Submitted:

13 October 2025

Posted:

14 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

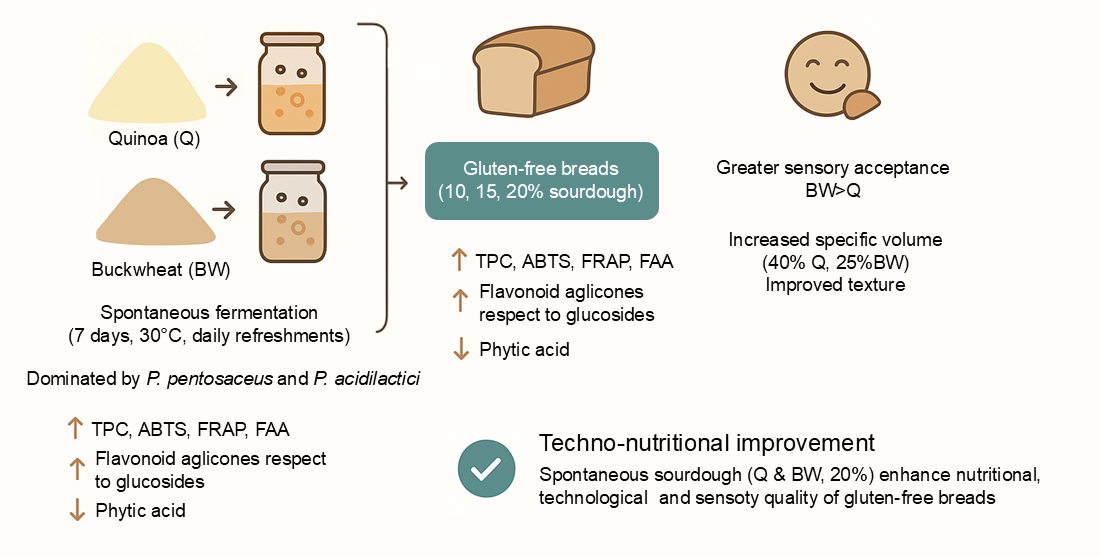

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of spontaneous sourdoughs on the quality of gluten-free breads formulated with quinoa (Q) and buckwheat (BW) flours, in order to improve their nutritional, technological, and sensory attributes. The microbiota of the sourdoughs was dominated by Pediococcus pentosaceus and P. acidilactici. Total polyphenols, antioxidant capacity, phytic acid, and free amino acids were determined in sourdoughs (before and after fermentation), and breads. Breads were prepared with three levels of sourdough, 10%, 15%, and 20%. Bread specific volume, crumb firmness, staling rate, crumb structure, and consumer acceptability were evaluated. Sourdoughs showed higher phenolic compound contents compared to the unfermented control, and breads with sourdough contained on average 67% more phenolics than control breads. Antioxidant activity also increased, particularly in BW sourdough samples. Phytic acid decreased in both sourdoughs and breads, while free amino acids increased. Breads with Q and BW sourdoughs exhibited 40% and 25% higher specific volume, respectively, than the control, along with lower firmness and slower staling. BW sourdough breads reached the highest overall consumer acceptance. Incorporation of Q and BW spontaneous sourdoughs, especially at 20% substitution, significantly improved the nutritional, technological, and sensory quality of gluten-free breads.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Quinoa and Buckwheat Sourdoughs

