Submitted:

16 October 2025

Posted:

20 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

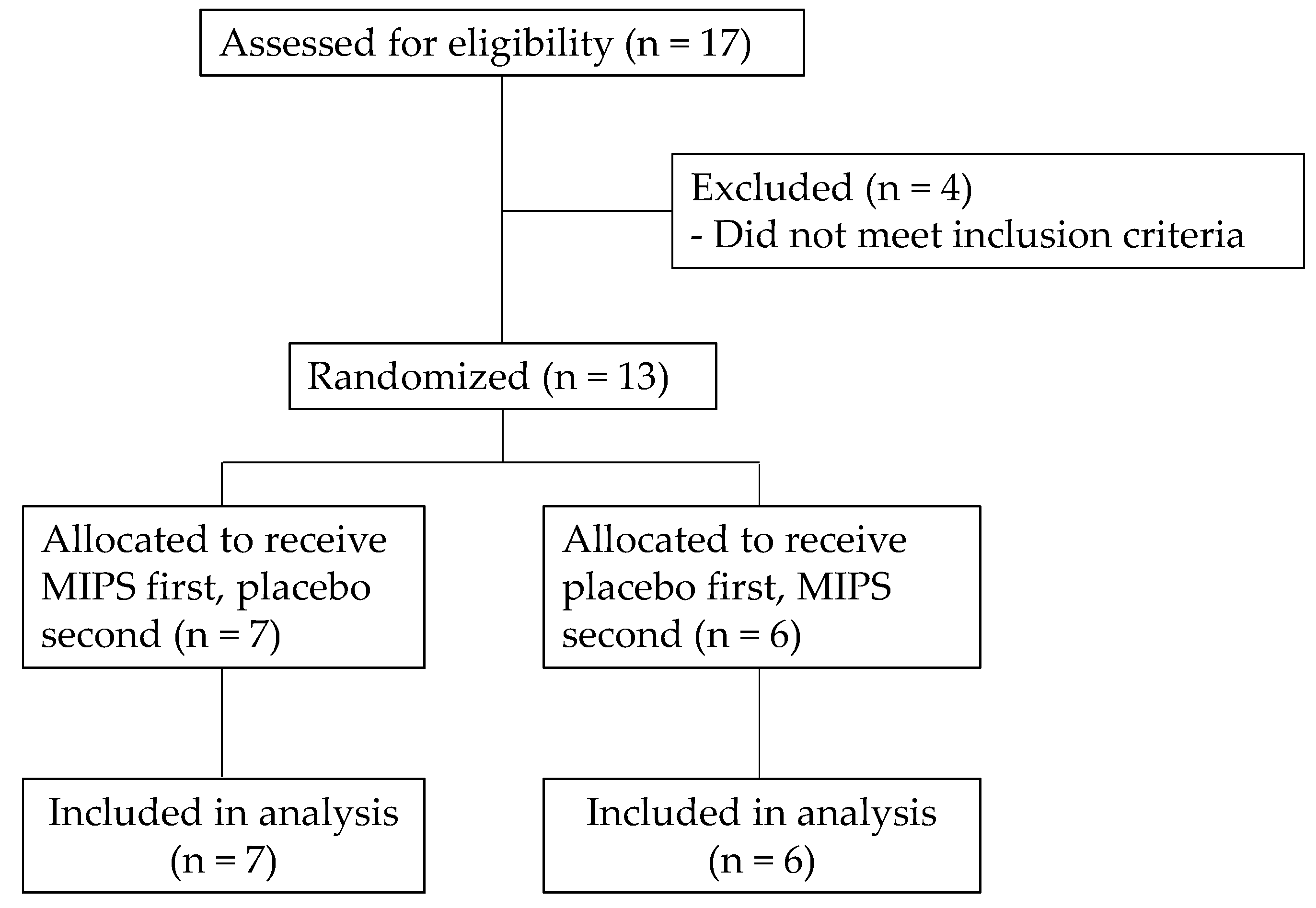

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Subjects

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Visit 1: Familiarization

2.3.2. Visits 2 and 3: Fatigue Protocol Tests with Supplementation

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

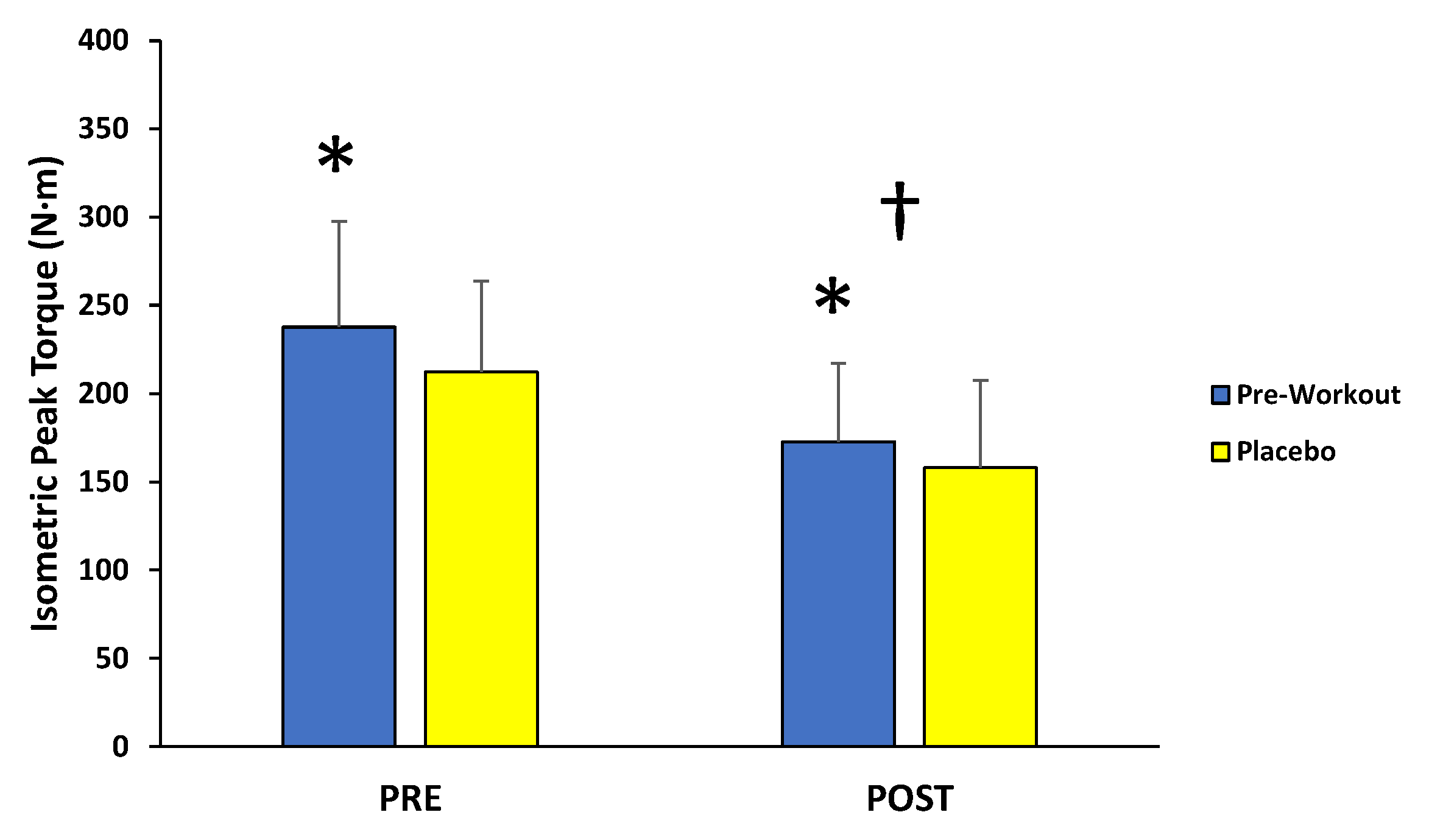

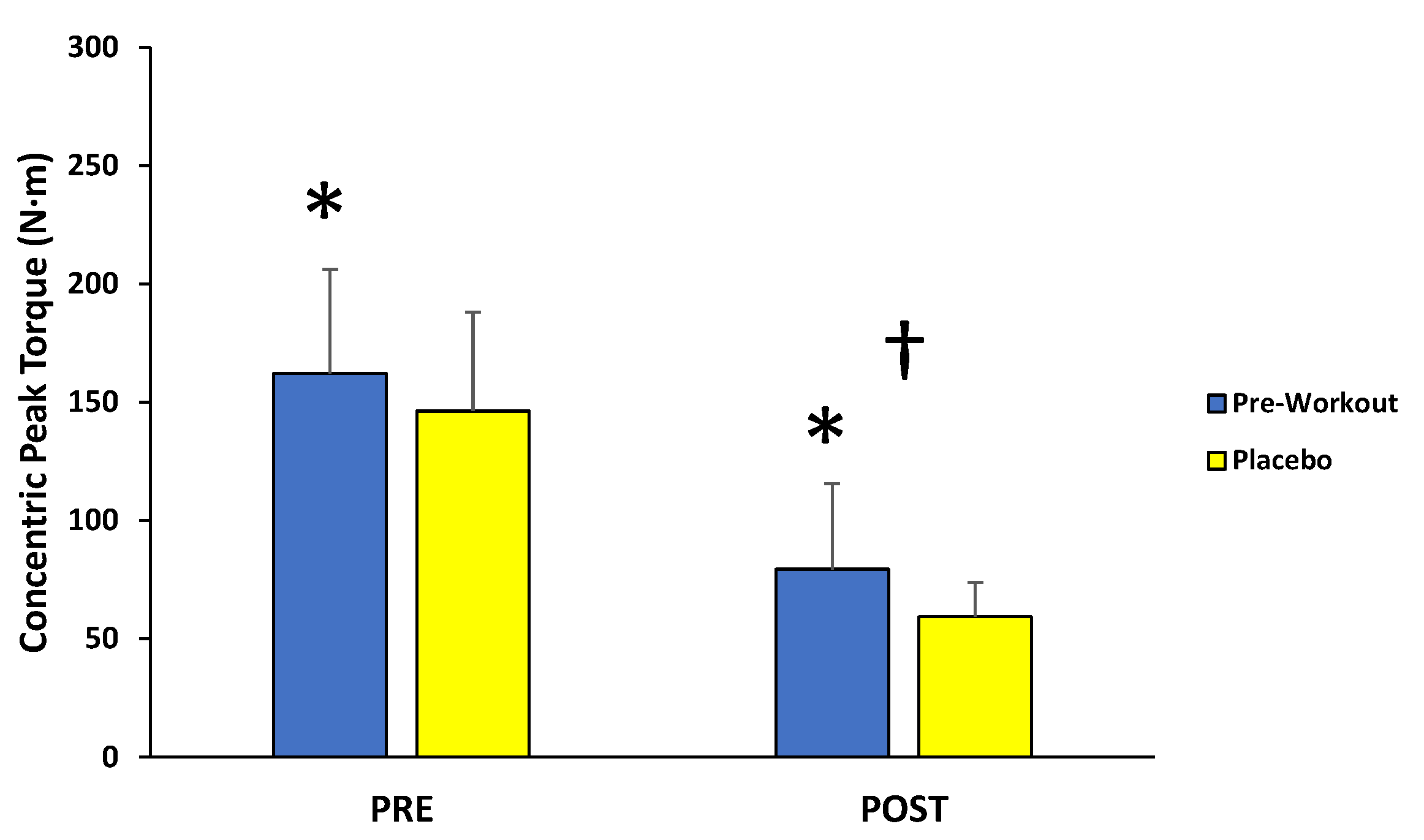

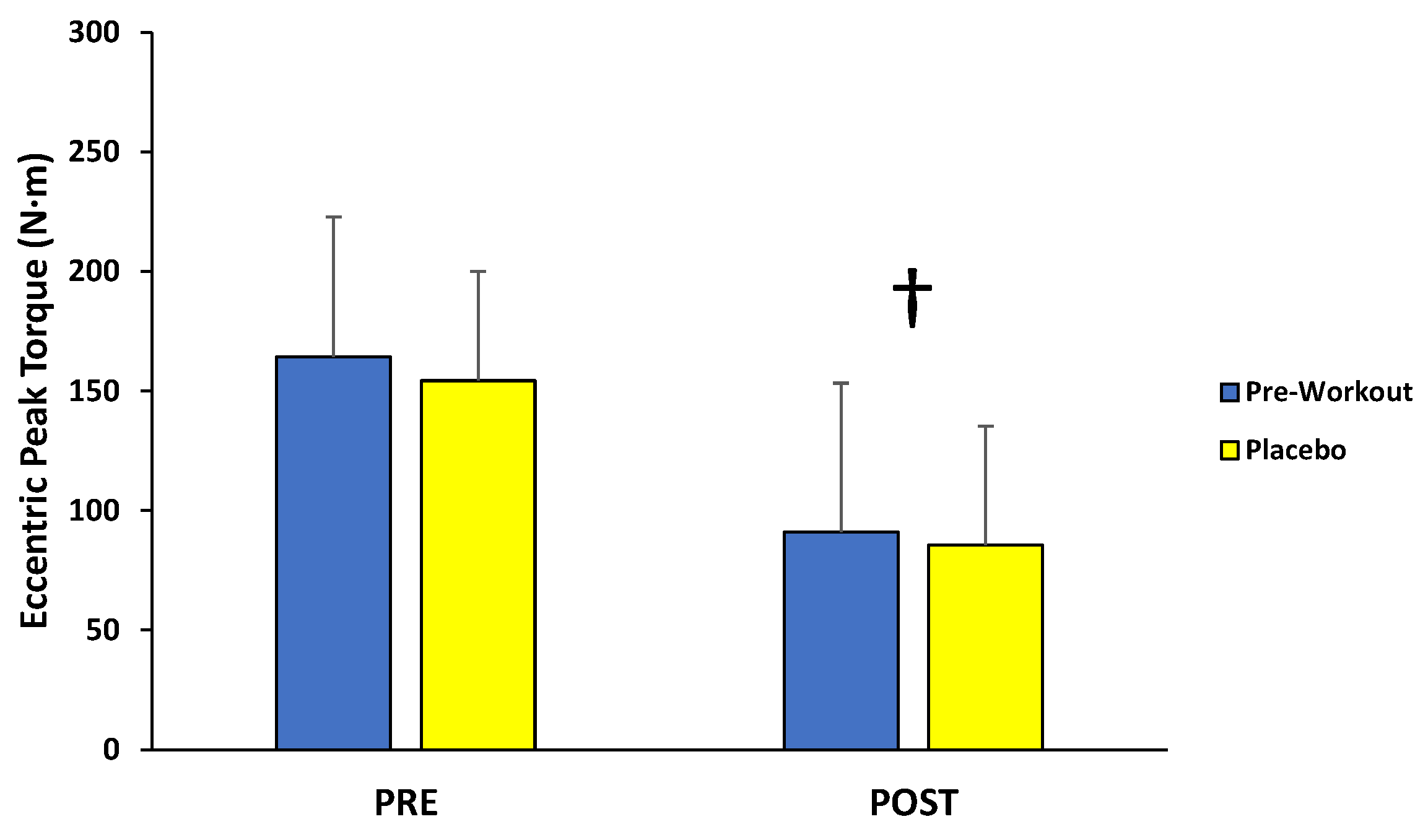

3.1. Peak Torque Production

3.1.1. Isometric Peak Torque

3.1.2. Concentric Peak Torque

3.1.3. Eccentric Peak Torque

