1. Introduction

In vitro maturation (IVM) of oocytes represents a central technology in both animal in vitro embryo production (IVEP) systems and contemporary human assisted reproductive technologies (ART) [

1,

2,

3]. Continued improvements in IVM efficiency hold the potential to further optimize ART, offering significant advancements for the treatment of human infertility and the enhancement of livestock breeding. However, compared with oocytes matured in vivo (IVO), the efficiency of IVM remains suboptimal, as oocytes matured in vitro often exhibit reduced developmental competence [

4,

5]. A major limitation lies in the inability of current culture systems to fully recapitulate the ovarian microenvironment, leading to excessive oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and elevated inflammatory responses [

2,

6]. These adverse conditions ultimately compromise both nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of oocytes, resulting in decreased fertilization rates and blastocyst formation [

4,

7]. Consequently, pinpointing paracrine or autocrine factors that reshape the oocyte IVM microenvironment to reduce oxidative stress, suppress apoptosis, and fortify cumulus-oocyte crosstalk is indispensable for unlocking high-quality oocyte production and the future of ART.

Oocyte-derived factors (ODFs) are the principal architects of mammalian folliculogenesis and oocyte competence. Increasing evidence indicates that oocytes are not merely passive recipients of cumulus cell support but actively regulate cumulus cell function and their own developmental competence through the secretion of specific growth factors, thereby maintaining oocyte quality and the homeostasis of the follicular microenvironment [

8]. Canonical ODFs include growth differentiation factor 9 (GDF9) and bone morphogenetic protein 15 (BMP15), two TGF-β superfamily ligands, which promote granulosa cell proliferation and differentiation, induce cumulus cell expansion, and enhance oocyte developmental competence by facilitating bidirectional cumulus-oocyte signaling [

9,

10]. This core network is fine-tuned by ancillary ODFs such as fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8), KIT ligand (KITL), and R-spondin-2 (RSPO2), which calibrate granulosa metabolism, sustain oocyte survival, and safeguard mitochondrial function [

11,

12]. Together, these oocyte-borne signals converge with granulosa-derived factors to sculpt a microenvironment that licenses high-quality maturation and primes the oocytes for robust embryonic development, offering actionable targets for the rational design of IVM and embryo culture systems.

In recent years, intercellular communication has gained increasing attention for its role in regulating follicular microenvironment stability and oocyte developmental competence [

13]. The Ephrin (EFN) family, comprising glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored or transmembrane ligands, mediates cell adhesion, migration, and tissue morphogenesis through interactions with Eph receptor tyrosine kinases [

14]. While extensive research has established their functions in neural development [

15], angiogenesis, and tumorigenesis, emerging evidence suggests that ephrins may also participate in reproductive processes. Within the ovary, research on gene knockout mouse models shows that ephrin/Eph signals was implicated in folliculogenesis and the ovulatory cascade [

16,

17], yet its specific functions during oocyte maturation remain largely unexplored [

16]. Additionally, analyses of published transcriptomic datasets detect EFNA5 expression in germ cells across multiple species, collectively suggesting that EFNA5 may play some relatively conservative roles in reproduction. [

18,

19,

20].

In this study, to dissect the regulatory role and underlying mechanism of EFNA5 in oocyte maturation, we exploited an ovine IVM model that is both agriculturally relevant and translationally informative for human reproductive medicine. We first mapped the spatiotemporal expression of EFNA5 and its cognate receptor EPHA4 in ovine ovaries, then systematically evaluated the impact of exogenous recombinant EFNA5 on oocyte meiotic progression, blastocyst yield, and the attendant molecular circuitry. Our results showed that EFNA5, secreted by the oocyte itself, elevates nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation and augments subsequent embryonic potential by simultaneously reducing oxidative stress, curbing inflammatory signaling, and reinforcing bidirectional cumulus-oocyte communication. This study delivers the first functional evidence that EFNA5 operates as a bona fide oocyte-derived factor and provides a mechanistic framework for enhancing oocyte IVM efficiency while offering translational insights for human ART.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals and reagents, unless otherwise specified, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) cross-adsorbed secondary antibody and DAPI solution were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). HRP-conjugated Affinipure goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) was purchased from Proteintech (Beijing, China).

2.2. Oocyte Collection and In Vitro Maturation

Sheep ovaries were collected from a local slaughterhouse (Ulanqab, Inner Mongolia, China) and transported to the laboratory within 2 h in 0.9% saline maintained at 36 °C and supplemented with 100 IU/mL penicillin. Upon arrival, ovaries were rinsed thoroughly with pre-warmed saline, and follicular fluid from 3–8 mm follicles was aspirated using an 18-gauge needle. Cumulus–oocyte complexes (COCs) surrounded by at least three layers of compact cumulus cells were selected under a stereomicroscope. In some experiments, germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes were obtained by treating COCs with 0.3% hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) followed by gentle pipetting to remove surrounding cumulus cells. For in vitro maturation (IVM), COCs or GV oocytes were cultured in TCM-199 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10 µg/mL FSH, 10 µg/mL LH, 1 µg/mL 17β-estradiol, 100 µg/mL L-glutamine, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and 1% (v/v) penicillin–streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cultures were maintained at 38.5 °C under 5% CO2 in humidified air for 24 h. The efficiency of IVM was assessed by polar body extrusion (PBE).

Recombinant human ephrin-A5 (EFNA5; ProSpec, Cat. PRO-2327) was reconstituted in 0.1% BSA in PBS according to the manufacturer’s instructions, sterile-filtered (0.22 µm), aliquoted, and stored at −80 °C to avoid repeated freeze–thaw cycles. For supplementation experiments, the IVM medium was supplemented with EFNA5 at final concentrations of 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL. Vehicle controls received equal volumes of the reconstitution buffer (0.1% BSA/PBS) diluted in IVM medium.

2.3. In Vitro Fertilization and Embryo Culture

Following IVM, COCs were denuded by three washes in synthetic oviductal fluid (SOF) containing 0.2% (w/v) hyaluronidase and then transferred to the IVF medium (SOF supplemented with 2% oestrous sheep serum, 3 mg/mL BSA, 6 IU/mL heparin sodium and 50 IU/mL gentamicin). Frozen semen straws were thawed in a 39 °C water bath for 1 min. After dilution in pre-equilibrated IVF medium, spermatozoa were selected by a 30 min swim-up at 38.5 °C under 5% CO2 in humidified air. The upper motile fraction was collected, centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min, and the pellet resuspended in IVF medium to give a final concentration of 1 × 106 spermatozoa/mL. Oocytes were co-incubated with spermatozoa for 20 h at 38.5 °C, 5% CO2, maximum humidity. Presumptive zygotes were washed three times in IVC medium and cultured in groups of 25-30 in 50 µL droplets of SOF supplemented with 1% (v/v) BME-essential amino acids, 1% (v/v) MEM-nonessential amino acids, 1 mM l-glutamine and 3 mg/mL BSA under 38.5 °C, 88% N2, 6% CO2 and 6% O2. Cleavage and blastocyst rates were recorded at 48 h and on day 6 post-IVF, respectively.

2.4. Evaluation of COCs Expansion

After 24 h of IVM, cumulus expansion was evaluated according to the criteria adapted from Vanderhyden et al. [

21]. and scored on a scale of 1–3: 1, partial expansion restricted to the outermost cumulus cell layers; 2, expansion of all cumulus cell layers except the corona radiata; 3, complete expansion of all cumulus cells, including the corona radiata.

2.5. Detection of Apoptosis

Apoptosis was assessed using a one-step TUNEL apoptosis assay kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, COCs and blastocysts were washed in PBS, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 1 h at room temperature, and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 5 min. Samples were then incubated with freshly prepared TUNEL reaction mixture for 1 h at room temperature in the dark, followed by nuclear counterstaining with DAPI. The number of apoptotic cells was quantified by counting TUNEL-positive nuclei, and the total cell number was determined based on DAPI staining.