2.3. Sourdough Characterisation

2.3.1. LAB and Yeast Identification

2.3.2. pH, Total Titratable Acidity (TTA) and Cell Count

2.4. Breadmaking

2.5. Evaluation of Bread Technological Quality

2.6. Nutritional Quality

2.6.1. Total Polyphenol Extraction

2.6.2. Total Polyphenol Content (TPC) and Antioxidant Capacity

2.6.3. Identification and Quantification of Phenolic Compounds

2.6.4. Free Amino Acid Content (FAA)

2.6.5. Phytic Acid Content (PA)

2.7. Sensory Analysis of Breads

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sourdough Characterization

3.2. Bioactive and Nutritional Compounds

3.2.1. Total Polyphenol Content and Antioxidant Activity

3.2.2. Polyphenol Profile

3.2.3. Phytic Acid Content

3.2.4. Free Amino Acid Content (FAA)

3.3. Technological Quality

3.4. Sensory Analysis

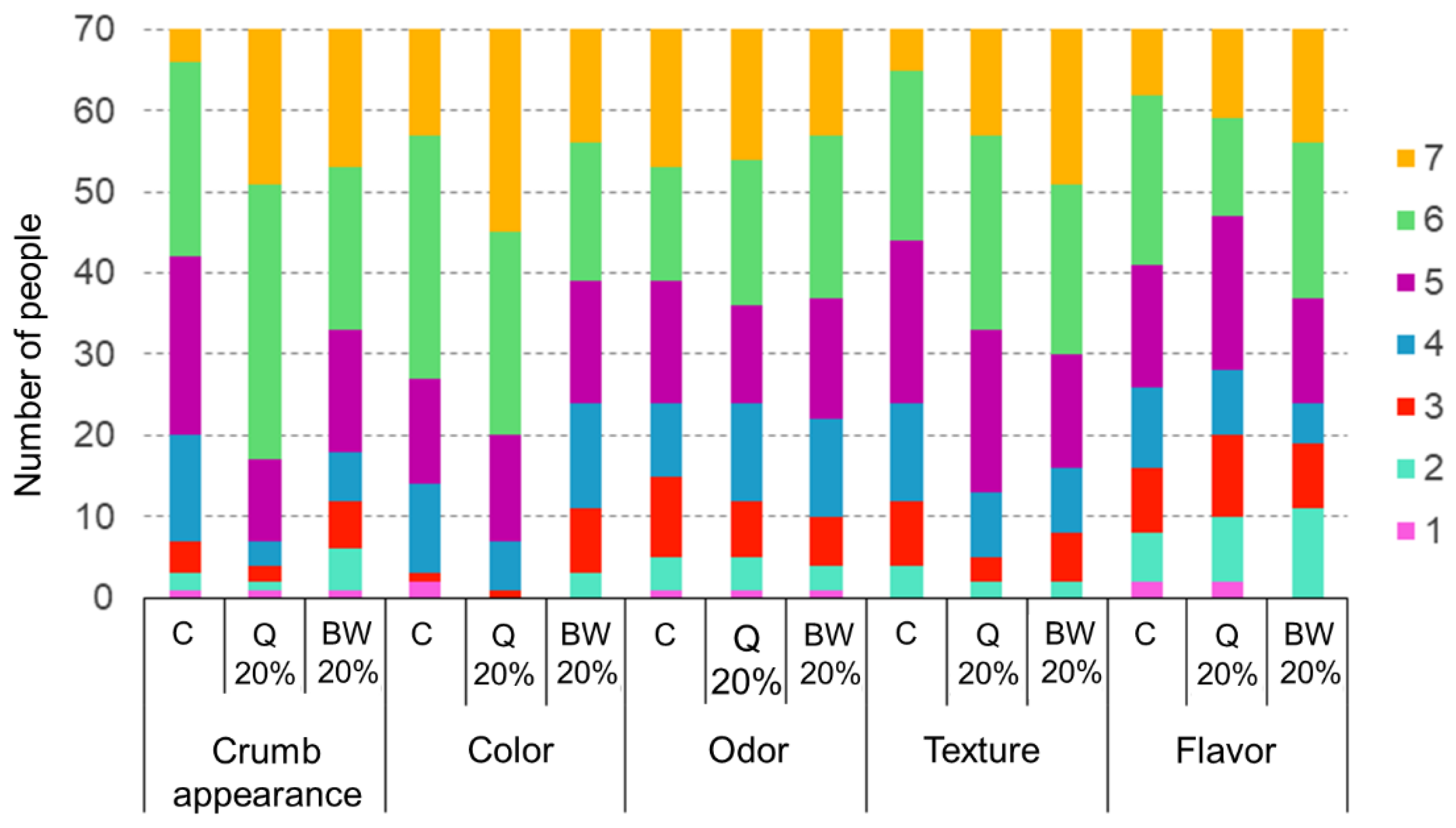

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Peñas, E.; Hernández-Ledesma, B. Pseudocereal grains: Nutritional value, health benefits and current applications for the development of gluten-free foods. Food Chem Toxicol 2020, 137, 111178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziano, S.; Agrimonti, C.; Marmiroli, N.; Gullì, M. Utilisation and limitations of pseudocereals (quinoa, amaranth, and buckwheat) in food production: A review. Trends Food Sci Technol 2022, 125, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.M.; Matanguihan, J.B.; Fuentes, F.F.; Gómez-Pando, L.R.; Jellen, E.N.; Maughan, P.J.; Jarvis, D.E. Quinoa breeding and genomics. Plant Breed Rev 2018, 42, 257–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, H.V.; Shang, X.; Jones, M.K. Buckwheat: a crop from outside the major Chinese domestication centres? A review of the archaeobotanical, palynological and genetic evidence. Veg Hist Archaeobot 2018, 27, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAO. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2025.

- Wijerathna-Yapa, A.; Pathirana, R. Sustainable agro-food systems for addressing climate change and food security. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asri, N.; Rostami-Nejad, M.; Anderson, R.P.; Rostami, K. The gluten gene: unlocking the understanding of gluten sensitivity and intolerance. Appl Clin Genet 2021, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Van Kerrebroeck, S.; Harth, H.; Huys, G.; Daniel, H.M.; Weckx, S. Microbial ecology of sourdough fermentations: diverse or uniform? Food Microbiol 2014, 37, 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, A.; Álvarez, A.; González, L.; Fernández, D.; Tornadijo, M. Effect of fermentation on microbiological, physicochemical and physical characteristics of sourdough and impact of its use on bread quality. Czech J Food Sci 2017, 35(6), 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, N.; Arendt, E.; Gallagher, E. State of the art in gluten-free research. J Food Sci 2014, 79(6), R1067–R1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciarini, L.; Ribotta, P.; León, A.; Pérez, G. Incorporation of several additives into gluten free breads: Effect on dough properties and bread quality. J Food Eng 2012, 111, 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Martinez, L.; Oliat–Ros, G.; Valerio Alfaro, C.; Lee, K.; Garcia, H. Antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and anthocyanins content of eighteen strains of Mexican maize. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2009, 42, 1187–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26: 1231-1237.

