1. Introduction

According to data from the International Embryo Transfer Society (IETS), global IVEP in sheep increased by 62.3% between 2022 and 2023 [

1]. This trend reflects a paradigm shift from traditional

in vivo embryo production to

in vitro embryo production (IVEP), driven by the latter’s capacity to enhance production efficiency, shorten reproductive cycles, and improve genetic selection precision. The IVEP process comprises several critical stages:

in vitro oocyte maturation (IVM),

in vitro fertilization (IVF), and

in vitro embryo culture (IVC) to the blastocyst stage, followed by embryo transfer or cryopreservation.

Blastocyst rates in sheep IVEP typically range from 15% to 79% [

2], influenced by complex factors including culture media [

3,

4], follicle size [

4,

5,

6], donor reproductive status, semen quality [

7,

8,

9], oocyte retrieval methods [

10,

11,

12], and breeding season [

12,

13]. Notably, seasonal variations in embryo yields have been widely documented, with oocytes collected during breeding seasons exhibiting superior developmental competence compared to non-breeding periods [

12,

13,

14]. Seasonal effects on fertilization, cleavage, and blastocyst rates in sheep IVEP are well-established [

15,

16,

17,

18], a phenomenon also observed in goats, buffalo, and cats [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. However, existing studies predominantly rely on abattoir-derived ovarian oocytes, which introduce heterogeneity due to variable retrieval techniques, transportation conditions (time/temperature), and unstandardized follicle selection [

23]. Furthermore, the absence of follicular hormone induction procedure in such oocytes limits their representativeness for commercial production systems. Most importantly, there is a lack of reports analyzing the effects of season and breed on the efficiency of large-scale commercial sheep

in vitro embryo production.

Sheep, as seasonally polyestrous species, exhibit reproductive efficiency modulated by photoperiodic changes [

18]. In the Northern Hemisphere, breeding seasons include transitional (June - September) and peak periods (September - December) [

16]. The photoperiod influences the reproductive activity of ewes by altering

in vitro hormone concentrations, thereby modifying oocyte competence. Studies have shown that reduced daylight leads to decreased retinal nerve activity, which inhibits excitation of the superior cervical ganglion. This, in turn, reduces the inhibitory effect on the pineal gland. The pineal gland transmits environmental light information to various parts of the body while synthesizing large amounts of melatonin—a modified amino acid that plays a critical role in maintaining circadian rhythms and reproductive function [

29,

30]. The increase in melatonin further stimulates the rise in GnRH levels, subsequently leading to elevated LH and FSH levels, which trigger cyclical reproductive changes [

31,

32].

Despite these findings, breed-specific responses to seasonal variations remain inconsistent across studies, likely confounded by environmental and genetic factors. Therefore, it is necessary to fully consider the combined effects of season and breed when analyzing the efficiency of large-scale commercial sheep in vitro embryo production.

This study investigates the seasonal and breed-specific impacts on oocyte retrieval efficiency, oocyte quality and embryo development rates in sheep large-scale commercial LOPU-IVEP systems. In addition, a systematic analysis was conducted on the embryo transfer pregnancy rates of different breeds in different seasons. We aim to establish a comprehensive correlation between season, breed and efficiency of sheep IVEP, thereby advancing strategies for commercial embryo production and enhancing sheep breeding efficiency.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals, Location, and Time

The ewes were fed in the Inner Mongolia Sino sheep Technology Co., Ltd., Wulanhua Town Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia, China (111:66E, 41:55N). All animals in the semi-intensive farms were kept indoors during the night and some part of the day and were moved to the pastures during some period of the day, and all animals were fed with roughage, silage, and concentrates, in combination with grazing. Each donors had health and estrous cycling of an expected duration.

2.2. Oocyte Collection

Oocytes were collected by LOPU sessions in this study [

10]. Each animal was deprived of food and water in preparation for anesthesia before 12 hours. All of sheep used the same method of general anesthesia. The donors were anaesthetized with 0.12 mL/Kg anesthetic mixture (named Su-Mian-Xin II or Xylazine Hydrochloride Injection, the ingredient is 100 mg/mL xylazine; Institute of Military Veterinary, ChangChun City, China) and then secured in a cradle in the Trendelenburg position. The ventral area was shaved and disinfected with 1% iodine solution (LIRCON, Shandong, China), and then the endoscope was inserted into the abdominal cavity. After endoscopic visualization, the ovaries were manipulated and fixed with grasping forceps. All follicles ≥ 2 mm diameter were aspirated using a 20-G needle mounted on an acrylic pipette connected to a collection tube and a vacuum pump, the vacuum pressure is adjusted to 35–45 mmHg. Oocytes were obtained via aspiration of fluid from ovarian follicles. The follicular fluid was dispensed into a collection tube, which included Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline, DPBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 25 µg/mL gentamicin (Gibco, Grand Island,NY), 50 IU/mL penicillin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and 6 IU/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), at 38℃. In order to avoid adhesion, after each LOPU sessions, the ovary surface was rinsed with metronidazole and a warm saline solution using a pipette introduced through a cannula port [

19]. Then removing all instrument, and a preventative dose of 20 mg/kg antibiotic (named Ampicillin Sodium for Injection, Harbin Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd. General Pharm. Factory, Harbin, China) was injected to each donor.

