1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition that affects how individuals perceive and interact with the world. Rather than a single, uniform disorder, autism is now understood as a spectrum of diverse neurodevelopmental profiles, characterized by early-onset difficulties in social communication and unusually restricted repetitive behavior and narrow interests [

1,

2]. The conceptual shift from multiple single disorders to unique spectrum reflects the growing recognition that autistic traits can manifest with varying degrees of intensity and in distinct combinations across individuals and across the lifespan.

ASD is estimated to affect around 1–2% of the population worldwide, with a prevalence of 100/10,000 [

3] making it a prominent focus of clinical, educational, and policy-related efforts. The growing awareness of autism in recent decades has contributed to earlier diagnoses and better support [

4], but also highlighted the limitations of traditional categorical models and the need for more inclusive, individualized approaches [

5]. According to the surveillance program ‘The Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring’ (ADDM) founded by the U.S Centers of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), prevalence moved from 0.6% in 2000 to 1.4% in 2010 to 2.7% in 2020 [

6]. ADMM estimated that 1 in 36 children in USA have an ASD and it is 3.8 times as prevalent among boys as among girls. Similar data are reported in Italy with 1 in 77 children aged between 7 and 9 years diagnosed with ASD and boys being four times more affected than girls [

7].

Early diagnosis tends to be made more readily in individuals with severe symptoms (eg, extreme social aloneness, no eye contact, and frequent motor stereotypes) and concurrent developmental difficulties (eg, cognitive or language delay). Autism spectrum conditions in people without obvious developmental delay (eg, those with Asperger’s syndrome) and with more subtle difficulties tend to be recognized later [

8]. Similarly, a multiagency assessment service reported that only 46% of patients deemed likely cases of ASD received a positive diagnosis [

9]. These findings suggest that concerns about ASD are not always confirmed, potentially leading to extended waiting times for those who truly have ASD.

Receiving a first diagnosis of autism in adulthood has increasingly been recognized as a relevant clinical issue. This growing recognition is largely due to increased public and professional awareness, the broadening of diagnostic criteria, and the adoption of the spectrum concept, which has expanded the understanding of autism beyond childhood presentations.

First identification of ASD in adulthood was clearly established in DSM-5. In particular, according to DSM-5 definition: 1) diagnostic behavioral descriptions apply to all ages; 2) behavior contributing to a diagnosis can be current or historical; 3) and criterion of a specific early age of onset is no longer required, being replaced by “symptoms must be present in the early developmental period (but may not become fully manifest until social demands exceed limited capacities, or may be masked by learned strategies in later life)” [

10].

The accurate and timely identification of ASD in adulthood, along with the provision of appropriate support services, has become a critical clinical priority [

11,

12]. The development of supportive, inclusive, and autism-friendly social and physical environments necessitates should be underpinned by supportive government policies.

Making a first diagnosis of ASD in adults can be challenging for practical reasons (eg, frequently no person to provide a developmental history), developmental reasons (eg, the acquisition of learnt or camouflaging strategies), and clinical reasons (eg, high frequency of co-occurring disorders) [

13,

14,

15,

16].

The diagnostic process includes referral, screening, interviews with informants and patients, and functional assessments. In delineating differential diagnoses, true comorbidities, and overlapping behaviour with other psychiatric diagnoses, particular attention should be paid to anxiety, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosis, personality disorders, and other neurodevelopmental disorders. Possible misdiagnosis, especially in women, should be explored [

17].

A study of 859 adults referred for ASD assessment found high rates of psychiatric diagnoses ( > 57%) in both ASD and non-ASD groups, with anxiety disorders being significantly more prevalent in those with ASD [

18]. Another study reported that 24.6% of 1211 autistic adults perceived at least one previous psychiatric diagnosis as a misdiagnosis, with personality disorders being the most frequent [

19]. In a sample of 161 adults diagnosed with ASD, there was a median 11-year gap between first mental health evaluation and ASD diagnosis, with 33.5% never receiving a prior psychiatric diagnosis [

20]. These findings suggest that adult psychiatric care may not adequately recognize ASD, particularly in patients with substance abuse and psychiatric symptoms [

21], highlighting the need for improved clinician training in adult ASD presentation.

This study aims to present original data derived from the clinical activities of an adult ASD outpatient service based in Rome and to examine the prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities among individuals diagnosed with ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study in sixty-four subjects enrolled in the psychiatry outpatient units of two University Hospital in Rome between September 2023 and January 2025, the Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital and the Tor Vergata University Hospital.

