1. Introduction

Burn injuries are forms of trauma that are steadily increasing around the world as well as in our country. These patients face pain, deformities, and potential death. Apart from causing local tissue damage, a burn injury leads to systemic intoxication of the body (burn disease) [

1]. This condition in patients is accompanied by intense pain and possible episodes of sepsis, which can result in a fatal outcome. Unfortunately, recovered patients may face disfigurement and permanent disability [

2]. Understanding the relationship between the biological processes of normal and delayed healing will greatly contribute to developing a clear strategy for treating these pathological states.

Intermediate burns of partial skin thickness are a special entity. Their classification is indefinite. They tend to epithelialize at control dressings but do not heal within three weeks. Histological research has shown a dynamic process around the third day after injury [

2,

3].

The ideal topical agent in burn treatment has the following characteristics: 1) possesses a broad spectrum of bactericidal and fungicidal action even in situations where there is significant exudate and wound infection; 2) improves and accelerates physiological wound healing processes (granulation, epithelialization, and contraction); 3) does not cause local and systemic adverse effects (allergic reactions, toxicity, etc.) even with prolonged application; 4) is cost-effective; and 5) is comfortable to apply (easy and painless application) [

4].

Honey is a viscous concentrated sugar solution produced by bees (Apis mellifera). Bees collect and process floral nectar (flower or floral honey) or gather sweet plant juices (honeydew or forest honey). Honey has osmolarity and pH values that enable bacteriostatic and bactericidal action. The enzyme glucose oxidase found in the bees' hypopharyngeal glands releases gluconolactone and hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates fibroblast proliferation and epithelialization by keratinocyte migration from the edges of the wound in lower concentrations [

5]. In comparison, it releases a large amount of oxygen radicals in higher concentrations, which harm healing [

4,

6].

Manuka honey contains methylglyoxal, bee-defensin 1, and melanoidsfound in various nectars bees collect [

7,

8]. It has been determined that honey reduces inflammation and scar contraction through its antioxidant properties, neutralizes free radicals, and acts bactericidal by lowering the pH of the environment. All these characteristics positively affect the healing of a burn wound [

9]. Honey activates phagocytosis and stimulates the proliferation of B and T lymphocytes. In addition to other mechanisms, honey contributes to the activation of monocytes by releasing important cytokines such as TNF, IL-1, and IL-6 [

10]. This evidence strongly suggests that honey plays a role in enhancing the local immune response. It is considered to stimulate fibroblasts, reduce fibrosis, and, consequently, the formation of hypertrophic scars.

Antioxidants reduce the secretion of free oxygen radicals, thereby shortening the inflammatory phase, which is crucial for tissue healing [

11]. In addition, honey creates a physical barrier. It creates a moist environment with high viscosity by drawing water through osmosis, which has a positive effect, considering that wounds heal faster in a moist environment [

12].

Choosing an animal model that closely resembles humans in terms of pathophysiological mechanisms and scar formation is necessary to study the healing process of burn wounds, scar formation, and evaluation. Many models are used in the process of burn wound healing, but none is perfect. Research on humans is often the best since it is closest to the healing process. Still, collecting a sufficient number of patients with similar injuries, a series of facts, and influences that could play a role in healing is sometimes practically impossible. The inability to take biopsies is also one of the problems when working with human organisms and human tissue.

Small mammals, such as rabbits, rats, and mice, have advantages since they are easy to handle and inexpensive. However, a significant problem is that their healing mechanism differs considerably from that of humans. The dermis and epidermis in these animals are very thin, the hair is much denser, and there is a muscular layer (panniculus carnosus) beneath the dermis, which humans do not have, making the healing process primarily based on contraction [

13].

The model that is closest to humans consists of large mammals such as pigs. The similarity between human and pig skin is significant and is reflected in: 1. The thickness of the epidermis (from 50 to 120μm in humans and 30–140μm in pigs; 2. The thickness of the dermis (from 500 to 1200μm in humans and from 500 to 1800μm in pigs; 3. A relatively similar ratio of the epidermis to the dermis (in humans 1:10, and in pigs 1:13); 4. A well-developed papillary dermis; 5. The distribution of blood vessels and skin adnexa; 6. Well-developed subcutaneous fat tissue; 7. Similar biochemical characteristics of dermal collagen [

14,

15].

2. Results

2.1. Temperature Difference of Wound

The FLIR One camera was used on the first post-intervention day after the burns were applied, and a statistically significant difference was found in the wounds. Wounds that showed complete re-epithelialization between 14-21 days were characterized as mesodermal, while burns that healed after 21 days were classified as deep dermal. The deep dermal group had a 1.60±0.34°C temperature difference between the body and the burn wound, while the mesodermal group had a significantly lower temperature difference (t=2.365; p=0.024) compared to the control group (2.66±0.27°C).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation values of the temperature difference in the wound area (°C).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation values of the temperature difference in the wound area (°C).

| Re-epitelisation(time) |

Mean value () |

Standard deviation (SD) |

| Mesodermal burns |

1.60 |

0.34 |

| Deep dermal burns |

2.66 |

0.27 |

2.2. Morphometric Analysis Evaluation and Histopathology Characteristics of Burn Wound Healing

2.2.1. Morphometric Analysis

Initial assessments (immediate post injury – 1st day) showed uniform deep dermal burns across all groups, but no immediate post-injury comparative data were provided between treatments.

On the

3rd day post injury the necrotic debris depth and the intact reticular dermis thickness were assessed. For the control group, the average thickness of necrotic detritus was 662.35±115.93μm, and for Manuka honey, it was 657.70±123.86μm. The difference was insignificant (U=197.00; p=0.947), indicating similar initial injury severity between treatments (

Figure 2A). The average reticular dermis thickness was 1003.46±302.69μm for the control group and 1196.01±287.83μm for the Manuka honey group. These two groups' differences were insignificant (U=128.00; p=0.053) (

Figure 2B).

At the

7th day post injury Manuka honey treatment significantly improved the epidermal regeneration compared to the ointment group. The Manuka honey group showed an epidermal thickness of 81.19±111.11μm, significantly higher than the control group, which had negligible epidermal formation at this stage (U=100.00; p=0.006) (

Figure 2C). Similar results were for epidermal ridges, where the Manuka honey group had a thickness of 46.11±60.16μm,significantly higher than in the control group with also negligible epidermal ridges formation (U=100.00; p=0.006) (

Figure 2D). Also, the thickness of granulation tissue for the Manuka honey group was not provided explicitly for Day 7, making direct comparison challenging. However, an overall trend towards improved healing with Manuka honey was noted. Granulation tissue thickness in the Control group (313.85±251.38μm) was slightly higher than in the Manuka honey group (286.06±136.74μm), but this difference was not statistically significant (U=173.00; p=0.478) (

Figure 2E). However, reticular dermis thickness was significantly higher (U=114.00; p=0.020) in the Manuka honey group (1291.95±452.21μm) than in the Control group (1027.72±368.85μm) (

Figure 2F).