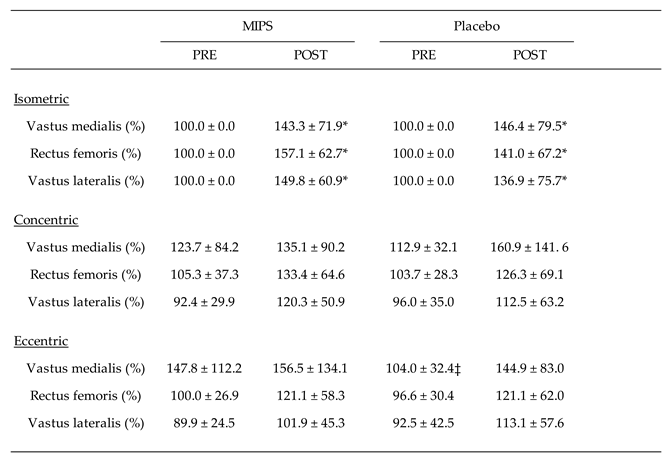

3.2. EMG Amplitude

3.2.1. Isometric Muscle Actions

3.2.2. Concentric Muscle Actions

3.2.3. Eccentric Muscle Actions

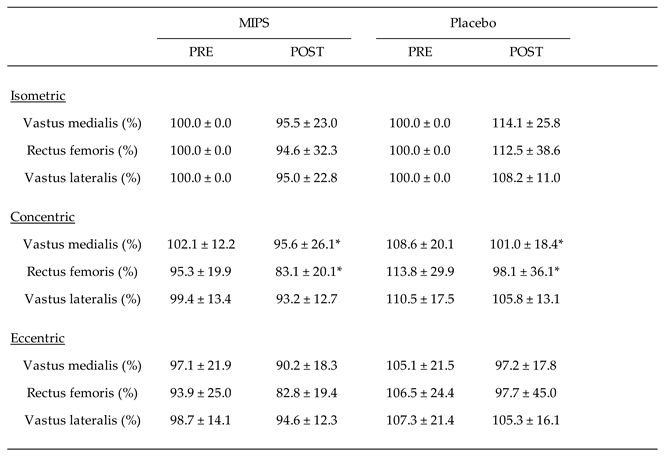

3.3. Median Power Frequency

3.3.1. Isometric Muscle Actions

3.3.2. Concentric Muscle Actions

3.3.3. Eccentric Muscle Actions

3.4. Food Log Data

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MIPS | Multi-ingredient preworkout supplement |

| MVC | Maximum voluntary contraction |

| 1-RM | One repetition maximum |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| MDF | Median power frequency |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Beyer, K.S.; Gadsen, M.; Patterson-Zuber, P.; Gonzalez, A.M. A single dose multi-ingredient pre-workout supplement enhances upper body resistance exercise performance. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1323408. [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.; Evans, C.; Mekhail, V.; Czartoryski, P.; Santana, J.C.; Antonio, J. Correction: The Effects of a Pre-workout Supplement on Measures of Alertness, Mood, and Lower-Extremity Power. Cureus 2023, 15(7), c128.

- Drwal, A.; Palka, T.; Tota, L.; Wiecha, S.; Čech, P.; Strzala, M.; Maciejczyk, M. Acute effects of multi-ingredient pre-workout dietary supplement on anaerobic performance in untrained men: a randomized, crossover, single blind study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2024, 16(1), 128. [CrossRef]

- Martinez, N.; Campbell, B.; Franek, M.; Buchanan, L.; Colquhoun, R. The effect of acute pre-workout supplementation on power and strength performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2016, 13, 29. [CrossRef]

- Negro, M.; Cerullo, G.; Perna, S.; Beretta-Piccoli, M.; Rondanelli, M.; Liguori, G.; Cena, H.; Phillips, S.M.; Cescon, C.; D’Antona, G. Effects of a Single Dose of a Creatine-Based Multi-Ingredient Pre-workout Supplement Compared to Creatine Alone on Performance Fatigability After Resistance Exercise: A Double-Blind Crossover Design Study. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 887523.

- Snyder, M.; Brewer, C.; Taylor, K. Multi-Ingredient Preworkout Supplementation Compared With Caffeine and a Placebo Does Not Improve Repetitions to Failure in Resistance-Trained Women. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2024, 19(6), 593-599. [CrossRef]

- Jagim, A.R.; Harty, P.S.; Camic, C.L. Common Ingredient Profiles of Multi-Ingredient Pre-Workout Supplements. Nutrients 2019, 11(2), 254.

