Submitted:

10 October 2023

Posted:

11 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study area and selection of cocoa clones

2.2. Fermentation, drying and roasting of cocoa beans

2.3. Determination of chemical characteristics of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

2.4. Statistical analysis

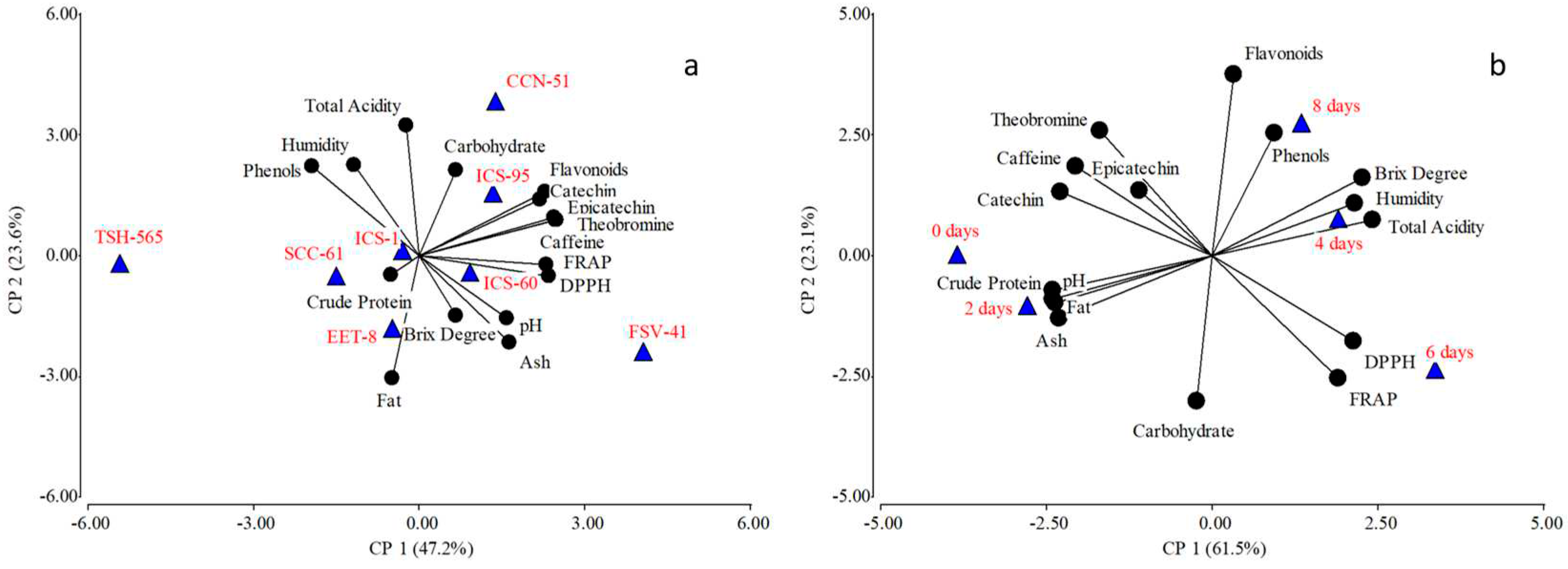

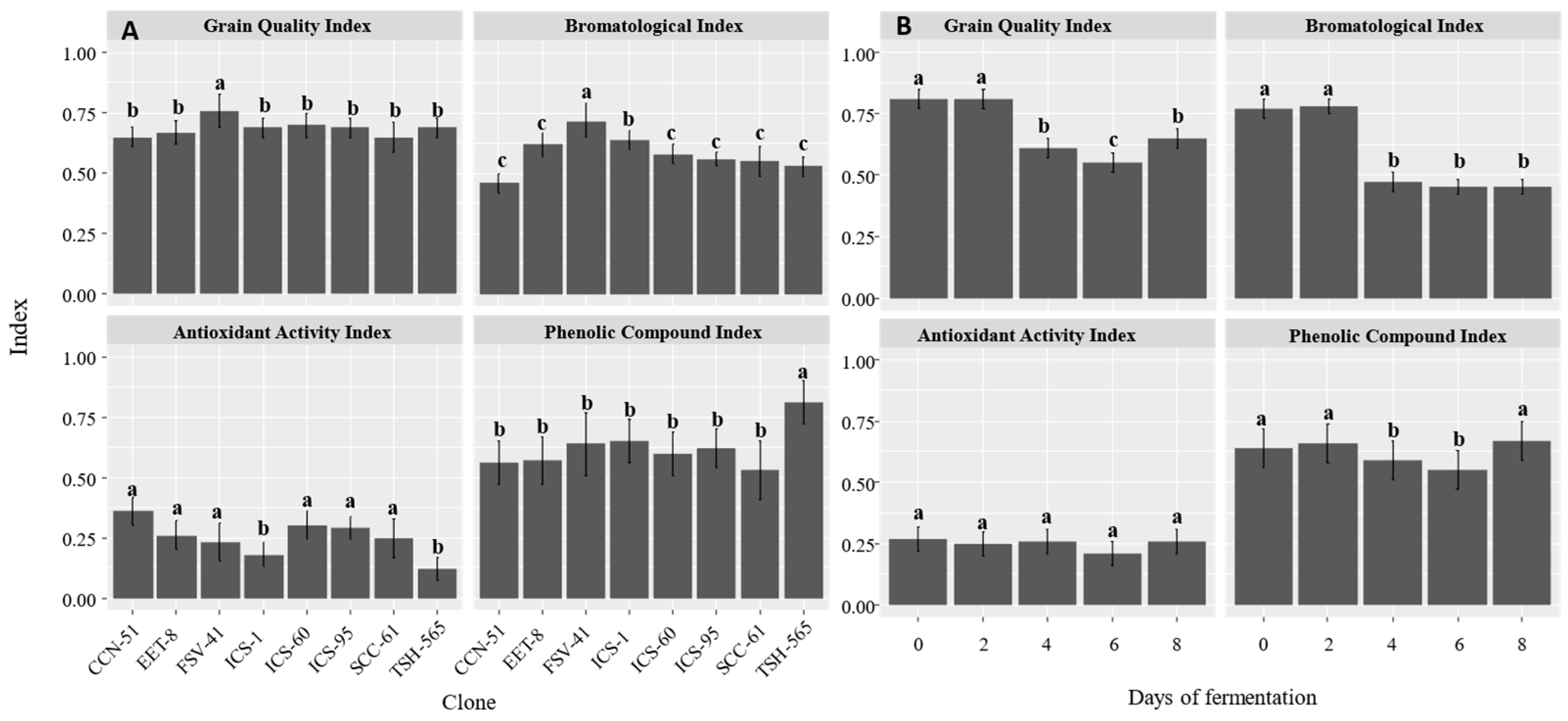

3. Results

3.1. Bromatological characteristics of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

3.2. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

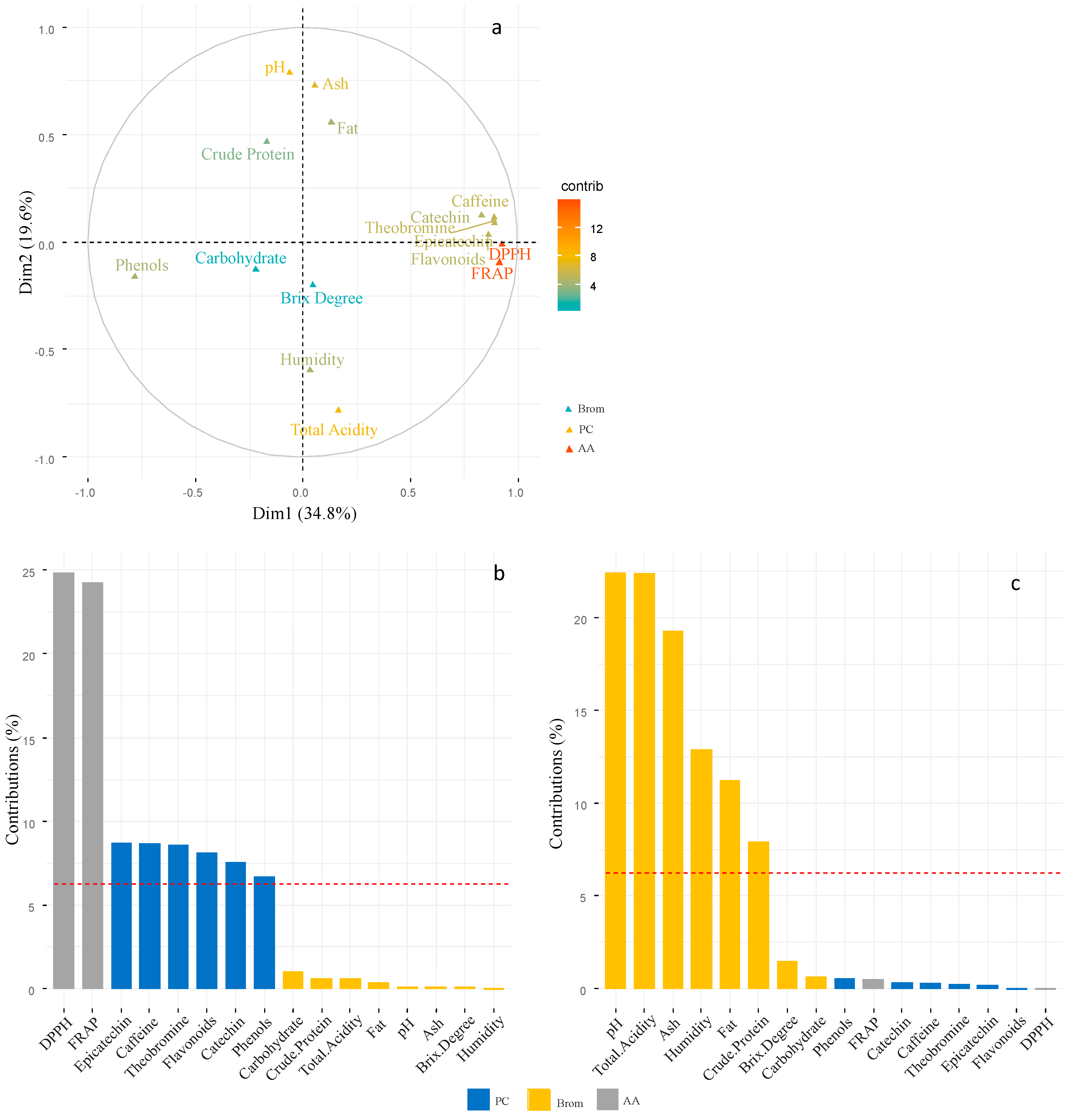

3.3. Correlations between the different bromatological characteristics, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of cocoa beans

4. Discussion

4.1. Bromatological characteristics of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

4.2. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

4.3. Correlation of bromatological characteristics, phenolic compounds, and antioxidant activity of beans from different cocoa clones during the fermentation process

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- ICCO. ICCO quarterly bulletin of cocoa statistics. The International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) Cocoa Producing and Cocoa Consuming Countries. Supply & Demand QBCS XLVIII No. 1. 2022.

- ICCO. Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistcs. Vol. XLIII, Quarterly Bulletin of cocoa statistics. Côte d’Ivoire; 2017. 20–29 p.

