1. Introduction

Over the past decade, society’s growing interest in consuming fresh, functional and healthy foods has led to a notable increase in the popularity of microgreens. These are young, tender edible seedlings that are harvested when the cotyledonous leaves have fully developed and the first leaves emerge [

1]. This category of vegetables is distinguished from common sprouts and tender leafy vegetables by their higher content of vitamins, minerals and bioactive compounds, such as ascorbic acid and carotenoids [

2].

Microgreens are produced from a variety of crops including herbs, cereals and vegetables, with a development cycle ranging from 7 to 21 days after germination, reaching heights of between 4 and 8 cm [

3]. In addition to attracting health-conscious consumers, chefs have also incorporated them into their dishes, taking advantage of their sensory attributes such as aroma, texture and flavour. Their use ranges from soups and salads to sandwiches [

4]. They have even been studied as potential food supplements to support life in space environments [

5].

Furthermore, microgreens are particularly valued within the vegan community as they offer an important source of nutrients, including macro and microelements, minerals [

6]. The most common botanical families for its cultivation include

Brassicaceae, Chenopodiaceae , Apiaceae , Amaranthaceae , Fabaceae , Lamiaceae and

Poaceae , an interesting aspect is that the

Brassicaceae family is the most popular [

7]. In particular, broccoli microgreens (

Brassica oleracea var.

italica) have been the target of several studies due to the nutritional content and bioactive compounds, broccoli contains higher total glucosinolates in sprouts (162.19 µ mol g

−1) [

8]. And have the ability to

reduce the incidence of cancer such as colon cancer. Other Brassica species

studied include cabbage

(Brassica oleracea var. sabellica) containing bioactives such as glucosinolates, flavonoids, phenols, and anthocyanins, this popular food also has therapeutic uses in traditional medicine to improve various respiratory, gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular diseases [

9]. Whereas beetroot

(Beta vulgaris) is among the most popular varieties of microgreens not only because of its nutrient-rich properties, containing betalains and polyphenols, but also its intense aromatic flavor [

10]. Moreover, it contains fiber, vitamins A and C, and essential minerals such as iron and magnesium, which support cardiovascular health and immune function [

11].

Microgreens from red amaranth

(Amaranthaceae) cruentus L

) stand out for their vibrant purple color and distinctive, slightly nutty flavor. This superfood is rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals, making it a nutritious and attractive option for salads and decorative dishes [

12]. On the other hand, due to the presence of various phytonutrients contained in microgreens, they are considered the next generation of “superfoods” or “functional foods” [

2]. Microgreens do not require much space for cultivation as they are produced in small spaces, however, their production and use are limited by their short shelf life, one of the major challenges in the microgreens industry [

13]. As fresh-cut products, microgreens are characterized by a relatively short shelf life, not exceeding 10–14 days [

14]. Being composed of young tissues, fresh-cut microgreens are highly perishable whose decline is more related to a stress-induced response following natural senescence [

15].

It is necessary to mention that pre-harvest, post-harvest treatments, packaging materials and modified atmosphere packaging have been considered as variables that affect the shelf life of fresh cut microgreens [

16]. Like storage conditions, which include temperature, humidity, can accelerate quality loss and limit shelf life [

17]. However, storage at a temperature between 0 and 5 °C reduces the respiration and aging rate, as well as the growth of microorganisms that cause deterioration, significantly reducing quality loss and even extending shelf life [

16]. It is necessary to mention that the shelf life at room temperature is between 3 to 5 days [

18].

Factors such as lighting, packaging method, and chlorine washing have been shown to impact the phytochemical profile of microgreens [

19]. Other research reports that using chlorine washing results in an improvement in appearance and microbial quality [

20]. Based on the above, the research aimed to evaluate the proximal composition

and nutritional potential of microgreens (

Brassica oleracea, Brassica oleracea var. capitata, Beta vulgaris, Amaranthus) depending on the days of storage.

