1. Introduction

Both nutrition and physical activity are fundamental pillars of good health, offering many benefits that impact nearly every aspect of our well-being. They work synergistically to promote a healthier and longer life. Due to environmental concerns raised by the food industry, the World Health Organization (WHO) supports sustainable diets, defined as dietary patterns that underline all dimensions of individuals' health and well-being [

1,

2]. Regular physical activity, encompassing any body movement that expends energy, offers a multitude of physical and mental health advantages: improves cardiovascular health, helps manage weight, builds and maintains strong muscles and bones, increases energy levels, improves mood, and diminishes stress, enhances cognitive function, facilitates recovery after various diseases, reduces the risk of chronic ones and ameliorates patient condition in various chronic illnesses [

3].

Numerous people embrace a lifestyle that incorporates a balanced diet and regular exercise as a key to a healthier life. Most use gyms and fitness facilities for general health, weight loss, and fitness improvement, and are known as recreational gym-goers [

4]. They incorporate gym attendance and exercise into their lives for individual benefits and enjoyment without the pressures and demands of professional athletes [

5]. Currently, recreationists excessively focus on improving fitness and achieving aesthetic goals, such as building muscle or losing fat, using various nutritional supplements (NSs). Although the use of NSs by professional athletes and their benefits have been extensively studied, the literature on recreational athletes is limited [

6].

1.1. Literature review

1.1.1. Protein and Amino Acid Supplementation—Benefits and Daily Doses

Protein supplements, particularly whey protein (WP), are among the most popular due to their role in muscle synthesis and recovery [

7]. The Institute of Medicine's recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 g/kg/day for the entire adult population [

8], while the Acceptable Macronutrient Distribution Range (AMDR) indicates a daily protein intake of 1.05–3.67 grams per kilogram of body weight for adults aged 18 years and older [

9]. The International Society of Sports Nutrition showed that for most people who exercise, an overall protein intake in the range of 1.4-2.0 g protein/kg body weight/day (g/kg/d) is adequate for gaining and maintaining muscle mass through a positive muscle protein balance. More protein (2.3–3.1 g/kg/d) could be required for resistance-trained subjects to optimize lean body mass retention during hypocaloric periods. Higher protein intakes (>3.0 g/kg/d) may improve body composition in resistance-trained individuals (encourage loss of fat mass) [

10].

Whey protein has significantly impacted nutritional supplements for athletes, as it contains around 50% of essential amino acids (EAA) and approximately 26% of branched-chain amino acids (BCAA). The amino acid composition of WP exhibits a similar pattern to that of human skeletal muscle, allowing for faster absorption compared to other protein sources [

11]. It can stimulate skeletal muscles, reduce fatigue, enhance muscle protein synthesis (MPS), and slightly inhibit muscle protein breakdown (MPB) [

12]. Recreational exercisers widely practice resistance training (RT) combined with WP supplementation to increase the muscle mass and strength that RT induces [

13]. A daily dose of 20 to 25 g of WP yields the intended advantages. However, exceeding 40 g may cause adverse effects [

14].

Creatine is a well-documented ergogenic aid that facilitates ATP production by enhancing muscle strength, lean body mass, and recovery [

15]. It is a guanidine compound with both exogenous and endogenous sources, synthesized in the kidneys, liver, and pancreas from three amino acids: glycine, methionine, and arginine [

16,

17]. Creatine monohydrate (CM) supplementation has been consistently reported in the literature to increase phosphagen levels in muscle, improve performance during repetitive high-intensity exercise, and promote significant training adaptations [

18]. It is a stable form of Creatine that is not significantly degraded during the digestive process and is either taken up by muscle or eliminated in the urine. Despite its widespread use worldwide, no clinically significant adverse effects have been reported from CM supplementation; short- and long-term supplementation is safe and well-tolerated in healthy individuals and several patient populations. The regulatory status of CM is not well established; currently, it is the only form of creatine officially approved in key markets, including the USA, Canada, the European Union, and South Korea [

18].

Research has shown the effects of creatine supplementation, including injury prevention and rehabilitation, enhanced post-exercise recovery, increases in serum testosterone concentration, and reduction in cortisol level [

19], as well as potential neurological benefits relevant to sports [

20,

21]. Supplementation protocols include an initial loading phase (0.3 g/kg/day) for 5-6 days, followed by a maintenance dose that varies in different studies: 0.03 g/kg/day [

22], 0.07 g/kg/day [

23], or 0.1g/kg/day [

24]. Previous studies regarding creatine supplementation's effects on RT performance were conducted both ways, with and without a loading protocol [

25,

26]. Galvan et al. conducted a trial involving 13 healthy and physically active adults divided into four groups, each supplemented with a different dose of Creatine (1.5 g, 3 g, and 5 g/day), aiming to assess the dose-dependent effects on safety and exercise performance rates. The authors concluded that a dose of up to 3 g/day is safe and effective regarding changes in strength and body composition [

27]. A recent study examined the effects of whey protein and creatine supplementation compared to WP consumption alone on body composition and performance variables in 17 resistance-trained young women [

28]. After 8 weeks of training, Wilborn et al. observed that all performances increased, but no significant differences were recorded between WP and WP+CM supplementation [

28]. Similar results were reported by Collins et al. in the RT of elderly individuals with frailty [

29].

L-carnitine, another widely used supplement, is valued for facilitating the metabolism of fatty acids and energy production within mitochondria [

30]. Increasing L-carnitine intake through supplementation can enhance fat oxidation, significantly reducing body fat reserves [

31]. Several studies reported that LcS increases exercise performance, improves recovery, and reduces oxidative stress [

32,

33]. Although naturally present in animal-based foods, its supplementation is often necessary for individuals with higher metabolic demands or specific treatments and dietary restrictions [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. L-carnitine tartrate supplementation has a beneficial effect on markers of post-exercise metabolic stress and muscle damage. Spiering et al. demonstrated that 1-2 g L-carnitine effectively mitigated various markers of metabolic stress and muscle soreness in athletes [

42] while 3-4 g taken before physical exercise, prolonged exhaustion [

43]. Evans et al. reported the benefits of L-carnitine combined with creatine and leucine on functional muscle strength in healthy older adults [

44].

1.1.2. Protein and Amino Acid Supplements: Potential Side Effects. Nutrivigilance

Protein supplements are safe for most people when recommended, but they can cause side effects, especially when overused or if there are underlying health conditions [

45]. The well-known side effects are digestive issues (abdominal pain, gas, diarrhea), kidney strains [

46,

47,

48], liver damage (when the liver is previously affected) [

49,

50], allergic reactions [

51], nutrient imbalance, heavy metal contamination [

52], and weight gain. Several less common side effects could be hormonal imbalance due to Soy Protein, acne [

53,

54], and skin issues due to WP and bone demineralization [

55].

Creatine supplementation is safe for healthy individuals at recommended dosages [

56]. However, like any supplement, it may cause side effects in some users. Kidney and liver damage are potential side effects supported by scientific literature [

57,

58,

59,

60].

L-carnitine, in higher doses than 3 g/daily and prolonged treatment, can induce liver and kidney damage [

61], digestive discomfort, body fish odor, rash, seizure, and high blood pressure [

62].

For safeguarding consumer health by identifying potential risks associated with nutritional supplements, nutrivigilance is the science and practice of monitoring, detecting, assessing, and preventing adverse effects related to consuming food products, particularly dietary supplements, fortified foods, novel foods, and foods for a specific population [

63]. Nutrivigilance plays a considerable role in ensuring the post-market safety of nutritional supplements [

64]. By systematically collecting and analyzing data on adverse effects, authorities can identify potential risks, inform regulatory decisions, and protect public health [

65].

While some countries have established national nutrivigilance systems [

66], there is a lack of harmonization across the European Union [

67]. This disparity leads to inconsistencies in monitoring and managing the safety of food supplements and related products [

68]. Experts emphasize the necessity for a coordinated European nutrivigilance system to facilitate data sharing, risk assessment, and regulatory actions, thereby enhancing consumer protection across member states [

69]. Establishing and harmonizing nutrivigilance systems are essential to achieving comprehensive consumer safety in food supplements and related products [

70].

1.1.3. Protein and Amino-Acid Supplements Consumption in Recreational Gym Goers

The continuously increasing prevalence of various NS consumption without a healthcare professional recommendation can be explained by the widespread belief that their regular intake could improve consumer health [

71,

72]. Recreational gym-goers use NSs more than professional athletes [

73]; unexpectantly, a recent study reported that, in Brasilia, most consumers of sports dietary supplements are physically inactive [

74].

While individual preferences and objectives vary, some supplements are more popular. Athletes consume the most vitamins (75.3%), recreational gym goers prefer protein alone (30.8%) or in combination with creatine (12.2%) [

75]. Thomas et al. observed that protein supplement consumption is linked to time spent exercising and high-protein-content foods [

76]. Several authors suggest that athletes need extra proteins in their diet as food or as supplements, but regular gym-goers do not need these extra supplements [

77]. However, physicians and nutritionists have been poorly consulted [

78].

Then, recreational athletes' protein consumption is based on their own beliefs [

78,

79,

80]; creatine and protein are in the top 5 of the most used NSs [

81]. Frequently consumed by gym-goers are protein powders (59.17%), followed by creatine (41.28%), and L-carnitine (5.05%) [

82]. Most recreationists prefer protein associated with creatine and amino acids (48.8%) or protein and creatine alone (6.4%) [

78]. Peeling et al. included creatine in the group of established performance supplements. At the same time, L-carnitine was considered an equivocal one, with less clear evidence for its potential to enhance athletic performance [

83]. Numerous questionnaire-based studies aimed to investigate protein and amino acid supplementation in recreational gym goers worldwide and the associated factors. Most of them analyzed the most-used supplements from various categories. They correlated their use with some aspects (age, sex, diet, bad habits, body weight, education, income, training type, frequency, scope, etc.) [

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98].

A few studies explored the increasing trend of NS consumption without medical advice in Romanian athletes. Ionescu et al. described a new model of analytical and prospective tools that explore nutritional supplement consumption and their positive or harmful effects [

99]. Another research team used an online questionnaire to provide original information on dietary supplement use, type, effects, and source of purchase among healthy residents in Târgu Mureș, Romania [

100]. Another study highlights the necessity of introducing nutrivigilance as a habitual practice and activity of all authorities and actors in the Romanian dietary supplements market [

101].

1.2. Hypotheses

The literature review led to the following hypotheses:

- ○

Recreational gym-goers commonly use protein and amino acid supplements, alone or in combination [

78,

94,

102];

- ○

Most of them are men who are young and highly educated [

75,

79,

80,

103,

104];

- ○

Various socio-demographic and training factors influence gym-goers' protein and amino acid supplements consumption [

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110];

- ○

Protein and amino acid supplements may have side effects claimed by the affected consumers [

62,

111,

112].

1.3. The Aim of the Present Study

In this context, the present study investigates the consumption of protein, creatine, and L-carnitine, alone and in combination, in recreational gym-goers from Northeastern Romania. It aims to analyze the reasons for using each nutritional supplement and the significant influencing factors. Based on the above-mentioned recent studies, a similar complex and extensive analysis of protein and amino acid supplementation in a heterogeneous group of Romanian recreational athletes has not yet been performed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study followed the Declaration of Helsinki regulations [

113]. The protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Oradea, Romania, No. 21/25.02.2021, and the Gym Committee No 7/3.10.2022.

This cross-sectional study was conducted as a face-to-face interview in 2 popular gymnasiums in Oradea, Romania, from 15 January to 15 December 2024. Participants are regular gym-goers in these 2 gyms, males and females aged 18-60 years old, Romanian language speakers, and residents of the Oradea Metropolitan Area [

114]. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are displayed in

Table 1.

Two qualified coaches performed a rigorous check and selection of potential participants at both gym locations. Only 165 fulfilled the inclusion criteria, 55 females and 110 males. They revealed their preference for protein, creatine, and L-carnitine supplement consumption; they had regular training sessions at least twice a week in one of the gym locations. All participants were differentiated by supplement type: 42/165 were protein supplement users (PSU), 38/35 - creatine supplement users (CSU), 37/165 - L-carnitine supplement users (37/165), and 48/165 preferred to consume them in combination - protein, creatine, and L-carnitine supplement users (PCLcSUs, 48/165).

