1. Introduction

In [

1] we proposed the

relativistic algebra over a finite field

equipped with its gauge-covariant symmetry triple—translation, dilation and powering—as an arithmetic object able to represent every affine change-of-coordinates map

(see also [

2,

3]). By arranging these three operators orthogonally to a cardinality axis, we showed that

forms a 2-spheroid (the discrete analog of

)—sitting diagonally in a 4-dimensional coordinate cube of symmetries—that already encodes the combinatorial signature of the topological sphere [

4]. Furthermore, in [

1] we have demonstrated that the resultant mathematical construct is capable of supporting the full extent of arithmetical apparatus provided by the conventional number classes

and

.

The present work advances our program from

purely discrete to

pseudo-smooth geometry. Leveraging a non-principal ultrafilter [

5], we pass from the finite field

to the ultrapower

, a characteristic-

p continuum whose diagonal copy of

forms an infinitesimal lattice, where we let

p to be an odd prime

, and

for its ultrapower. Within

we lift the discrete spheroid to the internal surface

where

is the rational stereographic chart [

6] and

the pseudo-unit interval. Transfer principles [

7] guarantee that

is an internal

two-manifold

1, while its hyperfinite trace reproduces the original

-point lattice exactly. Three consequences follow.

- (i)

Every affine gauge of extends to an internal diffeomorphism of , so the pseudo-smooth surface inherits the full relativistic covariance of the finite algebra.

- (ii)

Loeb-measure shadows [

8] show that the combinatorial curvature of the lattice converges, up to infinitesimals, to the Gauss curvature of

[

9]. This tangible bridge between discrete and smooth geometry in characteristic

p also paves the way for harmonic analysis [

10,

11], heat flow [

12], and gauge theory [

13] on finite relativistic geometries.

- (iii)

The framed field contains three fundamental structural constants——canonically singled out by its cyclic order. These constants serve as finite-field analogs of the classical that underpin calculus on and .

By exhibiting a genuine differential structure generated solely from the finite ring data, we provide concrete evidence that the proposed relativistic algebra can support the full extent of modern geometric ideas. This pseudo-smooth realization is therefore an essential incremental step toward our long-term goal: a unified algebraic foundation capable of expressing and interrelating the languages of mathematics, encompassing both the number theory, and the complete reconstruction of the classical analytic toolkit within a single, finite and gauge-covariant framework.

2. Finite Fields and Arithmetic Symmetries

Let

be a finite ring of integers modulo a natural number

q. The elements of

form a complete and closed set of relational representations of

under modular addition and multiplication. However, the specific numeric labels assigned to these elements—particularly the designation of 0 and 1 as the additive and multiplicative identities—are intrinsically relative and carry no absolute meaning within the ring itself [

1].

