1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition defined by persistent deficits in social communication and restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior. Recent surveillance data estimate a prevalence of approximately 1 in 54 children in the United States, underscoring both the public health significance and the clinical demand for effective interventions [

1]. Large-scale surveys have confirmed that psychotropic medication use is common in individuals with ASD, reflecting the high prevalence of comorbid symptoms such as anxiety, aggression, hyperactivity, and seizures [

2,

3]. The International Society for Autism Clinical Assessment (ISACA) guidelines and other consensus statements emphasize the importance of integrating pharmacological treatments with behavioral and educational approaches, but also highlight the absence of a single universally effective medication [

4].

The heterogeneity of ASD presentations contributes to the diversity of pharmacological strategies employed. Epidemiological research suggests that up to two-thirds of individuals with ASD are prescribed at least one psychotropic drug during their lifetime [

2,

5]. Observational studies demonstrate that antipsychotics, stimulants, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants are the most frequently used classes, though prescribing practices vary by age, severity of symptoms, and access to services [

6,

7].

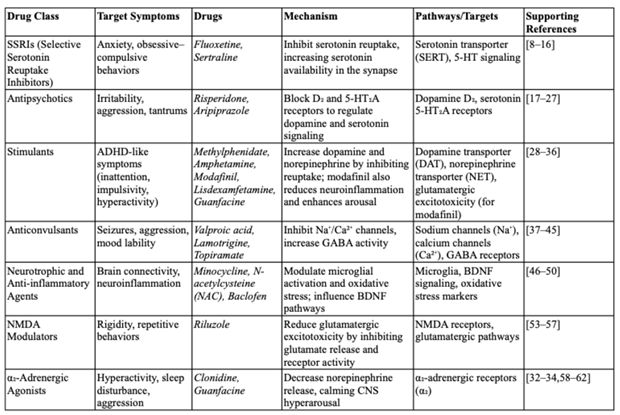

Table 1.

Mechanisms and pathways in pharmacological treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Table 1.

Mechanisms and pathways in pharmacological treatments for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

This review was undertaken to synthesize the evidence for pharmacological interventions in ASD across established and emerging drug classes. We organize the discussion by therapeutic targets, beginning with serotonergic modulation and extending to antipsychotic, stimulant, anticonvulsant, neurotrophic, immune, and glutamatergic mechanisms. In doing so, we aim to provide a comprehensive appraisal of both efficacy and safety, while also mapping areas where further research is most urgently needed.

2. SSRIs and Serotonergic Modulation

Target symptoms: anxiety, obsessive–compulsive behaviors, repetitive actions, mood dysregulation.

2.1. Mechanistic Rationale

Serotonergic dysregulation has long been implicated in ASD pathophysiology. Early neuroimaging studies demonstrated alterations in serotonin synthesis capacity in children with autism [

8]. Preclinical and translational studies further suggested that modulation of the serotonin transporter (SERT) could normalize aspects of repetitive behavior [

9]. These findings provided a rationale for the clinical use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

2.2. Clinical Evidence

Clinical evidence for SSRIs in ASD is mixed. The Cochrane review by Williams et al. [

10] synthesized randomized trials and concluded that SSRIs showed limited benefits in children but may have utility for adults, particularly in managing anxiety and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Subsequent randomized controlled trials, such as the fluoxetine study by Reddihough et al. [

11], demonstrated reductions in obsessive–compulsive behaviors in youth, though adverse effects such as irritability and sleep disturbance were more frequent compared with placebo.

Observational research highlights that SSRIs remain one of the most commonly prescribed medication classes for individuals with ASD, particularly in the context of comorbid anxiety [

12]. Jobski et al. [

2] and Coleman et al. [

3] reported frequent parental endorsement of SSRIs in large national surveys.

2.3. Preclinical Insights

Animal studies have contributed mechanistic insights. Golub et al. [

13] found that juvenile rhesus monkeys treated with fluoxetine demonstrated increased social interaction, while He et al. [

14] used metabolomic profiling to identify individual predictors of fluoxetine response, suggesting biological heterogeneity in treatment effects.