2.6. Measurement of Intracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Glutathione (GSH) Levels

Intracellular ROS and GSH levels were evaluated using DCFH-DA (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and CMF2HC (MCE, USA), respectively. Briefly, cumulus cells were removed by treatment with IVM medium containing 0.1% (w/v) hyaluronidase, and denuded oocytes were washed thoroughly in PBS. Oocytes were then incubated with the respective fluorescent probes at 37 °C for 20 min in the dark. After washing, fluorescence signals were captured using a fluorescence microscope, and the relative fluorescence intensity of each oocyte was quantified with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.7. Lipid Peroxidation

Lipid peroxidation in oocytes was assessed using the ratiometric probe C11-BODIPY 581/591 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Briefly, cumulus cells were removed by treatment with IVM medium containing 0.1% (w/v) hyaluronidase, and denuded oocytes were washed thoroughly in PBS containing 0.1% (w/v) polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). Oocytes were incubated live with 2 µM C11-BODIPY in IVM medium at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, followed by three washes in PBS-PVA. Fluorescence was captured immediately on a fluorescence microscope using appropriate filter sets: reduced (non-oxidized) C11-BODIPY was recorded in the red channel and oxidized C11-BODIPY in the green channel. For each oocyte, background-subtracted mean fluorescence intensities were quantified in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), and lipid peroxidation was expressed as the oxidized/reduced ratio (green/red), as specified in figure legends. Results are presented as mean ± SEM on a per-oocyte basis.

2.8. γ H2AX Staining

DNA damage in oocytes was assessed by γH2AX immunofluorescence. Denuded oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C for 1 h, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at room temperature, and blocked in PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA for 1 h. Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C with an anti-γH2AX primary antibody (1:200; Beyotime, Shanghai, China), followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (1:500; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 µg/mL; Invitrogen, USA), and fluorescence signals were observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope. For each oocyte, γH2AX intensity was quantified in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA), and results were expressed as mean ± SEM.

2.9. Cortical Granule Staining

Cortical granule (CG) distribution in oocytes was assessed using FITC-conjugated lectin staining. Denuded oocytes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, and blocked with PBS containing 1% (w/v) BSA for 1 h. Samples were incubated overnight at 4 °C in the dark with FITC-conjugated Lens culinaris agglutinin (LCA; 1:300; Thermo Fisher Scientific, L32475, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After three washes in PBS, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 µg/mL; Invitrogen, USA) for 5 min. Oocytes were mounted on glass slides, and CG distribution patterns were observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

2.10. Immunofluorescence Localization of EFNA5 and EPHA4

Immunofluorescence staining was performed to determine the localization of EFNA5 and its receptor EPHA4 in oocytes and cumulus cells. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at 4 °C for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min at room temperature, and blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against EFNA5 (1:100; ABMART, TP72055, Shanghai, China) and EPHA4 (1:100; Proteintech, 21875-1-AP, Wuhan, China). After three washes in PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (1 µg/mL; Invitrogen, USA) for 5 min. EFNA5 and EPHA4 localization was visualized using a laser scanning confocal microscope.

2.11. Transcriptome Sequencing Analysis

To assess EFNA5-dependent transcriptional changes, MII oocytes and cumulus cells were harvested after 24 h of IVM from control and EFNA5-treated groups for RNA-seq. Only morphologically normal oocytes (extruded first polar body and homogeneous cytoplasm) were selected, with 5-6 oocytes per sample and at least three biological replicates per group. Total RNA was extracted using a single-cell full-length mRNA amplification kit (i-SingleCell, Cat. No. N712). Libraries were prepared with a modified Smart-seq2 protocol using the TePrep™ DNA Library Prep Kit V2 (Azenta Life Sciences, USA), and library quality was assessed using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer and a Fragment Analyzer. Cross-species oocyte RNA-seq datasets from multiple species were obtained from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; accessions: GSE158539 [

22], GSE165546 [

23], GSE233232 [

24], GSE148022 [

18], GSE95477 [

25], GSE119906 [

26], GSE61717 [

27], GSE160334 [

28])

Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq™ X Plus platform with 150 bp paired-end reads. Adapters and low-quality reads were trimmed with Cutadapt v2.10 and Trim Galore v0.6.5. Clean reads were aligned to the ovine genome Oar_v3.1 (Ensembl release 106) using HISAT2 v2.2.1, and transcript abundance was quantified with RSEM v1.3.3 as TPM. Differential expression analysis was conducted using DESeq2 (|log2FC| > 1.5, adjusted P < 0.05). Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis were performed with clusterProfiler v4.0.5, and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted using GSEA v4z.

2.12. RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted using a micro-scale RNA extraction kit (Tiangen, China) and reverse-transcribed into cDNA with a reverse transcription kit (Vazyme, China). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Takara, Japan) in a 20 μL reaction containing 10 μL SYBR Premix Ex Taq II, 6 μL RNase-free water, 2 μL cDNA, and 1 μL of each primer. Cycling conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. ACTB served as the internal control, and relative expression levels were calculated using the 2-ΔCt method. The sequences of primers are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.13. Protein Extraction and Western Blot Analysis

Oocytes, cumulus cells, or COCs from control and EFNA5-treated groups were lysed in RIPA buffer with protease inhibitors (Beyotime, China). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher, USA). Equal amounts of protein (10 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:8000, Jackson, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein signals were detected using ECL substrate (Thermo Fisher, USA) and imaged on a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc system. Band intensities were quantified with ImageJ, using GAPDH as the internal control.

For clarity of presentation and consistency across figures, some Western blot images were horizontally flipped to align with the order of sample loading described in the figure legends. The original, uncropped scans of all blots with lanes clearly annotated are provided in the Supplementary Information. The orientation does not affect the data interpretation or conclusions.

2.14. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with at least three biological replicates. Statistical analyses and visualization were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8. Data normality was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test, and variance homogeneity was evaluated. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed t-test was used if normality and homogeneity of variance were met; for comparisons between multiple groups, a one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post hoc test was used if parametric assumptions were met. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance is indicated as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, and **** p < 0.0001. Different letters in figures indicate significant differences between groups (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

IVM is a critical step in mammalian ART, yet the limited maturation quality and developmental competence of oocytes remain major obstacles to its broader application [

30,

31]. ODFs play central roles in maintaining oocyte developmental potential and shaping the follicular microenvironment. Among them, the classical ODFs, GDF9 and BMP15, have been shown to regulate cumulus cell proliferation and extracellular matrix formation, thereby supporting folliculogenesis and embryo development [

