Introduction

Sustainable construction materials are increasingly recognized as essential components in modern building projects due to their potential to reduce environmental impacts and improve the overall sustainability of the built environment. These materials are developed according to the principles of sustainable development, aiming to minimize negative environmental effects while maximizing benefits for people and the planet [

1,

2]. They are often characterized by properties such as renewability, recyclability, energy efficiency, and non-toxicity, which contribute to more efficient use of natural resources and reduction of harmful emissions during production, use, and disposal phases [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Examples of sustainable construction materials include recycled aggregates, natural resources like clay and stone, energy-efficient insulation products, and materials with a low carbon footprint. Among these, energy-saving materials play a crucial role by helping reduce energy consumption in buildings and other structures, thus significantly improving overall energy efficiency. Given that buildings account for a considerable share of global energy consumption—primarily for heating, cooling, and lighting—energy conservation represents a critical aspect of sustainable construction. The adoption of energy-efficient materials can thus lead to decreased energy use, reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and lower operating costs over the building’s lifespan [

7,

8].

Despite these clear environmental and economic advantages, integrating sustainable materials into cost estimation processes remains a significant challenge for construction companies [

9,

10]. A primary obstacle is the relatively high initial cost of procuring such materials, which tends to increase total project expenses during early construction phases. Additionally, companies often lack sufficient and reliable information regarding the durability, maintenance needs, and long-term benefits of sustainable materials, limiting their willingness and ability to invest in these solutions [

11]. Furthermore, there is a notable absence of standardized and transparent methodologies that adequately account for the full life-cycle costs and profitability of environmentally friendly materials in project cost estimates.

Currently, most automated cost estimation systems do not include dedicated modules or algorithms specifically designed to evaluate the incorporation of sustainable construction materials. This gap hinders the accurate assessment of both the economic and environmental viability of sustainable design options across a building’s entire lifecycle [

12]. Addressing these challenges requires further development of methodologies and tools to integrate long-term economic efficiency with environmental considerations in cost estimation workflows.

There are methods and software solutions aimed at comprehensive assessment of sustainable construction materials, including Life Cycle Costing (LCC) — a method that evaluates the total cost of ownership by considering initial investments, operational costs, and disposal expenses at the end of the material's lifecycle. Additionally, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) enables evaluation of the environmental impact of materials and buildings throughout their entire lifecycle, including carbon footprint and energy consumption. Integrating LCC and LCA supports a more holistic analysis of the economic and environmental efficiency of sustainable solutions. Specialized software tools such as OpenLCA, SimaPro, One Click LCA, and Athena Impact Estimator support these methods.

However, these tools often require significant manual data input and are not always integrated with automated cost estimation systems. In particular, there is a lack of universal and standardized solutions that effectively incorporate sustainable materials into automated cost evaluation and construction project planning processes. This gap limits the ability to perform comprehensive analyses of long-term economic efficiency and environmental sustainability, underscoring the need for the development of new methodologies and integrated digital platforms that facilitate more transparent and informed decision-making in the construction industry.

This article reviews the current state of sustainable construction materials integration into cost estimation, identifies key barriers and opportunities, and outlines potential pathways for future advancements, including the development of automated systems that facilitate informed, data-driven decision-making to promote sustainability in the construction sector.

Materials and Methods

Currently, the main approaches to integrating sustainable construction materials into cost estimation include life cycle costing (LCC) methods and building information modeling (BIM) tools. These approaches enable the consideration of both initial costs and operational expenses throughout the building’s lifespan. However, existing solutions are often limited by a lack of full automation, insufficient real-time data updates, and inadequate accounting for indirect economic benefits such as reduced repair frequency and maintenance costs [

13]. Many software products do not provide convenient mechanisms for scenario comparison and price database updates, which reduces the practical applicability of these methods. Furthermore, regional factors such as material availability, energy tariffs, and regulatory incentives significantly impact the integration and economic assessment of sustainable materials but are often insufficiently addressed by current tools. Finally, user-friendly interfaces and accessibility are critical for widespread adoption among designers, estimators, and contractors; yet, many existing systems remain too complex or specialized for broad use.This study adopts an applied analytical research design with the aim of identifying challenges and opportunities related to the integration of sustainable construction materials into automated cost estimation systems. The approach is based on practical experience from design and cost estimation activities in the construction and energy sectors, and includes an examination of currently used software solutions for budget forecasting in construction projects.

One of the central economic benefits of using sustainable materials is the potential increase in property value, which can enhance the overall market appeal of the completed structure. Additionally, these materials contribute to lowering long-term operating expenses, such as costs associated with heating, cooling, repairs, and maintenance [

14,

15,

16]. Further economic incentives include tax deductions and governmental subsidies, offered in many countries to encourage the use of environmentally friendly technologies [

17,

18,

19]. Properties built with sustainable materials also tend to command higher rental rates.

Despite these benefits, many contractors remain reluctant to adopt sustainable materials, largely due to the dominance of cost estimation methodologies that focus primarily on initial construction expenses rather than long-term financial gains [

20,

21,

22].

A comprehensive evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of using sustainable construction materials should be conducted during the planning and estimation phases, with an emphasis on long-term outcomes. For this purpose, the study proposes the development of an automated calculation system that includes a module for long-term performance and cost analysis.

