1. Introduction

The Finite Ring Continuum (FRC) program [

1,

2] seeks to reconstruct the foundational structures of mathematics and physics within a finite algebraic framework. By replacing the assumption of an actual continuum with relational finitude, it establishes a complete hierarchy of framed number classes —integers, rationals, reals and complex numbers—constructed entirely over finite fields

of prime order

. This framework eliminates ontological infinity while preserving all essential algebraic properties of conventional arithmetic. In this setting, the discrete geometry of each symmetry-complete shell

provides a natural analogue of Euclidean space, whereas its quadratic extension

introduces a Lorentzian split and thereby a notion of causality.

The purpose of the present note is to extend this algebraic foundation from static structure to dynamics. We show that both the Schrödinger and Dirac equations—the central equations of quantum and relativistic wave mechanics—arise naturally within the FRC framework. The Schrödinger equation governs reversible evolution within a single Euclidean shell , while the Dirac equation emerges in the quadratic extension , where the Lorentzian metric and causal structure are algebraically realized. Together they reveal the dual aspects of the FRC universe: the reversible, scale-periodic internal dynamics of a fixed shell, and the irreversible, information-expanding dynamics across shells.

1.1. Conceptual Background

The idea that physical law may have a finite arithmetic basis has been proposed in various forms since the early development of modern mathematical physics. The most direct algebraic precedent is the theory of finite fields and modular arithmetic, whose structure and applications have been comprehensively treated in standard works such as Lidl and Niederreiter [

3] and Lam [

4]. These foundations support the construction of quadratic forms, orthogonal groups, and Clifford algebras over finite fields—tools that are indispensable for defining Lorentz-like symmetry in a discrete setting.

The conceptual motivation for FRC resonates with a broad tradition of finitist and relational thinking. Early intuitions can be traced to Weyl’s constructive critique of the continuum [

5], to Brouwer’s intuitionism [

6], and to the later ultrafinitist program of Yessenin–Volpin [

7], Parikh [

8], and Sazonov [

9], which emphasized feasibility and constructive bounds as foundational constraints. From a physical viewpoint, the FRC approach is closely aligned with the relational perspective of Smolin [

10,

11], who argues that time, space, and law are not absolute but emergent from relations among finite informational systems. Lev’s comprehensive work on finitist foundations of quantum theory [

12] and Zeilberger’s advocacy for discrete analysis [

13] further demonstrate that classical mathematical structures can be regarded as limiting or degenerate cases of finite ones.

Within mathematical physics, several discrete or arithmetic models have attempted to capture relativistic and quantum features without continuum assumptions. D’Ariano and collaborators [

14] derived quantum theory from finite informational postulates; Benci and Di Nasso [

15,

16] developed finitist frameworks based on numerosities; and Lloyd [

17] analyzed physical limits of computation as bounds on the information capacity of the universe. All these lines of research suggest that a coherent finite reconstruction of physics is both conceptually possible and computationally natural.

The FRC formalism builds upon these insights in a mathematically explicit manner. In the foundational paper [

1], finite arithmetic operations are reinterpreted as symmetry transformations: addition as translation, multiplication as scaling, and powering as expansion. The subsequent Lorentzian note [

2] demonstrated that the essential algebraic features of special relativity—the invariant interval and Lorentz symmetry—emerge within finite-field arithmetic only after a quadratic extension

is introduced. The present work completes this triad by constructing dynamical equations consistent with these symmetries.

1.2. Objectives and Outline

The specific objectives of this study are threefold:

To formulate the discrete Schrödinger equation within a symmetry-complete Euclidean shell and demonstrate exact unitary evolution under finite-difference operators;

To derive the finite-field Dirac equation over the quadratic extension and establish its covariance under the finite orthogonal group of split type (Witt index 1);

To interpret the transition as an algebraic consolidation-innovation cycle, linking reversible quantum dynamics with the irreversible emergence of causal structure.