31,

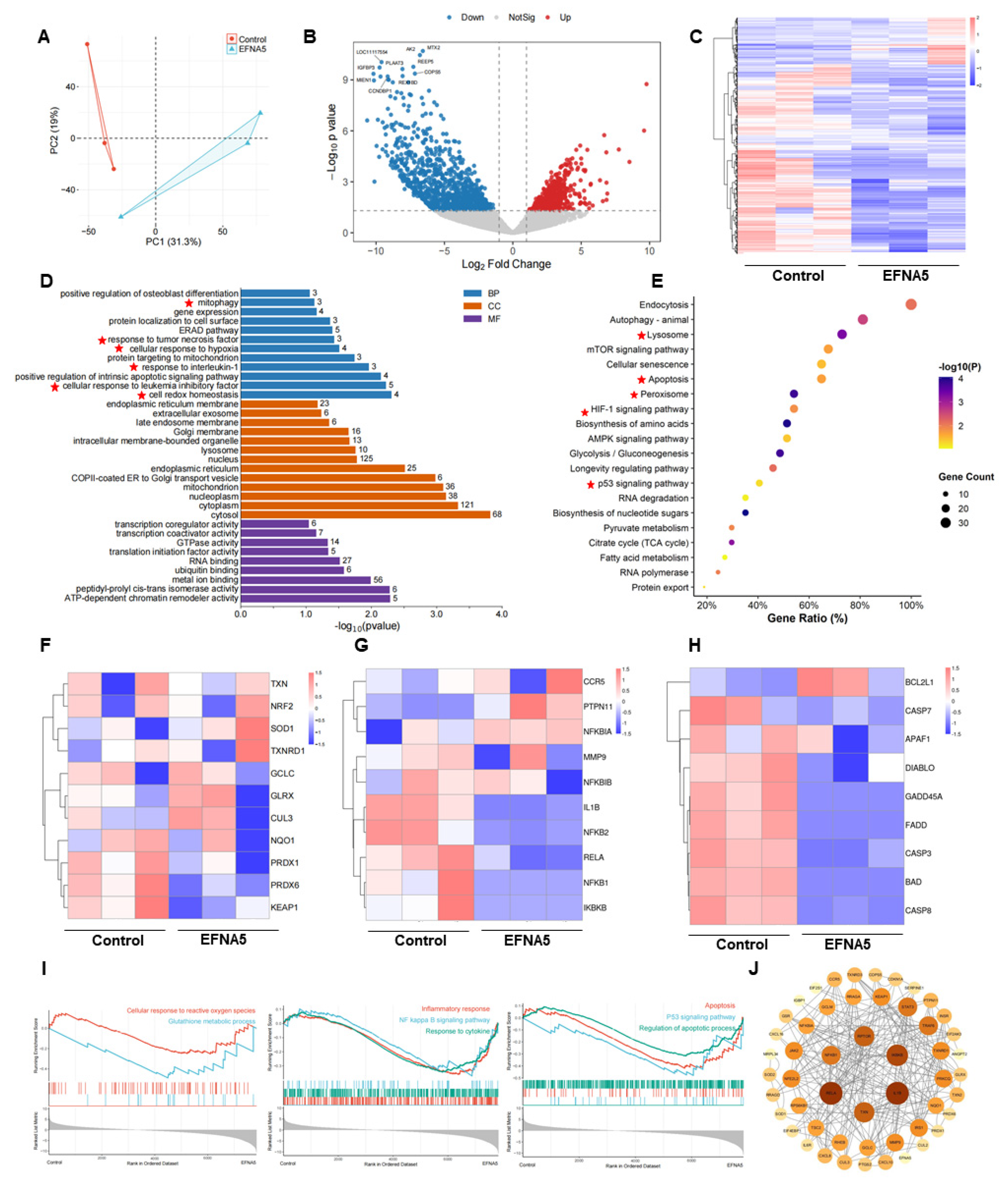

32]. However, the diversity and functional mechanisms of ODFs remain incompletely understood. In this study, we provide the first systematic evidence that EFNA5 functions as a bona fide oocyte-derived factor (ODF) that orchestrates IVM competence at both the oocyte and cumulus levels. Mechanistically, EFNA5 enhances the NRF2-mediated antioxidant defense pathway while concurrently suppressing NF-κB–driven inflammatory signaling, thereby attenuating ROS accumulation, reducing apoptosis, and stabilizing redox homeostasis. These coordinated effects ultimately improve oocyte quality and developmental competence under in vitro maturation conditions.

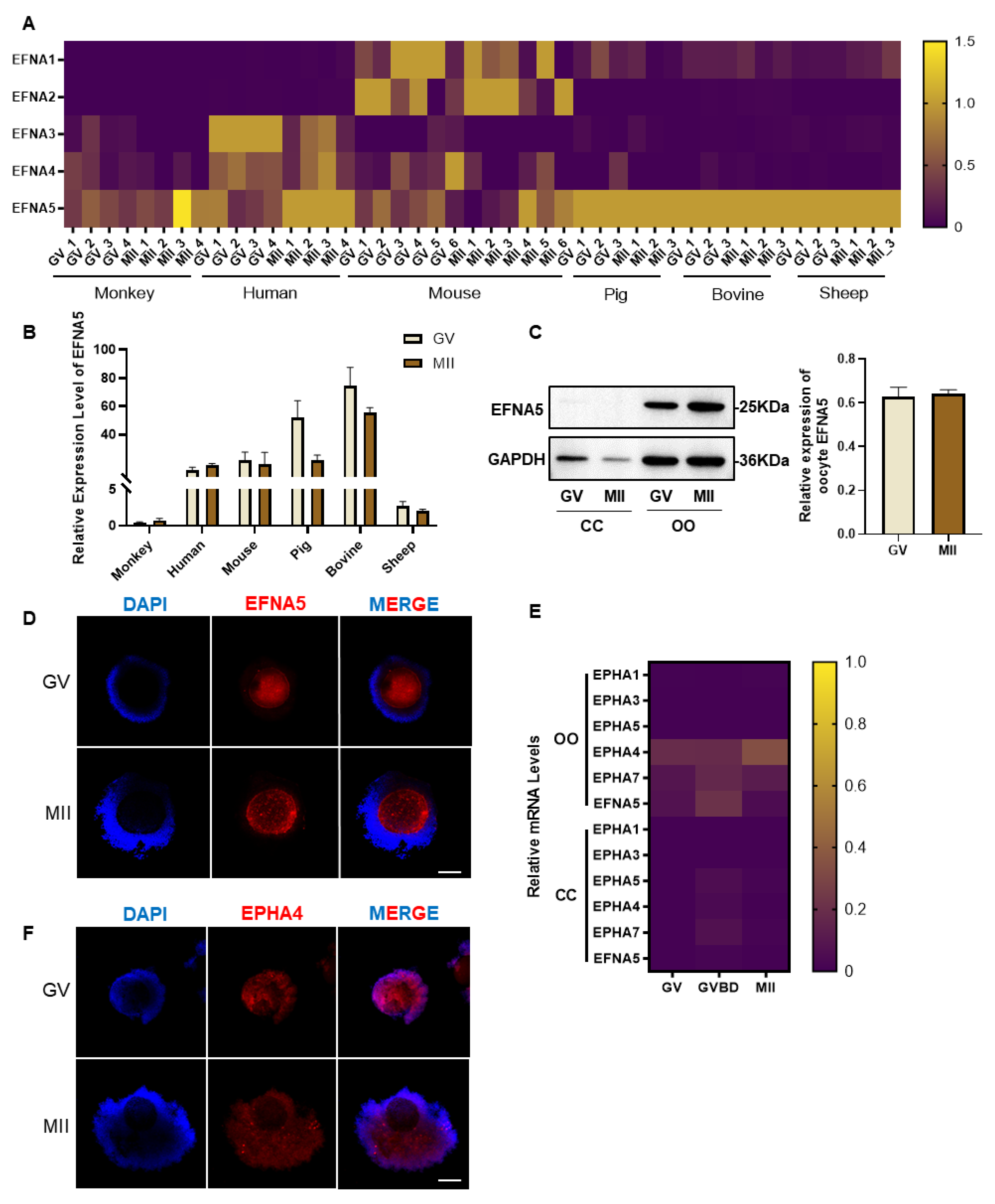

Cross-species transcriptomic analyses revealed that EFNA5 is stably expressed in oocytes, indicating its evolutionary conservation as a ODF. In the ovine model, EFNA5 was predominantly enriched in oocytes, whereas its main receptor, EPHA4, showed expression both in oocytes and granulosa cells. This spatiotemporal specificity suggests that EFNA5 may act via autocrine or paracrine signaling to orchestrate oocyte maturation, providing a theoretical basis for its functional study in vitro. Notably, both the direction and magnitude of EFNA5’s effects appear to be species dependent. In human and sheep, EFNA5 abundance is lower in IVM than in in vivo matured oocytes, whereas mice show the opposite trend. EFNA5 has been reported to promote apoptosis in murine granulosa cells [

17], yet in sheep it exerts a clearly anti-apoptotic action that protects oocytes and improves embryo quality.

A straightforward explanation is that EFNA5 engages different EphA receptors across species, and the abundance of these receptors varies between oocytes and granulosa cells. EFNA5 can bind to multiple EPA isoforms, including EPHA4, EPHA5, and EPHA7, but the relative receptor expression differs not only across species but also between cell types within the same species [

33,

34,

35]. Distinct EphA receptors recruit different adaptor protein complexes and preferentially activate specific downstream pathways. For instance, in pancreatic islet cells, EFNA5 interacts with EPHA5 to mediate intercellular communication and regulate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [

36]. In neuronal and epithelial cells, EFNA5 binding to EPHA3 or EPHA7 modulates cell adhesion and cytoskeletal organization [

37]. In our ovine dataset, EA4 was identified as the predominant receptor in granulosa cells, whereas in the mouse ovary, other EphA isoforms appear to be more enriched [

17]. In addition, species-specific differences have been widely reported for other ODFs. In mice, GDF9 and BMP15 strongly promote cumulus expansion and enhance oocyte developmental competence [

30]. Notably, GDF9 deficiency leads to complete follicular arrest, whereas BMP15 deficiency results only in reduced fertilization efficiency and subfertility [

38]. By contrast, in sheep, both GDF9 and BMP15 are indispensable; immune neutralization of either factor causes follicular blockage and anovulation in most ewes, while partial neutralization of BMP15 markedly increases ovulation rate, suggesting a dose-dependent effect [

32]. In cattle, both GDF9 and BMP15 are essential for follicular development and ovulation [

39], while in humans, mutations or deficiencies in these factors are more often associated with diminished ovarian reserve or subfertility rather than absolute infertility [

40,

41]. Collectively, these findings highlight that ODF-mediated mechanisms exhibit pronounced interspecies differences in both functional significance and regulatory strength.

