Submitted:

25 July 2024

Posted:

26 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

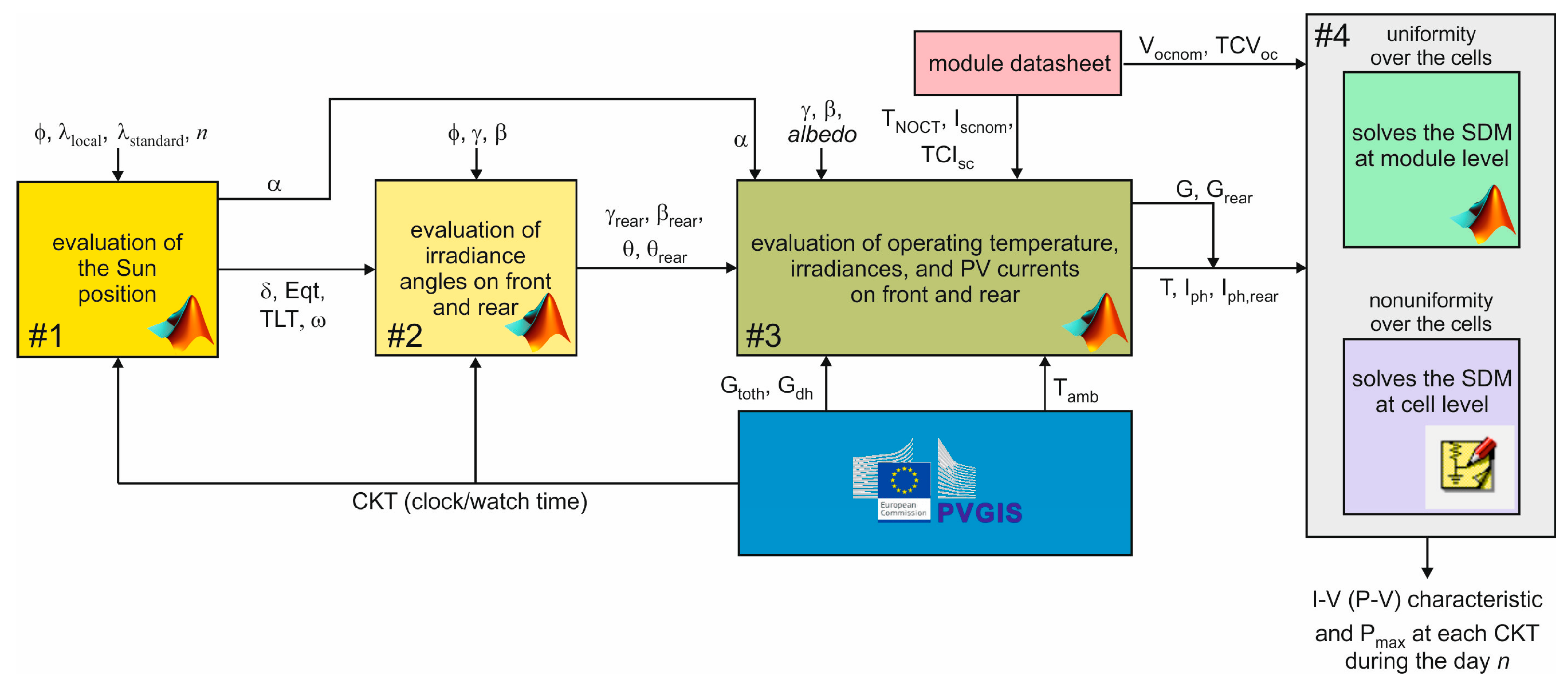

2. The Tool

2.1. Block #1

- The latitude ϕ and the local longitude λ, denoted as λlocal, of the geographical site where the PV module is installed (ϕ is equal to 0° at the equator, and ranges from 0° to 90° to the north, from 0° to -90° to the south; λlocal is equal to 0° at the Prime, or Greenwich, meridian, and ranges from 0° to 180° to east, from 0° to -180° to west).

- The longitude λstandard of the standard meridian on which the clock time (CKT, also referred to as watch time or standard local time) is based.

- The day of the year n.

- The CKT values during the day, i.e., the daytime discretization.

- The solar declination δ, i.e., the angle between the Sun rays (the beam radiation) and the equatorial plane, which is positively defined in the northern hemisphere. Angle δ can be reasonably assumed constant during a day (it varies by at most 0.5°), and dependent on the day of the year n through the empirical Cooper’s relation

- The so-called True Local Time (TLT), which can be obtained from the CKT by applying two corrections. The first correction is dictated by the difference between the local longitude λlocal and the longitude of the standard meridian λstandard; more specifically, the displacement of 1° between these longitudes corresponds to 4 minutes. The second correction is made to account for the non-constancy of the rotation rate of the Earth around the Sun during the year. This effect can be described by introducing a characteristic time referred to as Equation of Time (Eqt) expressed in minutes, which depends on n through the following relation [20,21,22]:

- The hour angle ω, i.e., the angular displacement of the Sun with respect to the local meridian compared to the case in which TLT=12 due to the rotation from west to east of the Earth around its axis (also denoted as angle subtended by the Sun [23]). Angle ω is negative in the morning, positive in the afternoon, and given by [20,22,24,25,26,27]

2.2. Block #2

- The latitude ϕ of the site.

- The CKT values.