- Hernández-Núñez, H.E.; Gutiérrez-Montes, I.; Bernal-Núñez, A.P.; Gutiérrez-García, G.A.; Suárez, J.C.; Casanoves, F.; Flora, C.B. Cacao cultivation as a livelihood strategy: contributions to the well-being of Colombian rural households. Agric. Hum. Values 2021, 39, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera V, Alwang J, Casanova T, Domínguez J, Escudero L, Loor G, et al. La cadena de valor del cacao en y el bienestar de los productores de la provincia de Manabí-Ecuador [Internet]. Iniap. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 19]. 1–204 p. Available from: http://repositorio.iniap.gob. 4100.

- FEDECACAO. Colombia Cacaotera. Federación Nacional de Cacaoteros [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 Feb 19];24. Available from: https://drive.google.

- González, X. La producción de cacao alcanzó cifra récord en 2020 y llegó a las 63.416 toneladas [Internet]. La República. 2021 [cited 2023 Feb 19]. p. Agronegocios. Available from: https://www.google.com/search?q=La+producción+de+cacao+alcanzó+cifra+récord+en+2020+y+llegó+a+las+63.416+toneladas. 1676. [Google Scholar]

- Johanna Gómez González K, Carolina Londoño López V. Analysis of variables for the export of Colombian cocoa to European countries. 2017.

- Kongor, J.E.; Hinneh, M.; Van de Walle, D.; Afoakwa, E.O.; Boeckx, P.; Dewettinck, K. Factors influencing quality variation in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) bean flavour profile — A review. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hue, C.; Gunata, Z.; Breysse, A.; Davrieux, F.; Boulanger, R.; Sauvage, F. Impact of fermentation on nitrogenous compounds of cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) from various origins. