Submitted:

04 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Measurements During Vegetation

2.3. Preparation of samples

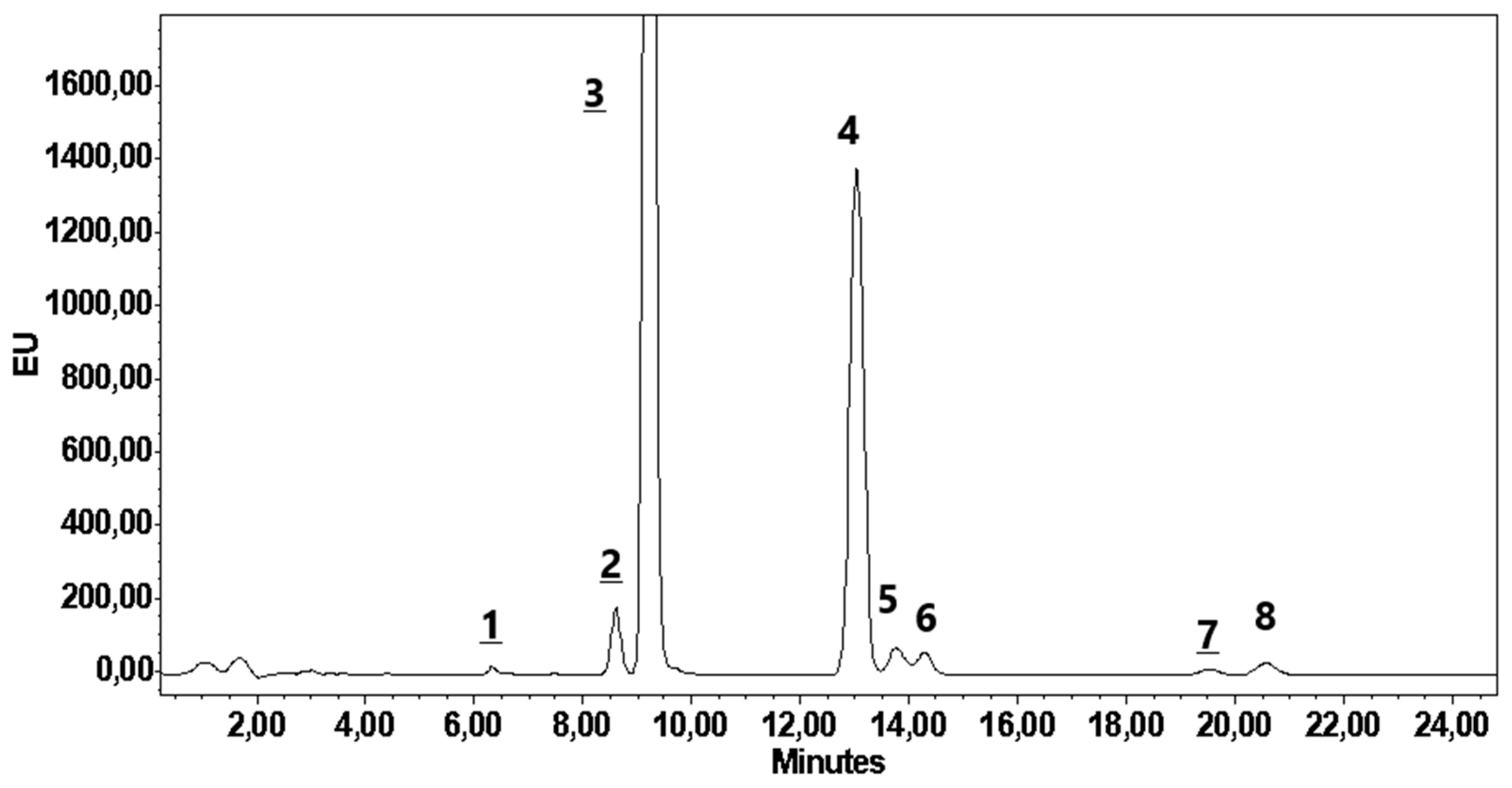

2.4. Analytical Measurements

2.5. Statistical Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

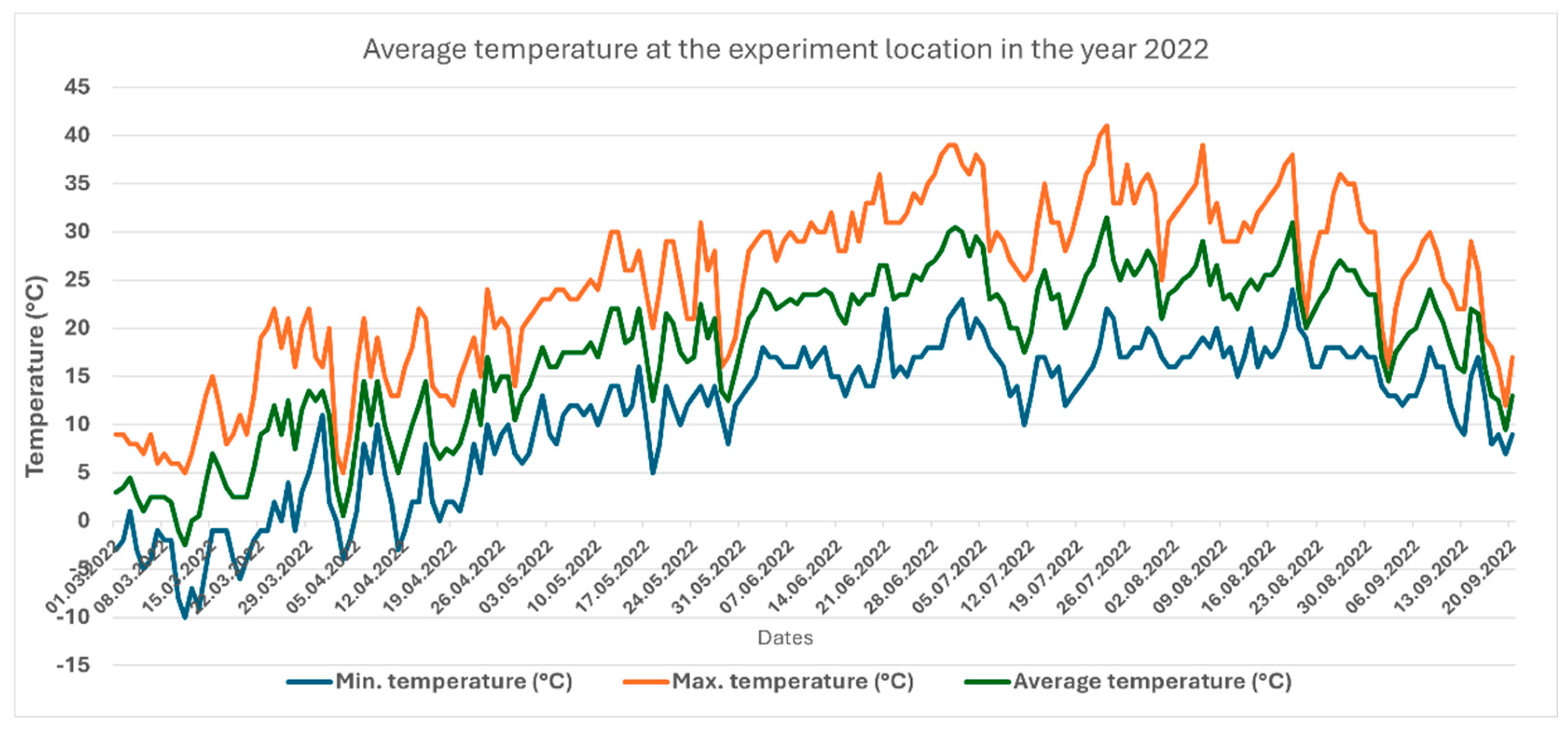

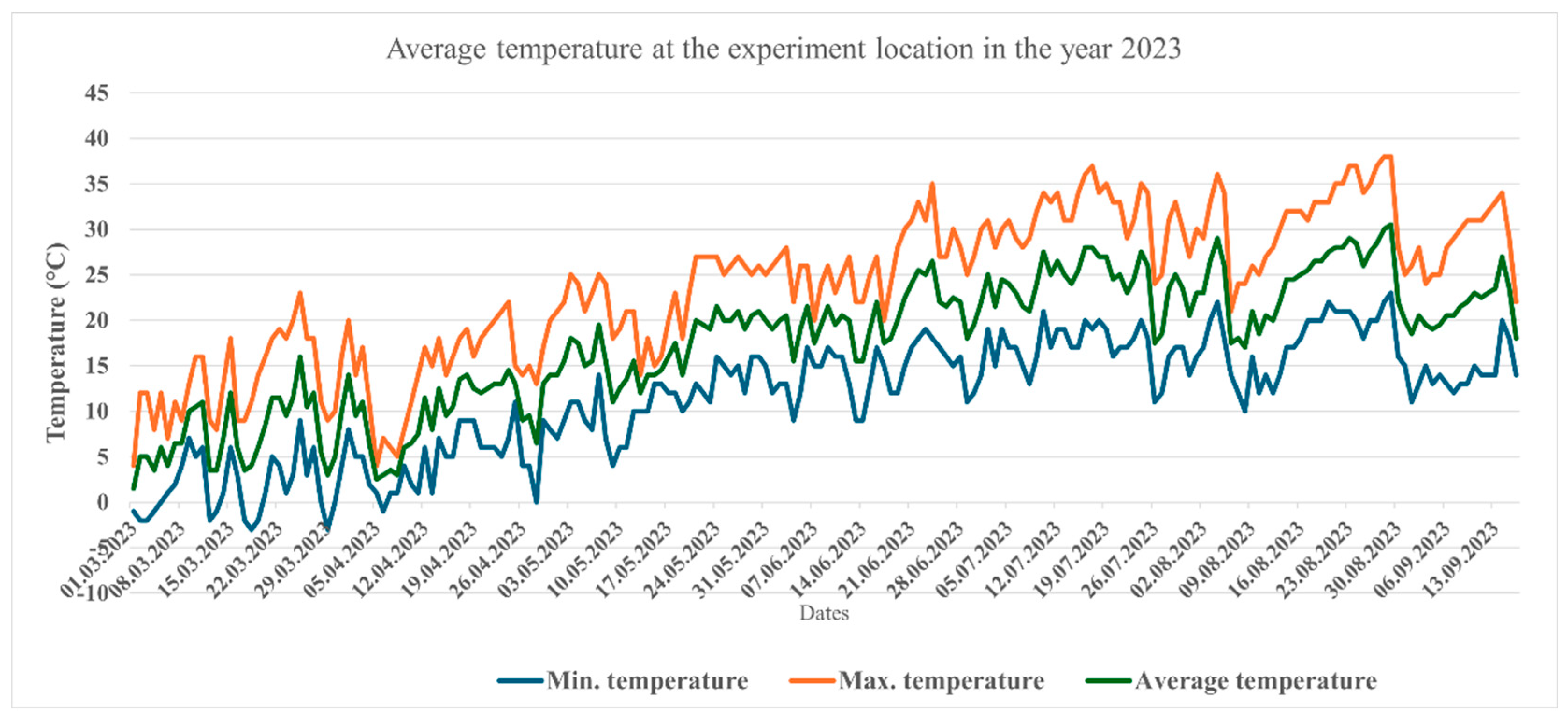

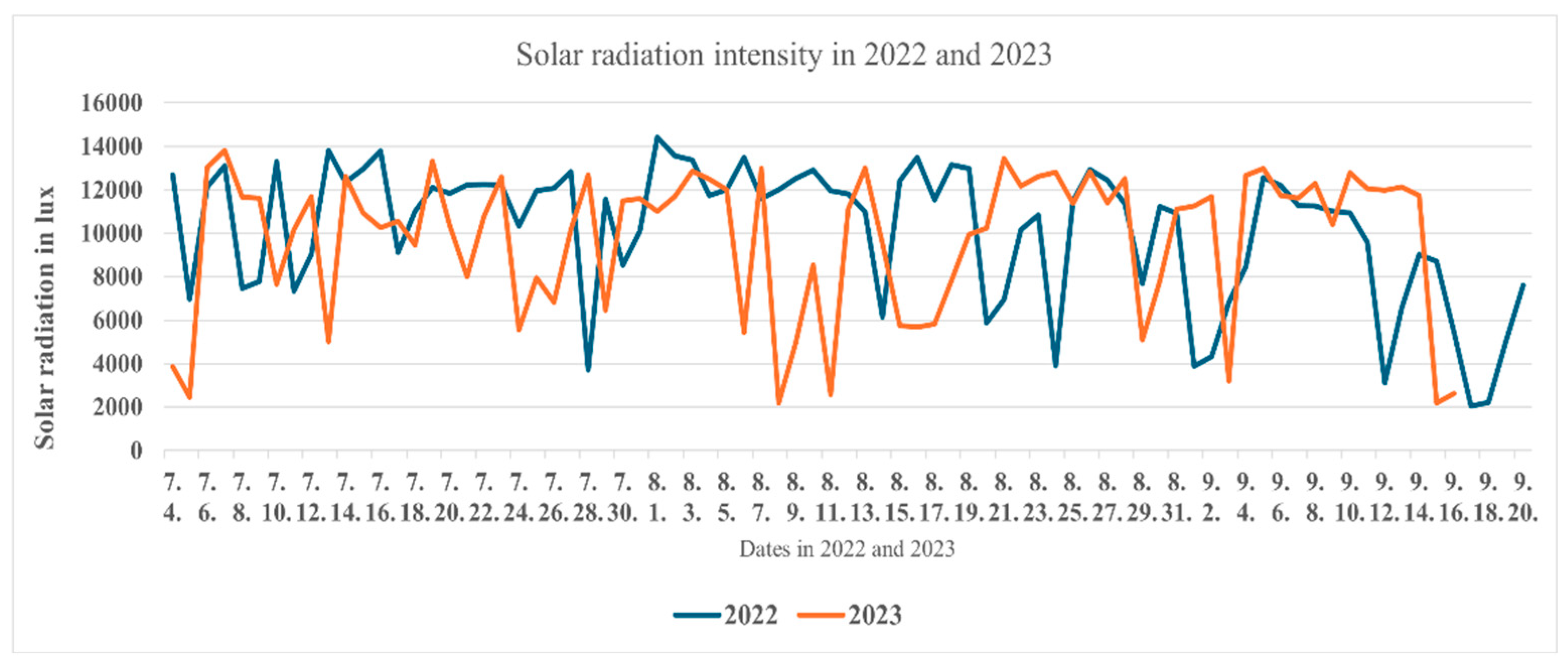

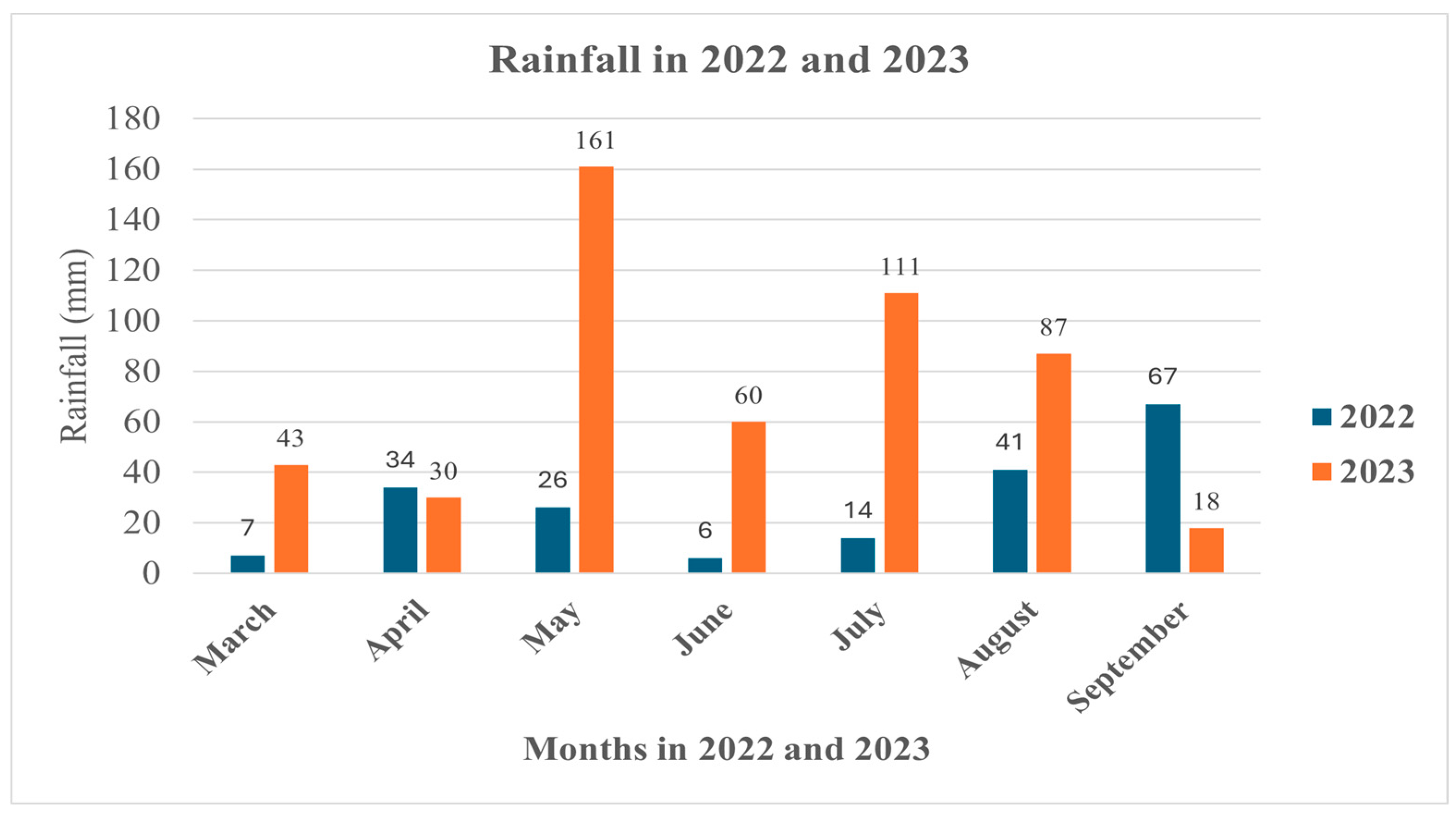

3.1. Temperature and Precipitation in the Two Years Under Study

3.2. Properties of Pepper Fruits Yield

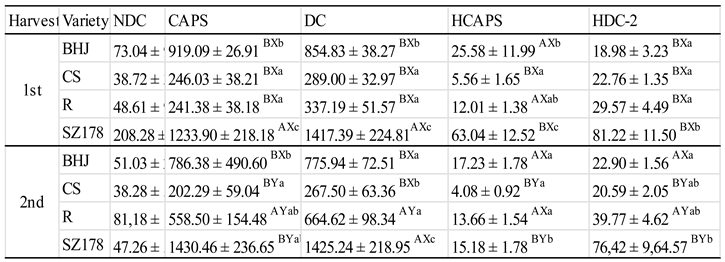

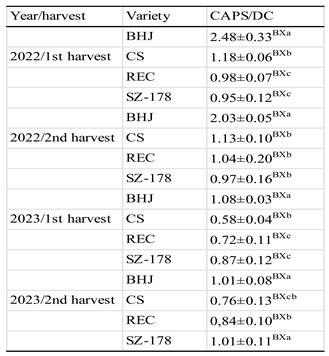

3.3. Impact of Climate Conditions on Capsaicinoids

3.4. Content and Response of Vitamins C

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BHJ | Bhut jolokia variety |

| CS | Cserkő variety |

| REK | Rekord variety |

