1. Introduction

Microgreens, in their modern form, were first introduced in the 1980s in San Francisco, where chefs at select restaurants began preparing them [

1]. They are young plants harvested between 1 and 3 weeks of growth, typically reaching heights of 3–10 cm, with fully developed cotyledons or the first true leaves.

A wide range of species and cultivars can be grown as microgreens, including vegetables, ornamental plants, and weeds. The choice of species depends on factors such as health safety, seed cost, availability, growth rate, sensory qualities, and potential nutritional value.

Brassicaceae species, particularly broccoli, mustard, radish, kale, and cress, are most commonly chosen, with other families like

Amaranthaceae,

Apiaceae,

Cucurbitaceae, and

Lamiaceae also frequently used [

2,

3].

Microgreens are rich in minerals, phytonutrients, and secondary metabolites, including chlorophyll, beta-carotene, vitamins, antioxidants, and phenolic compounds. Many microgreens contain higher concentrations of these compounds than conventionally grown vegetables [

4,

5]. This has been confirmed by multiple studies [

6,

7,

8].

The short cultivation period of microgreens also means they require minimal space, substrates, and water. Fertilisation is often unnecessary in standard production. Microgreens can be cultivated in densely populated areas, with options for soilless vertical farming, which optimises space and reduces costs [

1,

9].

Over a quarter of the population suffers from micronutrient deficiencies, such as vitamin A, zinc, iron, magnesium, or iodine [

10]. Biofortification offers a potential solution by enhancing nutrients in plants without compromising yield or quality [

11]. Biofortification methods include breeding, genetic manipulation, nanotechnology, green technologies, and agronomic biofortification. Agronomic biofortification optimises fertilisation to increase nutrient accumulation in plant tissues [

12]. Soilless cultivation systems using nutrient solutions with precise compositions minimise environmental risks, such as nutrient leaching or soil accumulation [

13,

14], while also improving crop quality and offering a sustainable solution for microgreens cultivation. Studies on biofortification have focused on vitamins C, iron, zinc, selenium, and iodine [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Magnesium, the fourth most abundant cation in the human body, is essential for activating over 300 enzymes, supporting muscle and nerve function, maintaining healthy bone and tooth structure, and boosting the immune system. The recommended daily intake (RDI) is 420 mg for men and 320 mg for women [

19]. Magnesium deficiency is common in developed countries [

20,

21]. The depletion of magnesium in soils, due to poor agronomic practices, and food processing, which reduces magnesium content, are primary causes of dietary deficiency. For example, processing grains into flour can decrease magnesium content by 82–97% [

22,

23].

This study is among the first to focus on the agronomic biofortification of microgreens with magnesium. An experiment was conducted with six species (broccoli, mustard, cress, basil, sunflower, and cucumber) using magnesium sulfate. The aim was to assess whether MgSO4 application effectively increases magnesium content in these species, making them suitable sources of magnesium. The impact of MgSO4 on secondary metabolites and yield was also evaluated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

Six plant species were used in the experiment. Three commonly used species in microgreens production from the Brassicaceae family were selected: cress (Lepidium sativum L. cv. 'Dánská'), mustard (Sinapis alba L.), and broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica cv. 'Limba'). Additionally, representatives from three other families were chosen: Lamiaceae (basil, Ocimum basilicum L.), Asteraceae (sunflower, Helianthus annuus L.), and Cucurbitaceae (cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. cv. 'Othello F1'). All seeds were purchased from MORAVOSEED CZ a.s. (Mikulov, CZ).

The plants were cultivated in a climate chamber at the Faculty of Horticulture, Mendel University in Brno. The phytotron FYTOSCOPE FS-SI-4600 was equipped with white LED lighting, providing a Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density (PPFD) of 130 µmol·m

−2·s

−1 and a measured light intensity of 7,800 lux at plant height. The light period was set to 16/8 hours (day/night), with a temperature of 24/20°C and relative humidity (RH) ranging from 60 to 70%. The plants were grown in PP trays measuring 15 × 11 × 5 cm. Laboratory filter paper (120 g·m

−2) (Papírna Perštejn Ltd.) was used as the substrate in two layers. Sowing density was species-specific (

Table 1).

For the first few days, the plants were covered with an opaque lid. The duration of coverage depended on the species, and the plants were uncovered once germination was complete and the cotyledons began to develop. Subsequently, they were covered with transparent trays until the end of cultivation (

Table 1).

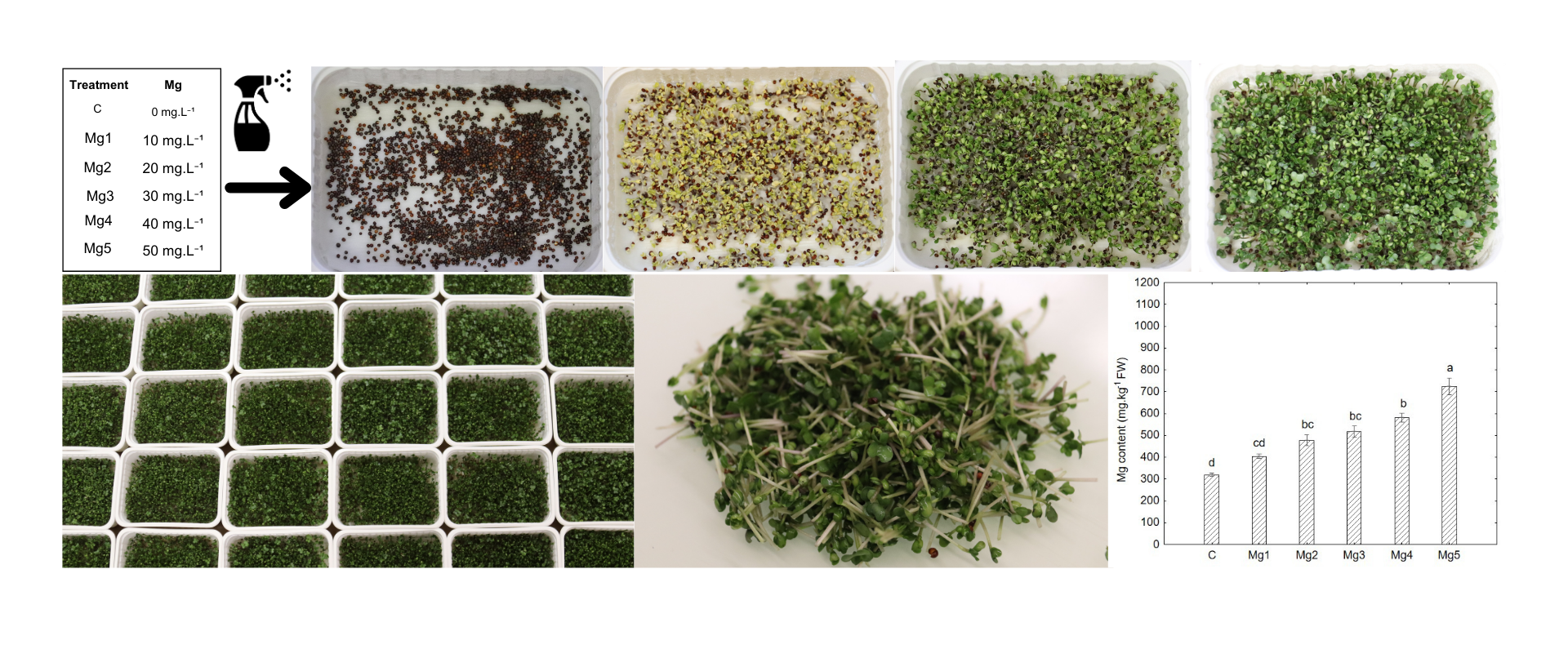

Six treatments of MgSO

4 solution were used for biofortification at concentrations of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg·L

−1, along with a control using distilled water (

Table 2). The treatments were labelled as C (control), Mg1, Mg2, Mg3, Mg4, and Mg5. Each treatment was replicated five times, resulting in a total of 180 units (6 species × 6 treatments × 5 repetitions). Three of the most representative repetitions were then selected for further analysis.