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 958–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Campos, J.; Escalona-Buendía, H.; Orozco-Avila, I.; Lugo-Cervantes, E.; Jaramillo-Flores, M. Dynamics of volatile and non-volatile compounds in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) during fermentation and drying processes using principal components analysis. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Bustamante S, Tamayo Tenorio A, Alberto Rojano B. Efecto del Tostado Sobre los Metabolitos Secundarios y la Actividad Antioxidante de Clones de Cacao Colombiano. Rev Fac Nac Agron Medellín [Internet]. 2015 Jan 1 [cited 2023 Feb 19];68(1):7497–507. Available from: https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index. 4783.

- Martinez, N. Evaluación de componentes físicos, químicos, organolépticos y de rendimiento de clones universales y regionales de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en las zonas productoras de Santander, Arauca y Huila. Magister. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Cienci. 2016.

- Ramírez González MB, Cely Niño VH, Ramírez SI. Actividad antioxidante de clones de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) finos y aromáticos cultivados en el estado de Chiapas, México. Perspect EN Nutr HUMANA [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Feb 19];15(1):27–47. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php? 0124.

- Nazario O, Elizabeth Ordoñez ;, Mandujano Y, Arévalo J. Polifenoles totales, antocianinas, capacidad antioxidante de granos secos y análisis sensorial del licor de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) criollo y siete clones. Investig y Amaz. 2013;3(1):51–9.

