1. Introduction

Efforts have been made to address the intensifying climate crisis caused by global warming resulting from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The construction sector accounts for approximately 37% of the total GHG emissions from all industries; therefore, urgent intervention is required to reduce GHG emissions in this sector [

1]. South Korea is one of the countries contributing in reducing GHG emissions. Korea has declared carbon neutrality by 2050 and expects 40% of its total GHG emissions to be reduced as outlined in the Nationally Determined Contributions by 2030. Approximately 32.8% of these emissions is expected to be reduced from the building sector [

2,

3].

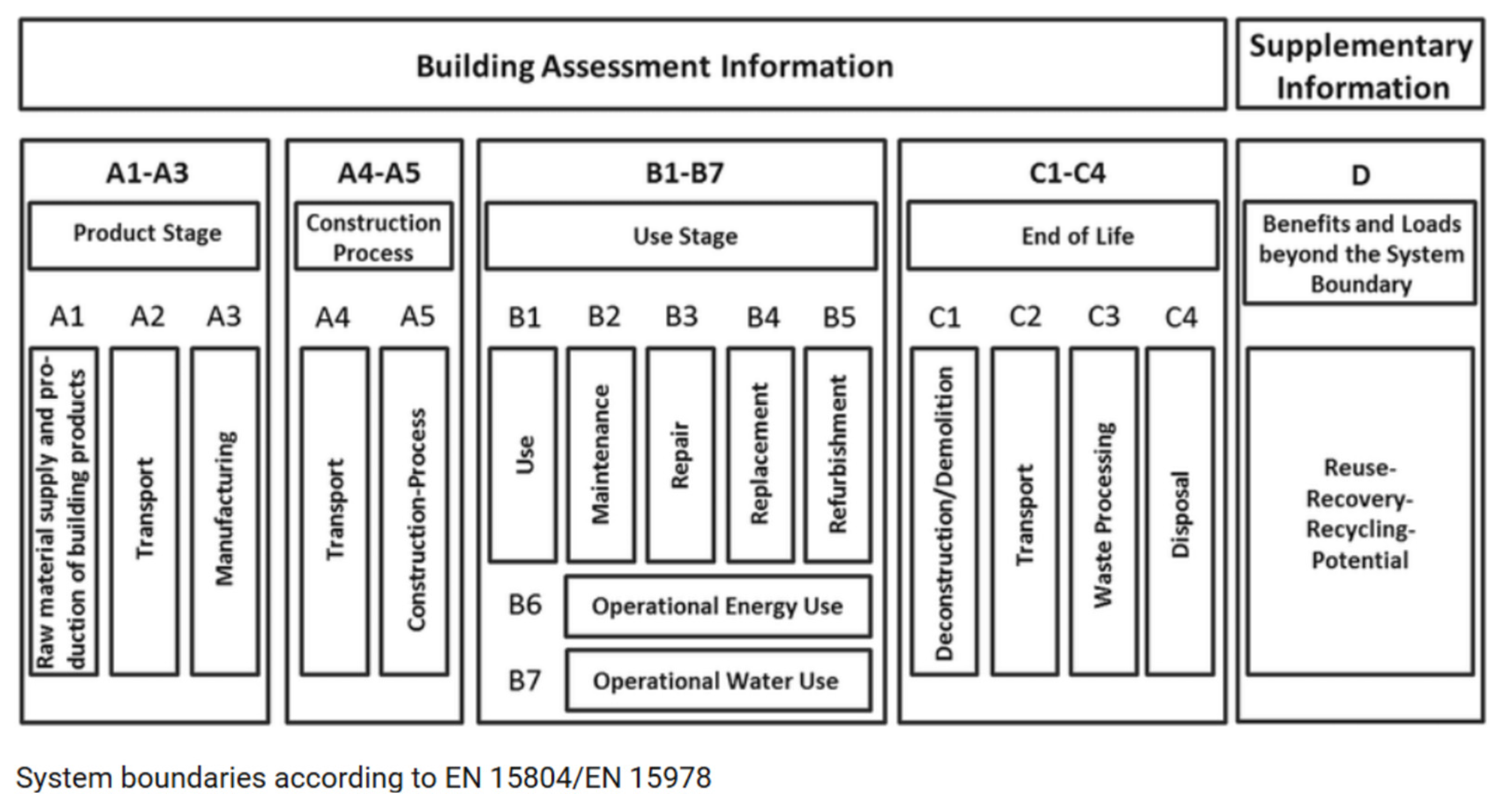

Considering the goal for carbon neutrality in the building sector, EN15804 was enacted by the European Committee for Standardization for objectively evaluating the life cycle environmental impacts of building materials. It is one of the key strategies for reducing carbon emissions and has been utilized as an international standard.

The EN15804 is the most widely used global reporting standard specializing ISO14025 in the field of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs Type III) in the construction industry. As shown in

Figure 1, it stipulates GHG emissions from the life cycle, which involves the production of materials (A1–A3), transport and construction (A4 and A5), use (B1–B7), dismantling and disposal (C1–C4), and outside the system boundary (Module D), and various environmental impacts by module [

4,

5,

6]. Based on this, architects and designers can select materials with low carbon emissions using EPD [

7].

Examining life cycle assessment (LCA) for GHG reduction from an architectural perspective shows that, compared with the typical wet method, the modular method can reduce environmental impacts by 2% to 5% via the partial application of prefabs alone and by 20% to 50% via the application of advanced modularization. In particular, the modular method can achieve carbon emission reduction in material production via optimization and standardized mass production [

8,

9].

A comparison of the typical wet and modular methods based on small residential buildings in Korea showed that buildings that applied the latter can reduce carbon emissions in the material production stage by approximately 35% [

10]. The material production stage represents a considerable proportion of the life cycle carbon emissions of buildings. In new buildings where high-efficiency and low-energy operations are generalized, the proportion of A1–A3 in life cycle carbon emissions tends to increase to approximately 50%. The international roadmap presents initial embodied carbon reduction as a key task [

11,

12]. Marsh et al. [

13] emphasized the importance of the A1–A3 stages while quantifying uncertainty in product stage embodied carbon calculations for buildings [

13]. The LCA model of prefabricated buildings showed that the material production stage accounts for the largest proportion of total carbon emissions. Similarly, the carbon footprint analysis results for residential and commercial buildings in the United States confirmed that the material production stage exhibits the largest proportion of carbon emissions from the entire supply chain [

14,

15]. Li and Masera [

16] examined the methodology for building embodied carbon assessment from a perspective of circular economy and emphasized that the A1–A3 stages are essential in the life cycle carbon emissions of buildings [

16]. Carbon emissions in the building operation stage is expected to decrease owing to the shift in building operation to high-efficiency and low-energy systems while the proportion of emissions from the material production stage is expected to increase relatively.

Compared with other industries, the construction industry is considered a low-productivity industry. Labor-intensive construction based on on-site production increases dependency on skilled workers, and non-standardized processes have been highlighted as the main causes [

17]. The indicator of the report on labor productivity in the Korean construction industry by Seong and Yoo [

18] has declined over the last decades from 104.1 in 2011 to 94.5. This shows that the productivity of the Korean construction industry is lower than those of advanced countries in contrast with the increase in average productivity across industries during the same period. In particular, the shortage of skilled workers because of the aging of construction workers emerges as a significant issue [

18]. Because of limited workforce supply, foreign workers have been filling the gap. This workforce structure problem causes defects because of degradation in construction quality and increases risks associated with delays in the construction period. These factors could decrease the sustainability of the construction industry in the future [

19,

20]. Based on a defect analysis in Korean apartment buildings, defects in bathroom, as one of the representative factors, rank the third among all types of defects, and major defects include non-compliance with waterproofing membrane thickness, defective backfilling for tile adhesion, tile detachment, and leakage [

21,

22]. These problems can be observed overseas, and large-scale overseas surveys exhibit waterproofing and leakage as the most frequent defects, indicating that water-related bathroom processes involve high defect risks [

23].

