1. Introduction

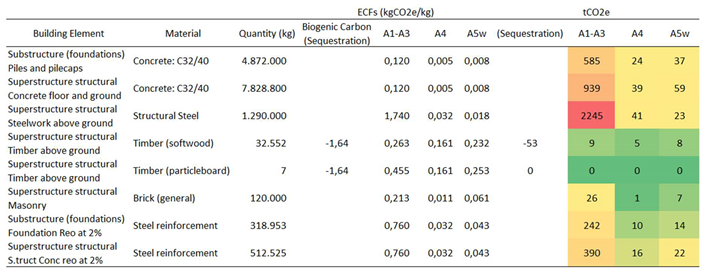

Like many organisations, Our World Data publishes emission data by countries online. It shows that over the last thirty years, the carbon emissions in China have grown from 2.4 to 11.4 metric billion t per year, a staggering 431.08% growth. This means there is rising from 2.05 to 8.85 metric tons of CO2 per capita per year. Although the UK has achieved a nearly 50% reduction dropping from 10.2 to 5.0 metric tons of CO2 per capita per year. Its overall impact remains relatively small on a global scale due to its smaller population. Despite the efforts of countries like the UK, the sheer scale of China’s emissions, which total approximately 11.4 billion metric tons—33 times that of the UK and double that of the US—demands urgent and comprehensive action from China (

Figure 1). Without immediate measures to curb this rapid growth, the global efforts to mitigate climate change will be significantly undermined.

While globally the construction industry contributes around 39% of worldwide CO2 emissions each year [

1], Chinese superscale construction accounts for approximately 50.9% of total carbon emissions as it transformed both the natural and economic landscape in the country [

2]. Industrial buildings play critical and multiple roles in a society, from shaping the economic, technological, cultural, and social fabric of society, to contributing to its growth, development, and resilience. They are designed for a certain lifespan, and once their roles diminish at the end, they face two options: demolition or renovation. From the view of social sustainability, industrial buildings, although obsolete many of them form an important and visible part of cultural heritage and a source of socio-economic development. In addition, from the view of reducing overall energy consumption, and carbon emissions, renovation is often preferable to the demolition of the obsolete old and the construction of a completely new one [

3].

Renovating industrial buildings presents a complex challenge, far more intricate than constructing new structures. The unique characteristics, quality, and potential weaknesses of these old buildings must be meticulously analyzed to ensure that their architectural, cultural, and social values are not overshadowed by the apparent advantages of cost, simplicity, energy efficiency, and business performance. This complexity extends to the assessment of Embodied Carbon (EC), which is often disregarded due to the difficulties involved in calculating it for older structures. Industrial heritage buildings, with their distinctive structures, may even result in higher EC compared to other types of historical buildings. Therefore, a systematic approach or supportive tools are essential to guide the assessment process, balancing the competing demands of energy efficiency, environmental impact, technical and economic performance, and the preservation of social, cultural, and historical significance.

The urgent need to incorporate Embodied Carbon Emissions (ECE) assessment is especially critical in the world’s largest and most populous countries, such as China and India, where reductions in carbon emissions can have a significantly larger global impact compared to smaller nations like the UK. These countries, due to their vast industrial bases and rapid urban development, have substantial potential to influence global carbon footprints through their renovation practices. Within this global context, the UK, as a pioneer of industrialization, has accumulated extensive experience in repurposing its industrial heritage over the past two centuries, successfully integrating ECE considerations. In contrast, China, with its rapid urban expansion, has left behind numerous obsolete industrial structures. However, the country is still in the early stages of developing sustainable renovation practices, often neglecting ECE, leading to environmentally inefficient outcomes. India, while a few steps behind China, faces similar challenges as it embarks on its own industrial renovations.

This paper aims to argue for the inclusion of EC in the renovation process of obsolete industrial buildings, by analysing a wide range of studies from three countries, China, India & the UK. The argument is structured around the following objectives:

Objective 1—To show the urgency of carbon emissions by reviewing the specific issues in China and India, the representatives of the BRIC countries.

Objective 2—To identify what is missing and understand why EC is not included in renovations of industrial buildings in developing countries by examining developed countries.

Objective 3—To estimate the proportion and value of EC with the total life cycle in renovations of industrial buildings for the case studies and overview the benefits of considering embodied carbon inclusion in renovations of industrial buildings.

Objective 4—To establish the issues in the assessment process of renovation options that exclude embodied carbon in the UK and China by four case studies.

2. Methods

This study was carried out in two literature reviews and one study case. The 1st review was to identify what is missing and understand why EC is not included in renovations of industrial buildings in China, the major one in the BRIC countries and most importantly the largest carbon emitter. It started from examining the challenges in China as a fastest growing economic giant and the largest carbon emitter. The 2nd review was conducted over the papers reporting the renovation projects of industrial buildings that included EC in their processes. Reviewing these pioneering projects revealed the carbon emission details, which were used as solid evidence for our argument. The case study was carried out and carefully selected two cases in China and the UK respectively to understand why EC was missed out in the renovation development. Finally, an estimation of carbon emissions was conducted using of the cases, to show the proportion of EC over the entire life cycle of the building.

The scope of this study was limited to the role of carbon assessment in the decision-making at the design stage of renovation development of an industrial heritage building. It did not consider other factors such as historical values, economic benefits and so on. Also, it considered all the common measures in building conservation as renovation, including restoration, retrofit, refurbishment, adaptive reuse and so on.

2.1. Terminology

In this study, there are three key terms that need to be explained as follows:

Refurbishment and renovation: a “modification and improvement to an existing building in order to bring it up to an acceptable condition” [

4].

Sunk cost: the embodied energy and environmental impacts associated with creating a building that has already been ‘spent’ in the past, which are considered irretrievable and irrelevant for future actions [

5].

Analogous new construction: new structures designed to be similar to or comparable to existing buildings in terms of style, function, or context. These buildings aim to harmonise with their surroundings or pay homage to architectural traditions while incorporating modern construction techniques and materials.

2.2. Quantitative Comparison

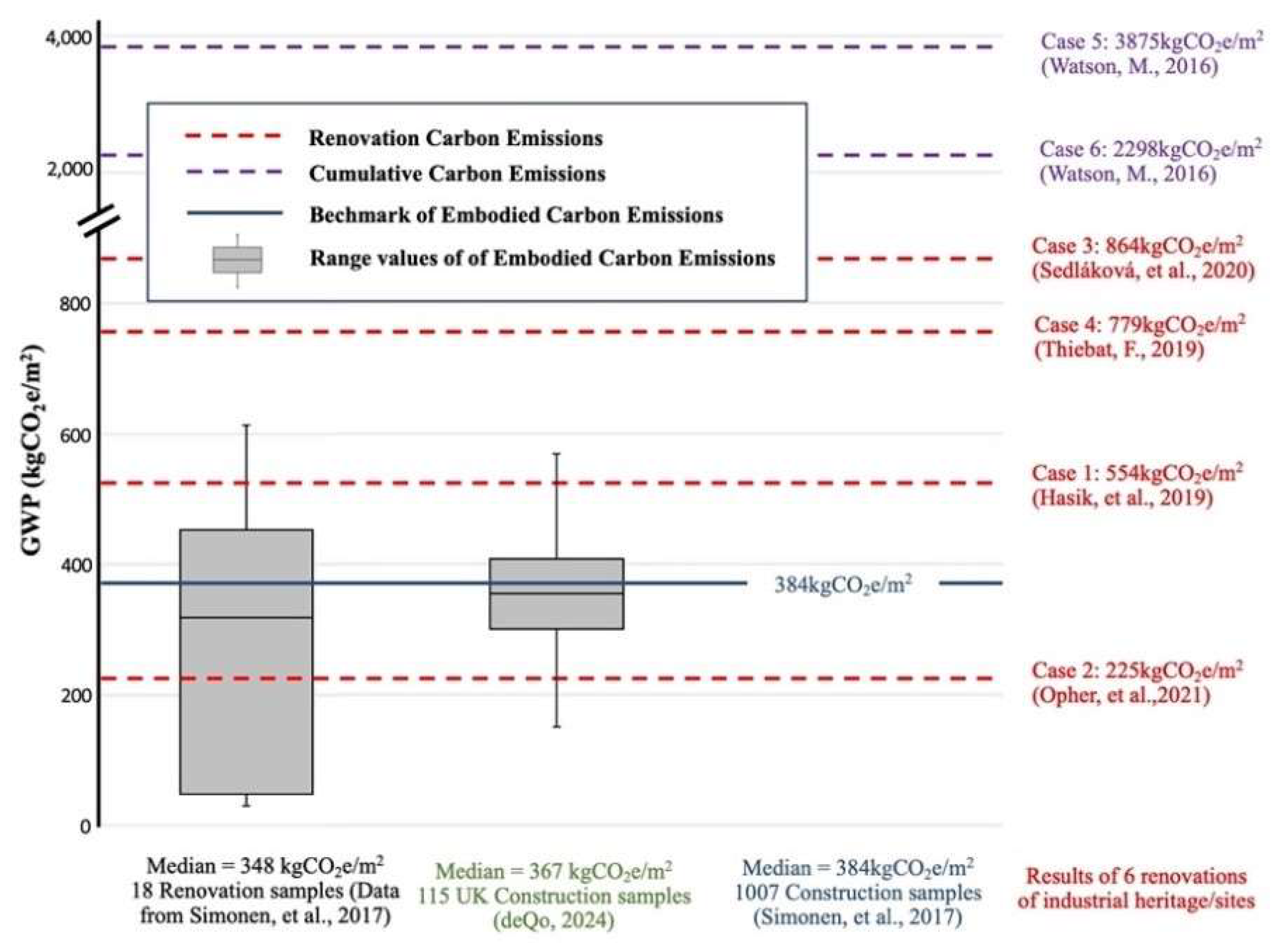

The comparison was based on two units, embodied energy and embodied carbon emissions. The compared data was collected from publicly accessible datasets (deQo), published LCA studies, EC benchmarks, as well as published embodied carbon reports, especially renovations of industrial buildings, as shown in Figure 3. The minimum criteria for inclusion in the comparison database were the reporting of building area and embodied carbon or energy impacts. In addition, the reference unit applied for presenting the embodied carbon emission of the buildings is CO2 equivalent per m2 gross floor area (expressed in kg CO2e/m2) because it can support making the comparison between different building structures possible and other published embodied carbon values of buildings from different databases and literature. Below is an explanation of the data collection sources and calculation methods used for the dataset.

1. Renovation Carbon Emissions (only renovation process):

∙ 17 data points of renovation cases were collected from the database of CLF Embodied Carbon Benchmark Research and the data points were used to create a box plot.

∙ A box plot of embodied carbon data based on 115 building samples in the UK was collected from the database of embodied Quantity outputs (deQo)

∙ Other data points and benchmarks were collected from published LCA studies.

2. Cumulative Carbon Emissions (including Sunk Cost, Demolition, and Analogous New Construction):

∙ Two data points of renovations of industrial heritage in the UK were estimated based on embodied energy. Conversion from embodied energy to embodied carbon is based on the “electricity grid” (ref). EE is more stable than EC, as the carbon intensity is dropping due to the recent effort on emission reduction in many countries, especially in the UK.