- Sukha, D.A.; Butler, D.R.; Umaharan, P.; Boult, E. The use of an optimised organoleptic assessment protocol to describe and quantify different flavour attributes of cocoa liquors made from Ghana and Trinitario beans. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2007, 226, 405–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, Luis. Quevedo, José. García R. Determinación del efecto del grado de madurez de las mazorcas en la producción y la calidad sensorial de (Theobroma cacao L.). Rev Científica Agroecosistemas [Internet]. 2017 Dec 11 [cited 2023 Feb 19];5(1):36–46. Available from: https://aes.ucf.edu.cu/index.

- Roos, W. ÍNDICE MIP DE ALGUNOS CULTIVOS TROPICALES [Internet]. EDICIONES. 2015 [cited 2023 Feb 19]. 119 p. Available from: https://www.cabi.org/wp-content/uploads/Rogg-2000b-IPM-in-tropical-crops.

- Boza, E.J.; Motamayor, J.C.; Amores, F.M.; Cedeño-Amador, S.; Tondo, C.L.; Livingstone, D.S.; Schnell, R.J.; Gutiérrez, O.A. Genetic Characterization of the Cacao Cultivar CCN 51: Its Impact and Significance on Global Cacao Improvement and Production. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2014, 139, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekele, F.L.; Bekele, I.; Butler, D.R.; Bidaisee, G.G. Patterns of Morphological Variation in a Sample of Cacao (Theobroma Cacao L.) Germplasm from the International Cocoa Genebank, Trinidad. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2006, 53, 933–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.S.; Bekele, F.L.; Brown, S.J.; Song, Q.; Zhang, D.; Meinhardt, L.W.; Schnell, R.J. Population Structure and Genetic Diversity of the Trinitario Cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) from Trinidad and Tobago. Crop. Sci. 2009, 49, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Núñez HE, Gutiérrez-Montes I, Sánchez-Acosta JR, Rodríguez-Suárez L, Gutiérrez-García GA, Suárez-Salazar JC, et al. Agronomic conditions of cacao cultivation: its relationship with the capitals endowment of Colombian rural households. Agrofor Syst. 2020.

- Loureiro, G.A.H.A.; Araujo, Q.R.; Sodré, G.A.; Valle, R.R.; Souza, J.O.; Ramos, E.M.L.S.; Comerford, N.B.; Grierson, P.F. Cacao quality: Highlighting selected attributes. Food Rev. Int. 2016, 33, 382–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón, V.; Hernández, H.E.; Polania, P.; Suárez, J.C. Spatial Distribution of Cocoa Quality: Relationship between Physicochemical, Functional and Sensory Attributes of Clones from Southern Colombia. Agronomy 2022, 13, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaniego, I.; Espín, S.; Quiroz, J.; Ortiz, B.; Carrillo, W.; García-Viguera, C.; Mena, P. Effect of the growing area on the methylxanthines and flavan-3-ols content in cocoa beans from Ecuador. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2020, 88, 103448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 19th ed. (970.22). Association of Official Analytical Chemists International. 2012.

- García E, Fernández I. Determinación de proteínas de un alimento por el método Kjeldahl. Valoración con un ácido fuerte. [Internet]. ETSIAMN. Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Universitat Politècnica de València; 2020 Jun [cited 2023 Feb 19]. Available from: https://riunet.upv. 1025.

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano PG, Paladines MB. Actividad antioxidante de extractos de granos de copoazú (Theobroma grandiflorum). Vitae [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2023 Feb 19];19(1):436–8. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1698/169823914137.

- Zhishen, J.; Mengcheng, T.; Jianming, W. The determination of flavonoid contents in mulberry and their scavenging effects on superoxide radicals. Food Chem. 1999, 64, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzidimitriou, E.; Nenadis, N.; Tsimidou, M.Z. Changes in the catechin and epicatechin content of grape seeds on storage under different water activity (aw) conditions. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto M del R, Gutiérrez L, Delgado Y, Gallignani M, Zambrano A, Gómez Á, et al. Determination of theobromine, theophylline and caffeine in cocoa samples by a high-performance liquid chromatographic method with on-line sample cleanup in a switching-column system. Food Chem. 2007 Jan 1;100(2):459–67.

- Velásquez H, Galeano P. Evaluación fitoquímica y de actividad antioxidante de los rizomas de tres especies del género Cyperus. Momentos Cienc. 2012;9(1):15–21.

- Balzarini M, Di Rienzo J, Tablada M, Gonzalez L, Bruno C, Córdoba M, et al. Estadística y biometrías. Ilustraciones del uso de InfoStat en problemas de agronomía. Editorial Brujas, Córdoba, Argentina. Segunda Edición. 2012. 380 p.

- Rienzo D, Alejandro J, Alicia L, Margot E, Pilar M. Estadistica para las ciencias agropecuarias. Potencia. 2005. 1–329 p.