Section 2 reviews the construction of symmetry-complete shells and the Lorentzian extension.

Section 3 defines discrete derivative operators and framed wavefunctions over finite fields.

Section 4 formulates the finite Schrödinger equation and demonstrates its scale-periodicity, while

Section 5 extends the framework to the Dirac equation over

.

Section 6 interprets both equations within the consolidation-innovation cycle, and

Section 7 discusses conceptual implications and future directions.

The overall aim is to demonstrate that finite arithmetic is sufficient to reproduce the full kinematic and dynamical structure of relativistic quantum mechanics, thereby strengthening the case for finite algebra as a universal language of physical law.

2. Background: FRC Shells and Lorentzian Extension

2.1. Symmetry-Complete Shells over

Let

be a prime and let

denote the finite field of cardinality

p. Following [

1], the multiplicative group

is cyclic of order

and hence contains an element

satisfying

. This ensures the existence of the structural class

which provides the minimal two-dimensional algebraic structure supporting rotational symmetry. A field

with this property is called

symmetry-complete of radius

t.

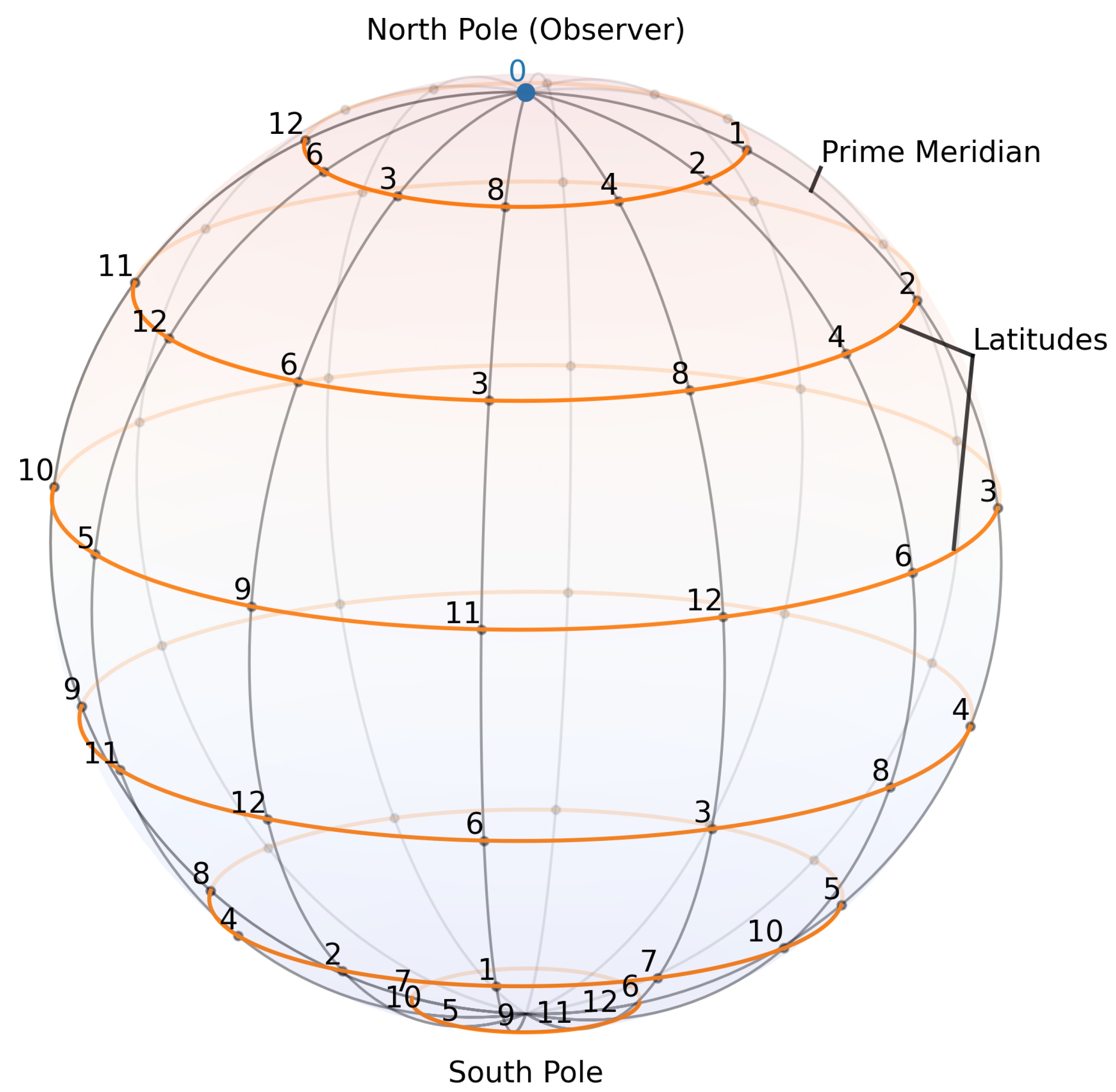

The additive, multiplicative, and powering operations

generate the symmetry group

acting on

. The additive and multiplicative actions define, respectively, the

meridians and

latitudes of a discrete spheroid

embedded in a symbolic

-dimensional symmetry space

Each point

represents a local arithmetic frame characterized by the parameters of translation

a, scaling

m, and powering

. The subspace

of fixed radius

t is referred to as a

space-like shell, or simply an

FRC shell, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Within a single shell all three operations in (

1) are bijective, and the field

exhibits an intrinsic Euclidean symmetry where no causal (time-like) distinction exists.

