Introduction

Porcine ear skin is widely regarded as one of the most reliable surrogate models for human skin in in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) because of their close histological and physiological similarities. Both species share comparable dermal–epidermal thickness ratios, lipid and protein composition, vascular distribution, sparse hair density, and wound healing mechanisms based on re-epithelialization [

1,

2]. In addition to these biological similarities, porcine skin is far more accessible and cost-effective than human tissue, as it can be readily sourced from the food industry. These advantages have led to its widespread adoption for preclinical permeation and formulation development studies.

Despite its extensive use, however, the procurement, handling, and preparation of porcine skin — all crucial steps that directly affect experimental outcomes — remain largely unstandardized. Aside from one stepwise protocol proposed by Silva et al., which emphasizes sourcing ears from a reliable slaughterhouse, minimizing transport time, and preventing physical or pathological damage, few efforts have been made to establish best practices for skin selection and use [

3]. Most commonly, porcine ears are obtained from abattoirs or slaughterhouses, research animals, farms, or local butcher shops [

1,

3,

4]. However, ears sourced from the food industry often undergo processing steps such as scalding, dehairing, and skinning — procedures intended to ensure food safety, but which can cause substantial damage to the skin surface, including disruption of the stratum corneum and viable epidermis, the primary barriers to water loss, xenobiotic entry, and drug permeation.

A review of the literature reveals that many IVPT studies fail to disclose critical details regarding skin source, anatomical site, condition (e.g., scalded vs. unscalded), or handling practices. Regulatory and industry guidelines provide only limited direction: the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guideline allows the use of non-viable skin provided barrier integrity is demonstrated, but does not address sourcing [

5], and the Colipa Guidelines recommend “fresh, unboiled” porcine skin without clarifying whether “unboiled” also means “unscalded” [

4,

6]. Because scalding is part of routine carcass cleaning, even “fresh” samples may have already lost critical barrier structures.

This ambiguity is reflected in experimental outcomes. For example, one study examining the permeation of a vitamin C derivative through full-thickness porcine skin reported poor penetration, high retention (~20%) within the tissue, and incomplete recovery (<85%) from multiple solvent systems, but failed to specify skin source or quality [

7]. Other reports describe the use of “fresh” porcine skin from local slaughterhouses [

8,

9], but this term typically refers only to samples that have not been frozen [

10] — not necessarily those that are unprocessed or structurally intact. The absence of such details makes it difficult to assess the reliability and reproducibility of permeation results across studies. Standardized reporting of skin source, anatomical site, preparation methods, and condition is essential for improving data quality and ensuring that IVPT outcomes are physiologically relevant.

The therapeutic landscape also underscores the need for accurate permeation models. Metformin (Met), an FDA-approved oral antidiabetic agent, has shown promising potential in topical applications, where transdermal delivery offers several advantages: bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism, reducing gastrointestinal side effects, providing sustained local release, and enabling non-invasive administration. Our laboratory has developed a topical metformin lotion containing permeation enhancers such as glycerol and propylene glycol as a potential treatment for tendon injuries. Topical Met has also been explored in other indications, including acne, psoriasis, alopecia, and wound healing [

11].

In this study, we systematically investigated how pork harvest processing affects metformin permeation across porcine ear skin. We compared commercially sourced ears from butcher shops — which undergo standard food-industry processing — with freshly harvested, unprocessed ears obtained directly from a slaughterhouse. Through this comparison, we aim to highlight how sourcing and preparation profoundly influence barrier integrity and permeation outcomes, and to underscore the need for rigorous standardization in the use of porcine skin for IVPT studies.