- R Development Core Team. R: The R Project for Statistical Computing. In: Foundation for Statistical Computing, V., Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0 (Ed.). 2023; Available from: https://www.r-project.org/.

- Del M, Amaíz CL, Gutiérrez R, Pérez E, Álvarez C. Efecto del tostado sobre las propiedades físicas, fisicoquímicas, composición proximal y perfil de ácidos grasos de la manteca de granos de cacao del estado Miranda, Venezuela Effect of roasting process on physical and physicochemical properties, proximat [Internet]. Vol. 12, Revista Científica UDO Agrícola. Universidad de Oriente; 2012 [cited 2023 Feb 19]. Available from: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo? 4688.

- lvarez C, Pérez E, Lares MC. Caracterización física y química de almendras de cacao fermentadas, secas y tostadas cultivadas en la región de Cuyagua, estado Aragua. Agron Trop [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2022 Oct 18];57(4):249–56. Available from: http://ve.scielo.org/scielo.php? 0002.

- Perea JA, Ramirez OL, Villamizar AR. Caracterización fisicoquimica de materiales regionales de cacao colombiano. Biotecnol en el Sect Agropecu y Agroindustrial [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2022 Oct 18];9(1):35–42. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php? 1692.

- Vera Chang JF, Vallejo Torres C, Párraga Morán DE, Macías Véliz J, Ramos Remache R, Morales Rodríguez W. Atributos físicos-químicos y sensoriales de las almendras de quince clones de cacao nacional (Theobroma cacao L.) en el Ecuador. Cienc y Tecnol [Internet]. 2015 Mar 19 [cited 2022 Oct 18];7(2):21–34. Available from: https://revistas.uteq.edu.ec/index.

- AOAC. Ash (acid-insoluble) of cacao products. AOAC 975.12. [Internet]. 2000 [cited 2023 Feb 20]. Available from: http://www.aoacofficialmethod.org/index.php?

- lvarez R, Portillo E, Portillo A, Villasmil R. Evaluación de las propiedades sensoriales del licor de cacao (theobroma cacao l.) obtenido en forma artesanal e industrial. Rev Agrollanía [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2022 Oct 18];15:1690–8066. 8: Available from: http://localhost, 8080.

- Mustiga, G.M.; Morrissey, J.; Stack, J.C.; DuVal, A.; Royaert, S.; Jansen, J.; Bizzotto, C.; Villela-Dias, C.; Mei, L.; Cahoon, E.B.; et al. Identification of Climate and Genetic Factors That Control Fat Content and Fatty Acid Composition of Theobroma cacao L. Beans. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rosario Castro M, Hernández JA, Marcilla S, Córdova JS, Solari FA, Chire GC. Efecto del contenido de grasa en la concentración de polifenoles y capacidad antioxidante de Theobroma cacao L. “Cacao.” Cienc Invest [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Feb 19];19(1):19–23. Available from: https://www.researchgate. 3081.

- Servent, A.; Boulanger, R.; Davrieux, F.; Pinot, M.-N.; Tardan, E.; Forestier-Chiron, N.; Hue, C. Assessment of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) butter content and composition throughout fermentations. Food Res. Int. 2018, 107, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade JA, Rivera-García J, Chire-Fajardo GC, Ureña-Peralta MO. Propiedades físicas y químicas de cultivares de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) de Ecuador y Perú. Enfoque UTE [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 19];10(4):1–12. Available from: http://scielo.senescyt.gob.ec/scielo.php? 1390.

- Barrientos, L.D.P.; Oquendo, J.D.T.; Gil Garzón, M.A.; Álvarez, O.L.M. Effect of the solar drying process on the sensory and chemical quality of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) cultivated in Antioquia, Colombia. Food Res. Int. 2018, 115, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imru NO, Wogderess MD, Gidada T V. A study of the effects of shade on growth, production and quality of coffee (COFFEA ARABICA) in Ethiopia. Int J Agric Sci [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 Feb 19];5(5):748–52. Available from: http://www.academicjournals.

- Afoakwa EO, Ofosu-Ansah E, Takrama JF, Budu AS, Mensah-Brown H. Changes in chemical quality of cocoa butter during roasting of pulp pre-conditioned and fermented cocoa (Theobroma cacao) beans. Int Food Res J [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2023 Feb 19];21(6):2221–7. Available from: https://www.researchgate. 2763.

- Rohan, T.A.; Stewart, T. The Precursors of Chocolate Aroma: Changes in the Sugars During the Roasting of Cocoa Beans. J. Food Sci. 1966, 31, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Bustamante S, Tamayo Tenorio A, Alberto Rojano B. Efecto de la fermentación sobre la actividad antioxidante de diferentes clones de cacao Colombiano. Rev Cuba Plantas Med [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 Feb 20];18(3):391–404. Available from: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php? 1028.