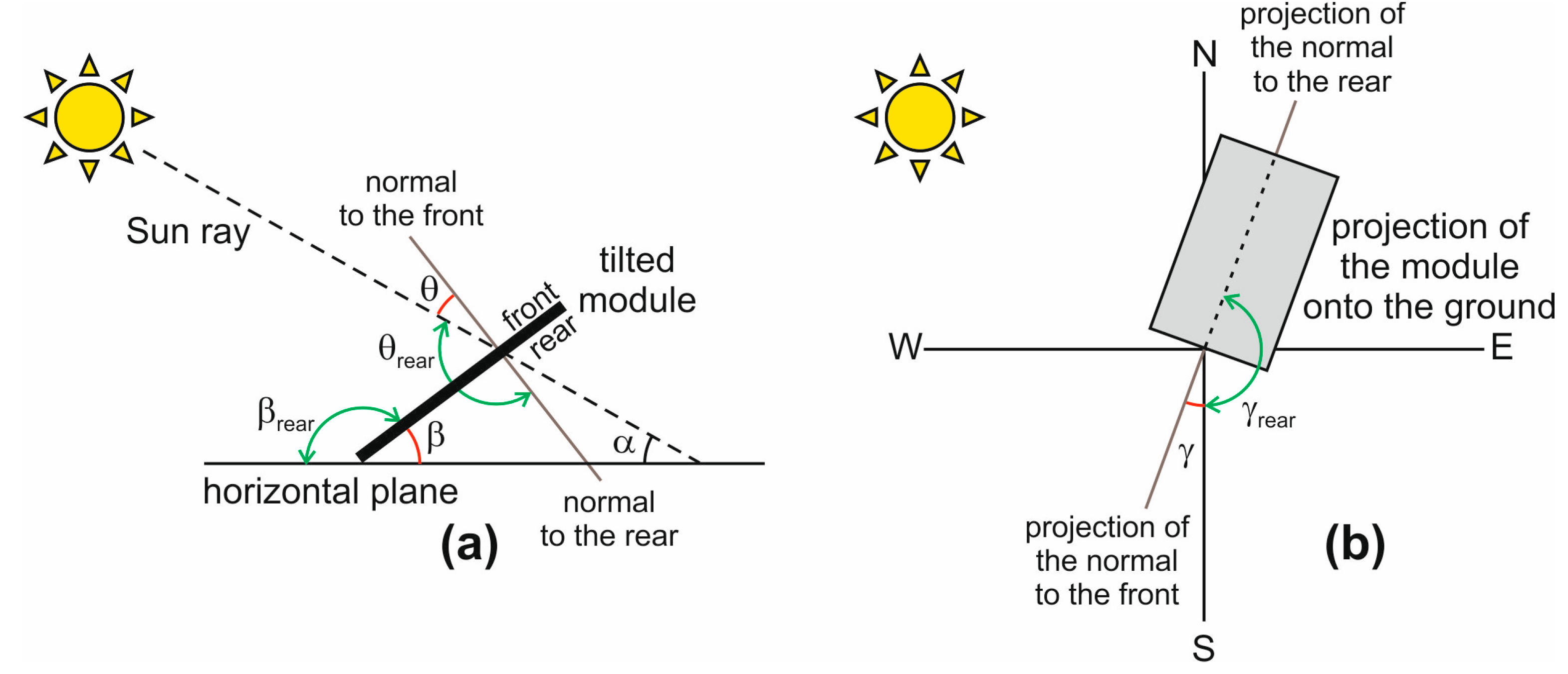

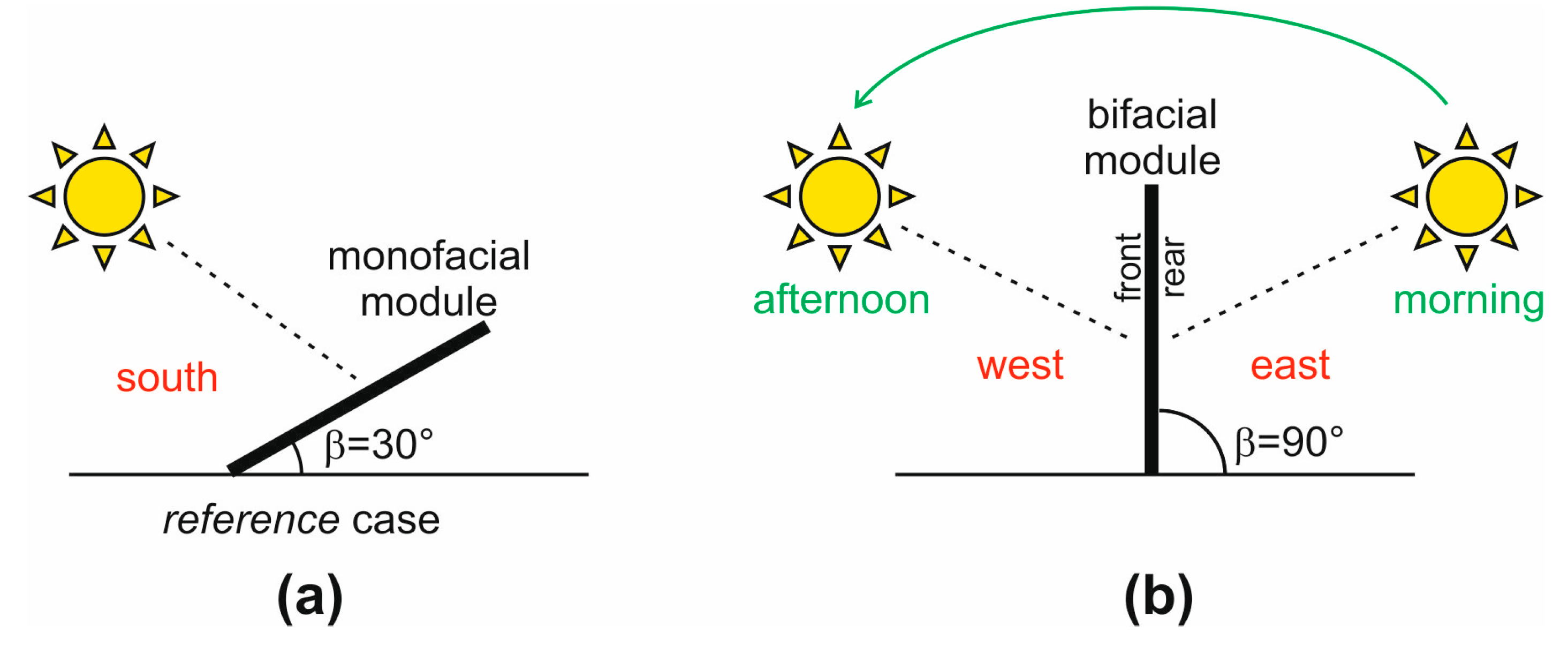

- The azimuth angle of the module front γ, which defines the module orientation, as it is the angular displacement from south of the projection of the normal to the module front onto the horizontal plane. An azimuth γ=0° means that the front is south-oriented; γ is positive clockwise (to west), reaching 180° next to north, and is negative counter-clockwise (to east), reaching -180° next to north [21]. Hence, γ=90° corresponds to a module with west-oriented front, while γ=-90° identifies an east-oriented front.

- The tilt angle of the module front β, which is the inclination with respect to the horizontal plane.

- The solar declination δ and the hour angle ω computed by block #1.

- The azimuth angle of the module rear γrear=γ-180°.

- The tilt angle of the module rear as the complement of β, that is, βrear=180°-β.

2.3. Block #3

- The solar altitude α evaluated by block #1.

- The azimuth angles γ, γrear, the tilt angles β, βrear, and the incidence angles θ, θrear.

- The total irradiance Gtoth, the diffuse irradiance Gdh hitting the horizontal plane (the beam, or direct, irradiance Gbh is determined as Gtoth-Gdh), and the ambient temperature Tamb vs. CKT at the selected geographical site. For the analysis performed in Section 3, these data were taken from the PhotoVoltaic Geographical Information System (PVGIS) website [28]. Here it is stated that they were evaluated for the mean day of the chosen month from satellite data through a sophisticate algorithm accounting for sky obstruction (shading) by local terrain features (hills or mountains) calculated from a digital elevation model.

- The albedo value, namely, the ratio of reflected upward radiation from the ground to the incident downward radiation upon it (typical albedo values are 0.04 for fresh asphalt, 0.1-0.15 for soil ground, 0.25-0.3 for green grass, 0.4 for desert sand, 0.55 for fresh concrete, and 0.8 for freshly fallen snow).

- Some key parameters available in the datasheet, i.e., the temperature TNOCT, the short circuit current Iscnom, and the percentage temperature coefficient TCIsc of the short-circuit current Isc, the definitions of which will be provided in the following.

- The block calculates

- The diffuse irradiance on the front coming from the sky, for which there are two options.

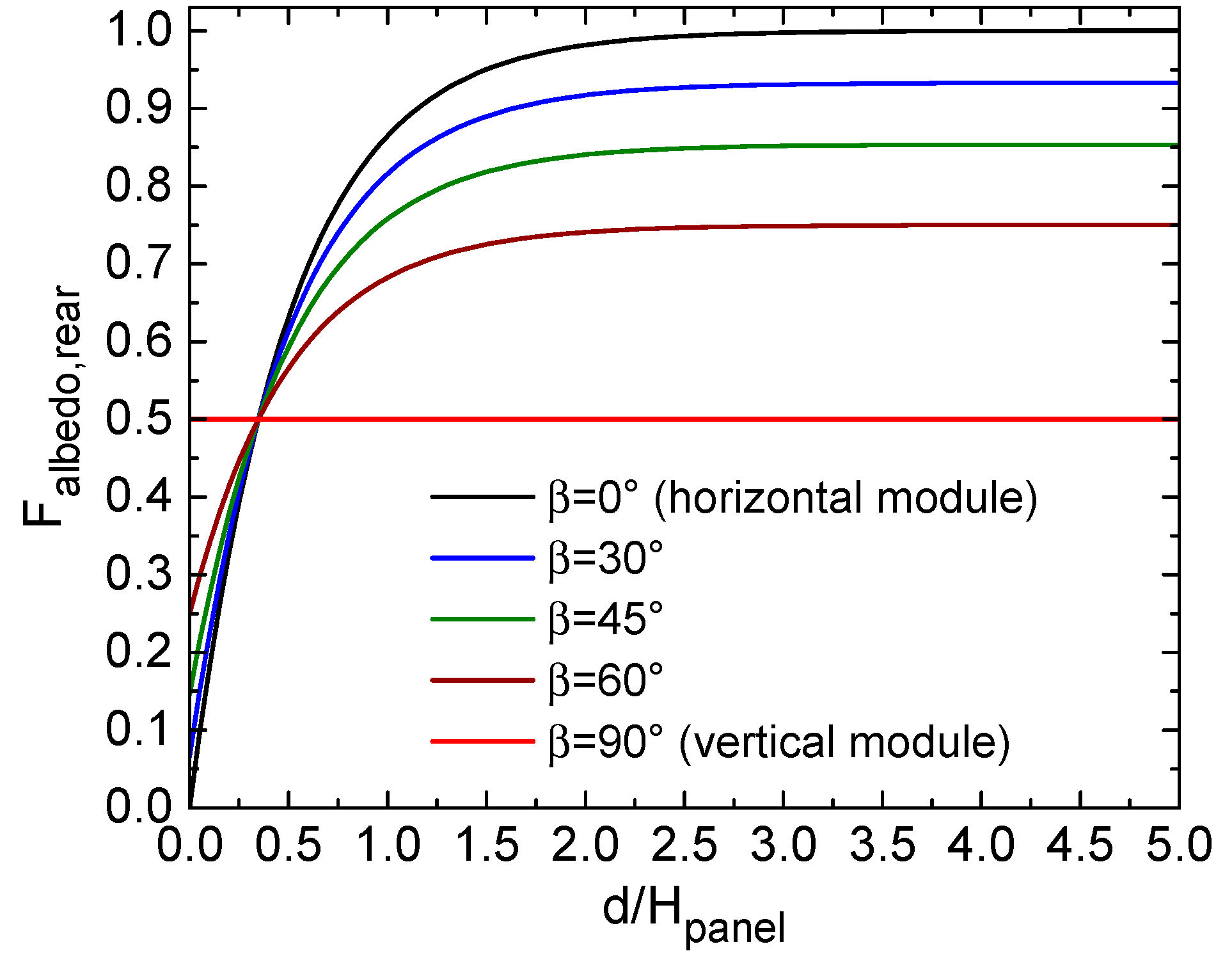

- The diffuse irradiance on the front due to the reflection from the ground, typically considered as a Lambertian (isotropic) process, calculated as

- The total irradiances on the front (G) and rear (Grear). The total irradiance on the front is calculated as

