Submitted:

14 August 2025

Posted:

15 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals Used in the Determination

2.2. Cultivation of Tomato

2.3. Thermal Extraction of Juice

2.4. Analysis of Bioactive Compounds

2.4.1. Extraction of Carotenoids and Tocopherols

2.4.2. Extraction of Vitamin C

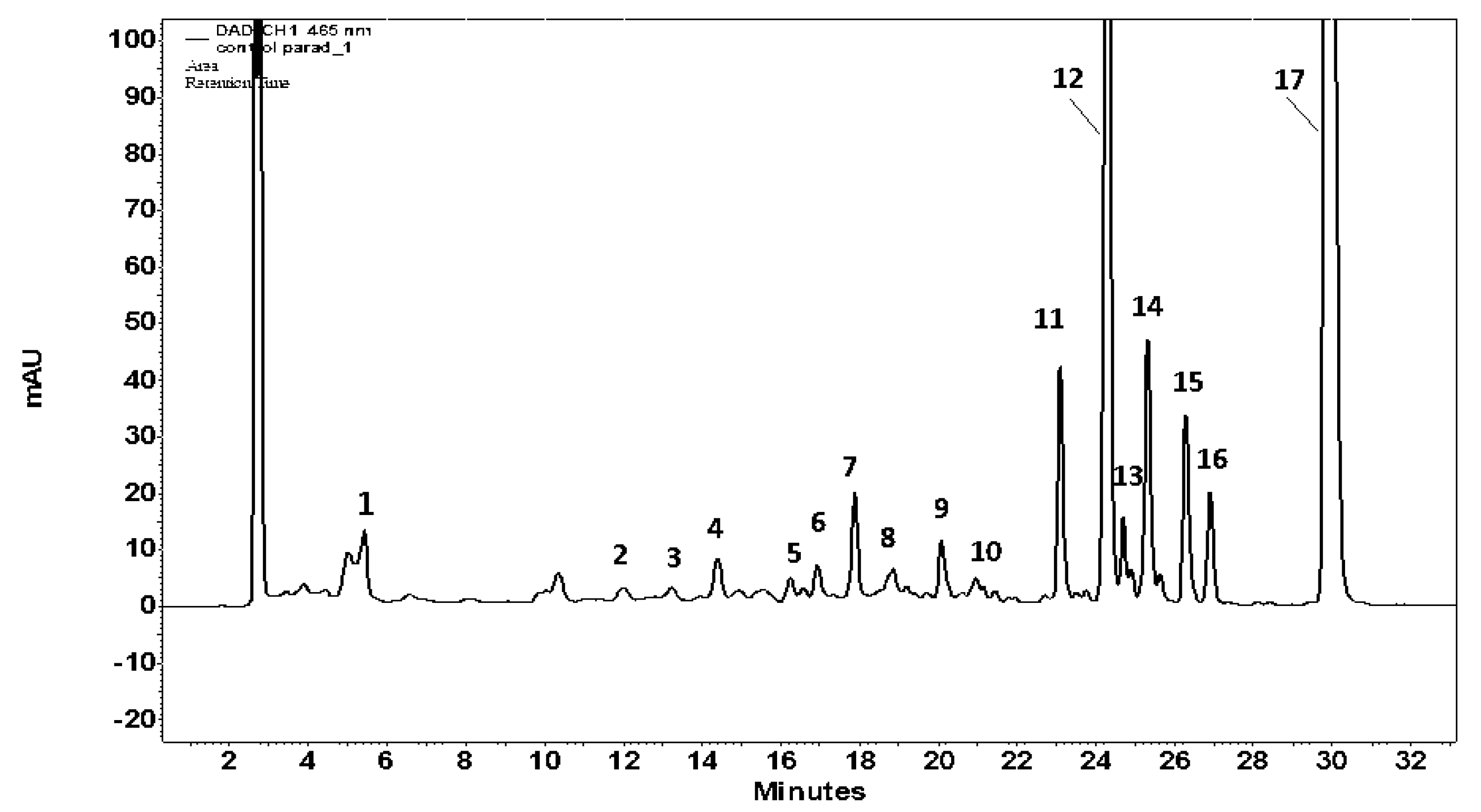

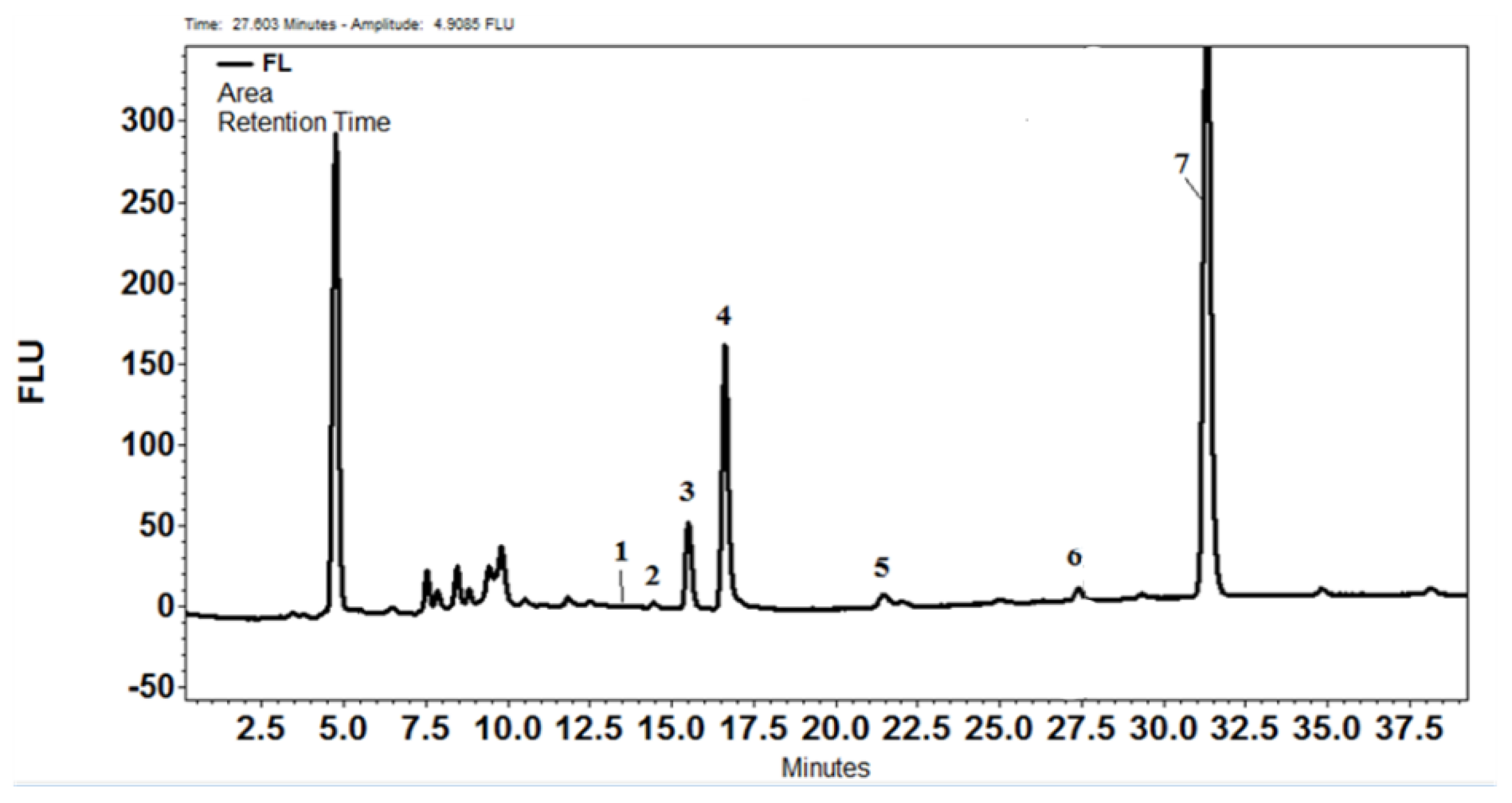

2.4.3. HPLC Determinations

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

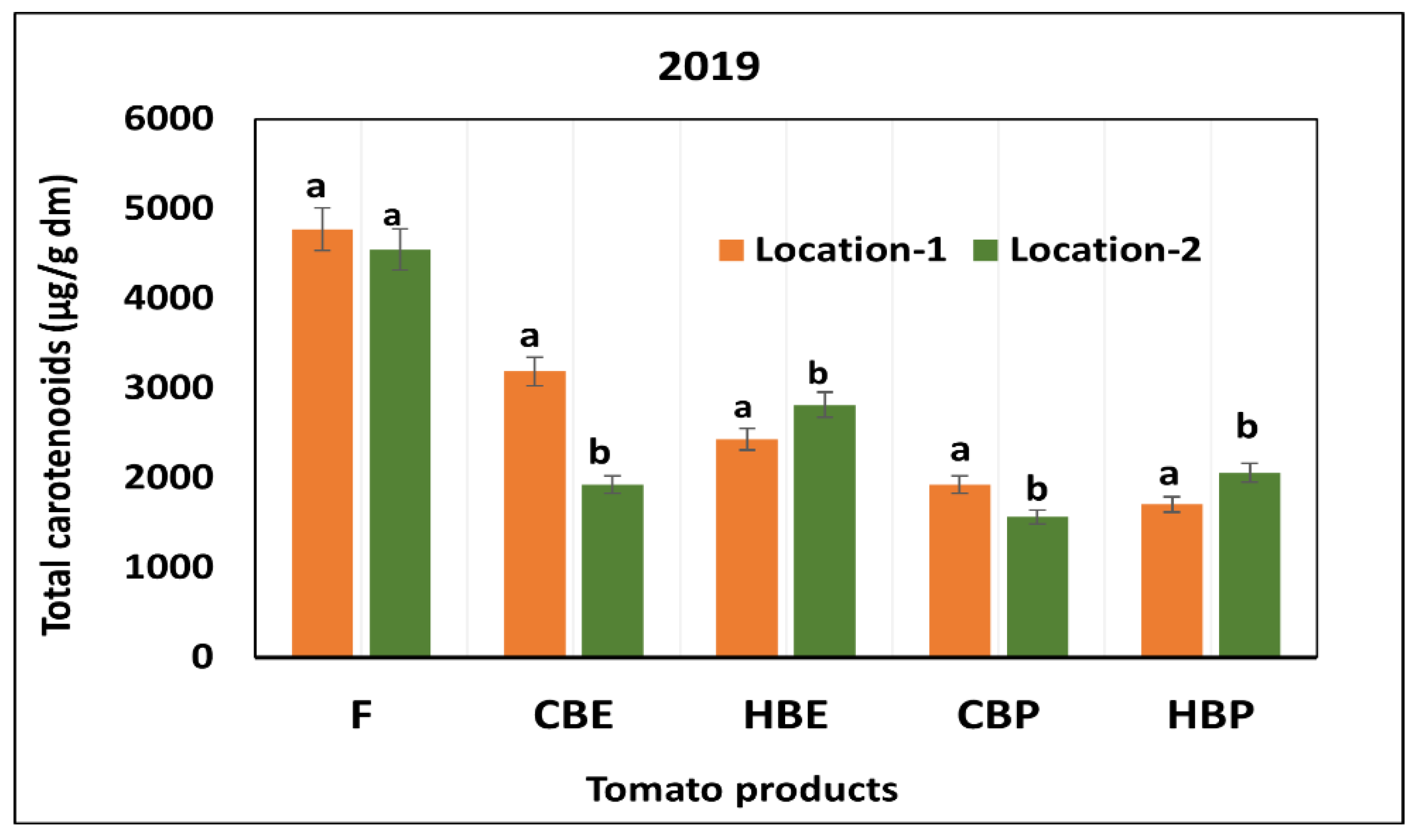

3.1. Content and Stability of Carotenoids

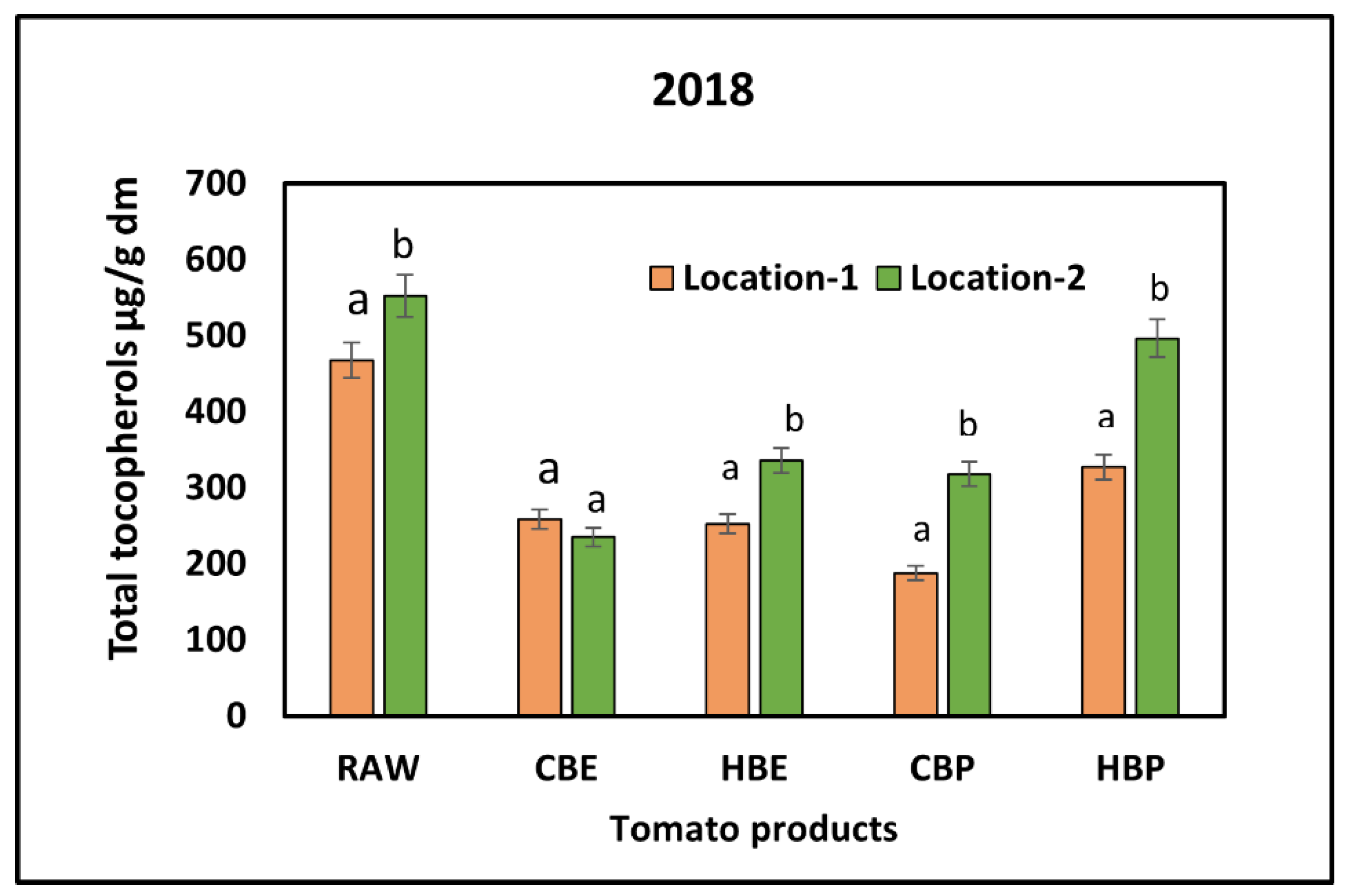

3.2. Response of Tocopherols

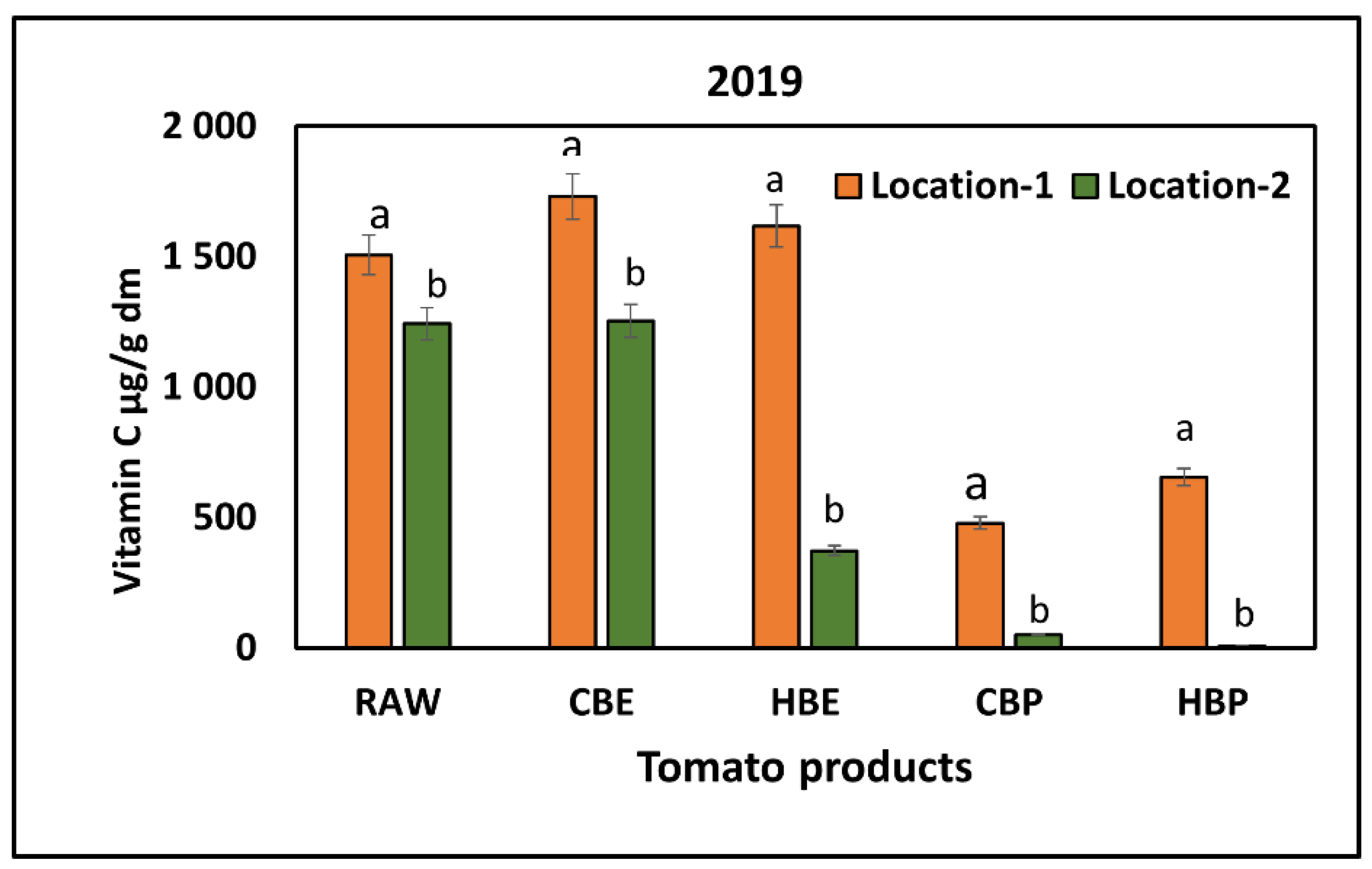

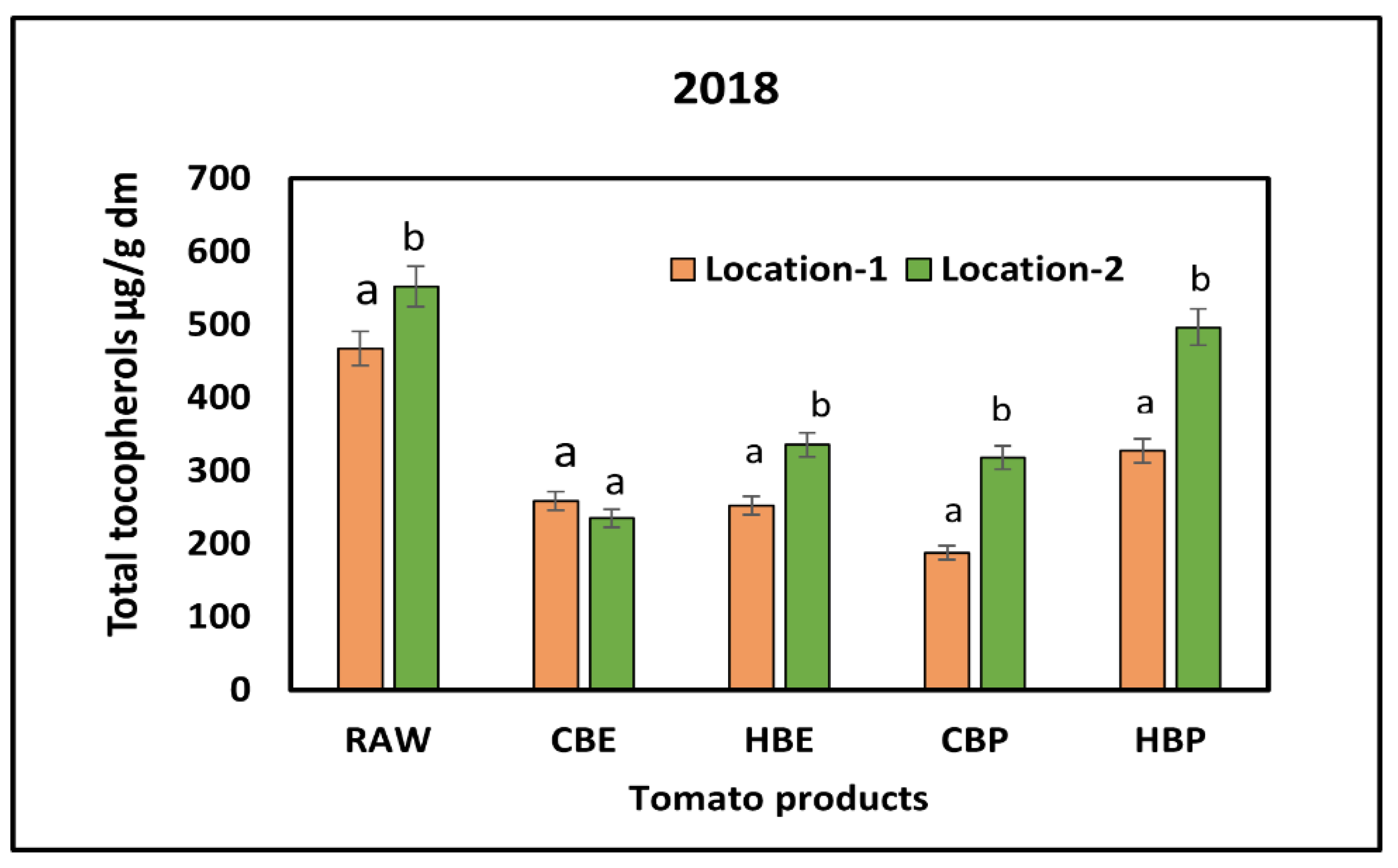

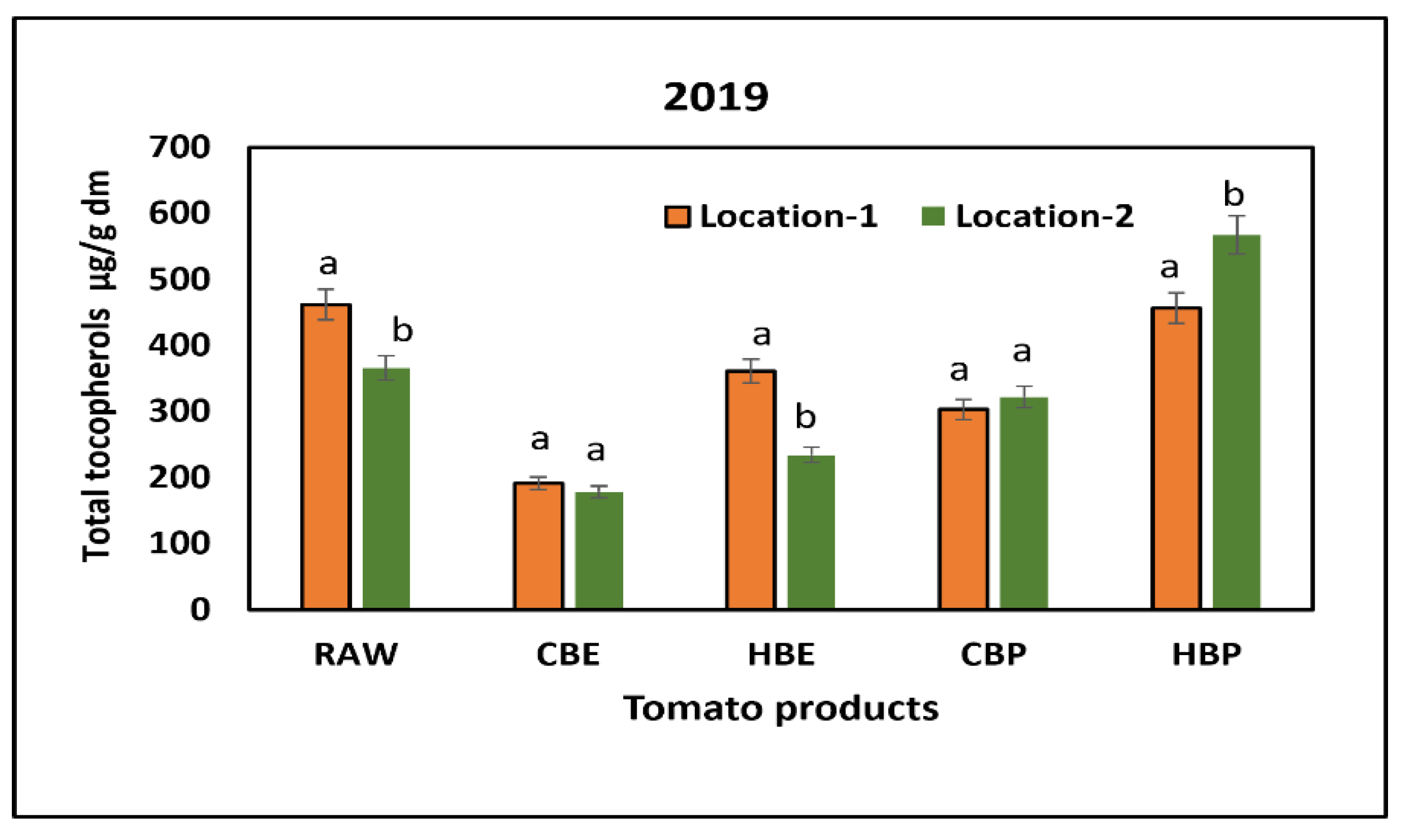

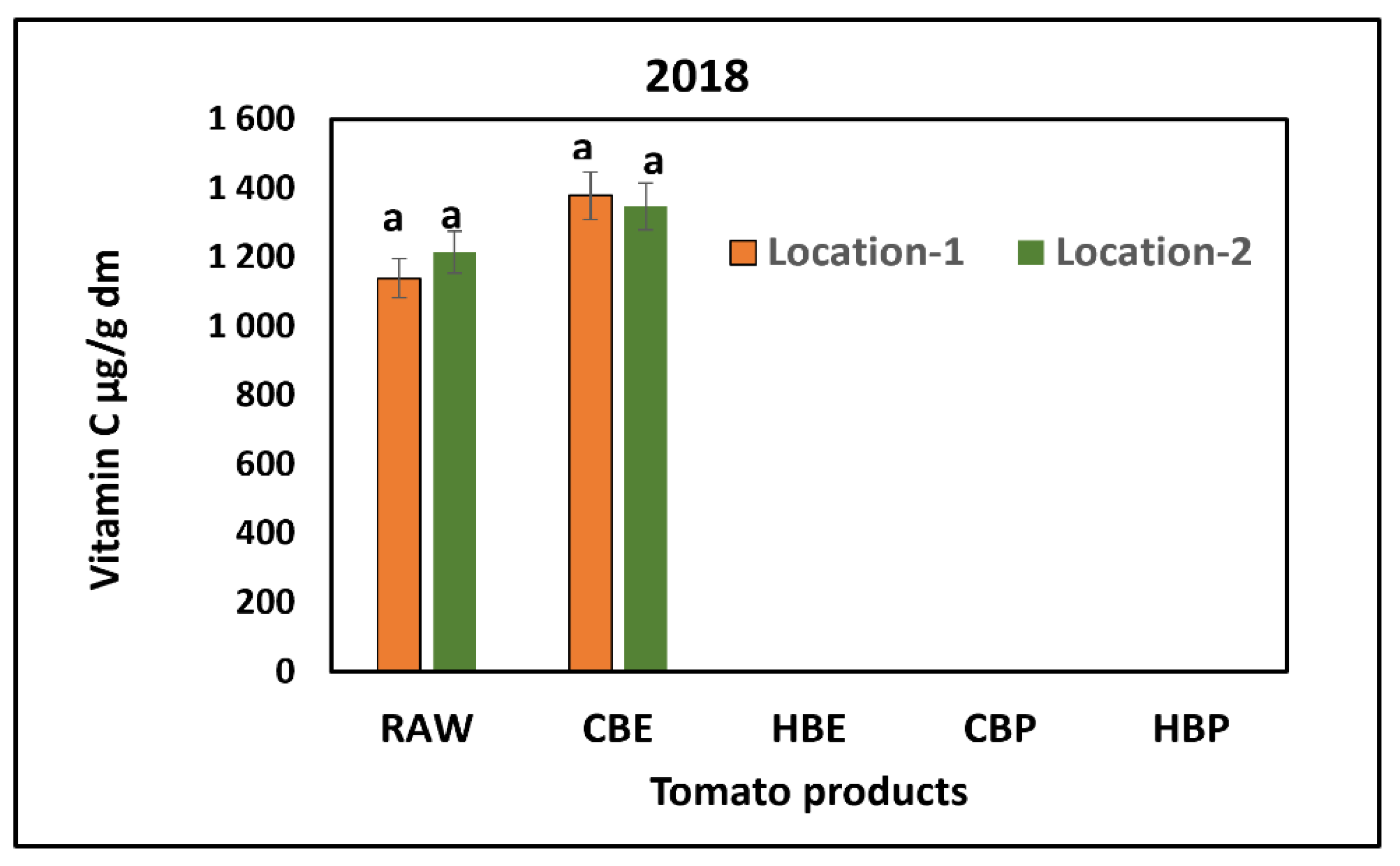

3.2. Response of Vitamin C

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WS | Water supply |

| CBE | Cold-Break Extraction |

| HBE | Hot-Break Extraction |

| α-Toc | alpha-tocopherol |

| α-TocHQ | alpha tocopherol hydroquinone |

| α-TocES | alpha tocopherol ester |

References

