Submitted:

20 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Protein Extraction from Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina)

2.2.1. Conventional Chemical Extraction Method

2.2.2. High Pressure Homogenization (HPH) Extraction

2.3. Optical Microscopy

2.4. Protein Content and Extraction Efficiency

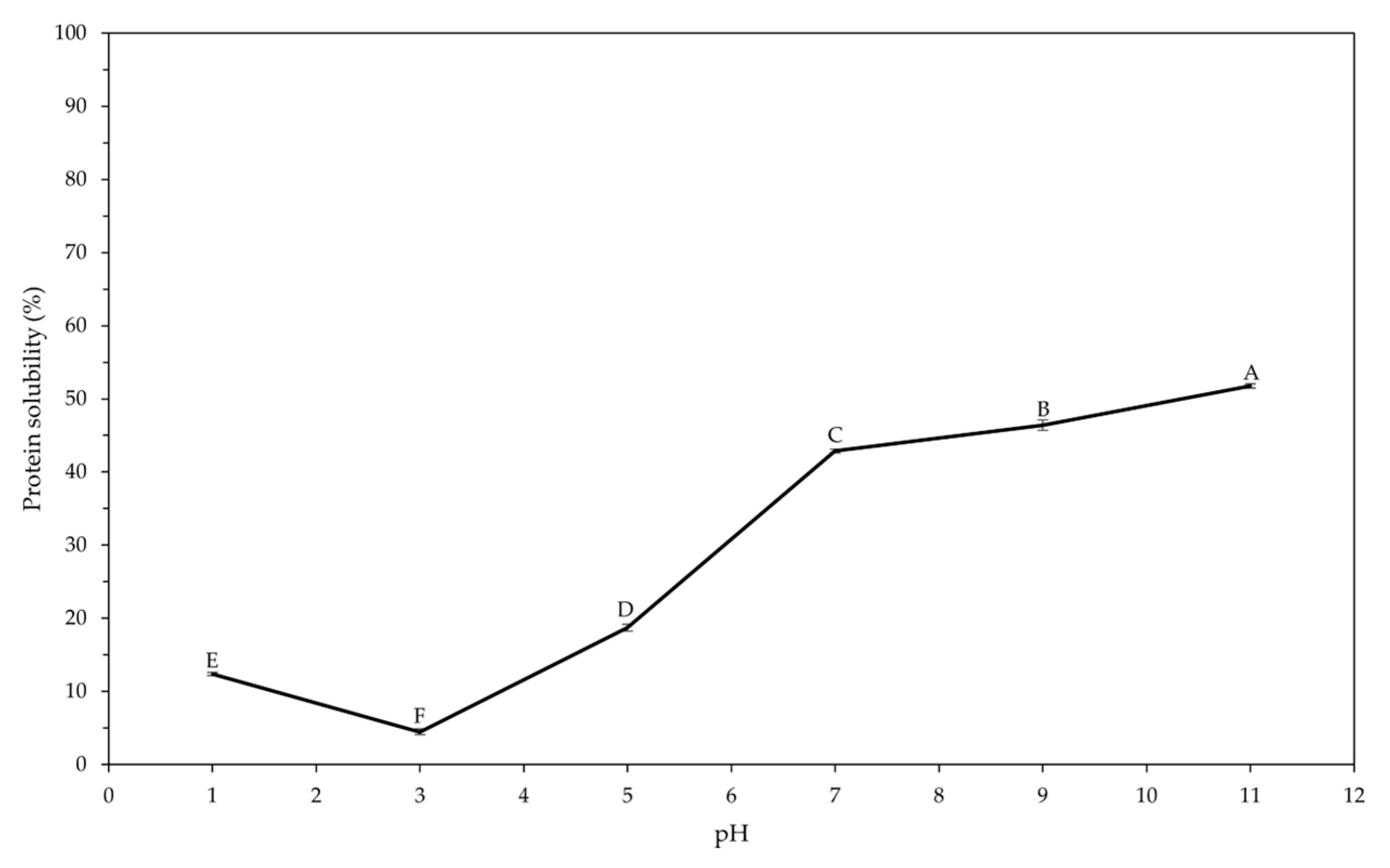

2.5. Determination of Protein Solubility

2.6. Phycobiliprotein Determination in the Soluble Fraction

2.7. Emulsifying Properties