2.2. Quadratic Extension and Emergence of Causality

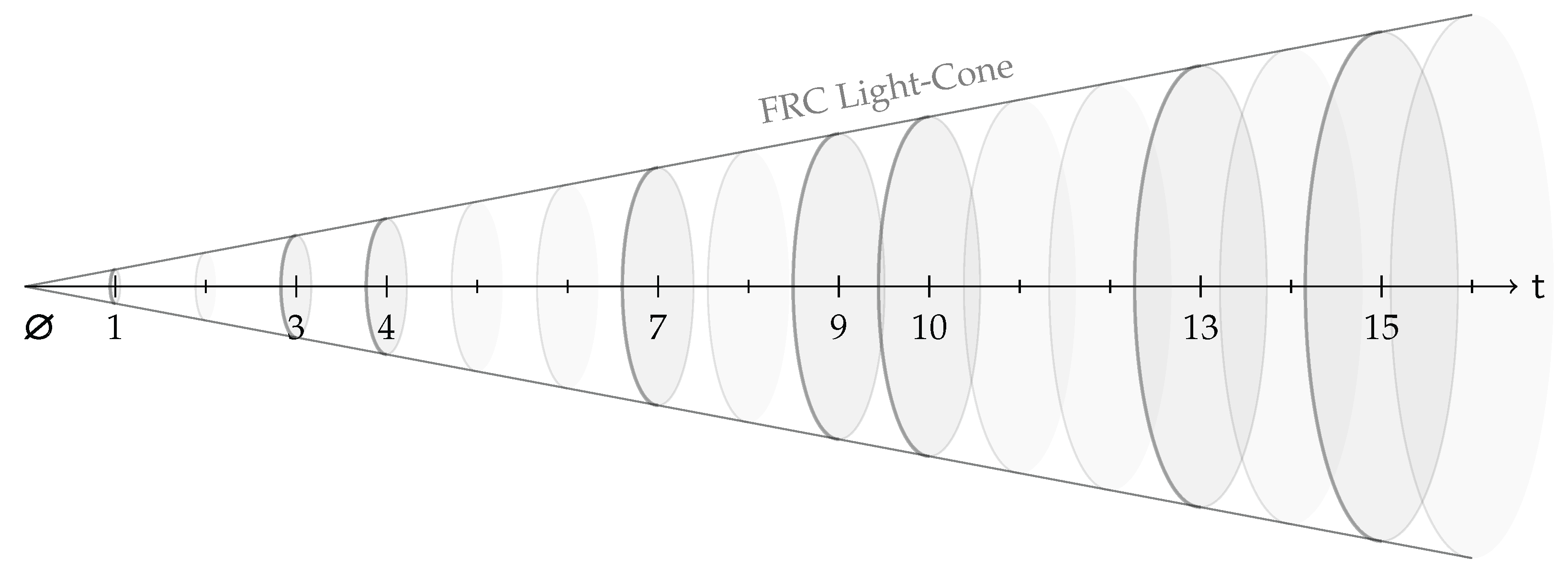

Within the physical interpretation of the FRC framework—which we refer to as Finite Ring Cosmology—the physical universe is modelled as an ensemble of finite arithmetic symmetry shells

formed by a succession of finite algebraic rings

with

and

being a time-like discrete radial chronon parameter, as illustrated in

Figure 2. As has been demonstrated in [

2], a genuine Lorentzian metric cannot be realized within a single space-like shell

. To separate time from space, one requires a coefficient

belonging to the

opposite square class of

. If

is a fixed nonsquare, then no element

satisfies

. The minimal completion that restores algebraic closure is obtained by adjoining such a square root, forming the quadratic extension

The new field therefore acts as the spacetime shell of radius t, while remains its Euclidean subfield.

Within

we can define a Lorentzian quadratic form

whose coefficients now occupy two distinct square classes: the spatial coefficients 1 are quadratic residues, whereas the time coefficient

belongs to the complementary nonsquare class. Equation (

3) thus realises the algebraic analogue of the Minkowski metric with signature

. The corresponding symmetry group

is a finite orthogonal group of split type (Witt index 1), playing the role of the Lorentz group in the finite-field setting.

2.3. Algebraic Interpretation

The passage from

to

constitutes the minimal

expansion step of the Finite Ring Continuum. Inside a single shell, the powering operation

can be many-to-one, compressing information by merging residue classes. The adjoining of

c according to (

2) restores these missing classes and expands the accessible symmetry space. Consequently, the quadratic extension not only enables the Lorentzian split but also represents an informational

innovation—a new layer of algebraic degrees of freedom corresponding to the emergence of causal structure. This step underlies the transition from Euclidean kinematics within