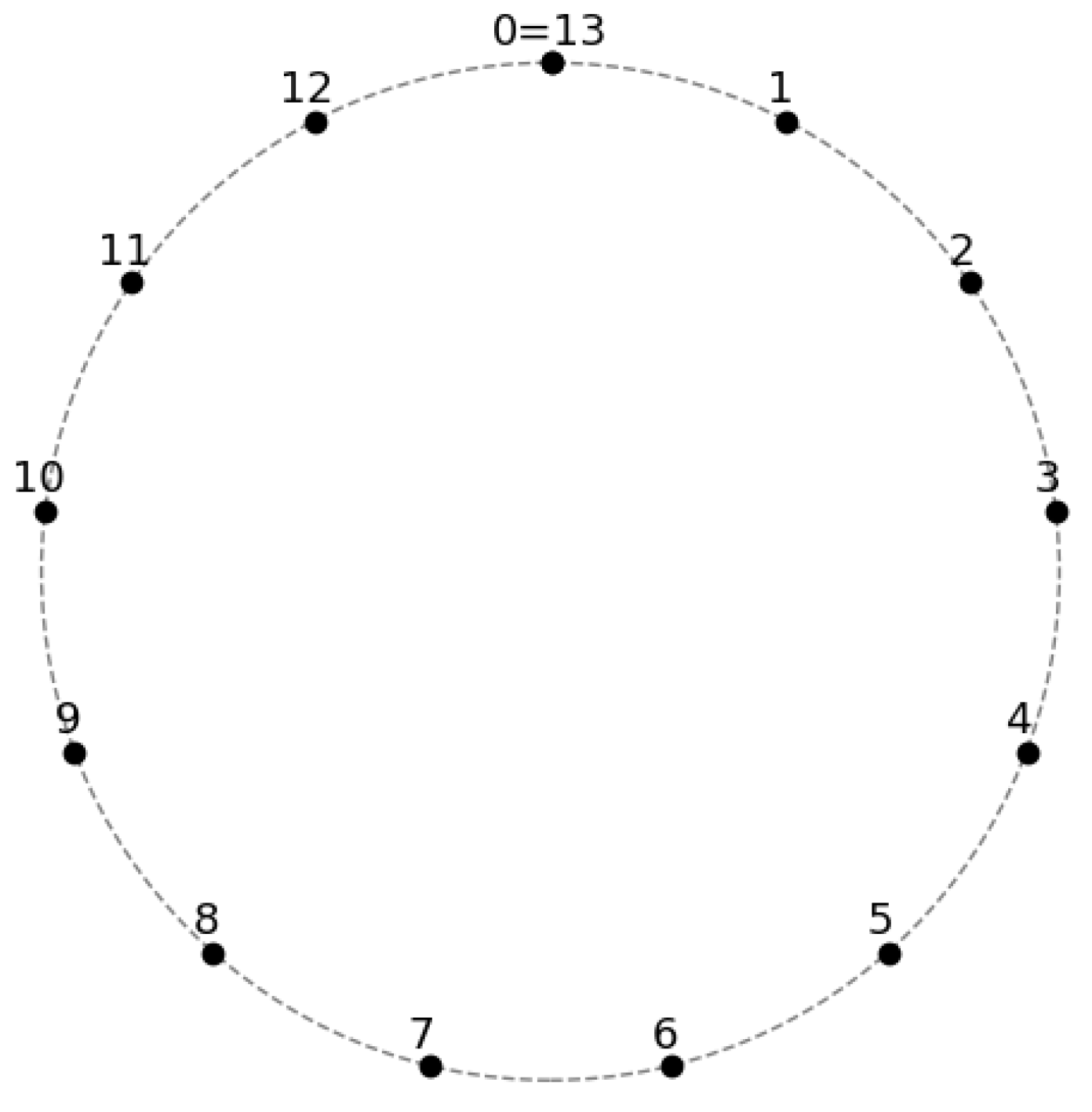

A typical diagram of a finite ring

, where

, is shown in

Figure 1. We would like to specifically note that such a diagram is typically visualized as a circle on a 2D plane that illustrates its periodicity and rotational symmetry under the arithmetic operation of addition, thus assigning an intuitive geometric interpretation to the arithmetic structure of the additive group

. However, the association between arithmetic operations and symbolic geometry can be extended further. In the finite ring

, the basic arithmetic operations of counting, addition, multiplication, and exponentiation can be all understood as manifestations of the underlying symmetries of structural transformations of the field [

14].

Counting corresponds to the selection of the cardinality q of the underlying set. While typically taken for granted, the act of counting is an ontologically and informationally significant degree of freedom that both presupposes the existence of the ring , and determines the entirety of its structural properties. Furthermore, the counting operation establishes a translation symmetry successor map that underpins the operation of addition as its iterative application.

Addition corresponds to the iterative application of counting. The additive group

forms a finite cyclic group of order

q, generated by the element 1. Each addition operation

(mod

q) can be viewed as a rotation by

k steps around a circular configuration of the elements of

. This symmetry reflects the homogeneity and periodicity of the additive structure [

14].

Multiplication corresponds to the iterative application of addition, and furthermore reflects a scaling symmetry within the ring. The operation

(mod

q) corresponds to a dilation or contraction of the additive structure, where the effect of multiplication is constrained by the modulus. The multiplicative structure of

is more subtle: if

q is prime,

forms a finite multiplicative group, and multiplication becomes a permutation of the nonzero elements. If

q is composite, the presence of zero divisors disrupts this structure, but the operation still defines a transformation governed by modular symmetry [

15].

Exponentiation, or the operation

(mod

q), represents iterative applications of multiplication. When restricted to the multiplicative group

, this operation defines power maps and automorphisms that reveal the group-theoretic structure and internal symmetries of the ring. In particular, when

q is prime, exponentiation captures cyclic subgroup structures and encodes deep number-theoretic properties such as primitive roots and residue classes [

16].

