Submitted:

06 March 2025

Posted:

06 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Method

2.3. Performance Outcomes and Exercise Protocol

2.4. Supplementation Intake

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics of Participants

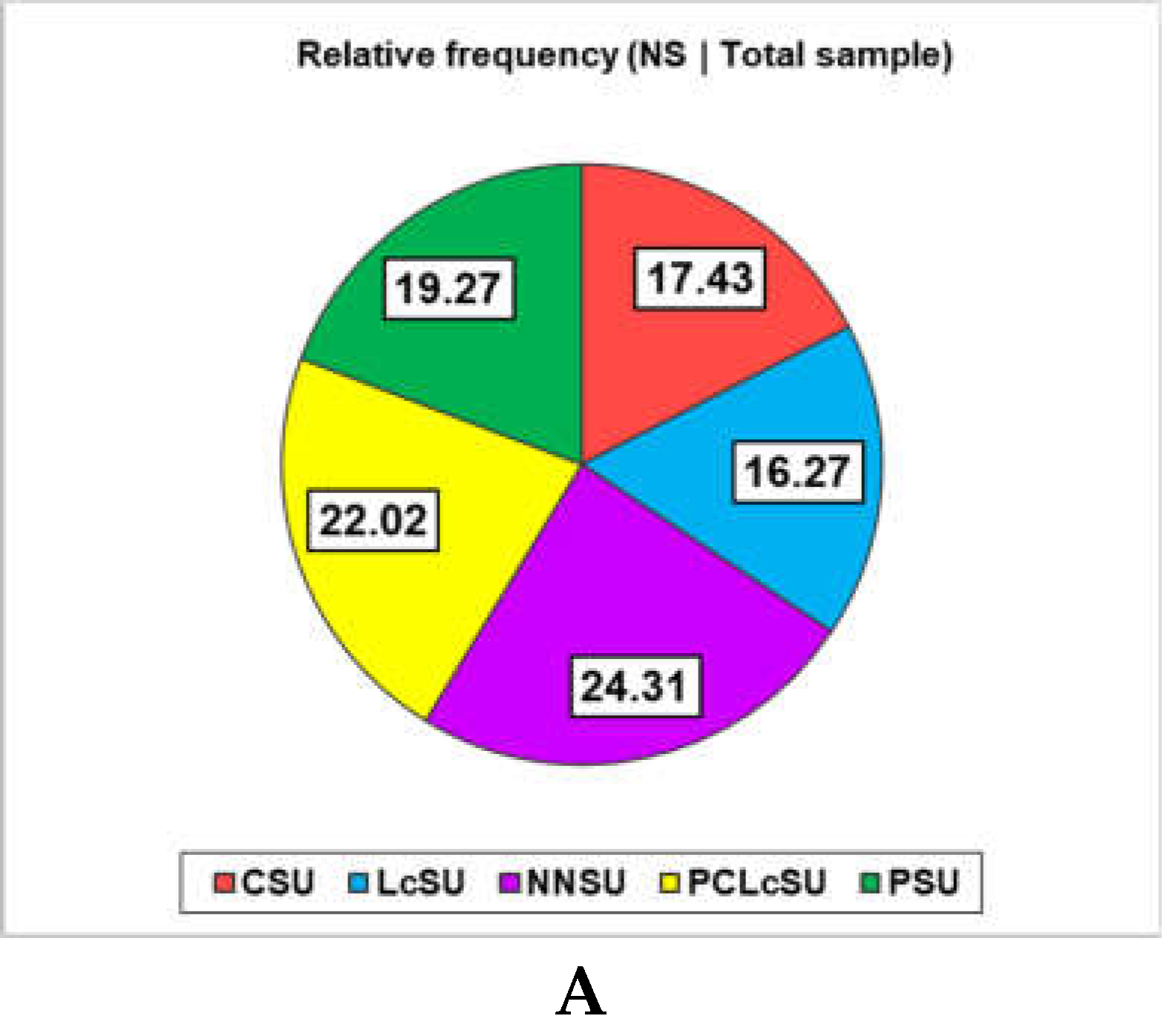

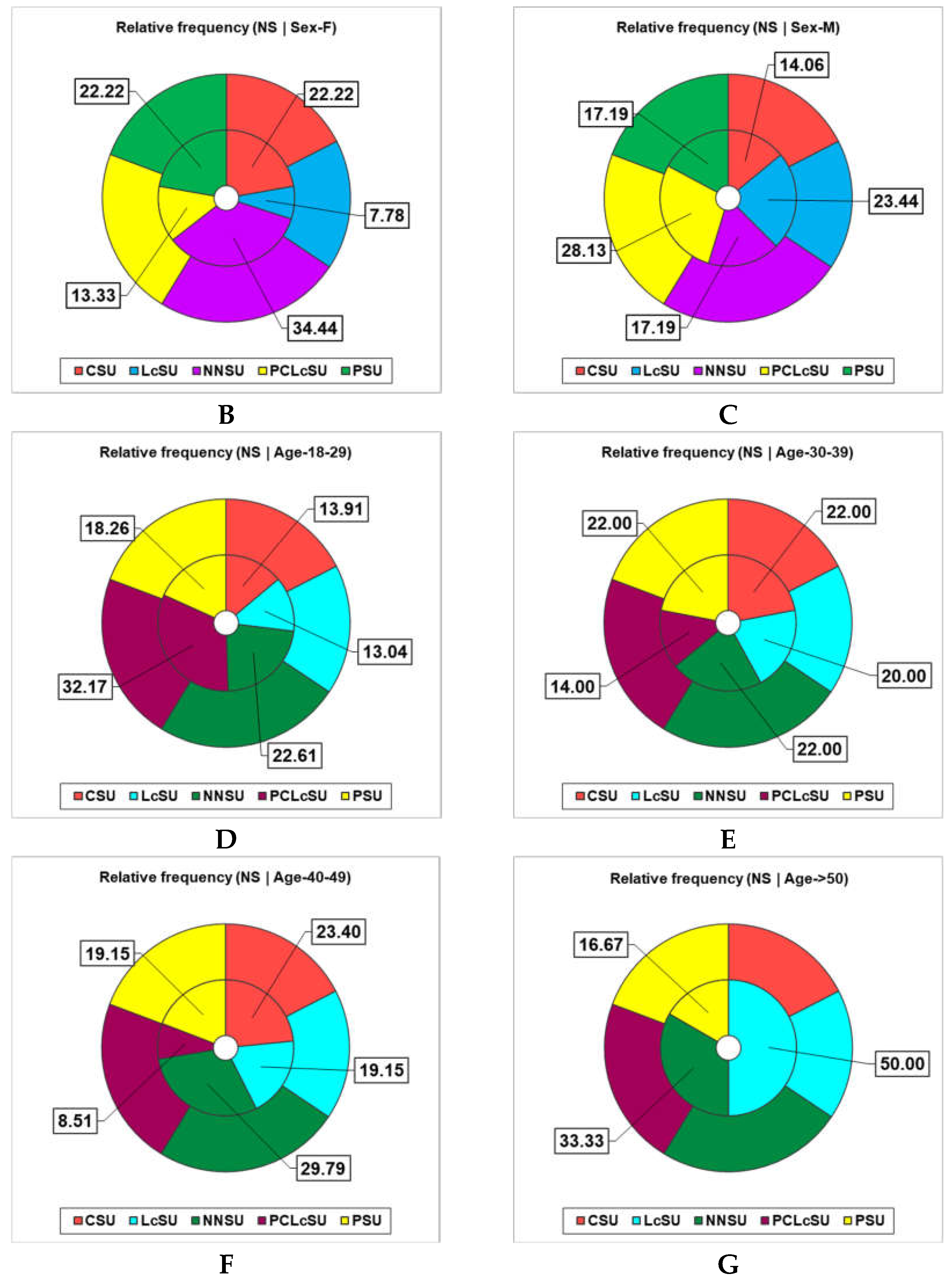