2. Materials and Methods

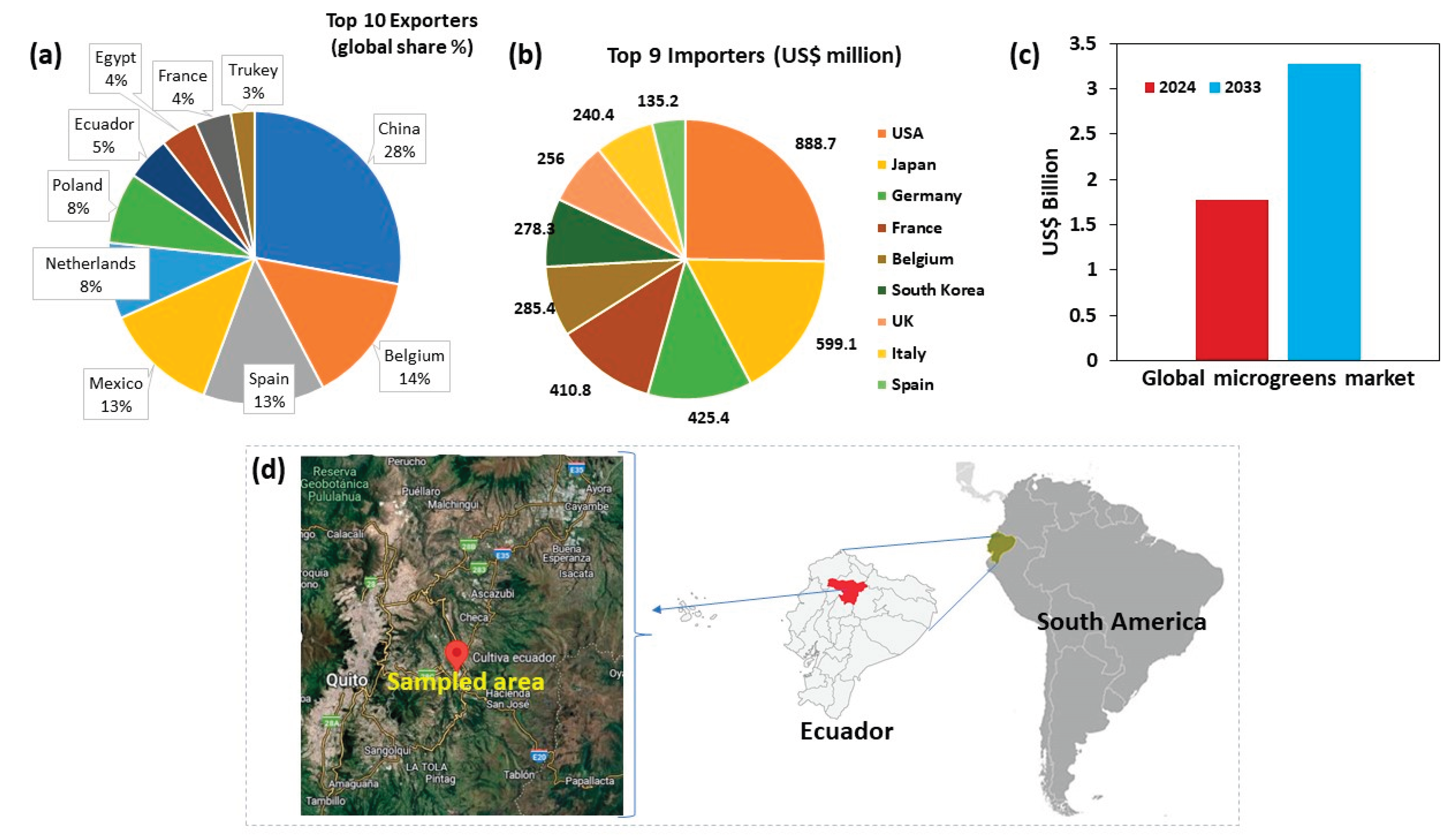

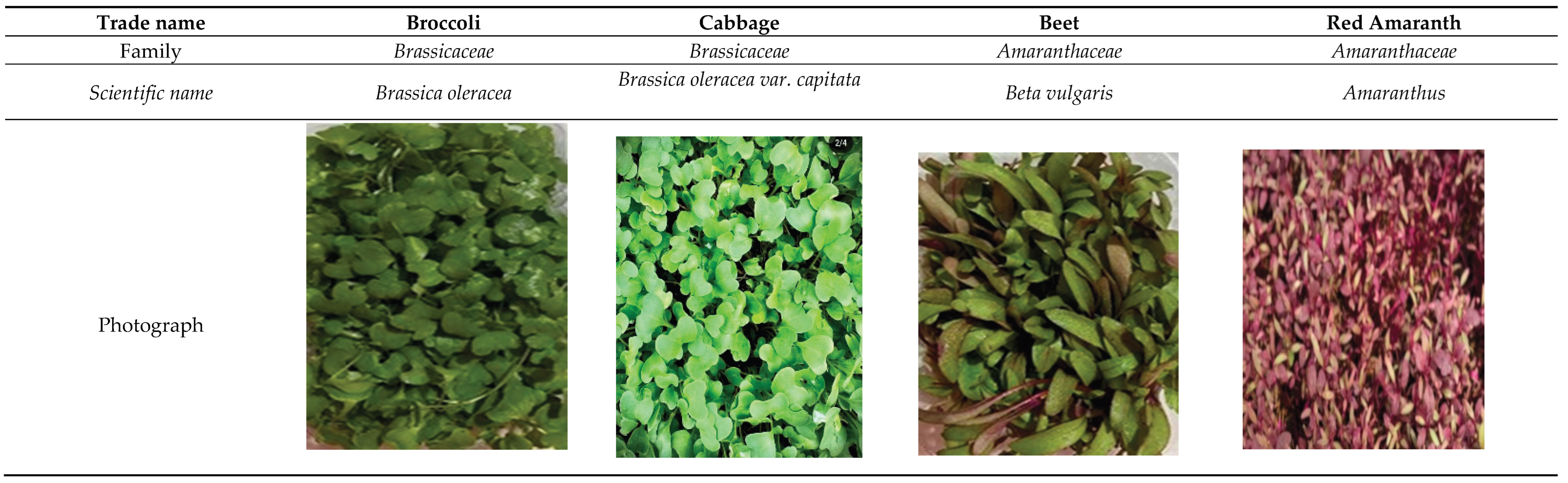

2.1. Plant Material

Four varieties of microgreens (broccoli, cabbage, beetroot and red amaranth) were selected based on the commercial demand of the chosen producer. The plant material was obtained from the farm “Cultiva Farm Ecuador”, located in Puembo, Pichincha, Ecuador (

Figure 1). The details of this selection are presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Proximal Composition

For the study, microgreen varieties were selected and harvested, using 25 boxes of each type. Three samples of each variety were taken at random and divided into two parts. The first part was immediately analyzed to assess dry matter, chlorophylls, antioxidant capacity and anthocyanins. The second part was subjected to deep freezing at -40 °C for metal analysis.