By 10th day post-injury, the Manuka honey group exhibited significantly higher epidermal thickness (295.31±168.05μm) compared to the control group (61.58±92.07μm), which displayed much lower epidermal development (

Figure 2G). This indicates a faster re-epithelialisation process in the Manuka honey-treated wounds (U=23.00; p<0.001). Epidermal ridges thickness was also significantly higher (U=74.00; p<0.001) in the Manuka honey group (171.06±128.44μm) in comparison to the control group (2959.49±119.12μm) (

Figure 2H); The thickness of granulation tissue for the Manuka honey group was not provided explicitly for Day 10, making direct comparison challenging. However, an overall trend towards improved healing with Manuka honey was noted. Granulation tissue thickness in the Control group (650.12±403.33μm) was slightly higher than in the Manuka honey group (458.08±225.288μm), but this difference was not statistically significant (U=145.00; p=0.14) (

Figure 2I). However, reticular dermis thickness was significantly higher (U=85.00; p=0.001) in the Manuka honey group (1536.01±412.18μm) than in the Control group (1246.04±387.08μm) (

Figure 2J).

By Day 17, the Manuka honey group exhibited significantly higher epidermal thickness (442.47±189.81μm) compared to the control group (125.12±136.73μm), which displayed much lower epidermal development (

Figure 2K). This indicates a faster reepithelializa-tion process in the Manuka honey-treated wounds (U=30.00; p<0.001). Epidermal ridges thickness was insignificant (U=74.00; p<0.001) in comparation of the Manuka honey group (163.65±100.43μm) to the control group (159.49±180.92μm) (

Figure 2L);

By 17th and 20th day post-injury, Manuka honey treatment resulted in a more pronounced reduction in granulation tissue thickness and a more substantial increase in the thickness of the intact reticular dermis, suggesting more efficient healing and dermal recovery. Specific statistical values for these time points underscore the effectiveness of Manuka honey in enhancing wound healing processes over the ointment group. On the 17

th day, granulation tissue in the control group was 1622.55±936.41μm, while in the Manuka group, it was 1111.65±805.07μm (

Figure 2M). These two groups had no statistical difference (U=135.00; p=0.081). However, on the same day, reticular dermis thickness in the Manuka group (1574.06±362.63μm) compared to the Control group (878.13±212.44μm)was statistically different (U=11.00; p<0.001) (

Figure 2N). On the 20th day, granulation tissue thickness was 1860.23±1010.95μm in the Control group, while it was 1042.27±763.45μm in the Manuka honey group. There was a significant difference between these two groups (U=112.00; p=0.017) (

Figure 2R). Reticular dermis thickness on the 20th day was similar between the Control and Manuka honey groups (U=129.00; p=0.056) (

Figure 2S).

In the

scar or 60th day post-injury, in the Manuka honey group, the average epidermal thickness (162.69±43.73μm)was statistically smaller (U = 84.50, p = 0.002) than the average epidermal thickness in the Control group (256.72±102.05 μm) (

Figure 2T). Regarding epidermal ridges, their average thickness in the control group was 96.21±40.86 μm, while the average thickness in the Manuka honey group was 30.83±25.37μm (

Figure 2U). There was a significant difference between these two groups (U = 32.00; p < 0.001).The average thickness of granulation tissue in the Control group (1754.27±488.62μm) is statistically higher (U=70.00: p<0.001) than in the Manuka honey group (698.95±275.24) (

Figure 2V).The average reticular dermis thickness in the Control group was 1853.59±507.59μm, while reticular dermis thickness in the Manuka honey group was 2076.44±559.34μm. These two groups had no significant difference (U = 121.00; p = 0.156) (

Figure 2W).The Vancouver Scar Scale detected no statistically significant difference in scar scores among the different treatments (U = 111.00, p = 0.111).

