Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

27 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

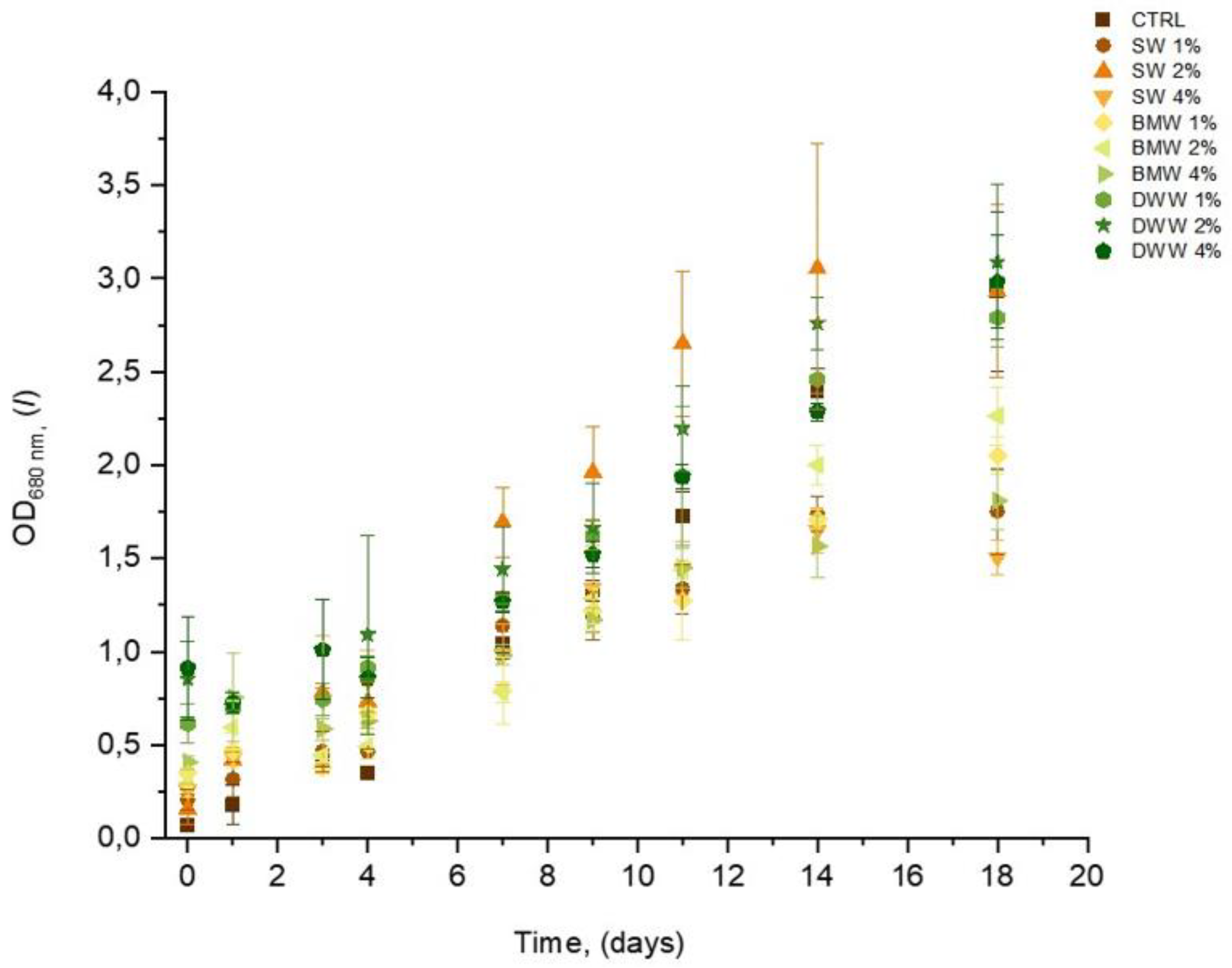

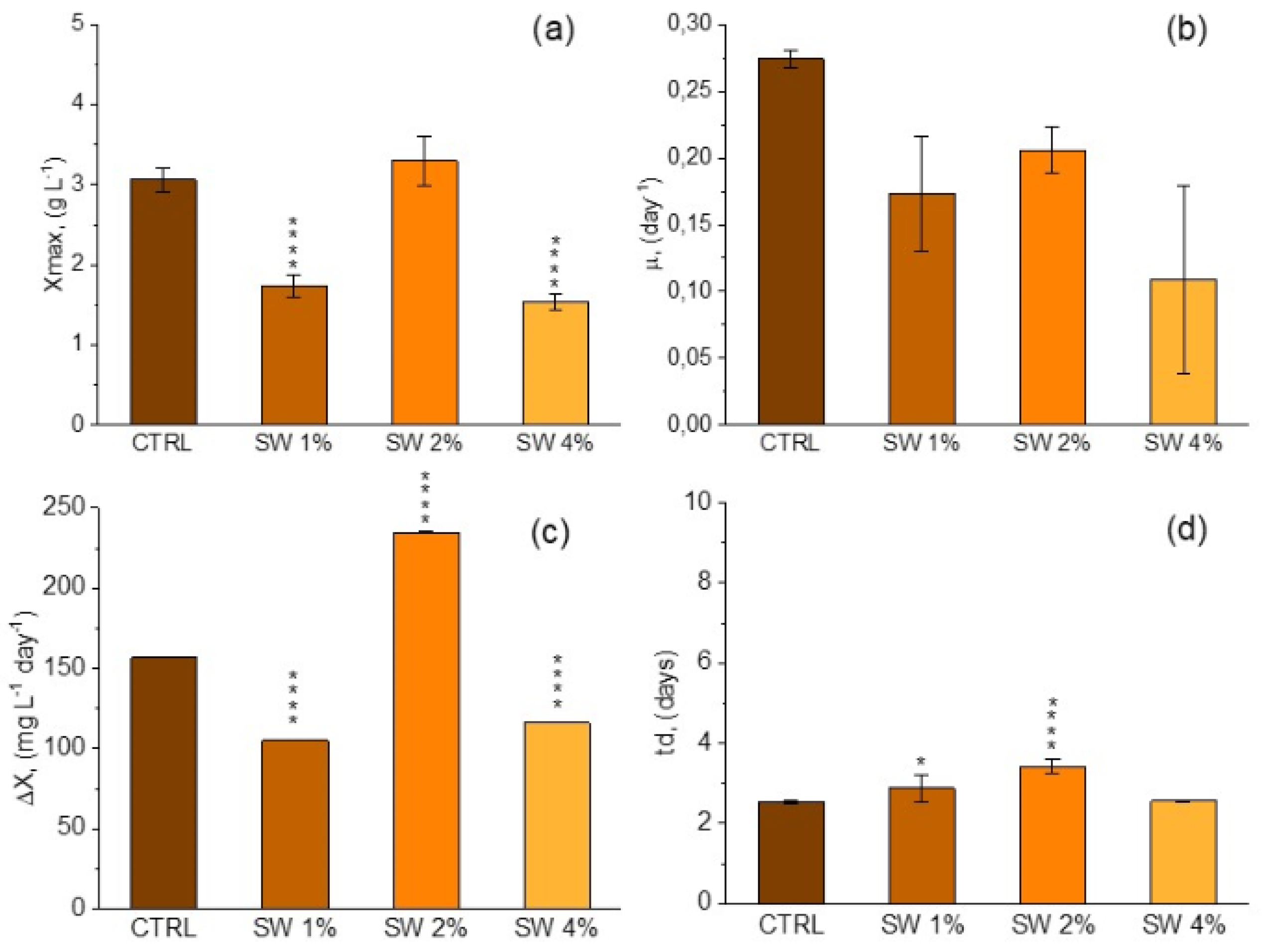

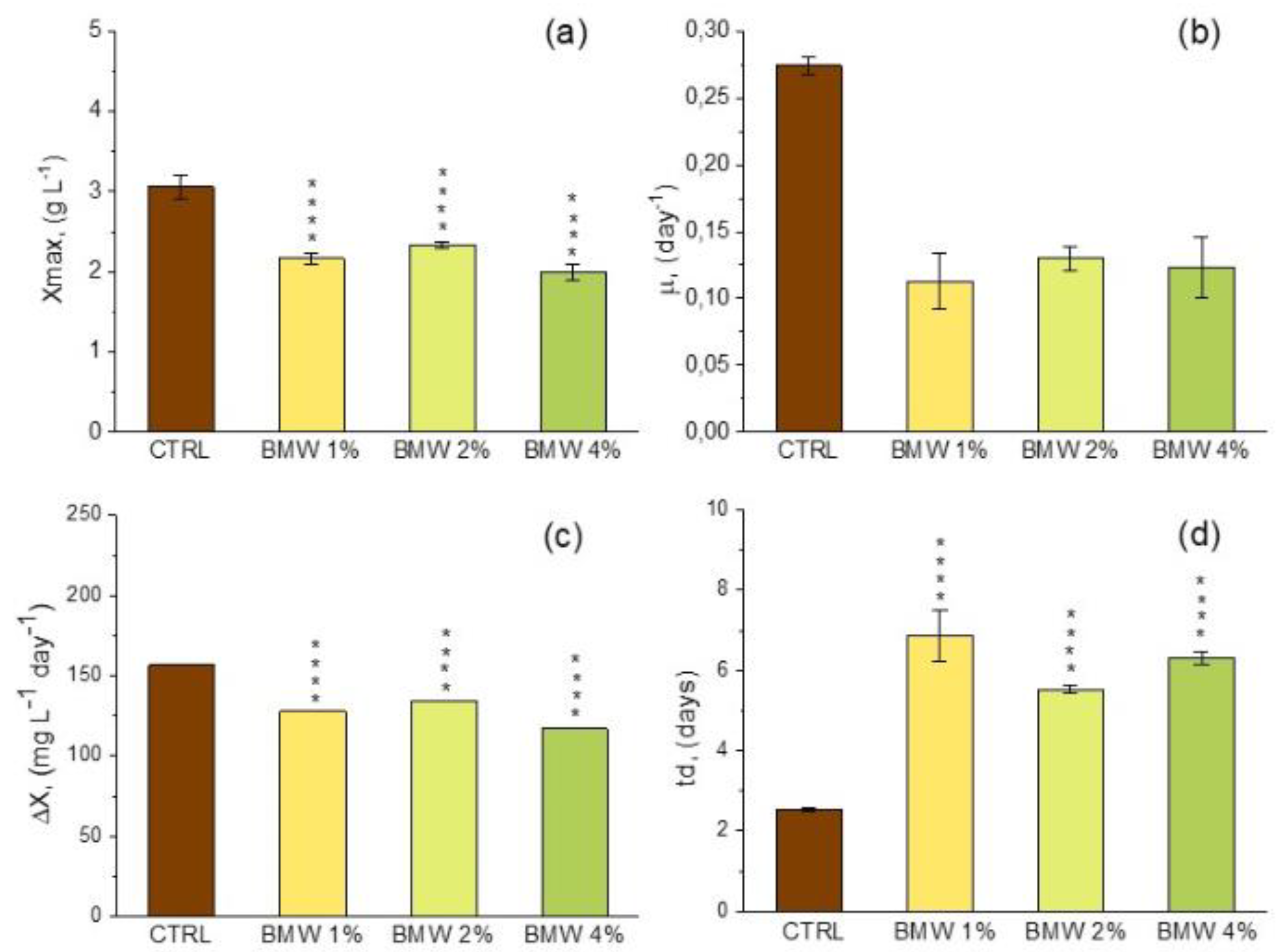

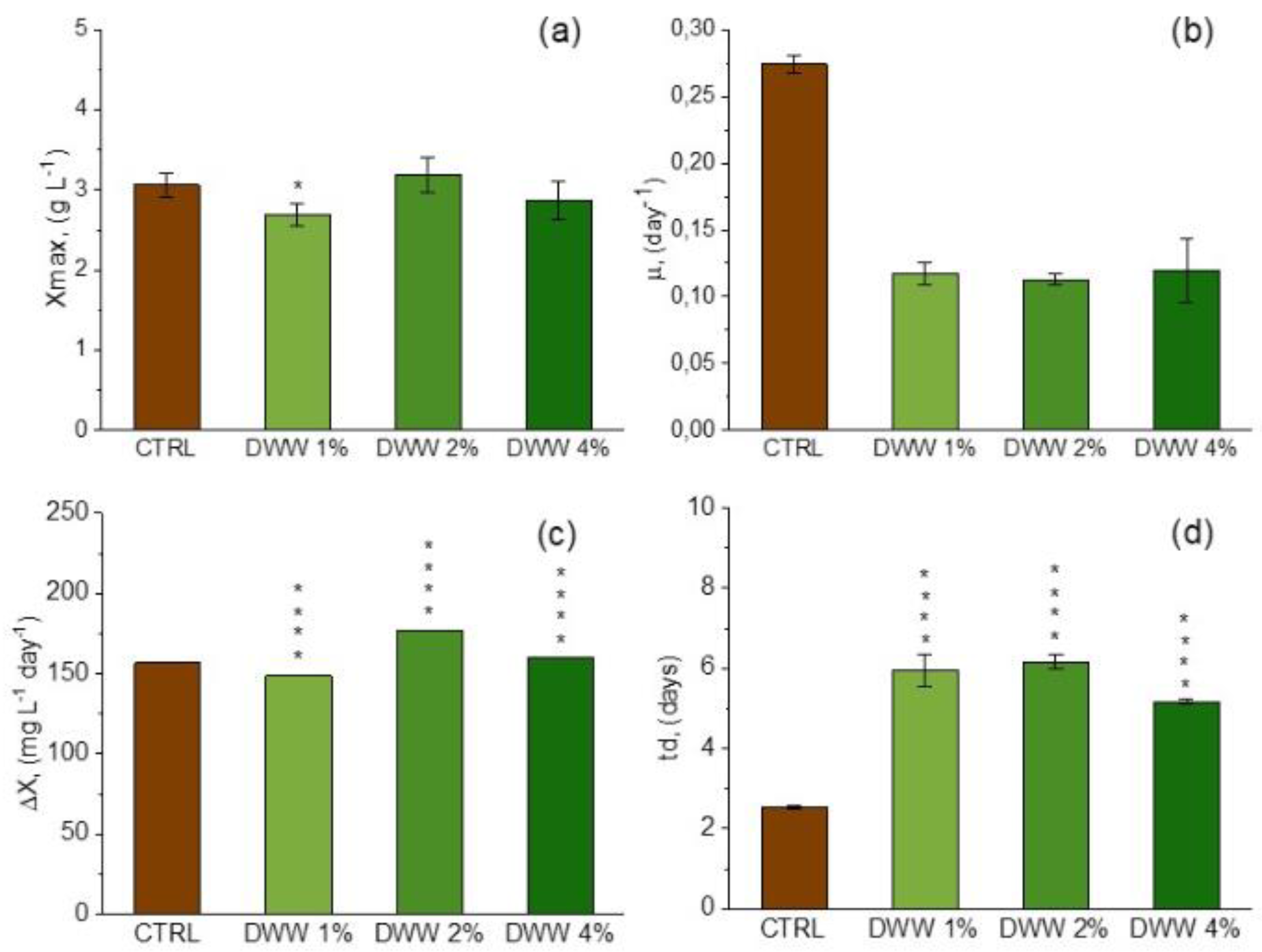

This study explores the mixotrophic cultivation of Arthrospira platensis using dairy byproducts, specifically scotta whey (SW), buttermilk wastewater (BMW), and dairy wastewater (DWW), to promote biomass production and enhance the composition of bioactive compounds. By assessing various concentrations (1%, 2%, and 4% v v-1) of these byproducts in a modified growth medium, the research aims to evaluate their effect on A. platensis growth, phycocyanin (C-PC) content, and fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) profiles. The results show that the optimal biomass production was achieved with 2% scotta and dairy wastewater, reaching maximum concentrations of 3.30 g L⁻¹ and 3.19 g L⁻¹, respectively. Mixotrophic cultivation led to increased C-PC yields, especially in buttermilk and dairy wastewater treatments, highlighting the potential for producing valuable pigments. Additionally, the FAME profiles indicated minimal changes compared to the control, with oleic and γ-linolenic acids being dominant in mixotrophic conditions. These findings support the viability of utilizing dairy byproducts for sustainable A. platensis cultivation, contributing to a circular bio-economy while producing bioactive compounds of nutritional and commercial interest.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inoculums and Culture Media Preparation

