1. Introduction

The low reproductive efficiency (LRE) of alpacas (

Vicugna pacos) is currently a major concern. Over the past decades, fertility and birth rates have fallen below 45% and 50%, respectively [

1]. One of the reasons of LRE is early embryonic loss after mating, associated with poor gamete quality [

2]. Moreover, in vitro embryo production (IVP) has barely started compared to other ruminant species, such as bovine [

3,

4], where this technology has become efficient enough to be considered for commercial use and used for animal breeding. However, in South American camelids, is necessary to optimize in vitro maturation (IVM), fertilization (IVF) and embryo culture procedures to establish a consistent and replicable IVP process [

5].

Unlike in mice or humans, where eggs are mainly collected at the metaphase II (MII) stage, in many livestock species the oocytes must be matured in vitro since the most common source of oocytes comes from slaughtered animals [

6]. During IVM, immature oocytes obtained from small follicles must undergo nuclear and cytoplasmic maturity to be considered competent enough to support embryonic development [

7]. Nuclear maturation lies in the progression of the oocyte through meiotic processes to reach and arrest at the meiosis II stage. Cytoplasmic maturation, instead, involves accumulating and redistributing organelles, RNA, and proteins associated with early embryonic competence [

8]. These processes can be induced in vitro by cultivating the oocytes under the appropriate conditions. In this line, several studies have shown that the supplementation of the IVM medium with antioxidant molecules, such as resveratrol, enhance oocyte quality of bovine [

9,

10] and porcine [

11,

12] species.

On the other hand, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assay is considered as gold standard method for assessing gene expression changes by quantifying at the transcript level. However, qRT-PCR assays are prone to errors and sensitive to experimental variations, so all potential bias factors need to be controlled and minimized to perform an adequate study [

13]. These variables are usually controlled by normalizing the data against reference (housekeeping) transcripts, which theoretically should be consistently present regardless of tissue and/or experimental condition [

14]. Nonetheless, in developmental biology, the stability of reference genes depends on the developmental stage and experimental setting, so their validation is essential for each model and species evaluated. For instance, classic reference genes such as

Gapdh (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase) and

Actb (β-actin) have been used to compare transcripts levels of different target genes during oocyte IVM and early embryonic development [

15,

16,

17]. Though, the levels of these reference genes can be significantly regulated in different cell types and experimental conditions, which does not guarantee their stability [

18].

Therefore, this study aimed to identify suitable reference genes for accurate gene expression analysis during in vitro maturation of alpaca oocytes. Four candidate reference genes (Gapdh, Actb, Rplp0 and Ppia), were selected and their stability was evaluated after IVM of oocytes exposed or not at different concentrations of resveratrol. Additionally, the levels of two target transcripts were normalized by the selected reference genes.

2. Materials and Methods

All chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise specified. All experimental procedures were carried out at the Laboratory of Reproductive Physiology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biological Sciences, UNMSM (approval code: N° 106-2024-CBE-FCB-UNMSM, October 2, 2024).

2.1. Oocyte Collection and IVM

Ovaries were collected from a local slaughterhouse located in Huancavelica city, Peru, and transported to the laboratory in normal saline solution at 10°C within 15-22 h after collection. Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from antral follicles of 3-8 mm in diameter. Subsequently, 903 COCs with at least three layers of surrounding cumulus cells and homogeneous cytoplasm, classified as category I or II were selected for IVM and cultured in tissue culture medium-199 (TCM-199, Gibco/BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) supplemented with 2.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 10 IU/mL equine chorionic gonadotropin (eCG, Novormon), 0.1 IU/mL human corion gonadotropin (hCG, Sigma-Aldrich, United States), 0.07 IU/mL follicle stimulating hormone (FSH, Folltropin-Bioniche, Canada), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, United States), 0.2 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich, United States), 1 µg/mL β-estradiol (Sigma-Aldrich, United States), 10 ng/mL epidermic grown factor (eGF, Sigma-Aldrich, United States) and 50 µg/mL gentamicin (Sigma-Aldrich, United States). In vitro culture was carried during 48 h at 38.5°C in an atmosphere with 5% CO2.

After IVM, oocytes were denuded of cumulus cells mechanically, and those displaying extrusion of the first polar body were considered as reached nuclear maturity. The mature oocytes were then washed in PBS and stored in micro tubes containing RNA Preserve (Norgen Biotek, Canada)/PBS (1:3) at -20°C for further analysis.

2.2. Total RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted from three independent pools (obtained from different ovary collections) of twenty mature oocytes in each group using the Single Cell RNA Purification Kit (Norgen Biotek, Canada) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. The elution volume was 10 µL. Reverse transcription was performed using the TruScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit for mRNA (Norgen Biotek, Canada) with 5 µL of RNA in a final reaction volume of 20 µL, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The reaction was incubated in a MultigeneTM Mini Personal thermocycler (Labnet) at 50°C for 45 minutes and then at 70°C for 15 minutes. The resulting cDNA was stored at -20°C until further use.