2.4. Other SSRIs

Other SSRIs such as citalopram and sertraline have been tested, though results remain inconclusive. King et al. [

15] reported that citalopram did not outperform placebo in reducing repetitive behaviors in children with ASD, while smaller sertraline trials suggested potential benefit for comorbid anxiety symptoms [

16].

2.5. Clinical Considerations

Taken together, SSRIs may alleviate specific domains such as anxiety and obsessive–compulsive behaviors, but effects on the core features of ASD remain limited. Clinical use requires careful dose titration and monitoring for adverse events such as gastrointestinal upset, behavioral activation, and sleep disturbance.

3. Antipsychotics

Target symptoms: irritability, aggression, tantrums, self-injurious behavior.

3.1. Historical Context

Antipsychotics have been used in ASD since the 1980s, when haloperidol demonstrated efficacy for reducing behavioral disturbances in children [

17]. However, the risk of extrapyramidal side effects limited long-term use. The development of atypical antipsychotics provided better tolerability and became the mainstay for pharmacological management of severe irritability.

3.2. Risperidone and Aripiprazole

Risperidone and aripiprazole are the only medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for irritability in children and adolescents with ASD. Double-blind randomized controlled trials demonstrated significant improvements in irritability, tantrums, and self-injury [

18,

19]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have confirmed these effects, with risperidone and aripiprazole consistently associated with large effect sizes in reducing irritability [

20,

21].

3.3. Other Atypical Antipsychotics

Evidence for other atypicals is mixed. Olanzapine has been studied in small case series, with some improvements in aggression but frequent weight gain [

22]. Quetiapine has demonstrated benefit in open-label studies but also caused sedation and metabolic side effects [

23]. Ziprasidone showed some efficacy in retrospective naturalistic studies, with the advantage of less weight gain but potential cardiac risks [

24]. Paliperidone, the active metabolite of risperidone, has demonstrated benefit in adolescents and young adults in small open-label studies [

25].

Clozapine remains a treatment of last resort for severe, refractory irritability and aggression in ASD. A recent scoping review described potential benefits but emphasized the need for careful monitoring of agranulocytosis and metabolic complications [

26].

3.4. Safety Considerations

Atypical antipsychotics carry notable adverse effects. Weight gain and sedation are common, and long-term use may lead to metabolic syndrome, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance [

20]. Risperidone is also associated with hyperprolactinemia. Aripiprazole appears to have a more favorable metabolic profile, though akathisia and agitation are possible [

19]. Guidelines recommend baseline and ongoing monitoring of weight, body mass index, fasting glucose, and lipid levels [

27].

3.5. Guideline Recommendations

The international guide to prescribing psychotropic medications for problem behaviors in intellectual disabilities supports antipsychotic use when severe aggression or self-injury threatens safety and behavioral interventions alone are insufficient [

6]. The consensus across clinical guidelines is that atypical antipsychotics should be reserved for severe presentations, used at the lowest effective dose, and regularly re-evaluated for continued necessity [

27].

4. Stimulants

Target symptoms: hyperactivity, impulsivity, inattention, executive dysfunction.

4.1. Methylphenidate and Other Stimulants

Methylphenidate is the most widely studied stimulant in children with ASD. Early placebo-controlled crossover trials demonstrated moderate efficacy for hyperactivity, though adverse effects were more common than in typically developing children with ADHD [

28]. The Cochrane systematic review by Sturman et al. [

29] synthesized randomized trials and confirmed reductions in hyperactivity but highlighted concerns about tolerability, including decreased appetite, insomnia, and increased irritability.

Amphetamine derivatives such as lisdexamfetamine have been evaluated in smaller studies. Case reports suggest potential benefit for comorbid ADHD symptoms but also note risk of affective lability and increased anxiety [

30]. Broader pharmacological reviews, including work by Faraone et al. [

31], emphasize the need for individualized dosing strategies in neurodevelopmental populations given heightened sensitivity to side effects.

4.2. α2-Adrenergic Agonists (Clonidine, Guanfacine)

α2-adrenergic agonists act by reducing presynaptic norepinephrine release, thereby improving hyperarousal, impulsivity, and sleep. Guanfacine has demonstrated efficacy in randomized controlled trials, improving hyperactivity and oppositional symptoms in children with ASD [

32]. Clonidine, while supported primarily by case series and smaller open-label trials, appears useful for managing sleep disturbance and hyperactivity [

33]. A systematic review by Banas and Sawchuk [

34] confirmed that clonidine can be effective for behavioral dysregulation in ASD but requires careful monitoring for hypotension and sedation.