2.2. Cultivation Conditions and Experimental Setup

2.3. Cell Growth and Dry Weight Determination

2.4. Phycobilinproteins Extraction and Spectrophotometric Determination

2.5. FAMEs and Healthy Parameters Determination

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

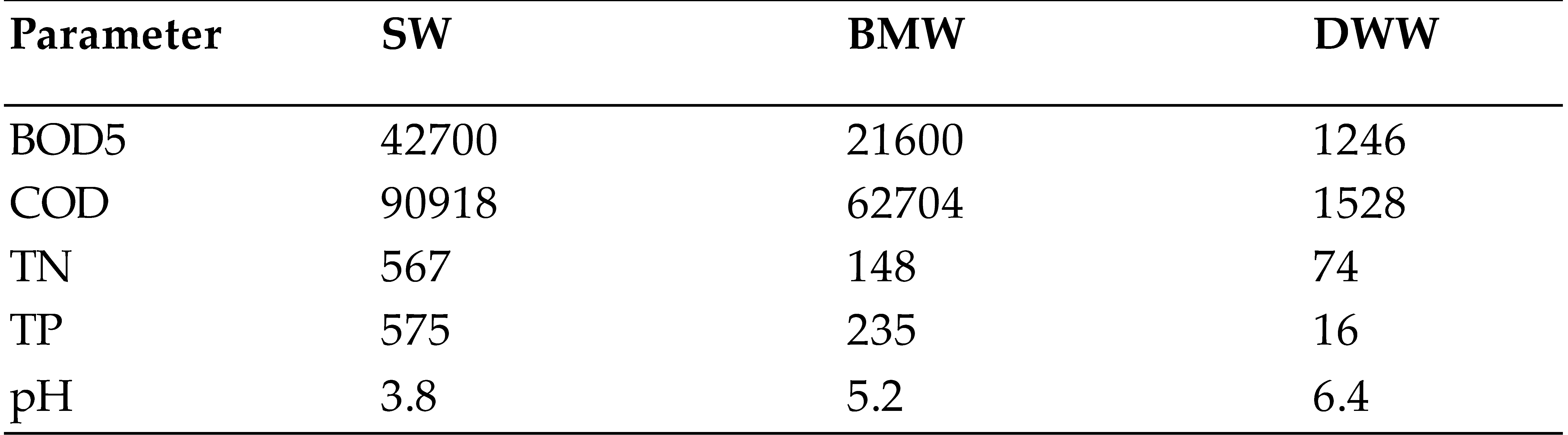

3.1. Cheese Effluents Composition

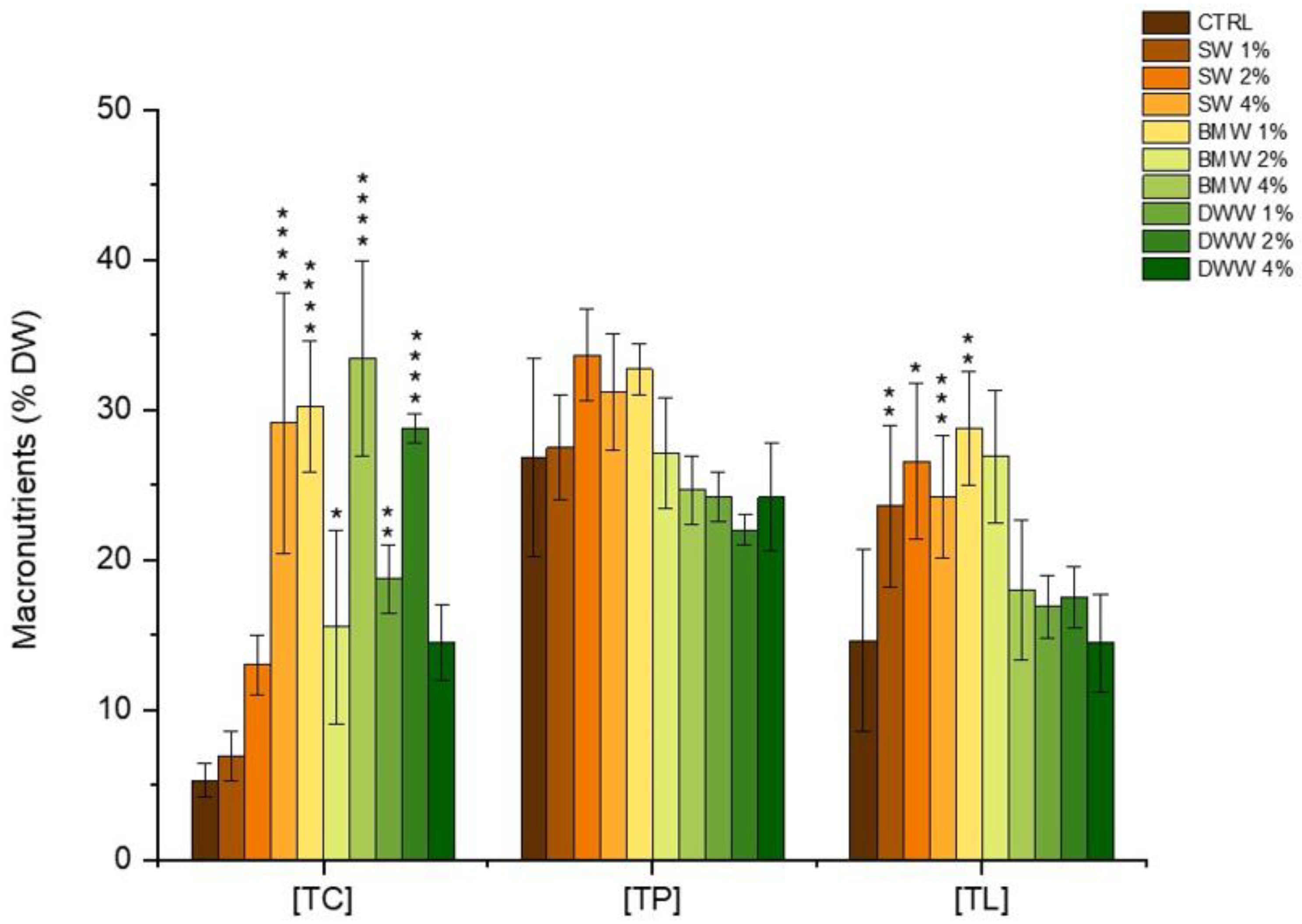

3.2. Growth Profile and Biomass Composition of A. platensis Using CW

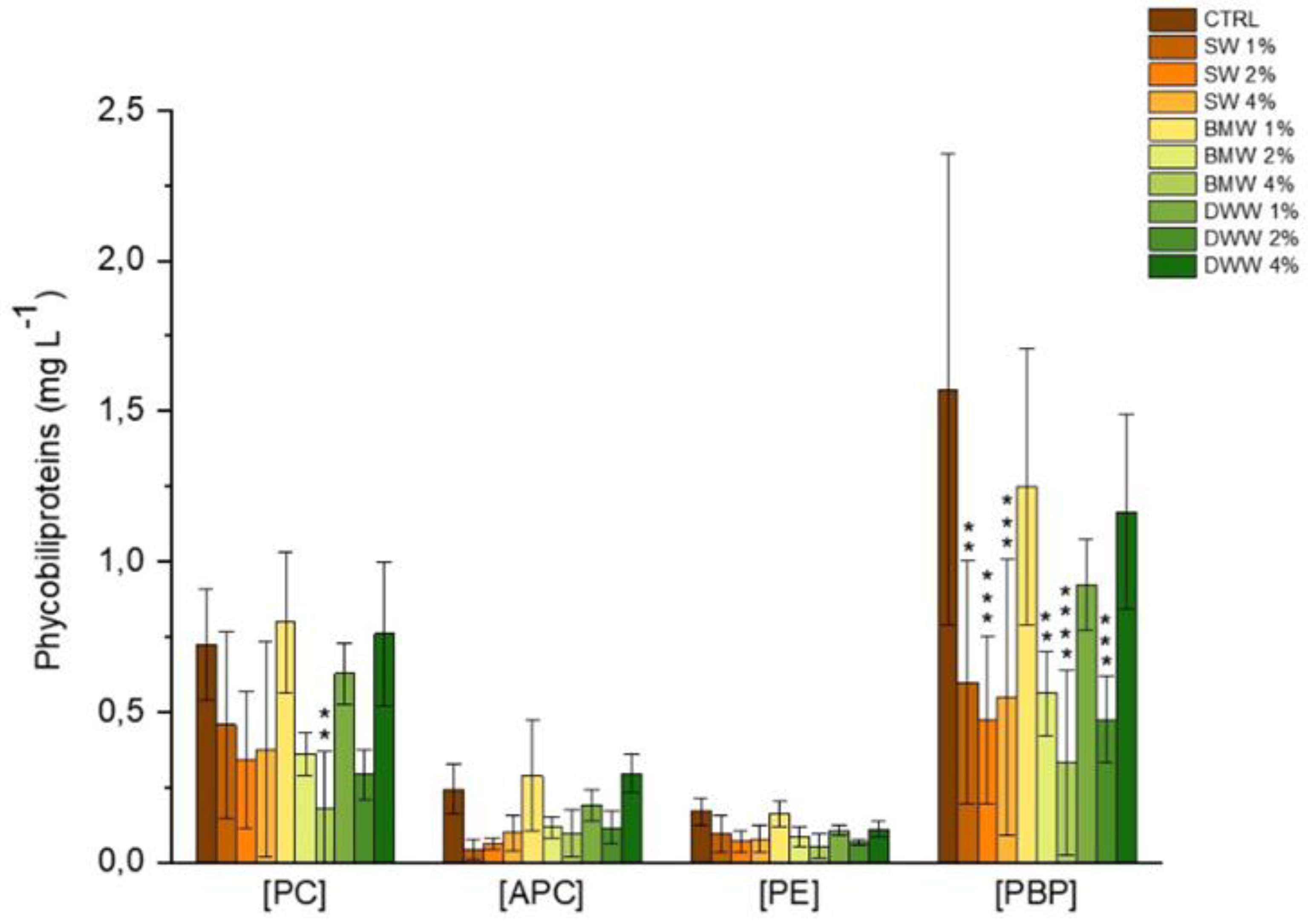

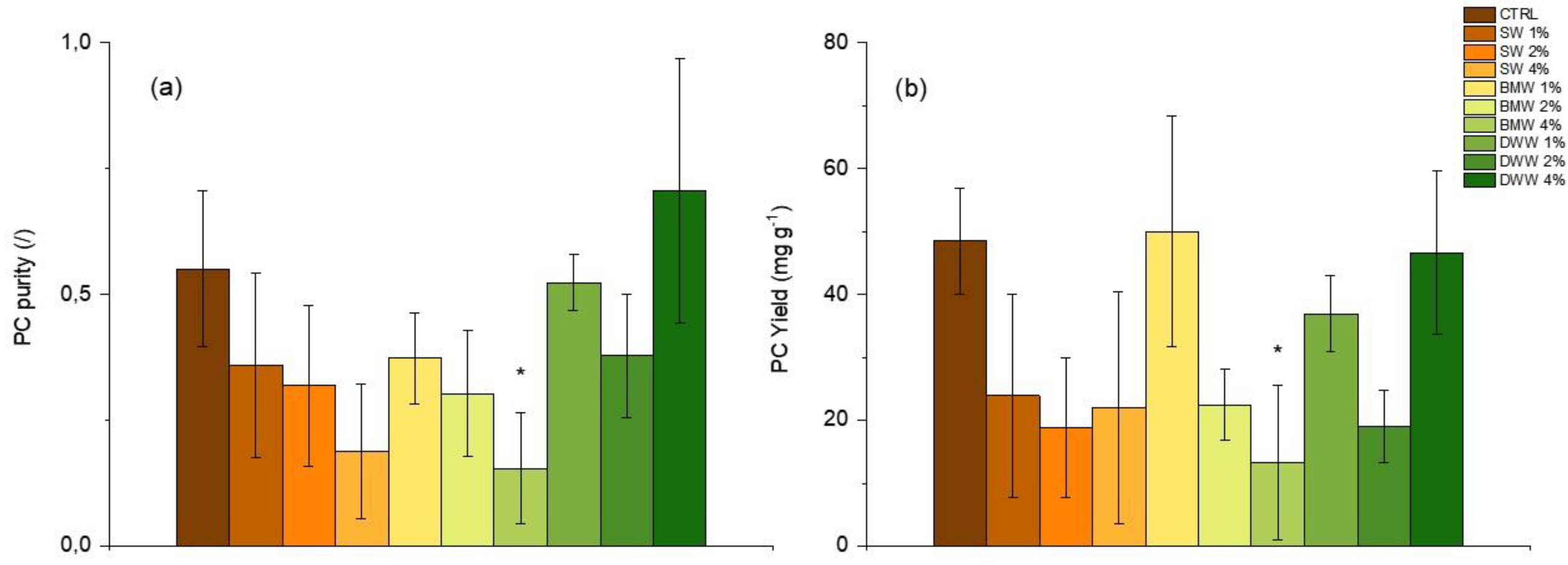

3.3. Phycobiliproteins Production by A. platensis Under Mixotrophic Conditions

3.4. FAME Profile by A. platensis Under Mixotrophy

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, N.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Wu, S.; Chen, R.; Yao, L.; Li, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z. Study on bioactive compounds of microalgae as antioxidants in a bibliometric analysis and visualization perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1144326. [CrossRef]

