Submitted:

21 October 2025

Posted:

22 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Soil Sampling

2.3. Microcosm Experiment

2.4. DNA Extraction and Amplicon Sequencing

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Biogeochemical Changes During Short Pulse Precipitation

3.2. The Impact of Pulse Precipitation on Soil Microbial Abundances and Diversity

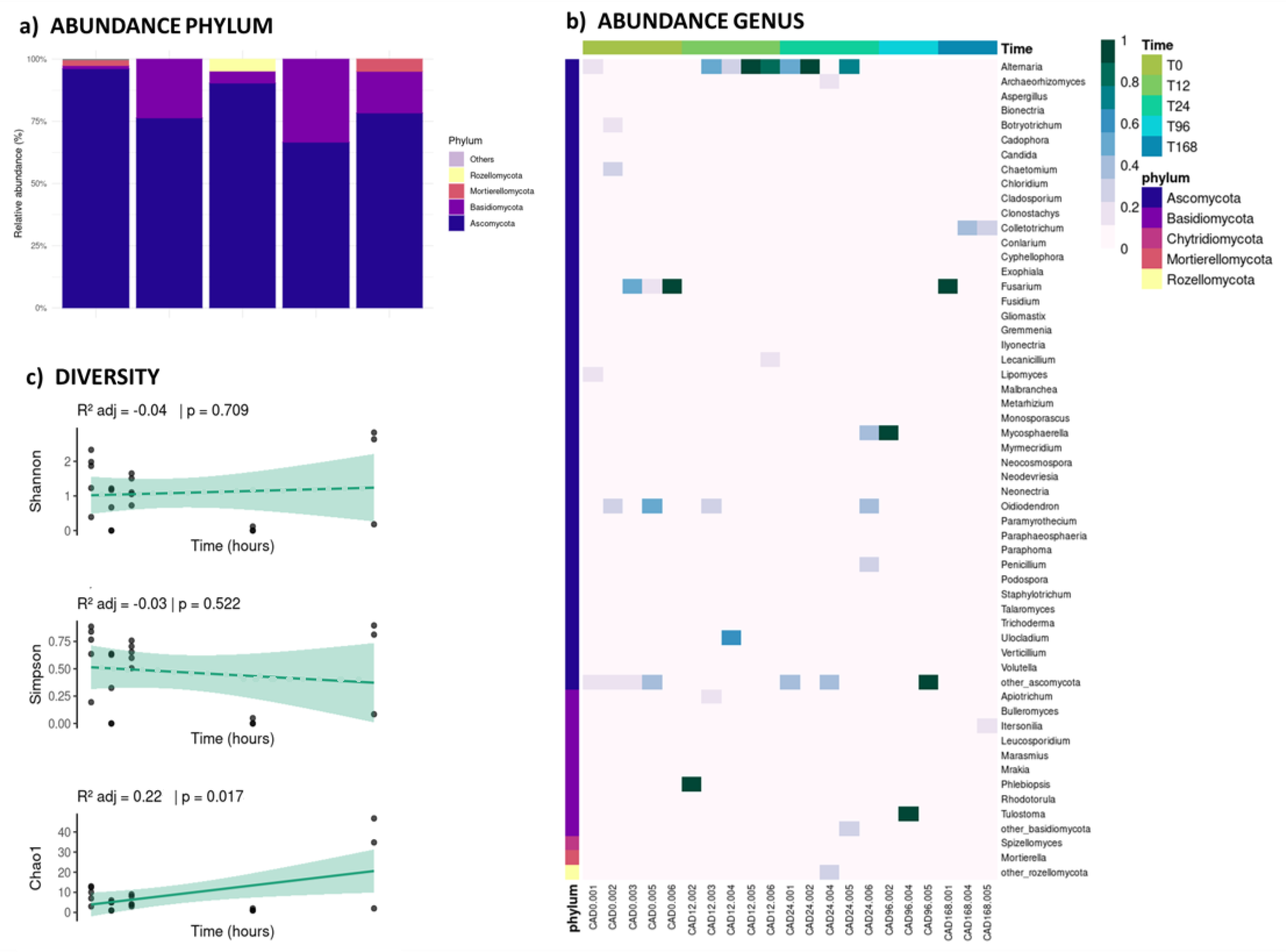

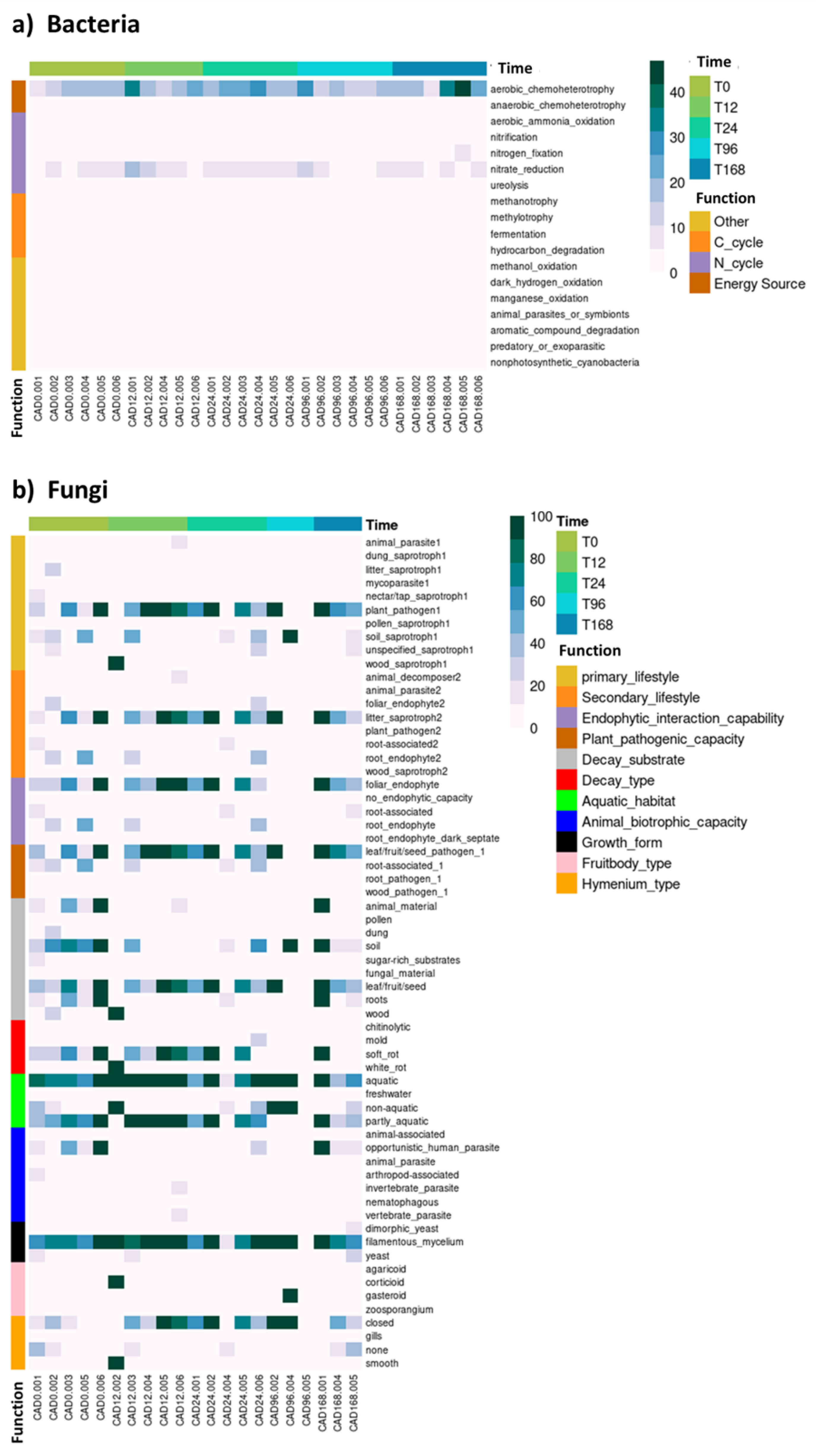

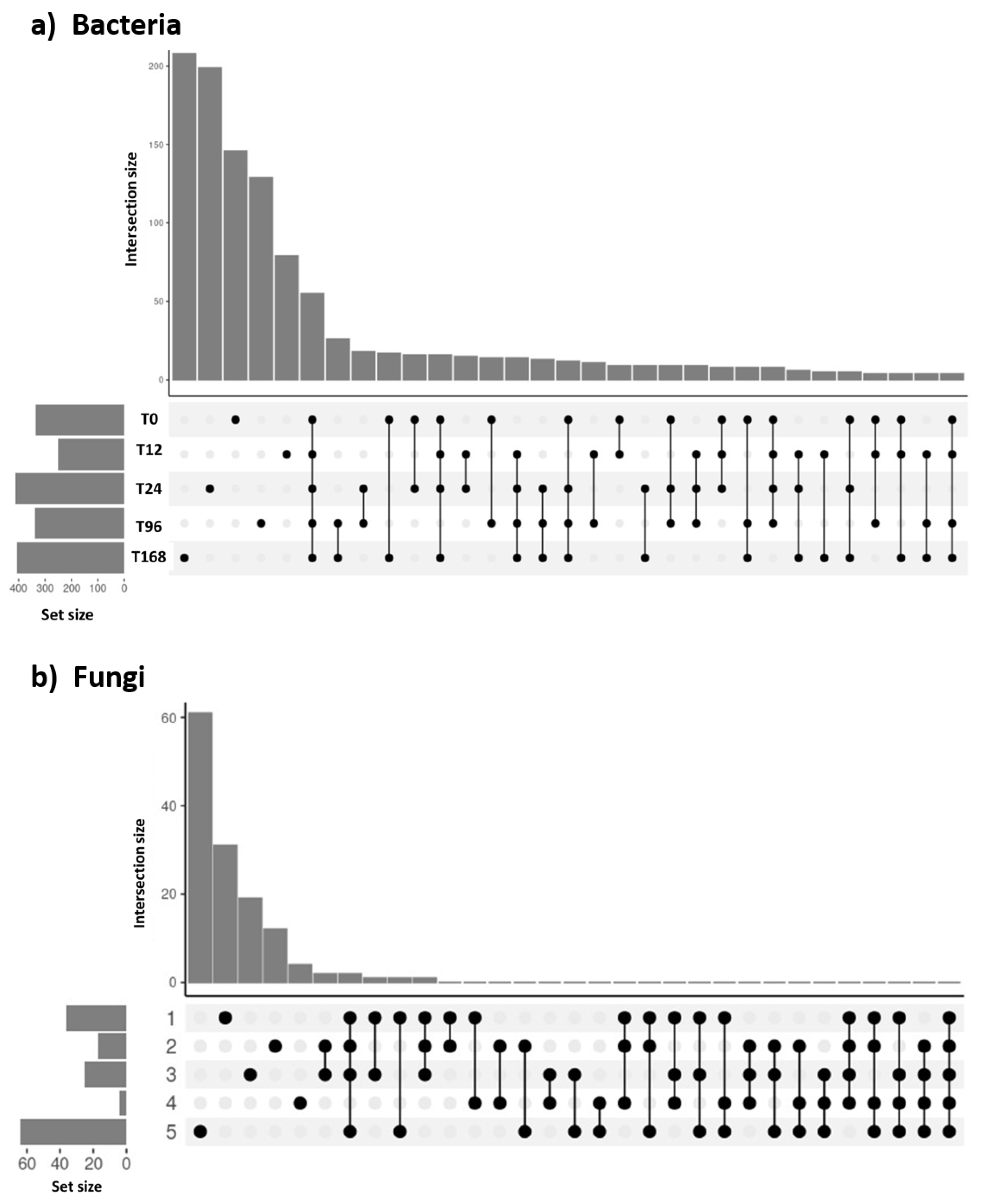

3.3. The Impact of Pulse Precipitation on Soil Microbial Composition and Function

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Milena Holmgren, Paul Stapp, Chris R. Dickman, Carlos Gracia, Sonia Graham, Julio R. Gutiérrez, Christine Hice, Fabián Jaksic, Douglas A. Kelt, Mike Letnic, Mauricio Lima, Bernat C. López, Peter L. Meserve, W Bryan Milstead, Gary A. Polis, M Andrea Previtali, Michael Richter, Santi Sabaté, Francisco A. Squeo. Extreme Climatic Events Shape Arid and Semiarid Ecosystems. Frontiers in Ecology and the. 2006;4(2):87–95. [CrossRef]

- Orlando J, Alfaro M, Bravo L, Guevara R, Carú M. Bacterial diversity and occurrence of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in the Atacama Desert soil during a “desert bloom” event. Soil Biol Biochem. 2010;42(7):1183–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang X-B, Azarbad H, Leclerc L, Dozois J, Mukula E, Yergeau É. A drying-rewetting cycle imposes more important shifts on soil microbial communities than does reduced precipitation. mSystems. 2022;7(4):e0024722. [CrossRef]