Methodology / Algorithm of calculations

The methodology follows a stepwise algorithm, which includes the following stages:

Comparison of technical and economic parameters of traditional and sustainable materials, including cost, thermal conductivity, service life, and maintenance frequency.

Calculation of energy savings using formula (1) based on differences in energy consumption before and after implementation of sustainable materials, local energy tariffs, and operational period.

Estimation of maintenance and repair costs considering the frequency of repairs and repair cost for both material types.

Integration of all costs into Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), combining initial investment, operational savings, and maintenance expenses over the lifespan of the building.

Visualization and comparative analysis, presenting results in tables and graphs to clearly demonstrate cost differences and savings scenarios.

Each stage uses averaged industry data for hypothetical modeling, but the framework is designed to incorporate real-time data inputs and updates.

This module would integrate regularly updated price catalogs for both materials and labor, along with a dedicated block for assessing operational savings over time. For instance, annual energy savings achieved by using energy-efficient insulation panels made from sustainable materials can be calculated using the following formula:

Where:

E is the total energy cost savings over the operation period;

C before is the energy cost prior to using sustainable materials;

C after is the energy cost after implementation;

P is the local electricity price (USD per kWh);

Y is the number of operational years.

This example represents savings of $48,000 over a 10-year period, or $4,000 annually, based on hypothetical values used to demonstrate the model's logic.

The proposed framework also includes indirect economic benefits such as reduced repair frequency and associated costs. For instance, assuming a repair cost R=$5,000, a building constructed with conventional materials may require 6 major repairs over 12 years ($30,000 total), whereas the same building using sustainable materials may only require 3 repairs ($15,000 total). These differences can be visualized in comparative tables or charts to support decision-making.

Additionally, the tool should offer standardized options for material replacement, enabling users to substitute conventional materials with sustainable alternatives and immediately assess both the upfront and operational cost differences.

The need for a specialized cost estimation module is thus substantiated, with features such as real-time material databases, labor cost indexing, and built-in algorithms for life-cycle analysis. The methodology proposed here forms a practical basis for the development of a software specification for an automated system capable of evaluating the long-term profitability of sustainable construction solutions.

This is exemplified in the repair frequency chart. When comparing two different methods using sustainable materials, the maintenance will occur half as often as with conventional materials, as shown in our example with natural stone, thus resulting in savings on repairs:

Additionally, the need for creating a specialized calculation block in cost estimation systems has been justified. This block would include up-to-date price databases for sustainable materials, as well as labor cost information, to assess the long-term efficiency of decisions.

The proposed methodology is applied in nature and can serve as the basis for developing a technical assignment for the implementation of an automated tool to assess the profitability of sustainable design solutions in construction.

Calculation Automation Model and Its Necessity

Within the scope of this study, a conceptual model for automating the assessment of the economic efficiency of sustainable construction materials is proposed. Such a model could include several key components:

Material Selection Module, which contains a database of characteristics for both traditional and sustainable materials, including cost, thermal insulation properties, service life, and maintenance frequency, allowing for comparative analysis of their application.

Return on Investment (ROI) Calculation Module, designed to evaluate the payback period considering initial costs, savings on operational expenses, and potential tax incentives.

Energy Savings Calculation Module, which computes annual and cumulative energy savings based on the thermal properties of materials and current energy tariffs.

Visualization and Comparative Analysis Module, providing the generation of tables and graphs that demonstrate differences in costs and savings for various materials and operational scenarios.

The structure of such a model envisions the capability for regular updates of databases containing prices and technical specifications, ensuring the relevance and adaptability of calculations across different operating conditions and regions.

The development of this model is necessary due to the growing interest in sustainable construction and the increasing demand to reduce the carbon footprint. It is becoming essential to select materials that are not only environmentally friendly but also economically beneficial over the long term. However, current tools and software available on the market tend to focus on traditional construction materials or are limited to calculating specific aspects, such as energy efficiency or initial costs only.

There is a clear gap in the market for an integrated and flexible system capable of automatically:

Comparing a comprehensive set of characteristics for both traditional and sustainable materials (cost, energy efficiency, durability, maintenance expenses),

Taking into account climatic conditions, energy tariffs, and tax incentives,

Providing clear reports and scenario analyses to support material selection from the perspective of long-term economic efficiency.

Existing tools often lack support for regular updates of price and technical data, which reduces their accuracy and applicability. Additionally, many solutions are too complex for users without specialized knowledge, which slows down the adoption of sustainable construction practices.

If such an automation model were developed, it would enable designers, engineers, and clients to:

Quickly and reliably assess the economic benefits of using sustainable materials,

Make informed decisions by considering all key parameters,

Automate routine calculations and analyses, thereby reducing the time required for documentation and planning,

Enhance transparency and provide evidence-based support for sustainable construction choices, facilitating their practical implementation.

Thus, the creation of this model addresses a significant market need and could become a crucial tool in the transition towards more sustainable and economically justified construction practices.