- Pulido, R.; Bravo, L.; Saura-Calixto, F. Antioxidant activity of dietary polyphenols as determined by a modified ferric reducing/antioxidant power assay. J Agric Food Chem 2000, 48(8), 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, P.; Petersen, D.; Dambmann, C. Improved method for determining food protein degree of hydrolysis. J Food Sci 2001, 66(5): 642-646.

- Reichwald, K.; Hatzack, F. Application of a modified Haug and Lantzsch method for rapid and accurate photometrical phytate determination in soybean, wheat, and maize meals. J Agric Food Chem 2008, 56, 2888–2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizo, S, de LeBlanc, A.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Rollán, G. Quinoa pasta fermented with lactic acid bacteria prevents nutritional deficiencies in mice. Food Res Int 2020, 127, 108735.

- Moroni, A.V.; Arendt, E.K.; Dal Bello, F. Biodiversity of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in spontaneously-fermented buckwheat and teff sourdoughs. Food Microbiol 2011, 28(3), 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamothe, L.M.; Srichuwong, S.; Reuhs, B.L.; Hamaker, B.R. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa W) and amaranth (Amaranthus caudatus L) provide dietary fibres high in pectic substances and xyloglucans. Food Chem 2015, 167, 490–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, X.J.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Ai, Z.; Suo, B. Diversity of bacterial communities in traditional sourdough derived from three terrain conditions (mountain, plain and basin) in Henan Province, China. Food Res Int 2020, 133, 109139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Anaya, M.A.; de Barber, C.B.; Esteve, C.C. Effect of processing conditions on acidification properties of wheat sour doughs. Int J Food Microbiol 1994, 22(4), 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lancetti, R.; Salvucci, E.; Moiraghi, M.; Pérez, G.T.; Sciarini, L.S. Gluten-free flour fermented with autochthonous starters for sourdough production: Effect of the fermentation process. Food Biosci 2022, 47, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochetti, G.; Miragoli, F.; Zacconi, C.; Lucini, L.; Rebecchi, A. Impact of cooking and fermentation by lactic acid bacteria on phenolic profile of quinoa and buckwheat sedes. Food Res Int 2019, 119, 886–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lao, X.; Bao, Y.; Guan, X.; Li, C. Effect of whole quinoa flour substitution on the texture and in vitro starch digestibility of wheat bread. Food Hydrocoll 2021, 119, 106840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Ramón, F.; Alvarez, H.; Sotelo-Méndez, A.; Norabuena, E.; Sumarriva Bustinza, L. Calidad nutricional, evaluación física, sensorial y biológica en panes convencionales y libres de gluten. Nutricion Clínica Dietetica Hospitalaria 2022, 42(1), 106-114.