2.3. Primer Design and Amplification Efficiency

To confirm primers specificity, conventional RT-PCR was performed using cDNA from alpaca oocytes. The amplicon size and absence of primer dimers were confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1.5% agarose gel. Additionally, qRT-PCR standard curves were constructed from 5-fold serial dilutions of a pool of cDNA to evaluate the amplification efficiency (E% = (10

(−1/slope) − 1) × 100%) of all genes [

19].

2.4. Quantitative RT-PCR

The qRT-PCR was conducted using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR Systems (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California) in 10-µL reactions containing: 1 µL cDNA, 5 µL KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Master Mix (2x) Universal (KapaBiosystems, United States), 0.4 µL (0.4 mM) forward and reverse primers, 0.2 µL 50x High ROX and nuclease-free water. Reaction conditions were as follows: 95°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 20 s. After 40 cycles, a melt curve was generated by 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min and 95°C for 15 s with a ramp rate of 2%. Melt curve analyses were performed for all genes, and the specificity as well as integrity of the PCR products was confirmed by the presence of a single peak. For each biological sample, two technical replicates were run in each qRT-PCR experiment, and all samples for each gene were performed on the same run to minimize inter experimental variation.

2.5. Stability of Candidate Reference Genes and Determination of the Transcript Levels of Bmp15 and Sirt1

To evaluate transcript stability during IVM, the COCs were cultured under 3 different conditions: group 1 was cultured in the regular IVM medium (control); group 2 was cultured in the regular IVM medium supplemented with 2 µM of resveratrol (Resv 2 µM), and group 3 was cultured in the regular IVM medium supplemented with 10 µM of resveratrol (Resv 10 µM). The experiment was repeated at least ten times (10 biological replicates). For gene expression analysis, three pools of 20 oocytes from each experimental group were evaluated (3 biological replicates). The RefFinder algorithm was used to compare and rank the tested candidate reference genes. RefFinder integrates four algorithms (Normfinder, BestKeeper, ΔCt method, and geNorm). It assigns weights to each gene and generates a comprehensive evaluation, providing a reliable assessment of transcript stability. Expression levels of Bmp15 and Sirt1 were calculated using the modified ΔΔCt method described by Pfaffl (2001), which incorporates the amplification efficiency (E) of each primer pair. For each independent qPCR run, the expression of the control group was normalized and assigned a relative value of 1. Subsequently, relative expression values of the treatment groups from all runs were pooled and subjected to statistical analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences among groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Binomial data sets, such as maturation rate, was analyzed by using Fisher’s exact test. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. In Vitro Maturation of Alpaca Oocytes

The maturation rate after IVM is shown in

Table 2. Supplementation with 2 µM of resveratrol significantly increased the maturation rate compared to both the control group (39.9% vs. 28.1%, p = 0.0053) and the group supplemented with 10 µM of resveratrol (39.9% vs. 26.8%, p = 0.0012).

3.2. Specificity and Amplification Efficiency

The amplification specificity for all transcripts assessed was confirmed by the presence of a single band showing the expected size for each PCR product (

Figure S1) and by the presence of a single sharp peak in the melting curve analysis (

File S1). The amplification efficiency for the four candidate reference genes and target genes remained in the range of 90.96 % to 101.10% with an R

2 values > 0.995 (

File S1).

