1. Introduction

Tomato is one of the most popular and widely consumed vegetables in the Mediterranean diet and has therefore been extensively characterized in terms of its nutritional profile and bioactive compounds, being an excellent source of ascorbic acid, carotenoids and flavonoids [

1]. In order to maximize its sensory quality, nutritional composition, and bioactivity, several studies have investigated how different factors such as the ripening state or tomato variety influence these aspects [

2]. Among the 17 goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015, are (i) responsible production and consumption, (ii) climate action, and (iii) the life of terrestrial ecosystems, with a strong emphasis on reducing greenhouse gas emissions, land use, energy consumption and, to a lesser extent, water use in the cultivation and production of food [

3]. Furthermore, organically grown vegetables are a good sustainable alternative, due to the exclusion of the use of synthetic chemicals and respect for the environment [

4]. The manner in which tomatoes are cultivated, as well as the variety of tomato being grown, can influence the quality of the fruit and may be of significant importance in the production of the crop from a profitable standpoint (obtaining a tomato with optimal quality and long commercial shelf life), to reduce costs at an industrial level, and healthy (obtaining a tomato with high nutritional density, rich in bioactive compounds and high antioxidant activity) [

5]. Moreover, organic farming compared to conventional cultivation in terms of quality, nutritional intake, and bioactivity is better [

6]. Currently, there is little data about the characterization of the quality of organic tomato and the information available to the farmer about the influencing factors is scarce.

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and cancer, killed 41 million people (74% of global deaths) in 2022 [

7]. Research supports that the oxidative stress, known as an imbalance between reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant defenses, has been shown to be part of the triggering and development of the pathophysiological changes associated to noncommunicable diseases [

8,

9]. In this sense, numerous epidemiological and clinical studies have shown how tomato consumption reduces the risk of contracting numerous diseases such as cardiovascular diseases or cancer [

10]. This beneficial role of tomato consumption has been attributed to its content of polyphenols and carotenoids (mainly lycopene and β-carotene) since these compounds inhibit reactions mediated by ROS. According to numerous studies, the content of these antioxidant compounds in tomato fruits depends on genetic and environmental factors, as well as on the ripening stage of the fruit [

11]. In addition, functional foods are gaining attention in the field of nutrition because of their beneficial effects on health and the prevention and treatment of many diseases [

12]. In this sense, the extraction of tomato antioxidant compounds, mainly the carotenoid lycopene, for the subsequent generation of functional foods, is gaining attention within the food and pharmaceutical industries [

13,

14]. Therefore, it is of a great interest to know the variations in the content of antioxidant compounds during the ripening process in order to obtain fruits with the highest bioactivity potential. In light of these well-known evidences presented, the objective of this study was to evaluate, for the first time, the quality, nutritional, and antioxidant (composition and activity) variations throughout the ripening process of fruits from three Spanish tomato varieties (

Josefina,

Karelya and

Muchamiel) cultivated under organic farming practices. The aim was to determine the optimal ripening stage in order to maximize the nutritional and antioxidant potential of the fruits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Folin & Ciocalteu′s phenol reagent, gallic acid, Trolox, 2,2-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), azo2,20-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH), sodium fluorescein, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and 2,4,6-Tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri, USA).

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

Bioalverde S.L. supplied the organic tomato samples. Specifically, 30 plants of each variety, Josefina and Karelya, which are cherry-like tomatoes, and Muchamiel, a type of salad tomato, were planted in greenhouse, divided in 2 different areas (with 15 plants of each species/area).