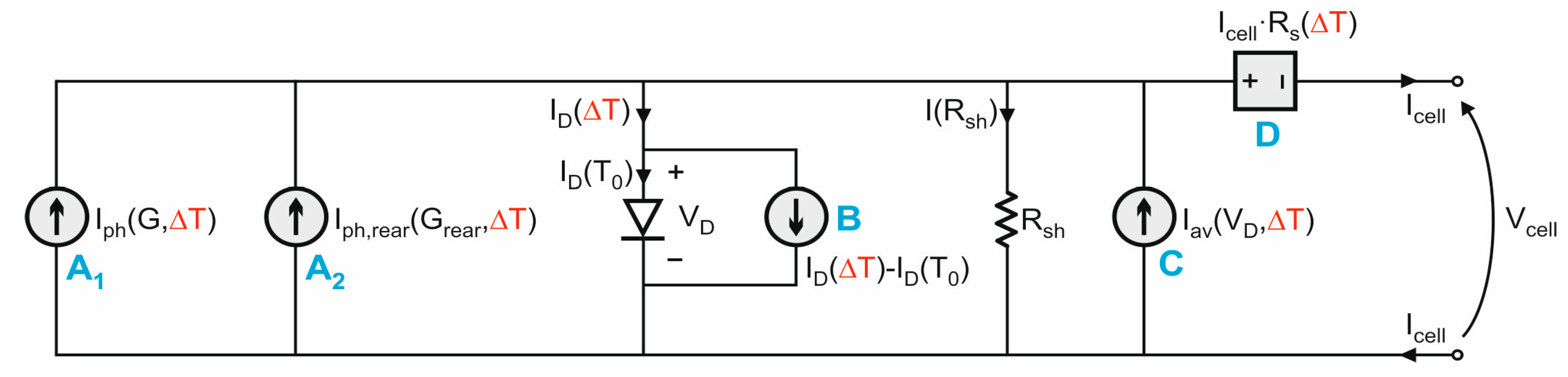

2.4. Block #4

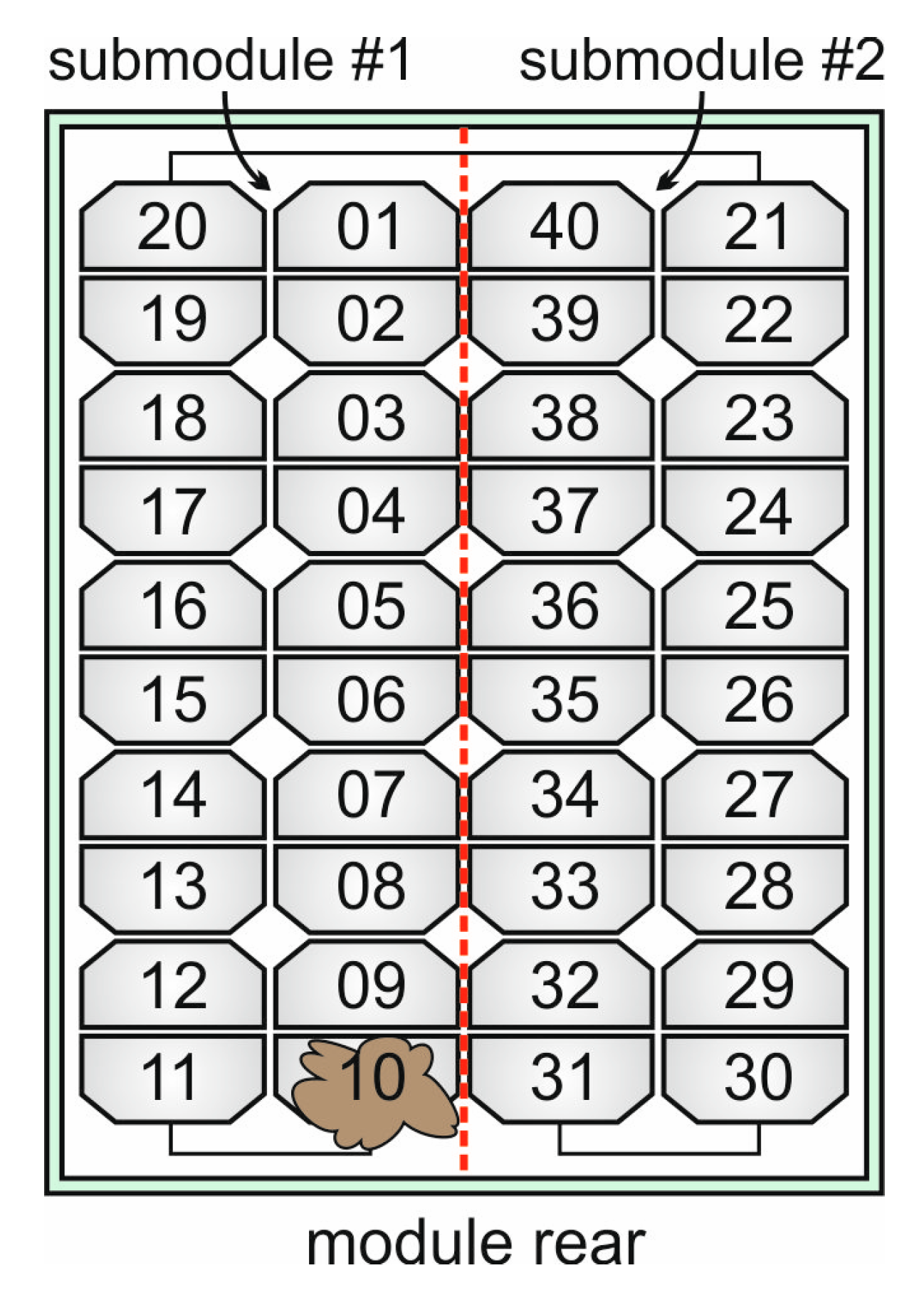

- The module is composed by N series-connected cells, each modeled with a subcircuit implementing the SDM described above, which is fed with G, Grear, ΔT.

- The module can be partitioned into a chosen number of subpanels, each equipped with a bypass diode.

- The PSPICE temperature of all components embedded in the circuit is forced to the reference value T0=27°C; the temperature rise ΔT, represented as a voltage, is provided to analog behavioral modeling, or ABM, components (nonlinear current/voltage sources) to modify the temperature-sensitive parameters.

2.5. Simplified variant of the tool for monofacial modules

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optimization of Orientation and Tilt for a Bifacial Module

- By specifically referring to the monofacial module, the energy produced by orienting the frontside to west is slightly better than the one obtained by orienting it to east; this result is reasonable since Naples faces the sea to the west while mountains lie to the east.