To determine the proximate composition of the samples, the following analyses were carried out: moisture content was measured on a fresh weight (FW) basis using AOAC method 964.22. Protein content was calculated using the Kjeldahl nitrogen method (N × 6.25) according to AOAC protocol 955.04. Lipid extraction was performed using the Soxhlet method according to AOAC 920.39C. Total dietary fiber was determined using an enzymatic-gravimetric procedure following AOAC method 991.43. Ash content was measured using a muffle furnace according to AOAC method 923.03. Finally, total carbohydrates were calculated by difference.

2.3. Content of Mineral Macroelements and Microelements

The analysis of mineral macro and microelements was carried out in the certified laboratory “Multianalityca”. The samples were prepared according to the AOAC 2015.06 reference method and were ultra-frozen to preserve their properties. Subsequently, analyses of mineral macroelements (Ca, K, Na , Mg, P) and microelements, also known as trace elements (As, B, Co, Cu, Fe, Mn, Mo, Zn, Ag, Al, Ba, Be, Cd, Cr, Hg, Li, Ni, Pb, Sb, Se, Sn, Sr, Ti, Tl, V) were carried out using the ICP-MS technique, according to the AOAC 2019 protocol. To characterize the mineral elements, present in the microgreens, the analysis was carried out on the seventh day of storage, which represents the average consumption time.

2.4. Analysis of Chlorophyll a and b, ß—Carotene and Anthocyanins of Microgreens

Chlorophyll a and b, beta carotene and anthocyanins were evaluated on the fifth day of storage to characterize the microgreens, since there is currently no established profile for these components. To perform these analyses, 1 g of fresh weight (FW) of the samples was processed, which was homogenized with a mixture of acetone and hexane in a 2:3 ratio for 2 minutes, until a homogeneous mixture was obtained. Subsequently, they were centrifuged using an Eppendorf 5810 R centrifuge, and the results were obtained using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer, following the equations described by Samuoliene et al. [

23]. In addition, the antioxidant power of the samples was analyzed using the FRAP method, as established by Sanpimit et al. [

24]. The results were expressed in milligrams of ascorbic acid equivalent per gram of extracts (mg EAA/g)

2.5. Experimental Design

An A*B factor analysis was used with a significance level according to Tukey’s multiple range test (p≤ 0.05) using InfoStat statistical software. Data were expressed as mean with standard deviation (+/–). Repeated measures ANOVA (p≤0.05) was used to determine statistical significance between microgreens varieties (Factor A) and storage days (Factor B) (

Table 2).

3. Results

3.1. Proximal Composition of the Studied Microgreens

Table 3 presents the proximate composition of the evaluated microgreens, considering both the microgreen varieties (Factor A) and storage time (Days 0, 5, and 10). Statistical analysis revealed significant differences (p < 0.05) among varieties and across storage periods. Moisture content increased progressively during storage, with cabbage microgreens exhibiting the highest value (95.65%) on Day 10, while beetroot showed the lowest (94.20%) on Day 5. Protein content declined over time, with cabbage recording the highest initial level (4.79% on Day 0) and red amaranth the lowest on Day 10 (2.01%). Lipid content varied among species and storage days; amaranth microgreens had the highest lipid level (0.85%) on Day 1, whereas cabbage presented the lowest (0.25%) on Day 10. Dietary fiber content was highest in cabbage and beet microgreens on Day 1 (1.19–1.22%), while broccoli (0.69%) and red amaranth (0.72%) experienced a decrease by Day 10. Ash content, reflecting total mineral presence, also varied significantly across varieties and storage times, with beet microgreens reaching the highest value (1.85%) and cabbage the lowest (0.81%) on Day 10.

3.2. Analysis of Chlorophyll a and b, ß—Carotene and Anthocyanins of Microgreens as a Function of Storage Days

Table 4 summarizes the concentrations of chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, β-carotene, and anthocyanins in the analyzed microgreens. Storage time (Factor B) had a significant effect (p < 0.05) on all evaluated compounds, indicating that these bioactive pigments are highly sensitive to degradation during storage. At the start of the study (Day 0), broccoli microgreens exhibited the highest chlorophyll a concentration (2.50 mg/g FW), whereas beetroot showed the lowest value (1.48 mg/g FW) by Day 10. For chlorophyll b, cabbage (Brassicaceae) had the highest content (6.35 mg/g FW), while red amaranth (Amaranthaceae) had the lowest (2.49 mg/g FW). β-Carotene levels were generally lower than chlorophylls, with beetroot recording the highest concentration (0.91 µg/g FW) and red amaranth the lowest (0.20 µg/g FW). Anthocyanin content varied significantly among species, with beetroot showing the highest value (29.40 µmol/100 g FW), followed by red amaranth (19.01 µmol/100 g FW), and cabbage the lowest (3.80 µmol/100 g FW). These results confirm that both the concentration and stability of pigments are strongly influenced by microgreen species and storage duration.