2.2. Plant Material and Sample Preparation

Before sowing, 20 ml of the treatment solution was pipetted into each growing tray. After sowing, seeds were irrigated with mechanical sprayers, and the dose applied was based on the specific needs of each species. The total solution dose was then converted to the total magnesium supply to the plants (

Table 3). For sunflower, seed coats were removed from the leaves two days before harvest. At harvest, all species had fully developed cotyledons and the first true leaves.

The above-ground plant parts were separated from the substrate at a height of a few millimetres using sharp blades. For cress, mustard, and basil, the entire plants, including roots, were harvested due to their delicate root systems. Harvested plants were weighed to determine fresh yield (g·m

−2). Samples from each repetition were used for gravimetric dry matter determination following Zbíral et al. [

24]. These samples were dried for 4 hours at 105°C in a hot air steriliser (STERIMAT 574.2, BMT Medical Technology Ltd., Czech Republic). All determinations were performed in triplicate, and dry matter content was expressed as a percentage.

2.3. Ascorbic Acid

Ascorbic acid was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) following sample preparation [

25]. A reversed-phase (RP) mode was used, with detection in the ultraviolet region. A fresh sample (5–10 g) was blended with 20–40 ml of oxalic acid solution, filtered, and transferred to a 100 ml volumetric flask. The sample was brought to volume with oxalic acid solution. From this, 20 ml was centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 10 minutes, then filtered through a 0.45 µm PVDF microfilter. The analysis was performed with RP-HPLC (ECOM, Czech Republic) using a UV-VIS detector. All samples were analysed in triplicate and expressed in mg·kg

−1.

2.4. Total Phenols and Flavonoids

A methanol extract was prepared for measuring antioxidant activity, flavonoids, and total phenols [

26]. Fresh plant material (5 g) was mixed with 20 ml of 75% methanol and extracted for 24 hours. The sample was filtered, transferred to a volumetric flask, and diluted with 75% methanol. For phenol determination, 10 ml distilled water, 1 ml extract, and 1 ml Folin-Ciocalteu reagent were added. After 5 minutes, 10 ml sodium carbonate solution was added, and the flask was filled to volume with distilled water. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm after 90 minutes. For flavonoid determination, 0.5 ml extract, 1.5 ml water, 0.2 ml sodium nitrite, and 0.2 ml aluminium chloride were added, followed by 1.5 ml sodium hydroxide and 1 ml water. After 15 minutes, absorbance was measured at 510 nm.

2.5. Antioxidant Activity

Total antioxidant capacity (TAA) was measured using the DPPH free radical method. The same methanol extract was used for analysis. Absorbance was measured at 515 nm after 30 minutes using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer.

2.6. Magnesium and Calcium Content

Water-soluble magnesium and calcium were determined by isotachophoretic analysis [

27]. One gram of dried plant material was shaken with 50 ml deionized water for 60 minutes, then filtered and brought to volume. The Mg and Ca content was measured using an IONOSEP 2003 analyzer (Recman Ltd., Czech Republic).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data processing was performed in Microsoft 365 Excel. Statistical analysis was carried out using TIBCO STATISTICA 14.0.0 (2020). One-way ANOVA was used, and significant differences were tested with the Tukey HSD test (p < 0.05). Pearson’s correlation analysis and linear regression were used to evaluate parameter relationships. Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE).