Bathroom construction involves complex processes, as many construction tasks must be performed sequentially in a small space, thereby causing frequent interference between processes and significant challenges in construction management [

24,

25,

26]. In particular, the conventional wet construction method, a representative bathroom construction method, requires the participation of multiple skilled workers and high skill levels, causing a high defect occurrence rate because of limitations in quality control for each task and unclear liabilities for defects [

27]. Waterproofing exhibits a higher difficulty because the waterproof layer needs to be reconstructed after removing the finishing materials, requiring considerable cost, materials, energy, and time. Therefore, a novel approach is required to address the problems of low productivity and workforce aging at construction sites and improve construction quality in spaces that integrate multiple tasks, such as bathrooms.

Modular construction, one of the methods for addressing such problems, has attracted attention as an alternative for construction productivity innovation and quality improvement. Modular bathrooms are representative modular construction element technology for addressing inefficiency. A modular bathroom refers to a bathroom for which bathroom components (e.g., floor panels, walls, ceilings, plumbing, and finishing materials) are manufactured and assembled in a factory.

As for modular bathroom types, the 3D module method installs the pre-assembled one-bathroom unit at the site by lifting it using a crane. It is mainly used in Europe and Singapore and referred to as a prefabrication bathroom unit or Bathroom Pods. The 2D method assembles the materials produced in factories at the site. It is mainly used in Japan and Korea and referred to as the unit bathroom and system bath.

Unlike bathrooms that apply conventional wet construction, these modular bathrooms can be rapidly constructed through minimal assembly and connection work at the site, ensuring uniform quality through factory production while significantly reducing on-site manpower and construction period. Bathroom modularization has been introduced for decades in Europe and Japan, and modular bathrooms have been applied in apartment buildings since the mid-1990s in Singapore [

28]. In Japan, the modular bathroom known as unit bath has been applied since the 1960s, and modular bathrooms are constructed in almost every bathroom. In Korea, modular bathrooms were applied to construct large-scale accommodation facilities for hosting international sports events and new towns in the 1980s and 1990s.

In Korea, however, modular bathrooms were not widely distributed because low-cost bathroom images were fixed because of the finishing material discoloration caused by the use of low-cost plastic materials as wall panels at that time and the resonance caused by poor floor construction. These problems have been addressed, and performance has been improved through increased wall panel strength and tile finishing identical to wet bathrooms. Because previous images have not been addressed, however, modular bathrooms have been applied only in state-rented housing.

Table 1 compares the wet and modular construction methods commonly applied in bathrooms in Korea. Compared with the wet construction method, the performance of modular bathrooms in Korea has been improved through research and development to shorten the construction period, ensure quality, improve constructability, and secure the same level of finishing performance. No approach, however, has addressed the impact of environmental loads for GHG reduction.

Korea requires a paradigm shift in construction production from manpower- to system-oriented methods. As an element technology representing the transformation of the construction industry into the manufacturing industry, modularization is expected to be expanded for bathrooms, which are among the areas exhibiting the highest proportion of defects. Therefore, modular bathrooms that can reduce environmental loads while being applicable at conventional wet construction sites are necessary.

Therefore, this study aimed to develop an environmental load-reducing modular bathroom system applicable to residential buildings in Korea. We examined its effectiveness by fabricating a prototype, verified its performance, and compared carbon emissions from the wet and modular bathrooms for the material production stage. The results of this study are expected to be used as basic data for the analysis of the expected carbon emission reduction effect through the modularization of each part of construction and the transformation of the construction industry into the manufacturing industry.

2. Methodology

In this study, a bathroom was constructed using the modular construction method and its performance was verified through the mock-up test., Finishing materials as well as floor waterproof panel, wall panel, and ceiling panel materials were selected to development an environmental load-reducing modular bathroom and its basic performance verification. The details for each stage are as follows:

2.1. Overview of Material Selection and Performance Evaluation for the Modular Bathroom

2.1.1. Overview of Material Selection for the Modular Bathroom

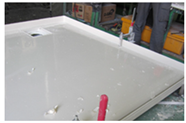

- Floor waterproof panel materials

The three floor waterproof panels, inamely sheet molding compound (SMC), fiberglass reinforced-plastics (FRP), and thermo-plastic resin (TPR), applicable in Korea were analyzed based on the production method, productivity, quality stability, manpower dependence, and construction characteristics based on suitability for the modular construction method.

- Wall panel materials

Finishing materials applicable in Korea were examined to select wall panel finishing materials, which were selected through performance verification. As presented in

Table 2, performance verification was performed for recyclable steel materials and large panel finishing materials available in Korea.

2.1.2. Overview of Material Performance Evaluation

The test method was based on the KS F 2223 (test of decorative metal plates in complex sanitary units for housing), a Korean standard. An additional performance test was conducted based on KS L 1001 (test of the chemical resistance of ceramic tiles) to ensure performance at the level of tiles, which are finishing materials for bathrooms in Korea. The criteria are presented in

Table 3.