4.3. Modafinil and Novel Approaches

Modafinil, a wakefulness-promoting agent, has drawn attention for its potential anti-inflammatory and cognitive-enhancing properties. Preclinical studies demonstrate that modafinil reduces neuroinflammation and improves autism-like behaviors in animal models [

35]. A medicinal chemistry review also highlighted structural modifications of modafinil derivatives with potential application in ASD [

36]. While promising, clinical trials in humans are lacking, and modafinil is not currently recommended outside experimental contexts.

5. Anticonvulsants

Target symptoms: seizures/epileptiform activity, irritability, aggression, mood instability.

5.1. Epilepsy and ASD

Epilepsy is a common comorbidity in ASD, with prevalence estimates ranging from 20–30% depending on cohort [

37]. The overlap between epilepsy and behavioral dysregulation has prompted exploration of anticonvulsants as dual-purpose agents, addressing both seizures and behavioral symptoms.

5.2. Valproate

Valproate is one of the most frequently prescribed antiseizure medications in ASD. Preclinical studies of valproic acid (VPA) exposure have even been used to generate rodent models of autism, reflecting its mechanistic relevance [

38]. In clinical contexts, valproate has been shown to reduce aggression and irritability in some patients, but teratogenicity, weight gain, and hepatotoxicity remain major concerns [

39].

5.3. Lamotrigine

Lamotrigine, a sodium channel blocker with glutamate-modulating effects, has produced inconsistent findings in ASD. Belsito et al. [

40] conducted a randomized double-blind trial and found no significant benefit for behavioral symptoms compared to placebo. Nevertheless, some clinicians report improvements in mood instability, suggesting that lamotrigine may be useful in select subgroups.

5.4. Levetiracetam

Levetiracetam is widely used for seizure control and has also been investigated for behavioral outcomes in ASD. Case reports suggest benefits in reducing aggression and self-injurious behavior [

41], but other studies have raised concerns about behavioral activation and irritability [

42]. A broader review highlighted that while levetiracetam is generally well-tolerated, close monitoring is necessary in individuals with ASD due to variable psychiatric side effects [

43].

5.5. Topiramate and Other Antiseizure Drugs

Topiramate has been explored as an adjunctive treatment, particularly in combination with risperidone. Small studies suggest reductions in irritability, though cognitive side effects and sedation are limiting factors [

44]. Frye et al. [

45] reviewed traditional and novel antiseizure medications in ASD and concluded that while seizure control remains paramount, evidence for behavioral benefits is mixed, necessitating larger controlled trials.

6. Neurotrophic, Oxidative Stress, and Immune-Modulating Agents

Target symptoms: irritability, repetitive behaviors, social deficits, immune dysregulation.

6.1. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC)

NAC, a glutathione precursor with antioxidant and glutamatergic-modulating properties, has emerged as one of the most promising adjunctive therapies in ASD. Randomized controlled pilot trials demonstrated that NAC reduced irritability and repetitive behaviors when compared with placebo [

46]. Case reports further support its tolerability and potential utility in treatment-resistant patients [

47]. Larger studies are warranted, but NAC’s favorable safety profile makes it an attractive candidate for adjunctive therapy.

6.2. Minocycline

Minocycline, a tetracycline antibiotic with neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory properties, has also been evaluated in ASD. A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of minocycline as an adjunct to risperidone found significant improvements in irritability [

48]. Its mechanism likely involves microglial inhibition and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine release. However, long-term safety data in pediatric populations remain limited.

6.3. Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) and Oxidative Stress

Altered BDNF levels have been implicated in ASD, linking neurotrophic signaling to abnormal neurodevelopment [

49]. Reviews suggest that targeting BDNF pathways could improve synaptic plasticity and behavioral outcomes. Oxidative stress has also been repeatedly documented in ASD, with elevated markers of lipid peroxidation and reduced antioxidant capacity [

50]. This has driven exploration of antioxidant therapies such as NAC, vitamin E, and omega-3 fatty acids, though evidence remains preliminary.