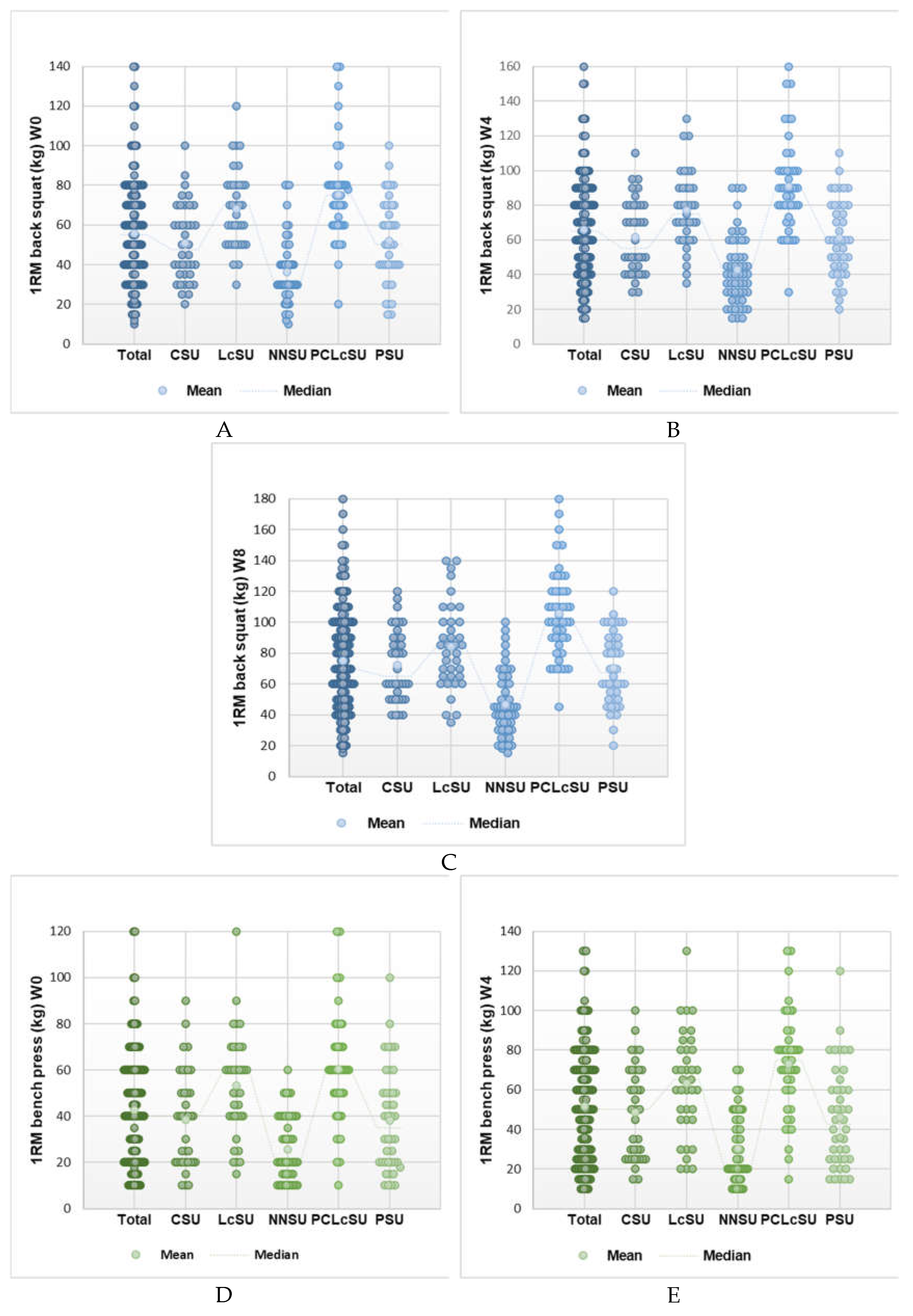

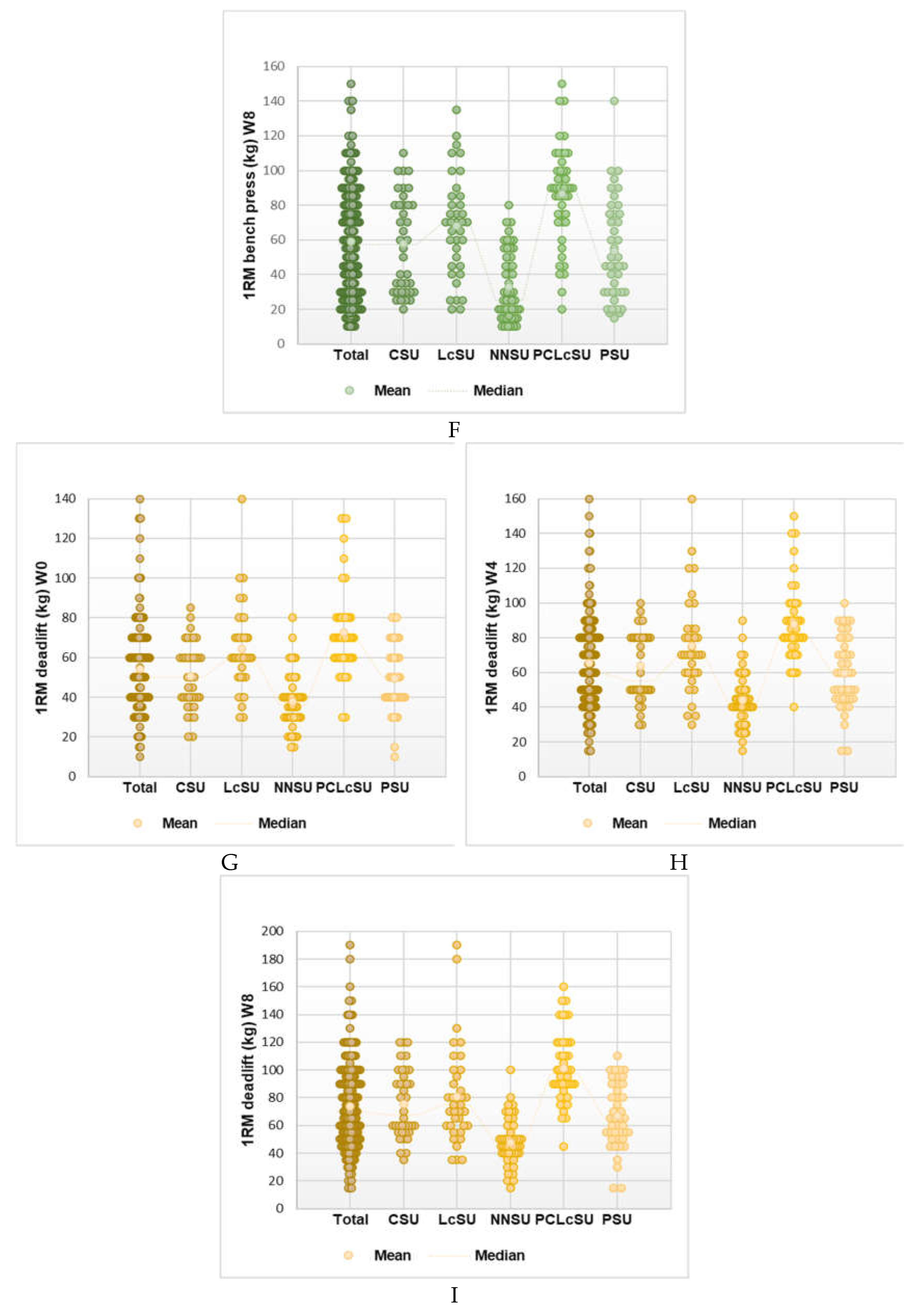

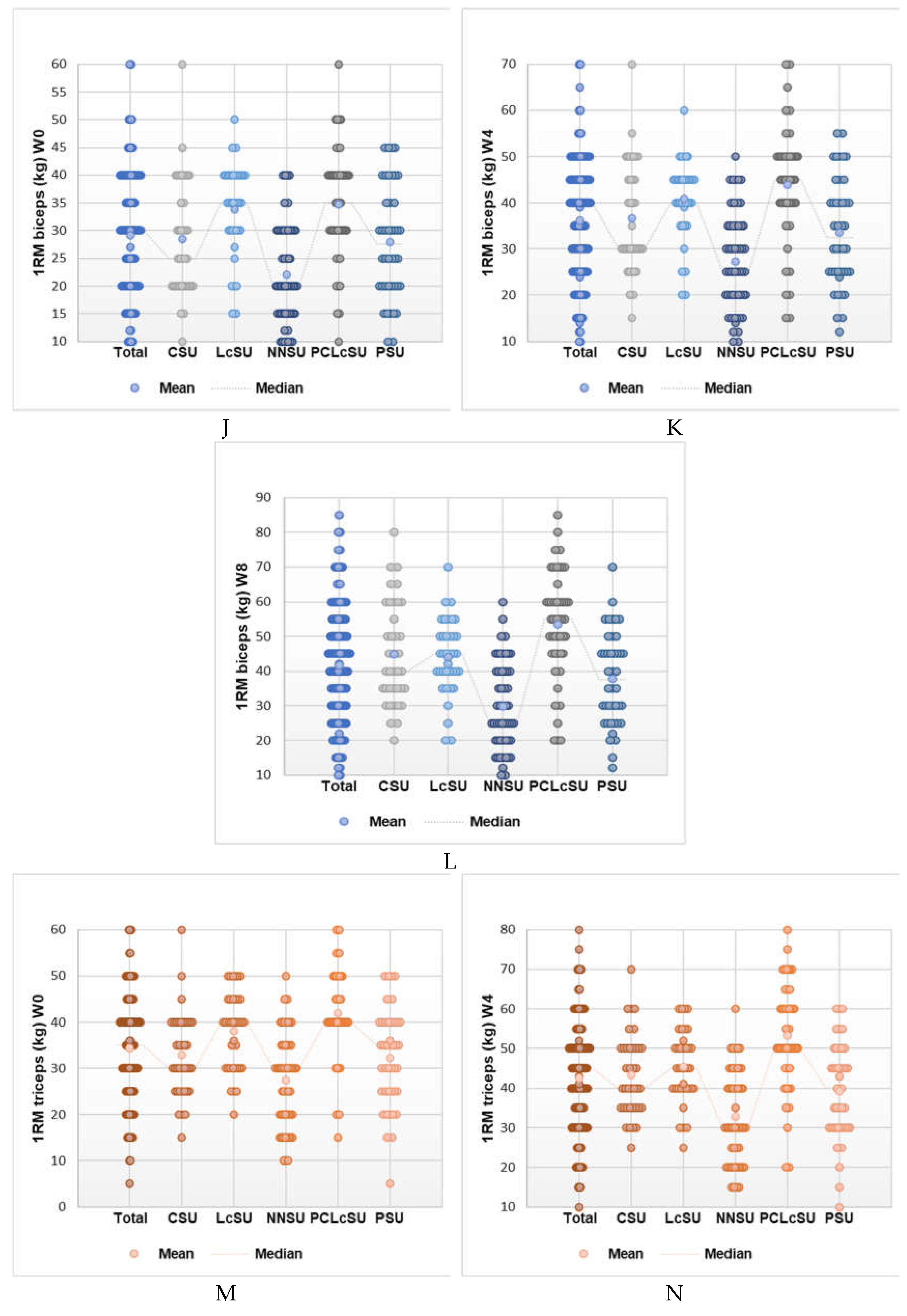

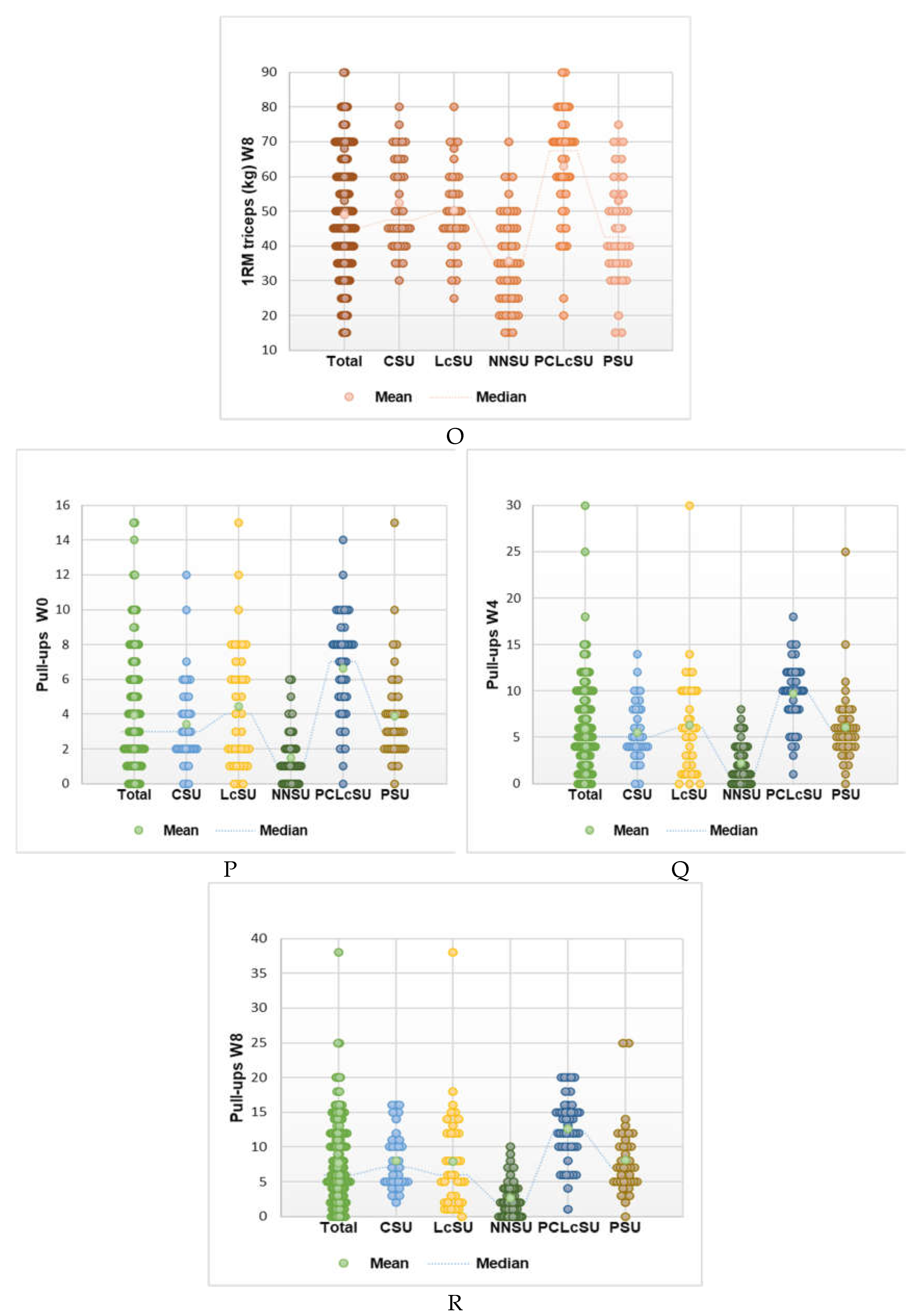

