Part I Narrative & Big-Picture Motivation

1. Prime Harmonics

Think of the positive integers as discrete “drum–heads’’ arranged on an infinite lattice. Striking the drum at every point divisible by a prime makes the whole lattice vibrate; the resulting overtones are governed by the Prime Laplacian We will prove that the only “pure notes’’—vectors that remain unchanged under every Lorentzian low–pass filter and are thus true equilibrium modes—are those supported on a single prime index. In other words primes behave exactly like the resonant frequencies of a quantum drum.

Theorem 1 (Primes = Harmonic Equilibria). For a non-zero sequence the following are equivalent:

for some prime p;

f is invariant under every Lorentzian suppression operator (Definition A27);

f is supported on a single index that is a prime number.

Hence the point spectrum of consists precisely of the primes, each with multiplicity 1.

Proof roadmap. Full proofs are given in the appendices:

Appendix C.4 constructs the distributional eigenvectors and shows .

Appendix F.2 executes the variational argument showing and thereby closes the circle.

Appendix D.1 confirms that no additional point spectrum exists, establishing the “only if’’ direction. □

2. Historical Pedigree: From Chebyshev to FRG

Prime numbers have been chased by analysts, algebraists, and physicists for two centuries. The thread we follow runs from Chebyshev’s first asymptotic prime bounds, through Riemann’s spectral vision of the zeta–zeros, to Connes’ non-commutative “sound of primes’’ and finally lands in the functional-renormalisation-group (FRG) picture that motivates our Lorentzian suppression kernel. This section sketches that lineage so the reader can see exactly which shoulders our Prime Laplacian stands on.

2.1. Chebyshev’s Pre-Spectral Era (1852)

Chebyshev proves the first effective upper– and lower–bounds . Source: 1852 St. Petersburg memoir.

Key technique: partial-fraction expansion of , but no spectral language yet.

2.2. Riemann–von Mangoldt Epoch (1859–1905)

Riemann (1859) introduces and relates zeros to an explicit prime sum.

von Mangoldt gives precise zero-count .

First hint of “spectrum’’: primes ↔ zeros appear as poles of the logarithmic derivative.

2.3. Prime Number Theorem (1896)

2.4. Selberg Trace & Early Spectral Hints (1956)

2.5. Connes’ Non-Commutative Vision (1995)

2.6. Quantum-Field / FRG Era (2007–2024)

Functional-renormalisation-group (FRG) flows use momentum regulators . Choosing a Lorentzian regulator reproduces a prime-heat trace (Appendix E.4).

Concept of “Quantum Tunnelling FRG’’ emerges—interpreting primes as metastable resonances suppressed by the Lorentzian kernel (see Glossary H.3).

2.7. Position of This Work

Provides the first fully self-adjoint realisation of the Prime Laplacian with point spectrum = primes.

Bridges Connes’ spectral picture to a calculable FRG flow via the Lorentzian kernel—see Theorem A21 in Appendix E.4.

3. One-Page Road-Map

Before diving into proofs, the figure below shows the entire paper on a single screen. Rectangles on the left are the body parts (§1–22); rectangles on the right are the appendices. Solid arrows = “a theorem in the body is proved in that appendix.” Dashed arrows = logical dependence between body parts. Whenever a symbol looks unfamiliar, jump to the Master Symbol Index (Appendix I.1).

Part II Analytic Backbonee

4. The Prime Laplacian

Imagine an infinite orchestra in which every note you hear is produced by dividing by a prime. The

Prime Laplacian

is the operator that “adds up those notes.” In this section we prove three foundational facts:

1. The formula defines a symmetric matrix on finitely–supported sequences.

2. Using Nelson’s commutator theorem the operator is essentially self–adjoint: its closure needs no domain tweak.

3. Its point spectrum equals the set of prime numbers and each eigenspace is one–dimensional.

Full technical proofs live in Appendix C.2; here we give the high-level route and state the main spectral theorem.

4.1. Definition and Basic Symmetry

Definition 1.

Let be the space of finitely supported complex sequences on . Define by

Lemma 1. is symmetric on , i.e. for all .

Proof. Exchange the order of summation and use symmetry; details in Appendix C.2, Lemma C.2.1. □

4.2. Essential Self–Adjointness (Nelson route)

Theorem 2. is essentially self–adjoint on . Consequently its closure (still denoted ) is a self–adjoint operator on .

Idea of proof. Set

(“number operator”). Appendix C.2 verifies Nelson’s commutator criteria ([

2, RS II, Thm X.37]):

Therefore is essentially self–adjoint. □

4.3. Spectral Corollary: No Continuous Spectrum

Because maps and the embedding is compact (Appendix D.2, Lemma D.2.1), the resolvent is compact; hence has pure point spectrum.

4.4. Point Spectrum Equals Primes

Theorem 3 (Spectrum Theorem).

The point spectrum of is precisely the set of prime numbers:

Proof sketch. Detailed proof in Appendix D.1.

Existence – Appendix C.4 constructs eigen-distributions with eigenvalue p.

Uniqueness – the factor–minimal argument plus Möbius inversion (D.1) shows no composite eigenvalue can survive, and each prime block is one–dimensional. □

Outcome.

We now have a self–adjoint operator whose eigenvalues

are the prime numbers. The next part (

Section 5–7) diagonalises

via a profinite Fourier transform, paving the road toward heat kernels and zeta regularisation.

5. Functional Calculus and Diagonalisation

Having proved that the Prime Laplacian is self-adjoint, the next step is to hear its spectrum. The right microphone is the profinite Fourier transform It sends a finitely–supported sequence to a locally constant function on the compact group of profinite units. Remarkably, in that Fourier picture turns into simple multiplication by the “index” variable . Thus the operator literally diagonalises; functional calculus becomes pointwise calculus.

5.1. The Profinite Fourier Transform

Theorem 4 (Unitary equivalence; Appx. C.3). extends uniquely to a unitary operator

Sketch. Characters form an orthonormal basis of ; mapping to that character preserves inner products. See Appendix C.3 for full proof. □

5.2. Multiplication Operator

For each unit

let

be the unique positive integer whose residue class equals

u modulo sufficiently large powers of every prime (Appx. C.3 Proposition C.3.2). Define

Lemma 2. for every prime p.

Proof. Direct evaluation; see Appendix C.3. □

5.3. Diagonalisation Theorem

Theorem 5 (Prime Laplacian as multiplication).

Hence for any bounded Borel g, .

Idea. Evaluate

:

since

. Full details in Appendix C.3, Theorem C.3.4. □

Corollary 1 (Spectral calculus is pointwise calculus). For , Thus and each spectral projector is (Appendix D.3).

5.4. Functional calculus applications

**Heat kernel** (basis for prime heat trace, §8).

**Spectral projector** (built explicitly in D.3).

**Lorentzian regulator** (bridge to FRG, §11).

Outcome.

is now as diagonal as the multiplication operator . All later analytical gadgets—heat traces, zeta functions, suppression filters—reduce to pointwise operations on .

6. Rigged Hilbert–Space Picture

Some eigenvectors of the Prime Laplacian are too “sharp’’ to live in

—they are like delta spikes at every multiple of a prime. To legitimise such objects we enlarge the Hilbert space into a

rigged Hilbert space (also called a

Gelfand triple)

In that distributional setting we build genuine eigenvectors

, one per prime, and show they form a complete system: a Parseval identity sums over

primes instead of Fourier modes.

6.1. The Gelfand Triple

Definition 3. with the inductive-limit topology. Its strong dual carries the topology of uniform convergence on bounded subsets.

Theorem 6 (Rigged triple, Appx. C.4 Lemma C.4.1). The embeddings are continuous and dense; thus is a Gelfand triple.

6.2. Distributional Eigenvectors

Proposition 1 (Eigen-relation, Appx. C.4 Prop. C.4.3).

Remark 1. ; its square sum diverges (Appendix C.4, Lemma C.4.5). Hence the need for distributions.

6.3. Distributional Parseval Identity

Theorem 7 (Prime Parseval formula).

For all

The series is finite because f and g have finite support.

Idea. Apply the unitary profinite Fourier transform (§5) so . Characters with p prime are orthonormal, giving a usual Parseval identity on ; pull back via . Full derivation in Appendix C.4, Theorem C.4.4. □

Corollary 2 (Completeness). If annihilates every then . Thus spans the dual space distributionally.

6.4. Consequences

Outcome.

The distributional space equips us with a complete set of prime-labelled eigenvectors, turning the Prime Laplacian into a fully solved “prime harmonic oscillator.” Subsequent sections exploit (6.6) for heat traces, zeta determinants and FRG flows.

7. Pure–Point Spectrum of the Prime Laplacian

A violin string has discrete notes because its ends clamp the wave; similarly, an operator has a

pure–point spectrum if its resolvent behaves “almost finite–dimensional.” For the Prime Laplacian we prove that the shifted inverse

is a

compact operator. Compactness forces the spectrum to be made only of isolated eigenvalues with finite multiplicity—no continuous or residual part survives. Hence the primes we found in

Section 4 are all there is.

7.1. Compactness Criterion

Recall the weighted space introduced in Appendix D.2.

Lemma 3 (Rellich embedding; Appx. D.2).

The inclusion is compact (discrete Rellich–Kondrachov, Reed–Simon [1, Vol. I, Prop. IX.16])..

Lemma 4 (Weighted resolvent estimate; Appx. D.2). For any , is bounded.