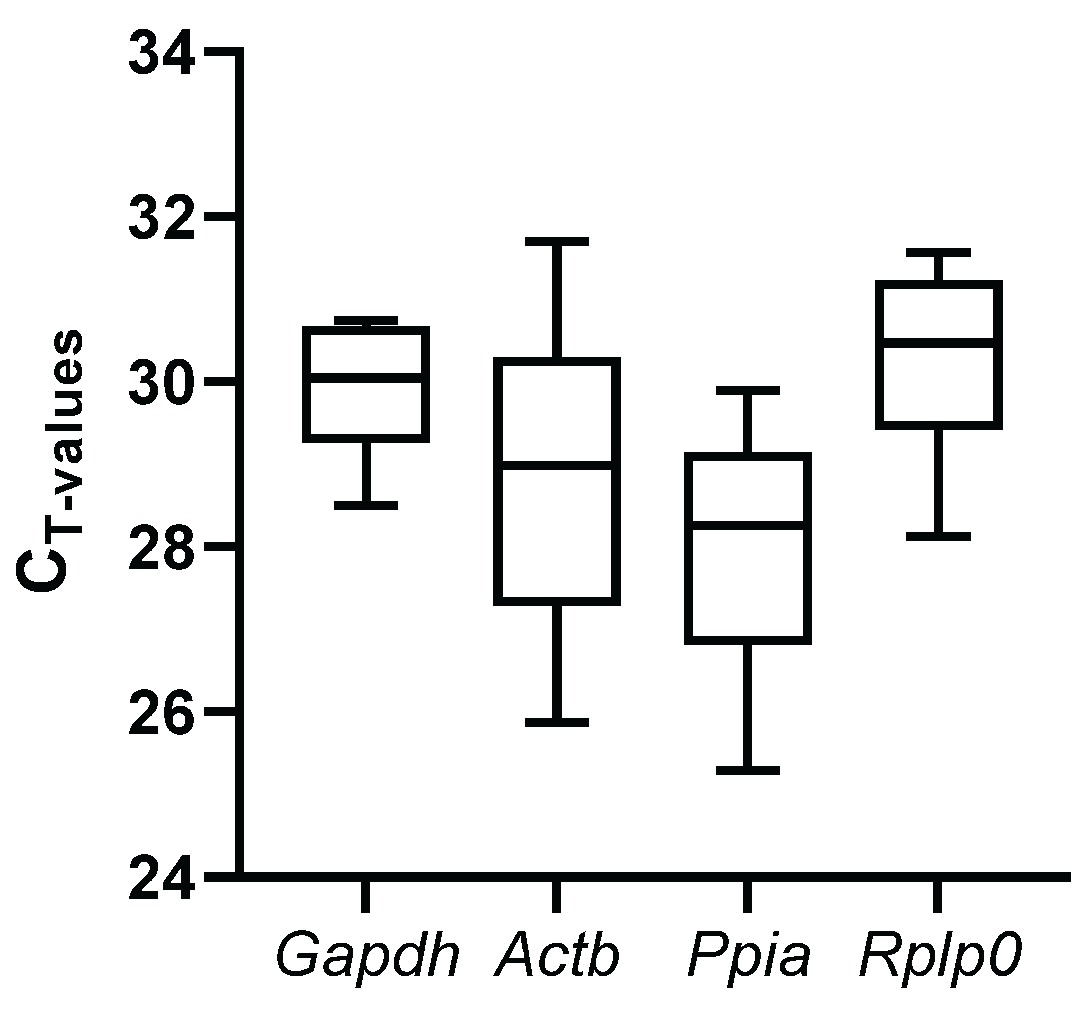

3.3. Cycle Threshold (Ct) Values and Variations in RGs

For each candidate reference gene, Ct values were analyzed to compare the transcription levels (

Figure 1,

Suppl. Table S1). Under all of the experimental conditions, raw Ct values varied from 25.3 to 31.7. Ppia, showed the lowest median Ct value (27.9), whereas Rplp0 the highest Ct value (30.3), suggesting the highest and lowest expression levels, respectively, among the candidate genes. On the other hand, Gapdh and Rplp0 showed the smallest variance among replicates, whereas Actb had the highest variance, suggesting them as the most stable and the most variable, respectively.