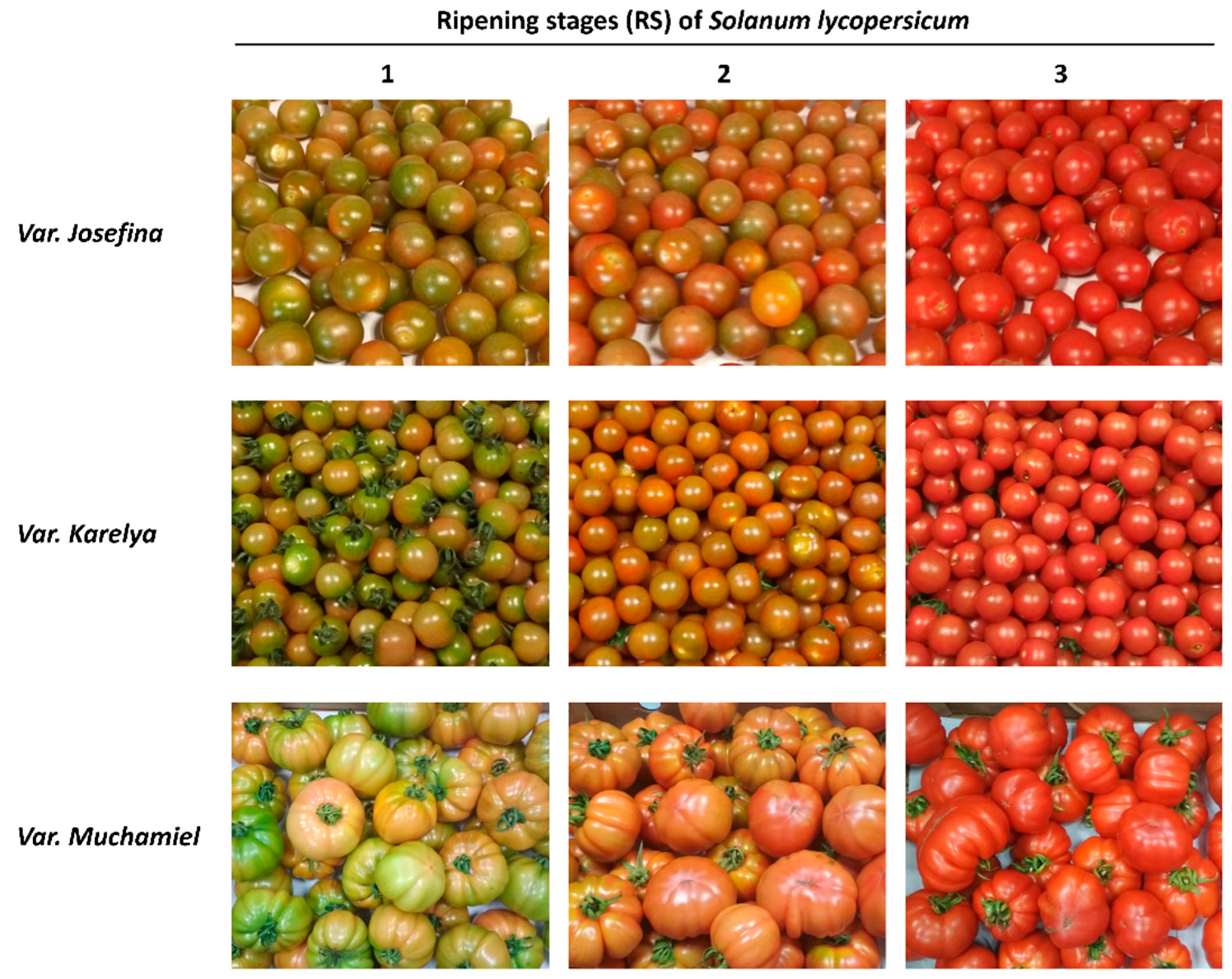

Three consecutive ripening stages (RS) were selected according to the external colour as follows: RS1 changing colour fruit in which green coloured areas are more prevalent than red ones; RS2 changing colour fruit in which red coloured areas are more prevalent than green ones; RS3 fully mature fruit with an intense red colour. A minimum of 40 tomato fruits were collected for each ripening stage and for each variety. Non-destructive determinations (such as fruit size, weight and colour) were carried out in 20 fruits (size and weight) or 10 fruits (colour). The same fruits used for the colour measurement (n = 10) were used for the texture (firmness) determination. For the rest of the measurements, homogenates of tomatoes were used. Specifically, the humidity, pH, and SST determinations were carried out immediately after preparing the homogenate while determinations of antioxidant activity, total phenols, and titratable acidity were carried out on frozen aliquots of the supernatant of the homogenate. The determinations of carotenoid and nutritional composition were carried out on lyophilized aliquots of the homogenate.

2.3. Physicochemical Characterization and Quality Parameters

2.3.1. Fruit Weight and Size

Fruits of each variety were weighed using an analytical balance (model AX224, Sartorius). Fruits sizes were determined as equatorial diameter and measured with a digital calliper (VWR).

2.3.2. Colour

The evaluation of the fruit colour was carried out using a colourimetry technique. The colour was also expressed in terms of the CIE L* (luminosity, whiteness or brightness/darkness), a* (redness/greenness) and b* (yellowness/blueness) coordinates [

15]. Colorimetric measurements on the tomatoes were performed using a BYK-Gadner, Model 9000, Colour-view™ spectrophotometer (Silver Spring, MD, USA). Results are expressed as a/b.

2.3.3. Total Soluble Solids (TSS) Content

The TSS content was measured, in a small sample (2 drops) of supernatant from the fruit homogenate using a portable handheld refractometer (Bellingham + Stanley, Model 0-32º BRIX ATC) with an accuracy of ± 0.1 °Brix [

16].

2.3.4. pH Determination

The pH value was determined by a pH meter (model pH 1000L, VWR) using the homogenate prepared from the collected fruits.

2.3.5. Texture

Texture (firmness) was measured with an Instron Universal Testing Machine (Canton, MA, USA) fitted with a Kramer shear compression cell. The cross-head speed was 200 mm/min. The firmness (shear compression force) of the tomato fruits was expressed as N/100 g, and the value was the mean of ten measurements, each of which was performed on one fruit for cherry-like varieties and with one quarter of fruit for Muchamiel cultivar.

2.3.6. Proximate Composition

The proximate composition of the fruits was evaluated for each cultivar at the selected ripening stages (RS1, RS2, and RS3). The determinations of dry matter, moisture, ash, protein, fat, and carbohydrates were made by methods of the AOAC [

17] and the results expressed in relative units (%). Dry matter content and moisture were determined by gravimetry by using a moisture balance (OAHUS MB35). The mineral content (ash) was determined by means of the calcination method. The total protein fraction was estimated by using a LECO Elemental Analyser (LECO CHNS-932) and the protein content was deduced from the nitrogen content (Dumas method) as follows: Protein (%) = Nitrogen (%) × 6.25 [

18]. Total lipids (fat) content was determined by the Soxhlet method [

19]. The determination of total carbohydrates (including fiber) was carried out by the differential method by subtracting the sum of percentages of the rest of nutrients (total proteins, total lipids, minerals and moisture) from 100 [

17]. Each parameter was analysed in triplicate.