2.3. Oocyte Evaluation

Oocytes retrieved via LOPU were morphologically graded under a stereomicroscope (SMZ-645; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) following Wieczorek's classification criteria [

26]. The grading system evaluated COC integrity based on cumulus cell layers and cytoplasmic homogeneity in

Figure 1:

Grade A: ≥3 compact cumulus cell layers with homogeneous cytoplasm.

Grade B: 2-3 partially expanded cumulus cell layers with homogeneous cytoplasm.

Grade C: 1 discontinuous cumulus cell layer with homogeneous cytoplasm.

COCs meeting minimum viability thresholds (≥1 intact cumulus cell layer with granular cytoplasm, Grades A-C) were selected for subsequent IVM procedures. This screening protocol ensured exclusion of denuded oocytes and those exhibiting cytoplasmic abnormalities (vacuolization or darkening).

2.4. In Vitro Maturation

The oocytes were washed three times in maturation media, which incubated at 38.6℃ in a humidified environment containing 5% CO2 and 95% air for 24 h. The maturation medium consisted of Medium 199 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 0.02 U/mL FSH (Sansheng, Ningbo, China), 0.02 IU/mL LH (Sansheng, Ningbo, China), 1 μg/mL 17β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich), 100 μM cysteamine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (v/v) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY). And then approximately 50 COCs were incubated in a 4-well culture dish (Thermo Scientific, Roskilde, Denmark) that contained 600 μL same maturation medium covered 300 μL mineral oil (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

2.5. Sperm Preparation, In Vitro Fertilization, and In Vitro Culture

Frozen semen was thawed in a 39℃ water bath for 1 min layered below 700 μL fertilization medium consisting of synthetic oviductal fluid supplemented with 20% estrus sheep serum and 6 IU/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich) in a 15 mL tube. Motile spermatozoa were retrieved from the upper portion after incubated 30 min and centri-fuged at 1500 rpm for 4 min. Supernatant was carefully removed and mixed the sediment. And then viable sperm was diluted achieve a concentration of 2×106 sperm/mL. After COCs IVM 24 h, the cumulus cells were removed with 0.1% hyaluronidase, and transferred oocytes into fertilization medium. Fertilization medium consisted of mSOF (with 2% estrus sheep serum , heparin sodium and gentamicin; Gibco, Grand Island, NY), covered 300 μL mineral oil. And then the sperm sediment was injected into fertilization medium. Oocytes were co-incubated with spermatozoa for 20 h at 38.6℃ in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. After IVF, the denuded and presumptive zygotes were transferred to cultural medium (mSOF, 1% basal medium Eagle’s essential amino acids (v/v), 2% MEM nonessential amino acids (v/v), 1 mM glutamine, and 3 mg/mL BSA) incubated at 38.6℃ in a humidified atmosphere incubator with 5% O2, 5% CO2, and 90% N2. Percentages of zygote cleavage were recorded on day 2, and total blastocyst cell counts, and blastocyst rates were recorded on day 6.

2.6. Embryo Transfer

To ensure that the recipient sheep's reproductive system state and the embryonic development period were concordant when transplanted, the recipient sheep and the donor sheep implanted sponge plugs at the same time. When the donor injected the 5th FSH, the plug was withdrawn and 330 IU PMSG (Pfizer, Now York, America) was intramuscular injected into each recipient sheep Recipient sheep were deprived of food and water 24 h before surgery. The uterine horn of the recipient ewe was found by laparoscopic surgery, and the uterine horn was slowly pulled out of the body to expose the end of the uterine horn. The sterilized paper clip tip was used to puncture and punch holes in the uterine horn, and the transplant needle injected the blastocyst into the uterine horn through the aperture. And each sheep was intramuscularly injected with 2.5 mg progesterone (Sansheng, Ningbo, China).

2.7. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and a probability value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Generalized linear models (GLM) with a Poisson distribution and log-link function were employed to analyze count data, including the number of total, available, grade A, grade B, and grade C COCs per ewe. The models included the fixed effects of breed, season, and their interaction. Proportion data (cleavage rate, blastocyst rate, and developmental efficiency) were arcsine square-root transformed and then analyzed via two-way ANOVA, considering breed, season, and their interaction. For pregnancy outcomes (single- and double-embryo transfer pregnancy rates), a binary logistic regression model was fitted withwith breed, season, and their interaction as categorical predictors. The presented chi-square values are Wald statistics testing the significance of fixed effects in the models..

