Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

To investigate the combined impacts of temperature and plant residues on the mineralization capacity of soil organic matter and taxonomic composition and activity of the soil microbiome, a 364-day experiment with gray forest soil was carried out in a controlled laboratory conditions. Three substrate management, control (C), augmented with aspen leaves (L) and branches (B), and three temperature settings (2, 12, and 22oC) comprised the treatment levels. According to the findings, long-term experimental warming reduced alpha diversity (number of species), increased microbial respiration and decomposition rates, and changed community composition. It has also lowered active soil organic matter. In comparison to branches, the percentage of mineralization in leaves was higher during the course of the year (29.9-57.8% and 20.1-47.6%, respectively). The efficiency of organic matter decomposition rose by 1.5 to 2 times between 2 and 12°C. It has been discovered that all experimental versions are dominated by Proteobacteria. According to α-diversity analysis, leaves were the most preferred substrate for increasing species representation. Temperature was the most significant factor affecting the microbial community’s structure, according to β-diversity data. Our research provides new insights into the soil organic matter formation, and raises interesting questions regarding the microbiological drivers of this process.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil and Plant Residues Sampling

2.2. Incubation Experiments Design

2.3. Measurement of the Intensity of PR Decomposition and Characteristics of Active Soil Organic Matter Based on Microbial Respiration

2.3. DNA Extraction, Quantitative PCR and Illumina 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.4. 16SrRNA Gene Amplicon Analyses

