Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

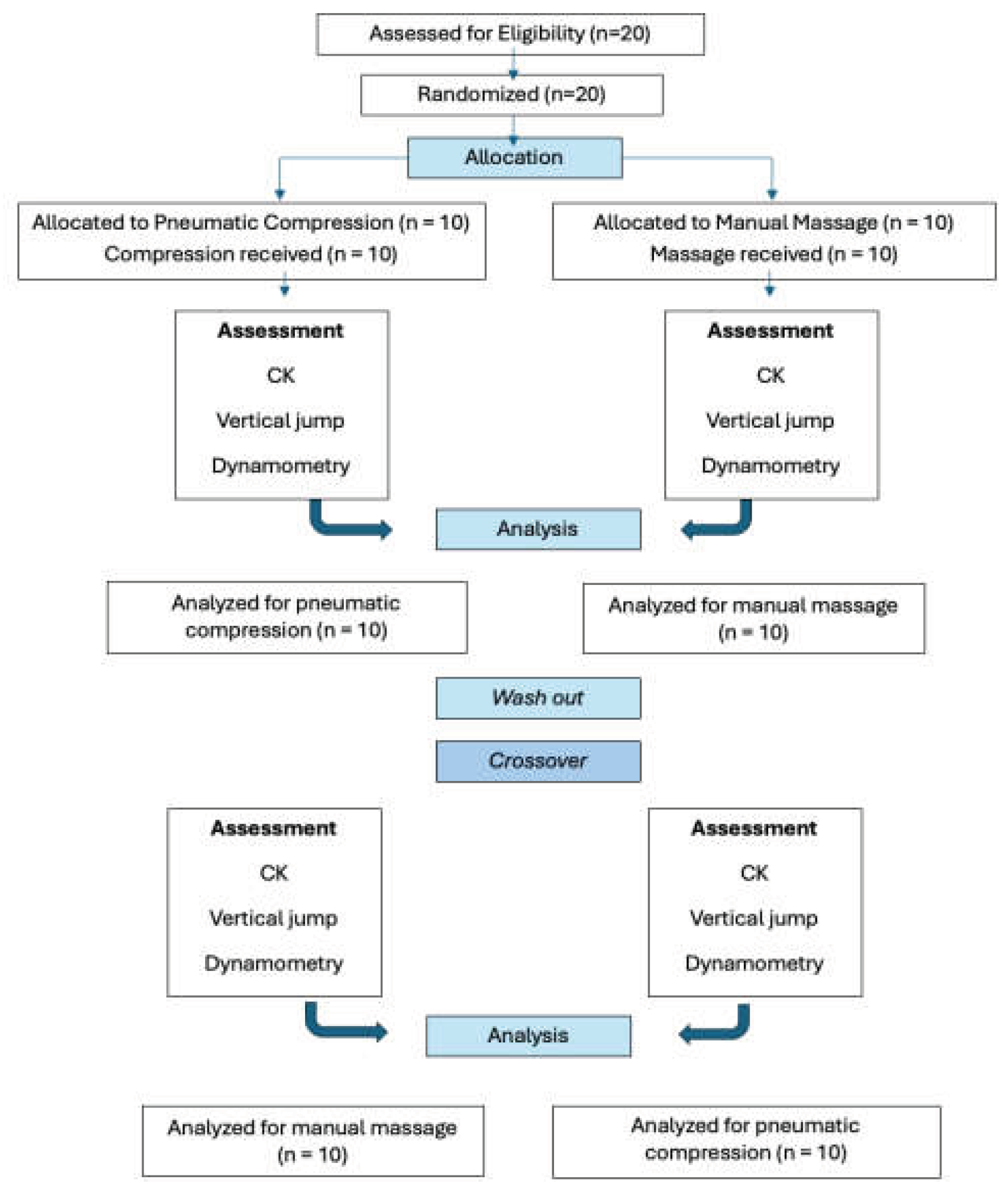

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Instruments

2.4.1. Intermittent Pneumatic Compression (IPC)

2.4.2. Manual Massage (MM)

2.4.3. Measurements

2.4.4. Vertical Jump Performance (VJ):

2.4.5. Isometric Voluntary Contraction (IVC):

2.5. Statistical Analysis

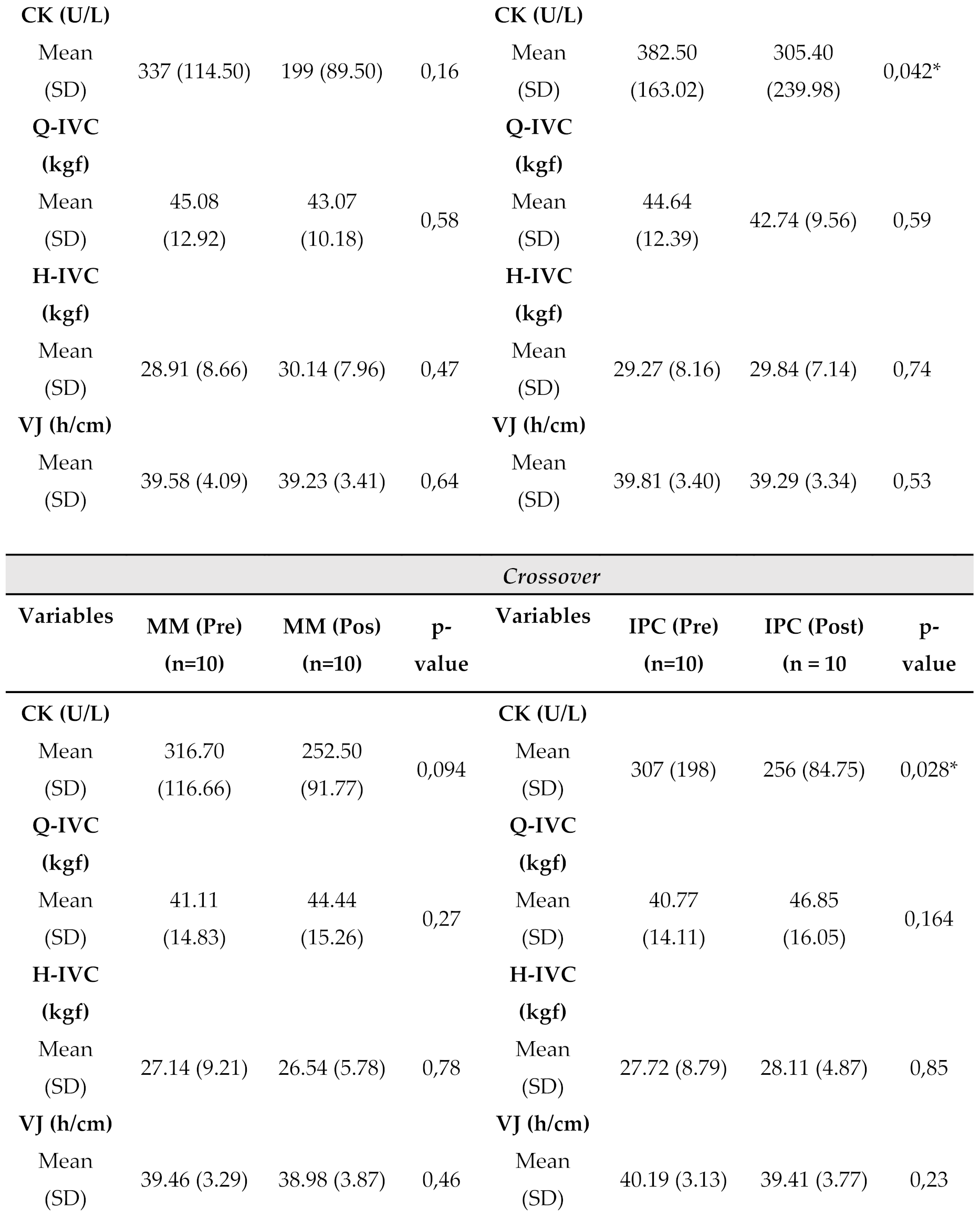

3. Results

3.1. Serum CK Concentration

3.2. Isometric Voluntary Contraction (IVC)

3.3. Vertical Jump Performance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akyildiz, Z.; Ocak, Y.; Clemente, F.M.; Birgonul, Y.; Günay, M.; Nobari, H. Monitoring the Post-Match Neuromuscular Fatigue of Young Turkish Football Players. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13835. [Google Scholar]