For significant fixed effects, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted: Tukey's HSD test was applied for ANOVA models, while analyses were performed on estimated marginal means with Sidak adjustment for GLMs (Poisson and logistic regression).

3. Results

3.1. Effects of Breed, Season and Their Interaction

The comprehensive analysis revealed distinct and independent roles of breed and season on the LOPU-IVEP production pipeline (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3). Breed was identified as the primary driver of oocyte recovery and quality, whereas season exerted a more pronounced influence on subsequent embryonic developmental competence and pregnancy outcomes. A significant breed-by-season interaction was detected for key developmental milestones, indicating that the performance of specific breeds varied across different seasons.

Regarding oocyte retrieval, breed had a highly significant (

p < 0.001) impact on the number of total COCs, available COCs, and grade A COCs per ewe (

Table 1,

S1). In contrast, season and the breed-season interaction showed no significant effects on any COC quantity or quality parameters. The seasonal patterns of oocyte yield and quality across different breeds are visually summarized in

Figure 2, which illustrates that East Friesian exhibited consistently superior LOPU efficiency, while Australian White performed significantly lower than other breeds.

For

in vitro embryonic development, both breed and season significantly affected the cleavage rate (

p < 0.001 for both). Season was also a strong determinant of development rate (

p < 0.001). Crucially, a significant breed × season interaction was observed for both cleavage rate (

p = 0.001) and developmental rate (

p = 0.029), indicating that the developmental potential of oocytes from different breeds varied seasonally (

Table 2, S2). Cluster analysis (

Figure 3) further identified Black-headed Suffolk in autumn and winter, and Black-headed Dorper in autumn as superior combinations for embryonic development. Conversely, the combinations of Black-headed Dorper in winter, Australian White in summer, and White-headed Suffolk in spring were identified as the least efficient.

The impact on pregnancy success was highly dependent on the embryo transfer strategy. For single embryo transfer, breed, season, and their interaction all had extremely significant effects on pregnancy rate (

p < 0.001 for all,

Table 3). However, for double embryo transfer, none of these factors reached statistical significance. The detailed pregnancy rates across all breed-season combinations are provided in

Table S3. Notably, for single embryo transfer, the highest pregnancy rates were achieved by Australian White in winter (83.33%) and autumn (79.40%), and by White-headed Suffolk in autumn (80.36%).

3.2. Comparative Analysis of Oocyte Retrieval, Developmental Competence, and Pregnancy Outcomes Across Sheep Breeds

A comprehensive comparison of the five sheep breeds revealed significant differences in key parameters of the LOPU-IVEP pipeline (

Table 4). East Friesian demonstrated superior oocyte recovery, yielding the highest number of total COCs per ewe (26.15 ± 4.63) and available COCs (18.69 ± 3.04), significantly outperforming Australian White (16.29 ± 1.68 and 10.93 ± 1.38, respectively). East Friesian also yielded the most Grade A oocytes (6.54 ± 2.22).

Black-headed Suffolk most distinct advantage was in developmental competence. It achieved a significantly higher cleavage rate (68.18 ± 10.78%) compared to Black-headed Dorper (43.81 ± 23.83%) and East Friesian (46.32 ± 10.92%), and achieved the highest development rate (37.02 ± 10.39%). Furthermore, oocytes from East Friesian developed into blastocysts at the highest rate (59.38 ± 17.44%), although this was not statistically different from other breeds.

Regarding pregnancy success, East Friesian and Australian White emerged as the most reliable recipients. East Friesian achieved the highest pregnancy rates for both single (73.31 ± 5.82%) and double embryo transfer (75.10 ± 13.14%). Australian White also showed high single-embryo pregnancy rates (70.22 ± 19.40%).

In summary, East Friesian was the most efficient oocyte donor, Black-headed Suffolk oocytes exhibited the highest inherent developmental potential, and East Friesian and Australian White embryos resulted in the most successful pregnancies.

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Oocyte Retrieval, Developmental Competence, and Pregnancy Outcomes Across Seasons

The analysis of seasonal effects revealed that while COCs quantity remained largely consistent throughout the year, oocyte developmental competence and pregnancy success exhibited significant seasonal variation (

Table 5).

Oocyte retrieval efficiency was generally stable across seasons, with no significant differences in the yield of total COCs, available COCs, or Grade A and B COCs. The only exception was the number of Grade C COCs, which was significantly lower in summer (5.70 ± 1.13) compared to spring and winter.

In contrast, a clear pattern emerged for embryonic development. Autumn proved to be the most favorable season, yielding the highest cleavage rate (64.05 ± 16.25%), blastocyst rate (59.02 ± 4.83%), and development rate (37.39 ± 8.67%), with values significantly higher than those in summer. Winter followed as the second most conducive season for embryo production.