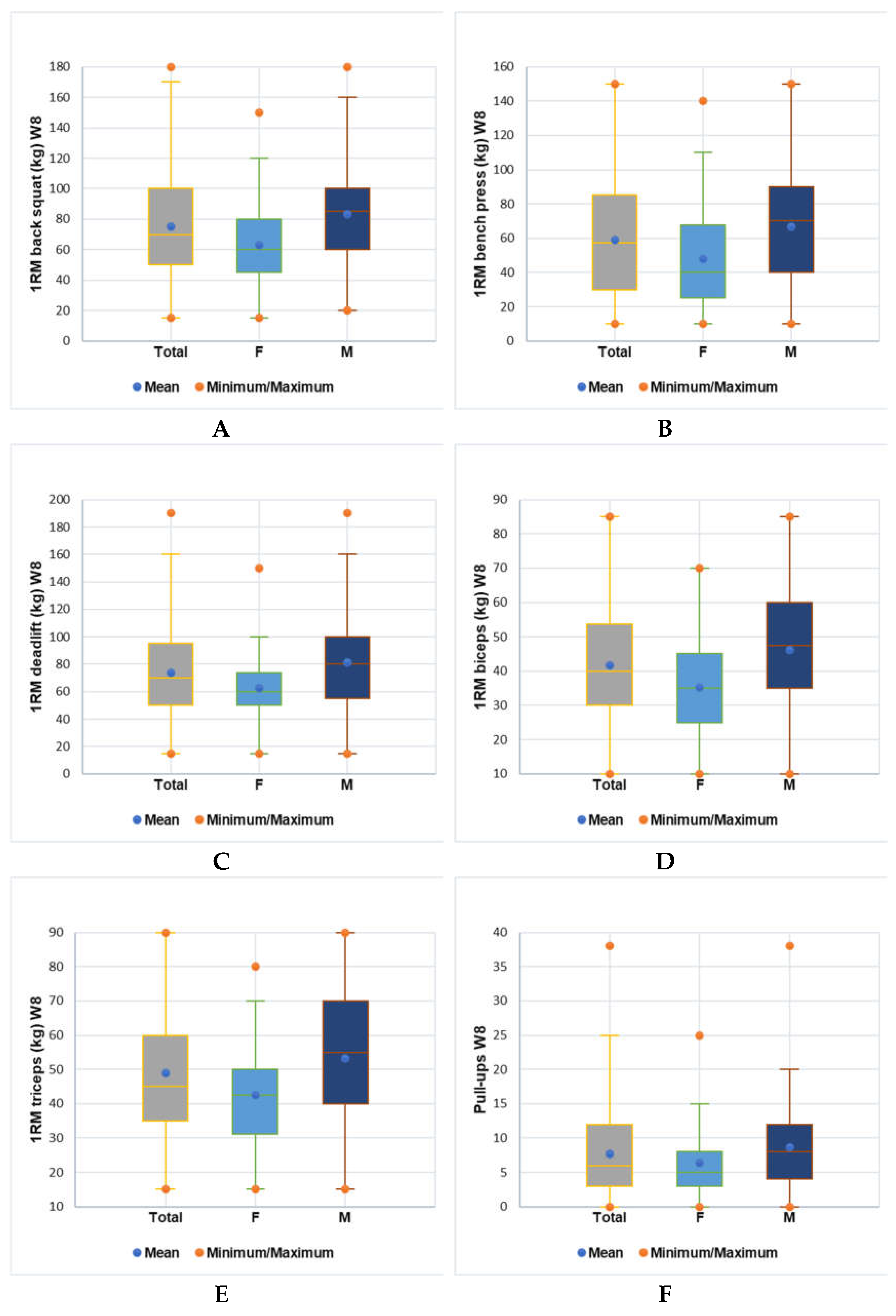

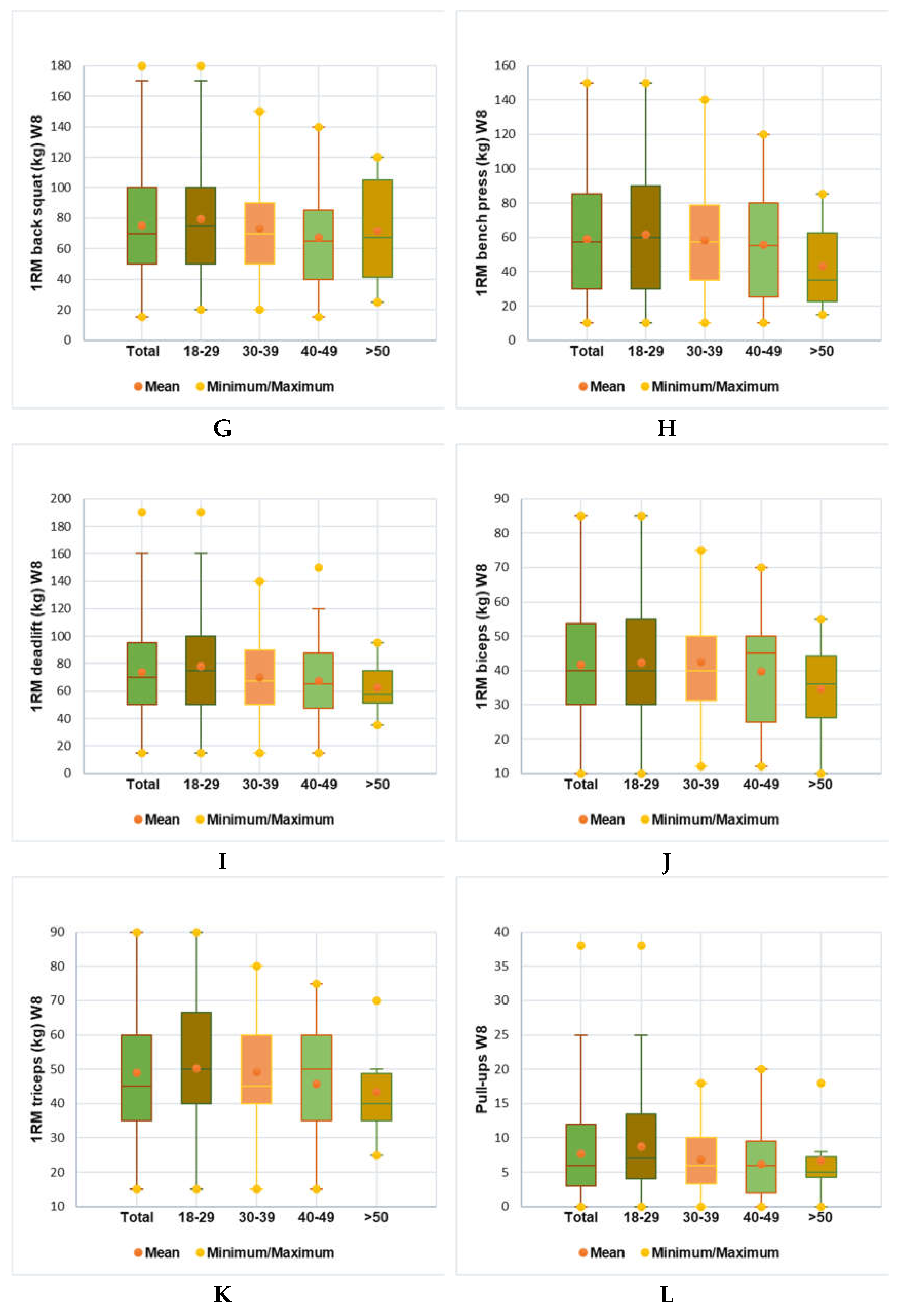

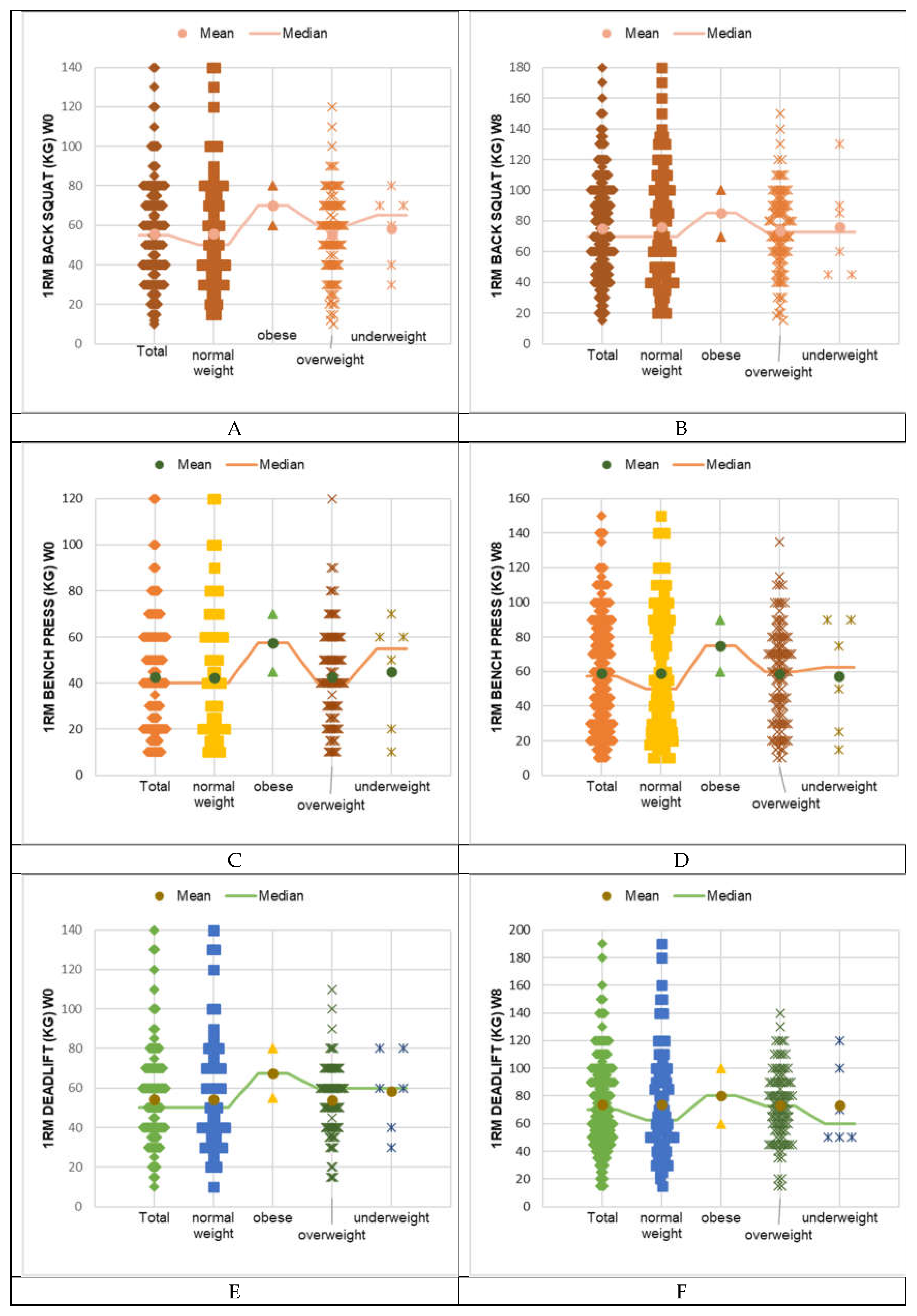

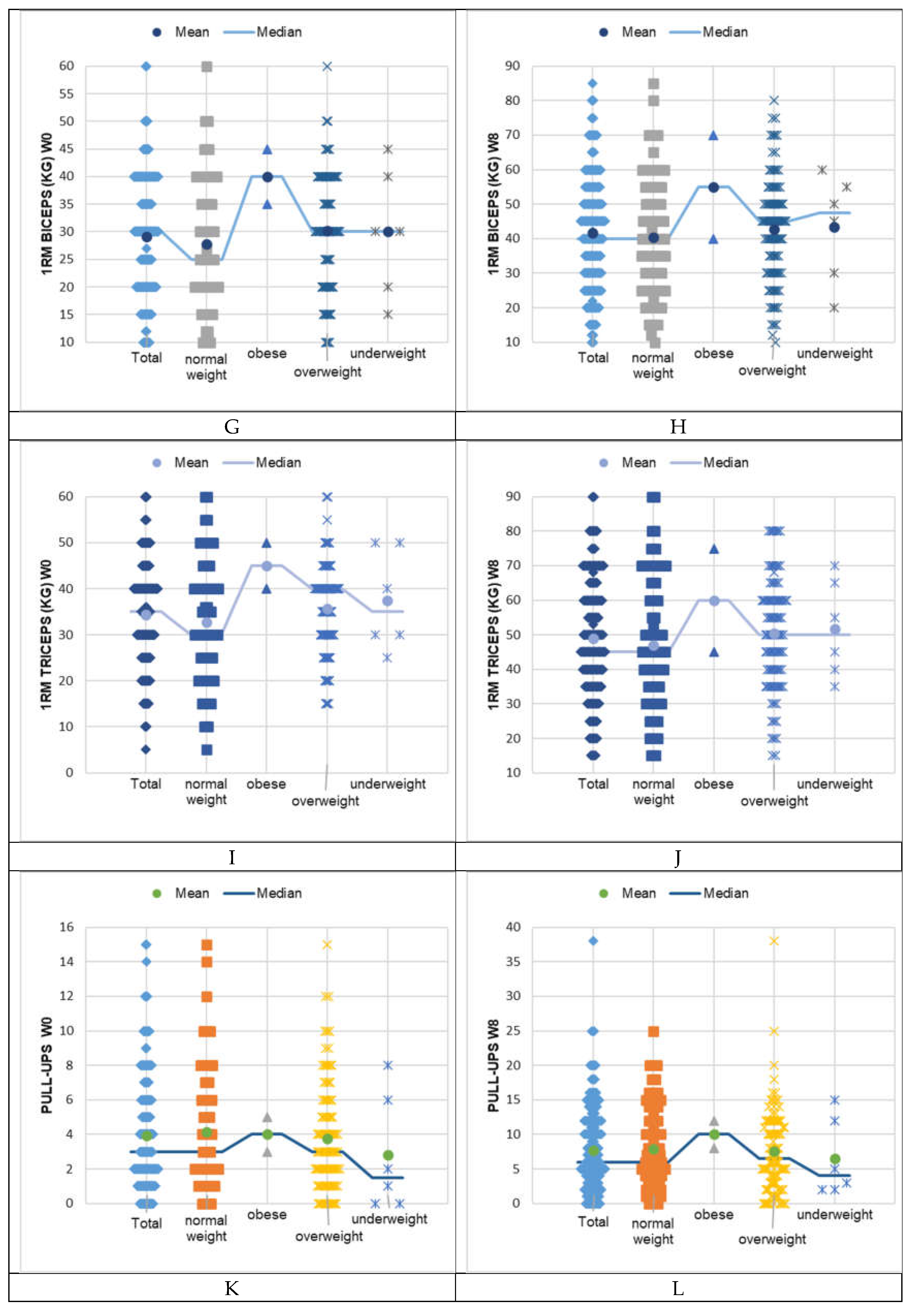

3.2. Nutritional Supplements Consumption and Gym Performances

4. Discussion

Limitations:

- Individual factors: the study mentions several factors that may influence strength performance, such as training history, genetic predisposition, and recovery strategies, but these individual differences were not fully controlled.

