Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

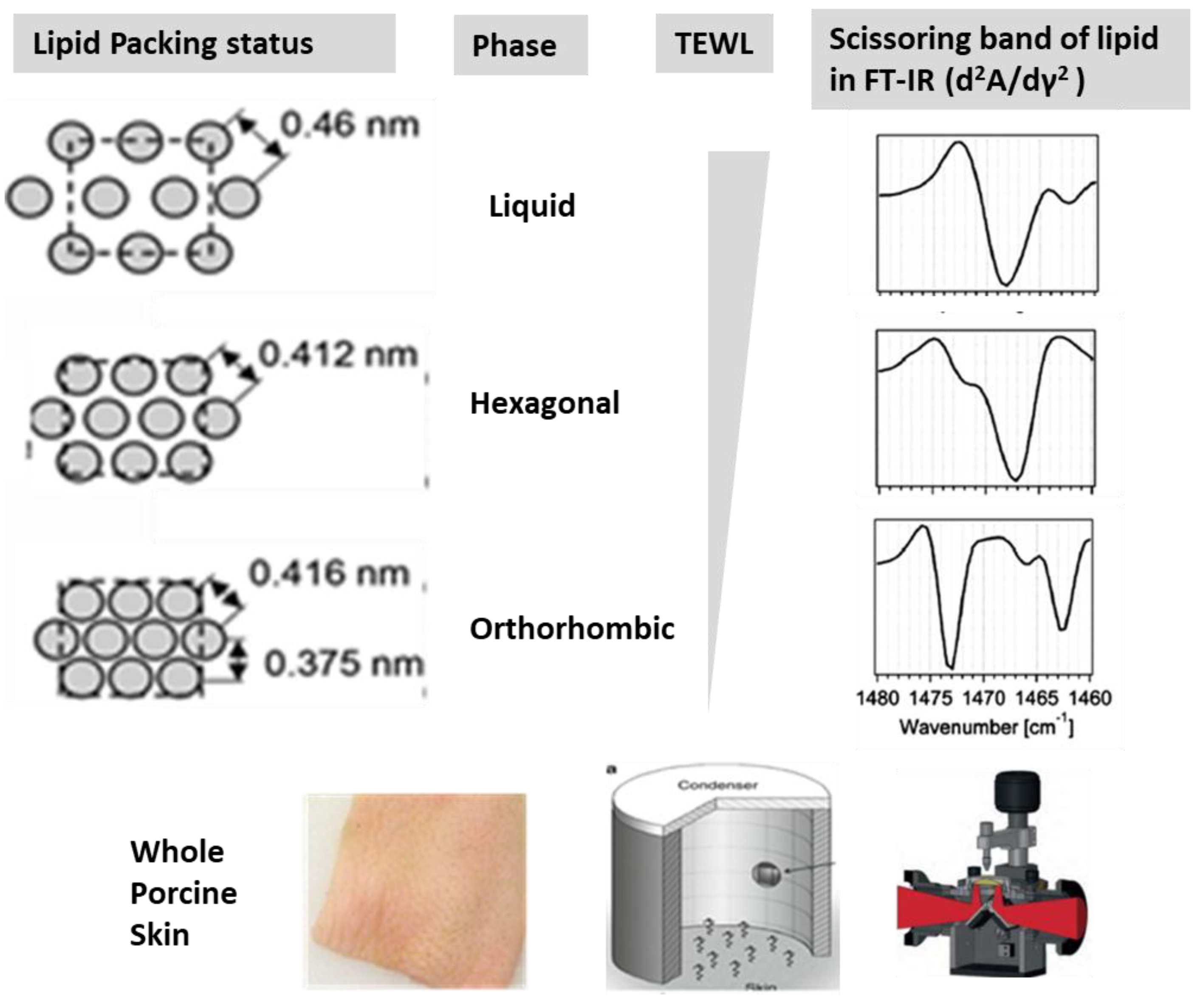

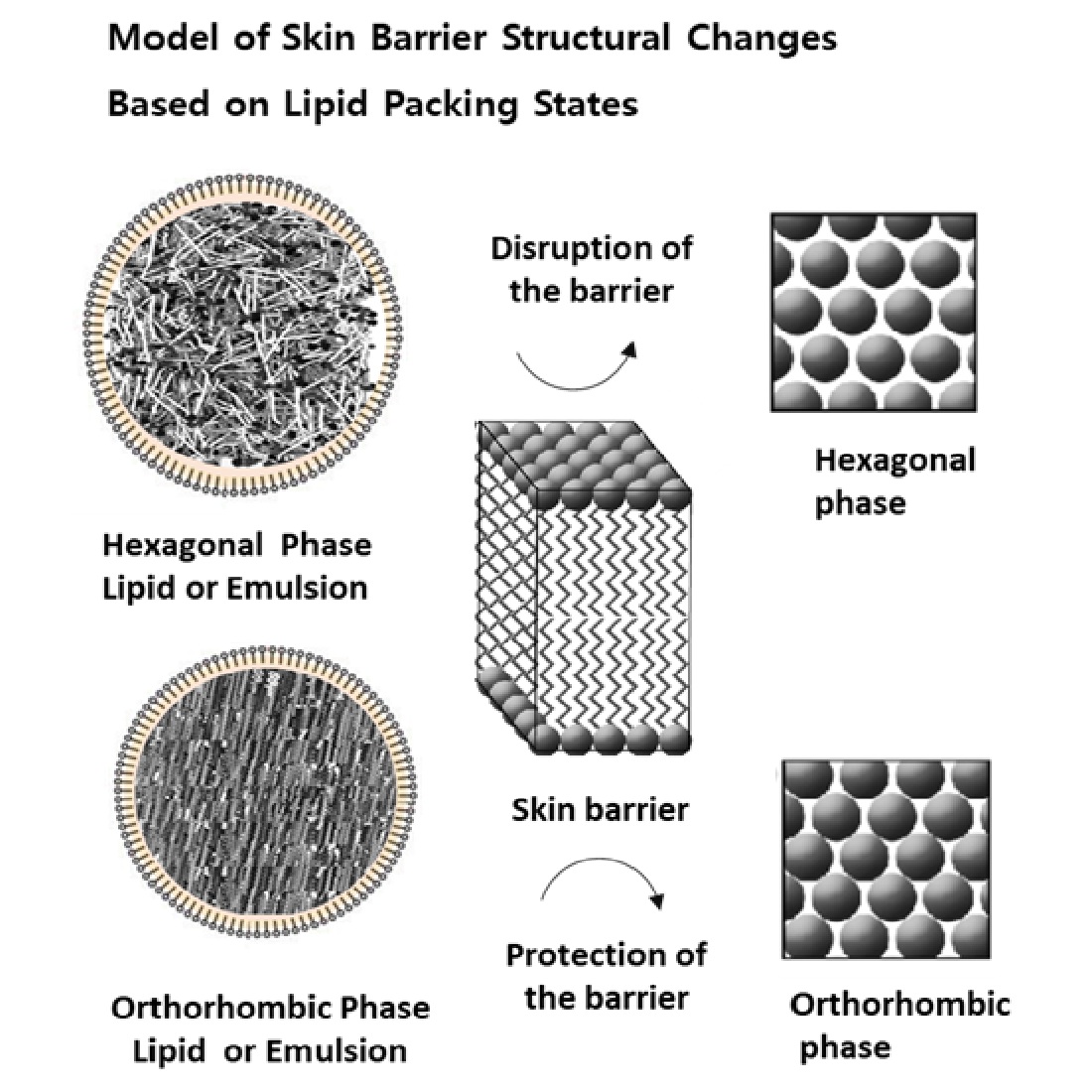