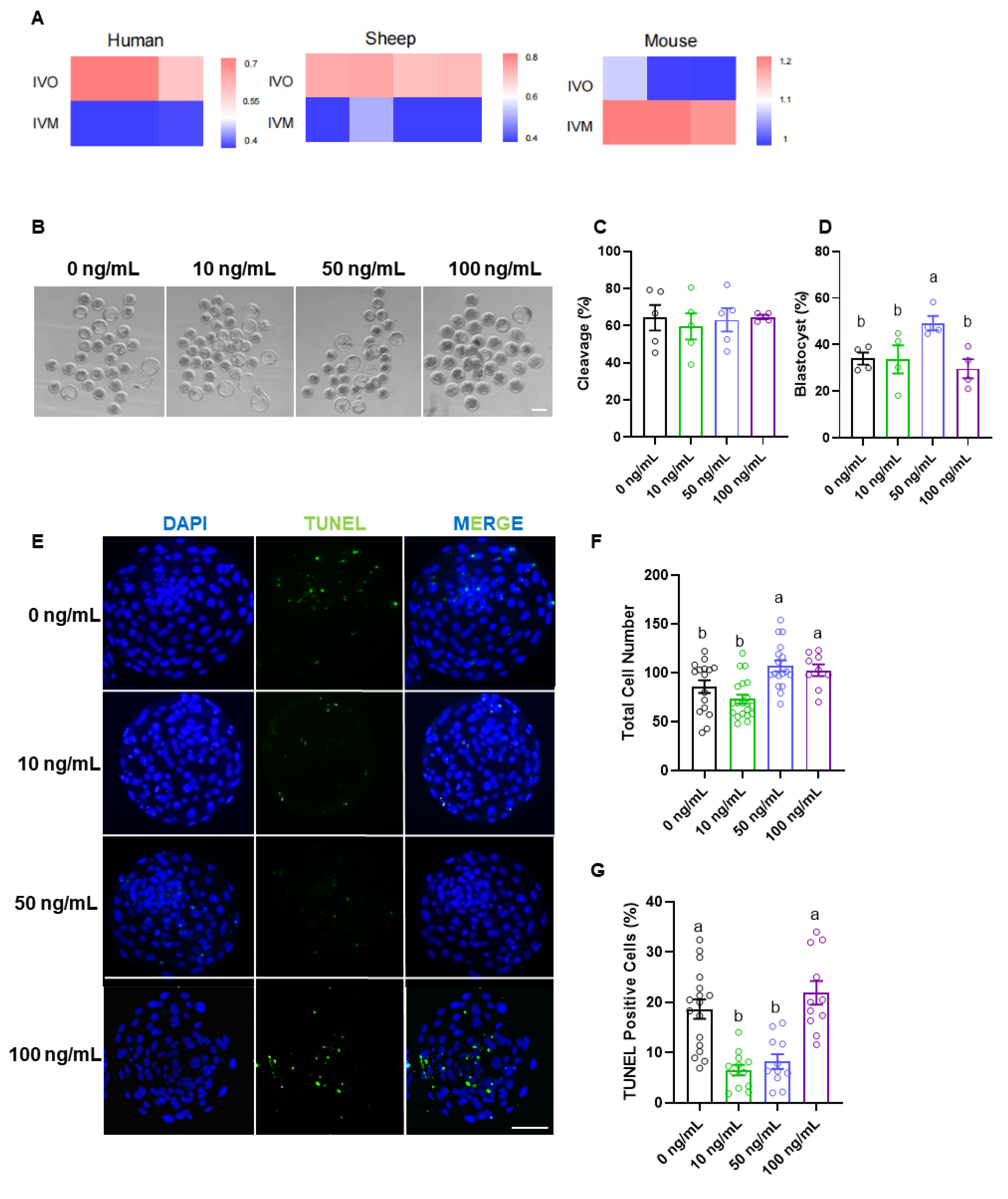

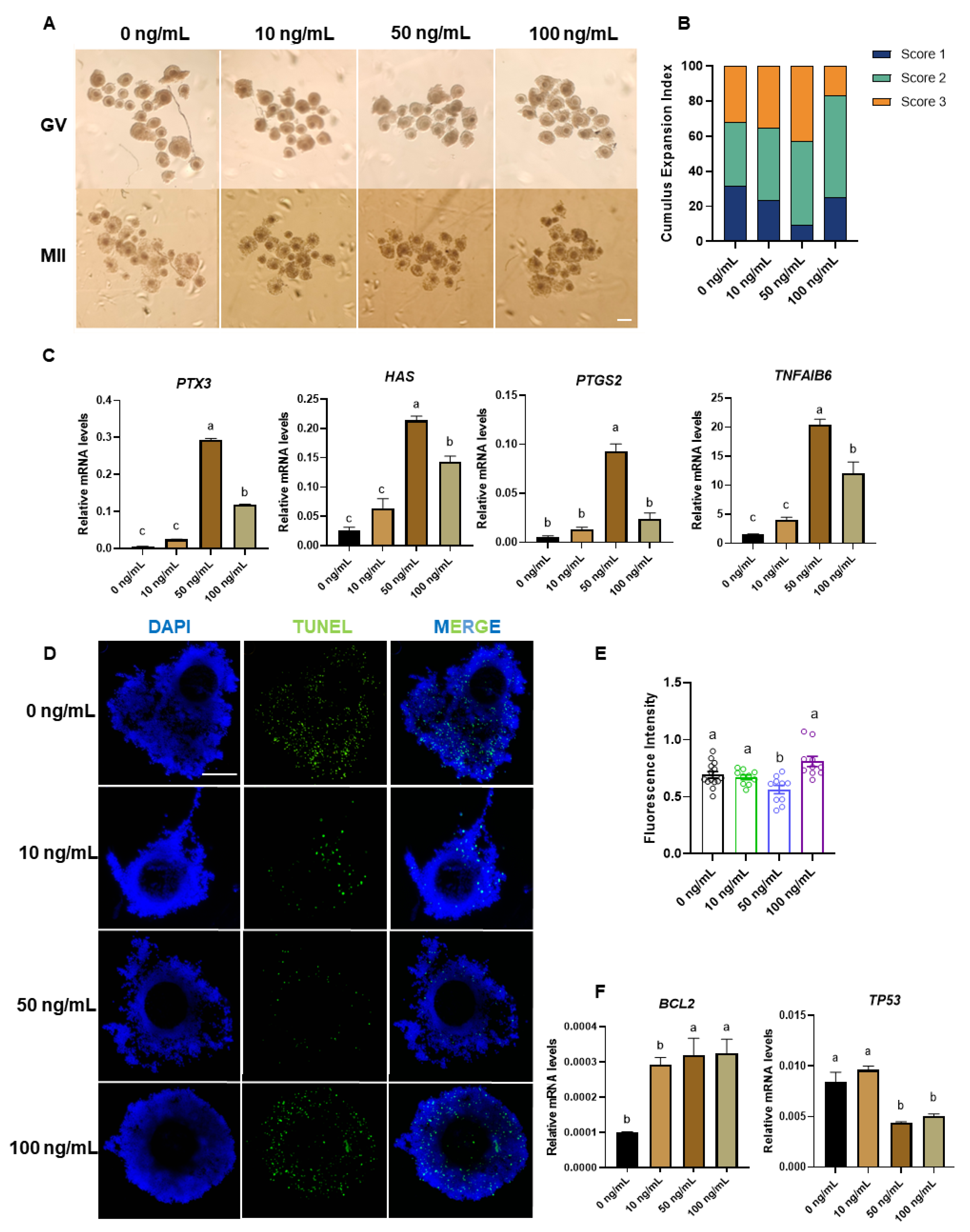

Using the ovine IVM model, we further elucidated the molecular actions of EFNA5. Supplementation with 50 ng/mL EFNA5 significantly increased blastocyst rates, with enhanced total cell numbers and reduced cell apoptosis. These findings indicate that EFNA5 may not only promotes cell proliferation but also mitigates apoptosis, thereby improving overall blastocyst quality. Such effects align with previous studies demonstrating that OFDs, including GDF9 and BMP15, regulate granulosa cell proliferation, extracellular matrix formation, and key signaling pathways to support follicle growth, ovulation, and early embryonic development [

31,

32]. Furthermore, the expansion of COCs serves as an important indicator of granulosa cell function and oocyte competence during IVM [

42]. COCs expansion reflect granulosa cell secretion of hyaluronic acid and remodeling of the extracellular matrix, processes that provide nutritional and signaling support to oocytes and maintain microenvironmental homeostasis [

21]. EFNA5 supplementation markedly increased COCs expansion and reduced oocyte apoptosis, suggesting that EFNA5 enhances oocyte-granulosa cell interactions and protects oocytes from apoptotic damage. Notably, EFNA5 exhibited an optimal concentration effect, with 50 ng/mL being most effective for improving oocyte maturation and quality, while higher doses resulted in attenuated benefits, possibly due to feedback inhibition by endogenous EFNA5. Oxidative stress and inflammation are major limiting factors for oocyte developmental competence during IVM [

43,

44]. IVM oocytes frequently exhibit elevated ROS levels, depleted glutathione, and lipid peroxidation accumulation, which disrupt intracellular redox homeostasis, increase DNA damage, and cause spindle abnormalities, ultimately restricting oocyte maturation and subsequent embryonic development [

45]. Activation of inflammatory pathways can further induce pro-apoptotic gene expression, exacerbating oocyte damage [

46,

47]. In this study, EFNA5 treatment significantly upregulated NRF2-mediated antioxidant pathways, including SOD2 and GPX4, while suppressing NF-κB signaling and downstream pro-inflammatory genes such as IL6 and TNFα. This dual regulation of oxidative stress and inflammation likely contributes to the improved oocyte quality and enhanced embryonic potential observed in EFNA5-treated groups. Complementary studies in neurons, endothelial cells, and metabolic tissues support EFNA5’s role in modulating oxidative and inflammatory responses [

48,

49].