3.3. Analysis of Mineral Macro and Microelements of the Varieties Studied on Day 5

The analyzed microgreens exhibited a diverse and nutritionally significant mineral composition, with high levels of essential macro- and micronutrients (

Table 5). Among the macronutrients, potassium, calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium were predominant across the studied varieties. Notably, cabbage microgreens showed the highest potassium content (5600.0 mg/kg), whereas broccoli contained the greatest concentrations of calcium (880.0 mg/kg), phosphorus (520.0 mg/kg), and magnesium (290.0 mg/kg). Regarding micronutrients, beetroot microgreens stood out for their elevated iron and zinc levels, reaching 12.0 mg/kg and 4.6 mg/kg, respectively. All evaluated species—including broccoli, beetroot, red amaranth, purple cabbage, and pea microgreens—demonstrated a dense mineral profile encompassing copper, selenium, phosphorus, iron, zinc, molybdenum, and chromium. These findings highlight the superior mineral density of microgreens compared to mature vegetables, supporting their potential role as functional foods capable of enhancing dietary micronutrient intake and contributing to overall nutritional quality.

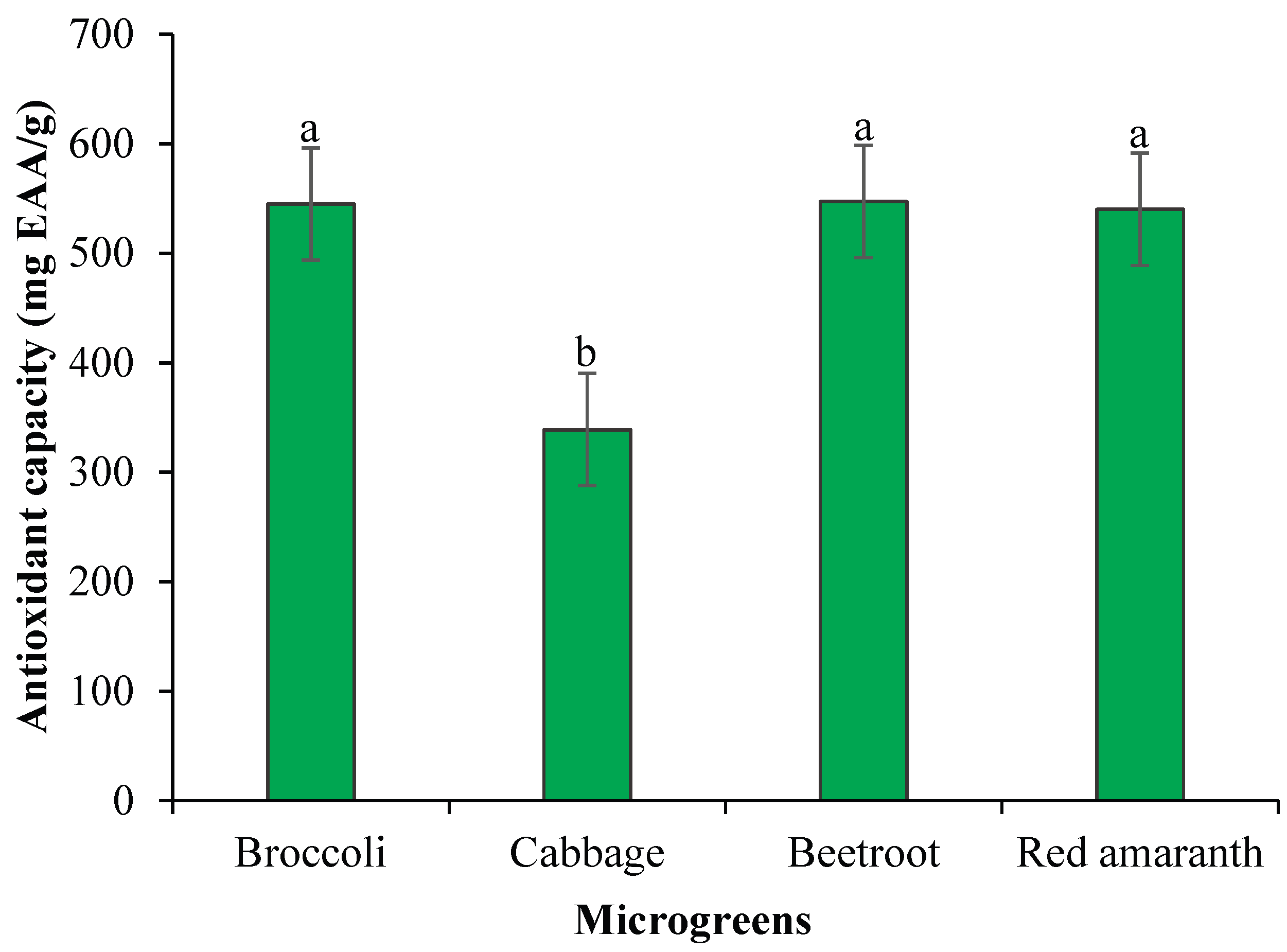

3.4. Antioxidant Capacity of Microgreens

Figure 2 illustrates notable differences in the antioxidant capacity among the analyzed microgreens. Beet (Beta vulgaris) and broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. italica) microgreens exhibited the highest antioxidant capacities, reaching 547 mg EAA/g and 545 mg EAA/g, respectively. In contrast, cabbage microgreens displayed the lowest value, with 339 mg EAA/g. Additionally, the antioxidant capacity of microgreens, expressed as µM Trolox equivalents per 100 g, was generally lower than that reported for their mature counterparts. Among the species evaluated, broccoli and beetroot consistently showed relatively higher antioxidant activity, highlighting their potential as functional foods for enhancing dietary antioxidant intake.

