Submitted:

11 October 2025

Posted:

15 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Evolution of the Urban–Rural Digital Divide: From Material Exclusion to Cognitive Transformation

2.2. Digital Literacy and Information Perception: A Technological–Cognitive Mediating Chain

2.3. The Moderating Role of University Resources: Institutional Compensation and Substitution Pathways

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Source

3.2. Variable Specification

- Dependent Variables

- 2.

- Core Independent Variable

- 3.

- Mediating Variables

- 4.

- Moderating Variable

- 5.

- Control Variables

3.3. Analytical Strategy

4. Empirical Results

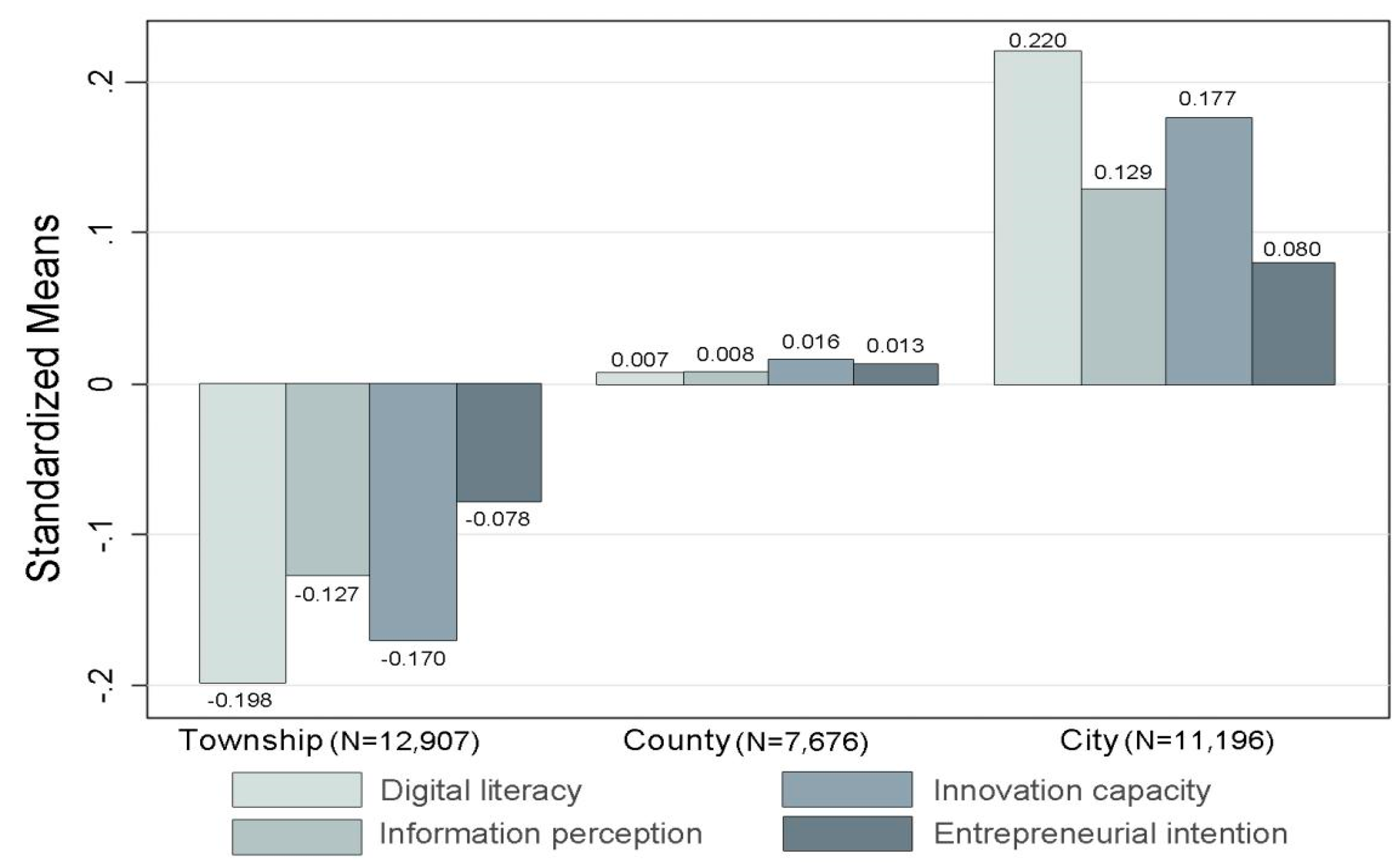

4.1. Main Effects of Urban–Rural Disparities

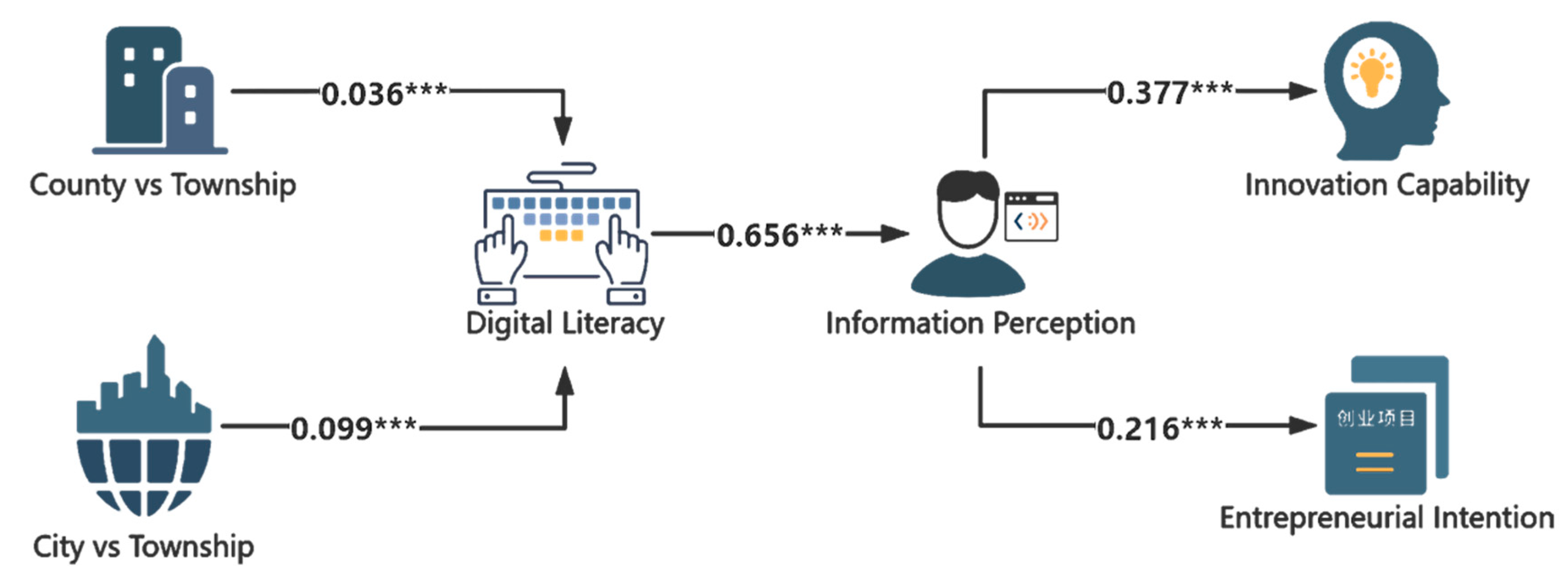

4.2. Mediation Analysis: The Sequential Role of Digital Literacy and Information Perception

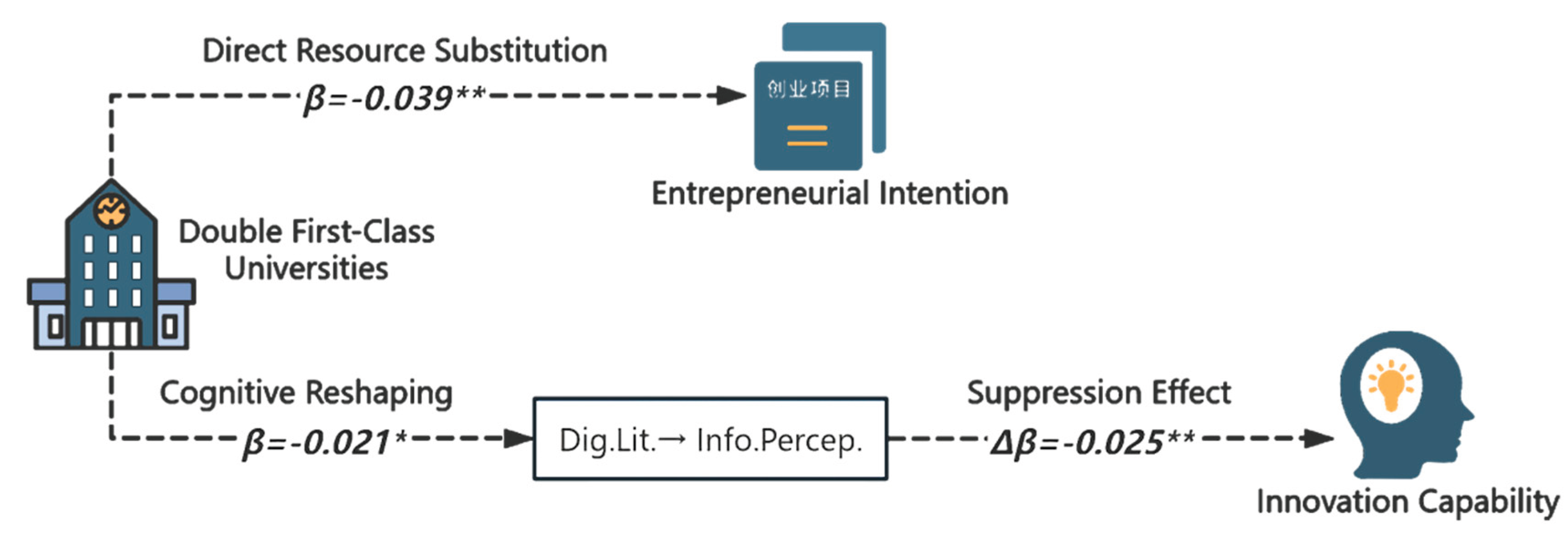

4.3. Moderating Boundaries of University Type and Multilevel Empowerment Mechanisms

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Research Findings and Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Policy Implications and Research Directions

References

