1. Introduction

Steel bridges constitute the backbone of modern transportation networks, facilitating economic activity and social connectivity. However, these critical infrastructure elements are continuously subjected to a complex interplay of degrading factors, including repetitive traffic loads, environmental stressors such as temperature fluctuations and corrosion, and potentially extreme events like earthquakes and typhoons. The aging of bridge infrastructure portfolios worldwide, with a significant proportion rated as fair or poor, underscores the urgent need for effective condition assessment and maintenance strategies (Rizzo and Enshaeian 2021). The catastrophic consequences of bridge failures, both in terms of human safety and economic disruption, highlight the non-negotiable imperative for ensuring structural integrity throughout a bridge's operational lifetime.

Structural Health Monitoring (SHM) has emerged as a vital field dedicated to addressing this imperative. It can be defined as the process of implementing a damage detection and characterization strategy for engineering structures (Farrar and Worden 2007). In the specific context of steel bridges, SHM involves the use of an array of sensing technologies, data acquisition systems, and analytical tools to monitor the condition of the structure in real-time or near-real-time. The primary objectives are to identify the onset of damage, locate its position, assess its severity, and in advanced systems, predict the remaining useful life of the structure. This moves maintenance philosophy from a reactive or scheduled-based model to a condition-based and ultimately predictive paradigm, optimizing resource allocation and enhancing safety (Balageas et al. 2010).

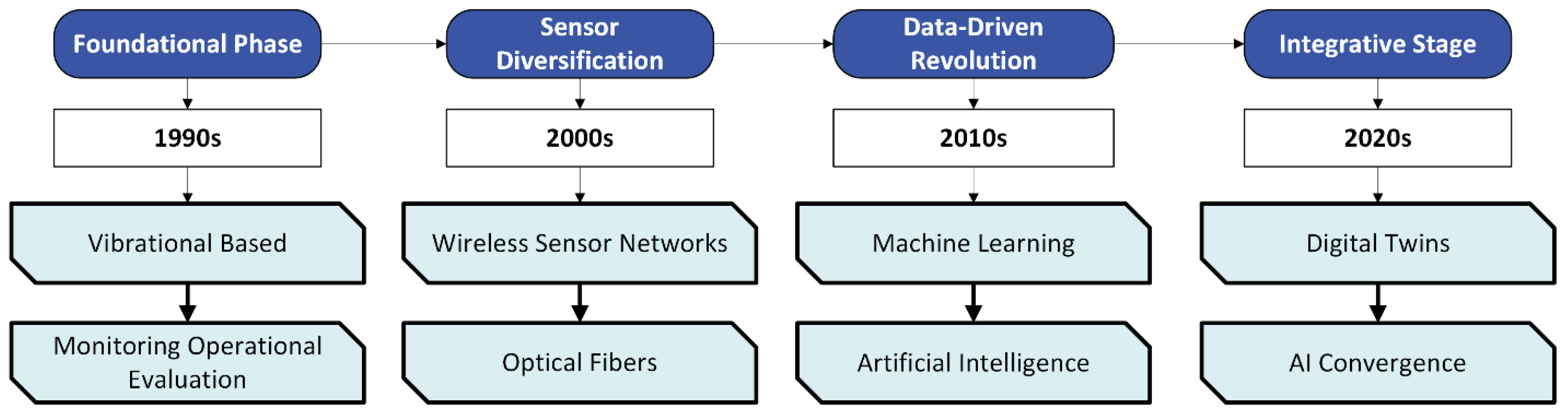

The field of SHM has historically concentrated on techniques to identify damage within various structures, including steel bridges, over the past three decades (Farrar and Worden 2007). This focus has led to the development of fundamental methodologies that support current SHM practices, guiding the early detection of structural issues before they become severe. The evolution of SHM for steel bridges has been significantly influenced by early literature, which laid the groundwork for current advancements. Between 1996 and 2001, a comprehensive review highlighted the importance of operational evaluation and data acquisition, emphasizing the necessity for robust statistical pattern recognition to transition SHM from theoretical frameworks to practical applications (Sohn et al. 2003). This period marked a critical phase where researchers began to systematically capture and analyze data, enabling more reliable feature extraction and statistical modeling for real-world conditions. Despite the advancements, the literature identified a gap in the rigorous application of these techniques, often limiting the technology's deployment beyond controlled environments (Sohn et al. 2003). Addressing these gaps has been crucial in refining SHM methodologies, ultimately enhancing the precision and effectiveness of damage detection in steel bridge structures, which remains a priority for ensuring long-term infrastructure resilience.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of structure health monitoring between 1990s and 2002s.

This literature review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the state-of-the-art in SHM for steel bridges. It will explore the historical progression of the field, detail the core technologies for sensing and data acquisition, critically analyze advanced data interrogation methods including machine learning and statistical models, and examine specific applications for damage detection. Furthermore, the review will synthesize the key challenges facing widespread implementation and outline future directions for research and development. By consolidating insights from a broad range of studies, this paper seeks to offer a clear overview of how SHM technologies are transforming the management and preservation of steel bridge infrastructure.

2. The Evolution of SHM: From Foundational Principles to an Integrated Discipline

The journey of Structural Health Monitoring from a niche research topic to a multidisciplinary engineering field reflects a consistent drive towards more automated, accurate, and comprehensive assessment systems. This evolution can be charted through key developmental phases, from establishing core principles to the current integration of advanced computational intelligence.

2.1. The Formative Decade: Establishing the SHM Paradigm

The foundational period of SHM, particularly the late 1990s and early 2000s, was characterized by efforts to systematize the damage detection process. The First International Workshop on Structural Health Monitoring in 1999 served as a pivotal forum, highlighting the integration of advanced sensors and signal processing techniques as being crucial for enhancing detection capabilities (Chang 1999). This era focused on establishing SHM as a legitimate field of study, moving away from ad-hoc inspections towards a structured paradigm. The core components of this paradigm were crystallized in reviews of the time, which emphasized the sequential process of operational evaluation, data acquisition, feature extraction, and statistical modeling (Sohn et al. 2003). Operational evaluation involved defining the potential damage scenarios and the environmental conditions under which the structure operated. Data acquisition concerned the selection and placement of sensors to capture relevant structural responses. This was followed by feature extraction, where measured data was condensed into key indicators sensitive to damage, and finally, statistical modeling to distinguish between the undamaged and damaged states of the structure. This structured approach provided a much-needed framework for researchers and practitioners, setting the stage for more standardized methodologies. However, a significant challenge identified during this period was the gap between theoretical development and practical application. The rigorous application of these techniques was often lacking, limiting the technology's deployment beyond controlled laboratory settings (Sohn et al. 2003). This highlighted the need for robust, real-world validation of SHM systems.

2.2. Technological Diversification: Expanding the Sensor and Data Acquisition Toolkit

As the foundational principles solidified, the field experienced a period of rapid technological diversification. Research expanded beyond traditional vibration monitoring to incorporate a wider array of sensing modalities. The integration of vibration and modal analysis provided critical insights into the dynamic behavior of bridge structures, identifying potential vulnerabilities that could signify early stages of damage (Balageas et al. 2010). Simultaneously, optical fiber sensing emerged with its high sensitivity and ability to cover large areas, enhancing the detection of strain and deformation and offering a more comprehensive monitoring solution for vast bridge networks (Balageas et al. 2010). Furthermore, the use of acousto-ultrasonics through piezoelectric transducers enabled precise localization of defects, further refining the diagnostic capabilities of SHM systems (Balageas et al. 2010).