Results

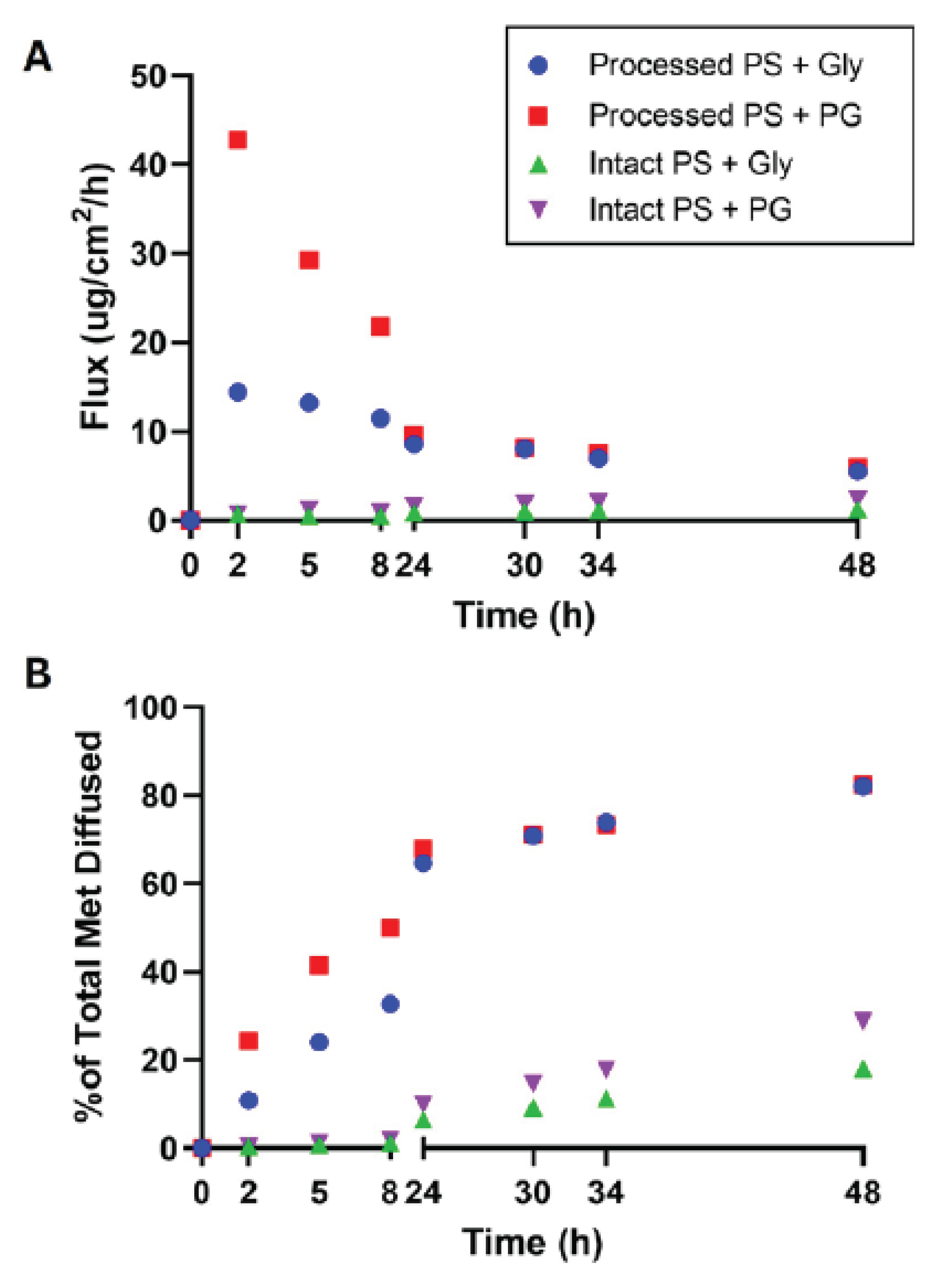

Permeation experiments were conducted on both intact and processed porcine ear skin (PS) using two 6% metformin lotion (ML) formulations: one containing 15% glycerol (Gly) and another containing 15% Gly plus 15% propylene glycol (PG). Metformin concentrations were quantified by HPLC, and flux (µg/cm²/h) and cumulative percent diffusion were determined over 48 h to characterize permeation profiles.