| SZ178 | Szegedi178 variety |

| RWI | Recommended Dietary Intake |

References

- Dludla, P.V.; Ilenia Cirilli, I.; Marcheggiani, F.; Silvestri, S.; Orlando, P.; Muvhulawa, N.; Meltdown, M.T.; Nkambule, B.B.; Mazibuko-Mbeje, S.E.; Nokulunga Hlengwa, N.; Hanser, S.; Duduzile Ndwandwe, D.; Jeanine, L.; Marnewick, J.L.; Albertus, K.; Basson, A.K.; Luca Tiano, L. Bioactive Properties, Bioavailability Profiles, and Clinical Evidence of the Potential Benefits of Black Pepper (Piper nigrum) and Red Pepper (Capsicum annum) against Diverse Metabolic Complications. Molecules 2023, 28, 6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Pérez, T.; Gómez-García, M.D.R.; Valverde, M.E.; Paredes-López, O. Capsicum annuum (hot pepper): An ancient Latin-American crop with outstanding bioactive compounds and nutraceutical potential. A review. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Safe. 2020, 19, 2972–2993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá Mendes, N.; de Andrade Gonçalves, É.C.B. The role of bioactive components found in peppers. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 99, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Escogido, M.L.; Gonzalez-Mondragon, E.G.; Vazquez-Tzompantzi, E. Chemical and Pharmacological Aspects of Capsaicin. Molecules 2011, 16, 1253–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.S.; Chen, P.N.; Hsieh, Y.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Chu, S.C. Capsaicin protects endothelial cells and macrophage against oxidized low-density lipoproteininduced injury by direct antioxidant action. Chem-Biol. Interact. 2015, 228, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.S.; Kawada, T.; Kim, B.S.; Han, I.S.; Choe, S.Y.; Kurata, T.; Yu, R. Capsaicin