This superior developmental competence in the cooler seasons translated directly into higher pregnancy rates. Both autumn and winter achieved the highest success rates for single embryo transfer (73.04 ± 9.70% and 75.31 ± 7.26%, respectively) and double embryo transfer (77.09 ± 12.36% and 74.04 ± 15.37%, respectively). Conversely, summer consistently resulted in the lowest developmental and pregnancy outcomes.

In summary, autumn and winter were identified as the optimal seasons for IVEP, characterized by high oocyte developmental competence and superior pregnancy rates, whereas summer was the least favorable period.

The seasonal pattern of IVEP efficiency observed in this study is strongly correlated with the local climate of Ulanqab, China (

Figure 4,

S1). The superior embryo production and pregnancy outcomes in autumn and winter can be attributed to a combination of moderate temperatures, low humidity, and decreasing photoperiod, which together establish an optimal physiological state for oocyte maturation and embryonic development. In contrast, the heat and humidity of summer consistently suppressed reproductive performance, likely due to heat stress impairing cellular and metabolic processes. Therefore, these findings underscore the necessity of integrating regional climatic data into the planning of annual breeding and embryo transfer schedules to enhance the efficiency of commercial sheep embryo production.

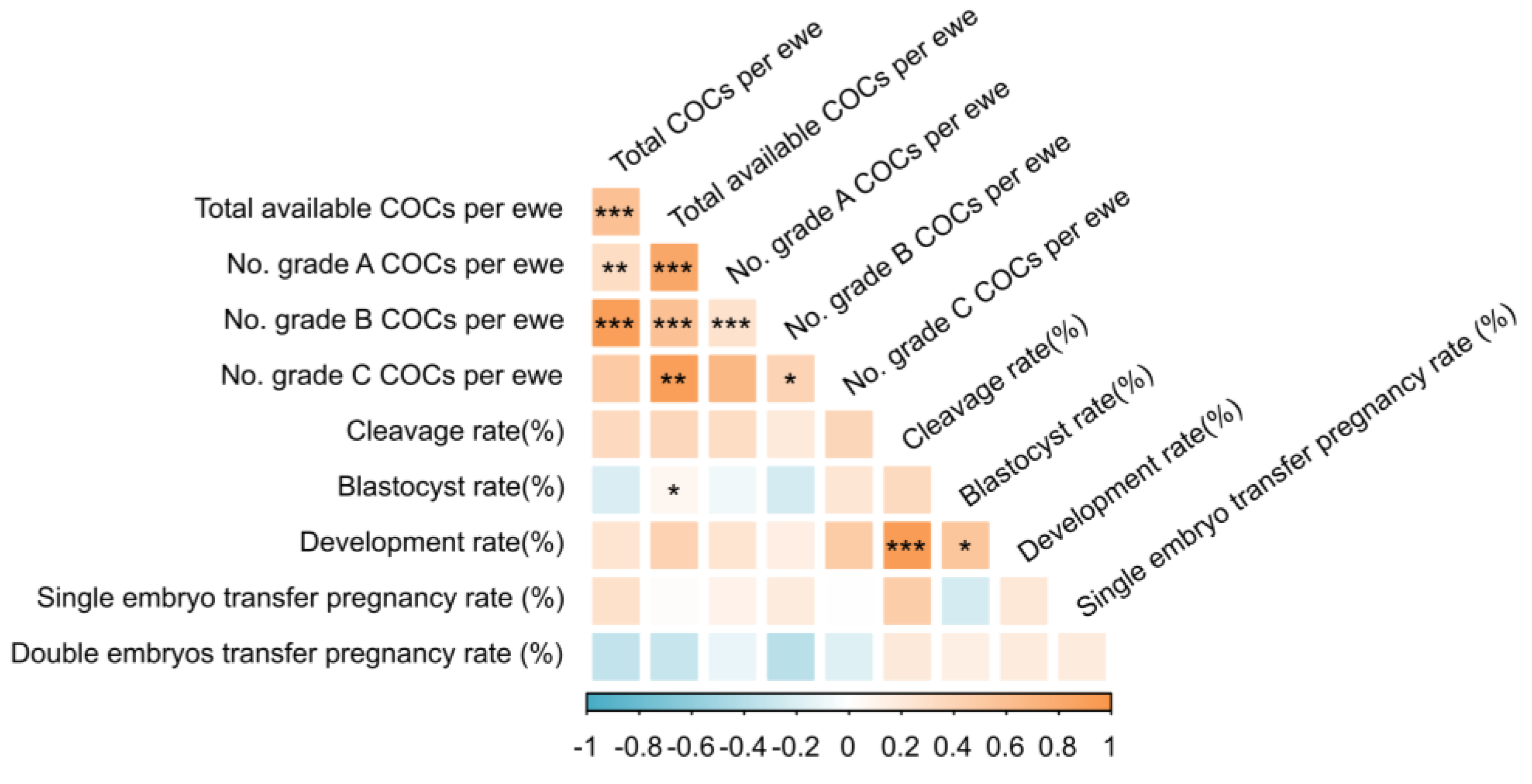

3.4. Correlation Analysis of Traits Related to LOPU-IVEP Production Efficiency

Spearman correlation analysis revealed complex relationships among the key traits in the LOPU-IVEP (

Figure 5,

Table S4). Strong positive correlations were observed within the oocyte recovery and quality parameters. The number of total COCs per ewe was highly correlated with the number of available COCs (r = 0.746,

p < 0.001), grade B COCs (r = 0.863,

p < 0.001), and grade A COCs (r = 0.576,

p = 0.008). Furthermore, the number of available COCs showed a very strong positive correlation with the number of grade A COCs (r = 0.896,

p < 0.001).