- Prăvălie R. Drylands extent and environmental issues. A global approach. Earth Sci Rev. 2016;161:259–78. [CrossRef]

- Plaza C, Zaccone C, Sawicka K, Méndez AM, Tarquis A, Gascó G, et al. Soil resources and element stocks in drylands to face global issues. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13788. [CrossRef]

- Huang J, Yu H, Guan X, Wang G, Guo R. Accelerated dryland expansion under climate change. Nat Clim Chang. 2016;6(2):166–71. [CrossRef]

- Mirzabaev A, Annagylyjova J, Amirova I. Environmental degradation. In: The Aral Sea Ba-sin. Routledge; 2019. p. 67–85.

- Noy-Meir I. Desert ecosystems: Environment and producers. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1973;4(1):25–51. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds JF, Kemp PR, Ogle K, Fernández RJ. Modifying the ‘pulse–reserve’ paradigm for deserts of North America: precipitation pulses, soil water, and plant responses. Oecologia. 2004;141(2):194–210. [CrossRef]

- Collins SL, Sinsabaugh RL, Crenshaw C, Green L, Porras-Alfaro A, Stursova M, et al. Pulse dynamics and microbial processes in aridland ecosystems: Pulse dynamics in aridland soils. J Ecol. 2008;96(3):413–20. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Pichel F, Sala O. Expanding the pulse–reserve paradigm to microorganisms on the basis of differential reserve management strategies. Bioscience. 2022;72(7):638–50. [CrossRef]

- Kut P, Garcia-Pichel F. Nimble vs. torpid responders to hydration pulse duration among soil microbes. Commun Biol. 2024;7(1):455. [CrossRef]

- Collins SL, Belnap J, Grimm NB, Rudgers JA, Dahm CN, D’Odorico P, et al. A multiscale, hierarchical model of pulse dynamics in arid-land ecosystems. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45(1):397–419. [CrossRef]

- Št’ovíček A, Azatyan A, Soares MIM, Gillor O. The impact of hydration and temperature on bacterial diversity in arid soil mesocosms. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1078. [CrossRef]

- Šťovíček A, Kim M, Or D, Gillor O. Microbial community response to hydration-desiccation cycles in desert soil. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45735. [CrossRef]

- Dion P, Nautiyal CS, editors. Microbiology of extreme soils. 2008th ed. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2014.

- Houston J, Hartley AJ. The central Andean west-slope rainshadow and its potential contribution to the origin of hyper-aridity in the Atacama Desert. Int J Climatol. 2003;23(12):1453–64. [CrossRef]

- Miller FP, Vandome AF, McBrewster J, editors. Climate of Chile. Alphascript Publishing; 2010.

- Leung PM, Bay SK, Meier DV, Chiri E, Cowan DA, Gillor O, et al. Energetic basis of microbial growth and persistence in desert ecosystems. mSystems. 2020;5(2). [CrossRef]

- Jaksic FM. Ecological effects of El Niño in terrestrial ecosystems of western South America. Ecography (Cop). 2001;24(3):241–50. [CrossRef]

- Araya JP, González M, Cardinale M, Schnell S, Stoll A. Microbiome dynamics associated with the Atacama flowering desert. Front Microbiol. 2020;10(3160). [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Harms J, Guerrero PC, Martínez-Harms MJ, Poblete N, González K, Stavenga DG, et al. Mechanisms of flower coloring and eco-evolutionary implications of massive blooming events in the Atacama Desert. Front Ecol Evol. 2022;10. [CrossRef]

- McKay CP, Friedmann EI, Gómez-Silva B, Cáceres-Villanueva L, Andersen DT, Landheim R. Temperature and moisture conditions for life in the extreme arid region of the Atacama desert: four years of observations including the El Niño of 1997-1998. Astrobiology. 2003 Summer;3(2):393–406. [CrossRef]

- García J-L, Lobos-Roco F, Schween JH, del Río C, Osses P, Vives R, et al. Climate and coastal low-cloud dynamic in the hyperarid Atacama fog Desert and the geographic distribution of Tillandsia landbeckii (Bromeliaceae) dune ecosystems. Osterr Bot Z. 2021;307(5). [CrossRef]

- Webster R. Soil sampling and methods of analysis - edited by M.r. carter & E.g. gregorich. Eur J Soil Sci. 2008;59(5):1010–1. [CrossRef]

- Eyherabide M, Rozas HS, Barbieri P, Echeverría H. Comparación de métodos para determinar carbono orgánico en suelo. 2014;32:13–9. https://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/cds/v32n1/v32n1a02.pdf.