to Lorentzian dynamics within

, which will serve as the foundation for the discrete Dirac and Schrödinger equations developed in the following sections.

3. Discrete Derivatives and Framed Wavefunctions

3.1. Finite-Difference Operators

In FRC framework, all dynamical quantities are defined over discrete algebraic manifolds—the symmetry shells

introduced in [

1]. Let

be a symmetry-complete Euclidean shell and

its Lorentzian extension defined by (

2). Each element

can be regarded as a vertex of the orbital complex

, connected to its neighbours by additive shifts along the meridians and multiplicative shifts along the latitudes of

. This structure enables a purely algebraic definition of discrete derivative operators without invoking any limiting process.

For a scalar field

, we define the

forward finite-difference operator along the

-th coordinate direction as

where

is a fixed generator of translation in the corresponding direction. Higher-order differences are obtained by repeated application of

, and the discrete Laplacian is defined by

where

d is the spatial dimensionality of the shell. All derivatives are computed modulo

p and therefore belong to the same finite algebraic domain as the original field. This construction is frame-covariant: a change of affine reference frame

acts on the arguments by the bijection

, preserving the difference relations

.

3.2. Framed Complex and Real Domains

Wavefunctions in FRC are valued in the

framed complex field

which corresponds to the framed analogue of the ordinary complex plane, as introduced in [

1]. The real subfield

is formed by the closure of the framed rationals under modular convergence, while

denotes the structural imaginary unit associated with the symmetry-complete field (

guarantees

). In the Lorentzian extension

the additional element

c defined by (

2) coexists with

and serves as the algebraic link between the spatial and temporal square classes.