- Siddhnath; Surasani, V. K.R.; Singh, A.; Singh, S.M.; Hauzoukim, Narasimha Murthy, L.; Kirankumar Gopalbhai, B. Bioactive compounds from micro-algae and its application in foods: a review. Discov. Food, 2024; 4, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Cotas, J.; Valado, A. Antioxidants from microalgae and their potential impact on human well-being. Explor. Drug Sci. 2024; 2, 292–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, B.; Mishra, R.; Kumar, V.; Mishra, S.; Gupta, U.; Rustagi, S.; Kumar Gupta, A.; Preet, M.S.; Bhatt, S.C.; Rizwanuddin, S. Micro-algae: Revolutionizing food production for a healthy and sustainable future. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100939. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Janmeda, P.; Docea, A.O.; Yeskaliyeva, B.; Abdull Razis, A.F., Modu, B.; Calina, D.; Sharif-Rad, J. Oxidative stress, free radicals and antioxidants: potential crosstalk in the pathophysiology of human diseases. Front. Chem. 2023, 11, 1158198. [CrossRef]

- Eze, C.N.; Onyejiaka, C.K.; Ihim, S.A.; Ayoka, T.O.; Aduba, C.C.; Ndukwe, J.K.; Nwaiwu, O.; Onyeaka, H. Bioactive compounds by microalgae and potentials for the management of some human disease conditions. AIMS Microbiol. 2023, 9(1), 55-74. [CrossRef]

- Udayan, A.; Pandey, A.K.; Sirohi, R.; Sreekumar, N.; Sang, B-I.; Sim, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Pandey, A. Production of microalgae with high lipid content and their potential as sources of nutraceuticals. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22, 833–860. [CrossRef]

- Novoveská, L.; Nielsen, S.L.; Eroldoğan, O.T.; Haznedaroglu, B.Z.; Rinkevich, B.; Fazi, S.; Robbens, J.; Vasquez, E.H. Overview and Challenges of Large-Scale Cultivation of Photosynthetic Microalgae and Cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs. 2023, 21(8), 445. [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Wang, K.; Gao, F.; Ge, B.; Cui, H.; Li, W. Biotechnologies for bulk production of microalgal biomass: from mass cultivation to dried biomass acquisition. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2023, 16, 131. [CrossRef]

- Kiran, B.R.; Mohan, S.V. Microalgal cell biofactory-therapeutic, nutraceutical and functional food applications. Plants 2021, 10(5), 836. [CrossRef]

- Grand View Research. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/nutraceuticals-market. Accessed on September 15th 2024.

- Abreu, A.P.; Martins, R.; Nunes, J. Emerging applications of Chlorella sp. and Spirulina (Arthrospira) sp. Bioeng. 2023, 10(8), 955. [CrossRef]

- Alagawany, M.; Taha, A.E.; Noreldin, A.; El-Tarabily, K.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E. Nutritional applications of species of Spirulina and Chlorella in farmed fish: A review. Aquaculture 2021, 542, 736841. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves Bortolini, D.; Maciel, G.M.; de Andrade Arruda Fernandes, I.; Pedro, A.C.; Thaís Vieira Rubio, F.; Branco, I.G.; Haminiuk, C.W.I. Functional properties of bioactive compounds from Spirulina spp.: Current status and future trends. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Bastiaens, L.; Verspreet, J.; Hayes, M. Applications of Microalgae in Foods, Pharma and Feeds and Their Use as Fertilizers and Biostimulants: Legislation and Regulatory Aspects for Consideration. Foods. 2023, 12(20), 3878. [CrossRef]

- Gheda, S.; Abd El-Zaher, E.H.F.; Abou-Zeid, A.M.; Bedair, N.A.; Pereira, L. Potential activity of Arthrospira platensis as antioxidant, cytotoxic and antifungal against some skin diseases: Topical cream application. Mar. Drugs 2023, 21(3), 160. [CrossRef]

- Villaró, S.; Jiménez-Márquez, S.; Musari, E.; Bermejo, R.; Lafarga, T. Production of enzymatic hydrolysates with in vitro antioxidant, antihypertensive, and antidiabetic properties from proteins derived from Arthrospira platensis. Food Res. Int. 2023, 163, 112270. [CrossRef]

- Htoo, N.Y.M.; Kraseasintra, O.; Buncharoen, W.; Kaewkod, T.; Pekkoh, J.; Tragoolpua, Y.; Khoo, K.S.; Chaipoot, S.; Srinuanpan, S.; Pumas, C. In vitro immunomodulation activity of protein hydrolysate from Spirulina (Artrospira platensis): the ingredient of future foods. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1303025. Doi.10.3389/fmars.2024.13030325.

- Citi, V.; Torre S.; Flori, L.; Usai, L.; Aktay, N.; Dunford N.T.; Lutzu G.A.; Nieri P. Nutraceutical features of the phycobiliprotein C-phycocyanin: evidence from Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina). Nutrients 2024, 16(11), 1767. DOI: 10.3390/nu16111767.

- Guieysse, B.; Plouviez, M. Microalgae cultivation: closing the yield gap from laboratory to field scale. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1359755. [CrossRef]

- Vitali L.; Lolli V.; Sansone F.; Concas A.; Lutzu G.A. Lipid content and fatty acids methyl esters profile by Chromochloris zofingiensis under chemical and metabolic stress. Biomass Convers Bioref 2023. [CrossRef]

- Cavallini, A.; Torre, S.; Usai, L.; Casula, M.; Fais, G.; Nieri, P.; Concas, A.; Lutzu, G.A. Effect of Cheese Whey on Phycobiliproteins Production and FAME Profile by Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina): Promoting the Concept of a Circular Bio-Economy. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2024, 40, 101625. [CrossRef]

- Miotti, T.; Sansone, F.; Lolli, V.; Concas, A.; Lutzu G.A. Mixotrophic and heterotrophic metabolism in brewery wastewater by Chlorella vulgaris: Effect on growth, FAME profile and biodiesel properties. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2024, 109, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Miotti, T.; Sansone, F.; Lolli, V.; Concas, A.; Lutzu, G.A. Dairy wastewater to promote mixotrophic and heterotrophic metabolism in Chlorella vulgaris: Effect on growth and FAME profile. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2023, 98, 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Sales, D.C.; Rangel, A.H.N.; Urbano, S.A.; Freitas, A.R.; Tonhati, H.; Novaes, L.P.; Pereira, M.I.B.; Borba, L.H.F. Relationship between mozzarella yield and milk composition, processing factors, and recovery of whey constituents. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100(6), 4308–4321. [CrossRef]

- Adesra, A.; Srivastava, V.K.; Varjani, S. Valorization of Dairy Wastes: Integrative Approaches for Value Added Products. Indian J. Microbiol. 2021, 61(3), 270-278. [CrossRef]

- Ramsuroop, J.; Gutu, L.; Ayinde, W.B.; Basitere, M.; Manono, M.S. A Review of Biological Processes for Dairy Wastewater Treatment and the Effect of Physical Parameters Which Affect Their Efficiency. Water 2024, 16, 537. [CrossRef]

- Nham, Q.; Mattson, L.; Legrand, C.; Lindehoff, E. Whey permeate as a phosphorous source for algal cultivation. Water Environ. Res. 2023, 95, e10865. [CrossRef]

- Youssef, A.M.; Gomaa, M.; Mohamed, A.K.S.H.; El-Shanawany, A-R.A. Enhancement of biomass productivity and biochemical composition of alkaliphilic microalgae by mixotrophic cultivation using cheese whey for biofuel production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 42875–42888. [CrossRef]

- Santos Ribeiro, J.E.; Martini, M.; Altomonte, I.; Salari, F.; Nardoni, S.; Sorce, C.; da Silva, F.L.H.; Andreucci, A. Production of Chlorella protothecoides biomass, chlorophyll and carotenoids using the dairy industry by-product scotta as a substrate. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 11, 207-213. [CrossRef]

- Occhipinti, P.S.; Del Signore, F.; Canziani, S.; Caggia, C.; Mezzanotte, V.; Ferrer-Ledo, N. Mixotrophic and heterotrophic growth of Galdieria sulphuraria using buttermilk as a carbon source. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2631–2643. [CrossRef]

- SAG. The Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Gottingen. Germany. Available on-line: https://sagdb.uni-goettingen.de/ (accessed on 26 January 2024).