3. Using embodied energy (EE) alongside of embodied carbon EC:

The embodied energy was also used in the comparison across projects completed at different periods because the carbon intensity changes due to collective effort to make energy greener but manufacturing processes for construction materials and embodied energy remain relatively stable [

6]. This stability enables consistent long-term benchmarking as embodied energy values are similar across different periods.

Embodied carbon (EC), on the other hand, is more effective for comparing different renovation options within the same project, because, the environment, energy sources, conditions are more consistent, making it simpler to standardise and compare across options against benchmarks. According to the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) and other industry sources, typical embodied carbon emissions for new office buildings are approximately 500-1,000 kgCO₂e/m². This range can vary based on building materials and construction techniques. Best practice targets for low-carbon office buildings aim for lower values, often around 300-600 kgCO₂e/m², which are achieved through applying sustainable materials, efficient construction practices, and innovations in design.

2.3. Embodied Carbon Estimation

In this study, the Structural Carbon Tool—version 2, developed by The Institution of Structural Engineers (IStructE), was used to estimate the embodied carbon emission of cases in the UK and China. This tool supports legislation by UK Parliament to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 and is aligned with BS EN 15978[

4], BS EN 15804[

7] and RICS Professional Statement Whole life carbon assessment for the built environment[

8], they are based on ISO 14040 [

9]and ISO 14044 [

10]standard. These are two reasons for choosing the tool to estimate embodied carbon emissions:

The tool could be used to compare the embodied carbon emission of multiple design options.

The tool and the Chinese Standard for building carbon emission calculation are both based on ISO 14040 and 14044, and the tool allows the addition of custom data provided by supplier Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs), so the tool was used to estimate the renovation projects in China in this study.

The estimation has four steps including the goal and scope of assessment, inventory analysis collection, and impact assessment results and interpretation of the case study. The estimation provides a model for future studies comparing the environmental impacts of renovation options in decision-making while also highlighting the benefits of renovation over new construction.

2.3.1. Goal and Scope of Comparative Assessment

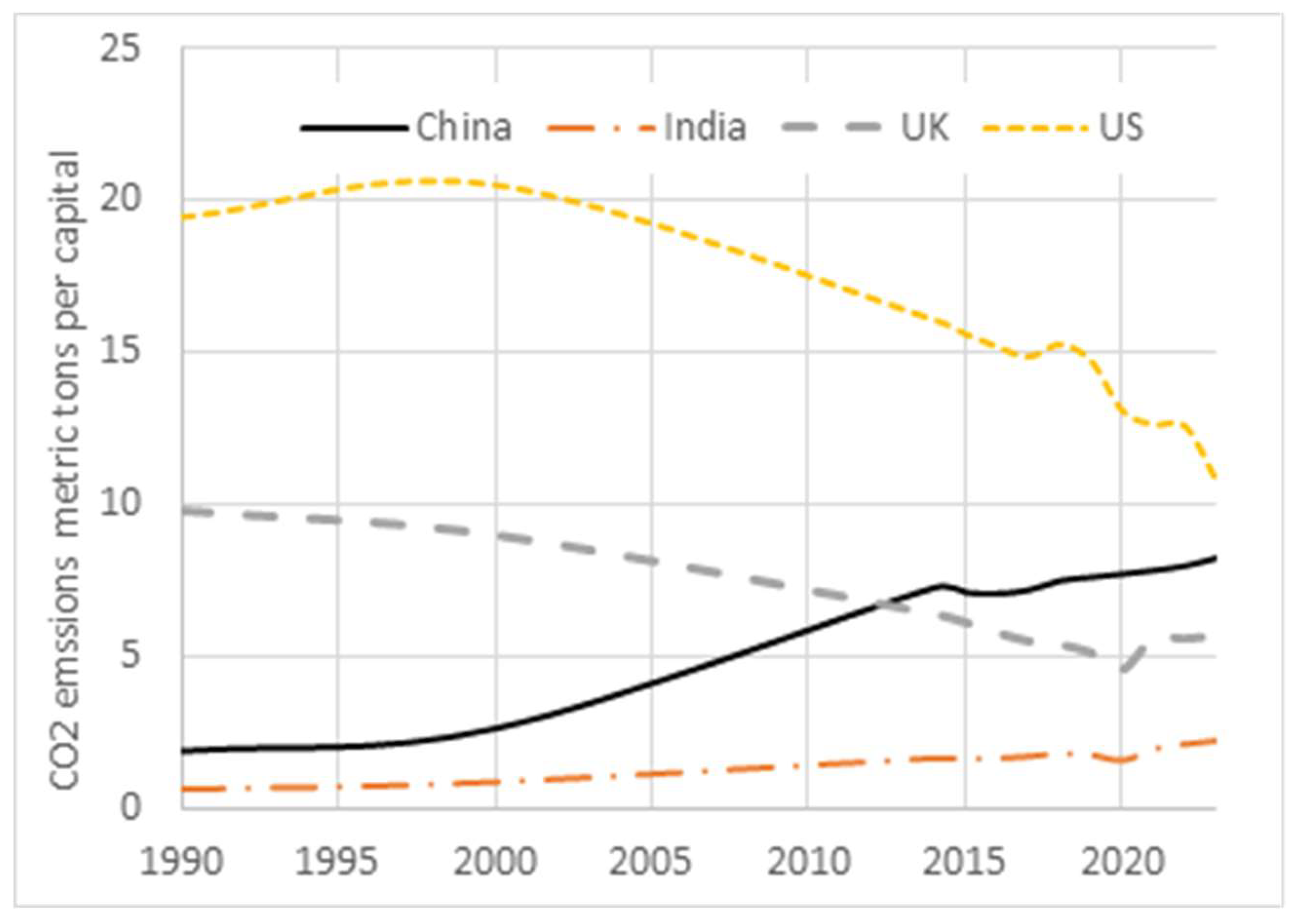

The primary goal of this life cycle assessment is to estimate the embodied carbon emissions of a building renovation project and compare the embodied carbon impacts of renovation option to analogical newly construction option. The study evaluates three cases: Coal Drop Yard in the UK, Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier and Nanshi Power Station in China. Each case has a different scope of building life cycle stages and modules but they all based on ISO 14040 life cycle assessment framework (

Figure 2), which is defined in their respective overviews. These variations in scope arise due to differences in life cycle stages and building systems, and the availability and quality of data for each project.

2.3.2. Inventory Analysis

Firstly, the renovation building was modelled using SketchUp software, creating a 3D model that encompasses both the existing and new groups of the building. SketchUp is a powerful and cost-effective solution for projects in the design stage, and it is particularly popular in the world. The existing group of the building was modelled based on the original architectural documents, while the new group was modelled based on the components added during the renovation, adhering to the actual dimensions and specifications required for construction. The model was subsequently updated manually based on on-site inspections, comparisons to the latest design documents, and communications with the lead architect for the renovation project. This update included geometrical adjustments of individual components and the definition of the components’ materials during the design stage.

Secondly, the Quantifier plugin for SketchUp was employed to assign the building components and materials within the model. This plugin automates the calculation of quantities for individual components and materials, such as volumes, areas, lengths, and amounts. The data can then be exported by the plugin in formats like CSV or Excel.

Thirdly, the Structural Carbon Tool—version 2 was used to match LCA data with the exported material data quantified by the plugin to build a core model of life cycle inventory for assessing environmental impacts in the next step. For case in the UK, the EPDs of materials in the project were used in the database of the tool. For cases in China, the EPDs of materials in the projects were used predominantly Chinese EPDs or industry averages for China based on the Chinese standard GB/T 51366-2022 and put them into the custom data of the tool.

The study considered two types of options: renovation option and analogous new construction option. These required results from the core model of life cycle inventory corresponding to two different groups of the project:

Existing group (i.e., the original structure and fabric in the existing building)

New group (i.e., elements added during renovation)

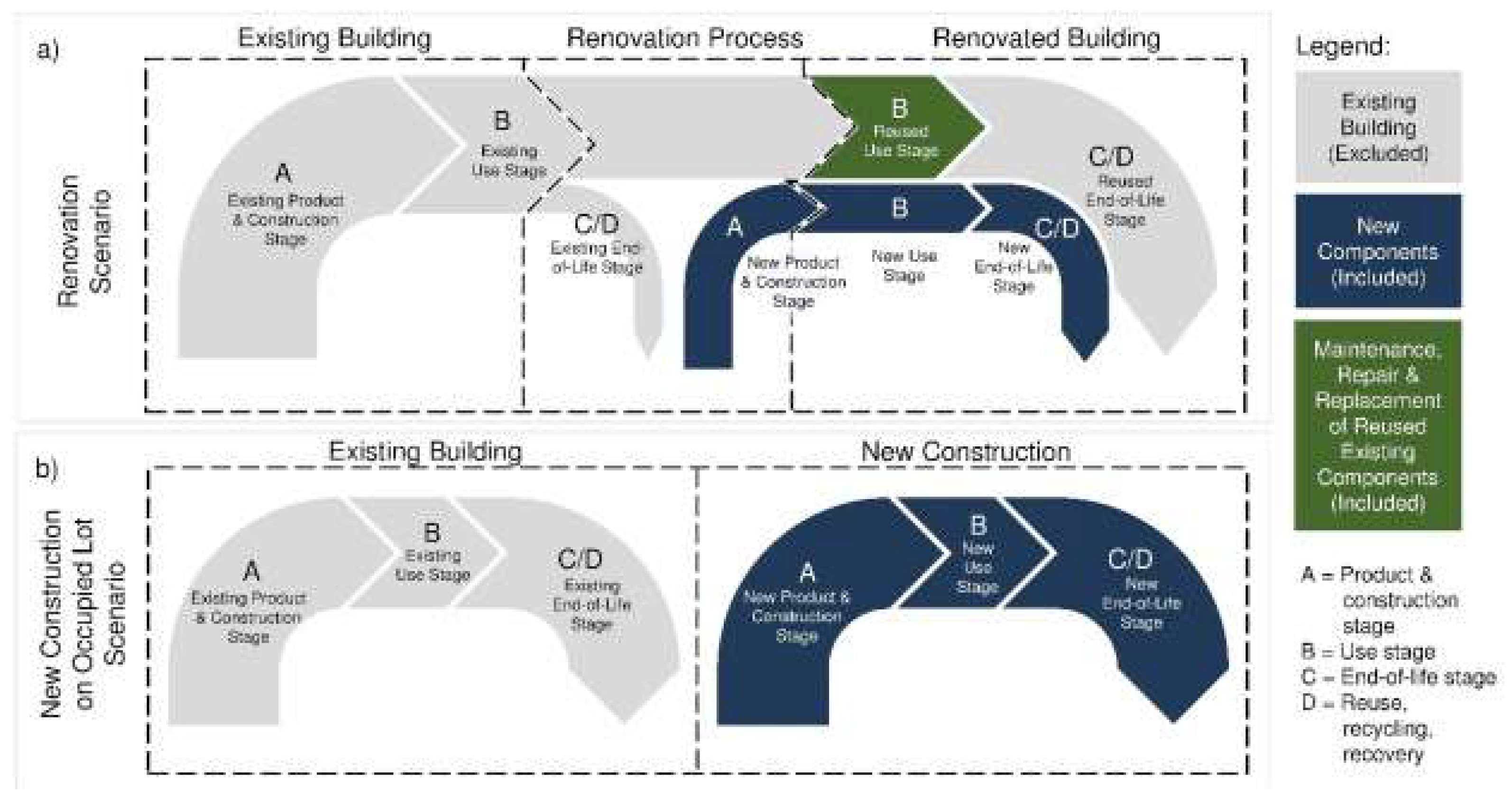

The comparison between renovation and new construction was based on the scope (shown in

Figure 3) developed by Hasik, Vaclav, et al. [

11]. This scope was created by selectively combining relevant stages for both the new construction and renovation options. Environmental impacts associated with the renovation option were calculated by combining all life cycle stages of the newly added components in the new group. Environmental impacts associated with the new construction option were calculated by combining results from both the existing group and the new groups of the project and including all life cycle stages.