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Materials

Sample Treatment for Analyzing the Impact on Skin Barrier

ATR-FT-IR Measurement

Statistical Processing

3. Results

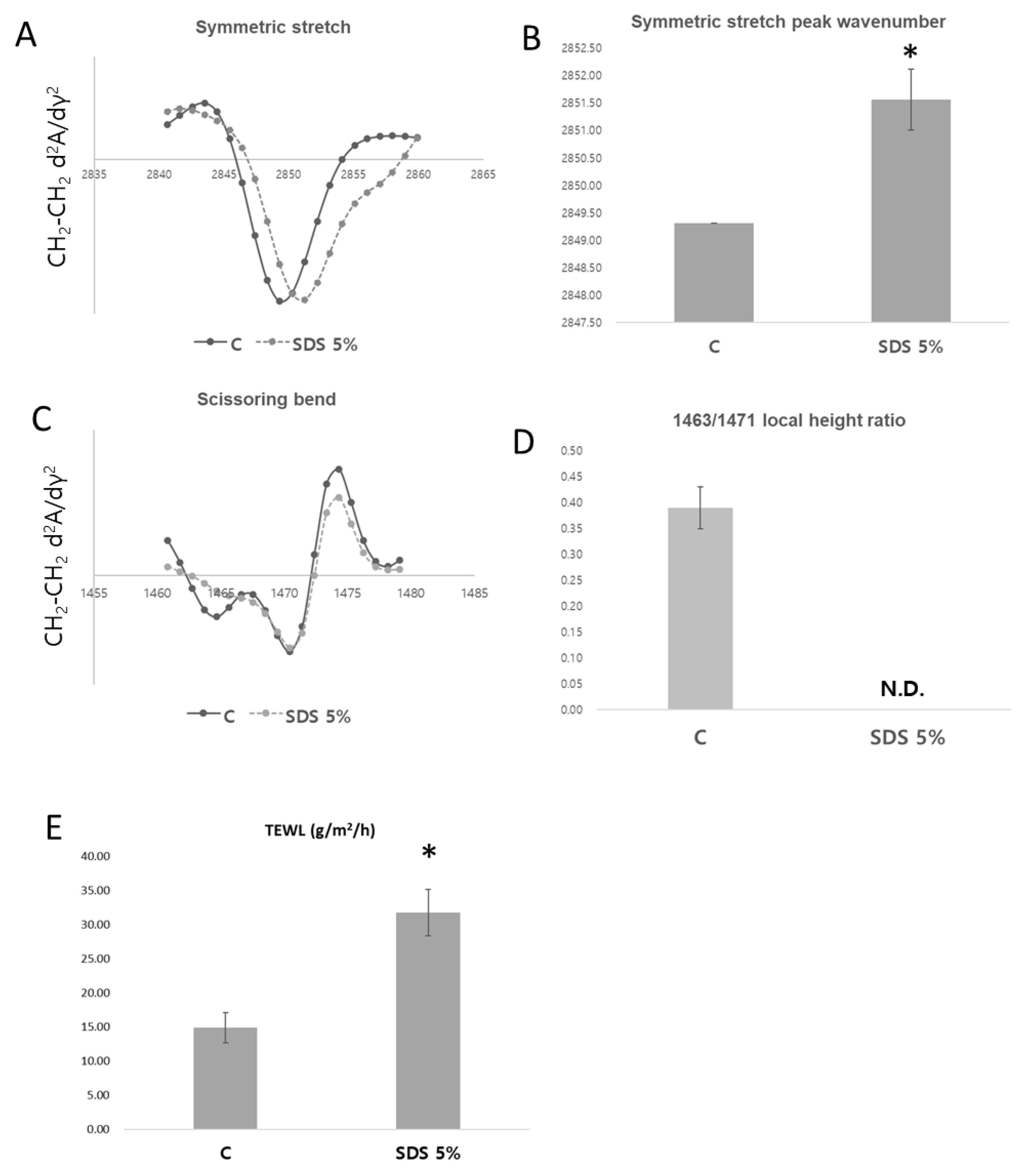