Processed Porcine Skin Exhibits Dramatically Higher Permeation

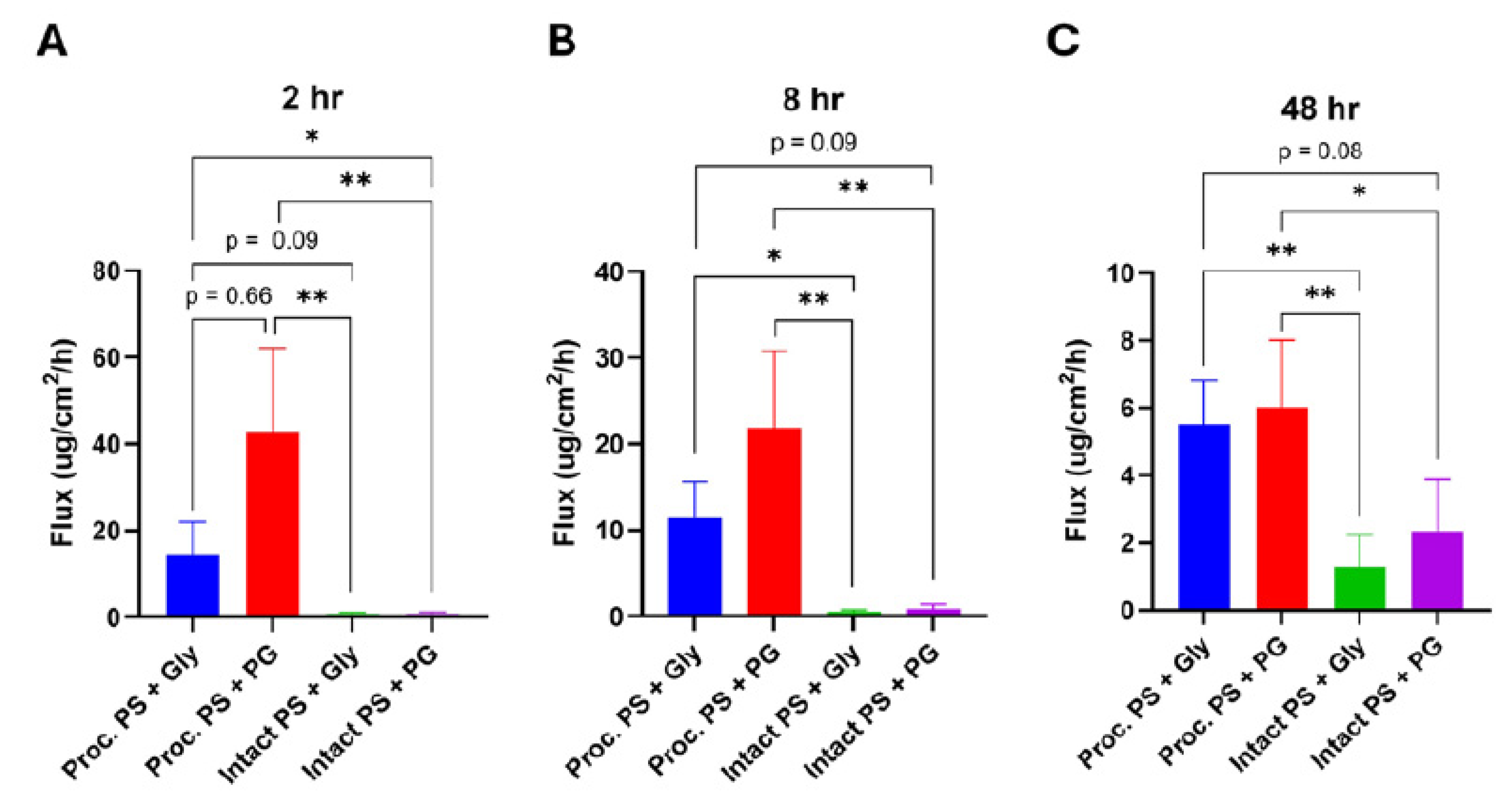

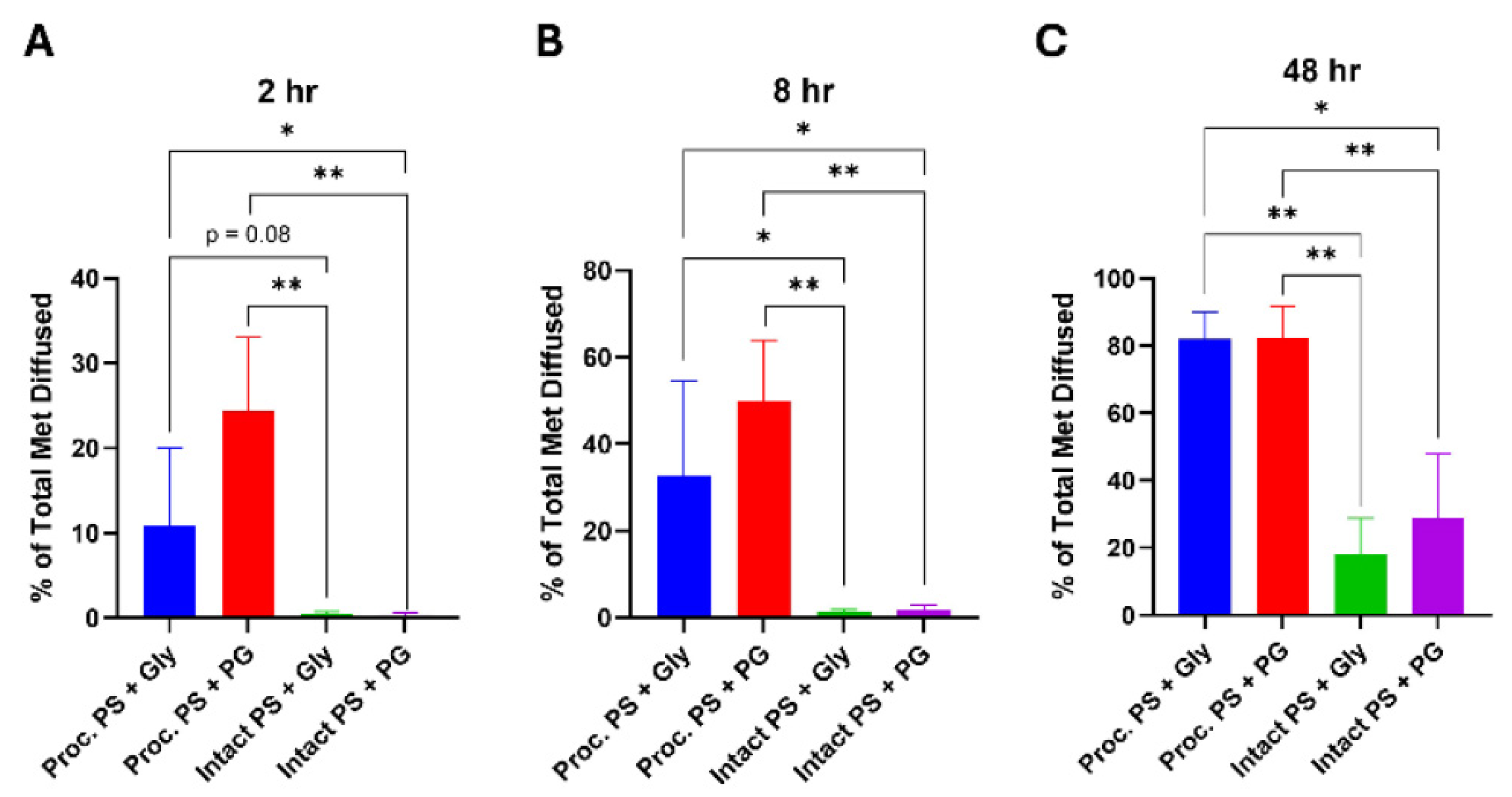

Metformin permeation was substantially higher through processed PS compared to intact PS across all time points (

Figure 1A, B). Processed skin showed an early peak flux within the first 2 h, reaching 14.4 ± 7.6 µg/cm²/h (Gly) and 42.8 ± 19.4 µg/cm²/h (PG) — values nearly 20–60× higher than those for intact skin at the same time point (0.8 ± 0.4 µg/cm²/h [Gly] and 0.7 ± 0.6 µg/cm²/h [PG]). Kruskal–Wallis analysis followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test revealed significant differences between processed and intact skin for both formulations across nearly all time points (

p < 0.05), with the exception of the Gly-treated groups at 2 h (

p = 0.076) (

Figure 2A, Figure 3A).

Cumulative metformin diffusion also followed this trend. By 8 h, processed PS achieved 32.7 ± 21.9% (Gly) and 49.9 ± 13.3% (PG) total diffusion — approximately 3–4× greater than intact PS at the same time point (7.8 ± 5.6% [Gly] and 12.4 ± 6.8% [PG];

p < 0.01 for both comparisons) (

Figure 1B). At later time points (24 h and 48 h), both processed groups remained significantly higher than their intact counterparts (

p < 0.01), plateauing around 24 h and reaching ~80% cumulative diffusion by 48 h. No statistically significant difference was observed between the Gly and PG formulations on processed skin at any time point (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 3C).

Intact Porcine Skin Maintains Barrier Properties

In contrast, intact PS maintained its barrier function throughout the 48 h study. Flux values remained low and did not exhibit a clear peak, reaching only 1.3 ± 0.9 µg/cm²/h (Gly) and 2.4 ± 1.5 µg/cm²/h (PG) by 48 h (

Figure 1A). Cumulative diffusion was correspondingly low, achieving 18.0 ± 10.9% and 28.9 ± 19.1% total permeation for Gly and PG, respectively (

Figure 1B). Although PG showed a slightly higher mean flux and cumulative diffusion than Gly in intact skin, these differences were not statistically significant at any time point (

p > 0.05) (

Figure 2B, C; Figure 3B, C).