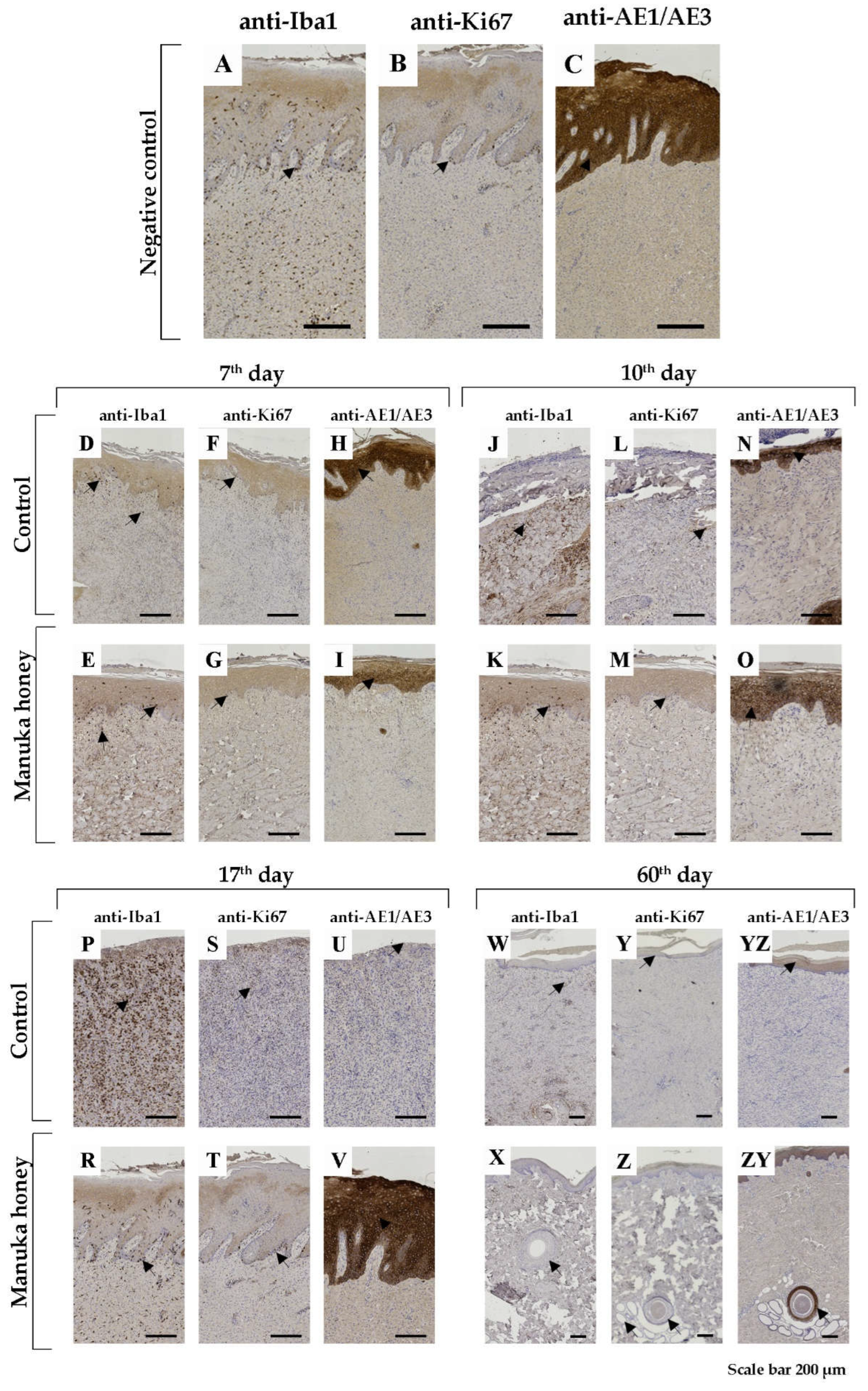

2.2.2. Histopathology Characteristics of Burn Wound Healing

Using Mason trichrome (MTS) and Picrosirius red (PRS) staining techniques, we tried to present the density and regularity of collagen fibre orientation in the dermis, which we can see in healthy skin—negative control (

Figure 3A,B).

The most pronounced results in the control group, during the 7th, 10th, and 17th days post-injury, were increased non-specific granular inflammation of the dermis with very slow epithelialization. Using the mentioned histochemical staining, we noticed a decreased number of disturbed collagen fibres in the dermis (

Figure 3C,D,G,H,K,L). Using immunohistochemical markers for macrophages, we still found many of them on the 7th and especially the 10th and 17th day post-injury (

Figure 4D,J,P). Following dermis changes, epithelialization also decreased in the control group. The proliferative immunohistochemical marker shows few proliferative basal cells (

Figure 4F,L,S). Also, using pan-cytokeratin, we identified epidermal layers that were poorly reconstructed (

Figure 4H,N) or absent (

Figure 4U).

Conversely, in the Manuka honey-treated wound, we noticed reconstruction of the dermis with increased collagen production (

Figure 3E,F,I,J,M,N). The qualitative differences from the 7th to the 17th day post-injury were not noticed. In immunohistochemical analysis of Iba1 positive macrophages, we identified them with increasing numbers from the 7th to the 17th day, respectively (

Figure 4E,K,R). However, their number was still smaller than that of the control group. Also, by applying manuka honey, we noticed better reepithelialization of the wound with increased proliferation of basal keratinocytes (

Figure 4G,M,T) and thicker epidermal layer (

Figure 4I,O,V).

After the 60th day post-injury, the wounds in all groups were healed. However, using MTS and PRS, we noticed fewer collagen fibres (

Figure 3O,P) than the manuka honey-treated wound (

Figure 3R,S). We can say that the number of collagen fibres in the Manuka honey-treated wound was more similar to the histology picture of healthy skin (negative control) (

Figure 3A,B).

Using the immunohistochemical technique, we did not notice differences between the control (

Figure 4W,Y,YZ) and the Manuka-treated group (

Figure 4X,Z,ZY).

Table 2.

Vancouver Scar Scale values.

Table 2.

Vancouver Scar Scale values.

| Day Group |

Median (M) Minimum (Min) |

Maximum (Max) |

| 60th day Control |

3.00 0.00 |

8.00 |

| 60th day Manuka honey |

1.50 0.00 |

5.00 |

Figure 1.

Morphometric analysis of skin compartments: necrotic debris thickness (just in 3rd day); epidermal thickness; epidermal ridges thickness; granulation tissue thickness; reticular dermis thickness;.

Figure 1.

Morphometric analysis of skin compartments: necrotic debris thickness (just in 3rd day); epidermal thickness; epidermal ridges thickness; granulation tissue thickness; reticular dermis thickness;.

Figure 2.

Histochemical staining of wound lesion. Scan of whole tissue biopsy with the magnification of black frame area on its. A, B representative healthy normal porcine skin (negative control group). Presentation of 7th, 10th, 17th and 60th-day biopsy post-injury. Masson's trichrome (MTS) and Picrosirius Red (PSR) staining technique. Magnification, scan picture (scale bar 500µm), microphotograph (scale bar 200µm).

Figure 2.

Histochemical staining of wound lesion. Scan of whole tissue biopsy with the magnification of black frame area on its. A, B representative healthy normal porcine skin (negative control group). Presentation of 7th, 10th, 17th and 60th-day biopsy post-injury. Masson's trichrome (MTS) and Picrosirius Red (PSR) staining technique. Magnification, scan picture (scale bar 500µm), microphotograph (scale bar 200µm).

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of wound lesion. Macrophage marker – Iba1 (asterisk – cytoplasmic positivity); Proliferative marker – Ki67 (asterisk- nuclear positivity); Pan-cytokeratin –AE1/AE3 (asterisk- cytoplasmic positivity); A, B and C representative IHH staining (anti-Iba1, anti-Ki67, anti-AE1/AE3, respectively) healthy normal porcine skin (negative control group). Presentation of 7th, 10th, 17th and 60th-day post-injury of control and Manuka honey treated groups. The magnification of all pictures was 200µm.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of wound lesion. Macrophage marker – Iba1 (asterisk – cytoplasmic positivity); Proliferative marker – Ki67 (asterisk- nuclear positivity); Pan-cytokeratin –AE1/AE3 (asterisk- cytoplasmic positivity); A, B and C representative IHH staining (anti-Iba1, anti-Ki67, anti-AE1/AE3, respectively) healthy normal porcine skin (negative control group). Presentation of 7th, 10th, 17th and 60th-day post-injury of control and Manuka honey treated groups. The magnification of all pictures was 200µm.