A

framed wavefunction is a map

depending on whether the evolution is considered within a Euclidean or Lorentzian shell. The set of all such functions forms a finite-dimensional vector space over

(or over

in the Lorentzian case), endowed with the standard inner product

where the conjugation

acts as

. Normalization of

is therefore well-defined and purely algebraic:

This allows unitary (norm-preserving) time evolution to be formulated entirely within the finite field, providing a consistent algebraic foundation for quantum dynamics.

3.3. Covariance Across Shells

The derivative operators (

4) and (

5) extend naturally from the Euclidean shell

to the Lorentzian shell

by linearity over the extended scalar field. If

, then

defines a covariant discrete derivative in the presence of the causal coefficient

c. In the limit where the observer’s horizon covers the entire field, the difference operators behave as algebraic analogues of differential operators on a continuous manifold, but without appealing to actual infinity. These discrete derivatives, together with the framed wavefunctions defined above, constitute the kinematic foundation for the Schrödinger and Dirac equations developed in the subsequent sections.

4. Schrödinger Equation in Euclidean Shell

Within a single symmetry-complete Euclidean shell

, the space-time structure remains isotropic and reversible. Causality has not yet emerged, and all arithmetic symmetries

act bijectively. In this regime, the appropriate dynamical law is the discrete analogue of the Schrödinger equation defined over the framed complex field

introduced in

Section 3.

Let

denote a framed wavefunction with spatial coordinate

and discrete time index

. Using the finite-difference operators (

4) and (

5), the Schrödinger equation in a potential

is written as

where

is the structural imaginary unit satisfying

and

is the framed mass parameter.

1 All quantities are evaluated modulo

p, and hence the evolution operator is a finite linear transformation on the vector space of wavefunctions

.

Equation (

7) preserves the inner product (

6) exactly:

so that time evolution is algebraically unitary. This property follows directly from the antisymmetry of the discrete Laplacian and the conjugation rule

in

.

4.1. Scale-Periodicity and Zoom Invariance

As has been established in [

1], the class of framed rationals

possesses an intrinsic scale-periodicity under the

zoom transformation

which rescales the local observation grid by a factor of the primitive root

. After

iterations, the grid repeats exactly:

as a consequence of Fermat’s little theorem

. The same periodicity applies to the discrete Laplacian and therefore to the entire dynamical system (

7). Hence the wavefunction obeys a

finite renormalization cycle

demonstrating that the Schrödinger dynamics in

is scale-periodic and self-similar across zoom levels. From the physical perspective, this periodicity represents the

consolidation phase of the FRC evolution: information is not lost but compressed into repeating symmetry cycles inside a fixed shell.

4.2. Example: Prime

To illustrate the construction, consider the symmetry-complete field

of radius

, whose structural unit satisfies

since

. Let the spatial domain consist of the 13 points

with cyclic boundary conditions. Choose the potential

and the initial state

For

and a discrete time step

, Equation (

7) reduces to

Iterating (

9) over

produces an exactly periodic sequence of states with period

, confirming the scale-periodicity predicted by (

8). The discrete probability distribution

is conserved for all

t, providing a finite-field realization of unitary quantum evolution.

4.3. Interpretation

The discrete Schrödinger equation (

7) encapsulates the Euclidean, reversible dynamics internal to a single FRC shell. All observables evolve unitarily within the bounded informational capacity of

, and the periodic recurrence under zoom operations ensures closed, time-symmetric behaviour. The subsequent transition to the Lorentzian extension

introduces a new coefficient

and thereby enables the emergence of directional causality and the Dirac equation discussed in

Section 5.

5. Dirac Equation in Quadratic Extension

5.1. Lorentzian Setting and Clifford Algebra

The quadratic extension

introduced in (

2) provides the minimal algebraic domain in which a Lorentzian structure can exist. Inside this extension, the time-like coefficient

satisfies

, where

is a fixed nonsquare. The Lorentzian quadratic form

distinguishes the time coordinate from the spatial ones through the square-class separation of their coefficients and defines a finite-field analogue of the Minkowski metric with signature

.