A pivotal advancement during this period was the move towards wireless sensing. The deployment of wireless sensor networks (WSNs) revolutionized the assessment of steel bridge conditions by facilitating continuous and autonomous data collection (Balageas et al. 2010; Lynch 2007). These networks allowed for the integration of various sensor types, including accelerometers and strain gauges, to measure dynamic responses and environmental factors affecting structural integrity. By leveraging WSNs, real-time data transmission became feasible, significantly reducing processing delays and enhancing the timeliness of maintenance decisions (Balageas et al. 2010). The scalability of wireless sensor networks also permitted extensive monitoring coverage, enabling engineers to conduct comprehensive evaluations without the logistical challenges and high costs associated with traditional wired systems (Lynch 2007). This period also saw the development of "smart sensors," such as the Intel Imote2, which embedded computational capabilities at the node level, enabling real-time measurement of structural vibration responses and other critical physical phenomena directly on the sensor (Nagayama and Spencer 2007). The incorporation of middleware services for data aggregation and synchronized sensing made these SHM systems not only scalable but also extensible, allowing for efficient management across various bridge types and sizes (Nagayama and Spencer 2007).

2.3. The Data-Driven Revolution: The Rise of Machine Learning and AI

The proliferation of sensing technologies generated an explosion of data, which in turn catalyzed the third major phase in the evolution of SHM: the data-driven revolution. The potential of machine learning in SHM gained momentum as an innovative approach to enhance the analysis and interpretation of data collected from steel bridges (Rizzo and Enshaeian 2021; Worden and Manson 2007). By employing advanced algorithms capable of handling large datasets, machine learning models could uncover complex patterns and predict future structural behaviors with remarkable accuracy (Rizzo and Enshaeian 2021). This integrated methodology, which coupled measurement hardware with sophisticated data interrogation algorithms, enhanced the accuracy of anomaly detection by applying statistical pattern recognition techniques that were learned from vast datasets to predict potential failures (Farrar and Worden 2012).

The synergy between hardware and advanced algorithms facilitated the development of predictive maintenance strategies, ensuring that interventions were timely and well-informed (Farrar and Worden 2012). Moreover, this approach supported the customization of SHM systems to address specific bridge conditions, leveraging machine learning's adaptability to accommodate diverse structural and environmental variables (Farrar and Worden 2012). As research in this area expanded, machine learning stood poised to transform conventional SHM practices, offering robust solutions for the long-term preservation of steel bridge networks (Sohn et al. 2003). This evolution has now progressed to the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and big data (BD), which allow for the processing of vast amounts of unstructured data, enhancing the precision of visual inspections and facilitating the detection of structural damage through sophisticated time series analysis (Sun et al. 2020). The establishment of a BD-oriented SHM framework, supported by advanced computing techniques and deep learning, has laid the groundwork for a new paradigm where systems can autonomously identify and predict potential issues, paving the way for future innovations in bridge maintenance and safety (Sun et al. 2020).

3. Sensing and Data Acquisition Technologies

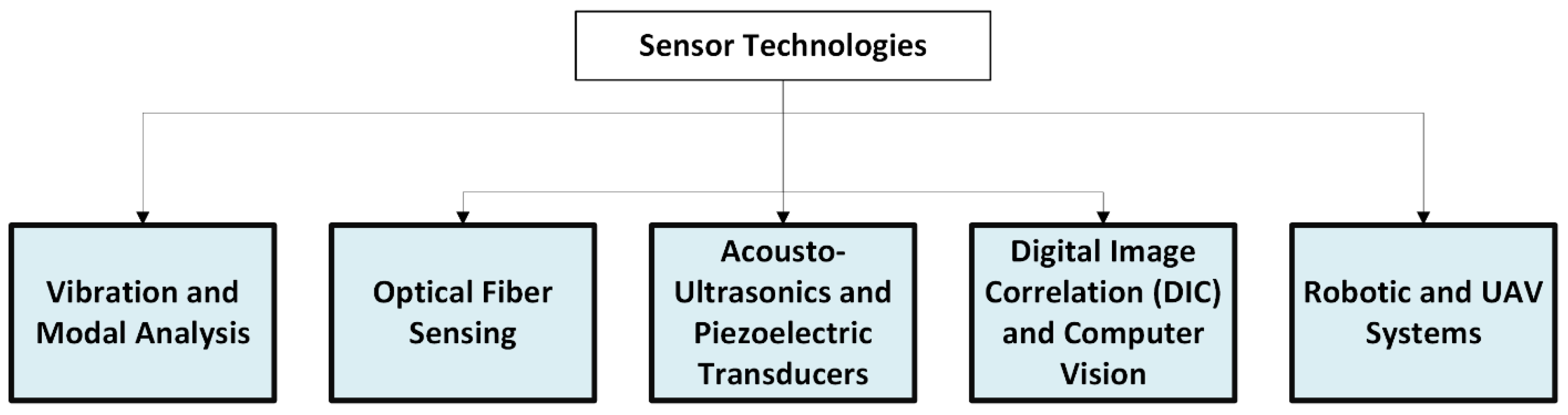

The efficacy of any Structural Health Monitoring system is fundamentally rooted in its ability to accurately capture the physical state of the structure. This has led to the development and deployment of a diverse suite of sensing technologies, each with unique advantages for monitoring different aspects of steel bridge behavior. The transition from traditional wired systems to advanced wireless and non-contact methods represents a significant leap forward in the practicality and scope of SHM, see

Figure 2.

3.1. Wired versus Wireless Sensor Networks

Traditional SHM systems relied heavily on wired sensors, which presented significant challenges in terms of installation cost, cabling complexity, and long-term maintenance, especially for large-scale structures like bridges (Lynch 2007). The advent of wireless smart sensor networks (WSSNs) has addressed many of these limitations, heralding a new era in civil infrastructure maintenance. These low-cost wireless sensing units offer a cost-effective solution for real-time data acquisition, enabling comprehensive analysis of structural integrity without the prohibitive expenses linked to traditional wired systems (Lynch 2007). By employing wireless technology, SHM systems can be deployed more widely and flexibly, allowing for the continuous monitoring of steel bridges under various environmental conditions.

Wireless smart sensor networks utilize sophisticated AI resources for data prediction and diagnosis, allowing for continuous monitoring without the need for extensive cabling or manual data retrieval (Sofi et al. 2022). By measuring vibrational responses, these sensors can detect alterations in mass, stiffness, and damping values, providing critical insights into the structural integrity of bridges. The deployment of dense sensor arrays enhances the system's damage detection capabilities, ensuring that even subtle structural deficiencies are identified and addressed promptly (Nagayama and Spencer 2007). The real-time data transmission capability of WSNs significantly reduces processing delays, enhancing the timeliness of maintenance decisions (Balageas et al. 2010). However, the real-world application of wireless sensor networks in SHM systems still faces challenges, particularly in standardizing protocols to bridge the gap between academic research and practical deployment (Sofi et al. 2022). Issues such as power management, data security, and reliable communication in the harsh electromagnetic environment of a bridge site are active areas of research. Despite these challenges, as these issues are addressed, wireless smart sensor networks promise to significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of SHM systems, contributing to safer and more durable bridge infrastructures (Sofi et al. 2022).

3.2. Diverse Sensing Modalities for Comprehensive Assessment

No single sensor type can capture the full spectrum of a bridge's structural response. Therefore, a modern SHM system often integrates multiple sensing modalities to form a comprehensive assessment framework.