3. Results and Discussion

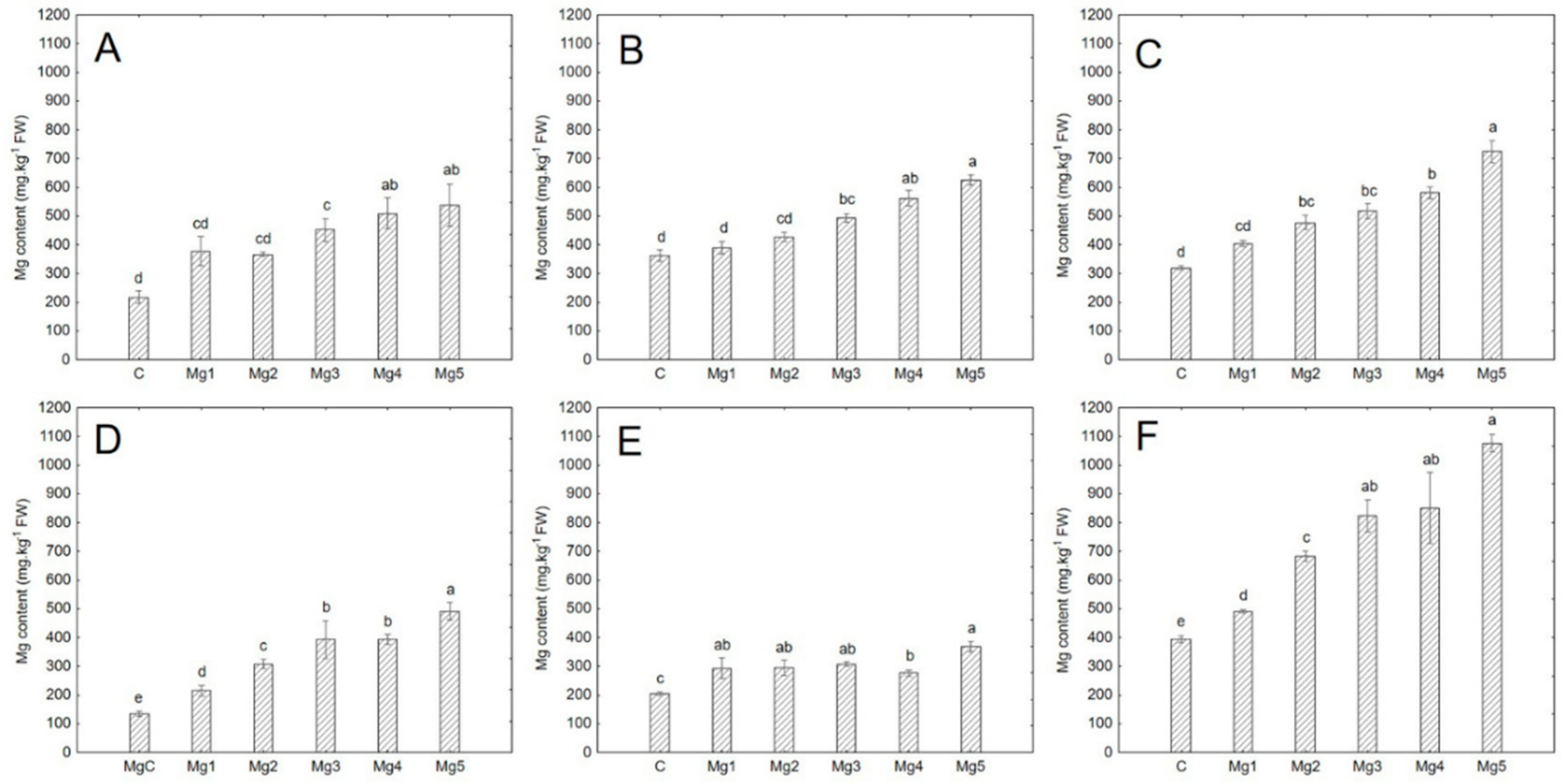

3.1. Water-Soluble Magnesium Content

Significant differences in magnesium content were observed in all six species treated with higher Mg concentrations compared to the control (p < 0.05). Some treatments showed minor variations in Mg content, such as in sunflower, where the Mg4 treatment resulted in slightly lower Mg levels than the lower concentrations, excluding the control (

Figure 1,

Table 4). This lower Mg content in sunflower (Mg4) may be due to stress, indicated by the lowest average dry matter content (8% vs. 9.9% in other treatments) (

Appendix A,

Table A1). Stress, possibly from fungal infestation, could have impaired the plant’s Mg accumulation.

In control treatments, the highest Mg content was found in cucumber, followed by mustard, broccoli, cress, sunflower, and basil (

Table 4). Xiao et al. [

7] reported an average Mg content of 510 mg·kg

−1 FW in broccoli, while mustard's values were similar to those found here (350 mg·kg

−1 FW). Di Gioia et al. [

28] noted higher Mg levels in sunflower microgreens (390 mg·kg

−1 FW). After applying 50 mg·L

−1 Mg, cucumber had the highest Mg content, followed by broccoli, mustard, cress, and basil, with sunflower having the lowest (

Table 4,

Figure 1).

The increase in Mg content at the highest concentration (Mg5) compared to the control ranged from 67% (mustard) to 262% (basil) (

Table 5). In basil, Mg increased by 262%, while sunflower showed only an 81% increase. However, the total Mg supplied through irrigation during cultivation was 5.6 mg for sunflower and 2.5 mg for basil (

Table 3). This suggests that sunflower is not suitable for Mg biofortification, likely due to higher irrigation needs and greater stress susceptibility. Broccoli showed a 137% increase in Mg content. Przybysz et al. [

29] reported that MgSO

4 concentrations of 50–300 mg·L

−1 increased Mg in broccoli sprouts by 8–83%, although this study involved sprouts rather than microgreens.

For adults, the recommended daily intake (RDI) of magnesium is 420 mg for men and 320 mg for women [

19]. To meet the RDI, men would need to consume 390 g of cucumber microgreens, while women would require 300 g. Since most people likely consume only 50% of the RDI [

30], magnesium-enriched microgreens could provide an easily accessible dietary supplement. Even 100 g of such microgreens could meet daily magnesium needs. Broccoli, which had the third-highest Mg content in the control treatment and second-highest after 50 mg·L

−1 Mg application (

Table 4), also contains relatively high levels of vitamin C, flavonoids, total phenols, and antioxidant activity (

Table 8). These could potentially be further enhanced with higher Mg concentrations (

Figure 4), making broccoli an attractive option for biofortification. Future studies should explore the effects of magnesium biofortification on different broccoli cultivars.

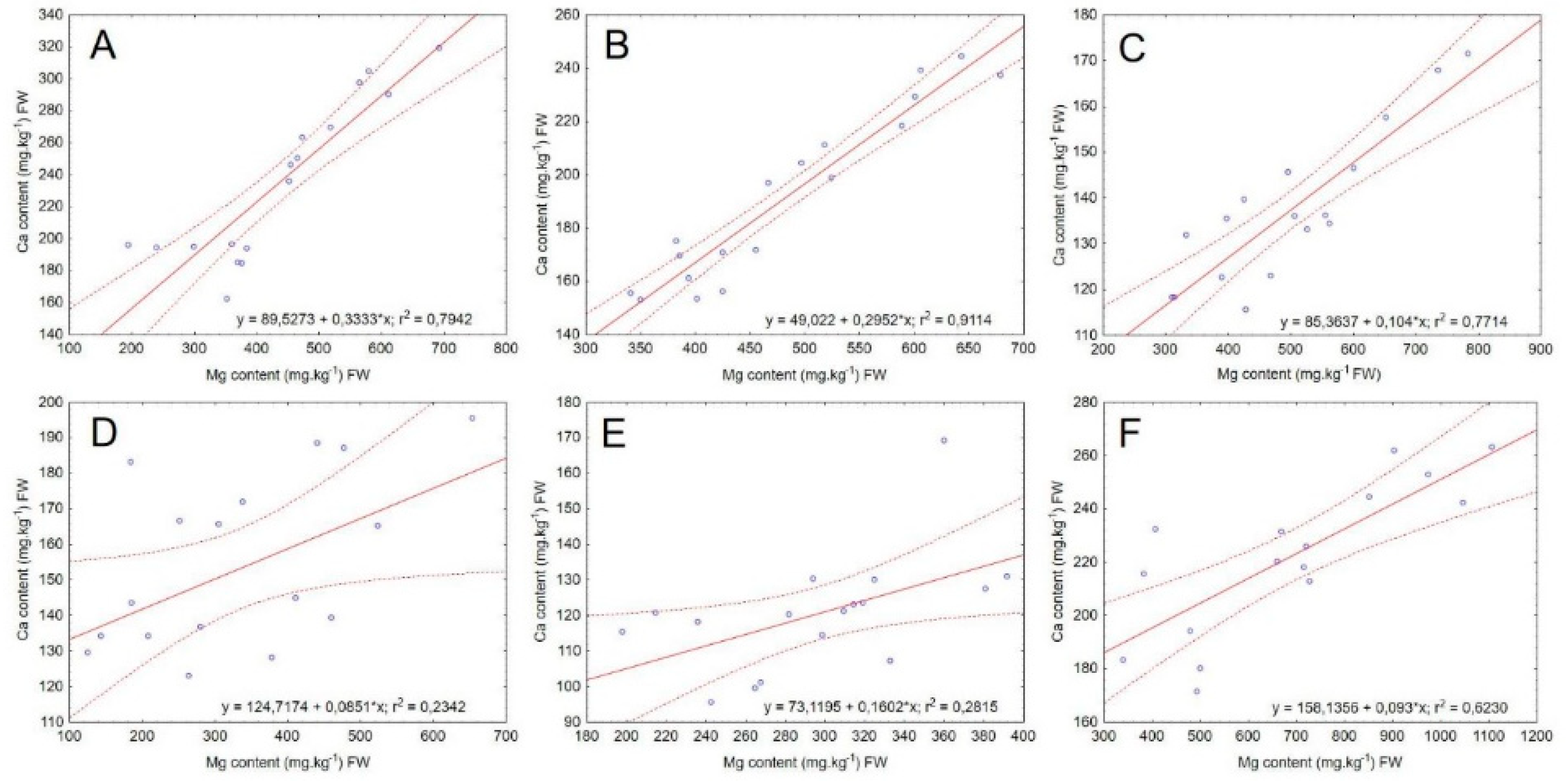

3.2. Water-Soluble Calcium Content

Among the species observed, cucumber and cress appear to have the highest water-soluble calcium content, while sunflower exhibited the lowest concentration of this element (