exhibits anti-inflammatory property by inhibiting IkB-a degradation in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages. Cell. Signal. 2003, 15, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.H.; Lu, W.C.; Wang, C.W.; Chan, Y.C.; Chen, M.K. Capsaicin induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human KB cancer cells. BMC Complem. Altern. M. 2013, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meral, O.; Alpay, M.; Kismali, G.; Kosova, F.; Cakir, D.U.; Pekcan, M.; Yigit, S.; Sel, T. Capsaicin inhibits cell proliferation by cytochrome c release in gastric cancer cells. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 6485–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, L.; Li, F.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, X. Synthesis of amide derivatives containing capsaicin and their antioxidant and antibacterial activities. J. Food Bioch. 2019, 43, e13061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Choi, M.A.; Kim, B.S.; Han, I.S.; Kurata, T.; Yu, R. Capsaicin protects against ethanol-induced oxidative injury in the gastric mucosa of rats. Life Sci. 2000, 67, 3087–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.R.; Shin, M.K.; Yoon, D.J.; Kim, A.R.; Yu, R.; Park, N.H.; Han, I.S. Topical application of capsaicin reduces visceral adipose fat by affecting adipokine levels in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Obesity 2013, 21, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Samydai, A.; Aburjai, T.; Alshaer, W.; Azzam, H.; Al-Mamoori, F. Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Capsaicin from Capsicum annum Grown in Jordan. Intern. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2019. 10, 3768–3774. [CrossRef]