- CAICT. 2024 Research Report on the Development of China’s Digital Economy (2024) Available online:. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/english/research/whitepapers/202411/t20241129_645879.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Wang, C. Report-Based Interpretation of 2024 Digital Literacy and Skills in China and the EU: Status, Differences, and Future Directions. In New Media Pedagogy: Research Trends, Methodological Challenges, and Successful Implementations; Tomczyk, Ł., Ed.; Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; Vol. 2537, pp. 3–18; ISBN 978-3-031-95626-3. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, L.; Cotten, S.R.; Ono, H.; Quan-Haase, A.; Mesch, G.; Chen, W.; Schulz, J.; Hale, T.M.; Stern, M.J. Digital Inequalities and Why They Matter. Information, Communication & Society 2015, 18, 569–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Digital Entrepreneurship: Toward a Digital Technology Perspective of Entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 2017, 41, 1029–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnedda, M. The Third Digital Divide: A Weberian Approach to Digital Inequalities; Routledge: London, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-60600-2. [Google Scholar]

- Assefa, Y.; Gebremeskel, M.M.; Moges, B.T.; Tilwani, S.A.; Azmera, Y.A. Rethinking the Digital Divide and Associated Educational in(Equity) in Higher Education in the Context of Developing Countries: The Social Justice Perspective. IJILT 2025, 42, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2020). The digital divide. Polity Press.

- Hargittai, E. Digital Na(t)Ives? Variation in Internet Skills and Uses among Members of the “Net Generation.” Sociological Inquiry 2010, 80, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAICT. 2023 White Paper on Broadband Development in China (2023) Available online:. Available online: http://www.caict.ac.cn/english/research/whitepapers/202404/t20240430_476667.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Castells, M. (1996). The rise of the network society. Blackwell Publishers.

- Marginson, S. The Worldwide Trend to High Participation Higher Education: Dynamics of Social Stratification in Inclusive Systems. High Educ 2016, 72, 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, K. (1990). Capital: A critique of political economy (Vol. 1; B. Fowkes, Trans.). Penguin Books. (Original work published 1867).