Methodology and Case Testing (Hypothetical Example)

To verify and validate the developed methodology, a hypothetical analytical case of a standard office building with an area of 5000 m² located in Florida (climate zone 2A according to ASHRAE classification) was used. Input data for calculations, including prices of construction materials and electricity tariffs, in real conditions should be sourced from authoritative and up-to-date references such as the RSMeans database, official energy portals like EIA.gov, as well as regional price catalogs and regulatory documents. This type of structure and location was chosen due to its prevalence in commercial construction and its sensitivity to energy-saving measures in a hot-humid climate zone.

In this hypothetical case, approximate and averaged values based on typical industry data were used to demonstrate the principles of the model and possible outcomes:

Based on these data, an assessment of economic efficiency over a 30-year building lifecycle was conducted. This example illustrates how an automated calculation system can consider a complex set of factors such as cost, operation, maintenance, and energy consumption to support informed selection of sustainable materials with long-term economic benefits.

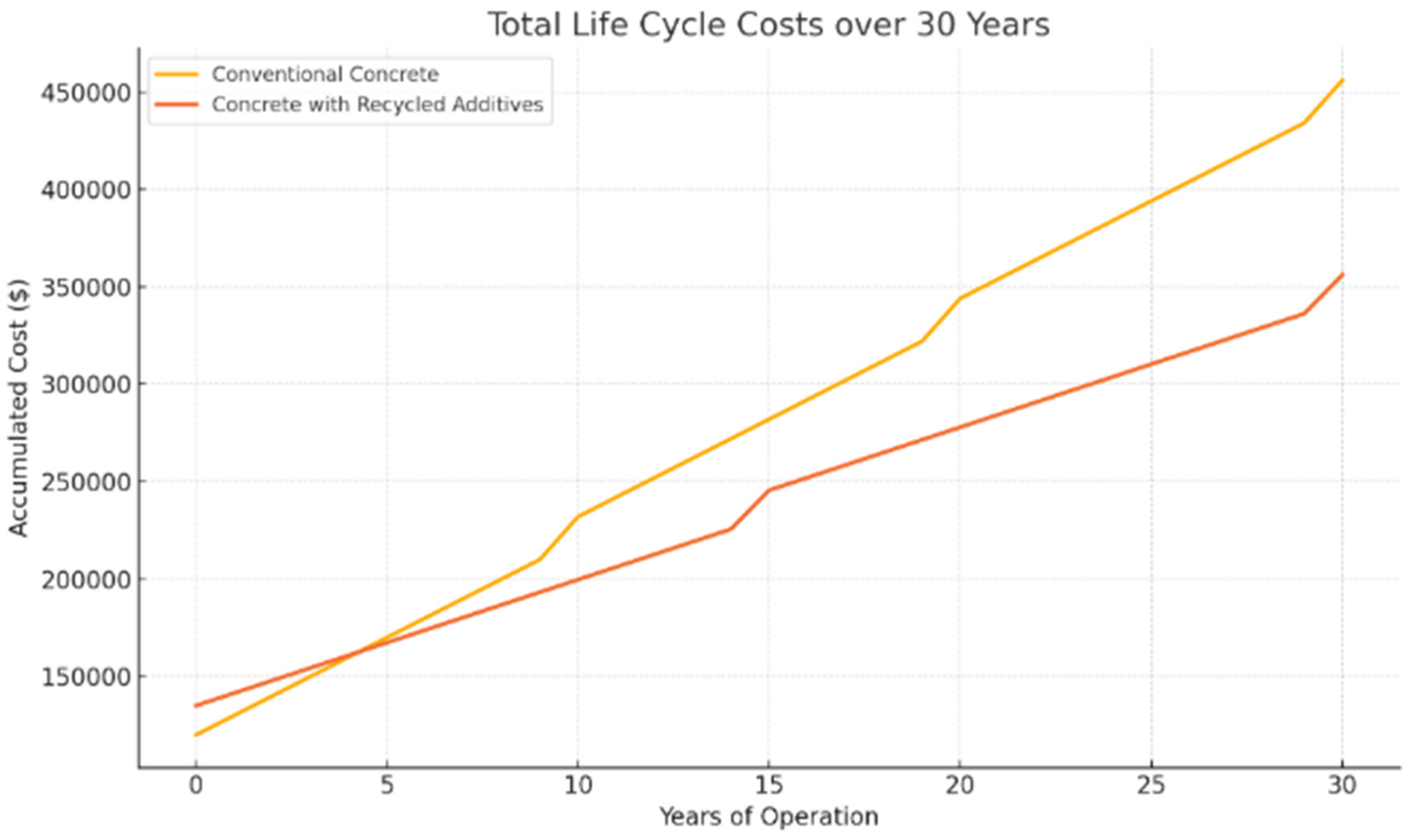

As a continuation of the visualization of the comparative analysis results between traditional and sustainable construction materials, a hypothetical example of a cumulative cost graph over a 30-year building operation period is presented, comparing two types of concrete: conventional and recycled additive-enhanced. The calculations accounted for initial material costs, energy expenses proportional to thermal conductivity and surface area, as well as maintenance costs considering repair frequency and cost. The electricity tariff was set at $0.12 per kWh, with repair intervals of 10 years for conventional concrete and 15 years for the modified version.

Graph 1.