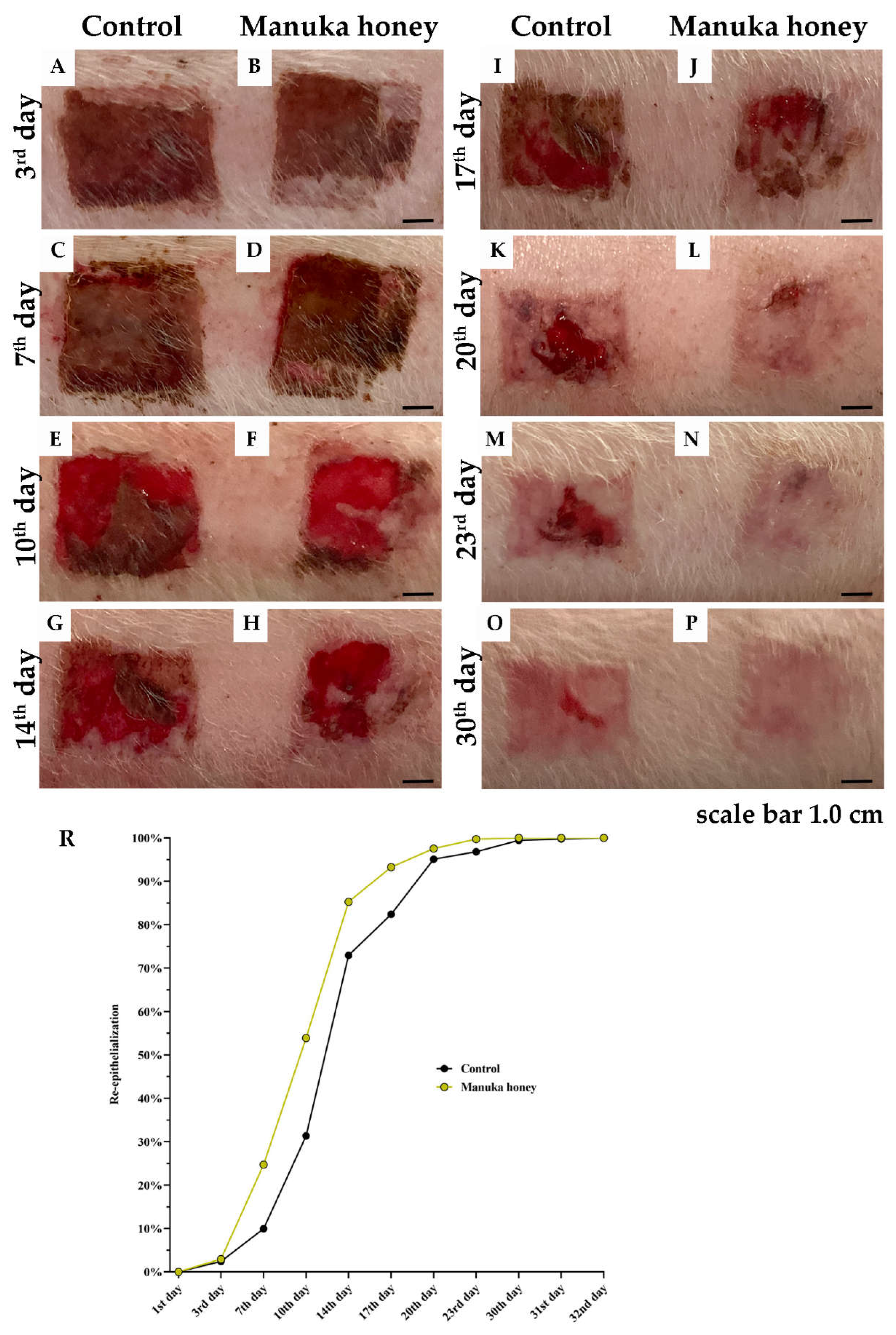

Figure 4.

Measurement of the reepithelialization area (REA). Photodocumentation of the wound in Control and Manuka honey treated group). Graphical presentation of REA.

Figure 4.

Measurement of the reepithelialization area (REA). Photodocumentation of the wound in Control and Manuka honey treated group). Graphical presentation of REA.

2.3. Measurement of the Reepithelialization Area (REA)

The reepithelialization process was meticulously observed from the moment of thermal injury induction until the achievement of complete wound closure, spanning up to 32 days (

Figure 5A–P). Initial assessments across all experimental setups confirmed identical burn wound areas, thereby establishing a baseline reepithelialization rate of 0% for all groups.Significant advancements in the healing process were observed in the group treated with Manuka honey, particularly noted during the early stages of recovery. Statistical analyses revealed a marked difference in the rates of reepithelialization between the Manuka honey group and the control group on the 7

th day post-injury (p < 0.05), indicating an enhanced healing response facilitated by the Manuka honey treatment (

Figure 5C,D).This accelerated healing trajectory persisted, with the Manuka honey group demonstrating significantly higher wound closure compared to the control group on 10th days post-injury (p < 0.01) (

Figure 5E,F). The difference in healing efficacy became even more pronounced over time, highlighting the therapeutic potential of Manuka honey in promoting rapid wound recovery.Subsequent observations up to the 32nd day consistently showed that the Manuka honey treatment group experienced a faster and more efficient reepithelialization process when compared to the control group. By the conclusion of the study period, all wounds in the Manuka honey group had achieved complete epithelialization, underscoring the superior healing capabilities of Manuka honey.

2.4. Bacteriological Analysis

The antibiogram was conducted but not presented since the wounds exhibited only micro colonization by saprophytes, including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Corynebacterium species, Propionibacterium acnes, and non-beta-hemolytic Streptococcus species (e.g., Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus mitis). Clinically, there were no signs of infection.

2.5. Complications

During the study, complications included rectal prolapse in three experimental animals. This was effectively managed with repositioning and purse-string sutures. One animal experienced a recurrence, which required multiple sutures. Additionally, a leg fracture in another animal was conservatively treated. No animals were excluded from the study, and all were successfully returned to their natural habitat after 60 days.

3. Discussion

Honey's antimicrobial properties have been recognized for centuries [

7,

8,

10,

12]. Manuka honey, specifically used in this study, has superior antibacterial activity compared to regular honey, due to its high levels of methylglyoxal, bee-defensin 1, and melanoids. In this study, Manuka honey was incorporated into a calcium alginate dressing. The alginate acts as a structural carrier, absorbing exudate, while Manuka honey delivers its bioactive compounds to promote wound healing by reducing bacterial load and inflammation [

8,

16,

17].