- Zzaman, W.; Bhat, R.; Abedin, Z.; Yang, T.A. Comparison between Superheated Steam and Convectional Roasting on Changes in the Phenolic Compound and Antioxidant Activity of Cocoa Beans. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2013, 19, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lujano E, Manganiello L, Contento A, Rios A. Identification and quantification of (+) - Catechins and Procyanidins in Cocoa from Ocumare de la Costa, Venezuela. Ing Uc. 2019;26(2):192–201.

- Alvarez, L.C.; Alvarez, N.C.; Garcia, P.G.; Salazar, J.C.S. Effect of fermentation time on phenolic content and antioxidant potential in Cupuassu (Theobroma grandiflorum (Willd. ex Spreng.) K.Schum.) beans. 2017, 66, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuskoski EM, Asuero AG, Troncoso AM, Mancini-Filho J, Fett R. Aplicación de diversos métodos químicos para determinar actividad antioxidante en pulpa de frutos. Ciência e Tecnol Aliment [Internet]. 2005 Dec [cited 2023 Feb 19];25(4):726–32. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/j/cta/a/B58T9S5zLLxjBL5PVzZXHCF/abstract/?

- Roginsky, V.; Lissi, E.A. Review of methods to determine chain-breaking antioxidant activity in food. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea J, Cadena T, Herrera J. El cacao y sus productos como fuente de antioxidantes: Efecto del procesamiento. Salud UIS [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2023 Feb 19];41:128–34. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php? 0121.

- Apriyanto, M. Changes in Chemical Properties of Dreid Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) Beans during Fermentation. Int. J. Fermented Foods 2016, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo L, Mejía D, Acosta E, Valencia W, Penagos L. Efecto de la temperatura del conchado sobre los polifenoles en un chocolate semi-amargo. Aliment Hoy [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Feb 19];25(41):31–50. Available from: https://alimentoshoy.acta.org.co/index.

- Quiñones M, Miguel M, Aleixandre A. Los polifenoles, compuestos de origen natural con efectos saludables sobre el sistema cardiovascular. Nutr Hosp organo Of la Soc Espa??ola Nutr Parenter y Enter. 2012;27(1):76–89.

- Jinap, S.; Dimick, P.S. Acidic Characteristics of Fermented and Dried Cocoa Beans from Different Countries of Origin. J. Food Sci. 1990, 55, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Quao, J.; Takrama, J.; Budu, A.S.; Saalia, F.K. Chemical composition and physical quality characteristics of Ghanaian cocoa beans as affected by pulp pre-conditioning and fermentation. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 50, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Locatelli, M.; Travaglia, F.; Giovannelli, L.; Coïsson, J.D.; Bordiga, M.; Pattarino, F.; Arlorio, M. Clovamide and phenolics from cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.) inhibit lipid peroxidation in liposomal systems. Food Res. Int. 2013, 50, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez ES, Leon-Arevalo A, Rivera-Rojas H, Vargas E. Cuantificación de polifenoles totales y capacidad antioxidante en cáscara y semilla de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.), tuna (Opuntia ficus indica Mill), uva (Vitis Vinífera) y uvilla (Pourouma cecropiifolia). Sci Agropecu [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 19];10(2):175–83. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php? 2077.

- Ramos-Escudero, F.; Casimiro-Gonzales, S.; Fernández-Prior. ; Chávez, K.C.; Gómez-Mendoza, J.; de la Fuente-Carmelino, L.; Muñoz, A.M. Colour, fatty acids, bioactive compounds, and total antioxidant capacity in commercial cocoa beans (Theobroma cacao L.). LWT 2021, 147, 111629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Ismail, A.; Ghani, N.A.; Adenan, I. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of cocoa beans. Food Chem. 2007, 100, 1523–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto YT, Tomlinson B, Benzie IFF. Total antioxidant and ascorbic acid content of fresh fruits and vegetables: implications for dietary planning and food preservation. Br J Nutr [Internet]. 2002 Jan [cited 2023 Feb 19];87(1):55–9. Available from: https://www.cambridge. 4579.

- Sotelo, C. L, Alvis B. A, Arrázola P. G. Evaluación de epicatequina, teobromina y cafeína en cáscaras de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.), determinación de su capacidad antioxidante. Rev Colomb Ciencias Hortícolas [Internet]. 2015 Aug 12 [cited 2023 Feb 19];9(1):124. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php? 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Belščak A, Komes D, Horžić D, Ganić KK, Karlović D. Comparative study of commercially available cocoa products in terms of their bioactive composition. Food Res Int. 2009 Jun 1;42(5–6):707–16.

- Quizhpe PAC. Efecto inhibitorio de la pulpa que recubre las semillas del cacao (Theobroma Cacao) a diferentes concentraciones sobre la cepa de Streptococcus mutans: Estudio in … [Internet]. Quito: UCE; 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 19]. Available from: http://www.dspace.uce.edu. 2500.