Thus, the basic arithmetic operations in are not arbitrary—they are algebraic expressions of the ring’s internal symmetries. They define how elements of the system transform under structured, invertible actions, and they reveal the harmonious regularity inherent in finite arithmetic.

Proposition 1 (3-Manifold Geometry of ). For a fixed value of cardinality q, the finite ring , together with its triplet of arithmetic symmetries, may be interpreted as a discrete symbolic three-dimensional manifold embedded in an abstract four-dimensional symmetry space.

The detailed proof and the precise description of the resultant mathematical structure for non-prime values of q involve additional complexities, such as zero divisors and loss of multiplicative inverses, which are beyond the immediate scope of this publication and will be addressed in detail in our future work. Here, we would like to restrict ourselves to the important case of odd prime q, where the structure simplifies significantly, allowing for a clearer analysis and demonstration of the resultant symbolic geometry.

More specifically, when q is a prime, the ring becomes a field, and the exponentiation symmetry becomes algebraically reducible to multiplication due to the cyclic nature of . As a result, the independent exponential symmetry collapses, and the effective symmetry structure reduces from three to two dimensions. In this sense, the symbolic 3-manifold degenerates to a 2-spheroid within the same 4D space, reflecting a reduction in the degrees of algebraic freedom. In order to emphasize that q is an odd prime, we will henceforth denote it as p and the corresponding finite framed field as .

2.1. The Discrete 2-Spheroid Inside Symmetry Space

Throughout this subsection p denotes an odd prime and its finite field. Write for the multiplicative group, and fix a primitive root .

Definition 1 (Arithmetic symmetries). For

define endomorphisms of

The

translation maps

form the additive group

; the

scaling maps

form

; and

is called

exponentiation.

Lemma 2.1 (Exponentiation collapses to scaling). For every there exists a unique such that on .

Proof. Because is cyclic of order there is m with ; hence for all , and trivially for . □

The symmetry triple therefore contains only two algebraically independent directions, namely translation and scaling.

Definition 2 (Carrier cube and diagonal embedding). Set

the

carrier cube whose coordinates record

Embed the field diagonally by

Definition 3 (Orbit complex). Let

Equip

with the cubical adjacency relation: two vertices are adjacent when they differ in exactly one coordinate by 1 modulo

p. The sub-complex

inherits this incidence structure.

