Submitted:

06 October 2023

Posted:

09 October 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tetradesmus obliquus biomass processing

2.2. Composition of the Tetradesmus obliquus microalgae

2.3. Separation and identification of proteins from the microalgae Tetradesmus obliquus

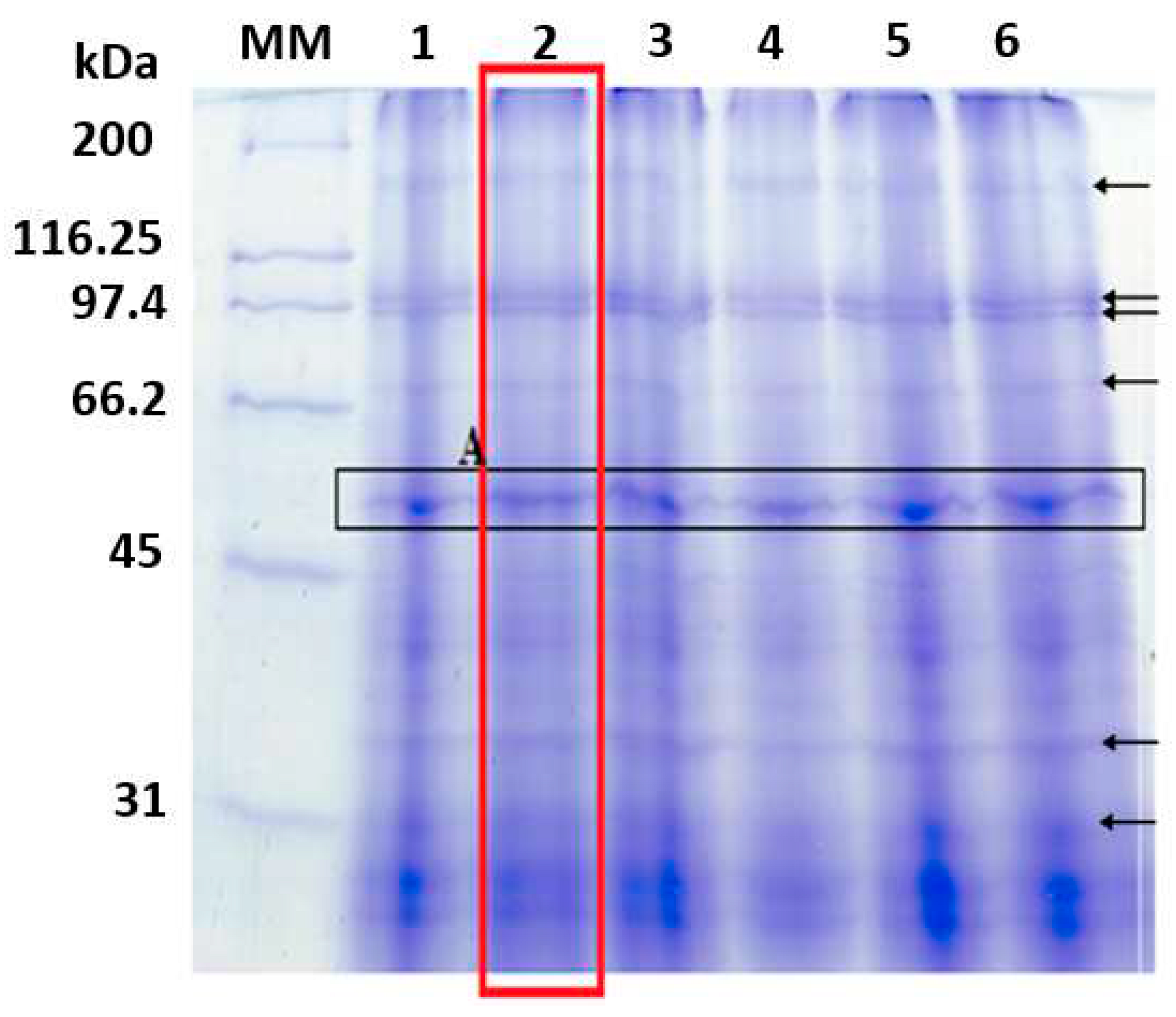

- Molecular mass profile

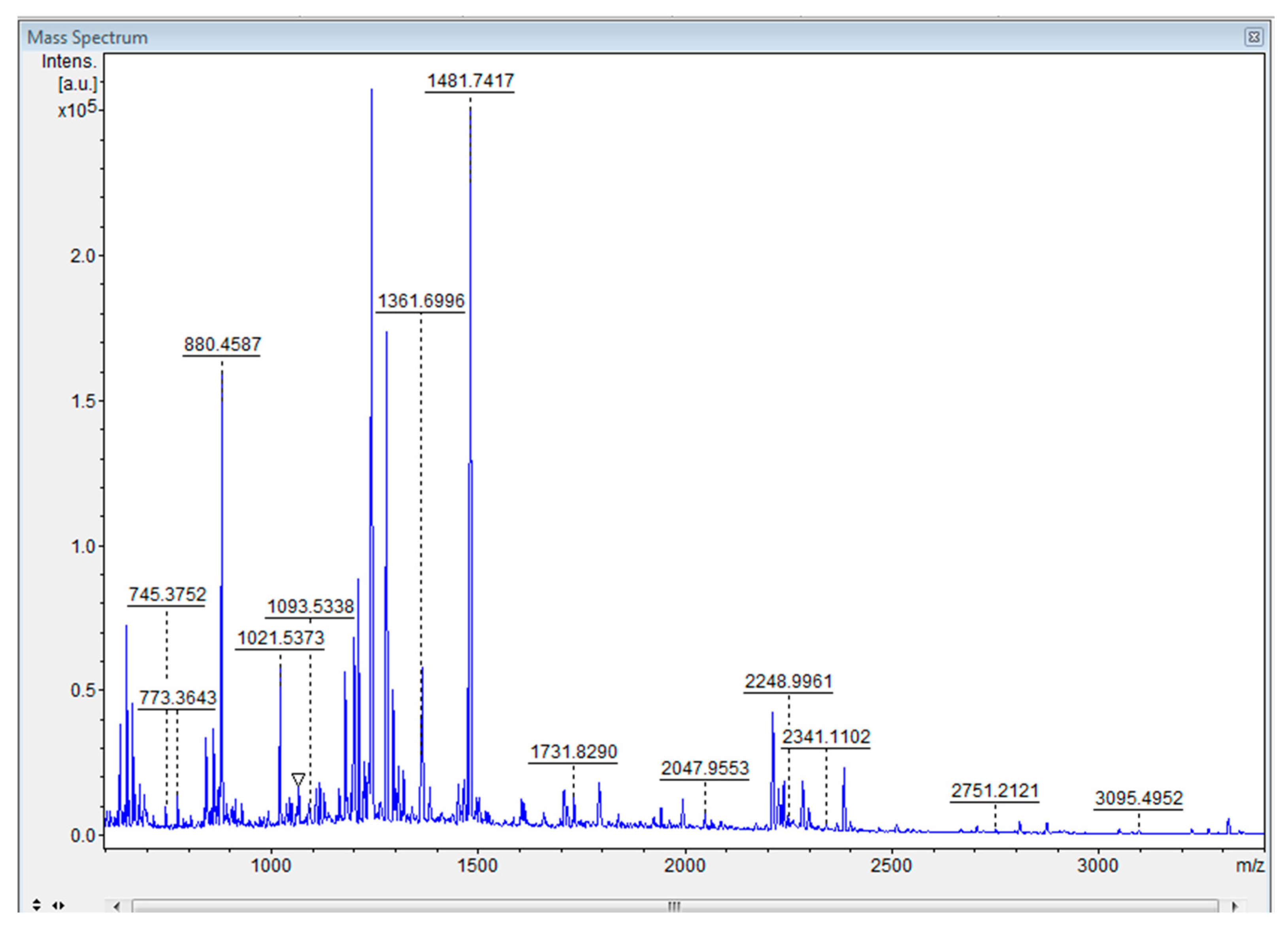

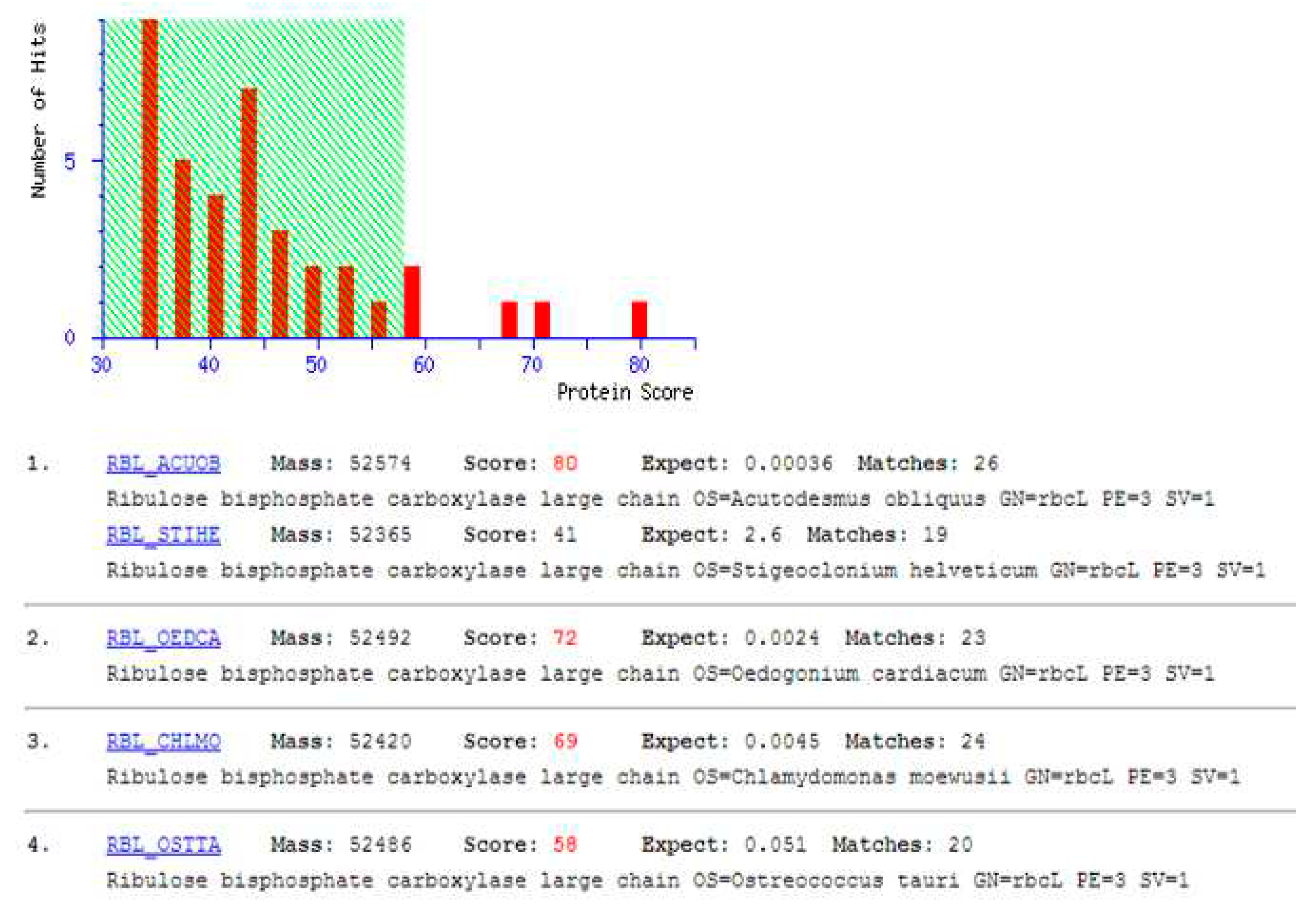

- Identification by mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF)