For developmental competence, a remarkably strong positive correlation was found between the cleavage rate and the subsequent development rate (r = 0.881, p < 0.001). The blastocyst rate was also positively correlated with the development rate (r = 0.568, p = 0.011) and moderately with the number of available COCs (r = 0.512, p = 0.025).

Crucially, no significant correlations were detected between the initial COCs quantity parameters and the key functional quality outcomes. This indicates that the number of oocytes recovered is a poor predictor of their subsequent developmental potential and ultimate success in establishing a pregnancy.

4. Discussion

1. The Detrimental Impact of Summer Heat and Humidity

The significantly lower oocyte developmental competence and pregnancy rates observed in summer are strongly correlated with the most challenging climatic conditions in Ulanqab, where July is the hottest (average high: 25.4°C) and most humid (52%) month. This combination of high temperature and humidity induces significant heat stress in sheep, a well-established limiting factor for reproduction [

33],. The physiological burden is twofold: firstly, as metabolic heat production increases, ewes struggle to regulate their core body temperature. Secondly, at the cellular level, heat stress disrupts ovarian function and oocyte maturation by causing abnormal protein folding and the accumulation of damaged cellular components [

33],. These insults collectively impair critical organelles such as oocyte mitochondria, which are essential for energy production during embryonic cleavage [

34]. This mechanistic cascade directly explains the poor cleavage and blastocyst rates observed in most breeds during summer, a finding consistent with the seasonal reproductive characteristics of sheep. Furthermore, the high rainfall and cloud cover likely contribute to environmental stressors and may indirectly affect animal comfort and feed intake.

2. The Optimal Conditions of Autumn and Winter

In contrast to summer, autumn provides a markedly improved environment for reproduction, characterized by moderate temperatures (with average highs of 18.8°C in September and 12.1°C in October) and the lowest humidity levels of the year, ranging from 32% to 52%. It is critical to note that the experimental flocks were housed in modern, standardized sheep housing with proper management. This management system likely played a crucial role in buffering the animals from the extremes of both summer heat and winter cold, thereby allowing the inherent genetic and seasonal potentials to be more accurately expressed. Within this controlled environment, the autumn's natural climatic conditions facilitate an optimal metabolic and hormonal balance for oocyte development, which is directly evidenced by our data showing the highest cleavage and blastocyst rates.

While winter brings cold conditions, the modern housing effectively mitigated severe cold stress. Furthermore, research suggests that controlled cold exposure may not be entirely detrimental and could even confer benefits [

17,

35]. Mild cold stress has been shown to stimulate the rapid synthesis of Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) in ewes [

36,

37]. These HSPs function as molecular chaperones that help maintain normal protein folding and cellular metabolism within oocytes, thereby enhancing their survival rate and overall stress tolerance. Therefore, the high developmental competence and pregnancy rates observed in winter likely result from a combination of effective environmental buffering by the housing system and the induction of beneficial cellular adaptive mechanisms in the absence of heat stress.

The transition into autumn and winter is marked by decreasing daylight hours, a powerful environmental cue that entrains the natural breeding season in sheep. This photoperiodic signal is primarily mediated by increased melatonin secretion, which in turn regulates the melatonin-follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) axis [

38,

39]. The elevated melatonin levels during longer nights are known to promote the activity of follicular granulosa cells and enhance the implantation potential of embryos [

40]. Furthermore, the moderate lighting conditions of autumn have been shown to extend the duration of the follicle wave [

38]. This neuroendocrine synergy ultimately creates a state of heightened reproductive receptivity. In our system, this physiological state manifests as the observed superior oocyte developmental competence and the highest pregnancy rates following embryo transfers in these seasons.

3. The Predominant Influence of Genetic Background

Beyond seasonal influences, our results unequivocally identify breed (genetic background) as the most dominant factor governing oocyte quantity and initial quality (Grade A COCs). The profound and consistent differences among breeds, such as East Friesian yielding the highest number of total and available COCs while Australian White yielded the lowest, highlight strong genetic determinism for follicular recruitment and oocyte recovery efficiency. This suggests that the choice of donor breed is the primary decision for maximizing raw oocyte yield in a commercial LOPU-IVEP system.