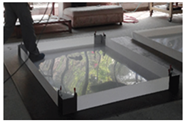

2.2. Mock-Up Test Overview

2.2.1. Basic Performance Test Overview

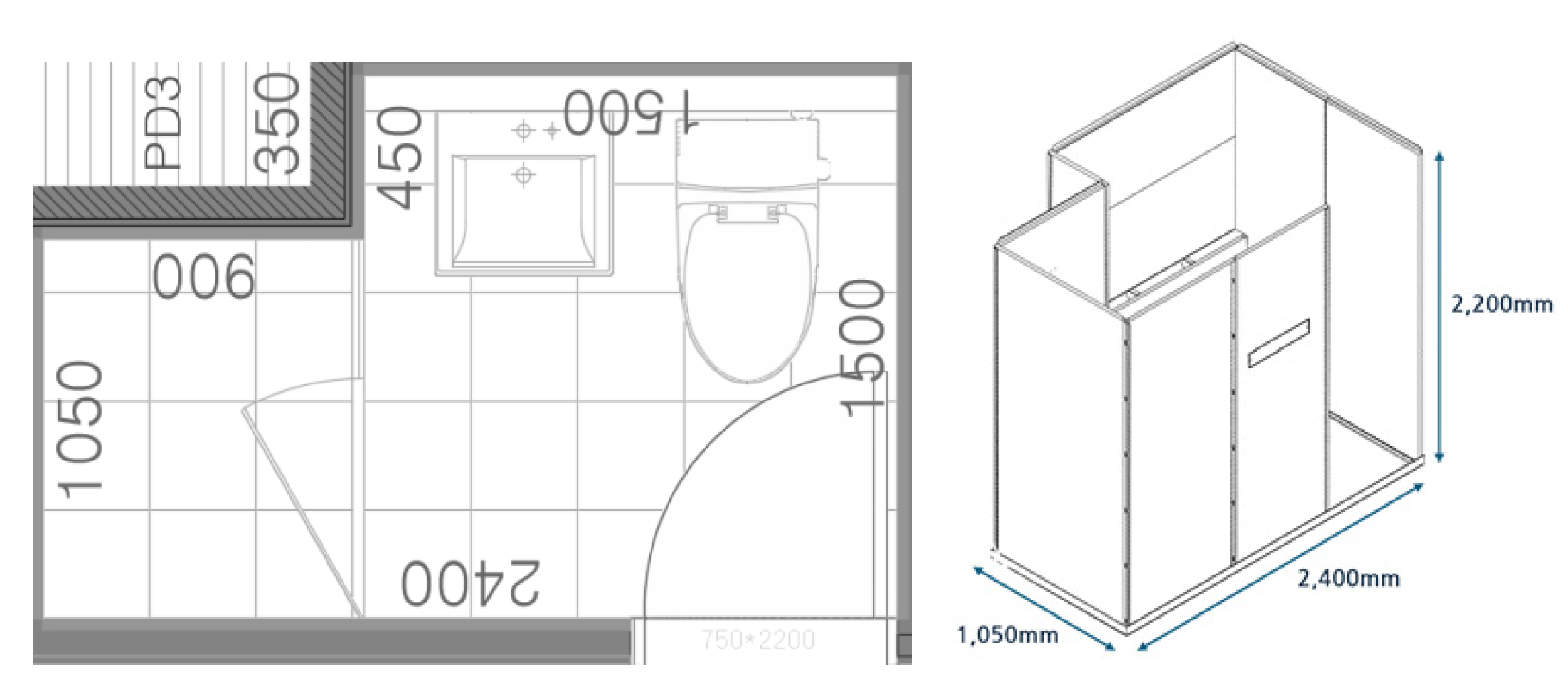

The basic performance of the bathroom system was verified by designing a prototype for mock-up test, as shown in

Figure 2. The prototype had an area of approximately 3.2 m

2 in a size of 1.5 m x 2.4 m, which is mostly applied in typical small residential bathrooms in Korea, with a ceiling height of 2.2 m. The wall panel width was designed to range from 750 to 1,050 mm, and one bathroom comprised 10 panels.

KS F 2223 (test of decorative metal plates in complex sanitary units for housing), which serves as the performance criteria of modular bathrooms in Korea, was applied. The criteria are as follows:

Table 4.

Performance test criteria for modular bathrooms.

Table 4.

Performance test criteria for modular bathrooms.

| Category |

Test method |

Criteria |

| Moisture resistance |

All |

Exposure to boiling condition for 1 h after sealing the opening |

There should be no deformation or problem that inhibits usage. |

| Deformation |

Wall panel |

Attach a rubber plate with a diameter of 150 mm and thickness of 5 mm to the center of the wall panel and apply a load of 98 N (10 kgf). |

A maximum deformation of 7 mm or less |

| Ceiling panel |

Apply a 4kg weight to the center of the ceiling and check the maximum deformation after 1 hour. |

A maximum deformation of 10 mm or less |

| Waterproof panel |

Fill 80% of the bathtub with water and place a 100-kg weight at its center. Then, check the maximum load at the bottom center after 1 h. |

A maximum deformation of 5 mm or less |

| Impact strength |

Wall panel |

After raising a 200-mm-diameter fabric bag (15 kg) to a length of 1 M and an angle of 30˚, repeat an impact five times. |

There should be no defect (e.g., deformation, damage, and crack) that inhibits usage. |

| Waterproof panel |

Drop a sandbag (7 kg) from a height of 1 M five times

(no finishing material attached) |

There should be no defect (e.g., deformation, damage, and crack) that inhibits usage. |

| Surface hardness |

Waterproof panel |

Calculate the average value by checking at least 10 positions. |

Barcol hardness of 30 or higher |

2.2.2. Field Applicability Evaluation

To evaluate the field applicability of the developed bathroom, the wet and developed bathrooms were compared through mock-up construction in the same environment as the actual wet construction. The analysis unit is one bathroom while the scope of analysis includes the construction tasks for the bathroom unit, construction period, and amount of each material used.

2.3. LCA

The products certified by the EPD of the Korea Environmental Industry and Technology Institute were applied for the LCI DB used in this study. When they were insufficient, they were supplemented using Korea LCI DB, overseas product EPD, and LCI DB. Carbon emissions from major bathroom materials are listed in

Table 5. Carbon emissions were calculated by multiplying the input quantity by the carbon emission factor (carbon emissions = quantity × carbon emission factor).

As for the scope of analysis, the quantities of each material used to construct the wet bathroom and environmental load-reducing modular bathroom were calculated to compare and analyze carbon emissions (kgCO2-eq) in the material production stage.

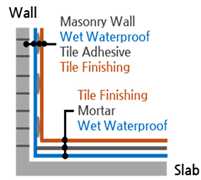

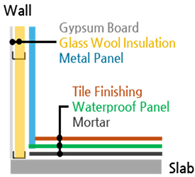

The analysis unit is one bathroom, and major materials were classified into floor waterproofing materials, cement mortar, wall materials, ceiling materials, and finishing materials. In the wet construction method, masonry was applied with bathroom partition wall and AP/PD wall materials for floor waterproofing and wall tiling. In the modular construction method, a lightweight steel-framed wall was applied because floor waterproofing and wall tiling were not necessary, and ALC blocks were applied to the AD/PD side to minimize wet construction.

Table 6 presents the diagrams and major materials of the wet and modular bathrooms.

3. Results

3.1. Material Selection and Performance Evaluation Results for the Modular Bathroom

Performance evaluation was performed following the KS test standards to select materials for constructing the modular bathroom. The results are as follows:

3.1.1. Floor Waterproof Panel Material Evaluation Results

Three waterproof panel materials were evaluated for constructing the modular bathroom. The results are presented in

Table 7.

In the evaluation results, the SMC waterproof panel can form a desired shape because the sheet flows inside the metal mold when the unsaturated polyester resin reinforced with fillers, catalysts, release agents, and glass fibers is inserted into the heated metal mold and compressed [

31]. This increases the waterproof panel strength by enabling rib formation and facilitates the integrated production of wall panel joints. This method is highly productive by producing approximately 100 units for one press per day and can ensure uniform quality. The production of a metal mold, however, requires considerable initial cost.

The FRP waterproof panel is fabricated using the manual deposition method (Hand-lay-up). Because it is fabricated by repeatedly depositing glass fibers and resin, the fabrication time is longer than that for SMC and the quality significantly varies depending on the skill level of workers [

32]. This method involves low productivity because two to four units can be produced by two to three workers per day depending on the skill level, and the skill level of the workers determines the quality. Moreover, this method is favorable for customized low-volume production but not for mass production and quality assurance.

The TPR waterproof panel is fabricated by heating and bending a thermoplastic sheet and applying thermal fusion welding to joints to prevent leakage. This method can be used to produce 50 to 70 units per day, and performance depends on the skill level of workers during the welding process [

33].

In terms of constructability, the SMC and FRP waterproof panels can reflect the floor gradient and produce geometry for wall panel assembly, thereby ensuring uniform quality and convenient construction. However, compared with the SMC and FRP waterproof panels the TPR waterproof panel requires separate mortar work for finishing after waterproof panel installation. Thus, the poor floor gradient caused by the skill level of workers increases the likelihood of the stagnant water defect.

3.1.2. Wall Panel Material Test Results

Table 8 presents the results of testing four wall panel materials following the KS test standards for wall panel material selection.