To formulate dynamics that are covariant under the symmetry group

, we introduce the Clifford algebra

generated by elements

satisfying

Since

is algebraically closed under multiplication, a representation of this algebra by

matrices with entries in

always exists. A convenient choice mimics the Weyl representation,

where the

are the standard Pauli matrices with entries in

and

I is the

identity. These matrices satisfy (

11) with all products taken modulo

p.

5.2. Finite-Field Dirac Operator

Let

be a four-component spinor field. The

finite-field Dirac equation is defined as

where

is the structural imaginary unit inherited from the symmetry-complete shell

,

is the framed mass parameter, and the discrete derivative operators

are those defined in (

4), now extended linearly to the field

:

The equation acts on

componentwise and is entirely finite: all quantities belong to the algebraic closure

, and no limiting or differential calculus is required.

Applying the operator

from the left to (

12) yields the finite-field Klein-Gordon relation,

demonstrating that (

12) is a first-order factorization of the Lorentz-invariant wave equation over

.

5.3. Lorentz Covariance

Let

denote the finite-field Lorentz boost parameterized by

, as defined in [

2]. The boost acts on coordinates and spinors according to

where the spinor transformation matrix

satisfies

Substituting these relations into (

12) shows that the Dirac equation is invariant under the finite orthogonal group

, establishing the exact analogue of Lorentz covariance in the FRC framework.

The associated conserved current is

which satisfies the discrete continuity equation

. The algebraic conjugation

acts as complex conjugation in

:

and

.

5.4. Example: Prime and Nonsquare

Consider again the illustrative case

. The nonsquares in

are

; choosing

defines the quadratic extension

The Lorentzian quadratic form

and the corresponding finite Lorentz boost

preserve

exactly:

. Explicit enumeration of the null set

confirms the existence of nontrivial light-like solutions in

, providing a finite analogue of the light cone.

Substituting these data into (

12) allows one to compute discrete spinor solutions

and verify that the bilinear current (

14) remains conserved at each iteration, demonstrating algebraic unitarity and Lorentz covariance at finite

p.

5.5. Interpretation

The Dirac Equation (

12) describes the

innovation phase of FRC evolution. Whereas the Schrödinger dynamics within

compress information into reversible cycles, the extension to

introduces the causal coefficient

c and thereby expands the accessible algebraic degrees of freedom. Particle-antiparticle duality and causal propagation emerge as manifestations of this expanded square-class structure. In this sense, the Dirac formalism represents the first genuinely relativistic dynamics of the finite universe, corresponding to the transition from Euclidean consolidation to Lorentzian innovation in the algebraic exploration of the symmetry space

U.

6. Consolidation-Innovation Cycle in FRC Dynamics

6.1. Compression and Expansion Across Shells

The results established in

Section 4 and

Section 5 reveal two complementary regimes of evolution within the Finite Ring Continuum (FRC). The Schrödinger Equation (

7) operates entirely inside a single Euclidean shell

, where all arithmetic symmetries are bijective and reversible. The corresponding dynamics is time-symmetric, scale-periodic, and informationally closed: each zoom operation returns the system to its initial configuration after a finite number of steps (cf. (

8)).

By contrast, the Dirac Equation (

12) resides in the quadratic extension

, where the coefficient

belonging to a nonsquare class introduces an explicit algebraic asymmetry between time and space. This asymmetry breaks the perfect cyclicity of the Euclidean regime and enables the emergence of causal order. In FRC terminology, the passage

represents the transition from the

consolidation (or compression) phase to the

innovation (or expansion) phase of the finite universe.