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

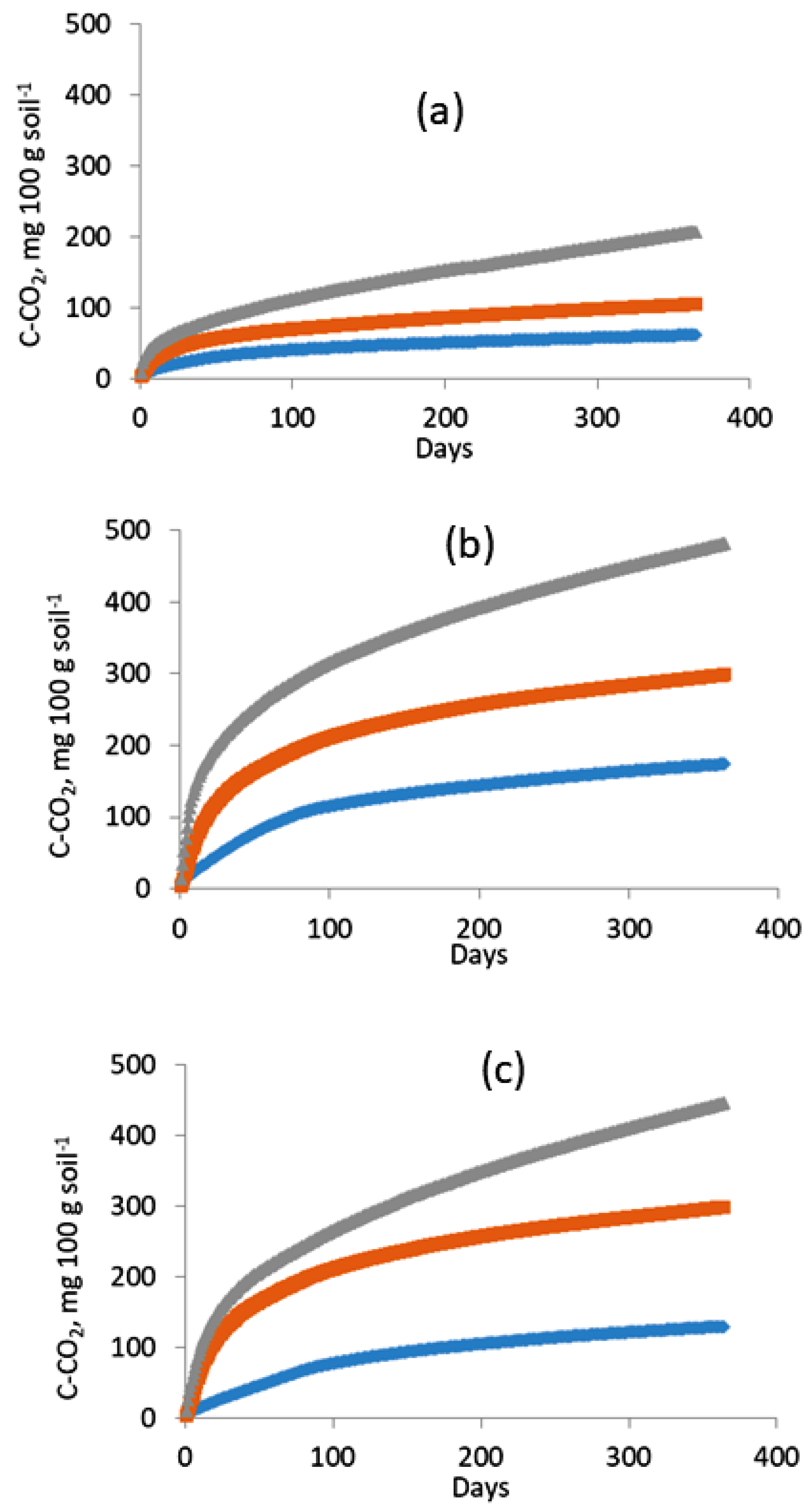

3.1. Dynamics of C-CO2 Release from Soil Samples

3.2. Decomposition of Plant Residues and Formation of the Active SOM Pool

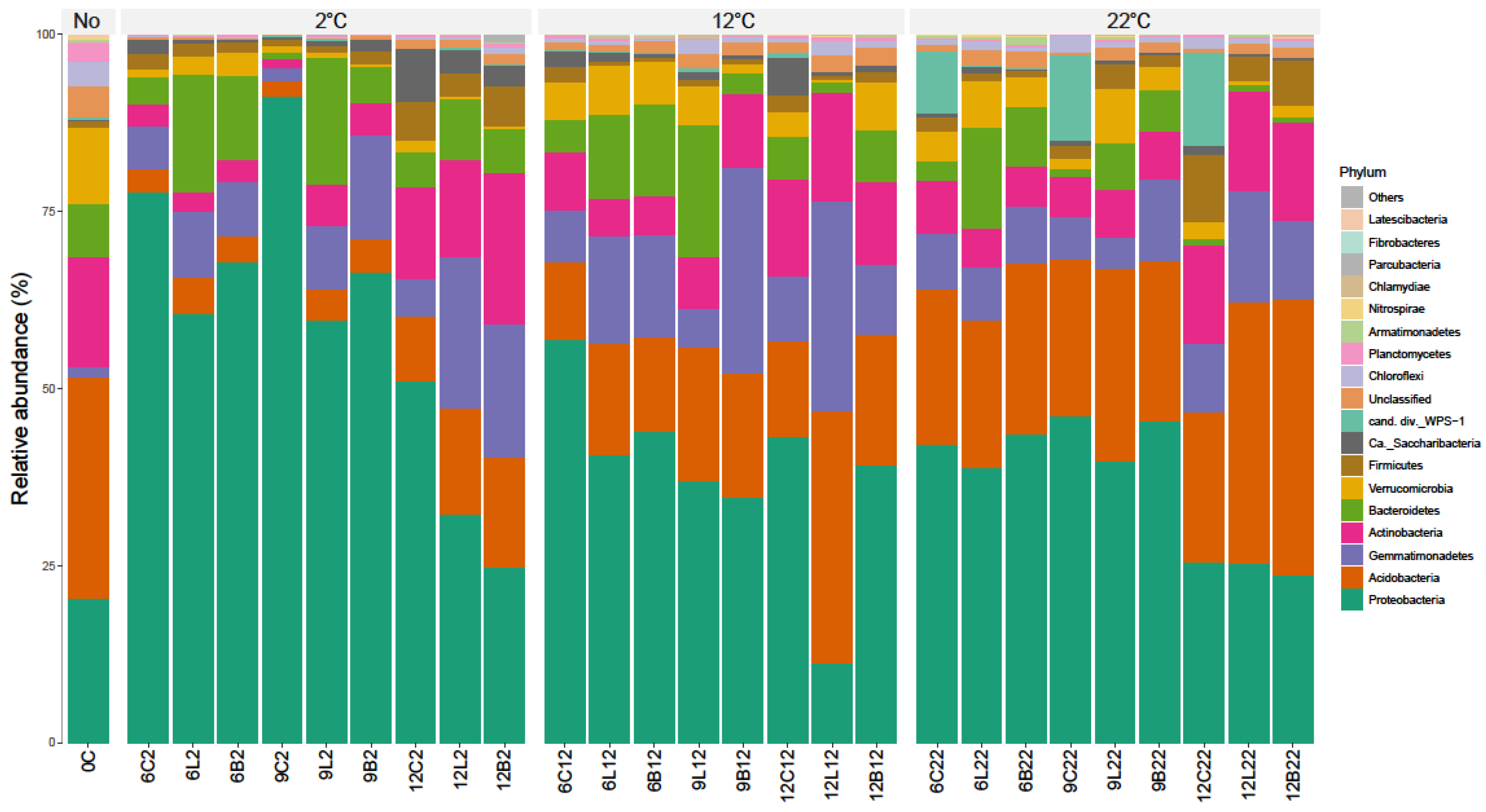

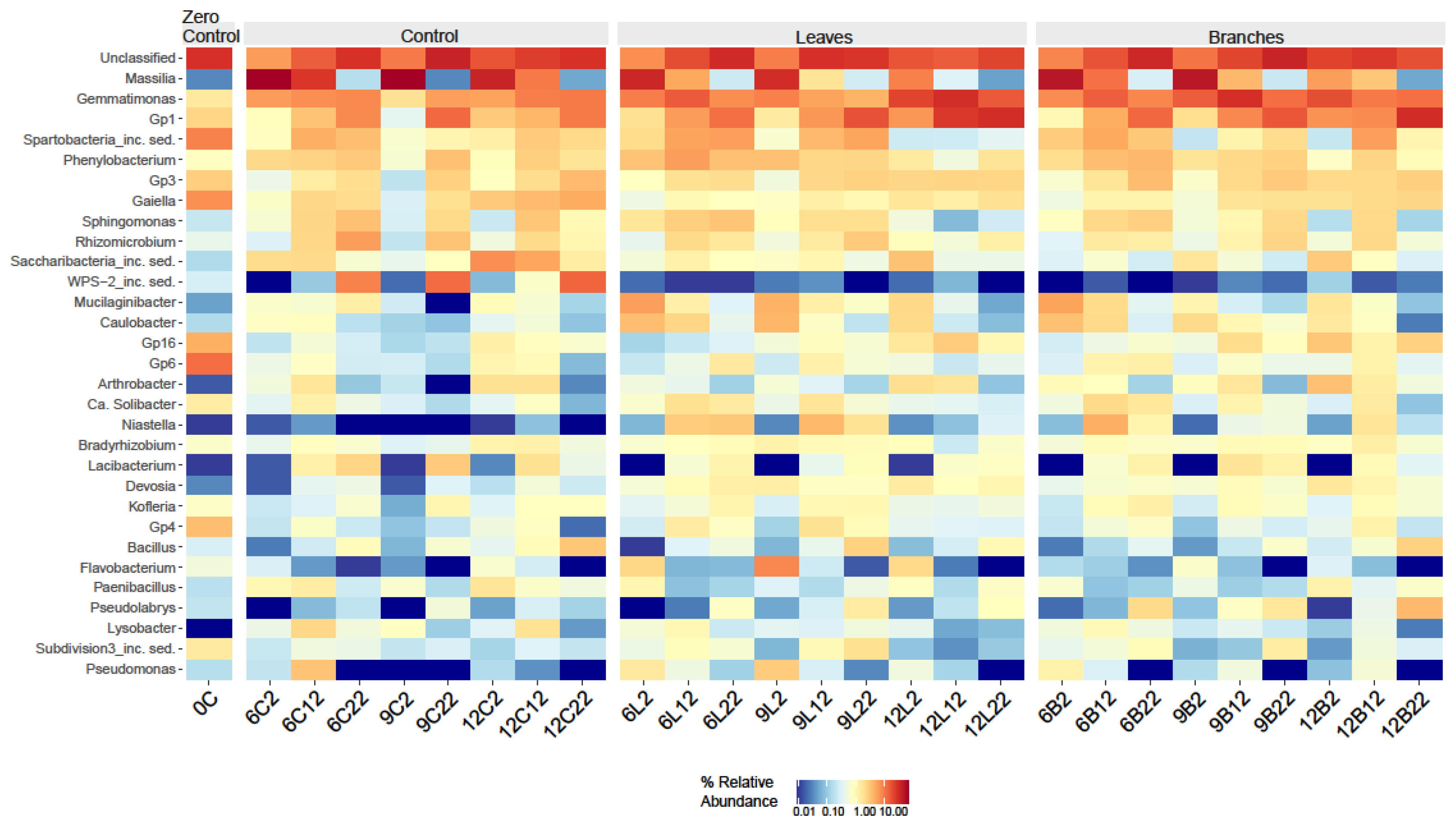

3.3. Effect of Plant Residues on the Soil Bacterial Communities over Time at Different Incubation Temperatures

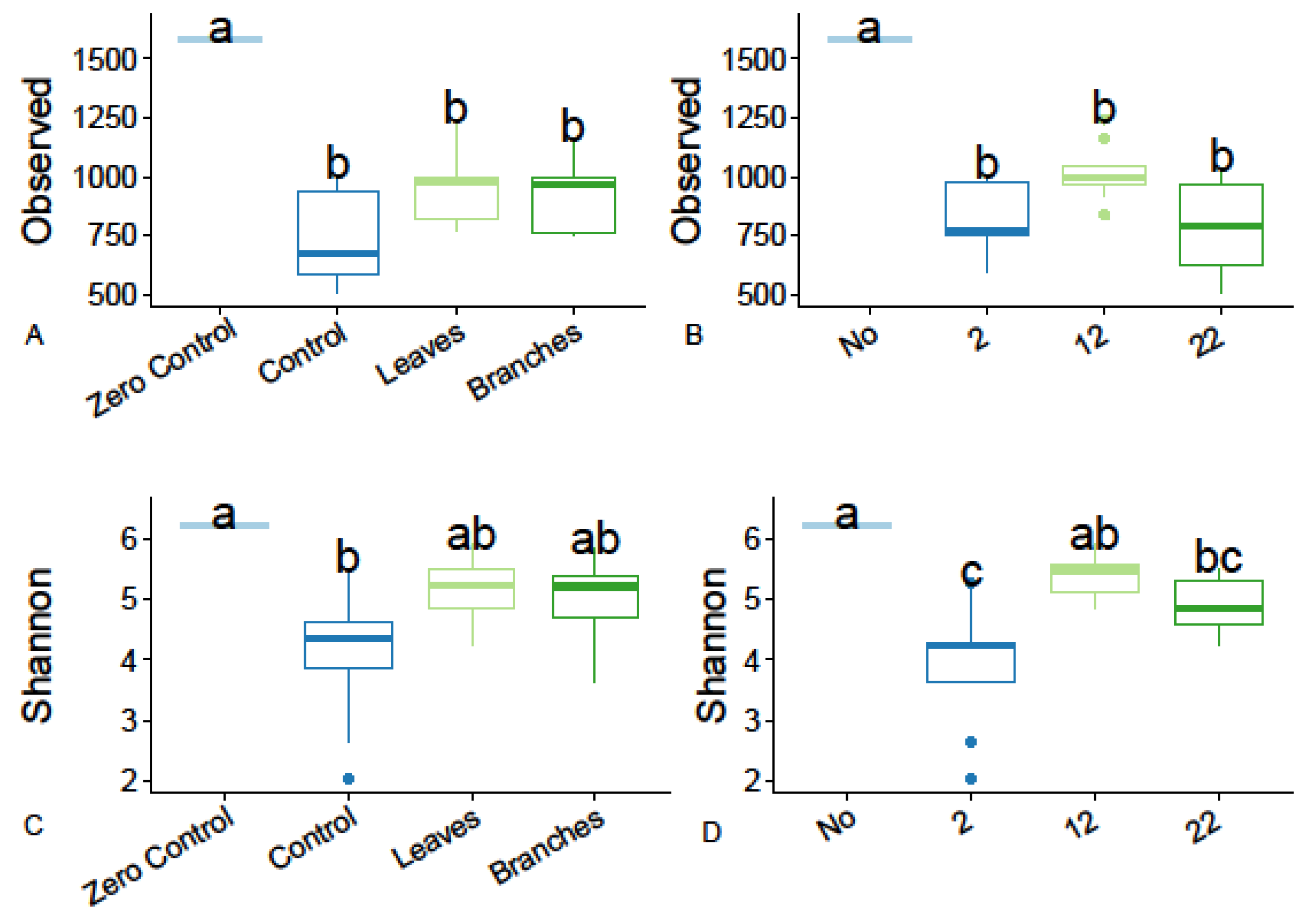

3.4. Diversity of Soil Bacterial Communities

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Temperature on Soil Organic Matter During Decomposition of Forest Litter

4.2. Effect of Temperature on Microbial Communities During Forest Litter Decomposition

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kögel-Knaber, I.; Amelung, W. Dynamics, Chemistry, and Preservation of Organic Matter in Soils. In Treatise on Geochemistry, Second Edition; Holland, H.D. , Turekian, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2014; Volume 12, pp. 157–215. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, R.B.; Lajtha, K.; Crow, S.E.; Hugelius, G.; Kramer, M.G.; Piñeiro, G. The ecology of soil carbon: pools, vulnerabilities, and biotic and abiotic controls. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017, 48, 419–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 2015, 528, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krull, E.S.; Skjemstad, J.O.; Baldock, J.A. Functions of soil organic matter and the effect on soil properties. CSIRO 2004, 129 p.

- Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Follstad Shah, J.J. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry of recalcitrant organic matter decomposition: the growth rate hypothesis in reverse. Biogeochemistry 2011, 102, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Ryo, M.; Lehmann, A.; Aguilar-Trigueros, C.A.; Buchert, S.; Wulf, A.; Iwasaki, A.; Roy, J.; Yang, G. The role of multiple global change factors in driving soil functions and microbial biodiversity. Science 2019, 366, 886–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleber, M.; Bourg, I.C.; Coward, E.K.; Hansel, C.M.; Myneni, S.C.; Nunan, N. Dynamic interactions at the mineral–organic matter interface. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Thompson, A. The influence of native soil organic matter and minerals on ferrous iron oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2021, 292, 254–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.A.; Maynard, D.S.; Crowther, T.W.; Frankson, P.T.; Mohan, J.E.; Steinrueck, C.; Warren, R.J. Belowground community turnover accelerates the decomposition of standing dead wood. Ecology 2021, 102, e03484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santonja, M.; Pereira, S.; Gauquelin, T.; Quer, E.; Simioni, G.; Limousin, J.M.; Baldy, V. Experimental precipitation reduction slows down litter decomposition but exhibits weak to no effect on soil organic carbon and nitrogen stocks in three mediterranean forests of southern France. Forests 2022, 13, 1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, P.E.; Winder, R.S.; Constabel, C.P.; Trofymow, J.A. Fungal community composition as affected by litter chemistry and weather during four years of litter decomposition in rainshadow coastal Douglas-fir forests. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purahong, W.; Ji, L.; Wu, Y.T. Community assembly processes of deadwood mycobiome in a tropical forest revealed by long-read third-generation sequencing. Microb. Ecol. 2024, 87, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.; McClaugherty, C. Plant Litter: Decomposition, Humus Formation, Carbon Sequestration, 3rd ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014; 315p. [Google Scholar]