2.3.7. Carotenoid Analysis

Carotenoid pigments were extracted and analysed by HPLC according to the procedure described in de los Santos et al. (2021) [

20] as adapted from Minguez-Mosquera et al. (1993) [

20,

21]. Results were expressed as mg/kg dry weight.

2.3.8. Total Polyphenol Determination

Total polyphenols were quantified by using Folin & Ciocalteu method. A 20 μL homogenate sample (diluted 1:2 with distillated water) was mixed with 100 μL Folin & Ciocalteu′s phenol reagent and with 80 μL 7.5% Na2CO3 solution. After incubation for 2 h at room temperature and in the dark, the absorbance was read at 765 nm with a Synergy™ HT-multimode microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). A calibration curve using different gallic acid concentrations (25 – 250 mg/L) was used to calculate the results as gallic acid equivalents (mg/kg dry weight).

2.4. Antioxidant Capacity

All assays were carried out in the homogenate of the collected fruits at each ripening stage.

2.4.1. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

A 20 µL homogenate sample (diluted 1:20 with water) was mixed with 280 µL FRAP solution (0.83 mM TPTZ and 1.66 mM FeCl3 × 6H2O in 0.25 M acetate buffer, pH 3.6). After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, the absorbance at 595 nm was measured with the microplate reader (Biotek Instruments). The values were extrapolated by a Trolox standard curve.

2.4.2. Trolox Equivalent Antioxidant Capacity (TEAC) Assay

To perform this assay, the ABTS radical solution was used. A total of 280 µL of this solution was mixed with 20 µL of homogenate sample (diluted 1:30 with water). After 30 min of incubation at 30 °C, the ABTS radical content was quantified by a microplate reader (Biotek Instruments) at 730 nm. The TEAC values were extrapolated by a Trolox standard curve.

2.4.3. Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity (ORAC) Assay

A 50 µL homogenate sample (diluted 1:500 with phosphate buffer) was added to 100 µL of sodium fluorescein (2.93 µg/µL) and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Then, 50 µL AAPH (60.84 mM) was added to generate peroxyl radicals. Thus, every 5 min, over 2 h, the decay of fluorescein at its maximum emission of 528 nm was measured using the microplate reader (Biotek Instruments). The area under the curve (AUC) was calculated using a Trolox calibration curve.

2.4.4. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Radical Scavenging Activity

A 40 µL homogenate sample (diluted 1:10 with distilled water) were added to 200 µL methanol and mixed with 60 µL DPPH radical solution (0.23 mg/mL). After 1 h of incubation at 30 °C, the DPPH radical was measured at 520 nm with a microplate reader (Biotek Instruments). The results were calculated as percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity by the following equation:

where C was the control group (H

2O + methanol + DPPH radical solution) and S was the sample.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Results were showed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and a two-way ANOVA test, followed by multiple comparisons and Tukey’s test correction, was applied. Correlations between antioxidant activity assayed by the DPPH radical and the different carotenoids and polyphenols content were analysed by Pearson's correlation. Differences with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were graphed and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Quality Parameters of Tomato Varieties during the Ripening Process

Fruit quality parameters obtained for the three studied cultivars throughout the ripening process are summarized in

Table 1. Cherry-like tomato fruits showed a mean weight of 17 g, which contrasted with salad tomato presenting a mean fruit weight up to 244 g. This observation was also in accordance to the fruit size (determined as equatorial diameter), 31 mm and 83 mm for cherry-like and salad tomato fruits, respectively. Interestingly, there was a marked difference in firmness between the two types of tomatoes, so that the average firmness in cherry-like fruits was double when compared to salad tomatoes, 21.4 N/g and 10.6 N/g respectively. At last, although the two types of tomatoes possessed a mean pH of 4, the TSS of the cherry-like tomatoes was around 6.9 ºBrix, while that of the salad tomatoes was 3.8 ºBrix. Regarding variations during the ripening process, the weight and size of the tomatoes differently varied throughout the time depending on the tomato variety. While the

Josefina variety showed an increase in weight and size during the ripening process, the

Muchamiel variety reduced its weight and size in RS3. The

Karelya variety, however, did not show changes in weight and size throughout the process. The pH value also evolved differently depending on the tomato variety. The two cherry varieties showed an increase in pH levels throughout the ripening process, while the pH values in the

Muchamiel variety did not change.

On the other hand, the three tomato varieties showed a significant reduction in the firmness values throughout the ripening process, while the TSS and colour increased significantly, reaching the highest levels in RS3. The colour changes along ripening process are observed in

Figure 1.

3.2. Nutritional Composition of Tomato Varieties during the Ripening Process

As shown in

Table 2, the three tomatoes varieties were mainly compounded by water, being

Muchamiel the variety that present the highest humidity value (95.50 ± 0.84%, value in RS1) which was significantly different to the humidity value of

Josefina (RS1: 92.9 ± 0.55%,

p < 0.0001) and

Karelya (RS1: 91.9 ± 0.33%,

p < 0.0001) varieties. Furthermore, carbohydrates were the most representative macronutrients in tomatoes, followed by proteins and lipids. The

Karelya variety showed significantly higher levels of proteins (0.27 ± 0.02%) and carbohydrates (9.11 ± 0.03%) in RS3 compared to

Josefina (0.20 ± 0.01%,

p = 0.029; 7.67 ± 0.19%,

p < 0.0001, respectively) and

Muchamiel (0.22 ± 0.03%,

p = 0.044; 3.91 ± 0.94%,

p = 0.05, respectively).