- Giovannucci, E.T. Tomatoes, Tomato-Based Products, Lycopene, and Cancer: Review of the Epidemiologic Literature. J. Natl. Canc. Inst. 1999, 91, No. 4, February 17.

- Gammone, M. A.; Riccioni, G.; D’Orazio, N. Carotenoids: potential allies of cardiovascular health? Food Nutr. Res. 2015, 59: 26762 - 26772.

- Rao, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol. Res. 2007, 55, 207-216.

- George, S.A.; Brat, P.; Alter, P.; Amiot, M. J. Rapid Determination of Polyphenols and Vitamin C in Plant-Derived Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1370-1373.

- Moreno, S.; Scheyer, T.; Romano, C. S.; Vojnov, A.’N.A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of rosemary extracts linked to their polyphenol composition Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 223–231.

- Lenucci, M.S.; Cadinu, D.; Taurino, M.; Piro, G.; Dalessandro, G. Antioxidant composition in cherry and high-pigment tomato cultivars. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2606-2613.

- Ilahy, R.; Hdider, C.; Lenucci, M.S.; Tlili, I.; Dalessandro, G. Antioxidant activity and bioactive compound changes during fruit ripening of high-lycopene tomato cultivars. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 588-595.

- Meulebroek L.V.; Vanhaecke L.; De Swaef T.; Steppe K.; De Brabander H. U-HPLC-MS/MS to quantify liposoluble antioxidants in red-ripe tomatoes, grown under different stress levels. J. Agric. Food Chem, 2012, 60, 566-573.

- Krebbers, B.; Master, A.M.; Hoogerwerf, S.W. Combined high-pressure and thermal treatments for processing of tomato puree: evaluation of microbial inactivation and quality parameters. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2003, 4, 377-385.

- Goodman C.L.; Fawcett S.; Barringer S.A. Flavour, viscosity, and color analyses of hot and cold break tomato juices. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, No.1.

- Capanoglu, E.; Beekwilder, J.; Boyacioglu, D.; Hall, R.; de Vos, R. Changes in antioxidant s and metabolite profile during the production of tomato paste J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 964-973.

- Krebbers, B.; Master, A.M.; Hoogerwerf, S.W. Combined high-pressure and thermal treatments for processing of tomato puree: evaluation of microbial inactivation and quality parameters. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2003, 4, 377-385.