6.4. Immune and Inflammatory Mechanisms

Immune dysregulation is another proposed contributor to ASD pathophysiology. Celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, demonstrated efficacy in reducing irritability when combined with risperidone in a randomized trial [

51]. Other anti-inflammatory interventions, including minocycline and NAC, may partly exert their benefits through immunomodulatory effects.

Animal models further highlight the role of maternal immune activation in ASD-like phenotypes. Recent studies have demonstrated that nanoparticle-based therapies may prevent the transplacental passage of pathogenic maternal autoantibodies linked to autism risk, offering a novel preventive strategy [

52]. Although still in preclinical stages, such approaches underscore the expanding horizon of immunologically targeted interventions.

7. Glutamatergic Agents and NMDA Modulators

Target symptoms: social withdrawal, repetitive behaviors, irritability, cognitive rigidity.

7.1. Mechanistic Rationale

Abnormal glutamatergic signaling has been proposed as a core neurobiological feature of ASD, with studies demonstrating altered excitatory–inhibitory balance in cortical circuits [

53]. Pharmacological interventions targeting glutamate release or NMDA receptor activity have therefore been investigated as potential therapies.

7.2. Riluzole

Riluzole, an agent that reduces presynaptic glutamate release, has demonstrated tolerability in clinical trials for mood and anxiety disorders. A systematic review and preliminary meta-analysis of riluzole in psychiatric conditions suggested potential benefit for mood stabilization and compulsive behaviors [

54]. Although specific trials in ASD remain limited, riluzole’s mechanism positions it as a candidate for managing repetitive behaviors and emotional dysregulation.

7.3. Ketamine and NMDA Antagonists

Ketamine, a noncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, has gained attention for its rapid-acting antidepressant effects. Its potential in ASD has been explored in pilot studies and preclinical models. Systematic reviews suggest that NMDA antagonists, including ketamine, may attenuate irritability and social deficits, though the evidence base is still preliminary [

55]. Preclinical and psychiatric evidence suggests NMDA blockade modulates glutamatergic signaling [

55,

56].

7.4. Broader NMDA-Targeting Strategies

Recent meta-analyses highlight that NMDA modulators as a class, including agents such as memantine and amantadine, warrant further study in ASD [

55,

57]. While small open-label studies have suggested improvements in hyperactivity and social responsiveness, placebo-controlled trials have yielded mixed results. At present, NMDA-targeting pharmacotherapies remain investigational in ASD, requiring larger and longer-term studies to establish efficacy and safety.

8. Adrenergic Agents (Clonidine and Guanfacine)

Target symptoms: hyperactivity, impulsivity, hyperarousal, anxiety, sleep problems.

8.1. Mechanistic Rationale

Adrenergic agents, particularly α2-adrenergic receptor agonists, are frequently used to manage hyperactivity and impulsivity in ASD, especially when stimulants are poorly tolerated. Their mechanism involves reducing presynaptic norepinephrine release, thereby calming overactive sympathetic responses [

58].

8.2. Clonidine

Clonidine was one of the earliest α2-agonists studied in autism. In small open-label trials and case reports, clonidine improved hyperactivity, sleep disturbance, and irritability [

59]. However, sedation and hypotension were common, requiring careful dose titration. A systematic review confirmed clonidine’s modest efficacy, concluding that it may be most useful for children with prominent hyperarousal and sleep disturbance [

60].

8.3. Guanfacine

Compared to clonidine, guanfacine has a longer half-life and is less sedating. Controlled trials have demonstrated that guanfacine extended-release significantly reduces hyperactivity and oppositional symptoms in ASD [

61]. Clinical experience also supports guanfacine as a monotherapy or adjunct to stimulants for comorbid ADHD symptoms.

8.4. Clinical Considerations

Although α2-agonists are not FDA-approved for ASD, they are often used off-label in clinical practice. Their utility lies in cases where stimulants exacerbate anxiety, irritability, or sleep difficulties. Monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate is recommended, particularly at higher doses [

62].