In the wall panel material test results, the porcelain enamel exhibited rust in the corrosion resistance test and surface discoloration in the chemical resistance test. The plastic composite board exhibited bending in the boiling water resistance, detergent resistance, and corrosion resistance tests as well as bending/surface deformation in the heat resistance test. The inorganic composite board could not meet performance because surface discoloration occurred in the chemical resistance test. Only the color steel plate met the performance criteria as no problem was observed for all test parameters.

3.2. Mock-Up Test Results

3.2.1. Basic Performance Test Results

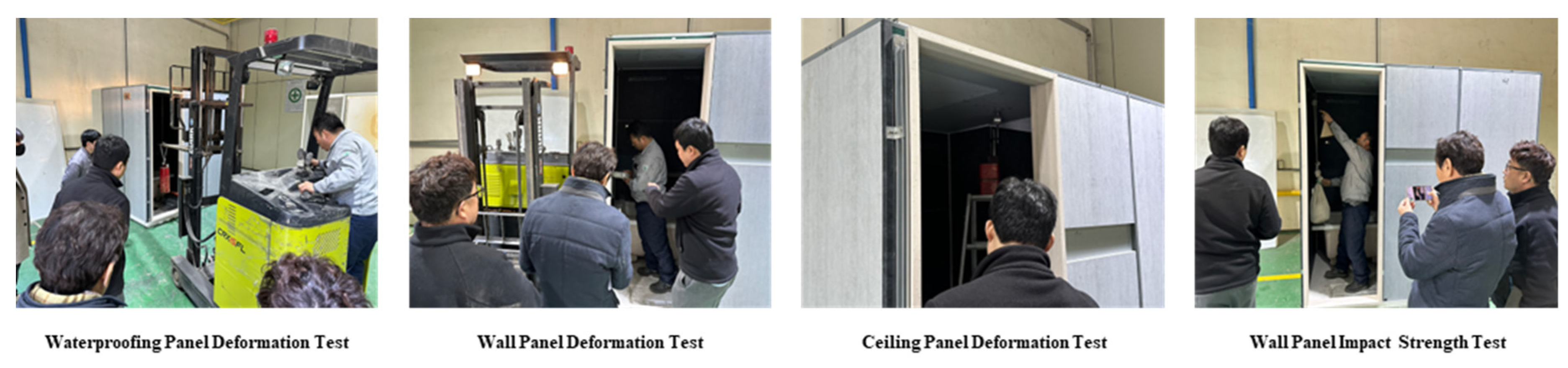

After the assembly of the aforementioned materials, the overall performance of the modular bathroom system was evaluated, as shown in

Figure 3. The results are presented in

Table 9.

In the moisture resistance test, no problem was observed from all of the floor waterproof panel, wall panel, ceiling panel, and each joint. In the deformation test results, 2 mm was measured from the ceiling panel for a tolerance of 10 mm or less and 1 mm from the waterproof panel for a tolerance of 5 mm or less, representing approximately 20% of the tolerance for both panels. For the wall panel, 3 mm was measured for a tolerance of 7 mm or less, representing approximately 40% of the tolerance.

In the impact strength test, no problem was observed from the wall panel, waterproof panel connected to the wall panel, and ceiling panel joints, thereby ensuring impact resistance. In the surface hardness test, the Barcol hardness value was 54, which met the criterion of 30 or higher. The basic performance test results confirmed that the developed modular bathroom meets performance requirements for the construction and use of modular bathrooms.

Figure 3.

Basic performance test for the modular bathroom.

Figure 3.

Basic performance test for the modular bathroom.

Table 9.

Basic performance test results for the modular bathroom.

Table 9.

Basic performance test results for the modular bathroom.

| Category |

Criterion |

Test result |

Performance level |

| Moisture resistance |

All |

No problem |

No problem |

Satisfactory |

| Deformation |

Wall panel |

7 mm or less |

3 mm |

Satisfactory |

| Ceiling panel |

10 mm or less |

2 mm |

Satisfactory |

| Waterproof panel |

5 mm or less |

1 mm |

Satisfactory |

| Impact strength |

Wall panel |

No problem |

No problem |

Satisfactory |

| Waterproof panel |

No problem |

No problem |

Satisfactory |

| Surface hardness |

Waterproof panel |

Barcol hardness of 30 or higher |

54 |

Satisfactory |

3.2.2. Field Applicability Evaluation Results

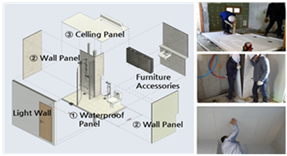

Evaluation was performed to verify field applicability. The construction sequences of the wet and modular bathrooms are shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5, respectively. The wet bathroom requires water supply, equipment for electrical outlet construction, and temporary work for electricity before bathroom construction. These are followed by masonry wall construction for waterproofing and tile finishing, wooden door temporary frame construction, liquid and membrane waterproofing after surface arrangement, freshwater tests for checking leakage, heating pipe installation for bathroom floor heating, plastering for wall tiling, wall tiling, flood BED mortar construction for floor tiling, floor tiling, wall and floor tile grouting, masonry shelf top plate attachment, wooden door main frame and ceiling panel installation, sanitary ware/furniture/accessory installation, and cauking.

The modular bathroom is constructed in order of floor mortar pouring for waterproof panel installation, waterproof panel installation, wall panel assembly, lightweight steel-framed partition wall construction, wooden door temporary frame construction, ceiling panel assembly, wooden door main frame installation, masonry shelf top plate attachment, floor tiling and grouting, sanitary ware/furniture/accessory installation, and cauking.

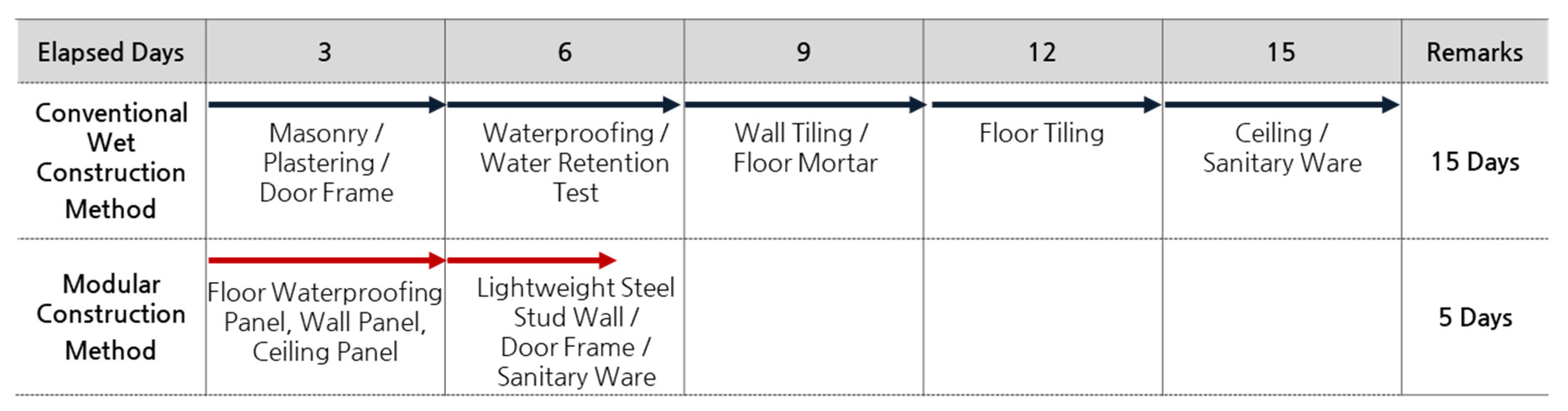

The wet bathroom is constructed through 11 tasks and 22 processes, as presented in

Table 10, and 15 days are required for bathroom unit construction, as shown in

Figure 6. The modular bathroom is constructed through three tasks and 15 processes, as presented in

Table 11, and five days are required for bathroom unit construction, as shown in

Figure 6. When a wet bathroom is changed into a modular bathroom, tasks can be reduced by approximately 70%, processes reduced by 30%, and the bathroom unit construction period reduced.