- Training protocol consistency: while resistance training was implemented over 8 weeks, the consistency of the training protocol (e.g., intensity, frequency, volume, and recovery) may have varied between participants. Variability in adherence to the training regimen could have affected the outcomes.

- Long-term effects: the study only investigated short-term (8-week) effects. A more extended intervention period would be necessary to evaluate the persistence of strength gains.

- Dietary control: participants' dietary patterns were not strictly controlled or monitored.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NS | Nutritional supplement |

| NSU | Nutritional supplement user |

| NNSU | Non-nutritional supplements user |

| LcS | L-carnitine supplement |

| LcSU | L-carnitine supplement user |

| PS | Protein supplement |

| PSU | Protein supplement user |

| CS | Carnitine supplement |

| CSU | Creatine supplement user |

| PCLcS | Combination of protein, creatine, and L-carnitine supplement |

| PCLcSU | Combination of protein, creatine, and L-carnitine supplement user. |

References

- Yadav, M. Diet, Sleep and Exercise: The Keystones of Healthy Lifestyle for Medical Students. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2022, 60, 841–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, S.; Cunha, M.; Costa, J.G.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C. Analysis of Food Supplements and Sports Foods Consumption Patterns among a Sample of Gym-Goers in Portugal. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2024, 21, 2388077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, F.W.; Roberts, C.K.; Laye, M.J. Lack of Exercise Is a Major Cause of Chronic Diseases. Compr Physiol 2012, 2, 1143–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tcymbal, A.; Gelius, P.; Abu-Omar, K.; Foster, C.; Whiting, S.; Mendes, R.; Titze, S.; Dorner, T.E.; Halbwachs, C.; Duclos, M.; et al. Development of National Physical Activity Recommendations in 18 EU Member States: A Comparison of Methodologies and the Use of Evidence. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e041710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J. An Overview of Current Physical Activity Recommendations in Primary Care. Korean J Fam Med 2019, 40, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, H. Antiaging Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Systemic Arteries. Hypertension 2019, 74, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korthuis, R.J. Skeletal Muscle Circulation; Integrated Systems Physiology: from Molecule to Function to Disease; Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences: San Rafael (CA), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor, G.; Chauhan, P.; Singh, G.; Malhotra, N.; Chahal, A. Physical Activity for Health and Fitness: Past, Present and Future. J Lifestyle Med 2022, 12, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Role of Nutrition in Performance Enhancement and Postexercise Recovery - PubMed Available online:. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26316828/ (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Davies, R.W.; Carson, B.P.; Jakeman, P.M. The Effect of Whey Protein Supplementation on the Temporal Recovery of Muscle Function Following Resistance Training: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millard-Stafford, M.; Snow, T.K.; Jones, M.L.; Suh, H. The Beverage Hydration Index: Influence of Electrolytes, Carbohydrate and Protein. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garthe, I.; Maughan, R.J. Athletes and Supplements: Prevalence and Perspectives. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018, 28, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Dawson Hughes, B.; Scott, D.; Sanders, K.M.; Rizzoli, R. Nutritional Strategies for Maintaining Muscle Mass and Strength from Middle Age to Later Life: A Narrative Review. Maturitas 2020, 132, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wax, B.; Kerksick, C.M.; Jagim, A.R.; Mayo, J.J.; Lyons, B.C.; Kreider, R.B. Creatine for Exercise and Sports Performance, with Recovery Considerations for Healthy Populations. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Nazhand, A.; Souto, S.B.; Silva, A.M.; Severino, P.; Souto, E.B.; Santini, A. The Nutraceutical Value of Carnitine and Its Use in Dietary Supplements. Molecules 2020, 25, 2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djaoudene, O.; Romano, A.; Bradai, Y.D.; Zebiri, F.; Ouchene, A.; Yousfi, Y.; Amrane-Abider, M.; Sahraoui-Remini, Y.; Madani, K. A Global Overview of Dietary Supplements: Regulation, Market Trends, Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic, and Health Effects. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branca, F.; Nikogosian, H.; Lobstein, T. The Challenge of Obesity in the WHO European Region and the Strategies for Response; World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 2007; ISBN 978-92-890-1408-3.

- Vargas-Molina, S.; Petro, J.L.; Romance, R.; Kreider, R.B.; Schoenfeld, B.J.; Bonilla, D.A.; Benítez-Porres, J. Effects of a Ketogenic Diet on Body Composition and Strength in Trained Women. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2020, 17, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proteina Din Zer Izolat, Weider, Isolate Whey 100 CFM, 908g – Gym-Stack. Available online: https://gym-stack.ro/products/proteina-din-zer-izolat-weider-isolate-whey-100-cfm-908g?variant=47238628311363&country=RO¤cy=RON&utm_medium=product_sync&utm_source=google&utm_content=sag_organic&utm_campaign=sag_organic&gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAg8S7BhATEiwAO2-R6tpHnvHQbp15CKcyDRtmG5Y3B-U_fWB4RbDAOTJj8-z5VHzzPikwTBoCjxQQAvD_BwE# (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- 100% Creatine Monohydrate (300 gr.) - Scitec Nutrition. Available online: https://scitec.ro/100-creatine-monohidrate/scitec-nutrition-100-creatine-monohydrate-300-gr-q2164 (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Cutie 20 Shoturi Nutrend L-Carnitină 3000mg 60ml. Available online: https://highenergy.ro/carnitina/cutie-20-shoturi-nutrend-l-carnitina-3000mg-60ml.html?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiAg8S7BhATEiwAO2-R6iF24Sg40F0GDTsu8tulyKjwDksGtOKfqQSUFkQY1ZXWcya1KCQGMxoCdsEQAvD_BwE (accessed on 16 February 2025).