2.8. Differential Scanning Calorimetry for Thermal Analysis of Spirulina Protein Extracts

2.9. Rheological Measurements

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

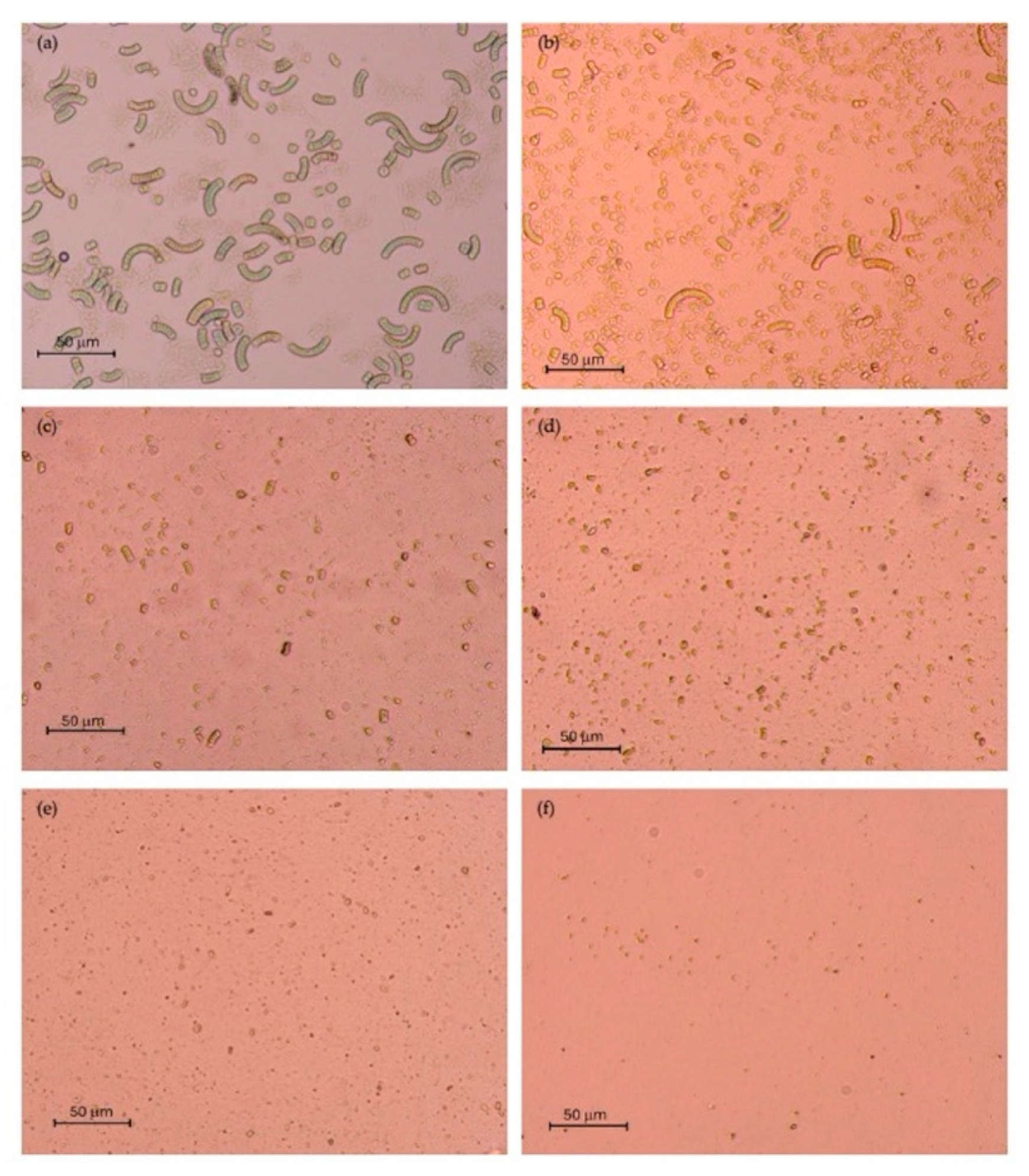

3.1. Impact of Chemical and HPH on the Cellular Microstructure of Spirulina Suspensions

3.2. Protein Extraction Efficiency

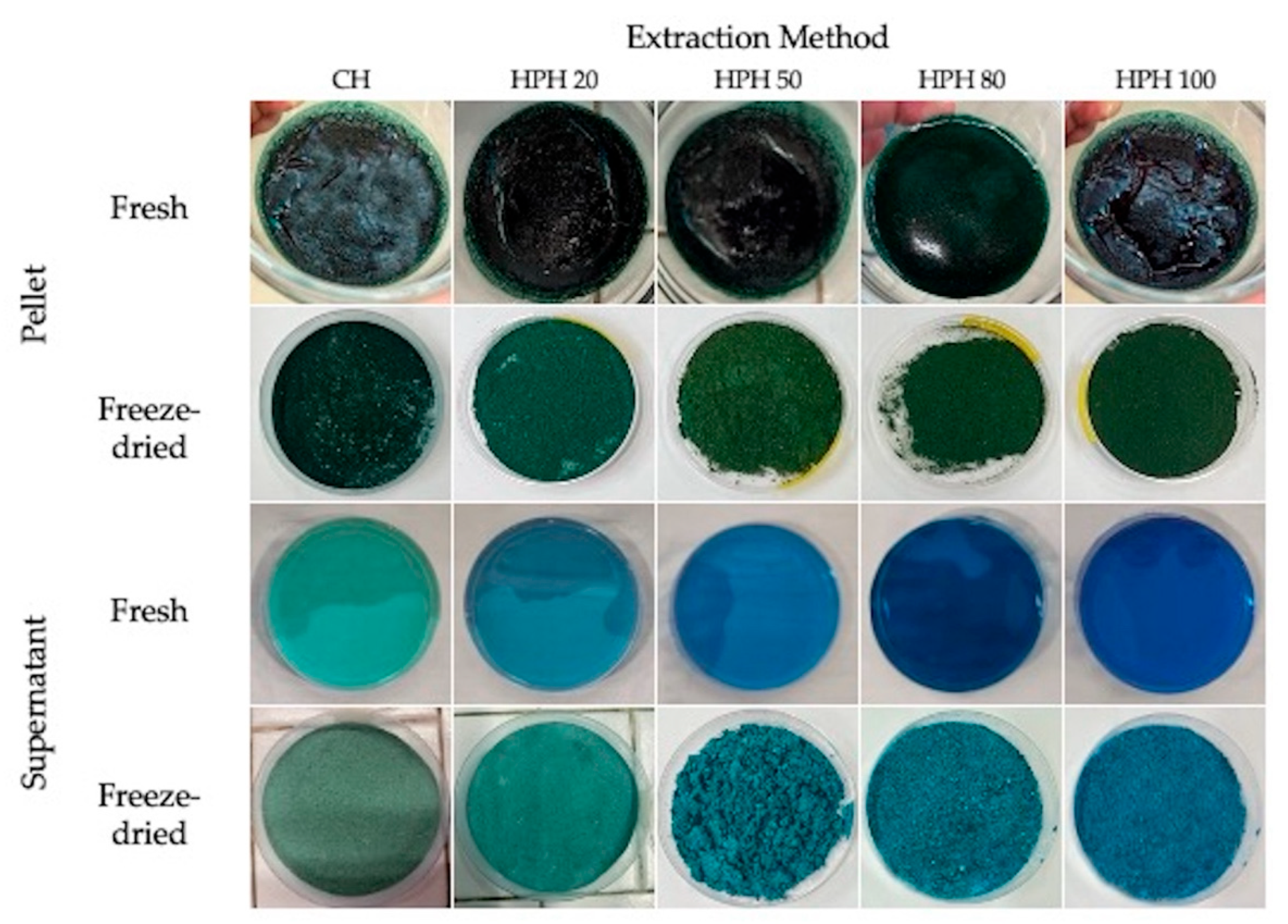

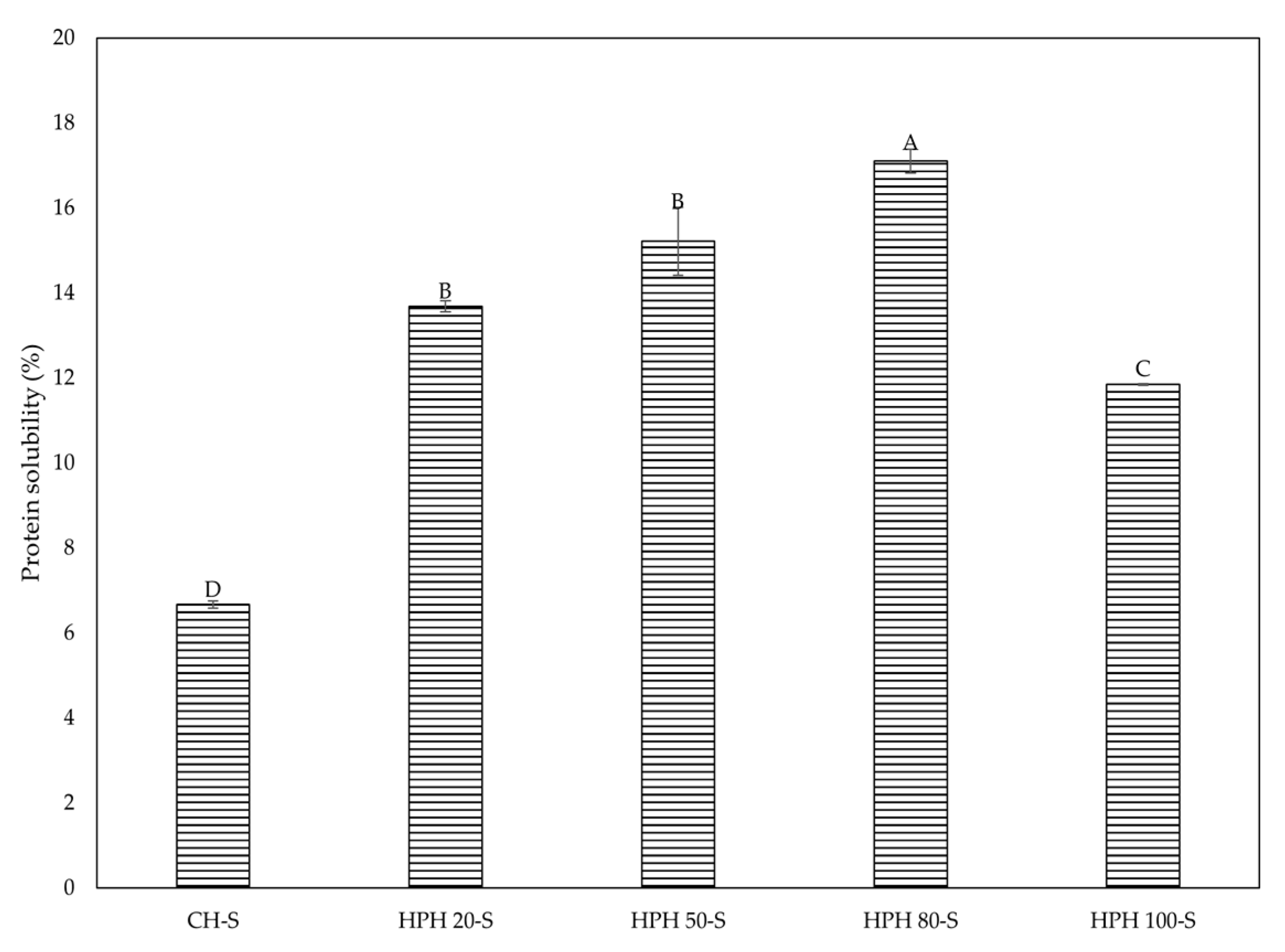

3.3. Protein Characterization of Fractions Obtained by HPH and CH Methods

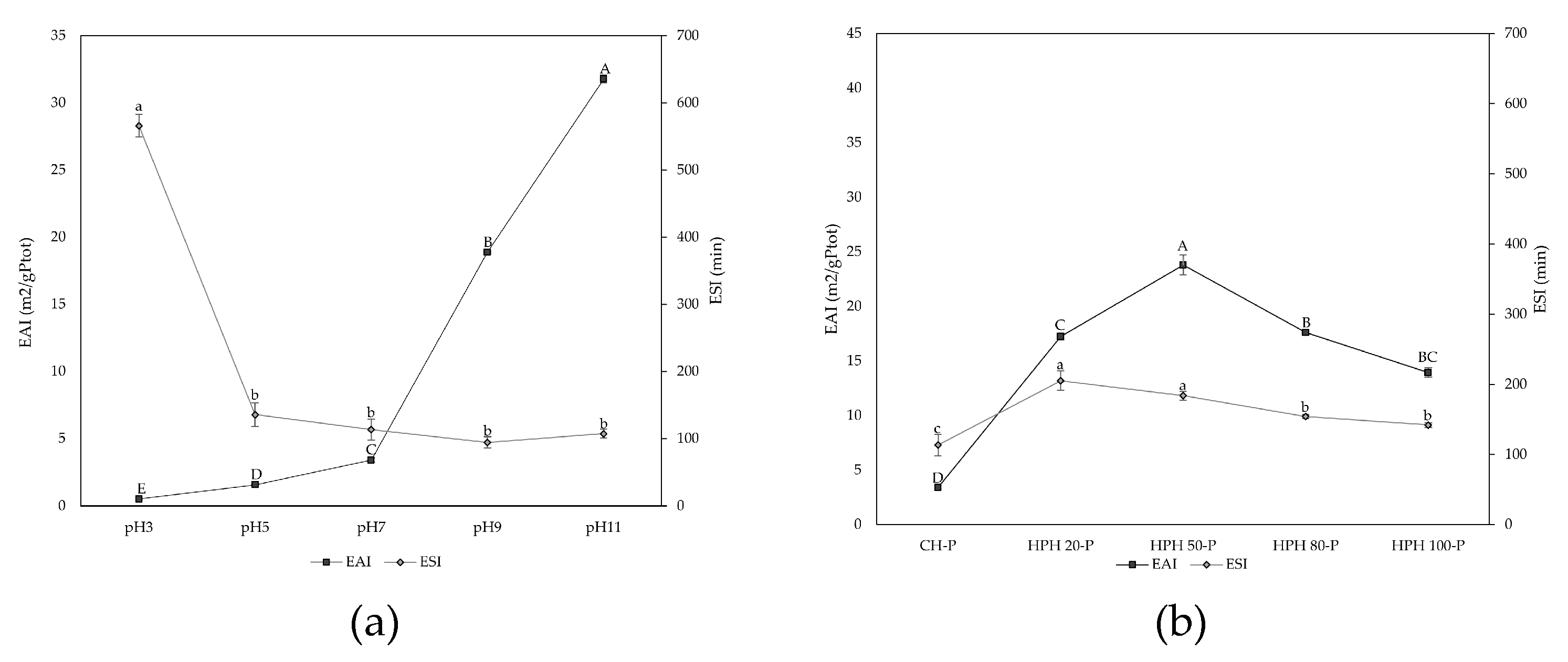

3.4. Water Holding Capacity, Emulsifying and Foaming Properties