Figure 4.

Wet bathroom construction sequence.

Figure 4.

Wet bathroom construction sequence.

Figure 5.

Modular bathroom construction sequence.

Figure 5.

Modular bathroom construction sequence.

Table 10.

Wet bathroom tasks.

Table 10.

Wet bathroom tasks.

| Wet |

| No. |

Task |

Content |

| 1 |

Equipment |

Faucet box installation |

| 2 |

Electricity |

Electric box installation |

| 3 |

Masonry |

Masonry (wall) |

| 4 |

Masonry (shelf) |

| 5 |

Wooden door |

Wooden door temporary frame |

| 6 |

Filling |

| 7 |

Waterproofing |

Liquid waterproofing |

| 8 |

Membrane waterproofing |

| 9 |

Job |

Freshwater |

| 10 |

Plastering |

Plastering |

| 11 |

Tile |

Wall tiling |

| 12 |

Floor mortar |

| 13 |

Floor tiling |

| 14 |

Wall tile grouting |

| 15 |

Floor tile grouting |

| 16 |

Job |

Masonry shelf top plate |

| 17 |

Wooden door |

Main frame |

| 18 |

Interior |

Ceiling panel |

| 19 |

Furniture |

Furniture |

| 20 |

Equipment |

Sanitary ware and accessories |

| 21 |

Job |

Shower booth |

| 22 |

Cauking |

Cauking |

Table 11.

Modular bathroom tasks.

Table 11.

Modular bathroom tasks.

| Modular |

| No. |

Task |

Content |

| 1 |

Modular bathroom |

Floor mortar |

| 2 |

Waterproof panel |

| 3 |

Wall panel |

| 4 |

Lightweight wall |

Lightweight wall frame |

| 5 |

Lightweight wall gypsum |

| 6 |

Wooden door |

Wooden door temporary frame |

| 7 |

Modular bathroom |

Ceiling panel |

| 8 |

Main frame |

| 9 |

Masonry shelf top plate |

| 10 |

Floor tiling |

| 11 |

Floor tile grouting |

| 12 |

Furniture |

| 13 |

Sanitary ware and accessories |

| 14 |

Show booth |

| 15 |

Cauking |

Figure 6.

Comparison of bathroom unit construction periods.

Figure 6.

Comparison of bathroom unit construction periods.

Table 12 compares the amounts of materials used for the wet and developed modular bathroom, stating 4,355 and 1,220 kg of used materials, respectively. This indicates that the weight could be reduced to the 28% level.

For the floor, 867 kg was used for the wet bathroom as mortar (800 kg) and tiles, and subsidiary materials (58 kg) were mainly used. For the modular bathroom, the weight was reduced by approximately 37% to 550 kg, as the waterproof panel (28 kg) and mortar (482 kg) were mainly applied. For the walls, 3,479 kg was calculated for the wet bathroom as masonry (2,247 kg), remitar for plastering (660 kg), and tiles, and subsidiary materials (543 kg) were used. For the modular bathroom, the weight decreased to the 19% level (662 kg) compared with that of the wet bathroom due to the use of a lightweight steel-framed wall and subsidiary materials (413 kg), as well as the wall panel (189 kg).

Table 12.

Results of calculating the amounts of each bathroom material used.

Table 12.

Results of calculating the amounts of each bathroom material used.

| 1 bathroom |

Wet bathroom |

Modular bathroom |

| Material |

Weight (kg) |

Material |

Weight (kg) |

| Floor |

Waterproof |

9 |

Waterproof panel |

28 |

| Tile (adhesive included) |

58 |

Tile (adhesive included) |

39 |

| Mortar |

800 |

Mortar |

482 |

| Sub total |

867 |

Sub total |

550 |

| Wall |

Masonry |

2,247 |

ALC |

60 |

| Waterproof |

28 |

Lightweight wall |

413 |

| Plastering |

660 |

Wall panel (filler included) |

189 |

| Tile |

543 |

| Sub total |

3,479 |

Sub total |

662 |

| Ceiling |

Ceiling panel |

9 |

Ceiling panel |

9 |

| |

Total |

4,355 |

Total |

1,220 |

3.3. LCA Results

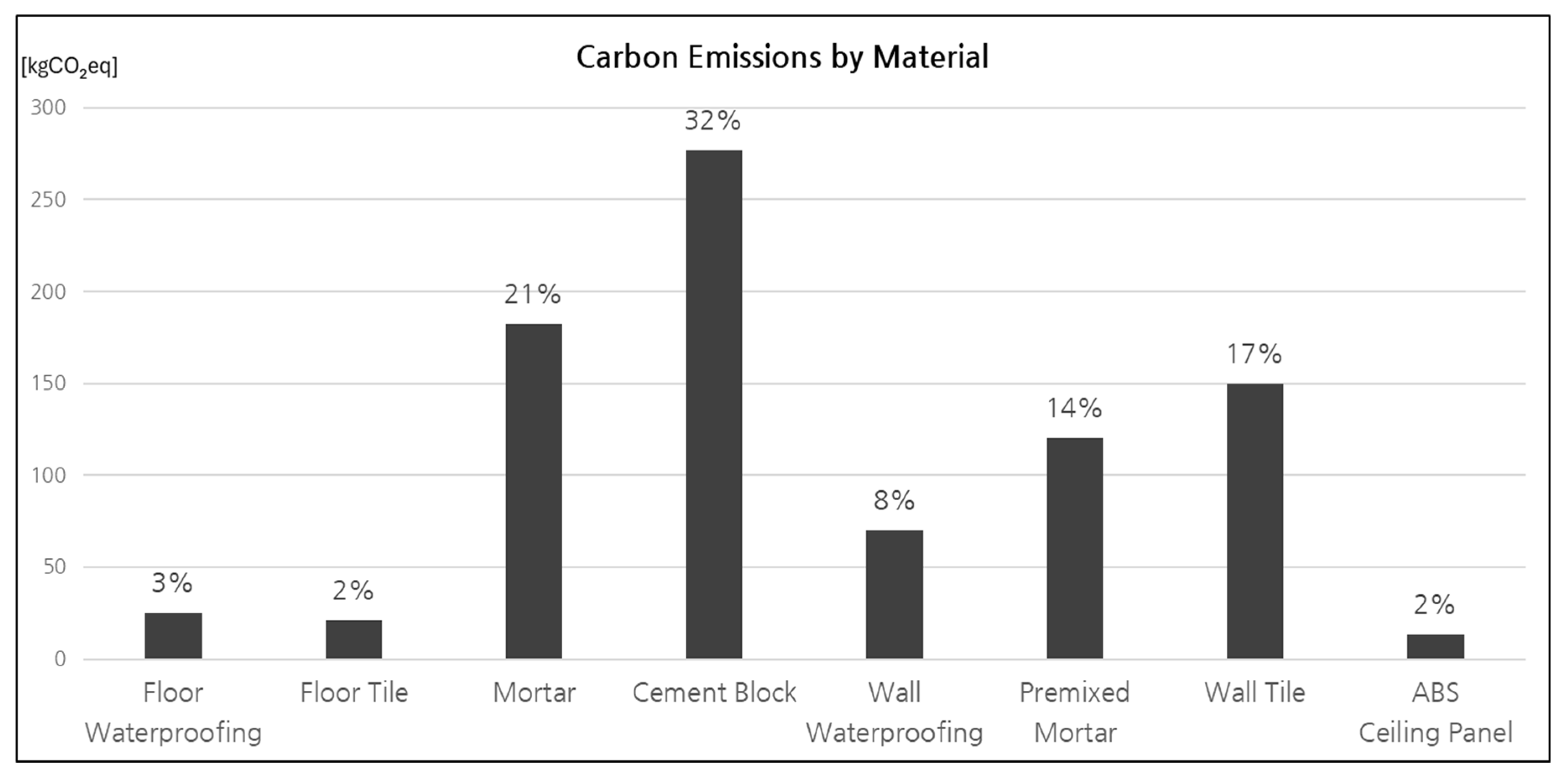

LCA was conducted by applying the carbon emission factors in the material production stage for the major building materials used in the wet and modular bathrooms. The carbon emission analysis results are presented in