Vibration and Modal Analysis: This is one of the most established techniques in SHM (Alshalal et al. 2019; Salama et al. 2025). It involves using accelerometers to measure the dynamic response of a bridge to ambient loads like traffic or wind. The resulting data is used to identify modal parameters such as natural frequencies, mode shapes, and damping ratios. Changes in these global dynamic characteristics can indicate a loss of stiffness or other forms of damage (Balageas et al. 2010; Ko and Ni 2005). This approach is excellent for global health monitoring but may be less sensitive to small, localized damage.

Optical Fiber Sensing: Optical fiber sensors offer several distinct advantages, including immunity to electromagnetic interference, high sensitivity, and the ability to function as distributed sensors over long distances. They are particularly effective for monitoring strain and temperature gradients along the length of a bridge (Balageas et al. 2010). This makes them ideal for detecting deformation, cracking, and assessing the effects of thermal loads on large-scale steel bridges.

Acousto-Ultrasonics and Piezoelectric Transducers: This technique typically uses networks of piezoelectric transducers that can act as both actuators and sensors. One transducer generates a high-frequency stress wave, and others detect the wave after it has passed through the structure. Damage, such as cracks or corrosion, alters the wave's propagation characteristics (e.g., time of flight, amplitude, frequency content), allowing for its detection and localization (Balageas et al. 2010). This method is highly sensitive to local damage and is often used for critical connection details.

Digital Image Correlation (DIC) and Computer Vision: DIC has emerged as a significant non-contact advancement in SHM, offering a high-resolution method to assess structural integrity (Ngeljaratan and Moustafa 2020). This technique involves using target-tracking or natural texture to capture real-time dynamic behavior, allowing for precise measurement of full-field deformation and modal properties under various loads. In controlled laboratory environments, DIC has demonstrated its efficacy by accurately monitoring the response of bridge structures to bidirectional earthquake shaking, providing results comparable to traditional instrumentation (Ngeljaratan and Moustafa 2020). Furthermore, field applications have shown DIC's capability in determining vibration frequencies and detecting anomalies in structural performance.

The integration of computer vision, particularly through Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), offers a transformative approach to bridge diagnostics, especially for visual inspection tasks (Marchewka et al. 2020). By utilizing UAVs equipped with advanced image processing capabilities, this method significantly reduces the costs and complexities associated with traditional monitoring techniques. The system focuses on identifying visual markers, such as corrosion and rivet displacement, which are critical indicators of structural deterioration in steel truss bridges (Marchewka et al. 2020). This innovative approach not only facilitates more frequent inspections but also enhances the precision of condition assessments, ensuring timely maintenance interventions. The fusion of sensor technology with computer vision allows for more accurate and comprehensive monitoring of bridge conditions, facilitating real-time data collection and processing and enabling early warning systems to identify anomalies before they evolve into critical problems (Deng et al. 2023).

3.3. Advanced Platforms for Data Collection: Robotic and UAV Systems

Beyond fixed sensors, the integration of intelligent robotic systems represents another frontier in SHM technology advancement (Tian et al. 2022). These systems, which include mobile robots, wall-climbing robots, and flying drones, are specifically designed to conduct comprehensive inspections and gather dynamic response data from bridges. Their ability to traverse challenging terrains and access hard-to-reach areas enhances the thoroughness of inspections, particularly in detecting surface and subsurface defects (Tian et al. 2022). Moreover, the versatility and adaptability of multimodal robotic systems promise significant improvements in modal identification and cable tension force estimation, crucial for maintaining bridge integrity. As these robotic technologies evolve, they are expected to complement existing SHM frameworks, offering a robust, efficient, and scalable solution for ongoing bridge maintenance and safety enhancement efforts, particularly for detailed, localized inspections that may not justify a permanent sensor installation.

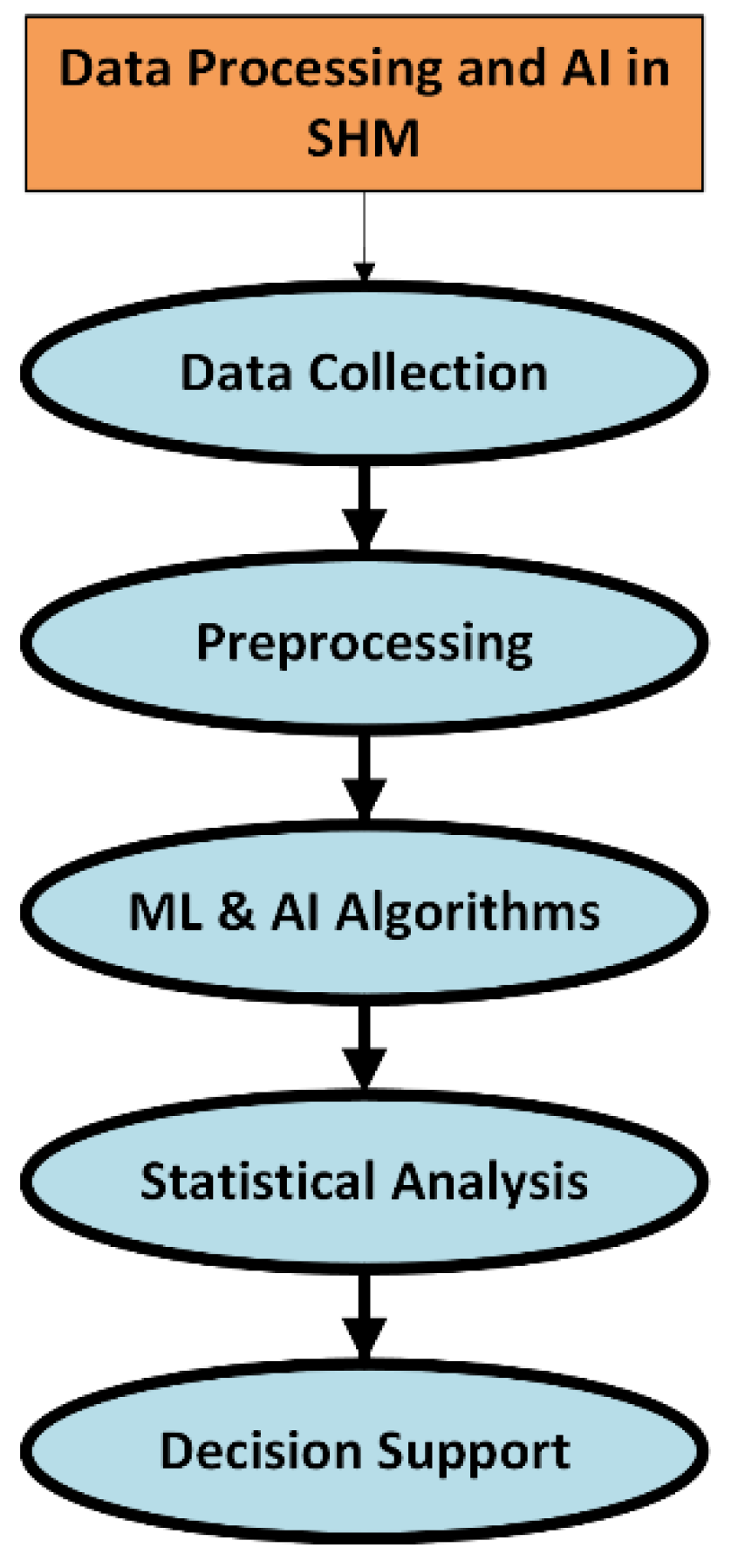

4. Data Interrogation, Analysis, and Computational Intelligence

The vast and often complex data streams generated by modern sensor networks are of little use without sophisticated methods for analysis and interpretation. The transition from simple data visualization to advanced computational intelligence represents the "brain" of modern SHM systems, transforming raw data into actionable knowledge.