- Prescott, C.E. Litter decomposition: what controls it and how can we alter it to sequester more carbon in forest soils? Biogeochemistry 2010, 101, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M.J.; Mueller, K.E.; Olk, D.C.; Sawyer, J.E.; Six, J. Integrating plant litter quality, soil organic matter stabilization, and the carbon saturation concept. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3200–3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Soong, J.L.; Horton, A.J.; Campbell, E.E.; Haddix, M.L.; Wall, D.H.; Parton, W.J. Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocci, K.S.; Lavallee, J.M.; Stewart, C.E.; Cotrufo, M.F. Soil organic carbon response to global environmental change depends on its distribution between mineral-associated and particulate organic matter: a meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 793, 148569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocci, K.S.; Cotrufo, M.F.; Ernakovich, J.; Foster, E.; Frey, S.; Georgiou, K.; Grandy, A.S.; Malhotra, A.; Reich, P.B.; Schlerman, E.P.; et al. Bridging 20 years of soil organic matter frameworks: empirical support, model representation, and next steps. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2024, 129, e2023JG007964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Digging deeper: A holistic perspective of factors affecting soil organic carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 3285–3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarascia-Mugnozza, G.; Bauer, G.A.; Persson, H.; Matteucci, G.; Masci, A. Tree biomass, growth and nutrient pools. In Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in European Forest Ecosystems; Schulze, E.D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Didion, M.; Frey, B.; Rogiers, N.; Thürig, E. Validating tree litter decomposition in the Yasso07 carbon model. Ecol. Model. 2014, 291, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoni, S.; Trofymow, J.A.; Jackson, R.B.; Porporato, A. Stoichiometric controls on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus dynamics in decomposing litter. Ecol. Monogr. 2010, 80, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hui, D.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, G. Rates of litter decomposition in terrestrial ecosystems: global patterns and controlling factors. J. Plant Ecol. 2008, 1, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreiro, M.M.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Repert, D.A.; Parkhurst, D.F. Microbial enzyme shifts explain litter decay responses to simulated nitrogen deposition. Ecology 2000, 81, 2359–2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, L.; Głazowska, S.; Mravec, J.; Fangel, J.; Zhang, H.; Felby, C.; Schjoerring, J.K. External nitrogen input affects pre-and post-harvest cell wall composition but not the enzymatic saccharification of wheat straw. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 98, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, S.; He, T.; Liu, L.; Wu, J. Response of organic carbon mineralization and microbial community to leaf litter and nutrient additions in subtropical forest soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 71, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Zhu, B.; Qiang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pang, X. Phosphorus addition decreases plant lignin but increases microbial necromass contribution to soil organic carbon in a subalpine forest. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4194–4210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunel, C.; Garnier, E.; Joffre, R.; Kazakou, E.; Quested, H.; Grigulis, K.; Lavorel, S.; Ansquer, P.; Castro, H.; Cruz, P.; et al. Leaf traits capture the effects of land use changes and climate on litter decomposability of grasslands across Europe. Ecology 2009, 90, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Microbial activity and the dynamics of ecosystem processes in forest soils. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 37, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M.A.; Wieder, W.R.; Bonan, G.B.; Fierer, N.; Raymond, P.A.; Crowther, T.W. Managing uncertainty in soil carbon feedbacks to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menko, E.V.; Tikhonova, E.N.; Ulanova, R.V.; Sukhacheva, M.V.; Kuznetsova, T.V.; Udaltsov, S.N.; Kravchenko, I.K. Temperature sensitivity of the initial stage of microbial destruction of wood litter in forest soil. Biophysics 2018, 63, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, I.; Tikhonova, E.; Semenov, V.M. Temperature sensitivity of litter and soil organic matter decomposition: perspective of soil microbial community structure and function. In Microbes in Land Use Change Management; Singh, J.S., Tiwari, S., Singh, C., Singh, A.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Filley, T.R.; Boutton, T.W.; Liao, J.D.; Jastrow, J.D.; Gamblin, D.E. Chemical changes to nonaggregated particulate soil organic matter following grassland-to-woodland transition in a subtropical savanna. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2008, 113, G03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A.; Janssens, I.A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 2006, 440, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, M.U.F. The temperature dependence of organic-matter decomposition—still a topic of debate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2510–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, I.P.; Ineson, P. Substrate quality and the temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1567–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melillo, J.M.; Frey, S.D.; DeAngelis, K.M.; Werner, W.J.; Bernard, M.J.; Bowles, F.P.; Grandy, A.S. Long-term pattern and magnitude of soil carbon feedback to the climate system in a warming world. Science 2017, 358, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gestel, N.; Shi, Z.; Van Groenigen, K.J.; Osenberg, C.W.; Andresen, L.C.; Dukes, J.S.; Hungate, B.A. Predicting soil carbon loss with warming. Nature 2018, 554, E4–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenov, V.M.; Lebedeva, T.N.; Zinyakova, N.B.; Khromychkina, D.P.; Sokolov, D.A.; Lopes de Gerenyu, V.O.; Kravchenko, I.K.; Li, H.; Semenov, M.V. Dependence of soil organic matter and plant residues decomposition on temperature and moisture in the long-term incubation experiments. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2022, 55, 926–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, J.C.; Tang, J.; Templer, P.H.; Kroeger, K.D.; Crowther, T.W.; Burton, A.J.; Tietema, A. Temperature response of soil respiration largely unaltered with experimental warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 13797–13802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, T.W.; Todd-Brown, K.E.O.; Rowe, C.W.; Wieder, W.R.; Carey, J.C.; Machmuller, M.B.; Bradford, M.A. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 2016, 540, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks Pries, C.E.; Castanha, C.; Porras, R.C.; Torn, M.S. The whole-soil carbon flux in response to warming. Science 2017, 355, 1420–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, J.G.; Huggins, D.R.; Reganold, J.P. Climate change predicted to negatively influence surface soil organic matter of dryland cropping systems in the inland Pacific Northwest, USA. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Craine, J.M.; McLauchlan, K.; Schimel, J.P. Litter quality and the temperature sensitivity of decomposition. Ecology 2005, 86, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzner, E.; Borken, W. Do freeze-thaw events enhance C and N losses from soils of different ecosystems? A review. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2008, 59, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Peng, F.; Sun, H.; Xue, X.; Chu, H. Divergent responses of soil fungi functional groups to short-term warming. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 68, 708–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Freeman, C.; Ostle, N.J. Microbial contributions to climate change through carbon cycle feedbacks. ISME J. 2008, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Schimel, J.P.; Jastrow, J.D. The importance of anabolism in microbial control over soil carbon storage. Nat. Microbiol. 2017, 2, 17105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason-Jones, K.; Tian, P.; Liu, S.; Wang, Q.; Sun, T. Form of nitrogen deposition affects soil organic matter priming by glucose and cellulose. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2019, 55, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Jackson, R.D.; DeLucia, E.H.; Tiedje, J.M.; Liang, C. The soil microbial carbon pump: From conceptual insights to empirical assessments. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 6032–6039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästner, M.; Miltner, A.; Thiele-Bruhn, S.; Liang, C. Microbial necromass in soils—linking microbes to soil processes and carbon turnover. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 756378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yergeau, E.; Bokhorst, S.; Kang, S.; Zhou, J.; Greer, C.W.; Aerts, R.; Kowalchuk, G.A. Shifts in soil microorganisms in response to warming are consistent across a range of Antarctic environments. ISME J. 2012, 6, 692–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Xue, K.; Xie, J.; Deng, Y.; Wu, L.; Cheng, X.; Luo, Y. Microbial mediation of carbon-cycle feedbacks to climate warming. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D.; Wallenstein, M.D.; Bradford, M.A. Soil-carbon response to warming dependent on microbial physiology. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinnan, R.; Rousk, J.; Yergeau, E.; Kowalchuk, G.A.; Bååth, E. Temperature adaptation of soil bacterial communities along an Antarctic climate gradient: predicting responses to climate warming. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 2615–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blagodatskaya, E.; Blagodatsky, S.; Khomyakov, N.; Myachina, O.; Kuzyakov, Y. Temperature sensitivity and enzymatic mechanisms of soil organic matter decomposition along an altitudinal gradient on Mount Kilimanjaro. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, B.; Liu, L.; Yang, G.; Fang, K.; Yang, Y. Linking temperature sensitivity of soil CO2 release to substrate, environmental, and microbial properties across alpine ecosystems. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2016, 30, 1310–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karhu, K.; Auffret, M.D.; Dungait, J.A.J.; Hopkins, D.W.; Prosser, J.I.; Singh, B.K.; Hartley, I.P. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration rates enhanced by microbial community response. Nature 2014, 513, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, S.; Gleixner, G.; Wutzler, T.; Reichstein, M. Both priming and temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition depend on microbial biomass–An incubation study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013, 57, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, V.M.; Pautova, N.B.; Lebedeva, T.N.; Khromychkina, D.P.; Semenova, N.A. Decomposition of plant residues and the formation of active organic matter in the soil of incubation experiments. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larionova, A.A.; Kvitkina, A.K.; Evdokimov, I.V.; Bykhovets, S.S.; Stulin, A.F. Effect of temperature on the decomposition rate of labile and stable organic matter in agrochernozem. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2013, 46, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, V.M.; Tulina, A.S. Comparative characteristics of the mineralizable pool of organic matter in soils of natural and agricultural ecosystems. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2011, 44, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glöckner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M.V.; Manucharova, N.A.; Krasnov, G.S.; Nikitin, D.A.; Stepanov, A.L. Biomass and taxonomic structure of microbial communities in soils of the right-bank basin of the Oka River. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 971–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. phyloseq: An R Package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glöckner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Kuczynski, J.; Stombaugh, J.; Bittinger, K.; Bushman, F.D.; Costello, E.K.; Fierer, N.; Peña, A.G.; Goodrich, J.K.; Gordon, J.I.; et al. QIIME allows analysis of highthroughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 335–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Averick, M.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; D’Agostino McGowan, L.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; et al. Welcome to the Tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksanen, J.; Blanchet, F.G.; Friendly, M.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; McGlinn, D.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Simpson, G.L.; Solymos, P.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5-6. 2019. Community Ecol. 2020, 8, 732–740. [Google Scholar]