- Lutsch, D.J.; Camic, C.L.; Jagim, A.R.; Stefan, R.R.; Cox, B.J.; Tauber, R.N.; Henert, S.E. Effects of a Multi-Ingredient Preworkout Supplement Versus Caffeine on Energy Expenditure and Feelings of Fatigue during Low-Intensity Treadmill Exercise in College-Aged Males. Sports (Basel) 2020, 8(10), 132. [CrossRef]

- Harty, P.S.; Zabriskie, H.A.; Erickson, J.L.; Molling, P.E.; Kerksick, C.M.; Jagim, A.R. Multi-ingredient pre-workout supplements, safety implications, and performance outcomes: a brief review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2018, 15(1), 41.

- Goldstein, E.R.; Ziegenfuss, T.; Kalman, D.; Kreider, R.; Campbell, B.; Wilborn, C.; Taylor, L.; Willoughby, D.; Stout, J.; Graves, B.S.; Wildman, R.; Ivy, J.L.; Spano, M.; Smith, A.E.; Antonio, J. International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2010, 7(1), 5.

- Guest, N.S.; VanDusseldorp, T.A.; Nelson, M.T.; Grgic, J.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Jenkins, N. D.M.; Arent, S.M.; Antonio, J.; Stout, J.R.; Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Goldstein, E.R.; Kalman, D.S.; Campbell, B.I. International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2021, 18(1), 1.

- Spradley, B.D.; Crowley, K.R.; Tai, C.Y.; Kendall, K.L.; Fukuda, D.H.; Esposito, E.N.; Moon, S.E.; Moon, J.R. Ingesting a pre-workout supplement containing caffeine, B-vitamins, amino acids, creatine, and beta-alanine before exercise delays fatigue while improving reaction time and muscular endurance. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012, 9, 28. [CrossRef]

- Trexler, E.T.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Stout, J.R.; Hoffman, J.R.; Wilborn, C.D.; Sale, C.; Kreider, R.B.; Jäger, R.; Earnest, C.P.; Bannock, L.; Campbell, B.; Kalman, D.; Ziegenfuss, T.N.; Antonio, J. International society of sports nutrition position stand: Beta-Alanine. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2015, 12, 30. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, S.J.; Blackwell, J.R.; Lord, T.; Vanhatalo, A.; Winyard, P.G.; Jones, A.M. l-Citrulline supplementation improves O2 uptake kinetics and high-intensity exercise performance in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2015, 119(4), 385-395.

- Bendahan, D.; Mattei, J.P.; Ghattas, B.; Confort-Gouny, S.; Le Guern, M.E.; Cozzone, P.J. Citrulline/malate promotes aerobic energy production in human exercising muscle. Br J Sports Med 2002, 36(4), 282-289. [CrossRef]

- Zak, R.B.; Camic, C.L.; Hill, E.C.; Monaghan, M.M.; Kovacs, A.J.; Wright, G.A. Acute effects of an arginine-based supplement on neuromuscular, ventilatory, and metabolic fatigue thresholds during cycle ergometry. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2015, 40(4), 379-385.

- Collins, P.B.; Earnest, C.P.; Dalton, R.L.; Sowinski, R.J.; Grubic, T.J.; Favot, C.J.; Coletta, A.M.; Rasmussen, C.; Greenwood, M.; Kreider, R.B. Short-Term Effects of a Ready-to-Drink Pre-Workout Beverage on Exercise Performance and Recovery. Nutrients 2017, 9(8), 823.

- Jagim, A.R.; Jones, M.T.; Wright, G.A.; St Antoine, C.; Kovacs, A.; Oliver, J.M. The acute effects of multi-ingredient pre-workout ingestion on strength performance, lower body power, and anaerobic capacity. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2016, 13, 11.

- Stratton, M.T.; Siedler, M.R.; Harty, P.S.; Rodriguez, C.; Boykin, J.R.; Green, J.J.; Keith, D.S.; White, S.J.; DeHaven, B.; Williams, A.D.; Tinsley, G.M. The influence of caffeinated and non-caffeinated multi-ingredient pre-workout supplements on resistance exercise performance and subjective outcomes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2022, 19(1), 126-149. [CrossRef]

- Bergstrom, H.C.; Byrd, M.T.; Wallace, B.J.; Clasey, J.L. Examination of a Multi-ingredient Preworkout Supplement on Total Volume of Resistance Exercise and Subsequent Strength and Power Performance. J Strength Cond Res 2018, 32(6), 1479-1490. [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, G.M.; Hamm, M.A.; Hurtado, A.K.; Cross, A.G.; Pineda, J.G.; Martin, A.Y.; Uribe, V.A.; Palmer, T.B. Effects of two pre-workout supplements on concentric and eccentric force production during lower body resistance exercise in males and females: a counterbalanced, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2017, 14, 46.