Figure 3 shows an SHM data pipeline: collect raw measurements, clean and normalize them, apply ML/AI models, evaluate results statistically, and convert insights into decision support for maintenance and operations.

4.1. The Paradigm Shift to Data-Driven Methodologies

A fundamental shift in SHM has been the move from purely model-based approaches to data-driven methodologies. Model-based methods rely on creating a detailed finite element model of the steel bridge and updating it to match measured data, which can be computationally expensive and sensitive to modeling errors. Data-driven methods, in contrast, leverage the data itself to build statistical or machine learning models that can detect damage without an explicit physical model of the structure. A recent study demonstrated the efficacy of employing experimental data to develop statistical models capable of detecting both local and global structural damage (Svendsen et al. 2022). This approach allows for the identification of damage patterns that might otherwise go unnoticed in traditional monitoring frameworks, thereby improving the preventative maintenance strategies for existing bridge infrastructures. By leveraging comprehensive investigations of common steel bridge damages, these methodologies provide a robust foundation for damage detection, ensuring that SHM systems are equipped to address the nuanced challenges posed by varying structural conditions (Svendsen et al. 2022). As these data-driven techniques continue to gain traction, they promise to refine the precision and reliability of SHM systems, ultimately contributing to more informed decision-making processes in infrastructure management.

4.2. Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence in SHM

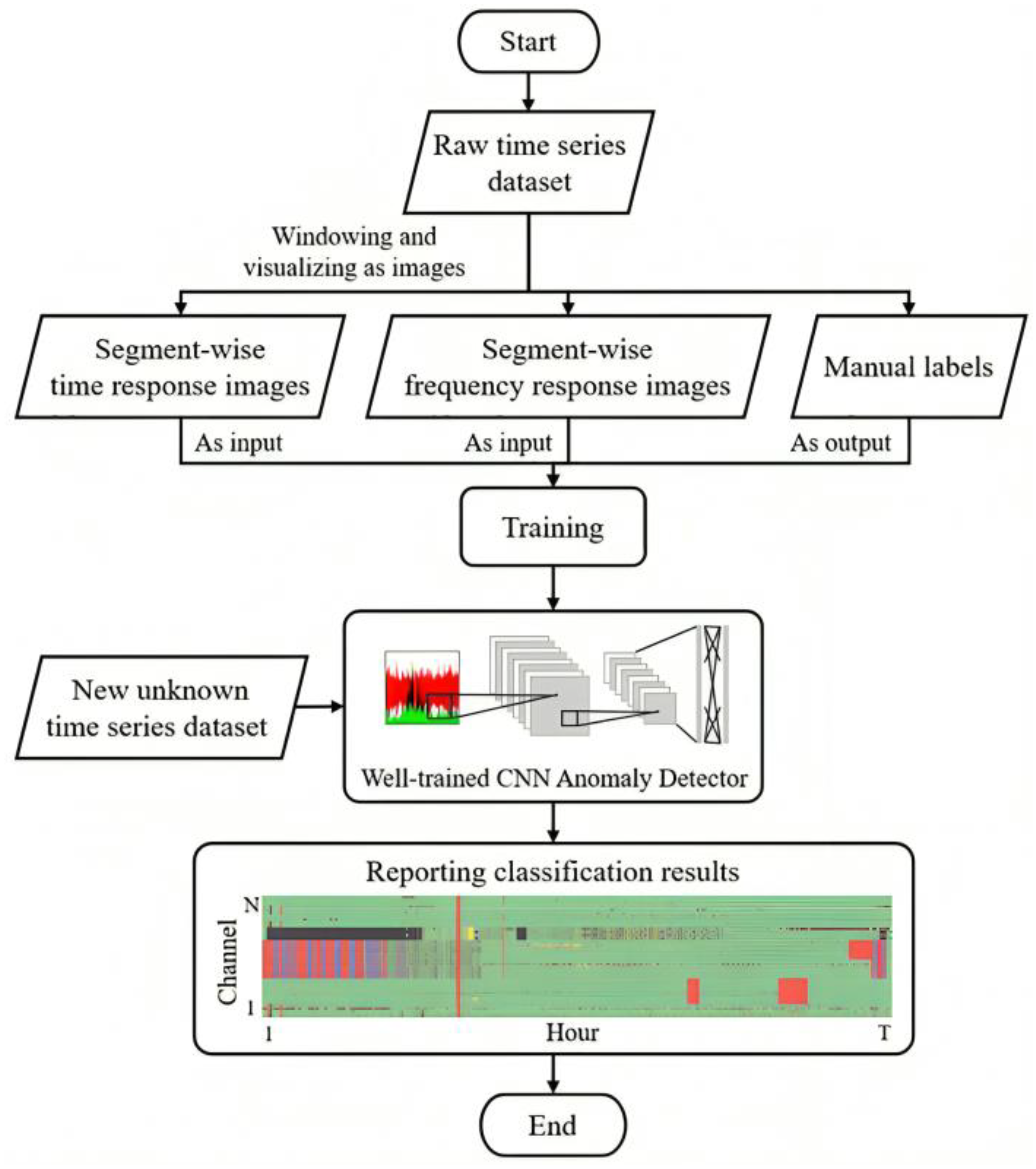

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are the cornerstones of the data-driven revolution in SHM, offering transformative approaches to enhance the assessment capabilities for steel bridges (Azad et al. 2024; Bao and Li 2021; Gordan et al. 2022; Kot et al. 2021; Kumar and Kota 2024; Luleci et al. 2022; Xu et al. 2023). As an example, anomalous data detection which is very important for an automatic intelligent SHM system because otherwise, the SHM system may mistakenly process the erroneous data as the data from extreme events and create a false warning (Bao and Li 2021). Bao and Li proposed anomalous data detection procedure that transformed anomalous data diagnosis to an image classification problem that can be analyzed by deep learning network,

Figure 4.

Knowledge-Driven versus Data-Driven AI Approaches: The integration of AI into SHM can be broadly categorized into two paradigms. Knowledge-driven AI approaches, noted for their interpretability and stability, offer a robust framework for understanding complex structural behaviors but are often constrained by their limited adaptability to novel situations (Wan et al. 2023). Conversely, data-driven AI methods excel in efficiency and accuracy, rapidly processing vast datasets to detect anomalies and predict structural performance changes, yet they occasionally falter due to instability in dynamic environments and their "black-box" nature (Wan et al. 2023). To mitigate these challenges, a hybrid knowledge-data-driven approach is proposed, leveraging the strengths of both methodologies to enhance reliability and safety in practical SHM applications. This synergy not only improves diagnostic precision but also facilitates adaptive learning, enabling the SHM systems to evolve alongside the structures they monitor, thus ensuring long-term structural safety and resilience (Wan et al. 2023).

Specific Machine Learning Algorithms and their Applications: Various ML algorithms have been successfully applied to SHM tasks. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), for instance, have proven highly effective in image-based analysis, identifying specific issues such as steel corrosion and concrete cracks from visual data (Xu et al. 2023). Meanwhile, recurrent neural networks (RNNs) offer promising advancements in predicting direct structural responses from time-series data, such as acceleration or strain measurements, thereby improving the accuracy of health assessments over time (Xu et al. 2023). Unsupervised learning methods hold potential for streamlining data processing by automatically labeling training data, which could significantly reduce the time and effort required for manual data categorization (Xu et al. 2023). Other algorithms, including artificial neural networks (ANN) and support vector machines (SVM), are used for hierarchical classification of damage levels, improving decision-making processes for maintenance and repair (Gomez-Cabrera and Escamilla-Ambrosio 2022). The application of these algorithms, alongside sophisticated preprocessing techniques, facilitates the extraction of critical features and the management of uncertainties, which are crucial for accurate structural assessments (Gomez-Cabrera and Escamilla-Ambrosio 2022).