Hypothetical Cumulative Cost Comparison Over 30 Years for Conventional and Recycled Additive Concrete in Building Operation.

Graph 1.

Hypothetical Cumulative Cost Comparison Over 30 Years for Conventional and Recycled Additive Concrete in Building Operation.

This visualization serves as an example of an analytical tool that could be integrated into the proposed system for assessing the economic efficiency of sustainable materials and for understanding the long-term effects of their use. This approach expands on existing software capabilities, which typically do not provide comprehensive comparisons between traditional and innovative materials considering their lifecycle and operational characteristics.

This comparison is particularly important for decision-makers in the early stages of project planning, as it illustrates how initial investments in sustainable materials—though often higher—can result in significantly reduced maintenance and replacement costs over the building’s life cycle. The visual format allows stakeholders to grasp the cumulative financial advantages of sustainability-oriented choices more intuitively than tabular data or isolated metrics. By projecting costs across a 30-year period, the graph supports evidence-based decision-making, helping to align material selection with long-term budgetary and environmental goals. It also highlights a current gap in many construction estimation tools, which often fail to account for life-cycle costs and long-term savings, thereby underrepresenting the value of sustainable alternatives.

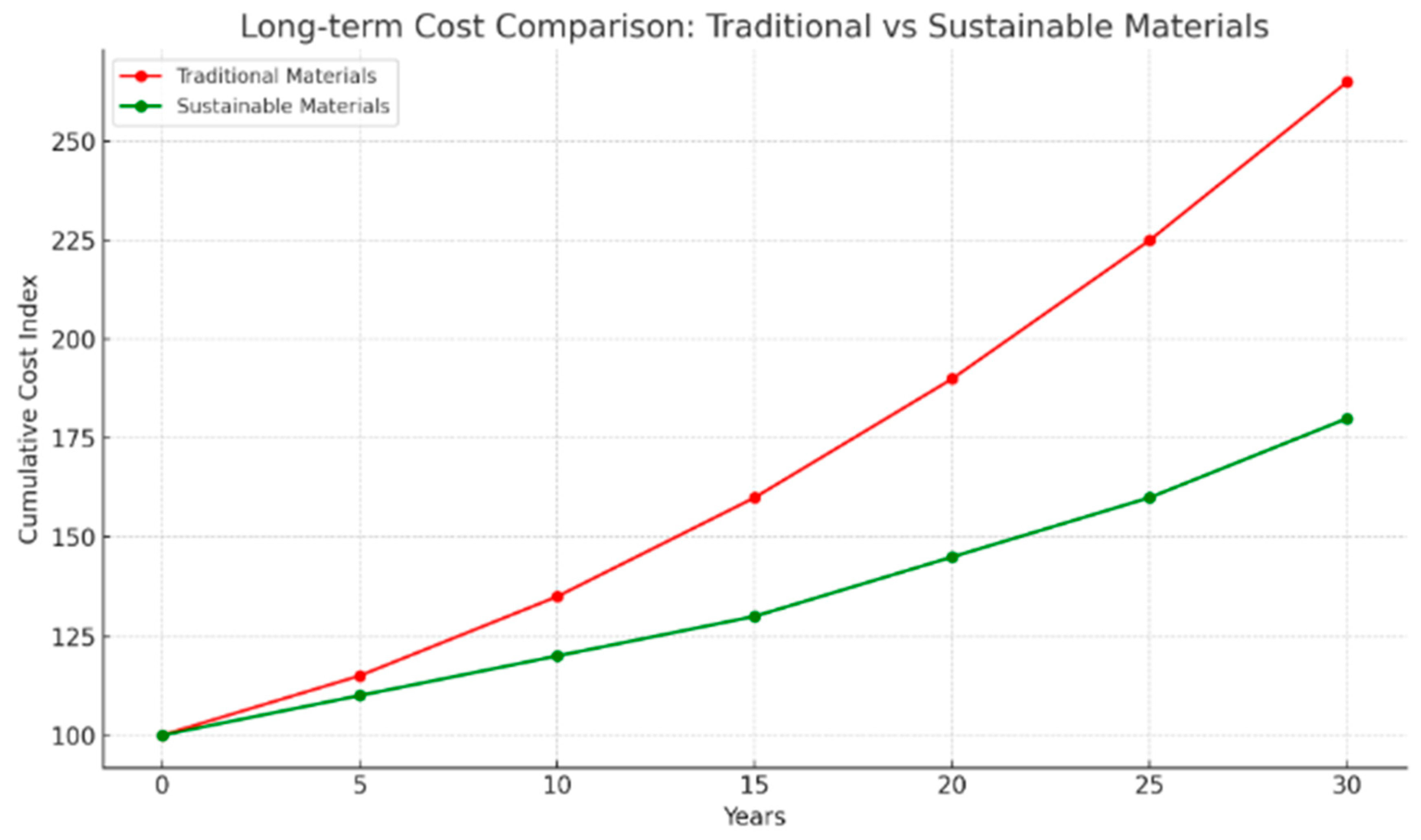

Graph 1.

Comparative Life-Cycle Cost Analysis of Conventional vs. Sustainable Construction Materials.

Graph 1.

Comparative Life-Cycle Cost Analysis of Conventional vs. Sustainable Construction Materials.