Muchamiel was the variety with the highest levels of lipids (0.19 ± 0.02%). No significant differences were observed in lipids content between

Muchamiel and

Josefina (p = 0.166), or

Karelya (

p = 0.258). Regarding minerals, the

Karelya variety presented the highest levels in RS3 (0.46 ± 0.02), that was significantly higher than

Muchamiel (0.34 ± 0.02%,

p < 0.0001) and

Josefina (0.24 ± 0.03%,

p < 0.0001) values.

Analogously, the nutritional composition of each tomato variety varied through the ripening process (

Table 2). The water content showed a statistically significant reduction at RS3 for both cherry varieties in comparison to RS1 (

Josefina:

p = 0.027;

Karelya:

p < 0.0001), while

Muchamiel variety did not show changes in the moisture content value (RS1 compared to RS3

p = 0.789). Regarding macronutrients, the three varieties showed a statistically significant (

p < 0.05) increase in the lipid content during the ripening process, while the carbohydrates levels increased only in the cherry varieties (

Josefina:

p = 0.0002;

Karelya:

p < 0.0001), but not in the

Muchamiel variety (

p > 0.05). Furthermore, the

Karelya variety was the only that show a statistically significant (

p = 0.003) increase in the protein levels throughout the ripening process. On the other hand, the mineral content significantly increased in the

Karelya variety (

p = 0.016), without showing changes in the other two varieties (

p > 0.05).

3.3. Evolution of Polyphenols Content in Tomato Varieties during the Ripening Process

As shown in

Table 3, the three varieties of tomatoes showed an increase in the levels of total polyphenols throughout the ripening process. Specifically, the

Josefina and

Karelya varieties showed a significant increase in total polyphenols already in RS2 of the ripening process (

Josefina:

p = 0.022;

Karelya:

p = 0.003, with respect to RS1), without significant differences between RS2 and RS3. However, the

Muchamiel variety did not show a significant increase in the levels of total polyphenols in RS2 (

p = 0.725 compared with RS1 stage), but it did increase its polyphenol levels in advanced RS3 stage (in comparison to RS1,

p = 0.0001; and RS2,

p = 0.003).

3.4. Evolution of Carotenoids Levels in Tomato Varieties during the Ripening Process

The variations in the total and individual carotenoid content (total carotenoid, lycopene and -carotene) were evaluated (

Table 3). Thus, the three tomato varieties showed a significant increase (

p < 0.0001) in total carotenoid during the ripening process, reaching the highest levels in RS3 (

Table 3). In more detail, the ripening process allowed a significant increase (

p < 0.0001) of lycopene levels in all three varieties, reaching the highest levels in RS3 stage (236 ± 18.60 mg/kg dry weight, 245 ± 22.30 mg/kg dry weight and, 392 ± 28.60 mg/kg dry weight respectively). On the other hand, β-carotene levels were increased differently. While the

Muchamiel variety reached its highest β-carotene levels at RS3 stage (59.50 ± 12.20) (

p < 0.0001),

Josefina and

Karelya varieties reached the highest levels at RS2 and RS3, respectively (

Josefina: 74.30 ± 3.84;

p < 0.0001;

Karelya: 48.30 ± 3.75

p = 0.0003), with no observed differences between RS2 and RS3 stages (

Josefina:

p = 0.968;

Karelya:

p = 0.507).