Cell adhesion is essential for intercellular communication, microenvironmental stability, and tissue integrity, particularly in cumulus cells surrounding oocytes. Strong adhesion maintains the structural integrity of the COCs, which is critical for oocyte maturation [

50,

51]. EFNA5, as a membrane-bound ligand interacting with EphA receptors, mediates contact-dependent signaling that regulates cytoskeletal remodeling, strengthens intercellular adhesion, and stabilizes cell-matrix attachments. In neurons, EFNA5 modulates adhesion proteins such as integrins and focal adhesion components to guide axon pathfinding and synaptic stability; in endothelial cells, it promotes cell-cell junctions and vascular formation [

52,

53]. Our granulosa cell transcriptome analysis suggests that EFNA5 may enhance adhesion-related gene expression, indicating a potential mechanism for improved COCs stability and oocyte support, although functional validation of key adhesion molecules is warranted.

Here, we provide the first comprehensive evidence establishing EFNA5 as a newly identified oocyte-derived factor that significantly improves IVM performance. EFNA5 improves antioxidant capacity, suppresses inflammatory signaling, reduces apoptosis, and potentially regulates cell adhesion and motility, thereby optimizing the oocyte microenvironment and maintaining blastocyst quality. In conclusion, EFNA5 provides a novel molecular foundation for optimizing IVM systems and offers critical insights into the function of oocyte-derived factors. Further elucidation of the synergistic effects of multiple oocyte-derived factors could pave the way for enhancing mammalian oocyte developmental competence and refining clinical ART strategies.

Author Contributions

X.L.: Writing-review & editing, Writing-original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation. J.C.: Writing-original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation. Y.W.: Visualization, Formal analysis. J.H.: Data curation. D.C.: Data curation. L.C.: Supervision, Data curation. H.H.: Data curation. L.A.: Supervision, Data curation. J.T.: Writing-review & editing, Resources, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. G.X.: Writing-review & editing, Visualization, Software, Formal analysis, Supervision, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

The expression pattern of EFNA5 and EPHA4 in COCs. (A) Cross-species heatmaps of EFNA family expression in GV and MII oocytes (row-scaled Z-scores). (B) The expression of EFNA5 transcript in GV and MII oocytes from multiple species. (C) Western blots of EFNA5 in cumulus cells and oocytes with densitometry normalized to GAPDH. (D) Immunofluorescence localization of EFNA5 in COCs (DAPI, blue; EFNA5, red). Scale bars = 50 µm. (E) qRT-PCR quantification of EFNA5 and EphA receptors in oocytes and cumulus cells (row-scaled Z-scores). (F) Immunofluorescence of EPHA4 in COCs (DAPI, blue; EPHA4, red). Scale bars = 50 µm. Abbreviations: OO, oocyte; CC, cumulus cell; GV, germinal vesicle; MII, metaphase II. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 1.

The expression pattern of EFNA5 and EPHA4 in COCs. (A) Cross-species heatmaps of EFNA family expression in GV and MII oocytes (row-scaled Z-scores). (B) The expression of EFNA5 transcript in GV and MII oocytes from multiple species. (C) Western blots of EFNA5 in cumulus cells and oocytes with densitometry normalized to GAPDH. (D) Immunofluorescence localization of EFNA5 in COCs (DAPI, blue; EFNA5, red). Scale bars = 50 µm. (E) qRT-PCR quantification of EFNA5 and EphA receptors in oocytes and cumulus cells (row-scaled Z-scores). (F) Immunofluorescence of EPHA4 in COCs (DAPI, blue; EPHA4, red). Scale bars = 50 µm. Abbreviations: OO, oocyte; CC, cumulus cell; GV, germinal vesicle; MII, metaphase II. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Figure 2.

EFNA5 enhances the oocyte developmental competence. (A) Cross-species heatmaps comparing EFNA5 expression IVO and IVM oocytes from human, mouse, sheep and mouse (row-scaled Z-scores). (B) Representative bright-field images of embryos derived from oocytes matured with 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL recombinant EFNA5. Scale bar = 200 µm. (C-D) Cleavage rate and blastocyst rate for each group. (E) Representative images of blastocysts stained with DAPI (blue) and TUNEL (green). Scale bar = 50 µm. (F-G) Total cell number and percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei per blastocyst. Abbreviations: IVO, in vivo maturation; IVM, in vitro maturation. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate p < 0.05.

Figure 2.

EFNA5 enhances the oocyte developmental competence. (A) Cross-species heatmaps comparing EFNA5 expression IVO and IVM oocytes from human, mouse, sheep and mouse (row-scaled Z-scores). (B) Representative bright-field images of embryos derived from oocytes matured with 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL recombinant EFNA5. Scale bar = 200 µm. (C-D) Cleavage rate and blastocyst rate for each group. (E) Representative images of blastocysts stained with DAPI (blue) and TUNEL (green). Scale bar = 50 µm. (F-G) Total cell number and percentage of TUNEL-positive nuclei per blastocyst. Abbreviations: IVO, in vivo maturation; IVM, in vitro maturation. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

EFNA5 promotes cumulus expansion and suppresses apoptosis in cumulus–oocyte complexes. (A) Bright-field images of GV and MII stage COCs matured with 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL EFNA5. Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) Distribution of cumulus expansion scores (Score 1, minimal; Score 2, moderate; Score 3, full) under each EFNA5 dose. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of cumulus-expansion genes (PTX3, HAS2, PTGS2, TNFAIP6) in COCs after IVM. (D) Representative images of TUNEL staining in COCs matured with the indicated EFNA5 doses (DAPI, blue; TUNEL, green). Scale bar = 50 µm. (E) Quantification of TUNEL fluorescence intensity in COCs. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of apoptosis-related genes (BCL2 and TP53) in COCs. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

EFNA5 promotes cumulus expansion and suppresses apoptosis in cumulus–oocyte complexes. (A) Bright-field images of GV and MII stage COCs matured with 0, 10, 50, or 100 ng/mL EFNA5. Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) Distribution of cumulus expansion scores (Score 1, minimal; Score 2, moderate; Score 3, full) under each EFNA5 dose. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of cumulus-expansion genes (PTX3, HAS2, PTGS2, TNFAIP6) in COCs after IVM. (D) Representative images of TUNEL staining in COCs matured with the indicated EFNA5 doses (DAPI, blue; TUNEL, green). Scale bar = 50 µm. (E) Quantification of TUNEL fluorescence intensity in COCs. (F) qRT-PCR analysis of apoptosis-related genes (BCL2 and TP53) in COCs. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are mean ± SEM. Different letters indicate p < 0.05.