There is a clear shortage of intuitive comparative analysis tools and graphical visualizations on the market that effectively showcase the long-term economic advantages of sustainable construction materials compared to conventional, traditional materials. Existing software often neglects to provide integrated reports and visual comparisons of total cost of ownership and operational savings over the lifecycle, focusing instead on upfront costs or isolated factors. This lack of comprehensive, side-by-side analysis with traditional materials limits stakeholders’ ability to make informed decisions and hinders wider adoption of sustainable materials in construction projects.

The proposed model could be implemented as a module within existing BIM software or as a standalone decision-support tool using Python or web-based interfaces [

23].

As this study presents a hypothetical case without field implementation, future research should involve empirical testing on real projects and validation of long-term assumptions regarding operational savings and repair cycles.

Results

During the research, several analyses were conducted to assess the economic efficiency of using sustainable building materials in construction projects. Special attention was given to a comparative analysis between traditional and sustainable materials in terms of cost, durability, and operational characteristics over several years.

Economic Benefits of Sustainable Materials: In the conducted calculations, the savings resulting from the use of sustainable materials, such as energy-efficient insulating panels, were assessed. For instance, considering the durability of materials and their ability to reduce energy consumption, it was found that over the building's operational period, the use of sustainable insulating panels can lead to a 15-30% reduction in heating and cooling costs, depending on the region. Recognizing the long-term benefits at the project's inception is crucial for sustainable and economically efficient decision-making.

Famous Examples of Sustainable Construction.

1.1. Bullitt Center, Seattle, USA

The Bullitt Center is a six-story office building certified under the Living Building Challenge, making it one of the eco-friendliest commercial buildings in the world. The building is equipped with 575 solar panels on its roof, which provide energy for its operations. Additionally, it collects and purifies rainwater for use in household activities. As a result, the building produces more energy than it consumes, significantly reducing its carbon footprint [

24].

1.2. Bahnstadt, Heidelberg, Germany

Bahnstadt is a 116-hectare district designed with sustainable development principles in mind. The buildings in this district use 80% less energy for heating compared to traditional buildings. The district’s infrastructure includes over 3,000 smart meters, green roofs, and extensive cycling paths, all contributing to reduced carbon emissions and an improved quality of life [

25].

1.3. Wood City, Stockholm, Sweden

Wood City is the world’s largest project using glued and cross-laminated timber (CLT), developed by Atrium Ljungberg in the Sickla district. The project includes residential and commercial buildings, being constructed at a rate of 1,000 square meters per week—twice as fast as with concrete. The use of timber reduces carbon emissions by 40% and contributes to creating a healthier and more comfortable urban environment [

26].

1.4. Keppel Bay Tower, Singapore

Keppel Bay Tower is a 22-story building that, after renovation, became the first commercial building in Singapore to achieve net-zero carbon emissions. The renovation included the installation of solar panels, a smart lighting system, and efficient water management. These measures helped reduce energy consumption by 30% and achieve carbon neutrality.

2. Reduction of Maintenance and Repair Costs:

The analysis of maintenance costs also yielded positive results. For instance, using natural stone materials instead of traditional materials, which require more frequent repairs, led to a reduction in maintenance costs by half. While using conventional materials requires 6 repairs over 12 years, with sustainable materials, this number was reduced to 3 repairs. This results in substantial cost savings over the building’s operational lifespan [

27,

28,

29]. The importance of including a block for cost estimation systems lies in the visualization of long-term benefits through clear and illustrative charts and tables.

3. Impact on Real Estate Market Value:

Another crucial aspect is the impact of sustainable materials on the market value of real estate. Buildings constructed with sustainable materials can increase their market value, depending on the region and property type. This is due to the growing interest from buyers and tenants in eco-friendly and energy-efficient buildings [

30,

31,

32]. If the cost estimation block for construction with sustainable materials includes a tool powered by artificial intelligence that identifies relevant government programs offering benefits and grants, it will significantly ease the understanding of the advantages for the client.

4. Challenges in Integrating Sustainable Materials into Cost Estimations:

The main issue identified during the study was the difficulty in integrating sustainable materials into traditional cost estimation processes. Construction companies often face a lack of information regarding the durability and economic benefits of these materials, which makes it challenging to make decisions in favor of their use. The absence of a clear methodology for calculating the cost of these materials in estimates, considering the long-term profitability of the project, is also a significant barrier to the widespread adoption of sustainable solutions.

Therefore, despite the obvious advantages of using sustainable construction materials, the implementation of such solutions requires the development of new approaches and methods for cost estimation in the long term, as well as the further dissemination of information about the long-term economic and environmental benefits.

In this article, we examined a comparative cost analysis related to the use of sustainable construction materials, as well as the influence of regional factors on their economic efficiency and data visualization methods to support decision-making.

Comparative Cost Analysis:The simulation results demonstrate that despite the higher initial cost of sustainable materials, the total costs over the building’s life cycle are significantly lower. In particular, in the hypothetical example considered, using concrete with recycled material additives resulted in energy savings and reduced repair costs of about 20–25% over 30 years of operation. This confirms the importance of incorporating long-term indicators into the processes of cost estimation and budgeting for construction projects.