- Yu, L.; Nanguet, A.; Beta, T. Comparison of antioxidant properties of refined and whole wheat flour and bread. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gélinas, P.; McKinnon, C. Effect of wheat variety, farming site, and bread-baking on total phenolics. Int J Food Sci Technol 2006, 41, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcourt-García, M.M.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Dueñas, M. Determination of phenolic composition in ancestral grains for food use. comparison of analytical methods and antioxidant activity. FarmaJournal 2020, 5(2), 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, L.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Guo, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, L.; Qin, P. Integrative analysis of the metabolome and transcriptome provides insights into the mechanisms of flavonoid biosynthesis in quinoa seeds at different developmental stages. Metabolites 2022, 12(10), 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, L.; Sekwati-Monang, B.; Lutz, D.L.; Schieber, A.; Gänzle, M.G. Phenolic acids and flavonoids in nonfermented and fermented red sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench). J Agric Food Chem 2010, 58(16), 9214-9220.

- Guo, N.; Zhu, Y.W.; Jiang, Y.W.; Li, H.K.; Liu, Z.M.; Wang, W.; Chan, C.H.; Fu, Y.J. Improvement of flavonoid aglycone and biological activity of mulberry leaves by solid-state fermentation. Ind Crops Prod 2020, 148, 112287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, B.C., Choi, W.C., Park, S., Kim, Y. O., Oh, T. K. Biochemical properties and substrate specificities of alkaline and histidine acid phytases. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2004, 63(4), 362-372.

- Rizzello, C.; Nionelli, L.; Coda, R.; Gobbetti, M. Effect of sourdough fermentation on stabilization, and chemical and nutritional characteristics of wheat germ. Food Chem 2016, 119(3), 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cera, S.; Tuccillo, F.; Knaapila, A.; Sim, F.; Manngård, J.; Niklander, K.; Verni, M.; Rizzello, C. G.; Katina, K.; Coda, R. Role of tailored sourdough fermentation in the flavor of wholegrain-oat bread. Curr Res Food Sci 2024, 8, 100697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagelaviciute, J.; Cizeikiene, D. The influence of non-traditional sourdough made with quinoa, hemp and chia flour on the characteristics of gluten-free maize/rice bread. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2021, 137, 110457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olojede, A. O.; Sanni, A.I.; Banwo, K. Effect of legume addition on the physiochemical and sensorial attributes of sorghum-based sourdough bread. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2020, 118, 108769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, E.; Ryan, L.; Dal Bello, F. Impact of sourdough on the texture of bread. Food Microbiol 2007, 24, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, D.; Schonlechner, R. Innovative approaches towards improved gluten-free bread properties. J Cereal Sci 2020, 91, 102–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsi, P.; Kosma, I.; Michauledou, S.; Argiriou, A.; Kontominas, M. Characterization of artisanal spontaneous sourdough wheat bread from central Greece: Evaluation physicho-chemical, microbiological, and sensory properties and relation to conventional yeast leavened wheat bread. Foods 2021, 10, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzatti, N.; de Morais, E.C.; Steel, C.J.; Bolini, H.M.A. Sensory characterisation of gluten-free bread with addition of quinoa, amaranth flour and sweeteners as an alternative for coeliac patients. Int J Food Sci Technol 2017, 52(4), 872–879. [Google Scholar]