However, a critical divergence was observed between oocyte quantity and developmental competence. Specifically, Black-headed Suffolk oocytes, despite a numerically lower recovery rate than East Friesian, exhibited significantly superior developmental competence, as evidenced by the highest cleavage and development rates. This underscores a fundamental concept: a high oocyte yield does not automatically equate to high embryo production efficiency. The genetic factors controlling the number of ovulatory follicles appear to be distinct from those governing cytoplasmic maturation and epigenetic programming, which are crucial for successful embryonic development.

4. Breed-by-Season Interaction: Unlocking Customized Management Strategies

The significant interaction between breed and season for key developmental parameters (cleavage and development rate) is perhaps the most operationally relevant finding. It demonstrates that the response of a breed to seasonal environmental cues is not uniform. This interaction explains why a single seasonal management policy is suboptimal. The cluster analysis (

Figure 3) provides a clear visual representation of this interaction, identifying Black-headed Suffolk in autumn and winter as a superior combination for embryo production. This breed appears to possess a genetic makeup that is particularly responsive to the improving (autumn) or stable (winter) photoperiod and the release from summer heat stress, effectively channeling these favorable conditions into enhanced ooplasmic quality and developmental competence. Conversely, the poor performance of Australian White in summer and Black-headed Dorper in winter highlights breed-specific vulnerabilities. Australian White may be exceptionally susceptible to heat stress, while Black-headed Dorper might be more sensitive to cold stress or the metabolic demands of thermoregulation, thereby diverting energy away from reproductive processes.

5. Synthesis and Practical Implications: A Two-Tiered Selection System

Based on our integrative analysis of the breed and season effects, we propose a precision strategy for commercial sheep embryo production to maximize annual efficiency and economic return.

Align the LOPU and ET schedule for each breed with its identified optimal season. The production cycle for Black-headed Suffolk, the breed with the highest oocyte developmental competence, should be concentrated in autumn and winter to capitalize on this synergistic advantage. Reduce LOPU frequency for Black-headed Suffolk and Black-headed Dorper during summer to avoid the collection of low-competence oocytes. Concurrently, implement enhanced feeding management and cooling strategies to alleviate heat stress during this period. East Friesian, as the highest oocyte yielder, should be utilized as a donor primarily during its most favorable seasons to maximize raw material output for embryo production.

In conclusion, we recommend that autumn be prioritized as the prime window for oocyte collection and embryo transfer. We further advise that the majority of the annual embryo production quota be concentrated in the autumn and winter seasons. By adopting this breed-season integrated management approach, commercial operations can strategically leverage genetic strengths and environmental synergies to achieve superior productivity.

5. Conclusions

The efficiency of large-scale commercial in vitro sheep embryo production is determined not in isolation but by the significant interaction between genetic background (breed) and environmental conditions (season). Autumn and Winter constitute the optimal window for embryo production, characterized by climatic conditions that promote superior oocyte developmental competence, leading to the highest pregnancy rates. The absence of correlation between oocyte quantity and functional quality (development and pregnancy) underscores the necessity for a dual selection criterion in breeding programs, prioritizing both high yield and high developmental potential. In summary, this study provides a robust scientific basis for implementing a precision, breed-season integrated management strategy. By scheduling LOPU operations to leverage the synergistic effects of specific breed-season combinations, commercial sheep embryo production can achieve significant gains in both productivity and economic returns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.W. (Yubing Wang), K.L. and G.X.; methodology, Y.W. (Yubing Wang) and G.X.; software, Y.W. (Yubing Wang); validation, Y.W. (Yubing Wang), K.L., J.H.,R.W. and H.H.; formal analysis, Y.W. (Yubing Wang) and K.L.; investigation, Y.W. (Yubing Wang), K.L.,J.H., D.C., L.C. and Y.W. (Yingjie Wu); resources, G.X. and J.T.; data curation, Y.W. (Yubing Wang) and K.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.W. (Yubing Wang) and K.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.W. (Yubing Wang) and G.X.; visualization, Y.W. (Yubing Wang); supervision, J.T.; project administration, G.X. and J.T.; funding acquisition, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key R&D Program (2023YFD1300504), Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Science and Technology Innovation Major Demonstration Project (No. 2025ZDSF0018), Central-led Local Science and Technology Development Funds (No. 2024ZY0160).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Committee of China Agricultural University (AW30405202-1-03).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the first author, Yubing Wang (wangyubing911@163.com), upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Inner Mongolia Sino Sheep Breeding Company for their technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Viana, J.H. 2023 Statistics of Embryo Production and Transfer in Domestic Farm Animals.