Pathohistological analysis on day 3 showed similar necrosis thickness between the control and Manuka honey groups (662 μm vs. 657 μm). Early reepithelialization rates were also comparable (2.94% in the Manuka honey group vs. 2.42% in the control). However, by day 7, the Manuka honey group demonstrated a significantly higher reepithelialization rate (54%) compared to the control (31%). By day 10, reepithelialization reached 85% in the Manuka honey group, significantly higher than the control group’s 72%. Pan-cytokeratin staining confirmed epithelial formation, and Ki-67 immunohistochemistry showed increased cell proliferation in the Manuka honey group, supporting the faster wound healing [

18,

19,

20].

Reepithelialization is crucial in wound healing as it restores the skin's barrier function, preventing infection and fluid loss. Manuka honey's ability to accelerate this process likely results from its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, which create an optimal environment for epithelial cells to proliferate and migrate. The faster development of epithelial tissue, seen as early as day 7, points to Manuka honey's role in promoting growth factors necessary for epithelial proliferation. This faster reepithelialization, combined with reduced macrophage activity, suggests that Manuka honey not only improves healing but also promotes scarless healing by reducing prolonged inflammation and enhancing organized tissue regeneration [

21,

22,

23].

Japanese researchers [

24] assessed the effect of Manuka honey on Jackson's zone of stasis in an experiment on rats. The study did not prove that Manuka honey could affect the depth of the burn wound but showed significantly faster reepithelialization compared to the group of rats treated with silver sulfadiazine. This research aligns with our results

Macrophages are essential in the inflammatory phase of wound healing, clearing pathogens and dead cells [

25]. In our study, macrophage activity was significantly reduced in the Manuka honey group on days 10 and 17, as confirmed by Iba1 staining. This reduction suggests that Manuka honey accelerates the resolution of inflammation, facilitating the transition to the proliferative phase [

26,

27]. By minimizing prolonged inflammation, Manuka honey contributes to more efficient tissue repair and reduces the risk of excessive scarring, further supporting its role in promoting scarless healing.

Histological staining, including Masson's trichrome and Picrosirius red, revealed that granulation tissue was thinner and collagen density was higher in the Manuka honey group. These findings suggest that Manuka honey stimulates fibroblast activity, enhancing collagen production and dermal regeneration. Fibroblasts are key players in wound healing, responsible for producing collagen and other extracellular matrix components that restore tissue structure [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The increased dermal density observed in the Manuka honey group points to improved dermal remodeling, a critical factor in reducing scar formation. This result is consistent with findings from studies like Ranzato et al., which demonstrated enhanced fibroblast function in vitro with Manuka honey [

23].

Additionally, clinical observation revealed that Manuka honey promoted faster wound debridement, with necrotic tissue separating more quickly than in the control group [

30]. Studies by Budak and Çakıroğlu [

31] support this, showing that Manuka honey increases cell division, leading to faster reepithelialization, as evidenced by Ki-67 immunohistochemistry in mice models.

A microbiological study was performed, and although no pathogenic bacteria were detected, only saprophytic organisms were found. This aligns with Manuka honey’s known antimicrobial properties[

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], which likely contributed to the absence of infection signs. Previous studies have shown that Manuka honey is effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including resistant strains, and reduces biofilm formation, as demonstrated by Alandelajniet al.[

37]

In burn treatment, managing superficial and deep dermal wounds is well established, but intermediate-depth burns, which combine features of both, pose a greater challenge [

38]. Our study used FLIR One thermography on the first post-intervention day to categorize burns based on healing times. Superficial burns healed within 14 days, intermediate burns between 14 and 21 days, and deep dermal burns took over 21 days to heal. The temperature difference between intact skin and deep dermal burns was 2.66°C, indicating the need for surgical intervention. FLIR One thermography proved to be a non-invasive, cost-effective tool that could aid in treatment decisions, particularly for mixed-depth burns [

39,

40].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

The study was conducted entirely from an experimental perspective. All animal experiments were performed according to the European Directive for Protection of the Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes 86/609/EES and the principles of Good Laboratory Practice. Study approval was obtained from the Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection (Belgrade, Serbia; No. 323-07-04449/2021-05).

4.2. Animals

Nine healthy experimental animals (pigs) of the Landrace breed, female, with a body mass of 25–30 kilograms, aged between two and three months, and weaned, were randomly selected for the experiment. The initial examination was conducted at the Institute of Livestock Belgrade-Zemun in a clinic designated for examining and treating experimental animals. Before starting the experiment, a thorough assessment was performed to ensure that the animals did not have any health issues that would prevent the experiment from being carried out. This included checking for any systemic diseases or other comorbidities. Seven days before the experiment began, the animals were placed in individual cages with unrestricted access to food and water. The animals were kept in a room ranging from 20 to 25 °C, with air humidity of 55% ± 1.5%, and a 12-hour light-dark cycle. No animals developed any other comorbidity or burn disease after the burn injuries, so initially, no animal was automatically excluded from the study and did not need to be treated by the veterinarian in charge of the welfare of the experimental animals.

4.3. Selection of Topical Agent

The preparation used in this study is an antibiotic ointment, combining Neosporin® (bacitracin zinc, neomycin sulfate and polymyxin B sulfate produced by Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc., Skillman, NJ,USA).This combination is considered the gold standard for treating pediatric and adult populations, as bacitracin targets gram-positive bacteria, neomycin targets both gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and polymyxin B targets gram-negative bacteria. The use of antibiotic ointments did not disrupt epithelialization. Algivon plus® - manuka honey (Advancis Medical, United Kingdom) represent alginate dressing impregnated with 100% Manuka honey with a slow release of honey whilst maintaining the integrity of the dressing.