- Peláez PP, Bardón I, Camasca P. Methylxanthine and catechin content of fresh and fermented cocoa beans, dried cocoa beans, and cocoa liquor. Sci Agropecu [Internet]. 2016 Dec 31 [cited 2023 Feb 19];7(4):355–65. Available from: http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php? 2077.

- Carrillo, L.C.; Londoño-Londoño, J.; Gil, A. Comparison of polyphenol, methylxanthines and antioxidant activity in Theobroma cacao beans from different cocoa-growing areas in Colombia. Food Res. Int. 2014, 60, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Introduced commercial | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nomenclature | Identification and origin | Characteristics of interest |

| CCN-51 | Castro Naranjal (Ecuador) | Commercially grown. High yield. Resistance to Monilia[18]. |

| EET-8 | United Fruit Company (Costa Rica) | Commercially grown. Good grain index[19]. |

| TSH-565 | Trinidad Selection Hybrid (Trinidad) | Resistance to Monilliphthora perniciosa, high productivity[20]. |

| ICS-1 | Imperial College Selection (Trinidad, Nicaragua y Venezuela) | Present in commercial crops in several countries. Good grain and cob index[19]. |

| ICS-60 | Imperial College Selection (Trinidad, Nicaragua y Venezuela) | Present in commercial crops in several countries. Good grain and cob index [19]. |

| ICS-95 | Imperial College Selection (Trinidad, Nicaragua y Venezuela) | Present in commercial crops in several countries. Good grain and cob index [19]. |

| Regional | ||

| SCC-61 | Selección Colombia Corpoica (Santander), Hibrido trinitario | High grain index[12]. |

| FSV-41 | Fedecacao San Vicente (Santander), Híbrido trinitario | High grain rate, yield and quality[12]. |

| Component | Variable | Unit | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bromatological | pH | Potentiometric [24] | |

| Moisture | % | Gravimetric [24] | |

| Ash | % | Incineration [25] | |

| Acidity | % | Titling [24] | |

| Fat | % | Soxhlet [24] | |

| Crude protein | % | Kjeldahl [26] | |

| Sucrose | °Brix | Refractometry [22] | |

| Total carbohydrates | mg g-1 | Phenol-Sulfuric [27] | |

| Phenolic compounds | Total phenols | mg g-1 | Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetry [28] |

| Total flavonoids | mg g-1 | Aluminum chloride [29] | |

| Catechin | mg g-1 | HPLC [30] | |

| Epicatechin | mg g-1 | HPLC [30] | |

| Theobromine | mg g-1 | HPLC [31] | |

| Caffeine | mg g-1 | HPLC [31] | |

| Antioxidant activity | DPPH | (µmol g-1) | Colorimetric [32] |

| FRAP | (µmol g-1) | Colorimetric [32] |

| Factor | Level | Moisture (%) | Ash (%) | pH | Acidity (%) | Fat (%) | Crude Protein (%) | Sucrose °Brix |

Total Carbohydrates (mg g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | CCN 51 | 2.98±0.16a | 3.03±0.09c | 5.14±0.09 | 0.56±0.03ab | 53.25±2.56 | 12.07±0.18c | 2.78±0.54b | 1.63±0.12 |

| EET 8 | 2.54±0.18abc | 3.17±0.10bc | 5.30±0.10 | 0.46±0.03c | 63.61±3.10 | 12.40±0.21bc | 3.42±0.61ab | 1.35±0.13 | |

| FSV 41 | 1.98±0.26c | 3.53±0.14a | 5.32±0.13 | 0.49±0.05bc | 60.66±4.99 | 12.60±0.28abc | 4.43±0.81ab | 1.55±0.18 | |

| ICS 1 | 2.38±0.15bc | 3.35±0.09ab | 5.16±0.09 | 0.54±0.03abc | 58.26±2.56 | 12.85±0.18a | 3.51±0.52ab | 1.62±0.11 | |

| ICS 60 | 2.65±0.18ab | 3.21±0.10bc | 5.17±0.10 | 0.49±0.03bc | 64.45±2.98 | 12.19±0.20c | 3.23±0.59b | 1.55±0.13 | |

| ICS 95 | 2.90±0.13a | 3.37±0.07ab | 5.10±0.08 | 0.59±0.02a | 55.66±2.07 | 12.50±0.16bc | 4.57±0.46a | 1.55±0.10 | |

| SCC 61 | 3.01±0.23a | 3.31±0.13abc | 5.35±0.12 | 0.52±0.04abc | 59.83±3.72 | 12.82±0.26ab | 3.97±0.76ab | 1.22±0.17 | |

| TSH 565 | 2.61±0.15ab | 3.15±0.08c | 5.11±0.09 | 0.55±0.03ab | 60.80±2.50 | 12.12±0.18c | 3.91±0.52ab | 1.53±0.11 | |