All subjects enrolled in the study met the DSM-5 criteria for ASD diagnosis [

10]. All participants were assessed using the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition – Module 4 (ADOS-2) [

22], a standardized semi-structured assessment tool designed to evaluate social interaction and communication, play, and restricted or repetitive behaviors. The ADOS-2 was administered by expert clinicians familiar with its use.

Psychiatric comorbidities were diagnosed through clinical evaluation and the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) Plus [

23], which assesses 26 psychiatric disorders following the classification of the DSM-5 [

24].

The only adopted exclusion criteria was the presence of mild to severe cognitive impairment, as established by the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) [

25].

Sociodemographic data (including age, sex, and marital status) and clinical information were systematically collected.

To evaluate depressive symptomatology, participants completed the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) [

26]. BDI-II, in its original 21-item version, is a self-report scale that measures the intensity of depressive symptoms. Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale, providing a total score that reflects the severity of depressive symptomatology, with established cut-off points for minimal, mild, moderate, and severe depression.

3. Results

The ASD group included 29 females (45.3%) and had a mean age of 30.9 years (SD = 8.92; range: 18–57 years).

All patients had received a diagnosis of Level 1 ASD and none of the patients met criteria for intellectual disability.

The average educational attainment was 13.8 years (SD = 2.24). Five individuals (7.8%) reported current cannabis use, and 45 (77.6%) resided in urban areas. At the time of the evaluation, 27 participants (42.2%) were receiving pharmacological treatment, including antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or benzodiazepines. All therapies were prescribed by general practitioners or specialist before first evaluation. Detailed descriptive statistics for the sociodemographic characteristics are provided in

Table 1.

Sixty-one subjects completed the BDI-II. According to the BDI-II, 42.6% of participants reported no depressive symptoms. Overall, more than half of the participants (57.4%) reported at least mild levels of depression, with 42.6% showing clinically relevant moderate to severe depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms distribution is summarized in

Table 2a,b.