2.2. Method

Participants received brief instructions about the purpose and nature of the present research. A written informed consent was obtained from each participant who voluntarily participated in the present study. The data collection tool was a face-to-face interview based on a complex questionnaire adapted from previous works [

6,

82,

116,

117]. The participants were assured that the researchers would maintain their privacy and keep the data collected private. Measurements of body weight and height were made for all individuals before the interview, and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated under WHO guidelines using the Quetelet equation: body weight (kg)/height2 (m

2) [

118].

The questionnaire's first section focuses on demographic and socio-economic information. Age, gender, education level, occupation, and monthly income were included in the socio-demographic data-related inquiries. The participants were asked about their type and degree of activity at work, classifying them as completely sedentary in office jobs, physically active jobs, and their combination.

The second section of the questionnaire investigates the participants' lifestyles and healthcare levels (body weight, unhealthy habits, diet type, daily calorie consumption, daily protein consumption, and the frequency of daily meals.

The third section contains data about the gym workout routines. It includes detailed information about how long it has been since the participants started working out at the gym, how many days a week they work out there, how many hours/minutes they spend in the gym, what kinds of exercises they do there—such as cardio exercises, strength training, and a mix of both exercises—and the scope of gym training.

The fourth section of the questionnaire investigates the participants' awareness of NS, motivation for using them, administration details, benefits, and possible side effects observed after using them in conjunction with gym practice.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Reliability Analysis Internal Model of XLSTAT Premium v.2024.4.2.1426 by Lumivero (Denver, CO, USA) investigated the questionnaire, checking the intercorrelation between all questions. The Cronbach's alpha index and Guttman L1–L6 coefficients were calculated [

119].

Descriptive statistics were computed to summarize and analyze the dataset's central tendency, dispersion, and distribution, providing essential insights into the study variables. This analysis was conducted using XLSTAT Premium 2024 v. 2024.4.2.1426 and followed methodologies outlined in previous research studies [

120,

121]. Data are expressed as frequency (number) and relative frequency (percentage).

Furthermore, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed using Pearson correlation to detect the relationships among variables [

122]. The modifiable factors were NSs consumption, while the influential ones were all aspects investigated in the face-to-face questionnaire. The statistical significance was set at

p-value <0.05, indicating that results below this threshold were considered statistically significant, aligning with standard health and nutrition research practices.

All used statistical tools ensured robust and reliable data analysis, facilitating accurate interpretation of the relationships between variables.

3. Results

3.1. Reliability Analysis

The Cronbach's alpha index value was 0.947, and the Guttman L1–L6 coefficients were 0.910–1.000. The correlation matrix, covariance matrix, and high coefficients reveal that all questions are significantly intercorrelated. The data obtained confirmed the questionnaire's substantial reliability and appreciable internal consistency, thus confirming its high quality.

3.2. Socio-demographic Data of Participants

The present study enrolled 165 recreational gym-goers who prefer various NSs. Of the participants, 33.33% (55/165) were women, and 66.67% (110/165) were men, p<0.05. Over 50% (87/165, 52.73%) are 18-30 years old, and 2.42% (4/165) are 50-60 years old, p<0.05. Similar percentages (23.64% and 21.21%) belong to the 30-40 and 41-50 age groups.

Most participants (135/165) have a substantial educational level: university studies (105/165, 63.64%) and master's/doctorate's (30/165, 18.18%), while only 18.18% (30/165) have a high school, p<0.05. Monthly income varies from <2000 RON (3/165, 1.82%) to >6000 RON (43/165, 26.06%), p<0.05. Most respondents have 2000 – 4000 RON (75/165, 45.45%), followed by those with 4001 – 6000 RON (44/165, 26.67%), p<0.05 (

Table 2).

The daily working (DW) regimen involves > 8 h for most of them (91/165, 55.15%), following, in decreasing order, those with 4 – 8 h (69/165, 41.82%) and 1 – 4 hours (5/165, 3.03%), p<0.05. Their daily work consists of physical activity (44/165, 26.67%) and office (54/165, 32.73%); 40.61% of participants (67/165) have combined work (physical activity and office), p<0.05 (

Table 2).

3.3. Lifestyle Patterns and Self-Care Awareness

The following questions investigated the participants' lifestyles: unhealthy habits, diet type, daily meal frequency and nutritional content, body weight type, and illness history. All data are displayed in

Table 3.

Most gym-goer participants are non-smokers (116/165, 70.3%), while only 29.70% (p<0.05) declared they are smokers (daily and occasionally, in similar percentages: 15.15% vs. 14.55%, p>0.05). Only 19.39% of respondents stated they are not alcohol consumers (32/165), while most of them consume alcohol (80.61%, p<0.05). Over 60% of respondents (107/165, 64.85%) have a balanced diet (

Table 2). Extreme diets (hyperprotein, vegetarian, and low-carb) have significantly lower incidences (19.39% vs. 9.7% vs. 6.06%), p<0.05. Most respondents have 3 meals/day (49.49%, 81/165) or 3 meals + 2 snacks (31.52%, 52/165), p<0.05. Several gym-goers have 2 meals/daily (18/165, 10.91%), while 8.48% (14/165) prefer intermittent fasting (

Table 2). Daily calorie (DC) rate ranges between 1000 – 1500 Cal and > 3500 Cal. Over 50% (88/175, 53.33%) consume 1501 – 2500 Cal/day (

Table 2). Around 5/165 (3.03%) participants did not know their DC consumption; most were men (4/165) vs. women (1/154), p<0.05.

Daily protein (DP) intake varies between < 50 g (1/165, 0.61%) and > 250g (7/165, 4.24%), p<0.05. Most respondents consume 50-150 g of protein daily (79/165, 47.88%) and have a normal weight (83/165, 50.30%) or are overweight (76/165, 46.06%). Substantial differences were recorded between women and men in the overweight category (14.55% vs. 61.82%, p<0.05). Only 2 participants (men) are obese (2/165, 1.21%), and only 4 are underweight (3 females and 1 male).

Principal Component Analysis of baseline data shows that normal weight (NW) moderately correlates with age groups 18-30 and 31-40 (r = 0.689, r = 0.760, p>0.05), DW > 8 h (r = 0.740, p>0.05), and physical work (r = 0.749, p>0.05). Both age groups are substantially correlated with DW>8 h and physical work (r = 0.996-0.999, p<0.05). On the other hand, OW is strongly associated with the >50 age group and moderately correlates with 41-50 (r = 0.762, p>0.05) and DW = 1-4 h and 4-8 h (r = 0.778, 0.662, p>0.05). Both DW periods highly correlate with 41-50 (r =0.999—0.986, p<0.05) and >50 (r = 0.943—0.873, p>0.05) age groups. A remarkable correlation exists between OW and DC >3500 (r = 0.999, p<0.05) and a moderate one between OW and DC=1000—1500, DC=3001—3500, and intermittent fasting (r = 0.770 - 0.667, p>0.05). Contrariwise, NW correlates well with DC = 2501-3000 (r = 0.816, p>0.05) and is moderately associated with DC = 2501-3000 and DC = 2001-2500 (r = 0.762, r = 0.703, p>0.05) and with all daily meal frequencies (r = 0.697 – 0.623, p>0.05).

Normal weight is substantially associated with females (r = 0.987, p<0.05), while OW displays a strong correlation with DP < 50 g (r = 0.999, p<0.05). NW has a good correlation with high school (r = 0.863, p>0.05), while OW correlates with males (r = 0.837, p>0.05). NW moderately correlates with DP = 151–200 g, DP = 201- 250 g, and master/doc (r = 0.789 – 0.709, p>0.05) while OW with DP = 101- 150 g, DP>250 g, and university (r = 0.728 – 0.633, p>0.05).

3.4. Nutritional Supplements and Training Data

Of 165 gym-goers, 38 (23.03%) were CSUs, 37 (22.42%) were LcSUs, 42 (25.45%) were PSUs, and 48 (29.09%) were PCLcSUs (

Table 4).

The gym's regular practice varies between < 1 month (47/165) and > 1 year (89/165), while the gym's weekly frequency is < 3 (57/165) times and ≥ 5 times (38/165), p<0.05; the training time ranges from < 1 hour (36/165) and > 2 hours (3/165), p<0.05 (

Table 3).

Three types of exercises are available: Cardio (15/165), Force (89/165), and Cardio+Force (61/165), and the main reasons for training are muscle mass growth (MMG, 82/165), Muscle mass tonus (55/165), weight loss (19/165), and competition (9/165), p<0.05 (

Table 4).

Numerous NSU participants have been practicing recreational gym for over one year: 18/38 CSUs, 18/27 LcSUs, 22/42 PCLcSUs, and 31/48 PSUs. A significant percentage of them went to the gym very recently, from less than 1 month: 41.57% of PCLcSUs, 31.58% of CSUs, and 29.73% of LcSUs (

Table 3).

Most PSUs go to the gym 3-4 times/weekly (26/42, 61.9%), followed by 18/38 CSUs (47.37%). The other 41.67% of PCLcSUs and 40.54% of LcSUs have less than 3 training sessions/week.

The gym training session duration is 1-2 hours for most participants (70.27 - 83.33%) vs. others: < 1h (20.83 – 29.73%, p<0.05) and > 2 hours (0 – 6.25%, p<0.05).

Creatine and L-carnitine are consumed in similar percentages for force training (65.79 and 62.16%, p>0.05), while PCLcS and PS are used in Cardio+Force and Force in the same measure (42.86 – 47.92%, p>0.05).

Muscle mass growth is the principal training scope for all NSUs (40.54 – 57.89%), followed by the muscular tonus (27.08 – 40.54%), p>0.05 (

Table 3). For weight loss, LcS and PS are used in equal measure (almost 16%), while PCLcS is also most consumed for competition (10.42%).

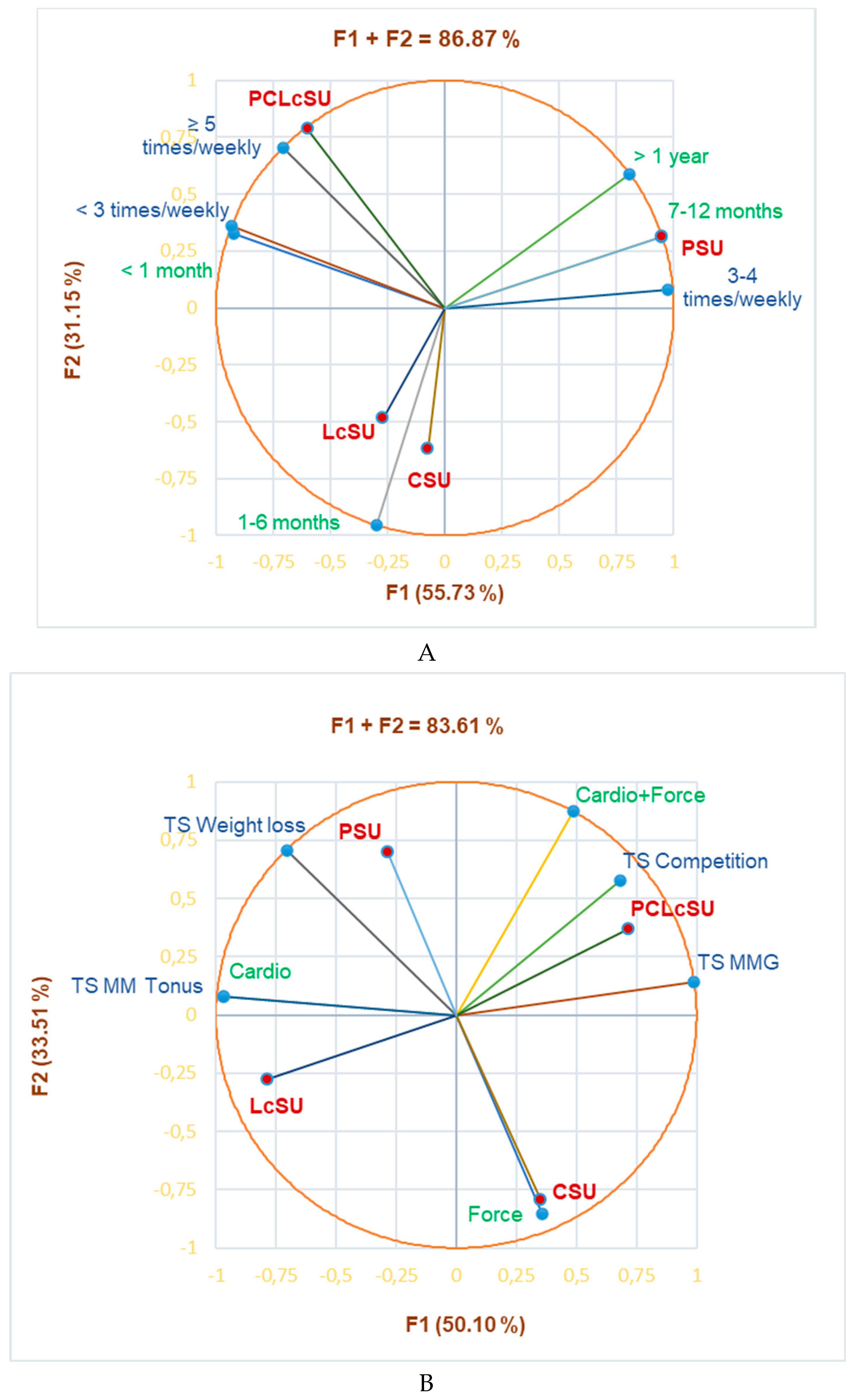

Principal Component Analysis supports our results (

Figure 1).