Influence of Regional Factors:The analysis revealed a significant impact of regional characteristics—such as electricity tariffs, climatic conditions, and availability of tax incentives—on the overall economic efficiency of using sustainable materials. For instance, in areas with higher energy tariffs, savings from reduced energy consumption become more noticeable, increasing the attractiveness of "green" technologies for investors and contractors.

Visualization and Decision Support:The use of graphs and comparison tables of the Total Cost of Ownership ensures transparency and ease of data perception for stakeholders. This contributes to a more balanced material selection at the design stage and reduces uncertainty in decision-making, which is crucial for the practical implementation of sustainable solutions.

Discussion

The study provided an overview of the integration of sustainable construction materials into cost estimation processes and evaluated the economic and environmental benefits these materials can offer at various stages of construction. The results demonstrated significant advantages for the long-term operation of buildings, particularly in terms of reducing operating costs such as heating, cooling, and ongoing maintenance. Several suggestions were also explored to improve the understanding of the benefits of using sustainable materials in construction.

Construction companies often prioritize short-term costs, posing challenges in recognizing the long-term economic and environmental advantages of implementing eco-friendly solutions. It is important to note that while sustainable materials may require higher initial investments, they provide substantial economic benefits during operation, including reduced energy costs and lower maintenance and repair expenses.

Currently, most cost estimation software lacks modules for calculating long-term savings associated with the use of sustainable materials, which hinders their integration into the real construction process. This is further evidenced by the absence of clear examples of savings that could demonstrate the potential economic advantages to construction companies.

Integration of Sustainable Construction Materials into Cost Estimations, particularly in the United States, demonstrates significant steps towards incorporating environmental solutions into construction practices. For example, tools like RSMeans and BuildingGreen provide extensive databases on the cost of sustainable materials, including green roofs, photovoltaic panels, and energy-efficient systems. However, these tools are generally focused on initial capital costs and rarely include an assessment of long-term economic effectiveness. Modern BIM systems, such as Edificius and RIB CostX, allow for project modeling with cost considerations but require additional modules and data for building life cycle analysis. Additionally, despite the existence of sustainable building standards such as LEED and Living Building Challenge, their criteria are not always integrated into cost estimations, limiting the ability to comprehensively assess profitability. Support programs like Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) help reduce initial costs through tax incentives and subsidies, but these are not directly reflected in traditional cost estimation systems [

33,

34,

35]. All of this highlights the need for the development of new tools and modules in cost estimation software that consider not only material costs but also their operational and environmental characteristics in the long term. Tools like RSMeans, BuildingGreen, BIM systems, and PACE are important, but they often require additional customization to account for long-term benefits and life cycle assessments. The development of new tools for cost estimations that integrate environmental and operational characteristics is essential for advancing sustainable construction [

36].

The long-term advantages of utilizing sustainable materials encompass decreased operational expenditures, enhanced property valuations, and increased tenant demand for energy-efficient buildings commanding premium rental rates. These benefits, along with the possibility of receiving tax incentives and subsidies, confirm the importance of using environmentally friendly materials. However, current cost estimation systems still cannot accurately account for these factors in their calculations.

An important limitation is that many construction companies currently lack the tools to fully evaluate the long-term economic benefits of using such materials. To overcome this problem, specialized automated systems need to be developed that can integrate data on the cost of sustainable materials and their long-term operational performance into standard cost estimations. These systems should consider not only the initial material costs but also the savings from reduced energy and maintenance costs over the long term.

Long-term benefits of using sustainable materials, such as reduced operational costs, increased property value, and improved environmental reputation, can significantly outweigh the initial expenses. This underscores the need for new approaches in cost estimation and design that can account for all aspects of sustainable construction.

For future research, it is important to continue developing and testing automated systems for calculating the profitability of sustainable construction materials. These systems could become valuable tools for designers and construction companies, helping them consider not only initial costs but also the long-term benefits associated with the use of environmentally friendly materials.

Limitations and Future Work.While this study proposes a conceptual framework for integrating sustainable construction materials into automated cost estimation systems, it has not yet been validated through large-scale practical implementations. The presented model is currently based on theoretical calculations and literature analysis. Future research should focus on conducting pilot implementations in real construction projects to assess the practical applicability and performance of the proposed system. Additionally, integrating the developed model into existing Building Information Modeling (BIM) platforms could enhance the accuracy and usability of cost estimations, providing a comprehensive tool for lifecycle cost management in sustainable construction [

37,

38].

Conclusions

The research identified key issues and opportunities associated with integrating sustainable building materials into cost estimation processes. The data reviewed and analysis conducted led to the following conclusions:

Gaps in Existing Cost Estimation Systems: Currently, automated cost estimation systems lack a specialized module for calculating the cost and long-term economic benefits of using sustainable building materials. This represents a significant barrier for construction companies aiming to integrate eco-friendly materials into their projects.

Need for Automation of Calculations: For the effective implementation of sustainable materials, it is essential to develop automated systems that can account for not only initial costs but also long-term operational benefits. The introduction of such systems would enable designers and cost estimators to accurately forecast savings in building operation, including reductions in heating, cooling, maintenance, and current repair costs.