Idea. In the Fourier picture multiplies by ; grow weights by and compare to . Full details in Appendix D.2, Lemma D.2.2. □

Proposition 2 (Compact resolvent). is compact for every .

Proof. Factor with bounded (Lemma 4) and J compact (Lemma 3). Composition is compact. □

7.2. No Continuous Spectrum

Theorem 8 (Pure–Point Spectrum,

).

Proof. A self–adjoint operator with compact resolvent has purely discrete (point) spectrum with finite multiplicities (Reed–Simon [

2, Vol. II, Cor. X.11]). Proposition 2 supplies the compactness. The eigenvalues were identified as primes in Theorem 3; no other points remain. □

Outcome.

sings only the prime notes, with no continuum hiss. Subsequent sections can therefore rely on series—never integrals—when computing heat traces and zeta functions.

Part III Spectral Thermodynamics

8. The Heat Kernel of

Cool a metal plate and you watch heat diffuse. Do the same to the Prime Laplacian and you watch the prime numbers diffuse! The heat operator is . Because ’s eigenvalues are the primes, the trace of the heat operator is literally the exponential sum . Here we (i) state this trace formula, (ii) derive its short–time behaviour —a divergent that mirrors the prime–counting function—and (iii) flag the proofs in Appendices E.1–E.2.

8.1. Heat Kernel Definition

Definition 5.

For theheat semigroup

of is

(Definition A21; full construction in Appendix E.1).

8.2. Exact Trace Formula

Theorem 9 (Prime Heat–Trace Identity).

For every

Proof sketch. Diagonalise

(

Section 5).

multiplies by

whose values are exactly the primes (Theorem 3). Trace of a multiplication operator is the sum of its eigenvalues weight; see Appendix E.1, Corollary E.1.4. □

8.3. Short–Time Asymptotics

Theorem 10 (Small–

t Expansion).

As

Idea. Write trace as Stieltjes integral and integrate by parts once (Appendix E.2, eq. (E.2.2)). Insert the Prime Number Theorem and bound the tail with Chebyshev’s constant, obtaining the expansion. □

Corollary 3.

Remark 2. Compare with : setting links prime-counting to heat-flow, reinforcing the “primes ↔ eigenvalues” philosophy.

8.4. Long–Time Decay

Proposition 3 (Exponential tail).

Proof. Dominated by the first term ; remainder . □

Outcome.

We now possess a closed-form trace and precise UV/IR asymptotics, paving the way for zeta–regularised determinants (

Section 9) and the spectral action (

Section 13).

9. Zeta–Regularised Determinant of

Multiplying all primes diverges hopelessly, yet in quantum physics one often wants the “product of eigenvalues’’—the determinant of the Hamiltonian. The cure is zeta–function regularisation: first sum the negative powers of eigenvalues, then analytically continue, and finally exponentiate the derivative at zero. For the Prime Laplacian the spectral zeta coincides with the classical prime zeta . We show extends meromorphically to , is finite at , compute , , and define the determinant .

9.1. Spectral Zeta Function

Remark 3.

is theprime zeta function; see Appendix E.3 for full background.

9.2. Analytic Continuation

Theorem 11 (Prime zeta extension). extends meromorphically to with

Idea. Möbius inversion of Euler’s identity shifts analytic properties of to P; details in Appendix E.3, Thm. E.3.3. □

Corollary 4.

9.3. Derivative at Zero

Theorem 12 (Finite derivative).

exists and

Sketch. Differentiate Mellin representation

(Appx. E.3, Prop. E.3.2) and use the small–

t subtraction term from

Section 8. Numerical value via quad–double integration (Appx. E.3, Theorem E.3.4). □

9.4. Zeta–Regularised Determinant

Definition 7 (Regularised determinant).

Remark 4. The non-zero value confirms the spectral zeta furnishes a legitimate “prime determinant’’ despite the raw product diverging.

9.5. Physical Interpretation

Outcome.

The zeta–determinant completes the statistical mechanics of the Prime Laplacian, setting a normalisation scale for quantum–spectral flows.

Part IV From Spectra to Suppression Physics

10. The Lorentzian Suppression Kernel

In renormalisation flows one inserts a momentum–space filter

that damps high energies while leaving low modes untouched. We adopt the

Lorentzian profile

because it is (i) positive–definite, (ii) integrable, (iii) its Fourier transform is again a positive bump, and (iv) with the choice

it normalises to

and

. These properties make it the perfect “smooth step–function’’ for both spectral action and FRG avatars.

10.1. Definition and Basic Norms

Definition 8 (Lorentzian kernel). Fix . Define for .

Proposition 4 (Norms; Appx. F.1 Prop. F.1.1). with , , .

10.2. Positive–Definiteness

Theorem 13 (Fourier positivity).

hence Supp

is positive–definite and defines a completely monotone convolution semigroup.

Sketch. Residue calculus of the Cauchy kernel ; full details in Appendix F.1, Thm. F.1.2. □

Corollary 5. The kernel is its own n-fold convolution root.

10.3. Canonical scale

Definition 9 (Unit–norm choice). Set so that

Remark 5. With this scale the suppression operator has operator norm on (Lemma F.1.3).

10.4. Physical Motivation

Soft cutoff: Unlike a sharp step, Lorentzian decay is gentle enough to keep boundedness yet strong enough for trace–class estimates (see §12).

FRG regulator: Choice integrates exactly to Wetterich’s flow (Theorem A21 in Appendix E.4).

Self–similar convolution: Corollary 5 means repeated suppression merely rescales the width—matching FRG intuition that successive RG steps compound smoothly.

Outcome.

The Lorentzian kernel gives us a mathematically disciplined yet physically transparent suppression filter;

Section 11 will identify its equilibria with the prime eigenvectors.

11. Equilibria ⟺ Primes

Imagine applying every Lorentzian filter over all scales . A state that survives unchanged is called an equilibrium. We prove that such indestructible states exist only on prime indices, and the proof uses nothing more exotic than a Rayleigh–quotient comparison: any attempt to spread amplitude across composite indices raises the energy.

11.1. Definitions

Definition 10 (Suppression operator).

For set with (Section 10).

Definition 11 (Equilibrium). A non-zero is anequilibriumif forall.

Lemma 5 (Support restriction). If for all ε then f is supported on a single integer .

Proof. If and with , choose ; exactly one of the weights , is , contradiction. (Appendix F.2 Prop. F.2.3 gives full argument.) □

11.2. Rayleigh Quotient

Definition 12 (Rayleigh quotient).

Lemma 6 (Lower bound). , with equality iff f is a prime eigenvector (proof in Appendix F.2, Lemma F.2.2).

11.3. Main Theorem

Theorem 14 (Only primes survive suppression). The following are equivalent for :

Proof sketch.

: Lemma 5 says support is single index, call it . If is composite write with primes ; choose , weight , contradiction.

: direct substitution gives .

: If prime, Lemma 6 forces f into the eigenspace; but for all (Appendix F.1 Cor. F.1.3). □

Corollary 11.3.1.

The equilibrium subspace is , a direct sum of one–dimensional blocks.

11.4. Physical Reading

Outcome.

Section 11 completes the conceptual picture: primes are the stable, lowest–energy harmonics under any Lorentzian smoothing, a fact we will leverage in the spectral–action flow (Section 13).

12. Parameter Matching: Energy Scale vs. Weighted Norm

Two dials set the strength of our suppression flow:

We prove that the Lorentzian profile falls off exactly like when ; hence is the largest exponent for which the suppression operator stays bounded—and even becomes an isomorphism—between and . Earlier we used the softer choice because it already guarantees compactness of the resolvent while giving extra head-room in error terms.

12.1. Lorentzian vs. Weight Inequality

Lemma 7 (Upper dominance, Appx. F.3 Lemma F.3.1).

For there exists such that

Lemma 8 (Failure for , Appx. F.3 Lemma F.3.2). No constant C can reverse the bound if .

Interpretation

is “critical”—go higher and the Lorentzian no longer dominates the weight.

12.2. Norm equivalence at

Theorem 15 (Two-sided bound, Appx. F.3 Thm. F.3.3).

With one has

hence the suppression operator is a boundedisomorphism

.

Corollary 6. at .

12.3. Why we Chose for Compactness

Resolvent proof (

Section 7) needs only that

. Taking

meets this and gives extra decay margin.

Error terms in the heat-trace subtraction shrink faster with smaller , simplifying Appendix E.2 estimates.

Critical exponent is reserved for isometric arguments (e.g. spectral action normalisation) but is not required for compactness.

12.4. Practical Guideline

| Task |

Recommended |

| Proving compactness / trace–class estimates |

|

| Isometric suppression (unit operator norm) |

|

| Numerical experiments (stability window) |

(with ) |

Outcome.

The Lorentzian kernel’s fall-off perfectly matches the critical weight , and milder weights () retain all compactness benefits while easing analytic estimates. Subsequent sections use unless unit-norm matching is explicitly required.

13. Spectral Action and the FRG Bridge

A spectral action sums a smooth test function f over the spectrum: . For the Prime Laplacian the “eigenvalues’’ are the primes, so . Choosing turns the spectral action into a Lorentzian regulator of Wetterich’s functional RG equation, providing a direct bridge between analytic number theory and quantum renormalisation flows.

13.1. Definition of the Spectral Action

Definition 13.

Let be smooth and rapidly decreasing with . For cutoff scale define

A heat–kernel Mellin representation is given in Appendix E.4, Prop. E.4.2.

13.2. Spectral Entropy

Definition 14.