4.3. Statistical and Probabilistic Frameworks for Damage Assessment

While ML offers powerful pattern recognition, statistical and probabilistic methods provide a rigorous framework for dealing with the inherent uncertainties in SHM, such as varying environmental conditions and noise measurement.

Statistical Pattern Recognition and Time Series Analysis: The core of many SHM systems is statistical pattern recognition, which involves comparing features extracted from current data with a baseline model of the healthy structure (Farrar and Worden 2007, 2012). Advanced time series analysis is used to process long-term dynamic strain data, for example, to derive a standard daily stress spectrum that accounts for a variety of stressors such as highway and railway traffic (Ye et al. 2012). This comprehensive approach not only enhances the accuracy of fatigue life predictions but also facilitates the early diagnosis of potential weaknesses. Innovative approaches like unsupervised meta-learning address the complexities of managing large datasets and environmental variables (Entezami et al. 2023). This technique enhances the accuracy of damage detection by employing a locally unsupervised feature selection approach known as nearest cluster selection, alongside a robust Mahalanobis distance for effective anomaly detection. Such advancements are crucial, given the diverse environmental conditions that steel bridges often endure, which can obscure or mimic signs of structural stress.

Bayesian Methods for Uncertainty Quantification: Bayesian methods have become integral to enhancing SHM, particularly for assessing the condition of specific steel bridge components like expansion joints (Ni et al. 2020). These methods utilize long-term SHM data to develop probabilistic models that account for various uncertainties, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of bridge performance over time. By employing a Bayesian regression model alongside reliability theory, researchers can formulate a reliability-based anomaly index, which evaluates the probability of damage and issues alarms when necessary (Ni et al. 2020). This approach not only facilitates the prediction of potential failures but also improves the accuracy of damage detection by quantifying prediction uncertainties, thus ensuring timely maintenance interventions. This probabilistic framework is also valuable in fault detection methods for railway bridges, where Bayesian belief networks can refine the understanding of failure probabilities, enhancing decision-making processes for maintenance planning (Vagnoli et al. 2018).

4.4. Advanced Signal Processing Techniques: The Hilbert-Huang Transform

Beyond statistical and ML methods, advanced signal processing techniques offer unique tools for analyzing non-stationary and nonlinear data. The Hilbert-Huang Transform (HHT) presents a novel approach to SHM of steel bridges, offering significant advancements over traditional methods like Fourier analysis (Huang et al. 2005). By employing a nondestructive technique, the HHT-based method allows for continuous monitoring and real-time assessment of bridge conditions. This innovative approach enhances the precision of damage detection through its ability to decompose complex signals into intrinsic mode functions, providing detailed insights into the structural dynamics of bridges (Huang et al. 2005). The criteria for evaluating the structural health of bridges using HHT are well-defined, ensuring consistent and reliable assessments that can guide maintenance decisions. As SHM technologies advance, incorporating the HHT method promises to refine the accuracy and efficiency of monitoring practices, particularly for analyzing transient events and non-linear structural responses.

5. Specific Applications and Damage Detection Methodologies

The ultimate goal of any SHM system is to reliably detect and characterize damage. This involves applying the collected data and analytical techniques to address specific monitoring challenges, from global assessments of the entire structure to the health of individual components.

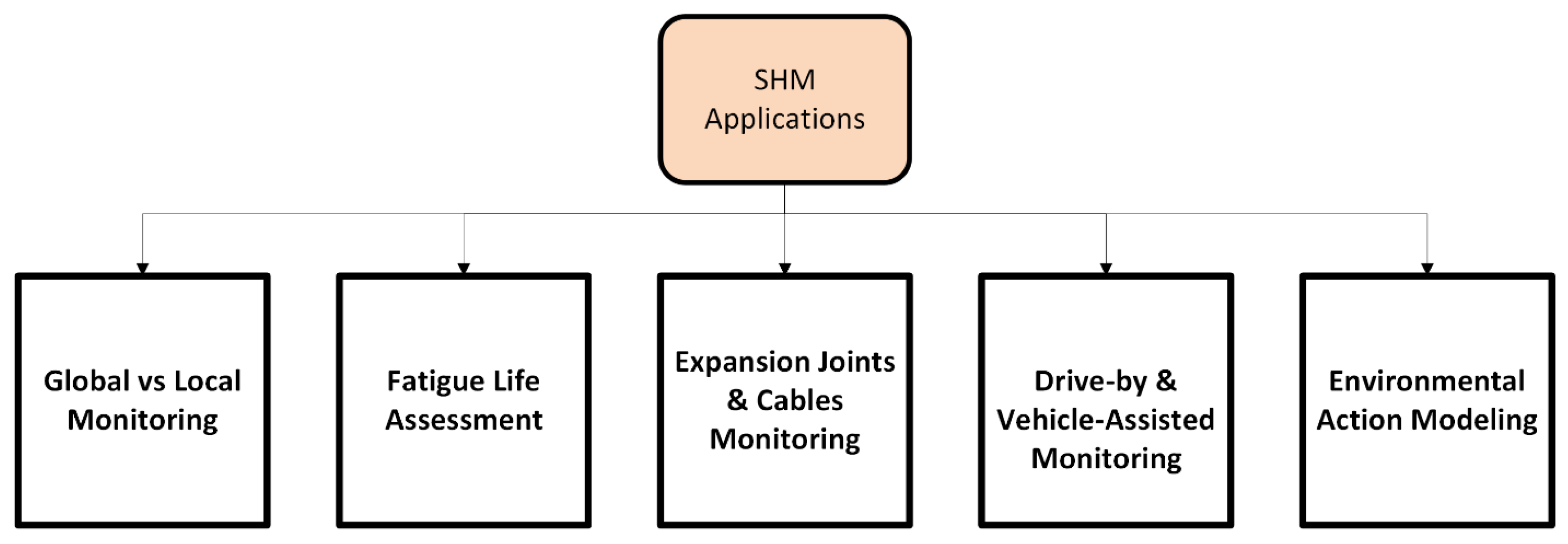

Figure 5 shows some of the SHM areas of applications including global and local monitoring, fatigue life assessment, expansion joints & cables monitoring, drive-by & vehicle-assisted monitoring and environmental action modeling.

5.1. Global versus Local Health Monitoring

SHM strategies can be broadly classified into global and local monitoring. Global health monitoring techniques assess the entire bridge structure for potential issues, typically by tracking changes in vibrational characteristics (Liu and Nayak 2012). This approach is effective for detecting significant damage that affects the overall stiffness or mass distribution of the steel bridge. However, it may be insensitive to small, localized damage. Local health monitoring, in contrast, focuses on specific critical areas, such as welded connections, fatigue-prone details, or expansion joints. Techniques like acousto-ultrasonics, detailed strain gauging, and close-range visual inspections using UAVs are employed for this purpose (Liu and Nayak 2012; Marchewka et al. 2020). By utilizing a combination of these methods, engineers can achieve a more complete understanding of a steel bridge's condition, thereby enhancing decision-making processes for maintenance and repair activities. The integration of advanced technologies ensures that both global integrity and local vulnerabilities are addressed within a comprehensive SHM framework.