Figure 1A shows that PSUs substantially correlate with the Gym period 7-12 months and > 1 year (r = 0.999, r = 0.952, p<0.05), and Gym frequency 3-4 times/weekly (r = 0.923, p>0.05). PCLcSUs considerably correlate with ≥5 times/weekly (r = 0.968, p<0.05) and show a good correlation with a gym period < 1 month and frequency < 3 times/weekly (r = 0.840, r = 0.838, p>0.05). LcSUs and CSUs are moderately correlated with a gym period of 1-6 months (r = 0.577, p>0.05).

Figure 1B highlights the substantial correlation between PCLcSUs and Competition as a training scope (r = 0.968, p<0.05) and Cardio exercises and TS-MM tonus (r = 0.999, p<0.05). Cardio exercises and TS-MM tonus strongly correlate with LcSUs (r = 0.870, p>0.05), while Cardio+Force with TS Competition (r = 0.834, p>0.05). CSUs moderately correlate with Force exercises, PCLcSUs with Cardio+Force exercises and TS-MMG, while PSUs and Cardio exercises with TS-weight loss and Cardio+Force exercises with TS-MMG (r = 0.604—0.788, p>0.05).

3.4. Specific Aspects of Protein and Amino Acid Supplements Consumption

3.4.1. One-Only Supplement Consumers

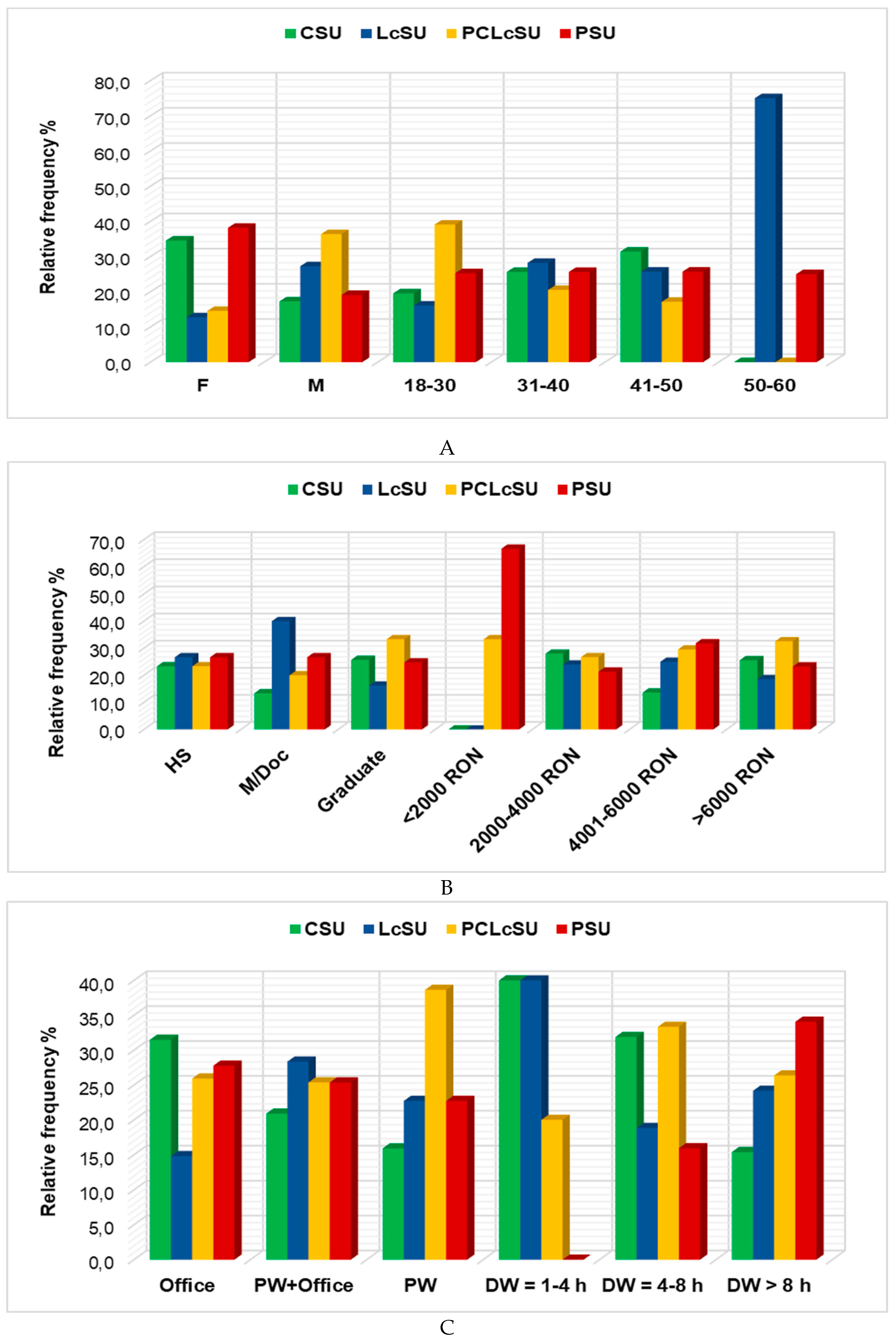

Table 4 registers our findings exclusively correlated with NS consumption (period, time, frequency, dose, main reason for consumption, and side effects) for one-only NS users (117 gym-goers).

Over 50% of CSUs consume it always (22/38), while other NSs are consumed in MMG time (18/37 LcSUs and 29/37 PSUs), p<0.05. Most CSUs (22/37) and LcSUs (18/38) consume those NSs from < 1 year, while PCUs (19/42) reported 1-3 years. CS and PS were mainly consumed daily (26/38 vs. 23/42,

Table 4), while LcS was principally consumed on training days (20/38). CSUs use 1-5 g (23/38) and 6-10 g (15/38), p<0.05. Most LcSUs (17/38) intake 2 g LcS, while 14/38 use 1g; only 6/38 use 6 g /daily. Mainly, PS doses were 40 g (19/42), 20 g (18/42), and 60 g (5/42). LcS is used exclusively for fat burning (37/37), PS for MMG (29/42), and weight loss (12/42), while CS is for MMG (18/38) and physical effort capacity (18/38), p<0.05.

Most NS users (77/117) declared no side effects (

Table 5). However, 40/117 participants declared adverse effects; 8/42 PSUs declared liver damage, 6/42 revealed muscle cramps, and 1/42 had kidney damage. In LcUs, 9/38 mentioned nausea, and 5/38 had stomach cramps. CSUs claimed liver damage (6/37) and weight gain (3/37), p<0.05 (

Table 5).

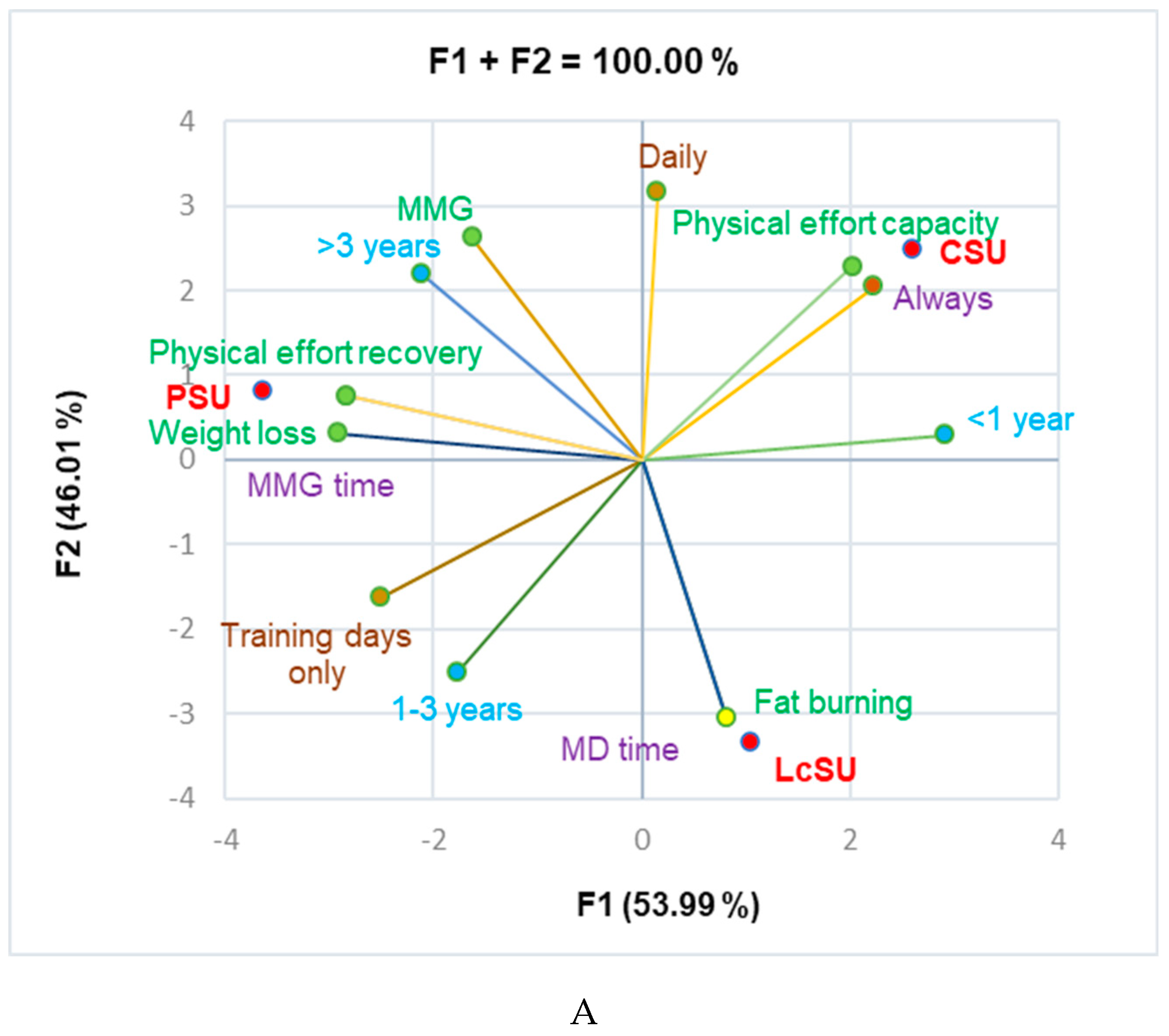

Principal Component Analysis supports data from

Table 4, evidencing the correlations between variable parameters (

Figure 2).

Figure 2A shows a significant correlation between CSUs and physical effort capacity (r = 0.999, p<0.05), PSUs and physical effort recovery, and weight loss (r = 0.999, p<0.05), and LcSUs and fat-burning and consumption in MD time (r = 0.999, p<0.05).

Figure 2B shows that diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps are substantially associated with LcS at 1-2 g/dose (r = 0.999, p<0.05). PS at 20, 40, 60 g/dose significantly correlates with muscle cramps and liver damage (r = 0.999, p<0.05), while CS at 1-5 g strongly correlates with weight gain (r = 0.999, p<0.05). CS also correlates with 6-10 g/ dose and kidney damage (r=0.918- 0.988, p>0.05).

3.4.2. Combination (PCLcS) Consumers

All 48 participants intake all 3 NSs daily to obtain maximal benefits (

Table 6).