4. Discussion

4.1. Proximal Composition of the Studied Microgreens

The progressive increase in moisture content observed during storage may be attributed to condensation and the absorption of ambient humidity within the storage environment. This trend is consistent with the findings of Kowitcharoen et al. [

25], who reported moisture levels of 94.07% in broccoli and 93.63% in cabbage microgreens, as well as values ranging from 80.83% to 92.63% in carrot, spinach, watercress, and Bengal gram microgreens. Elevated moisture levels are directly associated with a reduced shelf life due to the higher susceptibility to microbial growth, underscoring the need for controlled storage conditions to maintain quality and safety [

26].

The observed decline in protein content during storage can be explained by enzymatic and microbial activity that progressively degrades proteins over time. Similar patterns have been reported in microgreens of Cichorium intybus L. and Brassica oleracea L., where protein content decreased to 1.9–2.08% after 10 days of storage [

27]. These results confirm that members of the Brassicaceae family generally maintain higher protein concentrations than species from other botanical families, such as Linaceae [

28], likely due to differences in intrinsic amino acid composition and nitrogen metabolism.

Overall, these findings suggest that both moisture accumulation and protein degradation are critical factors affecting microgreen quality during storage. Maintaining optimal storage conditions is therefore essential to preserve their nutritional and functional properties. Future research should focus on strategies to extend shelf life, including modified atmosphere packaging, humidity control, and exploration of cultivar-specific responses to storage. Regarding lipid content, the low and stable values during storage confirm that microgreens have a lipid profile similar to that of mature plants. Comparable lipid levels have also been reported in broccoli (0.49%), purple radish (0.495%), cabbage (0.36%), lentils (0.43%), beans (0.36%), and peas (0.15%) [

25,

27]. These low lipid values reinforce the classification of microgreens as low-fat, nutrient-dense foods suitable for healthy diets.

The observed decline in dietary fiber in broccoli and red amaranth microgreens toward Day 10 is consistent with enzymatic degradation processes and moisture variations that affect structural carbohydrates [

29]. Fiber content in spinach (

Spinacia oleracea) and hibiscus (

Hibiscus sabdariffa) ranges between 1.00–1.50% [

30], supporting the results obtained in this study. The minor fluctuations observed confirm that storage conditions significantly influence fiber integrity in microgreens.

Lastly, the variation in ash content indicates changes in the mineral profile over storage time. The highest value in beet microgreens (1.85%) suggests higher mineral accumulation compared to cabbage (0.81%). Similar studies on the characterization of microgreens documented ash values of 1.10% in lettuce

(Lactuca sativa) and 1.20% in wild cabbage

(Brassica oleracea L.) [

27]. It is emphasized that these were attributed to environmental factors, growth media, and species-specific physiology [

31]. The gradual reduction in ash content over time underscores the sensitivity of microgreen minerals to environmental conditions during storage.

4.2. Analysis of Chlorophyll a and b, ß—Carotene and Anthocyanins of Microgreens as a Function of Stoage Days.

The results demonstrate that storage time plays a critical role in determining the stability of bioactive pigments in microgreens.

The higher chlorophyll a content observed in broccoli on day 0 indicates a greater capacity to retain photosynthetic pigments during the early postharvest stages. This trend is consistent with studies on phytonutrient content and yield of brassica microgreens, which found chlorophyll a content between 0.80 and 1.18 mg/g fresh weight in cabbage microgreens, chlorophyll degradation over time can be attributed to enzymatic oxidation and exposure to light or temperature fluctuations, which reduce the stability of photosynthetic pigments [

32]. Similarly, research on oxidative stress in plants mentions that chlorophyll levels are key indicators of photosynthetic efficiency and plant vitality, so its conservation is essential to maintain nutritional quality [

33].

The higher chlorophyll b content present in cabbage confirms the greater capacity for photosynthetic pigment synthesis of

Brassicaceae species. Studies on growth and phytochemical enhancement of two amaranth microgreens by LED light irradiation reported comparable values (2.5–3.0 mg/g fresh weight) in amaranth microgreens grown under LED light, highlighting that light quality and intensity significantly influence chlorophyll biosynthesis. Therefore, the observed differences between families suggest that both genetic factors and cultivation conditions affect chlorophyll accumulation and retention during storage [

34].

Regarding β-carotene, the higher concentration observed in beetroot (0.91 µg/g fresh weight) compared to other species shows a high potential as a natural source of provitamin A, essential for antioxidant defense, visual function and the body’s immune response. This value exceeds those reported in broccoli microgreens grown under controlled artificial lighting conditions [

35]. The difference can be attributed to the variability in the light spectrum used, the type and quantity of pigments present, as well as the specific metabolic activity of each species. Furthermore, it has been pointed out that β-carotene content is strongly influenced by factors of the growth environment and by post-harvest handling, which must be optimized to maximize the stability and conservation of this bioactive compound [

36].

The anthocyanin content was markedly higher in beetroot and red amaranth, both belonging to pigment-rich families such as

Amaranthaceae. These findings are consistent with previous research reporting anthocyanin degradation after dehydration in microgreens, confirming the sensitivity of these compounds to environmental factors [

37]. Moreover, pH levels and substrate composition have been shown to significantly influence anthocyanin biosynthesis and stability [

38]. Therefore, maintaining optimal cultivation and storage conditions particularly temperature, light, and pH could enhance the retention of these valuable pigments and improve both the nutritional and sensory quality of microgreens.

