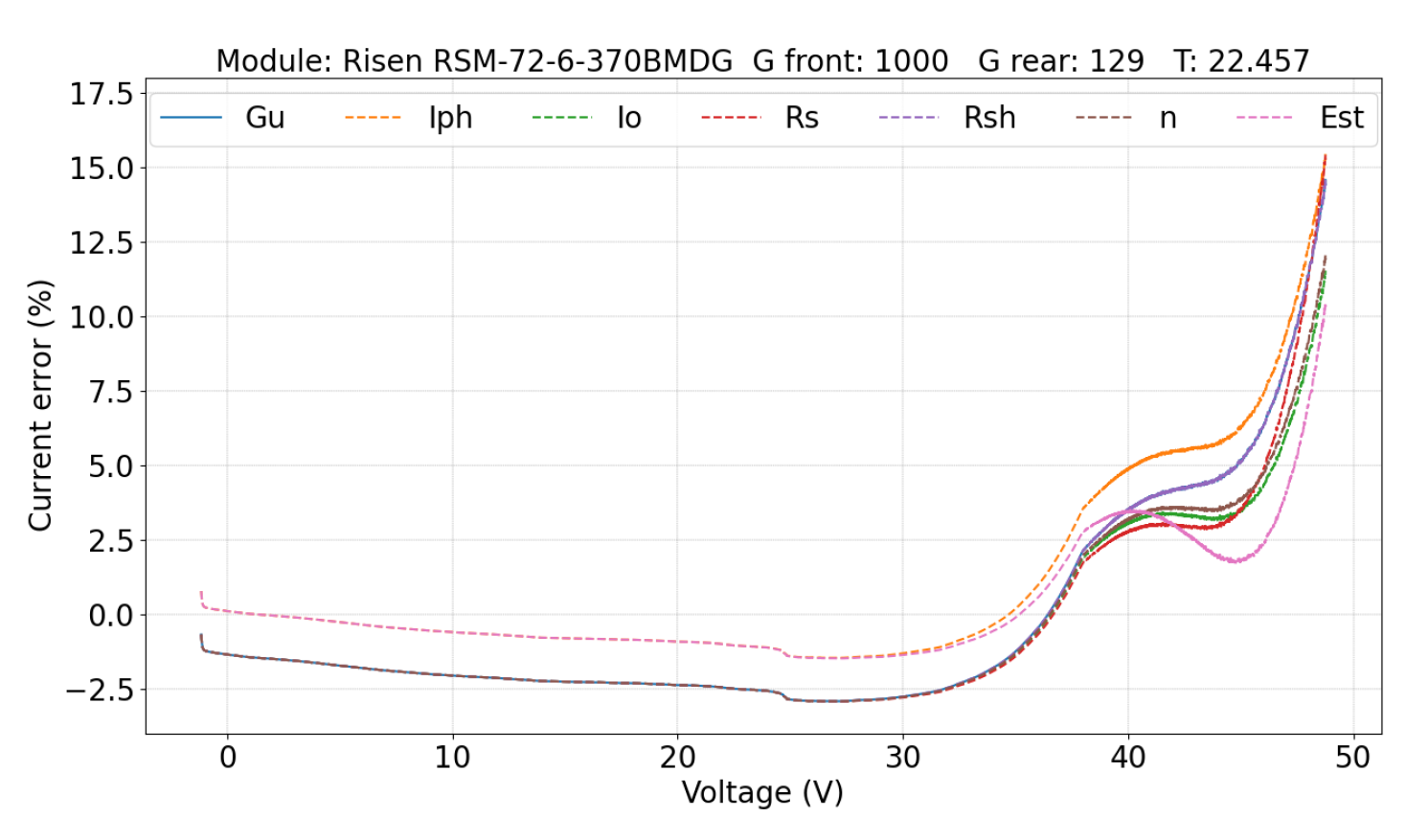

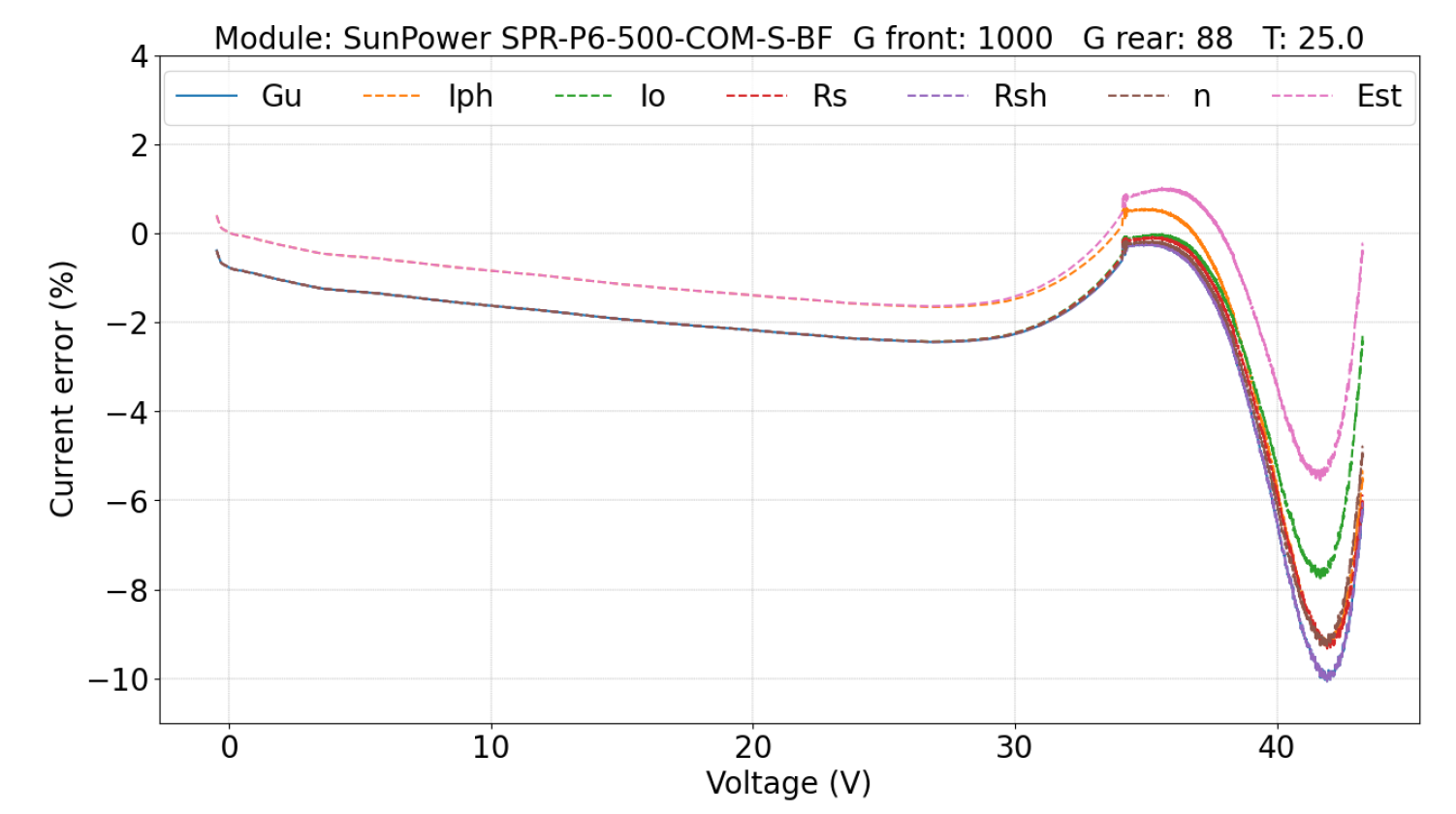

5.2.1. Parameters Evaluation

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Mouhib, E.; Micheli, L.; Almonacid, F.M.; Fernández, E.F. Overview of the Fundamentals and Applications of Bifacial Photovoltaic Technology: Agrivoltaics and Aquavoltaics. Energies 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, A.; Luque, A.; Eguren, J.; del Alamo, J. 50 Per cent more output power from an albedo-collecting flat panel using bifacial solar cells. Solar Energy 1982, 29, 419–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.P.; Drori, A.; Karsenty, A.; Bordin, N.; Kreinin, L.B. Experimental Analysis of the Increases in Energy Generation of Bifacial Over Mono-Facial PV Modules. 2011.