5.2. Fatigue Life Assessment and Stress Spectrum Analysis

Fatigue is a primary degradation mechanism in steel bridges subjected to repetitive traffic loads (El-Sisi et al. 2020). The integration of statistical analysis into SHM systems refined the fatigue life assessment, allowing for more precise and reliable predictions of structural integrity (Ye et al. 2012). By analyzing long-term dynamic strain data, researchers can derive a standard daily stress spectrum that accounts for a variety of stressors such as highway and railway traffic, as well as environmental factors like typhoons. This comprehensive approach not only enhances the accuracy of fatigue life predictions but also facilitates the early diagnosis of potential weaknesses in critical components, such as welded details (Ye et al. 2012). The continuous monitoring of dynamic strain responses provides valuable insights that support the development of more robust maintenance strategies, ultimately improving the resilience and safety of bridge infrastructure. This data-driven approach to fatigue assessment moves beyond conservative design assumptions, providing a realistic picture of the actual accumulated damage throughout the bridge's life.

5.3. Monitoring of Specific Bridge Components: Expansion Joints and Cables

Certain bridge components are particularly vulnerable and require targeted monitoring. Expansion joints, for instance, are critical for accommodating thermal movements but are prone to damage from debris accumulation and impact loads (Mutnbak 2018; Mutnbak et al. 2021; Orton et al. 2015, 2017). Bayesian methods have been specifically tailored for condition assessment and damage alarm of bridge expansion joints using long-term SHM data (Ni et al. 2020). Similarly, in cable-stayed and suspension bridges, the cables and hangers are vital structural elements. The integration of environmental action modeling into SHM systems offers significant advancements in the precision of structural assessments for these components (Li et al. 2012). By incorporating data on temperature, sustained winds, and typhoon impacts, these models enable a more nuanced understanding of how environmental factors influence the internal forces within cables and hangers, which is vital for effective condition monitoring and early warning systems (Li et al. 2012).

5.4. Vehicle-Assisted and Drive-By Monitoring Techniques

A promising and innovative avenue in SHM is the use of vehicles as mobile sensing platforms. Vehicle-assisted techniques have emerged as a promising avenue in the SHM of steel bridges, offering innovative solutions through conventional and advanced methods (Shokravi et al. 2020). These techniques leverage the dynamic interaction between vehicles and steel bridge structures to gather crucial data that informs maintenance strategies. Among these, vision-based and weigh-in-motion (WIM) technologies provide real-time insights into structural integrity and load distribution, crucial for identifying potential vulnerabilities (Shokravi et al. 2020). Furthermore, the integration of drive-by damage detection and vehicle bridge interaction (VBI) models enhances the precision of anomaly detection, enabling timely interventions that mitigate deterioration risks. The "drive-by" method involves installing sensors on a passing vehicle to measure its response, which contains information about the bridge's dynamic properties. As research continues to refine these models, particularly by addressing limitations and incorporating autonomous vehicle technologies, vehicle-assisted SHM stands to significantly bolster the effectiveness and reliability of bridge maintenance programs, offering a cost-effective alternative or supplement to fixed sensor networks (Shokravi et al. 2020).

5.5. Integration with Environmental Action Modeling

The structural response of a bridge is profoundly influenced by environmental conditions. Temperature changes can cause expansion and contraction that mask or mimic damage-related changes in vibrational features. Furthermore, environmental factors like corrosion are a primary cause of steel bridge deterioration. Therefore, integrating environmental action modeling into SHM systems is crucial for accurate assessments (Li et al. 2012). By incorporating data on temperature, sustained winds, and typhoon impacts, these models enable a more nuanced understanding of how environmental factors influence bridge performance. This comprehensive approach allows for the identification of global dynamic characteristics and internal forces, which are vital for effective condition monitoring and early warning systems (Li et al. 2012). Consequently, the ability to anticipate and mitigate the adverse effects of environmental stressors ensures enhanced durability and functionality of bridge infrastructure. SHM systems that combine sensors for mechanical response (e.g., strain, acceleration) with environmental sensors (e.g., temperature, humidity) can use statistical or ML models to separate environmental effects from true structural damage, greatly improving the reliability of damage detection algorithms (Comisu et al. 2017).

6. Synthesis, Challenges, and Future Directions

The collective body of literature presents a compelling vision for the future of bridge management, yet it also clearly outlines the significant obstacles that must be overcome to realize the full potential of SHM.

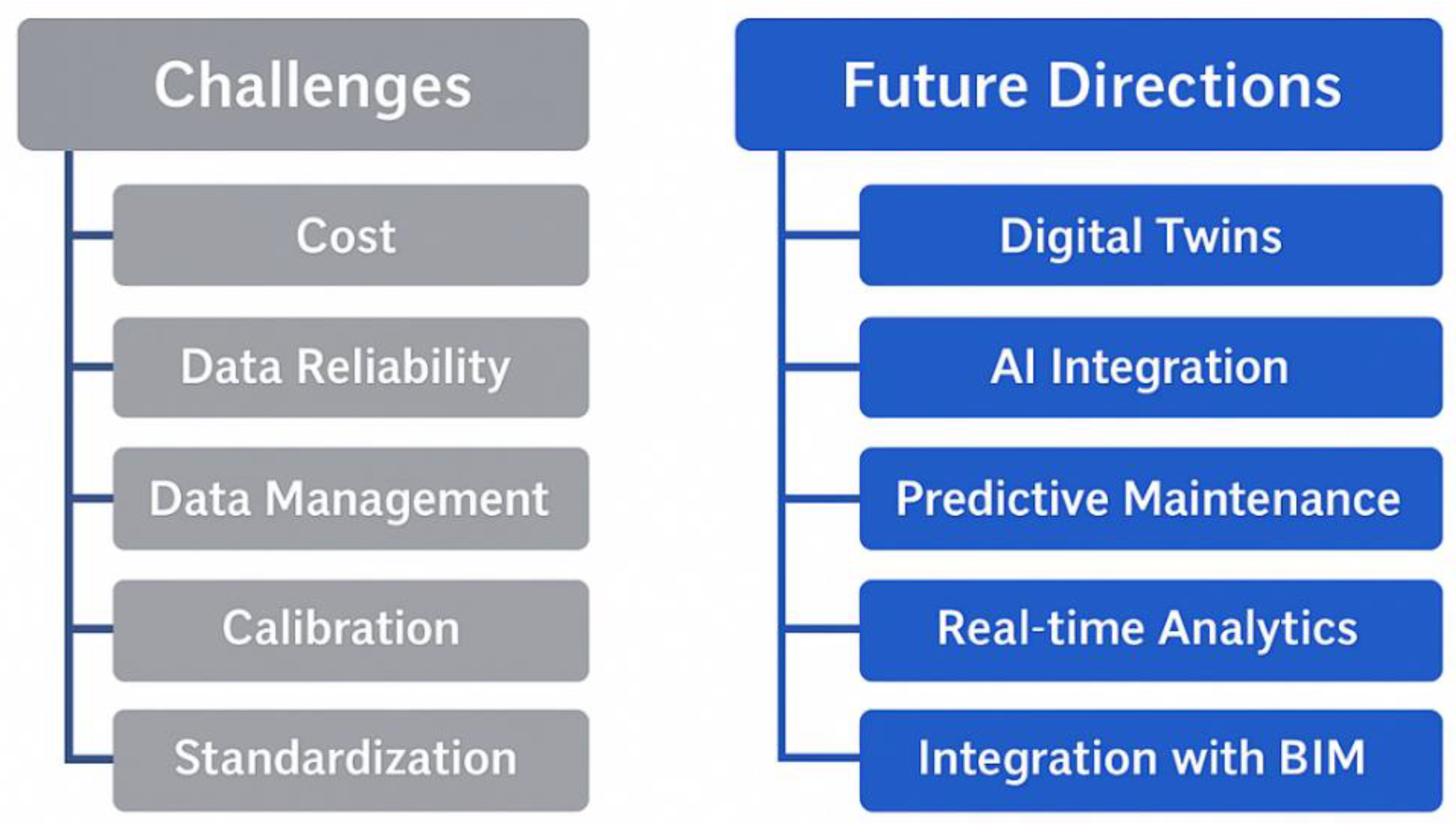

Figure 6 summarizes key obstacles and opportunities for Structural Health Monitoring (SHM). On the left, it highlights practical hurdles—cost, data reliability, data management, calibration, and standardization—that often limit deployment and comparability across projects. On the right, it points to strategic pathways forward: digital twins and AI integration enable predictive maintenance and real-time analytics, while tighter integration with BIM connects SHM insights to design and asset management workflows. Together, the diagram frames SHM’s roadmap: address foundational challenges to unlock data-driven, proactive