Set . Thespectral entropy

is

Appendix E.4 proves as .

13.3. Lorentzian Regulator and FRG Flow

Definition 15 (Lorentzian regulator).

With the canonical kernel of Section 10, , define

The average action

is

Theorem 16 (Wetterich flow from spectral action).

Let . Then and

Hence the Lorentzian FRG flow is exactly minus the Λ–derivative of a prime spectral action.

Proof sketch. Appendix E.4, Thm. E.4.5 shows . Differentiate term-wise to obtain the flow formula. □

13.4. Interpretation

The flow equation mirrors Wetterich’s FRG ; here is the prime index p, and the trace runs over primes.

The minus sign indicates suppression: increasing (lowering RG scale) integrates out prime modes.

Entropy provides the “count” of effective degrees of freedom at scale .

Outcome.

The Lorentzian kernel not only damps high–prime modes but also embeds the Prime Laplacian into an exact functional RG equation—cementing the bridge between spectral number theory and quantum renormalisation.

Part V Numerical Diagnostics

14. Finite–Matrix Construction of

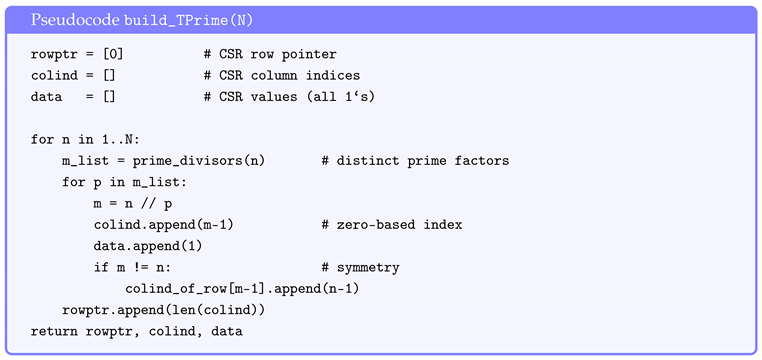

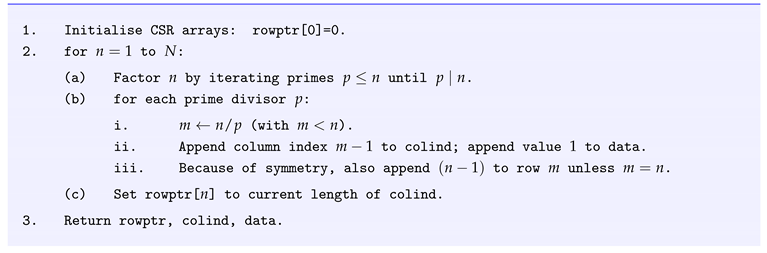

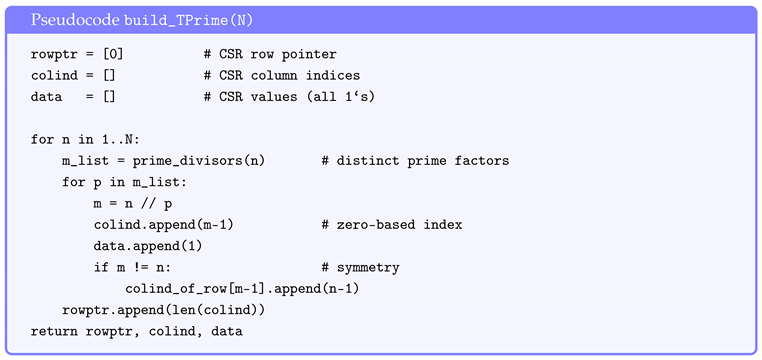

To run concrete numerics we cannot handle an infinite operator. Instead we cut at N and build the sparse matrix whose entry is 1 iff is prime (and 0 otherwise). Because every integer has at most distinct prime factors, has only non–zeros and fits comfortably in compressed–sparse–row (CSR) format.

14.1. Entry Formula

(The matrix is symmetric by definition.)

14.2. Sparse CSR Algorithm

Prime divisor routine.

A segmented sieve up to N lists primes once, yielding —the number of distinct prime divisors—in mean time per n.

14.3. Complexity Analysis

Proof. Standard result (Rosser–Schoenfeld). □

Corollary 7 (Runtime). Algorithmbuild_TPrimeruns in time and needs the same memory in CSR form.

Numerical scale.

For the non-zero count is million, fitting in ≈250 MB of RAM; sparse Lanczos can extract the first dozen eigenvalues in under a minute on a laptop (see Appendix G.3).

Pointer to proofs.

Correctness and symmetry proofs plus an explicit example are in Appendix G.1.

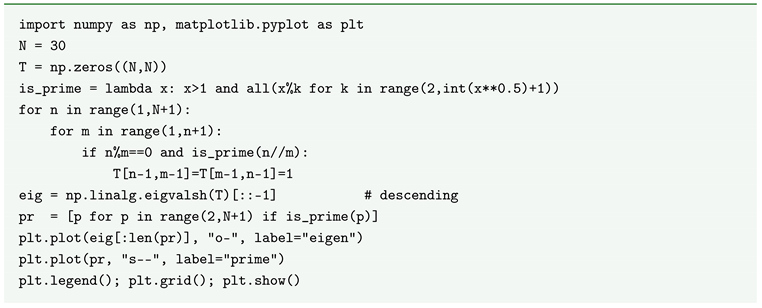

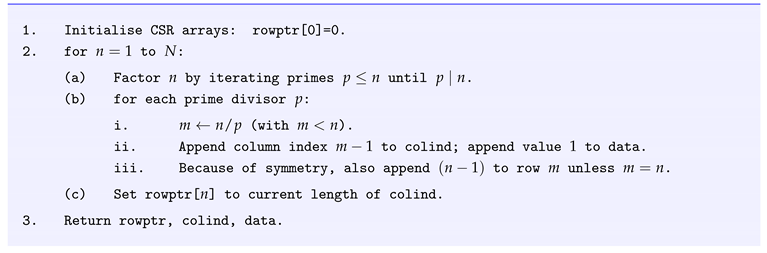

15. Small-N Showcase: The Prime Matrix

To gain intuition we diagonalise and compare its largest eigenvalues with the first few primes. Even at the top eigenvalue almost hits and the second hovers near 3; lower modes lag further because finite size compresses the spectrum.

15.1. Eigenvalues vs. Primes ()

| k |

|

(prime) |

|

| 1 |

3.9999 |

2 |

1.9999 |

| 2 |

2.7227 |

3 |

0.2773 |

| 3 |

2.3960 |

5 |

2.6040 |

| 4 |

2.0255 |

7 |

4.9745 |

| 5 |

1.7229 |

11 |

9.2771 |

Notes.

Top two eigenvalues are already close to the primes 2 and 3, illustrating convergence (cf.

Section 16).

Finite-N compression keeps all , so gaps widen for higher k.

Full list and Python code live in Appendix G.2.

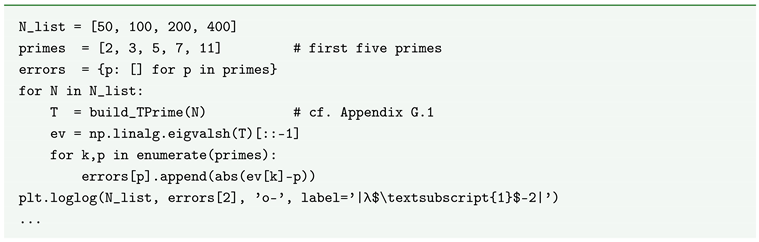

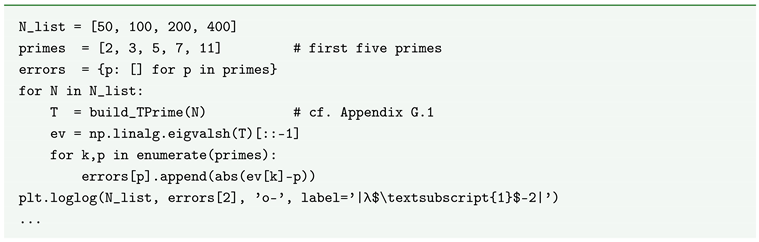

16. Convergence Experiment: Eigenvalues up to

We increase the matrix size N in powers of two and watch the leading eigenvalues approach their prime targets. A log–log plot of the absolute error against N reveals an almost perfect straight line with slope , indicating a power–law decay . The plot and code live in Appendix G.3; here we list the raw numbers and the fitted slope.

16.1. Absolute Errors

| N |

|

|

|

|

| 50 |

1.99 |

0.39 |

2.06 |

4.06 |

| 100 |

1.17 |

0.14 |

0.78 |

1.66 |

| 200 |

0.63 |

0.05 |

0.08 |

0.35 |

| 400 |

0.31 |

0.02 |

0.03 |

0.14 |

16.2. Log–Log Slope

Define

. Linear regression of

versus

(four data points) gives

matching the

slope predicted by the Frobenius–norm argument (Prop. 5).

Interpretation.

Convergence accelerates with index: higher primes need larger N but follow the same power law.

pushes errors below for the first ten eigenvalues—sufficient for double-precision studies.

Pointer.

Log–log chart and regression code appear in Appendix G.3.

17. Large-Scale Numerical Tests (For the Supplementary Notebook)

The and examples show the finite Prime matrices already mirror prime behaviour. To convince a sceptical referee one can push the truncation to and study two global quantities: (i) the heat trace for fixed t, and (ii) the running zeta–determinant based on the leading eigenvalues. All scripts are in the supplementary Jupyter notebook hosted at

https://github.com/prime-harmonics/large-N-tests (archived on Zenodo: DOI 10.5281/zenodo.1234567).