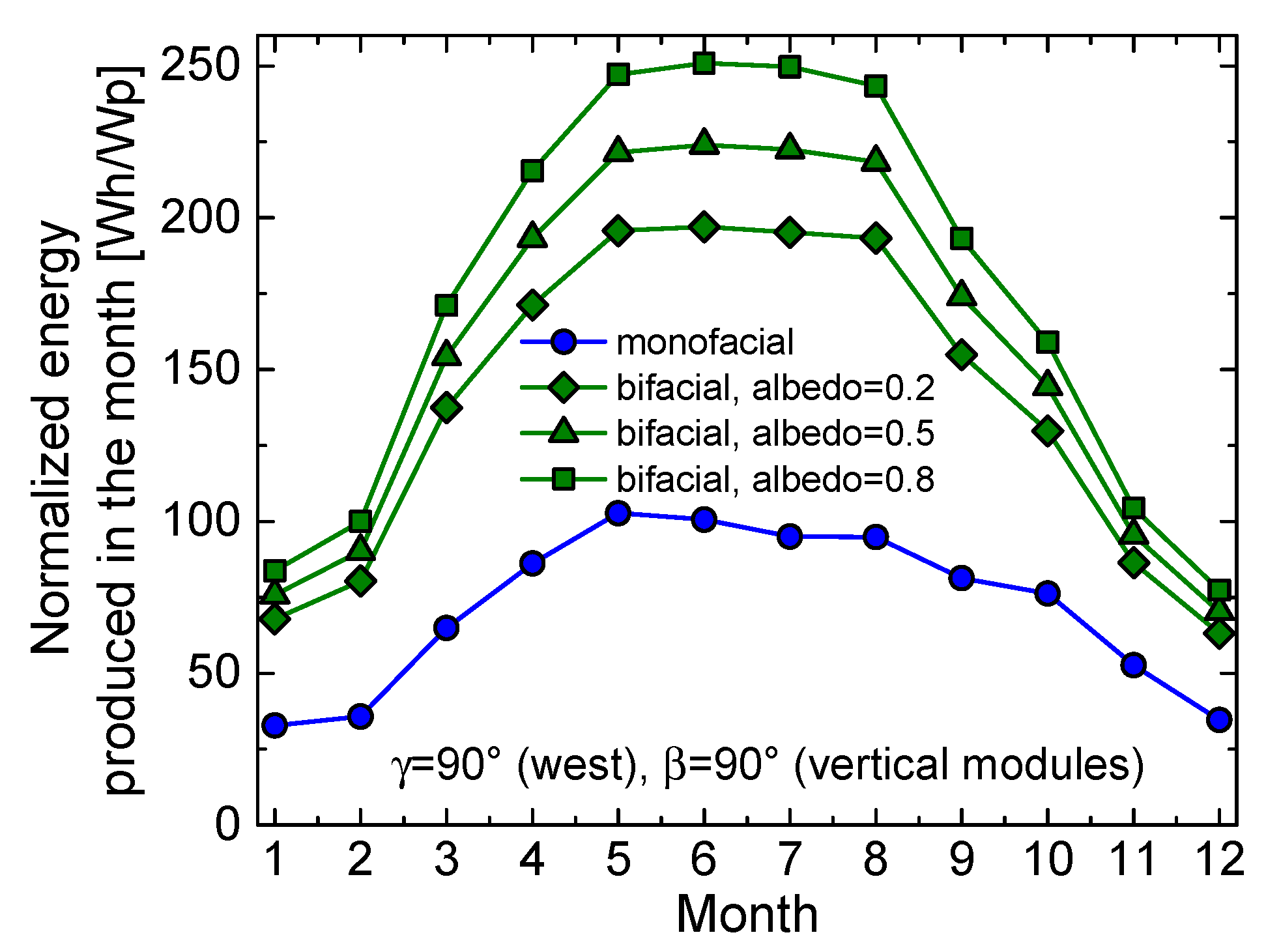

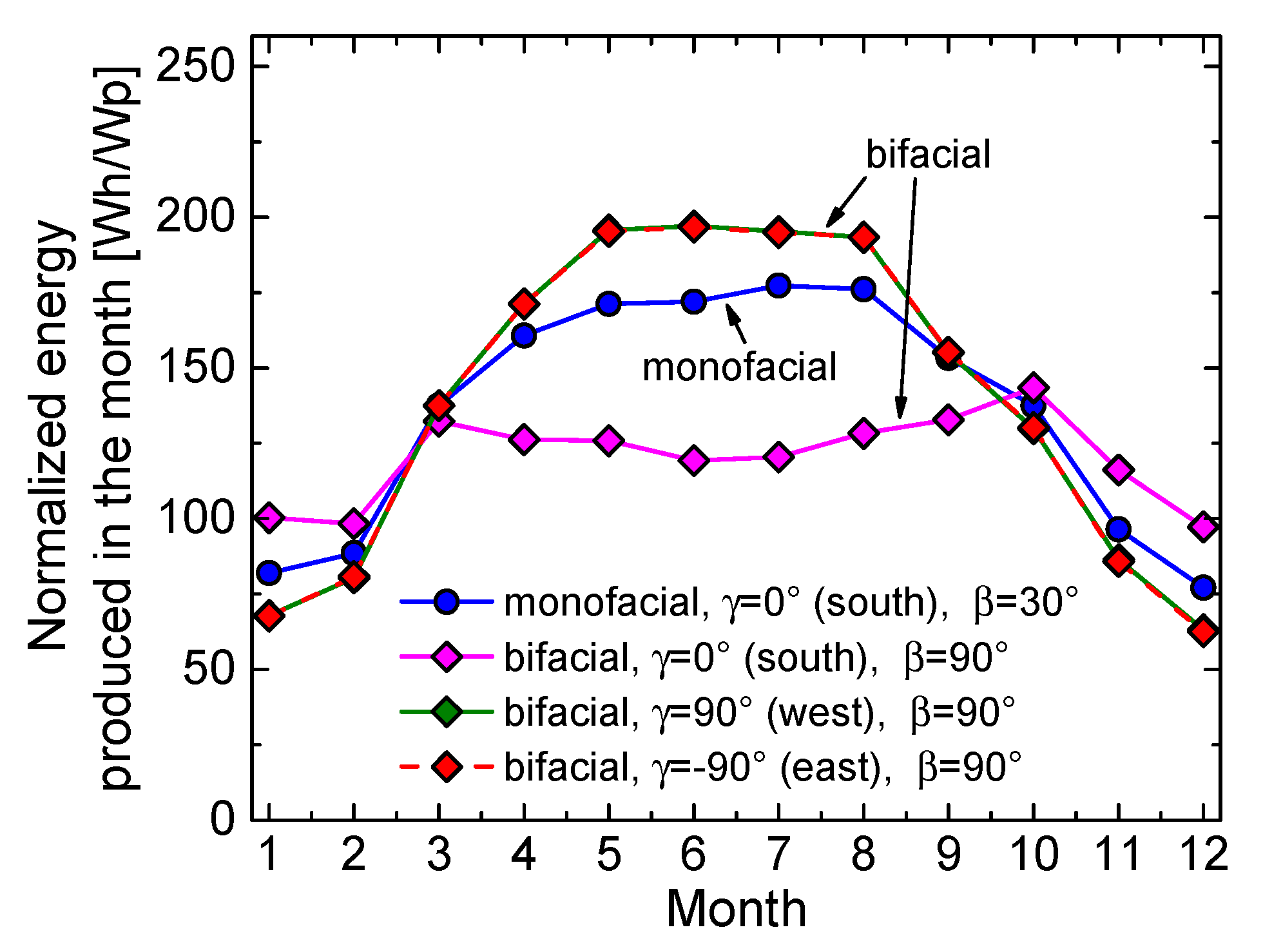

- As a main finding, it is observed that in these cases the bifacial module allows achieving a significant improvement. While the monofacial panel receives beam irradiance for only half of the day, bifacial panels benefit from effective beam irradiance (hitting the module sides with low incidence angles) both in the morning (rear for a west-oriented panel, as sketched in Figure 5b, and front for an east-oriented one) and afternoon (the other way around).

- West- and east-oriented vertical bifacial panels produce the same amount of energy.