6.1. Integration of SHM into Bridge Management Systems

For SHM to deliver on its promise, it must be seamlessly integrated into the broader framework of bridge management systems (BMS). The design of SHM systems for long-span bridges involves a comprehensive approach that integrates multiple modules to ensure effective performance evaluation (Wong 2007). These modules include a sensory system, data acquisition and transmission mechanisms, as well as data processing and control frameworks, which collectively contribute to a robust infrastructure for monitoring critical structural parameters. By adopting such a modular design, SHM can facilitate real-time data collection and analysis, allowing for timely identification of potential structural issues. The linkage between SHM technology and bridge inspection and management offers significant benefits for bridge managers, enabling them to make informed decisions about resource allocation and maintenance strategies (Ko and Ni 2005). This holistic approach not only enhances the reliability of steel bridges but also supports proactive maintenance strategies, ultimately contributing to the long-term sustainability and safety of bridge infrastructure. The fusion of advanced technologies from various disciplines is essential for this integration, providing a more comprehensive understanding of bridge conditions and facilitating timely maintenance and emergency repairs (Ko and Ni 2005).

6.2. Persistent Challenges in SHM Implementation

Despite the technological advancements, several persistent challenges hinder the widespread adoption of SHM.

Cost, Complexity, and Standardization: SHM of steel bridges, despite its potential, remains infrequently utilized in practical applications, primarily due to cost and complexity concerns (Modares and Waksmanski 2013). The initial investment for a sophisticated SHM system can be substantial, and the expertise required for its installation, operation, and data interpretation is specialized. Furthermore, a significant challenge is the lack of standardization in protocols, sensor types, and data formats, which creates a gap between academic research and practical deployment (Sofi et al. 2022). Developing industry-wide standards is crucial for making SHM systems more interoperable, reliable, and accessible to bridge owners and operators.

Data Management and Environmental Variability: The deployment of dense sensor networks and the use of high-frequency data acquisition generate enormous volumes of data, leading to challenges in data storage, transmission, and processing—often referred to as the "big data" challenge (Sun et al. 2020). Moreover, the diverse environmental conditions that steel bridges endure can obscure or mimic signs of structural stress, making it difficult to distinguish between normal environmental effects and actual damage (Entezami et al. 2023). Developing robust algorithms that can reliably perform under these variable conditions remains a key research focus.

Health Monitoring of the SHM System Itself: An often-overlooked aspect is ensuring the health of the monitoring systems themselves, as they are susceptible to deterioration, calibration drift, or damage over time (Giordano et al. 2023). This is particularly relevant for steel bridges, where the reliability of SHM systems directly impacts the accuracy of data gathered for maintenance and safety assessments. If an SHM system provides faulty data, it can lead to misguided and potentially dangerous infrastructure management decisions. By extending the classical Value of Information (VoI) framework, researchers have demonstrated how monitoring the state of SHM systems can offer significant benefits, providing more reliable data for decision-making processes (Giordano et al. 2023).

6.3. Vision for the Future: Intelligent, Proactive, and Resilient Infrastructure

The future of SHM for steel bridges is pointed towards increasingly intelligent, integrated, and proactive systems. The fusion of BD and AI in SHM not only improves the accuracy and reliability of current monitoring systems but also paves the way for future innovations (Sun et al. 2020). The concept of "digital twins", a high-fidelity virtual model of a physical bridge that is continuously updated with SHM data, is gaining traction and has been revolutionized by tools like virtual and augmented reality, enabling engineers to visualize and interact with bridge data more effectively (Catbas and Avci 2022). This allows for scenario planning, predictive maintenance, and optimized management throughout the bridge's entire lifecycle. The cross-application of SHM technologies from other demanding domains, such as aerospace, where diagnosing damage autonomously is critical, could lead to more resilient and sustainable bridge designs, ensuring longevity and reducing maintenance costs over time (Chang et al. 2011). Ultimately, the goal is to evolve from SHM as a diagnostic tool to SHM as a core component of an intelligent transportation system, where data from bridges, traffic, and the environment are integrated to create a truly resilient and adaptive infrastructure network (Zinno et al. 2022).

7. Conclusion

This review has synthesized the significant progress and current state of Structural Health Monitoring for steel bridges. The field has evolved dramatically from its early focus on fundamental vibration-based methods and statistical pattern recognition to a sophisticated, multi-disciplinary engineering discipline. The core technological pillars—advanced sensing (including wireless networks, fiber optics, and non-contact methods), powerful data interrogation techniques (encompassing machine learning, AI, and statistical models), and innovative application methodologies (from fatigue assessment to vehicle-assisted monitoring)—collectively enable a more profound and continuous understanding of structural behavior.

The evidence from literature overwhelmingly indicates that SHM is transitioning bridge management from a reactive, time-based paradigm to a proactive, condition-based, and predictive one. This shift is crucial for addressing the challenges posed by aging infrastructure, increasing traffic demands, and limited maintenance budgets. The ability to detect damage at an early stage, accurately assess the remaining fatigue life, and monitor the health of critical components in real-time directly contributes to enhanced public safety, optimized resource allocation, and extended service life of steel bridges.

However, as the review has highlighted, the full potential of SHM is yet to be realized. Challenges related to cost, system complexity, data management, standardization, and the long-term reliability of monitoring systems themselves must be systematically addressed through continued research, development, and collaboration between academia, industry, and government agencies. The future direction is clear: a deeper integration of sensing, computation, and modeling, culminating in intelligent systems and digital twins that can not only diagnose the present condition but also predict future performance. By continuing to advance and deploy these sophisticated SHM frameworks, stakeholders can ensure that steel bridges remain safe, functional, and resilient cornerstones of our transportation infrastructure for generations to come.

References

- Azad, M. M., S. Kim, Y. Bin Cheon, and H. S. Kim. 2024. “Intelligent structural health monitoring of composite structures using machine learning, deep learning, and transfer learning: a review.” Advanced Composite Materials, 33 (2). [CrossRef]

- Balageas, D., C.-P. Fritzen, and A. Güemes. 2010. Structural Health Monitoring. Google Books.

- Bao, Y., and H. Li. 2021. “Machine learning paradigm for structural health monitoring.” Struct Health Monit, 20 (4). [CrossRef]

- Catbas, N., and O. Avci. 2022. “A review of latest trends in bridge health monitoring.” Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers: Bridge Engineering.

- Chang, F.-K. 1999. Structural health monitoring 2000. Google Books.

- Chang, F.-K., J. F. C. Markmiller, J. Yang, and Y. Kim. 2011. System Health Management: With Aerospace Applications. Wiley Online Library.

- Comisu, C. C., N. Taranu, G. Boaca, and M. C. Scutaru. 2017. “Structural health monitoring system of bridges.” Procedia Eng.