9. Discussion and Future Directions

Pharmacological interventions in ASD address an array of behavioral and neurobiological targets, yet no single therapy effectively treats the full spectrum of symptoms. The strongest evidence continues to support atypical antipsychotics (risperidone, aripiprazole) for irritability [

18,

19,

20,

21], while SSRIs show mixed but sometimes meaningful benefits for comorbid anxiety and repetitive behaviors [

10,

11]. Stimulants and α2-agonists offer options for ADHD-like symptoms, but tolerability concerns necessitate careful monitoring [

28,

32,

58]. Anticonvulsants remain essential for seizure management, though behavioral benefits are inconsistent [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. Emerging approaches, including NAC, minocycline, riluzole, and NMDA modulators, highlight novel mechanistic targets but require further study [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

9.1. Mechanistic Insights

Neuroimaging and neuropathological work suggests ASD involves widespread disruptions in cortical connectivity and synaptic signaling [

63,

64]. Studies of oxytocin receptors and peptide levels indicate that disruptions in the oxytocinergic system may contribute to social impairments, raising the possibility of oxytocin-based therapeutics [

65,

66]. Other mechanistic research points to microglial activation, oxidative stress, and excitatory–inhibitory imbalance, all of which inform emerging pharmacological strategies [

50,

53].

9.2. Safety and Long-Term Outcomes

Concerns about chronic antipsychotic exposure remain prominent. Nonhuman primate studies show that long-term antipsychotic treatment may alter brain volume and connectivity [

67], highlighting the importance of balancing short-term behavioral gains against potential neurodevelopmental risks. Similarly, surveys of medication use emphasize that many children remain on psychotropic medications for extended periods without systematic re-evaluation [

68,

69].

9.3. Guidelines and Consensus

International guidelines underscore the principle that medications should target specific impairing symptoms, be initiated cautiously, and always be combined with behavioral interventions [

6,

27,

70]. Recent systematic reviews also emphasize the importance of individualized medicine, including biomarker-guided treatment approaches, to optimize efficacy while minimizing adverse outcomes [

71,

72].

9.4. Emerging and Preventive Approaches

Novel immune-modulating strategies, such as nanoparticle-based therapies to block maternal autoantibody transfer, illustrate the potential for preventive interventions [

52]. Advances in genetics and metabolomics may allow clinicians to identify subgroups of individuals with ASD who are most likely to benefit from particular pharmacotherapies [

73]. Trials of agents targeting neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and glutamatergic signaling reflect a shift toward mechanism-based treatment development [

74,

75].

9.5. Future Research Priorities

Looking forward, clinical research should prioritize:

Large, well-controlled trials of promising novel agents (e.g., NAC, riluzole, ketamine).

Longitudinal safety studies, particularly for antipsychotics and stimulants used in children.

Biomarker integration to predict treatment response (e.g., metabolomic profiling [

14], oxytocin receptor expression [

65]).

Preventive strategies that target maternal immune activation and early neurodevelopmental pathways [

52].

Combination therapies that integrate behavioral interventions, psychopharmacology, and family support, reflecting the multifaceted nature of ASD.

Ultimately, while substantial progress has been made, achieving personalized, mechanism-driven pharmacotherapy remains the central challenge and opportunity in ASD treatment.

10. Conclusions

Pharmacological treatments for ASD have advanced considerably, yet the therapeutic landscape remains fragmented and symptom-targeted rather than curative. Atypical antipsychotics provide robust evidence for managing irritability, while SSRIs, stimulants, anticonvulsants, and adrenergic agents offer variable benefits for comorbid symptoms. Emerging pharmacotherapies that target oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and glutamatergic dysregulation hold promise but remain experimental.