4.3. Analysis of Mineral Macro and Microelements of the Varieties Studied on Day 5

The obtained results demonstrate that microgreens are excellent sources of essential minerals, confirming their role as nutrient-dense foods suitable for human consumption and dietary enrichment. The predominance of potassium in cabbage (5600 mg/kg) is consistent with previous reports showing that potassium levels in Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis microgreens were nearly tenfold higher than those of magnesium and calcium, highlighting potassium’s central role in osmotic regulation, enzyme activation, and photosynthetic efficiency [

39].

Similarly, the elevated calcium, phosphorus, and magnesium concentrations found in broccoli microgreens (880, 520, and 290 mg/kg, respectively) are consistent with previous reports showing that these macronutrients are particularly concentrated in

Brassicaceae microgreens compared to their mature counterparts [

40]. These minerals are critical for structural functions such as cell wall stability and bone mineralization, as well as for metabolic processes including ATP synthesis and energy transfer [

41].

The relatively high iron (12 mg/kg) and zinc (4.6 mg/kg) levels in beetroot microgreens underscore their potential contribution to oxygen transport and enzymatic reactions, as both elements are indispensable cofactors for redox enzymes and heme-proteins. These results are consistent with previous reports showing iron concentrations ranging from 100–118 ppm and manganese levels between 34–77 ppm in various microgreen species. Moreover, mineral accumulation is significantly affected by the growth stage, with calcium content increasing markedly between Days 5 and 7 of development [

30].

Taken together, these findings highlight that the mineral composition of microgreens is strongly determined by the species grown and the growth conditions employed. The high bioavailability of these minerals in young seedlings reinforces their potential as functional foods, capable of complementing dietary micronutrient intake and contributing to the maintenance of metabolic balance, positioning them as a valuable nutritional alternative in healthy eating strategies.

4.4. Antioxidant Capacity of Microgreens

The high antioxidant capacity found in beet and broccoli microgreens highlights their potential as functional foods that can contribute to cellular protection against oxidative damage [

42]. This superior activity may be attributed to their high content of phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and vitamins synthesized during the early growth stages. Conversely, the lower values obtained for cabbage microgreens could be related to the variability in the bioactive compound profile of each species, as well as to external factors such as cultivation method and environmental conditions [

43].

Broccoli and beetroot microgreens generally exhibited higher antioxidant capacities compared to other species, reflecting their rich content of bioactive compounds. These observations are in line with previous studies reporting similar trends in mature vegetables, where

Brassicaceae and pigment-rich species consistently demonstrated elevated antioxidant activity [

27,45]. This suggests that microgreens from these families could serve as potent dietary sources of antioxidants, with potential benefits for oxidative stress mitigation and overall human health.

5. Conclusions

The analyzed microgreens, including Brassica oleracea (broccoli and cabbage), Beta vulgaris (beetroot), and Amaranthus (red amaranth), exhibited a nutritional profile rich in moisture, protein, fiber, and essential minerals. During storage, moisture content generally increased in some species, while protein, fat, fiber, and ash tended to decrease, reflecting changes in their overall nutritional composition. For instance, broccoli protein declined from 3.50 to 2.90 g/100 g between Day 0 and Day 10. Regarding bioactive compounds, chlorophyll and antioxidant levels showed progressive deterioration over time. Broccoli chlorophyll content decreased from 2.50 to 2.00 mg/g within ten days, whereas beet and red amaranth maintained relatively stable anthocyanin levels (29.40 µmol/100 g and 18.67 µmol/100 g, respectively), reflecting their high antioxidant potential, which ranged from 547 mg EAA/g in beet to 540 mg EAA/g in red amaranth. Mineral analysis further demonstrated that microgreens are a rich source of essential macro- and micronutrients. Broccoli contained elevated levels of calcium (880 mg/kg) and iron (12 mg/kg), while beet was particularly notable for its iron content, reaching 22 mg/kg. These findings underscore the potential of microgreens to prevent nutritional deficiencies, especially in populations relying on plant-based sources to meet micronutrient requirements. In conclusion, the analyzed microgreens offer a remarkable nutritional and functional profile; however, proper storage and management of contamination risks are essential to preserve their quality, maximize nutritional benefits, and ensure consumer safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KRE and DSA; Methodology, DSA; Software, KRE; Validation, SSLL, JNM, and ACC; Formal Analysis, SAA; Research, NRM; Resources, JNM; Data Curation, RRE; Writing: Preparation of Original Draft, JAM; Writing: Review and Editing, SSLL; Visualization, NRM; Supervision, SAA; Project Administration, JAM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Authors thankful to Universidad Pública de Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas, for the support and encouragement through this investigation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Renna, M.; Paradiso, V. M. Ongoing Research on Microgreens: Nutritional Properties, Shelf-Life, Sustainable Production, Innovative Growing and Processing Approaches. Foods, 2020, 9 (6). [CrossRef]

- Bhaswant, M.; Shanmugam, DK.; Miyazawa, T.; Abe, C.; Miyazawa, T. Microgreens—A Comprehensive Review of Bioactive Molecules and Health Benefits. Molecules, 2023, 28 (2), 867. https ://do/10/moléculas28020867.