- Angst, G.; Mueller, K.E.; Nierop, K.G.J.; Simpson, M.J. 2021. Plant- or microbial- derived? A review on the molecular composition of stabilized soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 156, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, B.A.; Fritschi, F.B.; Horwath, W.R.; Scow, K.M.; Rains, W.D.; Travis, R.L. Comparisons of soil microbial communities influenced by soil texture, nitrogen fertility, and rotations. Soil Sci. 2011, 176, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Hu, X.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, T.; Zhang, F.; Ji, C.; Zhu, J. The decomposition rates of leaf litter and fine root and their temperature sensitivities are influenced differently by biotic factors. Plant Soil 2021, 461, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conant, R.T.; Drijber, R.A.; Haddix, M.L.; Parton, W.J.; Paul, E.A.; Plante, A.F.; Steinweg, J.M. Sensitivity of organic matter decomposition to warming varies with its quality. Glob. Change Biol. 2008, 14, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Castellano, M.J.; Ye, C.; Zhang, N.; Ding, W. Oxygen availability regulates the quality of soil dissolved organic matter by mediating microbial metabolism and iron oxidation. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 7410–7427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershenson, A.; Bader, N.E.; Cheng, W. Effects of substrate availability on the temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition. Glob. Change Biol. 2009, 15, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Godbold, D.L.; Sun, H.; Wei, L.; Zhang, Y. Temperature sensitivity of organic matter mineralization as affected by soil edaphic properties and substrate quality. Catena 2022, 210, 105901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, F.; Bouziri, L.; Nicolardot, B.; Ranjard, L. Impact of wheat straw decomposition on successional patterns of soil microbial community structure. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkama-Rajala, T.; Müller, M.M.; Pennanen, T. Decomposition and fungi of needle litter from slow-and fast-growing Norway spruce (Picea abies) clones. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 56, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Friedel, J.K.; Stahr, K. Review of mechanisms and quantification of priming effects. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2000, 32, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Griffiths, B.S.; Langenheder, S. Microbial community resilience across ecosystems and multiple disturbances. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2021, 85, e00026–e00120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Terhonen, E.; Koskinen, K.; Paulin, L.; Kasanen, R.; Asiegbu, F.O. Bacterial diversity and community structure along different peat soils in boreal forest. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2014, 74, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Chen, L.; Qin, S.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, X.; Chen, P.; Yang, Y. Mineral and climatic controls over soil organic matter stability across the Tibetan alpine permafrost region. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2021, 35, e2021GB007118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.X.; Bi, Q.F.; Hao, X.L.; Zhou, G.W.; Yang, X.R. Massilia phosphatilytica sp. nov., a phosphate solubilizing bacteria isolated from a long-term fertilized soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 2514–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenov, M.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Semenov, V.M.; van Bruggen, A.H.C. Long-term fertilization rather than plant species shapes rhizosphere and bulk soil prokaryotic communities in agroecosystems. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 154, 103641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Q.; An, S.; Liu, Y. Soil bacterial community response to vegetation succession after fencing in the grassland of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 609, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Yang, S.; Wang, G. Niastella vici sp. nov., isolated from farmland soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prevost-Boure, N.C.; Maron, P.A.; Ranjard, L.; Nowak, V.; Dufrene, E.; Damesin, C.; Lata, J.C. Seasonal dynamics of the bacterial community in forest soils under different quantities of leaf litter. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2011, 47, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, S.; Park, J.H.; Rahman, M.M.; Huq, M.A. Niastella soli sp. nov., isolated from rhizospheric soil of a persimmon tree. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71, 004870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Soil’s parameter, dimension | Parameter`s value |