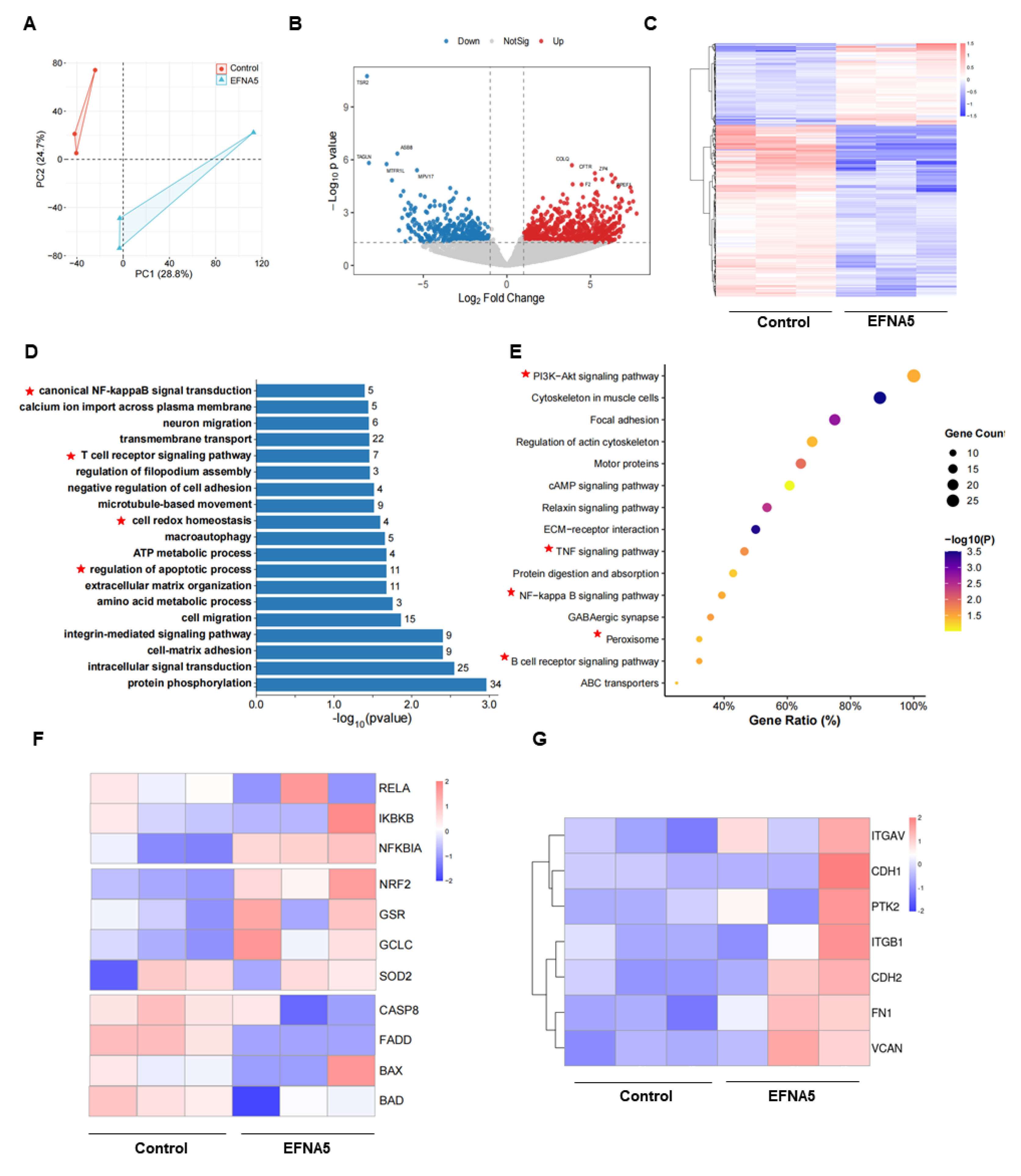

Figure 4.

Effects of EFNA5 on the transcriptional profile of oocytes matured in vitro. (A) PCA of MII oocyte transcriptomes in control and EFNA5 groups. (B) Volcano plot of DEGs; dashed lines indicate |log2FC| = 1.5 and pvalue = 0.05. Red, upregulated; blue, downregulated; grey, not significant. (C) Heatmap of DEGs across samples with hierarchical clustering (row-scaled Z-scores). (D) GO enrichment (BP/CC/MF); bar length denotes-log10(P), numbers indicate gene counts. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment; bubble size represents gene count, color indicates-log10(P), x-axis shows Gene Ratio. (F–H) Module heatmaps for antioxidant (NRF2 targets), inflammatory (NF-κB axis), and apoptotic genes (row-scaled Z-scores). (I) GSEA enrichment plots for Glutathione metabolism, NF-κB signaling, and p53 pathway. (J) PPI network of core DEGs with hub nodes (node size = degree; edge thickness = interaction confidence). Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; BP/CC/MF, biological process/cellular component/molecular function.

Figure 4.

Effects of EFNA5 on the transcriptional profile of oocytes matured in vitro. (A) PCA of MII oocyte transcriptomes in control and EFNA5 groups. (B) Volcano plot of DEGs; dashed lines indicate |log2FC| = 1.5 and pvalue = 0.05. Red, upregulated; blue, downregulated; grey, not significant. (C) Heatmap of DEGs across samples with hierarchical clustering (row-scaled Z-scores). (D) GO enrichment (BP/CC/MF); bar length denotes-log10(P), numbers indicate gene counts. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment; bubble size represents gene count, color indicates-log10(P), x-axis shows Gene Ratio. (F–H) Module heatmaps for antioxidant (NRF2 targets), inflammatory (NF-κB axis), and apoptotic genes (row-scaled Z-scores). (I) GSEA enrichment plots for Glutathione metabolism, NF-κB signaling, and p53 pathway. (J) PPI network of core DEGs with hub nodes (node size = degree; edge thickness = interaction confidence). Abbreviations: DEG, differentially expressed gene; BP/CC/MF, biological process/cellular component/molecular function.