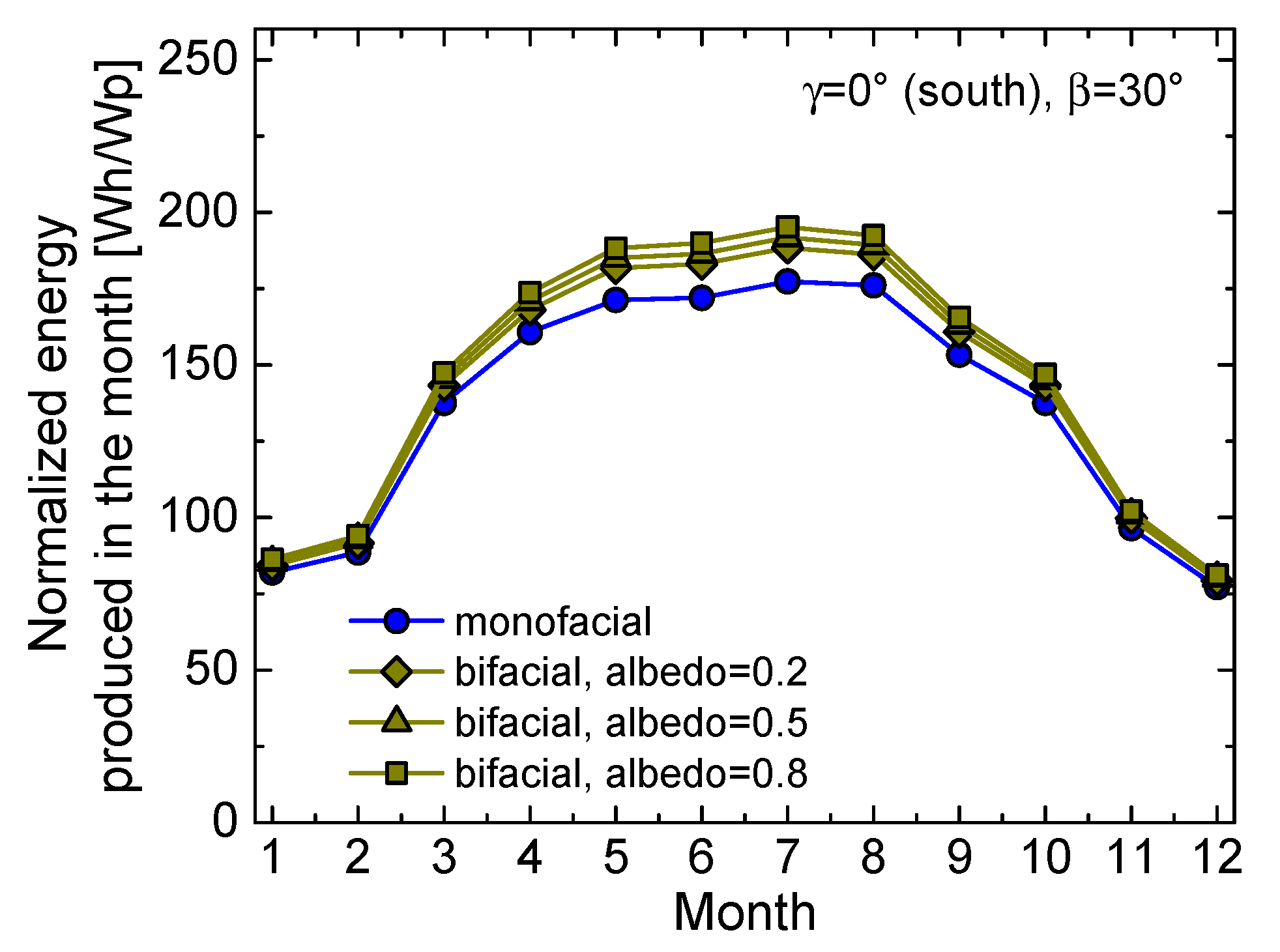

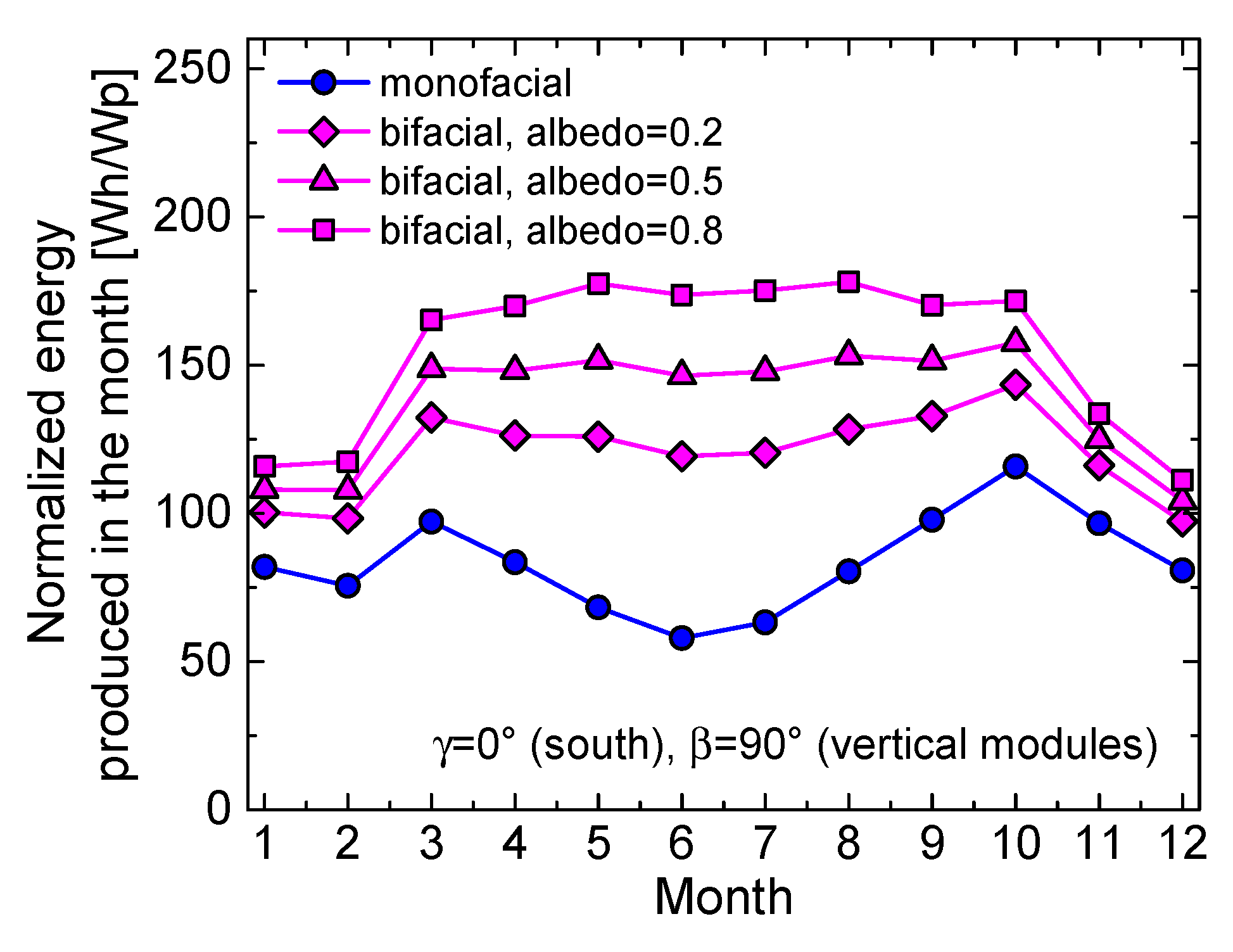

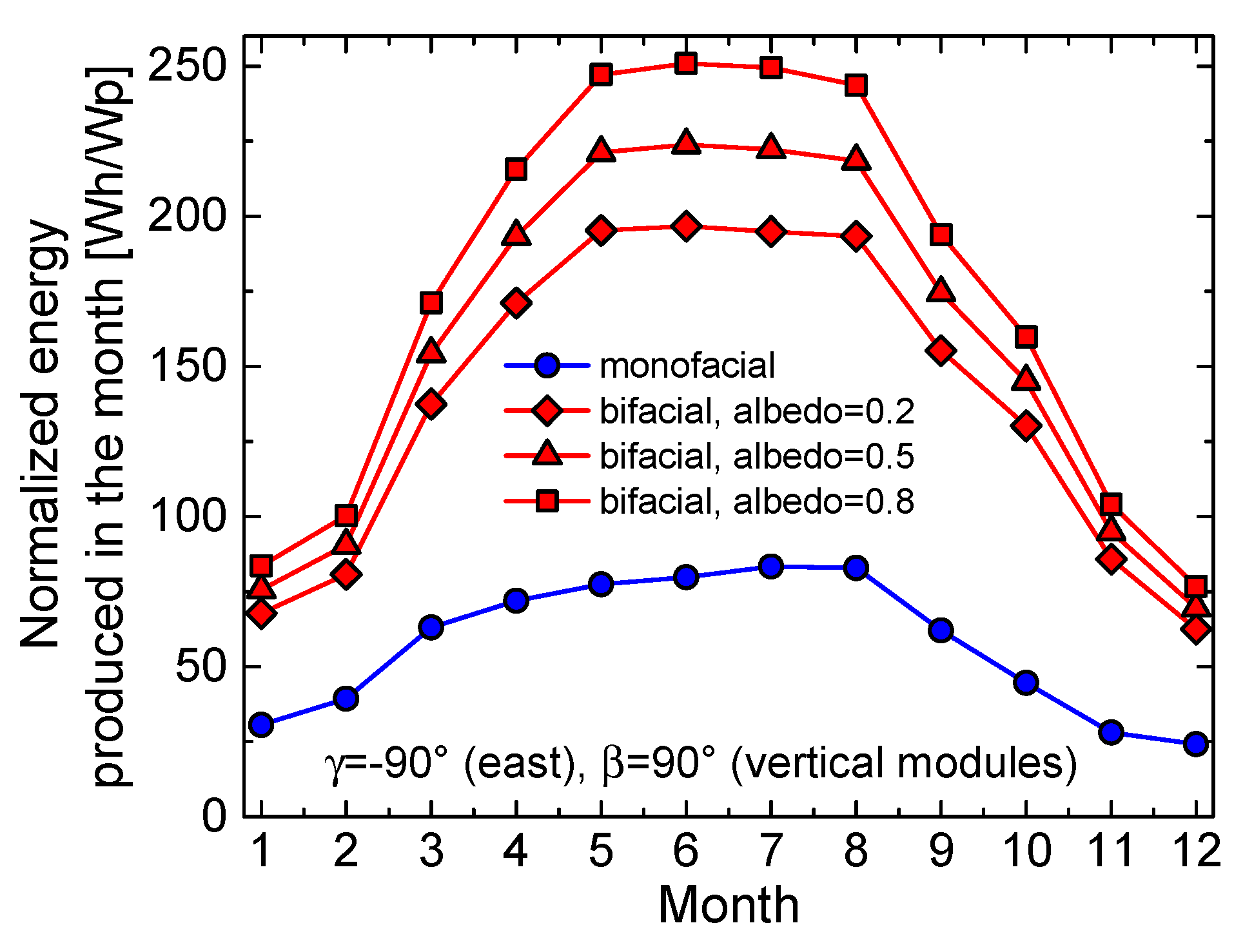

- West- and east-oriented vertical bifacial modules (which produce the same energy) offer equal or even improved performance with respect to the reference monofacial counterpart during the time span from April to September, in which they benefit from a low incidence angle of the Sun rays hitting the front and rear of the panel in the mid-morning and the mid-afternoon [1,10]. In terms of yearly energies (all reported in Table 2), the gain compared to the reference monofacial case amounts to 2.5% and 15% for albedo values equal to 0.2 and 0.5, respectively.