| P value | 0.0031 | 0.0017 | 0.1937 | 0.0420 | 0.0624 | 0.0009 | 0.0324 | 0.2789 | |

| Fermentation time(days) | 0 | 2.52±0.15ab | 3.47±0.08a | 5.49±0.08a | 0.42±0.03b | 65.44±2.38a | 12.90±0.17a | 3.29±0.51 | 1.49±0.11 |

| 2 | 2.21±0.14b | 3.58±0.08a | 5.51±0.08a | 0.43±0.03b | 62.37±2.10ab | 12.87±0.16a | 3.28±0.48 | 1.52±0.11 | |

| 4 | 2.75±0.14a | 3.15±0.08b | 4.99±0.08b | 0.61±0.03a | 56.69±2.14bc | 12.21±0.16b | 3.97±0.49 | 1.47±0.11 | |

| 6 | 2.86±0.14a | 3.07±0.08b | 4.98±0.08b | 0.60±0.03a | 55.70±2.10c | 12.14±0.16b | 3.98±0.48 | 1.56±0.11 | |

| 8 | 2.82±0.14a | 3.05±0.08b | 5.05±0.08b | 0.58±0.03a | 54.96±2.10c | 12.12±0.16b | 4.12±0.48 | 1.46±0.11 | |

| P value | 0.0004 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.0028 | <0.0001 | 0.2568 | 0.8975 |

| Factor | Level | Total Phenols (mg g-1) | Total Flavonoids (mg g-1) |

Catechin (mg g-1) |

Epicatechin (mg g-1) | Theobromine (mg g-1) | Caffeine (mg g-1) | DPPH (µmol g-1) |

FRAP (µmol g-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clone | CCN-51 | 64.56±11.74a | 3.30±0.57a | 1.95±0.06a | 0.49±0.01a | 0.30±0.01a | 0.37±0.01a | 325.55±33.30 | 331.00±34.29 |

| EET-8 | 42.71±7.63abc | 2.73±0.54a | 1.90±0.07a | 0.48±0.01ab | 0.29±0.01a | 0.37±0.01a | 251.47±40.26 | 244.72±41.45 | |

| FSV-41 | 46.46±19.37abc | 2.25±0.78abc | 1.82±0.09abc | 0.47±0.02abc | 0.29±0.01ab | 0.37±0.01ab | 168.71±64.91 | 169.51±66,84 | |

| ICS-1 | 47.55±7.30abc | 1.72±0.44bc | 1.78±0.05bc | 0.46±0.01bc | 0.29±0.01ab | 0.36±0.01ab | 245.23±33.30 | 248.29±34.29 | |

| ICS-60 | 39.93±7.54bc | 2.84±0.53a | 1.93±0.07a | 0.48±0.01a | 0.30±0.01a | 0.38±0.01a | 224.42±38.79 | 226.87±39.94 | |

| ICS-95 | 52.23±7.73ab | 2.55±0.43ab | 1.88±0.05ab | 0.48±0.01ab | 0.30±0.01a | 0.37±0.01a | 256.22±26.95 | 259.61±27.75 | |

| SCC-61 | 35.36±7.66c | 2.41±0.69abc | 1.87±0.08abc | 0.48±0.02ab | 0.29±0.01ab | 0.37±0.01ab | 275.00±48.38 | 278.95±49.82 | |

| TSH-565 | 60.97±8.27a | 1.29±0.42c | 1.71±0.05c | 0.44±0.01c | 0.28±0.01b | 0.35±0.01b | 350.01±32.56 | 356.18±33.42 | |

| P value | 0.0238 | 0.0063 | 0.0022 | 0.0213 | 0.0195 | 0.0117 | 0.0678 | 0.0678 | |

| Fermentation time (days) | 0 | 39.32±8.77 | 2.64±0.46 | 1.90±0.06 | 0.48±0.01 | 0.30±0.01 | 0.37±0.01 | 256.11±32.88 | 259.50±30.43 |

| 2 | 48.91±8.62 | 2.44±0.44 | 1.88±0.05 | 0.47±0.01 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.37±0.01 | 272.95±29.00 | 276.84±29.86 | |

| 4 | 52.91±8.64 | 2.36±0.46 | 1.85±0.05 | 0.47±0.01 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.37±0.01 | 291.95±29.55 | 296.40±30.43 | |

| 6 | 50.50±8.62 | 2.18±0.41 | 1.82±0.05 | 0.47±0.01 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.36±0.01 | 260.08±29.00 | 263.59±29.86 | |

| 8 | 51.97±8.62 | 2.31±0.43 | 1.83±0.05 | 0.47±0.01 | 0.29±0.01 | 0.37±0.01 | 283.11±29.00 | 287.30±29.86 | |

| P value | 0.5806 | 0.8314 | 0.3330 | 0.8945 | 0.2962 | 0.2282 | 0.9101 | 0.9101 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).