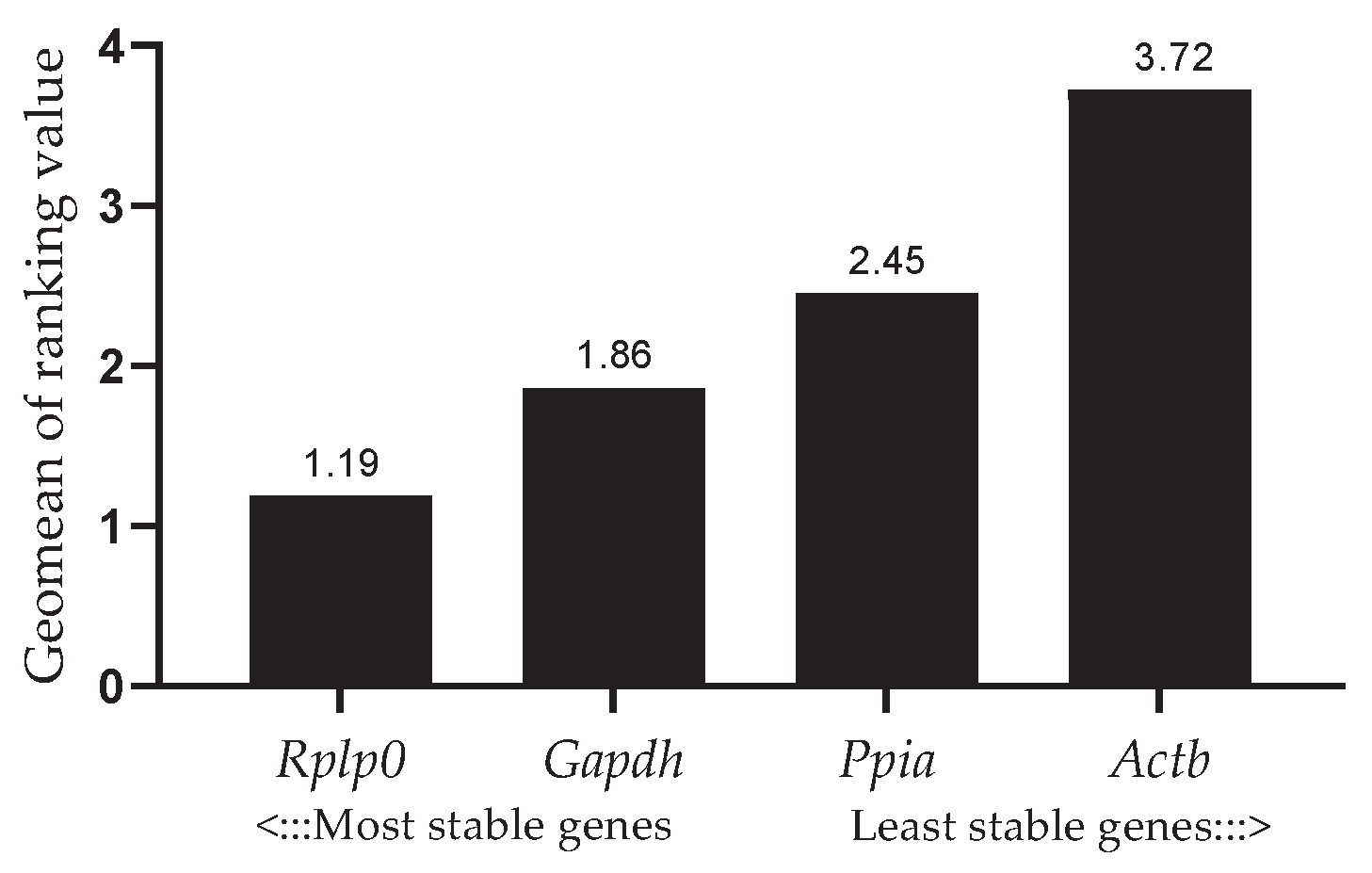

3.4. Stability of Candidate Reference Genes

As show in

Table 3, Rplp0 obtained the best rank according to NormFinder and ΔCt methods (

Table 3), whereas Gapdh ranked highest according to BestKeeper and was tied with Rplp0 in GeNorm. On the other hand, Actb got the lowest rank according to all algorithms, except for NormFinder. The overall ranking generated by RefFinder was Rplp0 > Gapdh > Ppia > Actb (

Figure 2).