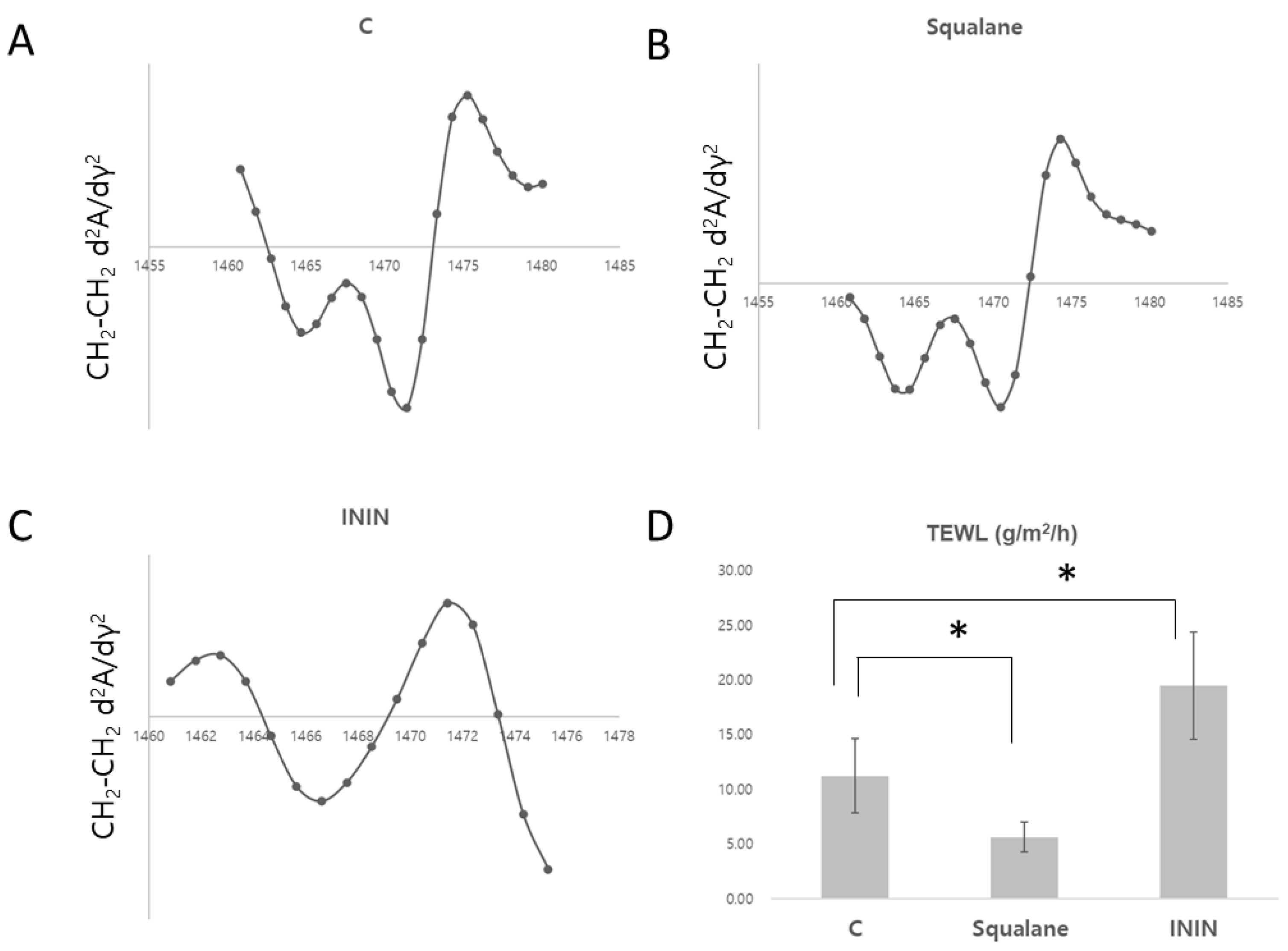

Analysis of Skin Barrier Function and Lipid Packing Structure in Porcine Skin Following SDS Treatment