- Bode, A.M.; Dong, Z. The two faces of capsaicin. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2809–2814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, J.; Paillard, F.; Turnbull, B.; Trudeau, J.; Stoker, M.; Katz, N.P. Efficacy of Qutenza (capsaicin) 8 % patch for neuropathic pain: A meta-analysis of the Qutenza Clinical Trials Database. Pain 2013, 154, 1632–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orellana-Escobedo, L.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Olivas, G.I.; Ornelas-Paz, J.J.; Sepulveda, D.R. Capsaicinoids content and proximate composition of Mexican chili peppers (Capsicum spp.) cultivated in the State of Chihuahua. CyTA-J. Food 2013, 11, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Jayaprakash, G.K.; Crosby, K.; Yoo, K.S.; Leskovar, D.I.; Jifon, J.; Patil, B.S. Ascorbic acid, capsaicinoid, and flavonoid aglycone concentrations as a function of fruit maturity stage in greenhouse-grown peppers. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2014, 33, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.K.; Singh, V.; Upadhyay, G.; Pandey, A.K.; Prakash, D. Assessment of phytochemical composition and antioxidant potential in some indigenous chilli genotypes from Northeast India. Food Chem. 2015, 188, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.S.; Daood, H.G.; Agyemang, S.D.; Vinogradov, S.; Palotás, G.; Neményi, A.; Helyes, L.; Pék, Z. Stability of carotenoids, carotenoid esters, tocopherols and capsaicinoids in new chili pepper hybrids during natural and thermal drying. LWT – Food Sci. Techno 2022, 163, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitra, C.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and immune function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekala, C.S.; Saber, M.K.H.; Phan, A.D.T.; Maboko, M.M.; Fotouo, H.; Soundy, P.; Sultanbawa, Y.; Sivakumar, D. Cultivar-specific responses in red sweet peppers grown under shade nets and controlled-temperature plastic tunnel environment on antioxidant constituents at harvest. Food Chem. 2019, 275, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kader, A.A. Preharvest and postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharv. Biol. Technol. 2000, 20, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepa, N.; Kaur, C.; George, B.; Singh, B.; Kapoor, H.C. Antioxidant constituents in some sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) genotypes during maturity. LWT- Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnayfeed, M.H.; Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P.; Alcaraz, F. Content of bio-active compounds in pungent spice paprika as affected by ripening and genotype. J. Sci. Fd Agric. 2001, 81, 1580–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jifon, J.L.; Laster, G.; Stewart, M.; Crosby, C.; Leskovar, D.I. Fertilizer use and functional quality fruits and vegetables. Chapter 9: Fertilizer Use and Human Health. In: Proceedings of the Conference Name, Conference Location. The International Fertilizer Industry Association (IFA) and the International Plant Nutrition Institute (IPNI), 2012, 21-24.

- Helyes, L. A paradicsom termesztése (Tomato cultivation); Mezőgazda Kiadó: Budapest, 2000; pp. 75–76. ISBN 9789630053280. [Google Scholar]