- Jourdan, J-P. Cultivez Votre Spiruline - Manuel de Culture Artisanale de la Spirulina Publication Antenna Technologies. 1996.

- Herrera, A.; Boussiba, S.; Napoleone, V.; Hohlberg, A. Recovery of C-phycocyanin from the cyanobacterium Spirulina maxima. J. Appl. Phycol. 1989, 1, 325–331. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D.A.; Glazer, A.N.; Eiserling, F.A. Characterization and structural properties of the major biliproteins of Anabaena sp. Arch. Microbiol. 1976, 110, 61–75. [CrossRef]

- Breuer, G.; Evers, W.A.C.; de Vree, J.H.; Kleinegris, D.M.M.; Martens, D.E.; Wijffels, R.H.; Lamers, P.P. Analysis of fatty acid content and composition in microalgae. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 80, e50628. [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T. Coronary heart disease: Seven dietary factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992.

- Fernández, M.; Ordóñez, J.; Cambero, I.; Santos, C.; Pin, C.; Hoz, L. Fatty acid compositions of selected varieties of Spanish dry ham related to their nutritional implications. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 107-112. [CrossRef]

- Asunis, F.; De Gioannis, G.; Dessì, P.; Isipato, M.; Lens, P.N.L.; Muntoni, A.; Polettini, A.; Pomi, R.; Rossi, A.; Spiga, D. The dairy biorefinery: integrating treatment processes for cheese whey valorization. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111240. [CrossRef]

- Fancello, F.; Zara, G.; Hatami, F.; Scano, E.A.; Mannazzu, I. Unlocking the potential of second cheese whey: a comprehensive review on valorisation strategies. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 23, 411–441. [CrossRef]

- Kolev Slavov, A. Dairy wastewaters – general characteristics and treatment possibilities – a review. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 55, 14–28. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Aadil, T.R.M.; Ahmed, H.; Rahman, U.Ur.; Soares, B.C.V.; Souza, S.L.Q.; Pimentel, T.C.; Scudino, H.; Guimarães, J.T.; Esmerino, E.A.; Freitas, M.Q.; Almada, R.B.; Vendramel, S.M.R.; Silva, M.C.; Cruz, A.G. Treatment and utilization of dairy industrial waste: a review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 88, 361–372. [CrossRef]

- Sar, T.; Harirchi, S.; Ramezani, M.; Bulkan, G.; Akbas, M.Y.; Pandey, A.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Potential utilization of dairy industries by-products and wastes through microbial processes: a critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 810, 152253. [CrossRef]

- Salla, A.C.V.; Margarites, A.C.; Seibel, F.I.; Holz, L.C.; Briao, V.B.; Bertolin, T.E.; Colla, L.M.; Vieira Costa, J.A. Increase in the carbohydrate content of the microalgae Spirulina in culture by nutrient starvation and the addition of residues of whey protein concentrate. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 209, 133–141. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.I.B.; Chagas, B.M.E.; Sassi, R., Medeiros, G.F.; Aguiar, E.M.; Borba, L.H.F.; Silva, E.P.E.; Andrade Neto, J.C.; Rangel, A.H.N. Mixotrophic cultivation of Spirulina platensis in dairy wastewater: Effects on the production of biomass, biochemical composition and antioxidant capacity. PLoS ONE 2019, 14(10), e0224294. [CrossRef]

- Gramegna, G.; Scortica, A.; Scafati, V.; Ferella, F.; Gurrieri, L.; Giovannoni, M.; Bassi, R.; Sparla, F.; Mattei, B.; Benedetti, M. Exploring the potential of microalgae in the recycling of dairy wastes. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100604. [CrossRef]

- Kiani, H.; Ma, Q.; Xiao, M.; Li, Y.; Brooke, F.J.; Mulcahy, S.; Miros, S.; Halim, R. Growth and fatty acid profile of Nannochloropsis oceanica cultivated on nano-filtered whey permeate. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zurano, A.; Villaró-Cos, S.; Ciardi, M.; Acién-Fernández, F.G.; Fernández-Sevilla, J.M.; Lafarga, T. Assessment of the mixotrophic production of Chlorella vulgaris using milk whey as a nutrient source. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 87–100. [CrossRef]

- Markou, G.; Kougia, E.; Arapoglou, D.; Chentir, I.; Andreou, V.; Tzovenis, I. Production of Arthrospira platensis: Effects on Growth and Biochemical Composition of Long-Term Acclimatization at Different Salinities. Bioengineering 2023, 10(2), 233. [CrossRef]

- Arahou, F.; Hassikou, R.; Arahou, M.; Rahzi, L.; Wahby, I. Influence of culture conditions on Arthrospira platensis growth and valorization of biomass as input for sustainable agriculture. Aquacult. Int. 2021, 29, 2009–2020. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qin, S.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q.; Li, W.; Gao, Y. Phycobiliproteins from microalgae: research progress in sustainable production and extraction processes. Biotechnol Biofuels 2023, 16, 170. [CrossRef]

- Nur, M.M.A.; Rahmawati, S.D.; Sari, I.W.; Achmad, Z.; Setyoningrum, T.M.; Jaya, D.; Murni, S.W.; Djarot, I.N. Enhancement of phycocyanin and carbohydrate production from Spirulina platensis growing on tofu wastewater by employing mixotrophic cultivation condition. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 47, 102600. [CrossRef]

- Russo, N.P.; Ballotta, M.; Usai, L.; Torre, S.; Giordano, M.; Casula, M.; Fais, G.; Dessi, D.; Nieri, P.; Damergi, E.; Concas, A.; Lutzu, G.A. Mixotrophic cultivation of Arthrospira platensis (Spirulina) under salt stress: Effect on biomass composition, FAME profile, and phycocyanin content. Mar. Drugs 2024, 22(9), 381. [CrossRef]

- Pavan, M.; Reinmets, K.; Garg, S.; Mueller, A.P.; Marcellin, E.; Köpke, M.; Valgepea, K. Advances in Systems Metabolic Engineering of Autotrophic Carbon Oxide-Fixing Biocatalysts towards a Circular Economy. Metab. Eng. 2022, 71, 117-141. [CrossRef]

- Athanasiadou, V.; Klontza, E.E.; Dimitriou-Christidis, P.; Fountoulakis, M.; Lekkas, D.F. Evaluation of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis growth on cheese whey in the context of circular economy. Sustain. Chem. Pharm. 2023, 34, 101173.