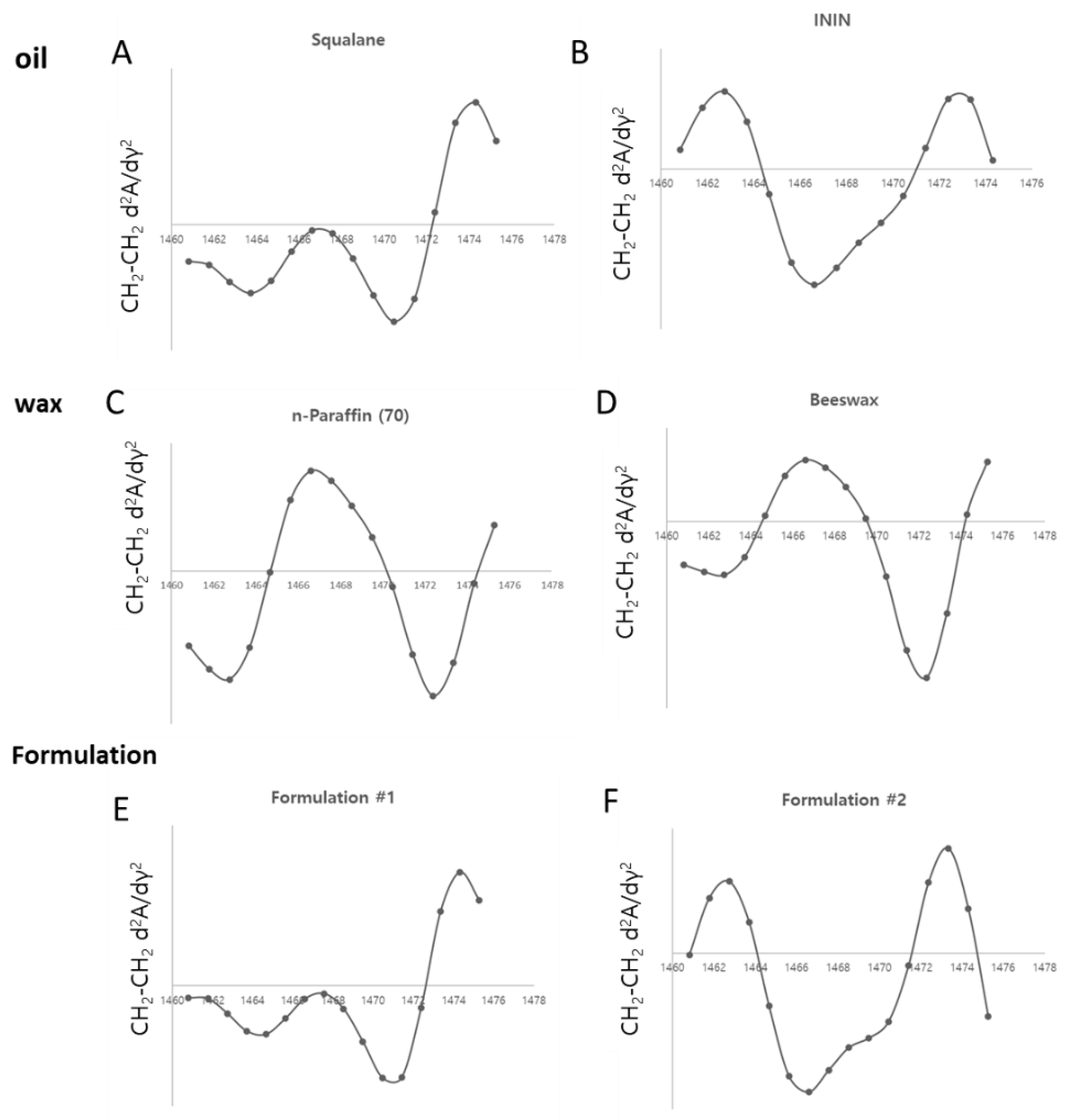

Analysis of Lipid Packing Structure in Cosmetic Oils and Formulations Using FT-IR