- Daood, H.G.; Halasz, G.; Palotás, G.; Palotás, G.; Bodai, Z.; Helyes, L. HPLC Determination of Capsaicinoids with cross-linked C18 column and buffer-free eluent.). J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2015, 53, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camposeco-Montejo, N.; Flores-Naveda, A.; Ruiz-Torres, N.; Álvarez-Vázquez, P.; Niño-Medina, G.; Xochitl Ruelas-Chacón, X.; Torres-Tapia, M.M.; Rodríguez-Salinas, P.; Villanueva-Coronado, V.; Josué, I.; García-López, G. Agronomic Performance, Capsaicinoids, Polyphenols and Antioxidant Capacity in Genotypes of Habanero Pepper Grown in the Southeast of Coahuila, Mexico. Horticulturae 2021, 7, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, D.; Dungo, P.; Torre, G.; Bignardi, C.; Cavazza, A.; Corradini, C.; Dugo, G. Evaluatioon of carotenoid and capsaicinoid content in powder of red chili peppers during on year of storage. Food Res. Inter. 2014, 65, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripodi, P.; Cardi, T.; Blanchi, G.; Migliori, C.A.; Schiavi, M.; Rotino, G.L.; Scalzo, R.L. Genetic and environmal factors unferlying variation in yield performance and bioactive compound content of hot pepper varieties (Capsicum annuum) cultivated in two contrasing Italian locations. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2018, 244, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usama, M.G.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ismail, M.R.; Abdul Malek, M.; Abdul Latif, M. Capsaicin and dihydrocapsaicin determination in chili pepper genotypes using ultra-fast liquid chromatography. Molecules 2014, 19, 6474–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, M.; Yuksel, E.A.; Agar, G.; Ekinci, M.; Kul, R.; Turan, M.; Yildirin, E. Biosynthesis of capsaicioids in pungent peppers under salinity stress. Physiol. Plantar. 2023, 175, e13889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.; Fiechter, G.; Fritz, E.-M.; Mayer, H.K. Quantitation of capsaicinoids in different chilies from Austria by a novel UHPLC method. Journal of Food Compos. Analy. 2017, 60, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananthan, R.; Subhash, K.; Longvah, T. Capsaicinoids, amino acid and fatty acid profiles in different fruit components of the world hottest Naga king chilli (Capsicum chinense Jacq). Food Chem. 2018, 238, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duah, A.S.; Souza, C.S.; Daood, H.G.; Pék, Z.; Neményi, A.; Helyes, L. Content and response to Ɣ-irradiation before over-ripening of capsaicinoid, carotenoid, and tocopherol in new hybrids of spice chili peppers. LWT–Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 147, 111555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Zamora, A.; Sierra-Campos, E.; Luna-Ortega, J.G.; Pérez-Morales, R.; Ortiz, J.C.; Garcia-Hornández, J.L. Characterization of different Capsicum varieties by evaluation of their capsaicinoids content by high performance liquid chromatography, detection of pungency and effect of high temperature. Molecules 2013, 18, 13471–13486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gao, C.; Ye, Q.; Liu, C.; Wan, H.; Ruan, M.; Zhou, G.; Wang, R.; Li, Z.; Diao, M.; Cheng, Y. The influence of different factors on the metabolism of capsaicinoids in pepper (Capsicum annum L.). Plants 2024, 13, 2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navez, E.R.; de Ávil Silva, L.; Sulpice, R.; Araújo, W.L.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Peres, L.E.P.; Zsögön, A. Capsaicinoids: Pungency beyond Capsicum. Trend in Plant Science 2019, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeeatid, N.; Techawongstien, S.; Suriham, B.; Bosland, P.W.; Techawongstien, S. Light intensity affects capsaicinoids accumulation in hot peppers (Capsicum Chinese Jscq) Cultgivars. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2017, 58, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawarni Saputri, M.; Qory Oktaria, Q.; Alnia Junaidi, A.; Agis Ardiansyah, M.A. The effect of light intensity and sound intensity on the growth of various types of chili in indoor system. J. Pen. Pend. IPA 2023, 8, 6330–6336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurung, T.; Techawongstien, S.; Suriharn, B.; Techawongstien, S. Impact of environments on the accumulation of capsaicinoids in Capsicumm spp. HortScience 2011, 461, 1576–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Chang, Y.Y.; Ni-lun, T. Capsaicin biosynthesis in water stressed hot pepper fruits. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin 2005, 46, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Phimohan, P.; et al. Impact of drought stress on the accumulation of capsaicinoids in Capsicum cultivarswith different initial capsaicinoid levels. HortScience 2012, 47, 1204–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tupoz, A.; Ozdemir, F. Assessment of carotenoids, capsaicinoidsand ascorbic acid composition of some selected pepper cultivars (Capsicum annuum L) grown in Turkey. J. Food Comp. Anal. 2009, 20, 596–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duelund, L.; Mouritsen, O.G. Contents of capsaicinoids in chilies grown in Denmark. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Real, C.; Adalid-Martinez, A.M.; Pires, C.K.; Ribes-Moya, A.M.; Fita, A.; Rodriguez-Burruezo, A. The effect of the varietal, ripening stage, and growing conditions in Capsicum peppers. Plants 2023, 12, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantar, M.B.; Anderson, J.E.; Lucht, S.A.; Mercer, K.; Bernau, V.; Case, K.A.; Le, N.C.; Frederiksen, M.K.; DeKeyser, H.C.; Wong, Z.-Z.; Hastings, J.C.; Baumler, D.J. Vitamin Variation in Capsicum Spp. Provides Opportunities to Improve Nutritional Value of Human Diets. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini-Costa, S.T.; Silva Gomes, I.; Melo, L.A.M.P.; Becker Reifschneider, F.J.; Costa Ribeiro, C.S. Carotenoid and total vitamin C content of peppers from selected Brazilian cultivars. J. of Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 57, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, Z.; Daood, H.G.; Ambrózy, Z.; Helyes, L. Determination of Polyphenols, Capsaicinoids, and Vitamin C in New Hybrids of Chili Peppers. J. Analyt. Meth. Chem. 2015, 5, 102125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuni, W.; Ana-Rosa, B.; Enny, S.; Raoul, B.J.; Arnaud, B.G. Secondary metabolites of Capsicum species and their importance in the human diet. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, T.L.; Afolayan, A.J. The suitability of chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) for alleviating human micronutrient dietary deficiencies: A review. Food Sci Nutr. 2018, 6, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duah, A.S.; Souza, S.C.; Nagy, Z.; Pék, Z.; Neményi, A.; Daood, H.G.; Szergej Vinogradov, S.; Helyes, L. Effect of Water Supply on Physiological Response and Phytonutrient Composition of Chili Peppers. Water 2021, 13, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, S.; Bandara, D.C. Effects of Soil Moisture Stress at Different Growth Stages on Vitamin C, Capsaicin and P-Carotene Contents of Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) Fruits and their Impact on Yield. Tropical Agricultural Research 2000, 12, 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Selahle, K.M.; Sivakumar, D.; Jifon, J.; Soundy, P. Postharvest response of red and yellow sweet peppers grown under photo-selective nets. Food Chem. 2015, 173, 951–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Variety | Number of fruits/plants | weight (g/fruit) Yield kg/m2 |