Table 6). No significant effect of MgSO

4 application on calcium content was recorded for basil and sunflower. In contrast, an increase (p < 0.05) in calcium content was evident for mustard, broccoli, and cucumber with increasing concentrations of magnesium. In cress, the water-soluble calcium content increased significantly across all treatments, except for Mg2, which showed the lowest calcium content among the evaluated treatments. Compared to the control treatment, the Mg5 treatment resulted in an increase in calcium content of 49% (mustard), 27% (cucumber), 24% (broccoli), and 38% (cress) (

Table 6).

3.2.1. Ca/Mg Ratio

Based on the results (

Table 6), each species of microgreens appears to respond differently to increasing levels of magnesium in plants (

Figure 2). Mustard, cucumber, broccoli, and cress showed a slight increase in calcium content, while the other species either exhibited negligible changes or no significant effect.

The limited impact of Mg on Ca content in the plants may be related to the short cultivation period of the microgreens. Calcium (Ca

2+) and magnesium (Mg

2+) are the two most abundant divalent cations in plants, and they can interact antagonistically. Specifically, they compete for the same binding sites on enzymatic and transport proteins [

31,

32]. However, a proposed hypothesis suggests that high levels of external Mg

2+ may cause a transient increase in cytosolic Ca

2+ within plant cells [

33]. This mechanism could explain the slight increase in calcium content observed in some species, though further research is needed to confirm this.

3.3. Dry Matter

Regardless of the treatment, basil had the highest average dry matter content, while cress had the lowest. The remaining species (cucumber, broccoli, sunflower, and mustard) had similar dry matter content (

Table 8). In mustard, the Mg3, Mg4, and Mg5 treatments resulted in significantly higher dry matter content (p < 0.05) compared to the lower concentrations and control (

Table A1). Broccoli's dry matter content averaged 9.2% (excluding the Mg5 treatment), which is higher than the 7.9% reported by Xiao et al. [

7]. The higher dry matter content in this study may be attributed to differences in growing conditions or cultivar, as well as a one-day longer cultivation period. The average dry matter content in basil (12.3%) aligns with other studies, where green basil’s dry matter content ranged from 10.1 to 11.9% [

16]. A recent study on the biofortification of broccoli microgreens with ascorbic acid showed a correlation between higher ascorbic acid doses and dry matter content, with the control having an average of 7.5% dry matter, which increased to 8.9% with 0.25% ascorbic acid [

34]. While no significant effect of Mg on dry matter content in broccoli was observed in this study, the average dry matter content was still higher, and the Mg5 treatment showed slightly higher dry matter content compared to the lower concentrations and control (

Table A1), though these results were not statistically significant (p > 0.05).

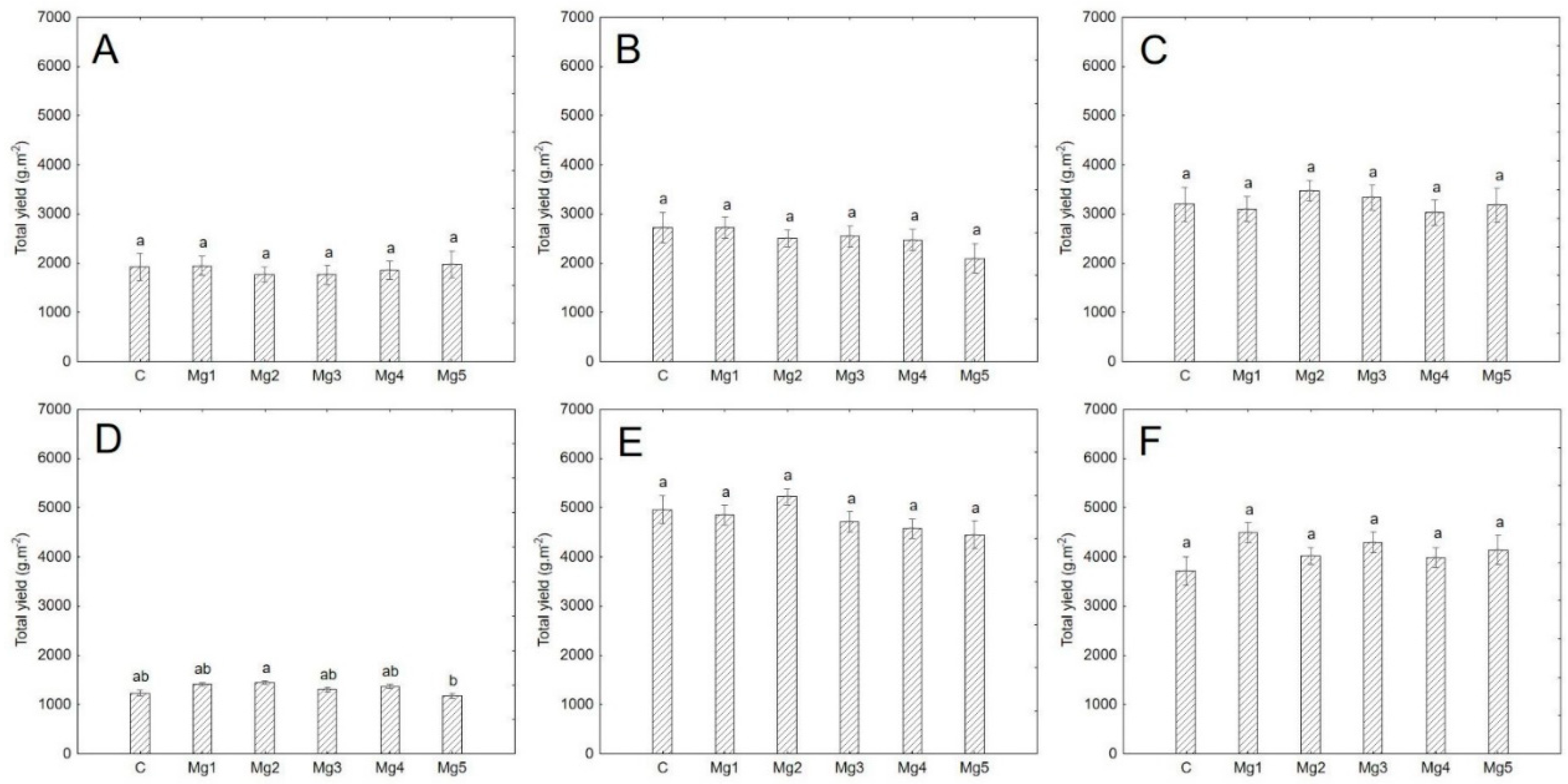

3.4. Yield

In this study, magnesium concentrations did not significantly affect the yield of any species (p > 0.05) (

Table A2,

Figure 3). The average fresh yield (including roots) per gram of seeds, regardless of the treatment, was highest for cucumber and lowest for sunflower (

Table 7). When considering yield per area, sunflower had the highest average yield, while basil had the lowest (

Table 7). For broccoli, cucumber, and sunflower, the edible parts and roots were harvested and weighed separately.