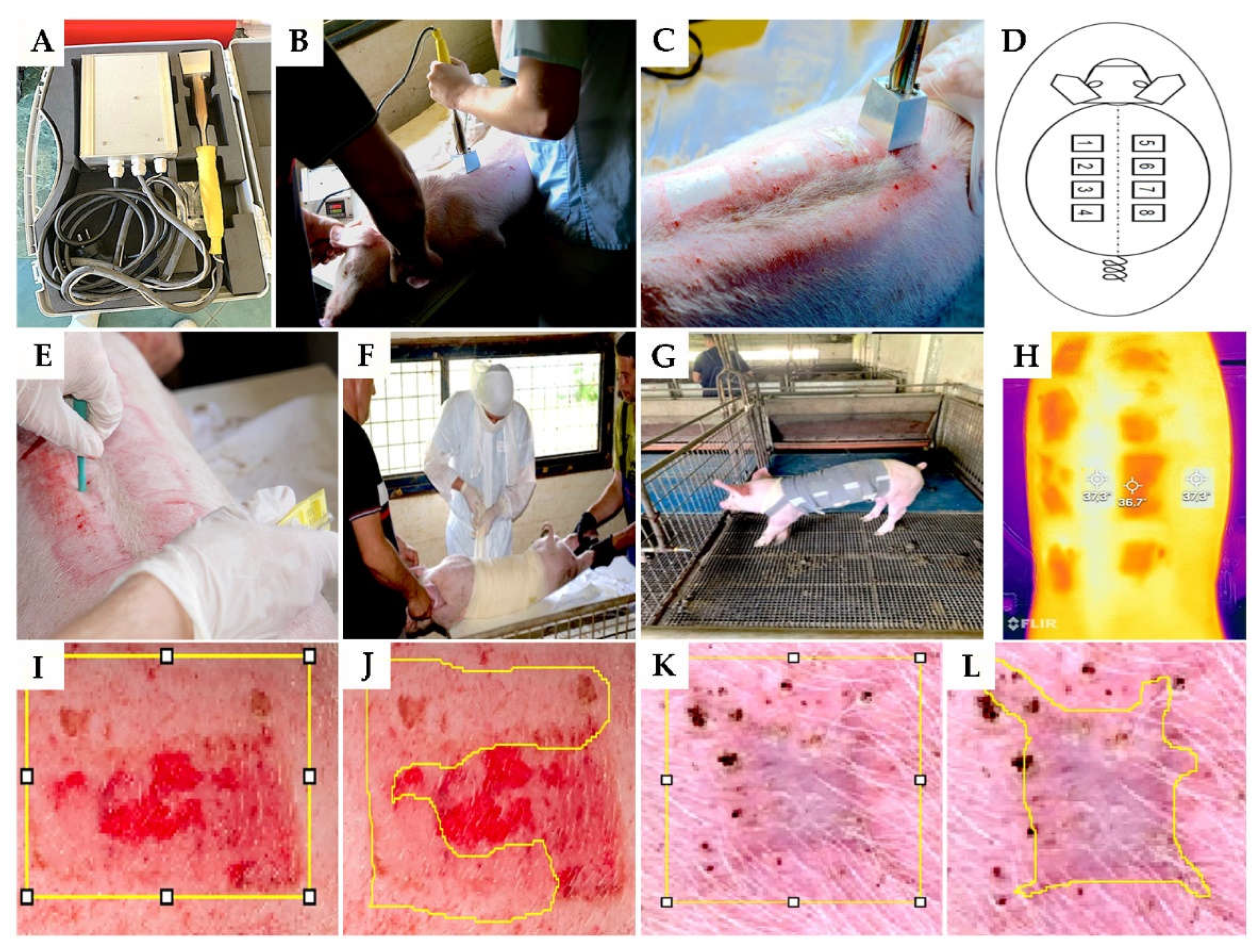

4.4. Wound Model

The animals were introduced to general anaesthesia with Diazepam Sopharma® - diazepam in dose 1.1 mg/kg (Sopharma AD, Bulgaria) and Vetaketam® - ketamine in dose 15 mg/kg (VET-AGRO, Poland) applied intramuscularly in the neck. Then, the skin on the back was shaved. After that, the operative field was prepared with an aerosol, not rubbing, to avoid causing skin hyperemia that can affect the depth of the inflicted burn. Then, contact burns were applied with a brass attachment of a heater heated to 92°C in contact with the skin for 15 seconds (

Figures 1A, 1B and 1C). A total of 8 burns were formed on each pig (dimensions 47mm by 47mm), four on the left and four on the right side of the back. The burns were 20mm apart and 30mm from the spinal column to have approximately the same dermis thickness (

Figure 1D). In total, there were 72 burned surfaces across nine animals. The burn wounds were divided into fields numbered 1, 3, 5, and 7. Each pig received treatment with Manuka honey, representing the

Manuka honey group.Conversely, fields numbered 2, 4, 6, and 8 were treated with a combination of antibiotic ointments, representing the

Control group. After photographing the burns, each one was covered with a transparent polyurethane film, over which several layers of gauze were placed and positioned with wide circular bandages (

Figure 1F). The bandage placed in this way is protected with a protective coating (

Figure 1G). Additionally, each pig was housed in a cage of approximately 4 square meters to prevent mutual injuries among the animals (

Figure 1G). For the initial seven days following the application of the burn wounds, postoperative pain relief was administered using

Aanalgin®- metamizole sodium (Alkaloid, North Macedonia) at a dose of 25mg/kg, administered via intramuscular injection. Deep dermal burns are characterized by a consistent whitish colour in the central area, accompanied by a peripheral trail and surrounding redness, which were observed during a clinical examination.

On the 3rd, 7th, 10th, 14th, 17th, 20th, 23rd and 30th day from burn initiation, the animals were changed mentioned topical treatment ( Algivon plus and antibiotic ointments) with photo documentation of wound. Before topical treatment we make a smear of wound for bacteriological analysis.

4.5. Infrared Camera (FLIR One Pro)

A

FLIR One Pro infrared camera (FLIR, Sweden) connected to a smartphone was used for thermography at each bandaging.The temperature difference between the tissue in the burned area and the undamaged skin was measured 1

st day after intervention and noted (

Figure 1H).

Figure 5.

Illustrations of the experimental procedure. Heater and its application (A, B and C); schema of burn place application (D); technique of tissue sampling (E); bandaging the wound (F); the housing of animals (G); representative photograph of skin and wound using an infrared camera (H); measuring of the whole area (yellow borders on picture I) and reepithelialization area (yellow borders on picture - J) of the wound at 30th post thermal injury; measuring of the whole area (yellow borders on picture - K) and contraction area (yellow borders on picture - L) of the wound at 60th post thermal injury;.

Figure 5.

Illustrations of the experimental procedure. Heater and its application (A, B and C); schema of burn place application (D); technique of tissue sampling (E); bandaging the wound (F); the housing of animals (G); representative photograph of skin and wound using an infrared camera (H); measuring of the whole area (yellow borders on picture I) and reepithelialization area (yellow borders on picture - J) of the wound at 30th post thermal injury; measuring of the whole area (yellow borders on picture - K) and contraction area (yellow borders on picture - L) of the wound at 60th post thermal injury;.