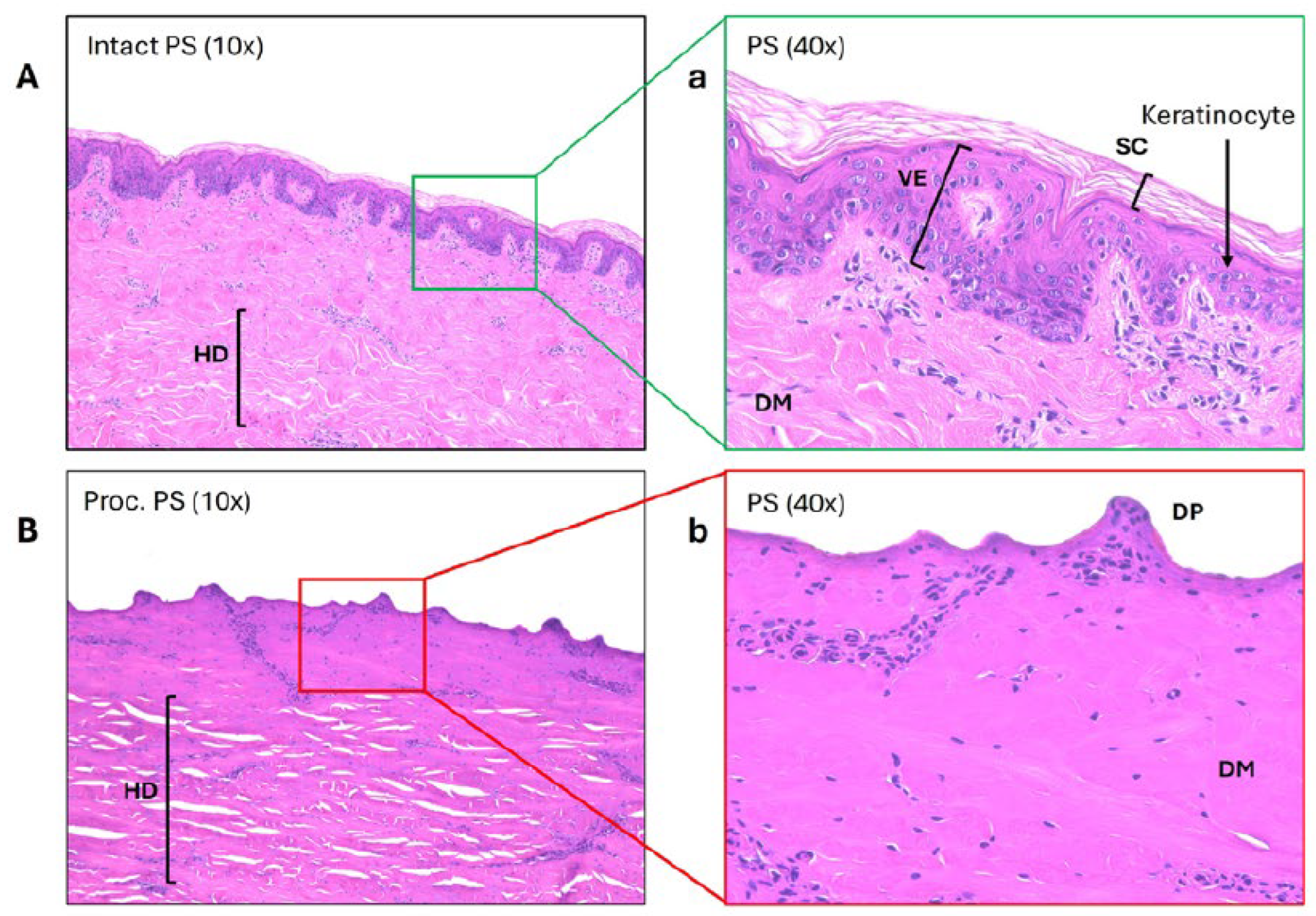

Histological Evidence Confirms Barrier Loss in Processed Skin

Histological analysis corroborated the functional permeation findings (

Figure 4). Intact PS exhibited a well-defined stratum corneum and viable epidermis, with abundant keratinocytes and organized dermal architecture. In stark contrast, processed PS lacked both the stratum corneum and viable epidermis, exposing dermal papillae directly at the surface. Collagen fibers appeared densely packed due to heat-induced shrinkage and partial denaturation, while numerous structural disruptions were visible in the hypodermis. These histological changes are consistent with the markedly increased permeability of hydrophilic metformin through processed skin (

p < 0.01 for processed vs. intact comparisons at 24 and 48 h).

Discussion

The skin is a complex biological barrier that plays essential roles in protecting the body from environmental threats, regulating water loss, and modulating molecular transport. The outermost stratum corneum, composed of keratinized cells embedded in a lipid matrix, is particularly important for restricting the penetration of hydrophilic and high–molecular weight molecules. Beneath it, the viable epidermis provides an additional layer of resistance to diffusion. Together, these structures pose a major challenge for transdermal drug delivery systems (TDDS), which aim to exploit the skin’s large surface area for sustained, localized therapy while bypassing first-pass metabolism and improving patient compliance [

12].

Because of their structural and physiological similarities to human skin, porcine ear skin is widely used as ex vivo models in in vitro permeation testing (IVPT) [

1,

2]. Both species share similar dermal–epidermal ratios, lipid and protein composition, and vascular distribution [

1,

2]. However, despite this widespread adoption, protocols for selecting, sourcing, and preparing porcine skin remain poorly standardized [

3]. Our study demonstrates that sourcing skin from commercially processed pig ears — which undergo scalding, dehairing, and carcass cleaning steps during pork harvest — fundamentally compromises barrier integrity and leads to dramatically higher drug permeation compared to intact, unprocessed skin [

13,

14].

We observed that processed porcine skin exhibited flux values and cumulative diffusion that were several-fold higher than those of intact skin, reaching approximately 20–60× greater flux within the first two hours and roughly 3–4× greater cumulative diffusion by eight hours. These exaggerated permeation values are consistent with the histological findings showing complete loss of the stratum corneum and viable epidermis following commercial processing. With these critical barrier layers removed, hydrophilic molecules such as metformin can diffuse rapidly into and through the underlying dermis. Such results demonstrate that processed porcine skin no longer behaves as a physiological barrier and is therefore unsuitable as a surrogate for human skin in permeation studies.