Differences in yield among species are attributed to their physiological characteristics, sowing density, and cultivation duration. Magnesium biofortification did not show any significant differences in biomass yield compared to the control treatments. It seems that the application of MgSO

4, along with the high electrical conductivity, did not induce toxicity symptoms in the plants. These findings align with a study on the effect of magnesium enrichment in plant sprouts, which also reported negligible impacts on yield [

29].

Di Gioia et al. [

28] examined the yield of 17 microgreen species, including broccoli, basil, cress, and sunflower, which were also part of this study. These plants were cultivated in a soilless system using a natural fiber mat as the growing substrate. In their study, the reported yield of broccoli was 1461 g·m

−2, whereas our study achieved a higher yield of 1925 g·m

−2, excluding root mass (

Table 7). Notably, our experimental conditions included a sowing density of 13.7 seeds·cm

−2, compared to their lower density of 2.7 seeds·cm

−2. Additionally, our cultivation period was 10 days, while theirs extended to 11 days (

Table 1;

Table 7). Sunflower yields of 1656 g·m

−2 have been documented at a sowing density of 1 seed/cm

2 over 10 days. In our study, we achieved a higher yield of 2342 g·m

−2 (excluding roots) with a density of 1.8 seeds/cm

2 over 9 days (

Table 1;

Table 7). Vrkić et al. [

35] reported a yield range of 1219 to 1590 g·m

−2 for mustard, depending on the LED lighting intensity, with a sowing density of 5 seeds·cm

−2 and an 8-day cultivation cycle. In contrast, our study achieved a significantly higher yield of 2547 g·m

−2 at a sowing density of 7.3 seeds·cm

−2 over 6 days (

Table 1;

Table 7). The high sowing density in this study may not always correlate with increased yield. Variations in results may also arise from differences in harvesting methods (e.g., harvesting the entire plant with roots, precision of above-ground part harvesting, or time since the last watering, affecting turgor). Future studies should focus on optimizing the sowing density-to-yield ratio. Additionally, seed quality, cultivar choice, and cultivation conditions should be considered.

3.5. Ascorbic Acid

Vitamin C content varied significantly across species. Significant differences within the treatments were observed only in broccoli, where the Mg5 treatment resulted in significantly higher values (p < 0.05) compared to the other treatments (

Table A1,

Figure 4). Regardless of the concentration used, basil had the lowest ascorbic acid content, while broccoli had the highest (excluding the Mg5 treatment) (

Table 8). The average ascorbic acid content in broccoli, excluding the Mg5 treatment, was 748.4 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table 8), while at the highest magnesium concentration (50 mg·L

−1), it increased to 883 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table A1). Koh et al. [

36] analysed 80 mature commercial samples of broccoli and found an average vitamin C content of 872 mg·kg

−1 FW. For broccoli microgreens, values range from 791 mg·kg

−1 FW [

8] to 893 mg·kg

−1 FW [

37].

While lower magnesium sulfate concentrations (up to 40 mg·L

−1) did not significantly affect ascorbic acid content compared to the control, the highest concentration caused a noticeable increase in ascorbic acid levels in broccoli. Further studies are needed to confirm these findings, and it would be beneficial to test even higher concentrations than those used in this study to explore why the ascorbic acid content was not significantly affected at the second-highest magnesium sulfate concentration. The application of magnesium sulfate at certain concentrations might influence ascorbate oxidase activity, which could be related to the increase in ascorbic acid content in plants [

38,

39]. The effect of magnesium on ascorbic acid content appears species-dependent and may also depend on the form of magnesium used. Borowski et al. [

40] found that foliar application of magnesium salts negatively affected ascorbic acid content in spinach. Yadav et al. [

41] reported higher ascorbic acid content in cucumber microgreens compared to mature cucumbers. The literature shows varying values for ascorbic acid concentrations in cucumbers, indicating cultivar dependency. However, according to the USDA [

42], the average ascorbic acid content in mature cucumber is 28 mg·kg

−1 FW. In this study, cucumber had relatively low ascorbic acid content compared to other species, yet the average value of 75.78 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table 8) was still higher than that of mature cucumber fruits. The recommended daily intake of vitamin C is 90 mg for men and 75 mg for women [

43]. Given the highest average vitamin C values found in this study (883 mg·kg

−1 for broccoli), daily consumption of 102 grams of broccoli microgreens for men and 85 grams for women would meet the recommended daily intake. Future studies should also consider the impact of different broccoli cultivars on vitamin C content.

3.6. Total Phenolic Content

No significant differences in total phenolic content were observed among the treatments, except in broccoli, where the Mg5 treatment led to significantly higher total phenol content (p < 0.05) (

Table A1,

Figure 4). Regardless of treatment, cucumber had the lowest average total phenolic content, while mustard had the highest (

Table 8). The results suggest that mustard is the richest source of total phenols, with species from the

Brassicaceae family generally being good sources of phenolic compounds. Mustard seeds are well known for their high phenolic content [

44], and this study supports the idea that young mustard plants have a similar phenolic profile. In broccoli, the Mg5 treatment resulted in a total phenol content of 1884 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table A1), which was significantly higher than in the other treatments (

Table 8). Xuan et al. [

45] reported higher concentrations of total phenols in rice seedlings when magnesium sulfate was applied compared to the control.

3.7. Flavonoids

Flavonoid content showed significant variability between species (

Table 8). Similar to ascorbic acid, broccoli in the Mg5 treatment exhibited significantly higher flavonoid content (p < 0.05) compared to the control and lower concentration treatments (

Table A1,

Figure 4). While the other treatments and control averaged 354 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table 8), the Mg5 treatment had an average flavonoid content of 479 mg·kg

−1 FW (

Table A1). The other species did not show significant changes in flavonoid content with varying magnesium concentrations. Ciscomani-Larios et al. [

46] reported a positive effect of MgSO

4 application on flavonoid content in green beans, and similarly, magnesium sulfate increased flavonoid content in rice seedlings [

45]. However, these studies focused on more advanced developmental stages of plants, and it’s possible that a longer cultivation period would influence the flavonoid and total phenol content in the species examined in this study.

Cucumber showed the lowest average flavonoid content across all treatments, while basil had the highest, indicating that basil is a good source of flavonoids, as confirmed by other studies [

47,

48]. In this study, basil stood out as the richest source of flavonoids among the species investigated, although its total phenol content was lower compared to other species. In contrast, mustard had an average flavonoid content, but its total phenol content was more than three times higher than that of basil. This could be due to genotypic variability or differences in the cultivation period.