Table 13. The total carbon emissions from the wet bathroom were 860 kgCO₂eq/unit. Masonry (32%), mortar (21%), tile (19%), and plastering (14%) were identified as key carbon emission factors, as shown in

Figure 7. In particular, masonry, mortar, and plastering represented 67%, indicating that cement-based materials served as the main causes of carbon emissions.

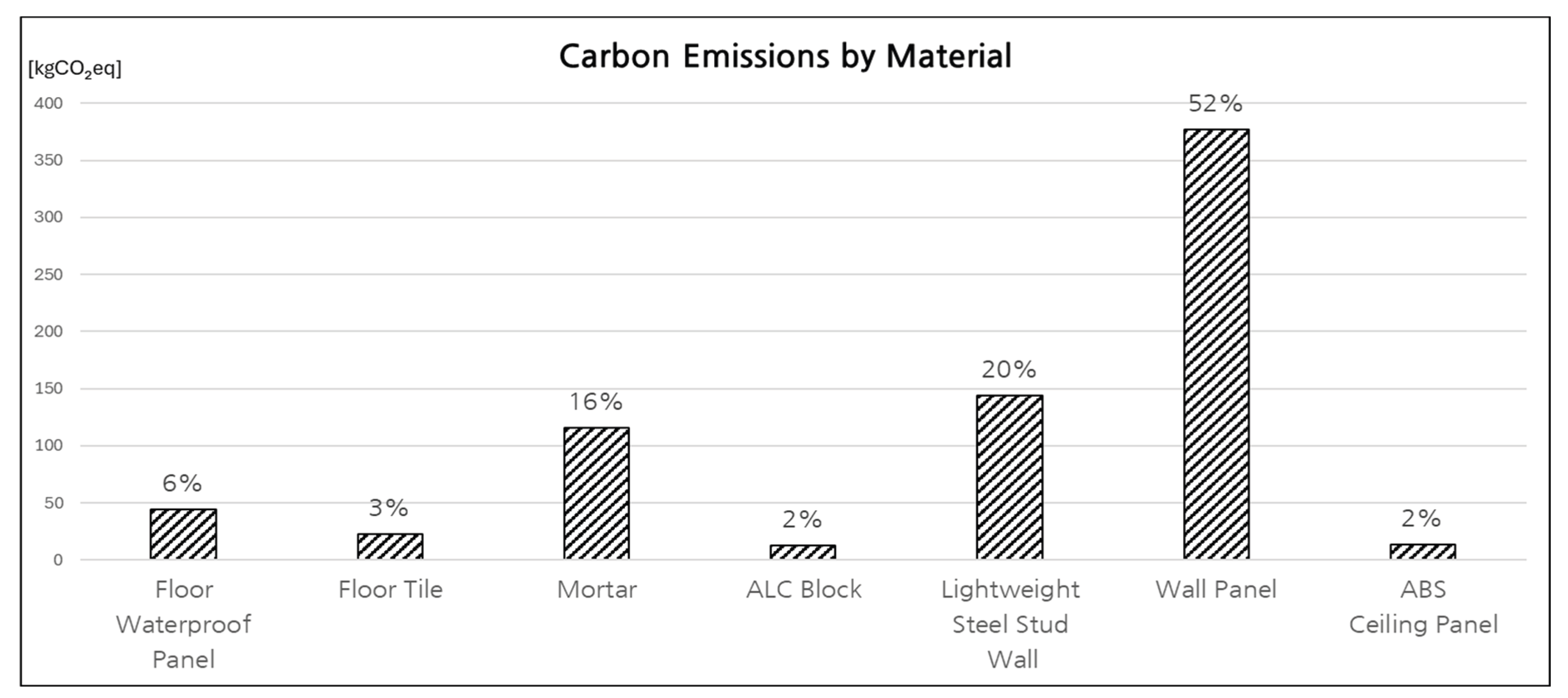

The total emissions from the modular bathroom were 730 kgCO₂eq/unit, which is 15% lower than that of the wet bathroom. The key carbon emission factors were found to be the wall panel (52%), lightweight steel frame (20%), and mortar (16%), as shown in

Figure 8. Among them, the wall panel and lightweight steel frame represented 72%, indicating that steel-based and subsidiary materials for modularization served as the main causes of carbon emissions.

For the floor, carbon emissions decreased by 20% from 229 kgCO₂eq for the wet bathroom to 182 kgCO₂eq for the modular bathroom. For the walls, the emissions decreased by 13% from 617 kgCO₂eq (wet) to 535 kgCO₂eq (modular).

Table 13.

Carbon emission calculation results.

Table 13.

Carbon emission calculation results.

| Part |

Wet |

Modular |

| Material |

Carbon emissions (kgCO₂eq) |

Material |

Carbon emissions (kgCO₂eq) |

| Floor |

Waterproof |

25 |

Waterproof panel |

44 |

| Tile (adhesive included) |

21 |

Tile (adhesive included) |

23 |

| Mortar |

182 |

Mortar |

116 |

| Sub total |

229 |

Sub total |

182 |

| Wall |

Masonry |

277 |

ALC |

13 |

| Waterproof |

70 |

Lightweight wall |

144 |

| Plastering |

120 |

Wall panel |

377 |

| Tile |

150 |

|

|

| Sub total |

617 |

Sub total |

535 |

| Ceiling |

Ceiling panel |

14 |

Ceiling panel |

14 |

| |

Total |

860 |

Total |

730 |

Figure 7.

Carbon emissions from each wet bathroom material.

Figure 7.

Carbon emissions from each wet bathroom material.

Figure 8.

Carbon emissions from each modular bathroom material.

Figure 8.

Carbon emissions from each modular bathroom material.

4. Discussion

This study compared and analyzed carbon emissions in the A1–A3 material production stage under the application of wet and modular bathrooms to the functional space known as bathroom unlike building unit LCA. To this end, a modular bathroom was constructed by evaluating and selecting adequate materials, and its basic performance and field applicability were verified following Korea’s KS standards through the mock-up test.

First, materials for the modular bathroom were selected.

When three floor waterproof panels were evaluated, the SMC waterproof panel was suitable in terms of quality deviation minimization by the metal mold, mass production, and manpower influence minimization.