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology (G. Roth & C. Wittich, Eds.). University of California Press. (Original work published 1922).

- Wing Chan, K.; Buckingham, W. Is China Abolishing the Hukou System? The China Quarterly 2008, 195, 582–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y. The Prevalence and the Increasing Significance of Guanxi. The China Quarterly 2018, 235, 597–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deursen, A.J.; Van Dijk, J.A. The First-Level Digital Divide Shifts from Inequalities in Physical Access to Inequalities in Material Access. New Media & Society 2019, 21, 354–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. The Household Registration System and Rural-Urban Educational Inequality in Contemporary China. Chinese Sociological Review 2011, 44, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. Second-Level Digital Divide: Differences in People’s Online Skills. First Monday 2002. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Chen, J. Can China’s Higher Education Expansion Reduce the Educational Inequality Between Urban and Rural Areas? The Journal of Higher Education 2023, 94, 638–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargittai, E. Potential Biases in Big Data: Omitted Voices on Social Media. Social Science Computer Review 2020, 38, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues-Silva, J.; Alsina, Á. STEM/STEAM in Early Childhood Education for Sustainability (ECEfS): A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katharina Fellnhofer Toward a Taxonomy of Entrepreneurship Education Research Literature: A Bibliometric Mapping and Visualization. Educational Research Review 2019, 27, 28–55. [CrossRef]

- Scheerder, A.; van Deursen, A.; van Dijk, J. Determinants of Internet Skills, Uses and Outcomes. A Systematic Review of the Second- and Third-Level Digital Divide. Telematics and Informatics 2017, 34, 1607–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Laar, E.; van Deursen, A.J.A.M.; van Dijk, J.A.G.M.; de Haan, J. The Relation between 21st-Century Skills and Digital Skills: A Systematic Literature Review. Computers in Human Behavior 2017, 72, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W. A Study of the Impact of the New Digital Divide on the ICT Competences of Rural and Urban Secondary School Teachers in China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Han, R.; Wang, L.; Lin, R. Social Capital in China: A Systematic Literature Review. Asian Bus Manage 2021, 20, 32–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dane, E. Reconsidering the Trade-off Between Expertise and Flexibility: A Cognitive Entrenchment Perspective. AMR 2010, 35, 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, K.G.; Houston, S.M.; Brito, N.H. Family Income, Parental Education and Brain Structure in Children and Adolescents. Nat Neurosci 2015, 18, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Fagerstrøm, A.; Sigurdsson, V.; Arntzen, E. Analyzing Motivating Functions of Consumer Behavior: Evidence from Attention and Neural Responses to Choices and Consumption. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1053528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autio, E.; Nambisan, S.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Wright, M. Digital Affordances, Spatial Affordances, and the Genesis of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship 2018, 12, 72–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Wright, M.; Feldman, M. The Digital Transformation of Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Progress, Challenges and Key Themes. Research Policy 2019, 48, 103773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, G.; Merrill, R.K.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. Digital Sustainability and Entrepreneurship: How Digital Innovations Are Helping Tackle Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 2021, 45, 999–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Belitski, M.; Caiazza, R.; Günther, C.; Menter, M. From Latent to Emergent Entrepreneurship: The Importance of Context. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 175, 121356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, T.; Zhou, H.; Sun, Q. Ushering in Industrial Forces for Teaching-Focused University-Industry Collaboration in China: A Resource-Dependence Perspective. Studies in Higher Education 2024, 49, 2357–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, A.-F.; Murphy, L.; Thomas, B. University Knowledge Transfer and Innovation Performance in Firms: The Ghanaian Experience. Int. J. Innov. Mgt. 2020, 24, 2050023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Jiang, R.; Feng, C.; Li, D. How Does R&D Collaboration Shape the Patent Quality of Universities? J Technol Transf 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bapna, S. Complementarity of Signals in Early-Stage Equity Investment Decisions: Evidence from a Randomized Field Experiment. Management Science 2019, 65, 933–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In J. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education (pp. 241-258). Greenwood Press.