3.8. Antioxidant Activity

While antioxidant activity was not significantly influenced by the treatments overall, significant differences were observed in broccoli, where the Mg5 treatment had significantly higher antioxidant activity (p < 0.05) compared to the other treatments (

Table A1,

Figure 4). Broccoli exhibited the highest average antioxidant activity, even when excluding the Mg5 treatment, while cucumber had the lowest values (

Table 8). In fact, antioxidant activity in broccoli was 553% higher compared to cucumber. Przybysz et al. [

29] reported that MgSO

4 concentrations between 50 and 300 mg·L

−1 positively affected antioxidant activity in broccoli sprouts, though in this study, these findings were only partially confirmed (for the Mg5 treatment). This study found broccoli to have the highest antioxidant activity, consistent with other research showing that broccoli microgreens are considered an excellent source of antioxidants [

49,

50]. Additionally, no toxic effects of magnesium on antioxidant activity or other substances in the plants were observed.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that MgSO4 application effectively increased magnesium (Mg) content in the plants, with cucumber and broccoli showing the highest potential for Mg biofortification. Notably, no adverse effects were observed on yield or the levels of secondary metabolites such as antioxidants, phenols, flavonoids, and vitamin C. In broccoli, the highest Mg concentration (50 mg·L−1) significantly boosted total phenols, flavonoids, ascorbic acid, and antioxidant activity. The study revealed substantial interspecies variability in both Mg uptake and secondary metabolite content, emphasizing the need for a species-specific approach to biofortification. This research, one of the first to focus on magnesium biofortification in microgreens, provides valuable insights into their potential as functional foods. Future studies should explore the impact of Mg biofortification on bioactive compounds, like glucosinolates in Brassicaceae species, and examine interactions between Mg and other minerals, such as sulphur. These efforts could help optimize microgreen biofortification, enhancing their role as healthy dietary supplements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.F. and A.J.; methodology, A.J.; software, R.P.; validation, A.J., R.P.; formal analysis, A.F.; investigation, A.F. and A.J.; resources, A.F.; data curation, A.J.; writing—original draft preparation, A.F.; writing—review and editing, R.P.; visualization, A.F.; supervision, A.J. and R.P.; project administration, R.P.; funding acquisition, R.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Experiments were supported by project OP VVV CZ.0 2.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_017/0002334. Research infrastructure for young scientists financed from structural funds of EU and Ministry of Education of the Czech Republic.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Analysed parameters in other species.

Table A1.

Analysed parameters in other species.