Our findings align with prior observations that removal of the stratum corneum alone markedly increases drug flux, and that further removal of the viable epidermis can enhance permeability by ~7-fold [

15]. These results highlight the need to consider not just the presence or absence of the stratum corneum but the overall structural integrity of the epidermis when interpreting permeation data.

The use of processed skin in permeation studies can lead to substantial overestimation of drug penetration and misrepresentation of formulation performance. Because many published studies do not clearly report sourcing details — such as whether the tissue was scalded, the time from slaughter to skin preparation, or the anatomical site used — comparing results across studies or drawing conclusions about clinical relevance becomes difficult [7-10]. Our results strongly support the adoption of standardized reporting practices for IVPT studies, including explicit disclosure of tissue source, preparation procedures, and barrier integrity assessments [3-5].

In cases where researchers wish to study drug delivery across compromised or damaged skin — for example, in burn, wound, or psoriasis models — it is critical that the damage be precisely controlled and well-characterized. Commercially processed skin does not replicate defined injury models, as it undergoes uncontrolled mechanical, thermal, and chemical stressors that unpredictably alter permeability and mechanical properties [

2,

16]. Controlled wound models, particularly those using live animals with intact immune and vascular responses, remain the gold standard for investigating topical therapies targeting pathological skin conditions [

17].

A limitation of this study is the use of frozen tissue, which may introduce variability in skin integrity and permeability. Previous work has reported both minimal and significant effects of freezing on percutaneous absorption [

4,

18,

19]. However, the magnitude of the differences we observed between intact and processed skin suggests that processing artifacts, rather than storage conditions, are the dominant factor driving permeation outcomes. Future studies could further investigate this by systematically reproducing individual steps of the pork harvest process (e.g., scalding, scraping, or acid washing) under controlled laboratory conditions using both porcine and human skin.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that commercially processed porcine ear skin exhibits profoundly altered barrier properties due to the loss of key epidermal layers, resulting in artificially elevated permeation rates of hydrophilic drugs such as metformin. These findings underscore the importance of careful skin sourcing, preparation, and characterization when designing IVPT studies and interpreting their results. They also highlight the need for clearer regulatory guidance and standardized protocols regarding the sourcing and preparation of porcine skin for IVPT studies. Standardizing these practices will improve the reproducibility, reliability, and translational relevance of transdermal drug delivery research.

Material and Methods

Chemicals and Reagents

For preparation of the mobile phase, ammonium acetate (CAS-No. 631-61-8, molecular biology grade, purity ≥ 98%) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich. HPLC-grade water (Cat. No. W5SK-4), acetonitrile (Cat. No. 35581, 99.9%, gradient grade), and glacial acetic acid (Cat. No. A35-500) were obtained from Fisher Chemical.

For lotion formulation, metformin hydrochloride (CAS-No. 1115-70-4, ≥98%, titration), paraffin oil (Cat. No. 18512-1L), sorbitan sesquioleate (Span® 83, CAS-No. 8007-43-0), and Vaseline (Cat. No. 16415-1KG) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. The lotion base was enhanced with either glycerol (Cat. No. G-6279, ~99%, GC, Sigma Aldrich) alone or a combination of glycerol and propylene glycol (Cat. No. 151957, MP Biomedicals). Double-distilled water (ddH₂O) was supplied by the in-house facility.

Acquisition of Porcine Skin

Unscalded, healthy porcine ears were freshly butchered and ethically obtained from a local slaughterhouse with skin and hair intact. Samples were transported to the laboratory on ice within 3 hours. Upon arrival, ears were gently rinsed under lukewarm running water to remove dirt, blood, and debris, patted dry, and trimmed of hair using electric clippers and scissors. Cleaned ears were stored in airtight plastic bags at –20 °C until use.

Processed porcine ears were purchased frozen in vacuum-sealed bags from a local butcher shop. “Processed” refers to the pork harvest procedures — including scalding, dehairing, and skinning — conducted after humane slaughter to prepare pork for food consumption. These samples were also stored immediately at –20 °C until use.

Preparation of Porcine Skin for Permeation Testing

Porcine ears were thawed in a 37 °C water bath, and the skin was carefully separated from the underlying cartilage using a scalpel. Remaining fat and connective tissue were trimmed with scissors to yield sections approximately 1 mm thick. The skin was then cut into ~2 cm² squares, placed individually on PBS-soaked gauze, laid flat in tissue culture plates, and stored at 4 °C overnight prior to testing.

Franz Diffusion Cell Permeation Testing

Permeation experiments were performed using a PermeGear Franz diffusion cell system. Each jacketed cell (9 mm orifice diameter, receptor volume 5 mL) was connected to a circulating water bath (Julabo CORIO™ CD-BC4) maintained at 37 °C.