- Salah, A.; Sany, H.; El-Sayed, A.EK.B; El-Bahbohy, R.M.; Mohamed, H.I.; Amin, A. Growth Performance and Biochemical Composition of Desmodesmus sp. Green Alga Grown on Agricultural Industries Waste (Cheese Whey). Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 770. [CrossRef]

- Salati, S.; D'Imporzano, G.; Menin, B.; Veronesi, D.; Scaglia, B.; Abbruscato, P.; Mariani, P.; Adani, F. Mixotrophic cultivation of Chlorella for local protein production using agro-food by-products. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 230, 82-89. [CrossRef]

- Soni, B.; Sudhakar, K. Phycocyanin production, extraction and purification techniques: A review. Algal Res. 2021, 59, 102486. [CrossRef]

- Lauceri, R.; Cavone, C.; Chini Zittelli, G.; Kamburska, L.; Musazzi, S.; Torzillo, G. High purity grade phycocyanin recovery by decoupling cell lysis from the pigment extraction: an innovative approach. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16(1), 111–121. [CrossRef]

- da Silva Figuera, F.; Costa Moraes, C.; Juliano Kalil, S. C-Phycocianin purification: Multiple processes for different applications. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35 (3). [CrossRef]

- Kurpan, D.; Idà, A.; Körner, F.; Lauceri, R.; Rocculli, P.; Phillips, R.; Scievano, A. Pilot-scale concentration and partial purification of food-grade phycocyanin from Arthrospira platensis via cross flow filtration: From biomass to final product. J. Appl. Phycol. 2023, 35, 2709–2718. [CrossRef]

- MRFB – 104430. Phycocyanin Market Size, Share, Forecast, and Trends Analysis by Form (Powder, Liquid), Grade (Food-grade, Reagent grade, Cosmetic-grade Phycocyanin), Category (Non-Organic), Application (Food and Beverages, Pharaceuticals) – Global Forecast to 2031. 2024, Pag. 194.

- Ali, S.S.; Hassan, L.H.; El-Sheekh, M. Microalgae-mediated bioremediation: current trends and opportunities-a review. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 343. [CrossRef]

- Maroneze, M.M.; Dias, R.R.; Severo, I.A.; Queiroz, M.I. Microalgae-Based Processes for Pigments Production. In: Pigments from Microalgae Handbook; Jacob-Lopes, E., Queiroz, M., Zepka, L., Eds.; Springer, Cham. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; He, W.; Yang, S.; Sun, H.A comprehensive review on the heterotrophic production of bioactive compounds by microalgae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 40, 210. [CrossRef]

- Devi, A.; Kalwani, M.; Patil, K.; Kumari, A.; Tyagi, A.; Shukla, P.; Pabbi, S. Microalgal Bio-pigments: Production and Enhancement Strategies to Enrich Microalgae-Derived Pigments. In: Cyanobacterial Biotechnology in the 21st Century; Neilan, B.; Passarini, M.R.Z.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, A., Eds.; Springer, Singapore. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Perna, M.; Hewlings, S. Saturated Fatty Acid Chain Length and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 30. [CrossRef]

- Palomino, O.M.; Giordani, V.; Chowen, J.; Alfonso, S.F.; Goya, L. Physiological Doses of Oleic and Palmitic Acids Protect Human Endothelial Cells from Oxidative Stress. Molecules 2022, 27(16), 5217. [CrossRef]

- Delcheva, G.; Stefanova, K.; Stankova, T. Ceramides—Emerging Biomarkers of Lipotoxicity in Obesity, Diabetes, Cardiovascular Diseases, and Inflammation. Diseases 2024, 12, 195. [CrossRef]

- Cicerale, S; Lucas, L.; Keast, R.S.J. Biological Activities of Phenolic Compounds Present in Virgin Olive Oil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2010, 11(2), 458-479. [CrossRef]

- Maltsev, Y.; Maltseva, K. Fatty Acids of Microalgae: Diversity and Applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 20(2), 515. [CrossRef]

- Khannapho, C.; Phodee, A.; Paithoonrangsarid, K.; Hongstongh, A.; Meechai, A.; Cheevadhanarah, S.; Tanticharoen, M. Effect of dilution rate in continuous cultures of Arthrospira (Spirulina) platensis C1 on nutrient use efficiency and macromolecular- and elemental compositions. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 743–754. [CrossRef]

- Prete, V.; Abate, A.C.; Di Pietro, P.; De Lucia, M.; Vecchione, C.; Carrizzo, A. Beneficial Effects of Spirulina Supplementation in the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2024, 16, 642. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Lista, J.; Perez-Martinez, P.; Lopez-Miranda, J.; Perez-Jimenez, F. Long chain omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107(2), S201-13. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, N.; Han, P.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, C. Associations of polyunsaturated fatty acids with cardiovascular disease and mortality: a study of NHANES database in 2003–2018. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2023, 23, 185. [CrossRef]

- Zock, P.L.; Blom, W.A.M.; Nettleton, J.A.; Hornstra, G. Progressing Insights into the Role of Dietary Fats in the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Cardiol. Rep. 2016, 18, 111. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.A.; Medeiros, V.P.B.; Costa, W.K.A., dos Santos, R.L., Somera, T.; Pimentel, T.C.; Magnani, M. Challenges and Perspectives for Alternative Media in Microalgae Cultivation: Main Substrates and Approaches and Potential of Alternative Derived Biomasses as Source of Bioactives. In: Microalgal Bioengineering; Costa, J.A.V.; Mitchell, B.G.; Benemann, J., Eds. Springer, Cham. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, X.; Fan, C.; Wu, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Health Benefits, Food Applications, and Sustainability of Microalgae-Derived N-3 PUFA. Foods 2022, 11, 1883. [CrossRef]

- Conde, T.A.; Neves, B.F.; Couto, D.; Melo, T.; Neves, B.; Costa, M.; Silva, J.; Domingues, P.; Domingues, M.R. Microalgae as Sustainable Bio-Factories of Healthy Lipids: Evaluating Fatty Acid Content and Antioxidant Activity. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19(7), 357. [CrossRef]

- Matos, Â.P.; Feller, R.; Moecke, E.H.S.; de Oliveira, J.V.; Junior, A.F.; Derner, R.B.; Sant’Anna, E.S. Chemical Characterization of Six Microalgae with Potential Utility for Food Application. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2016, 93, 963-972. [CrossRef]

- Centeno da Rosa., A.P.; Moraes, L.; de Morais, E.G.; Costa, J.A.V. Fatty Acid Biosynthesis from Chlorella in Autotrophic and Mixotrophic Cultivation. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2020, 63, e20180534. [CrossRef]

- Laraib, N.; Manzoor, M.; Javid, A.; Jabeen, F.; Bukhari, S.M.; Ali, W.; Hussain A. Mixotrophic cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris in sugarcane molasses preceding nitrogen starvation: Biomass productivity, lipid content, and fatty acid analyses. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. 2021; 40, e13625. [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.S., Kim, Y.S., Yoon, H.S. Effect of Different Cultivation Modes (Photoautotrophic, Mixotrophic, and Heterotrophic) on the Growth of Chlorella sp. and Biocompositions. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021; 9, 774143. [CrossRef]

- Ogbonna, K.E.; Ogbonna, J.C.; Njoku, O.U.; Yamada, K.; Suzuki, I. Effect of organic carbon sources on growth, lipid production and fatty acid profile in mixotrophic culture of Scenedesmus dimorphus (Turpin) Kützing, The Microbe, Volume 3, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, H.; Nezhad, S. Improvement in biochemical parameters and changes in lipid profile of Scenedesmus obliquus by plant growth regulators under mixotrophic condition. Biomass Bioenergy. 2020, 140. 105708. 10.1016/j.biombioe.2020.105708.