Based on the wall panel selection results, the porcelain-enameled panel exhibited limitations in corrosion resistance, the plastic composite board exhibited limitations in durability, and the inorganic composite board exhibited limitations in chemical resistance. This implies that they can be vulnerable to real-use conditions in actual residential environments, such as humidity, detergent, and temperature changes, over time. The color steel plate, however, exhibited stable performance for all test parameters, including corrosion resistance, durability, and chemical resistance. In particular, it is expected to exhibit stable performance over time in actual bathroom environments because corrosion, surface deformation, and bending were not observed. Consequently, this study confirmed that color steel plates are the most suitable materials for modular bathroom wall panels.

Second, the mock-up test results showed that the modular bathroom system met the basic performance criteria for all parameters, including moisture resistance, deformation resistance, impact strength, and surface hardness. In particular, the ceiling and waterproof panels exhibited approximately 20% of the tolerance and the wall panel approximately 40% of the tolerance in the deformation test, indicating that structural stability were ensured. In the impact strength test, impact resistance was also proven as no abnormality was observed from the members and joints. In addition, the surface hardness value exceeded the criterion, ensuring sufficient resistance to walking, scratching, and material loading, which frequently occur during field construction. Consequently, the developed modular bathroom is suitable in terms of field applicability and usability.

The field applicability evaluation results revealed that, compared with the wet bathroom, the modular bathroom can significantly reduce tasks and processes. As the wet bathroom depends on a number of wet processes (e.g., waterproofing, plastering, and tiling), it involves a long construction period, high possibility of quality deviation, and difficulty in site management due to process interference. However, the modular bathroom simplified processes and shortened the construction period through the on-site assembly of prefabricated members, including the waterproof, wall, and ceiling panels.

Although the wet bathroom required 11 tasks, 22 processes, and a construction period of 15 days, the modular bathroom reduced them to three tasks, 15 processes, and five days, resulting in an approximately 70% reduction in the number of tasks, a 30% reduction in the number of processes, and a 65% reduction in construction period. This shows the possibility of reducing manpower dependence and shifting to standardized construction methods in the domestic construction industry environment with intensified instability in the supply of skilled workers. A reduction in construction period may also lead to overhead cost savings and process interference minimization at construction sites, which is expected to improve the stability of the overall project schedule. In addition, a reduction in the proportion of wet processes is favorable from an environmental perspective as it can reduce noise, dust, and waste that occur during construction. These indicate that, compared with the conventional wet bathroom, the modular bathroom has additional benefits in terms of ease of quality control, stability in manpower supply, and a reduction in environmental loads as well as construction efficiency.

The comparison of the amount of materials used showed that the modular bathroom can reduce weight by approximately 28% compared with that of the wet bathroom. In the wall sector, in particular, the modular method that applied the lightweight steel-framed wall and wall panel could reduce weight to the 19% level compared with that of the wet method that applied masonry, plastering, and tiles. This is because, compared with the conventional wet method, the modular bathroom facilitates both structural weight reduction and process simplification through a reduction in wet processes. In addition, a reduction in the amount of materials used may lead to a reduction in environmental loads during the production and transportation of materials from an LCA perspective as well as an improvement in construction efficiency.

Third, the LCA analysis results revealed high carbon emissions from the wet bathroom because of the use of cement-based materials (e.g., masonry, mortar, and plastering) in large quantities. However, the modular bathroom could reduce total emissions by approximately 15% by replacing wet processes and applying lightweight materials.

The modular bathroom, however, showed the concentration of environmental loads by certain materials because the proportions of the wall panel and lightweight steel frames were 52% and 20%, respectively. This shows that the future carbon reduction strategies of the modular system should lead to follow-up studies on the eco-friendliness of alternative materials and improvements in production processes for carbon emission reduction rather than being confined to simple replacement of wet processes.

In addition, the wet bathroom is highly likely to cause additional environmental loads during processes (e.g., an increase in construction period and waste generation), whereas the modular bathroom is more favorable for carbon reduction at the site and ensuring quality stability through process simplification and reduced material inputs. Therefore, the modular bathroom can be considered an alternative for improving both environmental performance and productivity throughout the construction project in addition to initial embodied carbon reduction.

This study conducted various analyses for carbon reduction using the modular bathroom. However, it presents the following limitations:

First, the scope of LCA was confined to A1–A3 (material production stage) and could not include the A4 and A5 (transportation and construction), B (use and maintenance), and C/D (dismantling and recycling) stages.

Second, because of limitations in securing carbon emissions from the applied products, the indicators of products similar to the products certified by Korea EPD were utilized for some materials, and the national LCI DB and overseas product EPD were applied.

Third, LCA that linked the structural member reduction effect caused by the weight reduction of the modular bathroom with structural design could not be conducted, requiring further research.

Despite these limitations, this study has the following significance.

First, it quantitatively presents the possibility of reducing embodied carbon in the construction sector through a detailed functional space unit approach as a step toward building-level LCA.

Second, materials and processes were simplified compared with the case of tile-oriented wet finishing, and a direction to reduce A1–A3 carbon emissions was presented by applying large metal panels that are not generally used in Korean residential bathrooms. In addition, performance verification through the mock-up test proved that metal panel design from a DfMA perspective is practically applicable at Korean construction sites. This study also has originality and industrial implications in that it confirmed that the one-piece molding and standardization characteristics of the SMC waterproof panel are suitable for modular construction from a DfMA perspective.

Third, this study exhibited originality in research in that it improved applicability in Korea by applying an LCA methodology that combined the EPD of actual products, domestic and overseas LCI DBs, and overseas product EPD considering the Korean construction environment. The results of this study are also expected to be used as basic data for establishing building material low-carbonization strategies at the national level in the future.

5. Conclusion

This study aimed to develop an environmental load-reducing modular bathroom system for residential buildings in Korea and to compare carbon emissions in the material production stage with the conventional wet construction method. To this end, material testing following the KS standards, performance evaluation through the mock-up test, material input calculation, and life cycle assessment (LCA) were conducted. The conclusions are as follows.

First, the material evaluation results revealed that the SMC waterproof panel, which can minimize quality deviation and facilitate mass production, is suitable as a floor waterproof panel, and that the color steel plate that met all of the performance criteria of the KS test standards is the optimal material for wall panels. This selection of materials for the modular bathroom is expected to ensure uniform quality and long-term durability.

Second, the mock-up test results showed that the developed modular bathroom met the KS standards in the moisture resistance, deformation, impact strength, and surface hardness tests. In particular, compared with the wet bathroom, the modular bathroom could ensure both construction efficiency and ease of quality control through an approximately 70% reduction in construction tasks, a 30% reduction in processes, and a 65% reduction in construction period for the unit bathroom. Its weight was approximately 28% of that of the wet bathroom, confirming the possibility of weight reduction.

Third, in the LCA analysis results, carbon emissions from the wet bathroom in the material production stage were 860 kgCO₂eq/unit, whereas those from the modular bathroom were 730 kgCO₂eq/unit, indicating an approximately 15% reduction in carbon emissions. Cement-based materials (e.g., masonry and mortar) were key emission factors for the wet construction method as their proportion was 67%, whereas steel-based materials (e.g., wall panels and lightweight steel-framed walls) exhibited a large proportion for the modular method. This shows that the modular bathroom can ensure the initial embodied carbon reduction effect by reducing the use of cement-based materials.

In summary, this study shows that, compared with the conventional wet bathroom, the developed modular bathroom is an alternative construction method that can ensure construction efficiency, uniform quality, and the initial embodied carbon reduction effect. It is expected to contribute to addressing the challenges of solving the shortage of skilled workers in the Korean construction industry, improving construction quality, and achieving carbon neutrality.