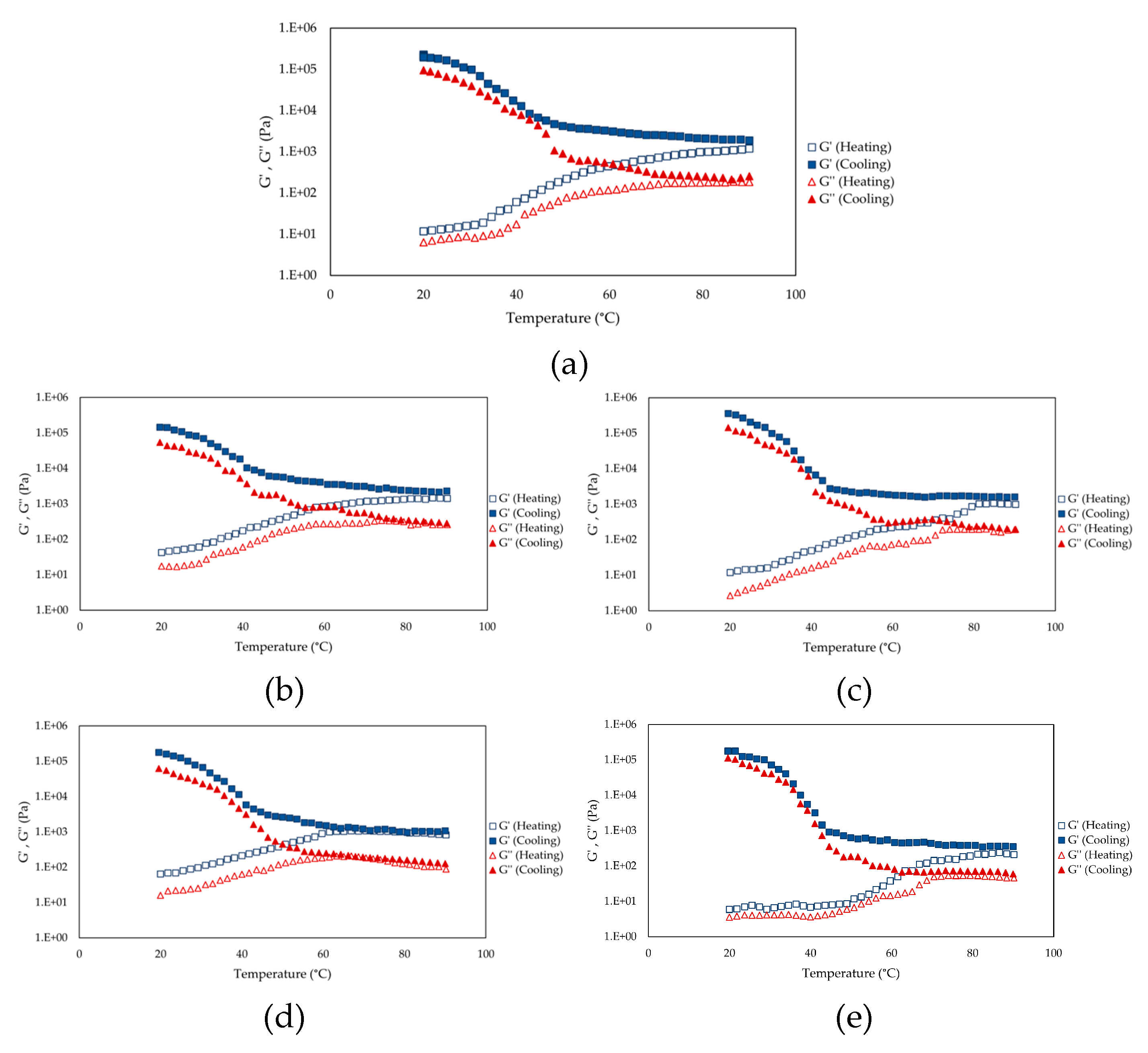

3.5. Thermal Stability and Denaturation Behaviour of Spirulina Extracts

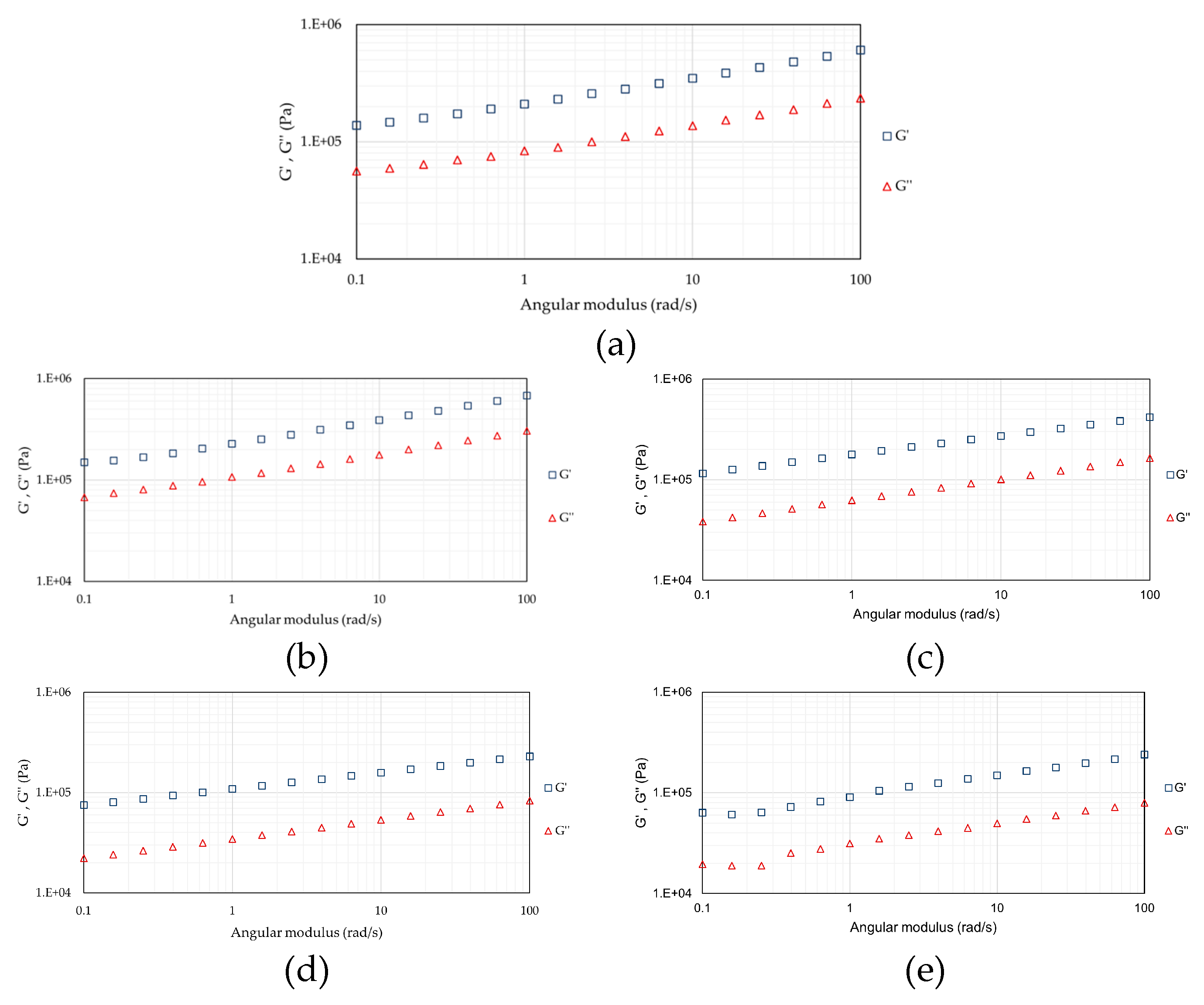

3.6. Rheological Properties of Spirulina Protein Extracts: Flow and Viscoelastic Properties

| Sample | Loss Factor - |

|---|---|

| CH-P | 0.40±0.01AB |

| HPH 20-P | 0.45±0.03A |

| HPH 50-P | 0.38±0.02AB |

| HPH 80-P | 0.38±0.05BC |

| HPH 100-P | 0.33±0.04C |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Henchion, M.; Hayes, M.; Mullen, A.; Fenelon, M.; Tiwari, B. Future Protein Supply and Demand: Strategies and Factors Influencing a Sustainable Equilibrium. Foods 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritala, A.; Häkkinen, S. T.; Toivari, M.; Wiebe, M. G. Single Cell Protein—State-of-the-Art, Industrial Landscape and Patents 2001–2016. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ashraf, S. S. Sustainable Food and Feed Sources from Microalgae: Food Security and the Circular Bioeconomy. Algal Research 2023, 74, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfray, H. C. J.; Aveyard, P.; Garnett, T.; Hall, J. W.; Key, T. J.; Lorimer, J.; Pierrehumbert, R. T.; Scarborough, P.; Springmann, M.; Jebb, S. A. Meat Consumption, Health, and the Environment. Science 2018, 361, eaam5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F. N.; Leip, A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nat Food 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. (2020). A Farm to Fork Strategy for a fair, healthy and environmentally-friendly food system. COM(2020) 381 final. Bruxelles, 20 maggio 2020.