- Illés, G.; Fonyó T.; Pásztor, L.; Bakacsi ZS.; Laborczi, A. Agroclimate 2 project of compilation of digital soil-type map of Hungary, Erdészettudomány Közlemények (Forestry Science Communications). 2016, 6, 17-24.

- Nemeskéri, E.; Horváth, K.Z, ; Andryei,B.; Ilahy, R.; Takács,S.; Neményi, A.; Pék, Z.; Helyes, L. Impact of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria inoculation on the physiological response and productivity traits of field-grown tomatoes in Hungary. Horticulturae 2022,8, no. 641.

- Bulgan, A.; Horváth, K.Z.; Duah, S.A.; Takács, S.; ÉgeI, M.; Szuvandzsiev, P.; Neményi, A. Use of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) in the mitigation of water deficiency of tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum L.). J. Centr. Eur. Agric. 2021, 22, 167-177.

- Kruk, J.; Szymanska, R.; Krupinska, K. Tocopherol quinone content of green algae and higher plants revised by a new highly sensitive fluorescence detection method using HPLC–Effects of high light stress and senescence. J. Plant Physiol. 2008, 165, 1238–1247. [CrossRef]

- Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P.A.; Dakar, M.; Hajdú, F. Ion-pair chromatography and photo mode-array detection of vitamin C and organic acids. J. Chromatogr.. Sci. 1994, 32, 481-487.

- Daood, H. G.; Ráth, Sz.; Palotás, G.; Halász, G.; Hamow, K.; Helyes L. Efficient HPLC separation on a core C30 column with MS2 characterization of isomers, derivatives, and unusual carotenoids from tomato products. J.Chromatogr. Sci., 60, 336-347.

- Daood, H.G.; Biacs. P.A. Simultenous determination of Sudan dyes and carotenoids in red pepper and tomato products by HPLC. J. Choromatogr. Sci.2005, 43, 461-465.

- Hsu, K.C.; Tan, F. J.; Chi, H.J. Evaluation of microbial inactivation and physiochemical properties of pressurized tomato juice during refrigerated storage. LWT. 2008, 41, 367-375.

- Schwartz, K.; Bertelsen, G.; Nissen, L.R.; gardner, P.T.; Heinonen, M.I.; Hopia, A.; Huynh-Ba, T.; Lambelet, P.; McPhail, D.; Skibsted, L.H.; Tijburg, L. Investigation of plant extracts for the protection of processed foods against lipid oxidation. Comparison of an antioxidant assay based on radical scavenging, lipid oxidation, analysis of the principal antioxidant compounds. Eur. Food Res.Technol. 2001, 212, 1-42.