2.3.3. Impact Assessment

The Structural Carbon Tool—version 2 calculated embodied carbon impacts based on the Life cycle Material Data or Custom Data. The analysis highlighted differences in environmental impacts of renovation option and new construction option for these cases.

3. Results

3.1. Challenges in China and India

With the continuous improvement of the urbanisation level after the reform and opening-up since the late 1980s in China, two challenges, building conservation and environmental conservation, are becoming prominent in the sustainable development of the built environment in the country. Firstly, building conservation is an essential part of sustainable development in a country. As an ancient civilisation, China enjoys a wealth of heritage buildings, and the government of China has conducted a lot of efforts in conserving and protecting those heritage buildings. Since 2000, the number of registered immovable cultural properties soared from 300,000 to 760,000 based on China’s Third National Heritage Site Inventory, lasting four and one-half years [

12]. Especially those cultural buildings, such as old temples, palaces, pagodas etc., have received great attention and have taken good care of them. Despite considerable efforts that have been made, problems exist in the conservation of heritage buildings in China due to four main reasons as follow: lacking a clear definition of heritage buildings, lacking funds, wrong use of technologies and materials for repair and maintenance, and unnecessary facilities were added into heritage buildings [

13]. Comparatively, industrial buildings in China have a much shorter history, less than a century, and have just begun to join those well-recognised ancient buildings and be considered as national heritage. Significantly, as an emerging industrial country, the conservation of industrial heritage buildings in China is recognised as a challenge with significant importance [

14].

Secondly, urbanisation in China, as it has happened in those industrial countries, creates increasing pressure on environmental conservation, especially in energy consumption, and carbon emissions are increasingly concentrated in urban areas. The carbon emissions of the urban building sector in China experienced a continuous growth trend from 521.5 million tons in 2000 to 1464.0 million tons in 2015, increasing approximately twofold with an average annual growth rate of 7.12% [

15]. In addition, according to the International Energy Agency [

16], global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2018 increased to 33.1 Gt, while China contributed 9.5 Gt, accounting for 28.7%. Under such pressure, in September 2021, the Chinese government pledged to the world at the United Nations General Assembly to achieve carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 [

17]. Controlling urban carbon emissions will be the key to achieving the ‘Dual Carbon’ goals. Therefore, urban redevelopment actions must focus on green, low-carbon and high-quality development in the years ahead in China.

3.1.1. Urban Regeneration and Industrial Heritage/Sites Conservation in China

With the process of urbanisation and industrial restructuring since entering the 21st century, Chinese urban planning is in a transition period from sprawl development to infill development [

18] Significantly, the redevelopment of industrial land is one of the most important and remarkable works of infill development because industrial land accounted for more than 20% of urban construction land in 2013 in many cities such as Shanghai, Guangzhou, Qingdao, etc. [

19]. Moreover, in the latest Shenzhen master plan (2022-2025), among the around 95 km2 of land for urban regeneration, the redevelopment of industrial lands accounts for around 50% (Planning and Natural Resources Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality, 2022).

In addition, following the process of de-industrialisation in Chinese urban, an incomparably larger number of abandoned industrial buildings and sites have accumulated within a short period of time that are facing an uncertain fate and await new use or demolition. Amongst these industrial buildings, industrial heritage/sites were retained and conserved because of its significant historical and cultural value. A study consisted of a survey over 6 data sources and fieldwork to identify 1537 Chinese industrial heritage sites and made them into the ‘Chinese List of Industrial Heritage Sites’ [

20]. In addition, 1272 of the industrial heritage/sites had not been redeveloped or conserved in this list, accounting for about 83% of the total [

20].

In sum, in the period of infill development in China, the regeneration of industrial lands will become the main subject for achieving sustainable development in many cities, and a large number of industrial heritage/sites are waiting to be conserved and redeveloped.

3.1.2. Embodied Carbon Reduction in China

Global warming is one of the greatest challenges in environmental conservation in the world. In 2015, the Paris Agreement set the goal of holding the global warming level below 1.5–2 °C [

21]. China has been the largest carbon emitter and second largest economy in the global, and hence has set the ‘Dual Carbon’ goals as its national target to meet the challenge and commit to the Paris Agreement. In China, carbon emissions from the construction industry represent the second-largest amount of emissions in the entire country [

22,

23]. Significantly, some studies demonstrated that the building sector has much greater carbon reduction potential than the industry and transportation sectors [

24]. Therefore, reducing carbon emissions in the building sector in China is critical.

The life cycle carbon emissions of individual buildings can be divided into operational and embodied emissions. Historically, the operational stage of a building was the main contributor to its life cycle carbon emissions, which was responsible for 80–90% of emissions in residential and office buildings [

25]. To this end, the standards and regulations in the building sector have often focused on carbon mitigation in the operation stage, with little focus on the embodied carbon from buildings [

26]. For example, design strategies that concentrate on reducing operational carbon have become common standards for new building construction, yet the potential of low embodied carbon has not been paid equal attention to the same extent [

27]. As a result, limited research on embodied carbon dioxide is a barrier to a comprehensive assessment of the carbon impacts in the construction industry. In addition, due to research efforts and advanced technologies, the total carbon emissions from operational energy to buildings are decreasing over the years. However, the contribution of embodied carbon to the total life cycle carbon emissions of buildings is increasing, especially in low-energy and nearly zero-energy buildings have been noticed by scholars [

28,

29]. Therefore, leading engineers have emphasised the urgent need for a global, standard method to estimate embodied carbon dioxide in the building sector [

30].

In China, an emerging industrial country, roughly 50% of the total carbon dioxide emissions in the building sector in 2015 were accounted for by the annual embodied carbon dioxide for the following three reasons. Firstly, rapid urbanisation in China is the source of increasing embodied carbon dioxide in the building sector [

31]. Secondly, buildings in China generally have a shorter average lifetime, about 33.8 years in 2015, than those in developed countries [

32]. A shorter building lifetime means embodied carbon emissions account for a more significant proportion of the whole life cycle in a building. Thirdly, there is insufficient time to develop a mature guide or standard for embodied carbon reduction as them in developed countries because most guides and construction standards are evolving as the industry progresses.

In sum, as operational energy emissions in use fall, embodied carbon will become the main subject for achieving sustainable development. Embodied carbon emissions account for a large proportion of total emissions in the building sector in China. Therefore, reducing embodied carbon emissions is crucial to developing a low-carbon construction industry in China.

3.1.3. Complexity of Conservation in Industrial Heritage in India

Similar to China, India has a rich architectural heritage spanning its socio-cultural and geographical contexts. The Indian AMASR Act [

33] lists 3,679 nationally important monuments managed by the Archaeological Survey of India. India also has several World Heritage Sites, including the Mountain Railways of India, an Industrial Heritage [

34]. State Governments and cities have additional heritage listings, though these primarily serve conservation purposes [

33]. India’s industrial heritage, influenced by pre- and post-colonial history, reflects the impacts of 19th and 20th-century industrialisation and urbanisation.

Since Independence in 1947, India’s urbanization and construction industries have expanded significantly. Tipnis and Singh have highlighted the need to recognize industrial heritage from both industrial and post-industrial eras, per the Nizhny Tagil Charter for The Industrial Heritage [

35,

36]. Indian industrial heritage spans three eras: Colonial (1700-1947), post-Independence (1947-1991), and post-liberalization (1991-present). Additionally, Gupta has also noted the limited listing of industrial heritage buildings in India, despite INTACH’s efforts on expanding such listing [

37]. Cities like Mumbai, Calcutta, Chennai, and Delhi, with rich industrial heritage, face urbanization pressures that threaten these sites [

35].

Industrial heritage in India often lacks independent protection under monument-centric laws, leading to potential demolition rather than reuse. Overlapping jurisdictions, ownership issues, multiple stakeholders, and privatization pressures further complicate management [

35]. Adaptive reuse is typically undertaken by private owners, with notable examples like Alembic Industrial Heritage in Vadodra and Soro Village Pub in Goa [

38].

3.1.4. Sustainable Policies and Guidelines in India

India’s heritage sector is monument-centric, while environmental and climate policies are sectoral and independent of heritage conservation. This results in a policy gap compared to developed nations. Despite sector-specific strategies and the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) from 2008 [

39], emissions continue to rise, threatening India’s 2070 Net Zero goal [

40]. Rapid urbanization and construction demand contribute significantly to emissions. India has developed green building certifications like LEEDS, IGBC, and GRIHA, and the Energy Conservation Building Code (ECBC) for new constructions. However, guidelines for heritage buildings’ energy performance are lacking. The Bombay House, a privately managed headquarters of the TATA group, is the only heritage building with a platinum IGBC rating [

41]. Unlike China, India lacks policies recognizing the value and embodied carbon of industrial heritage sites, despite their potential. This issue has to be addressed sooner than later in assessing Heritage Buildings and their performance.

3.2. Decision Making Process in Renovations

The projects reported in the published papers seemed to suggest a difference in the main environmental factors that were considered in the decision-making for the renovation of industrial heritages/sites between developed and developing countries. The consequent increase in the embodied carbon significance of renovation buildings has resulted in developed countries focusing on the whole life carbon or embodied carbon assessment of the renovation of industrial heritage/sites. Although the renovation of industrial heritage/sites has been increasing for more than 20 years in developing countries such as China, there are still differences in the environmental factors that were considered in the decision-making between developed and developing countries as follows three main sections.

Interestingly, our UK case study shows that EC was only considered qualitatively in general but not quantitatively using any calculation tools, because of mainly uncertainties in historical data, material conditions, and evolving construction practices. A key engineer from ARUP emphasised the importance of accurate, comparative material assessments, including all supplementary materials, to ensure fair evaluations. Budget constraints often challenge sustainability commitments, but early integration of embodied carbon considerations can enhance assessment accuracy and sustainable outcomes, as advised by the City of London Corporation’s Carbon Options Guidance.

3.2.1. From the Perspective of Environment-Related Policies

Many developed countries have considered the whole life carbon and embodied carbon in their building regulations as below. For example, in the UK, according to Policy SL 2 in The New London Plan, Whole Life Carbon (WLC) emissions, including operational and embodied carbon emissions, should be calculated for each project via a life-cycle assessment (LCA) and the actions taken to reduce WLC emissions should be demonstrate [

42]. This criterion is mandatory for major developments, dwellings where ten or more are to be constructed or all other uses where the floor space will be 1000 m2 or more. In the Netherlands, new residential and office buildings over 100 m2 and extensive renovations must have an environmental cap for whole-life energy and carbon emissions, which includes embodied impacts, in their building regulations [

43]. In Singapore, Building & Construction Authority (BCA) has operated the Green Mark green building rating system since 2005. It is mandatory for all projects over 2,000 m2 (cite). Therefore, in many developed countries, most renovations must be conducted whole life carbon or embodied carbon assessment because almost industrial heritage/sites have massive floor areas and volumes.