- Liñán, F.; Fayolle, A. A Systematic Literature Review on Entrepreneurial Intentions: Citation, Thematic Analyses, and Research Agenda. Int Entrep Manag J 2015, 11, 907–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D.A.; Kaniskan, B.; McCoach, D.B. The Performance of RMSEA in Models With Small Degrees of Freedom. Sociological Methods & Research 2015, 44, 486–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.-T.; Wen, Z. In Search of Golden Rules: Comment on Hypothesis-Testing Approaches to Setting Cutoff Values for Fit Indexes and Dangers in Overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) Findings. Structural Equation Modeling 2004. [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, J. R. , & Molotch, H. L. (1987). Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. University of California Press.

- Ridgeway, C. L. Framed by Gender: How Gender Inequality Persists in the Modern World | Oxford Academic Available online:. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/book/9175 (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.E. The Pervasive Effects of Family on Entrepreneurship: Toward a Family Embeddedness Perspective. Journal of Business Venturing 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimension | Measurement Items |

|---|---|

| Value evaluation efficacy | The current forms and methods of innovation and entrepreneurship education can stimulate our enthusiasm to participate. |

| Environmental parsing ability | National entrepreneurship policies provide tangible support for students to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Our university attaches great importance to entrepreneurship education and actively encourages students to participate. |

| Institutional cognition validity | Our university actively implements entrepreneurship support policies introduced by governments at various levels. |

| Variable | Operational Definition | Statistics |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||

| Innovation capacity(Innov. Cap.) | Continuous variable; creative thinking (7 items) + creative personality (9 items), 4-point scale | Standardized factor scores, range [-3.48, 1.58] |

| Entrepreneurial intention (Entr. Intent.) |

Continuous variable; 4 items from EISU scale, 7-point scale | Standardized factor scores, range [-2.03, 1.57] |

| Core Independent Variable | ||

| Urban–rural classification | Township: family permanent residence = rural/township (reference group) | 40.6% (n = 12,907) |

| County: family permanent residence = county-level administrative unit | 24.1%(n=7,676) | |

| Urban: family permanent residence = prefecture-level or above | 35.2%(n=11,196) | |

| Mediating Variables | ||

| Digital literacy(Dig.Lit.) | Continuous variable; 9 items from CSLAiI scale, 5-point scale | Standardized factor scores, range [-3.23, 1.47] |

| Information perception (Info.Percep.) |

Continuous variable; 4 items across three dimensions, 5-point scale | Standardized factor scores, range [-3.20, 1.38] |

| Moderating Variable | ||

| University type | Double First-Class = 1; non-Double First-Class = 0 | 22.7%(n=7,202) |

| Control Variables | ||

| Gender | Male = 1, Female = 0(reference) | 47.0%(n=14,929) |

| Political affiliation | Communist Party member = 1, otherwise = 0(reference) | 5.4%(n=1,728) |

| Leadership experience | Yes = 1, No = 0(reference) | 54.4%(n=18,041) |

| Grade level | Ordered variable, 1 (freshman) – 6 (PhD) | M=2.181, SD=1.150 |

| Academic performance | Ordered variable, 1 (top 10%) – 5 (bottom 25%) | M=2.436, SD=1.128 |

| Family socioeconomic status | Continuous variable; self-reported 10-point scale | M=4.127, SD=1.650 |

| Family cultural capital | Continuous variable; parental years of education | Standardized factor scores, range [-3.23, 2.62] |

| Family entrepreneurial atmosphere | Relatives in entrepreneurship = 1; otherwise = 0(reference) | 48.3%(n=15,346) |

| Variable | CFA Indicators | Model Fit Indices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std | SMC | CR | AVE | Cronbach's α | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

| Innov. Cap. | 0.764-0.872 | 0.584-0.760 | 0.973 | 0.697 | 0.973 | 0.930 | 0.919 | 0.106 | 0.031 |

| Entr. Intent. | 0.807-0.957 | 0.651-0.916 | 0.936 | 0.785 | 0.934 | 0.998 | 0.994 | 0.063 | 0.005 |

| Dig.Lit. | 0.888-0.936 | 0.789-0.876 | 0.978 | 0.831 | 0.978 | 0.943 | 0.925 | 0.165 | 0.025 |

| Info.Percep. | 0.600-0.955 | 0.359-0.912 | 0.908 | 0.671 | 0.931 | 0.998 | 0.994 | 0.062 | 0.006 |