Skin samples stored at 4 °C were equilibrated by immersion in PBS at 35 °C for 30 minutes to restore hydration. Samples were then blotted dry and mounted on foam boards. A circular indentation (~9 mm diameter) was created on the skin surface with the Franz cell cap. Approximately 4–5 mg of lotion was evenly applied to the skin surface, and the setup was reweighed to calculate the applied dose.

The skin was mounted onto the Franz cell, the cap was secured, and the cell was inverted to remove trapped air. If necessary, the receptor chamber was filled to the 5 mL volume line with ddH₂O. All joints were sealed with Parafilm to prevent evaporation. Samples (200 µL) were withdrawn from the receptor chamber at 0, 2, 5, 8, 24, 30, 34, and 48 hours and replaced with fresh ddH₂O. After 48 hours, residual lotion was collected from the skin surface. Each fraction (residual lotion and whole skin section) was submerged in 5 mL ddH₂O for ≥ 6 hours to extract metformin. Following FDA and OECD guidelines for permeation testing, a 48 hour study duration was chosen to capture a complete flux profile, including peak flux and subsequent decline [

5,

20]. All samples were treated with 600 µL of acetonitrile, centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, dried overnight at 75 °C, reconstituted in 200 µL of mobile phase, and transferred into HPLC vials.

Histology

Small skin samples from fresh intact pig ears and frozen-thawed processed ears were fixed in formalin. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and sectioning were performed by Tony Green’s Research Histology Service at the University of Pittsburgh. Images were captured using a Keyence BZ-X800 Series All-in-One fluorescence microscope (Keyence Corporation of America, Itasca, IL).

Experimental Groups

Four experimental groups were evaluated in this study. Processed porcine skin (PS) samples were treated either with a 6% metformin lotion (ML) formulated with 15% glycerol (Gly) alone or with a formulation containing 15% Gly and 15% propylene glycol (PG). Similarly, intact PS samples were treated with the same two formulations: one containing 15% Gly only and the other containing both 15% Gly and 15% PG. Each experimental group consisted of eight samples (n = 8).

Instrumentation and Chromatographic Conditions

An Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) was used for compound separation and detection. The system was equipped with an auto-injector, quaternary pump, online degasser, and a diode array detector (DAD), and was operated using ChemStation LC 3D software. Chromatographic separation was achieved on a normal-phase Supelcosil™ LC-SI column (25 cm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

The mobile phase consisted of 10 mM ammonium acetate buffer (adjusted to pH 5 with glacial acetic acid) and HPLC-grade acetonitrile (ACN) in a 40:60 (v/v) ratio, delivered at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min under isocratic conditions. Detection was performed at 235 nm. The method, previously validated by Huttunen et al. [

21], demonstrated high specificity, linearity, and accuracy. Under these conditions, metformin eluted at approximately 9.0 minutes, while endogenous biological components appeared between 2–4 minutes.

For quantification, a stock solution of metformin (1 mg/mL) was prepared by dissolving 10 mg of metformin hydrochloride in 10 mL of ddH₂O. From this, a working solution (100 µg/mL) was prepared, and standard solutions ranging from 0 to 100 µg/mL were generated. Each standard was processed by mixing 200 µL of solution with 600 µL of ACN, vortexing, drying overnight at 75 °C, reconstituting in 200 µL of mobile phase, and transferring 50 µL into glass vial inserts for HPLC analysis under identical conditions as the permeation samples.

Metformin concentrations in receptor fluid samples were determined using a calibration curve generated from these standards. The cumulative amount of metformin (µg) at time

t was calculated as the sum of the content in the receptor chamber (concentration × 5 mL) and in previously collected samples (concentration × 0.2 mL for times 0 to

t − 1). The amount remaining in the skin and residual lotion after 48 hours was calculated by multiplying the measured concentration by the dissolution volume (5 mL). The total applied dose was then determined as the sum of the cumulative metformin and residual amounts. The cumulative flux (

J, µg/cm²/h), defined as the amount of permeant crossing the skin per unit time, was calculated by dividing the cumulative metformin by the diffusion surface area (0.64 cm²) at each time point [

22].

Statistical Analysis

A Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons was performed at the 8, 24, and 48 h time points to compare the percentage of total metformin diffused among experimental groups. Nonparametric methods were chosen due to the distributional characteristics of the data. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. All data analyses and graphical representations were conducted using GraphPad Prism (version 10.5.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and approved the final manuscript. C.Z. contributed to investigation, data curation, formal analysis, validation, and writing - original draft; J. Z. contributed to methodology, investigation, formal analysis, and validation; V. P. contributed to methodology and investigation; and J. H-C. Wang developed conceptual idea, and contributed to project administration, methodology, validation, resources, and writing-review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the DOD/MTEC Award W81XWH2290016 and the DOD Award HT9425-23-1-0617.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Simon, G.A.; Maibach, H.I. The pig as an experimental animal model of percutaneous permeation in man: qualitative and quantitative observations--an overview. Skin Pharmacol Appl Skin Physiol 2000, 13, 229-234. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S.; Kruger, U.; Josyula, K.; Rahul; Gong, A.; Song, A.; Sweet, R.; Makled, B.; Parsey, C.; Norfleet, J.; et al. Thermally damaged porcine skin is not a surrogate mechanical model of human skin. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 4565. [CrossRef]