In China, in the past ten years, the government has proposed many plans, policies, and regulations for the renovation of existing buildings, such as the general code for maintenance and renovation of existing buildings [

44], retrofitting existing buildings, applying more renewable energy, and strengthening building energy-saving management [

45,

46]. However, these policies mainly promoted the energy efficiency of building operations. Although carbon assessment was mentioned in the assessment standard for green retrofitting of existing buildings [

47], it only gave a “promotion and innovation” point (1/100) when design teams performed carbon assessment. Moreover, it did not give detailed information about embodied carbon. Therefore, compared to the developed countries, China and other developing countries lack mandatory whole-life or embodied carbon assessment criteria in environment-related policies.

3.2.2. From the Perspective of Green Building Rating Systems & Their Evolutions

Many developed countries have studied and established sustainability-based assessment systems for buildings, considering their construction characteristics [

48]. The relatively complete and mature green building assessment systems include LEED, BREEAM, CASBEE, GBC, NABERS, Eco Profile, and ESCALE [

49,

50]. However, China is relatively late in researching assessment systems for green buildings. In 2004, it implemented the Assessment System for Green Building of the Beijing Olympics [

51]. In 2006, it implemented the Assessment Standard for Green Building (ASGB), which was revised in 2014 and 2019. Although some of the assessment indicators in the ASGB could be used in assessing the reuse of old industrial buildings as civil buildings, others are not appropriate for this application and diverge from reality. Therefore, compared to the developed countries, China and other developing countries lack a complete, systematic, and applicable sustainability assessment system for reused industrial buildings [

52]. From the majority of building types such as offices to special types such as historical building renovations. Providing the years to show the slow evolution of these guides in contrast to the quick development of a similar one in China.

3.2.3. From the Perspective of Sustainability Assessment Methods

In developed countries, four studies have included embodied carbon emissions as an indicator in the renovation of industrial heritage/sites. In current literature, several researchers have conducted life cycle assessments, focusing on embodied carbon, to analyse the environmental impact of the renovation of industrial heritage to support carbon reduction or offsetting of the project [

11,

53,

54,

55]. In addition, Watson conducted an embodied carbon assessment using the embodied energy calculator for three heritage industrial renovation projects across two regions to judge the environmental value of building reuse[

56].

In China, the renovation of industrial heritage/sites has been increasing for more than 20 years, and various aspects of corresponding research have also emerged. From the choice of renovation mode of historic industrial sites, at the level of planning. Li, Xiao-Dan, et al. investigated the eight industrial sites in the suburbs of Beijing and built a suitability evaluation index system based on the environment-economy-society conceptual framework to evaluate the priority of renovation mode selections in decision-making [

57]. From the multi-criteria assessment method of industrial heritage/sites, at the level of buildings. Tian, Wei, et al. established a multi-criteria method with 26 indicators based on the environment-economy-society conceptual framework for assessing the sustainability of reused industrial buildings in China [

52]. Fan et al. summarised the key indicators, preconditions, and guaranty factors for the reuse potential of historic industrial buildings and estimated the future value added to the project through a multi-criteria assessment of the reuse potential. From the environmental assessment method of industrial heritage, at the level of the individual building [

58]. Kai Zhang and Yueyan Li conducted a life cycle assessment for the renovation of historic industrial buildings in the operational carbon part to provide experience in reducing carbon emissions for similar projects [

59].

Although many scholars have studied sustainability assessments for renovating industrial heritage sites, focusing on environmental impacts such as air pollution, energy efficiency, and operational carbon, these studies have not included embodied carbon as a key indicator in China. Consequently, unlike developed countries, China and other developing nations lack a sustainability assessment method that incorporates embodied carbon for industrial heritage sites.

A review of projects suggests there are three main gaps when considering environmental factors in the decision-making process for renovating industrial heritage sites in China and other BRIC countries:

The absence of mandatory whole-life or embodied carbon assessment criteria in environmental policies.

A lack of a comprehensive, systematic, and applicable sustainability assessment system.

Rare consideration of whole-life or excluding embodied carbon in existing sustainability assessment methods.

Embodied carbon has been included in renovation assessments in developed countries, where pioneering projects have set valuable examples to follow. Although China is still classified as a developing country by itself, its rapid development, large population, and numerous heritage sites create an urgent need for renovation efforts. As China positions itself as a leader among BRIC countries, it must act responsibly and promptly as the largest carbon emitter. Including embodied carbon assessments in renovation projects is a crucial step towards comprehensive emission reduction.

3.3. Proportions and Values of Embodied Carbon

The following analysis in two parts are to demonstrate the noticeable embodied impacts in renovations of industrial buildings in terms of the proportions and values of embodied carbon based on the literature review. The overview of the proportions focused on collecting and estimating proportions of embodied carbon in all types of buildings including new and renovated buildings, especially renovations of industrial buildings.

The first part focused on collecting and estimating values of embodied carbon emissions (ECE), including renovations of industrial buildings, available medians of benchmarks and the range values of renovations based on the literature review. The second part focused on comparing these values to demonstrate the noticeable embodied impacts in renovations of industrial buildings.

3.3.1. The High Proportion of EC in Renovations of Industrial Buildings

For all types of buildings, a life cycle carbon emissions review over 251 cases for both refurbished and newly built buildings, including a wide range of building types, shows that the embodied, operational and demolition carbon emissions are, on average, respectively 24%, 75% and 1%, of the life cycle total [

60]. Another review of the life cycle energy use in buildings in 73 cases for residential and office buildings across 13 countries shows that the embodied impact use ranges from 10—20% of the total and operating 80–90% [

25].

For renovation types of buildings, a life cycle assessment of a residential building shows the proportion of embodied carbon emissions, from 12% to 26%, for energy refurbishment in different options [

61]. Another life cycle assessment of residential buildings shows that the average proportion of embodied carbon emissions is about 17% for eight deep energy renovation case projects [

62]. In addition, a life cycle assessment of a heritage building shows that the proportion of embodied carbon emissions is about 7% for a heritage building after restoration and refurbishment [

63].

However, for renovations of industrial buildings, embodied carbon is often shown to account for a higher proportion than in the above types of buildings. First, a life cycle assessment of a listed brickworks renovation shows that the proportion of EC could be 38.7% (based on the reported data) of total carbon emissions in a deep energy-saving renovation proposed option [

53]. Second, a life cycle assessment of an old mill renovation shows that the proportion of EC is about 42.1% (based on the reported data) of total carbon emissions [

54]. Third, a life cycle assessment of a listed industrial complex renovation shows that the proportion of EC might be 84.3% (based on the reported data) of total carbon emissions in an energy-saving renovation proposed option with biomass system and air handling unit [

55].

In sum, although the proportion varies in a wide range, from 7% to nearly 85%, the proportion of EC is a significant part of the total emission in all types of buildings. It is even so in renovation projects of industrial buildings, especially when low-carbon technologies are applied in building operations after completion. This part will continue to grow as advanced systems & technologies are developed and applied to further reduce operational carbon emissions.

3.3.2. The High Values of EC in Renovations of Industrial Buildings

In part one, for renovations of industrial buildings/sites, an overview of results on embodied carbon emission for renovations of industrial buildings with general information is shown in

Table 1. Hasik, et al. conducted a life cycle assessment on a listed American beer bottling plant renovation and reported that the embodied carbon value is 554 kg CO2e/m2 (based on the reported data) throughout the building’s lifetime [

11]. Opher, et al. carried out a life cycle assessment on a Canadian listed brickworks renovation and reported that the embodied carbon value is 255 kg CO2e/m2 throughout the building’s lifetime [

53]. Sedláková, et al. conducted a life cycle assessment on an old mill renovation in Slovakia and reported that the embodied carbon value is 864 kg CO2e/m2 (based on the reported data) throughout the building’s lifetime [

54]. Thiebat conducted an Italian listed industrial complex renovation assessment and reported that the embodied carbon value, 779 kg CO2e/m2 (based on the reported data) in a proposed option throughout the building’s lifetime [

55]. Watson calculated the embodied energy for two UK renovation projects of industrial heritage in Europe to demonstrate the benefits of including embodied impacts in renovation projects and reported the cumulative embodied carbon value might be 3,875 and 2,298 kg CO2e/m2 respectively (estimate based on the report data) [

56]. The cumulative embodied carbon includes the sunk cost, demolition, and analogous new construction for the renovation projects.

In the table. 1, the embodied carbon emission data for renovation cases (1, 2, 3, 4) were collected and estimated from the 4 LCA studies. The cumulative embodied carbon emission for renovation cases (5, 6, marked with *) were estimated by total embodied energy data that collected from the one study. Both cases were built around 2010, so the carbon intensity of UK grid in 2010 was approximately 0.134kgCO2/ MBTU. The two projects saved respectively 24.5K and 7.8K metric t carbon emissions.

The embodied carbon benchmark calculation was based on the median values calculated the results of three former studies (

Figure 4). In Simonen’s case, the quarter upper and lower quartiles of the embodied carbon of the 26 renovations (only 17 valid data) are 51 and 496 kgCO2e/m2 respectively, and the median value is 348 kg CO2e/m2 (based on the reported data) [

64]. In deQo’s case, a more recent embodied carbon analysis, the embodied carbon outputs of the 115 buildings are 315 and 419 kgCO2e/m2, and the median value is 367kgCO2e/m2 [

65]. Another study of Simonen et al. on embodied carbon benchmark demonstrated a median value of 384 kg CO2e/m2 over 1000 buildings, including 26 renovations [

66].

In part two of this study, we compared the data above against the results of the values of the other 6 cases we examined closely (red and purple dotted lines), the median values from the databases (blue full lines), and the range values of 17 renovation buildings (Grey box) and range values of 115 buildings (Grey box) are both shown in

Figure 4. The comparison of the embodied carbon values reveals three facts as follows.

Firstly, the two values of Cases 5 and 6 are significantly higher than of those all others. This is because the values represent the cumulative embodied carbon emissions, which include the process of existing building (sunk cost), demolition and new construction. It means that renovation can avoid a lot of environmental impacts over new construction, especially for industrial building because high embodied energy is often locked into heavy construction of industrial buildings [

56]. Secondly, the three values of case studies (No.1, 3 and 4) are obviously higher than 348 kgCO2/m2, the median value of the 18 renovation projects. They are also higher than the median value obtained from the database of embodied Quantity outputs containing 115 samples in the UK [

65] and the median value obtained from the largest known database of building embodied carbon containing over 1000 samples [

66]. Thirdly, the median value of the 18 renovation projects is lower than the median values obtained by deQo and Simonen et al., and the first quartile of the 18 renovation samples is the lowest value of all data. It means that embodied carbon emission in common renovation buildings is lower than all types of buildings. This is because that building reuse almost always reduces the environmental impacts over demolition and new construction [

5]. Fourthly, the values of embodied carbon in industrial building renovations are significantly higher than the median level, except in case 2, where a series of low carbon measures were applied to achieve zero emissions. These measures include the reuse of existing materials and structures, selection of lower-carbon materials purchased from local sources, installation of renewable energy systems, natural lighting and improved thermal insulation of the building’s envelope, as well as developing a carbon offset strategy [

53].