| Variable | Urban vs.Township | County vs.Township | Urban vs. County |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dig.Lit. | 0.428 | 0.211 | 0.219 |

| Info.Percep. | 0.262 | 0.139 | 0.125 |

| Innov. Cap. | 0.350 | 0.188 | 0.165 |

| Entr. Intent. | 0.157 | 0.091 | 0.067 |

| Innovation capacity | Entrepreneurial intention | |

|---|---|---|

| Urban–rural classification | ||

| County vs. Township | 0.071***(0.014) | 0.018(0.015) |

| Urban vs. Township | 0.149***(0.014) | 0.044**(0.014) |

| Individual characteristics | ||

| Gender | 0.073***(0.011) | 0.166***(0.011) |

| Political affiliation | 0.098***(0.026) | 0.022(0.026) |

| Leadership experience | 0.100***(0.011) | 0.090***(0.011) |

| Grade level | -0.039***(0.005) | -0.070***(0.005) |

| Academic performance | -0.112***(0.005) | -0.075***(0.005) |

| Family capital | ||

| Family socioeconomic status | 0.062***(0.003) | 0.044***(0.004) |

| Family cultural capital | 0.086***(0.006) | 0.024***(0.006) |

| Family entrepreneurial atmosphere | 0.087***(0.011) | 0.182***(0.011) |

| Intercept | -0.095**(0.032) | -0.113(0.066) |

| Wald χ² | 2592.60*** | 1659.15*** |

| Path and Effect | Standardized Coefficient (SE) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Main pathways | ||

| County vs. Township → Dig.Lit. | 0.036*** (0.006) | [0.024, 0.048] |

| Urban vs. Township → Dig.Lit. | 0.099*** (0.007) | [0.085, 0.113] |

| Dig.Lit. →Info.Percep. | 0.656*** (0.005) | [0.646, 0.666] |

| Info.Percep. → Innov. Cap. | 0.377*** (0.008) | [0.362, 0.392] |

| Info.Percep. → Entr. Intent. | 0.216*** (0.008) | [0.200, 0.232] |

| Mediating pathways | ||

| County → Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Innov. Cap. | 0.009*** (0.002) | [0.012, 0.059] |

| Urban → Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Innov. Cap. | 0.024*** (0.002) | [0.021, 0.028] |

| County → Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Entr. Intent. | 0.005*** (0.001) | [0.003, 0.007] |

| Urban → Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Entr. Intent. | 0.014*** (0.001) | [0.012, 0.016] |

| Total effects | ||

| County → Innov. Cap. | 0.030*** (0.004) | [0.022, 0.038] |

| Urban → Innov. Cap. | 0.072*** (0.004) | [0.064, 0.080] |

| County → Entr. Intent. | 0.006*** (0.002) | [0.003, 0.009] |

| Urban → Entr. Intent. | 0.017*** (0.002) | [0.013, 0.021] |

| Variables and Effects | Innovation capacity | Entrepreneurial intention |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | ||

| Dig.Lit. | 0.534*** (0.009) | 0.304*** (0.012) |

| Double First-Class university(DFC) | 0.026 (0.038) | -0.030 (0.029) |

| DFC × Dig.Lit. | 0.010 (0.012) | -0.039** (0.016) |

| Test of moderation | χ² =0.67 (p=0.414) | χ² =5.65* (p=0.017) |

| Marginal effects | ||

| Non-DFC | 0.534*** (0.009) | 0.304*** (0.012) |

| DFC | 0.544*** (0.009) | 0.265*** (0.012) |

| Random effects | ||

| Variance across universities | 0.005*** (0.002) | 0.019 ***(0.005) |

| Model fit | Log-likelihood= -38,261.38 | Log-likelihood= -42,650.18 |

| Wald χ² =188,078.02*** | Wald χ² =27,653.18*** |

| Path and Moderating Effect | Standardized Coefficient (SE) | Moderating Effect Δβ (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Main pathway | ||

| Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. | 0.620***(0.009) | |

| Moderating pathway | ||

| DFC moderation (Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep.) | -0.021*(0.009) | |

| Suppression of mediating pathways | ||

| Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Innov. Cap. | -0.025**(0.009) | |

| Dig.Lit. → Info.Percep. → Entr. Intent. | 0.002(0.011) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).