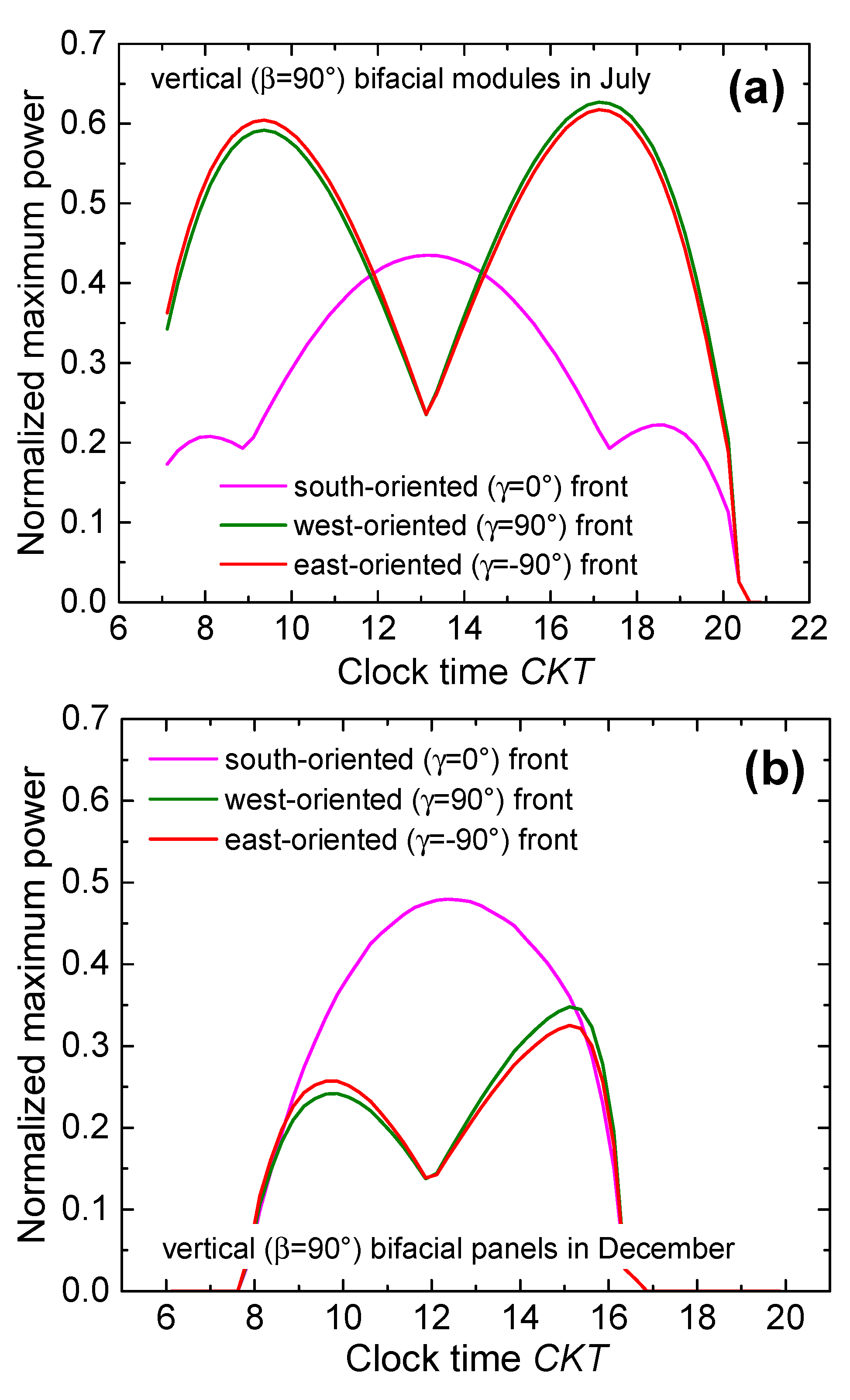

- West- and east-oriented vertical bifacial modules also provide a considerable production improvement with respect to the south-oriented vertical bifacial counterpart, which is estimated to be 13-15%, regardless of the albedo. This is again due to the much better performance of west- and east-oriented panels from April to September, while during wintertime the south-oriented module performs better. An in-depth insight into this behavior can be achieved by showing the normalized maximum power over CKT on July 15 (Figure 11a) and December 15 (Figure 11b) for such cases. In July (and more in general during the whole period from late spring to early autumn), it is confirmed that the orientations of the module front to west and east allow for a very effective exploitation of the beam light impinging on one of the two sides in the mid-morning and on the other in the mid-afternoon, whereas in December (and more in general during wintertime) the orientation to south is better over the mid-day. Along the whole year, the first effect markedly prevails over the second.