- Zhu, J.; Moawad, A.R.; Wang, C.-Y.; Li, H.-F.; Ren, J.-Y.; Dai, Y.-F. Advances in in Vitro Production of Sheep Embryos. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine 2018, 6, S15–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonergan, P.; Khatir, H.; Carolan, C.; Mermillod, P. Bovine Blastocyst Production in Vitro after Inhibition of Oocyte Meiotic Resumption for 24 h. J Reprod Fertil 1997, 109, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar1, A.A.; Ahmed2, M.N.; Asker3, A.S.; Majeed1, A.F.; Faraj4, T.M.; Rejah4, S.J. In Vitro Production of Ovine Embryo in Non-Breeding Season. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology 2021, 15, 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondin, P.; Sirard, M.-A. Oocyte and Follicular Morphology as Determining Characteristics for Developmental Competence in Bovine Oocytes. Molecular Reproduction and Development 1995, 41, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlok, A.; Lucas-Hahn, A.; Niemann, H. Fertilization and Developmental Competence of Bovine Oocytes Derived from Different Categories of Antral Follicles. Molecular Reproduction and Development 1992, 31, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, N.A. In Vitro Maturation and in Vitro Fertilization of Sheep Oocytes. Small Ruminant Research 2002, 44, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.C.; Barbas, J.P.; Baptista, M.C.; Cannas Serra, C.; Vasques, M.I.; Pereira, R.M.; Cavaco-Gonçalves, S.; Horta, A.E.M. Reproduction in the Ovine Saloia Breed: Seasonal and Individual Factors Affecting Fresh and Frozen Semen Performance, in Vivo and in Vitro Fertility. In Animal products from the Mediterranean area; Ramalho Ribeiro, J.M.C., Horta, A.E.M., Mosconi, C., Rosati, A., Eds.; Brill | Wageningen Academic, 2006; pp. 331–336 ISBN 978-90-8686-568-0.

- Bergstein-Galan, T.G.; Weiss, R.R.; Kozicki, L.E. Effect of Semen and Donor Factors on Multiple Ovulation and Embryo Transfer (MOET) in Sheep. Reprod Domest Anim 2019, 54, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, P.P.M.; Padilha, L.C.; Oliveira, M.E.F.; Motheo, T.F.; da Silva, A.S.L.; Barros, F.F.P.C.; Coutinho, L.N.; Flôres, F.N.; Lopes, M.C.S.; Bandarra, M.B.; et al. Laparoscopic Ovum Collection in Sheep: Gross and Microscopic Evaluation of the Ovary and Influence on Ooctye Production. Animal Reproduction Science 2011, 127, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, J.; Koseniuk, J.; Skrzyszowska, M.; Cegła, M. L-OPU in Goat and Sheep—Different Variants of the Oocyte Recovery Method. Animals 2020, 10, 658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadashpour Davachi, N.; Zare Shahneh, A.; Kohram, H.; Zhandi, M.; Dashti, S.; Shamsi, H.; Moghadam, R. In Vitro Ovine Embryo Production: The Study of Seasonal and Oocyte Recovery Method Effects. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2014, 16, e20749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, W.; Gabr, Sh.; Zaghloul, H.; Salem, M.; El-fakhry, S. Effect of Reproductive Status on Yield and in Vitro Maturation of Oocytes of Egyptian Sheep. Journal of Animal and Poultry Production 2018, 9, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mara, L.; Sanna, D.; Casu, S.; Dattena, M.; Muñoz, I.M.M. Blastocyst Rate of in Vitro Embryo Production in Sheep Is Affected by Season. Zygote 2014, 22, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munther, A.; Mohammed, T.; Majeed, A. Effect of Some Months on Follicles and Oocytes Recovered from Iraqi Ewes. AJVS 2021, 14, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, C.; Cao, G.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X. Effects of Recipient Oocyte Source, Number of Transferred Embryos and Season on Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer Efficiency in Sheep. Reprod Domestic Animals 2019, 54, 1443–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, E.; Nazari, H.; Hossini-Fahraji, H. Low Developmental Competence and High Tolerance to Thermal Stress of Ovine Oocytes in the Warm Compared with the Cold Season. Trop Anim Health Prod 2019, 51, 1611–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirshenbaum, M.; Ben-David, A.; Zilberberg, E.; Elkan-Miller, T.; Haas, J.; Orvieto, R. Influence of Seasonal Variation on in Vitro Fertilization Success.

- Majeed, A.F.; AL-Timimi, I.H.; AL-Saigh, M.N. Effect of Season on Embryo Production in Black Local Iraqi Goats.