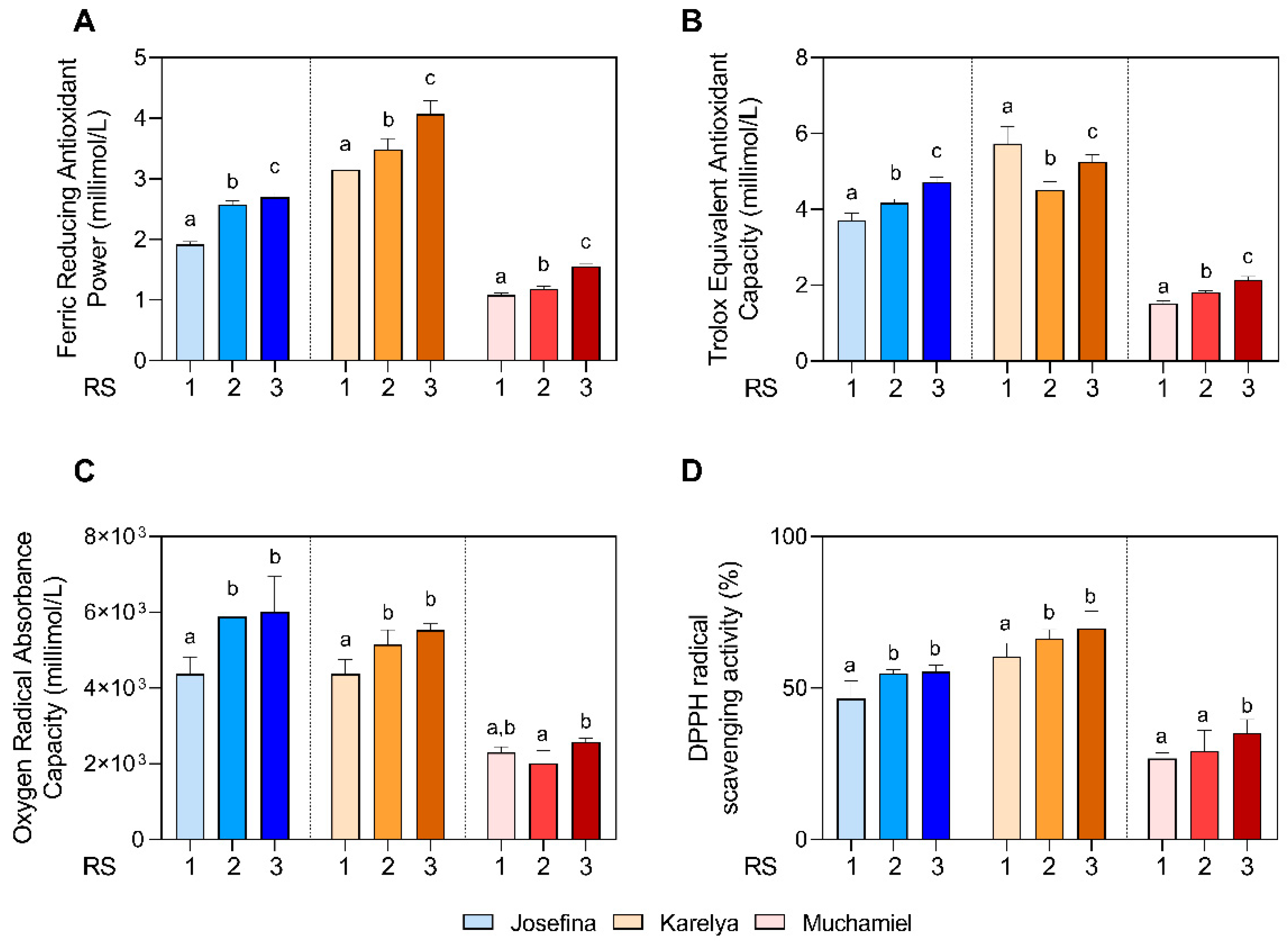

3.5. Effect of Ripening Process on Antioxidant Capacity of Tomato Varieties

To find out if the antioxidant capacity of tomatoes increased during the ripening process, the FRAP, ORAC, TEAC and DPPH antioxidant tests were carried out at each ripening stage.

As observed in

Figure 2A, the FRAP value increased in RS2 and RS3 stages, reaching the maximum value in RS3, in all three tomato varieties studied (RS3:

Josefina: 2.70 ± 0.08 mmol/L;

Karelya: 4.07 ± 0.22 mmol/L;

Muchamiel: 1.56 ± 0.05 mmol/L,

p < 0.0001 with respect to RS1). As shown in

Figure 2B, the capacity to scavenge the ABTS radical (TEAC assay) increased throughout the ripening process for the

Josefina (RS1: 3.72 ± 0.19 mmol/L; RS2: 4.17 ± 0.10 mmol/L; RS3: 4.72 ± 0.13 mmol/L) and

Muchamiel (RS1: 1.52 ± 0.07 mmol/L; RS2: 1.81 ± 0.06 mmol/L; RS3: 2.14 ± 0.09 mmol/L) varieties. However, ABTS scavenging capability significantly decreased in the

Karelya variety (RS1: 5.74 ± 0.44 mmol/L; RS2: 4.52 ± 0.21 mmol/L; RS3: 5.26 ± 0.19 mmol/L). The results for the ORAC assay showed how the oxygen radical absorption capacity increased in RS2 (

Josefina:

p = 0.002;

Karelya:

p = 0.005) and RS3 (

Josefina:

p = 0.001;

Karelya:

p = 0.0002) for the cherry-like varieties, without significant differences (

Josefina:

p = 0.934;

Karelya:

p = 0.194) between these stages (

Figure 2C). However, the

Muchamiel variety did not show significant differences in ORAC at any ripening stage (

Figure 2C).

Regarding the DPPH radical scavenging activity, the

Josefina and

Karelya varieties increased their activity in RS2 (

Josefina: 54.8 ± 1.22%,

p = 0.006;

Karelya: 66.4 ± 2.93%,

p = 0.03 with respect to RS1) and RS3 (

Josefina: 55.4 ± 2.15%,

p = 0.005;

Karelya: 69.7 ± 5.69%,

p = 0.001 with respect to RS1) stages, without significant differences being found between them (

Figure 2D). However, the

Muchamiel variety significantly (

p = 0.0009) increased the DPPH radical scavenging capacity in RS3 stage (35.2 ± 4.35%), with no significant differences being found between RS1 (26.8 ± 1.90%) and RS2 (29.3 ± 6.72) stages (

Figure 2D).

Regarding antioxidant capacity differences between varieties, both cherry tomatoes stood out for their greater antioxidant activity compared to the Muchamiel salad tomato. Among the cherry varieties, it was Karelya that showed the highest levels of antioxidant activities in all assays, except for ORAC.

3.6. Correlation between Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Activity

To identify a possible relation between the carotenoid or polyphenol content and the antioxidant capacity, data were analyzed by Pearson's correlation. As shown in

Table 4, in the

Josefina variety, significant and positive correlations were observed between the levels of total carotenoids, β-carotene and lycopene with the values of FRAP, TEAC and ORAC, as well as negative correlations between these with DPPH.