- Nelson JT, Adjuik TA, Moore EB, VanLoocke AD, Ramirez Reyes A, McDaniel MD. A simple, affordable, do-it-yourself method for measuring soil maximum water holding capacity. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2024;55(8):1190–204. [CrossRef]

- Liu C, Cui Y, Li X, Yao M. microeco: an R package for data mining in microbial community ecology. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2021;97(2). [CrossRef]

- Dixon P. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J Veg Sci. 2003;14(6):927–30 [software]. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen NH, Song Z, Bates ST, Branco S, Tedersoo L, Menke J, et al. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016;20:241–8 [software]. [CrossRef]

- Wemheuer F, Taylor JA, Daniel R, Johnston E, Meinicke P, Thomas T, et al. Tax4Fun2: prediction of habitat-specific functional profiles and functional redundancy based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Environ Microbiome. 2020;15(1):11 [software]. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. 2025. https://www.R-project.org/.

- León-Sobrino C, Ramond J-B, Coclet C, Kapitango R-M, Maggs-Kölling G, Cowan DA. Temporal dynamics of microbial transcription in wetted hyperarid desert soils. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2024;100(3). [CrossRef]

- Worrich A, Stryhanyuk H, Musat N, König S, Banitz T, Centler F, et al. Mycelium-mediated transfer of water and nutrients stimulates bacterial activity in dry and oligotrophic environments. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):15472. [CrossRef]

- Iovieno P, Bååth E. Effect of drying and rewetting on bacterial growth rates in soil: Rewetting and bacterial growth in soil. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2008;65(3):400–7. [CrossRef]

- Wang X-B, Azarbad H, Leclerc L, Dozois J, Mukula E, Yergeau É. A drying-rewetting cycle imposes more important shifts on soil microbial communities than does reduced precipitation. mSystems. 2022;7(4):e0024722. [CrossRef]

- Krüger N, Finn DR, Don A. Soil depth gradients of organic carbon-13 – A review on drivers and processes. Plant Soil. 2024;495(1–2):113–36. [CrossRef]

- Brady NC, Weil RR. Elements of the nature and properties of soils. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson; 2018.

- Nawaz R, Parkpian P, Garivait H, Anurakpongsatorn P, DeLaune RD, Jugsujinda A. Impacts of acid rain on base cations, aluminum, and acidity development in highly weathered soils of Thailand. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal. 2012;43(10):1382–400. [CrossRef]

- Ramnarine R, Wagner-Riddle C, Dunfield KE, Voroney RP. Contributions of carbonates to soil CO2 emissions. Can J Soil Sci. 2012;92(4):599–607. [CrossRef]

- Knapp WJ, Tipper ET. The efficacy of enhancing carbonate weathering for carbon dioxide sequestration. Front Clim. 2022;4(928215). [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Zuo X, Awada T, Medima-Roldán E, Feng K, Yue P, et al. Changes of soil bacterial and fungal community structure along a natural aridity gradient in desert grassland ecosystems, Inner Mongolia. Catena. 2021;205(105470):105470. [CrossRef]

- Boer W de, Folman LB, Summerbell RC, Boddy L. Living in a fungal world: impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29(4):795–811. [CrossRef]

- Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(3):626–31. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Cao Z, Liu S, Hao Z, Zhang X, Sun G, et al. Soil fungal diversity, community structure, and network stability in the southwestern Tibetan Plateau. J Fungi (Basel). 2025;11(5). [CrossRef]

- Fernandes C, Casadevall A, Gonçalves T. Mechanisms of Alternaria pathogenesis in animals and plants. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2023;47(6). [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko IK, Tikhonova EN, Baslerov RV, Kolganova TV. Cultivable fungal diversity in The Forest soil during litter degradation: Microcosm study at different temperature regimes. Journal of Agriculture and Environment. 2022;2(22). [CrossRef]

- Abdullah M. Al-Sadi, Badriya Al-Khatri, Abbas Nasehi, Muneera Al-Shihi, Issa H. Al-Mahmooli, Sajeewa S.N. Maharachchikumbura. High Fungal Diversity and Dominance by Ascomycota in Dam Reservoir Soils of Arid Climates. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology. 2025;19(4):682–8.