- Cameron, M.; Camic, C.L.; Doberstein, S.; Erickson, J.L.; Jagim, A.R. The acute effects of a multi-ingredient pre-workout supplement on resting energy expenditure and exercise performance in recreationally active females. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2018, 15, 1.

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Walsh, A.L.; Ratamess, N.A.; Kang, J.; Hoffman, J.R. Effect of a pre-workout energy supplement on acute multi-joint resistance exercise. J Sports Sci Med 2011, 10(2), 261-266.

- Anders, J.P.V.; Smith, C.M.; Keller, J.L.; Hill, E.C.; Housh, T.J.; Schmidt, R.J.; Johnson, G.O. Inter- and Intra-Individual Differences in EMG and MMG during Maximal, Bilateral, Dynamic Leg Extensions. Sports (Basel) 2019, 7(7), 175. [CrossRef]

- Camic, C.L.; Housh, T.J.; Zuniga, J.M.; Russell Hendrix, C.; Bergstrom, H.C.; Traylor, D.A.; Schmidt, R.J.; Johnson, G.O. Electromyographic and mechanomyographic responses across repeated maximal isometric and concentric muscle actions of the leg extensors. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2013, 23(2), 342-348.

- Camic, C.L.; Housh, T.J.; Zuniga, J.M.; Bergstrom, H.C.; Schmidt, R.J.; Johnson, G.O. Mechanomyographic and electromyographic responses during fatiguing eccentric muscle actions of the leg extensors. J Appl Biomech 2014, 30(2), 255-261. [CrossRef]

- Perry-Rana, S.R.; Housh, T.J.; Johnson, G.O.; Bull, A.J.; Cramer, J.T. MMG and EMG responses during 25 maximal, eccentric, isokinetic muscle actions. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003, 35(12), 2048-2054. [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Gao, J.; Dawazhuoma; Mi, X.; Ciwang; Bianba. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: evaluating the efficacy of isokinetic muscle strengthening training in improving knee osteoarthritis outcomes. J Orthop Surg Res 2025, 20(1), 95.

- Reyes-Ferrada,W.; Chirosa-Rios, L.; Martinez-Garcia, D.; Rodríguez-Perea, Á.; Jerez-Mayorga, D. Reliability of trunk strength measurements with an isokinetic dynamometer in non-specific low back pain patients: A systematic review. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2022, 35(5), 937-948. [CrossRef]

- Lynn, P.A. Direct on-line estimation of muscle fiber conduction velocity by surface electromyography. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 1979, 26(10), 564-571.

- Basmajian, J. V.; De Luca, C. J. Muscles Alive: Their functions revealed by electromyography, 5th ed. Williams & Wilkins; United States of America, 1985; pp. 67-71.

- Broman, H.; Bilotto, G.; De Luca, C.J. Myoelectric signal conduction velocity and spectral parameters: influence of force and time. J Appl Physiol 1985, 58(5), 1428-1437. [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2000, 10(5), 361-374.

- Astorino, T.A.; Roberson, D.W. Efficacy of acute caffeine ingestion for short-term high-intensity exercise performance: a systematic review. J Strength Cond Res 2010, 24(1), 257-265. [CrossRef]

- Astorino, T.A.; Terzi, M.N.; Roberson, D.W.; Burnett, T.R. Effect of caffeine intake on pain perception during high-intensity exercise. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2011, 21(1), 27-32. [CrossRef]

- Kalmar, J.M.; Cafarelli, E. Caffeine: a valuable tool to study central fatigue in humans? Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2004, 32(4), 143-147.

- Bode-Böger, S.M.; Böger, R.H.; Creutzig, A.; Tsikas, D.; Gutzki, F.M.; Alexander, K.; Frölich, J.C. L-arginine infusion decreases peripheral arterial resistance and inhibits platelet aggregation in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond) 1994, 87(3), 303-310.