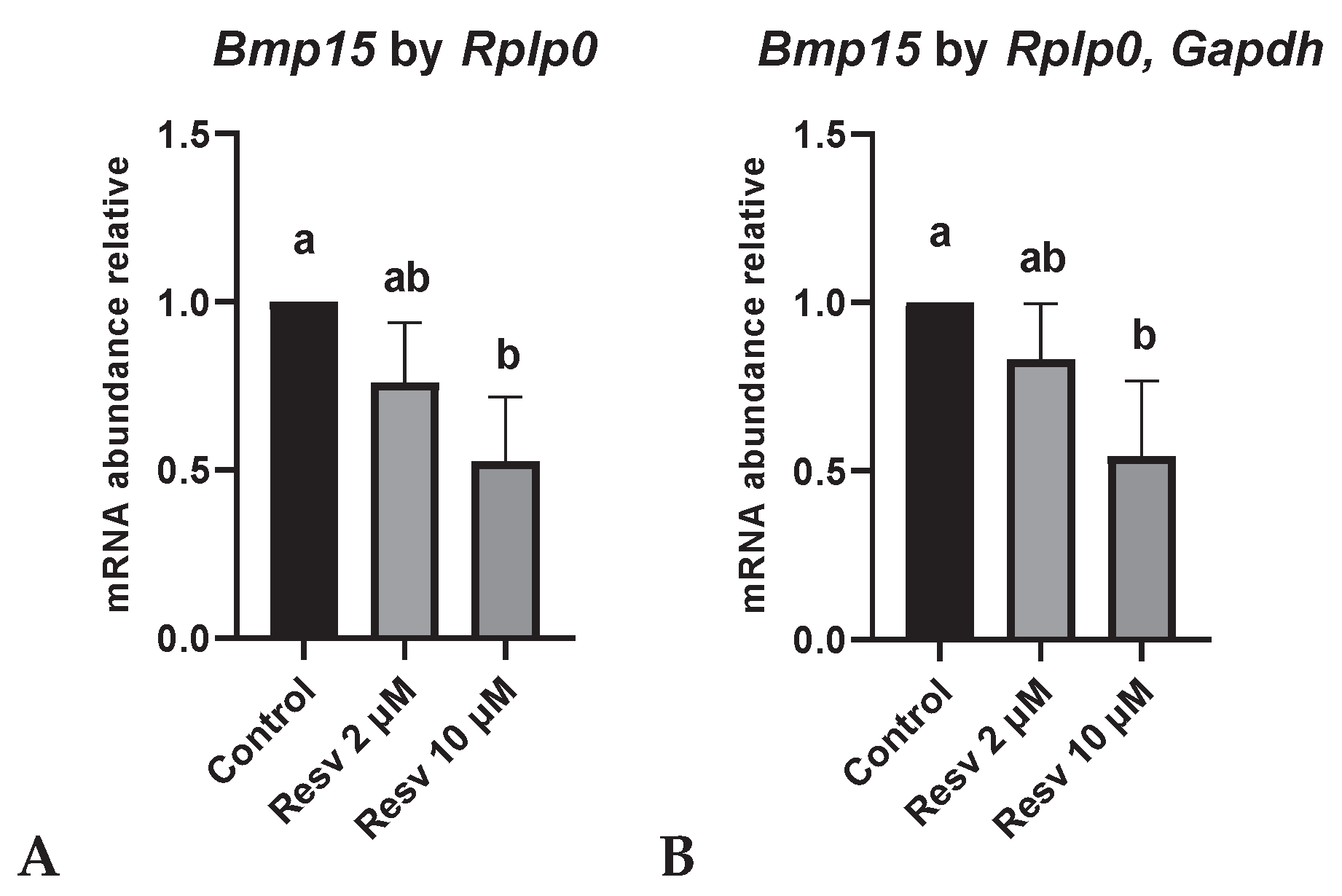

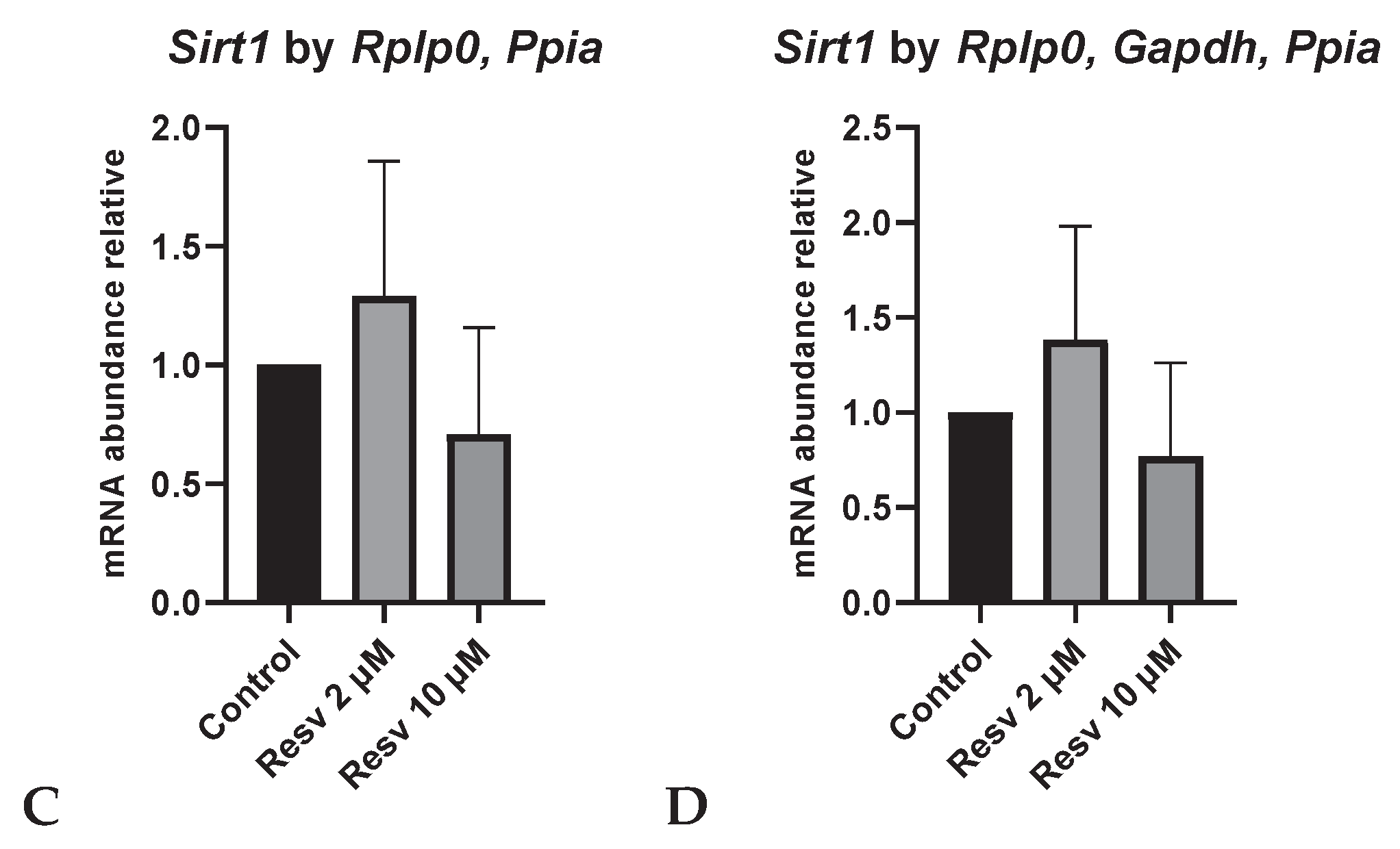

3.5. Determination of the Sirt1 and Bmp15 Expression Profile

The relative expression of Bmp15 was normalized using the most stable gene (Rplp0) and the combination of the two most stable genes (Rplp0 and Gapdh) (

Figure 3A,B, respectively). In both cases, Bmp15 expression was higher in the control group compared to the 10 µM resveratrol group (p<0.05). A similar pattern of expression was observed when normalization as performed using Rplp0, Gapdh and Ppia (

Figure S2). In contrast, when Bmp15 expression was normalized using Ppia or Actb alone, distinct expression patterns were observed (

Figure S2). No differences in Sirt1 expression were observed among groups, regardless of the reference gene used. Similar trends were observed when normalized with

Rplp0 or the combination of

Rplp0 and

Gapdh (

Figure 3C,D) as well as with other reference genes, with the exception of

Actb (

Figure S2)

4. Discussion

Suitable reference genes are those that are expressed constantly from the cells under different experimental conditions and that serve as endogenous controls to normalize the data obtained by techniques such as qRT-PCR [

20]. Selecting a suitable reference gene is crucial to obtain reliable and reproducible results in gene expression analysis [

21,

22]. However, there is no universal genes that can be used as a reference in all cases, so it is necessary to validate the stability of candidate transcripts in each biological system and/or experimental condition prior to their use in qRT-PCR assays [

23]. For instance, Cadenas et al. evaluated five RGs in human ovarian cortex under different culture condition and found that

Gapdh was the optimal RG for culture supplemented with 5% of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), but

Actb was suitable for 10 or 20% of PRP [

24].