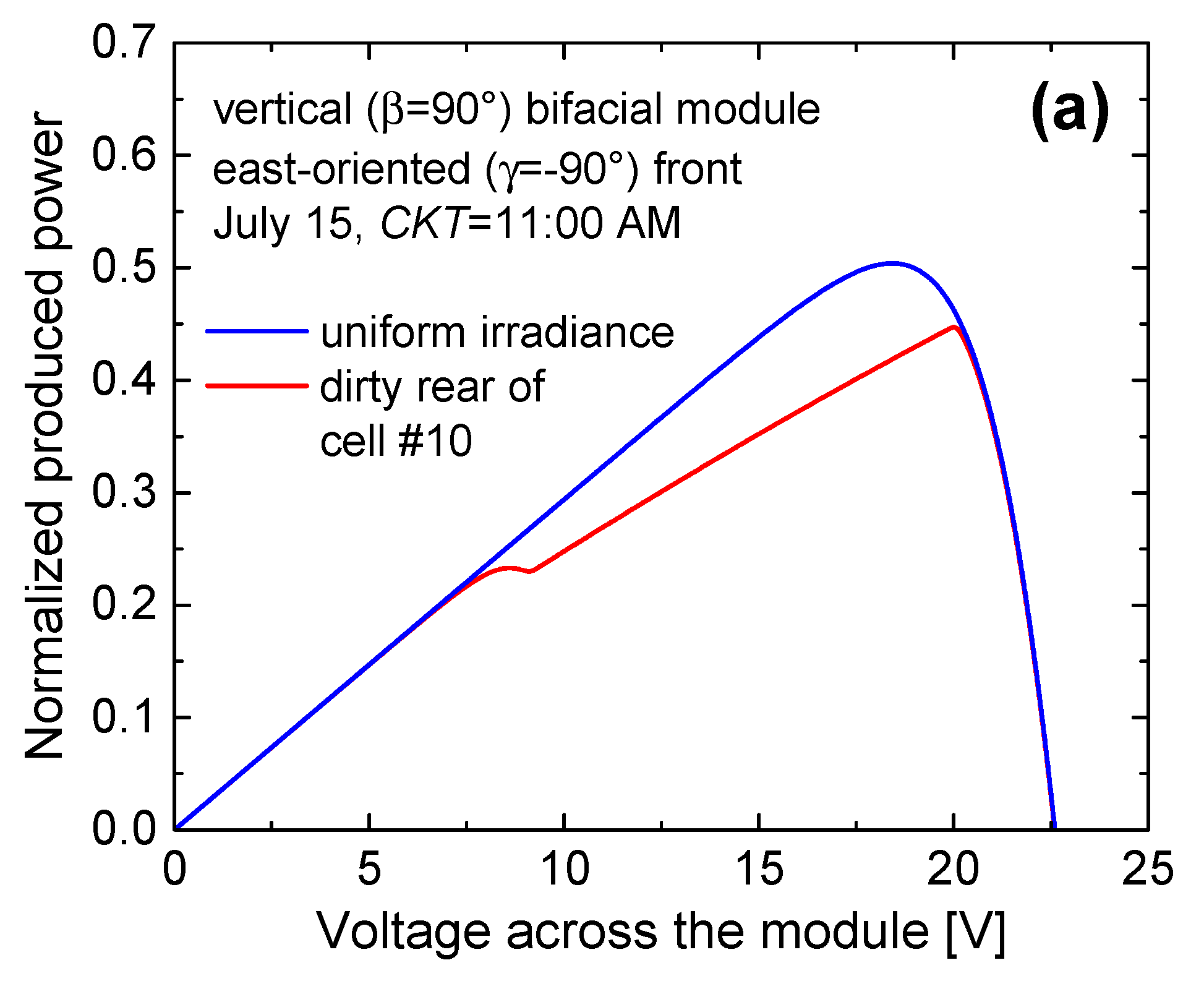

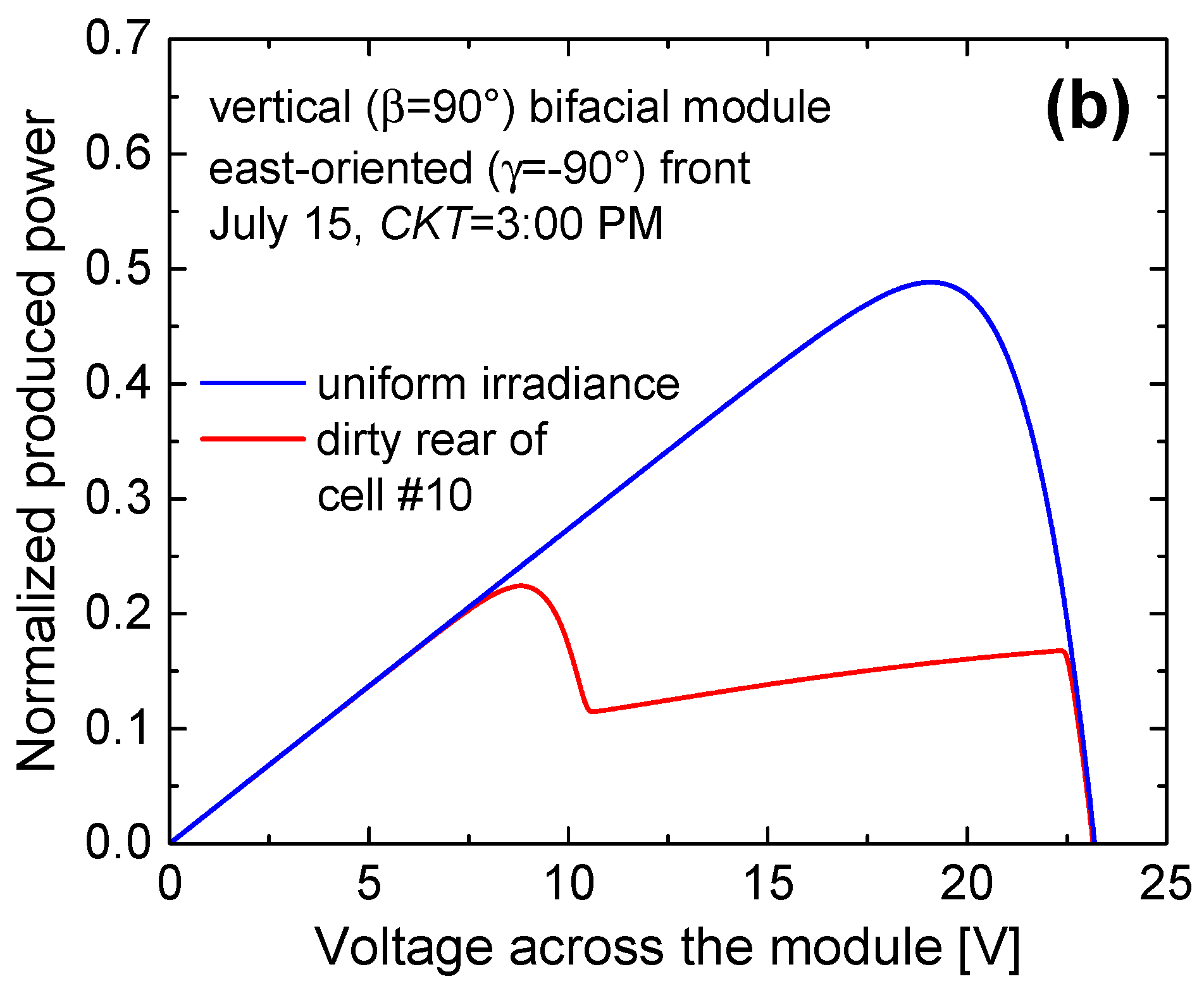

3.2. Nonuniform Irradiance Distribution over the Panel Rear

- G=370.49 W/m2, T=38.55°C, Iph=1.064 A, Grear=153.33 W/m2, Iph,rear=0.408 A at 11:00 AM;

- G=88.23 W/m2, T=31.5°C, Iph=0.259 A, Grear=436.45 W/m2, Iph,rear=1.114 A at 3:00 PM.

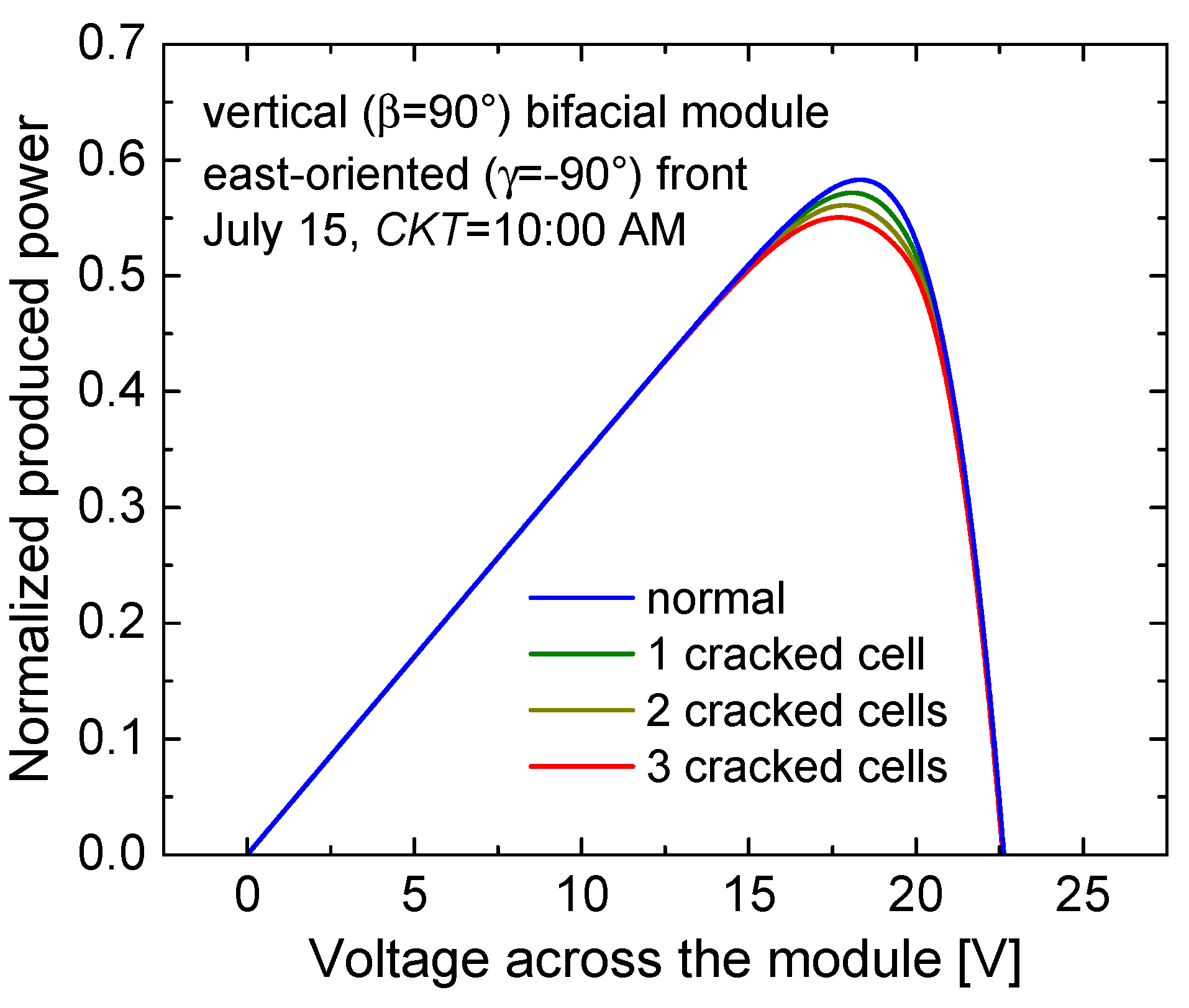

3.3. Cracked Cell(s)

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, S.; Walsh, T.M.; Peters, M. Vertically mounted bifacial photovoltaic modules: A global analysis. Energy 2013, 61, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, J. Bifacial photovoltaic panels field. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Lemus, R.; Vega, R.; Kim, T.; Kimm, A.; Shephard, L.E. Bifacial solar photovoltaics – A technology review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 60, 1533–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Khan, M.R.; Hussain, M.M.; Alam, M.A. The potential of bifacial photovoltaics: A global perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Washington, NY, USA, 25–30 June 2017; pp. 1055–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Deline, C.; MacAlpine, S.; Marion, B.; Toor, F.; Asgharzadeh, A.; Stein, J.S. Assessment of bifacial photovoltaic module power rating methodologies–Inside and out. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2017, 7, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Ma, T.; Ahmed, S.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, J. A comprehensive review and outlook of bifacial photovoltaic (bPV) technology. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 223, 113283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopecek, R.; Libal, J. Bifacial photovoltaics 2021: Status, opportunities and challenges. Energies 2021, 14, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchakour, S.; Valencia-Caballero, D.; Luna, A.; Roman, E.; Boudjelthia, E.A.K.; Rodriguez, P. Modelling and simulation of bifacial PV production using monofacial electrical models. Energies 2021, 14, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouhib, E.; Micheli, L.; Almonacid, F.M.; Fernández, E.F. Overview of the fundamentals and applications of bifacial photovoltaic technology: Agrivoltaics and aquavoltaics. Energies 2022, 15, 8777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrod, A.; Ghosh, A. A review of bifacial solar photovoltaic applications. Front. Energy 2023, 17, 704–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhang, W.; Xie, L.; Zhao, O.; Wu, X.; Zeng, X. Development and challenges of bifacial photovoltaic technology and application in buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 187, 113706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Gallegos, C.D.; Bieri, M.; Gandhi, O.; Singh, J.P.; Reindl, T.; Panda, S.K. Monofacial vs bifacial Si-based PV modules: Which one is more cost effective? Solar Energy 2018, 176, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Ma, T.; Li, M.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Y. A coupled optical-electrical-thermal model of the bifacial photovoltaic module. Applied Energy 2020, 258, 114075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, O.; Jamra, M.; Jaber, A.; Ahmad, L.; Alnaqep, M. An experimental comparison of bifacial and monofacial PV modules. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Renewable Engineering Conference (IREC), Amman, Jordan, 14–15 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tina, G.M.; Bontempo Scavo, F.; Merlo, L.; Bizzarri, F. Comparative analysis of monofacial and bifacial photovoltaic modules for floating power plants. Applied Energy 2021, 281, 116084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarneh, G.A.; Al-Rawajfeh, M.A.; Gomaa, M.R. Comparison review between monofacial and bifacial solar modules. Technology Audit and Production Reserves – Alternat. Renew. Energy Sources 2022, 6, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidiani, M.; Zeynal, H.; Ghavami, A.; Zakaria, Z. Comparative analysis of mono-facial and bifacial photovoltaic modules for practical grid-connected solar power plant using PVsyst. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Power and Energy (PECon), Langkawi, Kedah, Malaysia, 5–6 December 2022; pp. 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- Juaidi, A.; Kobari, M.; Mallak, A.; Titi, A.; Abdallah, R.; Nassar, M.; Albatayneh, A. A comparative simulation between monofacial and bifacial PV modules under Palestine conditions. Solar Compass 2023, 8, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PSPICE user’s manual, Cadence OrCAD 16.5, 2011.