2.3. Biomass cell disruption

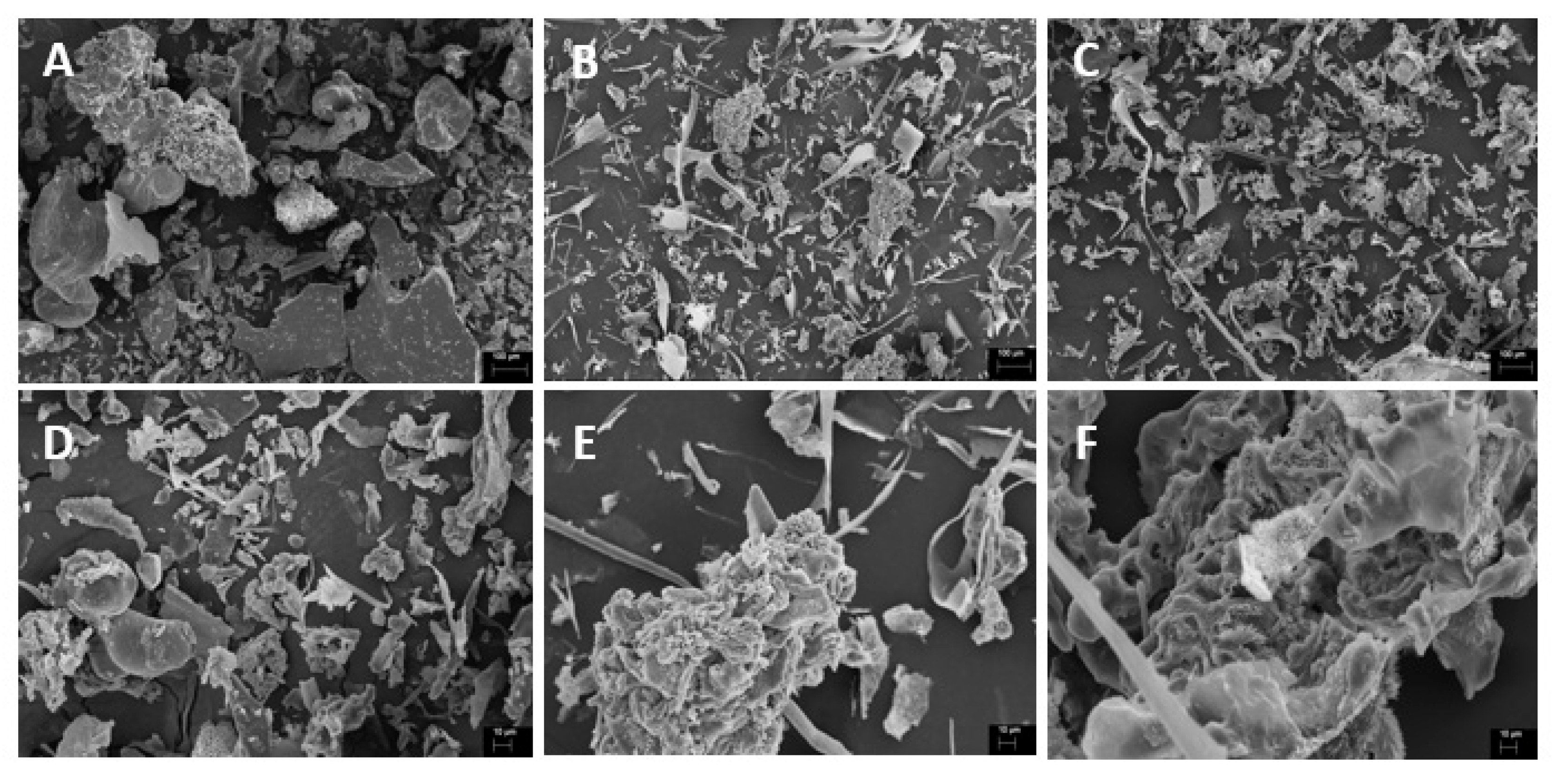

- Mechanical disruption by ball mill: The freeze-dried biomass was mechanically disrupted in a ball mill (model MR350, Tecnal Equipamentos Científicos, Brazil) using 10 g of biomass batches for 25 min, following Vieira et al. [16]. The disrupted biomass was kept at 20 °C until use.

- Mechanical disruption by ultrasound: The freeze-dried biomass was mechanically disrupted by ultrasound after resuspension in distilled water (5.0% w/v), following Silva et al. [24] with adaptations. The suspensions were mechanically stirred (IKA, RW20 digital, Germany) at 25.0 °C overnight and disrupted in a tip sonicator (Sonics, VCX 500, USA) at 20 kHz frequency and 98% amplitude for 6 min of ultrasonication. The cells were disrupted under cooling in an ice bath to avoid overheating the system. After disruption, cell suspensions were frozen, freeze-dried (Terroni, LS 3000, Brazil), and stored at 20 °C until use.

- Mechanical disruption by high-pressure homogenization: The microalgal biomass was suspended in distilled water (1.5% w/v) and processed in a homogenizer (Alitec, A100, Brazil) at 350 bar, according to Shene et al. [25]. The number of passes of the suspensions in the homogenizer was 25, and the suspension was cooled to avoid compound degradation due to the temperature increase. The homogenized samples were collected, frozen, freeze-dried (Terroni, LS 3000, Brazil), and stored at 20 °C until use.

2.4. Cell disruption indicators

- Evaluation of the cell disruption level through cell counting

- Evaluation of the cell disruption level through the amount of extracted soluble protein

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Composition of T. obliquus biomass