In sum, the analysis of the proportion of embodied carbon shows that the proportion of embodied carbon is a significant part of the total emission in all types of buildings, especially in renovations of industrial buildings. The analysis of values of embodied carbon shows, firstly, renovations of industrial buildings can avoid a lot of environmental impacts over new construction because of their heavy construction with high embodied carbon already invested and demolition. Secondly, the values of embodied carbon emissions are high in most renovations of industrial buildings, although they have opportunities to be reduced by low carbon measures. In addition, a consensus has emerged from the literature that the contributions of embodied carbon during the buildings life cycle carbon emissions have been increasing. Therefore, embodied carbon is a significant component in the total emissions, especially in industrial buildings, and has to be considered in renovation decision-making.

3.3.3. The Benefits of Considering Embodied Carbon Inclusion in Renovations of Industrial Buildings

The renovation of existing buildings, particularly historical industrial structures, is gaining increasingly attention as a key strategy for sustainable development, aiming at reducing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions while preserving local heritage, in those developed countries, such as Canada, USA and other. In the UK, specific practices and guidelines have been developed to support sustainable renovation with a focus on both operational and embodied carbon. UK policies mandate the calculation of embodied impacts for any proposed demolition projects, ensuring that environmental costs are fully accounted for across a building’s entire lifecycle. Regulations require demonstrable reductions in whole-life impacts before permitting demolitions, thereby promoting the retention and adaptive reuse of buildings.

Martin (2015) highlights best practices in the UK, demonstrating significant embodied energy savings through adaptive reuse and careful development. Tower Mill, Hawick, Scotland: Originally a wool spinning mill, it was converted into small business premises, a café, and a cinema. The project saved approximately 36,932,314 MBTU/4,948K kg CO2e by retaining and repurposing the structure. Another example, Bonnington Bond, Leith, Scotland: a complex of former whisky warehouses and a sugar refinery was transformed into offices and residential spaces, resulting in significant energy savings and reduced carbon emissions of about 117,840,000 MBTU/15,791K kg CO2e.

4. Case Studies

4.1. UK Case—Coal Drops Yard

4.1.1. Overview

The Coal Drops Yard project involved the regeneration of a Victorian heritage site in King’s Cross, London[

67]. The project successfully preserved historical elements while adapting the buildings for modern use, including retail spaces and public areas. The restored site has since become a lively urban destination, contributing significantly to the overall regeneration of King’s Cross.

Arup, in collaboration with Heatherwick Studio, aimed to blend heritage conservation with modern design. The ambitious structural and architectural goals emphasized sustainability and the preservation of historical features. Originally built in the 1850s as warehouses for storing coal delivered by train, the site had fallen into disuse and was repurposed over the years for various functions, including nightclubs and offices. A significant fire in the 1980s, along with subsequent exposure to the elements, caused extensive damage, necessitating careful restoration and structural reinforcement.

Originally, the site consisted of warehouses built in the 1850s to store coal delivered by train. Over time, the buildings fell into disuse and were repurposed for various functions, including nightclubs and offices. A significant fire in the 1980s and subsequent exposure to the elements caused extensive damage, necessitating careful restoration and structural reinforcement.

While the project made efforts to retain and reuse existing structures, specific calculations or assessments of embodied carbon were not explicitly detailed. The primary drivers for the project appeared to be three aspects:

1. Preservation factors: emphasizing the conservation of historical elements, the project aimed to retain the site’s character and cultural significance such as:

∙ Original Victorian brickwork and ornate ironwork were preserved and repaired.

∙ Original timber floors were restored where possible.

2. Economic factors: the redevelopment aimed to create a commercially viable space that could attract businesses and visitors, contributing to the local economy.

3. Social factors: creating a vibrant public space that integrates into the community, promoting social activities and interactions of the area.

All the above highlights a gap in the integration of embodied carbon considerations in decision-making processes for heritage projects, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive and methodical evaluation of the total carbon emissions associated with the structure throughout its entire lifecycle.

4.1.2. Embodied Carbon Estimation

The Coal Drops Yard’s project took several years to complete, during which many aspects changed significantly. Calculating the embodied carbon of the original structure is particularly challenging. If the project were undertaken today, the embodied carbon of the foundations and new structures would need to be reassessed.

In the feasibility stage, precise calculations are difficult, so estimations are often used. However, in the concept stage, detailed reports are prepared to present design options to the client, compare alternatives, and include embodied carbon assessments. This process requires accurate and time-consuming design work, which is why size estimates are typically used initially.

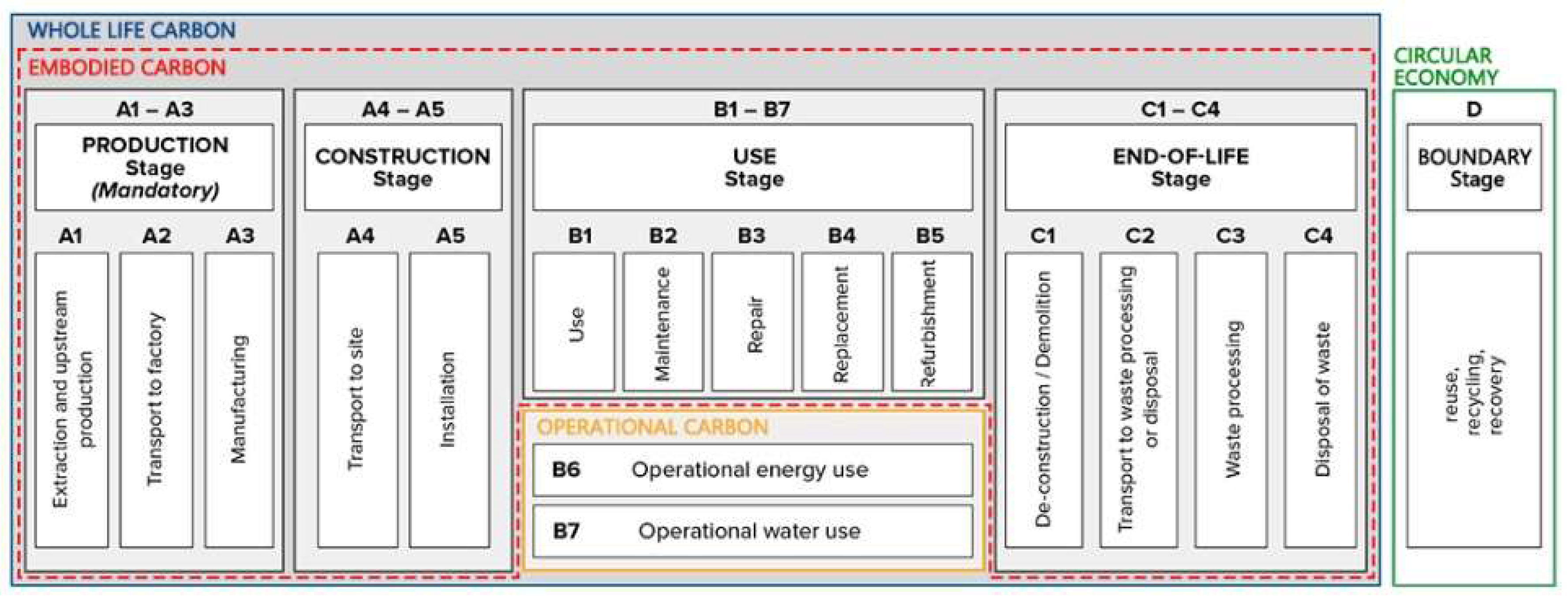

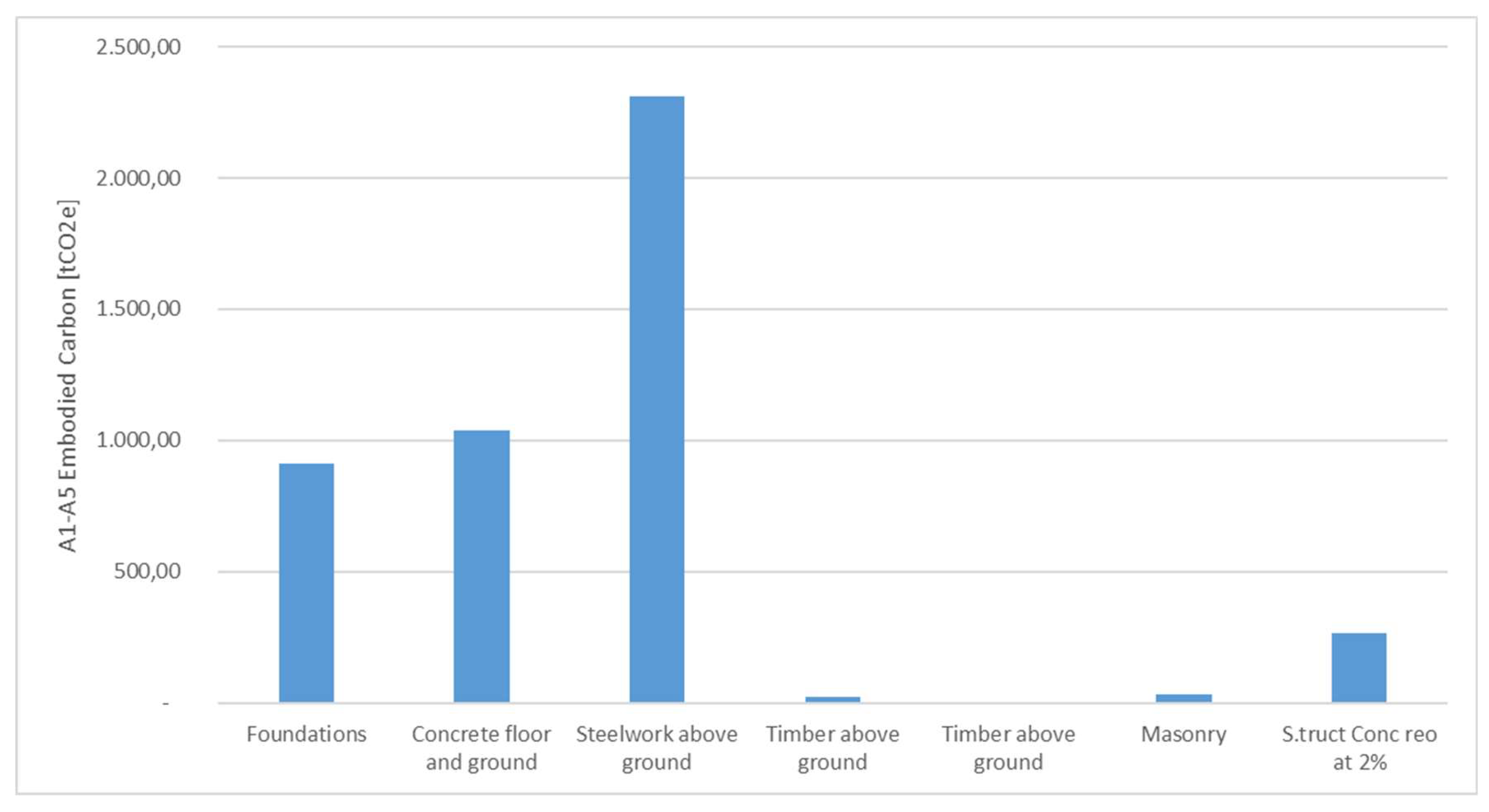

The below figures represent all the quantities of the new structure together with their respective carbon factors and the embodied carbon values:

Table 3.