Impact of Oil Packing Structures on Skin Barrier Function and Lipid Structures

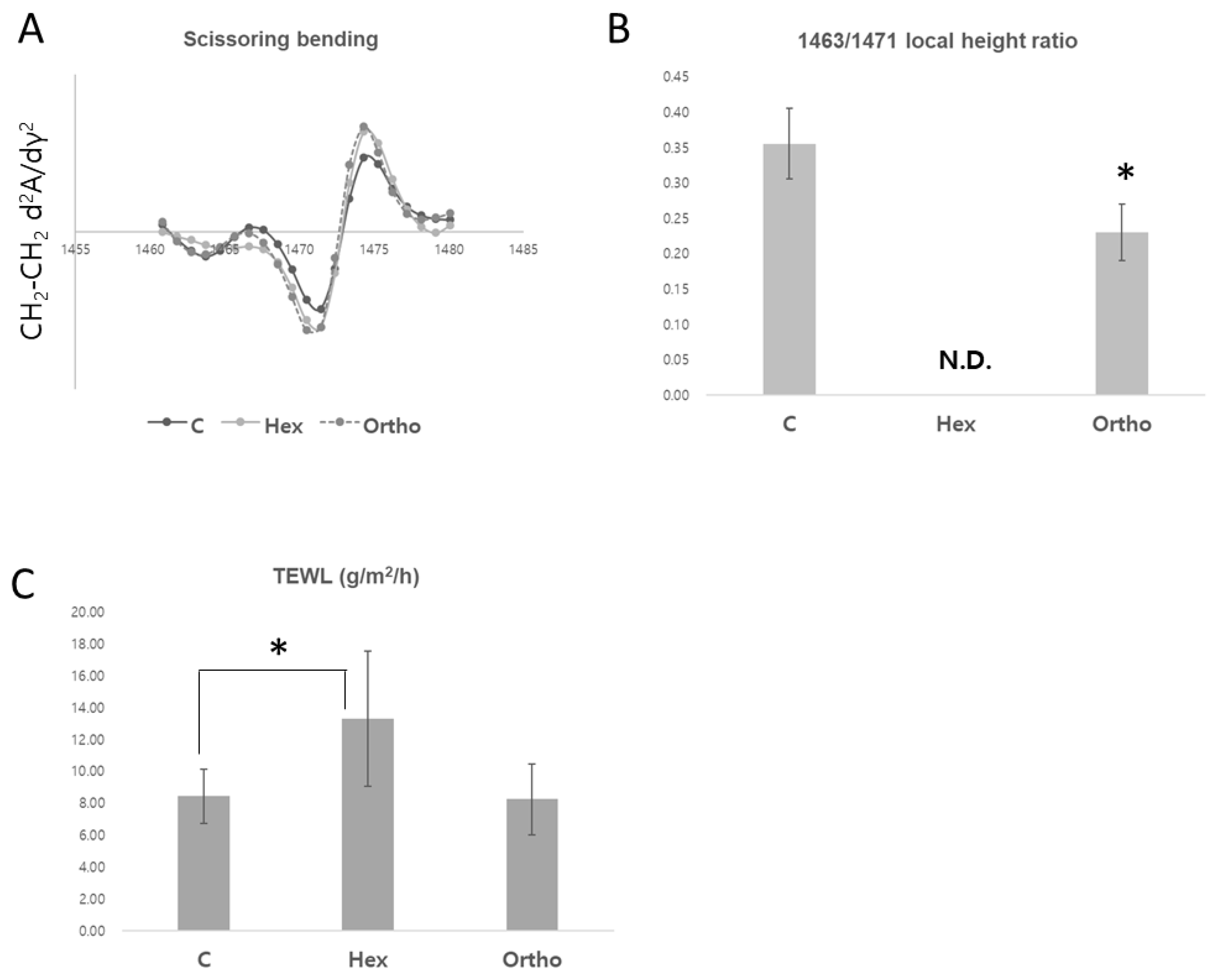

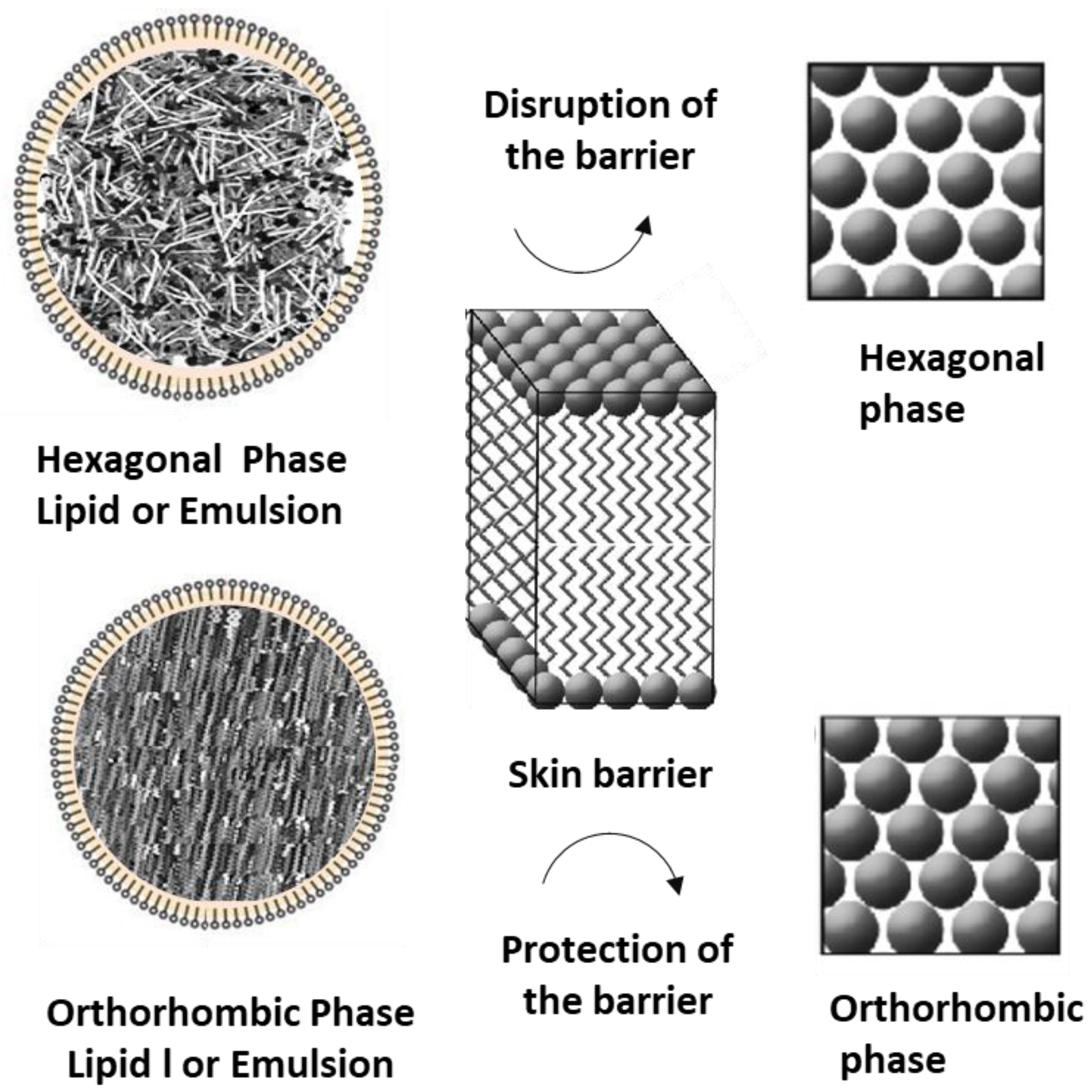

Effects of Emulsion Formulations on Skin Barrier Function: A Comparative Analysis of Orthorhombic and Hexagonal Lipid Packing Structures