Development of Technical Specifications for the IT Sector: A crucial step for implementing automation is the creation of clear technical specifications for IT engineers who will develop such software solutions. These systems should include functionality for calculating both initial expenses and long-term savings, as well as visualizing this data in the form of tables and diagrams, making the decision-making process easier for construction companies.

Practical Application and Benefits for Construction Companies: The development and implementation of software tools for cost estimations that consider long-term benefits of sustainable materials will become an essential tool for construction companies and designers. These tools will help not only reduce ongoing operating costs but also increase property values, due to their environmental sustainability and energy efficiency.

Support from Government and Industry Initiatives: To accelerate the transition to sustainable building solutions, it is crucial to provide government and industry support, including subsidies, tax incentives, and other forms of encouragement for construction companies using eco-friendly technologies. This will reduce initial construction costs and stimulate the use of sustainable solutions.

For an effective assessment of the long-term economic benefits of using sustainable building materials, it is necessary to develop a specialized module within cost estimation programs that will account for not only initial expenses but also the entire spectrum of operational costs over the building's lifecycle. This module should include functionality for automated life cycle costing calculations, as well as integration with up-to-date databases on the cost of eco-friendly materials, their durability, energy efficiency, and repair frequency. Additionally, it should provide real-time information on government incentives and programs in a particular region using artificial intelligence.

A key element of this tool will be the ability to visually present data—through graphs, charts, and comparison tables—allowing users to dynamically see how resources are saved, maintenance costs decrease, and overall project profitability increases over time. This visualization is critical for decision-making, especially when convincing investors, clients, and regulatory bodies of the feasibility of choosing sustainable solutions. Implementing such visual tools also contributes to the development of a more transparent and reasoned justification system for project decisions, thus expanding the practice of sustainable construction in both the private and public sectors.

Ethical approval was not required in accordance with current legislation, as the research did not involve human or animal participation, nor did it use personal data.

Implications for Industry Practice:The results confirm that integrating an automated calculation module accounting for sustainable materials into existing cost estimation systems can become a powerful tool to stimulate the transition to environmentally friendly technologies. Particularly important is the capability for timely updates of price databases and technical specifications, allowing the calculations to adapt to rapidly changing market conditions.

Challenges and Future Directions:Despite the positive potential, the implementation of automated systems faces several challenges, including the need for data standardization, ensuring data accuracy and currency, as well as creating user-friendly interfaces for users without deep technical knowledge. It is advisable to conduct pilot implementations of the developed methodology on real projects, followed by an analysis of practical effectiveness and algorithm refinement.

Our results align with previously published studies demonstrating the economic benefits of sustainable materials, but emphasize the importance of developing specialized tools to account for them in cost estimates. Despite technological capabilities, organizational and cultural barriers—such as lack of knowledge and short-term business orientation—remain significant obstacles to widespread adoption. Meanwhile, increasing demands from clients and regulatory bodies motivate stakeholders to shift toward sustainable solutions. A key area for future research is the development of comprehensive models that consider environmental and social benefits, as well as integration with advanced digital technologies, which will improve the accuracy and transparency of assessments. It is also recommended to carry out pilot projects involving real construction companies to test the effectiveness of the proposed systems and reduce risks during scaling.

Clinical Trial Statement

Clinical trial registration: Not applicable. This manuscript does not report the results of a clinical trial.

Ethics Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable. Consent for publication: Not applicable. Ethics, Consent to Participate, and Consent to Publish declarations: Not applicable.

Author Contributions

D.S. conceived the research, conducted the data analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

References

- Suhamad, D.A.; Martana, S.P. Sustainable building materials. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 879, 012146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firoozi, A.A.; Firoozi, A.A.; Oyejobi, D.O.; Avudaiyappan, S.; Saavedra Flores, E. Emerging trends in sustainable building materials: technological innovations, enhanced performance, and future directions. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.; et al. Engineered living materials for sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 2349–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tazmeen, T.; Mir, F.Q. Sustainability through materials: a review of green options in construction. Results Surf. Interfaces 2024, 14, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; et al. Conversion of waste into sustainable construction materials: a review of recent developments and prospects. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahia AK, M.; Rahman, M.M.; Shahjalal, M.; Morshed, A. Sustainable materials selection in building design and construction. Int. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 1, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, A.; Kamal, M.A. Energy efficient sustainable building materials: an overview. Key Eng. Mater. 2015, 650, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Khan, D.; Zahoor, M.H. Empowering sustainable construction through advanced strategies for energy-efficient green building materials. Archaeol. Anthropol. Open Access 2024, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yoon, J.; Kim, K.-H. Critical Review of the Material Criteria of Building Sustainability Assessment Tools. Sustainability 2017, 9, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekung, S.; Odesola, I.A.; Oladokun, M. Dimensions of cost misperceptions obstructing the adoption of sustainable buildings. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekung, S.; Odesola, I.A.; Oladokun, M. Dimensions of cost misperceptions obstructing the adoption of sustainable buildings. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, E.C.; Sofolahan, O.; Omoboye, O.G. Assessment of barriers to the adoption of sustainable building materials (SBM) in the construction industry of a developing country. Front. Eng. Built Environ. 2023, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gounder, S.; Hasan, A.; Shrestha, A.; Elmualim, A. Barriers to the use of sustainable materials in Australian building projects. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammadi, A.; Ellk, D.S. Identifying barriers to the use of sustainable building materials in building construction. J. Eng. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 22, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kineber, A.F.; Othman, I.; Famakin, I.; Oke, A.E.; Hamed, M.M.; Olayemi, T.M. Challenges to the Implementation of Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Sustainable Construction Projects. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, R.; Bilec, M.M.; Gokhan, N.M.; Needy, K. The economic benefits of green buildings: a comprehensive case study. Eng. Economist 2006, 51, 259–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azazga, I. Economic benefits of sustainable construction. ( 2019. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S. Sustainable construction: analysis of its costs and financial benefits. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. 2016, 3, 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerainghe, A.S.; Ramachandra, T. Economic sustainability of green buildings: a comparative analysis of green vs non-green. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeganeh, A.; McCoy, A.P.; Reichard, G.; Schenk, T.; Hankey, S. Green building and policy innovation in the US Low-Income Housing Tax Credit programme. Int. J. Housing Policy 2020, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, A.S. Governmental incentives for sustainable building development – Saudi Arabia. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 16, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, B.; An, G. Do government subsidies induce green transition of the construction industry? Evidence from listed firms in China. Buildings 2024, 14, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuizugbo, I.C.; Oyeyipo, O.; Lahanmi, M. Barriers to the adoption of sustainable construction. (2020). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341814520_Barriers_to_the_Adoption_of_Sustainable_Construction.