4.2. Identification of T. obliquus protein extract

4.3. Cell rupture and protein extraction from T. obliquus

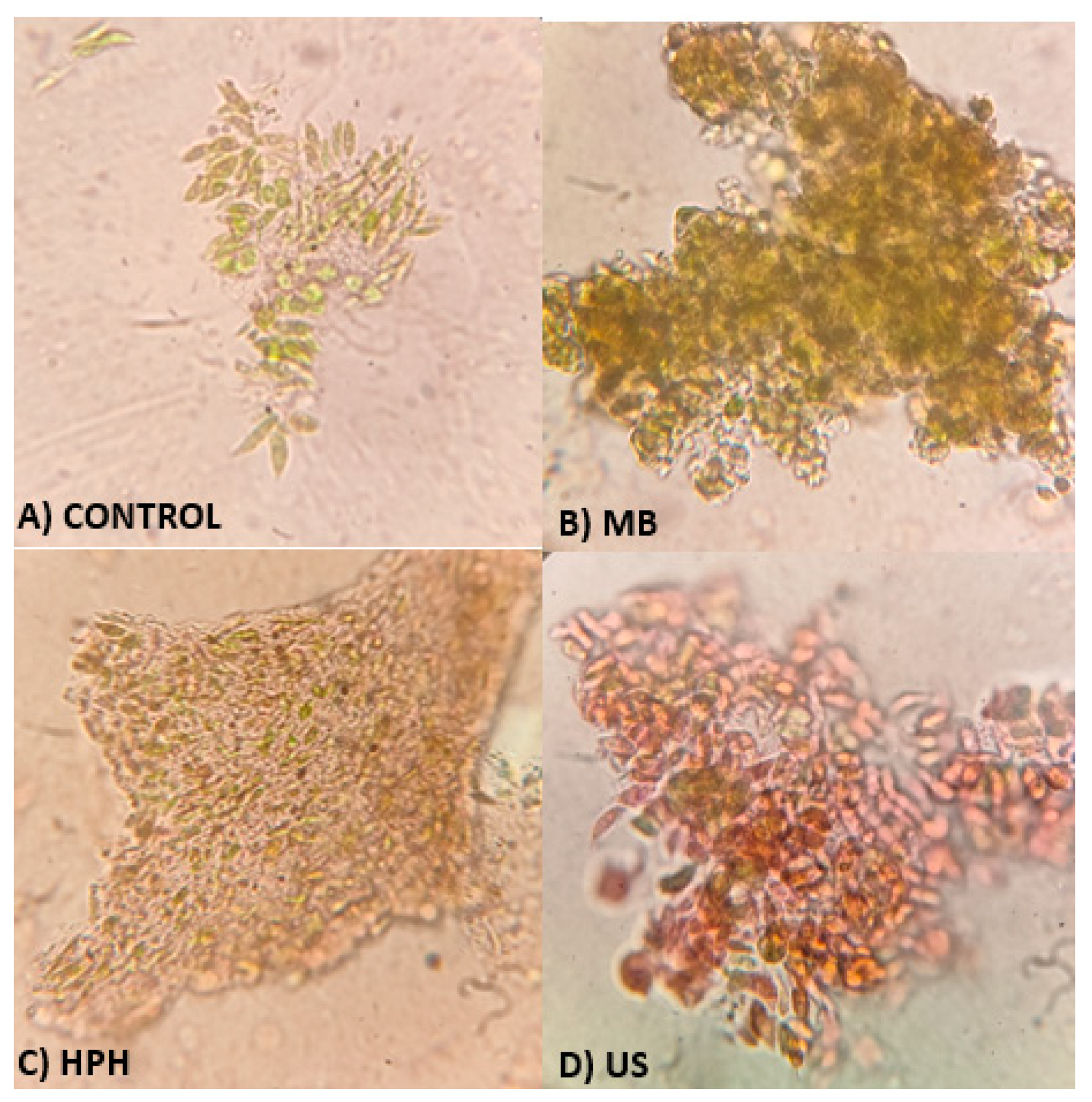