- Kyriacou, MC.; Rouphael, Y.; Di Gioia, F.; Kyratzis, A.; Serio, F.; Renna, M.; Santamaría, P. Micro-scale vegetable production and the rise of microgreens. Trends Food Sci. Technol, 2016, 57, 103-115. [CrossRef]

- Amuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Viršilė, A.; Milauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V.; Duchovskis, P. Nutrient Levels in Brassicaceae Microgreens Increase Under Tailored Light-Emitting Diode Spectra. Front. Plant Sci. 2019 10 . [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.; Ciriello, M.; Formisano, L.; El-Nakhel, C.; Pannico, A.; Graziani, J.; De Pascale, S. Iodine-Biofortified Microgreens as High Nutraceutical Value Component of Space Mission Crew Diets and Candidate for Extraterrestrial Cultivation. Plants 2023, 12(14). [CrossRef]

- Iggio, G.M.; Wang, Q.; Kniel, K.E.; Gibson, K.E. Microgreens—A Review of Food Safety Considerations along the Farm to Fork Continuum. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2019, 290, 76–85. [CrossRef]

- Zhihao, L.; Shi, J.; Wan, J.; Pham, Q.; Zhi, Z.; Jianghao, S.; Chen, P. Profiling of Polyphenols and Glucosinolates in Kale and Broccoli Microgreens Grown under Chamber and Windowsill Conditions by Ultrahigh-Performance Liquid Chromatography High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.R.; Su, J.; Gu, L.J. Comparison of Glucosinolate Profiles in Different Tissues of Nine Brassica Crops. Molecules 2015, 20(9), 15827–15841. [CrossRef]

- Sbin, O.; Raluca, M.P.; Bocsan, I.C.; Sandra-Chedea, V.; Ranga, F.; Grozav, A.; Bizoianu, A.D. The Anti-Inflammatory, Analgesic, and Antioxidant Effects of Polyphenols from Brassica oleracea var. capitata Extract on Induced Inflammation in Rodents. Molecules 2024, 29(15). [CrossRef]

- Rocchetti, G.; Tomas, M.; Zhang, L.; Zengin, G.; Lucini, L.; Capanoglu, E. Red Beet (Beta vulgaris) and Amaranth (Amaranthus sp.) Microgreens: Effect of Storage and In Vitro Gastrointestinal Digestion on the Untargeted Metabolomic Profile. Food Chem. 2020, 332, 127415. [CrossRef]

- Johnsoon, S.; Renni, J.; Heuberger, A.; Isweiri, H.; Chaparro, J.M.; Newman, S.; Weir, T. Comprehensive Evaluation of Metabolites and Minerals in Six Microgreen Species and the Influence of Maturity. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2020, 18(2). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7897203.

- Insuasty-Santacruz, E.; Jurado-Gámez, H. Forage Beet (Beta vulgaris) Sown in Microtunnels and Its Effect on Productive Parameters of Guinea Pigs. Biotechnol. Agron. Agroind. Sect. 2020, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Lester, G.E.; Luo, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q. Effect of Light Exposure on Sensory Quality, Concentrations of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Radish Microgreens during Low Temperature Storage. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 472–479. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Lester, G. E.; Luo, Y.; Xie, Z.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q. Effect of light exposure on sensory quality, concentrations of bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of radish microgreens during low temperature storage. Food Chemistry 2014, 151, 472–479. [CrossRef]

- Mir, S. A.; Shah, M. A.; Maqbul Mir, M. Microgreens: Production, shelf life, and bioactive components. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2017, 57. [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Siddiqui, S.; Phogat, N. Effect of chemical treatment, storage and packaging on physico-chemical properties of sunflower microgreens. International Journal of Chemical Studies 2019, 7(5). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338885417.

- Kou, L.; Luo, Y.; Parque, E.; Turner, E. R.; Barczak, A.; Jurick II, W. M. Temperature abuse timing affects the rate of quality deterioration of commercially packaged ready-to-eat baby spinach. Part I: Sensory analysis and selected quality attributes. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2014, 91. [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7(6). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhenlei, X.; Ager, E.; Kong, L.; Tan, L. Nutritional quality and health benefits of microgreens, a crop of modern agriculture. Journal of Future Foods 2021, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ghoora, M. D.; Haldipur, A. C.; Nagarajan, S. Comparative evaluation of phytochemical content, antioxidant capacities and overall antioxidant potential of select culinary microgreens. Journal of Agricultural Research 2020. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341046142_Comparative_evaluation_of_phytochemical_content_antioxidant_capacities_and_overall_antioxidant_potential_of_select_culinary_microgreens.

- TRIDGE, Microgreens 2023. https://www.tridge.com/intelligences/microgreen. Accessed 29 December 2024.

- IMARC. Microgreens Market Report by Type (Broccoli, Cabbage, Cauliflower, Arugula, Peas, Basil, Radish, and Others), Farming Method (Indoor Vertical Farming, Commercial Greenhouses, and Others), End Use (Residential, Commercial), Distribution Channel (Supermarkets and Hypermarkets, Retail Stores, and Others), and Region 2025-2033. Report ID SR112024A4310 2024. https://www.imarcgroup.com/microgreens-market/toc. Accessed 29 December 2024.