Embodied Carbon and tCO2e for Building Elements (The total embodied carbon for the materials listed for phases A1-A5 is 4742 tCO₂e. the results are coloured with intensity from green to red).

Table 3.

Embodied Carbon and tCO2e for Building Elements (The total embodied carbon for the materials listed for phases A1-A5 is 4742 tCO₂e. the results are coloured with intensity from green to red).

Figure 6 presents the A1-A5 Embodied Carbon (tCO2e) for different construction components. Created for easier visualization, the chart helps identify where attention needs to be focused. It is evident that the new added structure—steel roof creates an outstanding architectural feature but the steelwork above ground raises the embodied carbon, indicating a need to prioritize alternative materials or construction methods, especially for the new sculptural pitched roof. While concrete and foundations are not as impactful as steelwork, these areas still offer significant opportunities for carbon reduction through improved material choices and construction techniques as well.

Considering the Gross Internal Area (GIA) of 13500 m² [

67], the embodied carbon values are 351 kgCO2e/m² (A1-A5)

The SCORS (Structural Carbon Rating System) chart helps place these values in context, rating the structural embodied carbon from A++ (best) to G (worst) [

70]:

The EU’s goal is to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, marking an economy with zero net greenhouse gas emissions [

71]. This objective is a key aspect of the European Green Deal, supported by the laws outlined in the European Climate Law. To achieve this target, all future building projects post-2050 must comply with rigorous embodied carbon limits.

Comparison of the embodied carbon for two options shows 785kgCO2e/m2 if we build a new structure but only 351kgCO2e/m2 when we renovate the old one. Although the Coal Drops Yard failed to meet the EU target, it saved about 5,852 tons of carbon emissions by retaining the existing building. This means that the renovation option reduces about 55% of the embodied carbon emissions compared to the new construction option.

4.1.3. Learning from the Case

The Coal Drops Yard project illustrates the potential environmental benefits that could have been realized if embodied carbon had been considered during the design and renovation process. The analysis revealed that the choice of materials, especially for the roof, contributed substantially to the overall embodied carbon. Had EC been a factor in the decision-making process, alternative, lower-carbon materials and design strategies might have been selected, resulting in a more sustainable outcome.

This case study supports the recommendation that future renovation projects should incorporate embodied carbon assessments from the earliest stages of design. By doing so, projects can optimize material choices and construction techniques to minimize their carbon footprint. In addition, it also demonstrates the benefit of renovation option over new-construction one by showing the potential carbon reduction. Policies should be developed to require EC considerations in renovation projects, incentivizing sustainable practices and promoting a comprehensive approach to urban development that balances heritage conservation with environmental sustainability.

4.2. UK Case—University of Nottingham Castle Meadow Campus

4.2.1. Overview

The University of Nottingham’s Castle Meadow Campus is a distinctive series of buildings, located in the west of Nottingham city centre. The campus, which was originally completed in 1994 and occupied by UK Government, has been redeveloped by the university to serve as an innovative hub for teaching, research, and community engagement. It encompasses seven buildings and offers over 32,500 square meters of space, which includes state-of-the-art facilities and a commitment to sustainability, as demonstrated by its Grade II listing in 2023 for its architectural and environmental significance.

The city of Nottingham has been recognized as one of the top 122 cities worldwide for climate action by the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), with an ambitious goal to become the first carbon-neutral city in the UK and Europe by 2028 [

72]. The University of Nottingham also aims to be carbon neutral by 2040 with offsetting and by 2050 without offsetting. It has set ambitious short-term targets for carbon reduction by 2030 and another target for 2028 to match the city’s goals. The university reports yearly on its carbon emissions to meet its internal targets [

73].

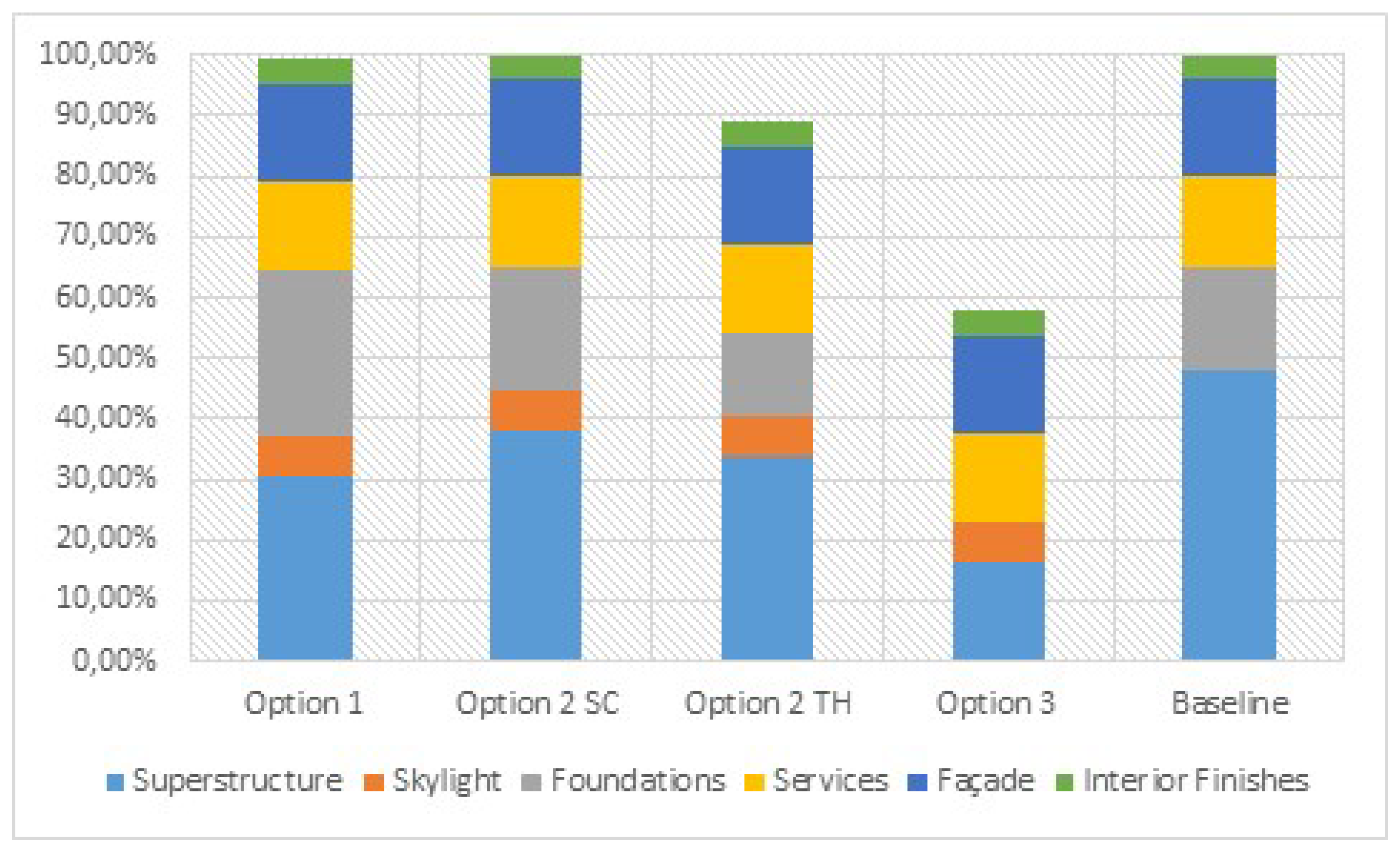

Aligned with these sustainability efforts, ARUP was involved in a structural reuse project at the University of Nottingham Castle Meadow Campus, highlighting the importance of considering embodied carbon during the decision-making stage, even in non-industrial buildings. A baseline carbon budget was established to represent the carbon footprint of a hypothetical completely new build which would provide the same new gross internal floor area. This baseline served as a benchmark, with any option surpassing it potentially cancelling out the environmental benefits of retaining and repurposing the existing structure.

4.2.2. Comparative Assessment

The calculation of embodied carbon played a crucial role in selecting Option 3, which utilized a timber frame and resulted in the lowest embodied carbon compared to the other three options:

Option 1: Single concrete column and cantilevering reinforced concrete slab, in which reinforced concrete has high production energy and emissions, exceeding timber’s carbon footprint.

Option 2 SC: A regular grid of steel columns supporting composite metal deck

Steel’s energy-intensive production significantly raises embodied carbon compared to timber.

Option 2 TH: A regular grid of steel columns supporting CLT (Cross Laminated Timber) deck

While CLT has a lower embodied carbon than concrete and steel, the steel columns still contribute significantly to the overall embodied carbon of the structure, making it higher than a fully timber frame option.

This decision not only aligned with the project’s sustainability goals but also demonstrated a commitment to environmental responsibility.

Integrating embodied carbon calculations into material decisions and design choices emphasises the importance of sustainability in construction projects.

To provide clarity and support in the decision-making, the below chart (

Figure 7) was generated to compare all options, illustrating the proportion of the carbon budget allocated to various design alternatives. Through this visual representation, it became evident that Option 3, characterized by a simplified frame utilizing timber, emerged as the most sustainable choice. This option minimized the utilization of the carbon budget, aligning well with the main sustainability goals.

Concrete and Steel Options (1 and 2 SC) have similar embodied carbon values (around 405.6-408.4 tCO₂e), aligning closely with the baseline. This indicates higher embodied carbon typical of heavy construction materials.

On the other side, timber Options (2 TH and 3) show reduced embodied carbon, with Option 3 being the most sustainable (235.9 tCO₂e), thanks to the utilization of timber, which generally has lower embodied carbon compared to concrete and steel.

It is important to note that, in this case, the embodied carbon (EC) of the original building is significantly lower than that of an industrial building due to its non-industrial nature and heavy construction characteristics. Therefore, using the EC baseline of a new non-industrial building as a comparison could be acceptable (despite losing the original EC used to build the building in the first place) as long as another key consideration such as operational carbon is considered. Many buildings now meet low-energy and zero-energy standards due to extensive policy initiatives, however, these standards are typically applied to modern buildings. This study, however, examines industrial buildings where operational carbon emissions may remain high. Consequently, a relevant comparison should evaluate the total EC of a new build combined with its operational carbon against the EC of refurbishment combined with its operational carbon to determine which option yields lower EC over the building’s lifetime. As in occasions, the option with the lowest original EC can end up being the highest long-term due to the inclusion of operational carbon.

4.2.3. Learning from the Case

Although not an industrial heritage site, the Castle Meadow Campus project effectively demonstrates how a single renovation project can contribute to a city’s long-term carbon reduction. It also shows how integrating embodied carbon calculations into the decision-making process can lead to more sustainable outcomes. Specifically, by comparing various structural options, the project highlighted the significant environmental benefits of using timber, which resulted in the lowest embodied carbon compared to concrete and steel alternatives. This approach aligns with both the university’s own carbon neutrality targets and the city’s ambitious sustainability goals. It underscores a shared vision for a greener future and emphasising the importance of considering both embodied and operational carbon in construction projects to achieve long-term sustainability.

In the UK, it is evident that Embodied Carbon (EC) has been integrated into all major renovation projects, whether through direct calculation or estimation using standard Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) tools. EC is consistently considered throughout the renovation development process, ensuring that the environmental impact is a central factor in decision-making. This approach reflects a national commitment to reducing carbon emissions across the building sector, emphasizing the importance of both operational and embodied carbon in the pursuit of sustainability.