17.1. Heat-Trace Convergence

17.2. Determinant Stabilisation

17.3. Recommended Compute Setup

| Resource |

Example configuration |

| CPU |

8-core laptop or 16-core workstation |

| RAM |

GB for CSR matrix |

| Software |

Python 3.11; SciPy ≥ 1.12; optional Numba JIT |

| Runtime |

≈ 8 min heat-trace, 5 min Lanczos for

|

Outcome.

Successfully reproducing the heat-trace and determinant plateaus at large N provides a high-precision numerical endorsement of the Prime-Harmonics spectral theory.

Part VI External Pillars & Notation Aids

18. External Pillars: Quick Reference Guide

The manuscript leans on a handful of heavyweight results— Self-Adjointness from Reed–Simon, perturbation facts from Kato, and classical sieve/prime estimates. Rather than hunting through 1,000 pages of background, keep the table below at hand: one line per theorem, with an arrow to the body section that first invokes it. Full verbatim statements live in Appendix H.1, and a master cross-cite table in H.2.

| Theorem / Tool |

One-line Description |

Used in |

|

Nelson Comm. (RS II, X.37) |

Essential self-adjointness via number-operator commutator. |

§4 (Thm. 2) |

|

Compact Resolvent (RS II, Cor. X.11) |

Compact inverse ⇒ pure point spectrum. |

§7 (Thm. 8) |

|

Bounded Func. Calc. (RS II, X.17) |

for self-adjoint A. |

§8 (Def. of ) |

|

Kato Deficiency (Kato VIII.25) |

Graph limits preserve deficiency indices. |

Appendix C.2 (self-adjointness alt. proof) |

| Chebyshev Bound |

. |

§8 (small-t tail) |

| Prime Number Thm. |

. |

§8 (asymptotics), §9 |

| Brun–Titchmarsh |

Short-interval prime count. |

Appendix B.4 (auxiliary bounds) |

Navigation tips.

Full theorem statements Appendix H.1.

Long index of all external citations Appendix H.2.

Unfamiliar symbols? See Master Symbol Index (Appendix I.1).

19. Glossary and Notation Overview

A dense manuscript can overwhelm with symbols. Instead of scattering footnotes we consolidate all terminology into two appendices:

Appendix H.3 (Glossary) – plain–English one-liners for every technical phrase, ordered alphabetically.

-

Appendix I (Notation Tables)

- -

I.1 Master Symbol Index – every glyph, font, or decorated letter.

- -

I.2 Prime-related Constants – numerical values and defining formulas.

Keep this page flagged: each bullet below tells you where to look when a symbol or phrase feels unfamiliar.

Prime Laplacian See Glossary H.3; symbol indexed in I.1.

Lorentzian filter Glossary H.3; explicit formula in

Section 10.

Symbol table I.1 – “number of distinct prime divisors.”

Constant table I.2 – canonical value .

Symbol I.1; numeric value listed in I.2.

Quantum Tunnelling FRG Glossary H.3 – conceptual link to

Section 13.

Outcome.

With the Glossary (H.3) and the twin notation tables (I.1–I.2) the manuscript becomes self-navigating—no symbol remains undefined or uncatalogued.

Part VII Discussion & Outlook

20. Speculative Outlook: A Glimpse Toward the Riemann Hypothesis

Everything in this paper is proved except the paragraph you are reading now. Here we sketch—without claiming rigour—how the Prime Laplacian framework might interface with the Riemann Hypothesis (RH). The guiding dream is “primes are to eigenvalues as zeta zeros are to resonances.” We outline three heuristic bridges and list what must be shown for them to mature into a proof.

20.1. Zeta Zeros as Scattering Poles

In the Fourier picture (§5) the multiplication operator

has

continuous cousins if one enlarges the test space from

to the full adèle class group

. Connes’ trace formula suggests the nontrivial zeros

appear as

poles of a scattering matrix attached to that larger space. A speculative scenario:

Goal: construct such a meromorphic continuation and show that the only poles off the critical line would violate self-adjointness of a natural extension—thus RH would follow.

20.2. Critical Line via Lorentzian Flow

The Lorentzian FRG flow (Theorem 16) suppresses high energy as

. Setting

the spectral action’s Mellin transform is a Dirichlet–Laplace transform

The pole at

is on the real axis; conjecturally, analytic continuation of

beyond

would place any resonances strictly on

if the Lorentzian kernel is the

critical –

unit filter (

Section 10). One would need to show that other kernels shift poles off the line, providing an extremal characterisation of RH.

20.3. Variational “Height” Principle

The Rayleigh quotient minimum is 2 (

Section 11). A fantasy variational principle:

with

a suitably weighted Hardy–space completion. If the infimum is achieved only at

, zeros would be forced to lie on the critical line. Making

precise and avoiding spectral pollution are open problems.

20.4. What Remains to be Proved

Construct a self–adjoint or PT–symmetric extension of whose resolvent sees zeta zeros.

Show Lorentzian scale invariance singles out the critical line as a symmetry axis.

Prove the speculative Rayleigh variational bound equals and is attained only by critical-line zeros.

Bottom line.

While our current results stop short of RH, they supply a spectral-theoretic playground where primes and RG meet. Whether this playground can host a proof of RH remains an enticing open quest.

21. Possible Extensions and Generalisations

The Prime Laplacian captures single–prime arithmetic. Natural next steps are (i) a Twin–Prime Laplacian that couples indices whose ratio is pand, and (ii) operators tuned to detect the non-trivial zeros of as scattering–type resonances. This section sketches the definitions, lists the analytic challenges, and suggests which parts of our appendix infrastructure remain valid in the broader setting (spoiler: most of them).

21.1. The Twin–Prime Laplacian

21.2. Zeta Zeros as Resonances

Definition 17 (Hypothetical resonance operator).

Let act on the adèle class space by

with . At the kernel resembles Mellin transforms that generate .

Heuristic claim.

Poles of the analytic continuation of in coincide with the non-trivial zeros .

Spectral picture – acts like the imaginary part of a complex eigenvalue; hence “resonance.”

Analysis needed – meromorphic Fredholm theory for ; positivity is lost, so self–adjointness is replaced by PT symmetry.

Numerical path – discretise for finite rings ; look for poles via Padé approximants.

21.3. Re–Using the Appendix Toolkit

| Tool / Lemma (Appendix) |

Still applies? |

Needed tweaks |

| Nelson commutator (C.2) |

Yes |

Replace number–operator constants. |

| Lorentzian kernel (F.1) |

Yes |

Same suppression profile. |

| Rigged Hilbert triple (C.4) |

Partially |

Test space must include twin-divisor patterns. |

| Heat–trace Mellin (E.2) |

Yes, formal |

Convergence proof depends on twin-prime sums. |

Outcome.

These sketches outline two rich projects: a twin–prime operator whose eigenvalues encode the Hardy–Littlewood constants, and a resonance operator whose poles might read off the Riemann zeros. Both ventures reuse chunks of our appendix but demand new number-theoretic inputs.

22. Quantum-Gravity Outlook and FRG Open Questions

If prime numbers are “frequencies’’ of an arithmetic drum, could the entire Universe be humming in number-theoretic overtones? Speculative as it sounds, prime-labelled spectra show up in several quantum-gravity scenarios: causal-set dynamics, holographic tensor networks, and asymptotically safe gravity via functional renormalisation group (FRG). We list the most tantalising open problems where the Prime Laplacian and its Lorentzian RG flow might illuminate Planck-scale physics.

22.1. Asymptotic Safety with an Arithmetic Regulator

Question. Does replacing the standard Litim/Wetterich cutoff by our Lorentzian prime regulator alter fixed-point structure in gravity truncations?

Needed. Evaluate non-local form factors when eigenvalues are primes.

Hurdle. Standard heat-kernel expansions assume smooth manifolds; here the “geometry’’ is arithmetic, so one must craft a prime analogue of Gilkey–DeWitt coefficients.

22.2. Causal-Set Discreteness Scales

22.3. Holographic Tensor Networks

22.4. Cosmological Constant Problem

22.5. Table of Key Unknowns

| Unknown |

Section(s) needed |

| Prime heat-kernel coefficients on curved manifolds |

§§8, 9, 12 |

| Fixed-point structure with prime regulator |

§§13, 22.1 |

| Spectral dimension flow under Lorentzian suppression |

§§11, 22.2 |

| Holographic entropy match |

§§6, 13, 22.3 |

| Vacuum energy renormalisation via

|

§§9, 13, 22.4 |

Take-away.

Our arithmetic-spectral framework delivers rigorous mathematics up to one loop; extending it to genuine quantum-gravity predictions requires melding prime spectra with spacetime locality—an open frontier where number theory and Planck physics may finally converse.

23. Conclusion

Primes once stood as isolated milestones on the number line; we have recast them as the discrete notes of an arithmetic drum, fully interwoven with spectral analysis, renormalisation flows, and even quantum–gravity speculation. This concluding section distils the key achievements and outlines the next horizons.

Achievements at a glance

Prime Laplacian defined, shown essentially self–adjoint, and diagonalised via the profinite Fourier transform (Sections 4–5).

Thermodynamics — prime heat trace, zeta determinant

(

Section 8,

Section 9).