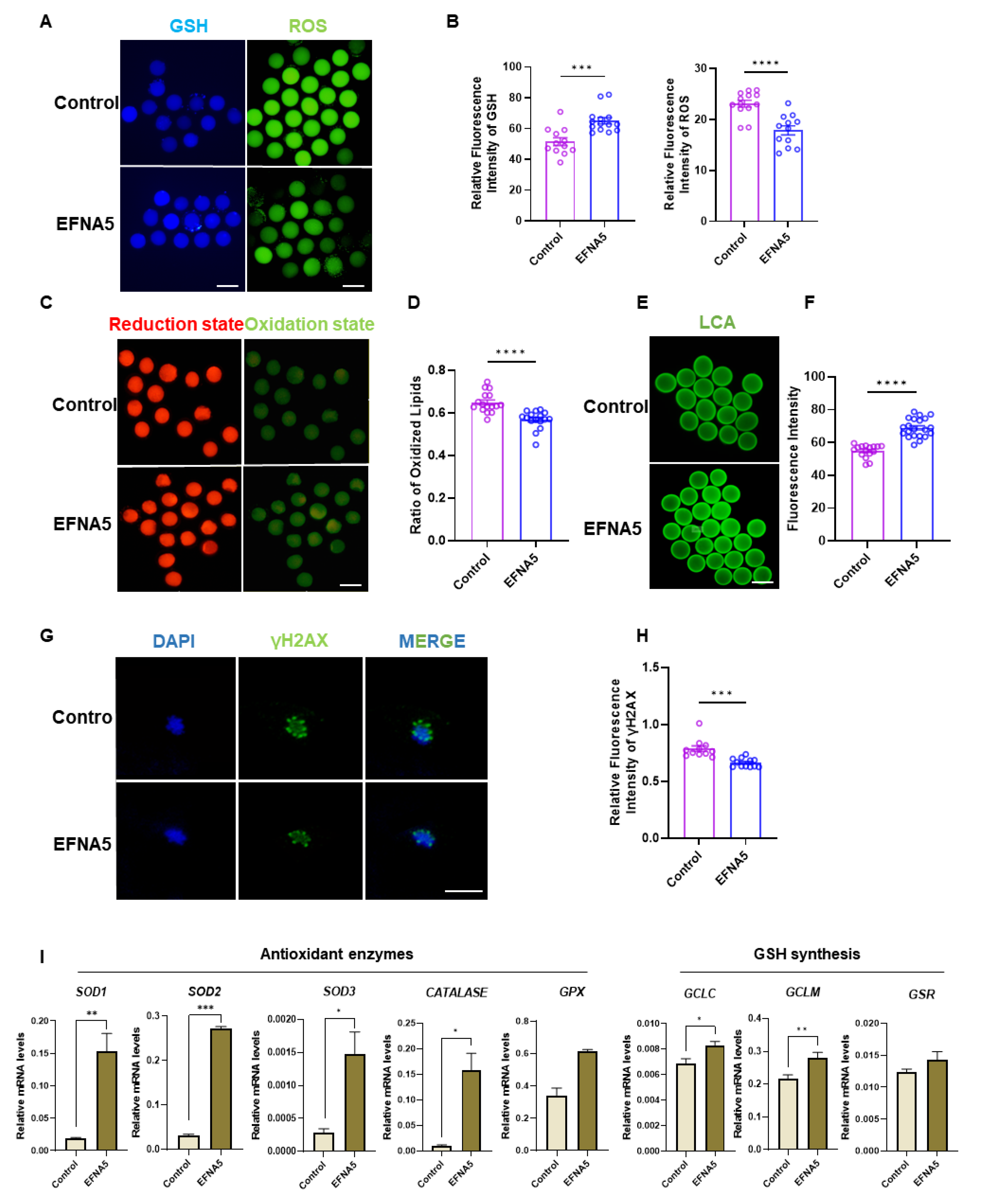

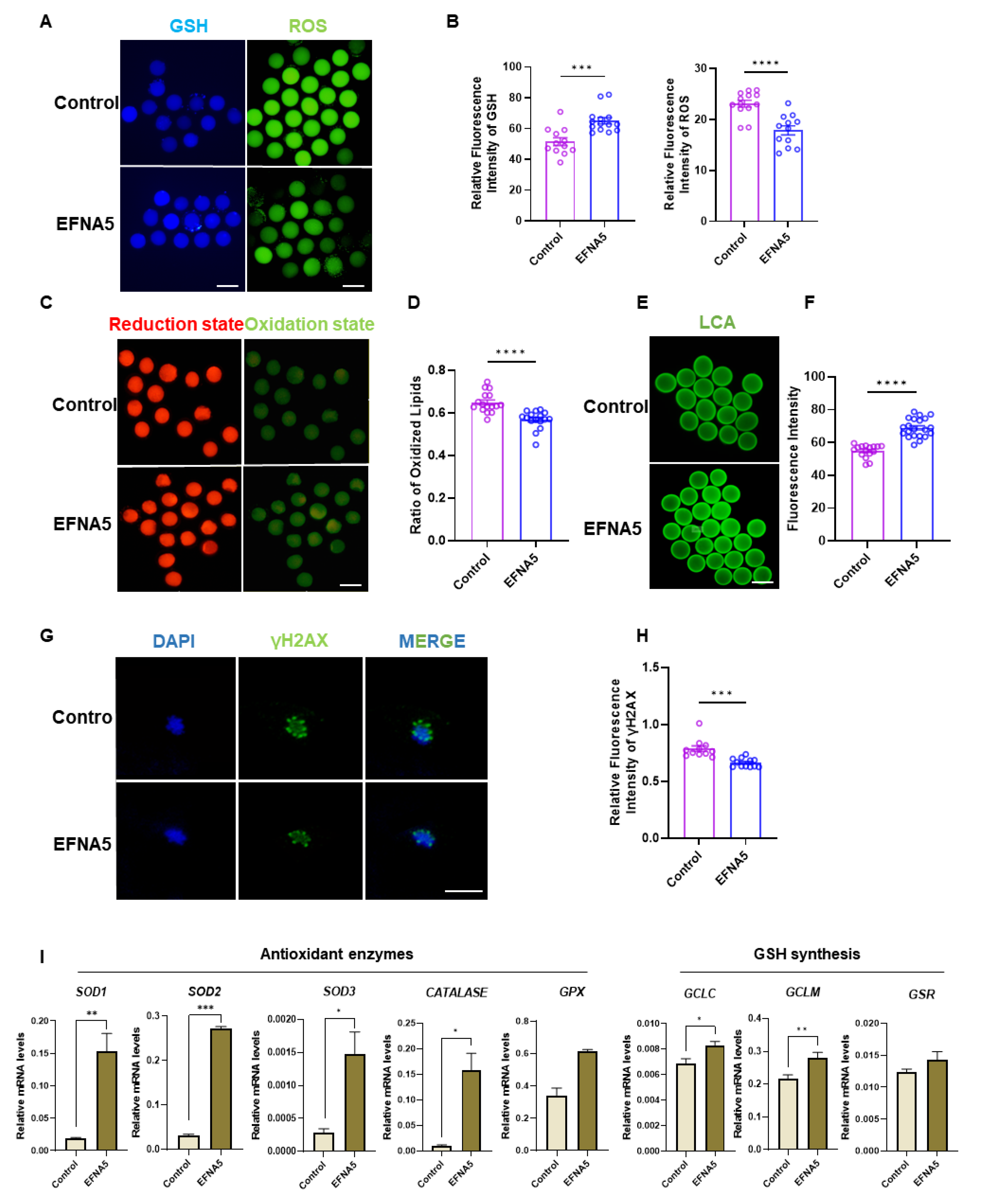

Figure 5.

EFNA5 improves oocyte redox homeostasis and oocyte quality. (A) Representative fluorescence images of intracellular GSH (left) and ROS (right) in control versus EFNA5-treated oocytes. Scale bar = 50 µm. (B) Quantification of relative fluorescence intensity for GSH (left) and ROS (right). (C) C11-BODIPY 581/591 labeling of lipid peroxidation showing reduced (red) and oxidized (green) states. Scale bar = 50 µm. (D) Ratio of oxidized/reduced C11-BODIPY signals. (E) LCA lectin staining of cortical granules in MII oocytes. Scale bar = 50 µm. (F) Quantification of LCA fluorescence intensity. (G) Immunofluorescence of γH2AX (green) indicating DNA damage (DAPI, blue). Scale bar = 20 µm. (H) Quantification of relative γH2AX fluorescence intensity. (I) qPCR analysis of antioxidant enzyme genes (SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, CATALASE, GPX) and GSH synthesis/regeneration genes (GCLC, GCLM, GSR) in Control versus EFNA5-treated oocytes. Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; ROS, reactive oxygen species; LCA, Lens culinaris agglutinin; γH2AX, phospho-H2AX (Ser139). All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 5.

EFNA5 improves oocyte redox homeostasis and oocyte quality. (A) Representative fluorescence images of intracellular GSH (left) and ROS (right) in control versus EFNA5-treated oocytes. Scale bar = 50 µm. (B) Quantification of relative fluorescence intensity for GSH (left) and ROS (right). (C) C11-BODIPY 581/591 labeling of lipid peroxidation showing reduced (red) and oxidized (green) states. Scale bar = 50 µm. (D) Ratio of oxidized/reduced C11-BODIPY signals. (E) LCA lectin staining of cortical granules in MII oocytes. Scale bar = 50 µm. (F) Quantification of LCA fluorescence intensity. (G) Immunofluorescence of γH2AX (green) indicating DNA damage (DAPI, blue). Scale bar = 20 µm. (H) Quantification of relative γH2AX fluorescence intensity. (I) qPCR analysis of antioxidant enzyme genes (SOD1, SOD2, SOD3, CATALASE, GPX) and GSH synthesis/regeneration genes (GCLC, GCLM, GSR) in Control versus EFNA5-treated oocytes. Abbreviations: GSH, glutathione; ROS, reactive oxygen species; LCA, Lens culinaris agglutinin; γH2AX, phospho-H2AX (Ser139). All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