- Samuolienė, G.; Brazaitytė, A.; Viršilė, A.; Miliauskienė, J.; Vaštakaitė-Kairienė, V.; Duchovskis, P. Nutrient levels in Brassicaceae microgreens increase under tailored light-emitting diode spectra. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 1475. [CrossRef]

- Sanpinit, S.; Goon, J. A.; Wetchakul, P. Characterization of the antioxidant activity, identified free radical-relieving components by LC/QTOF/MS and acute oral toxicity studies of Tri-Tharn-Thip tea. Journal of Agriculture and Food Research 2024, 16, 101131. [CrossRef]

- Kowitcharoen, L.; Phornvillay, S.; Lekkham, P.; Pongpraset, N.; Srilaong, V. Bioactive composition and nutritional profile of microgreens cultivated in Thailand. Applied Sciences 2021, 11(17). [CrossRef]

- Sanyukta; Singh-Brar, D.; Pannt, K.; Kaur, S.; Nanda, V.; Ahmad-Nayik, G.; Ercisli, S. Comprehensive analysis of physicochemical, functional, thermal, and morphological properties of microgreens from different botanical sources. ACS Omega 2023, 8(32), 29558–29567. [CrossRef]

- Paradiso, V. M.; Castellino, M.; Renna, M.; Gattullo, C. E.; Calasso, M.; Terzano, R.; Santamaria, P. Nutritional characterization and shelf-life of packaged microgreens. Food Function 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gunjal, M.; Singh, J.; Kaur, J.; Kaou, S.; Nanda, V.; Mohan-Mehta, C.; Rasane, P. Comparative analysis of morphological, nutritional, and bioactive properties of selected microgreens in alternative growing medium. South African Journal of Botany 2024, 165. [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, R.; Parashar, A.; Parewa, H.; Vyas, L. An alarming decline in the nutritional quality of foods: The biggest challenge for future generations’ health. Foods 2024, 13(6), 877. [CrossRef]

- Ayeni, A. Nutrient content of micro/baby-green and field-grown mature foliage of tropical spinach (Amaranthus sp.) and roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.). Foods 2021, 10(11), 2546. [CrossRef]

- Brar, D.; Pant, K.; Kaur, S.; Nanda, V.; Nayik, G.; Ramniwas, S.; Ercisli, S. Comprehensive analysis of physicochemical, functional, thermal, and morphological properties of microgreens from different botanical sources. ACS Omega 2023, 8. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/acsomega.3c03429.

- Ntsoane, M. L.; Manhivi, V. E.; Shoko, T.; Seke, F.; Maboko, M. M.; Sivakumar, D. The phytonutrient content and yield of Brassica microgreens grown in soilless media with different seed densities. Horticulturae 2023, 9(11). [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Fujita, M. Plant oxidative stress: Biology, physiology and mitigation. Plants 2022, 11(9). [CrossRef]

- Meas, S.; Luengwilai, K.; Thongket, T. Enhancing Growth and Phytochemicals of Two Amaranth Microgreens by LED Light Irradiation. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 265, 109204. [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Olivas, A.L.; Bernal-Triviño, N.; Álvarez-Chávez, C.R.; Mendoza-Cariño, M. Productive and Nutritional Evaluation of Broccoli Sprouts Grown under Artificial Light. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2021, 46(4). [CrossRef]

- Otálora-Orrego, D.; Martin, D. Emerging β-Carotene Extraction Techniques for the Valorization of Agroindustrial By-Products from Carrot (Daucus carota L.): A Review. Inf. Tecnol. 2021, 85(1). [CrossRef]

- Keutgen, N.; Hausknecht, M.; Tomaszewska-Sowa, M.; Keutgen, A.J. Nutritional and Sensory Quality of Two Types of Cress Microgreens Depending on the Mineral Nutrition. Agronomy 2021, 11(6). [CrossRef]

- Saleh, R.; Gunupuru, L.R.; Lada, R.; Nams, V.; Thomas, R.H.; Abbey, L. Growth and Biochemical Composition of Microgreens Grown in Different Formulated Soilless Media. Plants 2022, 11(24). [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Tan, W.K.; Du, Y.; Lee, H.; Liang, X.; Lei, J.; Ong, C. Nutritional Metabolites in Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis var. parachinensis (Choy Sum) at Three Different Growth Stages: Microgreen, Seedling and Adult Plant. Food Chem. 2021, 357, 129535. [CrossRef]

- Jones-Baumgardt, C.; Llewellyn, D.; Ying, Q.; Zheng, Y. Intensity of Sole-Source Light-Emitting Diodes Affects Growth, Yield, and Quality of Brassicaceae Microgreens. HortScience 2019, 54(7), 1168–1174. [CrossRef]

- Dubey, S.; Harbourne, N.; Harty, M.; Hurley, D.; Elliott-Kingston, C. Microgreens Production: Exploiting Environmental and Cultural Factors for Enhanced Agronomical Benefits. Plants 2024, 13(18), 2631. [CrossRef]

- Puangkam, K.; Muanghorm, W.; Konsue, N. Stability of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Thai Cruciferous Vegetables during In Vitro Digestion. Curr. Nutr. Res. Food Sci. 2017, 5, 100–108. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, E.; Cieslik, E.; Leszczynska, T.; Filipiak-Florkiewicz, A.; Pisulewski, P. The Antioxidant Activity of Selected Cruciferous Vegetables Subjected to Aquathermal Processing. Food Chem. 2008, 107, 55–59. [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, B.; López-García, G.; Máñez, V.; Alegría, A.; Barberá, R.; Cilla, A. Evaluation of the Bioaccessibility of Antioxidant Bioactive Compounds and Minerals of Four Genotypes of Brassicaceae Microgreens. Foods 2019, 8(7), 250. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).