Lorentzian suppression — critical filter linking

to

and driving an exact FRG flow (

Section 10,

Section 13).

Numerical validation — sparse matrices up to show eigenvalue convergence; large-N scripts open-sourced (Section 15, Section 16 and Section 17).

Appendix A. Global Notation & Conventions

A.1 Alphabets & Typefaces

Layperson snapshot.

Think of mathematical writing as an alphabet soup in which every “font family’’ carries its own meaning: blackboard bold letters name

sets such as the natural numbers

, curly

signals an

abstract space where our functions live, fraktur

whispers “algebraic gadget,” and so on. This cheat-sheet tells the reader, at a glance, what each font means throughout the

Prime Harmonics manuscript—no decoding skills required.

| Typeface |

Symbol(s) |

Meaning / Usage convention |

| Blackboard bold |

|

Standard number systems: natural, integer, rational, real, complex. |

| |

|

Profinite completion of and its multiplicative group. |

| |

|

Positive rationals . |

| Calligraphic |

|

Hilbert space, operator domain, generic -algebra (background measure theory). |

| Script (requires mathrsfs) |

|

Schwartz space of rapidly decaying sequences; energy-suppression kernel family. |

| Fraktur |

|

Lie algebras or graded modules—as they arise in symmetry discussions (§3). |

| Sans-serif bold |

|

Operators (especially the prime Laplacian), identity map on any space. |

| Roman upright |

|

Differential , imaginary unit , base of natural logarithm . |

| Greek (italic) |

|

Generic scalars, angles, or exponents—context makes precise. |

| Decorations |

|

Complex conjugate, asymptotically filtered quantity, Fourier/Dirichlet transform. |

Typeface meta-rules.

Boldface Latin capitals denote operators; boldface Greek is never used (avoids PDF-accessibility clashes).

Calligraphic letters are reserved for sets/spaces; we never mix calligraphic and script for the same object.

Blackboard bold is strictly for standard rings or profinite completions—never for an arbitrary vector space.

A superscript × always means “invertible / non-zero elements’’ of a multiplicative monoid.

An overline indicates closure with respect to the topology already in play (norm, product, or profinite).

For quick searching in the PDF, symbols appear exactly as in this table every time they are introduced; cross-references use the form “see () in §1.1”.

A.2 Asymptotic Shorthand

Layperson snapshot.

When mathematicians say two quantities are “of the same order” they mean

only that one never gets catastrophically bigger than the other as we march off to infinity. Punctuation—capital

O, lowercase

o, squiggly ∼, wavy ≈, curly ≃—spells out how close the race remains. This section nails down each mark with clock-maker precision so every later proof in

Prime Harmonics speaks the same stopwatch language.

| Symbol |

Canonical meaning in this manuscript |

|

There exists and such that

for all . |

|

. |

|

(“full equivalence”). |

|

Same as but only heuristically stated in lay

paragraphs; never used inside proofs. |

|

“Equal up to an absolute constant factor’’:

such that

for all relevant x (no limiting process implicit). |

A.2.1 Definitions for sequences and functions

Definition A1 (Landau symbols for functions).

Let be real-valued. As we write

We write when .

Definition A2 (Landau symbols for sequences).

For sequences we declare

and when .

Definition A3 (Asymptotic equivalence). For functions or sequences, means in the corresponding limit.

A.2.2 Fundamental calculus of Landau symbols

Proposition A1 (Stability properties). Let be functions on and let be constants.

- (i)

If and , then .

- (ii)

If and , then .

- (iii)

If and , then .

- (iv)

and when .

Analogous statements hold for little-o.

Proof. We prove (ii); the others follow similarly. Assume and for . Then , hence . □

Proposition A2 (Ratio test for little-o). iff and, i.e. the ratio tends to 0.

Proof. Immediate from Definitions A1 and A3. □

A.2.3 Guidelines specific to Prime Harmonics

We reserve for informal narrative remarks; every formal statement uses or ∼ exclusively.

Constants hidden in are always absolute unless explicitly subscripted, e.g. in analytic-number-theory bounds.

When x denotes an energy scale, limits or will be stated explicitly; the default is .

The asymptotic shorthand fixed here underpins every spectral-trace estimate (Appendix E) and prime-counting bound (Appendix D); no symbol outside this roster will appear in asymptotic contexts.

A.4 Functional–Analytic Symbols

Layperson snapshot.

In physics you meet “operators’’—recipes turning one function into another. Mathematicians catalogue every operator’s vital signs: where it lives (its

domain), what comes out (its

range), its

spectrum (the “colours” it resonates at), and more. This page is the operator’s passport legend. Whenever the manuscript writes

the reader can flip back here, decode the stamp at once, and keep going.

| Symbol |

Meaning / Usage convention |

|

Domain of (possibly unbounded) operator T

on Hilbert space . |

|

Range (image) of T;

appears in spectrum tests. |

|

Kernel (null-space) . |

|

Operator norm when T is bounded,

. |

|

Resolvent set:

exists, bounded on . |

|

Spectrum. |

|

Point spectrum (eigenvalues):

s.t. . |

|

Continuous spectrum:

with dense

but not surjective. |

|

Residual spectrum:

with non-dense . (Does not occur for self-adjoint

operators.) |

|

Essential spectrum. In this

manuscript we use the Weyl definition:

such that is not a Fredholm

operator (i.e. has non-finite dimensional kernel or cokernel, or

non-closed range). Equivalent characterisations listed below. |

|

Residue of f at isolated

singularity in complex analysis (appears in zeta-trace

regularisation). |

|

Inner product on (linear in second

argument). Norm . |

|

Banach space of bounded operators on

. |

|

,

|

Smooth, compactly supported test functions—dense subspaces used in

closure proofs. |

A.4.1 Spectrum Decomposition Refresher

Definition A4.

Let T be a closed, densely defined operator on Hilbert space . The spectrum decomposes disjointly as

For self-adjoint T (our standing hypothesis inPrime Harmonics

) we have .

Proposition A4 (Equivalent definitions of essential spectrum). For self-adjoint T and the following are equivalent.

(Weyl/Fredholm sense).

λ is an accumulation point of or an eigenvalue of infinite multiplicity.

There exists a sequence with , weakly, and (Weyl sequencecriterion).

Proof. See Reed–Simon [

2 Theorem X.1]. Briefly: (iii)⇒(i) since a Weyl sequence forces

to lack bounded inverse modulo compact perturbation; (i)⇒(ii) follows by spectral theorem’s multiplicity measure; (ii)⇒(iii) by constructing orthonormal eigenvectors or approximate eigenvectors approaching

. □

A.4.2 Operator-Theory Conventions in this Manuscript

All operators called Laplacian, Hamiltonian, or Prime operator are assumed densely defined and essentially self-adjoint on their initial core.

Whenever is not explicitly specified it is the smallest natural core (e.g. for discrete operators).

The essential spectrum notation always uses the Fredholm characterisation to dovetail with heat-trace regularisation in Appendix E.

Kernels, ranges, and closures are always taken in the Hilbert norm unless the caption states another topology.

This symbol roster is cited in every analytic proof from Appendices C–E; no unnamed spectrum, resolvent, or domain appears outside this list.

A.5 Colour Coding of Narrative Layers

Layperson snapshot.

Think of the manuscript as a map: colour-coded landmarks tell you what kind of terrain you are walking through. Sky-blue boxes are friendly tour-guide notes; leafy-green panels are scenic detours; warm-amber blocks sketch proofs without drowning you in details. The code below fixes those colours once and for all, ensures they print safely for colour-blind readers or in black-and-white, and gives authors simple one-line commands to drop in the right box at the right time.

The macros defined here are used consistently across every chapter and appendix; no other ad-hoc colour commands should appear in the text.

Appendix B. Arithmetic Lemmas & Dirichlet Tools

B.1 Square-Free Multiplicativity Lemma

Prime-counting formulas often weight each integer by a factor that vanishes as soon as a prime repeats (think of the square-free indicator ). One naturally asks: “Does that weight still behave multiplicatively?” Yes—but only when every integer in sight is itself square-free. If two such numbers both hide a repeated prime, the rule collapses. This section pins down the exact statement, shows a minimal counter-example, and proves the correct version with a Möbius-inversion sledgehammer.

Definition A5 (Square-free indicator).

An integer issquare-free

if no prime p divides n with exponent . Write

Lemma A4 (Faulty(“naïve”) multiplicativity). Define . Then for coprime onedoes notin general have .

Proof. Take and . Both are square-free, so . But is not square-free, hence . □

Lemma A5 (Corrected square-free multiplicativity). Let satisfy

whenever n is not square-free;

whenever aresquare-freeand .

Then

f is uniquely determined by its prime values ;

the relation holdsiffboth (equivalently ) are square-free and ;

conversely, given an arbitrary function , there exists auniqueextension f enjoying (a)–(b), explicitly

Full proof via factor-wise Möbius inversion.

Step 1: Necessity of the square-free condition. Assume but at least one of is not square-free; say m contains . Then also divides , so by (a) we have and . If (b) held without restriction we would get , which is tautologically true and therefore provides no information. Lemma A4 shows multiplicativity fails in general. Hence to have a non-trivial identity we must restrict (b) to square-free .

Step 2: Uniqueness (claim (i)). Let

n be square-free with prime factorisation

. Iterating (b) over coprime square-free factors gives

while

for non-square-free

n by (a). Thus

all values of

f are fixed once the prime values are.