They mainly consume PS always (28/48), LcS in MD time (36/48), and CS in MMG (36/48). They used all NSs for almost < 1 year (PS, 22/48; LcS, 18/48, and CS, 27/48, p<0.05). The CS and PS were used daily (35/48 and 25/48, p<0.05), while LcS was used on training days only (47/48) in almost the same doses mentioned by the one-only NSUs (recorded in

Table 4). PS and CS are primarily used for MMG (31/48 and 34/48) and LcS for fat burning (45/48). All NSs were also used for physical effort recovery (3/48 use PS and LcS, while 6/48 use CS), 14/48 intake PS for weight loss, and 8/48 have CS for physical effort capacity (p<0.05,

Table 6).

All PCLcSUs reported side effects of each component; muscle cramps and liver damage were evidenced by 15/48 after PS consumption, while 10/48 claimed kidney damage and weight gain caused by CS use (p<0.05). LcS administration's side effects were diarrhea, nausea, stomach cramps, and vomiting experienced by 23/48 gym-goers (p<0.05,

Table 6).

3.5. Protein and Amino Acid Supplements Consumption–Significant Correlations with Baseline Data

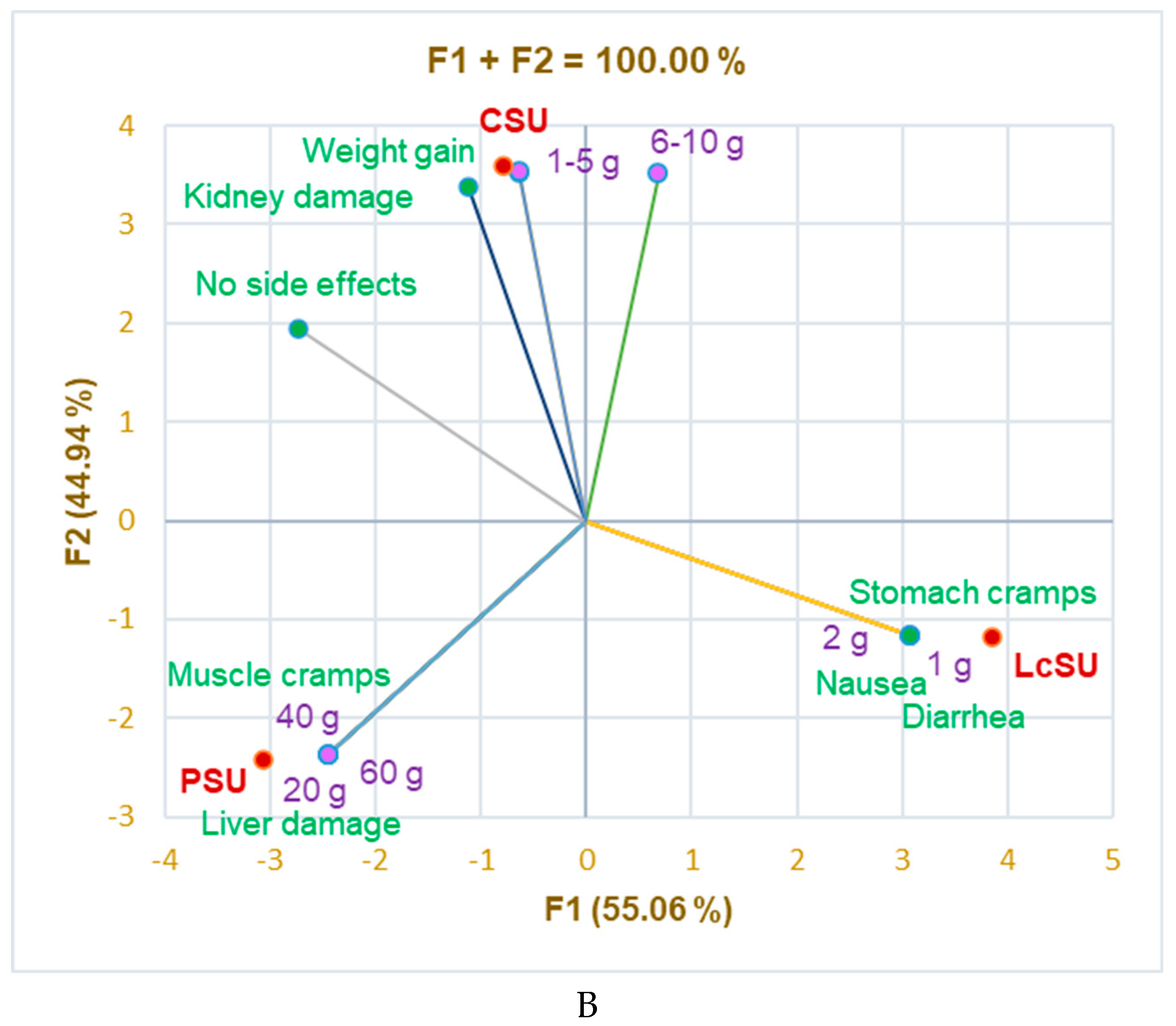

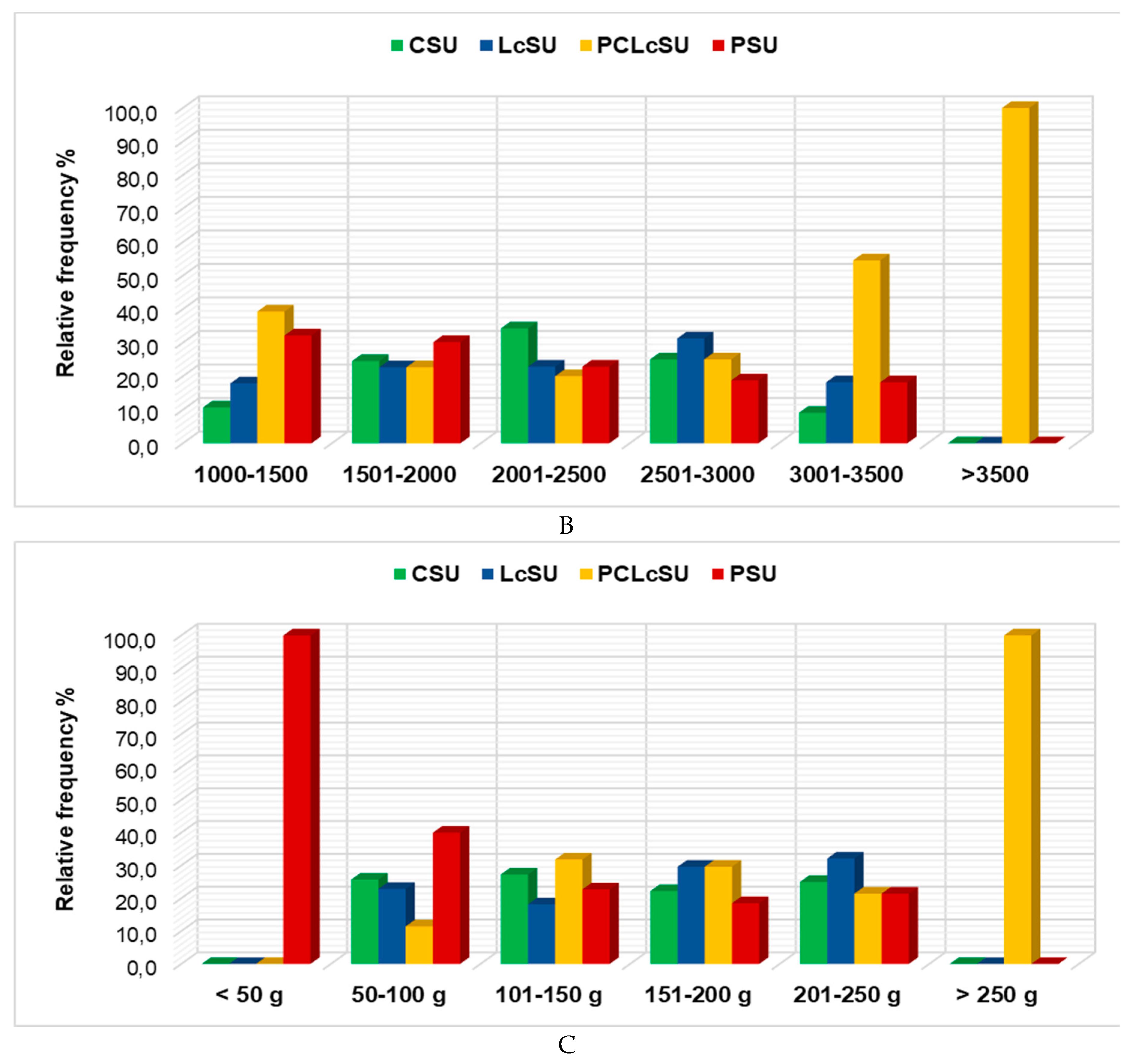

3.5.1. NS Consumption and Socio-Demographic Data

Protein and amino acid supplementation are influenced by socio-demographic factors (sex, age group, educational level, monthly income, daily working time, and work type (

Figure 3A-C). Females prefer PS and CS to PCLcS and LcS (38.2% and 34.5% vs. 14.5% and 12.7%, p<0.05,

Figure 3A). The most used NS by males are PCLcS (36.4%) and LcS (27.3%). Their preference for PS and CS is significantly diminished (19.1% and 17.3%, p<0.05,

Figure 3A). Recreational gym-goers aged 18-30 mostly prefer PCLcS (39.1%). The use of this combination significantly decreases with age progress (31-40 and 41-50: 20.5% and 17.1%, p<0.05); the NS combination is not used by recreational athletes aged 51-60 (

Figure 3A). The CSU's percentages increase proportionally to age 18-30 vs. 31-40 vs. 41-50 = 19.5 vs. 25.6 vs. 31.4, p<0.05; however, the 50-60 age group does not use CS (

Figure 3A). Protein consumption is similar in all age groups (25 – 25.7%), while L-carnitine use largely varies from 19.5% in the 18-29 age group to 75% in the 50-60 age group participants, p<0.05 (

Figure 3A).

The NS preferences of high school gym-goers and those with a monthly income = 2000 – 4000 RON are not significantly different, p>0.05 (

Figure 3B). The PCLcS, CS, and LcS consumption significantly differ in graduate and postgraduate participants: 33.3%, 25.7 %, and 16.2% vs. 20%, 13.3%, and 40%, p<0.05,

Figure 3B). The preference for PCLcS slightly increases with monthly income, from 2000-3000 RON to over 6000 RON, while LcS use is similar (p>0.05,

Figure 3B).

Creatine (p<0.05) and protein consumption (p>0.05) decrease with work type, from office to physical work. Protein consumption increases with DW hours, while creatine consumption diminishes with them (p<0.05,

Figure 3C).

Pearson Correlation supports our findings. The correlation coefficient (r) shows that CSU significantly correlates with office work, while LcSU shows a substantial association with master/doc (r = 0.992—0.997, p<0.05). PCLcSU highly correlates with males and university educational levels, DW = 4-8 h and > 8 h (r = 0.967—0.999, p<0.05). Moreover, PS consumption is strongly associated with office work (r = 0.992, p<0.05), while PCLcS is related to physical work (r = 0.988, p<0.05). CS consumption substantially correlates with the monthly income (MI) of 4000 - 6000 RON. PS and PCLcS are significantly associated with MI > 6000 RON (r = 0.970-0.996, p<0.05), while PCLcS also strongly correlates with MI < 2000 RON (r =0.974, p<0.05).