| Texture | Loamya, coarseb |

| Clay, % | 37.6 ± 0.7 |

| Sand, % | 1.8 ± 0.5 |

| Loam, % | 14.8 ± 0.5 |

| pHH2O | 5.28 ± 0.02 |

| SOC, % TN,% |

2.53 ± 0.04 0.15 ± 0.03 |

| C:N | 12.13 |

| N-NH4+, mg/100 g | 0.29 ± 0.04 |

| N-NO3˗, mg/100g | 0.27 ± 0.01 |

| P2O5, mg/100g | 4.62 ± 0.09 |

| K2O, mg/100g | 14.10 ± 0.01 |

| Ca2+, mmol/100 g | 22.4 ± 0.14 |

| Mg2+, mmol/100 g | 0.60 ± 0.01 |

| Cmbc, mg/100g | 158 ± 3 |

| Nmbd, mg/100g | 38 ± 121 |

| Temperature | Variant | Corg, % of initial | k1, day-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2°С | Control | 2.6 ± 0.1 | 0.019 ± 0.000 |

| Leaves | 29.9 ± 0.1 | 0.013 ± 0.000 | |

| Branches | 20.1 ± 0.2 | 0.006 ± 0.000 | |

| 12°С | Control | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 0.021 ± 0.000 |

| Leaves | 44.7 ± 1.1 | 0.017 ± 0.001 | |

| Branches | 32.1 ± 0.4 | 0.014 ± 0.000 | |

| 22°С | Control | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 0.011 ± 0.000 |

| Leaves | 57.8 ± 1.7 | 0.025 ± 0.001 | |

| Branches | 47.6 ± 0.6 | 0.015 ± 0.001 |

| Temperature | Variant | C0, mg/100 g | k1, day-1 | % of initial Сorg content | MRI, mg C/100 g/ day |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2°С | Control (C2) | 64.8 ± 1.1 | 0.019 ± 0.000 | 2.6 | 1.24 |

| Leaves (L2) | 192.8 ± 0.8 | 0.015 ± 0.000 | 6.5 | 2.89 | |

| Branches (B2) | 149.6 ± 1.5 | 0.010 ± 0.000 | 5.0 | 1.56 | |

| 12°С | Control (C12) | 94.1 ± 1.8 | 0.021 ± 0.000 | 3.7 | 1.94 |

| Leaves (L12) | 286.0 ± 3.0 | 0.018 ± 0.000 | 9.7 | 5.11 | |

| Branches (B12) | 244.1 ± 0.2 | 0.016 ± 0.000 | 8.2 | 3.90 | |

| 22°С | Control (C22) | 186.1 ± 2.7 | 0.011 ± 0.000 | 7.4 | 2.13 |

| Leaves (L22) | 423.5 ± 5.8 | 0.019 ± 0.000 | 14.3 | 7.86 | |

| Branches (B22) | 405.3 ± 1.6 | 0.014 ± 0.001 | 13.5 | 5.47 |

| Temperature range | Variants | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Leaves | Branches | |

| Based on decomposition rate efficiency | |||

| 2–12 °С | 1.42 | 1.49 | 1.60 |

| 12–22 °С | 2.00 | 1.29 | 1.48 |

| Based on C-CO2 production during first month of decomposition | |||

| 2–12 °С | 1.87 | 3.12 | 10.31 |

| 12–22 °С | 1.72 | 1.38 | 1.89 |

| Based on C-CO2 production during 10th month of decomposition | |||

| 2–12 °С | 1.48 | 1.71 | 1.94 |

| 12–22 °С | 3.17 | 2.21 | 2.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).