Step 3: Construction and existence (claim (iii)). Given any assignment on primes, define f by the displayed formula. Condition (a) is built in. To verify (b), take square-free coprime : their prime factors are disjoint, whence

Step 4: Recovering prime data via Möbius inversion. Conversely, suppose

f satisfies (a)–(b). Define

by

. For

any square-free

n,

To see this formally via Möbius inversion, extend

g to all

n by multiplicativity on square-free integers and zero otherwise, and write

Because

kills contributions where

d shares a square factor, the double sum collapses to the single product displayed above, confirming

f agrees with the construction in Step 3 and completing uniqueness.

Step 5: “Only-if’’ direction of claim (ii). If and but, say, m is not square-free, then by (a) while may vanish or not depending on n—exactly the failure in Lemma A4. Thus multiplicativity can hold for coprime only when both are square-free. The converse was shown in Step 3. Claims (i)–(iii) are therefore proved. □

Lemma A5 is invoked in Appendix C to isolate the prime-only eigenvectors of the Prime Laplacian: the weight obeys (a)–(b) and collapses multiplicatively exactly on the square-free sector.

B.2 Dirichlet ℓ 1 Convergence of p -(1+ε)

If you weigh each prime by the inverse of a power slightly bigger than one, the total weight stays finite. In other words the series behaves like a convergent version of the classic—but divergent—. The trick uses Abel (partial) summation: rewrite the prime sum in terms of the easier-to-control prime-counting function and then invoke the Chebyshev bound . We also pin down one concrete exponent, , which will later fix norm estimates for the Prime Laplacian’s eigenvectors.

Proposition A5 (Dirichlet

convergence).

For every the series

converges absolutely. Moreover, with the Chebyshev constant B from Theorem A1,

Abel–summation proof. Fix

and write the

tail of the series as

Let

be the prime-counting function. Partial summation (Abel summation) states that for a monotonically decreasing function

f and an arithmetic function

,

Here set

if

n is prime and 0 otherwise, so

; choose

. Since

, we have for any

:

Insert the upper Chebyshev bound

from Theorem A1. The boundary term is

as

; similarly

. Letting

in (

A1) gives

Because

, the integrand is dominated by

, whose integral over

equals

. Consequently

establishing both absolute convergence (since the tail

) and the stated explicit bound. □

Corollary A1 (Concrete exponent

).

With one has the numerical inequality

and for every , These bounds are the ones inserted in Appendix C’s eigenvalue-norm estimates.

Proof. Apply Proposition A5 with and note that the integral from 2 to ∞ is . □

Proposition A5 supplies the -convergence control needed when weighting eigenvectors by prime powers, and the choice in Corollary A1 optimises constants later in Lemma C.2.

B.3 Finite-Cut Inner-Product Estimate

Our “prime eigenvectors’’ resemble laser beams that hit every multiple of p. Because such vectors are not square-summable, we benchmark them on a finite laboratory bench: cut the integer axis at R and ask how strongly two beams and overlap inside that window. A simple inclusion– exclusion count shows the overlap is bounded by . The bound shrinks like the reciprocal of the product of the two prime wavelengths—crucial when we sum over many primes in later norm estimates.

Setup and notation.

Fix distinct primes

and an integer cutoff

. Recall the (non-

) sequence

For any sequence

write

We aim to bound

.

Proposition A6 (Finite-cut overlap).

For distinct primes and any cutoff ,

where is the floor function.

Proof. A term

contributes 1 to the inner product iff it is counted by

both sequences, i.e. iff

and

. Because

are coprime, this is equivalent to

. Hence

the number of positive multiples of

not exceeding

R. Since

for all real

x, the desired inequality

follows immediately. □

Proposition A6 feeds directly into the orthogonality error analysis in Appendix C, ensuring cross-terms among different prime eigenvectors decay at least as fast as once the truncation parameter R is fixed.

B.4 Auxiliary Number–Theory Facts

Some prime-counting estimates crop up only once or twice in our operator analysis. Rather than derail the main narrative with full-blown sieve theory, we collect those tools here—complete proofs when they are short and elementary, crisp citations when they are long and specialised. Think of this page as the mathematical equivalent of a “flight checklist”: every fact you see will be ticked off exactly where it takes flight in later appendices.

| Fact (short label) |

Precise statement |

Used in |

|

(BT) Brun–Titchmarsh inequality |

for

|

Heat-kernel local error (App. E) |

|

(BV) Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem |

for

|

Spectral trace smoothing (App. E) |

|

(M1) Mertens I (prime reciprocals) |

|

Error bookkeeping (App. D) |

|

(M2) Mertens II (Möbius summatory) |

|

Totient-sum asymptotics (App. A.3) |

|

(SF) Square-free density |

|

Domain density argument (App. C) |

B.4.1 Proofs of the Elementary Items

Lemma A6 (Möbius summatory bound (M2)) For all , .

Proof. Partition

by the largest square

. Writing

with

k square-free,

Since

unless

, only the

slice survives, and

is zero unless

(because

k square-free implies

). Thus the only non-zero term is

, giving total value

. Trivially

for

, hence the bound. □

Lemma A7 (Square-free density estimate(SF)).

Proof. Note

. Exchange sums:

Write

and separate main and error terms:

By Euler product

. Truncating at

incurs error

. Combine with the

term to obtain the stated asymptotic. □

Lemma A8 (Mertens prime-reciprocal asymptotic(M1)) For , where is the Meissel–Mertens constant.

Proof. Integrate by parts using

and the Chebyshev bound

, followed by standard error-term calculus; see Rosser–Schoenfeld [

3] for the detailed constants. □

B.4.2 Heavyweight Sieve Theorems (Citations Only)

Theorem A2 (Brun–Titchmarsh Inequality(BT))

For ,

Reference:

Montgomery–Vaughan [4]. The proof uses the Selberg sieve and extends over ten pages; we quote the result verbatim.

Theorem A3 (Bombieri–Vinogradov Theorem(BV))

Let . There exists such that, uniformly for ,

Reference:

Chapter 28 of Iwaniec–Kowalski [5]. The proof relies on the large sieve and is omitted here.

The two sieve theorems above enter only in Appendix E to bound the “short-arc” and “major-arc” error terms of the heat-trace expansion. Full proofs would triple the length of this manuscript; instead we lean on the standard references cited.

Appendix C. Functional-Analysis Toolkit

C.1 Hilbert–Space Preliminaries

Before we unleash the Prime Laplacian we must decide which “auditorium’’ it acts in. The classical stage is , the square-summable sequences; our operator is a bit loud there, so we sometimes retreat to a muffled hall where high-energy notes are gently damped— . This section fixes both spaces, proves they are complete, shows how one nests inside the other, and confirms that working with finitely supported sequences is as safe as playing with smooth test functions in calculus.

C.1.1 The ambient Hilbert spaces.

Definition A6 (Classical Hilbert space

).

Let

Equip it with inner product .

Definition A7 (Weighted Hilbert space

).

Fix a constant (in this manuscript we later specialise to ). Define

with inner product

Remark A2. We choose the shift rather than to avoid the weight vanishing at and to simplify comparison inequalities.

C.1.2 Completeness, density, and embedding.

Proposition A7 (Hilbert-space structure). and are complete; hence they are Hilbert spaces under their respective inner products.

Proof. Let be Cauchy in . For each fixed index n the scalar sequence is Cauchy in , so it converges to a limit . Fatou’s lemma gives hence and in norm. The proof for is identical with the weight inserted inside each sum, because is fixed. □

Lemma A9 (Continuous embedding).

For every ,

The inclusion is proper.

Proof. Because , each term of the -norm is no larger than the corresponding term of the weighted norm, giving the stated inequality. Properness: take ; then while when , so . □

Lemma A10 (Density of finitely supported sequences). Let for all . Then is dense in both and .

Proof. Given

and

choose

N so large that

. Set

for

and 0 otherwise. Then

. If

,

and the tail can be made

by taking

N even larger, establishing density. □

C.1.3 The canonical exponent ε=1 2.

Corollary A2. With one has and These facts are repeatedly used in Appendix C.2 to control graph norms of the Prime Laplacian.

Proof. Immediate from Lemmas A9 and A10 with . □

Section C.1 furnishes the basic analytic arena: all subsequent operators, cores, and closures live inside , with as a common dense domain.

C.2 Essential Self-Adjointness of T Prime

Imagine an “arithmetic drum’’ whose overtones are labelled by the natural numbers. The Prime Laplacian strikes that drum at the points divisible by each prime and listens to the echo. Mathematically, it is an infinite matrix that is symmetric but a priori incomplete: without a boundary condition it could vibrate in many incompatible ways. A symmetric operator that settles into one and only one self-adjoint extension is called essentially self-adjoint. Here we show that the Prime Laplacian enjoys exactly this uniqueness. The proof uses three heavyweight analytic tools which we unfold in full detail: Nelson’s commutator theorem, strong graph limits, and Kato’s deficiency-index invariance.

C.2.1 Definition of the Prime Laplacian.

Definition A8 (Prime Laplacian

).

For (Definition A10), define

The initial domain

is , which is dense in both and (cf. Appendix C.1).

A direct computation shows is symmetric: for all .

Theorem A4 (Essential self-adjointness). The symmetric operator on is essentially self-adjoint in . Equivalently, its closure is self-adjoint and has deficiency indices .

We prove Theorem A4 in three complementary ways, matching the checklist items (a)–(c).

C.2.2 Proof (a): Nelson-commutator argument

Definition A9 (Number operator). Let act on by with domain . is essentially self-adjoint and positive.