4.6. Tissue Samples Biopsy

Skin biopsies were taken using a 3 mm skin biopsy puncher on the 3

rd, 7

th, 10

th, 17

th, 20

th, 23rd, and 60

th days (

Figure 1E). The biopsy on the 3

rd day was used to determine the depth of the burn wound. Biopsies from the 7

th to the 23

rd day were taken to monitor the inflammatory and proliferative phases of healing. On the 60

th day, biopsies were taken to evaluate the scar maturation phase.

4.7. Histology Tissue Processing

Tissue samples obtained with a bioptome were dehydrated through increasing alcohol concentrations (70, 80, 95, and 100%) and cleared with xylene, followed by embedding in paraffin. Paraffin moulds were cut on a rotatory microtome (Sakura, Japan) to a thickness of 5μm. All slides were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), Masson's trichrome (MTS) and Picrosirius Red (PRS) histochemical staining and the following immunohistochemical markers: rabbit anti-AE1/AE3 in a 1:50 dilution (Lab Vision; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA); rabbit anti-Ki67 in a 1:300 dilution (Abcam; Cambridge, United Kingdom); and rabbit anti-Iba1 in a 1:8000 dilution (Abcam; Cambridge, United Kingdom). For a visualization, we used Mouse and Rabbit EnVision Detection Systems, Peroxidase/DAB detection IHC kit (DAKO Agilent; United Kingdom). A retrieval reaction included treatment with citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 minutes at 99° C. Antibodies were applied for 60 min at room temperature with Mayer's hematoxylin counterstain and finally mounted with DPX medium (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany). Slide analysis and digitalization were performed using a digital microscope VisionTek® (Sakura, Japan).

4.8. Morphometric Analysis

4.8.1. Measurement of the Reepithelialization Area (REA)

We capture high-resolution images of burns every time we dress them using a Canon EOS 1200d camera (Canon, Japan).Using the free computer software Fiji (Japan) and its plug-in (area), we measured the re-epithelialized skin area (REA)(

Figure 1I,J). REA was presented as the percentage of the re-epithelialized part of the skin to the still unrecovered part, multiplied by 100%.

The evaluation of the scar involved macroscopically calculating the percentage of wound contraction during healing and, consequently, the contraction of the scar (

Figure 1K,L).The aesthetic appearance of the scar was assessed using the Vancouver Scar Scale, which evaluates scars based on several parameters such as pigmentation, vascularity, pliability, and height. This scale helps in quantifying the physical characteristics of scars, providing a systematic approach for assessing their severity and appearance [

40].

4.8.2. Measurement of Histology Morphometric Parameters

After digitizing histology slides using the free computer software Fiji (Japan) and its plug-in (distance), we measured the values of the necrotic debris thickness, epidermal thickness, epidermal ridges thickness, granulation tissue thickness, and reticular dermis thickness. For each digitalized slide, we performed three measurements, which were finally expressed as a mean value presented in micrometres (µm).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical methods and statistical hypothesis testing were used to analyze the primary data. The descriptive statistical methods included measures of central tendency (arithmetic mean), measures of variability (standard deviation), and relative numbers (structure indicators). For testing statistical hypotheses, parametric statistical analyses (One Way ANOVA, Post hoc Tukey test) and nonparametric statistical analyses (Fisher’s exact test, Mann-Whitney U test, and Kruskal-Wallis H test) were used. Hypotheses were tested at a level of statistical significance (α level) of 0.05. The results were presented in tables and graphs. Data was processed using a standard statistical package (IBM SPSS Statistics 26). Microsoft Office Word 2007 software was used to create charts and tables. This work presented results with photographs, microphotographs, tables, and graphs.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, while this study suggests that applying Manuka honey in alginate may enhance the healing process of burn wounds compared to standard antibiotic ointments, the data provided is insufficient to draw definitive conclusions. The potential healing effects of Manuka honey may be attributed to its antimicrobial and antioxidant properties and hydrogel formation, which could create a favourable environment for wound repair. Although burns treated with Manuka honey appeared to show some cosmetic and pathohistological improvements, including reduced granulation tissue and thinner epidermis, these observations require further data and validation. The re-epithelialization process was noted to be faster in the Manuka honey group, suggesting a possible positive impact on the healing environment.

The study also mentions the potential use of forward-looking infrared (FLIR) thermography as a tool for assessing burn wound depth. Still, additional research is needed to confirm its clinical utility. We acknowledge that Algivon is a well-known product, and no conflict of interest exists related to its use in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P.,M.J. and I.C.; methodology, B.P., M.J. and I.C., software, I.C. validation I.C.,N.D.; formal analysis, R.R. and I.C.; investigation, B.P.,I.C.,V.P.,B.G. and N.D.; resources,A.S., N.D.; data curation, B.P and I.C..; writing—original draft preparation, B.P.; writing—review and editing, B.P. and I.C.; visualization, I.C.; supervision, M.J.,I.C. project administration,B.P.,N.D., A.S., I.C.; funding acquisition,B.P.,N.D. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ministry of Agriculture and Environmental Protection (Belgrade, Serbia; No. 323-07-04449/2021-05) approved the animal study protocol.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the raw data supporting this article's conclusions available upon request.

References

- Jeschke, M.G.; van Baar, M.E.; Choudhry, M.A.; Chung, K.K.; Gibran, N.S.; Logsetty, S. Burn injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanney, L.B.; Wenczak, B.A.; Lynch, J.B. Progressive burn injury documented with vimentin immunostaining. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996, 17, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riordan, C.L.; McDonough, M.; Davidson, J.M.; Corley, R.; Perlov, C.; Barton, R.; et al. Noncontact laser Doppler imaging in burn depth analysis of the extremities. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003, 24, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, K.I.; Malik, M.A.; Aslam, A. Honey compared with silver sulphadiazine in the treatment of superficial partial-thickness burns. Int Wound J. 2010, 7, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Wu, M.; Han, F.; et al. Evaluation of total antioxidant activity of different floral sources of honeys using crosslinked hydrogels. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2019, 14, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.; Dissemond, J.; Kim, S.; Willy, C.; Mayer, D.; Papke, R.; et al. Consensus on Wound Antisepsis: Update 2018. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2018, 31, 28–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, R.; Lu, Q.; Hao, P.; Xu, A.; Zhang, J.; et al. Biochemical properties, antibacterial and cellular antioxidant activi-ties of buckwheat honey in comparison to manuka honey. Food Chem. 2018, 252, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, B.; Etemadian, S.; Goli, H.; Bahonar, S.; Gholami, S.; Karami, P.; et al. Construction and analysis of alginate-based honey hydrogel as an ointment to heal of rat burn wound related infections. Int. J. Burn Trauma. 2018, 8, 88–97. [Google Scholar]