- Bramely, P.M. Regulation of carotenoid formation during tomato fruit ripening and development. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 2107.2113.

- Deli, J.; Osz, E. Carotenoid 5,6-, 5,8- and 3,6-epoxides. Arkivoc. 2004, 7, 150-168.

- Gama, J. J. T.; Tadiotti A.C.; de Sylos C.M. Comparison of carotenoid content in tomato, tomato pulp, and ketchup by liquid chromatography. Alim. Nutr. ,Araraquara. 2006, 17, 353-358.

- Fanasca, S.; Colla, G.; Maiani G.; Venneria, E.; Rouphael, E.; Y. Azzini, E.; Saccardo, F. Changes in Antioxidant Content of Tomato Fruits in Response to Cultivar and Nutrient Solution Composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 12, 4319–4325.

- Sharma, S.K.; Maguer, M.L Kinetics of lycopene degradation in tomato pulp solids under different processing and storage conditions. Food Res. Int. 1996, 29, 309-315.

- Martinéz-Hernández, G.B.; Boluda-Aguilar, M.; Taboada-Rodréguez, A.; Soto-Jover, S.; Marín-Iniesta, F.; López Gómez, A. Processing, packaging and storage of tomato products: Influence on the lycopene content. Food Eng. Rev. 2016, 8, 52-75.

- Temitope, A.O.; Eloho, A.P.; Olubunmi I. D. lycopene content in tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill): Effect of thermal heat and its health benefits. Fresh Produce. 2009, 3, 40-43.

- Mayeaux, M.; Xu, Z.; King, I.M.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Effect of cooking conditions on the lycopene content in tomatoes. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, 461-464.

- Toor, R.K.; Savage, G.P. Antioxidant activity in different fractions of tomatoes. Food Res. Int. 2005, 38, 487-494.

- Chandra, H.M.; Ramalingam, S. Antioxidant potentials of skin, pulp and seed fractions of commercially important tomato cultivars. Food Sci.Technol. 2011, 20, 15-21.

- Vinha, A. F.; Alves, R. C.; Barreira S.V.P.; Castro A.; Costa, A.S.G.; Olivieira, M.B.P.P. Effect of peel and seed removal on the nutritional value and antioxidant activity of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) fruits. LWT. 2014, 55, 197-202.

- Angaman, D. M.; Renato, M.; Azcón-Bieto, J.; Boronat, A. Oxygene consumption and lipoxygenase in isolated tomato fruit chromoplasts, J. Plant Sci. 2014, 2, 5-8.

- Urbonaviciene, D.; Viskelis, P.; Viskelis, J.; Jankauskiene, J.; Bobinas, C. Lycopene and β-carotene in non-blanched and blanched tomatoes. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2012,10, 142-146.

- Tonucci, L. H; Holden, J. M.; Beecher, G. R.; Khachik, F.; Davis C.S.; Mulokozi, G. Carotenoid content of thermally processed tomato-based food products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1995, 43, 579-586.

- Nascimento, A.A. G.; Vasconcelos, A.G.; Souza, G.; Oliveira, A.; de Souza de Almeida Leite G.J.R.; Pintado, M. Bioavailability, anticancer potential, and chemical data of lycopene: an overview and technological prospect ing.” Antioxidants 2022, 11, no. 360.

- D’Evoli, l.; Lombardi-Boccia, G.; Lucarini, M. Influence of heat treatments on carotenoid content of cherry tomatoes. Foods, 2013, 2, 352-363.

- Seybold, C.; Fröhlich, K.; Bitch, R.; Otto, K.; Böhm, V. Change in content of carotenoids and vitamin E during tomato processing. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 7005-7010.

- Lin, C.H.; Chen, B.H. Stability of carotenoids in tomato juice during storage. Food Chem. 2005, 90, 837-846.

- Gharbi, S.; Renda, G.; La Barbera, L.; Amri, M.; Messina, C.M.; Santulli, A. Tunisian tomato by-products, as a potential source of natural bioactive compounds. Nat. Prod. Res. 2017, 31, 626-631.

- Quadrana, L; Almeida, J.; Otalza, S.N.; Duffy, T.; Corredo da Silva, J.V.; de Godoy F.; Asis, F.; Bermúdez, L.; Fernie, A.R.; Carrari, F.; Rossi, M. Transcriptional regulation of tocopherol biosynthesis in tomato. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013., 81, 309-325.

- Abushita, A.A.; Daood, H.G.; Biacs, P. Change in carotenoids and antioxidant vitamin in tomato as a function of varietal and technological factors. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 2075-2081.

- Chanforan, C.; Loonis, M.; Mora, N.; Caris-Veyrat, C.; Dufour, C. The impact of industrial processing on health-beneficial tomato microconstituents. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 1786-1795.

- Yahia, E.M.; Contreras-Padilia, M.; Gonzalez-Aguilar, G. The ascorbic acid content in relation to ascorbic acid oxidase activity and polyamine content in tomato and bell pepper fruits during development, maturation, and senescence. LWT, 2001, 34, 452-457.

- Abdelgawad, K.F.; El-Mogy, M.M.; Mohamed, M.I.A.; Garchery, C.; Stevens, R. Increasing ascorbic acid and salinity tolerance of cherry tomato plants by suppressed expression of the ascorbate oxidase gene. Agronomy, 2019, 9, 51-64.

- Munyaka, A.W.; Makule, E.E.; Oey, I.; Loey, A.V.; Hendrickx, M. Thermal stability of L-ascorbic acid and ascorbic acid oxidase in Broccoli. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C336-C340.

- Anthon, G. E.; Sekine, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Barrett, D.M. Thermal inactivation of pectin methylesterase, polygalacturonase and peroxidise in tomato juice. J. Agric. Food Chem, 2002, 50, 6153-6159.

- Davey, M. W.; Montagu, M.V; Inzé, D.; Sanmartin, M.; Kanellis, A.; Smirnoff, N.; Benzie, I. J. J.; Strain, J., Favell, D., Fletcher, J. Plant L-ascorbic acid: chemistry, function, metabolism, bioavailability, and effects of processing. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2000, 80, 825-860.

- Stevens, R.; Page, D.; Gouble, B.; Garchery, C.; Zamir, D.; Causs, M. Tomato fruit ascorbic acid content is liked with monodehydroascorbate reductase activity and tolerance to chilling stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2008, 31, 1086-1096.

- Melliduo, I.; Keulemans, J.; Kanellis, A.K.; Davey, M.W. Regulation of fruit ascorbic acid concentrations during ripening in high and low vitamin C tomato cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2012, 12, 239-252.

- Andrews, J.; Adams, S.R.; Burton, K.S.; Evered, C.E. Subcellular localization of peroxidase in tomato fruit skin and the possible implications of the regulation of fruit growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1853-1691.

- Morohashi, Y. Peroxidise activity develops in the micropylar endosperm of tomato seeds prior to radical protrusion. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1643-1650.

- Massot, C.; Bancel, D.; Lauri, F.L.; Truffault, V.; Baldet, P.; Stevens, R., Gautier, H. High-temperature inhibits recycling and light stimulation of the ascorbate pool in tomato despite increased expression of biosynthesis genes. PloS ONE, 2013, 8, e84474.