In this study, we have performed a comprehensive analysis of transcript stability of different genes to be used as reference genes in qRT-PCR studies of alpaca oocytes after IVM under different culture conditions. The integrated analysis by RefFinder, combining the ∆Ct, BestKeeper, NormFinder, and geNorm methods, indicated that Rplp0 and Gapdh were the most stable gene and Actb the least stable, although slight variations in individual rankings were observed due to differences in the algorithms used by each method.

Although RNA quantification prior to cDNA synthesis was not possible in this study due to the very low amount of RNA extracted from pools of only 20 oocytes and the limited sensitivity of spectrophotometric methods, this limitation was addressed by using a defined number of oocytes per sample. This approach is supported by previous studies showing that RNA normalization did not significantly affect reference gene expression stability in human oocytes [

24].

The expression stability of

Rplp0, a ribosomal protein associated with phosphatidic acid, has been widely recognized across various species and experimental conditions, particularly in ovarian and reproductive tissues. Different studies have validated its performance as a reference gene under both physiological and stress-induced environments, including follicular development in porcine [

25], diverse reproductive states in mouse models [

26], and cryopreservation of human ovarian tissue [

27]. In addition,

Rplp0 has shown high expression stability in human granulosa cells from both polycystic ovarian patients and healthy women, further supporting its reliability in hormonally responsive ovarian tissues [

28]. Similarly,

Gapdh, fundamental to glycolysis and energy metabolism, has consistently ranked among the most stable reference genes in reproductive contexts. It showed reliable expression in mouse germinal vesicle oocytes [

29] and was identified together with

Rplp0, as one of the most stable genes in human ovarian cortex under different culture conditions [

24]. Its stability was also confirmed during chemically induced oocyte maturation in carp [

30]. In contrast,

Actb showed low stability in our analysis, with three of four algorithms ranking it among the least stable genes, and its use altered the expected expression profiles of the target genes. This aligns with previous studies reporting its poor performance in porcine granulosa cells under different stress condition [

25], mouse uterus during peri-implantation [

26], ovine oocytes before and after IVM [

31] and mouse mature oocytes and embryos [

32]. However, other reports have described it as stable in specific contexts, such as human VG oocytes and cumulus cells [

24], underscoring the need for context-dependent validation.

Regarding the target genes analyzed in this study, we observed that the expression profile of

Bmp15 varied depending on the reference gene used for normalization, which emphasizes the importance of validating stable internal controls for accurate gene expression analysis. Notably,

Bmp15, which encodes BMP15, a key member of the TGFβ superfamily essential for oocyte development and folliculogenesis [

33], showed lower expression in oocytes treated with 10 µM resveratrol compared to the control. In contrast, the 2 µM resveratrol group exhibited higher maturation rates than both the control and 10 µM groups, suggesting that moderate concentrations may support oocyte competence. These observations align with previous reports indicating that low doses of resveratrol improve oocyte quality by enhancing antioxidant defenses, whereas higher concentrations may reduce these benefits or have detrimental effects, as observed in porcine and sheep oocytes, potentially due to oxidative stress or cytotoxicity [

10,

11,

34].

In contrast,

Sirt1, which encodes SIRT1, a key regulator of the oxidative stress response in murine oocytes through the modulation of antioxidant enzymatic pathways [

35], did not show significant differences in mRNA expression among the different treatment groups, regardless of the reference gene used for normalization. While several studies have reported increased

Sirt1 expression under stress conditions such as heat shock, aging or cadmium exposure [

36,

37,

38], others have shown that resveratrol supplementation during IVM can increase SIRT1 protein levels even in non-stressful conditions [

39,

40]. In our study, although a slight increase in

Sirt1 transcript levels was observed in the 2 µM resveratrol group, this difference was not statistically significant.

These results support the use of Rplp0 and Gapdh as stable reference genes for normalization in alpaca oocytes during in vitro maturation. However, their stability should be confirmed when applied to other experimental conditions.