- Almasaudi, S. The antibacterial activities of honey. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021, 28, 2188–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neres Santos, A.M.; Duarte Moreira, A.P.; Piler Carvalho, C.W.; et al. Physically cross-linked gels of PVA with natural poly-mers as matrices for Manuka honey release in wound-care applications. Materials (Basel) 2019, 12, E559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucekova, M.; Valachova, I.; Kohutova, L.; Prochazka, E.; Klaudiny, J.; Majtan, J. Honeybee glucose oxidase--its expression in honeybee workers and comparative analyses of its content and H2O2-mediated antibacterial activity in natural honeys. Naturwissenschaften. 2014, 101, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbuchea, A. Up-to-dat use of honey for burns treatment. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2014, 27, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, T.P.; Eaglstein, W.H.; Davis, S.C.; Mertz, P. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2001, 9, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branski, L.K.; Rainer, M.; Jeschke, M.G. A porcine model of full thickness burn, excision and skin autografting. Burns. 2008, 34, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, K.Q.; Engrav, L.H.; Gibran, N.S.; Cole, J.K.; Matsumura, H.; Piepkorn, M.; et al. The female, red Duroc pig as an animal model of hypertrophic scarring and the potential role of the zones of skin. Burns 2003, 29, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, M.; Hilliard, C.; Peel, G.; Crispino, G.; Geraghty, R.; OʼCallaghan, G. Management of pediatric skin-graft donor sites: a randomized controlled trial of three wound care products. J Burn Care Res. 2015, 36, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbu, A.; Neamtu, B.; Zăhan, M.; Iancu, G.M.; Bacila, C.; Mireșan, V. Current Trends in Advanced Alginate-Based Wound Dressings for Chronic Wounds. J Pers Med. 2021, 11, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konop, M.; Rybka, M.; Drapała, A. Keratin Biomaterials in Skin Wound Healing, an Old Player in Modern Medicine: A Mini Review. Pharmaceutics. 2021, 13, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, D.T. Distinct Fibroblasts in the Papillary and Reticular Dermis: Implications for Wound Healing. Dermatol. Clin. 2017, 35, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.C.; Tomblyn, S.; Isaac, K.M.; Kowalczewski, C.J.; Burmeister, D.M.; Burnett, L.R.; et al. Ciprofloxacin-loaded keratin hydrogels reduce infection and support healing in a porcine partial-thickness thermal burn. Wound Repair Regen. 2016, 24, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, N.; Yadav, R. Manuka honey: A promising wound dressing material for the chronic nonhealing discharging wounds: A retrospective study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2021, 12, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, O.H.; Nisbet, C.; Yarim, M.; Guler, A.; Ozak, A. Effects of three types of honey on cutaneous wound healing. Wounds. 2010, 22, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ranzato, E.; Martinotti, S.; Burlando, B. Honey exposure stimulates wound repair of human dermal fibroblasts. Burns Trauma. 2013, 1, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, Y.; Mukai, K.; Nasruddin, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Komatsu, E.; Iuchi, T.; Kitayama, Y.; et al. Evaluation of the effects of honey on acute-phase deep burn wounds. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013, 2013, 784959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonks, A.; Cooper, R.A.; Price, A.J.; Molan, P.C.; Jones, K.P. Stimulation of TNF-alpha release in monocytes by honey. Cytokine 2001, 14, 240–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maddocks, S.E.; Lopez, M.S.; Rowlands, R.S.; Cooper, R.A. Manuka honey inhibits the development of Streptococcus pyogenes biofilms and causes reduced expression of two fibronectin binding proteins. Microbiology (Reading). 2012, 158, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethin, G.; Cowman, S. Manuka honey vs hydrogel – a prospective,open label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial to compare desloughing efficacy and healing outcomes in venous ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2009, 18, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.E. Wound healing properties of honey. Br J Surg. 1988, 75, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bang, L.; Buntting, C.; Molan, P. The effect of dilution on the rate of hydrogen peroxide production in honey and its implications for wound healing. J Altern Complement Med. 2003, 9, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molan, P.C. Debridement of wounds with honey. Journal of Wound Technology. 2009, 5, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Budak, Ö.; Çakıroğlu, H. Examination the effects of chestnut and Manuka Honey for wound healing on mice experimental model. Medical Science and Discovery 2022, 9, 170–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Carter, D.A.; Turnbull, L.; Rosendale, D.; Hedderley, D.; Stephens, J.; et al. The effect of New Zealand kanuka, manuka and clover honeys on bacterial growth dynamics and cellular morphology varies according to the species. PLoS One. 2013, 8, e55898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.M.; Cutting, K.F. Antibacterial honey (Medihoney ™): Invitro activity against clinical isolates of MRSA, VRE, and other multiresistant gram-negative organisms including Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Wounds. 2007, 19, 231–236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Molan, P.C. The evidence and the rationale for the use of honey as a wound dressing. Wound Practice and Research. 2011, 19, 204–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.A.; Jenkins, L.; Henriques, A.F.; Duggan, R.S.; Burton, N.F. Absence of bacterial resistance to medical-grade manuka honey. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010, 29, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Gasparrini, M.; Forbes-Hernández, T.Y.; Mazzoni, L.; Giampieri, F. The Composition and Biological Activity of Honey: A Focus on Manuka Honey. Foods. 2014, 3, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alandejani, T.; Marsan, J.; Ferris, W.; Slinger, R.; Chan, F. Effectiveness of honey on Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009, 141, 114–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrière, M.E.; Haas, L.E.M.; Pijpe, A.; Meij-de Vries, A.; Gardien, K.L.M.; Zuijlen, P.P.M.; Jaspers, M.E.H. Validity of thermography for measuring burn wound healing potential. Wound Repair Regen. 2020, 28, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearn, C.; Lee, K.C.; Hardwicke, J.; Allouni, A.; Bamford, A.; Nightingale, P.; Moiemen, N. Prospective comparative evaluation study of Laser Doppler Imaging and thermal imaging in the assessment of burn depth. Burns 2018, 44, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaspers, M.E.H.; Carrière, M.E.; Meij-de Vries, A.; Klaessens, J.H.G.M.; van Zuijlen, P.P.M. The FLIR ONE thermal imager for the assessment of burn wounds: Reliability and validity study. Burns 2017, 43, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baryza, M.J.; Baryza, G.A. The Vancouver Scar Scale: an administration tool and its interrater reliability. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1995, 16, 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).