- Tina, G.M.; Bontempo Scavo, F.; Merlo, L.; Bizzarri, F. Comparative analysis of monofacial and bifacial photovoltaic modules for floating power plants. Applied Energy 2021, 281, 116084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gallegos, C.D.; Bieri, M.; Gandhi, O.; Singh, J.P.; Reindl, T.; Panda, S. Monofacial vs bifacial Si-based PV modules: Which one is more cost-effective? Solar Energy 2018, 176, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, F.; Baloch, A.A.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Impact of climate change on solar monofacial and bifacial Photovoltaics (PV) potential in Qatar. Energy Reports 2022, 8, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, N.; Libois, Q.; Badosa, J.; Migan-Dubois, A.; Bourdin, V. Errors in PV power modelling due to the lack of spectral and angular details of solar irradiance inputs. Solar Energy 2020, 197, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonanzas, J.; Osorio, N.; Escobar, R.; Urraca, R.; de Pison, F.M.; Antonanzas-Torres, F. Review of photovoltaic power forecasting. Solar Energy 2016, 136, 78–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, T.S.; Pravettoni, M.; Deline, C.; Stein, J.S.; Kopecek, R.; Singh, J.P.; Luo, W.; Wang, Y.; Aberle, A.G.; Khoo, Y.S. A review of crystalline silicon bifacial photovoltaic performance characterisation and simulation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 116–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Photovoltaic devices - Part 1-2: Measurement of current-voltage characteristics of bifacial photovoltaic (PV) devices. Technical specification, International Electrotechnical Commision, 2019.

- Liang, T.S.; Poh, D.; Pravettoni, M. Challenges in the pre-normative characterization of bifacial photovoltaic modules. Energy Procedia 2018, 150, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razongles, G.; Sicot, L.; Joanny, M.; Gerritsen, E.; Lefillastre, P.; Schroder, S.; Lay, P. Bifacial Photovoltaic Modules: Measurement Challenges. Energy Procedia 2016, 92, 188–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhang, B.G.; Lee, W.; Kim, G.G.; Choi, J.H.; Park, S.Y.; Ahn, H.K. Power Performance of Bifacial c-Si PV Modules With Different Shading Ratios. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2019, 9, 1413–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, G.; Van Aken, B.; Carr, A.; Mewe, A. Outdoor Performance of Bifacial Modules by Measurements and Modelling. Energy Procedia 2015, 77, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.M.; Aly, M.; Mostafa, M.; Rezk, H.; Alnuman, H.; Alhosaini, W. An Accurate Model for Bifacial Photovoltaic Panels. Sustainability 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchakour, S.; Valencia-Caballero, D.; Luna, A.; Roman, E.; Boudjelthia, E.A.K.; Rodríguez, P. Modelling and Simulation of Bifacial PV Production Using Monofacial Electrical Models. Energies 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Ma, T.; Li, M.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Y. A coupled optical-electrical-thermal model of the bifacial photovoltaic module. Applied Energy 2020, 258, 114075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergura, S. Simulink model of a bifacial PV module based on the manufacturer datasheet. Renewable Energy and Power Quality Journal 2020, 18, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagunas, A.; Cuadra, J.; Petrina, I.; Mayo, M.E. Design of a Special Set-Up for the I-V Characterization of Bifacial Photovoltaic Solar Cells. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Z. Comparison of Double-Side and Equivalent Single-Side Illumination Methods for Measuring the I–V Characteristics of Bifacial Photovoltaic Devices. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2018, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, B.C.; Gurjar, S. A Novel Simplified Two-Diode Model of Photovoltaic (PV) Module. IEEE Journal of Photovoltaics 2014, 4, 1156–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raina, G.; Sinha, S. A comprehensive assessment of electrical performance and mismatch losses in bifacial PV module under different front and rear side shading scenarios. Energy Conversion and Management 2022, 261, 115668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Module | Pmax (W) | Technology | Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risen RSM72-6-370BMDG | 370 | PERC+ | SS, DS |

| GOPV PSDA 6 | 393 | HJT | SS |

| HET GO 25 | 355 | HJT | SS |

| n-PERT | 348 | n-PERT | SS |

| Trina TSM-490DEG18MC.20(II) | 490 | PERC+ | DS |

| SunPower SPR-P6-500-COM-S-BF | 500 | PERC+ | SS, DS |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).