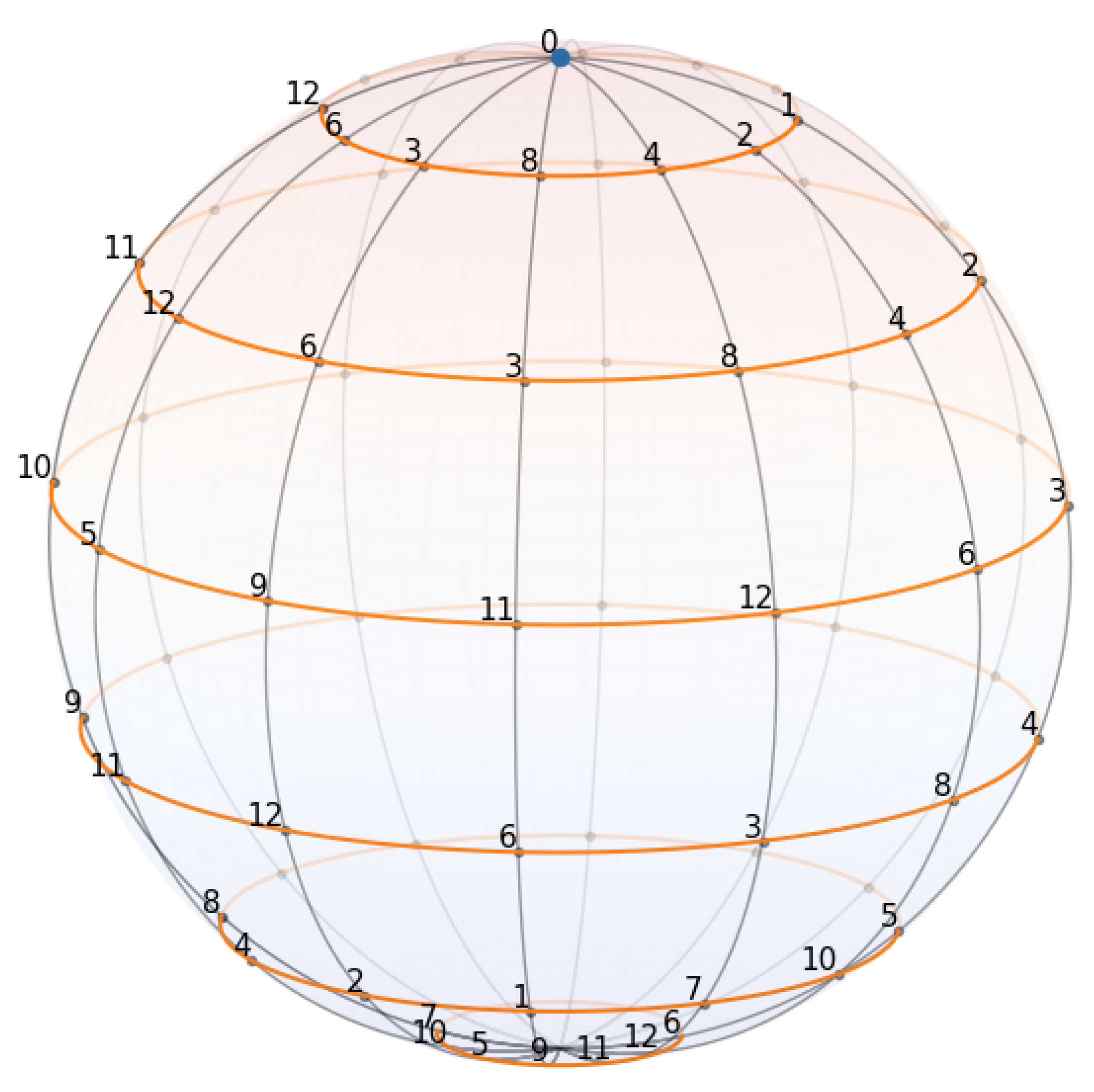

Proposition 2 (Finite 2-spheroid). The orbit complex

is a regular CW-complex [

17] whose links of vertices are combinatorial circles; consequently

is combinatorially isomorphic to the boundary of a 3-simplex, i.e. to the 2-sphere

. Thus,

, together with translation and scaling, realizes a finite

discrete 2-spheroid embedded in the 4-dimensional lattice

as depicted in

Figure 2.

Proof.

Two-parameter generation. By the lemma any composition of reduces to ; hence is exactly the orbit of under the commuting group .

Dimension. Each orbit point is obtained by at most two independent moves (T and S), so every cell in the induced cubical structure has dimension . Non-degeneracy of the actions ensures that two-dimensional faces do appear, making the complex pure of dimension 2.

Local sphericality. At a vertex v adjacent vertices differ from v in exactly one of the two active coordinates. The four resulting neighbours form a 4-cycle, i.e. the link of v is a combinatorial 1-sphere.

Global structure. A finite, pure 2-dimensional CW-complex with cyclic vertex links is necessarily a triangulation of a topological 2-sphere (Alexander duality or direct enumeration). Hence .

□

Remark 2.2. No additional topology is required—the compactness of follows from finiteness. The term “spheroid” refers to the regular 2-sphere CW-structure obtained above, serving as the symbolic analogue of a smooth sphere.

2.2. Pseudo-Smooth Lift to

Let p be a fixed odd prime. All constructions below are carried out inside one and the same finite field .

Definition 4 (Pseudo-reals [

1]). Fix a non-principal ultrafilter

on

and set

is an internal field of characteristic p that is -saturated for every standard . The diagonal copy is a hyperfinite lattice which is -dense in every compact interval of for any infinitesimal .

We write for the pseudo-unit interval, a totally ordered, internally compact subset of .

Definition 5 (Internal stereographic map). Define

Transfer of the classical estimate shows that is internally 1-Lipschitz on .

Definition 6 (Pseudo-smooth surface and lattice). Set

The set is finite with points and inherits from the cubical lattice a regular CW-complex isomorphic to the discrete 2-spheroid of Proposition 2 (each vertex link is a 4-cycle).

Theorem 2 3 (Pseudo-smooth realisation for fixed p). Let p be any odd prime and the pseudo-real field from Definition 4. Then:

is an internal two-dimensional submanifold of .

is a finite 2-sphere CW-complex combinatorially identical to the discrete 2-spheroid of .