- Egidi E, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Plett JM, Wang J, Eldridge DJ, Bardgett RD, et al. A few Ascomycota taxa dominate soil fungal communities worldwide. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2369. [CrossRef]

- Legeay J, Basiru S, Ziami A, Errafii K, Hijri M. Response of Alternaria and Fusarium species to low precipitation in a drought-tolerant plant in Morocco. Microb Ecol. 2024;87(1):127. [CrossRef]

- Crits-Christoph A, Robinson CK, Barnum T, Fricke WF, Davila AF, Jedynak B, et al. Colonization patterns of soil microbial communities in the Atacama Desert. Microbiome. 2013;1(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Nessner Kavamura V, Taketani RG, Lançoni MD, Andreote FD, Mendes R, Soares de Melo I. Water regime influences bulk soil and Rhizosphere of Cereus jamacaru bacterial communities in the Brazilian Caatinga biome. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73606. [CrossRef]

- Angel R, Conrad R. Elucidating the microbial resuscitation cascade in biological soil crusts following a simulated rain event: Microbial resuscitation in biological soil crusts. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15(10):2799–815. [CrossRef]

- Jordaan K, Lappan R, Dong X, Aitkenhead IJ, Bay SK, Chiri E, et al. Hydrogen-oxidizing bacteria are abundant in desert soils and strongly stimulated by hydration. mSystems. 2020;5(6). [CrossRef]

- Demergasso C, Neilson JW, Tebes-Cayo C, Véliz R, Ayma D, Laubitz D, et al. Hyperarid soil microbial community response to simulated rainfall. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1202266. [CrossRef]

- Ortega R, Miralles I, Domene MA, Meca D, Del Moral F. Ecological practices increase soil fertility and microbial diversity under intensive farming. Sci Total Environ. 2024;954(176777):176777. [CrossRef]

- 57Li Z, Liu X, Zhang M, Xing F. Plant diversity and fungal richness regulate the changes in soil multifunctionality in a semi-arid grassland. Biology (Basel). 2022;11(6):870. [CrossRef]

- Jiao S, Peng Z, Qi J, Gao J, Wei G. Linking bacterial-fungal relationships to microbial diversity and soil nutrient cycling. mSystems. 2021;6(2). [CrossRef]

- Wagg C, Schlaeppi K, Banerjee S, Kuramae EE, van der Heijden MGA. Fungal-bacterial diversity and microbiome complexity predict ecosystem functioning. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):4841. [CrossRef]

- Biggs CR, Yeager LA, Bolser DG, Bonsell C, Dichiera AM, Hou Z, et al. Does functional redundancy affect ecological stability and resilience? A review and meta-analysis. Ecosphere. 2020;11(7). [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Xi J, Xiao M, Wang S, Chen W, Liu F, et al. Soil fungal communities show more specificity than bacteria for plant species composition in a temperate forest in China. BMC Microbiol. 2022;22(1):208. [CrossRef]

- Fu F, Li Y, Zhang B, Zhu S, Guo L, Li J, et al. Differences in soil microbial community structure and assembly processes under warming and cooling conditions in an alpine forest ecosystem. Sci Total Environ. 2024;907(167809):167809. [CrossRef]

- Li J, Yang H, Duan YY, Dan Sun X, Pang XP, Guo ZG. Fungi contribute more than bacteria to the ecological uniqueness of soil microbial communities in alpine meadows. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2024;55(e03246):e03246. [CrossRef]

- Cuartero J, Querejeta JI, Prieto I, Frey B, Alguacil MM. Warming and rainfall reduction alter soil microbial diversity and co-occurrence networks and enhance pathogenic fungi in dryland soils. Sci Total Environ. 2024;949(175006):175006. [CrossRef]

- Frąc M, Hannula SE, Bełka M, Jędryczka M. Fungal biodiversity and their role in soil health. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:707. [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA). Ecosystems and human well-being: desertification synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC. 2005. https://www.millenniumassessment.org/documents/document.355.aspx.pdf.

- Liu Z, Wang G. Concept and methodology for Scope 4 carbon emission accounting. Carbonsphere. 2025;1(9510002). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).