| Variant |

Vitamin C [mg·kg−1 FW] |

TAC DPPH [mg·kg−1 FW] |

Flavonoids [mg·kg−1 FW] |

Total phenols [mg·kg−1 FW] |

Dry matter [%] |

| Cress |

| C |

197.3 ±33.8ab |

845.3 ±62.9a |

289.9 ±2.1bc |

1624.0 ±57.2cd |

7.8 ±0.2bc |

| Mg1 |

193.6 ±19.3bc |

886.2 ±81.7a |

313.2 ±21.6ab |

1829.3 ±260.8abc |

8.4 ±0.7ab |

| Mg2 |

160.0 ±6.1cd |

856.8 ±47.2a |

278.9 ±8.7bc |

1885.1 ±82.4abc |

6.9 ±0.2d |

| Mg3 |

169.4 ±13.4bc |

843.8 ±38.2a |

303.6 ±8.8ab |

1893.4 ±97.0abc |

7.3 ±0.5cd |

| Mg4 |

159.7 ±16.1cd |

952.9 ±83.9a |

329.6 ±25.1ab |

2128.2 ±230.6abc |

8.2 ±0.5ab |

| Mg5 |

136.0 ±5.8e |

922.5 ±62.2a |

310.7 ±16.1ab |

2003.0 ±123.7abc |

8.8 ±0.7ab |

| Mustard |

| C |

297.4 ±5.0bc |

889.5 ±77.3bc |

394.3 ±14.0ab |

3431.8 ±224.7c |

8.7 ±0.4d |

| Mg1 |

285.8 ±16.7bc |

885.8 ±84.3bc |

355.9 ±28.9ab |

3919.3 ±148.4a |

8.8 ±0.4d |

| Mg2 |

304.6 ±23.5ab |

827.4 ±45.9c |

309.6 ±6.6cd |

2974.2 ±362.4c |

8.9 ±0.2d |

| Mg3 |

321.6 ±5.9ab |

936.7 ±71.4bc |

308.3 ±19.3cd |

3275.4 ±167.7c |

9.8 ±0.1c |

| Mg4 |

309.7 ±9.9ab |

962.5 ±28.9ab |

318.1 ±8.2cd |

3499.8 ±100.7c |

10.8 ±0.6ab |

| Mg5 |

345.1 ±31.3a |

938.6 ±18.2ab |

356.8 ±24.3ab |

3730.3 ±47.1b |

10.5 ±0.1ab |

| Broccoli |

| C |

751.3 ±31.9b |

1008.5 ±19.5b |

360.4 ±23.2b |

1699.9 ±3.5b |

8.8 ±0.3a |

| Mg1 |

747.3 ±10.8b |

991.8 ±21.9b |

345.5 ±3.9b |

1673.9 ±7.0b |

9.3 ±0.3a |

| Mg2 |

741.3 ±13.8b |

1010.5 ±21.5b |

352.9 ±3.6b |

1694.0 ±42.2b |

9.0 ±0.4a |

| Mg3 |

744.8 ±3.8b |

993.2 ±22.1b |

361.8 ±6.9b |

1752.4 ±24.6b |

9.1 ±0.5a |

| Mg4 |

757.5 ±6.4b |

985.7 ±17.1b |

349.3 ±17.0b |

1717.2 ±26.7b |

9.6 ±0.5a |

| Mg5 |

882.5 ±13.3a |

1123.3 ±23.5a |

478.5 ±13.5a |

1884.0 ±16.5a |

9.8 ±0.2a |

| Basil |

| C |

44.9 ±2.7ab |

551.2 ±86.4bc |

474.8 ±107.9bcd |

1041.9 ±120.0ab |

11.2 ±1.2a |

| Mg1 |

43.1 ±5.8ab |

618.4 ±26.7bc |

575.1 ±50.3bc |

1114.6 ±30.7ab |

11.0 ±0.7a |

| Mg2 |

37.2 ±5.2bc |

478.0 ±5.7cd |

457.7 ±15.4cd |

1016.5 ±121.4ab |

12.3 ±0.6a |

| Mg3 |

39.1 ±1.3bc |

669.7 ±12.2a |

662.4 ±10.7a |

1135.6 ±7.3ab |

12.7 ±1.6a |

| Mg4 |

44.4 ±3.2ab |

524.2 ±38.5bc |

535.1 ±21.8bc |

942.2 ±114.4bc |

10.7 ±0.7a |

| Mg5 |

51.3 ±4.2a |

478.0 ±53.5cd |

378.3 ±31.1de |

785.9 ±45.6d |

13.7 ±1.3a |

| Sunflower |

| C |

56.4 ±3.4ab |

430.3 ±9.7ab |

481.5 ±24.1a |

1251.10 ±129.2ab |

9.8 ±0.3a |

| Mg1 |

47.2 ±5.7cd |

375.5 ±81.9ab |

415.4 ±50.5a |

872.8 ±70.0bc |

10.4 ±1.2a |

| Mg2 |

41.6 ±2.3e |

328.8 ±54.0cd |

402.6 ±45.3a |

849.3 ±77.9bc |

9.2 ±0.8a |

| Mg3 |

50.5 ±2.1cd |

349.1 ±26.5cd |

382.4 ±46.9a |

906.0 ±61.3bc |

9.9 ±0.4a |

| Mg4 |

51.6 ±4.5ab |

471.1 ±132.0ab |

390.6 ±74.1a |

1092.3 ±191.0ab |

8.0 ±0.3b |

| Mg5 |

62.0 ±6.4a |

564.5 ±146.5ab |

478.9 ±84.3a |

1054.7 ±180.7ab |

10.4 ±0.6a |

| Cucumber |

| C |

78.8 ±5.4ab |

161.1 ±14.6ab |

135.7 ±8.8cd |

703.5 ±56.1ab |

9.9 ±0.5a |

| Mg1 |

66.1 ±1.6c |

154.5 ±7.7bc |

144.3 ±11.5cd |

650.5 ±14.6ab |

8.2 ±0.1b |

| Mg2 |

73.5 ±6.6bc |

180.9 ±8.4ab |

145.4 ±6.7cd |

694.5 ±26.9ab |

9.2 ±0.1a |

| Mg3 |

70.5 ±5.4bc |

127.1 ±9.9de |

137.5 ±11.7ab |

657.0 ±34.3ab |

9.0 ±0.4a |

| Mg4 |

81.2 ±7.1ab |

144.9 ±4.9bc |

152.2 ±12.3bc |

612.9 ±28.3bc |

8.9 ±0.6a |

| Mg5 |

83.7 ±10.7ab |

123.2 ±0.9de |

169.3 ±9.9cd |

620.6 ±17.1bc |

9.7 ±0.4a |

Table A2.

Yield by treatment.

Table A2.

Yield by treatment.