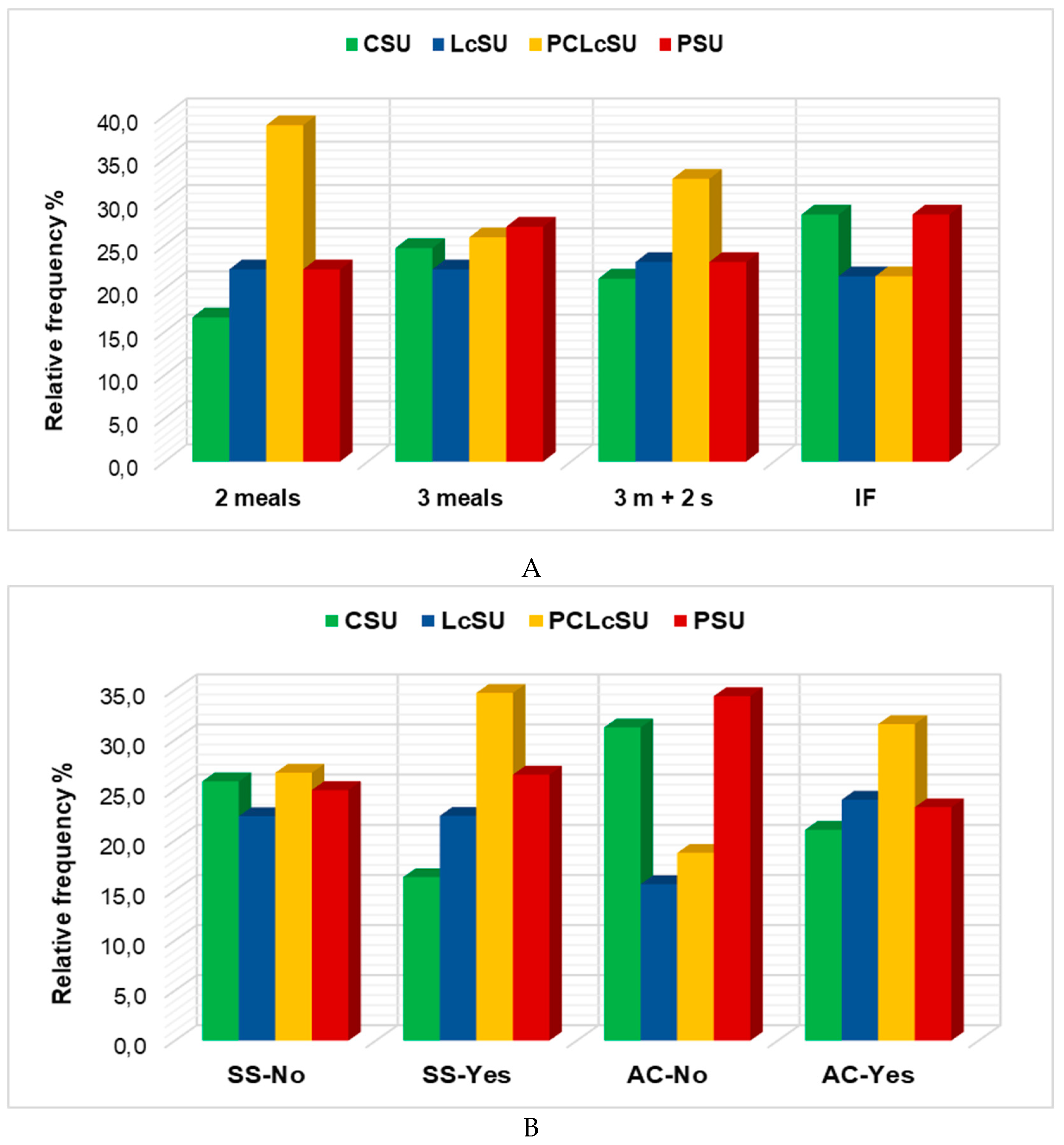

3.5.2. NS Consumption, Daily Meals Frequency, and Unhealthy Habits

PCLcS is consumed by gym-goers with 2 meals and those with 3 meals and 2 snacks, higher than another NS (p<0.05), while PS and CS are the leading choice of those with IF and 3 meals (p>0.05,

Figure 4A). No significant differences were recorded in LcS preferences (p>0.05,

Figure 4A).

No significant differences between no-smoker gym-goers and NS consumption (22.4 – 26.7%, p>0.05). PCLcS is mainly preferred by smokers (34.7%), while all others are less preferred (p<0.05,

Figure 4B). The same preferences are shown by gym-goers who consume alcohol; PCLcS is the first (p>0.05,

Figure 4B). Non-alcohol consumers most frequently choose protein and creatine (

Figure 4B).

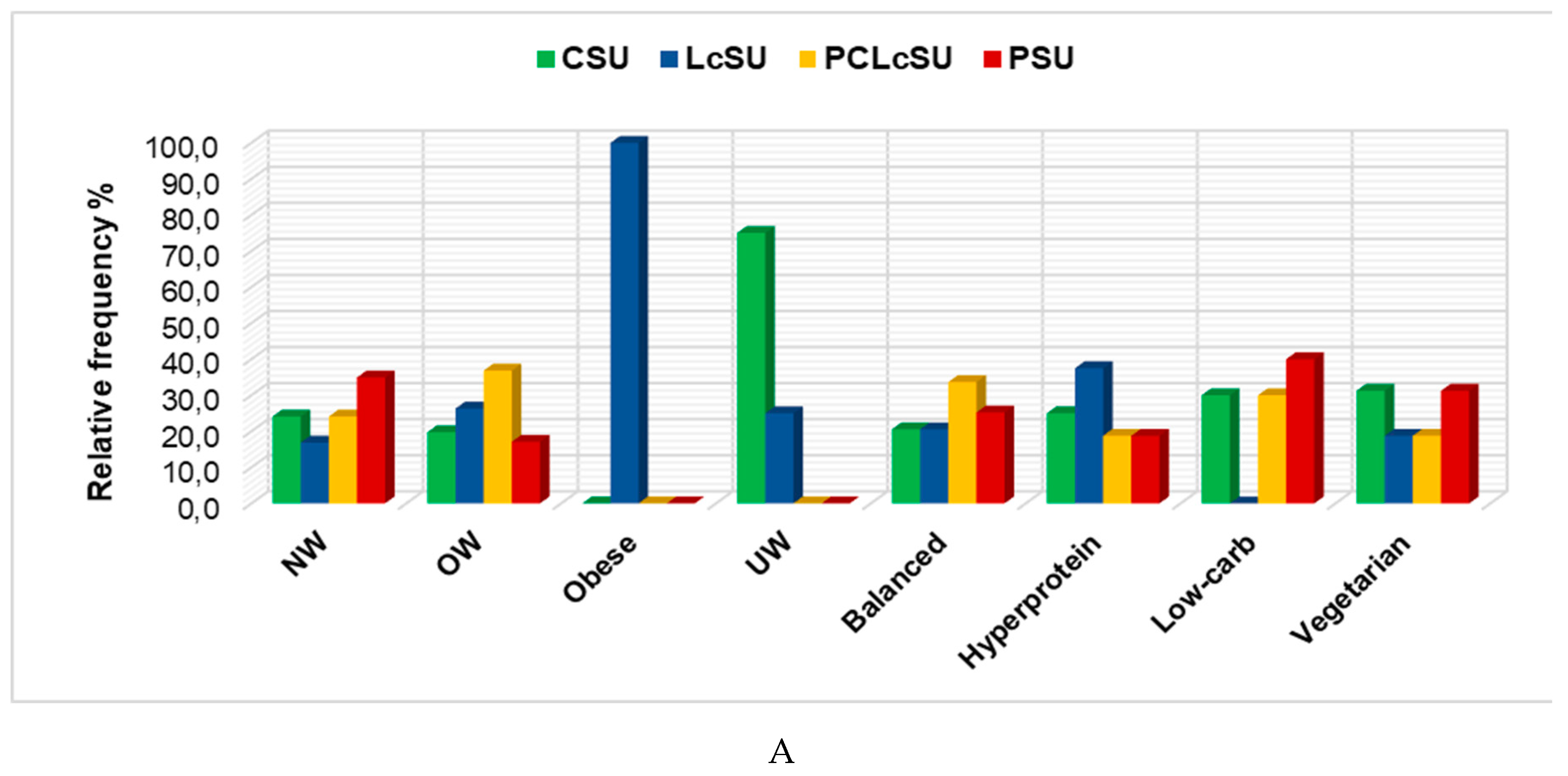

3.5.3. NS Consumption, Body Weight Status, and Daily Diet Properties

Obese gym-goers consume only L-carnitine (100%), while underweight ones choose creatine (75%) and L-carnitine (25%), p<0.05 (

Figure 5A). Overweight and normal-weight participants mainly prefer PCLcS and protein (

Figure 5A). Both supplements are primarily chosen for participants with a balanced and low-carb diet. Those with a hyperprotein diet prefer L-carnitine, while vegetarians use creatine and protein supplements (

Figure 5A).

Principal Component Analysis shows that LcS consumption substantially correlates with obese gym-goers (r = 0.999, p<0.05). In contrast, CS administration strongly correlates with UW (r = 0.943, p>0.05), PS with NW (r = 0.889, p>0.05), and PCLcS with OW (r = 0.898, p>0.05).

PCLcS and PS consumption show a considerable association with the Low-Carb Daily Diet (DD); LcS and PCS highly correlate with balanced DD; PCLcS use is also strongly associated with a vegetarian diet (r = 0.960—0.986, p<0.05).

Participants with > 3500 calories and > 250 g proteins use PCLcS exclusively, while those with < 50 g proteins complete their diet with protein supplementation (

Figure 5B,C). These supplements are the leading choice for gym-goers with 3001—3500 calories and 1000—1500 calories (PCLcS, p<0.05) and 50—100 g protein (PS, p<0.05).

4. Discussion

Nutritional supplement consumption among exercising people has drastically increased unnecessarily. Adequate research is essential to clarify the various facts regarding dietary supplements' necessity, efficacy, and appropriate use. In a survey with 1120 gym-goers from Brazil, 36.8% reported regularly taking supplements like protein and creatine to build muscle and strength. Products high in proteins and amino acids were consumed nearly every day by almost 60% of the participants, followed by isotonic beverages and carbs, with percentages of 32% and 23%. Supplements high in protein were taken by those under 30 years old, mostly men [

123]. This observation also fits our findings. The present study enrolled 165 participants (men: women ratio = 2:1) who are recreational gym practitioners. Their daily diet includes an NS (protein, creatine, L-carnitine), or their combination as a routine part of their lifestyle. The cohort was analyzed according to the type of NS intake. The PSU group is almost 23%, the CSU and LcSU groups are 22 and 25%, and the PCLcSU group is 29%. The socio-demographic data of the whole cohort showed that most participants were male (66%) vs. approximately 33% female. Over 52% are aged 18—30; thus, our findings confirm that the young gym-goers profile [

124]. The outcomes for professional activity demonstrated that the cohort was balanced between individuals with office work, physical activity type, and mixed activity with office work and physical effort. According to their BMI, almost 50% were normal-weight, 46% were overweight, 1% were obese, and 2% were underweight. These low percentages for extreme BMI values suggest that our gym-goers care about their health and physical features. Our study revealed significant associations between occupational activity, age, gender, and body weight categories. Obese participants have office work, suggesting that sedentary lifestyles in office-based occupations significantly contribute to excessive weight gain. The findings align with existing literature, indicating that reduced physical activity in workplace settings is a critical factor in the rising prevalence of obesity [

125].

In the present study, dietary patterns revealed substantial correlations with body weight and gender (p<0.05). Almost 65% of gym-goers have a balanced diet, while 19% opted for a hyperprotein diet, p<0.05. Vegetarian and low-carb diets are rare (9% and 6%, p<0.05). Sedentary participants are preponderantly oriented towards the vegetarian diet (14.5%), while obese ones prefer a balanced diet. Participants with a vegetarian diet, with high-calorie (DC >3500) and low protein (DP<50 g), were highly associated with overweight status (p<0.05). Many gym goers use protein supplements to reach this daily amount. However, 17% of participants could not report daily protein intake (14%) and daily calories (3%) due to a lack of nutrition knowledge, as previously revealed [

126]. Moreover, balanced and vegetarian diets are the most affordable: 50% and 62.5% of participants have a 2000 – 4000 RON monthly income.

Our findings report that the balanced diet consists of 1501-2500 calories/day (68%) and 50—150 g protein (54%). In this context, almost 59% of recreational gym-goers are PCLcSUs and PSUs, even if the extra supplementation is unnecessary; our findings fit the literature data [

77]. The hyperprotein diet involves a daily protein intake of 151—>250 g (87.5%) and daily calorie consumption of 2501— 3500 (90.6%), while the most used NS is L-carnitine (37.5%, p<0.05). Office workers prefer a Low-carb diet (60%); they intake 1000—2000 calories/daily (80%) and 151—250 g of protein (75%). A vegetarian diet also involves 1000–2000 calories/day (93%) but fewer proteins (50—150 g /day, 62.5%). LcS and PS highly correlate with a balanced diet, while PCLcS use is strongly associated with a vegetarian diet (r = 0.960—0.986, p<0.05). Hiperprotein and Low-carb diets need higher incomes: 4001—6000 RON (43.75%) and >6000 (40%). Moreover, bad habits (alcohol consumption and smoking) increase monthly expenses (monthly income>4000 RON: 55.54% and 67.35%, respectively), while most consumers (>50%) are young (18-30 years old) and prefer the triple combination (PCLcS). Associating protein, creatine, and L-carnitine (29%) and consuming them on the same day has synergistic benefits in muscle growth, strength, and recovery [

44,

127,

128].