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Townsend, J.R.; Pinzone, A.G.; Hoffman, J.R. Supplementation with Nitric Oxide Precursors for Strength Performance: A Review of the Current Literature. Nutrients 2023, 15(3), 660. [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, P.L.; Limonta, E.; Riboli, A.; Bosio, A.; Scurati, R.; Esposito, F. Effects of Acute Carnosine and β-Alanine on Isometric Force and Jumping Performance. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2016, 11(3), 344-349. [CrossRef]

- Montalvo-Alonso, J.J.; Del Val-Manzano, M.; Cerezo-Telléz, E.; Ferragut, C.; Valadés, D.; Rodríguez-Falces, J.; Pérez-López, A. Acute caffeine intake improves muscular strength, power, and endurance performance, reversing the time-of-day effect regardless of muscle activation level in resistance-trained males: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Appl Physiol 2025, 10.1007/s00421-025-05820-3, Advance online publication.

- Kalmar, J.M.; Cafarelli, E. Effects of caffeine on neuromuscular function. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999, 87(2), 801-808. [CrossRef]

- Behrens, M.; Mau-Moeller, A.; Weippert, M.; Fuhrmann, J.; Wegner, K.; Skripitz, R.; Bader, R.; Bruhn, S. Caffeine-induced increase in voluntary activation and strength of the quadriceps muscle during isometric, concentric and eccentric contractions. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 10209. [CrossRef]

- Alvares, T.S.; Conte-Junior, C.A.; Silva, J.T.; Paschoalin, V.M. Acute L-Arginine supplementation does not increase nitric oxide production in healthy subjects. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012, 9(1), 54.

- Aguiar, A.F.; Balvedi, M.C.; Buzzachera, C.F.; Altimari, L.R.; Lozovoy, M.A.; Bigliassi, M.; Januário, R.S.; Pereira, R.M.; Sanches, V.C.; da Silva, D.K.; Muraoka, G.A. L-Arginine supplementation does not enhance blood flow and muscle performance in healthy and physically active older women. Eur J Nutr 2016, 55(6), 2053-2062. [CrossRef]

- Glenn, J.M.; Gray, M.; Wethington, L.N.; Stone, M.S.; Stewart, R.W Jr.; Moyen, N.E. Acute citrulline malate supplementation improves upper- and lower-body submaximal weightlifting exercise performance in resistance-trained females. Eur J Nutr 2017, 56(2), 775-784.

- Gonzalez, A.M.; Yang, Y.; Mangine, G.T.; Pinzone, A.G.; Ghigiarelli, J.J.; Sell, K.M. Acute Effect of L-Citrulline Supplementation on Resistance Exercise Performance and Muscle Oxygenation in Recreationally Resistance Trained Men and Women. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2023, 8(3), 88. [CrossRef]

- Sale, C.; Hill, C.A.; Ponte, J.; Harris, R.C. β-alanine supplementation improves isometric endurance of the knee extensor muscles. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2012, 9(1), 26.

- Kaczka, P.; Batra, A.; Kubicka, K.; Maciejczyk, M.; Rzeszutko-Bełzowska, A.; Pezdan-Śliż, I.; Michałowska-Sawczyn, M.; Przydział, M.; Płonka, A.; Cięszczyk, P.; Humińska-Lisowska, K.; Zając, T. Effects of Pre-Workout Multi-Ingredient Supplement on Anaerobic Performance: Randomized Double-Blind Crossover Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17(21), 8262. [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J.; Mikulic, P.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Bishop, D.J.; Pedisic, Z. The Influence of Caffeine Supplementation on Resistance Exercise: A Review. Sports Med 2019, 49(1), 17-30.

- Kang, Y.; Dillon, K.N.; Martinez, M.A.; Maharaj, A.; Fischer, S.M.; Figueroa, A. L-Citrulline Supplementation Improves Arterial Blood Flow and Muscle Oxygenation during Handgrip Exercise in Hypertensive Postmenopausal Women. Nutrients 2024, 16(12), 1935. [CrossRef]

- Duchateau, J.; Enoka, R.M. Neural control of lengthening contractions. J Exp Biol 2016, 219(Pt 2), 197-204. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).