| Treatment |

Cress |

Mustard |

Broccoli |

Basil |

Sunflower |

Cucumber |

| C |

1932 ±5a |

2400 ±202a |

3183 ±86a |

1265 ±54ab |

5041 ±84a |

3975 ±259a |

| Mg1 |

1949 ±111a |

2561 ±131a |

3275 ±85a |

1395 ±46ab |

5021 ±168a |

4285 ±213a |

| Mg2 |

1775 ±104a |

2624 ±89a |

3446 ±141a |

1324 ±112a |

5224 ±203a |

4017 ±254a |

| Mg3 |

1691 ±82a |

2535 ±46a |

3399 ±99a |

1369 ±43ab |

4674 ±113a |

4241 ±104a |

| Mg4 |

1714 ±254a |

2581 ±148a |

3180 ±123a |

1317 ±58ab |

4657 ±141a |

3987 ±45a |

| Mg5 |

1858 ±57a |

2515 ±140a |

3069 ±70a |

1237 ±58b |

4610 ±82a |

4078 ±69a |

References

- Paraschivu, M.; Cotuna, O.; Sărățeanu, V.; Durău, C. C.; Păunescu, R. A. Microgreens—Current Status, Global Market Trends and Forward Statements. Sci. Pap. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2021, 21(3). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Lester, G. E.; Park, E.; Saftner, R. A.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Q. Evaluation and Correlation of Sensory Attributes and Chemical Compositions of Emerging Fresh Produce: Microgreens. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2015, 110, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, F.; El-Nakhel, C.; Raimondo, M.; Kyriacou, M. C.; Cembalo, L.; De Pascale, S.; Rouphael, Y. Sensory Attributes and Consumer Acceptability of 12 Microgreens Species. Agronomy 2020, 10(7), 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viltres-Portales, M.; Sánchez-Martín, M. J.; Llugany, M.; Boada, R.; Valiente, M. Selenium Biofortification of Microgreens: Influence on Phytochemicals, Pigments and Nutrients. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Sharma, T.; Singh, S. P.; Bhardwaj, A.; Srivastava, D.; Kumar, R. Prospects of Microgreens as Budding Living Functional Food: Breeding and Biofortification through OMICS and Other Approaches for Nutritional Security. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1053810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzi, A.; Orlandini, A.; Bulgari, R.; Ferrante, A.; Bruschi, P. Antioxidant and Mineral Composition of Three Wild Leafy Species: A Comparison between Microgreens and Baby Greens. Foods 2019, 8(10), 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Codling, E. E.; Luo, Y.; Nou, X.; Lester, G. E.; Wang, Q. Microgreens of Brassicaceae: Mineral Composition and Content of 30 Varieties. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2016, 49, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowitcharoen, L.; Phornvillay, S.; Lekkham, P.; Pongprasert, N.; Srilaong, V. Bioactive Composition and Nutritional Profile of Microgreens Cultivated in Thailand. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11(17), 7981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, S.; Baek, M. W.; An, K. S.; Choi, H. R.; Lee, J. H.; Hong, J. S.; Jeong, C. S. Radish Microgreens Produced without Substrate in a Vertical Multi-Layered Growing Unit Are Rich in Nutritional Metabolites. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1236055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeb, E.; Hefferon, K. Crop Biofortification and Food Security. In Plant Nutrition and Food Security in the Era of Climate Change; Academic Press, 2022; pp. 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, S. S.; Sharma, V.; Shukla, A. K.; Verma, V.; Kaur, M.; Shivay, Y. S.; Hossain, A. Biofortification—A Frontier Novel Approach to Enrich Micronutrients in Field Crops to Encounter the Nutritional Security. Molecules 2022, 27(4), 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A. K.; Seth, A.; Kumar, V.; Datta, A. Agronomic Biofortification of Wheat through Proper Fertilizer Management to Alleviate Zinc Malnutrition: A Review. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 2023, 54(2), 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, M.; D’Imperio, M.; Maggi, S.; Serio, F. Soilless Biofortification, Bioaccessibility, and Bioavailability: Signposts on the Path to Personalized Nutrition. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 966018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Imperio, M.; Parente, A.; Montesano, F. F.; Renna, M.; Logrieco, A. F.; Serio, F. Boron Biofortification of Portulaca oleracea L. through Soilless Cultivation for a New Tailored Crop. Agronomy 2020, 10(7), 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puccinelli, M.; Malorgio, F.; Rosellini, I.; Pezzarossa, B. Production of Selenium-Biofortified Microgreens from Selenium-Enriched Seeds of Basil. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99(12), 5601–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannico, A.; El-Nakhel, C.; Graziani, G.; Kyriacou, M. C.; Giordano, M.; Soteriou, G. A.; Rouphael, Y. Selenium Biofortification Impacts the Nutritive Value, Polyphenolic Content, and Bioactive Constitution of Variable Microgreens Genotypes. Antioxidants 2020, 9(4), 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavan, M.; Wee, B.; Fuentes, S.; Pang, A.; Brodie, G.; Viejo, C. G.; Gupta, D. Biofortification of Kale Microgreens with Selenate-Selenium Using Two Delivery Methods: Selenium-Rich Soilless Medium and Foliar Application. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 323, 112522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikhi, H.; Nicola, S.; Delshad, M.; Bulgari, R. Sodium Selenate Biofortification, through Seed Priming, on Dill Microgreens Grown in Two Different Cultivation Systems. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1474420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation of Dietary Reference Intakes. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Vitamin D, and Fluoride; National Academies Press (US), 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, D.; Cappadone, C.; Farruggia, G.; Prata, C. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13(4), 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiNicolantonio, J. J.; O’Keefe, J. H.; Wilson, W. Subclinical Magnesium Deficiency: A Principal Driver of Cardiovascular Disease and a Public Health Crisis. Open Heart 2018, 5, e000668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louzada, M. L. C.; Martins, A. P. B.; Canella, D. S.; Baraldi, L. G.; Levy, R. B.; Claro, R. M.; Monteiro, C. A. Impact of Ultra-Processed Foods on Micronutrient Content in the Brazilian Diet. Rev. Saude Publica 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, D. P.; Sharma, R.; Bansal, D. D. Implications of Magnesium Deficiency in Type 2 Diabetes: A Review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2010, 134, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbíral, J. Analýza Rostlinného Materiálu: Jednotné Pracovní Postupy; Ústřední kontrolní a zkušební ústav zemědělský: Brno, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arya, S. P.; Mahajan, M.; Jain, P. Non-Spectrophotometric Methods for the Determination of Vitamin C. Anal. Chim. Acta 2000, 417, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zloch, Z.; Čelakovský, J.; Aujezdská, A. Stanovení Obsahu Polyfenolů a Celkové Antioxidační Kapacity v Potravinách Rostlinného Původu; Ústav Hygieny Lékařské Fakulty UK: Plzeň, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Blatny, P.; Kvasnicka, F.; Loucka, R.; Safarova, H. Determination of Ammonium, Calcium, Magnesium, and Potassium in Silage by Capillary Isotachophoresis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gioia, F.; Hong, J. C.; Pisani, C.; Petropoulos, S. A.; Bai, J.; Rosskopf, E. N. Yield Performance, Mineral Profile, and Nitrate Content in a Selection of Seventeen Microgreen Species. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1220691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybysz, A.; Wrochna, M.; Małecka-Przybysz, M.; Gawrońska, H.; Gawroński, S. W. The Effects of Mg Enrichment of Vegetable Sprouts on Mg Concentration, Yield and ROS Generation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 3469–3475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, F. H. Magnesium Deficiency and Increased Inflammation: Current Perspectives. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Chen, S.; Hussain, N.; Cong, Y.; Liang, Z.; Chen, K. Magnesium Stress Signaling in Plant: Just a Beginning. Plant Signal. Behav. 2015, 10, e992287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. J.; Luan, S. Regulation of Calcium and Magnesium Homeostasis in Plants: From Transporters to Signaling Network. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2017, 39, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R. J.; Zhao, F. G.; Garcia, V. J.; Kleist, T. J.; Yang, L.; Zhang, H. X.; Luan, S. Tonoplast CBL–CIPK Calcium Signaling Network Regulates Magnesium Homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2015, 112, 3134–3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathi, S.; Laza, H.; Singh, S.; Thompson, L.; Li, W.; Simpson, C. Vitamin C Biofortification of Broccoli Microgreens and Resulting Effects on Nutrient Composition. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1145992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrkić, R.; Benko, B.; Fabek Uher, S.; Šic Žlabur, J. Yield and Morphology of Mustard and Garden Cress Microgreens Grown under LED Supplemental Lighting. In IX South-Eastern Europe Symposium on Vegetables and Potatoes 2023, 1391, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E.; Wimalasiri, K. M. S.; Chassy, A. W.; Mitchell, A. E. Content of Ascorbic Acid, Quercetin, Kaempferol and Total Phenolics in Commercial Broccoli. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2009, 22, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Rausch, S. R.; Luo, Y.; Sun, J.; Yu, L.; Wang, Q.; Stommel, J. R. Microgreens of Brassicaceae: Genetic Diversity of Phytochemical Concentrations and Antioxidant Capacity. LWT 2019, 101, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokul, D.; Poonkodi, P.; Angayarkanni, A. Effect of Inorganic Fertilizers, Organic Manures, Biofertilizers and Magnesium Sulfate on Yield Attributes, Yield and Quality of Chilli. Int. J. Anal. Exp. Modal Anal. 2021, 13, 779–783. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A. A.; Chattoo, M. A.; Sheemar, G.; Rashid, R. Growth, Yield and Fruit Quality of Sweet Pepper Hybrid SH-SP-5 (Capsicum annuum L.) as Affected by Integration of Inorganic Fertilizers and Organic Manures (FYM). J. Agric. Technol. 2011, 7, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Borowski, E.; Michalek, S. The Effect of Foliar Nutrition of Spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) with Magnesium Salts and Urea on Gas Exchange, Leaf Yield and Quality. Acta Agrobot. 2010, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, L. P.; Koley, T. K.; Tripathi, A.; Singh, S. Antioxidant Potentiality and Mineral Content of Summer Season Leafy Greens: Comparison at Mature and Microgreen Stages Using Chemometric. Agric. Res. 2019, 8, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. FoodData Central: Cucumber, Raw. Available online: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/food-details/168409/nutrients (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Naidu, K. A. Vitamin C in Human Health and Disease Is Still a Mystery? An Overview. Nutr. J. 2003, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.; Nandasiri, R.; Fadairo, O.; Eskin, N. M. Phenolics of Mustard Seeds: A Review on Composition, Processing Effect and Their Bioactivities. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2024, 101, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, T. D.; Huong, C. T.; Quan, N. V.; Anh, L. H.; Khanh, T. D.; Rayee, R. Improvement of Salinity Tolerance in Rice Seedlings by Exogenous Magnesium Sulfate Application. Soil Syst. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciscomani-Larios, J. P.; Sánchez-Chávez, E.; Jacobo-Cuellar, J. L.; Sáenz-Hidalgo, H. K.; Orduño-Cruz, N.; Cruz-Alvarez, O.; Ávila-Quezada, G. D. Biofortification Efficiency with Magnesium Salts on the Increase of Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity in Snap Beans. Ciênc. Rural 2021, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V. T.; Nguyen, N. Q.; Thi, N. Q. N.; Thi, C. Q. N.; Truc, T. T.; Nghi, P. T. B. Studies on Chemical, Polyphenol Content, Flavonoid Content, and Antioxidant Activity of Sweet Basil Leaves (Ocimum basilicum L.). IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1092, 012083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Ashkani, S.; Baghdadi, A.; Pazoki, A.; Jaafar, H. Z.; Rahmat, A. Improvement in Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids Production and Pharmaceutical Quality of Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) by Ultraviolet-B Irradiation. Molecules 2016, 21, 1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Bella, M. C.; Nicolosi, E.; Ballistreri, G.; Fabroni, S.; Gentile, C. Morphometric Characteristics, Polyphenols and Ascorbic Acid Variation in Brassica oleracea L. Novel Foods: Sprouts, Microgreens and Baby Leaves. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, A.; Stoleru, V.; Filimon, R. V.; Padureanu, S.; Chelariu, E. L.; Biliaderis, C. G. Influence of Sodium and Maturity Stage on the Antioxidant Properties of Cauliflower and Broccoli Sprouts. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj-Napoca 2017, 45, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).