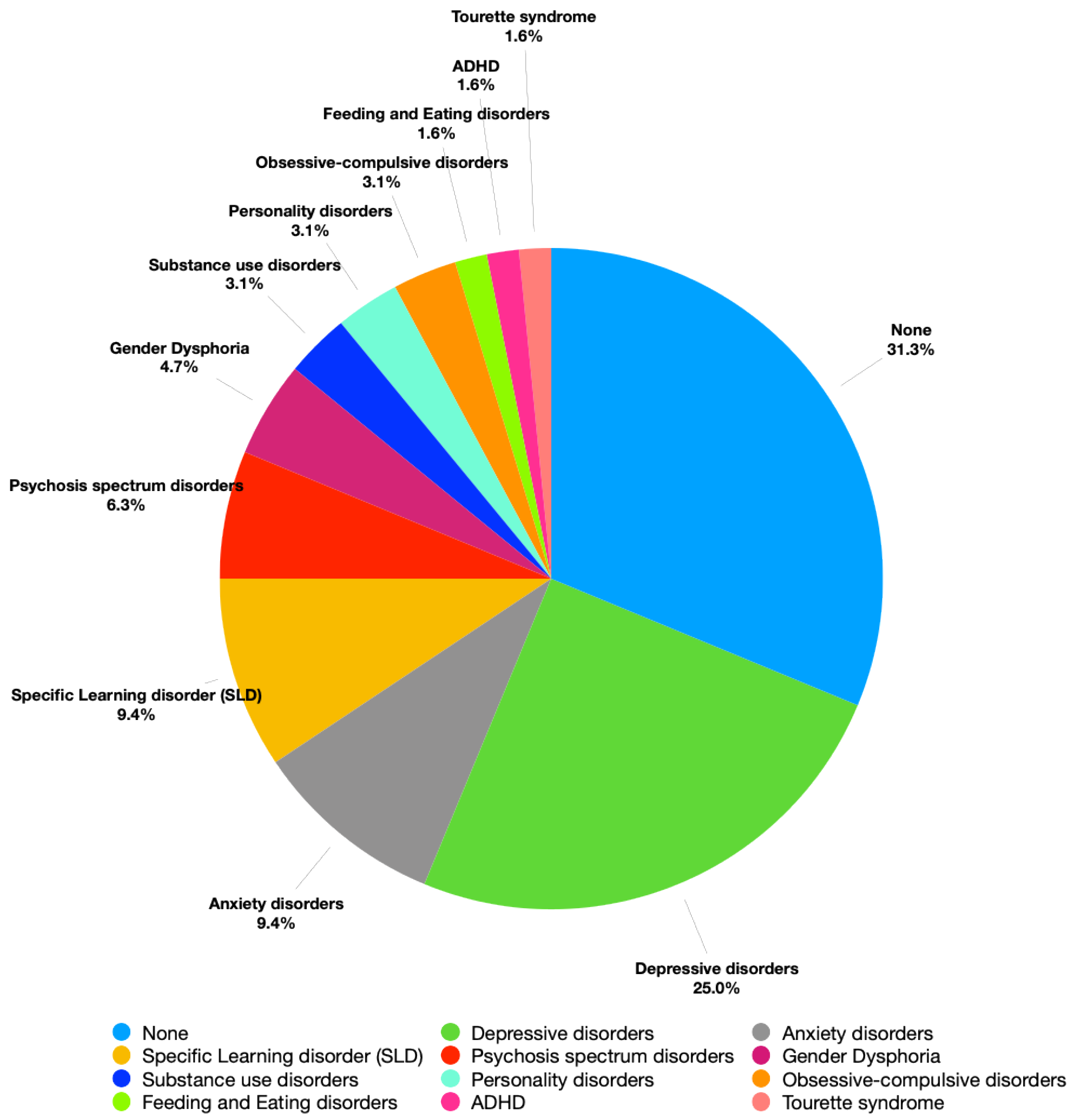

Forty-four patients (68.7%) presented with at least one comorbid psychiatric disorder, with depression (n = 16, 25.0%) and anxiety disorders (n = 6, 9.4%) emerging as the most frequently reported conditions. Absolute numbers and prevalence rates of psychiatric comorbidities are detailed in

Table 3 and resumed in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

The present study aims to investigate the presence of comorbid psychiatric conditions in a sample of adult individuals with ASD referred to an outpatient service.

A high rate of psychiatric comorbidity was observed in the sample, with 68.8% of participants presenting at least one additional diagnosis alongside ASD. This result is similar to previous studies (Lai et al, 2019). An epidemiological study conducted in a large US metropolitan region showed that majority of ASD adolescents (58.8%) had a co-occurring neuropsychiatric disorder (Zahorodny et al, 2025).

The most prevalent comorbid conditions were depressive (25.0%) and anxiety disorders (9.4%), which together accounted for over one-third of all cases. These findings are consistent with existing literature showing high prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders among ASD [

27,

28,

29] and may be partly explained by the unique challenges faced by high-functioning autistic individuals, particularly in adulthood [

27,

30]. Despite intact cognitive functioning, individuals with ASD often experience difficulties in social integration, emotional regulation, and managing complex interpersonal and occupational demands. These challenges can lead to increased stress, feelings of isolation, and repeated experiences of failure or rejection, all of which may contribute significantly to the development of affective disorders, including anxiety and depression [

31].

The onset of depressive disorders in individuals with ASD may be associated with increased awareness of their core social difficulties. As individuals become more conscious of their challenges in social interactions, they may experience a decline in self-esteem. Repeated unsuccessful attempts to integrate into social contexts can lead to peer rejection, which in turn may precipitate depressive symptoms. In more severe cases, this trajectory may contribute to suicidal ideation or attempts [

32,

33]

A limitation of the present study concerns the low number of participants with comorbid ADHD. Previous research has identified ADHD as one of the most common comorbidities. In our sample, only one individual was diagnosed with comorbid ADHD. This finding is likely due to a sampling bias. Patients referred to our adult autism outpatient clinic are initially evaluated in a general psychiatry setting. Individuals with suspected ADHD are typically referred directly to a specialized center for the diagnosis and treatment of that condition. In contrast, those with suspected autism are referred to the Adult Autism Clinic for further diagnostic assessment. As a result, the autistic patients included in our study had already been screened for suspected ADHD and were excluded if attentional deficits or hyperactivity were present.