- Stagnari, F.; Maggio, A.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Multiple Benefits of Legumes for Agriculture Sustainability: An Overview. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, P.; Gururani, P.; Singh, N.; Gautam, P.; Vlaskin, M. S.; Kumar, V. Review on Microalgae Protein and Its Current and Future Utilisation in the Food Industry. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2024, 59, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Rodrigues, M. M.; Estrada-Beristain, C.; Metri-Ojeda, J.; Pérez-Alva, A.; Baigts-Allende, D. K. Spirulina Platensis Protein as Sustainable Ingredient for Nutritional Food Products Development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Käferböck, A.; Smetana, S.; De Vos, R.; Schwarz, C.; Toepfl, S.; Parniakov, O. Sustainable Extraction of Valuable Components from Spirulina Assisted by Pulsed Electric Fields Technology. Algal Research 2020, 48, 101914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İlter, I.; Akyıl, S.; Demirel, Z.; Koç, M.; Conk-Dalay, M.; Kaymak-Ertekin, F. Optimization of Phycocyanin Extraction from Spirulina Platensis Using Different Techniques. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2018, 70, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente, F.; Pereira, P. C. Pork Meat Composition and Health: A Review of the Evidence. Foods 2024, 13, 1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, F.; Corsello, G.; Cricelli, C.; Ferrara, N.; Ghiselli, A.; Lucchin, L.; Poli, A. Role of Poultry Meat in a Balanced Diet Aimed at Maintaining Health and Wellbeing: An Italian Consensus Document. Food & Nutrition Research 2015, 59, 27606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroșan, E.; Lupu, C.; Mititelu, M.; Musuc, A.; Rusu, A.; Răducan, I.; Karampelas, O.; Voinicu, I.; Neacșu, S.; Licu, M.; Pogan, A.; Cîrnațu, D.; Ilie, E.; Dărăban, A. Evaluation of the Nutritional Quality of Different Soybean and Pea Varieties: Their Use in Balanced Diets for Different Pathologies. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hailemariam, A.; Esatu, W.; Abegaz, S.; Urge, M.; Assefa, G.; Dessie, T. Nutritional Composition and Sensory Characteristics of Breast Meat from Different Chickens. Applied Food Research 2022, 2, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Kumar, V. Effect of High-Pressure Treatment on Oscillatory Rheology, Particle Size Distribution and Microstructure of Microalgae Chlorella Vulgaris and Arthrospira Platensis. Algal Research 2022, 62, 102617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, M.; Soltanzadeh, M.; Ebrahimi, A. R.; Hamishehkar, H. Spirulina Platensis Protein Hydrolysates: Techno-Functional, Nutritional and Antioxidant Properties. Algal Research 2022, 65, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan-utai, W.; Iamtham, S. Extraction, Purification and Antioxidant Activity of Phycobiliprotein from Arthrospira Platensis. Process Biochemistry 2019, 82, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yu, X.; Cui, Y.; Xu, L.; Huo, S.; Ding, Z.; Hu, Q.; Xie, W.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, D. Efficient Extraction of Phycobiliproteins from Dry Biomass of Spirulina Platensis Using Sodium Chloride as Extraction Enhancer. Food Chemistry 2023, 406, 135005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannoglou, M.; Andreou, V.; Thanou, I.; Markou, G.; Katsaros, G. Kinetic Study of the Combined Effect of High Pressure and pH-Value on Arthrospira Platensis (Spirulina) Proteins Extraction. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2023, 85, 103331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purdi, T. S.; Setiowati, A. D.; Ningrum, A. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Spirulina Platensis Protein: Physicochemical Characteristic and Techno-Functional Properties. Food Measure 2023, 17, 5474–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessio, G.; Flamminii, F.; Faieta, M.; Prete, R.; Di Michele, A.; Pittia, P.; Di Mattia, C. D. High Pressure Homogenization to Boost the Technological Functionality of Native Pea Proteins. Current Research in Food Science 2023, 6, 100499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magpusao, J.; Giteru, S.; Oey, I.; Kebede, B. Effect of High Pressure Homogenization on Microstructural and Rheological Properties of A. Platensis, Isochrysis, Nannochloropsis and Tetraselmis Species. Algal Research 2021, 56, 102327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkolnikov Lozober, H.; Okun, Z.; Shpigelman, A. The Impact of High-Pressure Homogenization on Thermal Gelation of Arthrospira Platensis (Spirulina) Protein Concentrate. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2021, 74, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, S. C.; Almeida, T.; Colucci, G.; Santamaria-Echart, A.; Manrique, Y. A.; Dias, M. M.; Barros, L.; Fernandes, Â.; Colla, E.; Barreiro, M. F. Spirulina (Arthrospira Platensis) Protein-Rich Extract as a Natural Emulsifier for Oil-in-Water Emulsions: Optimization through a Sequential Experimental Design Strategy. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2022, 648, 129264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International 2019. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International (21st ed.). AOAC International, Rockville, MD, Method 981.10.