4.3. China Case—Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier

4.3.1. Overview (for the Shougang Steel Mill)

(Historical and geographical description) The steel mill was established by the Beiyang Government in March 1919 as one of the earliest modern steel companies in China. Known as Longyan Steel Mill, it was located in the west of Beijing, about 17 Kilometre from the Forbidden City, the heart of Beijing, a rural area at the time and soon became one of the most important manufacturing bases in the city. It was renamed as Shougang Steel Mill, meaning Capital Steel Mill, after 1966.

(Renovation reasons) Due to urbanisation after the Open Door since late 1980’s as shown in

Figure 3, and the city government’s economic restructuring and pollution control initiatives, the whole operation was decided to be relocated to Hebei Province, completely out of the city, in 2005. Beijing 2008 Olympics as a catalyst turned the site of 8.63 km2 of prime city-centre land ready for rehabilitation and regeneration.

(Heritage values) In January 2018, the site was registered as Shougang Steel Mill Park in the ‘China Industrial Heritage List (first batch)’ by two Chinese governmental agencies: The National Academy of Innovation Strategy and the Urban Planning Society of China. The obvious reason is its role in Chinese modern history and industry.

(Transition sentence) Its value will be discussed in detail later using one case, Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier, in the park. More specifically, their renovation plans are to be analysed in the light of carbon assessment in decision-making.

4.3.2. The Issue in the Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier (ASC)—Ignoring Avoided Impact by the Existing Building

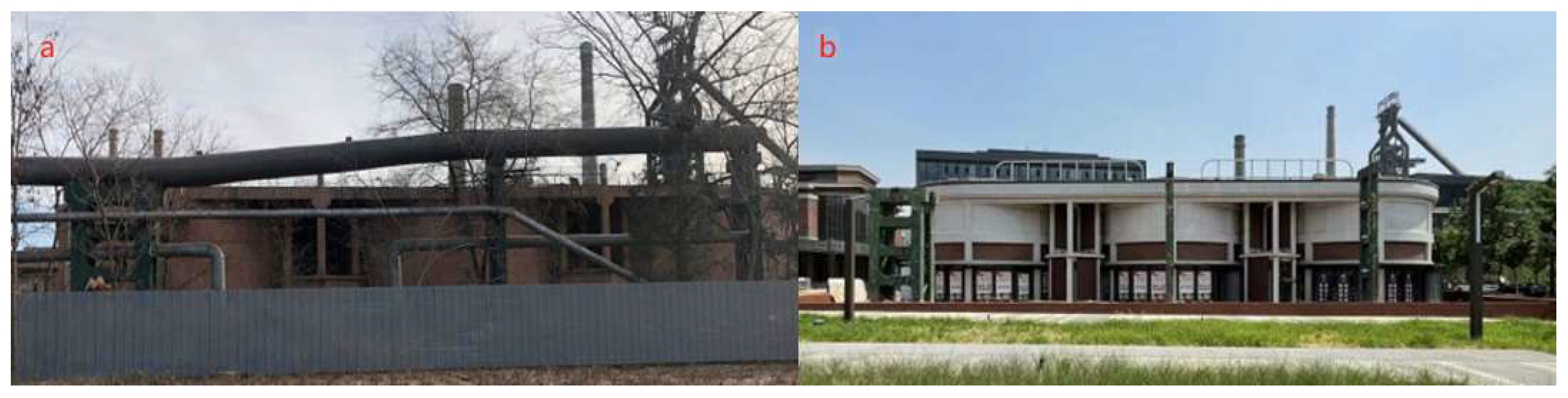

(Case location) The Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier (

Figure 8) is part of the Liugong Hui complex, the core of the northern area of the Park, between two Lakes (Qunming Lake and Xiu Lake, Figure). (2 retain reasons) The structure was considered to retain for three reasons, its original function in steelmaking, unique structure of shape and volume and relatively low cost for renovation.

First, sedimentation is a key part in the process of steelmaking, and hence a structure that facilitates this function surely becomes a visual reminder of its original use. Built-in 1975, the structure consists of three medium containers needed for the process of continuous removal of dreg by sedimentation. The special structure has always been a recognizable reminder of the original function in this complex site.

Second, the three medium concrete containers of the building created strongly attractive objects for its unconventional shape. Apart from the unique exterior, the shape of the containers was believed to be able to create an interior that is geometrically unconventional to visitors after renovation.

The third, the ground area of the building, about 300 m2, was relatively small comparing with other structures in the park so that the project team could control the renovation cost.

Therefore, the project team planned to renovate the building into an industrial-themed restaurant for the complex. However, the special structure caused the project to encounter multiple option adjustments of structural reinforcement and increased the difficulty of construction. In the end, due to the pressure of the construction progress schedule, the existing building was eventually demolished, and a new building was reconstructed to restore the original style

4.3.3. Embodied Carbon Estimation

Since the project team did not consider embodied carbon emissions as a main factor in the decision-making stage, this study estimated emissions for multiple options based on the original architectural documents and 3D model for renovation options. The project team designed three renovation options with different forms of structural strengthening to retain the structure of the existing building. It means that the main quantitative comparison is the materials of structural strengthening that used in renovation options. In addition, embodied impacts associated with the new construction option were estimated by combining results from both the existing building and newly add materials during the renovation.

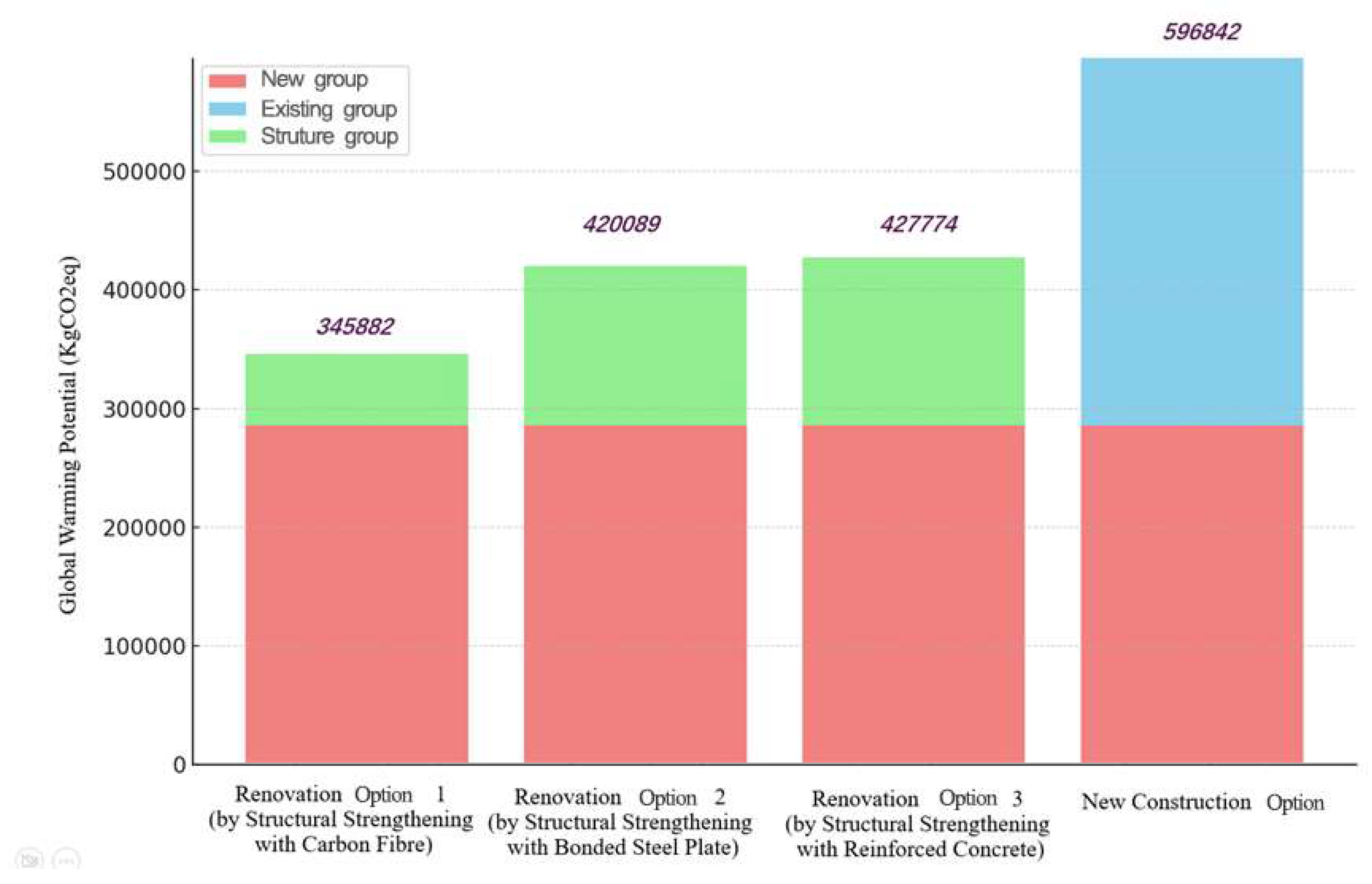

The results of the total embodied carbon emissions are illustrated in

Figure 9, which shows the total emissions for four options. The renovation options involving structural strengthening with carbon fibre exhibits the lowest total carbon emissions (346 tCO2eq), whereas the new construction scenario has the highest GHG emissions at 597 tCO2eq. The three renovation scenarios achieve a reduction of 28% to 42% in total GHG emissions compared to the new construction scenarios.

4.3.4. Case Reflection

The major argument for reusing a building is that the renovation process could minimise environmental impact by avoiding demolishing old structures and constructing new ones. This argument becomes stronger in renovation of industrial buildings, which are often constructed with heavy structures and consequently bear high embodied carbons [

56]. However, for the Accelerant Sedimentation Clarifier project, the project team did not use the avoided impact approach in decision-making to select the renovation option with fewer environmental impacts because embodied carbon was overlooked in the project. In addition, the project team was mainly in the dilemma of the cost and technology level of structural reinforcement, which delayed the progress. Embodied carbon could be considered as an indicator to help the project team make decisions because a carbon tax is already seen as having economic value in some developed countries.

In sum, despite the benefits of adaptive reuse the existing industrial building to minimize environmental impact, the project faced challenges with a tight schedule that did not allow for strengthening of the unique structure, leading to its eventual demolition and reconstruction in decision-making. This case underscores the importance of considering embodied carbon in renovation decisions of industrial building to better balance environmental, economic, and technological factors.

4.4. China Case—Nanshi Power Station, Shanghai

4.4.1. Overview

The origins of the Power Station of Art, a contemporary art museum, can be traced back to the Nanshi Electric Lighting Factory, a power station. Established in November 1897, the station was the one that powered the first light bulb in China. Hence it has a historical significance. The station was then renamed Nanshi Power Station and moved to its current location on the west bank of the Huangpu River, the south of Huangpu District in the centre of Shanghai. It became one of the most important power stations in the city.