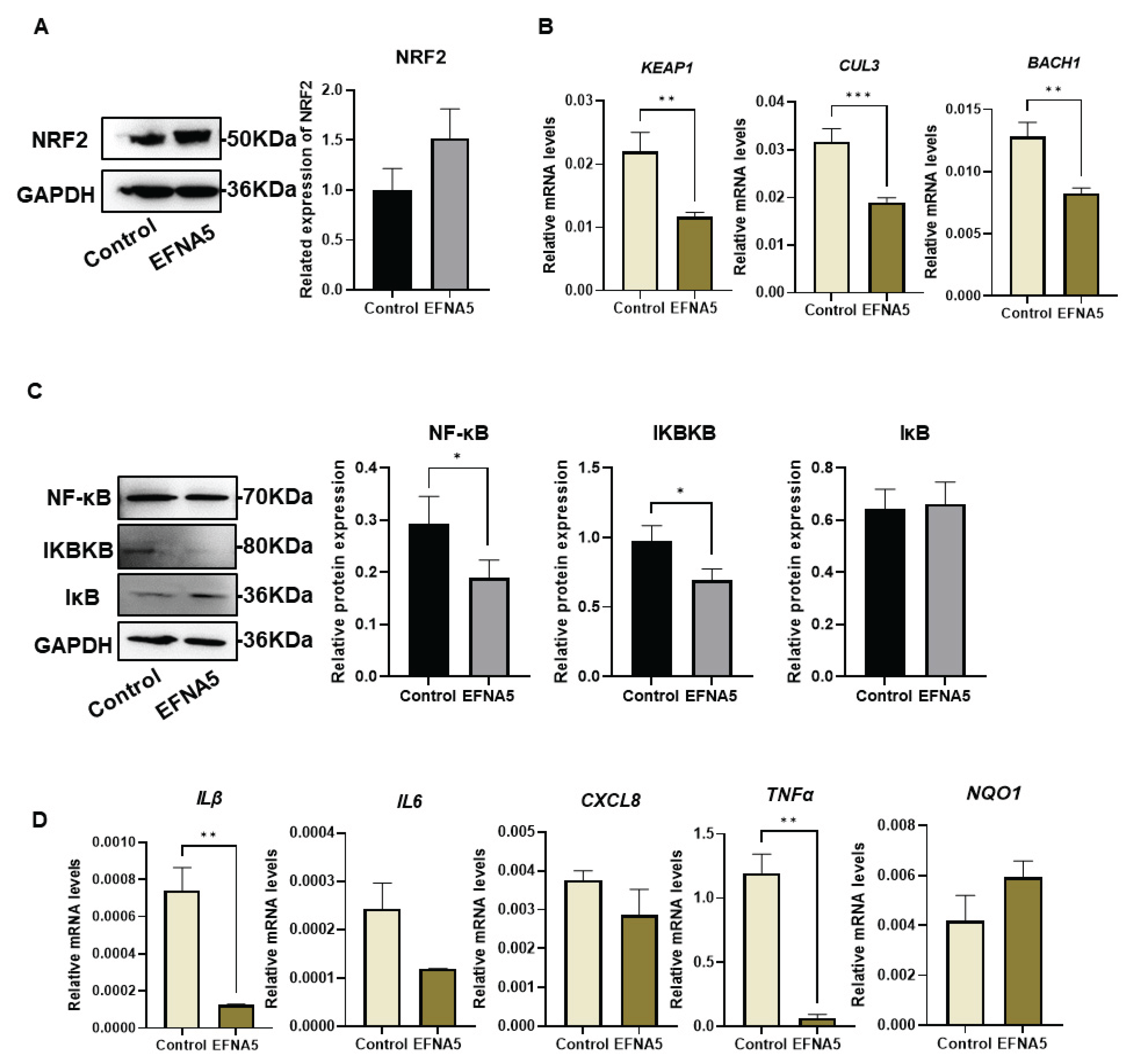

Figure 6.

EFNA5 reprograms cumulus cell transcriptomes. (A) PCA of RNA-seq profiles from control vs EFNA5-treated cumulus cells. (B) Volcano plot of DEGs; dashed lines denote thresholds |log2FC| = 1.5 and pvalue = 0.05. Red: upregulated; blue: downregulated; gray: not significant. (C) Heatmap of DEGs across samples with hierarchical clustering (row-scaled Z-scores; columns: biological replicates). (D) Gene Ontology enrichment (BP/CC/MF). Bars indicate-log10(P); numbers at bar ends show gene counts. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment. Bubble size represents gene count; color encodes -log10(P); x-axis shows Gene Ratio. (F) Module heatmap highlighting key pathways in cumulus cells: NF-κB axis (RELA, IKBKB, NFKBIA), NRF2 antioxidant genes (NRF2, GSR, GCLC, SOD2), and apoptosis genes (CASP8, FADD, BAX, BAD). (G) Adhesion-related gene heatmap (row-scaled Z-scores), including ITGAV, ITGB1, CDH1, CDH2, PTK2, FN1, VCAN.

Figure 6.

EFNA5 reprograms cumulus cell transcriptomes. (A) PCA of RNA-seq profiles from control vs EFNA5-treated cumulus cells. (B) Volcano plot of DEGs; dashed lines denote thresholds |log2FC| = 1.5 and pvalue = 0.05. Red: upregulated; blue: downregulated; gray: not significant. (C) Heatmap of DEGs across samples with hierarchical clustering (row-scaled Z-scores; columns: biological replicates). (D) Gene Ontology enrichment (BP/CC/MF). Bars indicate-log10(P); numbers at bar ends show gene counts. (E) KEGG pathway enrichment. Bubble size represents gene count; color encodes -log10(P); x-axis shows Gene Ratio. (F) Module heatmap highlighting key pathways in cumulus cells: NF-κB axis (RELA, IKBKB, NFKBIA), NRF2 antioxidant genes (NRF2, GSR, GCLC, SOD2), and apoptosis genes (CASP8, FADD, BAX, BAD). (G) Adhesion-related gene heatmap (row-scaled Z-scores), including ITGAV, ITGB1, CDH1, CDH2, PTK2, FN1, VCAN.

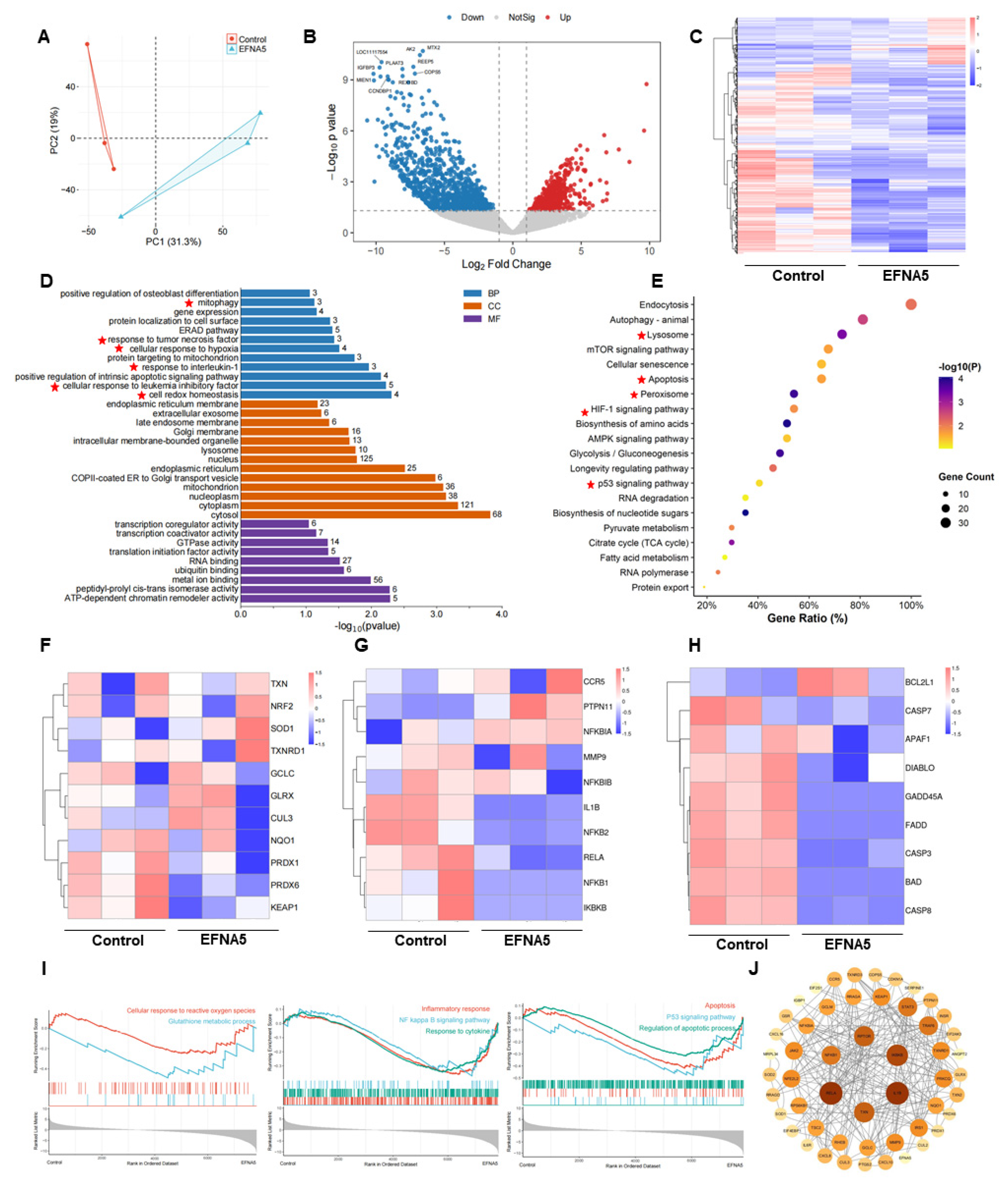

Figure 7.

EFNA5 activates NRF2 signaling and suppresses NF-κB activity in COCs. (A) Western blot and densitometry of NRF2 in control and EFNA5 groups. Note: The blot image was horizontally flipped to align with the sample order described in the legend. (B) Relative mRNA levels of KEAP1, CUL3, and BACH1 in control and EFNA5 groups. (C) Western blots and densitometry of NF-κB (p65), IKBKB, and IκB. (D) Relative mRNA levels of IL1β, IL6, CXCL8, NQO1, and TNFα in control and EFNA5 groups. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

EFNA5 activates NRF2 signaling and suppresses NF-κB activity in COCs. (A) Western blot and densitometry of NRF2 in control and EFNA5 groups. Note: The blot image was horizontally flipped to align with the sample order described in the legend. (B) Relative mRNA levels of KEAP1, CUL3, and BACH1 in control and EFNA5 groups. (C) Western blots and densitometry of NF-κB (p65), IKBKB, and IκB. (D) Relative mRNA levels of IL1β, IL6, CXCL8, NQO1, and TNFα in control and EFNA5 groups. All experiments were repeated at least three times. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.