- Zhang, Z.; Holden, G.; Wang, B.; Adhikari, B. Maillard Reaction-Based Conjugation of Spirulina Protein with Maltodextrin Using Wet-Heating Route and Characterisation of Conjugates. Food Chem. 2023, 406, 134931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Nunes, R.; De Biasio, F.; Spigno, G.; Gorgoglione, D.; Teixeira, J. A.; Rocha, C. M. R. Influence of Thermal and Electrical Effects of Ohmic Heating on C-Phycocyanin Properties and Biocompounds Recovery from Spirulina Platensis. Lebenson. Wiss. Technol. 2020, 128(109491), 109491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faieta, M.; Corradini, M. G.; Di Michele, A.; Ludescher, R. D.; Pittia, P. Effect of Encapsulation Process on Technological Functionality and Stability of Spirulina Platensis Extract. Food Biophysics 2020, 15, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muccio, E.; Lanza, R. F.; Malvano, F.; Marra, F.; Albanese, D. Impact of High-Pressure Homogenization on the Technological Properties of A. Platensis (Spirulina) Proteins for Food Applications. Chem. Eng. Trans, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Chang, C.; Chen, J.; Cao, F.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y.; Zhu, J. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Proteins Extracted from Three Microalgal Species. Food Hydrocolloids 2019, 96, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, S.; Hayes, M. Functional and Bioactive Properties of Protein Extracts Generated from Spirulina Platensis and Isochrysis Galbana T-Iso. Applied Sciences 2021, 11, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, C.; Ursu, A. V.; Laroche, C.; Zebib, B.; Merah, O.; Pontalier, P.-Y.; Vaca-Garcia, C. Aqueous Extraction of Proteins from Microalgae: Effect of Different Cell Disruption Methods. Algal Research 2014, 3, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernaerts, T. M. M.; Panozzo, A.; Doumen, V.; Foubert, I.; Gheysen, L.; Goiris, K.; Moldenaers, P.; Hendrickx, M. E.; Van Loey, A. M. Microalgal Biomass as a (Multi)Functional Ingredient in Food Products: Rheological Properties of Microalgal Suspensions as Affected by Mechanical and Thermal Processing. Algal Research 2017, 25, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elain, A.; Nkounkou, C.; Le Fellic, M.; Donnart, K. Green Extraction of Polysaccharides from Arthrospira Platensis Using High Pressure Homogenization. J Appl Phycol 2020, 32, 1719–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelhadj, S.; Douiri, S.; Ghouilli, A.; Hassen, R. B.; Keshk, S. M. A. S.; El-kott, A.; Attia, H.; Ghorbel, D. Extraction of Arthrospira Platensis (Spirulina) Proteins via Osborne Sequential Procedure: Structural and Functional Characterizations. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2023, 115, 104984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böcker, L.; Bertsch, P.; Wenner, D.; Teixeira, S.; Bergfreund, J.; Eder, S.; Fischer, P.; Mathys, A. Effect of Arthrospira Platensis Microalgae Protein Purification on Emulsification Mechanism and Efficiency. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 584, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benelhadj, S.; Gharsallaoui, A.; Degraeve, P.; Attia, H.; Ghorbel, D. Effect of pH on the Functional Properties of Arthrospira (Spirulina) Platensis Protein Isolate. Food Chemistry 2016, 194, 1056–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupatini Menegotto, A. L.; Souza, L. E. S. D.; Colla, L. M.; Costa, J. A. V.; Sehn, E.; Bittencourt, P. R. S.; Moraes Flores, É. L. D.; Canan, C.; Colla, E. Investigation of Techno-Functional and Physicochemical Properties of Spirulina Platensis Protein Concentrate for Food Enrichment. LWT 2019, 114, 108267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zhu, D.; Hu, S.; Kang, Z.; Ma, H. Effect of Dynamic Ultra-High Pressure Homogenization on the Structure and Functional Properties of Whey Protein. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 57, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, J.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Guo, X. Effects of High-Pressure Homogenization on the Physicochemical, Foaming, and Emulsifying Properties of Chickpea Protein. Food Research International 2023, 170, 112986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pez Jaeschke, D.; Rocha Teixeira, I.; Damasceno Ferreira Marczak, L.; Domeneghini Mercali, G. Phycocyanin from Spirulina: A Review of Extraction Methods and Stability. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. G.; Baral, K. C.; Kim, G.-L.; Park, J.-W.; Seo, S.-H.; Kim, D.-H.; Jung, D. H.; Ifekpolugo, N. L.; Han, H.-K. Quantitative Analysis of Therapeutic Proteins in Biological Fluids: Recent Advancement in Analytical Techniques. Drug Delivery 2023, 30, 2183816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rekowski, A.; Langenkämper, G.; Dier, M.; Wimmer, M. A.; Scherf, K. A.; Zörb, C. Determination of Soluble Wheat Protein Fractions Using the Bradford Assay. Cereal Chem 2021, 98, 1059–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Baky, N. A.; Rezk, N. M. F.; Amara, A. A. Arthrospira Platensis Variants: A Comparative Study Based on C-Phycocyanin Gene and Protein, Habitat, and Growth Conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, R.; Campos, J.; Serra, M.; Fidalgo, J.; Almeida, H.; Casas, A.; Toubarro, D.; Barros, A. I. R. N. A. Exploring the Benefits of Phycocyanin: From Spirulina Cultivation to Its Widespread Applications. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katsimichas, A.; Limnaios, A.; Dimitrakopoulos, K.; Dimopoulos, G.; Taoukis, P. Pulsed Electric Fields Assisted Extraction of Proteins and Phycocyanin from Arthrospira Platensis Biomass: A Kinetic Study. Food Bioprod. Process. 2024, 147, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovaleski, G.; Kholany, M.; Dias, L. M. S.; Correia, S. F. H.; Ferreira, R. A. S.; Coutinho, J. A. P.; Ventura, S. P. M. Extraction and Purification of Phycobiliproteins from Algae and Their Applications. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 1065355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratelli, C.; Bürck, M.; Silva-Neto, A. F.; Oyama, L. M.; De Rosso, V. V.; Braga, A. R. C. Green Extraction Process of Food Grade C-Phycocyanin: Biological Effects and Metabolic Study in Mice. Processes (Basel) 2022, 10, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, T.; Ma, L.; Song, F. High-Pressure Homogenization Treatment on Yeast Protein: Effect on Structure and Emulsifying Properties. Food Research International 2025, 213, 116550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Q.; Gong, Z.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X. Effects of Molecular Structure and Charge State on the Foaming and Emulsifying Properties of Spirulina Protein Isolates. Food Research International 2024, 187, 114407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, S. Functional Properties and Structural Characteristics of Phosphorylated Pea Protein Isolate. Int J of Food Sci Tech 2020, 55, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Y.; Shi, X.; Wu, F.; Zou, H.; Chang, C.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, M.; Yu, C. Improving the Stability of Oil-in-Water Emulsions by Using Mussel Myofibrillar Proteins and Lecithin as Emulsifiers and High-Pressure Homogenization. J. Food Eng. 2019, 258, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Hag, L. V. ’T; Haritos, V.; Dhital, S. Rheological and Textural Properties of Heat-Induced Gels from Pulse Protein Isolates: Lentil, Mungbean and Yellow Pea. Food Hydrocolloids 2023, 143, 108904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelany, M.; Yemiş, O. Improving the Functional Performance of Date Seed Protein Concentrate by High-Intensity Ultrasonic Treatment. Molecules 2022, 28, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antecka, A.; Szeląg, R.; Ledakowicz, S. A Novel Two-Step Purification Process for Highly Stable C-Phycocyanin of Analytical Grade Purity and Its Properties. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2025, 109, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.; Pawar, R.; Mishra, S.; Sonawane, S.; Ghosh, P.K. Kinetic studies on thermal denaturation of C-phycocyanin. Indian J Biochem Biophys. 2004, 41(5):254-7.