The heterogeneity of ASD underscores the need for precision medicine approaches, incorporating biomarkers, genetic profiling, and individualized treatment algorithms. Future research must focus on long-term safety, comparative effectiveness, and preventive strategies, while integrating pharmacologic and behavioral interventions. Ultimately, pharmacotherapy in ASD should be viewed not as a stand-alone solution but as part of a comprehensive, multimodal treatment strategy tailored to the unique profile of each individual.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.S., S.P., C.Q and Y.G.; investigation, E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.S.; writing—review and editing, S.P., C.Q. and Y.G.; supervision, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH/NIA Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center grant P30AG072931 and the University of Michigan Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Berger Endowment) to Y.G.; the Honors College Research Fund (Michigan State University) to S.P.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Baio J, et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobski K, Höfer J, Hoffmann F, Bachmann C. Use of psychotropic drugs in patients with ASD: A systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2017, 135, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman DM, Adams JB, Anderson AL, Frye RE. Rating of the effectiveness of 26 psychiatric and seizure medications for autism spectrum disorder: Results of a national survey. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 29, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb S, Akrout Brizard B, Limbu B. Association between epilepsy and challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open 2020, 6, e114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasa RA, Carroll LM, Nozzolillo AA, Mahajan R, Mazurek MO, Bennett AE, et al. Systematic review of treatments for anxiety in youth with ASD. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2014, 44, 3215–3229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb S, Kwok H, Bertelli M, Salvador-Carulla L, Bradley E, Torr J, et al. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, St Peter C. Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism 2014, 18, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugani, D. Role of altered brain serotonin mechanisms in autism. Mol Psychiatry 2002, 7 (Suppl. S2), S16–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller CL, Anacker AM, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. The serotonin system in autism spectrum disorder: From biomarker to animal models. Neuroscience 2016, 321, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams K, Brignell A, Randall M, Silove N, Hazell P. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 8, CD004677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddihough DS, Marraffa C, Mouti A, O’Sullivan M, Lee KJ, Orsini F, et al. Effect of fluoxetine on obsessive-compulsive behaviours in children and adolescents with ASD: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019, 322, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.J. , Drahota, A., Sze, K., Har, K., Chiu, A. and Langer, D.A.Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders: a randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2009, 50, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golub MS, Hogrefe CE, Bulleri AM. Peer social interaction is facilitated in juvenile rhesus monkeys treated with fluoxetine. Neuropharmacology 2016, 105, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He Y, Hogrefe C, Grapov D, et al. Identifying individual differences of fluoxetine response in juvenile rhesus monkeys by metabolite profiling. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King BH, Hollander E, Sikich L, McCracken JT, Scahill L, Bregman JD, et al. Lack of efficacy of citalopram in children with autism spectrum disorders and high levels of repetitive behavior: Citalopram ineffective in children with autism. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2009, 66, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter LA, Scholze DA, Biag HMB, Schneider A, Chen Y, Nguyen DV, Rajaratnam A, Rivera SM, Dwyer PS, Tassone F, Al Olaby RR, Choudhary NS, Salcedo-Arellano MJ, Hagerman RJ. A randomized controlled trial of sertraline in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry 2019, 10, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson LT, Campbell M, Grega DM, Perry R, Small AM, Green WH. Haloperidol in the treatment of infantile autism: Effects on learning and behavioral symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatry 1984, 141, 1195–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougle CJ, Scahill L, McCracken JT, Aman MG, Tierney E, Arnold LE, et al. Risperidone for the core symptom domains of autism: Results from the RUPP Autism Network. Am. J. Psychiatry 2005, 162, 1142–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus RN, Owen R, Kamen L, Manos G, McQuade RD, Carson WH, et al. A placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study of aripiprazole in children and adolescents with irritability associated with autistic disorder. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2009, 48, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alò GL, De Crescenzo F, Amato L, Cruciani F, Davoli M, Fulceri F, et al. Impact of antipsychotics in children and adolescents with ASD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2021, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung LK, Mahajan R, Nozzolillo A, Bernal P, Krasner A, Jo B, et al. Pharmacologic treatment of severe irritability and problem behaviors in autism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2016, 137 (Suppl. S2), S124–S135. [CrossRef]