The claims of increased muscle mass, higher fat loss, improved performance, and quick recovery led to the consumption of protein and amino acid supplements. The present study results show that the single choice of obese gym-goers was L-carnitine, known as a fat-burner [

129], while underweight ones chose creatine and L-carnitine (p<0.05). Creatine induces weight gain [

130], while L-carnitine may improve energy and physical activity, which could indirectly support weight gain if combined with a proper diet and strength training [

131].

Correlating the training period (months), frequency (times/weekly), duration (hours), and NS consumption, the outcomes highlighted the complex interplay between occupational activity, dietary habits, supplementation, training patterns, and body weight, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions to promote healthier behavioral choices. The study revealed strong associations between NS use and training durations; PCLcS combination is nearly perfectly associated with training sessions exceeding 2 hours and frequency > 5 times/week (p <0.05), while PS substantially correlates with gym period > 1 year (p<0.05). These findings confirm previous data regarding their benefits in RT [

132,

133].

Our gym-goers similarly used CS and LcS to ensure performance in force training (65.79% vs. 62.16%). Only CS use benefits are confirmed by literature data [

23,

134,

135,

136]. Moreover, they did not optimally valorize the strong and verified effects of PS or the synergistic combination PCLcS (42.86% and 47.92%, respectively). These findings suggest that the participants selected themselves and consumed protein supplements without the recommendation of a qualified practitioner, as previous studies claimed [

126,

137]. Only PCLcS is correctly associated with competitive scope (p<0.05), demonstrating the correct supplementation professionally supervised for a potential elite athlete.

Moreover, in only one supplement consumption, there was a significant correlation between CSUs and physical effort capacity, PSUs and physical effort recovery, weight loss, and LcSUs and fat-burning and consumption in MD time (p<0.05).

Moreover, the high incidence of harmful effects of NS use (30% in only one NS use and 100% in triple combination) supports the previous warnings regarding progressively increased and unnecessary sports supplement consumption [

77,

138,

139]. Diarrhea, nausea, and stomach cramps are substantially associated with LcS at 1—2 g/dose (p<0.05).

Whey protein at 40 and 60 g/dose significantly correlates with muscle cramps and liver damage (p<0.05), while CS at 1—5 g strongly correlates with weight gain (p<0.05).

Strengths and Limitations of the Present Study

The present study offers complex data regarding protein and amino acid supplements consumed by recreational gym-goers, considering various influential factors. Two qualified coaches selected the participants based on direct discussion with regular gym members known from their training sessions. Moreover, data collected through face-to-face interviews were more accurate than those obtained through an online questionnaire.

The results of the present study confirm all hypotheses. Most recreational athletes were young (18-30 years) and had academic studies. The men's percentage was twice that of women's; of the total group, 25% consumed all NS in combination. Our findings show that supplement consumption is influenced by sex, age, body weight, diet, gym duration, and training type and scope. The present study also reveals that all components act synergistically in the triple combination, stimulating muscle growth and strength; simultaneously, the side effects substantially increased.

Even if our study contains valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged, as follows:

- ○

The cohort selection process, which included only the regular members of 2 gym centers from the same Romanian city, did not ensure an optimal representation of all age groups;

- ○

All data were obtained from the participants, guaranteed by self-responsibility;

- ○

The cross-sectional design limits the possibility of establishing relationships between cause and effect;

- ○

The absence of measurements of biological parameters restricts the accurate evaluation of the effects of supplements on health.

5. Conclusions

The progressive increase in self-administration of nutritional supplements is hard to control and diminish because it is extended to recreational gym-goers and those not physically active.

Aiming to fill the gap between consumers' beliefs, expectations, and the potentially harmful effects of these supplements, the present study complexly investigated the consumption of commonly used protein and amino acids in recreational gym-goers from Northeastern Romania. It provides essential data about this phenomenon, which is associated with numerous influential factors, revealing a high incidence of harmful effects of protein and amino acid supplementation without a healthcare professional's advice.

Our findings underscore the need for educational programs focused on healthy nutrition, ensuring necessary nutrients primarily through an optimal diet, and limiting the overuse of supplementation unless medically necessary.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-R.N., M.M., V.P., R.-C.M., A.P., T.J.; methodology, S.- R.N.., M.M., and V.P.; software, V.P.; validation, M.M., V.P., R.-C.M., A.P., and T.J.; formal Analysis, M.M. and V.P.; investigation, S.-R.N., R.-C.M., A.P. and T.J.; writing–original draft preparation, S.- R.N., M.M., V.P.and R.-C.M..; writing–review and editing, M.M., and V.P.; visualization, S.-R.N., M.M., V.P., R.-C.M., A.P., and T.J..; supervision, A.P. and T.J.; project administration S.-R.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was founded by the University of Oradea, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine and Pharmacy, University of Oradea, Romania, No. 21/25 February 2021, and Gym Committee No 7/3 October 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the first author.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the University of Oradea for supporting the payment of the invoice through an internal project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lonnie, M.; Johnstone, A.M. The Public Health Rationale for Promoting Plant Protein as an Important Part of a Sustainable and Healthy Diet. Nutr Bull 2020, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollmar, M.; Sjöberg, A.; Post, A. Swedish Recreational Athletes as Subjects for Sustainable Food Consumption: Focus on Performance and Sustainability. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2022, 73, 1132–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirtha, L.T.; Tulaar, A.; Pramantara, I.D.P. Towards Healthy Aging with Physical Activity and Nutrition. Amerta Nutrition 2021, 4, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ne'eman-Haviv, V.; Bonny-Noach, H.; Berkovitz, R.; Arieli, M. Attitudes, Knowledge, and Consumption of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids by Recreational Gym Goers in Israel. Sport Soc 2021, 24, 1527–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmela, P.; Pačesová, P.; Kraček, S.; Hájovský, D. Performance Motivation of Elite Athletes, Recreational Athletes and Non-Athletes. Acta Facultatis Educationis Physicae Universitatis Comenianae 2017, 57, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsitsimpikou, C.; Chrisostomou, N.; Papalexis, P.; Tsarouhas, K.; Tsatsakis, A.; Jamurtas, A. The Use of Nutritional Supplements Among Recreational Athletes in Athens, Greece. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2011, 21, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devries, M.C.; Phillips, S.M. Supplemental Protein in Support of Muscle Mass and Health: Advantage Whey. J Food Sci 2015, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhasin, S.; Apovian, C.M.; Travison, T.G.; Pencina, K.; Moore, L.L.; Huang, G.; Campbell, W.W.; Li, Z.; Howland, A.S.; Chen, R.; et al. Effect of Protein Intake on Lean Body Mass in Functionally Limited Older Men. JAMA Intern Med 2018, 178, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beasley, J.M.; Deierlein, A.L.; Morland, K.B.; Granieri, E.C.; Spark, A. Is Meeting the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for Protein Related to Body Composition among Older Adults?: Results from the Cardiovascular Health of Seniors and Built Environment Study. J Nutr Health Aging 2016, 20, 790–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R.; Kerksick, C.M.; Campbell, B.I.; Cribb, P.J.; Wells, S.D.; Skwiat, T.M.; Purpura, M.; Ziegenfuss, T.N.; Ferrando, A.A.; Arent, S.M.; et al. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: Protein and Exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2017, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Chen, N.; Ashaolu, T.J. Whey Proteins and Peptides in Health-Promoting Functions – A Review. Int Dairy J 2022, 126, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newar, V.; Tura, D. A Review on Whey Protein: Benefits, Myths and Facts. Int J Innov Sci Res Technol 2022, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Antonio, J.; Evans, C.; Ferrando, A.A.; Stout, J.R.; Antonio, B.; Cinteo, H.; Harty, P.; Arent, S.M.; Candow, D.G.; Forbes, S.C.; et al. Common Questions and Misconceptions about Protein Supplementation: What Does the Scientific Evidence Really Show? J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.M.; Moore, D.R.; Tang, J.E. A Critical Examination of Dietary Protein Requirements, Benefits, and Excesses in Athletes. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2007, 17 Suppl. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hespel, P.; Derave, W. Ergogenic Effects of Creatine in Sports and Rehabilitation. In Creatine and Creatine Kinase in Health and Disease; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2007; Vol. 46, pp. 246–259. [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan, J.T.; da Silva, R.P.; Brosnan, M.E. The Metabolic Burden of Creatine Synthesis. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1325–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VULTURAR, R.; JURJIU, B.; DAMIAN, M.; BOJAN, A.; PINTILIE, S.R.; JURCĂ, C.; CHIȘ, A.; GRAD, S. Creatine Supplementation and Muscles: From Metabolism to Medical Practice. Romanian Journal of Medical Practice 2021, 16, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, R.; Purpura, M.; Shao, A.; Inoue, T.; Kreider, R.B. Analysis of the Efficacy, Safety, and Regulatory Status of Novel Forms of Creatine. Amino Acids 2011, 40, 1369–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tack, C. Dietary Supplementation During Musculoskeletal Injury. Strength Cond J 2016, 38, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solis, M.Y.; Dolan, E.; Artioli, G.G.; Gualano, B. Creatine Supplementation in the Aging Brain. In Assessments, Treatments and Modeling in Aging and Neurological Disease; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 379–388. [Google Scholar]