For every infinitesimal the lattice is an ε-net in ; equivalently, in the internal topology.

The internal Gaussian curvature of , computed by infinitesimal triangles, is identically 1. (Proof: transfer of the classical formula for σ.)

Proof.(a) Smoothness follows from transfer of the real inverse-function theorem applied to and the coordinate projection . (b)Each vertex of has valency 4; the link is a square; the resulting complex is a flag triangulation of . (c)Given choose with for an arbitrary infinitesimal . Lipschitz continuity of yields a point of within distance . (d)Because is the standard rational stereographic chart, the induced first fundamental form satisfies ; direct transfer of the classical Gauss formula gives . □

The pseudo-smooth 2-spheroid

provides the geometric arena on which finite analogs of differential forms, spinors, and gauge fields can be developed. In forthcoming sections we connect the algebraic observer formalism of the companion paper [

1] with the differential geometry of

, paving the way toward a finite-field approach to relativistic dynamics.

Remark 2.4 (Optional characteristic-zero shadow). If one embeds into a characteristic-0 non-standard field (e.g. via Witt vectors), the standard-part map sends to an honest smooth round 2-sphere in , while collapsing to a -mesh refinement thereof. No such embedding is needed for the internal differential calculus used in this paper, but it can be convenient when comparing with classical geometry.

The theorem shows that every finite framed field already carries within itself—via its pseudo-real completion—a fully fledged smooth-like 2-sphere on which the lattice of field elements forms an arbitrarily fine pixelation.

2.3. Intrinsic Curvature of the Pseudo-Smooth 2-Spheroid

Recall the internal stereographic chart

defined for

. The pseudo-smooth surface of

Section 2.2 is

Set

and abbreviate

for the metric coefficients with respect to the

coming from the standard dot-product on

. A direct internal computation—identical to the real one—gives

Because

we may take the inward unit normal

. Let

denote the second-fundamental-form coefficients. Using

one finds

With

(see, e.g., [

9]) one obtains

In conclusion, every point of the pseudo-smooth surface has constant positive Gaussian curvature and mean curvature . This explicit calculation confirms Theorem 2.3(d).

Remark. Because the fourth “count” coordinate in is flat, all curvature is carried by the three stereographic coordinates. Hence is internally isometric to the unit round sphere in .

3. Canonical Constants in

3.1. Finite-Field Multiplicative Half-Turn Generator

Recall from [

1] that, for every prime

,

is a quadratic residue in

. Define the

imaginary unit

The interval restriction makes the unique square-root in the forward half-cycle of the frame order.

On the additive circle the map corresponds to multiplication by ; it is the quarter-turn rotation, the discrete analog of .

3.2. Natural Exponential Base

In the real calculus the number e is characterized by the minimal-deviation property i.e. the exponential map coincides with the identity to first order at the origin. We translate this idea into the finite setting by choosing, among the primitive roots of , the one that sits closest to 0 in the chosen cyclic order

Cyclic distance. For

define the additive-circle distance to the origin

Forward-time convention. To avoid the duplicity

of primitive roots we restrict attention to the

forward half-circle

Every unordered pair of primitive roots contributes exactly one element to , so the selection below is unambiguous for all odd primesp.

Lemma 3.1 (Uniqueness and minimal increment). is theuniqueprimitive root in the interval , hence the unique primitive root that minimizes both and .

Proof. The interval contains no pair of additive inverses, so is a single element. For any primitive root we have , whence . □

Discrete exponential and logarithm. Using

as base define

Because is minimal among primitive roots, realises the smallest forward difference at the origin, mirroring .

Gauge covariance. Let

be an affine gauge transformation with

. Multiplication by

a is an automorphism of the cyclic group

, so it permutes primitive roots and preserves the order of their residues in

. Translation by

b fixes

. Consequently the image of

under the gauge is the minimiser of (

1) in the new frame; hence

is a

frame-invariant constant of the theory.

Remark 3.2. For primes the forward-time convention coincides with choosing the representative of a pair that is closest to 0; for it simply avoids the fact that itself is a primitive root.

Thus the number inherits inside the defining property of the real constant e: it generates the discrete exponential map that deviates least from the identity at the origin, and its logarithm turns multiplicative structure into additive increments with maximal linear fidelity.