- Evaluation of the cell disruption level through cell counting

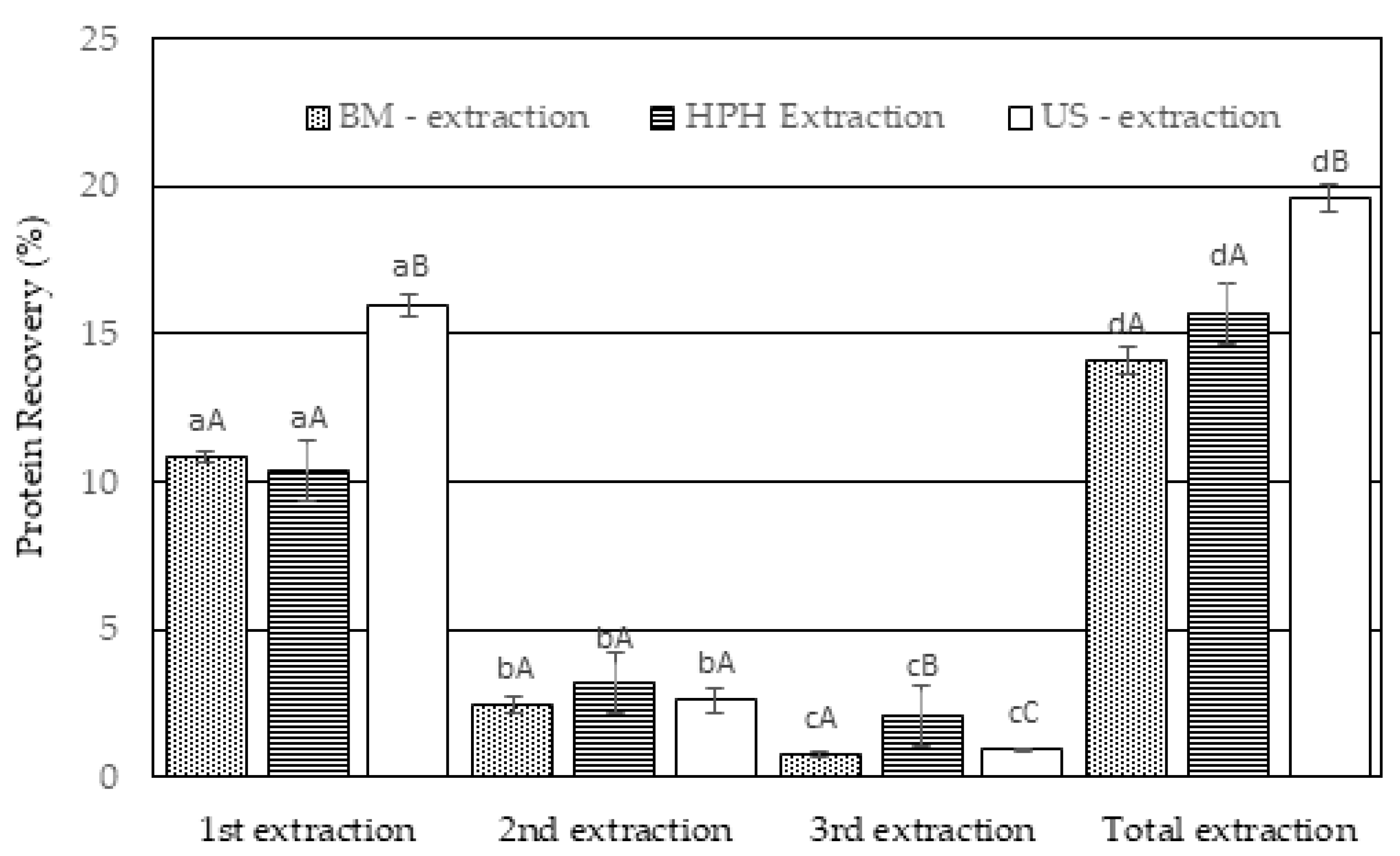

- Evaluation of the cell disruption level through the amount of extracted soluble protein