- Jagadeesh, S.L.; Charles, M.T.; Gariepy, Y.; Goyette, B.; Raghavan, G.S.V.; Vigneault, C. Influence of postharvest UV-C hormesis on the bioactive components of tomato during post-treatment handling. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2011, 4, 1463-1472.

| Regular Meteorological parameters | Location-1 | Location-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Average temperature (°C) during the growing seasons | 21.6 | 21.3 | 22.3 | 22.5 |

| Average temperature (°C) 3 weeks before harvest | 23.8 | 23.6 | 25.5 | 24.6 |

| Mminimum temperature (°C) 3 weeks before harvest | 17.1 | 16.9 | 19.4 | 17.3 |

| Days in excess at 30°C during the growing season | 28 | 44 | 34 | 57 |

| Days in excess at 30°C 3 weeks before harvest | 18 | 13 | 21 | 15 |

| Precipitation (mm) during the growing seasons | 304.6 | 278.3 | 126.9 | 256.5 |

| Precipitation (mm) 3 weeks before harvest | 55.9 | 23.0 | 4.5 | 5.9 |

| Carotenoids | Tomato products | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | CBE | HBE | CBP | HBP | |

| Location-1 | |||||

| Lycopene | 4018.3±131a | 2584± 65a | 1887±67a | 829±37a | 913 ± 120a |

| 9Z-lycopene | 13.5 ± 2.5a | 17.3 ± 1.3a | 16.4 ± 2.4a | 16.5 ± 4.2a | 3.5 ± 0.6a |

| Ɣ-carotene | 14.6 ± 0,8a | 12.2 ± 1.9a | 8.0 ± 0.8a | 5.2 ± 0.6a | 5.2 ± 0.6a |

| 13Z-lycopene | 31.2 ± 3.4a | 165.7 ± 5.0a | 113.8 ± 6.3 | 192.8 ± 10.8a | 33.5 ± 5.7 |

| β-carotene | 52.1 ± 5.3a | 41.6 ± 2.2a | 32.9 ± 4.9 | 60.2 ± 2.9a | 53.2 ± 2.4a |

| Lycoxanthin | 56.2 ± 6.7a | 74.6 ± 3.9a | 53.9 ± 4.0a | 19.0 ± 1.1a | 20.3 ± 2.4a |

| Z-dimethoxy lycopene | 21.3 ± 2.0a | 27.5 ± 3,1a | 19.8 ± 2.1a | 14.3 ± 0.4a | 7.9 ± 0.6a |

| Z- Lycopene diepoxy | 7.8 ± 0,6a | 9.8 ± 2.4a | 6.8 ± 1.1a | 4.4 ± 0.2a | 2.9 ± 0.1a |

| Z-β-carotene epoxide | 40.6 ± 4.9a | 65.5 ± 6,0a | 44.3 ± 2.3a | 24.9 ± 0.6a | 16.7 ± 1.3a |

| Z-diepoxy β-carotene | 11.7 ± 1.3a | 20.2 ± 2.2a | 14.4 ± 0.9a | 8.9 ± 0.1a | 5.7 ± 0.5a |

| Z-diepoxy β-carotene | 12.7 ± 1.6a | 18.1 ± 0,3a | 12.6 ± 0.7a | 8.3 ± 0.1a | 5.1 ± 0.3a |

| Lutein | 16.2 ± 1.6a | 15.1 ± 0.7a | 13.6 ± 0.1a | 14.3 ± 1.1a | 14.3 ± 0.7a |

| Phytoene | 81.4 ± 11.4a | 110.5 ± 17.7a | 93.0 ± 3.3a | 48.7 ± 2.3a | 40.5 ± 2.1a |

| OH-phytoene | 16.0 ± 2.6a | 16.9 ± 3.1a | 11.6 ± 1.9a | 6.7 ± 0.8a | 4.7 ± 0.3a |

| Phytofluene | 46.6 ± 1.8a | 47.8 ± 4.5a | 43.8 ± 8,7a | 27.3 ± 4.7a | 22.5 ± 4.6a |

| OH-phytofluene | 4,1 ± 1.3a | 2.2 ± 02a | 2.4 ± 0.1a | 1.7 ± 0.1a | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| Location-2 | |||||

| Lycopene | 3786±142a | 1104 ± 49b | 1543± 63b | 792 ± 39a | 1067±62a |

| 9Z-lycopene | 17.8 ± 1.1a | 7.7 ± 1.2b | 15.1 ± 1.9a | 3.0 ± 0.6b | 4.3 ± 0.5a |

| Ɣ-carotene | 16.7 ± 2.6a | 4.6 ± 0.1b | 8.8± 0.6a | 4.3 ± 0.1b | 5.7 ± 0.3a |

| 13Z-lycopene | 73.5 ± 9.3b | 99.8± 4.3b | 112.7 ± 3.6a | 61.7 ± 5.0b | 62.5 ± 6.4 |

| β-carotene | 61.7 ± 9.9a | 33.3 ± 0.7b | 40.9 ± 1.9a | 40.4 ± 1.9b | 56.8 ± 1.6a |

| Lycoxanthin | 117.7 ± 5.3b | 35.0 ± 0.2b | 48.0 ± 3.4a | 18.8 ± 0.6a | 27.3 ± 1.6b |

| Z-dimethoxy lycopene | 35.2 ± 1.1b | 18.8 ± 1.8b | 19.7 ± 1.7a | 9.4 ± 0.3b | 12.2 ± 0.3b |

| Z- Lycopene diepoxy | 11.9 ± 0.8b | 6.5 ± 1.7a | 7.5 ± 0.2a | 3.7 ± 0.4a | 4.8 ± 0.2b |

| Z-β-carotene epoxide | 68.7 ± 1.9b | 37.6 ± 1.3b | 45.6 ± 2.5a | 18.6 ± 1.0b | 23.4 ± 1.1b |

| Z-diepoxy β-carotene | 71.7 ± 5.7b | 44.3 ± 1.4b | 15.8 ± 1.2a | 22.5 ± 1.1b | 22.5 ± 1.0b |

| Z-diepoxy β-carotene | 75.9 ± 4.7b | 37.5 ± 0.9b | 14.0 ± 0.9a | 19.8± 0.8b | 23.2 ± 1.0b |

| Lutein | 21.0 ± 0.8b | 15.8 ± 0.3a | 21.5 ± 0.7b | 14.1 ± 0.3a | 21.3 ± 0.6b |

| Phytoene | 108.7 ± 2.4b | 88.5 ± 6.0a | 92.0 ± 0.4a | 46.7 ± 2.4a | 57.4 ± 1.5b |

| OH-phytoene | 31.6 ± 6.1b | 16.6 ± 0.7a | 14.4 ± 0.8a | 9.4 ± 1.5b | 9.3 ± 0.2b |

| Phytofluene | 69.1 ± 3.2b | 50.0 ± 0.5a | 54.4 ± 4.8a | 29.8 ± 1.5a | 37.9 ± 1.0b |

| OH-phytofluene | 7.2 ± 1.4b | 2.6 ± 0.4a | 2.3 ± 2.2a | 1.8 ± 0.1a | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| Carotenoids | Tomato Products | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | CBE | HBE | CBP | HBP | |