|

| 2022 | Bhut jolokia | 18 | 8,7 | 0.579 ± 0.19 AXa |

| 2022 | Cserkó | 24 | 32,3 | 2.86 ± 0.59 AXb |

| 2022 | Szegedi 178 | 17 | 19,8 | 1.24 ± 0.27 AXc |

| 2022 | Rekord | 15 | 22 | 1.21 ± 0.14 AXc |

| 2023 | Bhut jolokia | 22 | 9 | 0.73 ± 0.11AXa |

| 2023 | Cserkó | 21 | 28,2 | 2.19 ± 0.39 AXd |

| 2023 | Szegedi 178 | 15 | 19,1 | 1.06 ± 0.21 AXc |

| 2023 | Rekord | 13 | 15,8 | 0.75 ± 0.12 BXa |

| Harvest | Variety | N DC | CAPS | DC | HCAPS | HDC-2 |

| 1st | BHJ | 36.11 ± 5.36 AXa | 1586.36 ± 123.35 AXc | 640.13 ± 85.04 AXa | 35.04 ± 4.86 AXb | 5.27 ± 0.52 AXa |

| CS | 246.31 ± 25.12 AXd | 1339.94 ± 73.36 AXbc | 1133.67 ± 83.22 AXb | 9.87 ± 0.90 AXa | 92.25 ± 6.84 AXd | |

| R | 82.39 ± 3.50 AXb | 514.24 ± 38.25 AXa | 522.76 ± 26.40 AXc | 10.37 ± 0.81 AXa | 29.41 ± 1.26 AXb | |

| SZ178 | 195.02 ± 22.33 AXc | 1200.74 ± 124.39 AXb | 1263.53 ± 123.30 AXb | 30.33 ± 4.12 AXb | 65.38 ± 6.30 AXc | |

| 2nd | BHJ | 37.88 ± 1.10 AXa | 1734.01 ± 44.41 AXc | 646.98 ± 7.70 AXa | 10.05 ± 1.08 AYa | 10.16 ± 0.37 BXa |

| CS | 268.84 ± 16.28 AXc | 1319.94 ± 145.89 AXb | 1171.11 ± 103.56 AXb | 8.28 ± 0.70 AYa | 104.98 ± 6.78AXd | |

| R | 129.41 ± 21.22 AXb | 771.99 ± 147.49 AXab | 744.30 ± 125.36 AXab | 14.15 ± 2.10 AXa | 43.10 ± 5.67 BYb | |

| SZ178 | 239.06 ± 32.32 AXc | 1401.93 ± 132.62 AXb | 1448.39 ± 161.53 AXc | 37.91 ± 5.04 AXb | 81.01 ± 10.60 AXc |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).