In this study, however, the scope of LCA was confined to A1–A3 (material production stage), and overseas DB was utilized for some materials because of limitations in securing domestic EPD. In addition, the impact of the weight reduction of the modular bathroom on structural members could not be examined in conjunction with structural design.

Therefore, future research requires LCA that includes A4 and A5 (transportation and construction), B (use and maintenance), and C/D (dismantling and recycling) stages; development of substitutes for wall panels and steel-based materials and improvements in eco-friendly production processes; and quantitative verification that links the weight reduction effect of the modular bathroom with structural design. Based on this, it will be possible to enhance the environmental performance and technical feasibility of the modular bathroom.

This study is significant in that it provided basic research data for promoting carbon-reducing modular bathrooms in Korea when the importance of initial embodied carbon in the material production stage is highlighted worldwide. Furthermore, it can be used as research that presents a direction for building material selection methods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-H.L.; methodology, S.-H.L., J.-H.J. and J.-C.P.; software, S.-H.L.; validation, J.-H.J.; formal analysis, Y.-W.S. and S.-H.L.; investigation, J.-H.J. and S.-H.L.; resources, J.-H.J. and S.-H.L.; data curation, Y.-W.S. and S.-H.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-W.S. and S.-H.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-W.S. and S.-H.L. and J.-C.P.; visualization, Y.-W.S.; supervision, Y.-W.S.; project administration, J.-H.J. and S.-H.L.; funding acquisition, J.-C.P. and Y.-W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00217322).

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UNEP. Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction 2023/2024.

- Presidential Commission on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth. 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) towards 40% Reduction in Total GHG Emissions by 2030; 2021. Available online: https://www.2050cnc.go.kr/flexer/html/storage/board/base/2021/10/27/BOARD_ATTACH_1635316400009.hwp.files/Sections1.html (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Greenhouse Gas Inventory and Research Center of Korea. 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) Enhancement towards 40% Reduction from 2018 Emissions; 2021. Available online: https://tips.energy.or.kr/statistics/statistics_view0108.do (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). ISO 14025:2006 Environmental Labels and Declarations—Type III Environmental Declarations—Principles and Procedures; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). EN 15804:2019 Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). EN 15978:2011 Sustainability of Construction Works—Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings—Calculation Method; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Korea Environmental Industry and Technology Institute. Analysis on the Market Status and Effects of Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) Certified Products; 2022. Available online: https://www.keiti.re.kr/common/board/Download.do?bcIdx=37766&cbIdx=318&streFileNm=8e753a67-7786-4586-ac59-d13e35660d1d&fileNo=1 (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Arslan, D.; Sharples, S.; Mohammadpourkarbasi, H.; Khan-Fitzgerald, R. carbon analysis, life cycle assessment, and prefabrication: A case study of a high-rise residential built-to-rent development in the UK. Energies 2023, 16, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Prefabricated and modularized residential construction: A review of present status, opportunities, and future challenges. Buildings 2025, 15, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Ahn, Y.; Roh, S. Comparison of the embodied carbon emissions and direct construction costs for modular and conventional residential buildings in South Korea. Buildings 2022, 12, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lützkendorf, T.; Balouktsi, M. Embodied carbon emissions in buildings: Explanations, interpretations, recommendations. Buildings & Cities 2022, 3, 964–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Green Building Council. Bringing Embodied Carbon Upfront; WGBC: London, UK, 2019; Available online: https://worldgbc.org/article/bringing-embodied-carbon-upfront/. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, E.; Orr, J.; Ibell, T. Quantification of uncertainty in product stage embodied carbon calculations for buildings. Energy Build. 2021, 251, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W. Carbon emission estimation of prefabricated buildings based on life cycle assessment Model. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2021, 20, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Scope-based carbon footprint analysis of US residential and commercial buildings: An input–output hybrid life cycle assessment approach. Build. Environ. 2014, 72, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Masera, G. Methodologies for assessing building embodied carbon in a circular economy perspective. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 522, 01014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F.; Woetzel, J.; Mischke, J.; Ribeirinho, M.J.; Sridhar, M.; Parsons, M.; Bertram, N.; Brown, S. Reinventing Construction: A Route to Higher Productivity; McKinsey Global Institute: 2017. Available online.

- Seong, Y.; Yoo, W. Analysis of Productivity in the Korean Construction Industry. Construction Issue Focus 2022-12; Construction and Economy Research Institute of Korea, 2022. (In Korean).

- Sung, Y.; Park, H.; Choi, S. Trends and strategies for securing technical workforce at construction Sites; Construction and Economy Research Institute of Korea: Seoul, Korea, 2025; Available online: (accessed on 9 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.-J.; Na, G.-Y. Estimating the appropriate size of foreign workers in construction (2022–2024); Construction and Economy Research Institute of Korea: Seoul, Korea, 2022; Available online: (accessed on 9 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Yeom, T.-J.; Boo, Y.-S.; Choe, G.-C.; Seo, D.; Hwang, E. Analysis of defects in multi-family housing by type, construction work and space—Focusing on applications to the defect review and dispute mediation committee. Journal of the Korea Institute of Building Construction 2024, 24(6), 717–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Han, M.-C.; Kim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-S. Analysis on characteristics of defects before inspection for apartment use. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 21(5), 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New South Wales Government. Serious Defects in Recently Completed Strata Buildings Across New South Wales; NSW Department of Customer Service: Sydney, Australia, 2021; (Research report, PDF). Available online: (accessed on 13 September 2025). [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS). Saving Time with Modular Bathroom Pods; Washington, DC, USA, 2017 (reissued 2025). “With traditional building, a multitude of trades need to be organized to realize the bathroom design. This requires a high degree of supervision and management…”. Available online: (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Son, S.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, K.-M.; Park, Y.-J. A Study on the types and causes of defects in apartment building construction. J. Korea Acad.-Ind. Coop. Soc. 2020, 2, 604–612. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, S.-H.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, D.-Y. A Study on reducing interference between trades in apartment construction. J. Korea Inst. Build. Constr. 2006, 6, 49–57. (In Korean) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modular Building Institute. Saving Time with Modular Bathroom Pods; Modular Building Institute: 2017. Available online: https://www.modular.org.

- Building and Construction Authority (BCA). Good Industry Practices—Prefabricated Bathroom Unit (PBU); CONQUAS Enhancement Series; Building and Construction Authority: Singapore, 2014; Available online: https://www1.bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-buildsg/quality/internal-partitionpbu.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- H+H UK Limited. (2024). Environmental Product Declaration: Standard Grade Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC) Blocks (HUB-1545). EPD Hub. https://www.hhcelcon.co.uk/.

- Kima Accessories Aps. (2023). Environmental Product Declaration: Plastic products made of recycled PP or ABS (EPD-KIM-20230120-CBC1-EN). Institut Bauen und Umwelt e.V. (IBU). https://epd-online.com.

- Alnersson, G.; Tahir, M.W.; Ljung, A.-L.; Lundström, T.S. Review of the Numerical Modeling of Compression Molding of Sheet Molding Compound. Processes 2020, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, M.; Bloom, D.; Ward, C.; Chatzimichali, A.; Potter, K. Hand Layup: understanding the manual process. Advanced Manufacturing: Polymer and Composites Science 2015, 1, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zang, Z.; Li, J.; Shi, Z.; Liu, M.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q.; Shang, Y.; Tian, C.; Jia, Z.; et al. Experimental study and application of TPO waterproofing membrane lapping process parameters. Materials 2025, 18, 3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).