- Candow, D.G.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Chad, K.E.; Chrusch, M.J.; Davison, K.S.; Burke, D.G. Effect of Ceasing Creatine Supplementation While Maintaining Resistance Training in Older Men. J Aging Phys Act 2004, 12, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.C.; Söderlund, K.; Hultman, E. Elevation of Creatine in Resting and Exercised Muscle of Normal Subjects by Creatine Supplementation. Clin Sci 1992, 83, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHRUSCH, M.J.; CHILIBECK, P.D.; CHAD, K.E.; SHAWN DAVISON, K.; BURKE, D.G. Creatine Supplementation Combined with Resistance Training in Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001, 33, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.L.L.; Ong, W.S.; GillianYap, T.L.; Lim, S.C.J.; Chia, E. Von Effects of Two and Five Days of Creatine Loading on Muscular Strength and Anaerobic Power in Trained Athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2009, 23, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qiu, B.; Li, R.; Han, Y.; Petersen, C.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Candow, D.G.; Del Coso, J. Effects of Creatine Supplementation and Resistance Training on Muscle Strength Gains in Adults <50 Years of Age: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilibeck, P.; Kaviani, M.; Candow, D.; Zello, G.A. Effect of Creatine Supplementation during Resistance Training on Lean Tissue Mass and Muscular Strength in Older Adults: A Meta-Analysis. Open Access J Sports Med 2017, Volume 8, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvan, E.; Walker, D.K.; Simbo, S.Y.; Dalton, R.; Levers, K.; O’Connor, A.; Goodenough, C.; Barringer, N.D.; Greenwood, M.; Rasmussen, C.; et al. Acute and Chronic Safety and Efficacy of Dose Dependent Creatine Nitrate Supplementation and Exercise Performance. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilborn, C.D.; Outlaw, J.J.; Mumford, P.W.; Urbina, S.L.; Hayward, S.; Roberts, M.D.; Taylor, L.W.; Foster, C.A. A Pilot Study Examining the Effects of 8-Week Whey Protein versus Whey Protein Plus Creatine Supplementation on Body Composition and Performance Variables in Resistance-Trained Women. Ann Nutr Metab 2016, 69, 190–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- COLLINS, J.; LONGHURST, G.; ROSCHEL, H.; GUALANO, B. RESISTANCE TRAINING AND CO-SUPPLEMENTATION WITH CREATINE AND PROTEIN IN OLDER SUBJECTS WITH FRAILTY. Journal of Frailty & Aging 2016, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virmani, M.A.; Cirulli, M. The Role of L-Carnitine in Mitochondria, Prevention of Metabolic Inflexibility and Disease Initiation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlic, H.; Lohninger, A. Supplementation of L-Carnitine in Athletes: Does It Make Sense? Nutrition 2004, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoni, A.; Longo, S.; Gnoni, G. V.; Giudetti, A.M. Carnitine in Human Muscle Bioenergetics: Can Carnitine Supplementation Improve Physical Exercise? Molecules 2020, 25, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-García, A.; Noriega-González, D.C.; Roche, E.; Drobnic, F.; Córdova, A. Effects of L-Carnitine Intake on Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage and Oxidative Stress: A Narrative Scoping Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuwasawa-Iwasaki, M.; Io, H.; Muto, M.; Ichikawa, S.; Wakabayashi, K.; Kanda, R.; Nakata, J.; Nohara, N.; Tomino, Y.; Suzuki, Y. Effects of L-Carnitine Supplementation in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis or Peritoneal Dialysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, M.; Ogawa, K.; Suda, G.; Kimura, M.; Maehara, O.; Shimazaki, T.; Suzuki, K.; Nakamura, A.; Umemura, M.; Izumi, T.; et al. L-Carnitine Suppresses Loss of Skeletal Muscle Mass in Patients With Liver Cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun 2018, 2, 910–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedbalska-tarnowska, J.; Ochenkowska, K.; Migocka-patrzałek, M.; Dubińska-magiera, M. Assessment of the Preventive Effect of L-carnitine on Post-statin Muscle Damage in a Zebrafish Model. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakanishi, H.; Kurosaki, M.; Tsuchiya, K.; Nakakuki, N.; Takada, H.; Matsuda, S.; Gondo, K.; Asano, Y.; Hattori, N.; Tamaki, N.; et al. L-Carnitine Reduces Muscle Cramps in Patients With Cirrhosis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2015, 13, 1540–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Park, J.; Chang, H.; Lim, K. <scp>l</Scp> -Carnitine Supplement Reduces Skeletal Muscle Atrophy Induced by Prolonged Hindlimb Suspension in Rats. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2016, 41, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, T.; Hanai, T.; Morino, K.; Katsumura, N.; Shimizu, M. Effect of L-Carnitine Supplementation on Muscle Cramps Induced by Stroke: A Case Report. Nutrition 2020, 71, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasiljevski, E.R.; Burns, J.; Bray, P.; Donlevy, G.; Mudge, A.J.; Jones, K.J.; Summers, M.A.; Biggin, A.; Munns, C.F.; McKay, M.J.; et al. L-carnitine Supplementation for Muscle Weakness and Fatigue in Children with Neurofibromatosis Type 1: A Phase 2a Clinical Trial. Am J Med Genet A 2021, 185, 2976–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, M.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Li, N.; Yin, L.; Wang, H.; Song, W.; Xu, H. L-Carnitine Ameliorates the Muscle Wasting of Cancer Cachexia through the AKT/FOXO3a/MaFbx Axis. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2021, 18, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPIERING, B.A.; KRAEMER, W.J.; VINGREN, J.L.; HATFIELD, D.L.; FRAGALA, M.S.; HO, J.-Y.; MARESH, C.M.; ANDERSON, J.M.; VOLEK, J.S. RESPONSES OF CRITERION VARIABLES TO DIFFERENT SUPPLEMENTAL DOSES OF L-CARNITINE L-TARTRATE. J Strength Cond Res 2007, 21, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orer, G.E.; Guzel, N.A. The Effects of Acute L-Carnitine Supplementation on Endurance Performance of Athletes. J Strength Cond Res 2014, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Guthrie, N.; Pezzullo, J.; Sanli, T.; Fielding, R.A.; Bellamine, A. Efficacy of a Novel Formulation of L-Carnitine, Creatine, and Leucine on Lean Body Mass and Functional Muscle Strength in Healthy Older Adults: A Randomized, Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2017, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourshahidi, L.K.; Mullan, R.; Collins, N.; O'Mahony, S.; Slevin, M.M.; Magee, P.J.; Kerr, M.A.; Sittlington, J.J.; Simpson, E.E.A.; Hughes, C.F. Reporting Adverse Events Linked to the Consumption of Food Supplements and Other Food Products: An Audit of Nutrivigilance Newsletters. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2021, 80, E133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.-J.; Rhee, C.M.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Joshi, S. The Effects of High-Protein Diets on Kidney Health and Longevity. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2020, 31, 1667–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moe, S.M.; Zidehsarai, M.P.; Chambers, M.A.; Jackman, L.A.; Radcliffe, J.S.; Trevino, L.L.; Donahue, S.E.; Asplin, J.R. Vegetarian Compared with Meat Dietary Protein Source and Phosphorus Homeostasis in Chronic Kidney Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Lomelí, H.; Trujillo-Hernández, B.; Espinoza-Gómez, F.; Vargas-Aguirre, P.; Orozco-Martinez, A.; Negrete-Cruz, A.M.; Guzmán-Esquivel, J.; Delgado-Enciso, I. Protein Supplement Use and Prevalence of Microalbuminuria in Gym Members. Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 2019, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benić, A.; Mikašinović, S.; Wensveen, F.M.; Polić, B. Activation of Granulocytes in Response to a High Protein Diet Leads to the Formation of Necrotic Lesions in the Liver. Metabolites 2023, 13, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Rúa, R.; Keijer, J.; Palou, A.; van Schothorst, E.M.; Oliver, P. Long-Term Intake of a High-Protein Diet Increases Liver Triacylglycerol Deposition Pathways and Hepatic Signs of Injury in Rats. J Nutr Biochem 2017, 46, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsik, M.; Nazimek, K.; Nowak, B.; Askenase, P.W.; Bryniarski, K. Delayed-Type Hypersensitivity Underlying Casein Allergy Is Suppressed by Extracellular Vesicles Carrying MiRNA-150. Nutrients 2019, 11, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, S.B.; Towle, K.M.; Monnot, A.D. A Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metal Ingestion among Consumers of Protein Powder Supplements. Toxicol Rep 2020, 7, 1255–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.N.; Mann, N.J.; Braue, A.; Mäkeläinen, H.; Varigos, G.A. The Effect of a High-Protein, Low Glycemic–Load Diet versus a Conventional, High Glycemic–Load Diet on Biochemical Parameters Associated with Acne Vulgaris: A Randomized, Investigator-Masked, Controlled Trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007, 57, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cengiz, F.P.; Cevirgen Cemil, B.; Emiroglu, N.; Gulsel Bahali, A.; Onsun, N. Acne Located on the Trunk, Whey Protein Supplementation: Is There Any Association? Health Promot Perspect 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Ellerbroek, A.; Evans, C.; Silver, T.; Peacock, C.A. High Protein Consumption in Trained Women: Bad to the Bone? J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2018, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butts, J.; Jacobs, B.; Silvis, M. Creatine Use in Sports. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach 2018, 10, 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.; Huidobro E., J. P. Efectos En La Función Renal de La Suplementación de Creatina Con Fines Deportivos. Rev Med Chil 2019, 147, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taner, B.; Aysim, O.; Abdulkadir, U. The Effects of the Recommended Dose of Creatine Monohydrate on Kidney Function. NDT Plus 2011, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinello, P.C.; Cella, P.S.; Testa, M.T.J.; Guirro, P.B.; da Silva Brito, W.A.; Padilha, C.S.; Cecchini, A.L.; da Silva, R.P.; Duarte, J.A.R.; Deminice, R. Creatine Supplementation Protects against Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver but Exacerbates Alcoholic Fatty Liver. Life Sci 2022, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinello, P.C.; Cella, P.S.; Testa, M.T.J.; Guirro, P.B.; Brito, W.A.S.; Borges, F.H.; Cecchini, R.; Cecchini, A.L.; Duarte, J.A.; Deminice, R. Creatine Supplementation Exacerbates Ethanol-Induced Hepatic Damage in Mice. Nutrition 2019, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhang, D.-M.; Wang, M.-X.; Fan, C.-Y.; Zhou, F.; Wang, S.-J.; Kong, L.-D. The Adverse Effects of Long-Term <scp>l</Scp> -Carnitine Supplementation on Liver and Kidney Function in Rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 2015, 34, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, A.K.; Renzi, G.; Olek, R.A. The Bright and the Dark Sides of L-Carnitine Supplementation: A Systematic Review. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppe, L.; Huret, F.; Mathiot, C. The Nutrition Professionals Are Key Players for Reporting and Analyzing Adverse Events of Nutrition Products. Experience of the French National Nutrivigilance System for Dietary Supplements Containing Turmeric. Clin Nutr ESPEN 2023, 58, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banach, M.; Katsiki, N.; Latkovskis, G.; Rizzo, M.; Pella, D.; Penson, P.E.; Reiner, Z.; Cicero, A.F.G. Postmarketing Nutrivigilance Safety Profile: A Line of Dietary Food Supplements Containing Red Yeast Rice for Dyslipidemia. Archives of Medical Science 2021, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenn, P. Benefits and Risks of Dietary Supplements. Nutrition Clinique et Metabolisme 2020, 34. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, A.; Geboers, L.; van de Koppel, S.; van Hunsel, F. Governance of Nutrivigilance in the Netherlands: Reporting Adverse Events of Non-Registered Products. Health Policy (New York) 2022, 126, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vo Van Regnault, G.; Costa, M.C.; Adanić Pajić, A.; Bico, A.P.; Bischofova, S.; Blaznik, U.; Menniti-Ippolito, F.; Pilegaard, K.; Rodrigues, C.; Margaritis, I. The Need for European Harmonization of Nutrivigilance in a Public Health Perspective: A Comprehensive Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cynober, L. (Bien)Faits et Méfaits Des Compléments Alimentaires. Bull Acad Natl Med 2022, 206, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malve, H.; Fernandes, M. Nutrivigilance – The Need of the Hour. Indian J Pharmacol 2023, 55, 62–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, V.R.; Toklu, H.Z. Nutrivigilance: The Road Less Traveled. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kofoed, C.L.F.; Christensen, J.; Dragsted, L.O.; Tjønneland, A.; Roswall, N. Determinants of Dietary Supplement Use – Healthy Individuals Use Dietary Supplements. British Journal of Nutrition 2015, 113, 1993–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, C.W.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, A.H. Problems and Prospects: Public Health Regulation of Dietary Supplements. Annu Rev Public Health 2018, 39, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barjaktarovic Labovic, S.; Banjari, I.; Joksimovic, I.; Djordjevic, Z.; Balkić Widmann, J.; Djurovic, D. Sport Nutrition Knowledge among Athletes and Recreational People. In Proceedings of the The 14th European Nutrition Conference FENS 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, March 11, 2024; p. 401. [Google Scholar]