- Mogaji, I.; Mewomo, M.; Bondinuba, F.K. Assessment of barriers to the adoption of innovative building materials (IBM) for sustainable construction in the Nigerian construction industry. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024, 32, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikyema, G.A.; Blouin, V.Y. Barriers to the adoption of green building materials and technologies in developing countries: The case of Burkina Faso. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 410, 012079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.R.; Mijan, A.-A.; Partha, A.G.; Islam, M.T.; Redwan BM, S.; Hasan, M. Bridging the gap: BIM, data analytics, and digital twins in construction life cycle management. In 7th International Conference on Civil Engineering for Sustainable Development (ICCESD 2024), Khulna University of Engineering & Technology, Bangladesh (Feb. 2024).

- Crowe, J.H. Architectural advocacy: The Bullitt Center and environmental design. Environ. Commun. 2019, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graczyk, A.M. Implementation of sustainable development in the city of Heidelberg. Acta Univ. Lodziensis, Folia Oeconomica 2015, 2, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, E.; Jussila, J.; Häyrinen, L.; Lähtinen, K.; Mark-Herbert, C.; Toivonen, R.; Toppinen, A.; Roos, A. Unlocking success: key elements of sustainable business models in the wooden multistory building sector. Front. Sustain. 2024, 5, 1364444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemm, A.; Wiggins, D. Sustainability of natural stone as a construction material. In Sustainability of Construction Materials (Woodhead Publishing, 2016), pp. 283–308. [CrossRef]

- Abushanab, A.; Alnahhal, W. Life cycle cost analysis of sustainable reinforced concrete buildings with treated wastewater, recycled concrete aggregates, and fly ash. Results Eng. 2023, 20, 101565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-G.; Wang, R.-J.; Lo, S.-C.; Yau, J.-T.; Wu, Y.-W. Construction cost of green building certified residence: A case study in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.C.; Moore, E.W.; Mario, C. The impact of green building certifications on real estate value and environmental performance. Sustainability, 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385659415_The_Impact_of_Green_Building_Certifications_on_Real_Estate_Value_and_Environmental_Performance.

- Alagöz, M. Comparison of certified “green buildings” in the context of LEED certification criteria. AEA Journal, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Amoruso, P.; Caragnano, A.; Zito, M. Green real estate: Does it create value? Financial and sustainability analysis on European Green REITs. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2018, 13, 80–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalaei, F.; Jrade, A. Integrating BIM with green building certification system, energy analysis, and cost estimating tools to conceptually design sustainable buildings. Electron. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2014, 19, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwodo, M. , Anumba, C. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Workshop on Computing in Civil Engineering ( 2017. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, K.; Pierott, R.; Hammad AW, A.; Haddad, A.N. Sustainable material choice for construction projects: A life cycle sustainability assessment framework based on BIM and fuzzy-AHP. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Repair frequency for sustainable vs. conventional materials.

Table 1.

Repair frequency for sustainable vs. conventional materials.

| Construction |

Years of operation |

| 1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

| Using sustainable materials |

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

R |

|

|

|

R |

| Using conventional materials |

|

R |

|

R |

|

R |

|

R |

|

R |

|

R |

Table 2.

Key parameters used in the hypothetical case study comparing conventional concrete and concrete with recycled additives.

Table 2.

Key parameters used in the hypothetical case study comparing conventional concrete and concrete with recycled additives.

| Parameter |

Conventional Concrete |

Concrete with Recycled Additives |

| Cost per 1 m³ |

$120 |

$135 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m·K) |

1.7 |

1.1 |

| Service Life (years) |

50 |

60 |

| Maintenance Frequency |

Once every 10 years |

Once every 15 years |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).