On the other hand, total polyphenols established positive correlations with the FRAP and TEAC values, but no statistically significant correlation with ORAC and DPPH was observed. In the

Karelya variety (

Table 5), total carotenoids, β-carotene and lycopene showed positive and significant correlations with the values of FRAP and ORAC, as well as negative correlation with the values of radical DPPH. However, carotenoid levels did not show significant correlation with TEAC.

Regarding polyphenols, positive and significant correlations are shown with FRAP and ORAC, but no with DPPH and ABTS. In the

Muchamiel variety (

Table 6), positive and significant correlations were observed between total polyphenols, total carotenoids, β-carotene and lycopene, and FRAP and TEAC. With respect to other assays, only a positive correlation was observed between β-carotene and ORAC levels, and negative correlations between total carotenoid and lycopene levels and radical DPPH values.

4. Discussion

In this study, the quality, nutritional, and antioxidant variations during the ripening process of three Spanish tomato varieties (including two cherry-like and one salad tomatoes) were evaluated. The tomatoes were grown under organic farming conditions and evaluated in three different ripening stages, according to the colour of the fruits. It was shown that the ripening process affects each variety of tomato differently, in relation to some parameters of quality, nutritional and antioxidant levels or activities.

Firstly, the quality of each tomato fruit was evaluated through the analysis of pH, TSS, and moisture content. The pH values, which determine the acidity of the fruit, were similar to those observed in other studies [

22,

23]. On the other hand, TSS is the index that most influences manufacturing performance of fruits for industrial processing. This depends on the variety and agronomic conditions, including irrigation and ripening period. In this sense, it has been observed that tomatoes grown under organic conditions have higher TSS levels (3.90 ºBrix) than tomatoes that have been grown under conventional conditions (3.21 ºBrix) [

6]. The tomatoes in our study showed an increase in TSS throughout the ripening process. Nevertheless, the levels observed were comparable to those previously documented for other tomato varieties [

22,

24], regardless of the cultivation method employed (organic or conventional). Finally, the dry matter content, which is essential for the quality of the fruit and has a beneficial effect on the taste qualities of the produce, was found to be within the normal range of 5 to 7.5% [

24]. The rest of the quality parameters, including weight, size, colour, and firmness, showed similar values to those previously established in the same or others tomato varieties [

25,

26], except the weight of the

Karelya and

Muchamiel varieties, which were higher than those established by other authors [

27,

28].

Regarding the nutritional analysis, the levels of carbohydrates, lipids, and minerals were similar to other tomatoes [

29,

30,

31]. However, the protein fraction was slightly below average levels, probably due to the tomatoe varieties and/or the ripening cultivation under organic conditions. In addition, the ripening process did not affect the nutritional composition of the

Muchamiel variety, which only observed a slight increase in the lipid fraction in RS3. However, cherry varieties, in addition to showing a decrease in moisture from RS2, showed an increase in the contents of proteins, carbohydrates, and minerals, in some cases (such as carbohydrates) already from the RS2 stage.

On the other hand, the levels of polyphenols and carotenoids increased significantly during the ripening process. This is of great interest as the functional value of tomatoes is mainly determined by the content of carotenoids and polyphenols, which have attracted the interest of many researchers in the field due to their biological and physicochemical properties. Lycopene is the main carotenoid in tomatoes and is responsible for their characteristic red colour. This bioactive component, along with other carotenoids, has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of cancer cells, as well as exert a powerful antioxidant effect, of great importance in counteracting the development of numerous diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases or those related to age. In this sense, the carotenoid content has been shown to depend on numerous factors such as the stage of ripening, the variety of tomato or the cultivation conditions. Regarding this last factor, it has been shown that the lycopene content is higher in tomatoes cultivated under organic conditions than in tomatoes obtained following conventional practices [

6]. In our study, the levels of lycopene, β-carotene, and total carotenoids in the ripening stage RS3 were in accordance with previous studies [

1,

15,

23,

32,

33,

34].

Furthermore, the levels of total polyphenols were comparable to those observed in previous studies [

33,

35,

36] in which conventional tomatoes cultivations were employed. Our results demonstrate that tomato ripening significantly enhances the levels of bioactive compounds, thereby enhancing the functional value of tomatoes. Our results can also indicate the optimal harvesting time of tomatoes according to the bioactive compound of interest in order to optimise its content (

Table 7).

To evaluate the antioxidant activity of tomatoes during the ripening process, four antioxidant assays were carried out: FRAP, to measure the total antioxidant status, and ORAC, TEAC, and DPPH to evaluate the radical scavenging capacity. The correlation analysis showed how the antioxidant effect exerted depends on each bioactive compound and the different used antioxidant assays. In fact, due to the chemical nature of the method used to measure antioxidant activity, it is important to use several methods to evaluate a possible effect mediated by different mechanisms of action. While TEAC and DPPH assays measure the antioxidant capacity exerted by hydrosoluble (polyphenols) and liposoluble (carotenoids) compounds, ORAC and FRAP assays can only measure those hidrosoluble. Our results show that the global antioxidant status increased significantly during the ripening process, reaching the highest levels in RS3. Although other authors have demonstrated the antioxidant capacity of several tomato varieties [

15,

23,

30,

33,

37], it is the first time that the antioxidant activity was evaluated in the

Karelya,

Josefina, and

Muchamiel varieties, in three different stages of ripening and grown under organic conditions. It has been shown that the total antioxidant capacity is higher in tomatoes that have been grown in organic crops than in tomatoes that have been grown in conventional crops [

31,

38]. This would be in agreement with the results obtained by Vinha et al. [

6], in which showed DPPH inhibition values in tomatoes grown under organic practices (62.1 ± 1.3%) similar to those observed in the present study and both above those observed for tomatoes grown using conventional cultivation conditions (58.4 ± 0.7%).