5. Conclusions

This study evaluated the expression stability of four candidate reference genes in alpaca oocytes matured in vitro under different culture conditions. Based on a comprehensive analysis using RefFinder, Rplp0 and Gapdh were identified as the most stable genes. Their combined use is recommended to ensure accurate normalization of gene expression data in this model.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess reference gene stability and to investigate gene expression in alpaca oocytes. These findings contribute essential baseline information for molecular studies in this species and underscore the importance of validating internal controls under specific experimental conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Gel electrophoresis of RT-PCR products for the reference and target genes; File S1: Amplification efficiency and melting curve analysis of candidate reference and target genes; Table S1: Ct values of candidate reference genes and target genes in in vitro matured oocytes exposed to resveratrol; Figure S2: Relative expression of

Bmp15 and

Sirt1 using alternative reference genes not selected as the most stable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Q. and M.V.; methodology, J.Q., M.P. and L.A.; formal analysis, J.Q., A.G.M.C., and L.A.; investigation, G.L., B.R., and M.P.; data curation, J.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Q.; writing—review and editing, L.A., A.G.M.C., and M.V.; funding acquisition, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by PROCIENCIA Contract PE501087946-2024 and by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica (CONCYTEC) and the Programa Nacional de Investigación Científica y Estudios Avanzados (PROCIENCIA) within the framework of the E077-2023-01-BM “Becas en Programas de Doctorado en Alianzas Interinstucionales” contest, grant number (PE501085130-2023) and the E033-2023-01-BM “Alianzas Interinstitucionales para Programas de Doctorado” contest grant number (PE501090656-2024).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures were carried out at the Laboratory of Reproductive Phys-iology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Biolog-ical Sciences, UNMSM (approval code: N° 106-2024-CBE-FCB-UNMSM, October 2, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