- Moroșan, E.; Popovici, V.; Popescu, I.A.; Daraban, A.; Karampelas, O.; Matac, L.M.; Licu, M.; Rusu, A.; Chirigiu, L.-M.-E.; Opriţescu, S.; et al. Perception, Trust, and Motivation in Consumer Behavior for Organic Food Acquisition: An Exploratory Study. Foods 2025, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streba, L.; Popovici, V.; Mihai, A.; Mititelu, M.; Lupu, C.E.; Matei, M.; Vladu, I.M.; Iovănescu, M.L.; Cioboată, R.; Călărașu, C.; et al. Integrative Approach to Risk Factors in Simple Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases of the Lung or Associated with Metabolic Syndrome—Analysis and Prediction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Popovici, V.; Neacșu, S.M.; Musuc, A.M.; Busnatu, Ștefan S. ; Oprea, E.; Boroghină, S.C.; Mihai, A.; Streba, C.T.; Lupuliasa, D.; et al. Assessment of Dietary and Lifestyle Quality among the Romanian Population in the Post-Pandemic Period. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goston, J.L.; Correia, M.I.T.D. Intake of Nutritional Supplements among People Exercising in Gyms and Influencing Factors. Nutrition 2010, 26, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.; Cunha, M.; Costa, J.G.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C. Analysis of Food Supplements and Sports Foods Consumption Patterns among a Sample of Gym-Goers in Portugal. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 21. [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R.; Kerksick, C.M.; Campbell, B.I.; Cribb, P.J.; Wells, S.D.; Skwiat, T.M.; Purpura, M.; Ziegenfuss, T.N.; Ferrando, A.A.; Arent, S.M.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Protein and Exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2017, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, S.; Bosshard, J.V.; Häring, D.; Morgan, G. High Prevalence of Supplement Intake with a Concomitant Low Information Quality among Swiss Fitness Center Users. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, L.J.; Gizis, F.; Shorter, B. Prevalent Use of Dietary Supplements among People Who Exercise at a Commercial Gym. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2004, 14, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlic, H.; Lohninger, A. Supplementation of L-Carnitine in Athletes: Does It Make Sense? Nutrition 2004, 20, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzilli, M.; Macaluso, F.; Zambelli, S.; Picerno, P.; Iuliano, E. The Use of Dietary Supplements in Fitness Practitioners: A Cross-Sectional Observation Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, K.; Getzin, A. Nutrition and Supplement Update for the Endurance Athlete: Review and Recommendations. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Age-Performance Relationship in the General Population and Strategies to Delay Age Related Decline in Performance - PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31827790/ (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Mitchell, W.K.; Williams, J.; Atherton, P.; Larvin, M.; Lund, J.; Narici, M. Sarcopenia, Dynapenia, and the Impact of Advancing Age on Human Skeletal Muscle Size and Strength; a Quantitative Review. Front Physiol 2012, 3, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talenezhad, N.; Mohammadi, M.; Ramezani-Jolfaie, N.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H.; Salehi-Abargouei, A. Effects of L-Carnitine Supplementation on Weight Loss and Body Composition: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 37 Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials with Dose-Response Analysis. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2020, 37, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slimi, O.; Muscella, A.; Marsigliante, S.; Bahloul, M.; Badicu, G.; Alghannam, A.F.; Yagin, F.H. Optimizing Athletic Engagement and Performance of Obese Students: An Adaptive Approach through Basketball in Physical Education. Front Sports Act Living 2025, 6, 1448784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nutritional supplements type |

Trade name |

Pharmaceutical form and mode of administration |

Product details per one dose |

Amount administrated once | Number of daily administrations |

Time of administration |

| Whey Protein [19] |

Isolate Whey 100 CFM (Weider) |

Powder 1 cup dissolved in 200 milliliters of water or milk |

- 100% CFM whey protein isolate - Rich in BCAA (brain-chain-amino-acids) content - Low fat |

30 grams powder (1 cup)/25 grams protein |

2 doses (2 cups) | For men:1 cup in the morning and 1 cup after trainingFor women: Only 1 cup after training |

| Creatine Monohydrate [20] |

100% creatine monohydrate (SCITEC NUTRITION) |

Powder ½ cup dissolved in 300 milliliters of water | - 3,4 g of creatine per serving (1/2 cup) - vegan |

6.8 grams (1 cup) |

1 dose (1 cup) | 30 minutes before training |

| L-Carnitine [21] |

Carnitine 3000 shot (NUTREND) |

Liquid, a shot of 60 milliliters | - 3000 mg L-carnitine (CARNIPURE®) - Green tea extract (50% polyphenols) - Chromium - Does not contain sugar |

3000 milligrams (1 shot) |

1 dose (1 shot) | 30 minutes before training |

| Parameter | Total | F | M | p-value | |||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| total | 218.00 | 100.00 | 90.00 | 41.28 | 128.00 | 58.72 | <0.05 |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18-29 | 115.00 | 52.75 | 41.00 | 46.51 | 74.00 | 57.81 | <0.05 |

| 30-39 | 50.00 | 22.94 | 23.00 | 25.56 | 27.00 | 21.09 | >0.05 |

| 40-49 | 47.00 | 21.54 | 23.00 | 25.56 | 24.00 | 18.75 | <0.05 |

| >50 | 6.00 | 2.75 | 3.00 | 3.33 | 3.00 | 2.34 | >0.05 |

| Weight type | |||||||

| Normal-weight | 112.00 | 51.38 | 65.00 | 75.58 | 47.00 | 35.61 | <0.05 |

| Obese | 2.00 | 0.92 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.52 | |

| Overweight | 98.00 | 44.95 | 16.00 | 18.60 | 82.00 | 62.12 | |

| Underweight | 6.00 | 2.75 | 5.00 | 5.81 | 1.00 | 0.76 | |

| NS consumption | |||||||

| No | 53.00 | 24.31 | 31.00 | 36.05 | 22.00 | 16.67 | <0.05 |

| Yes | 165.00 | 75.69 | 55.00 | 63.95 | 110.00 | 83.33 | |

| Parameter | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| 18-29 years | 30-39 years | 40-49 years | >50 years | |||||

| Normal weight | 61.00 | 53.04 | 24.00 | 48.00 | 25.00 | 53.19 | 2.00 | 33.33 |

| Obese | 2.00 | 1.74 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Overweight | 48.00 | 41.74 | 24.00 | 48.00 | 22.00 | 46.81 | 4.00 | 66.67 |

| Underweight | 4.00 | 3.48 | 2.00 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Normal weight | Obese | Overweight | Underweight | |||||

| CSU | 17.00 | 15.18 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 21.00 | 21.43 | 1.00 | 16.67 |

| LcSU | 17.00 | 15.18 | 1.00 | 50.00 | 18.00 | 18.37 | 1.00 | 16.67 |

| NNSU | 30.00 | 26.79 | 1.00 | 50.00 | 20.00 | 20.41 | 2.00 | 33.33 |

| PCLcSU | 25.00 | 22.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 22.00 | 22.45 | 1.00 | 16.67 |

| PSU | 23.00 | 20.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 17.00 | 17.35 | 1.00 | 16.67 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).