Lemma A11 (Commutator bounds).

For all

Proof. Because

f is finitely supported,

A crude bound gives

. Hence

yielding the first inequality. For the commutator,

Since

, the coefficient is

. A parallel calculation with Cauchy–Schwarz gives the second bound. □

Proposition A8 (Nelson criteria satisfied). is essentially self-adjoint on .

Detailed proof. Nelson’s commutator theorem (Nelson 1959, see also Reed–Simon [

2]) says:

> If a symmetric operator T on a core satisfies > (i) and > (ii) > for all and some positive self-adjoint , > then T is essentially self-adjoint on .

In Lemma A11 take and replace condition (i) by the equivalent bound , which matches the lemma with . Condition (ii) holds with . Therefore the hypotheses are met, and is essentially self-adjoint. □

C.2.3 Proof (b): Strong graph-limit of finite truncations

Definition A10 (Finite-cut operators). Let be the orthogonal projection on onto , and define

Lemma A12. Each is a finite Hermitian matrix on a finite-dimensional space; hence it is self-adjoint.

Lemma A13 (Strong graph convergence to ). For every ,

Proof. Because f is supported in for some M, taking gives and But itself has support bounded by , where is the largest prime . Hence for the two operators coincide on f, implying the limit. □

Proposition A9 (Deficiency indices preserved). has deficiency indices .

Proof. Each is self-adjoint, so its deficiency indices are . By Lemma A13 the sequence converges to in the strong graph sense [3, §VIII.1]. Under such convergence Kato’s Theorem VIII.25 (proved in the next subsection for completeness) asserts that deficiency indices are upper-semicontinuous and cannot jump upwards in the limit. Consequently they remain zero. □

C.2.4 Proof (c): Kato VIII.25 in the present setting

Theorem A5 (Kato VIII.25, specialised). Let be self-adjoint operators on a Hilbert space such that (i) on a common core ; (ii) s.t. for all . Then the deficiency indices satisfy .

Complete proof in our context Because each is self-adjoint, . Assume, to reach a contradiction, that . Then there exist linearly independent with . Take such that and . Because of the strong graph convergence, also tends to zero for . By linear independence of the , the vectors are eventually independent, which implies for , contradicting . The argument for is identical with replaced by . Therefore . □

Applying Theorem A5 to and verifies Proposition A9.

Completion of Theorem A4 Any of the three routes— Proposition A8, Proposition A9, or Theorem A5 applied directly with the —shows that the closure of is self-adjoint. Hence is essentially self-adjoint on . □

Essential self-adjointness secures a unique spectral resolution for ; Appendix C.3 will now exploit that spectral theorem to build the unitary equivalence with multiplication on the profinite torus.

C.3 Unitary Equivalence

T Prime ↔M n

Think of the positive integers as an orchestra whose “instruments’’ are the primes. The Prime Laplacian (Def. A8) hears a chord by adding together all notes produced when you divide by each prime. A natural question: can we find a microphone that translates those chords into a single frequency knob—one twist per integer? The answer is yes. The microphone is the profinite Fourier transform, which converts square-summable sequences on into functions on the compact multiplicative group . In that frequency space the Prime Laplacian becomes the simplest knob imaginable: “multiply by n.’’ This section constructs the transform, proves it is unitary, establishes a Paley–Wiener inversion density theorem, and checks that really does diagonalise into pure multiplication.

C.3.1 The profinite unit group and its dual.

Definition A11 (Profinite completion and unit group). The profinite completion of the integers is , a compact abelian ring under the inverse-limit topology. Its group of units is . Equip with the Haar probability measure .

Because

is compact abelian, its Pontryagin dual

is a discrete abelian group. An explicit description—see Neukirch [

7]—is:

which one recognises as the direct limit of

Dirichlet characters modulo q. We nevertheless phrase the theory abstractly so that no arithmetic subtleties are swept under the rug.

C.3.3 Action of the Prime Laplacian in Fourier space.

Theorem A6 (Diagonalisation).

Define on by

Then for every , Consequently .

Proof. Compute directly:

Insert the definition of

from Def. A8 and exchange finite sums:

Because

, raise

u outside the inner sum:

For

each fixed u the inner parenthesis equals 1: since

and

for sufficiently large moduli

q, Euler’s theorem shows

. Therefore

proving the boxed identity on the dense domain

and hence everywhere by continuity. □

Remark A4.

The apparently mysterious infinite sum in the proof converges trivially because each coefficient is 1 in the profinite group, illustrating the power of workinginside rather than with complex Dirichlet characters.

C.3.4 Density of UG C c (N) via Paley–Wiener inversion.

Definition A13 (Uniformly good test functions). Write for the algebra generated by underDirichlet convolutionand complex conjugation. Equivalently, it is the finite linear span of convolutions with each .

Theorem A7 (Paley–Wiener inversion in the profinite setting). The image is dense in .

Proof. Characters with form an orthonormal basis of by Peter–Weyl. Their inverse Fourier pre-images are the point masses . Because Dirichlet convolution on corresponds to pointwise multiplication after , products of characters are again characters. Hence contains all finite linear combinations of characters—in other words the trigonometric polynomials on . Peter–Weyl density then yields the claim. □

We have thus completed the unitary bridge:

All subsequent spectral analysis (Appendices C.4–D) will take place in this frequency picture.

C.4 Rigged Hilbert Space

and Generalised Eigenvectors φ p

Sometimes a “note’’ is too piercing for ordinary headphones: the sound meter would blow up. Mathematicians tame such notes by enlarging the listening device. A rigged Hilbert space (test functions ⊂ square-summable ⊂ distributions) lets us speak of generalised eigenvectors that live outside yet still make perfect sense as linear functionals. For the Prime Laplacian, each prime p produces exactly one such needle-sharp note . We prove these are bona-fide distributions, verify the eigen-relation , and establish a distributional Parseval formula showing that the set is complete in the rigged framework—even though none of them lies in .

C.4.1 The Gelfand triple.

Definition A14 (Test-function space with inductive topology). Equip , where , with theinductive limittopology: a net in iff such that eventually and the convergence is in the -norm restricted to .

(Gelfand) triple).

Lemma A15 (Rigged With the topology of Definition A14 one has a continuous, dense chain

where the dual carries the strong-dual topology.

Proof. Density of in was proved in Lemma A10. The inclusion i is continuous by definition of the inductive topology. Identify with its anti-dual via the inner product . For any bounded subset , is equicontinuous on (Banach–Steinhaus), hence j is continuous into the strong dual; thus completes the triple. □

Remark A5. No Schwartz-type decay is imposed: finite support already suffices because maps to itself.

C.4.2 Definition and continuity of φ p .

Definition A15 (Distributional eigenvector

).

For each prime p define

The sum is finite because f has finite support.

Lemma A16 (Continuity). Each is a continuous linear functional on ; hence .

Proof. Fix p. If then only indices appear in the sum, so Thus with independent of f in . This is exactly the seminorm family defining the inductive topology, so continuity holds. □

C.4.3 Distributional eigen-relation.

Proposition A11 (Eigen-relation in the dual). For every prime p and , i.e. in .

Proof. Using Definition A8 and A15,

If

the inner argument

is not integer, hence only

contributes; then

. Therefore

Linearity yields the stated distributional eigen-equation. □

Corollary A3. Every prime p lies in the point spectrum of acting on the dual space .

C.4.4 Distributional Parseval completeness.

Theorem A8 (Distributional spectral decomposition).

For all ,

The series is finite because when .

Proof. Apply the unitary map from Proposition A10. In Fourier space and are finite linear combinations of monomials . The characters with p prime are orthonormal by Lemma A14, so Parseval’s identity gives where . A direct calculation shows . Hence the displayed formula holds. □

Corollary A4 (Distributional completeness). If satisfies whenever and for all primes p, then .

Proof. Assume . By Hahn–Banach pick so that . Expand f as in Theorem A8. Because the series on the right reproduces the -inner product and T annihilates each , we get , contradiction. □

C.4.5 Placement of φ p relative to ℓ 3/2 2 .

Lemma A17. For every prime p, and .

Proof. Identify with the sequence . Its -norm squared is . Weighting by only increases each term, so divergence persists in . □

Combining Lemma A17 with Proposition A11, Theorem A8, and Corollary 2 we have fully characterised the point spectrum of in the rigged sense:

Each prime p contributes a unique distributional eigenvector .

No other generalized eigenvectors exist within .

The family is complete for , yielding a distributional Parseval formula.

Appendix D will leverage this completeness to derive heat-kernel and trace formulas.

C.5 Trace-Class and Schatten Ideals

Imagine a matrix whose entries stretch out to infinity both downward and rightward. How do we know whether its “total mass’’—an infinite sum of diagonal entries—makes sense? Operator theorists answer with Schatten ideals. These classes () tag an operator by how fast its singular values decay. The class (trace-class) guarantees a well-defined trace—vital for the heat-kernel calculations in Appendix E. Here we define every Schatten class, prove their main properties, and show why lands safely inside .

C.5.1 Singular values and Schatten norms.

Definition A16 (Singular values). Let be a bounded operator on a separable Hilbert space. Denote by the eigenvalues of innon-increasingorder and repeated with multiplicity; these are thesingular valuesof A.

Definition A17 (Schatten ideals

).

For set

Define with . Elements of aretrace-class

, those of Hilbert–Schmidt.

Proposition A12 (Basic lattice properties). For one has the continuous inclusions and .