- Souza-Fabjan, J.M.G.; Correia, L.F.L.; Batista, R.I.T.P.; Locatelli, Y.; Freitas, V.J.F.; Mermillod, P. Reproductive Seasonality Affects In Vitro Embryo Production Outcomes in Adult Goats. Animals 2021, 11, 873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catala, M.-G.; Roura, M.; Soto-Heras, S.; Menéndez, I.; Contreras-Solis, I.; Paramio, M.-T.; Izquierdo, D. Effect of Season on Intrafollicular Fatty Acid Concentrations and Embryo Production after in Vitro Fertilization and Parthenogenic Activation of Prepubertal Goat Oocytes. Small Ruminant Research 2018, 168, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.-Y.; Yang, C.-Y.; Yu, N.-Q.; Huang, J.-X.; Zheng, W.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Shang, J.-H. Effect of Season on the In-Vitro Maturation and Developmental Competence of Buffalo Oocytes after Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2020, 27, 7729–7735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, S.; Boccia, L.; Campanile, G.; Di Palo, R.; Vecchio, D.; Neglia, G.; Zicarelli, L.; Gasparrini, B. The Effect of Season on Oocyte Quality and Developmental Competence in Italian Mediterranean Buffaloes (Bubalus Bubalis). Animal Reproduction Science 2011, 123, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjunatha, B.M.; Ravindra, J.P.; Gupta, P.S.P.; Devaraj, M.; Nandi, S. Effect of Breeding Season on in Vivo Oocyte Recovery and Embryo Production in Non-Descriptive Indian River Buffaloes (Bubalus Bubalis). Animal Reproduction Science 2009, 111, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodarczyk, R.; Bukowska, D.; Jackowska, M.; Mucha, S.; Jaskowski, J.M. In Vitro Maturation and Degeneration of Domestic Cat Oocytes Collected from Ovaries Stored at Various Temperatures. Vet. Med. 2009, 54, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spindler, R.E.; Wildt, D.E. Circannual Variations in Intraovarian Oocyte but Not Epididymal Sperm Quality in the Domestic Cat1. Biology of Reproduction 1999, 61, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, K.G.M.; El-Naby, A.-S.A.-H.H. Factors Affecting Buffalo Oocytes Maturation. 2013.

- Khairy, M.; Zoheir, A.; Abdon, A.S.; Mahrous, K.F.; Amer, M.A.; Zaher, M.M.; Li-Guo, Y.; El-Nahass, E.M. Effects of Season on the Quality and in Vitro Maturation Rate of Egyptian Buffalo (Bubalus Bubalis) Oocytes. JCAB 2007, 1, 029–033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, T.H.; Yellon, S.M. Aging, Reproduction, and the Melatonin Rhythm in the Siberian Hamster. J Biol Rhythms 2001, 16, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirotkin, A.V.; Schaeffer, H.-J. Direct Regulation of Mammalian Reproductive Organs by Serotonin and Melatonin. Journal of Endocrinology 1997, 154, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Ji, P.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lv, D.; Abulizi, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Beneficial Effects of Melatonin on the in Vitro Maturation of Sheep Oocytes and Its Relation to Melatonin Receptors. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2017, 18, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodarzi, A.; Zare Shahneh, A.; Kohram, H.; Sadeghi, M.; Moazenizadeh, M.H.; Fouladi-Nashta, A.; Dadashpour Davachi, N. Effect of Melatonin Supplementation in the Long-Term Preservation of the Sheep Ovaries at Different Temperatures and Subsequent in Vitro Embryo Production. Theriogenology 2018, 106, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Wettere, W.H.E.J.; Kind, K.L.; Gatford, K.L.; Swinbourne, A.M.; Leu, S.T.; Hayman, P.T.; Kelly, J.M.; Weaver, A.C.; Kleemann, D.O.; Walker, S.K. Review of the Impact of Heat Stress on Reproductive Performance of Sheep. Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 2021, 12, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Response to Heat Stress for Small Ruminants: Physiological and Genetic Aspects. Livestock Science 2022, 263, 105028. [CrossRef]

- Al-Katanani, Y.M.; Paula-Lopes, F.F.; Hansen, P.J. Effect of Season and Exposure to Heat Stress on Oocyte Competence in Holstein Cows. Journal of Dairy Science 2002, 85, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tüfekci, H.; Sejian, V. Stress Factors and Their Effects on Productivity in Sheep. Animals 2023, 13, 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuer, A.; Spandorfer, S.D.; Giraldo, P.; Dieterle, S.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Witkin, S.S. The Role of Heat Shock Proteins in Reproduction. Human Reproduction Update 2000, 6, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastromonaco, G.F.; Gonzalez-Grajales, A.L. Reproduction in Female Wild Cattle: Influence of Seasonality on ARTs. Theriogenology 2020, 150, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgadillo, J.A.; Hernández, H.; Abecia, J.A.; Keller, M.; Chemineau, P. Is It Time to Reconsider the Relative Weight of Sociosexual Relationships Compared with Photoperiod in the Control of Reproduction of Small Ruminant Females? Domestic Animal Endocrinology 2020, 73, 106468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yie, S.-M.; Brown, G.M.; Liu, G.-Y.; Collins, J.A.; Daya, S.; Hughes, E.G.; Foster, W.G.; Younglai, E.V. Melatonin and Steroids in Human Pre-Ovulatory Follicular Fluid: Seasonal Variations and Granulosa Cell Steroid Production. Human Reproduction 1995, 10, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).