- Liang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Cheng, T.; Zhou, L.; Guo, Z. Effects of High-Pressure Homogenization on Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Enzymatic Hydrolyzed Soybean Protein Concentrate. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1054326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, L.; Umiltà, E.; Righetti, M. C.; Messina, T.; Zurlini, C.; Montanari, A.; Bronco, S.; Bertoldo, M. On the Thermal Behavior of Protein Isolated from Different Legumes Investigated by DSC and TGA. J Sci Food Agric 2018, 98, 5368–5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanger, C.; Müller, M.; Andlinger, D.; Kulozik, U. Influence of pH and Ionic Strength on the Thermal Gelation Behaviour of Pea Protein. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 123, 106903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmann, L.; Hinrichs, J.; Goff, H. D.; Weiss, J. Heat-Induced Gel Formation of a Protein-Rich Extract from the Microalga Chlorella Sorokiniana. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2019, 56, 102176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munialo, C. D.; Euston, S. R.; De Jongh, H. H. J. Protein Gels. Proteins in Food Processing; Elsevier, 2018; pp 501–521. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, M.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; Mijlkovic, A.; Krona, A.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Coll-Marqués, J. M.; López-Rubio, A.; Lopez-Sanchez, P. Composition and Rheological Properties of Microalgae Suspensions: Impact of Ultrasound Processing. Algal Research 2020, 49, 101960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X. D.; Arntfield, S. D. Gelation Properties of Salt-Extracted Pea Protein Induced by Heat Treatment. Food Research International 2010, 43, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Extraction method | Pressure (MPa) | Precipitate fraction (-P) | Supernatant fraction (-S) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical (CH) | CH-P | CH-S | |

| - | |||

| High-Pressure Homogenization (HPH) | 20 | HPH 20-P | HPH 20-S |

| 50 | HPH 50-P | HPH 50-S | |

| 80 | HPH 80-P | HPH 80-S | |

| 100 | HPH 100-P | HPH 100-S |

| Method |

Total protein extraction yield gPtot/100gPSB |

Pellet | Supernatant | ||

|

Protein content gPtot/100g-P |

Protein yield* gPtot/100gPSB |

Protein content gPtot/100g-P |

Protein yield* gPtot/100gPSB |

||

| CH | 56.58±0.40C | 77.32±0.43A | 31.21±0.83D | 21.14±1.32D | 8.03±0.16C |

| HPH 20 | 60.53±1.43C | 67.87±0.40B | 55.82±1.24C | 30.03±0.28C | 4.71±0.19D |

| HPH 50 | 72.35±1.15B | 69.00±0.18B | 68.02±0.92A | 30.54±0.46C | 4.34±0.24D |

| HPH 80 | 73.62±1.51AB | 58.96±0.11C | 63.32±1.20B | 38.07±0.94B | 10.30±0.31B |

| HPH 100 | 77.79±0.74A | 49.06±0.13D | 58.42±0.30C | 50.06±0.84A | 19.49±0.73A |

| Sample | PBPs gPBP/100gPtot-S |

C-PC gC-PC/100gPtot-S |

A-PC gAPC/100gPtot-S |

PE gPE/100gPtot-S |

EP - |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH | 3.45±0.09E | 2.40±0.03E | 0.36±0.04A | 0.69±0.02A | 0.27±0.10B |

| HPH 20 | 7.07±0.00D | 6.65±0.00D | 0.00±0.00B | 0.04±0.00C | 0.53±0.00B |

| HPH 50 | 10.42±0.00B | 9.61±0.00A | 0.00±0.00B | 0.08±0.00B | 0.91±0.14A |

| HPH 80 | 10.62±0.00A | 9.23±0.00B | 0.07±0.00B | 0.07±0.00BC | 0.96±0.02A |

| HPH 100 | 8.12±0.02C | 7.62±0.02C | 0.00±0.00B | 0.05±0.00BC | 1.04±0.00A |

| Sample | TO °C |

TP °C |

ΔH J/gPtot |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH-P | 48.56 ±0.86B | 51.57 ±0.52B | 2.75 ±0.11B |

| HPH 20-P | 44.49 ±0.71C | 49.37 ±0.00B | 1.17 ±0.30B |

| HPH 50-P | 53.53 ±0.86A | 58.70± 0.56A | 11.96± 0.20A |

| HPH 80-P | 38.54 ±0.40D | 45.50 ±0.42C | 2.61 ±0.70B |

| HPH 100-P | 47.22 ±0.85BC | 50.42 ±1.24B | 8.79 ±1.61A |

| CH-S | 41.80 ±0.59C | 41.19 ±0.02B | 19.27 ±0.10A |

| HPH 20-S | 47.81 ±0.97AB | 50.18±1.56A | 4.22 ±1.31B |

| HPH 50-S | 46.10 ±0.28B | 47.63 ±0.05A | 5.36 ±1.16B |

| HPH 80-S | 48.64 ±0.54A | 50.14 ±0.48A | 5.11 ±0.46B |

| HPH 100-S | 39.85 ±0.21C | 47.72 ±0.11A | 8.53 ±1.89B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).