The role of the station and its site was reconsidered after the end of the 20th century, when a large number of industrial enterprises in the inner city were closed down and relocated outside of the city as the urban functions and spatial structure evolved following the Shanghai government edicts of sustainable principles for social, economic, and environmental development [

74]. The station ended its duty of power generation in 2006, using the Shanghai World Expo as a catalyst, leaving an area of 42,000m2 of prime downtown land ready for rehabilitation and regeneration. The power station was renovated to be the Pavilion of Future at the Shanghai World Expo in 2010, and it was renovated again to be a museum and renamed Power Station of Art for a special event, the Shanghai Biennale, in 2012 (

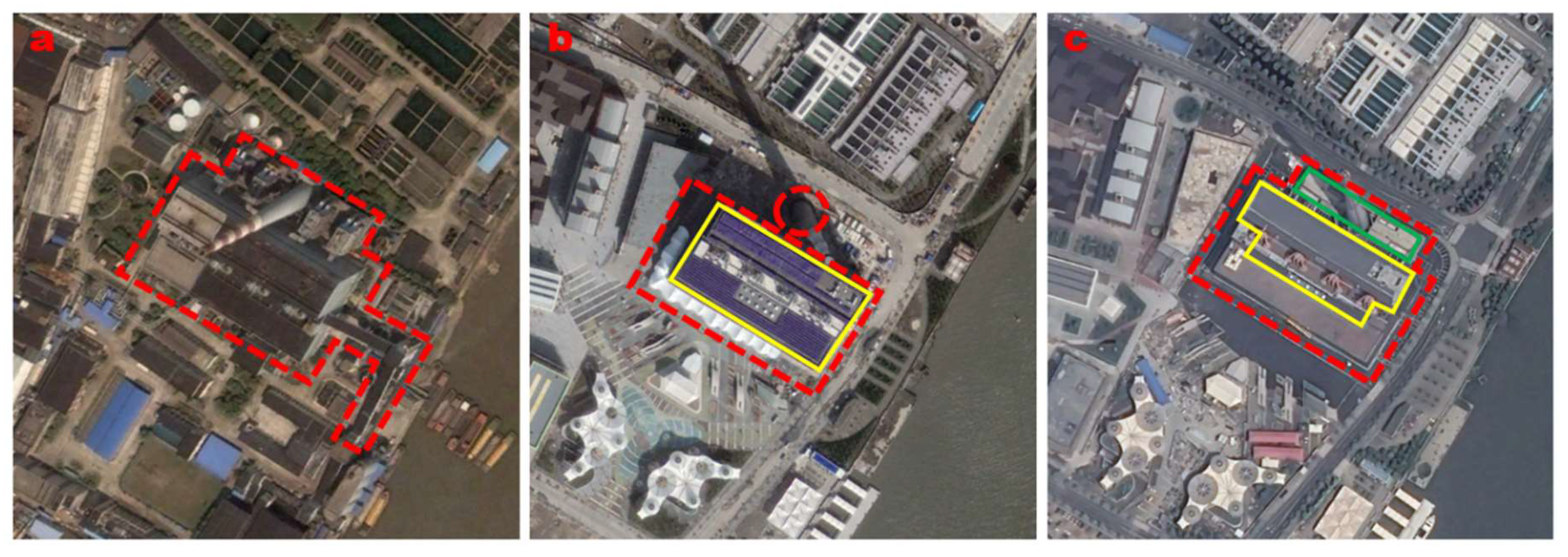

Figure 10).

In 2015, the Nanshi Power Station, the historical name of the Power Station of Art, was registered in the ‘Shanghai Historical Building List (fifth batch)’ by the city government. It was classified as a second-level industrial heritage based on an evaluation system of the industrial heritage with five values, including historical, social, economic, technological, and aesthetic value [

75].

4.4.2. The issue in the Practice of the Nanshi Power Station—High Proportion of Embodied Carbon

The original power station mainly consisted of a main building, a chimney and equipment buildings, the coal conveyor bridge, and other ancillary buildings. The main building is a reinforced concrete structure with a length of 128 m, a width of 70 m, a height of about 50 m, and a floor area of about 23,470 m

2[

76]. The station was renovated twice in 2008 and 2011(

Figure 10), respectively. In the first renovation in 2008, the original four floors of the main building were updated to eight floors, and the area was expanded to 31,088 m

2. However, the equipment room and coal conveyor bridge were demolished. In addition, the project aimed to be the first sustainable building transformed from an industrial factory in China, so insulated envelopes, solar panels, and water source heat pumps were installed to improve building energy efficiency. The solar panels were installed on the roof of the main building at elevations of 24 m and 49 m, respectively, covering around 9,000 m

2[

76]. In the second renovation in 2011, the total building area of the main building increased again to about 41,000 m

2, providing 15 different types of exhibition spaces. Significantly, the solar panels at the 24 m elevation, about 3000 m

2, were removed to create a large outdoor exhibition platform (the yellow line in

Figure 10). These short-life solar panels resulted in about 700 tCO₂e embodied Carbon emission was and not to mention their chemical pollution. In addition, a new structure, about 4,000 m2 [

77](the greenlined area in

Figure 10), was built on the site of the equipment room that was demolished in the first renovation to meet the car parking needs. Although the two renovations of the station meet the functional transformation of the building for the city, the environmental impact of embodied carbon emissions should not be overlooked for the following three reasons:

Firstly, in the first renovation, the project was renovated with a deep energy retrofit to reduce its operational carbon emissions according to the Assessment Standard for Green Building. However, without considering embodied impacts, a significant reduction in operational carbon can be offset by an increase in embodied carbon, and the sustainability of the renovation building with the lowest energy use intensity is lower than that of the building with higher energy use intensity [

62]. In addition, as operational carbon decreased in the project, the proportion of embodied carbon in the building would increase.

Secondly, the project was renovated twice in a short period to adapt to the functional changes of the building in the city, resulting in high proportion of embodied carbon in its full life cycle emissions. All solar panels at the 24 m elevation were removed to create a large outdoor exhibition platform. This practice greatly reduced the expected energy savings of solar panels for operational emissions and increased the proportion of embodied carbon emissions over their life cycle.

Thirdly, the new parking structure has a similar volume as the original building structure that was demolished in the first renovation, as shown in

Figure 10. Therefore, if the embodied carbon were considered in the first renovation, this would have reduced carbon emissions from demolition and new construction. Because renovation of industrial heritage helped avoid 75% of the embodied carbon impacts from the new construction option [

11].

In sum, despite its transformation aimed at sustainability, the repeated renovations and changes in a short period have inevitably resulted in a high proportion of embodied carbon emissions, which undermine the overall environmental benefits. Additionally, the disposal of solar panels, which contain hazardous materials such as cadmium, lead, and other toxic chemicals, poses significant environmental and health risks if not managed properly. Addressing embodied carbon impacts and the hazards of solar panel disposal in future projects is crucial for achieving truly sustainable building practices.

4.4.3. Summary on Chinese Cases

The Chinese cases of Shougang Steel Mill and Nanshi Power Station highlight the challenges of balancing historical preservation, urban development, and environmental sustainability. While Shougang Steel Mill’s renovation struggled with structural reinforcement issues, leading to its eventual demolition, Nanshi Power Station’s repeated renovations resulted in a high proportion of embodied carbon emissions, undermining its sustainability goals. These cases underscore the importance of considering embodied carbon in renovation decisions to achieve long-term environmental benefits.

5. Conclusions

Based on the views and case studies the following conclusions can be drawn.

Firstly, the urgency of addressing carbon emissions in China and India, two prominent BRIC countries, is paramount due to their vast population and rapid urbanization and consequently significant environmental impacts. Both nations face unique challenges in heritage and environmental conservation. In China, the rapid growth in urban carbon emissions necessitates a focus on green redevelopment, particularly in conserving industrial heritage sites. The high embodied carbon in construction further underscores the need for comprehensive strategies to mitigate these emissions. India’s abundant yet vulnerable industrial heritage buildings suffer from a lack of focused policies for preservation and sustainable reuse. Despite efforts in sustainable building practices, gaps remain in integrating heritage conservation with carbon reduction strategies. Both countries must urgently develop and implement cohesive policies to balance heritage conservation with sustainable urban development. Addressing these issues is critical for achieving global climate goals and ensuring sustainable growth.

Secondly, the analysis highlights significant gaps in the incorporation of embodied carbon (EC) assessments in the renovation of industrial buildings in developing countries. The developed countries, represented here by a few selected ones, mandate whole-life carbon and EC assessments through stringent environmental policies and comparison of renovation options. Developing nations like China lack such regulatory frameworks. Additionally, the absence of comprehensive and systematic sustainability assessment systems that include EC further exacerbates this issue. The lack of mature green building rating systems and the exclusion of EC in sustainability assessments are key barriers. These deficiencies stem from differing policy priorities, financial constraints, and a focus on operational energy efficiency rather than holistic environmental impacts. Developed countries provide valuable examples of integrating EC into renovation decision-making processes, demonstrating the benefits of early and thorough EC assessments. For developing countries to enhance their renovation practices, adopting similar policies and assessment frameworks is essential. Addressing these gaps will promote more sustainable renovation practices and contribute to global carbon reduction efforts.

Thirdly, the second review based quantitative comparison, on those successful examples in developed countries, demonstrates the significant benefits of incorporating Embodied Carbon (EC) considerations into the renovation of industrial buildings. Through the adaptive reuse of structures such as the Tower Mill, Bonnington Bond, and the Mulhouse Foundry, substantial energy savings and reductions in carbon emissions were achieved. These projects highlight the potential of retaining and repurposing existing buildings to enhance sustainability. Above all the proportion of embodied carbon overall is significantly high. It can reach 85% in cases where low-carbon technology or systems are running in operation after completion. This will even so as advanced systems & technologies are developed and applied to further reduce the operational carbon emissions.

The issues in the assessment process of renovation options that exclude embodied carbon in the UK and China by four case studies are concluded separately.

Analysis of the two UK cases, The Coal Drops Yard and the University of Nottingham Castle Meadow Campus projects, has revealed several key issues. First, while embodied carbon is considered in developing renovation solutions, it is often not calculated. Second, unlike operational carbon, it is not mandatory in the UK to estimate embodied carbon although it is “considered” in renovation solution development. Third, assessing embodied carbon in renovation options is challenging due to inaccurate or unavailable data for older structures. Specifically, these two case studies provide critical insights into the importance of embodied carbon in achieving sustainable building outcomes. At Coal Drops Yard, the lack of embodied carbon consideration resulted in missed opportunities for more sustainable material choices, underscoring the need for early-stage embodied carbon assessments. Meanwhile, the Castle Meadow Campus project showed how prioritizing embodied carbon—particularly by selecting timber over concrete and steel—can support both carbon neutrality targets and broader urban sustainability goals. These examples emphasise the necessity for UK renovation projects to consistently integrate embodied carbon calculations, using tools like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), to optimise material selection and reduce carbon footprints, ensuring a balanced approach between heritage conservation and long-term environmental sustainability. The analysis demonstrates the benefits of incorporating embodied carbon considerations in the renovation of old buildings, as opposed to constructing new ones.

The two Chinese case studies highlight the challenges of renovation projects that exclude embodied carbon in their assessment processes, particularly in China. Despite efforts to minimise environmental impact through adaptive reuse and sustainable transformations, the projects faced significant issues, including tight schedules that led to demolition and reconstruction, as well as repeated renovations that increased embodied carbon emissions. Additionally, the improper disposal of solar panels with hazardous materials further underscores the need to address embodied carbon and environmental hazards in future sustainable building practices.