- Přibyl, P.; Cepák, V. Screening for heterotrophy in microalgae of various taxonomic positions and potential of mixotrophy for production of high-value compounds. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31. 10.1007/s10811-019-1738-9.

|

|

| FAMEs | C:N$ | CTRL | SW-1% | SW-2% | SW-4% | BMW-1% | BMW-2% | BMW-4% | DWW-1% | DWW-2% | DWW-4% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristic acid | 14:00 | 1.80 ± 0.16 | 1.96 ± 1.07 | 2.32 ± 0.87 | 2.60 ± 0.74 | 2.57 ± 0.34 | 2.58 ± 0.44 | 2,16 ± 0.18 | 2.90 ± 0.20⁕⁕ | 2.74 ± 0.32⁕ | 2.72 ± 0.11⁕ |

| Hexadecanoic acid | 16:00 | 40.09 ± 4.77 | 42.77 ± 1.54 | 41.74 ± 1.07 | 40.35 ± 1.11 | 40.88 ± 0.58 | 41.48 ± 0.50 | 41.81 ± 0.64 | 41.83 ± 0.56 | 42.55 ± 0.53 | 42.15 ± 0.45 |

| Hexadecenoic acid | 16:01 | 3.79 ± 0.70 | 4.56 ± 0.71 | 4.36 ± 0.46 | 5.65 ± 1.00 | 6.00 ± 1.29 | 5.28 ± 0.38 | 6.43 ± 0.22 | 4.07 ± 0.24 | 3.77 ± 0.37 | 4.08 ± 0.91 |

| Heptadecanoic acid | 17:00 | 0.22 ± 0.08 | 0.18 ± 0.07 | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.00 | 0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.02 |

| 10-Heptadecenoic acid | 17:1 cis | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.31 ± 0.14 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.36 ± 0.15 | 0.28 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.06 | 0.20 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.02 | 0.17 ± 0.07 | 0.21 ± 0.05 |

| Stearic acid | 18:00 | 26.81 ± 2.35 | 19.71 ± 7.37 | 17.11 ± 2.31 | 15.53 ± 4.34 | 14.99 ± 0.33 | 16.18 ± 2.11 | 18.56 ± 1.62 | 19.63 ± 0.15 | 22.35 ± 1.71 | 20.93 ± 1.97 |

| Elaidic acid | 18:1 trans | 0.63 ± 0.24 | 0.78 ± 0.08 | 1.54 ± 0.37 | 3.80 ± 1.17 | 1.37 ± 0.27 | 1.13 ± 0.32 | 1.53 ± 0.18⁕ | 1.21 ± 0.10 | 1.23 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.12 |

| Oleic acid | 18:1 cis | 5.91 ± 0.48 | 6.29 ± 1.77 | 5.59 ± 0.50 | 6.19 ± 0.88 | 6.05 ± 0.27 | 5.98 ± 1.48 | 4.63 ± 0.29 | 6.18 ± 1.38 | 5.00 ± 1.03 | 5.97 ± 0.17 |

| Linoleic acid | 18:02 | 7.26 ± 0.31 | 8.40 ± 2.04 | 8.82 ± 0.22 | 9.18 ± 2.29 | 9.75 ± 0.55 | 9.45 ± 0.84 | 8.58 ± 0.72 | 8.39 ± 0.79 | 7.55 ± 0.77 | 8.06 ± 0.91 |

| α-Linolenic acid | 18:3 ω-3 | 1.24 ± 0.05 | 0.57 ± 0.61 | 0.83 ± 0.74 | 0.36 ± 0.22 | 0.69 ± 0.42 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.09 | 0.40 ± 0.06 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | 0.49 ± 0.28 |

| y-Linolenic acid | 18:3 ω-6 | 10.60 ± 0.51 | 13.33 ± 3.17 | 15.66 ± 1.12 | 14.33 ± 2.63⁕ | 15.70 ± 0.95 | 15.34 ± 0.93 | 14.48 ± 1.32⁕⁕ | 13.65 ± 0.71 | 12.63 ± 1.02 | 13.11 ± 1.07 |

| 8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | 20:03 | 1.19 ± 0.12 | 0.96 ± 0.30 | 0.99 ± 0.25 | 0.89 ± 0.23 | 1.18 ± 0.23 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 1.05 ± 0.23 | 1.03 ± 0.20 | 1.03 ± 0.15 |

| 13-Docosenoic acid | 22:01 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 0.58 ± 0.32 | 0.57 ± 0.21 | 0.40 ± 0.05 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 0.39 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.24 ± 0.05 |

| Σ SFAs | / | 68.92 | 64.62 | 61.32 | 58.68 | 59.78 | 60.39 | 62.67 | 64.49 | 67.76 | 65.92 |

| Σ UFAs | / | 31.08 | 35.39 | 38.68 | 41.33 | 41.02 | 39.61 | 37.33 | 35.51 | 32.25 | 34.06 |

| Σ MUFAs | / | 10.79 | 12.13 | 12.38 | 16.57 | 13.7 | 13.05 | 13.18 | 12.02 | 10.52 | 11.37 |

| Σ PUFAs | / | 20.29 | 23.26 | 26.30 | 24.76 | 27.32 | 26.56 | 24.15 | 23.49 | 21.73 | 22.69 |

| PUFA:SFA | / | 0.29 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.44 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.32 | 0.34 |

| C16-C18 | / | 96.33 | 96.41 | 95.65 | 95.39 | 95.43 | 95.40 | 96.23 | 95.36 | 95.60 | 95.66 |

| h/H | / | 0.64 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.66 |

| Microalgae | Organic source | TI | AI | h/H ratio | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arthrospira platensis | dairy | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.81 | This work |

| Arthrospira platensis | photoautotrophy | 1.60 | 0.70 | 0.60 | [79] |

| Arthrospira platensis | photoautotrophy | 1.46 | 1.1 | 0.66 | [80] |

| Arthrospira platensis | dairy | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.07 | [22] |

| Arthrospira platensis | brewery | 3.51 | 1.76 | 0.74 | [24] |

| Chlorella kessleri | glucose | 1.51 | 1.64 | 1.47 | [81] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | molasses | 0.79 | 0.71 | 2.67 | [82] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | glucose | 0.42 | 0.40 | 2.80 | [81] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | glucose | 0.38 | 0.39 | 2.36 | [83] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | brewery | 0.48 | 1.21 | 2.55 | [23] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | dairy | 0.59 | 1.77 | 1.86 | [24] |

| Chlorella sorokiniana | glucose | 0.31 | 0.45 | 1.76 | [83] |

| Chlorella sorokiniana | glucose | 0.42 | 0.49 | 2.00 | [83] |

| Chromocloris zofingensis | molasses | 0.40 | 0.23 | 3.73 | [21] |

| Chromocloris zofingensis | dairy | 0.40 | 0.21 | 4.22 | [21] |

| Nannochloropsis oceanica | photoautotrophy | 0.30 | 0.60 | 1.44 | [79] |

| Scenedesmus dimorphus | glucose | 4.00 | 1.68 | 1.07 | [84] |

| Scenedesmus obliquus | sodium acetate | - | - | 2.09 | [85] |

| Tetraselmis chui | photoautotrophy | 0.20 | 0.40 | 1.04 | [79] |

| Tribonema aequale | glucose | 0.18 | 1.02 | 3.70 | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).