5. Conclusions

Our final consideration concerns the complexity of diagnosing ASD in adults. Prior to the expansion of diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, many individuals were excluded from diagnosis, leading to the concept of a "lost generation" of adults with ASD [

34]. Although these individuals can now seek re-evaluation, diagnosing ASD in adulthood, particularly in milder forms, remains challenging. Camouflaging and adaptive strategies further complicate the diagnostic process. Moreover, ASD rarely occurs in isolation. Comorbidities often present unique challenges in clinical practice, requiring a multidisciplinary and nuanced approach to assessment and care. Adult psychiatric services may struggle to recognize ASD, particularly in patients with comorbid psychosis and negative symptoms [

14,

35] highlighting the need for improved clinician training. Early detection of attenuated psychotic symptoms in ASD [

36,

37,

38] during the transition from adolescence to adulthood may radically alter the course of comorbidities and improve prognosis. Understanding and identifying comorbidities in ASD is critical not only for achieving accurate diagnoses but also for tailoring effective, individualized interventions. Future research involving larger samples and rigorous methodologies is needed to deepen understanding of the ASD phenotype in adults, with crucial implications for prognosis and therapeutic strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.D.L. and M.R.; Methodology, M.P., F.F.N., C.M., S.M.; Data Curation, M.P., F.F.N., C.M., S.M.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.P., F.F.N.; Writing – Review & Editing, V.D.L., G.D.L. and M.R.; Supervision, M.R.; Project Administration, V.D.L. and G.D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Independent Ethics committee of Policlinico Tor Vergata (26/June/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by #NEXTGENERATIONEU (NGEU) and funded by the Ministry of University and Research (MUR), National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), project MNESYS (PE0000006) – (DN. 1553 11.10.2022).

Conflicts of Interest

None of the Authors have any conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5-TR; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: 2022.

- Lord, C.; Elsabbagh, M.; Baird, G.; Veenstra-Vanderweele, J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet 2018, 392, 508–520. [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, J.; Fombonne, E.; Scorah, J.; Ibrahim, A.; Durkin, M.S.; Saxena, S.; Yusuf, A.; Shih, A.; Elsabbagh, M. Global prevalence of autism: A systematic review update. Autism Res 2022, 15, 778–790. [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, L.P.; Croen, L.A.; Lynch, F.L.; Marafino, B.J.; Maye, M.; Penfold, R.B.; Simon, G.E.; Ames, J.L. Autism Diagnosis Among US Children and Adults, 2011-2022. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2442218–e2442218. [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Wang, H.; Ning, W.; Cui, M.; Wang, Q. New advances in the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders. European Journal of Medical Research 2024, 29, 322. [CrossRef]

- Maenner, M.J.; Shaw, K.A.; Baio, J.; Washington, A.; Patrick, M.; DiRienzo, M.; Christensen, D.L.; Wiggins, L.D.; Pettygrove, S.; Andrews, J.G.; et al. Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2016. MMWR Surveill Summ 2020, 69, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- ISS. N°26/2022 - Autismo, il 2 aprile la Giornata mondiale della consapevolezza. 2022.

- Mandell, D.S.; Novak, M.M.; Zubritsky, C.D. Factors associated with age of diagnosis among children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 1480–1486. [CrossRef]

- McClure, I.; Mamdani, H.; McCaughey, R. Diagnosis of autism: adequate funding is needed for assessment services. Bmj 2004, 328, 226. [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®); American Psychiatric Publishing: 2013.

- Lai, J.K.Y.; Weiss, J.A. Priority service needs and receipt across the lifespan for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res 2017, 10, 1436–1447. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Arnold, S.R.; Foley, K.R.; Trollor, J.N. Diagnosis of autism in adulthood: A scoping review. Autism 2020, 24, 1311–1327. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, H.M.; Thom, R.P.; McDougle, C.J. The differential diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder in adults. Expert Rev Neurother 2025, 25, 635–648. [CrossRef]

- Ribolsi, M.; Fiori Nastro, F.; Pelle, M.; Medici, C.; Sacchetto, S.; Lisi, G.; Riccioni, A.; Siracusano, M.; Mazzone, L.; Di Lorenzo, G. Recognizing Psychosis in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 768586. [CrossRef]

- Fiori Nastro, F.; Esposto, E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Ribolsi, M. Challenges in diagnosis: exploring comorbidities and differential diagnosis in a young adult with mild Autism Spectrum Disorder and attenuated psychosis syndrome. Journal of Psychopathology 2023.

- Esposto, E.; Fiori Nastro, F.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Ribolsi, M. Navigating the intersection between autism spectrum disorderr and bipolar disorder: a case study. Journal of Psychopathology 2023.