- Silva, I.R.; Lima, F.A.; Reis, E.C.O.; Ferreira, L.A.M.; Goulart, G.A.C. Stepwise Protocols for Preparation and Use of Porcine Ear Skin for in Vitro Skin Permeation Studies Using Franz Diffusion Cells. Curr Protoc 2022, 2, e391. [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.; Bracher, M. Standard Protocol: Percutaneous Absorption/Penetration In Vitro Pig Skin. Colipa Guidelines: Guidelines for Percutaneous Absorption/Penetration. Rte de Chesalles 21, CH 1723 Marly 1. 1995.

- Report. Skin Absorption: In vitro Method, OECD Guideline for the Testing of Chemicals (428). 2004.

- Diembeck, W.; Grimmert, A. Standard Protocol: Percutaneous Absorption/Penetration In Vitro Excised Pig Skin Colipa Guidelines (Hamburg, Germany) 1995.

- Iliopoulos, F.; Sil, B.C.; Moore, D.J.; Lucas, R.A.; Lane, M.E. 3-O-ethyl-l-ascorbic acid: Characterisation and investigation of single solvent systems for delivery to the skin. Int J Pharm X 2019, 1, 100025. [CrossRef]

- Makuch, E.; Nowak, A.; Gunther, A.; Pelech, R.; Kucharski, L.; Duchnik, W.; Klimowicz, A. The Effect of Cream and Gel Vehicles on the Percutaneous Absorption and Skin Retention of a New Eugenol Derivative With Antioxidant Activity. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 658381. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, A.; Muzykiewicz-Szymanska, A.; Peruzynska, M.; Kucharska, E.; Kucharski, L.; Jakubczyk, K.; Niedzwiedzka-Rystwej, P.; Stefanowicz-Hajduk, J.; Drozdzik, M.; Majtan, J. Assessment of in vitro skin permeation and accumulation of phenolic acids from honey and honey-based pharmaceutical formulations. BMC Complement Med Ther 2025, 25, 43. [CrossRef]

- Keck, C.M.; Abdelkader, A.; Pelikh, O.; Wiemann, S.; Kaushik, V.; Specht, D.; Eckert, R.W.; Alnemari, R.M.; Dietrich, H.; Brussler, J. Assessing the Dermal Penetration Efficacy of Chemical Compounds with the Ex-Vivo Porcine Ear Model. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, K.; Adibfard, S.; Nikbakht, M.H.; Rastegarnasab, F.; Pourmahdi-Boroujeni, M.; Abtahi-Naeini, B. A Systematic Review on Clinical Evidence for Topical Metformin: Old Medication With New Application. Health Sci Rep 2024, 7, e70281. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Krishnamurthy, K. Histology, Skin. StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL) 2023.

- Berg, E.P. In Critical Points Affecting Fresh Pork Quality within the Packing Plant. Pork Information Gateway, Eilert, S., Ed. 2006.

- Brashears, M.; Miller, M.; Brooks, T. Pork Harvest Process, International Center for Food Industry Excellence (ICFIE) ,Texas Tech University: Lubbock, Texas, USA.

- Andrews, S.N.; Jeong, E.; Prausnitz, M.R. Transdermal delivery of molecules is limited by full epidermis, not just stratum corneum. Pharm Res 2013, 30, 1099-1109. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Kim, Y.C.; Prausnitz, M.R. The effect of heat on skin permeability. Int J Pharm 2008, 359, 94-103. [CrossRef]

- Cioce, A.; Cavani, A.; Cattani, C.; Scopelliti, F. Role of the Skin Immune System in Wound Healing. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Sintov, A.C. Cumulative evidence of the low reliability of frozen/thawed pig skin as a model for in vitro percutaneous permeation testing. Eur J Pharm Sci 2017, 102, 261-263. [CrossRef]

- Meira, A.S.; Battisel, A.P.; Teixeira, H.F.; Volapato, N.M. Evaluation of porcine skin layers separation methods, freezing storage and anatomical site in in vitro percutaneous absorption studies using penciclovir formulations. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2020, 60, 101926.

- FDA. In Vitro Permeation Test Studies for Topical Drug Products Submitted in ANDAs: Guidance for Industry. 2022.

- Huttunen, K.M.; Rautio, J.; Leppanen, J.; Vepsalainen, J.; Keski-Rahkonen, P. Determination of metformin and its prodrugs in human and rat blood by hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2009, 50, 469-474. [CrossRef]

- PermeGear, I. Diffusion testing fundamentals. 2015, PermeGear, Inc, 1-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).