- Deng, Z., M. Huang, N. Wan, and J. Zhang. 2023. “The Current Development of Structural Health Monitoring for Bridges: A Review.” Buildings.

- El-Sisi, A., O. El-Husseiny, E. Matar, H. Sallam, and H. Salim. 2020. “Field-Testing and Numerical Simulation of Vantage Steel Bridge.” J Civ Struct Health Monit, 10 (3): 443–456. [CrossRef]

- Entezami, A., H. Sarmadi, and B. Behkamal. 2023. “Long-term health monitoring of concrete and steel bridges under large and missing data by unsupervised meta learning.” Eng Struct, 279. [CrossRef]

- Farrar, C. R., and K. Worden. 2007. “An introduction to structural health monitoring.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 365 (1851): 303–315.

- Farrar, C. R., and K. Worden. 2012. Structural health monitoring: a machine learning perspective. Wiley Online Library.

- Giordano, P. F., S. Quqa, and M. P. Limongelli. 2023. “The value of monitoring a structural health monitoring system.” Structural Safety, 100. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Cabrera, A., and P. J. Escamilla-Ambrosio. 2022. “Review of Machine-Learning Techniques Applied to Structural Health Monitoring Systems for Building and Bridge Structures.” Applied Sciences (Switzerland).

- Gordan, M., S. R. Sabbagh-Yazdi, Z. Ismail, K. Ghaedi, P. Carroll, D. McCrum, and B. Samali. 2022. “State-of-the-art review on advancements of data mining in structural health monitoring.” Measurement (Lond).

- Huang, N. E., K. Huang, and W.-L. Chiang. 2005. “HHT-BASED BRIDGE STRUCTURAL HEALTH-MONITORING METHOD.” Hilbert-Huang Transform and Its Applications, 263–287.

- Ko, J. M., and Y. Q. Ni. 2005. “Technology developments in structural health monitoring of large-scale bridges.” Eng Struct, 27 (12 SPEC. ISS.). [CrossRef]

- Kot, P., M. Muradov, M. Gkantou, G. S. Kamaris, K. Hashim, and D. Yeboah. 2021. “Recent advancements in non-destructive testing techniques for structural health monitoring.” Applied Sciences (Switzerland).

- Kumar, P., and S. R. Kota. 2024. “Machine learning models in structural engineering research and a secured framework for structural health monitoring.” Multimed Tools Appl, 83 (3). [CrossRef]

- Li, A. Q., Y. L. Ding, H. Wang, and T. Guo. 2012. “Analysis and assessment of bridge health monitoring mass data -progress in research/development of ‘structural Health Monitoring.’” Sci China Technol Sci, 55 (8). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., and S. Nayak. 2012. “Structural health monitoring: State of the art and perspectives.” JOM, 64 (7). [CrossRef]

- Luleci, F., F. N. Catbas, and O. Avci. 2022. “A literature review: Generative adversarial networks for civil structural health monitoring.” Front Built Environ.

- Lynch, J. P. 2007. “An overview of wireless structural health monitoring for civil structures.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 365 (1851): 345–372.

- Marchewka, A., P. Ziółkowski, and V. Aguilar-Vidal. 2020. “Framework for structural health monitoring of steel bridges by computer vision.” Sensors (Switzerland), 20 (3). [CrossRef]

- Modares, M., and N. Waksmanski. 2013. “Overview of Structural Health Monitoring for Steel Bridges.” Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction, 18 (3). [CrossRef]

- Mutnbak, M. 2018. “Investigation of Finger Plate Expansion Devices Behavior.” Thesis. University of Missouri.

- Mutnbak, M., H. Salim, and A. E.-D. El-Sisi. 2021. “Quasi-static strength of bridge fingerplates under various design parameters.” Structures, 32: 2161–2173. [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, T., and B. F. Spencer. 2007. “Structural Health Monitoring Using Smart Sensors.” University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

- Ngeljaratan, L., and M. A. Moustafa. 2020. “Structural health monitoring and seismic response assessment of bridge structures using target-tracking digital image correlation.” Eng Struct, 213. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y. Q., Y. W. Wang, and C. Zhang. 2020. “A Bayesian approach for condition assessment and damage alarm of bridge expansion joints using long-term structural health monitoring data.” Eng Struct, 212. [CrossRef]

- Orton, S. L., D. Barrett, A. E.-D. Elsisi, A. Pelikan, and H. Salim. 2017. “Finger-Plate and Flat-Plate Expansion Device Design Evaluation.” Journal of Bridge Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Orton, S., H. Salim, A. Elsisi, A. Pelikan, D. Barrett, C. Imhoff, G. Kuntz, and M. Wombacher. 2015. Evaluation of Finger Plate and Flat Plate Connection Design.

- Rizzo, P., and A. Enshaeian. 2021. “Challenges in bridge health monitoring: A review.” Sensors.

- Shokravi, H., H. Shokravi, N. Bakhary, M. Heidarrezaei, S. S. R. Koloor, and M. Petrů. 2020. “Vehicle-assisted techniques for health monitoring of bridges.” Sensors (Switzerland).

- Sofi, A., J. Jane Regita, B. Rane, and H. H. Lau. 2022. “Structural health monitoring using wireless smart sensor network – An overview.” Mech Syst Signal Process, 163. [CrossRef]

- Sohn, H., C. R. Farrar, F. M. Hemez, and J. J. Czarnecki. 2003. “A Review of Structural Health Review of Structural Health Monitoring Literature 1996-2001.” United States.

- Sun, L., Z. Shang, Y. Xia, S. Bhowmick, and S. Nagarajaiah. 2020. “Review of Bridge Structural Health Monitoring Aided by Big Data and Artificial Intelligence: From Condition Assessment to Damage Detection.” Journal of Structural Engineering, 146 (5). [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, B. T., G. T. Frøseth, O. Øiseth, and A. Rønnquist. 2022. “A data-based structural health monitoring approach for damage detection in steel bridges using experimental data.” J Civ Struct Health Monit, 12 (1). [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y., C. Chen, K. Sagoe-Crentsil, J. Zhang, and W. Duan. 2022. “Intelligent robotic systems for structural health monitoring: Applications and future trends.” Autom Constr.

- Vagnoli, M., R. Remenyte-Prescott, and J. Andrews. 2018. “Railway bridge structural health monitoring and fault detection: State-of-the-art methods and future challenges.” Struct Health Monit.

- Wan, S., S. Guan, and Y. Tang. 2023. “Advancing Bridge Structural Health Monitoring: Insights into Knowledge-Driven and Data-Driven Approaches.” Journal of Data Science and Intelligent Systems, 2 (3). [CrossRef]

- Wong, K. Y. 2007. “Design of a structural health monitoring system for long-span bridges.” Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 3 (2). [CrossRef]

- Worden, K., and G. Manson. 2007. “The application of machine learning to structural health monitoring.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 365 (1851): 515–537.

- Xu, D., X. Xu, M. C. Forde, and A. Caballero. 2023. “Concrete and steel bridge Structural Health Monitoring—Insight into choices for machine learning applications.” Constr Build Mater.

- Ye, X. W., Y. Q. Ni, K. Y. Wong, and J. M. Ko. 2012. “Statistical analysis of stress spectra for fatigue life assessment of steel bridges with structural health monitoring data.” Eng Struct, 45: 166–176. [CrossRef]

- Zinno, R., S. S. Haghshenas, G. Guido, and A. Vitale. 2022. “Artificial Intelligence and Structural Health Monitoring of Bridges: A Review of the State-of-the-Art.” IEEE Access.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).