6.2. Algebraic Mechanism of the Cycle

Within a symmetry-complete shell

, the powering operation

can become non-bijective whenever

. This many-to-one mapping merges distinct residues into power-residue classes, producing an apparent loss of information. However, from the global viewpoint of the extended field

, these merged classes are fully resolved by the new generator

c that connects the two square classes of

. Thus, the act of powering triggers a compression within a shell, while the subsequent quadratic extension restores and expands the symmetry structure:

Equation (

15) formalizes the

consolidation-innovation cycle: each shell first refines its internal symmetries through local information compression, then innovates by extending its algebraic horizon to include previously inaccessible elements. This mechanism provides an algebraic analogue of the cosmological arrow of time: the universe evolves by iteratively exploring and enlarging its own symmetry space.

6.3. Physical and Informational Interpretation

From the informational perspective, the Euclidean Schrödinger regime encodes reversible micro-dynamics inside a closed information manifold. All processes are unitary and conserve the total informational content of the shell. The transition to the Lorentzian Dirac regime corresponds to the creation of new informational degrees of freedom associated with the extension . To an observer confined within , this extension appears as an irreversible increase of entropy—a forward temporal evolution. Yet from the global, algebraic standpoint of the full FRC structure, the overall information is conserved: compression and expansion are dual phases of a single relational process.

Geometrically, the consolidation phase manifests as periodic motion on the discrete spheroid , while the innovation phase corresponds to the emergence of a new spheroid of higher radius within the same symmetry space U. This expansion of the accessible orbit space represents the growth of the universe in purely algebraic terms.

6.4. Cycle Summary

The complete consolidation-innovation cycle can be summarized as follows:

| Phase |

Algebraic Domain |

Physical Character |

| Refinement (Compression) |

|

Euclidean, reversible, scale-periodic |

| Innovation (Expansion) |

|

Lorentzian, causal, information-expanding |

This alternation of consolidation and innovation provides a natural explanation for the emergence of both quantum coherence and causal structure in the Finite Ring Continuum. The Schrödinger and Dirac equations thus represent not two unrelated formalisms, but successive stages in the universe’s algebraic self-development:

The consolidation-innovation principle therefore unifies the reversible and irreversible aspects of physics within a single, finite, and informationally complete framework.

7. Discussion and Outlook

7.1. Synthesis of Results

The developments presented in this note extend the algebraic framework of the Finite Ring Continuum (FRC) from kinematics to dynamics. Within the Euclidean shell

, the discrete Schrödinger Equation (

7) establishes a reversible, scale-periodic evolution of framed wavefunctions over the finite complex field

. Within the Lorentzian extension

, the Dirac Equation (

12) realizes the first relativistically covariant dynamics, uniting the finite-field Clifford algebra (

11) with the causal structure encoded by the quadratic form (

10). Together these two regimes demonstrate that both quantum and relativistic formalisms can be reconstructed in a purely finite and self-consistent arithmetic setting.

The central conceptual result is the identification of the

consolidation-innovation cycle, summarized in

Section 6. Each Euclidean shell

supports reversible, information-preserving dynamics, while the quadratic extension to

introduces causal asymmetry and informational expansion. This alternation of compression and expansion provides a natural algebraic origin for the coexistence of time-symmetric quantum processes and the directional flow of macroscopic causality.

7.2. Relation to Mass and Complexity

In the broader FRC program, the mass parameter

m appearing in (

7) and (

12) is not a free constant but a frame-invariant scalar associated with the logarithmic measure of algebraic complexity [

1]. From this perspective, the inertial role of

m in the Dirac operator

corresponds to the resistance of the system to informational change: higher algebraic complexity implies greater inertia against reconfiguration under the symmetry group

G. Establishing the quantitative equivalence between this log-complexity mass and conventional inertial or gravitational mass will be the next step in the program. Such a derivation would connect the finite algebraic formulation of quantum dynamics with measurable physical observables and close the conceptual gap between arithmetic information and physical matter.