- Eicker, U. Solar Technologies for Buildings; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Chichester, West Sussex, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A. Solar Engineering of Thermal Processes; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, G.N.; Dubey, S. Fundamentals of Photovoltaic Modules and their Applications; The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC): Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Passias, D.; Källbäck, B. Shading effects in rows of solar cell panels. Solar Cells 1984, 11, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, J.; Bany, J. Shadow effect of adjacent solar collectors in large scale systems. Solar Energy 1979, 23, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bany, J.; Appelbaum, J. The effect of shading on the design of a field of solar collectors. Solar Cells 1987, 20, 201–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messenger, R.A.; Ventre, J. Photovoltaic System Engineering, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sadineni, S.B.; Boehm, R.F.; Hurt, R. Spacing analysis of an inclined solar collector field. In Proceedings of the ASME 2nd International Conference on Energy Sustainability, Jacksonville, FL, USA, 10–14 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- PVGIS – PhotoVoltaic Geographical Information System. Available online: https://pvgis.com/ (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Reindl, D.T.; Beckman, W.A.; Duffie, J.A. Evaluation of hourly tilted surface radiation models. Solar Energy 1990, 45, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaschning, V.; Hanitsch, R. Shade calculations in photovoltaic systems. In Proceedings of the ISES Solar World Conference, Harare, Zimbabwe, 11–15 September 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Lu, L. The optimum tilt angles and orientations of PV claddings for building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) applications. ASME J. Solar Energy Engineering 2007, 129, 253–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottel, H.C.; Sarofim, A.F. Radiative Transfer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Kondrat’yev, K.Ya. Radiative Heat Exchange in the Atmosphere; Pergamon Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.Y.H.; Jordan, R.C. A rational procedure for predicting the long-term average performance of flat-plate solar-energy collectors – With design data for the U.S., its outlying possessions and Canada. Solar Energy.

- Garnier, B.J.; Ohmura, A. The evaluation of surface variations in solar radiation income. Solar Energy 1970, 13, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, E. Determining optimum tilt angles of photovoltaic panels at typical north-tropical latitudes. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2009, 1, 033104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueymard, C.A. Direct and indirect uncertainties in the prediction of tilted irradiance for solar engineering applications. Solar Energy 2009, 83, 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maor, T.; Appelbaum, J. View factors of photovoltaic collector systems. Solar Energy 2012, 86, 1701–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, V.; Magnani, A.; Codecasa, L.; Di Napoli, F.; Guerriero, P.; Daliento, S. Dynamic electrothermal simulation of photovoltaic plants. In Proceedings of the IEEE 5th International Conference on Clean Electrical Power (ICCEP), Taormina, Italy, 16–18 June 2015; pp. 682–688. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, J. The role of view factors in solar photovoltaic fields. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriero, P.; Codecasa, L.; d’Alessandro, V.; Daliento, S. Dynamic electro-thermal modeling of solar cells and modules. Solar Energy 2019, 179, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durusoy, B.; Ozden, T.; Akinoglu, B.G. Solar irradiation on the rear surface of bifacial solar modules. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakovec, J.; Zakšek, K. On the proper analytical expression for the sky-view factor and the diffuse irradiation of a slope for an isotropic sky. Renew. Energy 2012, 37, 440–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Dong, Z.; Nobre, A.; Khoo, Y.S.; Jirutitijaroen, P.; Walsh, W.M. Evaluation of transposition and decomposition models for converting global solar irradiance from tilted surface to horizontal in tropical regions. Solar Energy 2013, 97, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusufoglu, U.A.; Lee, T.H.; Pletzer, T.M.; Halm, A.; Koduvelikulathu, L.J.; Comparotto, C.; Kopecek, R.; Kurz, H. Simulation of energy production by bifacial modules with revision of ground reflection. Energy Procedia 2014, 55, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.; Gul, M.S.; Muneer, T. Ground view factor computation model for bifacial photovoltaic collector field: uniform and non-uniform surfaces. Energy Reports 2021, 7, 9133–9149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-L. Insolation-oriented model of photovoltaic module using Matlab/Simulink. Solar Energy 2010, 84, 1318–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, V.; Di Napoli, F.; Guerriero, P.; Daliento, S. An automated high-granularity tool for a fast evaluation of the yield of PV plants accounting for shading effects. Renew. Energy 2015, 83, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschenbach, H.S. Solar Cell Array Design Handbook – The Principles and Technology of Photovoltaic Energy Conversion; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- d’Alessandro, V.; Di Napoli, F.; Guerriero, P.; Daliento, S. A novel circuit model of PV cell for electrothermal simulations. Proceedings of 3rd Renewable Power Generation (RPG) conference, Naples, Italy, 24–25 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, J.W. Computer simulation of the effects of electrical mismatches in photovoltaic cell interconnection circuits. Solar cells 1988, 25, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, V.; Sasso, G.; Rinaldi, N.; Aufinger, K. Thermal behavior of toward-THz SiGe:C HBTs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2014, 61, pp–3386. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Andreson, W.A. Temperature dependence of shunt resistance in photovoltaic devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1986, 49, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Cheng, X.; Fu, T. Analysis of series resistance and P–T characteristics of the solar cell. Vacuum 2005, 77, 163–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.P.; Scognamillo, C.; Guerriero, P.; Daliento, S.; d’Alessandro, V. Using EMPHASIS for the thermography-based fault detection in photovoltaic plants. Energies 2021, 14, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, H. Operating experience with solar water heating. J. Inst. Heat. Vent. Eng. 1971, 39, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Gueymard, C.A.; Myers, D. Solar resource for space and terrestrial application, Chapter 19 in Solar Cells and their Applications, 2nd ed.; Fraas, L, Partain, L., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; pp. 427–461. [Google Scholar]

- Dhimish, M.; d’Alessandro, V.; Daliento, S. Investigating the impact of cracks on solar cells performance: Analysis based on nonuniform and uniform crack distributions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2022, 18, 1684–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Naples Italy |

Stuttgart Germany [20] |

Madison WI, USA [21] |

Cape Town South Africa |

|---|---|---|---|

|

inputs ϕ=40°50’ λlocal=14°15’ λstandard=15° July 15 (n=196), CKT=16 (4:00 PM) daylight-saving time |

inputs ϕ=48°46’ λlocal=9°10’ λstandard=15° July 1 (n=182), CKT=12 (12:00 AM) daylight-saving time |

inputs ϕ=43°04’ λlocal=-89°-23’ λstandard=-90° February 3 (n=34), CKT=10.5 (10:30 AM) standard time |

inputs ϕ=-33°-55’ λlocal=18°25’ λstandard=30° December 10 (n=344), CKT=9.25 (9:15 AM) standard time |

|

outputs δ=21.52° Eqt=-5.79 minutes TLT=14.85 (2:51 PM) ω=42.80° α=49.13° |

outputs δ=23.12° Eqt=-3.46 minutes TLT=10.55 (10:33 AM) ω=-21.70° α=59.15° |

outputs δ=-16.97° Eqt=-13.49 minutes TLT=10.32 (10:19 AM) ω=-25.26° α=25.64° |

outputs δ=-23.05° Eqt=7.14 minutes TLT=8.60 (8:36 AM) ω=-51.05°α=44.31° |

| Orientation (γ) and tilt (β) | Normalized yearly-produced energy [Wh/Wp] | |

|---|---|---|

| Monofacial | Bifacial | |

| γ=0° (south), β=30° | 1630 (reference) | 1709 (albedo=0.2) 1736 (albedo=0.5) 1763 (albedo=0.8) |

| γ=0° (south), β=90° | 1000 | 1440 (albedo=0.2) 1650 (albedo=0.5) 1860 (albedo=0.8) |

| γ=90° (west), β=90° | 855 | 1670 (albedo=0.2) 1880 (albedo=0.5) 2095 (albedo=0.8) |

| γ=-90° (east), β=90° | 685 | 1670 (albedo=0.2) 1880 (albedo=0.5) 2095 (albedo=0.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).