MV acknowledges funding from PROCIENCIA under Contract PE501087946-2024. The authors gratefully thank Zeze Bravo for his valuable guidance and Héctor Zeña for his assistance during the oocyte collection process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Quina, E. Inseminación artificial de alpacas en un contexto de crianza campesina; Descosur: Arequipa, Peru, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, J.S.; Pearson, L.K.; Tibary, A. Infertility and Subfertility in the Female Camelid. In Llama and Alpaca Care: Medicine, Surgery, Reproduction, Nutrition, and Herd Health, 1st ed.; Cebra, C., Anderson, D.E., Tibary, A., Van Saun, R.J., Johnson, L.W., Eds.; W.B. Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2014; pp. 216–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferré, L.B.; Kjelland, M.E.; Strøbech, L.B.; Hyttel, P.; Mermillod, P.; Ross, P.J. Review: Recent advances in bovine in vitro embryo production: Reproductive biotechnology history and methods. Animals 2020, 14, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguila, L.; Treulen, F.; Therrien, J.; Felmer, R.; Valdivia, M.; Smith, L.C. Oocyte Selection for In Vitro Embryo Production in Bovine Species: Noninvasive Approaches for New Challenges of Oocyte Competence. Animals 2020, 10, 2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wani, N.A. In Vitro Embryo Production (IVEP) in Camelids: Present Status and Future Perspectives. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 21, 100471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telfer, E.E.; Sakaguchi, K.; Clarkson, Y.L.; McLaughlin, M. In Vitro Growth of Immature Bovine Follicles and Oocytes. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2019, 32, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukur, H.A.; Aljumaah, R.S.; Swelum, A.; Alowaimer, A.; Saadeldin, I.M. Oocyte Development and Its Regulation. J. Anim. Reprod. Biotechnol. 2020, 35, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, M.; Franciosi, F. Acquisition of Oocyte Competence to Develop as an Embryo: Integrated Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Events. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 24, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sovernigo, T.C.; Adona, P.R.; Monzani, P.S.; Guemra, S.; Barros, F.D.A.; Lopes, F.G.; et al. Effects of Supplementation of Medium with Different Antioxidants during In Vitro Maturation of Bovine Oocytes on Subsequent Embryo Production. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Tian, X.; Zhang, L.; He, C.; Ji, P.; Li, Y.; Tan, D.; Liu, G. Beneficial Effect of Resveratrol on Bovine Oocyte Maturation and Subsequent Embryonic Development after In Vitro Fertilization. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 101, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, S.S.; Cheong, S.A.; Jeon, Y.; Lee, E.; Choi, K.C.; Jeung, E.B.; et al. The Effects of Resveratrol on Porcine Oocyte In Vitro Maturation and Subsequent Embryonic Development after Parthenogenetic Activation and In Vitro Fertilization. Theriogenology 2012, 78, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, X.; Liang, X.; Xu, H.; Liao, Y.; Lu, K.; et al. Effects of Resveratrol on In Vitro Maturation of Porcine Oocytes and Subsequent Early Embryonic Development Following Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2019, 54, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanGuilder, H.D.; Vrana, K.E.; Freeman, W.M. Twenty-Five Years of Quantitative PCR for Gene Expression Analysis. Biotechniques. 2008, 44, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bär, M.; Bär, D.; Lehmann, B. Selection and Validation of Candidate Housekeeping Genes for Studies of Human Keratinocytes—Review and Recommendations. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2009, 129, 535–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi, M.; Ashry, M.; Salama, A.; Badr, M.R. Developmental Competence of Dromedary Camel (Camelus dromedarius) Oocytes Selected Using Brilliant Cresyl Blue Staining. Zygote 2017, 25, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Q.; Cui, M.; Li, Q.; Mu, S.; Zhao, Z. Effect of Melatonin on the In Vitro Maturation of Porcine Oocytes, Development of Parthenogenetically Activated Embryos, and Expression of Genes Related to the Oocyte Developmental Capability. Animals 2020, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azari, M.; Kafi, M.; Ebrahimi, B.; Fatehi, R.; Jamalzadeh, M. Oocyte Maturation, Embryo Development and Gene Expression Following Two Different Methods of Bovine Cumulus-Oocyte Complexes Vitrification. Vet. Res. Commun. 2017, 41, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radonić, A.; Thulke, S.; Mackay, I.M.; Landt, O.; Siegert, W.; Nitsche, A. Guideline to Reference Gene Selection for Quantitative Real-Time PCR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 313, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaffl, M.W. A New Mathematical Model for Relative Quantification in Real-Time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, E45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Zakrajsek, B.A. Effect of experimental treatment on housekeeping gene expression: Validation by real-time, quantitative RT-PCR. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2000, 46, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thellin, O.; Zorzi, W.; Lakaye, B.; De, B. Housekeeping genes as internal standards: Use and. J Biotechnol. 1999, 75, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestorov, J.; Matić, G.; Elaković, I.; Tanić, N. Gene expression studies: How to obtain accurate and reliable data by quantitative real-time RT PCR. J. Med. Biochem. 2013, 32, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheda, K.; Huggett, J.F.; Chang, J.S.; Kim, L.U.; Bustin, S.A.; Johnson, M.A.; et al. The implications of using an inappropriate reference gene for real-time reverse transcription PCR data normalization. Anal. Biochem. 2005, 344, 141–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadenas, J.; Pors, S.E.; Nikiforov, D.; Zheng, M.; Subiran, C.; Bøtkjær, J.A.; et al. Validating reference gene expression stability in human ovarian follicles, oocytes, cumulus cells, ovarian medulla, and ovarian cortex tissue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, C.; Pan, Z.; Li, Q.; Du, X. From stability to reliability: Unveiling the un-biased reference genes in porcine ovarian granulosa cells under different conditions. Gene 2024, 897, 148089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, P.F.; Lan, X.L.; Chen, F.L.; Yang, Y.Z.; Jin, Y.P.; Wang, A.H. Reference gene selection for real-time quantitative PCR analysis of the mouse uterus in the peri-implantation period. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e62462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikishin, D.A.; Filatov, M.A.; Kiseleva, M.V.; Bagaeva, T.S.; Konduktorova, V.V.; Khramova, Y.V.; et al. Selection of stable expressed reference genes in native and vitrified/thawed human ovarian tissue for analysis by qRT-PCR and Western blot. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, Y.; Zhao, S.G.; Lu, G.; Leung, C.K.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Su, X.W.; et al. Identification of reference genes for qRT-PCR in granulosa cells of healthy women and polycystic ovarian syndrome patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filatov, M.A.; Nikishin, D.A.; Khramova, Y.V.; Semenova, M.L. Reference genes selection for real-time quantitative PCR analysis in mouse germinal vesicle oocytes. Zygote 2019, 27, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S. Reference gene validation for quantification of gene expression during final oocyte maturation induced by diethylstilbestrol and di-(2-ethylhexyl)-phthalate in common carp. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 46, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, T.; Wilmut, I.; Taylor, J. Quantitative evaluation of reference genes for real-time PCR during in vitro maturation of ovine oocytes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2013, 48, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamo, S.; Gal, A.B.; Bodo, S.; Dinnyes, A. Quantitative evaluation and selection of reference genes in mouse oocytes and embryos cultured in vivo and in vitro. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paulini, F.; Melo, E.O. The role of oocyte-secreted factors GDF9 and BMP15 in follicular development and oogenesis. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2011, 46, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabihi, A.; Shabankareh, H.K.; Hajarian, H.; Foroutanifar, S. Resveratrol addition to in vitro maturation and in vitro culture media enhances developmental competence of sheep embryos. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2019, 68, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 35 Di Emidio, G.; Falone, S.; Vitti, M.; D’Alessandro, A.M.; Vento, M.; Di Pietro, C.; Amicarelli, F.; Tatone, C. SIRT1 signalling protects mouse oocytes against oxidative stress and is deregulated during aging. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 29, 2006–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, J.; He, C.; Wang, F.; et al. Resveratrol compares with melatonin in improving in vitro porcine oocyte maturation under heat stress. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.J.; Sun, A.G.; Zhao, S.G.; Liu, H.; Ma, S.Y.; Li, M.; et al. Resveratrol improves in vitro maturation of oocytes in aged mice and humans. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 109, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piras, A.R.; Ariu, F.; Maltana, A.; Leoni, G.G.; Martino, N.A.; Mastrorocco, A.; et al. Protective effect of resveratrol against cadmium-induced toxicity on ovine oocyte in vitro maturation and fertilization. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeo, S.; Sato, D.; Kimura, K.; Monji, Y.; Kuwayama, T.; Kawahara-Miki, R.; et al. Resveratrol improves the mitochondrial function and fertilization outcome of bovine oocytes. J. Reprod. Dev. 2014, 60, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itami, N.; Shirasuna, K.; Kuwayama, T.; Iwata, H. Resveratrol improves the quality of pig oocytes derived from early antral follicles through sirtuin 1 activation. Theriogenology 2015, 83, 1360–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).