Regarding the optimal time for fruit collection based on its maximum antioxidant capacity, harvesting should be carried out when the tomatoes reach RS3. However, harvesting could be brought forward in some cases, depending on whether the final goal is to obtain the greatest scavenging activity. In this sense, cherry tomatoes have shown to achieve their highest scavenging activity in RS2, while salad tomato has shown their highest DPPH, ORAC and TEAC values in RS3. The acquisition of this knowledge would result in an optimization of antioxidant activity and scavenging capacity of tomatoes according to the variety.

5. Conclusions

This study examines the diverse effects of ripening on various tomato varieties, including their impact on quality, nutritional content, and antioxidant levels. As expected, ripening significantly enhances the levels of carotenoids and polyphenols in the studied varieties, thereby enhancing the functional value of tomatoes and their antioxidant activity, particularly in fully ripened tomatoes. Harvesting tomatoes at ripening stage 3 maximizes bioactive contents and antioxidant capacity in salad tomatoes but not in cherry tomatoes varieties. Particularly, TEAC, ORAC and DPPH assays showed a higher antioxidant capacity in RS2 in Josefina and Karelya varieties. Results obtained in this study provide information about the optimal ripening times for the studied varieties tomatoes, which can be used to guarantee their quality even before harvest. Despite all this, nutritional intervention studies should be carried out to ensure this since only antioxidant activity has been measured here, and the bioactive compounds analyzed in the present study (such as lycopene) present other biological properties that should be assessed in vivo.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, IC, MSFP, and DHM; design of experiments, DHM, MSFP, and IC; methodology, DHM, and IC; investigation, DHM, ICC, and GSS, data analysis, ICC, GSS, MSFP, and IC; writing—original draft preparation, ICC, and GSS; writing—review and editing, DHM, MSFP, and IC; funding acquisition, DHM, FM, MSFP, and IC. All authors approved the final version.

Funding

The research was funded by the Centro para el Desarrollo Tecnológico Industrial-CDTI (2019/00064/001). G.S.-S. was supported by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación, Gobierno de España (JDC2022-048411-I). I.C.-C. was supported by the grant I-006-2024 (Universidad de Almería, Spain).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the company Bioalverde for providing the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fattore, M.; Montesano, D.; Pagano, E.; Teta, R.; Borrelli, F.; Mangoni, A.; Seccia, S.; Albrizio, S. Carotenoid and flavonoid profile and antioxidant activity in “Pomodorino Vesuviano” tomatoes. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2016, 53, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, N.; Génard, M. Tomato quality as influenced by preharvest factors. Scientia Horticulturae 2018, 233, 264–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K.; Mishra, I. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 2030 and environmental sustainability: race against time. Environmental Sustainability 2019, 2, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Ullah, M.I.; Sajjad, A.; Shakeel, Q.; Hussain, A. Environmental and health effects of pesticide residues. Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 48: Pesticide Occurrence, Analysis and Remediation Vol. 2 Analysis, 2021; 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, E.; Bowyer, C.; Tsouza, A.; Chopra, M. Tomatoes: An Extensive Review of the Associated Health Impacts of Tomatoes and Factors That Can Affect Their Cultivation. Biology 2022, 11, 239. s Note: MDPI stays neu–tral with regard to jurisdictional claims in …: 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Barreira, S.V.; Costa, A.S.; Alves, R.C.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Organic versus conventional tomatoes: Influence on physicochemical parameters, bioactive compounds and sensorial attributes. Food and chemical toxicology 2014, 67, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaltaev, N.; Axelrod, S. Cardiovascular disease mortality and air pollution in countries with different socioeconomic status. Chronic Diseases and Translational Medicine 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Rad, M.; Anil Kumar, N.V.; Zucca, P.; Varoni, E.M.; Dini, L.; Panzarini, E.; Rajkovic, J.; Tsouh Fokou, P.V.; Azzini, E.; Peluso, I. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Frontiers in physiology 2020, 11, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyedsadjadi, N.; Grant, R. The potential benefit of monitoring oxidative stress and inflammation in the prevention of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). Antioxidants 2020, 10, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.S.; Paswan, S.; Srivastava, S. Tomato-a natural medicine and its health benefits. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry 2012, 1, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, Y.; Dadomo, M.; Di Lucca, G.; Grolier, P. Effects of environmental factors and agricultural techniques on antioxidantcontent of tomatoes. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2003, 83, 369–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granato, D.; Barba, F.J.; Bursać Kovačević, D.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Cruz, A.G.; Putnik, P. Functional foods: Product development, technological trends, efficacy testing, and safety. Annual review of food science and technology 2020, 11, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madia, V.N.; De Vita, D.; Ialongo, D.; Tudino, V.; De Leo, A.; Scipione, L.; Di Santo, R.; Costi, R.; Messore, A. Recent advances in recovery of lycopene from tomato waste: A potent antioxidant with endless benefits. Molecules 2021, 26, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, W.; Latif, A.; Lianfu, Z.; Jian, Z.; Chenqiang, W.; Rehman, A.; Hussain, A.; Siddiquy, M.; Karim, A. Technological advancement in the processing of lycopene: a review. Food Reviews International 2022, 38, 857–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, C.; Walia, S.; Nagal, S.; Walia, S.; Singh, J.; Singh, B.B.; Saha, S.; Singh, B.; Kalia, P.; Jaggi, S. Functional quality and antioxidant composition of selected tomato (Solanum lycopersicon L) cultivars grown in Northern India. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2013, 50, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC, H.W. International A: Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC International. The Association: Arlington County, VA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- AOAC, H.W. International A: Official Methods of Analysis of the AOAC International. The Association: Arlington County, VA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bradstreet, R.B. Kjeldahl method for organic nitrogen. Analytical Chemistry 1954, 26, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, M.L.; Garcıa-Ayuso, L. Soxhlet extraction of solid materials: an outdated technique with a promising innovative future. Analytica chimica acta 1998, 369, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minguez-Mosquera, M.I.; Hornero-Mendez, D. Separation and quantification of the carotenoid pigments in red peppers (Capsicum annuum L.), paprika, and oleoresin by reversed-phase HPLC. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 1993, 41, 1616–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Los Santos, B.; García-Serrano, P.; Romero, C.; Aguado, A.; García-García, P.; Hornero-Méndez, D.; Brenes, M. Effect of fertilisation with black table olive wastewater solutions on production and quality of tomatoes cultivated under open field conditions. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 790, 148053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klunklin, W.; Savage, G. Effect on quality characteristics of tomatoes grown under well-watered and drought stress conditions. Foods 2017, 6, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinha, A.F.; Alves, R.C.; Barreira, S.V.; Castro, A.; Costa, A.S.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Effect of peel and seed removal on the nutritional value and antioxidant activity of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) fruits. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2014, 55, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyanova, A.; Veleva, P.; Valkova, E.; Pevicharova, G.; Georgiev, M.; Valchev, N. Dry matter content and organic acids in Tomatoes, Greenhouse grown under different Manuring and Irrigation Modes. PROCEEDINGS BOOK 2018, 257. [Google Scholar]