- Borges, L.P.S.L.; Sousa, A.G.; da Costa, T.H.M. Physically Inactive Adults Are the Main Users of Sports Dietary Supplements in the Capital of Brazil. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 2321–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sindhuja, M.; Verma, L.; Gupta, L.; Lal, P.R. Use of Nutritional Ergogenic Aids by Adults Training for Health-Related Fitness in Gymnasia- A Scoping Review. Indian J Nutr Diet 2023, 60, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewan, T.; Bettina, K.; Fatma Nese, S.; Goktug, E.; Francesco, M.; Vincenza, L.; Antonio, P.; Paulo, G.; Antonio, P.; Antonino, B. Protein Supplement Consumption Is Linked to Time Spent Exercising and High-Protein Content Foods: A Multicentric Observational Study. Heliyon 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemet, D.; Wolach, B.; Eliakim, A. Proteins and Amino Acid Supplementation in Sports: Are They Truly Necessary? Israel Medical Association Journal 2005, 7, 328–332. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, A.; Mammina, C.; Thomas, E.; Ciulla, F.; Pupella, U.; Gagliardo, F.; Bellafiore, M.; Battaglia, G.; Paoli, A.; Palma, A. Protein Supplements Consumption: A Comparative Study between the City Centre and the Suburbs of Palermo, Italy. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 2014, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramic, M.; Jovanovic, M.; Nikolic, M.; Ramic, M.; Nikolic, K. Use of Dietary Supplements among Male Fitness Club Members in Nis, Serbia. Eur J Public Health 2020, 30, ckaa166.213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, D.; Balteiro, J.; Rocha, C. Consumption of Nutritional Supplements by Gym Attendants and Health Clubs. Eur J Public Health 2021, 31, ckab120.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, J.; Pereira, F.; Curtis, J.; Rojas, J.; Evans, C. The Top 5 Can't-Miss Sport Supplements. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, S.; Cunha, M.; Costa, J.G.; Ferreira-Pêgo, C. Analysis of Food Supplements and Sports Foods Consumption Patterns among a Sample of Gym-Goers in Portugal. J Int Soc Sports Nutr 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeling, P.; Binnie, M.J.; Goods, P.S.R.; Sim, M.; Burke, L.M. Evidence-Based Supplements for the Enhancement of Athletic Performance. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 2018, 28, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, L.T.; Ozcan, B.A.; Erem, S.; Ercan, A.; Akkaya, İ.; Basarir, A. Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour of Physical Education and Sports Students’ about Dietary Supplements. Progress in Nutrition 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, S.; El Koofy, N.; Moawad, E.M.I. Patterns of Nutrition and Dietary Supplements Use in Young Egyptian Athletes: A Community-Based Cross-Sectional Survey. PLoS One 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danh, J.P.; Nucci, A.; Andrew Doyle, J.; Feresin, R.G. Assessment of Sports Nutrition Knowledge, Dietary Intake, and Nutrition Information Source in Female Collegiate Athletes: A Descriptive Feasibility Study. Journal of American College Health 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Yaman, M.; Ibrahim, M.O. The Consumption of Dietary Supplements among Gym Members in Amman, Jordan. Progress in Nutrition 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skopinceva, J. Assessing the Nutrition Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs of Fitness Professionals. Adv Obes Weight Manag Control 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed P, V.; Dinesh, Prof.Dr.G. A Study on Lifestyle Pattern Associated with Diet, Physical Activity, and Body Mass Index in a Case of GYM Goers. INTERANTIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH IN ENGINEERING AND MANAGEMENT 2023, 07, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Attlee, A.; Haider, A.; Hassan, A.; Alzamil, N.; Hashim, M.; Obaid, R.S. Dietary Supplement Intake and Associated Factors Among Gym Users in a University Community. J Diet Suppl 2018, 15, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Mweis, S.S.; Alatrash, R.M.; Tayyem, R.; Hammoudeh, A. Sex and Age Are Associated with the Use of Specific Dietary Supplements among People Exercising in Gyms: Cross-Sectional Analysis from Amman, Jordan. Med J Nutrition Metab 2019, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, A.S.; León, M.T.M.; Guerra-Hernández, E. Prevalence of Protein Supplement Use at Gyms Estudio Estadístico Del Consumo de Suplementos Proteícos En Gimnasios. Nutr Hosp 2011, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Hilkens, L.; Cruyff, M.; Woertman, L.; Benjamins, J.; Evers, C. Social Media, Body Image and Resistance Training: Creating the Perfect 'Me' with Dietary Supplements, Anabolic Steroids and SARM's. Sports Med Open 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhekail, O.; Almeshari, A.; Alabdulkarim, B.; Alkhalifa, M.; Almarek, N.; Alzuman, O.; Abdo, A. Prevalence and Patterns of the Use of Protein Supplements Among Gym Users in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Available online www.ijpras.com International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research & Allied Sciences 2018, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Senekal, M.; Meltzer, S.; Horne, A.; Abrey, N.C.G.; Papenfus, L.; van der Merwe, S.; Temple, N.J. Dietary Supplement Use in Younger and Older Men Exercising at Gyms in Cape Town. South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, A.J.; Livingstone, K.M.; Woods, J.L.; McNaughton, S.A. Dietary Supplement Use among Australian Adults: Findings from the 2011–2012 National Nutrition and Physical Activity Survey. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, R.P.D.; Vargas, S.V.D.; Lopes, W.C. Consumption of Food Supplements of Physical Activity Practitioners within Fitness Centers. RBNE-REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE NUTRICAO ESPORTIVA 2017, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Molz, P.; Rossi, R.M.; Schlickmann, D.S.; Dos Santos, C.; Franke, S.I.R. Dietary Supplement Use and Its Associated Factors among Gym Users in Southern Brazil. J Subst Use 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, R.V.; Antohi, V.M.; Zlati, M.L.; Iconomescu, M.T.; Nechifor, A.; Stanciu, S. Consumption of Nutritive Supplements during Physical Activities in Romania: A Qualitative Study. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagaras, P.S.; Teodorescu, S.V.; Bacarea, A.; Petrea, R.G.; Ursanu, A.I.; Cozmei, G.; Radu, L.E.; Vanvu, G.I. Aspects Regarding the Consumption of Dietary Supplements among the Active Population in Romania. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgovan, C.; Ghibu, S.; Juncan, A.M.; Rus, L.L.; Butucă, A.; Vonica, L.; Muntean, A.; Moş, L.; Gligor, F.; Olah, N.K. Nutrivigilance: A New Activity in the Field of Dietary Supplements. Farmacia 2019, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedruscolo, G.; Ivernizo, L.; Braga, T.; Triffoni, A. Utilização Dos Suplementos Nutricionais Creatina, Concentrado Proteico (Whey Protein) e Aminoácidos de Cadeia Ramificada (BCAAs), Por Indivíduos Praticantes de Musculação. Revista Brasileira de Nutriçao Esportiva 2023, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Gianfredi, V.; Ceccarelli, F.; Villarini, M.; Moretti, M.; Nucci, D. Food Supplements Intake among Gym-goers: A Cross-Sectional Study Using ThePILATES Questionnaire. Nutr Food Sci 2020, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, F.; Crovetto, M.; González, A.; Morant, N.; Santibáñez, F. Nutritional Supplement Intake in Gymnasium, Consumer Profile and Charateristics of Their Use. Revista Chilena de Nutricion 2011, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Mukolwe, H.; Rintaugu, E.G.; Mwangi, F.M.; Rotich, J.K. Prevalence and Attitudes towards Nutritional Supplements Use among Gymnasium Goers in Eldoret Town, Kenya. Scientific Journal of Sport and Performance 2023, 2, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, D.; Antoine-Jonville, S. Intake of Nutritional Supplements among People Exercising in Gyms in Beirut City. J Nutr Metab 2012, 2012, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez Oliver, A.J.; Miranda Leon, M.T.; Guerra Hernandez, E. Statistical Analysis of the Consumption of Nutritional and Dietary Supplements in Gyms. Arch Latinoam Nutr 2008, 58. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.C.; Lüdorf, S.M.A. Dietary Supplements and Body Management of Practicers of Physical Activity in Gyms. Cien Saude Colet 2021, 26, 4351–4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacerda, F.M.M.; Carvalho, W.R.G.; Hortegal, E.V.; Cabral, N.A.L.; Veloso, H.J.F. Factors Associated with Dietary Supplement Use by People Who Exercise at Gyms. Rev Saude Publica 2015, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assessment of Dietary and Supplementary Consumption of Bodybuilders in Gyms in João Pessoa. Revista Intercontinental de Gestão Desportiva 2021, 01–15. [CrossRef]

- Singhvi, B.; Gokhale, D. Usage of Nutritional Supplements and Its Side Effects among Gym Goers in Pune. CARDIOMETRY 2021, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharirad, N.; Komasi, S.; Khatooni, A.; Moradi, F.; Soroush, A. Frequency and Causes of Consuming Sports Supplements and Understanding Their Side Effects Among Bodybuilders in Fitness Gyms of Kermanshah City. Curr Nutr Food Sci 2019, 15, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191. [CrossRef]

- Tătar, C.-F.; Dincă, I.; Linc, R.; Stupariu, M.I.; Bucur, L.; Stașac, M.S.; Nistor, S. Oradea Metropolitan Area as a Space of Interspecific Relations Triggered by Physical and Potential Tourist Activities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, J.; Sospedra, I.; Ortiz, C.; Baladía, E.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Ortiz-Moncada, R. Intended or Unintended Doping? A Review of the Presence of Doping Substances in Dietary Supplements Used in Sports. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulery, J.A.; Melton, B.F.; Bland, H.; Riggs, A.J. Associations Between Health Status, Training Level, Motivations for Exercise, and Supplement Use Among Recreational Runners. J Diet Suppl 2022, 19, 640–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goston, J.L.; Toulson Davisson Correia, M.I. Intake of Nutritional Supplements among People Exercising in Gyms and Influencing Factors. Nutrition 2010, 26, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel, R.Q.; Eaton, A.W.; O??Brien, K.F.; Hortob??gyi, T.; McCammon, M.R. COMPARISON OF FOUR METHODS TO ASSESS BODY COMPOSITION IN WOMEN. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1992, 24, S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroșan, E.; Popovici, V.; Popescu, I.A.; Daraban, A.; Karampelas, O.; Matac, L.M.; Licu, M.; Rusu, A.; Chirigiu, L.-M.-E.; Opriţescu, S.; et al. Perception, Trust, and Motivation in Consumer Behavior for Organic Food Acquisition: An Exploratory Study. Foods 2025, 14, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, C.M.; Lupu, A.; Chisnoiu, T.; Balasa, A.L.; Baciu, G.; Fotea, S.; Lupu, V.V.; Popovici, V.; Cambrea, S.C.; Grigorian, M.; et al. Clinical and Epidemiological Characteristics of Pediatric Pertussis Cases: A Retrospective Study from Southeast Romania. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, C.M.; Lupu, A.; Chisnoiu, T.; Balasa, A.L.; Baciu, G.; Lupu, V.V.; Popovici, V.; Suciu, F.; Enache, F.-D.; Cambrea, S.C.; et al. A Comprehensive Analysis of Echinococcus Granulosus Infections in Children and Adolescents: Results of a 7-Year Retrospective Study and Literature Review. Pathogens 2025, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streba, L.; Popovici, V.; Mihai, A.; Mititelu, M.; Lupu, C.E.; Matei, M.; Vladu, I.M.; Iovănescu, M.L.; Cioboată, R.; Călărașu, C.; et al. Integrative Approach to Risk Factors in Simple Chronic Obstructive Airway Diseases of the Lung or Associated with Metabolic Syndrome—Analysis and Prediction. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheffer, N.M.; Benetti, F. Analysis of the Consumption of Food Supplements and the Body Perception in Physical Exercises Practitioners in Gym in the City of Palmitinho-RS. RBNE-REVISTA BRASILEIRA DE NUTRICAO ESPORTIVA 2016, 10. [Google Scholar]

- da Fonseca Vilela, G.; Rombaldi, A.J. Perfil Dos Frequentadores Das Academias de Ginástica de Um Município Do Rio Grande Do Sul. Revista Brasileira em promoção da Saúde 2015, 28, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dėdelė, A.; Bartkutė, Ž.; Chebotarova, Y.; Miškinytė, A. The Relationship Between the Healthy Diet Index, Chronic Diseases, Obesity and Lifestyle Risk Factors Among Adults in Kaunas City, Lithuania. Front Nutr 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucherville Pereira, I.S. de; Lima, K.R.; Teodoro da Silva, R.C.; Pereira, R.C.; Fernandes da Silva, S.; Gomes de Moura, A.; César de Abreu, W. Evaluation of General and Sports Nutritional Knowledge of Recreational Athletes. Nutr Health 2025, 31, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Candow, D.G.; Chilibeck, P.D.; Grand, T.; Chad, K.E. The Effectiveness Of Creatine Combined With Protein Supplementation During Resistance Training In Older Men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005, 37, S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CRIBB, P.J.; WILLIAMS, A.D.; STATHIS, C.G.; CAREY, M.F.; HAYES, A. Effects of Whey Isolate, Creatine, and Resistance Training on Muscle Hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007, 39, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leelarungrayub, J.; Pinkaew, D.; Klaphajone, J.; Eungpinichpong, W.; Bloomer, R.J. Effects of L-Carnitine Supplementation on Metabolic Utilization of Oxygen and Lipid Profile among Trained and Untrained Humans. Asian J Sports Med 2016, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, L.; Chouchani, E.T.; Lu, G.Z.; Jedrychowski, M.P.; Bare, C.J.; Mina, A.I.; Kumari, M.; Zhang, S.; Vuckovic, I.; Laznik-Bogoslavski, D.; et al. Genetic Depletion of Adipocyte Creatine Metabolism Inhibits Diet-Induced Thermogenesis and Drives Obesity. Cell Metab 2017, 26, 660–671.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerretelli, P.; Marconi, C. L-Carnitine Supplementation in Humans. The Effects on Physical Performance. Int J Sports Med 1990, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, N.M.; Res, P.T.; de Groot, L.C.; Saris, W.H.; van Loon, L.J. Protein Supplementation Augments the Adaptive Response of Skeletal Muscle to Resistance-Type Exercise Training: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 2012, 96, 1454–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]