- Brugha, T.S.; Spiers, N.; Bankart, J.; Cooper, S.A.; McManus, S.; Scott, F.J.; Smith, J.; Tyrer, F. Epidemiology of autism in adults across age groups and ability levels. Br J Psychiatry 2016, 209, 498–503. [CrossRef]

- Russell, A.J.; Murphy, C.M.; Wilson, E.; Gillan, N.; Brown, C.; Robertson, D.M.; Craig, M.C.; Deeley, Q.; Zinkstok, J.; Johnston, K.; et al. The mental health of individuals referred for assessment of autism spectrum disorder in adulthood: A clinic report. Autism 2016, 20, 623–627. [CrossRef]

- Kentrou, V.; Livingston, L.A.; Grove, R.; Hoekstra, R.A.; Begeer, S. Perceived misdiagnosis of psychiatric conditions in autistic adults. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 71, 102586. [CrossRef]

- Fusar-Poli, L.; Brondino, N.; Politi, P.; Aguglia, E. Missed diagnoses and misdiagnoses of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2022, 272, 187–198. [CrossRef]

- Scharin, M.; Hellström, P. [Adult psychiatry does not recognize child neuropsychiatric disorders. A registry study shows discrepancy between expected and real number of cases]. Lakartidningen 2004, 101, 3230–3231.

- Lord, C.; Rutter, M.; DiLavore, P.; Risi, S.; Gotham, K.; Bishop, S. Autism diagnostic observation schedule–2nd edition (ADOS-2). Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Corporation 2012, 284.

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 1998, 59 Suppl 20, 22–33;quiz 34–57.

-

Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed; American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.: Arlington, VA, US, 2013; pp. xliv, 947–xliv, 947.

- Franzen, M.D. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised and Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-III. In Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Goldstein, G., Hersen, M., Eds.; Elsevier: New York, 2000; pp. 55–70.

- Beck, A.T.; Ward, C.H.; Mendelson, M.; Mock, J.; Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961, 4, 561–571. [CrossRef]

- Hollocks, M.J.; Lerh, J.W.; Magiati, I.; Meiser-Stedman, R.; Brugha, T.S. Anxiety and depression in adults with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2019, 49, 559–572. [CrossRef]

- Lugo Marin, J.; Alviani Rodriguez-Franco, M.; Mahtani Chugani, V.; Magan Maganto, M.; Diez Villoria, E.; Canal Bedia, R. Prevalence of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders in Average-IQ Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2018, 48, 239–250. [CrossRef]

- Uljarević, M.; Hedley, D.; Rose-Foley, K.; Magiati, I.; Cai, R.Y.; Dissanayake, C.; Richdale, A.; Trollor, J. Anxiety and Depression from Adolescence to Old Age in Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2020, 50, 3155–3165. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Kassee, C.; Besney, R.; Bonato, S.; Hull, L.; Mandy, W.; Szatmari, P.; Ameis, S.H. Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry 2019, 6, 819–829. [CrossRef]

- Smith, O.; Jones, S.C. ‘Coming Out’ with Autism: Identity in People with an Asperger’s Diagnosis After DSM-5. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 2020, 50, 592–602. [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.; Azzoni, A.; Frustaci, A. AUTISM Spectrum Disorders and Suicidality. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2011, 7, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Mikami, K.; Akama, F.; Yamada, K.; Maehara, M.; Kimoto, K.; Kimoto, K.; Sato, R.; Takahashi, Y.; Fukushima, R.; et al. Clinical features of suicide attempts in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013, 35, 50–53. [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Baron-Cohen, S. Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 1013–1027. [CrossRef]

- Ribolsi, M.; Albergo, G.; Fiori Nastro, F.; Pelle, M.; Contri, V.; Niolu, C.; Di Lazzaro, V.; Siracusano, A.; Di Lorenzo, G. Autistic symptomatology in UHR patients: A preliminary report. Psychiatry Res 2022, 313, 114634. [CrossRef]

- Ribolsi, M.; Esposto, E.; Fiori Nastro, F.; Falvo, C.; Fieramosca, S.; Albergo, G.; Niolu, C.; Siracusano, A.; Di Lorenzo, G. The onset of delusion in autism spectrum disorder: a psychopathological investigation. Journal of psychopathology 2023.

- Riccioni, A.; Siracusano, M.; Vasta, M.; Ribolsi, M.; Fiori Nastro, F.; Gialloreti, L.E.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Mazzone, L. Clinical profile and conversion rate to full psychosis in a prospective cohort study of youth affected by autism spectrum disorder and attenuated psychosis syndrome: A preliminary report. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 950888.

- Fiori Nastro, F.; Pelle, M.; Clemente, A.; Corinto, F.; Prosperi Porta, D.; Sonnino, Y.; Gelormini, C.; Di Lorenzo, G.; Ribolsi, M. Investigating Aberrant Salience in autism spectrum disorder and psychosis risk: a cross-group analysis. Early intervention in psychiatry 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).