- Brownstein, C.G.; Dent, J.P.; Parker, P.; Hicks, K.M.; Howatson, G.; Goodall, S.; Thomas, K. Etiology and Recovery of Neuromuscular Fatigue Following Competitive Soccer Match-Play. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 831. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelec, M.; Mccall, A.; Carling, C. Recovery in Soccer : Part II-Recovery Strategies . Physical Performance and Subjective Ratings after a Soccer-Specific Exercise Simulation : Comparison of Natural Grass versus Artificial Turf. 2013.

- Robineau, J.; Jouaux, T.; Lacroix, M.; Babault, N. Neuromuscular Fatigue Induced by a 90-Minute Soccer Game Modeling. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 2012, 26, 555–562. [Google Scholar]

- Poppendieck, W.; Wegmann, M.; Ferrauti, A.; Kellmann, M.; Pfeiffer, M.; Meyer, T. Massage and Performance Recovery: A Meta-Analytical Review. Sports Med 2016, 46, 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Weerapong, P.; Hume, P.A.; Kolt, G.S. The Mechanisms of Massage and Effects on Performance, Muscle Recovery and Injury Prevention. Sports Med 2005, 35, 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dakić, M.; Toskić, L.; Ilić, V.; Đurić, S.; Dopsaj, M.; Šimenko, J. The Effects of Massage Therapy on Sport and Exercise Performance: A Systematic Review. Sports 2023, 11, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, J.E.; Peeler, J.D.; Barr, M.J.; Gardiner, P.F.; Cornish, S.M. The Impact of a Single Bout of Intermittent Pneumatic Compression on Performance, Inflammatory Markers, and Myoglobin in Football Athletes. 2020, 33–38.

- Cochrane, D.; Booker, H.; Mundel, T.; Barnes, M. Does Intermittent Pneumatic Leg Compression Enhance Muscle Recovery after Strenuous Eccentric Exercise? Int J Sports Med 2013, 34, 969–974. [Google Scholar]

- Overmayer, R.G.; Driller, M.W. Pneumatic Compression Fails to Improve Performance Recovery in Trained Cyclists. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2018, 13, 490–495. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, J.; Howatson, G.; Van Someren, K.; Leeder, J.; Pedlar, C. Compression Garments and Recovery from Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Meta-Analysis. Br J Sports Med 2014, 48, 1340–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Hader, K.; Rumpf, M.C.; Hertzog, M.; Kilduff, L.P.; Girard, O.; Silva, J.R. Monitoring the Athlete Match Response: Can External Load Variables Predict Post-Match Acute and Residual Fatigue in Soccer? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Sports Med - Open 2019, 5, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Heapy, A.M.; Hoffman, M.D.; Verhagen, H.H.; Thompson, S.W.; Dhamija, P.; Sandford, F.J.; Cooper, M.C. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Manual Therapy and Pneumatic Compression for Recovery from Prolonged Running – an Extended Study. Research in Sports Medicine 2018, 26, 354–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abrantes, R.; Monteiro, E.R.; Vale, R.G.D.S.; De Castro, J.B.P.; Bodell, N.; Hoogenboom, B.J.; Leitão, L.; Serra, R.; Vianna, J.M.; Da Silva Novaes, J. The Acute Effect of Two Massage Techniques on Functional Capability and Balance in Recreationally Trained Older Adult Women: A Cross-over Study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2021, 28, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, G.Z.; Button, D.C.; Drinkwater, E.J.; Behm, D.G. Foam Rolling as a Recovery Tool after an Intense Bout of Physical Activity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2014, 46, 131–142. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, R.D.; Prestes, J.; Rosa, C. Acute Effect of Resistance Training Volume on Hormonal Responses in Trained Men. 2011, 2, 322–328.