- Irakli, M.; Mygdalia, A.; Chatzopoulou, P.; Katsantonis, D. Impact of the combination of sourdough fermentation and hop extract addition on baking properties, antioxidant capacity and phenolics bioaccessibility of rice bran-enhanced bread. Food Chem 2019, 285, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

TPC (mg GAE/100 mg) |

FRAP (µmol TE/g) |

ABTS (mmol TE/g) |

Phytic acid(g/100g) | µmol serine/g protein | ||

| Sourdough | Q-UnF | 52.55±0.51a | 80.53±0.56a | 1.56±0.03a | 2.06±0.05b | 0.89±0.14a |

| Q-F | 152.42±0.96b | 104.74±0.35b | 4.90±0.08b | 1.16±0.16a | 1.80±0.00b | |

| Bread | C | 90.58±0.61c | 69.33±0.05a | 2.97±0.05b | 1.77±0.02c | 0.78±0.02a |

| ChA | 84.55±1.16b | 69.88±2.84a | 2.23±0.03a | 1.84±0.00c | 0.83±0.03a | |

| Q-C | 68.24±0.09a | 97.06±0.32b | 3.12±0.071b | 1.78±0.02c | 1.09±0.01b | |

| Q-10 | 107.29±0.25d | 140.98±0.01c | 4.56±0.28c | 1.32±0.07ab | 2.28±0.13c | |

| Q-15 | 106.83±1.19d | 150.57±2.03d | 5.57±0.08d | 1.37±0.07b | 2.58±0.04d | |

| Q-20 | 113.12±0.43e | 155.52±0.98e | 5.95±0.06e | 1.21±0.07a | 2.98±0.08e | |

| Sourdough | BW-UnF | 164.65±0.13a | 120.34±0.96a | 3.92±0.10a | 2.24±0.01b | 0.99±0.05a |

| BW-F | 203.90±1.41b | 174.59±0.45b | 9.06±0.45b | 1.39±0.05a | 1.36±0.01b | |

| Bread | C | 90.58±0.61b | 69.33±0.05a | 2.97±0.05b | 1.77±0.02b | 0.78±0.02a |

| ChA | 84.55±1.16a | 69.88±2.84a | 2.23±0.03a | 1.84±0.00b | 0.83±0.03a | |

| BW-C | 138.23±0.73c | 107.04±0.77b | 5.72±0.02c | 1.81±0.01b | 1.19±0.01b | |

| BW-10 | 213.56±059d | 158.22±0.02c | 9.99±0.23d | 1.21±0.04a | 1.96±0.02c | |

| BW-15 | 224.33±1.02e | 183.38±0.34d | 11.167±0.67e | 1.21±0.03a | 2.12±0.04d | |

| BW-20 | 233.72±1.25f | 188.38±1.62e | 13.70±0.00f | 1.19±0.09a | 2.33±0.06e |

| Phenolic compound | Family | ug/g | |||||||||

| Sourdough | Bread | ||||||||||

| Q-UnF | Q-F | BW-UnF | BW-F | C | Q-C | Q-20 | BW-C | BW-20 | |||

| p-coumaric acid | Hydroxycinnamic acid | 1.23±0.05 | 2.99±0.69 | 0.73±0.01 | 5.63±0.35 | 2.15±0.15 | 1.49±0.71 | 1.91±0.67 | 2.23±0.13 | 1.95±0.72 | |

| Gallic acid | Hydroxybenzoic acid | nd | nd | 3.71±0.05 | 11.39±0.16 | 1.10±0.12 | 1.48±0.68 | 2.59±2.16 | 2.82±0.35 | 1.78±0.78 | |

| Catechin | Flavanol | nd | nd | 15.48±0.84 | 52.65±3.29 | 3.33±0.37 | 1.02±0.14 | 3.74±3.43 | 5.28±0.12 | 3.13±2.49 | |

| Epicatechin | Flavanol | nd | nd | 9.69±0.06 | 13.08±0.44 | 0.76±0.03 | 0.43±0.28 | 0.58±0.41 | 2.35±0.05 | 1.70±0.46 | |