7.3. Future Directions

Several extensions of the present framework suggest themselves:

Mass, entropy, and energy. The forthcoming extension of the FRC programme will formalize the role of the mass parameter m as a logarithmic measure of algebraic complexity and establish its relation to entropy and energy as quasi-invariant observables of the consolidation-innovation cycle.

Gauge couplings and interactions. Introducing local frame transformations with will allow the definition of finite-field analogues of gauge potentials and covariant derivatives. This could lead to discrete versions of electromagnetic or Yang-Mills interactions within the FRC structure.

Composite shells and hierarchical dynamics. Extending the formalism from prime to composite moduli via the Chinese Remainder Theorem, as outlined in [

1], will enable the study of coupled prime subshells

and the emergence of multi–scale phenomena.

Numerical enumeration and simulation. Finite-field Schrödinger and Dirac dynamics are exactly computable for small primes. Explicit enumeration of wavefunction evolution for can be used to verify conservation laws, Lorentz invariance, and periodicity, providing a constructive test of the formalism.

Continuum correspondence. The asymptotic limit of large

p (always finite) connects the discrete quadratic form

with the continuous Minkowski metric, and the finite-difference Dirac Equation (

12) approaches its standard analytic counterpart. Exploring the rate of this convergence may offer new insight into how continuous physics arises as an effective description of finite algebraic reality.

7.4. Conceptual Outlook

The unification achieved here demonstrates that the essential structures of quantum mechanics and special relativity are not contingent on the continuum hypothesis. Both arise naturally from the arithmetic symmetries of finite fields once framed and extended according to the principles of relational finitude. The Schrödinger and Dirac equations thus represent two complementary faces of a single finite-informational ontology: the former describing reversible evolution within a bounded algebraic frame, and the latter describing its irreversible expansion into a causally ordered domain. From this viewpoint, the evolution of the universe is the process by which algebraic relations progressively unfold their own symmetry space—a self-consistent arithmetic exploration of existence.

References

- Akhtman, Y. Relativistic Algebra over Finite Ring Continuum. Axioms 2025, 14, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtman, Y. Euclidean-Lorentzian Dichotomy and Algebraic Causality in Finite Ring Continuum. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lidl, R.; Niederreiter, H. Finite Fields, 2 ed.; Vol. 20, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.Y. Introduction to Quadratic Forms over Fields; Vol. 67, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Weyl, H. Philosophy of Mathematics and Natural Science; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer, L.E.J. On the Foundations of Mathematics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1927. [Google Scholar]

- Yessenin-Volpin, A.S. The Ultra–Intuitionistic Criticism and the Antitraditional Program for Foundations of Mathematics. In Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics; Elsevier, 1970; Vol. 60, Studies in Logic and the Foundations of Mathematics, pp. 3–45.

- Parikh, R. Existence and Feasibility in Arithmetic. Journal of Symbolic Logic 1971, 36, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazonov, V.Y. On Feasible Numbers. In Logic and Computational Complexity; Springer: Berlin, 1997; pp. 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. The Trouble with Physics; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, L. Time Reborn: From the Crisis in Physics to the Future of the Universe; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

- Lev, F.M. Finite Mathematics as the Foundation of Classical Mathematics and Quantum Theory; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilberger, D. “Real” Analysis is a Degenerate Case of Discrete Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Difference Equations (ICDEA 2001), Augsburg, Germany, 2001; pp. 283–289.

- D’Ariano, G.M. Physics Without Physics: The Power of Information-Theoretical Principles. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2017, 56, 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benci, V.; Nasso, M.D. Numerosities of Labelled Sets: A New Way of Counting. Advances in Mathematics 2003, 173, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benci, V.; Nasso, M.D. A Theory of Ultrafinitism. Notre Dame Journal of Formal Logic 2011, 52, 229–247. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, S. Ultimate Physical Limits to Computation. Nature 2000, 406, 1047–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 |

The connection between the framed mass m and the FRC logarithmic complexity measure will be discussed in Section 7. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).