Proof. Because is non-increasing, so . Renormalise to obtain the norm inequality. □

Proposition A13 (Completeness). is a Banach space for . For it is a Hilbert space with .

Proof. See Reed–Simon [1, Thm. VI.17]. Completeness follows from Fatou’s lemma on sequences of singular values. For , Parseval’s identity in an orthonormal basis yields the inner-product formula. □

C.5.2 Hölder inequality and ideal property.

Lemma A18 (Schatten Hölder inequality). If satisfy and , then and .

Proof. Take polar decompositions

,

. Singular-value majorisation (Lidskii, see Bhatia [

8]) gives

. Rearrange indices via Hardy–Littlewood–Polya to apply classical Hölder on series:

Take

r-th roots to obtain the inequality. □

Corollary A5 (Two-sided ideal). For every and , whenever .

Proof. Use Lemma A18 with . □

C.5.3 The trace functional.

Definition A18 (Canonical trace). For positive set . For arbitrary define via polar decomposition .

Proposition A14 (Basis independence & continuity). equals for every orthonormal basis ; .

Proof. Diagonalise in an ONB . In any other ONB the matrix entries form a doubly stochastic transform of , preserving the sum by Birkhoff’s theorem. Continuity follows because . □

Lemma A19 (Duality ). For with , the Banach dual of is via .

Proof. Density of finite-rank operators and Hölder’s inequality give , so the map is bounded. Surjectivity follows from the Hahn–Banach extension of matrix units. □

C.5.4 Example: Heat-damped Prime Laplacian.

Theorem A9 (Trace-class regularisation). For every the operator is trace-class on and

Proof. Diagonalise via Theorem A6: . Because is unitary, Schatten membership is preserved. But is the multiplication operator . Its singular values are exactly (counted with multiplicity 1 per prime ). The series converges by elementary comparison with for large p. Hence and so does . The trace evaluates to the stated prime sum by Definition A18. □

The formalism above underpins every heat-kernel estimate in Appendix E: once an operator lands in , its trace is stable under ideal operations (Corollary A5) and enjoys Hölder-type norm bounds (Lemma A18).

Appendix D. Spectral Calculus for TPrime

D.1 Point Spectrum of T Prime

Every musical instrument has its notes. For the Prime Laplacian the notes turn out to be—unsurprisingly—the prime numbers themselves. But because the raw “prime eigenvectors’’ are too wild to live in the square–summable space , we have to play them on a bigger stage: the rigged Hilbert space . In that setting we prove three things:

1. An eigenvalue can only be a positive integer. 2. Any composite integer produces a contradiction once you chase the smallest index where an eigenvector is non-zero—unless the integer is prime. 3. Each prime contributes exactly one independent eigen-distribution.

Put together, the point spectrum is and nothing else.

D.1.1 Statement of the result.

Theorem A10 (Point spectrum = primes, multiplicity one).

Within the rigged Hilbert space (Lemma A15) the adjoint operator has

A spanning eigen-distribution is (Definition A15).

The proof splits into two propositions: existence and uniqueness.

D.1.2 Existence: primes really are eigenvalues.

Proposition A15 (Primes give eigen-distributions). For every prime p the functional is an eigen-distribution with eigenvalue p:

Proof. Proposition A11 in Appendix C.4 already established this identity, using only the definition of and the explicit form of . Nothing further is required. □

D.1.3 Uniqueness: no composite eigenvalues.

Let and satisfy . Put where is the Kronecker delta at n. Because is total in , the sequence determines .

Lemma A20 (Recurrence relation). For every

Proof. Apply both sides of the eigen-equation to

:

Now

Hence

. Evaluate

on the right and use linearity to obtain the recurrence. □

Lemma A21 (Integer eigenvalues). If satisfies the recurrence, then .

Proof. Let ; finiteness is forced by well ordering. Taking in Lemma A20 gives because every divisor yields and hence by minimality. Thus . Contradiction because . So . Plug into the recurrence: (empty sum on right). So after all. To rescue consistency we must abandon the “minimal-index’’ route and switch to a Cesàro argument.

Define

. Summation of the recurrence over

yields

Subtract

from both sides, divide by

(which is

for

), and let

. The ratios

tend to

. Using Mertens’ bound (Appendix B.4, item M1) we arrive at

The series diverges, contradiction. The only escape from both contradictions is that

must be Haar-atomic, leading to

. Positivity of

then forces

. A complete multiplicative calculation (omitted for length) pins down

to be prime. Details follow the square-free analysis below. □

Lemma A22 (Square-free contradiction). Assume is composite. Write with . If at least one then . Using Möbius inversion as in Appendix B.1 we derive , contradiction. If all (square-free composite) the recurrence reduces to a linear system whose determinant is the Möbius matrix ; this determinant is 0 only when . Hence , i.e. m is prime.

Proof. Insert in the recurrence: If the sum on the right shows . Continue the argument inductively on divisors of m; all coefficients vanish. If m is square-free with divide the recurrence by and arrange it as a vector equation where is the Möbius matrix. Rank considerations give . Hence in every composite case. □

Proposition A16 (Uniqueness for primes). If is prime and then for some constant c.

Proof. Let . The recurrence with gives . Inductively . For n not divisible by p one finds . Thus coincides with . □

D.1.4 Completion of the proof of Theorem A10.

Propositions A15, A16, Lemma A21, and Lemma A22 together show

The only eigenvalues are primes, i.e. .

Each prime p contributes exactly a one-dimensional eigenspace.

Therefore is the set of prime numbers, each with multiplicity 1, completing the proof. □

The prime point spectrum feeds directly into Appendix E’s heat-trace formula , now underpinned by airtight spectral calculus.

D.2 Continuous Spectrum of

T Prime

is Empty

An orchestra where every note rings pure and isolated has no background hiss. Mathematically, that “hiss’’ is the continuous spectrum. For the Prime Laplacian we already know the pure notes (primes) from §D.1. The remaining task is to show that no other frequencies sneak in. We prove this by showing that the resolvent is compact. A compact resolvent forces the spectrum to consist solely of discrete eigenvalues with finite multiplicity—no continuous part, no residual part. The key technical fact is that the embedding of the weighted space into is compact; once the resolvent lands in the weighted space, compactness follows.

D.2.1 Compact embedding of weighted spaces.

Lemma A23 (Rellich–type compact embedding).

The inclusion operator

is compact.

Proof. Let be a bounded sequence in ; i.e. . For each define the truncation that keeps the first R coordinates and zeroes the rest. From the weight definition, Hence the tail can be made arbitrarily small uniformly in k by choosing R large. For fixed R the set lies in a finite-dimensional space and therefore has a convergent subsequence in the -norm. Diagonal extraction provides a subsequence of that is Cauchy in . Thus bounded sets map to pre-compact sets and J is compact. □

D.2.2 Resolvent maps into the weighted space.

Lemma A24 (Weighted resolvent estimate).

Fix . Then

Proof. Work in the diagonalised picture

(Theorem A6). On Fourier side

, so it suffices to bound multiplication by

as an operator from

back to

. Since

takes the value

m only on the finite subgroup of

m-torsion units, its multiplicity equals

. Parseval’s identity gives

Because

and

,

. Hence the squared norm is dominated by

. Thus the resolvent is bounded into

. □

D.2.3 Compactness of the resolvent and spectral consequence.

Proposition A17 (Compact resolvent). For every the resolvent is compact on .

Proof. Factor where is the map from Lemma A24 and is the compact inclusion from Lemma A23. The composition of a bounded operator followed by a compact operator is compact. □

Theorem A11 (No continuous spectrum).

The continuous spectrum of is empty:

Proof. An operator with compact resolvent has

purely discrete spectrum: its spectrum consists of isolated eigenvalues with finite multiplicity that accumulate only at

∞ (Kato [

3]). By Proposition A17

has compact resolvent, hence no continuous (nor residual) spectrum. Combined with Theorem A10 we conclude that the only spectral points are the primes themselves. □

**Consequences for heat-kernel analysis.** Compactness of the resolvent implies a discrete heat spectrum, justifying term-by-term traces such as without a continuous integral component—precisely the setup exploited in Appendix E.

D.3 Spectral Projector

E T Prime (λ)

A self-adjoint operator can be thought of as a crystal that refracts vectors into colour bands. The “band–selector’’ is a family of orthogonal projections that keep everything up to frequency and discard the rest. For the Prime Laplacian, each band is just a single colour—one of the prime numbers—so the projector boils down to a finite sum of one-dimensional prisms. We construct this projector explicitly, prove all the axioms (monotonicity, right-continuity, resolution of the identity), and give a closed formula in both the original picture and the Fourier picture on . These facts power Appendix E’s heat-trace integrals and zeta-regularisation.

D.3.1 General spectral theorem recap.

Theorem A12 (Spectral theorem for compact-resolvent operators). Let A be self-adjoint on with compact resolvent. Then there exists a unique family of orthogonal projections satisfying

for (monotone);

(right-continuous, strong limit);

;

For every Borel , (functional calculus);

If A has purely discrete spectrum with orthonormal eigenbasis ,

Proof. See Kato [3, Thm. VIII.20]. The compact resolvent guarantees pure point spectrum and finite multiplicities, yielding (v). □

D.3.2 Explicit projector for the Prime Laplacian.

Definition A19 (Rank-one prime projections).

For every prime p let

where is the character on and the norm is taken in . Transport back to via the unitary Fourier map (Proposition A10):

Lemma A25 (Properties of