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waghmare, A.G.; Salve, M.K.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Arya, S.S. Concentration and Characterization of Microalgae Proteins from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2016, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Hegde, A.S.; Sharma, K.; Parmar, P.; Srivatsan, V. Microalgae as a Sustainable Source of Edible Proteins and Bioactive Peptides – Current Trends and Future Prospects. Food Research International 2022, 157, 111338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, M.E.T.D.; Correa, K.D.P.; Martins, M.A.; Da Matta, S.L.P.; Martino, H.S.D.; Coimbra, J.S.D.R. Food Safety, Hypolipidemic and Hypoglycemic Activities, and in Vivo Protein Quality of Microalga Scenedesmus Obliquus in Wistar Rats. Journal of Functional Foods 2020, 65, 103711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S.; Koley, H.; Dutta, S.; Bhowal, J. Hypocholesterolemic Effect of Spirulina Platensis (SP) Fortified Functional Soy Yogurts on Diet-Induced Hypercholesterolemia. Journal of Functional Foods 2018, 48, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigagli, E.; Cinci, L.; Niccolai, A.; Tredici, M.R.; Biondi, N.; Rodolfi, L.; Lodovici, M.; D’Ambrosio, M.; Mori, G.; Luceri, C. Safety Evaluations and Lipid-Lowering Activity of an Arthrospira Platensis Enriched Diet: A 1-Month Study in Rats. Food Research International 2017, 102, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niccolai, A.; Bigagli, E.; Biondi, N.; Rodolfi, L.; Cinci, L.; Luceri, C.; Tredici, M.R. In Vitro Toxicity of Microalgal and Cyanobacterial Strains of Interest as Food Source. J Appl Phycol 2017, 29, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, M.-C.; Sahebkar, A.; Dragan, S.; Stoichescu-Hogea, G.; Ursoniu, S.; Andrica, F.; Banach, M. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Spirulina Supplementation on Plasma Lipid Concentrations. Clinical Nutrition 2016, 35, 842–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, E.W. Microalgae for Human and Animal Nutrition. In Handbook of Microalgal Culture; Richmond, A., Hu, Q., Eds.; Wiley, 2013; pp. 461–503. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, L.; Ebert, S.; Hinrichs, J.; Weiss, J. Effect of Precipitation, Lyophilization, and Organic Solvent Extraction on Preparation of Protein-Rich Powders from the Microalgae Chlorella Protothecoides. Algal Research 2018, 29, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günerken, E.; D’Hondt, E.; Eppink, M.H.M.; Garcia-Gonzalez, L.; Elst, K.; Wijffels, R.H. Cell Disruption for Microalgae Biorefineries. Biotechnology Advances 2015, 33, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delran, P.; Frances, C.; Peydecastaing, J.; Pontalier, P.-Y.; Guihéneuf, F.; Barthe, L. Cell Destruction Level and Metabolites Green-Extraction of Tetraselmis Suecica by Low and Intermediate Frequency Ultrasound. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 98, 106492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Nobre, B.P.; Santos, J.A.L.; Lopes Da Silva, T.; Reis, A. Direct Lipid and Carotenoid Extraction from Rhodosporidium Toruloides Broth Culture after High Pressure Homogenization Cell Disruption: Strategies, Methodologies, and Yields. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2022, 189, 108712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, M.L.; Soares, J.; Vieira, B.B.; Batista-Silva, W.; Martins, M.A. Extraction of Proteins from the Microalga Scenedesmus Obliquus BR003 Followed by Lipid Extraction of the Wet Deproteinized Biomass Using Hexane and Ethyl Acetate. Bioresource Technology 2020, 307, 123190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Grimi, N.; Marchal, L.; Lebovka, N.; Vorobiev, E. Effect of Ultrasonication, High Pressure Homogenization and Their Combination on Efficiency of Extraction of Bio-Molecules from Microalgae Parachlorella Kessleri. Algal Research 2019, 40, 101524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Biotechnology and Applied Phycology, 1st ed.; Richmond, A., Ed.; Wiley, 2003; ISBN 978-0-632-05953-9. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, B.B.; Soares, J.; Amorim, M.L.; Bittencourt, P.V.Q.; De Cássia Superbi, R.; De Oliveira, E.B.; Dos Reis Coimbra, J.S.; Martins, M.A. Optimized Extraction of Neutral Carbohydrates, Crude Lipids and Photosynthetic Pigments from the Wet Biomass of the Microalga Scenedesmus Obliquus BR003. Separation and Purification Technology 2021, 269, 118711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covell, L.; Machado, M.; Vaz, M.G.M.V.; Soares, J.; Batista, A.D.; Araújo, W.L.; Martins, M.A.; Nunes-Nesi, A. Alternative Fertilizer-Based Growth Media Support High Lipid Contents without Growth Impairment in Scenedesmus Obliquus BR003. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2020, 43, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha, R.P.; Machado, M.; Vaz, M.G.M.V.; Vinson, C.C.; Leite, M.; Richard, R.; Mendes, L.B.B.; Araujo, W.L.; Caldana, C.; Martins, M.A.; et al. Exploring the Metabolic and Physiological Diversity of Native Microalgal Strains (Chlorophyta) Isolated from Tropical Freshwater Reservoirs. Algal Research 2017, 28, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Carmo Cesário, C.; Soares, J.; Cossolin, J.F.S.; Almeida, A.V.M.; Bermudez Sierra, J.J.; De Oliveira Leite, M.; Nunes, M.C.; Serrão, J.E.; Martins, M.A.; Dos Reis Coimbra, J.S. Biochemical and Morphological Characterization of Freshwater Microalga Tetradesmus Obliquus (Chlorophyta: Chlorophyceae). Protoplasma 2022, 259, 937–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Official Methods of Analysis, 18th ed.Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J Biol Chem 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afify, A.E.-M.M.R.; El Baroty, G.S.; El Baz, F.K.; Abd El Baky, H.H.; Murad, S.A. Scenedesmus Obliquus: Antioxidant and Antiviral Activity of Proteins Hydrolyzed by Three Enzymes. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2018, 16, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, A.; Tomas, H.; Havli, J.; Olsen, J.V.; Mann, M. In-Gel Digestion for Mass Spectrometric Characterization of Proteins and Proteomes. Nat Protoc 2006, 1, 2856–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.E.T.D.; Leal, M.A.; Resende, M.D.O.; Martins, M.A.; Coimbra, J.S.D.R. Scenedesmus Obliquus Protein Concentrate: A Sustainable Alternative Emulsifier for the Food Industry. Algal Research 2021, 59, 102468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shene, C.; Monsalve, M.T.; Vergara, D.; Lienqueo, M.E.; Rubilar, M. High Pressure Homogenization of Nannochloropsis Oculata for the Extraction of Intracellular Components: Effect of Process Conditions and Culture Age. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gminski, R.; Decker, K.; Heinz, C.; Seidel, A.; Könczöl, M.; Goldenberg, E.; Grobéty, B.; Ebner, W.; Gieré, R.; Mersch-Sundermann, V. Genotoxic Effects of Three Selected Black Toner Powders and Their Dimethyl Sulfoxide Extracts in Cultured Human Epithelial A549 Lung Cells in Vitro. Environ Mol Mutagen 2011, 52, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebrough, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. PROTEIN MEASUREMENT WITH THE FOLIN PHENOL REAGENT. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjos, L.; Estêvão, J.; Infante, C.; Mantecón, L.; Power, D.M. Extracting Protein from Microalgae (Tetraselmis Chuii) for Proteome Analysis. MethodsX 2022, 9, 101637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegewald, E.; Wolf, M. Phylogenetic Relationships of Scenedesmus and Acutodesmus (Chlorophyta, Chlorophyceae) as Inferred from 18S rDNA and ITS-2 Sequence Comparisons. Plant Systematics and Evolution 2003, 241, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, V.S.; De Oliveira, D.R.B.; Da Silva, C.A.S.; Santana, R.D.C.; Soares, N.D.F.F.; De Oliveira, E.B.; Martins, M.A.; Coimbra, J.S.D.R. Stabilization of Oil–Water Emulsions with Protein Concentrates from the Microalga Tetradesmus Obliquus. J Food Sci Technol 2023, 60, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.L.; Reis, A.; Duarte, L.C.; Carvalheiro, F. Effective Fractionation of Microalgae Biomass as an Initial Step for Its Utilization as a Bioenergy Feedstock. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2022, 16, 100317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzfeier, A.; Wierenga, P.A.; Gruppen, H. Isolation and Characterization of Soluble Protein from the Green Microalgae Tetraselmis Sp. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 9121–9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wang, Q.; Xin, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xu, J. Enhancing Photosynthetic Biomass Productivity of Industrial Oleaginous Microalgae by Overexpression of RuBisCO Activase. Algal Research 2017, 27, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mello, R.V.; Meccheri, F.S.; Bagatini, I.L.; Rodrigues-Filho, E.; Vieira, A.A.H. MALDI-TOF MS Based Discrimination of Coccoid Green Microalgae (Selenastraceae, Chlorophyta). Algal Research 2017, 28, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irrgang, A.; Weise, C.; Murugaiyan, J.; Roesler, U. Identification of Immunodominant Proteins of the Microalgae Prototheca by Proteomic Analysis. New Microbes and New Infections 2015, 3, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, H.; Ge, S.; Feng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, F.; Wen, P.; Wang, R. Influence of Temperature during Freeze-Drying Process on the Viability of Bifidobacterium Longum BB68S. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balasundaram, B.; Skill, S.C.; Llewellyn, C.A. A Low Energy Process for the Recovery of Bioproducts from Cyanobacteria Using a Ball Mill. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2012, 69, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, F.; Pietzsch, M.; Müller, R.; Syldatk, C. Mechanical Disruption of Arthrobacter Sp. DSM 3747 in Stirred Ball Mills for the Release of Hydantoin-Cleaving Enzymes. Chemical Engineering Science 1992, 47, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüler, L.M.; Santos, T.; Pereira, H.; Duarte, P.; Katkam, N.G.; Florindo, C.; Schulze, P.S.C.; Barreira, L.; Varela, J.C.S. Improved Production of Lutein and β-Carotene by Thermal and Light Intensity Upshifts in the Marine Microalga Tetraselmis Sp. CTP4. Algal Research 2020, 45, 101732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azencott, H.R.; Peter, G.F.; Prausnitz, M.R. Influence of the Cell Wall on Intracellular Delivery to Algal Cells by Electroporation and Sonication. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 2007, 33, 1805–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Rouquié, C.; Lavenant, L.; Frappart, M.; Couallier, E. Coupling Bead-Milling and Microfiltration for the Recovery of Lipids and Proteins from Parachlorella Kessleri: Impact of the Cell Disruption Conditions on the Separation Performances. Separation and Purification Technology 2022, 287, 120570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiden, E.M.; Scales, P.J.; Kentish, S.E.; Martin, G.J.O. Critical Analysis of Quantitative Indicators of Cell Disruption Applied to Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Processed with an Industrial High Pressure Homogenizer. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2013, 70, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safi, C.; Ursu, A.V.; Laroche, C.; Zebib, B.; Merah, O.; Pontalier, P.-Y.; Vaca-Garcia, C. Aqueous Extraction of Proteins from Microalgae: Effect of Different Cell Disruption Methods. Algal Research 2014, 3, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, P.S.; Morais Júnior, W.G.; Martins, A.A.; Caetano, N.S.; Mata, T.M. Microalgae Biomolecules: Extraction, Separation and Purification Methods. Processes 2020, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Sierra, L.; Stoykova, P.; Nikolov, Z.L. Extraction and Fractionation of Microalgae-Based Protein Products. Algal Research 2018, 36, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Fernández, C.; Sialve, B.; Bernet, N.; Steyer, J.P. Comparison of Ultrasound and Thermal Pretreatment of Scenedesmus Biomass on Methane Production. Bioresource Technology 2012, 110, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Zhang, D.; Parajuli, K.; Upadhyay, S.; Jiang, Y.; Duan, Z. Comparison of Four Quantitative Techniques for Monitoring Microalgae Disruption by Low-Frequency Ultrasound and Acoustic Energy Efficiency. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3295–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupatini, A.L.; De Oliveira Bispo, L.; Colla, L.M.; Costa, J.A.V.; Canan, C.; Colla, E. Protein and Carbohydrate Extraction from S. Platensis Biomass by Ultrasound and Mechanical Agitation. Food Research International 2017, 99, 1028–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keris-Sen, U.D.; Sen, U.; Soydemir, G.; Gurol, M.D. An Investigation of Ultrasound Effect on Microalgal Cell Integrity and Lipid Extraction Efficiency. Bioresource Technology 2014, 152, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, L.S.; Dixon, C.K.; Wilken, L.R. Enzymatic Cell Disruption of the Microalgae Chlamydomonas Reinhardtii for Lipid and Protein Extraction. Algal Research 2017, 25, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsimichas, A.; Karveli, I.; Dimopoulos, G.; Giannakourou, M.; Taoukis, P. Kinetics of High Pressure Homogenization Assisted Protein Extraction from Chlorella Pyrenoidosa. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2023, 88, 103438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Ball mill | High-pressurehomogenization | Ultrasound |

| Protein mass yield (g/100 g) | 16.1 ± 1.3a | 17.1 ± 1.4b | 20.8 ± 0.8a |

| % Protein content (g/100 g) | 29.7 ± 1.2a | 29.1 ± 0.6a | 30.7 ± 0.4b |

| L* | 46.4 ± 0.46a | 52.0 ± 0.76c | 46.1 ± 0.26a |

| A | 4.73 ± 0.11a | 5.53 ± 0.17c | 4.98 ± 0.096b |

| B | 13.6 ± 0.40a | 17.6 ± 0.30c | 11.8 ± 0.29b |

| Visual appearance |  |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).