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bouwstra, J. A.; Ponec, M. The Skin Barrier in Healthy and Diseased State. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2006, 1758, 2080–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coderch, L.; Lopez, O.; de la Maza, A.; Parra, J. L. Ceramides and Skin Function. Am J Clin Dermatol 2003, 4, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vietri Rudan, M.; Watt, F. M. Mammalian Epidermis: A Compendium of Lipid Functionality. Frontiers in Physiology. 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damien, F. Boncheva, M. The Extent of Orthorhombic Lipid Phases in the Stratum Corneum Determines the Barrier Efficiency of Human Skin In Vivo. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2010, 130, 611–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamad, F.; Stamatas, G. N. Directional Assessment of the Skin Barrier Function in Vivo. Skin Research and Technology 2023, 29, e13346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensack, R. D.; Michniak, B. B.; Moore, D. J.; Mendelsohn, R. Infrared Kinetic/Structural Studies of Barrier Reformation in Intact Stratum Corneum Following Thermal Perturbation. Appl Spectrosc 2006, 60, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H.; Jun, S. H.; Yeom, J.; Park, S. G.; Lee, C. K.; Kang, N. G. Optical Clearing Agent Reduces Scattering of Light by the Stratum Corneum and Modulates the Physical Properties of Coenocytes via Hydration. Skin Research and Technology 2018, 24, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncheva, M.; Damien, F.; Normand, V. Molecular Organization of the Lipid Matrix in Intact Stratum Corneum Using ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2008, 1778, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkers, T.; Visscher, D.; Gooris, G. S.; Bouwstra, J. A. Topically Applied Ceramides Interact with the Stratum Corneum Lipid Matrix in Compromised Ex Vivo Skin. Pharm Res 2018, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharekova, M.; Schalkwijk, J.; Van De Kerkhof, P. C. M.; Van De Valk, P. G. M. Effect of a Lipid-Rich Emollient Containing Ceramide 3 in Experimentally Induced Skin Barrier Dysfunction. Contact Dermatitis 2002, 46, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-H.; Park, W. R.; Kim, J. H.; Cho, E. C.; An, E. J.; Kim, J.-W.; Oh, S.-G. Fabrication of Pseudo-Ceramide-Based Lipid Microparticles for Recovery of Skin Barrier Function. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2012, 94, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashizume, E.; Nakano, T.; Kamimura, A.; Morishita, K. Topical Effects of N-Acetyl-L-Hydroxyproline on Ceramide Synthesis and Alleviation of Pruritus. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2013, 6, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbet, S.; Mahalingam, H.; Gfeller, C. F.; Biggs, E.; Lucas, S.; Thompson, M.; Cargill, M. R.; Moore, D.; Bielfeldt, S. Cosmetic Benefit of a Biomimetic Lamellar Cream Formulation on Barrier Function or the Appearance of Fine Lines and Wrinkles in Randomized Proof-of-Concept Clinical Studies. Int J Cosmet Sci 2019, 41, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demski, K.; Ding, B.-J.; Wang, H.-L.; Tran, T. N. T.; Durrett, T. P.; Lager, I.; Löfstedt, C.; Hofvander, P. Manufacturing Specialized Wax Esters in Plants. Metab Eng 2022, 72, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, V. K.; Sharma, R. K. Palladium-Nanoparticles-Intercalated Montmorillonite Clay: A Green Catalyst for the Solvent-Free Chemoselective Hydrogenation of Squalene. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J. D. A.; Cardoso, F. D. P.; Lachter, E. R.; Estevão, L. R. M.; Lima, E.; Nascimento, R. S. V. Correlating Chemical Structure and Physical Properties of Vegetable Oil Esters. J Am Oil Chem Soc 2006, 83, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H. B.; Annapure, U. S. Triglycerides of Medium-Chain Fatty Acids: A Concise Review. J Food Sci Technol 2023, 60, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilgram, G. S. K.; Vissers, D. C. J.; Van Der Meulen, H.; Pavel, S.; Lavrijsen, S. P. M.; Bouwstra, J. A.; Koerten, H. K. Aberrant Lipid Organization in Stratum Corneum of Patients with Atopic Dermatitis and Lamellar Ichthyosis. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2001, 117, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieppo, L.; Saarakkala, S.; Närhi, T.; Helminen, H. J.; Jurvelin, J. S.; Rieppo, J. Application of Second Derivative Spectroscopy for Increasing Molecular Specificity of Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic Imaging of Articular Cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012, 20, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlings, A. V.; Lombard, K. J. A Review on the Extensive Skin Benefits of Mineral Oil. Int J Cosmet Sci 2012, 34, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lee, S.-H. A Study on the Enhancement of Barrier Function and Improvement of Lipid Packing Structure in a 3D Skin Model by Ginsenoside Rg3. Journal of the Society of Cosmetic Scientists of Korea 2023, 49, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).