3.3. Finite-Field Additive Half-Turn

The real number is simultaneously a half-period for the rotation group of the unit circle and the factor that converts the sphere’s constant curvature into the length of a half-meridian. Both rôles have exact analogs in every finite field .

Primitive root and half-turn. Fix an odd prime

p and let

be the

least positive primitive root in the framed order

. Euler’s criterion gives the well-known identity

Definition 8 (Half-period integer). Set

is the unique positive integer for which .

Because depends only on p, the quantity is gauge-covariant: any affine relabelling of the frame transports to the new least primitive root but leaves the integer unchanged.

Rotation-group interpretation. Define the additive circle

Multiplication by

acts on

by

and the map

identifies the rotation group of

with the cyclic group of units. Under this identification

is the half-turn (antipodal) map, so

counts

exactly half the lattice points around the discrete circle, mirroring the classical equation

.

Geometric role on the pseudo-smooth spheroid. Embed

diagonally into the pseudo-real line

and let

be the pseudo-smooth 2-spheroid of Theorem 2.3. Its

prime meridian inherits the same rotation group as

. Stepping

times along the lattice

therefore

advances halfway around ;

sends each lattice point to its meridian antipode; and

realizes a geodesic length proportional to .

Since

has constant internal curvature

(

Section 2.3), the Gauss-Bonnet integrand along any meridian satisfies

Thus,

converts the local curvature normalized to 1 into the global half-circumference factor, exactly as real

does on the classical unit sphere.

In summary, the constant plays inside the dual rôle of the real constant : 1. It is the half-period of the discrete rotation group on the framed circle ; and 2. It supplies the universal conversion factor between constant curvature and half-meridian length on the pseudo-smooth spheroid .