- Ferreira, J.; Da Silva Carvalho, R.; Barroso, T.; Szmuchrowski, L.; Śledziewski, D. Effect of Different Types of Recovery on Blood Lactate Removal After Maximum Exercise. Polish Journal of Sport and Tourism 2011, 18, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto-Ramos, J.; Moreira, T.; Costa, F.; Tavares, H.; Cabral, J.; Costa-Santos, C.; Barroso, J.; Sousa-Pinto, B. Handheld Dynamometer Reliability to Measure Knee Extension Strength in Rehabilitation Patients—A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268254. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, P.B.; Ruby, D.; Bush-Joseph, C.A. Muscle Soreness and Delayed-Onset Muscle Soreness. Clinics in Sports Medicine 2012, 31, 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Zainuddin, Z.; Newton, M.; Sacco, P.; Nosaka, K. 174-180 by the National Athletic Trainers’ Association, Inc; †University Technology of Malaysia. Journal of Athletic Training 2005, 40, 174–180. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Li, L.; Gong, Y.; Zhu, R.; Xu, J.; Zou, J.; Chen, X. Massage Alleviates Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness after Strenuous Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 747. [Google Scholar]

- Rasooli, S.A.; Jahromi, M.K. Influence of Massage, Active and Passive Recovery on Swimming Performance and Blood Lactate. 2012, 52, 122–127.

- Wiecha, S.; Jarocka, M.; Wiśniowski, P.; Cieśliński, M.; Price, S.; Makaruk, B.; Kotowska, J.; Drabarek, D.; Cieśliński, I.; Sacewicz, T. The Efficacy of Intermittent Pneumatic Compression and Negative Pressure Therapy on Muscle Function, Soreness and Serum Indices of Muscle Damage: A Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2021, 13, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Maia, F.; Machado, M.V.; Silva, G.; Yuzo Nakamura, F.; Ribeiro, J. Hemodynamic Effects of Intermittent Pneumatic Compression on Athletes: A Double-Blinded Randomized Crossover Study. 2024, 19, 932–938.

- Maia, F.; Nakamura, F.Y.; Pimenta, R.; Tito, S.; Sousa, H.; Ribeiro, J. Intermittent Pneumatic Compression May Reduce Muscle Soreness but Does Not Improve Neuromuscular Function Following Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance 2025, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert, J.E.; Sforzo, G.A.; Swensen, T. The Effects of Massage on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2003, 37, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dawson, L.G.; Dawson, K.A.; Tiidus, P.M. Evaluating the Influence of Massage on Leg Strength, Swelling, and Pain Following a Half-Marathon. ©Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2004, 3, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Davis, H.L.; Alabed, S.; Chico, T.J.A. Effect of Sports Massage on Performance and Recovery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2020, 6, e000614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oliveira Abrantes, R.; Monteiro, E.; Ribeiro, M.; Fiuza, A.; Cesar De Oliveira Muniz Cunha, J. Massage Acutely Increased Muscle Strength and Power Force; 2019.

- Zuj, K.A.; Prince, C.N.; Hughson, R.L.; Peterson, S.D. Enhanced Muscle Blood Flow with Intermittent Pneumatic Compression of the Lower Leg during Plantar Flexion Exercise and Recovery. J Appl Physiol 2018, 124, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, O.; Douzi, W.; Theurot, D.; Bosquet, L.; Dugué, B. An Evidence-Based Approach for Choosing Post-Exercise Recovery Techniques to Reduce Markers of Muscle Damage, Soreness, Fatigue, and Inflammation: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 403. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchetti, P. Current Sample Size Conventions: Flaws, Harms, and Alternatives. BMC Med. 2010, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Senn, S. Seven Myths of Randomisation in Clinical Trials. Statistics in Medicine 2013, 32, 1439–1450. [Google Scholar]

| Mean ± SD | 95%CI | CV (%) | |||

| Age (years) | 18.65 ± 0.67 | 18.40 – 18.90 | 3.59 | ||

| Height (m) | 1.78 ± 0.07 | 1.75 – 1.81 | 3.93 | ||

| Weight (kg) | 72.8 ± 6.99 | 70.19 – 75.41 | 9.60 | ||

| Body Fat (%) | 12.3 ± 1.63 | 11.69 – 12.91 | 13.25 | ||

| Variables | IPC (Pre)(n=10) | IPC (Post)(n=10) | p-value | Variables | MM (Pre) (n=10) | MM (Post)(n=10) | p-value |

| |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).