- Stavrakaki C, Antochi R, Emery PC. Olanzapine in the treatment of pervasive developmental disorders: A case series analysis. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004, 29, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubchik P, Sever J, Weizman A. Low-dose quetiapine for adolescents with ASD and aggressive behavior: Open-label trial. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2011, 34, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominick K, Wink LK, McDougle CJ, Erickson CA. A retrospective naturalistic study of ziprasidone for irritability in youth with ASD. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 25, 397–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigler KA, Mullett JE, Erickson CA, Posey DJ, McDougle CJ. Paliperidone for irritability in adolescents and young adults with autistic disorder. Psychopharmacology 2012, 223, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Rosa ALST, Bezerra OS, Rohde LA, Graeff-Martins AS. Exploring clozapine use in severe psychiatric symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. J. Psychopharmacol. 2024, 38, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb S, Kwok H, Bertelli M, Salvador-Carulla L, Bradley E, Torr J, et al. International guide to prescribing psychotropic medication for the management of problem behaviours in adults with intellectual disabilities. World Psychiatry 2009, 8, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handen BL, Johnson CR, Lubetsky M, Sacco K. Efficacy of methylphenidate among children with autism and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2000, 30, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturman N, Deckx L, van Driel ML. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 11, CD011144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Sol Calderon, P. , Izquierdo de la Puente, A., García Moreno, M., & Fernández Fernandez, R. Lisdexamfetamine in combination with guanfacine as an effective treatment in the management of behavioral disturbances in patients with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Case report. European Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- Faraone, SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: Relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018, 87, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill L, Aman MG, McDougle CJ, Arnold LE, McCracken JT, Tierney E, et al. A prospective open trial of guanfacine in children with pervasive developmental disorders. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 16, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaselskis, C. A. , Cook, E. H., Jr, Fletcher, K. E., & Leventhal, B. L. Clonidine treatment of hyperactive and impulsive children with autistic disorder. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology 1992, 12, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banas K, Sawchuk B. Clonidine as a treatment of behavioural disturbances in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Bagcioglu, E. , Solmaz, V., Erbas, O., Özkul, B., Çakar, B., Uyanikgil, Y., & Söğüt, İ. Modafinil Improves Autism-like Behavior in Rats by Reducing Neuroinflammation. Journal of neuroimmune pharmacology : the official journal of the Society on NeuroImmune Pharmacology 2023, 18, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, P. , & Malcolm, R. Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2007, 3, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuchman, R. , & Rapin, I. Epilepsy in autism. The Lancet. Neurology 2002, 1, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomiak T, Turner N, Hu B. What we have learned about autism spectrum disorder from valproic acid. Pathol. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 712758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander E, Soorya L, Wasserman S, Esposito K, Chaplin W, Anagnostou E. Divalproex sodium vs placebo in the treatment of repetitive behaviours in autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 9, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsito KM, Law PA, Kirk KS, Landa RJ, Zimmerman AW. Lamotrigine therapy for autistic disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2001, 31, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deriaz N, Willi JP, Orihuela-Flores M, Galli Carminati G, Ratib O. Treatment with levetiracetam in a patient with pervasive developmental disorders, severe intellectual disability, self-injurious behavior, and seizures: A case report. Neurocase 2012, 18, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq MU, Bhatt A, Majid A, Gupta R, Khasnis A, Kassab MY. Levetiracetam for managing neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2009, 66, 541–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halma, E. , de Louw, A. J., Klinkenberg, S., Aldenkamp, A. P., IJff, D. M., & Majoie, M. Behavioral side-effects of levetiracetam in children with epilepsy: a systematic review. Seizure 2014, 23, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei V, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, Sahraian A, Tabrizi M, Karami R, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of risperidone plus topiramate in children with autistic disorder. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 34, 1269–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye RE, Rossignol D, Casanova MF, Brown GL, Martin V, Edelson S, et al. A review of traditional and novel treatments for seizures in autism spectrum disorder: Findings from a systematic review and expert panel. Front. Public Health 2013, 1, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardan AY, Fung LK, Libove RA, Obukhanych TV, Nair S, Herzenberg LA, et al. A randomized controlled pilot trial of oral N-acetylcysteine in children with autism. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 71, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh A, Derakhshan N. N-acetylcysteine for treatment of autism, a case report. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2012, 17, 985–987. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleh A, Alikhani R, Kazemi MR, Mohammadi MR, Mohammadinejad P, Zeinoddini A, et al. Minocycline as adjunctive treatment to risperidone in children with autistic disorder: A randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 827–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng Z, Zhang L, Zhu T, Huang J, Qu Y, Mu D. Peripheral brain-derived neurotrophic factor in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 31241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan A, Chauhan V. Oxidative stress in autism. Pathophysiology 2006, 13, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadabadi M, Mohammadi MR, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Celecoxib as adjunctive treatment to risperidone in children with autistic disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 2013, 225, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolandparvaz A, Harriman R, Alvarez K, Lilova K, Zang Z, Lam A, Edmiston E, Navrotsky A, Vapniarsky N, Van De Water J, Lewis JS. Towards a nanoparticle-based prophylactic for maternal autoantibody-related autism. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2019, 21, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova G, Pallanti S, Hollander E. Excitatory/inhibitory imbalance in autism spectrum disorders: Implications for interventions and therapeutics. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 17, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Boer JN, Vingerhoets C, Hirdes M, McAlonan GM, van Amelsvoort T, Zinkstok JR. Efficacy and tolerability of riluzole in psychiatric disorders: A systematic review and preliminary meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 278, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dessus-Gilbert ML, Nourredine M, Zimmer L, Rolland B, Geoffray MM, Auffret M, et al. NMDA antagonist agents for the treatment of symptoms in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1395867. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X. Y. , Feng, J. C., Cao, C., Wu, H. T., Loh, Y. P., & Cheng, Y. Association of Peripheral Blood Levels of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics 2016, 170, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson CA, Posey DJ, Stigler KA, McDougle CJ. A retrospective study of memantine in children and adolescents with pervasive developmental disorders. Psychopharmacology 2007, 191, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scahill L, McCracken JT, King BH, Rockhill C, Shah B, Politte L, et al. Extended-release guanfacine for hyperactivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, X. , Gordon, E., Kang, N., & Wagner, G. C. Use of clonidine in children with autism spectrum disorders. Brain & development 2008, 30, 454–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banas K, Sawchuk B. Clonidine as a treatment of behavioural disturbances in autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. J. Can. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2020, 29, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Charman, T. Mapping Early Symptom Trajectories in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Lessons and Challenges for Clinical Practice and Science. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2018, 57, 820–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posey DJ, Puntney JI, Sasher TM, Kem DL, Swiezy NB, McDougle CJ. Guanfacine treatment of hyperactivity and inattention in pervasive developmental disorders: A retrospective analysis of 80 cases. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 14, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecker C, Bookheimer SY, Murphy DG. Neuroimaging in autism spectrum disorder: Brain structure and function across the lifespan. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courchesne E, Campbell K, Solso S. Brain growth across the life span in autism: Age-specific changes in anatomical pathology. Brain Res. 2011, 1380, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loth E, Poline JB, Thyreau B, Jia T, Tao C, Lourdusamy A, et al. Oxytocin receptor genotype modulates ventral striatal activity to social cues in ASD. Transl. Psychiatry 2014, 4, e480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang HF, Dai YY, Zhong JY, Hu CJ, Bai ZZ, An Y, et al. Plasma oxytocin and arginine-vasopressin levels in children with autism spectrum disorder in China: Associations with symptom severity. Neurosci. Bull. 2016, 32, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorph-Petersen KA, Pierri JN, Sun Z, Sampson AR, Lewis DA. Effects of chronic exposure to antipsychotics on brain size and cell numbers in macaque monkeys. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005, 30, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandell DS, Morales KH, Marcus SC, Stahmer AC, Doshi J, Polsky DE. Psychotropic medication use among Medicaid-enrolled children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2008, 121, e441–e448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray ML, Hsia Y, Glaser K, Simonoff E, Murphy DG, Asherson PJ, et al. Pharmacological treatments prescribed to people with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in primary health care. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 1011–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Autism spectrum disorder in under 19s: Support and management. NICE guideline [CG170] 2013. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Lai, M. C. , Lombardo, M. V., & Baron-Cohen, S. Autism. Lancet 2014, 383, 896–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, S. , Frye, R. E., Slattery, J., Wynne, R., Tippett, M., Pavliv, O., Melnyk, S., & James, S. J. Oxidative stress induces mitochondrial dysfunction in a subset of autism lymphoblastoid cell lines in a well-matched case control cohort. PloS one 2014, 9, e85436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma SR, Gonda X, Tarazi FI. Autism spectrum disorder: Classification, diagnosis and therapy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 190, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matta SM, Hill-Yardin EL, Crack PJ. The influence of neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2019, 79, 75–90. [CrossRef]

- Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism: A review and integration of findings. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandin S, Lichtenstein P, Kuja-Halkola R, Larsson H, Hultman CM, Reichenberg A. The familial risk of autism. JAMA 2014, 311, 1770–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).