Together with the imaginary unit

from

Section 3.1 and

from

Section 3.2, the value

completes the triple of canonical constants

underpinning finite-field calculus over

and

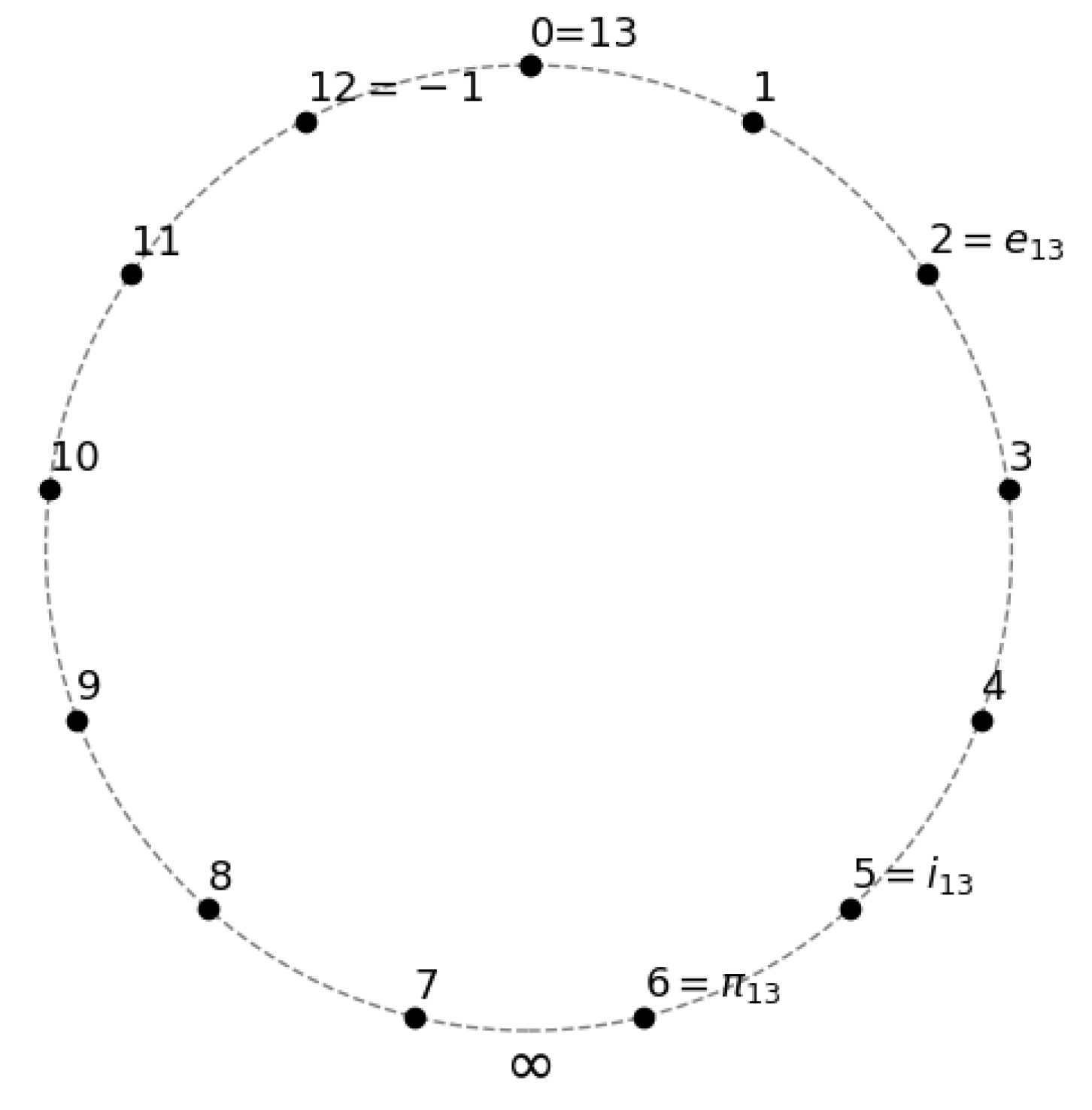

. The triplet of canonical constants for the finite field

is summarized in

Table 1 and further depicted in

Figure 3, where the three constants

are represented as specific elements of the finite field

.

6. Conclusions

We have shown that every odd-prime finite field already contains—in purely arithmetic guise— all the structural ingredients needed for a faithful analog of classical smooth geometry and harmonic analysis.

Discrete-to-smooth passage. Starting from the translation-scaling orbit of we constructed a regular CW complex that is combinatorially . Using the pseudo-real completion we lifted to an internal surface whose hyperfinite trace is -dense for every infinitesimal and whose Gaussian curvature satisfies .

Canonical constants. The cyclic order of picks out three frame-invariant elements— the quarter-turn , the half-period , and the minimal-deviation base . Together they reproduce inside the algebraic rôles played by in and endow with a built-in complex-analytic flavor.

Unified harmonic analysis. Embedding into and identifying with an infinitesimal rotation yields a single kernel that specializes both to the classical Fourier kernel on and to the discrete characters on . Hence Fourier, convolution, Plancherel and Poisson-summation identities coexist in one frame-relative formalism.

Gauge covariance. Every affine relabelling of the framed field extends to a diffeomorphism of and permutes in a way that preserves their defining extremal properties; the geometry is therefore fully compatible with the relativistic-algebra principle introduced in the companion papers.

Lie group. Inside FRC, the rounding-exponential map identifies the framed circle with the cyclic unit group up to an integral kernel, giving an exact finite analogue of the Lie group . Extending component-wise, realises a maximal torus in , so the resultant Lie group is exact and smooth within the finite-ring continuum.

Outlook. The techniques developed here scale naturally to composite moduli

q, where the orbit complex grows from the Hopf-fibered

picture of the prime case [

21] into a full three-manifold. Perelman’s theorem [

22,

23] and discrete Ricci flow [

24,

25] then point to a canonical round metric in which the ordinary fibres remain Hopf circles, but surgery along the zero-divisor cores inserts Seifert multiplicities. In this metric the composite-modulus orbit complex of

becomes a Seifert-fibered 3-orbifold [

26]: its regular fibres link pairwise exactly once, as in the classical Hopf fibration, while each prime factor of

q contributes an exceptional fibre whose DNA-like helix of regular fibres winds around it a number of times equal to the complementary factor; the zero-divisor seams are the axial loops of these helices. Finally, the 2-sphere base of this fibration exhibits the complete set of properties of a Bloch sphere [

27,

28]. These developments are the explicit subject of our companion paper [

29].

By exhibiting a differential, analytic, and symmetry-rich structure generated solely from finite arithmetic data, the present article supports the thesis that finite relativistic algebra and the corresponding finite ring continuum framework can serve as a common foundation for discrete mathematics, classical analysis, and physical modelling within a single, gauge-covariant, finite universe.