| Epicatechin gallate | Flavanol | nd | nd | 0.57±0.00 | 0.11±0.01 | 0.03±0.00 | nd | nd | 0.11±0.04 | 0.09±0.01 | |

| Epicatechin O-dimethylgallate | Flavanol | nd | nd | 0.55±0.08 | 0.44±0.03 | 0.02±0.03 | nd | nd | 0.09±0.03 | 0.07±0.00 | |

| Quercetin | Flavonol | 1.76±0.14 | 5.41±1.09 | 10.07±2.61 | 213.20±49.17 | 5.37±0.32 | 5.34±0.27 | 6.56±1.06 | 21.70±9.16 | 20.12±1.91 | |

| Quercetin glucuronide | Flavonol | 6.12±0.22 | 0.57±0.06 | nd | nd | 1.04±0.03 | 1.61±0.89 | 1.04±0.35 | 4.06±0.01 | 2.28±0.52 | |

| Quercetin rhamnoside | Flavonol | nd | nd | 2.27±0.14 | 2.45±0.06 | 0.25±0.05 | 0.19±0.03 | 0.35±0.10 | 0.91±0.04 | 0.71±0.27 | |

| Isoquercetin | Flavonol | 2.51±0.01 | 0.09±0.03 | 51.93±5.89 | 21.98±0.99 | 5.92±0.21 | 4.09±0.69 | 5.35±1.99 | 26.28±0.79 | 18.21±4.07 | |

| Quercetin apiofuranoside | Flavonol | 9.99±0.17 | 3.29±0.91 | nd | nd | 1.84±0.10 | 1.89±1.22 | 1.74±0.78 | 4.34±0.32 | 2.81±0.63 | |

| Kaempferol glucoside | Flavonol | 0.09±0.00 | 0.05±0.02 | 7.27±0.20 | 2.35±0.00 | 0.04±0.01 | 0.33±0.08 | 0.39±0.13 | 1.51±0.11 | 1.07±0.33 | |

| Rutin | Flavonol | 3.48±0.09 | 7.05±1.79 | 53.39±0.66 | 5.74±0.63 | 1.19±0.04 | 4.32±1.49 | 5.03±2.55 | 18.14±1.88 | 13.42±3.98 | |

| Mauritanian | Flavonol | 0.99±0.02 | 1.09±0.16 | nd | nd | 0.94±0.04 | 0.66±0.29 | 0.79±0.29 | 1.19±0.11 | 1.23±0.19 | |

| SBV (cm3/g) |

Initial firmness (N) |

Firming rate (N/day) |

Pores/mm2 | Total air area (%) | Pore average size (mm2) | |

| C | 1.9370.018a | 13.63±1.18f | 5,00 | 0.390±0.014ab | 41.59±5.91a | 0.593±0.045a |

| ChA | 2.116±0.011b | 11.96±0.76e | 5.06 | 0.383±0.005a | 40.43±1.92a | 0.533±0.006a |

| Q-C | 2.169±0.014b | 10.80±0.71d | 4.65 | 0.415±0.010bcd | 47.76±1.24b | 0.585±0.033a |

| Q-10 | 2.463±0.028c | 7.12±0.25b | 4.35 | 0.415±0.013bcd | 50.93±4.60bc | 0.887±0.085b |

| Q-15 | 2.542±0.062d | 4.67±0.85a | 3.96 | 0.403±0.025abc | 55.16±3.12cd | 0.958±0.029b |

| Q-20 | 2.712±0.054e | 4.58±0.28a | 2.95 | 0.508±0.010ef | 61.83±3.49e | 1.075±0.013c |

| BW-C | 2.171±0.046b | 12.23±0.56e | 4.64 | 0.433±0.015d | 47.73±1.55b | 0.608±0.022a |

| BW-10 | 2.273±0.037c | 8.58±0.39c | 4.54 | 0.428±0.021cd | 61.31±3.89e | 1.070±0.104c |

| BW-15 | 2.259±0.041c | 7.49±0.60b | 4.04 | 0.485±0.010e | 57.98±3.42de | 0.893±0.039b |

| BW-20 | 2.417±0.045d | 7.22±0.13b | 2.74 | 0.515±0.038f | 60.72±3.07e | 0.913±0.047b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).