- Quamruzzaman, A.; Islam, F.; Akter, L.; Mallick, S.R. Effect of Maturity Indices on Growth and Quality of High Value Vegetables. American Journal of Plant Sciences 2022, 13, 1042–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolik, P.; Morais, C.L.; Martin, F.L.; McAinsh, M.R. Determination of developmental and ripening stages of whole tomato fruit using portable infrared spectroscopy and Chemometrics. BMC plant biology 2019, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfosea-Simón, M.; Simón-Grao, S.; Zavala-Gonzalez, E.A.; Navarro-Morillo, I.; Martínez-Nicolás, J.J.; Alfosea-Simón, F.J.; Simon, I.; García-Sánchez, F. Ionomic, metabolic and hormonal characterization of the phenological phases of different tomato genotypes using omics tools. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, 293, 110697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Marín, J.; Issa-Issa, H.; Clemente-Villalba, J.; García-Garví, J.M.; Hernández, F.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á.A.; Calín-Sánchez, Á.; Noguera-Artiaga, L. Physicochemical, volatile, and sensory characterization of promising cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivars: Fresh market aptitudes of pear and round fruits. Agronomy 2021, 11, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guil-Guerrero, J.; Rebolloso-Fuentes, M. Nutrient composition and antioxidant activity of eight tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) varieties. Journal of Food Composition and analysis 2009, 22, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Carvalho, A.M.; Ferreira, I.C. Nutritional composition and antioxidant activity of four tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum L.) farmer’varieties in Northeastern Portugal homegardens. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lima, D.P.; Júnior, E.d.S.P.; de Menezes, A.V.; de Souza, D.A.; de São José, V.P.B.; da Silva, B.P.; de Almeida, A.Q.; de Carvalho, I.M.M. Chemical composition, minerals concentration, total phenolic compounds, flavonoids content and antioxidant capacity in organic and conventional vegetables. Food Research International 2024, 175, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erba, D.; Casiraghi, M.C.; Ribas-Agustí, A.; Cáceres, R.; Marfà, O.; Castellari, M. Nutritional value of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum L.) grown in greenhouse by different agronomic techniques. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2013, 31, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilahy, R.; Hdider, C.; Lenucci, M.S.; Tlili, I.; Dalessandro, G. Phytochemical composition and antioxidant activity of high-lycopene tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivars grown in Southern Italy. Scientia Horticulturae 2011, 127, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahoz García, I.; Leiva-Brondo, M.; Martí, R.; Macua, J.I.; Campillo, C.; Roselló, S.; Cebolla-Cornejo, J. Influence of high lycopene varieties and organic farming on the production and quality of processing tomato. 2016.

- Riahi, A.; Hdider, C. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of organically grown tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivars as affected by fertilization. Scientia Horticulturae 2013, 151, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallverdú-Queralt, A.; Medina-Remón, A.; Casals-Ribes, I.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M. Is there any difference between the phenolic content of organic and conventional tomato juices? Food chemistry 2012, 130, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.-G.; Park, K.-S. Ripening Process of Tomato Fruits Postharvest: Impact of Environmental Conditions on Quality and Chlorophyll a Fluorescence Characteristics. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isabel, M.; Noelia, K. Effect of cultivation method and processing on total polyphenols content and antioxidant capacity of tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum). Clinical Nutrition and Hospital Dietetics 2020, 40, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).