| Location-1 | |||||

| lycopene | 4165±266a | 2634.±150a | 2423±139a | 151.6±23.2a | 137±4.a |

| 9Z-lycopene | 20.0±2.8a | 23.5±4.4a | 13.2±0.8a | 16.0±0.3a | 8.2±1.1a |

| γ-carotene | 21.1±0.7a | 21.3±1.4a | 13.3±0.6a | 10.4±0.1a | 9.7±1.4 |

| 13Z-lycopene | 93.5±11.5a | 74.3±8.4a | 93.9±14.4a | 270.1±11.1a | 84.9±7.9a |

| β-carotene | 108.0±8.3a | 41.2±10.2a | 55.4±4.4a | 36.8±4.6a | 54.0±7.3a |

| lycoxanthin | 100.2±4.6a | 48.5±0.8a | 70.8±3.6a | 30.4±0.7a | 31.7±2.6a |

| Z- dimethoxy lycopene | 77.3±7.7 | 34.5±2.1a | 60.3±3.6a | 38.5±1.2a | 34.0±3.5a |

| Z-lycopene-diepoxide | 19.4±1.8a | 18.3±3.8a | 15.9±0.2a | 8.9±0.3a | 7.1±0.1a |

| Z-β-carotene epoxide | 149.4±11.0 | 78.7±11.7a | 127.7±6.4a | 77.5±2.0a | 71.2±6.9a |

| Z-β-carotene diepoxide | 46.7±2.9a | 26.6±3.7a | 39.0±2.0a | 23.7±0.6 | 21.1±1.3a |

| Z-β-carotene diepoxide | 37.5±2.6a | 23.7±1.8a | 31.6±1.5a | 19.5±0.3a | 17.0±0.7a |

| lutein | 19.4±0.6a | 19.8±3.7a | 13.6±0.5a | 13.9±0.4a | 14.0±1.3a |

| Phytoene | 151.4±7.1a | 122.0±13.7a | 98.8±4.9a | 67.8±3.0a | 62.4±9.8a |

| OH-phytoene | 36.4±0.9a | 18.2±2.3a | 19.4±1.1a | 13.8±1.2a | 9.8±1.7a |

| Phytofluene | 80.6±4.6a | 63.8±11.7a | 53.8±4.6a | 39.2±1.5a | 37.4±6.1a |

| Location-2 | |||||

| lycopene | 4055±274a | 1453±110b | 2105±76b | 121±39b | 152±5b |

| 9Z-lycopene | 25.7±5.3a | 10.1±0.6b | 14.8±0.5a | 30.4±2.8b | 17.1±0.9b |

| γ-karotin | 20.9±2.3a | 7.3±0.7 | 10.7±0.3b | 7.7±0.6 | 6.6±0.6b |

| 13Z-lycopene | 76.2±5.3a | 107.0±2.7b | 134.1±10.3b | 311.8±17.4b | 236.3±17.8b |

| β-carotene | 65.2±7.3b | 34.2±2.1b | 51.3±2.2a | 33.4±07a | 37.4±5.4b |

| lycoxanthin | 94.8±23.1a | 45.8±4.5a | 69.7±2.7a | 46.0±2.2b | 32.4±4.7a |

| Z- dimethoxy lycopene | 15.7±4.3b | 48.6±3.1b | 61.1±1.5a | 41.0±2.6a | 40.2±1.0b |

| Z-lycopene-diepoxide | 8.8±2.4b | 12.7±0.8b | 15.1±0.2a | 9.9±1.1a | 10.9±0.5b |

| Z-β-carotene epoxide | 30.0±8.5b | 102.1±6.5b | 128.3±2.8a | 81.7±3.5a | 87.8±1.3b |

| Z-β-carotene diepoxide | 9.8±2.6b | 31.1±2.3a | 39.2±1.0a | 25.6±0.7a | 28.8±1.3 |

| Z-β-carotene diepoxide | 8.0±2.4b | 25.9±1.5b | 31.4±0.8a | 19.8±0.5a | 23.8±0.4b |

| lutein | 27.2±2.4b | 9.8±1.5b | 12.8±0.9a | 12.2±1.1a | 14.4±1.2a |

| Phytoene | 122.6±13.2b | 92.0±4.0b | 119.9±1.4b | 113.7±2.6b | 95.3±11.2b |

| OH-phytoene | 13.7±5.3b | 16.7±1.6a | 12.6±0.4b | 15.6±08b | 9.6±1.2a |

| Phytofluene | 52.6±15.7b | 47.1±2.5a | 60.3±1.9a | 57.0±0.8b | 47.2±5.3b |

| Tocopherols | Tomato Products | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw | CBE | HBE | CBP | HBP | ||

| Location-1 (2018) | ||||||

| α-tocopherol | 208.5±9.4a | 116.1±9.1a | 108.1±13.4a | 96.5±4.5a | 115.4±5.1a | |

| α-tocopherol ES | 217.9±12.3a | 121.0±11.3a | 107.7±13.1a | 67.2±4.9a | 103.3±3.5a | |

| α-tocopherol HQ | 37.1±5.6a | 27.8±1.3a | 32.6±4.8a | 100.8±5.4 | 73.9±7.6a | |

| Ɣ-tocopherol | 3,4±0.2a | 2.3±0.3a | 2.9±0.4a | 13.7±3.8a | 16.7±1.2a | |

| Location-2 (2018) | ||||||

| α-tocopherol | 202.4±19,6a | 106.7±1,5a | 149.2±2,7b | 98.9±7.9a | 155.9±5.0b | |

| α-tocopherol ES | 243.3±11.3a | 103.4±1.0a | 158.4±1.3b | 93.3±5.6b | 156.0±4.5b | |

| α-tocopherol HQ | 95.0±5.1b | 21.3±0.2b | 23-9±2.1a | 157.6±5.1b | 116.3±3.8b | |

| Ɣ-tocopherol | 1.96±0,2b | 2.3±0.2a | 2.7±0.6a | 7.7±0.8b | 25.1±1.7b | |

| Location-1 (2019) | ||||||

| α-tocopherol | 294.1±11.1a | 157.2±4.0a | 138.6±6.8a | 133.7±5.4a | 154.9±10.9a | |

| α-tocopherol ES | 351.1±9.4a | 172.6±8.2a | 152.2±7.9a | 172.3±14.6a | 163.8±10.6 | |

| α-tocopherol HQ | 84.8±3.3a | 43.4±1.7a | 34.9±1.5a | 163.5±14.6a | 131.1±14.4a | |

| Ɣ-tocopherol | 3.5±0.3a | 2.4±0.2a | 2.07±0.2a | 48.2±0.3a | 13.4±0.9a | |

| Location-2 (2019) | ||||||

| α-tocopherol | 257.1±13.7b | 101.06±5.6b | 148.6±6.6a | 92.6±3.0b | 143.3±7.8a | |

| α-tocopherol ES | 279.8±6.7b | 119.4±6.4b | 161.6±6.8a | 68.8±6.9b | 114.7±8.3b | |

| α-tocopherol HQ | 82.3±2.0b | 22.2±1.2b | 42.3±2.0b | 196.5±7.6b | 146.1±14.1a | |

| Ɣ-tocopherol | 3.7±0.6a | 0.7±0.1b | 0.9±0.1b | 28.1±6.9b | 49.7±8.4b | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).